C.Owers The Fighting America Flying Boats of WWI Vol.1 (A Centennial Perspective on Great War Airplanes 22)

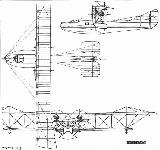

The British Curtiss H-8 and H-12

<...>

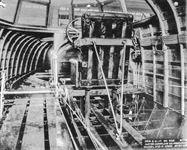

The Curtiss engines were not accepted and new mountings had to be made for the Rolls Royce Eagle engines. The petrol pipes on 8650 were without expansion joints and were connected by screwed unions which depended on shellack to make them tight. The petrol pumps had to be replaced by ones made on the Station, and the gravity tanks built and fitted into the centre section of the top plane. The results of these trials and modifications must have gone back to Curtiss in the USA as the next machine to arrive at Felixstowe in October 1916, 8651, had a larger hull. Considering the time between when the first and second machines were accepted at Felixstowe, it is assumed that the relevant drawings would have been prepared and shipped to Curtiss. To date no correspondence has been found that can provide light on the exchange of information between the British and the Curtiss Company. As with so much of the America story there are still many areas of uncertainty. The machines were now called H-12 Large Americas, the earlier boats being termed Small Americas. Curtiss also mentioned an H-9 being supplied to the British but this flying boat has proved elusive and has not been identified to date.

The rest of the boats under the contract were delivered without engines at a price of $16,200 each with propellers, and $15,930 each without propellers. By replacing the Curtiss engines with 250-hp Rolls Royce Eagles the loading was reduced from 27 to 18 lb/hp. The Large Americas were eagerly awaited at operational stations and they soon proved their worth.

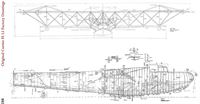

The results of testing and operating the new boats by the British were disappointing in some respects. Their hull was structurally weak. Capt A.E. Bolton recorded the disadvantageous of the H-12 in his post-war recollections. (See Appendix No.). Capt David Nicolson considered that the H-12 “was probably the worse example of boat building that could be imagined, it having no less than four consecutive planks butted - not even scarphed - on the same timber, which had a siding of only 3/8 inch, the line of the butts being in line with the step, where the boat was naturally weakest.” Therefore 8650 became the candidate for a new Porte hull. With this hull it was known as the Porte II and was to prove successful. It performed a number of patrols before being sunk on 30 September 1916. The development of the Felixstowe boats from the Curtiss boats is detailed in Chapter 2.

According to Maj Vernon the H-12 was followed by the H-12A, the name given to the improved H-12. The chief change between the two being a larger tank capacity and better accommodation for the observer in the bow with provision for a gun ring. They also had a revised cockpit canopy. USN documents indicate that the H-12B had a considerably larger horizontal stabiliser and elevators. The USN version with the Liberty motor was the H-12B. It has also been reported that some British H-12 boats had a wider centre section in order to fit Sunbeam Cossack engines. According to the Appendix XLI of the “War in the Air”, the H-12 with Porte hull was known as the “H.12 Converted Large America.”

Early boats had a pillar mount for the bow cockpit machine gun. Later a Scarff ring was fitted with single or twin Lewis Guns and a revised cockpit enclosure. Changes were built into the boats as they were manufactured and after delivery. With the ability to carry four 100-lb bombs, or two 230-lb bombs, an operational ceiling of 11,00 feet and a speed of 85 mph, the H-12 offered the British a boat that was vastly superior to any previous model. Notwithstanding the problems that soon were evident, including a lack of defensive fire to the rear and an inherent structural weakness in the design in that it tended to be damaged on takeoff, the boats soon proved their merits.

With an endurance of eight hours, the H-12 could make scouting flights half way across the North Sea. They could operate in rough water that would prevent the floatplanes that equipped the RNAS from operating. The H-12 could also reach the southernmost position that the Zeppelins patrolled.

The size of these boats meant that new lessons had to be learned. Getting the boats on their trolleys was never an easy task except in a calm sea, and the tails of these boats were so weak that the least touch of a hard object punctured them. While experience was being gained a number of hulls were damaged by fouling their trolleys on the slipway.

The phrase “nothing further was seen” is continually repeated in the reports of marine aircraft on their long, lonely patrols. These two patrols were not the norm in that they sighted a submarine even if they could not carry out an attack. 8677 was to be lost on 24 April 1918, Claimed by Oblt. RMS Christianson. 8689 suffered a similar fate being shot down on 4 June 1918. The crew were interned in the Netherlands, their boat becoming L-1 in the Dutch Navy.

As a school machine the H-12 boats were not good, the tails being stove in or damaged in one way or another by ham-fisted students. Nevertheless a great deal of training was carried out with these boats.

The planning bottom, besides being efficient, was stiff compared with the rest of the hull structure. The bows would meet the seas with very hard blows, and cases occurred where the body of the boat could not stand up to the sudden loads. When this occurred the structure failed in compression at the sides and top of boat forward of the wing roots; yet at the same time, some hulls stood up extremely well to adverse conditions.

Apart from the local weakness, the tails developed a curious general flabbiness, particularly those boats which had been down at sea and towed home. It showed itself by unexpected variations in nose or tail heaviness. A machine would start out all aright and after a short while in the air, suddenly be found to be out of balance.

Some of the tails developed a twist, and as there was no method of trueing them up, the tail plane stays had to be made longer or shorter, to get the (tail) plane horizontal. These changes alas, were not permanent.

One point in favour of these hulls was the bulkheading in the tail. On more than one occasion hulls damaged on landing at sea, were kept afloat for very long periods, enabling the crews to be rescued. The most striking case, was that of a leaking machine, being kept afloat in the North Sea for four days.

Out of a total of 360 completed three to four hour antisubmarine patrols from Felixstowe, only 11 forced alightings took place, and several of these were only through such defects as oil or water pipe joints failing. Maj Vernon recorded that it was “really the Rolls Royce engines that saved the situation.” Even Rolls Royce engines could have their problems as flying boat pilots at Killingholme recorded that the reduction gear would shear right off some of their Eagle motors.

Capt A.E. Boulton recalled the introduction of the H-12 and how it changed the situation in the North Sea. His full reminiscences are given in Appendix No. They were an immediate success in anti-submarine work and against Zeppelins. He also was aware of their deficiencies and considered that the E2A as developed by Porte overcame the majority of these.

The H-12, along with the Porte Baby, was declared obsolete at the Armistice, the Felixstowe boats taking over the roles pioneered by these earlier boats. Small America 3549 was shipped in September 1918 to the Agriculture Hall, Islington, “for storage for exhibition after the war,” arriving on the 23rd minus planes & engines. Unfortunately none of these boats were preserved.

The USN and the Curtiss H-12

The USN was interested in the Curtiss boats developed for the British and ordered a single example, Bureau No. A-152. This machine did not have a position for the gunner/observer in the bow, and it is thought that this machine was probably in the same configuration as the H-8 delivered to the British although only references to the designation H-12 has been found in official documents.

A-152 had a long development time as it was delivered to Pensacola in March 1917 with a Curtiss Company crew judging from photographs taken at the time. On 10 May it was reported as having its Curtiss engines fail while on trial. At the end of July it was still awaiting trials. During the following month it was reported as having dual control installed and by the 30th the repairs and alterations were practically complete. Lt B.L. Leighton flew a test in A-152 while the machine was being readied for its acceptance trials. In addition to Ens Cheney and Mr Schaeffer, a Curtiss representative, Mr King, was aboard. The flight of 30 October ended in a crash from which the passengers survived but only the two engines and self starter was salvaged. Leighton testified that the machine was unairworthy but he was blamed for the crash.

In September the British had agreed to release to the USN from the H-12 boats under construction by Curtiss boats No. 10, 11 and 12. The USN H-12 boats were used mainly for training although it was found that the smaller Curtiss F-Boats were more efficient and did not suffer as much damage from students due to their better construction.

Later Large America Boats.

Porte worked with the H-12 to develop a new hull and this emerged as the Felixstowe F.2A, probably the best flying boat of the war. This was further developed into the F.3 and F.5. The Felixstowe F.2A and F.3 boats were all known as Large America boats. The last Curtiss-built Large America, the H-16, was the F.2A modified to take the Liberty engine. Being Felixstowe designs they are beyond the scope of this chapter but the importance of the Curtiss flying boats to the British antisubmarine effort cannot be under estimated.

A secret memorandum of February 1917 on future policy for the RNAS noted that the Porte Baby flying boat was not being proceeded with, and the Large America Type would be the patrol boat for the future. Unlike the Porte Baby flying boats that could only be accommodated at Felixstowe and Killingholme it was stated that although the Large America boats required fairly large sheds and slipways, they could be accommodated at the following stations: South Shields, Killingholme, Yarmouth, Grain, Calshot, and Felixstowe.

Post-War Claims with Respect to Curtiss Flying Boats.

Rodman Wanamaker made a claim against the Aircraft Manufacturing Company (AMC) for royalties for flying boats produced by that company during the war. The papers for the case reveal that a Mr William E. Wood, acting for Wanamaker, entered into an agreement with the AMC on 13 November 1914, whereby the AMC agreed to prepare and complete plans and specifications for the construction and completion of a seaplane in accordance with the ideas and schemes of Wanamaker, and that such plans and specifications would be the sole property of Wanamaker. Any seaplanes built by the AMC using these plans and specifications built in the next five (5) years would entitle Wanamaker to a royalty of 10%. A second agreement of January 17, 1917, was along similar lines.

The AMC stated that it did utilise these plans and specifications but solely in connection with the construction of “certain craft we were ordered by and supplied to” the Royal Navy. A Minute in the file notes that “it may be suggested that these designs in fact were the production of Colonel Porte whilst he was in the Service, and that Wanamaker got them from him.” In any case it was clear that Wanamaker was not acting as an agent for, or with authority from, the Curtiss Company.

The history of the America boats as related in the files concerning these claims is at odds with actual events. The file states that Porte brought over the Curtiss flying boat and claimed the design as his own. He sold the America, boat to the Admiralty, then altered the design and got the AMC to build boats to this design, and that he convinced Wanamaker to finance the building of the “second boat”.

Porte was instrumental in the RNAS obtaining the Curtiss America and its sister ship, but as has been related, the order to purchase came through official channels and Porte was asked to carry out the negotiations. While Porte did claim in his application to the Royal Commission on Awards to Inventors, that he had designed the America flying boat and the Curtiss H-8/H-12, in truth he probably only had input into both these designs, Curtiss engineers and Glenn Curtiss himself made the changes that were to improve the original America and made it a success. These changes, such as the fins, were the subject of patent applications by the Curtiss Co. Likewise, Porte’s claim to have designed the H-8 is probably an overstatement. He no doubt produced the specification that led to the H-8 and his work with the first one delivered to Felixstowe led to the successful H-12. It is known that Porte worked with his American contemporaries when the US entered the war, and the Curtiss engineers also worked closely with the USN’s Bureau of Construction and Repair. There was a constant sharing of information; the Curtiss Company sharing information with Porte and his Felixstowe team before the US entry into the war.

The statement that Porte had convinced Wanamaker to finance the building of “this second boat” is not clear, but appears to be in relation to the design that the AMC built. If the boats were ordered by the RNAS why would Wanamaker have to finance the building of the machines? What evidence was produced that led to the statement that Porte had Wanamaker finance the building of “the second boat”? Was the relationship between Porte and Wanamaker in carrying out this contract a means of avoiding Curtiss’ patents? Given Wanamaker’s continuing relationship with Curtiss and his further contracts with Curtiss to build a trans-Atlantic flying boat, it is not clear why he would be involved in a scheme to get around Curtiss’s patents.

The hulls of the “America” boats ordered from the AMC were not completely replicas of the Curtiss design. The hulls were built by Saunders and were of different construction to the Curtiss design. The Crown acknowledged in the file notes that the boats built by the AMC were possibly the basic Curtiss design improved by Porte “when in service of (the) Crown.” The contract with the AMC allowed for the Admiralty to pay “all reasonable costs” plus a profit margin. Therefore if Wanamaker’s claim against the AMC was held to be valid, then the Crown would most likely be liable for the amount. These boats were already included in the Curtiss claim and the whole issue was very complicated. It was further complicated by a claim by the Norman Thompson Co that covered some of the aircraft in the Curtiss claim, as well as Mrs Porte’s claim.

The Crown was unable to state who was entitled to these designs, whether Wood (and Wanamaker) or Curtiss, or Porte, until the action was tried and the alterations by each of them were worked out.

The reason for the second agreement between Wanamaker and the AMC is not known.

4. The America Flying Boats in Combat

The Curtiss H-12

The raids of the German Navy Zeppelins against the UK are well known; however, the airships were also used for mapping mine fields and for long range reconnaissance ahead of the German fleet. As the German High Seas Fleet was smaller than the British Grand Fleet, to have advance warning of the location of the British ships was a decided advantage for the Germans. The year 1916 saw the Battle of Jutland and while the question of whether it was a victory or stalemate will no doubt be fought forever, the influence of air power in the battle can be summed up as being totally ignored by the commanders involved.

The arrival of the Curtiss H-12 came on the scene at the correct moment in the war as the Germans had standardised the production of U-boats and they were being produced in large numbers from their ship building yards in 1917. An unrestricted submarine campaign had been announced by Germany in February with British losses in shipping increasing accordingly. The Large America boats gave the British a weapon to use against the U-boats and Zeppelins. Felixstowe developed and operated the Spider Web. This was a patrol zone 60 miles across that allowed for searching of 4,000 square miles of sea and was right across the path that the German U-boats had to take.

The Spider Web Patrol was based on the (Netherlands) North Hinder light vessel that was used as a central point. It was an octagonal figure with eight radial arms thirty sea-miles in length, and with three sets of circumferential lines joining the arms ten, twenty and thirty miles out from the centre. Eight sectors were thus provided for patrol, and all kinds of combinations could be worked out. As the circumferential lines were ten miles apart, each section of a sector was searched twice on any patrol when there was good visibility.

The Spider Web covered the North Sea, St Georges Channel and the English Channel. The flying boats from Felixstowe would fly out to the Spider Web, fly a radial arm as per their instructions, and return to base.

The other method used was the “Sweep Patrols.” In these patrols “machines flew abreast at varying intervals depending on the visibility and the degree of enemy aircraft activity. In the southern part of the North Sea this distance rarely exceeded five miles.” The Sweep method covered an area more thoroughly and efficiently when three or more machines were employed, providing that the distance between machines was not too great, enabling them to close on the leader in the event of attacks by enemy machines. “If the sweep could be arranged to embrace land-falls, lighthouses, buoys or any other aids to navigation, its value was greatly increased.”

The best height to patrol at was between 800 to 1,000 feet. Any higher and it was not possible to detect a submarines periscope unless the submarine was moving at high speed, and then only under average sea conditions. At lower altitudes it was not possible to successfully deliver an attack as the submarine could submerge after being spotted, and it was impossible to make use of your height to arrive quickly over the objective. The attack had to be delivered as soon as possible and this “was accomplished by diving full out at the target, and levelling up only in sufficient time to allow the machine to settle on a steady course and set speed.” By these tactics the bombs would be dropped at the height compatible with safety and efficiency, never under 300 feet.

In the North Sea when a submarine totally submerged it was not possible to locate it by the air bubbles from its ballast tanks, therefore the chances of a successful attack more than two minutes after it dived were remote.

The morning of 13 April 1917, saw the inauguration of patrol flights from Felixstowe. H-12 serial 8661, to be affectionately known as Old ’61, was run down the slipway into the water. The 1st pilot was Billiken Hobbs with Pix Hallam as 2nd pilot, together with a wireless operator and engineer. They flew the first patrol of the Spider Web. No submarines were spotted but they had proved that the new boats could undertake these long patrols under normal conditions.

Basil Deacon Billiken Hobbs from Sault Ste Marie, Ontario, was “short, stocky, and with plenty of energy” and “was one of the best boat pilots in the service.” He possessed those qualities that a good boat pilot needed - able to handle his boat under any circumstances, a good navigator, a tireless observer, a man with sea sense and seamanship, good physical stamina or nervous staying power, one who could endure monotony and wait for the correct opportunity and recognise it when it occurred. Many Canadians served in the RNAS and were involved in operations of the Large America boats in greater proportion than their numbers would suggest. During the last eight months of 1917, three-quarters of the boat pilots flying from Felixstowe were Canadians. They have left a rich mine of material on the activities of the Naval Air Stations. Hobbs would receive two DSC for attacks on enemy submarines. Post-war German records revealed that there were no U-Boats lost on the days of his attacks. This was quite common for claims made against submarines in the war and reflected the technology of the age. The weapons were not sufficiently powerful to destroy a submarine on their own. Hobbs became Chief Instructor on the Large America flying boats for many British, British colonial and US Navy airmen. Hobbs joined the Canadian Air Force in 1920, resigning in 1927 when he established an importing business in Montreal. During his time in the service he made many long-distance survey flights. Recalled to the RCAF in WWII he was commissioned Group Captain and served in Nova Scotia on convoy and antisubmarine patrols. He died in 1963.

Theodore Douglas Pix Hallam was also a Canadian, hailing from Toronto. He had learned to fly at the Curtiss Flying School at Hammondsport, NY in early 1914. On the outbreak of war he volunteered his services to the Army and the Navy as an aviator but was turned down as the war would be soon over. In order to get into the war he enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force and was shipped overseas with the first Canadian contingent. He transferred to the RNVR when in the UK. Wounded at Gallipoli he won the DSC. He then went into the RNAS but was not to fly because of his wounds. Using his nickname Pix he wrote the classic The Spider Web that tells the story of the air war from Felixstowe Naval Air Station. He had been banned from flying because of his wounds but went ahead anyway and flew combat missions. He won the DSC twice more on anti-submarine flights. He won a bar to his DSC on 23 April 1917, for an attack on a U-Boat in 8661, but again, the Germans recorded no U-Boats lost on this day. As a Major in the RAF, Hallam flew the last Felixstowe boat, the Fury, with 24 passengers aboard, 5,000 lbs of sand and fuel for seven hours.

On 15 April the War Flight sighted their first submarine, again it was Old ’61 with Hobbs as 1st pilot. Unfortunately the 2nd pilot had not been trained in bomb release and failed to release the bombs. On the second pass he again failed to pull the release levers but pulled the Bowden cables pulling them from their fastenings. As a result the attack was aborted, the U-boat getting away with only a scare. Hallam does not record what the infuriated Billiken said to the unfortunate 2nd pilot. Success was achieved on the eighth patrol when Monk Aplin dropped his bombs on the wake of a submerging submarine. Attacks on submarines were to continue.

On 24th April, Calshot reported that Flt Lt C.L. Scott with Flt Sub Lt J. Phillip Paine (observer) and crew attacked an enemy submarine while on patrol from Portland to Calshot while flying Large America seaplane 8655. This was one of the H-12 boats of the first batch that had been originally ordered as H-8 boats. Paine reported that their

course was South, submarine heading West and when first sighted was about 1 mile ahead, the visibility being bad. We immediately prepared to attack, and the submarine at once got under way, proceeding West and diving. The pilot of the machine, Flight Lieut. C.L. Scott, carried out my directions for steering immediately over the enemy craft. Two 100 lb. bombs, delay action fuze, were dropped, the first one falling on the enemy’s port beam slightly ahead of his conning tower, about 5 feet away from it, and exploded just as the enemy craft became submerged. Our machine was then turned in a very small radius and a second bomb was dropped which exploded about 50 feet West of the first one, in the direction in which the submarine was heading.

The machine remained circling around for about 30 minutes and during the whole time large quantities of oil were coming to the surface. Large bubbles were seen coming up among the oil during the first few minutes, the bubbles subsequently got fewer but were coming up at odd intervals for a long time. The bubbles were at least 6 feet in diameter, being regular upheavals.

The crew thought that they had sunk the enemy, but it resurfaced about an hour later and was attacked with depth charges by a destroyer that then claimed they had sunk the submarine but the U-Boat eventually returned to base.

Patrols were instigated from Fishguard, Land’s End, the Scillies and Plymouth. These were supplemented by mid-Channel patrols from Bembridge, Calshot, Portland, Newhaven and Cherbourg.

On the 26th Flt Lt C.L. Scott reported that he left Calshot at 11:10 am (GMT) with Flt Sub Lt EE. Fraser (observer); AM 1 H.G. Renett (engineer) and AM2 C.S. Lacock (WIT operator). At 11.55AM (G.M.T.) a submarine was sighted...on the starboard bow, my course being Easterly. The submarine was awash and stopped, about 2 miles away.

I proceeded to attack, submarine at once diving, and when still about half a mile away, she was practically submerged. One 100lb bomb was dropped over the spot where submarine was judged to be. She had been submerged for about 20 seconds. I then circled round in the vicinity for about 30 minutes, and nothing more was seen of the submarine; I then proceeded on patrol and remained away from the position for about 2 hours with the object of giving the submarine time to re-surface.

At 3.47PM I had returned to the vicinity and again sighted the submarine... about 2 miles on my port bow. My course being Westerly, I proceeded to attack and the submarine again submerged. Two 100lb bombs were dropped, the first of which was seen to explode directly over the submarine, as indicated by the wake which was still visible.

I am of the opinion that as a delay fuze was fitted to the bombs it is most probable that the submarine or its periscope were damaged.

I was then forced to return to Calshot owing to lack of petrol.

The observer and remainder of crew carried out their duties with great coolness.

The CO of Calshot wrote that he considered that this officer and the other members of the crew carried out this attack in a very creditable manner and I think great praise is due to Flight Lieut. Scott as this is the second occasion within four days that he has succeeded in attacking a submarine with this machine.

The first day of May saw Perham and Tinyxi from Felixstowe attacked by a twin-engine German floatplane. Encounters between the boats and the floatplanes were to continue eventually seeing large numbers of both engaged in aerial combat as the fight for aerial supremacy in the North Sea grew in intensity in 1918. The Tiny referred to by Hallam was Canadian John Osborne Galpin, so named because of his generous proportions. Not to be confused with the British Capt CJ. Galpin who was also a big boat pilot, Tiny Galpin suffered for a string of bad luck being denied successful attacks on U-Boats by mechanical failures such as that on 22 December 1917, when the bombs failed to explode. He became comfortable with being let down by his engines and spending a night at sea. On one occasion the destroyer that was to tow him home rammed the flying boat, sinking it instead. He was so depressed by his bad luck that his squadron mates gave him a pebble in a small silk bag with the tale that it was an Egyptian talisman, and thereafter his luck changed.

The 13th of April was also an important day for the Great Yarmouth NAS as they received their first H-12 serial 8660 flying boat on that day. It was to be 1 May before the first patrol was flown. On 5 May 8666 arrived at the station. This boat was to go on to become the most famous flying boat of the R.NAS during the war. Her illustrious career commenced on the 14th, only nine days after her arrival at Yarmouth.

With a crew of Flt Lt Christopher J. Galpin (1st pilot in command), Flt Sub Lt Robert Bob Leckie (2nd pilot), CPO V.F. Whatling (W/T operator), and AM J.R. Laycock (engineer), 8666 left at 3.30AM armed with incendiary ammunition on an anti-Zeppelin patrol. A Zeppelin was spotted at 3,000 feet below the boat that was at an altitude of 6,000 feet. They dropped their bombs to lighten the boat and Leckie took over the controls. Galpin moved to the forward cockpit to the twin Lewis guns mounted parallel in the bow. Diving at the airship Galpin opened fire and within a short time the whole airship was a glowing mass that fell into the sea. The airship was L.22 and she had been looking for mines off Terschelling.

After returning to base and reporting their success, their Squadron Commander wrote that he considered the conduct of the officers and crew were “deserving of the highest praise considering the long flight there and back, their successful navigation, the unfavourable weather conditions, the weather being thick and hazy with frequent rain, and their determined and successful attack.” Galpin was awarded the DSO, Leckie, the DSC, Whatling and Laycock the DSM. The letter to their Squadron Commander noted that these “honours will be gazetted, but particulars of the service will not be mentioned.” Importantly, the Germans did not realise that the British had a new potent weapon and attributed the loss of L.22 to thunderstorms that prevented the airship from ascending to a safe altitude and she was brought down by fire from British warships. 8666 was to have six subsequent encounters with Zeppelins.

In June the Large Americas were “proving very successful for patrol work and the only difficulty that was being experienced was in teaching new pilots to fly these machines owing to the fact that no dual control was fitted. It was hoped that dual control would be fitted in all the newer machines now on order.” Longmore also reported that one machine was being tested with the engines turning right hand rather than having opposite turning engines “as has always been the case in the past.” With a larger tailplane and slightly more incidence on one wing the boat was quite comfortable in the air. If successful this would “greatly relieve the position as regards the production of these engines.”

The Germans were still unaware that a new weapon had entered the war when, on 14 June, Felixstowe also had success. Five Zeppelins took off to operate in the U-boat blockade area to cover minesweepers dealing with a British minefield 40 miles north of Terschelling. British radio intercepts saw Large America 8677, with crew of Flt Sub Lt B. Billiken Hobbs, with another Canadian, Flt Sub Lt R.EL. Dickey, as pilots, AM2 H.M.Davis (W/T operator), and AM (E) A.W. Goody (engineer), leave at 5.15AM and fly to near the Dutch coast at Vlieland. At 8.40 they were again off Vlieland and sighted a Zeppelin about five miles off their starboard bow at about 1,500 feet. 8677 was at 500 feet and immediately climbed to 2,000 feet to attack. Hobbs was piloting, Dickey manned the bow gun, Davis manned the midship gun and Goody the stern gun.

As we approached the Zeppelin we dived for her tail at about 100 knots. Her number L.43 was observed on the tail and bow, also Maltese Cross in black circle. Midship gun opened fire with tracer ammunition and when about 100 feet above Sub-Lieut Dickie (sic) opened fire with Brock and Pomeroy ammunition, as the machine passed diagonally over the tail from starboard to port. After two bursts the Zeppelin burst into flames. Cutting off engines we turned sharply to starboard and passed over her again; she was by this time completely enveloped in flames and falling fast. Three men were observed to fall out of her on her way down. Flames and black smoke were observed for some time after wreckage reached the water. We set course for Felixstowe arriving at 11.15AM.

So ended the three month service life of the L.43 with the loss of all her crew.

As a result of this action the Germans ordered a minimum altitude of 13,000 feet for its Zeppelins, thus reducing their effectiveness. The British fleet was harboured at Scapa Flow and if the German heavy ships sortied for a raid on the British coast then it took some time for the fleet to come down from Scapa Flow. British submarines were positioned on the exits from the mine fields protecting the Bay of Filygoland. They were to give warning if the Germans sortied; however, with the Zeppelins able to cruise at around 1,000 feet, the submarines were in a difficult position as they could not come to the surface to carry out their duty. Now that the minimum height of their patrols had been raised the Zeppelins could no longer harry the British submarines. Also the airship crews suffered as they described these patrol flights as strenuous as a flight against England.

Not all operations against the Zeppelins were successful. 8666 was on a reconnaissance patrol on the morning of 24 May 1917, when, after about two and a quarter hours, she was at 1,200 feet owing to the low visibility and

a super-Zeppelin with three cars and five propellers suddenly appeared out of the cloud at 2000 feet coming towards us about one mile away; on seeing us he dropped two white flares, we did not answer this signal but put on full speed, dropped our bombs and climbed up at him. He then turned quickly through 16 points and started to climb hard. When he reached 3000 feet we had gained on him and were actually 300 yards astern. He threw out a smoke screen (probably a discharge of water ballast. Authors note.) under cover of which he gained the main bank of clouds; it was not feasible for us to follow him there. As he disappeared I fired half a tray of Brock, Pomeroy and Tracer into him, but was unable to observe the effect.

I would point out that we were easily overhauling him on climb, and had the clouds been a thousand feet higher would undoubtedly have made certain of him.

We then climbed through open spaces until we reached the top of the cloud at 10,000 feet, the boat being under light load, and continued W.S.W until 8.40AM. Without sighting any more Zeppelins, when no land being yet in sight and petrol being very low we descended near some trawlers to enquire our position. We found this to be Cromer Knoll, and we were taken in tow by H.M. trawler Curvia who transferred us to H.M. Trawler Rialto which towed us towards Yarmouth. We were later transferred to P.25 who brought us into Yarmouth.

The P.25 was a P-Class patrol boat made to represent a German submarine travelling on the surface. The hope was to lure a German submarine in close such that the patrol boat could attack.

8666 continued being active on anti-submarine and anti-Zeppelin patrols. In August 1917 two De Havilland D.H.4 land machines arrived at Bacton, the landplane satellite for Great Yarmouth. These machines with extra large fuel tanks for a 14 hour flight as they were originally planned to be used for a reconnaissance of the Kiel Canal but this never took place. The D.H.4 was a single engined, two-seat bomber that was a fast and high climbing biplane. With the bomb gear removed and flotation bags fitted and extra tankage the D.H.4 had an endurance of six to seven hours. The Zeppelins now operated at an altitude that the Large America boats could not reach, and so the D.H.4 would go on an anti-airship patrol with an accompanying flying boat to undertake the task of accurate navigation and to be available to effect a rescue should the landplane have to come down in the sea. On 4 September 1917, 8666 undertook such a task accompanying a D.H.4 in a hunt for Zeppelins. The patrol was aborted due to fog. The next day special D.H.4 serial A7459 flown by Flt Lt A.H.H. Gilligan, with Flt Lt G.S. Trewin as his gunner in the rear cockpit, was accompanied by 8666 with Flt Lt Robert Leckie (pilot), AM Thompson (W/T operator) and AM Walker (engineer), and with Sqn Commander V. Nicholl in overall command.

Nicholl reported that around noon when the pair was about 30 miles from Terschelling

A Zeppelin was sighted 25 miles North West Terschelling Island, steering S.E. I altered course to intercept the Zeppelin, H.12 9,000 feet, D.H.4, 10,000 feet, and Zeppelin 10,000 feet. I signalled the D.H.4 to climb as high as possible to attack the Zeppelin.

At 12.30PM, I opened fire on Zeppelin, our altitude was 12,000 feet and Zeppelin 14,000 feet. She dropped water ballast, and climbed still higher. The Zeppelin number was L 44. I continued attacking unsuccessfully for one hour, firing 400 rounds of Anti-Zeppelin ammunition. The tracers were seen hitting the Zeppelin. During most of this time we were subject to a heavy machine gun fire from the Zeppelin. The Zeppelin, in the meantime, led me over a squadron of two light cruisers and four destroyers, who did not open fire, presumably on account of the proximity of the Zeppelin. The D.H.4 was some distance away, and endeavouring to climb higher and at 1.30PM signalled me that his engine was not pulling well, and he could not climb any higher than 14,000 feet. I then signalled him to close and attack the Zeppelin, which he did without result. At 2.0PM the D.H.4 signalled me that he had serious engine trouble and I signalled him to follow me and we would attempt to make Yarmouth. On passing Vlieland on a course 255° another squadron of two light cruisers and four destroyers were sighted, who heavily shelled us, making very good shooting, fragments of shrapnel damaging the starboard wing. A large group of mine sweepers was sighted at Texel Island.

While attacking the L 44, a second Zeppelin was sighted about 10 miles to the Northward, steering a S.Easterly course at an altitude of approximately 10,000 feet. She made off for Borkim (sic) Island at high speed, and did not attempt to assist the L 44.

After the war it was learned that the other airship was the L 46 and she had seen the attacking aircraft. “The attack was well planned, in so far that the machine had the sun behind it, and therefore could only be seen with difficulty by those aboard L.44." L 46 immediately warned L 44 by wireless of their danger and that airship dumped ballast to ascend to a safe height.

At 3.30PM when about 50 miles E by N of Yarmouth, the D.H.4 engine failed completely, and the machine crashed into the sea. I immediately landed in the H 12 alongside the D.H.4, and with difficulty, on account of the sea, picked up the crew.

The D.H.4 sunk almost at once. As the state of the sea made it impossible to get off again and the port engine was not giving its revolutions, I taxied towards Yarmouth till 7.0PM, when I ran out of petrol.

8666 began to fill with water as she had a hole near the step caused by anti-aircraft fire. Bailing was started with empty petrol tins hastily converted to bailing buckets. The short, steep sea lifted the tail up, pushing the bow down allowing water to pour into the cockpit. Leckie had to change course and hoped to meet the War Channel near Cromer but the fuel gave out and the boat was adrift. During the night the starboard wing tip float carried away and the men took turns from bailing by “resting” for two hours on the port wing to keep the starboard wing out of the water.

Two of their four pigeons were released, the message from one reaching Yarmouth on Saturday 8th. On Wednesday evening fuel ran out and the boat now drifted at the mercy of the sea. The boat continued to drift. Another pigeon was released on the 6th but was never seen again. On the afternoon of the same day, the last bird was released. This pigeon arrived at the air station at 10:45 am the next day. This proved that the crews were still alive and the rescue attempts were continued, but in the wrong locations. It was discovery of the message of the 5th that was to lead to the rescue of the missing aviators. The pigeon that had been released on the 5th had fought its way to shore but had died. Its body was found by chance by an office of the 4th Battalion Monmouthshire Regiment on the beach at Walcot and the message passed on. This message led to the search moving to the north. It read:

GOVERNMENT PIGEON SERVICE

H-12 No. 8666, Sept 5th, 4.00PM.

We have landed to pick up DH4 crew, about 50E by N of Yarmouth. Sea too rough to get off. Will you please send for us, as soon as possible as boat is leaking. We are taxiing W by SS.

V Nicholl

At 12:42PM on Saturday 8th, the old gunboat, HMS Halcyon, whose task was patrolling the Norfolk coast, found the missing’ boat with the two crews still alive. In the words of one of the D.H.4 crew:

With H.12 proceeded to Terschelling: in action with Zepp L.44 and four squadrons of light cruisers, destroyers and minesweepers; fought Zepp for 1 1/2 hours and obtained photos and naval reconnaissance. On return journey engine seized up and we finally crashed into sea at 3PM. H.12 picked us up and taxied until petrol ran out at 9PM. We then drifted about the ocean until 2PM on the 8th when Haleyon (sic) picked us up. H.12 leaked and continual bailing was necessary; floats got water logged and we had to take turns in laying down out on wing tips. We had no food the whole time and our water ration was a wineglass full each diem.

The men were on their last resources when rescued. Having no food and only two gallons of fresh water, they had to drain rusty water from the radiators to slake their thirst. Despite the pounding she had received 8666 was salvaged, made serviceable again, and returned to Zeppelin hunting. The pigeon was stuffed and displayed in the Yarmouth Mess above the inscription: “A very gallant gentleman.” He now resides in the RAF Museum.

After the men were rescued an analysis was made of the patrol. It was considered that “further tests should be made with the engine of the other D.H.4, and see is these are satisfactory, that the experiment should be made again.” Attached to this memorandum was the following:

It will be seen that complete success was only frustrated by a very small margin. Had the engine of the D.H.4 lasted another hour, which it should certainly have been expected to do, I think destruction of one, or both Zeppelins, would have been accomplished.

The ammunition again seems to have been unsuitable for the purpose for which it is intended.

There were discussions on the suitability of the ammunition used following on from these reports. The ammunition used was a mixture of Brock, Pomeroy and Buckingham, “and it appears that the range was too long for these bullets to function.” Every effort was being made to increase the range of the ammunition. It was also proposed that “a .45 double barrelled express rifle should be carried in each large America and trials of some Brock ammunition should give a greatly increased range are nearly completed.” No documentation of such a rifle being carried by any Large America has been found.

Four Rolls Royce Eagle VIII engines were sent to Yarmouth to be fitted into two Large America boats

and it is hoped that these machines will then be able to attain the altitude of the Zeppelins.

In the meantime, further tests should be carried out with the engine of De H.4 machine No. A. 7457 and, when ready, this machine together with the two large America flying boats should be sent out on anti-Zeppelin patrols as suitable opportunities present themselves.

Two additional De H.4 machines, Nos. N.6395 and N.6396, have been allocated to Yarmouth for these patrols.

Another incident involved Curtiss H-12B N4340 that was forced to alight in the Channel while on patrol on 14 May 1918. The following day, while on “Z” patrol in Short 184 N1795, Lt Hope, with Wireless Operator and Observer A.E. Ingledrew, saw N4340 on the water. Hope landed and attempted to convey my emergency rations to her, as she was in need of food. I attached these to a life-belt, and dropped them as near her as I could. Lieut. Oldridge swam out and reached them but was seized with cramp; I picked him up with my wing tip, and having let go my bombs proceeded to Cherbourg.... landing at 1850.

Seaplane 4340 had caught fire in the Port engine, and the flames had spread to the whole of the lower plane, which was badly burnt.

Hope had picked up one of the crew and flew him to Cherbourg. Immediately on arrival of N1795 with the location of the H-12B N4340, the Senior Patrol Officer, RAF Cherbourg proceeded at 1910 in Wight Seaplane 9854, without bombs or passenger, towards the position that Hope had reported finding the Large America boat. At 1950 he sighted the H-12B on the water with seaplane F.2A N4543 circling over it and alighted and taxied close to the damaged machine. The sea was choppy and he had no way of re-starting the engine single handed as the starting magneto was in the pilot’s seat, away from the starting handle. By flying alone he had hoped to save the crew if they should be compelled to take to the water. Since the situation did not warrant such action he did not attempt to go alongside N4340 but took off and returned to Cherbourg, alighting at 2140 by the light of a petrol flare on a bouy. As he left he saw N4535 alight and take off the remaining crew. N4535 landed outside the harbour at 2200 by the light of French searchlights. The flying boat was then picked up by the Station Motor Boat from outside the harbour in the dark and towed to safety through the boom under very difficult circumstances.

It appears that N4340 may have been salved as it is recorded at Calshot on 25 May and not deleted until the week ending 29 August 1918.

The H-12 flying boats of Felixstowe and Yarmouth did not have all the combats with Zeppelin to themselves, for on 10 May 1918, radio intercepts had given a fair idea of the course of a Zeppelin and F.2A serial N4291, Old Blackeye, left Killingholme at 13.20 in “search of hostile airships.” The crew comprised Capt T.C. Pat Pattinson (1st pilot), Capt A.H. Munday (2nd pilot)33, AAM Johnson (W/T operator); Sgt H.R. Stubbington (engineer). At 16.30 they sighted an airship on the port beam at an altitude of 8,000 feet. The Zeppelin

was about 1,500 feet above our machine and proceeding due east in the direction of Heligoland. I pointed it out to Captain Pattinson and he at once put the machine at its best climbing angle. I went to the forward cockpit and tested the gun and tried the mounting, and found everything worked satisfactorily. The engineer rating immediately proceeded to the rear gun cockpit and tested both port and starboard guns. At this time our machine was at a height of6,000 feet. The hostile craft had evidently seen us first, and was endeavouring to get directly over us in order to attack us with bombs. When at a height of 8,000 feet and the Zeppelin had climbed to a height of 9,000 feet I opened the attack and fired 125 rounds of explosive ammunition. The engineer rating also opened fire and fired about the same number of rounds. The Zeppelin was about 500 yards distant. All our fire appeared to hit the craft and little spurts of flam, our explosive bullets, appeared all over the envelope. I noticed much, what appeared to be water ballast, and many objects thrown overboard and then the nose of the hostile craft went up a few degrees from the vertical, this was, apparently checked by the occupants as the craft righted and commenced to climb as much as possible. I had a gun stoppage and spent many minutes clearing it, being obliged to take the breech of the gun to pieces.

The Zeppelin continued to climb and gain on us slightly and again endeavoured to get directly over our machine. The enemy succeeded and dropped five or six bombs. The engineer rating reported to the first pilot (Captain Pattinson) that seven hostile destroyers were circling beneath us. We were now at a height of 11,000 feet and the Zeppelins height was approximately 12,500 feet. I opened fire again and fired another 130 rounds of explosive and tracer bullets. I noticed the propeller of Zeppelins port engine almost stop and the craft suddenly steered hard to port. I concluded that the port engine had been hit by our gunfire as well as other parts of the craft, as the envelope and gondolas seemed a background for all the flashes of the explosive and tracer bullets. There was much outpouring of ballast and articles and considerable smoke. I concluded that we had finished the Zeppelin and informed Captain Pattison that we had bagged it. But the craft again headed for Holstein in a crabwise fashion emitting much smoke. I had other gun stoppages and one bad jamb. One of the explosive bullets exploded in the gun and flashed into my face and on to my hand but outside of a few scratches I received no injury. Our port engine commenced to give slight trouble and the engineer investigated. He reported that an oil feed pipe had broken and it would not be long before it would break in two. As soon as I had my gun cleared of the trouble caused by the exploding bullet I signalled to Captain Pattinson that I was ready to re-attack and looked for the enemy craft. I saw it still proceeding due east in a crabwise fashion. It was losing height and emitting smoke which was of a black variety though parts of it was pure white. The hostile destroyers underneath opened fire on us and owing to engine trouble and lack of petrol for our return journey, and being only about sixty miles off Heligoland we gave up the attack at 5.35, having been attacking for one hour and five minutes.

The oil pipe broke in tow and we were forced to glide and land in a rough sea. The engineer quickly climbed out on to the top of the engine and repaired the break with tape. Fifteen minutes later we took off. As the machine was difficult to control Captain Pattison asked me to get out and endeavour to ascertain whether we had damaged the rudder or elevator in taking off and in looking back I observed the German destroyers steaming with all possible speed in our direction.

As regards gun jambs: About 500 rounds were fired. Two and half double pans of explosive ammunition were fired from two guns in the after cabin. No jambs occurred, but the gun stopped twice to misfires.

Two double pans of explosive and half a pan of Mark VII and tracer were fired from the forward guns in long bursts. One serious jamb occurred owing to the premature explosion ofa round of Brock ammunition. This premature explosion may have been partly caused by overheating of the gun or it may have been due to a faulty round. The blunt nose of the Brock bullet is liable to cause faults in the feed, and if the sensitive nose of the bullet takes up against the forward end of the feed arm slot may easily premature explosion.

The F.2A often had trouble with its fuel system due to the great length of piping involved. The main tanks were in the hull and fuel was forced up to the gravity tanks in the upper wing centre-section by wind-driven pumps, the engine carburettors being fed from the gravity tanks.

The crew were given credit for the destruction of L62 which fell that day. Actually they had been attacking L56 and had never placed the airship in jeopardy. L62 was seen to enter clouds by surface craft and then falling in halves, one nearly landing on the trawler Bergedorf. Lightning was thought to have been the cause of the disaster. The L62 was the third of the V-class Zeppelins. It had first flown on 19 January 1918.

According to T.C. Pattinson “Poor 4291 went up in flames” on the night of 3 August 1918, as he had left Killingholme for his son George was born on that date, “but that night a wonderful American pilot went to see how much petrol was in the tank. He was unable to see the bottom, so he struck a match, with fatal results.” If this happened to N4291 it was not fatal for the old boat, as it was finally written off in January 1919.35

The actions of the relative tiny flying boats against the giant Zeppelins were colourful but were not made public in order to keep the Germans from realising that their Zeppelins were now in danger. The pilots involved would have been feted by the public as the general population held the Zeppelins in particular odour as terror weapons or “Baby Killers.” The other main tasks of the flying boats were hunting submarines and convoy escort, to be joined by long range reconnaissance missions as the capabilities of the boats were developed. J. L. Gordon considered that the “Curtiss Aeroplane Co. in the U.S.A. were the first to produce a flying boat which, powered by Rolls Royce motors, was capable of performing the many and varied duties required by the navy, with a moderate degree of safety and efficiency. It was the advent of this type of seaplane which altered the whole aspect of the work connected with naval co-operation.”

Despite the number of submarines sighted and bombed there is only one confirmed sinking of a submarine by a British aircraft without surface help for the whole period of the war. This action was fought on the morning of 22 September 1917, by H-12 serial 8695 operating from Dunkirk. This boat, crewed by Flt Sub-Lt N.A. Magor and Flt Sub-Lt C.E.S. Lusk, was to patrol near the German seaplane bases in Flanders and therefore had an escort of two Sopwith Pups. The Curtiss boat sighted and attacked the UB32 that was spotted on the surface. The submarine emergency dived but two 230-lb bombs struck just aft of the conning tower and exploded. UB32, a Class UBII submarine, did not return to base.

The flying boat had been sent to Dunkirk after seaplane operations were cancelled due to the operations of the Zeebrugge Friedrichshafen FE49C and Brandenburg W.12 floatplanes. Magor and Lusk’s H-12 arrived on 11 July. The seaplane pilots that were operating from Dunkirk now flew with escorting Sopwith Pup fighters. Capt C.L. Lambe, the OC Dunkirk, would come into criticism later in 1918 for not arranging for Dunkirk aircraft to rendezvous with flying boats sent out from the UK. (See Chapter 7). This would be another incident whereby the people at the Admiralty had no practical knowledge as to the capabilities of the aircraft in their charge. Aircraft “were mere pawns in the great game contested by the two fleets.”

The importance the Admiralty thought of aerial patrols in combating submarines is given by a Confidential and Immediate Memorandum of 5 July 1918, where in it was stated “a great naval effort is being made during the summer months to attack enemy submarines passing Northabout, and it had been hoped to obtain considerable assistance from air patrols. Their Lordships have been disappointed in this respect, and trust that every endeavour will be made to ensure facilities for the maintenance of efficiency being provided before the summer is over.” This request was made in reply to a report on the Northern Patrol Seaplanes that revealed that in June Houton, Stenness and Catfirth stations had nine Large America boats but none were available for patrol. There were in addition four 240 Renault Short Seaplanes that were worn out and not much use for patrol work. The whole output of F.2A boats was reserved for Home waters, the F.3 going to the Mediterranean.

On 28 September 1917, Flt Sub Lt B.D. Billiken Hobbs, Flt Sub Lt R.F.L. Dickey and crew took off in H-12 serial 8676 at 0720 in answer to wireless intercepts. The British could pick up the German U-Boat traffic and figure out where the submarine should be located and then direct ships and aircraft to that position. Hobbs was looking for a submarine near the North Hinder light vessel. The North Hinder was sighted at 0805 when course was altered south. As a hostile wireless signal had been reported in a position 25 miles south of the North Hinder, the W/T operator listened in and at 0828 reported hostile signals being received by some vessel within ten miles. At 0834 an enemy sub was sighted in full buoyancy about one mile dead ahead. She was painted light grey colour and seemed to have a raised bow and also a mast and a gun. A man was observed forward by the gun. The seaplane increased speed to 80 knots at 600 feet and when about a quarter of a mile away fired two recognition signals which were not answered by the sub. Flying directly over the sub, the seaplane dropped one 230-lb bomb & then turned to repeat the attack, the sub at the same time firing one shell which burst 50 feet in front of the machine. The bomb was observed to make a direct hit on the tail of the sub, the explosion making a large rent in the deck. Whilst the seaplane was turning, a photograph was taken of the sub as she was under the port wing. At this moment several red flashes were observed on the water some distance in front of the seaplane and then through the mist three more enemy subs were seen heading SW in line abreast, and immediately behind them were three enemy destroyers. All six vessels were firing at the seaplane, but their shells exploded in front of the machine. Escorting the destroyers were two seaplanes which, however, did not attack the Large America owing to the barrage put up by the destroyer’s fire. The Large America turned completely round and again passed over the sub which was now sinking by the stern with water up to the conning tower and nose out of the water. The second 230-lb bomb was released and exploded dead on 15 feet ahead of the bow. With the impact of this bomb the whole sub seemed to vibrate, and then sank immediately, leaving a large quantity of blackish oil, air bubbles and foreign matter. The crew were credited with sinking the UC-6, however, again post-war records showed that this was not the case.

8676 delivered to Felixstowe on 15 March 1917, for erection. She had an impressive career and was credited with sinking UC-1 with 8689 and N65 on 24 July 1917, and UB-20 with 8662 on the 29th, and UC-6 as recorded above, as well as two unsuccessful attacks. She sank when under tow by TBD Meteor on 27 December 1917.

The arrival of the Large America boats had another benefit for the RNAS personnel who flew the floatplanes on patrols. Flying floatplanes was always dangerous for if they were forced down through any reason they were unable to stand up to the conditions usually prevailing in the North Sea. This was demonstrated on 24 May 1917, when Flt Sub Lt H.M. Morris and his wireless operator, AM2 G.O. Wright, left Westgate, a seaplane station on the East Coast, south of Felixstowe in their Short 827 floatplane serial 3072. After some hours patrolling over the North Sea, Morris turned for home. His engine began to miss then stopped altogether and he came down on the water. Unfortunately he had alighted in one of the British mine fields. It was a very big mine field, “starting from an east and west line a short distance south of the North Hinder and continued to a line running east just above the North Foreland.” There were no ships in sight and, obviously, not much chance of a ship coming across them.

The sea increased in intensity so Morris dropped his bombs and let the petrol out of his tanks, lightening the seaplane. By four o’clock in the afternoon the wind had increased such that the machine was blown backwards placing the tail float in the waves. “The necessity of a tail float is the weak spot in the design of a float-seaplane, and the sea was attacking the flaw in the design.” The crew took up station on the nose of each float in the hope that they would keep the tail float out of the waves. After about an hour the tail float gave way and inexorably the tail of the machine sank into the water and the machine capsized slowly backwards. The sea then proceeded to break up the machine so that the two were left with only a float to hang onto. The attachment points for the struts that supported the float gave the men a handhold. They were unable to climb onto the float as it was very unstable and so they were lying across it, half in and half out of the water. They clung to the float that night and the next day. The 26th saw a thick fog that eliminated any chance of a passing ship seeing them. By the 27th they suffered from thirst but the sea had calmed such that they could lie on the float. When the machine was wrecked they had suffered cuts and lacerations and these became swollen and inflamed. On the 29th, after spending five nights on the float, they were very weak. At noon the fog came down. They were so thirsty they began to take sips of sea water.

At Felixstowe Hallam ordered two boats run out even though it did not look promising. At 12.17 the boats were put into the water and took off. The fog became so thick that one boat turned back. The other, flown by Flt Sub-Lt G.R. Hodgson and Flt Sub Lt J.L. Gordon, decided to press on. Eventually they also had to turn for home so thick had the fog become. At an altitude of 1,200 feet they were about 12 miles from the North Hinder when they spotted something on the water. Spiralling down to 600 feet they saw two men on a float. A strong wind was blowing and a heavy sea was running. It was obvious that the two men were in dire need of assistance.

Hodgson later recalled:

The first important problem we encountered, was landing a boat in the open sea. A gentle sea swell was running and a very light breeze blowing. The latter probably forced us to contact the water at 50 to 60 knots.

To say we got a bad shaking up is to put it mildly but so far as we then knew no damage had been done.

The first attempt to take the men failed. The boat was taxied up to the float and the engines stopped at the very last minute, however the wind blew them away from the pair on the float. A second attempt was made with two of the flying boat’s crew standing on the fins each side of the bow. Waves were washing up to the waist of these men but they managed to seize Morris and Wright and drag them up to the drift wires that connected from the wings to the bow of the hull.

Inside of five minutes Morris and Wright were in our boat.

Then began the time of decision: Should we try and take off or make a taxi run to the East Coast. We decided on the taxi run, but a few minutes after starting our engines Anderson told us that on landing we had broken a hole in the bottom of the boat and we were taking in sea water. We realized of course we were in a tough spot and our only hope of getting out of it was to take off. Our attempt was not a success and we were compelled to abandon it. One of the things we did was to break the tail plane.

We then returned the taxi run hoping for the best. We got to the shipping channel and there we had the good luck to meet a small cargo vessel which picked up all of us, put a line on our boat and took us back to Felixstowe.

Hodgson had fed the two rescued men brandy from an eye dropper until they were able to take some warm cocoa from a thermos flask. The Orient out of Leith picked up their distress signals and gave them their initial tow. Their bilge pump had failed and they had to bail by hand, and also pump the fuel to the engines by hand. The sea was picked up by the airscrews and thrown over them, coating them with salt. The tow was later transferred to HMS Maratina, while Morris and Wright were transferred to HMS White Lilac and rushed back to port for medical attention.

James John Lindsay Gordon and George Ritchie Hodgson were two Canadian cousins who had been boys together and had come to the UK together, learned to fly together, and when they came to the Felixstowe War Flight asked to be able to fly together. Known as “The Heavenly Twins” they flew together for some time alternating First and Second Pilot roles, but both were good boat pilots and these were in short supply and so they were each given a boat. At first they resented being separated but finally saw the necessity of the move. They had their names bracketed for Duty Pilots and for leave and usually managed to fly their boats in company. On this day they had managed to fly together once again.

Hodgson was had been a champion swimmer. He was a stout fellow in more ways than one, and had been built for big boat work. Gordon was a long-faced, serious lad, not over strong physically, but with tremendous determination and force, and was a careful flying-boat husband. Both men were great grumblers, but also great workers.

Hodgson had won Olympic gold at the 1912 Stockholm Olympic meet in the 400 metre and 1,500 metre swim events. The two Canadians received the British Board of Trades Silver Sea Gallantry Medal for the rescue. Both survived the war, Hodgson with the AFC and Gordon with the DFC. Gordon was to remain in the Canadian Air Force becoming Director from 1922 to 1924, and RCAF Senior Air Officer in 1932. He passed away in November 1939 at the age of 48 years. Within two months Morris and Wright were returned to duty.

Sir Austin Robinson wrote to Hodgson in 1981 that with respect to their rescue of Morris and Wright,

I do not think that you can ever have appreciated yourself what your rescue of them (Morris & Wright) did for all the rest of us who were flying seaplanes over rough seas. I do not have to remind you that in those days it was the sea that was the enemy

and the morale of a station enormously depends on whether pilots who have been lost through forced landings from which they were not rescued. The feeling that in such an emergency your friends would come to your rescue made a tremendous difference to morale.

I had only one forced landing myself in an H12 and I was certainly no more successful than you were (in getting off again). In my case, I got the H12 down in a rough sea without breaking the hull. But we could not get off again and within a couple of hours one wingtip float was broken and the fabric carried away from both lower wings. So any further attempt to take off was out of the question. With two members of the crew sitting out on the wing that still had a wing tip float we taxied safely ashore on to a sandy beach somewhere south of Bridlington.

The design of the H12 was surely at fault. It had a wonderfully strong forebody and the woefully weak monocoque tail which always broke just aft of the step. Any forced landing in an H12 was likely to end in fracture there. Equally Morris would never have been in the predicament he was if it had not been for the bad design of all Shorts. They always stove in the tailfloat and turned topsy turvey in a forced landing in a rough sea.

During October 1917 the weather was so bad that little flying was done from Great Yarmouth. 21 year old Flt Sub-Lt Peter George Shepherd with his observer, 20 year old L Mec Walter Fairnie, were lost in Short 320 floatplane N1360 on the 28th. They did not return from patrol and were never seen again. The next day Bob Leckie, Flt Sub-Lt Bolton, CPO Whatling and AM Walker took off in H-12 serial 8660 to search for the missing aircraft. They came across an enemy submarine when Whatling sighted a conning tower break the surface. Leckie turned to attack but the submarine had dived. Spotting the periscope which popped up for a short time they attacked, Bolton releasing two 100-lb bombs with 2 1/2 second delay fuses, but no visible results were obtained.

8660 had a distinguished career attacking submarines on two occasions and the Zeppelin L46. Wrecked on 6 November 1917, she was rebuilt with a F.2A hull and returned to service in January 1918. She met her end on 30 May 1918, when, with a mixed British and USN crew, she was attacked by enemy seaplanes. On that day F.2A serial N4295 and 8660 left for a long patrol. Ens George Thomas Roe was 2nd pilot to Capt Charles Leslie Young, DSC, in 8660. They were forced down with engine trouble and but were able to signal the other boat by Aldis lamp that the fault was repairable. The F.2A circled while repairs were carried out. After about 50 minutes two German seaplanes appeared and joined combat. The front guns of the flying boat jammed after a few rounds. The German seaplanes turned away and headed for Borkum for reinforcements. The F.2A set off in pursuit but soon realised that it was being led away from its charge. Returning to the area he had left 8660, the boat was nowhere to be seen and so N4295 returned home to Great Yarmouth. A boat was sent out to look for the missing Curtiss. It had not long left when a pigeon was received with the message that 8660 was on the water and under attack.

8660’s crew had repaired the fault and taken to the air again. After about 45 minutes, the boat was again forced to alight. She was on the water when five German seaplanes attacked. The British boat fought back, the attack continuing until the Germans saw three men jump overboard and swim away from the flying boat. A German seaplane immediately landed and the gunner boarded 8660. He found the pilot dead and the mechanic wounded by splinters. Two of the swimmers were rescued, the third disappearing. The boat was set on fire and the Germans returned with their prisoners to Borkum. The dead pilot was Young, and the mechanic who drowned was AMI Henry Francis Chase. Roe, Cpl F Grant and Pte JN Money were taken POW.

Roe was to spend the rest of the war as a POW in Camp Lanschut, Germany. He was awarded the Navy Cross for his part in the action. Roe was killed on 28 May 1921, when he crashed in Loening M-81 monoplane A-5762 at NAS North Island, San Diego. The aircraft was on a test flight at 3,000 feet when it was observed to enter into a series of involuntary spins. Roe recovered from all but the last, striking the beach at terrific speed. His passenger, CMM J.P. Dudley, was seriously injured but recovered.

Upon the report of a Large America boat exploding in the air in the Scillies, Yarmouth reported that there was a noticeable tendency for petrol vapour to mix with air and accumulate in the bottom and tail of the hull and unless the hull was freely ventilated there was the danger of a highly explosive mixture accumulating there. It was noted that Felixstowe was looking at the problem. No modifications to prevent a repeat of this incident have been discovered to date.

Danger was not only experienced in the air. On the morning of 4 July 1917, some 12 hostile aircraft raided Felixstowe Station at 7.25 B.S.T. One bomb fell on the beach close to No.2 Slipway setting fire to the Curtiss Large America 8679, and causing several casualties amongst the ratings. Another bomb fell in the water near the slipway by the old Station, causing no material damage but more casualties. A third bomb fell amongst the new huts being erected across the road injuring two of the contractor’s men.

In all four men were killed; 15 severely wounded, and four slightly wounded. In addition two civilians were killed and two wounded. Curtiss H-12 No. 8679 was completely destroyed and 8682 suffered considerable shrapnel damage. The top part of No.3 Slipway was badly charred for about 12 yards.

The raid was carried out by Gotha bombers under the command of Rudolf Kleine, 18 of the bombers actually made the attack out of the 25 that started out. The Home Defence organisation was laggard in its response and only one aircraft attacked the straggling formation on its way back across the Channel. This was a RAF powered D.H.4, serial A7436, on a test flight from the Testing Squadron, Martlesham Heath. When he came across the raiders the pilot, John Palethrope, accompanied by AMI James Oliver Jessop, attacked the middle of the formation. Coming under intense fire his gunner was hit in the heart and his front gun jambed. Paleathrope returned to land and took off again with another gunner but did not reengage the Gothas. A total of 17 were killed and 30 injured in the raid.

The H-12 in the USN

The USN ordered one H-12 in order to test the type’s possibilities. A-152 was possibly the prototype and was fitted with 200-hp Curtiss V2-3 engines mounted behind circular radiators. Its life with the Navy was short as it was destroyed on 30 October 1917, while being prepared for trials. Lt B.L. Leighton blamed the machine claiming it was not airworthy but the Survey Board blamed bad airmanship and inexperience. The USN ordered 24 H-12B type flying boats and spares. The H-12B was “designed for the mounting the 275 H.P. Rolls-Royce engines,” but events conspired to limit the acquisition of only 19 more of the type (Bureau Nos. A-765 to A-783) under Contract 625. They were designated H-12B and powered by 330-hp Liberty engines.

The Curtiss boats were used at Pensacola for training and some patrols were carried out from Hampton Roads such as that of A-770 on 16 June 1918. With crew comprising Lt (jg) H.N. Slater, pilot; Lt H.W. Hoyt, observer; and Ens S.N. Hall, assistant pilot; and a mechanic (who did not get his name recorded), the flying boat left base searching for a dirigible that had been lost from Cape May. The machine flew to Cape May where it landed, took on fuel and oil and repaired a leaking radiator, then returned to base. The patrol was carried out successfully the only trouble being with the failure of the radiator. The Liberty motors gave no trouble, and the distance covered was approximately 385 miles. No record of an attack on a submarine by a US based H-12 has been found to date.

Killingholme, on the east coast of England, was one of the leading naval air stations as it was within striking distance of enemy submarines in the North Sea. It was also central to Allied convoys passing along the coast. Originally an oil supply depot, it was not an attractive town with its houses over-shadowed by the oil storage tanks. It was from here that the USN would make its first combat patrols in British Curtiss H-12 and Felixstowe F.2A boats. The US crews first flew with British crews until they were proficient in the operations carried out from Killingholme. The base was officially handed over to the US on 20 July 1918.

30 May 1918, saw Curtiss H-12, British serial N4336, make the first all American patrol from Killingholme under the command of Lt C.T. Hull, USN, with Ens A.W. Hawkins as second pilot. They were to meet and escort the USS Jason into the Humber River. Lt Comdr Whiting and Lt Leighton together with personnel and tons of material and supplies were on board. The Jason was sighted about 40 miles off Filey and accompanied into harbour.

On the night of 9-10 July 1918, N4336, with crew comprising Ens John Jay Schieffelin; Ens John Fanz Staub; E2c(r) Phillip E. Rollhause (W/T); LMM B. Howard M. Ernstein (engineer), was flying ahead of a slow convoy southward bound for London, when a dark streak of oil was spotted on the surface of the water, pointing in the direction of the convoy. Schieffelin thought that it might be from a sunken ship, however Staub indicated that they should attack. The boat dropped Very’s lights (flares) to indicate the position to British ships in the vicinity. After a careful run in, two bombs were dropped by the boat. They then descended to 200 feet to watch results.

The six British destroyers escorting the convoy approached in a wide V formation at full speed. “They were coal burners” recalled Schieffelin, “and black smoke gushed from their funnels, above orange flames. I then felt a distinct jar, and directly in front of us rose a wall of white water that looked as solid as a cliff. Putting our flying boat into a vertical bank and executing a “split-S” turn kept us from running into this white wall, and we climbed back to our proper altitude of 1,000 feet.” The white wall was the result of the destroyers having simultaneously dropped their depth charges! The aircraft was lucky not to have been wrecked by the explosion!

The oil slick grew larger in size and bubbles appeared. A destroyer stayed at the site overnight and the next day a periscope was seen and fired upon. The submarine was later reported to have made it back to Germany.

N4336 was lost on 19 July while on submarine patrol. It left Killingholme at 3.45 am under the command of Ens Ashton William Hawkins. About 6.45 am on the return course the engineer reported failure of the petrol supply due to an air lock. Two wireless messages were sent before the fuel failed at 7 am. A safe alighting was made in a big seaway. Pigeons were released giving the estimated position of the aircraft. The crew were finally able to get the bilge pump to supply petrol and the engines were started and the boat taxied for some three hours. By noon the sea had moderated about 50% so an attempt was made to take off. The boat attained a level attitude and was being pounded the whole time from one wave to the next and flying speed had just been gained when the aircraft broke in two, three feet forward of the step.

The boat was wrecked instantly, the tail sticking straight up. In the next moments the whole wreckage was covered in floating petrol and caught fire. The fire burned down in about an hour leaving one wing float and the central section of the hull just above water. The empty petrol tanks under this section held up the engines and what was left of the wreckage. The four crew clung to the wreckage.

A Sopwith Schneider had seen the wreck just as the fire had broken out as the pilot was seen waving to the survivors. A Short seaplane was seen flying about four or five miles away but did not see the survivors. A Schneider floatplane reappeared and dropped a life belt before flying off to try and inform the Short as to the location of the wreck without success. The Schneider then circled until it managed to bring a trawler to the rescue of the survivors. The time was about 3 pm. The first trawler picked up the crew and the second got lines on the engines. Both returned to Spurn. The crew were returned to the station by motor launch at about 2.30 am on the 20th. In the week ending 5 September, N4336 was finally officially deleted.

Schieffelin played a part in a dramatic sequence of events on the evening of 18 July. Jay and his co-pilot and navigator, Lt (jg) Roger Cutler, were ordered to report to the station CO, Commander Whiting. It appeared that a submarine had been attacking a convoy using its deck gun. Whiting estimated where the submarine would be expected to be the next morning to recharge its batteries. His orders were to “Search that area at dawn”.

With full crew, comprising E3c(r) John E. Taggert (W/T) and LMM B. Howard M. Ernstein (engineer), the pair left in their flying boat the next morning to the area determined by Whiting. While flying over the cliffs on the north side of Flamborough Head at about 400 feet, the air was very bumpy and the flying boat bounced so sharply that the

360-lb bomb suspended under our starboard wing caused the metal bar under which it was hung to bend enough to release the bomb from the two fork-shaped steel half-loops that held it steady. The bomb was teetering from side to side, and the small propeller (which armed the bomb after release) dropped away, so the bomb was fused and ready to be detonated by a jerk of any kind. I signalled to Roger to release the bomb. It exploded in very shallow water, and the concussion gave us another sharp jolt.

During these adventures the wireless aerial had carried away and they now had no way to communicate with the station.