A.Jackson De Havilland Aircraft since 1909 (Putnam)

Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.1

Like the S.E.1 before it, the construction of Geoffrey de Havilland and F. M. Green's next design, the two seat tractor B.E. 1 biplane, was disguised as repairs to an existing aeroplane. In this case it masqueraded as a Voisin biplane which had been presented to the War Office by the Duke of Westminster but only its 60 h.p. Wolseley water-cooled engine lived on in the new aircraft.

The B.E.1 was orthodox to modern eyes with slightly greater span to the upper wing but there was no fixed fin and lateral control was by wing warping. It was pushed out for first engine runs at Farnborough on December 4,1911 and first flew in the experienced hands of de Havilland on December 27. The first passenger was F. T. Hearle on January 3, 1912 but the rest of the month was spent in solving rigging problems. It eventually flew well, once at night, and carried a large number of passengers but before long the cumbersome Wolseley engine installation, with its drag-producing radiator between the front centre section struts, was scrapped in favour of an air-cooled 60 h.p. Renault. This engine was at first completely uncowled but the nose was later faired in to give protection to the occupants and the aircraft was so much quieter in the air than rotary engined machines that it was known locally as 'the silent aeroplane".

The B.E. 1, progenitor of the mass produced B.E.2s of several marks used during the First World War, had a comparatively long career and was equipped with early radio apparatus by Capt. H. P. T. Lefroy, R.E. With Geoffrey de Havilland as pilot he then used it for pioneer wireless controlled artillery shoots on Salisbury Plain. On March 11, 1912 it was handed over to Capt. J. C. Burke, C O . of the Air Battalion, accepted as airworthy next day, and later taken on charge by No. 2 Squadron, R.F.C. with serial number 201. In the hands of Capt. Burke and other pilots it took part in a number of experimental flights at Farnborough during 1913 and 1914 and eventually crashed there in January 1915.

SPECIFICATION AND DATA

Construction: By the Royal Aircraft Factory, Farnborough, Hants.

Power Plants:

One 60 h.p. Wolseley

One 60 h.p. Renault

Dimensions: Span 38 ft. 7 1/2 in. Length 29 ft. 6 1/2 in.

Performance: Maximum speed 59 m.p.h. Climb t o 600 ft. 3 min. 52 sec.

P.Hare Royal Aircraft Factory (Putnam)

B.E.1

The third machine in the Factory's initial research series, each of which was of a distinct and separate type, was a tractor biplane. It was named the Bleriot Experimental Number 1, or B.E.1. As with other contemporary Farnborough designs, it was ostensibly a reconstruction of another aeroplane, in this case a Voisin which had originally been presented to the War Office by the Duke of Westminster and which, following a crash, had been delivered to the Factory for repair in June 1911. The War Office granted permission for the alterations and additions which O'Gorman had suggested on 12 August 1911, but it is probable that design work, most of which was carried out by Geoffrey de Havilland, was already well advanced by that date.

Only the Voisin's engine, a water-cooled Wolseley V-8 developing a nominal 60hp, its radiator, and possibly a few metal fittings were actually used in the construction of the new machine, which was a two-bay biplane. Its upper wing was of slightly greater span than the lower, the wings originally being rigged with neither stagger nor dihedral. The large, low-aspect-ratio tailplane was of true aerofoil section, contributing to the overall lift, but was set at a smaller angle of incidence than the mainplanes to provide longitudinal stability. It was fastened directly to the upper longerons. The ear-shaped rudder hung from an unbraced sternpost, and there was no fin. Lateral control was by wing warping, the control column being of generous height to give the pilot good leverage and thereby reduce control forces to a level designed to eliminate fatigue.

The fuselage had decking behind the rear seat only, none being provided behind the engine or between the tandem cockpits. The passenger was placed in the forward seat, very close to the centre of gravity, so that no trim changes would occur when the machine was flown with two aboard. The radiator was mounted on the forward centre-section struts, where it benefited from the full force of the slipstream to achieve the necessary cooling with the minimum possible weight of water. The comparative quietness of the water-cooled engine, which was enhanced by the inclusion of silencers in its long exhaust pipes, led to the B.E.1 being dubbed the 'Silent Army Aeroplane'. The undercarriage incorporated long ash skids, intended to prevent the propeller tips touching the ground when the tail was raised, and the tailskid was fully swivelling, allowing a remarkably small turning circle on the ground.

Although photographs taken inside the workshop (known today as the Q27 building) in October 1911 show the aeroplane apparently complete, it did not make its first flight until 3.30pm on 4 December, when de Havilland took it up for a brief circuit, for which he was rewarded with two shillings and sixpence (12 1/2p) in flying pay. He reported that he was satisfied with the aeroplane, but less than happy with throttle control provided by the Wolseley's carburettor, and recommended the substitution of a Claudel unit. This may have been a more complex modification than de Havilland had imagined, because the machine did not fly again until 27 December, when, with the new carburettor installed, he made six short flights, several of them with a passenger. The maximum speed was found to be 55mph, although the engine was not achieving the 1,200rpm stated to be its maximum output (it never did so, despite continual attention).

De Havilland considered that the elevator operating mechanism was too coarsely geared for ease of control, tending to over-correct, and asked for it to be geared down, but otherwise he thought the aeroplane's stability to be good. He also expressed the opinion that too much weight was carried by the tailskid, lengthening the take-off run and, as a consequence, the wheels were repositioned twelve inches to the rear before the aircraft made its next flights, on the first day of the new year, when Mervyn O'Gorman occupied the front seat for two short flights.

By 7 January 1912 the top wing had been re-rigged with three inches of backstagger, presumably to move the centre of pressure slightly to the rear, and a scoop had been fitted in the front of the carburettor's air intake, a measure which increased engine speed by approximately 100rpm to about 1,100rpm.

On 10 January one degree of dihedral was given to each wing panel (an included angle of 178°), and two days later the aeroplane was tested with a Zenith carburettor, which was found to be much less flexible than its predecessor. De Havilland ran out of petrol during the tests, but accomplished the forced landing without mishap. Next day the Claudel was refitted and the B.E.1 was timed at 59mph over a measured three-quartermile course, with both seats occupied.

On 20 January, in a final attempt to improve engine performance, the propeller tips were cut down, producing an engine speed of 1,150rpm. This was the best ever achieved, although it was still just short of the maker's stated figure.

Throughout the remainder of January de Havilland flew the B.E.1 on numerous occasions, carrying many passengers, and he appears to have been completely satisfied with it. He did not suggest any further changes, and flew it in winds of up to 25mph before turning his attention to its twin sister, the B.E.2, which was completed by 1 February 1912.

On 11 March the B.E.1 was formally handed over to Capt C J Burke of the Air Battalion, Royal Engineers. Burke flew it for the first time three days later - the day on which the document which has come to be regarded as the first Certificate of Airworthiness was issued, certifying that the B.E.1 had been fully tested by the Factory.

The machine was given the serial B7, and the following month it became the property of No 2 (Aeroplane) Squadron of the newly formed Royal Flying Corps. In August its serial was changed to 201, an identity it retained throughout the remainder of its long career.

A heavy landing on 31 March 1912 resulted in the B.E.1 being returned to the Factory to be fitted with a new undercarriage. It was also fitted with a compass and an aneroid altimeter. On Thursday 11 April it suffered engine failure while being test flown by Mr Perry, and a wingtip was damaged in the ensuing forced landing. This was soon repaired, and the aeroplane was test flown by de Havilland at 6.00pm the following day. Following some alterations to the elevator cables, it was again test flown on 15 April before being returned to the RFC.

A further engine failure, on 28 May, led to its again being returned to the Factory. As its Wolseley engine was considered to be beyond economic repair, it was replaced by a Renault similar to that in the B.E.2. This engine, being air-cooled, allowed the removal of the radiator from the centre-section struts, with consequent improvements in performance and in the crew's forward view.

Following a test flight by de Havilland on 22 June, 201 was handed back to the Flying Corps, seeing service with No 4 and, later, No 5 Squadron. By the end of 1913 it had amassed a total of 172 flying hours. It had made several visits to the Factory for minor repairs, and had acquired fuselage decking ahead of, and between, the cockpits, making it virtually identical to contemporary B.E.2s. This similarity was further enhanced when its tailplane was replaced by one of slightly reduced area which had become the standard B.E.2 fitting at that time.

At the outbreak of war the B.E.1 was not sent to France, as were most of the RFC's effective aircraft, but remained with a training unit in England. Following a crash in January 1915 it was returned to Farnborough once more for repair, and was reported as still being there the following May. It is recorded as having been at the Central Flying School as late as July 1916, although by that date it had again been rebuilt and had acquired a B.E.2b-type fuselage.

The eventual fate of the B.E.1 is unknown. It merely fades from official records into an obscurity wholly undeserved by the 'revered grandfather of a whole brood of Factory aeroplanes'.

Powerplant: 60hp Wolseley V-8 (later 60hp Renault)

Dimensions:

span 38ft 7 1/2in (upper); 34ft 11 1/2in (lower);

chord 5ft 6in;

gap 6ft 0in

wing area: 374 sq ft

length 29ft 6 1/2in

height 10ft 2in

Performance: (Wolseley)

max speed 59mph (at sea level)

min speed 42mph

climb 155ft/min (to 600ft).

M.Goodall, A.Tagg British Aircraft before the Great War (Schiffer)

Deleted by request of (c)Schiffer Publishing

ROYAL AIRCRAFT FACTORY (RAF) Farnborough, Hampshire)

This military establishment began life in 1904-1905 on the Farnborough site, after the transfer of the Balloon Factory and School of Ballooning. The early work carried out included the building and flying of airships and kites, which developed into gliders and, from 1906, into powered flying machines. The earliest machines made at Farnborough were those for which Cody and Dunne were primarily responsible, but their work came to an end in March 1909, when all heavier-than-air work was stopped as an economy measure.

The Factory was reorganized as a civilian establishment from October 1909, with authority to carry out experimental work and to repair and maintain the aircraft operated by the Balloon School. It was necessary to acquire aircraft to carry out experimental work, among the first being the machine constructed by Geoffrey de Havilland, who was himself engaged at the same time as an engineer and pilot. The Factory was retitled HM Aircraft Factory in April 1910, and again in April 1912, when it became officially the Royal Aircraft Factory.

The building of a few aircraft for experimental work soon developed into quantity manufacture of a variety of aircraft types and engines. This competition caused considerable disquiet in the aircraft industry, where many firms were suffering from lack of orders. This contentious situation was finally resolved in 1917 by a major reorganization and a return to the original objective, of concentrating on research and experimental work for the benefit of the industry and the flying services. Contracts for various RAF designs were placed with industry from 1912 and made a major contribution to the growth of the industry for wartime production.

BE.1 was nominally the 'reconstruction' of a Voisin, although probably only the engine and little else was used in the new machine. Designed by Geoffrey de Havilland, he flew it for the first time on 4 December 1911.

BE.2 was virtually an identical aircraft, but with an air-cooled engine, perhaps from the Breguet, which was the basis for its 'reconstruction'. This machine flew for the first time on 1 February 1912 and again was flown by de Havilland.

BE.5 began life on 27 June 1912 with a water-cooled ENV engine from a Howard Wright, which was soon changed to an air-cooled Renault, which became the usual engine for other aircraft of a similar type.

BE.6 first flew on 6 September 1912 and may have been fitted briefly with an ENV before a Renault was installed. Later this machine was used for testing an oleo undercarriage with a single skid.

BE.1, 5 and 6 were similar machines to BE.2 and there were five more made at Farnborough in 1913, of the type loosely referred to as BE.2 type aircraft.

These machines were conventional two bay tractor biplanes, with the pilot in the rear seat of the single cockpit, although later a decking between the crew was fitted together with one behind the engine. The latter took the place of the vertical radiator, when the air-cooled engine was fitted. The exhaust pipes of the BE.2 were originally taken inside the fuselage instead of underneath. Differences in the length of the undercarriage skids, and the substitution of equal span wings, were other variations introduced over the period of the aircraft's life. Changes to the rigging of the wings were made during testing, but these were originally unstaggered and without dihedral and with warping control.

The BE.2 was fitted with twin main and tail floats as an amphibian and as a pure seaplane, in which latter form it apparently lifted off when tested on the Fleet Pond.

Power:

60hp Wolseley eight-cylinder water-cooled vee BE.l

60hp Renault eight-cylinder air-cooled vee BE.1 and 2 60hp ENV type F eight-cylinder water-cooled vee BE.5 and 6

70hp Renault eight-cylinder air-cooled vee BE.2, 6 and others

Data for BE.1. Some variations for other machines.

Span top 38ft 7in

Span bottom 34ft 11 l/2in

Chord 5ft 6in

Gap 6ft

Area 374 sq. ft

Area tailplane 52 sq. ft (Originally smaller on BE. 1)

Area elevators 25 sq. ft

Area rudder 12 sq. ft

Length 29ft 6 l/2in

Weight allup 1,700lb.

Height 10ft 2in

BE.1 with Wolesley

Speed range 42-59mph

Climb 155ft per min. to 600ft

BE.2 with 70hp Renault

Speed range 40-70mph

Climb 305ft per min. to 1,000ft

P.Lewis British Aircraft 1809-1914 (Putnam)

B.E.1

Shortly after it embarked upon the building of the S.E.1 from the Bleriot wreck early in 1911, the Army Aircraft Factory was given another opportunity in April to put its own design ideas into practical form. A Voisin pusher biplane, which had been presented to the War Office by the Duke of Westminster, arrived for repair. Still no funds were available to the Factory for the construction of new aircraft, so the Voisin also was seized upon as an excuse for reconstruction and an exercise in the B.E. (Bleriot Experimental) sphere. The result was a tractor biplane designated the B.E.1, the new machine utilizing the Voisin's 60 h.p. Wolseley engine, with which it was so quiet that it was called "The Silent Aeroplane". Under the supervision of Mervyn O'Gorman, the design of the B.E.1 was carried out by F. M. Green and Geoffrey de Havilland, who, between them, created the fore-runner of what was to be one of the most widely used aeroplanes of the 1914-18 War.

The fuselage consisted of a normal wooden box-girder complete with a rounded top-decking. No fin was fitted, the rudder being supported by a post. The view forward was obscured to some extent by the large rectangular radiator for the water-cooled Wolseley being mounted across the fuselage between the front centre-section struts. This was removed when it was rendered superfluous upon the installation in 1912 of a 60 h.p. Renault air-cooled engine, and other modifications were made following testing by Lt. de Havilland towards the end of 1911.

In January, 1912, the B.E.1, flown by de Havilland with Capt. H. P. T. Lefroy, R.E., as his passenger, conducted the first aerial wireless-controlled artillery observation which was held on Salisbury Plain and also took part, in experiments in wireless transmission. The B.E.1 is also notable as being the first British aeroplane to be granted a certificate of airworthiness, which it received on 14th March, 1912. The machine was handed over to the Air Battalion, R.E., as No. 201 during the same month, later flying with No. 2 Squadron, R. F.C., and at Netheravon. The B.E.1 was finally written off in January, 1915, after three years of flying on valuable experimental work.

SPECIFICATION

Description: Two-seat tractor biplane. Wooden structure, fabric covered.

Manufacturers: Army Aircraft Factory, Farnborough, Hants.

Power Plant: 60 h.p. Wolseley, 60 h.p. Renault.

Dimensions: Span, 38 ft. 7.5 ins. Length, 29 ft. 6.5 ins.

Performance: Maximum speed, 59 m.p.h. Climb, 3 mins. 52 secs, to 600 ft.

J.Bruce British Aeroplanes 1914-1918 (Putnam)

B.E.1

IN January, 1911, the first aeroplane designed throughout at the Balloon Factory was built by ostensibly reconstructing a crashed Bleriot monoplane: the result of the “reconstruction” was the S.E.1. It was only by recourse to such devices that the staff at Farnborough could construct aeroplanes of their own design, for the Factory had neither funds nor authority for the construction of aircraft.

A similar opportunity presented itself in April, 1911, when a Voisin pusher biplane with a 60 h.p. Wolseley engine was sent to Farnborough for repair: it had originally been presented to the War Office by the Duke of Westminster. The opportunity was taken to build a two-seat tractor biplane to the designs of F. M. Green and Geoffrey de Havilland.

The aircraft which emerged was the first to fall into the B.E. category and was consequently named B.E.1. At first the B.E.1 had the same Wolseley engine which had been installed in the Voisin. A rather sketchy cowling was fitted to the engine, and a large rectangular radiator was mounted between the forward centre-section struts. Soon, however, the Wolseley was replaced by a 60 h.p. Renault, and the last link with the Voisin machine was severed. These vee-eight engines were so quiet in comparison with the contemporary rotaries that the B.E.1 was known as the Silent Aeroplane.

The B.E.1 showed much advanced aerodynamic and structural thinking. The fuselage was a cross-braced wooden box-girder, fabric covered and with a rounded top-decking behind the long undivided cockpit. The ear-shaped rudder was mounted on the extended sternpost; there was no fin. The wings were of unequal span, and warping was used for lateral control. Fuel was carried in a gravity tank slung under the centre-section.

For three years the B.E.1 gave valuable and varied service, and participated in many experiments. In the course of these it suffered many mishaps and underwent many repairs. Its undercarriage bore the brunt of most of the crashes and had to be replaced frequently.

Apart from the testing of several experimental devices, the B.E.1 was the vehicle used for testing one of the earliest installations of wireless equipment in an aeroplane. Captain H. P. T. Lefroy, R.E., who in October, 1909, had been given charge of all experimental work in wireless telegraphy for the Army, devoted a good deal of time in the summer of 1911 to collaborating with R. Widdington in the design of a transmitter for use in aeroplanes. When completed, the transmitter was installed in the B.E.1 and tested in the air by Captain Lefroy; Geoffrey de Havilland flew the aircraft on this occasion.

In March, 1912, the B.E.1 was handed over to the Air Battalion and was assigned to Captain C. J. Burke. When the Royal Flying Corps was formed a few weeks later the machine was part of the equipment of No. 2 Squadron of which Major Burke became the Commanding Officer. The B.E.1 later received the official serial number 201, and was well-known to the officers of the infant R.F.C., officers whose names were to become part of the tradition of the new service: Brancker, Brooke-Popham, Longcroft, Sykes, Ashmore.

A distinction which can be claimed for the B.E.1 is that it was the first British aeroplane in respect of which a document roughly equivalent to a certificate of airworthiness was issued. This was dated March 14th, 1912.

In May, 1912, Captain Lefroy installed a generator in the B.E.1; it was driven from the engine crankshaft by a length of bicycle-chain running on sprockets.

The B.E.1 continued to be used at Farnborough and Netheravon until it was finally written off in a crash in January, 1915. Its epitaph was written several years later by Sir Walter Raleigh in Vol. I of The War in the Air: “The first machine of its type, it outlived generations of its successors, and before it yielded to fate had become the revered grandfather of the whole brood of Factory aeroplanes”.

SPECIFICATION

Manufacturers: The Royal Aircraft Factory, Farnborough, Hants.

Power: 60 h.p. Wolseley; 60 h.p. Renault.

Performance: Maximum speed: 59 m.p.h. Climb to 600 ft: 3 min 54 sec.

Service Use: Flown by the Air Battalion, R.E., and later by No. 2 Squadron, R.F.C., at Farnborough; later flown at Netheravon.

Serial Number: 201.

Jane's All The World Aircraft 1913

AIRCRAFT FACTORY. Royal Aircraft Factory, Farnborough, near Aldershot. For a long time this establishment had been engaged in dirigible construction and repairs. In 1911 it was decided to expand it in connection with the Royal Flying Corps. Its precise functions are somewhat uncertain. Its nominal main purpose is the repair, etc., of Service Aircraft. During 1912, however, it turned out several machines to a design of its own, known as the "B.E." This design was at one time regarded as confidential; but subsequently duplicates were built by private contractors, and the design illustrated below, published by the Advisory Committee for Aeronautics.

Length, 29-1/2 feet (9 m.)

Span.--36-3/4 feet (11.20 m.)

Area.--374 sq. feet (34-3/4 m^2.)

Weight.--

Motor.--75 h.p. Renault and others.

Speed.--

Журнал Flight

Flight, January 6, 1912.

NEW ARMY AIRCRAFT FACTORY AEROPLANE.

THE painstaking but very energetic research that progresses at the Army Aircraft Factory, under the superintendence of Mr. Mervyn O'Gorman, has resulted in another experimental aeroplane taking the air. The machine - from what we are allowed to see of it at the polite distance of a spectator among the casual public that frequents the Plain on the "off chance" - is a large biplane with an absolutely silent engine. It has been said that it is a remodeled version of the Duke of Westminster's old Voisin, but it seemed to us that there was more remodelling than anything else, and everything that one could see about the machine was of singular interest. In the control, the entire wing surfaces seem to be warped, which appears to give exceedingly powerful balancing action for the maintenance of lateral equilibrium. The detail construction also gives evidence of extreme care, and the application of the principle of streamline form together with the complete absence of visible rigging wires in the tail are both points worthy of comment. The engine is evidently a Wolseley, and has the propeller in front. A rough guess at the speed would place this figure at about 60 m.p.h. The gliding angle seems to be very fine too, as far as one can judge of these things by the eye. The propeller is of the four-bladed type; and, apart from the silence of the power-plant, another feature of especial importance is the fact that the engine can be started from on board. Mr. G. de Havilland has been acting as pilot with great success, and among the passengers has been the superintendent of the factory, whose object in this aeroplane construction work, it may be as well to emphasize once more, is research, not competitive manufacture. In fact, we believe the inclination of the officials is to give British constructors who are building military machines access to the information obtained by means of this research work.

Flight, January 20, 1912.

BRITISH NOTES OF THE WEEK.

Both British Army Aeroplanes Out.

ON Friday last the two aeroplanes built in the Army Aircraft Factory at Aldershot were flying, Mr. de Havilland being at the helm of the "silent" machine, while the other was piloted by Lieut. Fox. Both solo and passenger flights were made, one of the passengers being Capt. Lefroy, chief of the wireless telegraph station, who was doubtless obtaining information regarding the proposal to fit up the machines with wireless apparatus.

Flight, January 31, 1914.

THE ROYAL AIRCRAFT FACTORY AND THE INDUSTRY.

ELSEWHERE in this issue we deal editorially with the serious harm which is being done, in certain directions, by the ill-informed and wildly irresponsible criticism, in more or less general terms, directed against everything and everybody associated with the Royal Aircraft Factory. One great crime that looms more largely than anything else appears to be the alleged copying of the good features of machines turned out either here or abroad, the Avro, Nieuport, Blenot, and Breguet being specifically mentioned. Without wishing to detract in any way from the splendid work put into and done by these machines, and for reasons set out in our editorial comment, we have thought it high time that some protest should be raised against this extraordinary series of attacks which can only lead to one certain end, namely, the crippling, not to say annihilation, of the financial possibilities of the industry; and without any bias one way or the other, we have deemed it worth while to investigate in detail some of the so-called "facts" to see if they will stand up to the light of day. From various sources we have gleaned some interesting data, which speak for themselves, and we give the result of our enquiries below, which should be read in conjunction with, and, as it were, as an appendix to, our editorial comment already referred to.

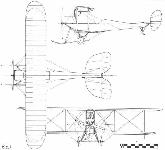

The first design of aeroplane built at the R.A.F. was known as the F., or the Farman type; the second, the S.E., was illustrated in FLIGHT for July 15th, 1911, and was so named because it belonged to the class originally introduced by Santos Dumont. It was characterised by the placing of the propeller behind the main planes, which were preceded by a more intensely loaded smaller plane. The third class of machine (see Fig. I) was commenced at the end of 1911, and was flown early in 1912, the letters B.E. (Bleriot Experimental) being assigned to it as a compliment to Mons. Bleriot, whose monoplanes had the propeller placed in front of the main supporting surfaces, and a tail. It is really difficult to see in what manner the suggestion of copying has arisen in the case of this machine, unless it be from the complimentary title, as in no part is any similarity observable. All these machines were biplanes, and were clearly indicated and illustrated by Mr. Mervyn O'Gorman, in a paper entitled, "Problems Relating to Aircraft," which was read before the Institution of Automobile Engineers on March 8th, 1911. As included in the B class, he instanced the Antoinette, R.E.P., Bleriot, Breguet, and the Avro. The three first-mentioned being monoplanes, the last a triplane, and the Breguet a biplane, the classification being governed by the position of the propeller relative to the main planes and the location of the smaller plane, which, in this class, is more lightly loaded than the main planes. The B.E. class were, therefore, clearly foreshadowed as early as March 8th, 1911, and must have received serious consideration long prior to that date, most probably in 1910, although the tail ultimately adopted was somewhat modified from that shown in the illustrations given in the paper. Furthermore, an examination of the drawings of the S.E. machine already referred to will elicit a very interesting fact, if the rudders are removed and the wings, tail skid and landing chassis are reversed, namely, that this machine is to all appearances similar in construction to the B.E. design.

At that time the only biplane in any way resembling this class of machine was the Breguet (see FLIGHT for December 17th, 1910, and July 22nd, 1911), but the construction of the wings, landing gear, fuselage, and tail planes were so radically different as to leave no opening for a valid suggestion that any part had been copied m the B.E. machines. There was but one row of struts between the main planes, which were formed by ribs hinged upon a steel spar; the steel landing gear was, and still is, of a special and peculiar type, and no rear skid was employed; the front portion of the fuselage was built up of pressed steel members, joining into a circular tube which continued to and supported the tail, which was mounted upon a universal-joint and had no fixed planes. Since that time, Mr. De Havilland designed a form of buffer gear for the landing chassis, which operated on the gun-recoil principle, but the only likeness to the Breguet construction was in its external appearance. The use of this particular form of gear has, however, since then been discontinued.

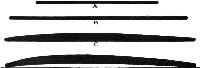

Early in 1911 Mr. A. V. Roe was principally engaged on his triplane, and had not then commenced to achieve those successes that have since been attained by his biplane. His triplane had a fuselage of triangular section, and only the part in the vicinity of the wings was covered in, whilst the tail planes were of flat section and formed by trapezium-shaped planes. The tail planes of the Avro biplane were also of flat section, but of rectangular form with corners removed (see FLIGHT for November 4th, 1911). The tail planes of the Nieuport monoplane (see FLIGHT for December 17th, 1910 and October 7th, 1911) were also of flat section (see Fig. 2). On the other hand, the tail plane (see Fig. 2c) for the B.E. machine, was designed by Mr. G. J. Watts, (then of the Royal Aircraft Factory and now of the staff of Messrs. Vickers), the design being most elaborate, and based upon curves of righting moments. It has since been superseded by the section shown in Fig. 2d, the reasons for so doing being given in the Advisory Committee's Report.

The differences in the shape of the wings and tail in plan is, however, of little consequence, and the particular manner of rounding off the planes is not significant compared with the enormous importance of a section. In the design of the early wings of the B.E. machines the results of Eiffel's experiments were consulted (see Advisory Committee's Reports for 1911-12) as is also done by the designers of many other machines, and in accordance with that writer's recommendations a section intermediate between Bleriot XII bis and another form was tried, although this particular section was abandoned later on the strength of model experiments carried out in an air channel at the National Physical Laboratory at the request of the Royal Aircraft Factory.

The construction of the supporting surfaces on the Breguet biplane, which are quite a special feature of this machine, have already been discussed; and as regards the Avro biplane there are differences in the plan form, internal construction, and the method of assembling, which are readily observable from a comparison between Figs. 1 and 4 and the scale drawing of B.E. 2a, given on page 1062 of FLIGHT for November 16, 1912, whilst the strut section and arrangement are dissimilar. The Nieuport monoplane also embodied an entirely different form of wing surface.

The fuselage of the 1911 Avro biplane was of triangular section, whereas that of the S.E. class had a rectangular section, and the B.E.'s were, and still are, of rectangular form with a rounded upper surface for a short distance behind the pilot's seat. Further, the open bodywork and section of the Bleriot cannot be regarded as in any way similar to the Army machines, which are canvas-covered. The body of the Nieuport also, although covered in, was dissimilar from the B.E. in regard to the shape of the nose and its proportions, the fuselage having exceptional depth at the front end.

In the landing gear similar differences occur, as references to the drawings and illustration already mentioned will show, the Avro having a chassis of the Farman type, supported on four wheels, on the triplane; and the arrangement seen in Fig. 4 on their biplane, the construction used on the Nieuport being illustrated in Fig. 3; whilst the special designs of chassis, employed on the Breguet and the Bleriot, are already too well known to need further demonstration as to their absolute dissimilarity. As regards the tail skid, this was, and still is, to a large extent, of a design peculiar to the B.E.'s, and was evolved for the purpose of rendering the machines manageable on the ground at low speeds, when machines controlled solely by the air rudder are out of hand; whilst it also enables a machine to be turned in a very short radius (see Advisory Committee's Report for 1911 and 1912).

Coming to more recent times, it will be found that the special form of wing surface construction, under-carriage, fuselage, and tail of the Breguet machines remain, and have undergone little fundamental change, except that the wings are now mounted rigidly upon the steel spar, ailerons are fitted, and the whole machine has been made more robust (see FLIGHT for February 22nd, June 14th and December 27th, 1913). On the Avro (see FLIGHT for March 30th and August 31st, 1912, and December 6th, 1913), the triangular-shaped fuselage has given place to one of rectangular section, which tapers to a knife edge at the rear, the upper surfaces being horizontal in straight flight; whilst ample depth of section has been given to the fore part, primarily in order to afford greater comfort for the pilot. The landing chassis has also been changed, for, instead of the double skids used on the earlier machines, a construction somewhat, though not exactly, similar to that used on the Nieuport (see FLIGHT or October 7th, 1911) is embodied, where a single skid supported on a spring axle, carries the machine on V-struts, the latest machine having shock absorbers fitted to these struts. On the latest model the main planes are staggered, the upper plane being slightly in front of the lower, a construction which was first employed, at all events in this country, on B.E. 3 (see Advisory Committee's Report, 1911 and 1912) as the result of research at the National Physical Laboratory, and because they permitted a larger field of vision. Ailerons were first fitted to the Avro hydroplane (see FLIGHT for June 14th, 1913), and have also been used on the machine subsequently developed.

On the Nieuport machines, minor alterations have been made, such as affect the shape and dimensions of the planes, fuselage, &c. - the body, for example, has been tapered to a vertical knife edge at the rear (see FLIGHT for March 22nd and April 19th, 1913) ; but the general design employed on the earlier machines is still continued.

With regard to the B.E. machines, many changes have been made in the course of the last three years, but these have been principally in regard to the wing section, and as such no suggestion of copying can be seriously entertained. Different methods of wing fixing, various forms of control mechanism, and other minor variations in design have been tested with the object of finding that which is the most effective for military purposes; but the essential features that have characterised the B.E.'s from their inception are in the main still retained on the latest types. Among the alterations which may be mentioned as having been made are the staggering of the planes previously referred to, the hinging of the rear spars of the main planes, and the equalising of the span of the tipper and lower wings for the purpose of interchangeability; whilst the tail area has also been varied, its construction, however, remaining practically the same as in the earlier machine.

In conclusion, we may observe that similarities in some respects must necessarily exist between one machine and another, as is clearly evident from an inspection of current types of aeroplanes, for in the endeavour to obtain the highest efficiency, surfaces are smoothed off so as to obtain a streamline form, and thus become more and more like one another in appearance, especially as the same authorities are consulted in their design, and the purposes for which the completed machines are intended to be used, are very similar. But these points of resemblance are common to other machines than those referred to, and we therefore say it is evident that the individual characteristics of the original B.E. class of machine are still retained, and have not been modified by the introduction of fresh features copied from other machines.