Книги

Putnam

F.Mason

The British Fighter since 1912

176

F.Mason - The British Fighter since 1912 /Putnam/

A.D. Sparrow

Following the creation of the Naval Wing in 1912, the Admiralty established an Air Department whose purpose was to deal with all matters relating to naval aviation. The popular but eccentric Harris Booth, late of the National Physical Laboratory, was given charge of all technical considerations and, in due course, headed an aircraft design section whose products were to be contracted out for manufacture by private companies.

One of Booth’s first designs was the A.D. Sparrow, or Scout, of 1915, an extraordinary-looking pusher biplane intended for anti-Zeppelin fighting, and to be armed with a two-pounder Davis recoilless, quick-firing gun; and it was the installation of this weapon that dictated the design of the nacelle. The A.D. Sparrow was a single-bay, heavily-staggered biplane, powered by an 80hp Gnome rotary engine; the tail booms were rigged parallel in plan and elevation and carried an enormous 21ft-span tailplane and elevator with widely-spaced twin fins and rudders. In order to provide ground clearance for the propeller, the nacelle was attached to the upper wings and, with large wing gap, the lower wing was a continuous structure placed five feet below the nacelle. A twin wheel-and-skid undercarriage of exceptionally narrow track was fitted, stability on the ground being achieved by the tail skids at the base of the tail fins.

Almost certainly owing to the esteem in which Booth was held, four examples of the Sparrow were ordered - two from the Blackburn Aeroplane & Motor Co of Leeds, and two from Hewlett & Blondeau Ltd. It is said that all four were built and delivered to the RNAS at Chingford, Essex, but, being somewhat overweight and underpowered, were found to be difficult to control in the air and were soon abandoned. As far as is known, the Davis gun was never fitted.

Type: Single pusher engine, single-seat, single-bay biplane scout.

Manufacturers: The Blackburn Aeroplane & Motor Co Ltd, Leeds; Hewlett & Blondeau Ltd, Leagrave, Bedfordshire.

Powerplant: One 80hp Gnome rotary engine driving two-blade propeller.

Structure: Predominantly wood with fabric covering; twin wheel-and-skid undercarriage.

Dimensions (Approx only,): Span, 33ft 5in; length, 22ft 9in; height, 10ft 3in.

Weights and Performance: Not known.

Armament: Intended to be armed with one 2-pdr Davis recoilless, quick-firing gun in the nose of the nacelle.

Prototypes: Four, Nos 1452-1453 (Hewletts), and 1536-1537 (Blackburn). No production.

Following the creation of the Naval Wing in 1912, the Admiralty established an Air Department whose purpose was to deal with all matters relating to naval aviation. The popular but eccentric Harris Booth, late of the National Physical Laboratory, was given charge of all technical considerations and, in due course, headed an aircraft design section whose products were to be contracted out for manufacture by private companies.

One of Booth’s first designs was the A.D. Sparrow, or Scout, of 1915, an extraordinary-looking pusher biplane intended for anti-Zeppelin fighting, and to be armed with a two-pounder Davis recoilless, quick-firing gun; and it was the installation of this weapon that dictated the design of the nacelle. The A.D. Sparrow was a single-bay, heavily-staggered biplane, powered by an 80hp Gnome rotary engine; the tail booms were rigged parallel in plan and elevation and carried an enormous 21ft-span tailplane and elevator with widely-spaced twin fins and rudders. In order to provide ground clearance for the propeller, the nacelle was attached to the upper wings and, with large wing gap, the lower wing was a continuous structure placed five feet below the nacelle. A twin wheel-and-skid undercarriage of exceptionally narrow track was fitted, stability on the ground being achieved by the tail skids at the base of the tail fins.

Almost certainly owing to the esteem in which Booth was held, four examples of the Sparrow were ordered - two from the Blackburn Aeroplane & Motor Co of Leeds, and two from Hewlett & Blondeau Ltd. It is said that all four were built and delivered to the RNAS at Chingford, Essex, but, being somewhat overweight and underpowered, were found to be difficult to control in the air and were soon abandoned. As far as is known, the Davis gun was never fitted.

Type: Single pusher engine, single-seat, single-bay biplane scout.

Manufacturers: The Blackburn Aeroplane & Motor Co Ltd, Leeds; Hewlett & Blondeau Ltd, Leagrave, Bedfordshire.

Powerplant: One 80hp Gnome rotary engine driving two-blade propeller.

Structure: Predominantly wood with fabric covering; twin wheel-and-skid undercarriage.

Dimensions (Approx only,): Span, 33ft 5in; length, 22ft 9in; height, 10ft 3in.

Weights and Performance: Not known.

Armament: Intended to be armed with one 2-pdr Davis recoilless, quick-firing gun in the nose of the nacelle.

Prototypes: Four, Nos 1452-1453 (Hewletts), and 1536-1537 (Blackburn). No production.

Alcock A.I

Flight-Lieut John W Alcock (later to be knighted for his epic first non-stop flight across the Atlantic) was serving with No 2 Wing, RNAS, at Mudros in the Aegean during the summer of 1917 when he built a small biplane scout, variously referred to as the Alcock A.I and ‘Sopwith Mouse’. Many of the design calculations were performed by Cdr Constantine of the Greek Navy at Mudros.

Alcock’s fighter employed numerous components from crashed aircraft, including the fuselage, undercarriage and most of the lower wing from a Sopwith Triplane, and the upper wing of a Pup, into which was inserted a new centre section with cutout. A 100hp Gnome monosoupape engine drove a two-blade propeller, and the two-bay wings were rigged without effective stagger, the interplane struts converging downwards owing to the considerable difference in the two wing chords. It is not known whether the vertical tail surfaces (dorsal and ventral fins, and unbalanced rudder) were newly constructed or salvaged components, but the tailplane and elevator bear a similarity to those of the Pup.

The fuselage was located roughly in the centre of the wing gap, clear of the lower wing, with the new centre section of the upper wing level with the pilot’s horizontal line of sight. Twin synchronized Vickers guns were mounted forward of the cockpit.

Contrary to the account in the official history (The War in the Air, Vol. 5), Alcock did not fly his aircraft, being shot down in a Handley Page O/400 and captured by the Turks on 30 September 1917, before its completion. Nevertheless it was subsequently flown, probably on 15 October by Wing Capt Francis Rowland Scarlett (later Air Vice-Marshal, cb, dso, raf), and was later destroyed when it was struck on the ground by a D.H.4 at Mudros.

Type: Single-engine, single-seat, two-bay biplane fighting scout.

Manufacturer: Flight-Lieut J W Alcock, RNAS, and personnel of No 2 Wing, RNAS, Mudros.

Powerplant: One 100hp Gnome monosoupape engine driving two-blade propeller; later fitted with 110hp Clerget engine.

Armament: Two synchronized 0.303in Vickers machine guns.

The Author is indebted to Mr J M Bruce for permission to reproduce the above material, which represents the result of research among former members of No 2 Wing, RNAS. The official history also incorrectly states that the Alcock A.I was powered by a captured Benz engine.

Flight-Lieut John W Alcock (later to be knighted for his epic first non-stop flight across the Atlantic) was serving with No 2 Wing, RNAS, at Mudros in the Aegean during the summer of 1917 when he built a small biplane scout, variously referred to as the Alcock A.I and ‘Sopwith Mouse’. Many of the design calculations were performed by Cdr Constantine of the Greek Navy at Mudros.

Alcock’s fighter employed numerous components from crashed aircraft, including the fuselage, undercarriage and most of the lower wing from a Sopwith Triplane, and the upper wing of a Pup, into which was inserted a new centre section with cutout. A 100hp Gnome monosoupape engine drove a two-blade propeller, and the two-bay wings were rigged without effective stagger, the interplane struts converging downwards owing to the considerable difference in the two wing chords. It is not known whether the vertical tail surfaces (dorsal and ventral fins, and unbalanced rudder) were newly constructed or salvaged components, but the tailplane and elevator bear a similarity to those of the Pup.

The fuselage was located roughly in the centre of the wing gap, clear of the lower wing, with the new centre section of the upper wing level with the pilot’s horizontal line of sight. Twin synchronized Vickers guns were mounted forward of the cockpit.

Contrary to the account in the official history (The War in the Air, Vol. 5), Alcock did not fly his aircraft, being shot down in a Handley Page O/400 and captured by the Turks on 30 September 1917, before its completion. Nevertheless it was subsequently flown, probably on 15 October by Wing Capt Francis Rowland Scarlett (later Air Vice-Marshal, cb, dso, raf), and was later destroyed when it was struck on the ground by a D.H.4 at Mudros.

Type: Single-engine, single-seat, two-bay biplane fighting scout.

Manufacturer: Flight-Lieut J W Alcock, RNAS, and personnel of No 2 Wing, RNAS, Mudros.

Powerplant: One 100hp Gnome monosoupape engine driving two-blade propeller; later fitted with 110hp Clerget engine.

Armament: Two synchronized 0.303in Vickers machine guns.

The Author is indebted to Mr J M Bruce for permission to reproduce the above material, which represents the result of research among former members of No 2 Wing, RNAS. The official history also incorrectly states that the Alcock A.I was powered by a captured Benz engine.

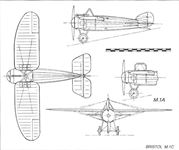

Armstrong Whitworth F.K.1

The Aeroplane Department of the heavy engineering enterprise, Sir W G Armstrong, Whitworth & Co Ltd, came into being at the beginning of 1914, its first works manager and aircraft designer being the Dutch-born Frederick Koolhoven. A qualified pilot himself, who had already acquired design experience working on Deperdussin monoplanes, Koolhoven’s first aircraft for Armstrong Whitworth was a small single-bay unstaggered biplane designated the F.K.1.

Of exceptional simplicity in the interests of possible future production orders as a military scout, the F.K.1 was intended to be powered by an 80hp Gnome rotary; however, as this engine was not immediately available, recourse was made to the 50hp version, with the result that the aircraft was substantially underpowered. Although the tail unit included a fixed fin forward of the rudder hinge-post, there was initially no tailplane, a balanced elevator being fitted.

The F.K.1 was first flown by Koolhoven himself in September 1914. He was clearly dissatisfied with the longitudinal and lateral control, and the ailerons were replaced by much enlarged surfaces with inverse taper, and a fixed tailplane was added.

Although no reliable design and performance figures appear to have survived, the aircraft was obviously inferior to such contemporary aircraft as the Sopwith Tabloid and Bristol Scout, and its development was not pursued.

Type: Single-engine, single-seat, single-bay tractor biplane.

Manufacturer: Sir W G Armstrong, Whitworth & Co Ltd, Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

Powerplant: One 50hp Gnome rotary engine driving two-blade propeller.

Structure: Steel and wood composite construction; square-section box-girder fuselage, fabric covered. Twin-wheel, single-skid undercarriage.

Performance: Max speed, 75 mph at sea level; landing speed, 30 mph.

Armament: None.

Prototype: One (first flown by Frederick Koolhoven in September 1914). No production.

The Aeroplane Department of the heavy engineering enterprise, Sir W G Armstrong, Whitworth & Co Ltd, came into being at the beginning of 1914, its first works manager and aircraft designer being the Dutch-born Frederick Koolhoven. A qualified pilot himself, who had already acquired design experience working on Deperdussin monoplanes, Koolhoven’s first aircraft for Armstrong Whitworth was a small single-bay unstaggered biplane designated the F.K.1.

Of exceptional simplicity in the interests of possible future production orders as a military scout, the F.K.1 was intended to be powered by an 80hp Gnome rotary; however, as this engine was not immediately available, recourse was made to the 50hp version, with the result that the aircraft was substantially underpowered. Although the tail unit included a fixed fin forward of the rudder hinge-post, there was initially no tailplane, a balanced elevator being fitted.

The F.K.1 was first flown by Koolhoven himself in September 1914. He was clearly dissatisfied with the longitudinal and lateral control, and the ailerons were replaced by much enlarged surfaces with inverse taper, and a fixed tailplane was added.

Although no reliable design and performance figures appear to have survived, the aircraft was obviously inferior to such contemporary aircraft as the Sopwith Tabloid and Bristol Scout, and its development was not pursued.

Type: Single-engine, single-seat, single-bay tractor biplane.

Manufacturer: Sir W G Armstrong, Whitworth & Co Ltd, Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

Powerplant: One 50hp Gnome rotary engine driving two-blade propeller.

Structure: Steel and wood composite construction; square-section box-girder fuselage, fabric covered. Twin-wheel, single-skid undercarriage.

Performance: Max speed, 75 mph at sea level; landing speed, 30 mph.

Armament: None.

Prototype: One (first flown by Frederick Koolhoven in September 1914). No production.

Armstrong Whitworth F.K.12

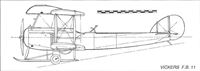

If the products of Sopwith and Vickers, in the search for an escort fighter, had appeared quaint, that of Frederick Koolhoven at Armstrong, Whitworth was nothing less than incongruous. Both the L.R.T.Tr and the F.B.11 had employed single nacelles in which to accommodate additional gunners, both selecting the top wing as a logical position from which to gain the widest field of fire. Koolhoven decided on two nacelles, and placed them at the front of the central wing of a large single-bay triplane, powered by a single 250hp Rolls-Royce Mark I.

When the F.K.12 first appeared towards the end of 1916, the central wing - with by far the greater span - was located well forward on the fuselage, so that the engine only just extended beyond the leading edge; the top and bottom wings were much smaller structures, carried on struts above and below the fuselage and rigged without stagger. The gunners’ nacelles were long structures mounted above the central wing, extending forward of the propeller. The undercarriage comprised a pair of main-wheels mounted on a single strut extending from beneath the engine and attached to the leading edge of the lower wing, and a small, sprung auxiliary wheel under each lower wingtip. A rear skid was carried on long pyramidal struts extending downwards from the fuselage immediately to the rear of the lower wing.

The first configuration was not considered successful and was followed by a no less extraordinary aircraft which was probably newly built, rather than an adaptation of the first. This retained the same arrangement of ‘short-long-short’ wings as previously but with a much deeper fuselage occupying the entire gap between the two lower wings. These two-bay wings were set further aft on the fuselage so that the engine extended further forward. The twin gunners’ nacelles, now mounted beneath the central wing, were much shorter so the gunners’s cockpits were behind and outboard of the propeller. (They were incidentally no more than two feet from the open ends of the big Rolls-Royce engine’s exhaust manifolds.)

The undercarriage now comprised two pairs of landing wheels mounted on heavy vertical members attached to the sides of the fuselage and were thus of very narrow track; a conventional tailskid was attached under the rear fuselage, and the wingtip balancing wheels were discarded in favour of hooped skids.The aircraft, No 7838, was flown by Lieut-Cdr Peter Legh, but no reliable records of the flight trials of the aircraft have been traced. A total of four F.K.12 prototypes was ordered by the War Office, but it is thought likely that the two aircraft described here were the only examples completed.

Type: Single-engine, three-seat, two-bay triplane escort fighter.

Manufacturer: Sir W G Armstrong, Whitworth & Co Ltd, Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

Powerplant: One 250hp Rolls-Royce Mk I twelve-cylinder liquid-cooled in-line engine driving four-blade propeller.

Armament: Two 0.303in Lewis machine guns on rocking-post mountings in nacelles carried on central wing.

Prototypes: Four ordered, Nos 7838-7841. It is not known how many were completed.

If the products of Sopwith and Vickers, in the search for an escort fighter, had appeared quaint, that of Frederick Koolhoven at Armstrong, Whitworth was nothing less than incongruous. Both the L.R.T.Tr and the F.B.11 had employed single nacelles in which to accommodate additional gunners, both selecting the top wing as a logical position from which to gain the widest field of fire. Koolhoven decided on two nacelles, and placed them at the front of the central wing of a large single-bay triplane, powered by a single 250hp Rolls-Royce Mark I.

When the F.K.12 first appeared towards the end of 1916, the central wing - with by far the greater span - was located well forward on the fuselage, so that the engine only just extended beyond the leading edge; the top and bottom wings were much smaller structures, carried on struts above and below the fuselage and rigged without stagger. The gunners’ nacelles were long structures mounted above the central wing, extending forward of the propeller. The undercarriage comprised a pair of main-wheels mounted on a single strut extending from beneath the engine and attached to the leading edge of the lower wing, and a small, sprung auxiliary wheel under each lower wingtip. A rear skid was carried on long pyramidal struts extending downwards from the fuselage immediately to the rear of the lower wing.

The first configuration was not considered successful and was followed by a no less extraordinary aircraft which was probably newly built, rather than an adaptation of the first. This retained the same arrangement of ‘short-long-short’ wings as previously but with a much deeper fuselage occupying the entire gap between the two lower wings. These two-bay wings were set further aft on the fuselage so that the engine extended further forward. The twin gunners’ nacelles, now mounted beneath the central wing, were much shorter so the gunners’s cockpits were behind and outboard of the propeller. (They were incidentally no more than two feet from the open ends of the big Rolls-Royce engine’s exhaust manifolds.)

The undercarriage now comprised two pairs of landing wheels mounted on heavy vertical members attached to the sides of the fuselage and were thus of very narrow track; a conventional tailskid was attached under the rear fuselage, and the wingtip balancing wheels were discarded in favour of hooped skids.The aircraft, No 7838, was flown by Lieut-Cdr Peter Legh, but no reliable records of the flight trials of the aircraft have been traced. A total of four F.K.12 prototypes was ordered by the War Office, but it is thought likely that the two aircraft described here were the only examples completed.

Type: Single-engine, three-seat, two-bay triplane escort fighter.

Manufacturer: Sir W G Armstrong, Whitworth & Co Ltd, Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

Powerplant: One 250hp Rolls-Royce Mk I twelve-cylinder liquid-cooled in-line engine driving four-blade propeller.

Armament: Two 0.303in Lewis machine guns on rocking-post mountings in nacelles carried on central wing.

Prototypes: Four ordered, Nos 7838-7841. It is not known how many were completed.

The second version of the Armstrong, Whitworth F.K.12 escort fighter, No 7838, with enlarged fuselage and underslung gunners’ nacelles.

The rebuilt triplane, probably the F.K.6, was designed as an escort fighter and Zeppelin destroyer.

The rebuilt triplane, probably the F.K.6, was designed as an escort fighter and Zeppelin destroyer.

Armstrong Whitworth F.K. 10

Possibly originally undertaken as a design exercise to investigate the potential of the quadruplane configuration, Frederick Koolhoven’s F.K.10 attracted the interest of the Services as a possible fighter. A prototype was built during the late summer of 1916, emerging as a lanky two-seater powered by a 110hp Clerget engine and featuring a slim, angular fuselage in which the pilot’s cockpit was located forward of the wings, and an observer’s cockpit aft of them. The wings, of only 3ft 7in chord, spanned 27ft 10in, and were rigged with a total stagger of 4ft 3in. The tail comprised a rather crude horn-balanced rudder with fixed fin below the fuselage, fixed tailplane and unbalanced elevator. The undercarriage consisted of single faired struts on each side, with the spreader bar heavily cable-braced between its extremities and the lower longerons. Single interplane and cabane I-struts were employed, and the second from top wing possessed no centre section so as to leave the crew’s field of view less obstructed. Ailerons were fitted on all wings. A single synchronized Vickers gun was provided for the pilot and was mounted on the aircraft’s centreline over the engine cowling, the observer’s cockpit being equipped with a mounting for a Lewis gun.

A total of three prototypes is believed to have been built by Armstrong Whitworth, after which the War Office ordered five production aircraft from Angus Sanderson of Newcastle, and the Admiralty ordered three from the Phoenix Dynamo company of Bradford, though it is not known whether all were built. Most were fitted with 130hp Clergets.

The production F.K.10s were rather more elegantly styled than the original prototype, with larger fuselage section and tidied-up tail surfaces. One of the RFC machines was flown by the Training Unit at Gosport, and the first RNAS aircraft, N511, underwent its Service trials at Boroughbridge in April 1917; another of the naval aircraft was completed as a bomber with racks for light bombs.

Type: Single-engine, two-seat, single-bay quadruplane fighter.

Manufacturers: Sir W G Armstrong, Whitworth & Co Ltd, Newcastle-upon-Tyne; The Phoenix Dynamo Manufacturing Co Ltd, Bradford; Angus Sanderson & Co, Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

Powerplant: One 110hp Clerget engine; also 130hp Clerget; 110hp Le Rhone.

Dimensions: Span, 27ft 10in; length, 22ft 3in; height, 11ft 6in; wing area, 390.4 sq ft.

Weights: (130hp Clerget). Tare, 1,236lb; all-up, 2,019lb.

Performance: (130hp Clerget). Max speed, approx 90 mph at sea level; climb to 10,000ft, 37 min 10 sec; service ceiling, 10,000ft; endurance, 2 1/2 hr.

Armament: One synchronized 0.303in Vickers machine gun on nose, and one 0.303in Lewis gun on real' cockpit mounting.

Prototypes: Believed three, A5212-A5214 (built by Armstrong, Whitworth).

Production: Total of eight ordered (B3996-B4000 for RFC, built by Angus Sanderson; N511, N512 and N514 built by Phoenix Dynamo).

Summary of Service: Single examples flown by the RFC at Gosport, and by the RNAS at Mansion, both probably in 1917.

Possibly originally undertaken as a design exercise to investigate the potential of the quadruplane configuration, Frederick Koolhoven’s F.K.10 attracted the interest of the Services as a possible fighter. A prototype was built during the late summer of 1916, emerging as a lanky two-seater powered by a 110hp Clerget engine and featuring a slim, angular fuselage in which the pilot’s cockpit was located forward of the wings, and an observer’s cockpit aft of them. The wings, of only 3ft 7in chord, spanned 27ft 10in, and were rigged with a total stagger of 4ft 3in. The tail comprised a rather crude horn-balanced rudder with fixed fin below the fuselage, fixed tailplane and unbalanced elevator. The undercarriage consisted of single faired struts on each side, with the spreader bar heavily cable-braced between its extremities and the lower longerons. Single interplane and cabane I-struts were employed, and the second from top wing possessed no centre section so as to leave the crew’s field of view less obstructed. Ailerons were fitted on all wings. A single synchronized Vickers gun was provided for the pilot and was mounted on the aircraft’s centreline over the engine cowling, the observer’s cockpit being equipped with a mounting for a Lewis gun.

A total of three prototypes is believed to have been built by Armstrong Whitworth, after which the War Office ordered five production aircraft from Angus Sanderson of Newcastle, and the Admiralty ordered three from the Phoenix Dynamo company of Bradford, though it is not known whether all were built. Most were fitted with 130hp Clergets.

The production F.K.10s were rather more elegantly styled than the original prototype, with larger fuselage section and tidied-up tail surfaces. One of the RFC machines was flown by the Training Unit at Gosport, and the first RNAS aircraft, N511, underwent its Service trials at Boroughbridge in April 1917; another of the naval aircraft was completed as a bomber with racks for light bombs.

Type: Single-engine, two-seat, single-bay quadruplane fighter.

Manufacturers: Sir W G Armstrong, Whitworth & Co Ltd, Newcastle-upon-Tyne; The Phoenix Dynamo Manufacturing Co Ltd, Bradford; Angus Sanderson & Co, Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

Powerplant: One 110hp Clerget engine; also 130hp Clerget; 110hp Le Rhone.

Dimensions: Span, 27ft 10in; length, 22ft 3in; height, 11ft 6in; wing area, 390.4 sq ft.

Weights: (130hp Clerget). Tare, 1,236lb; all-up, 2,019lb.

Performance: (130hp Clerget). Max speed, approx 90 mph at sea level; climb to 10,000ft, 37 min 10 sec; service ceiling, 10,000ft; endurance, 2 1/2 hr.

Armament: One synchronized 0.303in Vickers machine gun on nose, and one 0.303in Lewis gun on real' cockpit mounting.

Prototypes: Believed three, A5212-A5214 (built by Armstrong, Whitworth).

Production: Total of eight ordered (B3996-B4000 for RFC, built by Angus Sanderson; N511, N512 and N514 built by Phoenix Dynamo).

Summary of Service: Single examples flown by the RFC at Gosport, and by the RNAS at Mansion, both probably in 1917.

Armstrong Whitworth F.K.10, N511, built by Phoenix Dynamo Manufacturing Co. with 130 h.p. Clerget, horse-shoe cowling, modified coaming about pilot’s cockpit, and Scarff ring-mounting for observer’s gun.

Armstrong, Whitworth F.M.4 Armadillo

Variously described elsewhere as ‘pugnacious’ and ‘far from elegant’, the F.M.4 Armadillo was surely nothing short of ugly, and was possibly the brainchild of Frederick Koolhoven, who had left Armstrong, Whitworth to join the British Aerial Transport company following the failure of his F.K.10 and 12, his place being taken as chief designer by Fred Murphy.

Subject of Licence No 18, two prototypes (X19 and X20) of this small two-bay biplane were authorized, and X19

appeared in September 1918. Rigged with scarcely any stagger, the wings were of fairly broad chord, and the upper wing - without conventional centre section - was attached to the top shoulders of the square-section fuselage. This was in keeping with Koolhoven’s latest preoccupation, that of setting the upper wing level with the pilot’s eyes.

The fuselage was a plain wooden box girder with flat ply sheet covering the sides, but without any attempt to provide any rounded decking. The engine was a 230hp Bentley B.R.2 rotary with a cowling that completely enveloped the cylinders, and included a fairly small aperture for cooling air entry. A most incongruous feature was a humped fairing, curving up from the front of the cowling to the top line of the upper wing, inside which were mounted the aircraft’s twin Vickers guns.

The reasoning behind this wing layout was obviously to provide the pilot with an excellent field of view forward and above, but the bulk of the nose and the lower wings severely restricted the pilot’s view of the ground, especially when landing, despite cutouts in the wings, and the aircraft was severely criticised on this account - not to mention many others.

It is difficult to understand what lay behind the production of this machine so late in the War for, with over one hundred horsepower more that the Le Rhone Camel of the previous year available, the speed performance of the Armadillo showed scarcely any advance. It is not known whether the second example was completed.

Type: Single-engine, single-seat, two-bay biplane fighter.

Manufacturer: Sir W G Armstrong, Whitworth & Co Ltd, Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

Powerplant: One 230hp Bentley B.R.2 rotary engine.

Dimensions: Span, 27ft 9in; length, 18ft 10in; height, 7ft 10in; wing area, 232 sq ft.

Weights: Tare, 1,250lb; all-up, 1,860lb.

Performance: Max speed, 125 mph at sea level; climb to 10,000ft, 6 min 30 sec; ceiling, 24,000ft.

Armament: Two synchronized 0.303in Vickers machine guns under fairing over the nose.

Prototypes: Two; X19 and X20 authorised under Licence No 18. X19 flown in September 1918; X20 may not have been completed. No production.

Variously described elsewhere as ‘pugnacious’ and ‘far from elegant’, the F.M.4 Armadillo was surely nothing short of ugly, and was possibly the brainchild of Frederick Koolhoven, who had left Armstrong, Whitworth to join the British Aerial Transport company following the failure of his F.K.10 and 12, his place being taken as chief designer by Fred Murphy.

Subject of Licence No 18, two prototypes (X19 and X20) of this small two-bay biplane were authorized, and X19

appeared in September 1918. Rigged with scarcely any stagger, the wings were of fairly broad chord, and the upper wing - without conventional centre section - was attached to the top shoulders of the square-section fuselage. This was in keeping with Koolhoven’s latest preoccupation, that of setting the upper wing level with the pilot’s eyes.

The fuselage was a plain wooden box girder with flat ply sheet covering the sides, but without any attempt to provide any rounded decking. The engine was a 230hp Bentley B.R.2 rotary with a cowling that completely enveloped the cylinders, and included a fairly small aperture for cooling air entry. A most incongruous feature was a humped fairing, curving up from the front of the cowling to the top line of the upper wing, inside which were mounted the aircraft’s twin Vickers guns.

The reasoning behind this wing layout was obviously to provide the pilot with an excellent field of view forward and above, but the bulk of the nose and the lower wings severely restricted the pilot’s view of the ground, especially when landing, despite cutouts in the wings, and the aircraft was severely criticised on this account - not to mention many others.

It is difficult to understand what lay behind the production of this machine so late in the War for, with over one hundred horsepower more that the Le Rhone Camel of the previous year available, the speed performance of the Armadillo showed scarcely any advance. It is not known whether the second example was completed.

Type: Single-engine, single-seat, two-bay biplane fighter.

Manufacturer: Sir W G Armstrong, Whitworth & Co Ltd, Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

Powerplant: One 230hp Bentley B.R.2 rotary engine.

Dimensions: Span, 27ft 9in; length, 18ft 10in; height, 7ft 10in; wing area, 232 sq ft.

Weights: Tare, 1,250lb; all-up, 1,860lb.

Performance: Max speed, 125 mph at sea level; climb to 10,000ft, 6 min 30 sec; ceiling, 24,000ft.

Armament: Two synchronized 0.303in Vickers machine guns under fairing over the nose.

Prototypes: Two; X19 and X20 authorised under Licence No 18. X19 flown in September 1918; X20 may not have been completed. No production.

The first Armstrong, Whitworth F.M.4 Armadillo, X19; when it first appeared the undercarriage V-struts were much slimmer: in this photograph they appear to have been strengthened considerably.

Armstrong, Whitworth Ara

Unlike previous Armstrong Whitworth fighter aircraft the Ara, designed by Fred Murphy, was of orthodox configuration, although one or two features were unusual, and these tended to reflect a sense of awkwardness of gait.

Its design began in the summer of 1918 and followed what was to become a familiar path, ending in oblivion. No doubt persuaded that the rotary engine had reached the limit of its power potential, and perhaps disappointed by the modest performance of the Bentley-powered Armadillo, Murphy turned almost inevitably to the ABC Dragonfly, and produced a two-bay biplane of moderate stagger and small ailerons on upper and lower wings. The outboard pairs of interplane struts were located very close to the wingtips.

Reminiscent of the Armadillo’s flat-sided fuselage, the Ara’s box girder was scarcely tapered towards the tail, but was at least provided with a curved top decking; the relative thickness of the rear fuselage in side elevation served to accentuate the small area of the fin and rudder. The upper wing was mounted clear of the fuselage and sufficiently close to be in line with the pilot’s eye level.

Perhaps Murphy’s most noteworthy design feature was the pointed crankcase cowling of the Dragonfly, a highly practical and, it is assumed, efficient attempt to limit the drag of the untidy radial engine; while other Dragonfly-powered aircraft appeared with blunt cowlings, with little or no attempt to improve the shape of the propeller hub, Murphy achieved from the outset a near perfect solution.

The first prototype Ara, F4971, was completed in the spring of 1919, and was followed by a second aircraft on which the wing gap was increased so that not only was the upper wing raised slightly further above the fuselage but the lower wing was positioned about six inches below it.

Victim of the Dragonfly’s frustrating problems, the Ara passed into obscurity towards the end of 1919 following the closure of its manufacturer’s aviation department, despite an outstanding performance. No record of its handling qualities appears to have survived.

Type: Single-engine, single-seat, two-bay experimental biplane fighter.

Manufacturer: Sir W G Armstrong, Whitworth Co Ltd, Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

Powerplant: One 320hp ABC Dragonfly I nine-cylinder radial engine.

Dimensions: Span, 27ft 5in; length, 20ft 3in; height, 7ft 10in; wing area, 257 sq ft. Weights: Tare, 1,320lb; all-up, 1,930lb.

Performance: Max speed, 150 mph at sea level; climb to 10,000ft, 4 min 30 sec; ceiling, 28,000ft; endurance, 3 1/4 hr.

Armament: Two synchronized 0.303in Vickers machine guns mounted within the lower segments of the nose cowling.

Prototypes: Three, F4971-F4973 (first flown in mid-1919). No production.

Unlike previous Armstrong Whitworth fighter aircraft the Ara, designed by Fred Murphy, was of orthodox configuration, although one or two features were unusual, and these tended to reflect a sense of awkwardness of gait.

Its design began in the summer of 1918 and followed what was to become a familiar path, ending in oblivion. No doubt persuaded that the rotary engine had reached the limit of its power potential, and perhaps disappointed by the modest performance of the Bentley-powered Armadillo, Murphy turned almost inevitably to the ABC Dragonfly, and produced a two-bay biplane of moderate stagger and small ailerons on upper and lower wings. The outboard pairs of interplane struts were located very close to the wingtips.

Reminiscent of the Armadillo’s flat-sided fuselage, the Ara’s box girder was scarcely tapered towards the tail, but was at least provided with a curved top decking; the relative thickness of the rear fuselage in side elevation served to accentuate the small area of the fin and rudder. The upper wing was mounted clear of the fuselage and sufficiently close to be in line with the pilot’s eye level.

Perhaps Murphy’s most noteworthy design feature was the pointed crankcase cowling of the Dragonfly, a highly practical and, it is assumed, efficient attempt to limit the drag of the untidy radial engine; while other Dragonfly-powered aircraft appeared with blunt cowlings, with little or no attempt to improve the shape of the propeller hub, Murphy achieved from the outset a near perfect solution.

The first prototype Ara, F4971, was completed in the spring of 1919, and was followed by a second aircraft on which the wing gap was increased so that not only was the upper wing raised slightly further above the fuselage but the lower wing was positioned about six inches below it.

Victim of the Dragonfly’s frustrating problems, the Ara passed into obscurity towards the end of 1919 following the closure of its manufacturer’s aviation department, despite an outstanding performance. No record of its handling qualities appears to have survived.

Type: Single-engine, single-seat, two-bay experimental biplane fighter.

Manufacturer: Sir W G Armstrong, Whitworth Co Ltd, Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

Powerplant: One 320hp ABC Dragonfly I nine-cylinder radial engine.

Dimensions: Span, 27ft 5in; length, 20ft 3in; height, 7ft 10in; wing area, 257 sq ft. Weights: Tare, 1,320lb; all-up, 1,930lb.

Performance: Max speed, 150 mph at sea level; climb to 10,000ft, 4 min 30 sec; ceiling, 28,000ft; endurance, 3 1/4 hr.

Armament: Two synchronized 0.303in Vickers machine guns mounted within the lower segments of the nose cowling.

Prototypes: Three, F4971-F4973 (first flown in mid-1919). No production.

The first Ara prototype, F4971. It is not known when, or even whether this fighter was ever presented for Service evaluation at Martlesham Heath.

Siddeley S.R.2 Siskin

The following two aircraft, the Siddeley Siskin and the Nieuport Nighthawk, were the only aircraft, originally powered by the infamous ABC Dragonfly radial engine, to occupy a significant place in the history of British aviation, even though the original aircraft subsequently underwent a fair degree of alteration by foster parent companies.

The Siddeley-Deasy Motor Car Company of Coventry, apart from undertaking the manufacture of other companies’ designs during the First World War, began to build aircraft of inhouse design during 1917, after Maj F M Green, J Lloyd and S D Heron (formerly of the Royal Aircraft Factory) joined the firm in senior design appointments. After designing a modified version of the R.E.8 (taken from the production line and re-designated the R.T.1, but which was not put into production), Maj Green began detailed work on a design which he had sketched out while still at Farnborough, where he had intended using the 300hp RAF 8 fourteen-cylinder two-row radial engine, then under early development.

However, by the time the new aircraft design had begun to take shape early in 1918, aircraft designers were becoming enamoured with the potential offered by the ABC Dragonfly single-row radial which was claimed to possess an exceptionally good power/weight ratio. Green accordingly adopted this engine and tendered his design to Air Board Specification A.1A (which became RAF Specification Type I in April 1918). Based on the promised power/weight ratio of 0.53 bhp/lb, the aircraft was expected to achieve a top sea level speed of around 160 mph. In the event the Dragonfly never exceeded a figure of more than 0.445 bhp/lb. Nevertheless, Siddeley-Deasy received a contract in May to produce six prototypes, C4541-C4546. Owing to delayed delivery of the first engine cleared for flight, the first Siskin to fly (the third prototype, C4543) was not taken aloft until May 1919, and even then the engine was developing no more than about 270 hp.

The S.R.2 Siskin (named in accordance with TDI 506A and 538) was an attractive aeroplane, displaying much of the S.E.5’s character, though with interesting new features, not least of which was the undercarriage; this comprised single oleo struts for each wheel, each end of the axle being attached to the apices of paired V-struts by radius struts. The engine cowling was also novel, with each cylinder aligned to lie in a fluted channel in the crankcase cowling, this arrangement being intended to ensure the best possible cooling air flow through the cylinder fins. Like the S.E.5 and other Factory aircraft, the Siskin possessed tail fins above and below the rear fuselage. Despite the disappointing engine power, the Siskin returned a maximum speed of 145 mph at 6,500 feet when C4543 visited Martlesham Heath in July 1919.

By March 1920 the first five Siskin prototypes had flown, all with Dragonfly engines, even though it had already been decided to seek an alternative engine. Such an engine was near at hand. This was a development of the RAF 8 fourteen-cylinder engine referred to above. On leaving the Factory to join Siddeley-Deasy, S D Heron had sought and gained permission to continue its design development in his new appointment. Considerable progress was made before differences of opinion arose over cylinder design and Heron left the company to take up a design appointment in America. His departure resulted in a run-down in effort on the new engine, now named the Jaguar, until S M Viale took over the design late in 1919. By mid-1920 the engine was bench running and showing some promise, and an early Jaguar I, rated at 325 hp, was flown in the first Siskin prototype, C4541, on 20 March 1921.

By then a much improved version of the aircraft, the Armstrong Whitworth Siskin III had been ordered in prototype form and a whole new chapter in the Siskin’s life was about to open.

Type: Single-engine, single-seat, single-bay biplane fighter.

Manufacturer: The Siddeley-Deasy Motor Car Co Ltd, Coventry.

Specification: Air Board Specification A.1A (later RAF Type I).

Powerplant: One 320hp ABC Dragonfly I; later 325hp Siddeley Jaguar I.

Structure: Fabric and ply covered wooden box-girder construction.

Dimensions: Span, 27ft 6in; length, 21ft 3in; height, 9ft 9in; wing area, 247 sq ft.

Weights: Tare, 1,463lb; all-up, 2,181lb.

Performance: Max speed, 145 mph at 6,500ft; climb to 10,000ft, 7 min 50 sec; service ceiling, 23,800ft.

Armament: Two synchronized 0.303in Vickers machine guns on upper nose decking.

Prototypes: Six ordered, C4541-C4546 (first flight, May 1919, by C4543). No confirmation can be traced that C4546 was completed.

The following two aircraft, the Siddeley Siskin and the Nieuport Nighthawk, were the only aircraft, originally powered by the infamous ABC Dragonfly radial engine, to occupy a significant place in the history of British aviation, even though the original aircraft subsequently underwent a fair degree of alteration by foster parent companies.

The Siddeley-Deasy Motor Car Company of Coventry, apart from undertaking the manufacture of other companies’ designs during the First World War, began to build aircraft of inhouse design during 1917, after Maj F M Green, J Lloyd and S D Heron (formerly of the Royal Aircraft Factory) joined the firm in senior design appointments. After designing a modified version of the R.E.8 (taken from the production line and re-designated the R.T.1, but which was not put into production), Maj Green began detailed work on a design which he had sketched out while still at Farnborough, where he had intended using the 300hp RAF 8 fourteen-cylinder two-row radial engine, then under early development.

However, by the time the new aircraft design had begun to take shape early in 1918, aircraft designers were becoming enamoured with the potential offered by the ABC Dragonfly single-row radial which was claimed to possess an exceptionally good power/weight ratio. Green accordingly adopted this engine and tendered his design to Air Board Specification A.1A (which became RAF Specification Type I in April 1918). Based on the promised power/weight ratio of 0.53 bhp/lb, the aircraft was expected to achieve a top sea level speed of around 160 mph. In the event the Dragonfly never exceeded a figure of more than 0.445 bhp/lb. Nevertheless, Siddeley-Deasy received a contract in May to produce six prototypes, C4541-C4546. Owing to delayed delivery of the first engine cleared for flight, the first Siskin to fly (the third prototype, C4543) was not taken aloft until May 1919, and even then the engine was developing no more than about 270 hp.

The S.R.2 Siskin (named in accordance with TDI 506A and 538) was an attractive aeroplane, displaying much of the S.E.5’s character, though with interesting new features, not least of which was the undercarriage; this comprised single oleo struts for each wheel, each end of the axle being attached to the apices of paired V-struts by radius struts. The engine cowling was also novel, with each cylinder aligned to lie in a fluted channel in the crankcase cowling, this arrangement being intended to ensure the best possible cooling air flow through the cylinder fins. Like the S.E.5 and other Factory aircraft, the Siskin possessed tail fins above and below the rear fuselage. Despite the disappointing engine power, the Siskin returned a maximum speed of 145 mph at 6,500 feet when C4543 visited Martlesham Heath in July 1919.

By March 1920 the first five Siskin prototypes had flown, all with Dragonfly engines, even though it had already been decided to seek an alternative engine. Such an engine was near at hand. This was a development of the RAF 8 fourteen-cylinder engine referred to above. On leaving the Factory to join Siddeley-Deasy, S D Heron had sought and gained permission to continue its design development in his new appointment. Considerable progress was made before differences of opinion arose over cylinder design and Heron left the company to take up a design appointment in America. His departure resulted in a run-down in effort on the new engine, now named the Jaguar, until S M Viale took over the design late in 1919. By mid-1920 the engine was bench running and showing some promise, and an early Jaguar I, rated at 325 hp, was flown in the first Siskin prototype, C4541, on 20 March 1921.

By then a much improved version of the aircraft, the Armstrong Whitworth Siskin III had been ordered in prototype form and a whole new chapter in the Siskin’s life was about to open.

Type: Single-engine, single-seat, single-bay biplane fighter.

Manufacturer: The Siddeley-Deasy Motor Car Co Ltd, Coventry.

Specification: Air Board Specification A.1A (later RAF Type I).

Powerplant: One 320hp ABC Dragonfly I; later 325hp Siddeley Jaguar I.

Structure: Fabric and ply covered wooden box-girder construction.

Dimensions: Span, 27ft 6in; length, 21ft 3in; height, 9ft 9in; wing area, 247 sq ft.

Weights: Tare, 1,463lb; all-up, 2,181lb.

Performance: Max speed, 145 mph at 6,500ft; climb to 10,000ft, 7 min 50 sec; service ceiling, 23,800ft.

Armament: Two synchronized 0.303in Vickers machine guns on upper nose decking.

Prototypes: Six ordered, C4541-C4546 (first flight, May 1919, by C4543). No confirmation can be traced that C4546 was completed.

Austin-Ball A.F.B.1

Captain Albert Ball was still only nineteen years of age in April 1916, while flying B.E.2Cs on reconnaissance flights over the Western Front with No 13 Squadron, RFC. In a letter, written that month to his parents he tells of his idea for an aircraft ‘better than the Fokker’. Several months later, while on leave in England, Ball met representatives of the Austin Motor Company, who in turn approached the Air Board to seek an order to build two examples of Ball’s aircraft. It was, however, Ball himself who secured the order by going straight to Maj-Gen Sefton Brancker, Director of Air Organisation.

It is a quirk of irony that, when Ball expressed his first ideas for his fighter, he had not yet been in combat, yet by the time the Austin-Ball A.F.B.1 was ready for flight in July 1917, the young pilot had been dead for two months - killed on active service on 7 May after gaining a total of 44 air victories and being awarded the Victoria Cross, three DSOs and the MC, all before his 21st birthday.

Ball’s aircraft reflected his particular style of combat, a fast single-seater and an upward-firing gun with which to rake an enemy aircraft from below. It was a portly, single-bay biplane, powered by the 200hp Hispano-Suiza, and armed with one Lewis gun firing through the hollow propeller shaft and another on a Foster mounting on the upper wing. A well-shaped nose cowling was made possible by mounting the engine radiators on the fuselage sides, while the deep fuselage allowed the top wing to be located close to the fuselage - thereby providing the pilot with an excellent field of view over the wing, and at the same time retaining a good wing gap. The only significant criticism levelled at the design concerned the absence of a fixed tail fin, a deficiency that was evidenced by poor lateral control, although the rudder was balanced.

When first tested at Martlesham Heath in July 1917, the un-numbered A.F.B.1 returned the excellent top speed of 138 mph at sea level, and could reach 10,000 feet in under nine minutes. While this performance was at least comparable with that of the the S.E.5A, and superior to the Camel, the forward armament of a hub-firing Lewis gun - though radical by 1916 standards - was not favoured in an era of twin synchronized Vickers. Nevertheless, there was more irony in the fact that Ball never became fully reconciled with the S.E.5 (preferring the nimble Nieuport), yet his aircraft was clearly conceived along similar lines. Moreover there is some circumstantial evidence to suggest that it was in recognition of Austin’s perseverence with the A.F.B.1 that the company was awarded a huge production contract - for over 800 S.E.5As!

Type: Single-engine, single-seat, single-bay biplane fighting scout.

Manufacturer: The Austin Motor Co (1914) Ltd, Birmingham.

Powerplant: One 200hp Hispano-Suiza engine driving four-blade propeller.

Dimensions: Span, 30ft 0in; length, 21ft 6in; height, 9ft 3in; wing area, 290 sq ft.

Weights: Tare, 1,525lb; all-up, 2,077lb.

Performance: Max speed, 138 mph at sea level; climb to 10,000ft, 8 min 55 sec; service ceiling, 22,000ft; endurance, 2 1/4 hr.

Armament: One 0.303in Lewis machine gun firing through hollow propeller shaft, and one Lewis gun on Foster mounting on upper wing centre section.

Prototype: Two A.F.B.1s were ordered, but it is believed that the second was not completed. No production.

Captain Albert Ball was still only nineteen years of age in April 1916, while flying B.E.2Cs on reconnaissance flights over the Western Front with No 13 Squadron, RFC. In a letter, written that month to his parents he tells of his idea for an aircraft ‘better than the Fokker’. Several months later, while on leave in England, Ball met representatives of the Austin Motor Company, who in turn approached the Air Board to seek an order to build two examples of Ball’s aircraft. It was, however, Ball himself who secured the order by going straight to Maj-Gen Sefton Brancker, Director of Air Organisation.

It is a quirk of irony that, when Ball expressed his first ideas for his fighter, he had not yet been in combat, yet by the time the Austin-Ball A.F.B.1 was ready for flight in July 1917, the young pilot had been dead for two months - killed on active service on 7 May after gaining a total of 44 air victories and being awarded the Victoria Cross, three DSOs and the MC, all before his 21st birthday.

Ball’s aircraft reflected his particular style of combat, a fast single-seater and an upward-firing gun with which to rake an enemy aircraft from below. It was a portly, single-bay biplane, powered by the 200hp Hispano-Suiza, and armed with one Lewis gun firing through the hollow propeller shaft and another on a Foster mounting on the upper wing. A well-shaped nose cowling was made possible by mounting the engine radiators on the fuselage sides, while the deep fuselage allowed the top wing to be located close to the fuselage - thereby providing the pilot with an excellent field of view over the wing, and at the same time retaining a good wing gap. The only significant criticism levelled at the design concerned the absence of a fixed tail fin, a deficiency that was evidenced by poor lateral control, although the rudder was balanced.

When first tested at Martlesham Heath in July 1917, the un-numbered A.F.B.1 returned the excellent top speed of 138 mph at sea level, and could reach 10,000 feet in under nine minutes. While this performance was at least comparable with that of the the S.E.5A, and superior to the Camel, the forward armament of a hub-firing Lewis gun - though radical by 1916 standards - was not favoured in an era of twin synchronized Vickers. Nevertheless, there was more irony in the fact that Ball never became fully reconciled with the S.E.5 (preferring the nimble Nieuport), yet his aircraft was clearly conceived along similar lines. Moreover there is some circumstantial evidence to suggest that it was in recognition of Austin’s perseverence with the A.F.B.1 that the company was awarded a huge production contract - for over 800 S.E.5As!

Type: Single-engine, single-seat, single-bay biplane fighting scout.

Manufacturer: The Austin Motor Co (1914) Ltd, Birmingham.

Powerplant: One 200hp Hispano-Suiza engine driving four-blade propeller.

Dimensions: Span, 30ft 0in; length, 21ft 6in; height, 9ft 3in; wing area, 290 sq ft.

Weights: Tare, 1,525lb; all-up, 2,077lb.

Performance: Max speed, 138 mph at sea level; climb to 10,000ft, 8 min 55 sec; service ceiling, 22,000ft; endurance, 2 1/4 hr.

Armament: One 0.303in Lewis machine gun firing through hollow propeller shaft, and one Lewis gun on Foster mounting on upper wing centre section.

Prototype: Two A.F.B.1s were ordered, but it is believed that the second was not completed. No production.

The Austin-Ball A.F.B.1. It has often been incorrectly suggested that the aircraft possessed anhedral on the wings, probably stemming from an optical illusion created by the small sweepback on the parallel-chord surfaces.

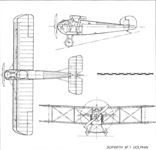

Austin A.F.T.3 Osprey

It has been shown that, in 1917, the Austin Motor Company was already making positive efforts to contribute aircraft of its own origination, even though the Austin-Ball A.F.B.1 was not strictly the company’s own design. The issue that year by the War Office of an official Specification, A.1A, for a successor to the Sopwith Camel was an added spur to perseverance.

Before John North left Austin to join Boulton & Paul, he had schemed up the design of a small triplane fighter, much on the lines of the Sopwith Clerget Triplane, but intended for the new Bentley B.R.2 rotary engine. John Kenworthy now left the Royal Aircraft Factory - where he had been engaged in the design of the S.E.5 - to join Austin as chief designer, and took over responsibility for the new triplane, termed the A.F.T.3 (and later named the Osprey).

Despite it being officially notified as a contender to meet an Air Board requirement, Kenworthy discovered that Austin was required to obtain a licence to build prototypes under the new Regulations, and this may conceivably reflect the Air Board’s belief that the triplane configuration would no longer be adequate to meet the new operational requirement. Such prejudice may have been justifiable, having regard to the relatively high performance already being demonstrated by conventional biplanes, but certainly suggests that the Austin aeroplane was compromised from the start.

Nevertheless, Licence No 17 was issued for the manufacture of three prototypes, X15-X17. The Osprey was an attractive little aircraft, being flown early in 1918 and submitted for evaluation in March (by which time the Sopwith Snipe had already been adjudged the successful contender under Specification A.1A). Built very much on the lines of the Sopwith Clerget Triplane, with wooden box-girder fuselage, the Austin was a smaller aircraft, although its wing gaps were deeper and the wing chord greater. Considerable thought had been given to simplicity of construction and ease of maintenance, all six ailerons being interchangeable, as were the interplane struts. An interesting undercarriage feature (obviously ‘borrowed’ from Austin cars) was the attachment of a leaf-spring to the centre of the spreader bar, extending outwards to the bottom of the V-struts and attached to the half-axles at its extremities, which were bound with elastic chord.

The rudder was a small angular, balanced surface, but no fixed fin was fitted, and the tailplane was adjustable in flight. The armament comprised twin synchronized Vickers guns on the nose decking and, as originally called for in Specification A.1A, provision had been made to mount a Lewis gun on the steel tubular carry-through members of the centre wing.

After the announcement of the Sopwith Snipe’s success, Austin stopped work on the Osprey, and the other two prototypes remained unbuilt after the withdrawal of the Licence.

Type: Single-engine, single-seat, two-bay triplane fighter.

Manufacturer: The Austin Motor Co (1914) Ltd, Birmingham.

Powerplant: One 230hp Bentley B.R.2 rotary engine driving two-blade propeller. Dimensions: Span, 23ft 0in; length, 17ft 7in; height, 10ft 8in; wing area, 233 sq ft.

Weights: Tare, 1,106lb; all-up, 1,888lb.

Performance: Max speed, 118.5 mph at 10,000ft; climb to 10,000ft, 10 min 20 sec; service ceiling, 19,000ft.

Armament: Two synchronized 0.303in Vickers machine guns on fuselage decking forward of cockpit; provision originally made for one Lewis gun on centre wing carry-through structure.

Prototypes: Three ordered, X15-X17, under Licence No 17; X16 and X17 not completed.

It has been shown that, in 1917, the Austin Motor Company was already making positive efforts to contribute aircraft of its own origination, even though the Austin-Ball A.F.B.1 was not strictly the company’s own design. The issue that year by the War Office of an official Specification, A.1A, for a successor to the Sopwith Camel was an added spur to perseverance.

Before John North left Austin to join Boulton & Paul, he had schemed up the design of a small triplane fighter, much on the lines of the Sopwith Clerget Triplane, but intended for the new Bentley B.R.2 rotary engine. John Kenworthy now left the Royal Aircraft Factory - where he had been engaged in the design of the S.E.5 - to join Austin as chief designer, and took over responsibility for the new triplane, termed the A.F.T.3 (and later named the Osprey).

Despite it being officially notified as a contender to meet an Air Board requirement, Kenworthy discovered that Austin was required to obtain a licence to build prototypes under the new Regulations, and this may conceivably reflect the Air Board’s belief that the triplane configuration would no longer be adequate to meet the new operational requirement. Such prejudice may have been justifiable, having regard to the relatively high performance already being demonstrated by conventional biplanes, but certainly suggests that the Austin aeroplane was compromised from the start.

Nevertheless, Licence No 17 was issued for the manufacture of three prototypes, X15-X17. The Osprey was an attractive little aircraft, being flown early in 1918 and submitted for evaluation in March (by which time the Sopwith Snipe had already been adjudged the successful contender under Specification A.1A). Built very much on the lines of the Sopwith Clerget Triplane, with wooden box-girder fuselage, the Austin was a smaller aircraft, although its wing gaps were deeper and the wing chord greater. Considerable thought had been given to simplicity of construction and ease of maintenance, all six ailerons being interchangeable, as were the interplane struts. An interesting undercarriage feature (obviously ‘borrowed’ from Austin cars) was the attachment of a leaf-spring to the centre of the spreader bar, extending outwards to the bottom of the V-struts and attached to the half-axles at its extremities, which were bound with elastic chord.

The rudder was a small angular, balanced surface, but no fixed fin was fitted, and the tailplane was adjustable in flight. The armament comprised twin synchronized Vickers guns on the nose decking and, as originally called for in Specification A.1A, provision had been made to mount a Lewis gun on the steel tubular carry-through members of the centre wing.

After the announcement of the Sopwith Snipe’s success, Austin stopped work on the Osprey, and the other two prototypes remained unbuilt after the withdrawal of the Licence.

Type: Single-engine, single-seat, two-bay triplane fighter.

Manufacturer: The Austin Motor Co (1914) Ltd, Birmingham.

Powerplant: One 230hp Bentley B.R.2 rotary engine driving two-blade propeller. Dimensions: Span, 23ft 0in; length, 17ft 7in; height, 10ft 8in; wing area, 233 sq ft.

Weights: Tare, 1,106lb; all-up, 1,888lb.

Performance: Max speed, 118.5 mph at 10,000ft; climb to 10,000ft, 10 min 20 sec; service ceiling, 19,000ft.

Armament: Two synchronized 0.303in Vickers machine guns on fuselage decking forward of cockpit; provision originally made for one Lewis gun on centre wing carry-through structure.

Prototypes: Three ordered, X15-X17, under Licence No 17; X16 and X17 not completed.

Austin Greyhound

As the Austin Osprey was undergoing its flight trials in March 1918, the design of Austin’s last wartime military product was submitted to the Air Board on news that a new Specification was about to be issued for a Bristol Fighter replacement. The new design was the handsome Greyhound, a two-seat, two-bay biplane of strictly conventional appearance and construction. Unlike the privately-funded Sopwith Bulldog, the Greyhound was officially sponsored from the start and was therefore among the first aircraft to be allotted the new 320hp ABC Dragonfly I, a nine-cylinder aircooled engine on which many hopes were to be pinned. In due course the new Air Ministry’s Specification Type III was issued and the Greyhound seemed a promising contender for acceptance.

Designed by John Kenworthy, the Greyhound featured a flat-sided and fairly deep fuselage, the pilot and observer/ gunner enjoying an excellent field of view, this being partly afforded by a lower wing of narrow chord. The wings, rigged with moderate stagger, were of unequal span and chord, and carried ailerons top and bottom. The tail comprised fixed ventral and dorsal fins, with the tailskid integral with a triangular segment below the rudder - reminiscent of the S.E.5A. The rudder’s horn balance was faired to provide an unbroken outline with the dorsal fin.

Although quickly completed during the summer of 1918, under a contract signed on 18 May, the first of three prototypes was held up by prolonged engine trials, and it was the second aircraft, H4318, which underwent official evaluation at Martlesham Heath in January 1919. H4317 followed on 15 May that year, and remained with the A & AEE until September 1920. The third aircraft made its maiden flight in February 1920, the same month that H4318 was delivered to the RAE (the Factory at Farnborough having been renamed an Establishment to avoid confusion with the new RAF), but was damaged and written off after a landing accident on 29 August 1921.

Despite an enormous amount of work on it, the Dragonfly engine never truly succeeded in overcoming its fundamental mechanical weaknesses and brought about the abandonment of numerous promising aircraft, among them the attractive Greyhound. It might have proved possible to substitute another engine had such a decision been taken early on, but after the Armistice aircraft production contracts were being severely cut back, and the design staff at Austin was, in any case, quickly shrinking.

Type: Single-engine, two-seat, two-bay biplane fighter.

Manufacturer: The Austin Motor Co (1914) Ltd, Birmingham.

Air Ministry Specification: Type III of 1918.

Powerplant: One 320hp ABC Dragonfly I nine-cylinder air-cooled radial engine driving two-blade propeller.

Structure: All-wooden construction with fabric, ply and aluminium sheet covering.

Dimensions: Span, 39ft 0in; length, 26ft 8 1/2 in; height, 10ft 4in; wing area, 400 sq ft.

Weights: Tare, 1,838lb; all-up, 3,032lb.

Performance: Max speed, 134 mph at sea level, 126 mph at 10,000ft; climb to 10,000ft, 10 min 50 sec; service ceiling, 22,000ft; endurance, 3 hr.

Armament: Two synchronized 0.303in Vickers Mk I machine guns in nose, and one Lewis gun with Scarff ring on rear cockpit.

Prototypes: Three, H4317-H4319; all built, but no subsequent production.

As the Austin Osprey was undergoing its flight trials in March 1918, the design of Austin’s last wartime military product was submitted to the Air Board on news that a new Specification was about to be issued for a Bristol Fighter replacement. The new design was the handsome Greyhound, a two-seat, two-bay biplane of strictly conventional appearance and construction. Unlike the privately-funded Sopwith Bulldog, the Greyhound was officially sponsored from the start and was therefore among the first aircraft to be allotted the new 320hp ABC Dragonfly I, a nine-cylinder aircooled engine on which many hopes were to be pinned. In due course the new Air Ministry’s Specification Type III was issued and the Greyhound seemed a promising contender for acceptance.

Designed by John Kenworthy, the Greyhound featured a flat-sided and fairly deep fuselage, the pilot and observer/ gunner enjoying an excellent field of view, this being partly afforded by a lower wing of narrow chord. The wings, rigged with moderate stagger, were of unequal span and chord, and carried ailerons top and bottom. The tail comprised fixed ventral and dorsal fins, with the tailskid integral with a triangular segment below the rudder - reminiscent of the S.E.5A. The rudder’s horn balance was faired to provide an unbroken outline with the dorsal fin.

Although quickly completed during the summer of 1918, under a contract signed on 18 May, the first of three prototypes was held up by prolonged engine trials, and it was the second aircraft, H4318, which underwent official evaluation at Martlesham Heath in January 1919. H4317 followed on 15 May that year, and remained with the A & AEE until September 1920. The third aircraft made its maiden flight in February 1920, the same month that H4318 was delivered to the RAE (the Factory at Farnborough having been renamed an Establishment to avoid confusion with the new RAF), but was damaged and written off after a landing accident on 29 August 1921.

Despite an enormous amount of work on it, the Dragonfly engine never truly succeeded in overcoming its fundamental mechanical weaknesses and brought about the abandonment of numerous promising aircraft, among them the attractive Greyhound. It might have proved possible to substitute another engine had such a decision been taken early on, but after the Armistice aircraft production contracts were being severely cut back, and the design staff at Austin was, in any case, quickly shrinking.

Type: Single-engine, two-seat, two-bay biplane fighter.

Manufacturer: The Austin Motor Co (1914) Ltd, Birmingham.

Air Ministry Specification: Type III of 1918.

Powerplant: One 320hp ABC Dragonfly I nine-cylinder air-cooled radial engine driving two-blade propeller.

Structure: All-wooden construction with fabric, ply and aluminium sheet covering.

Dimensions: Span, 39ft 0in; length, 26ft 8 1/2 in; height, 10ft 4in; wing area, 400 sq ft.

Weights: Tare, 1,838lb; all-up, 3,032lb.

Performance: Max speed, 134 mph at sea level, 126 mph at 10,000ft; climb to 10,000ft, 10 min 50 sec; service ceiling, 22,000ft; endurance, 3 hr.

Armament: Two synchronized 0.303in Vickers Mk I machine guns in nose, and one Lewis gun with Scarff ring on rear cockpit.

Prototypes: Three, H4317-H4319; all built, but no subsequent production.

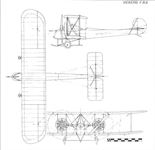

Avro Type 504 Night Fighters

It is of course well known that the Avro 504 was the most widely-used British training aircraft of the First World War, no fewer than 8,340 examples being produced during the War itself (and many others afterwards). Scarcely recalled is the fact that specially converted versions were used as early as 1915 on anti-Zeppelin patrols. On 15 May that year Flt Sub-Lt Mulock, flying an Avro, intercepted LZ38, but was unable to attack it with his two grenades and two incendiary bombs before the enemy airship climbed away from the fighter.

Following such early efforts as these, it was decided to convert the Avro 504 to a single-seater for the anti-Zeppelin role, fitting an extra fuel tank in place of the front cockpit, and arming it with a Lewis gun mounted to fire upwards through a cutout in the upper wing centre section. With an endurance of no less than eight hours, this version was termed the Avro 504C, with a low aspect ratio fin for the RNAS, and the 504D, without fin for the RFC. These aircraft were powered by 80hp Gnome rotaries.

Of much greater significance was the decision, taken early in the winter of 1916-17, to equip Home Defence squadrons with the Avro 504J and K, again modified as single-seaters, but now armed with a Lewis gun on a Foster mounting above the wing; the gravity fuel tank was moved from the centre of the wing to the port side. Power was provided by either a 100hp Gnome monosoupape engine or a 110hp Le Rhone, and these aircraft could reach an altitude of 18,000 feet; they were specifically introduced to replace the RFC’s aging B.E.2Cs, whose ceiling was little more than 12,000 feet. One other motive for this decision was to enable the night fighter pilots, who would soon be flying the tricky Camel at night, to gain experience with a rotary-powered tractor fighter. In the event, no fewer than 226 Avro 504J and K night fighters were still flying with the Home Defence units, including five squadrons, at the time of the Armistice.

The accompanying data table refers to the Avro 504K night fighter of 1918.

Type: Single-engine, single-seat, two-bay biplane night fighter.

Manufacturers: A V Roe & Co Ltd, Manchester and Hamble, Hampshire; The Grahame-White Aviation Co Ltd, Hendon, London; The Humber Motor Co Ltd, Coventry.

Powerplant: One 100hp Gnome monosoupape engine; 100hp Le Rhone; 110hp Clerget. Span, 36ft 0in; length, 29ft 5in; height, 10ft 5in; wing area, 330 sq ft.

Weights: (Mono-Gnome). Tare, 1,100lb; all-up, 1,800lb.

Performance: (Mono-Gnome). Max speed, 94 mph at sea level; climb to 10,000ft, 15 min 30 sec; absolute ceiling, 18,200ft; endurance, 3 1/2 hr.

Armament: One 0.303in Lewis gun with Foster mounting on upper wing centre section. Production: Total of 274 Avro 504Js and Ks issued to Home Defence units during 1918. Summary of Service: Avro 504Js and Ks served with Nos 33, 36, 51, 75, 77, 90, 92 and 155 (Home Defence) Squadrons, RFC and RAF, during 1918, and with Nos 186, 187, 188, 189, 190 and 198 (Night Fighter Training) Squadrons.

It is of course well known that the Avro 504 was the most widely-used British training aircraft of the First World War, no fewer than 8,340 examples being produced during the War itself (and many others afterwards). Scarcely recalled is the fact that specially converted versions were used as early as 1915 on anti-Zeppelin patrols. On 15 May that year Flt Sub-Lt Mulock, flying an Avro, intercepted LZ38, but was unable to attack it with his two grenades and two incendiary bombs before the enemy airship climbed away from the fighter.

Following such early efforts as these, it was decided to convert the Avro 504 to a single-seater for the anti-Zeppelin role, fitting an extra fuel tank in place of the front cockpit, and arming it with a Lewis gun mounted to fire upwards through a cutout in the upper wing centre section. With an endurance of no less than eight hours, this version was termed the Avro 504C, with a low aspect ratio fin for the RNAS, and the 504D, without fin for the RFC. These aircraft were powered by 80hp Gnome rotaries.

Of much greater significance was the decision, taken early in the winter of 1916-17, to equip Home Defence squadrons with the Avro 504J and K, again modified as single-seaters, but now armed with a Lewis gun on a Foster mounting above the wing; the gravity fuel tank was moved from the centre of the wing to the port side. Power was provided by either a 100hp Gnome monosoupape engine or a 110hp Le Rhone, and these aircraft could reach an altitude of 18,000 feet; they were specifically introduced to replace the RFC’s aging B.E.2Cs, whose ceiling was little more than 12,000 feet. One other motive for this decision was to enable the night fighter pilots, who would soon be flying the tricky Camel at night, to gain experience with a rotary-powered tractor fighter. In the event, no fewer than 226 Avro 504J and K night fighters were still flying with the Home Defence units, including five squadrons, at the time of the Armistice.

The accompanying data table refers to the Avro 504K night fighter of 1918.

Type: Single-engine, single-seat, two-bay biplane night fighter.

Manufacturers: A V Roe & Co Ltd, Manchester and Hamble, Hampshire; The Grahame-White Aviation Co Ltd, Hendon, London; The Humber Motor Co Ltd, Coventry.

Powerplant: One 100hp Gnome monosoupape engine; 100hp Le Rhone; 110hp Clerget. Span, 36ft 0in; length, 29ft 5in; height, 10ft 5in; wing area, 330 sq ft.

Weights: (Mono-Gnome). Tare, 1,100lb; all-up, 1,800lb.

Performance: (Mono-Gnome). Max speed, 94 mph at sea level; climb to 10,000ft, 15 min 30 sec; absolute ceiling, 18,200ft; endurance, 3 1/2 hr.

Armament: One 0.303in Lewis gun with Foster mounting on upper wing centre section. Production: Total of 274 Avro 504Js and Ks issued to Home Defence units during 1918. Summary of Service: Avro 504Js and Ks served with Nos 33, 36, 51, 75, 77, 90, 92 and 155 (Home Defence) Squadrons, RFC and RAF, during 1918, and with Nos 186, 187, 188, 189, 190 and 198 (Night Fighter Training) Squadrons.

A high altitude Home Defence Avro 504K single seater with Lewis gun on the top centre section.

A Humber-built Avro 504K single-seat night fighter of a Home Defence unit, with Lewis gun on Foster mounting.

A Humber-built Avro 504K single-seat night fighter of a Home Defence unit, with Lewis gun on Foster mounting.

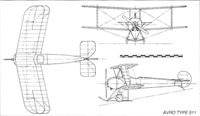

Avro Type 508

One of several companies which tried their hand at gun-carrier biplanes in the two years before the War was A V Roe & Co Ltd, a manufacturer that had made long strides since its founder, the pioneering pilot-designer Alliott Verdon Roe, had taken his first faltering steps into the air on 8 June 1908 at Brooklands. By the time the Avro 508 was produced in December 1913 the company had already launched the Type 504 - the most widely used trainer flown in Britain during the First World War.

The Type 508 was a two-seat, three-bay pusher biplane whose square-section nacelle was constructed of ash longerons and spruce struts and was fabric-covered; it accommodated an observer-gunner in the nose and the pilot amidships, forward of the fuel tank. At the rear, carried on steel tubular bearers, the 80hp Gnome rotary drove a two-blade pusher propeller. Ailerons were fitted on both upper and lower wings.

The aircraft was exhibited in an in complete state at Belle Vue Gardens, Manchester, on New Year’s Day, 1914, and the following month appeared in its finished state on the Avro stand at the Olympia Aero Show in London.

The Avro 508 won no production order, probably on account of being somewhat underpowered. Indeed it is not known for certain whether the single example was ever flown.

Type: Single pusher engine, two-seat three-bay gun carrier biplane.

Manufacturer: A V Roe & Co Ltd, Miles Platting, Manchester, and Brooklands, Surrey

Powerplant: One 80hp Gnome rotary air-cooled engine driving two-blade pusher propeller.

Structure: Wings and nacelle constructed in wood with fabric covering; steel tubular engine bearers. Twin-wheel and single-skid undercarriage.

Dimensions: Span, 44ft 0in; length, 26ft 9in; height, 10ft 0in; wing area, 468 sq ft.

Weights: Tare, 1,000lb; all-up, 1,680lb.

Performance: Max speed, 65 mph at sea level; endurance, 4 1/2 hr.

Armament: Provision intended for a single machine gun on nose of nacelle.

Prototype: One (possibly not flown); no production.

One of several companies which tried their hand at gun-carrier biplanes in the two years before the War was A V Roe & Co Ltd, a manufacturer that had made long strides since its founder, the pioneering pilot-designer Alliott Verdon Roe, had taken his first faltering steps into the air on 8 June 1908 at Brooklands. By the time the Avro 508 was produced in December 1913 the company had already launched the Type 504 - the most widely used trainer flown in Britain during the First World War.

The Type 508 was a two-seat, three-bay pusher biplane whose square-section nacelle was constructed of ash longerons and spruce struts and was fabric-covered; it accommodated an observer-gunner in the nose and the pilot amidships, forward of the fuel tank. At the rear, carried on steel tubular bearers, the 80hp Gnome rotary drove a two-blade pusher propeller. Ailerons were fitted on both upper and lower wings.

The aircraft was exhibited in an in complete state at Belle Vue Gardens, Manchester, on New Year’s Day, 1914, and the following month appeared in its finished state on the Avro stand at the Olympia Aero Show in London.

The Avro 508 won no production order, probably on account of being somewhat underpowered. Indeed it is not known for certain whether the single example was ever flown.

Type: Single pusher engine, two-seat three-bay gun carrier biplane.

Manufacturer: A V Roe & Co Ltd, Miles Platting, Manchester, and Brooklands, Surrey

Powerplant: One 80hp Gnome rotary air-cooled engine driving two-blade pusher propeller.

Structure: Wings and nacelle constructed in wood with fabric covering; steel tubular engine bearers. Twin-wheel and single-skid undercarriage.

Dimensions: Span, 44ft 0in; length, 26ft 9in; height, 10ft 0in; wing area, 468 sq ft.

Weights: Tare, 1,000lb; all-up, 1,680lb.

Performance: Max speed, 65 mph at sea level; endurance, 4 1/2 hr.

Armament: Provision intended for a single machine gun on nose of nacelle.

Prototype: One (possibly not flown); no production.