Книги

Putnam

C.Andrews

Vickers Aircraft since 1908

117

C.Andrews - Vickers Aircraft since 1908 /Putnam/

The Maxim Flying Machine

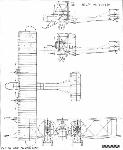

Although Vickers were not directly concerned with the flying machine invented by Hiram S. Maxim, an American living in England, a short note is presented here of his pioneering efforts in aeronautics, because of his subsequent association with Vickers, Sons and Maxim Ltd. His firm, Maxim Nordenfelt Guns and Ammunition Co Ltd was acquired by Vickers Sons and Co Ltd in 1897, and his original Maxim machine-gun was developed into the Vickers gun, which was widely used in military aircraft.

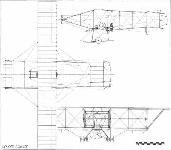

Maxim's aeroplane was an ungainly structure with five sets of wings, the three centre pairs of which could be removed to vary the wing area from 5,400 to 4,000 sq ft. The total weight of the machine was about 4,000 lb, and it was powered with two compound steam engines fed by a water-tube boiler. They developed 363 hp each and drove a propeller of 17 ft 10-in diameter at 375 rpm. The weight of each engine was about 320 lb, but the boiler added some 800 lb. This boiler was mounted on a midships platform which also carried the crew of three, with the controls and water tanks. The overall span was 125 ft and the length was 104 ft.

The Maxim machine was tested by its inventor in Baldwyn's Park, Bexley, Kent, in July 1894. It was mounted on a specially constructed railway track of 9-ft gauge, with a secondary wooden track of 35-ft gauge on the outside inverted to prevent the machine rising more than a few inches for the preliminary experiments.

As with other early attempts to fly a heavier-than-air craft, evidence was obtained that Maxim's machine did rise off the ground. But the uncontrollability common to all attempts prior to the Wright brothers became catastrophic during the first trials and the machine was wrecked, without injury to Maxim and his assistants. It had cost Maxim over ?20,000. Later he became a British citizen and was knighted.

Although Vickers were not directly concerned with the flying machine invented by Hiram S. Maxim, an American living in England, a short note is presented here of his pioneering efforts in aeronautics, because of his subsequent association with Vickers, Sons and Maxim Ltd. His firm, Maxim Nordenfelt Guns and Ammunition Co Ltd was acquired by Vickers Sons and Co Ltd in 1897, and his original Maxim machine-gun was developed into the Vickers gun, which was widely used in military aircraft.

Maxim's aeroplane was an ungainly structure with five sets of wings, the three centre pairs of which could be removed to vary the wing area from 5,400 to 4,000 sq ft. The total weight of the machine was about 4,000 lb, and it was powered with two compound steam engines fed by a water-tube boiler. They developed 363 hp each and drove a propeller of 17 ft 10-in diameter at 375 rpm. The weight of each engine was about 320 lb, but the boiler added some 800 lb. This boiler was mounted on a midships platform which also carried the crew of three, with the controls and water tanks. The overall span was 125 ft and the length was 104 ft.

The Maxim machine was tested by its inventor in Baldwyn's Park, Bexley, Kent, in July 1894. It was mounted on a specially constructed railway track of 9-ft gauge, with a secondary wooden track of 35-ft gauge on the outside inverted to prevent the machine rising more than a few inches for the preliminary experiments.

As with other early attempts to fly a heavier-than-air craft, evidence was obtained that Maxim's machine did rise off the ground. But the uncontrollability common to all attempts prior to the Wright brothers became catastrophic during the first trials and the machine was wrecked, without injury to Maxim and his assistants. It had cost Maxim over ?20,000. Later he became a British citizen and was knighted.

S.E.5a fighter production in the first world war at the Birmingham works of Wolseley Motors, then a Vickers subsidiary.

S.E.5a production at Weybridge in the first world war; 1,650 were made there, by far the highest total in the country.

Vickers S.E.5a development of 1921 with Wolseley Viper, Vixen-type radiator, oleo undercarriage and dihedral on bottom wing only.

The Early Monoplanes

Vickers, Sons and Maxim presented a strong case to the Admiralty on 3 January, 1911, offering to supply one Pelterie-type monoplane for ? 1,500. They stressed the point that the framework of the proposed machine, except the wings, was of steel, with a possible substitution of duralumin in later models. In reply, the Admiralty expressed disinterest, and consequently no order materialised. This approach was of some historical significance, for it presaged the adherence of Vickers to advanced structural philosophies and to metal construction in particular. At that time there were few metal aeroplanes.

The metal-tube airframe was indeed the only outstanding characteristic of the early Vickers monoplanes. Beyond the fact that they were quite strong for the performance then prevailing, they had little else to commend them. They were heavy for the limited power of the standard R.E.P. engine, and attempts were made to improve their power/weight ratio by using Gnome or other engines of greater power. The small margin between flying and stalling speeds made them tricky to fly, especially with the lack of power and the absence of inherent stability, the problems of which had still to be solved at that time.

Those were the pioneering days. The hardy aviators who took to the air in flying machines had perforce to learn the hard way. The Vickers monoplanes, with their steel-tube fuselages, were capable of absorbing rougher usage than contemporary wooden aircraft. With their rigid airframes they were also more easily transported, whereas wooden aircraft were easily damaged in transit.

No. 1 monoplane was part Pelterie (rear fuselage), but the rest was of Vickers construction. Comparing the standard R.E.P with Vickers' first effort, various small modifications appear to have been made. One of the difficulties encountered in building French aircraft under licence was the conversion of metric mensuration into feet and inches, consequently most of the original drawings had to be redrawn to British practice, although it is true that certain constructors, like Bristol and Martin-Handasyde, adopted the metric system throughout their original designs.

The first monoplane was built in the Erith works of Vickers, Sons and Maxim and not at Barrow-in-Furness as was suggested in the proposals to the Admiralty. H. F. Field was works foreman in charge, and he controlled a small number of workers detailed from general engineering jobs and having no previous experience in aircraft construction. This was a situation that was to reappear later on a much greater scale in aeronautical history, especially in the two world wars.

Capt Herbert F. Wood, who had been appointed manager of Vickers' aviation department on 28 March, 1911, made the first flight from a new private aerodrome established by Vickers at Joyce Green, near Dartford, Kent, and adjacent to the Long Reach Tavern by the River Thames. All Vickers' experimental test flying was made from this site right up to the Vimy Commercial of 1919. However, soon after this first flight in July 1911, the No. 1 monoplane was taken to Brooklands and flown there.

Early in 1912 the Vickers Flying School was established at Brooklands in sheds near the Byfleet banking, where later the final erecting shops of Hawker Aircraft Ltd were situated. After the successful trials of No. 1 monoplane, more were developed from the basic design and gave good service in the Vickers School as instructional machines.

No. 1 was written off in a crash.

Monoplanes Nos. 1-7

Nos 1, 2 and 3

Accommodation: Pilot and passenger

Engine: 60 hp R.E.P.*

Span: 47 ft 6 in

Length: 36 ft 5 in

Wing Area: 290 sq ft

Empty Weight: 1,000 lb

Gross Weight: -

Max Speed

at Ground Level: 56 mph

Range: -

* Changed to 60 hp Vickers-REP on No. 2.

Vickers, Sons and Maxim presented a strong case to the Admiralty on 3 January, 1911, offering to supply one Pelterie-type monoplane for ? 1,500. They stressed the point that the framework of the proposed machine, except the wings, was of steel, with a possible substitution of duralumin in later models. In reply, the Admiralty expressed disinterest, and consequently no order materialised. This approach was of some historical significance, for it presaged the adherence of Vickers to advanced structural philosophies and to metal construction in particular. At that time there were few metal aeroplanes.

The metal-tube airframe was indeed the only outstanding characteristic of the early Vickers monoplanes. Beyond the fact that they were quite strong for the performance then prevailing, they had little else to commend them. They were heavy for the limited power of the standard R.E.P. engine, and attempts were made to improve their power/weight ratio by using Gnome or other engines of greater power. The small margin between flying and stalling speeds made them tricky to fly, especially with the lack of power and the absence of inherent stability, the problems of which had still to be solved at that time.

Those were the pioneering days. The hardy aviators who took to the air in flying machines had perforce to learn the hard way. The Vickers monoplanes, with their steel-tube fuselages, were capable of absorbing rougher usage than contemporary wooden aircraft. With their rigid airframes they were also more easily transported, whereas wooden aircraft were easily damaged in transit.

No. 1 monoplane was part Pelterie (rear fuselage), but the rest was of Vickers construction. Comparing the standard R.E.P with Vickers' first effort, various small modifications appear to have been made. One of the difficulties encountered in building French aircraft under licence was the conversion of metric mensuration into feet and inches, consequently most of the original drawings had to be redrawn to British practice, although it is true that certain constructors, like Bristol and Martin-Handasyde, adopted the metric system throughout their original designs.

The first monoplane was built in the Erith works of Vickers, Sons and Maxim and not at Barrow-in-Furness as was suggested in the proposals to the Admiralty. H. F. Field was works foreman in charge, and he controlled a small number of workers detailed from general engineering jobs and having no previous experience in aircraft construction. This was a situation that was to reappear later on a much greater scale in aeronautical history, especially in the two world wars.

Capt Herbert F. Wood, who had been appointed manager of Vickers' aviation department on 28 March, 1911, made the first flight from a new private aerodrome established by Vickers at Joyce Green, near Dartford, Kent, and adjacent to the Long Reach Tavern by the River Thames. All Vickers' experimental test flying was made from this site right up to the Vimy Commercial of 1919. However, soon after this first flight in July 1911, the No. 1 monoplane was taken to Brooklands and flown there.

Early in 1912 the Vickers Flying School was established at Brooklands in sheds near the Byfleet banking, where later the final erecting shops of Hawker Aircraft Ltd were situated. After the successful trials of No. 1 monoplane, more were developed from the basic design and gave good service in the Vickers School as instructional machines.

No. 1 was written off in a crash.

Monoplanes Nos. 1-7

Nos 1, 2 and 3

Accommodation: Pilot and passenger

Engine: 60 hp R.E.P.*

Span: 47 ft 6 in

Length: 36 ft 5 in

Wing Area: 290 sq ft

Empty Weight: 1,000 lb

Gross Weight: -

Max Speed

at Ground Level: 56 mph

Range: -

* Changed to 60 hp Vickers-REP on No. 2.

Vickers first aeroplane, the No. 1 monoplane, before its first flight at Joyce Green, Dartford, July 1911.

<...>

Among the designs emerging from Vickers' drawing office at that time from which an attempt was made at actual construction was No. 14, known as the Hydravion, presumably because it was intended for operation off land or water. Duralumin floats for the Hydravion were made at Vickers' Dartford works and were tested for corrosion in the adjacent River Darent. According to records held by Vickers House, the whole machine was intended to be made at Dartford, although there is some doubt about this, since the factory there was concerned with explosives and projectiles; most early Vickers aircraft were, in fact, constructed at Erith.

The Hydravion was a large biplane designed on Farman lines, with the 100 hp Gnome engine mounted at the back of the nacelle and driving a pusher propeller, the tail being supported on outrigger booms. A pilot and three passengers were carried. One version was made - the seaplane, according to Vickers House - and as this crashed on an early test flight no photographs have been located. The estimated maximum speed was 51 1/2 mph and the stalling speed 32 mph.

Further developments of the Hydravion included one designated No. 14B. This was projected with two 100 hp Gnome engines, buried in the fuselage, driving tractor propellers through shafts and gearing, with provision for the disengagement of one or other engine, the remaining one still driving both propellers. There was a crew of three, and a 37-mm semi-automatic cannon, with a magazine of 50 shells, was to be mounted in the nose.

Hydravion - One 100 hp Gnome. Accommodation pilot and three passengers. Span 72 ft 8 in; length 43 ft; height 12 ft 2 in; wing area 819 sq ft. Gross weight 2,400 lb. Max speed at ground level 51.5 mph.

Among the designs emerging from Vickers' drawing office at that time from which an attempt was made at actual construction was No. 14, known as the Hydravion, presumably because it was intended for operation off land or water. Duralumin floats for the Hydravion were made at Vickers' Dartford works and were tested for corrosion in the adjacent River Darent. According to records held by Vickers House, the whole machine was intended to be made at Dartford, although there is some doubt about this, since the factory there was concerned with explosives and projectiles; most early Vickers aircraft were, in fact, constructed at Erith.

The Hydravion was a large biplane designed on Farman lines, with the 100 hp Gnome engine mounted at the back of the nacelle and driving a pusher propeller, the tail being supported on outrigger booms. A pilot and three passengers were carried. One version was made - the seaplane, according to Vickers House - and as this crashed on an early test flight no photographs have been located. The estimated maximum speed was 51 1/2 mph and the stalling speed 32 mph.

Further developments of the Hydravion included one designated No. 14B. This was projected with two 100 hp Gnome engines, buried in the fuselage, driving tractor propellers through shafts and gearing, with provision for the disengagement of one or other engine, the remaining one still driving both propellers. There was a crew of three, and a 37-mm semi-automatic cannon, with a magazine of 50 shells, was to be mounted in the nose.

Hydravion - One 100 hp Gnome. Accommodation pilot and three passengers. Span 72 ft 8 in; length 43 ft; height 12 ft 2 in; wing area 819 sq ft. Gross weight 2,400 lb. Max speed at ground level 51.5 mph.

<...>

Early in 1912 the Vickers Flying School was established at Brooklands in sheds near the Byfleet banking, where later the final erecting shops of Hawker Aircraft Ltd were situated. After the successful trials of No. 1 monoplane, more were developed from the basic design and gave good service in the Vickers School as instructional machines.

No. 1 was written off in a crash. No. 2 was sold to Dr (later Sir) Douglas Mawson for the 1912 Australian Antarctic expedition, but crashed on a trial flight in October 1911 at Adelaide; without its wings it was taken with the expedition as a tractor sledge, but the extreme cold solidified the lubricating oil and the engine seized, so the vehicle never served any useful purpose. However, as a pioneering winterisation test, the steel-tube fuselage stood up so well that in recent years, according to report, its remains have been observed at Cape Denison, the Antarctic base of the expedition.

The first five Vickers monoplanes were shoulder-wing aeroplanes carrying a pilot and passenger (or pupil). The fuselages were of steel tubing with welded and bolted tubular end-fittings at the joints, braced with piano wire and covered with fabric. According to Archie Knight, then an instructor at the School, doping was done by any agent that would tighten up the fabric, various concoctions being tried until the advent of acetate dopes as developed by Dr J. E. Ramsbottom of the Royal Aircraft Factory and by various companies in the paint trade.

The undercarriages of the first Vickers monoplanes had dual wooden skids and four wheels sprung by elastic cord on a lever system at the top of the legs. As was common at the time, lateral control was by wing warping. Various engines and propellers were experimented with, but usually Vickers-built R.E.P. five-cylinder fan radials with air cooling were fitted, reputed to be of 60 hp each. Maximum speed attained was around 56 mph and the empty weight about 1,000 lb. No. 5 monoplane was deeper bodied, which gave the crew more protection from the elements, and various small geometrical changes were made between the individual aircraft, including fin and stabiliser configuration.

<...>

In No. 7 monoplane, Vickers' designers reverted to the earlier and larger layouts with tandem seating, a two-skid four-wheel undercarriage and a 100 hp Gnome rotary engine as power unit.

Monoplanes Nos. 1-7

Nos 1, 2 and 3 No. 6 No. 7

Accommodation: Pilot and passenger Pilot and passenger Pilot and passenger

Engine: 60 hp R.E.P.* 70 hp Viale** 100 hp Gnome

Span: 47 ft 6 in 35 ft 34 ft 6 in

Length: 36 ft 5 in - 25 ft

Wing Area: 290 sq ft 220 sq ft 220 sq ft

Empty Weight: 1,000 lb - 730 lb

Gross Weight: - - 1,200 lb

Max Speed

at Ground Level: 56 mph 63 mph 70 mph

Range: - - 350 miles

* Changed to 60 hp Vickers-REP on No. 2.

** Changed to 70 hp Gnome rotary.

Early in 1912 the Vickers Flying School was established at Brooklands in sheds near the Byfleet banking, where later the final erecting shops of Hawker Aircraft Ltd were situated. After the successful trials of No. 1 monoplane, more were developed from the basic design and gave good service in the Vickers School as instructional machines.

No. 1 was written off in a crash. No. 2 was sold to Dr (later Sir) Douglas Mawson for the 1912 Australian Antarctic expedition, but crashed on a trial flight in October 1911 at Adelaide; without its wings it was taken with the expedition as a tractor sledge, but the extreme cold solidified the lubricating oil and the engine seized, so the vehicle never served any useful purpose. However, as a pioneering winterisation test, the steel-tube fuselage stood up so well that in recent years, according to report, its remains have been observed at Cape Denison, the Antarctic base of the expedition.

The first five Vickers monoplanes were shoulder-wing aeroplanes carrying a pilot and passenger (or pupil). The fuselages were of steel tubing with welded and bolted tubular end-fittings at the joints, braced with piano wire and covered with fabric. According to Archie Knight, then an instructor at the School, doping was done by any agent that would tighten up the fabric, various concoctions being tried until the advent of acetate dopes as developed by Dr J. E. Ramsbottom of the Royal Aircraft Factory and by various companies in the paint trade.

The undercarriages of the first Vickers monoplanes had dual wooden skids and four wheels sprung by elastic cord on a lever system at the top of the legs. As was common at the time, lateral control was by wing warping. Various engines and propellers were experimented with, but usually Vickers-built R.E.P. five-cylinder fan radials with air cooling were fitted, reputed to be of 60 hp each. Maximum speed attained was around 56 mph and the empty weight about 1,000 lb. No. 5 monoplane was deeper bodied, which gave the crew more protection from the elements, and various small geometrical changes were made between the individual aircraft, including fin and stabiliser configuration.

<...>

In No. 7 monoplane, Vickers' designers reverted to the earlier and larger layouts with tandem seating, a two-skid four-wheel undercarriage and a 100 hp Gnome rotary engine as power unit.

Monoplanes Nos. 1-7

Nos 1, 2 and 3 No. 6 No. 7

Accommodation: Pilot and passenger Pilot and passenger Pilot and passenger

Engine: 60 hp R.E.P.* 70 hp Viale** 100 hp Gnome

Span: 47 ft 6 in 35 ft 34 ft 6 in

Length: 36 ft 5 in - 25 ft

Wing Area: 290 sq ft 220 sq ft 220 sq ft

Empty Weight: 1,000 lb - 730 lb

Gross Weight: - - 1,200 lb

Max Speed

at Ground Level: 56 mph 63 mph 70 mph

Range: - - 350 miles

* Changed to 60 hp Vickers-REP on No. 2.

** Changed to 70 hp Gnome rotary.

Nos. 3 and 5 monoplanes taxying at Brooklands - No. 5 has the deeper body - No. 4 closely resembled No. 3.

Side view of No. 7 disclosing reversion to the elaborate well-sprung four-wheel undercarriage of Nos. 1 to 5.

Staff of Vickers Flying School at Brooklands, pre-first world war, posing in front of Vickers-REP Monoplane; under propeller boss, R. H. Barnwell, chief instructor, also with cap, Archie Knight, assistant instructor.

<...>

Extensive redesign was introduced in the No. 6 monoplane, built at Erith in June 1912 for the Military Aeroplane Trials Competition, held on Salisbury Plain that year by the War Office. In the No. 6 the wing span was reduced and the undercarriage simplified by the adoption of a two-wheel arrangement with one central skid. Crew seating was side by side, which led to the unofficial designation of the monoplane as the Vickers Sociable. One of the requirements of the Competition was that both members of the crew should be provided with the best possible view of the ground in a forward arc, as the aeroplane was regarded then mainly as an instrument for supporting reconnaissance by cavalry.

No. 6 was powered by a 70 hp Viale seven-cylinder air-cooled radial engine, but this proved too unreliable to give the aeroplane a reasonable chance in the Competition, in which it was flown by L. F. Macdonald, Vickers' pilot. From this type a two-seat biplane was developed and test flown from Joyce Green in December 1912. It was in this aircraft that Macdonald, with his mechanic H. England, crashed in the Thames on 13 January, 1913, both occupants being drowned. The accident was attributed to failure of the 70 hp Gnome rotary engine, which type of engine had previously replaced the Viale in No. 6. No photographs or drawings have survived of this biplane conversion.

<...>

No. 8, the last of the early monoplanes built, reverted to the configuration of No. 6, with a 70 hp or 80 hp Gnome rotary engine as power. It was displayed at the Fourth International Aero Show at Olympia in February 1913. At the next Aero Show, also at Olympia in 1914, Vickers showed a two-seat scout biplane of wooden construction which was obviously a development of the earlier biplane of 1913. Here again few details were released, except that its estimated speed was 100 mph. Presumably this design was dropped in favour of the development of the Vickers Gunbus, which had become a priority for active service.

The following extract is taken from Flight for February 1913, and is a description of the typical construction of the Vickers monoplanes, couched in the terminology of the period. It refers to No. 8 as exhibited in the Aero Show of that year.

'The 80 hp Vickers Two-seater Monoplane - This monoplane is of the same type as the one which, fitted with a 70 hp stationary Viale motor, put up such praiseworthy flights at the time of the Military Aeroplane Competitions in August last. The identical machine shown, driven by a 70 hp Gnome motor, has done upwards of 500 miles in the air at the Vickers private flying ground at Erith, piloted by the late Mr Leslie Macdonald and by their present pilot instructor, Mr Barnwell.

'Its body is an all-steel structure, built lattice-girder fashion, with light tubular longitudinals and tubular cross members. They are assembled by means of welded steel sockets, the joints being afterwards sweated together and pinned. At the front end the four longitudinals meet in a flat upright prate, which serves as one of the mounting plates of the motor. Further support for the motor is provided by a stout flanged plate arranged some little distance behind the front cap. Seats are provided for the pilot and passenger side by side, and there are transparent wind shields fitted in front of them, so that they may suffer no inconvenience from the propeller draught. So carefully has this been carried out that when the machine is flying the occupants can detect scarcely any wind at all. Dual control is fitted. The seats are arranged well forward in the body, so that the occupants have a good clear view over the leading edge of the wings. To still further increase their range of vision, Cellon windows are let into the sides of the body. An interesting fitting in the cockpit is a Clift anti-drift compass, which is mounted over a hole in the floor and by which the machine may be kept on a true course in a side wind.

'The landing chassis is of the central skid and double wheel type. Two Vs of stout steel tube support the body from a long ash skid, which is curved up in front and which is armoured by the application of Duralumin sheeting. Two axles, carrying the rolling wheels, extend on either side of the skid. Landing shocks are absorbed by elastic springs in tension.

'The wings are built about two tubular steel spars cored with wood. Over them the ash ribs are loosely fitted in such a manner that continual warping of the wings does not tend to weaken them in any way. On the under side of the wings three stranded steel cables proceed to each spar, and these take the main lift. In a similar manner the wings are braced from above to a cabane above the pilot's cockpit.

'The tail is formed by the splaying out of the body at the rear to give a fixed stabilising surface behind which are hinged the two lifting flaps. On this monoplane, as distinct from the one that flew in connection with the Military Competitions at Salisbury, a vertical fin is fitted, which precedes an unbalanced directional rudder. A small steel skid protects the tail unit, but it is probable that it very seldom comes into play, for most of the weight of the tail on landing is taken by the backward laminated extension of the main landing skid.

'Fitted with an engine of 70 hp this monoplane shows a speed of 63 mph, and is capable of climbing with the useful load aboard of pilot, passenger, and sufficient fuel for a 3 1/2-hours' flight at the rate of 250 ft per minute. With an 80 hp Gnome motor installed, the machine has been timed to attain and maintain a speed of over 70 mph.'

The early Vickers monoplanes, supported by three Vickers Boxkites of Farman biplane genus, earned their keep despite the hazards of their low-powered engines of dubious reliability and the local physical obstructions to low-altitude flying at Brooklands in the wooded uplands of nearby St George's Hill and Weybridge Heath. There was also the notorious sewage farm, located inside the motor-racing track towards the railway embankment, ready to receive into its sticky mire the unwary flier in trouble on take-off or approach. The monoplanes competed in the popular flying meetings held at Brooklands in pre-1914 days and were always prominent in the handicap races flown on a circuit out to Coxes Lock Mill, near Addlestone, and back. Those halcyon afternoons of real peacetime aeronautics are fast fading from living memory.

Vickers Flying School at Brooklands trained 77 pupils between 1912 and 1914, the second highest of all the civilian schools in the country, and was only bettered by the Bristol School, who also trained most of their pupils at Brooklands. From January to August 1914, when Vickers School closed down because of the outbreak of war, it produced 36 pilots with aviators' certificates - popularly known as flying tickets. This was the record for the country, and the list of Vickers pupils contained names of pilots who achieved fame later on. The work of the pre-1914 civilian flying schools contributed much to the air services by way of trained pilots in the critical early period of the first world war.

Meanwhile Vickers went on with their development of metallised airframes as pioneered by the R.E.P. type monoplanes and with the evolution of a gun-carrying pusher biplane as well as various attempts to find a satisfactory alternative engine to the ubiquitous Gnome.

Monoplanes Nos. 1-7

Nos 1, 2 and 3 No. 6 No. 7

Accommodation: Pilot and passenger Pilot and passenger Pilot and passenger

Engine: 60 hp R.E.P.* 70 hp Viale** 100 hp Gnome

Span: 47 ft 6 in 35 ft 34 ft 6 in

Length: 36 ft 5 in - 25 ft

Wing Area: 290 sq ft 220 sq ft 220 sq ft

Empty Weight: 1,000 lb - 730 lb

Gross Weight: - - 1,200 lb

Max Speed

at Ground Level: 56 mph 63 mph 70 mph

Range: - - 350 miles

* Changed to 60 hp Vickers-REP on No. 2.

** Changed to 70 hp Gnome rotary.

Extensive redesign was introduced in the No. 6 monoplane, built at Erith in June 1912 for the Military Aeroplane Trials Competition, held on Salisbury Plain that year by the War Office. In the No. 6 the wing span was reduced and the undercarriage simplified by the adoption of a two-wheel arrangement with one central skid. Crew seating was side by side, which led to the unofficial designation of the monoplane as the Vickers Sociable. One of the requirements of the Competition was that both members of the crew should be provided with the best possible view of the ground in a forward arc, as the aeroplane was regarded then mainly as an instrument for supporting reconnaissance by cavalry.

No. 6 was powered by a 70 hp Viale seven-cylinder air-cooled radial engine, but this proved too unreliable to give the aeroplane a reasonable chance in the Competition, in which it was flown by L. F. Macdonald, Vickers' pilot. From this type a two-seat biplane was developed and test flown from Joyce Green in December 1912. It was in this aircraft that Macdonald, with his mechanic H. England, crashed in the Thames on 13 January, 1913, both occupants being drowned. The accident was attributed to failure of the 70 hp Gnome rotary engine, which type of engine had previously replaced the Viale in No. 6. No photographs or drawings have survived of this biplane conversion.

<...>

No. 8, the last of the early monoplanes built, reverted to the configuration of No. 6, with a 70 hp or 80 hp Gnome rotary engine as power. It was displayed at the Fourth International Aero Show at Olympia in February 1913. At the next Aero Show, also at Olympia in 1914, Vickers showed a two-seat scout biplane of wooden construction which was obviously a development of the earlier biplane of 1913. Here again few details were released, except that its estimated speed was 100 mph. Presumably this design was dropped in favour of the development of the Vickers Gunbus, which had become a priority for active service.

The following extract is taken from Flight for February 1913, and is a description of the typical construction of the Vickers monoplanes, couched in the terminology of the period. It refers to No. 8 as exhibited in the Aero Show of that year.

'The 80 hp Vickers Two-seater Monoplane - This monoplane is of the same type as the one which, fitted with a 70 hp stationary Viale motor, put up such praiseworthy flights at the time of the Military Aeroplane Competitions in August last. The identical machine shown, driven by a 70 hp Gnome motor, has done upwards of 500 miles in the air at the Vickers private flying ground at Erith, piloted by the late Mr Leslie Macdonald and by their present pilot instructor, Mr Barnwell.

'Its body is an all-steel structure, built lattice-girder fashion, with light tubular longitudinals and tubular cross members. They are assembled by means of welded steel sockets, the joints being afterwards sweated together and pinned. At the front end the four longitudinals meet in a flat upright prate, which serves as one of the mounting plates of the motor. Further support for the motor is provided by a stout flanged plate arranged some little distance behind the front cap. Seats are provided for the pilot and passenger side by side, and there are transparent wind shields fitted in front of them, so that they may suffer no inconvenience from the propeller draught. So carefully has this been carried out that when the machine is flying the occupants can detect scarcely any wind at all. Dual control is fitted. The seats are arranged well forward in the body, so that the occupants have a good clear view over the leading edge of the wings. To still further increase their range of vision, Cellon windows are let into the sides of the body. An interesting fitting in the cockpit is a Clift anti-drift compass, which is mounted over a hole in the floor and by which the machine may be kept on a true course in a side wind.

'The landing chassis is of the central skid and double wheel type. Two Vs of stout steel tube support the body from a long ash skid, which is curved up in front and which is armoured by the application of Duralumin sheeting. Two axles, carrying the rolling wheels, extend on either side of the skid. Landing shocks are absorbed by elastic springs in tension.

'The wings are built about two tubular steel spars cored with wood. Over them the ash ribs are loosely fitted in such a manner that continual warping of the wings does not tend to weaken them in any way. On the under side of the wings three stranded steel cables proceed to each spar, and these take the main lift. In a similar manner the wings are braced from above to a cabane above the pilot's cockpit.

'The tail is formed by the splaying out of the body at the rear to give a fixed stabilising surface behind which are hinged the two lifting flaps. On this monoplane, as distinct from the one that flew in connection with the Military Competitions at Salisbury, a vertical fin is fitted, which precedes an unbalanced directional rudder. A small steel skid protects the tail unit, but it is probable that it very seldom comes into play, for most of the weight of the tail on landing is taken by the backward laminated extension of the main landing skid.

'Fitted with an engine of 70 hp this monoplane shows a speed of 63 mph, and is capable of climbing with the useful load aboard of pilot, passenger, and sufficient fuel for a 3 1/2-hours' flight at the rate of 250 ft per minute. With an 80 hp Gnome motor installed, the machine has been timed to attain and maintain a speed of over 70 mph.'

The early Vickers monoplanes, supported by three Vickers Boxkites of Farman biplane genus, earned their keep despite the hazards of their low-powered engines of dubious reliability and the local physical obstructions to low-altitude flying at Brooklands in the wooded uplands of nearby St George's Hill and Weybridge Heath. There was also the notorious sewage farm, located inside the motor-racing track towards the railway embankment, ready to receive into its sticky mire the unwary flier in trouble on take-off or approach. The monoplanes competed in the popular flying meetings held at Brooklands in pre-1914 days and were always prominent in the handicap races flown on a circuit out to Coxes Lock Mill, near Addlestone, and back. Those halcyon afternoons of real peacetime aeronautics are fast fading from living memory.

Vickers Flying School at Brooklands trained 77 pupils between 1912 and 1914, the second highest of all the civilian schools in the country, and was only bettered by the Bristol School, who also trained most of their pupils at Brooklands. From January to August 1914, when Vickers School closed down because of the outbreak of war, it produced 36 pilots with aviators' certificates - popularly known as flying tickets. This was the record for the country, and the list of Vickers pupils contained names of pilots who achieved fame later on. The work of the pre-1914 civilian flying schools contributed much to the air services by way of trained pilots in the critical early period of the first world war.

Meanwhile Vickers went on with their development of metallised airframes as pioneered by the R.E.P. type monoplanes and with the evolution of a gun-carrying pusher biplane as well as various attempts to find a satisfactory alternative engine to the ubiquitous Gnome.

Monoplanes Nos. 1-7

Nos 1, 2 and 3 No. 6 No. 7

Accommodation: Pilot and passenger Pilot and passenger Pilot and passenger

Engine: 60 hp R.E.P.* 70 hp Viale** 100 hp Gnome

Span: 47 ft 6 in 35 ft 34 ft 6 in

Length: 36 ft 5 in - 25 ft

Wing Area: 290 sq ft 220 sq ft 220 sq ft

Empty Weight: 1,000 lb - 730 lb

Gross Weight: - - 1,200 lb

Max Speed

at Ground Level: 56 mph 63 mph 70 mph

Range: - - 350 miles

* Changed to 60 hp Vickers-REP on No. 2.

** Changed to 70 hp Gnome rotary.

No. 8 monoplane in Vickers Erith works, showing balanced elevators and sociable side-by-side seating first exploited in No. 6.

<...>

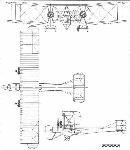

From this 14B and other designs on the same lines it may be concluded that Vickers were thinking in terms of a pusher aeroplane with offensive capability. The linking of their interests in armaments and aviation achieved practical recognition on 19 November, 1912, when a contract was received from the Admiralty for an experimental fighting biplane, armed with a machine-gun.

After many layouts had been considered, the Vickers designers decided that the only practical one was the pusher biplane with the gunner located in the nose. This marks the beginning of the era of Vickers military aircraft, for the design was later classified as E.F.B.l (Experimental Fighting Biplane No. 1) and named Destroyer. It was displayed at the Aero Show at Olympia in February 1913, and created great interest as the first gun-carrying aeroplane designed as such. Unfortunately, it crashed on taking-off on its first test flight at Joyce Green. The E.F.B.1 was powered by a 60/80 hp Wolseley eight-cylinder vee engine with water-cooled exhaust valves and air cooling for cylinders and inlets. The curious scimitar-shaped Vickers-Levasseur propeller was fitted.

The armament was a movable Vickers gun, lightened and modified so as to dispense with the water-cooling jackets of the infantry type, to give an unobstructed field of fire. The airframe was nearly all metal, the nacelle being of steel tubes covered with duralumin. The wings were staggered and employed warping for lateral control, as was then general practice.

Flight records the appearance of the E.F.B.1 at the Aero Show of 1913 as follows:

'The 60-80 hp Vickers Biplane. A very interesting machine, not only for the fact that, hitherto, the Vickers organisation have confined their attentions exclusively to monoplane construction, but for the great amount of thought and care that, it is evident, has been spent on its construction and design. Standing before this biplane, the first feature that arrests the attention is that there is a Vickers automatic gun protruding from the front of the neatly rounded Duralumin covered body. Then even the lay mind can arrive at the principal reason why the propeller has been placed at the rear of the machine - it is designed to have that position mainly in order to give an unobstructed range of fire in front of the biplane.

'The body of the machine, which extends forwards from the main planes, is constructed in a precisely similar manner to that of the Vickers monoplane'

'In its interior sits the passenger and, behind him, the pilot, both sheltered to a great extent from the wind by the neat metallic covering that is fitted over the body. Seated in front, the observer, and he will have to be a gunner too, has a perfectly clear view all around him. The gun before him is arranged to swivel through an angle of 60° in both horizontal and vertical planes, while the ammunition is stored in a box travelling on wires, beneath his seat. When the gun is not in use the ammunition box is in a position just over the centre of pressure of the planes; when it is required to operate it, the box is wound forward on its wire rails and brought within reach of the gunner. As we have remarked, the pilot sits immediately behind him, and he grips a double-handled vertical lever whereby he controls the machine. Still further behind, the motor is mounted, its lugs bolted to the top two members of the fuselage.

'The planes are made on a system which has little difference from that observed in the building of the Vickers monoplane wings. They are "staggered". Contrary to the more usual plan of using piano wire for the bracing of the planes, stranded steel cable is employed in this machine. As a matter of fact, all the bracing throughout is of stranded cable, excepting the body, where stout wire is used. The planes are so designed that in a very little time they may be dismantled, leaving only a centre section that is no wider than the body itself. Close examination of this central section of the top plane will reveal that in its interior there is a small petrol tank from which fuel is fed to the motor by gravity. It is supplied from a main tank in the body, under pressure, and the tubes leading to and from it are neatly tucked away behind the wooden filling pieces that are used to "streamline" the tubular cellule spars. By the way, the machine does not carry an oil tank, for sufficient oil is stored in the base-chamber of the motor to last for a six hours' flight.

'The landing chassis is, at first sight, very much like that of the monoplane. Its flexible suspension, however, will be found to be altogether different. A central hollow skid of ash is joined to the body by two Vs of steel tubing. Two other Vs of tubing extend downwards and outwards from the side of the body, and, in crutches, at their lower extremities, the axles of the landing wheels travel against the tension of the strong rubber springs. Altogether, the chassis is exceptionally light and compact, and, moreover, looks strong enough to bear any ordinary landing strain that it is likely to be subject to. Differing from the monoplane, too, there is no backward extension of the central landing skid. The weight of the tail is carried by a small steel spoon-shaped tail skid, so fixed that it pivots with the rudder and enables the machine to be steered more or less accurately over the ground at slow speeds.

'The tail, level with the top main plane in flight, is attached to the top of the tubular steel tail outriggers. In plan form it is approximately rectangular, and its interior construction is of steel throughout, tubing being used for its outline, while the cambered ribs are of channel section, acetylene-welded in position.'

<...>

Experimental work was carried out with the Gunbus concept, and the E.F.B.6 was a variant flown in 1914 with extended top wing, presumably to obtain more lift for load carrying, but was not proceeded with. Before that, an advanced project following the general configuration of the E.F.B. 1 Destroyer had been designed under the classification E.F.B.4.

E.F.B.1(Destroyer)

Accommodation: Pilot and gunner

Engine: 80 hp Wolseley

Span: 40 ft

Length: 27 ft 6 in

Height: 11 ft 11 in

Wing Area: 385 sq ft

Empty Weight: 1,760 lb

Gross Weight: 2,660 lb

Max Speed: 70 mph at ground level (est.)

Initial Climb: 450ft/min(est.)

Range: 4 1/2 hr

Armament: One Vickers

From this 14B and other designs on the same lines it may be concluded that Vickers were thinking in terms of a pusher aeroplane with offensive capability. The linking of their interests in armaments and aviation achieved practical recognition on 19 November, 1912, when a contract was received from the Admiralty for an experimental fighting biplane, armed with a machine-gun.

After many layouts had been considered, the Vickers designers decided that the only practical one was the pusher biplane with the gunner located in the nose. This marks the beginning of the era of Vickers military aircraft, for the design was later classified as E.F.B.l (Experimental Fighting Biplane No. 1) and named Destroyer. It was displayed at the Aero Show at Olympia in February 1913, and created great interest as the first gun-carrying aeroplane designed as such. Unfortunately, it crashed on taking-off on its first test flight at Joyce Green. The E.F.B.1 was powered by a 60/80 hp Wolseley eight-cylinder vee engine with water-cooled exhaust valves and air cooling for cylinders and inlets. The curious scimitar-shaped Vickers-Levasseur propeller was fitted.

The armament was a movable Vickers gun, lightened and modified so as to dispense with the water-cooling jackets of the infantry type, to give an unobstructed field of fire. The airframe was nearly all metal, the nacelle being of steel tubes covered with duralumin. The wings were staggered and employed warping for lateral control, as was then general practice.

Flight records the appearance of the E.F.B.1 at the Aero Show of 1913 as follows:

'The 60-80 hp Vickers Biplane. A very interesting machine, not only for the fact that, hitherto, the Vickers organisation have confined their attentions exclusively to monoplane construction, but for the great amount of thought and care that, it is evident, has been spent on its construction and design. Standing before this biplane, the first feature that arrests the attention is that there is a Vickers automatic gun protruding from the front of the neatly rounded Duralumin covered body. Then even the lay mind can arrive at the principal reason why the propeller has been placed at the rear of the machine - it is designed to have that position mainly in order to give an unobstructed range of fire in front of the biplane.

'The body of the machine, which extends forwards from the main planes, is constructed in a precisely similar manner to that of the Vickers monoplane'

'In its interior sits the passenger and, behind him, the pilot, both sheltered to a great extent from the wind by the neat metallic covering that is fitted over the body. Seated in front, the observer, and he will have to be a gunner too, has a perfectly clear view all around him. The gun before him is arranged to swivel through an angle of 60° in both horizontal and vertical planes, while the ammunition is stored in a box travelling on wires, beneath his seat. When the gun is not in use the ammunition box is in a position just over the centre of pressure of the planes; when it is required to operate it, the box is wound forward on its wire rails and brought within reach of the gunner. As we have remarked, the pilot sits immediately behind him, and he grips a double-handled vertical lever whereby he controls the machine. Still further behind, the motor is mounted, its lugs bolted to the top two members of the fuselage.

'The planes are made on a system which has little difference from that observed in the building of the Vickers monoplane wings. They are "staggered". Contrary to the more usual plan of using piano wire for the bracing of the planes, stranded steel cable is employed in this machine. As a matter of fact, all the bracing throughout is of stranded cable, excepting the body, where stout wire is used. The planes are so designed that in a very little time they may be dismantled, leaving only a centre section that is no wider than the body itself. Close examination of this central section of the top plane will reveal that in its interior there is a small petrol tank from which fuel is fed to the motor by gravity. It is supplied from a main tank in the body, under pressure, and the tubes leading to and from it are neatly tucked away behind the wooden filling pieces that are used to "streamline" the tubular cellule spars. By the way, the machine does not carry an oil tank, for sufficient oil is stored in the base-chamber of the motor to last for a six hours' flight.

'The landing chassis is, at first sight, very much like that of the monoplane. Its flexible suspension, however, will be found to be altogether different. A central hollow skid of ash is joined to the body by two Vs of steel tubing. Two other Vs of tubing extend downwards and outwards from the side of the body, and, in crutches, at their lower extremities, the axles of the landing wheels travel against the tension of the strong rubber springs. Altogether, the chassis is exceptionally light and compact, and, moreover, looks strong enough to bear any ordinary landing strain that it is likely to be subject to. Differing from the monoplane, too, there is no backward extension of the central landing skid. The weight of the tail is carried by a small steel spoon-shaped tail skid, so fixed that it pivots with the rudder and enables the machine to be steered more or less accurately over the ground at slow speeds.

'The tail, level with the top main plane in flight, is attached to the top of the tubular steel tail outriggers. In plan form it is approximately rectangular, and its interior construction is of steel throughout, tubing being used for its outline, while the cambered ribs are of channel section, acetylene-welded in position.'

<...>

Experimental work was carried out with the Gunbus concept, and the E.F.B.6 was a variant flown in 1914 with extended top wing, presumably to obtain more lift for load carrying, but was not proceeded with. Before that, an advanced project following the general configuration of the E.F.B. 1 Destroyer had been designed under the classification E.F.B.4.

E.F.B.1(Destroyer)

Accommodation: Pilot and gunner

Engine: 80 hp Wolseley

Span: 40 ft

Length: 27 ft 6 in

Height: 11 ft 11 in

Wing Area: 385 sq ft

Empty Weight: 1,760 lb

Gross Weight: 2,660 lb

Max Speed: 70 mph at ground level (est.)

Initial Climb: 450ft/min(est.)

Range: 4 1/2 hr

Armament: One Vickers

Vickers original fighting biplane under construction at Erith works only a few weeks before its public premiere at Olympia; on the right is the Wolseley engine, and in the background are B.E.2s being built.

<...>

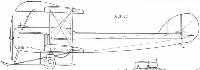

In 1913, Type 18, the E.F.B.2, appeared as an unstaggered biplane with slight overhang on the top wings and with large celluloid windows in the sides of the nacelle. It was flown frequently at Brooklands by Capt Wood and Harold Barnwell during that year, and was powered by a 100 hp Gnome monosoupape rotary engine. E.F.B.3 or No. 18B appeared in December 1913 with the side windows deleted and with ailerons replacing the wing warping. It was shown at the 1914 Olympia Aero Show. An order for six modified No. 18Bs, known as Vickers Type 30s, was placed in December 1913 by the Admiralty. However, before delivery was effected the Type 18B design was still further improved; the contract was taken over by the War Office, and this led to the prototype E.F.B.5, which retained the semicircular tailplane characteristic of the early Type 18.

<...>

Another Vickers design prepared early in 1914 was the S.B.1 school biplane, based on the E.F.B.3 but with the gunner's cockpit replaced with a pupil's position fitted with dual controls. The engine intended for this development was to have been the 100 hp Anzani static radial

E.F.B.2 E.F.B.3

Type 18 Type 18B

Accommodation: Pilot and Pilot and

gunner gunner

Engine: 100 hp Gnome 100 hp Gnome

monosoupape monosoupape

Span: 38 ft 7 in 37 ft 4 in

Length: 29 ft 2 in 27 ft 6 in

Height: 9 ft 7 in 9 ft 9 in

Wing Area: 380 sq ft 385 sq ft

Empty Weight: 1,050 lb 1,050 lb

Gross Weight: 1.760 lb 1.680 lb

Max Speed: 60 mph at 60 mph at

ground level ground level

Service Ceiling:

Initial Climb: 200 ft/min 300 ft/min

Range: 150 miles 300 miles

Armament: One Vickers One Vickers

In 1913, Type 18, the E.F.B.2, appeared as an unstaggered biplane with slight overhang on the top wings and with large celluloid windows in the sides of the nacelle. It was flown frequently at Brooklands by Capt Wood and Harold Barnwell during that year, and was powered by a 100 hp Gnome monosoupape rotary engine. E.F.B.3 or No. 18B appeared in December 1913 with the side windows deleted and with ailerons replacing the wing warping. It was shown at the 1914 Olympia Aero Show. An order for six modified No. 18Bs, known as Vickers Type 30s, was placed in December 1913 by the Admiralty. However, before delivery was effected the Type 18B design was still further improved; the contract was taken over by the War Office, and this led to the prototype E.F.B.5, which retained the semicircular tailplane characteristic of the early Type 18.

<...>

Another Vickers design prepared early in 1914 was the S.B.1 school biplane, based on the E.F.B.3 but with the gunner's cockpit replaced with a pupil's position fitted with dual controls. The engine intended for this development was to have been the 100 hp Anzani static radial

E.F.B.2 E.F.B.3

Type 18 Type 18B

Accommodation: Pilot and Pilot and

gunner gunner

Engine: 100 hp Gnome 100 hp Gnome

monosoupape monosoupape

Span: 38 ft 7 in 37 ft 4 in

Length: 29 ft 2 in 27 ft 6 in

Height: 9 ft 7 in 9 ft 9 in

Wing Area: 380 sq ft 385 sq ft

Empty Weight: 1,050 lb 1,050 lb

Gross Weight: 1.760 lb 1.680 lb

Max Speed: 60 mph at 60 mph at

ground level ground level

Service Ceiling:

Initial Climb: 200 ft/min 300 ft/min

Range: 150 miles 300 miles

Armament: One Vickers One Vickers

E.F.B.3 with metal-sheathed nacelle at Brooklands in 1913 with Harold Barnwell, Vickers' chief pilot, in rear seat.

Experimental version of E.F.B.3 with revised fin and rudder and test instrumentation on starboard aileron strut.

Mr. Barnwell testing his engine before making a flight in the Vlckers gun-carrying biplane at Brooklands.

Mr. Barnwell testing his engine before making a flight in the Vlckers gun-carrying biplane at Brooklands.

The Evolution of the Gunbus

At first the only types of instructional aeroplanes used by Vickers Flying School were the various Vickers monoplanes. Towards the end of 1912, however, three Farman-type biplanes were purchased for pupil training from Vickers' next-door neighbours at Brooklands, Hewlett and Blondeau. With some reconstruction these biplanes became known as Vickers Boxkites and were numbered 19,20 and 21. In December 1913 an equal-span version of the Vickers Boxkite appeared, with a primitive enclosed nacelle to afford the instructor and pupil some protection from the wind. They sat side by side in staggered seats, and the odd-looking structure which resulted from this arrangement led to the aeroplane becoming known as the Pumpkin, bearing the Vickers number 26. A 50 hp Vickers-Boucier static radial engine was fitted, but this was eventually replaced by the 70 hp Gnome.

Vickers School Biplane - Boxkite - One 50 hp Gnome. Span 51 ft 3 in; length 39 ft; wing area 433 sq ft. Gross weight 835 lb.

At first the only types of instructional aeroplanes used by Vickers Flying School were the various Vickers monoplanes. Towards the end of 1912, however, three Farman-type biplanes were purchased for pupil training from Vickers' next-door neighbours at Brooklands, Hewlett and Blondeau. With some reconstruction these biplanes became known as Vickers Boxkites and were numbered 19,20 and 21. In December 1913 an equal-span version of the Vickers Boxkite appeared, with a primitive enclosed nacelle to afford the instructor and pupil some protection from the wind. They sat side by side in staggered seats, and the odd-looking structure which resulted from this arrangement led to the aeroplane becoming known as the Pumpkin, bearing the Vickers number 26. A 50 hp Vickers-Boucier static radial engine was fitted, but this was eventually replaced by the 70 hp Gnome.

Vickers School Biplane - Boxkite - One 50 hp Gnome. Span 51 ft 3 in; length 39 ft; wing area 433 sq ft. Gross weight 835 lb.

<...>

In 1913, Type 18, the E.F.B.2, appeared as an unstaggered biplane with slight overhang on the top wings and with large celluloid windows in the sides of the nacelle. It was flown frequently at Brooklands by Capt Wood and Harold Barnwell during that year, and was powered by a 100 hp Gnome monosoupape rotary engine. E.F.B.3 or No. 18B appeared in December 1913 with the side windows deleted and with ailerons replacing the wing warping. It was shown at the 1914 Olympia Aero Show. An order for six modified No. 18Bs, known as Vickers Type 30s, was placed in December 1913 by the Admiralty. However, before delivery was effected the Type 18B design was still further improved; the contract was taken over by the War Office, and this led to the prototype E.F.B.5, which retained the semicircular tailplane characteristic of the early Type 18. When this latest variant went into production the tailplane was made rectangular, and various nacelle configurations necessitated by different armament mountings were tried before the familiar blunt nose of the standard F.B.5 emerged. At this time the F.B.5 was dubbed the Gunbus.

It will be noted at this time that the prefix E, signifying experimental, was dropped. The first F.B.5 Gunbus was delivered to No. 6 Squadron of the Royal Flying Corps at Netheravon in November 1914. In it the lighter and handier Lewis gun replaced the Vickers gun (One or two F.B.5s used by the Royal Naval Air Service retained the Vickers gun on a pivot mounting), which, however, continued to be used in the air war as a fixed weapon with the whole aeroplane aimed at the target. Before this happened, however, a satisfactory means had to be invented to enable a fixed gun to fire through a revolving tractor propeller. One of the earliest of such devices was, in fact, the Vickers-Challenger interruptor gear. By this time aviation had become an arm of the Services, tentatively at first for reconnaissance and later for air attack.

The Crayford works took over the production of Vickers aircraft in late 1914, and the first F.B.5s were delivered from there. Three aircraft comprised the initial delivery to Netheravon, but two were returned to Joyce Green to create the nucleus of the Air Defence of London. The first recorded use of a Gunbus in action was on Christmas Day 1914, when 2nd Lt M. R. Chidson with Corporal Martin as gunner took-off from Joyce Green to attack a German Taube monoplane and, according to circumstantial evidence, destroyed it. The type went to the Western Front, and the first F.B.5 to arrive there was Chidson's, he having been posted to No. 2 Squadron in France on 7 February, 1915.

In November 1915, 2nd Lt G. S. M. Insall was awarded the Victoria Cross for gallantry displayed after forcing down a German Aviatik reconnaissance machine while flying a Vickers Gunbus. Compelled by ground fire to land near the front lines of the Allies, Insall repaired the damage to his aeroplane during the night and returned next morning to his squadron. In spite of these and other successes, the Gunbus suffered in company with other Allied aircraft from the unreliability of the rotary engine, largely because servicing and maintenance in the early days were not of the high standard reached later.

Experimental work was carried out with the Gunbus concept, and the E.F.B.6 was a variant flown in 1914 with extended top wing, presumably to obtain more lift for load carrying, but was not proceeded with. Before that, an advanced project following the general configuration of the E.F.B. 1 Destroyer had been designed under the classification E.F.B.4.

The F.B.5A was fitted with the Le Rhone or Clerget engine of 110 hp, and at least four were constructed with armour-plated nacelles. Two F.B.5s were fitted with the experimental Smith static radial air-cooled engine, nominally of 140 hp, while another was equipped with floats for operation off water but before this could be tried was reconverted to standard form and flown back to France.

<...>

A replica F.B.5 Gunbus was made by the Vintage Aircraft and Flying Association (Brooklands) in 1966 to celebrate the centenary of the Royal Aeronautical Society. It was fitted with a 100 hp Gnome monosoupape rotary engine rebuilt from two surviving examples found in RAF redundant stores. This aeroplane flew faultlessly at the first attempt, piloted by D. G. Addicott, a Vickers test pilot. Despite its low power, the replica disclosed good handling qualities and is an existing testimony to the excellence of the design for the requirement of its day, which was to provide a steady gun platform for air offence.

F.B.5 (Gunbus)

Accommodation: Pilot and gunner

Engine: 100 hp Gnome monosoupape

Span: 36 ft 6 in

Length: 27 ft 2 in

Height: 11 ft

Wing Area: 382 sq ft

Empty Weight: 1,220 lb

Gross Weight: 2,050 lb

Max Speed: 70 mph at 5,000 ft

Service Ceiling:9,000 ft

Climb to: 5,000ft in 16min

Range: 250 miles

Armament: One Lewis

In 1913, Type 18, the E.F.B.2, appeared as an unstaggered biplane with slight overhang on the top wings and with large celluloid windows in the sides of the nacelle. It was flown frequently at Brooklands by Capt Wood and Harold Barnwell during that year, and was powered by a 100 hp Gnome monosoupape rotary engine. E.F.B.3 or No. 18B appeared in December 1913 with the side windows deleted and with ailerons replacing the wing warping. It was shown at the 1914 Olympia Aero Show. An order for six modified No. 18Bs, known as Vickers Type 30s, was placed in December 1913 by the Admiralty. However, before delivery was effected the Type 18B design was still further improved; the contract was taken over by the War Office, and this led to the prototype E.F.B.5, which retained the semicircular tailplane characteristic of the early Type 18. When this latest variant went into production the tailplane was made rectangular, and various nacelle configurations necessitated by different armament mountings were tried before the familiar blunt nose of the standard F.B.5 emerged. At this time the F.B.5 was dubbed the Gunbus.

It will be noted at this time that the prefix E, signifying experimental, was dropped. The first F.B.5 Gunbus was delivered to No. 6 Squadron of the Royal Flying Corps at Netheravon in November 1914. In it the lighter and handier Lewis gun replaced the Vickers gun (One or two F.B.5s used by the Royal Naval Air Service retained the Vickers gun on a pivot mounting), which, however, continued to be used in the air war as a fixed weapon with the whole aeroplane aimed at the target. Before this happened, however, a satisfactory means had to be invented to enable a fixed gun to fire through a revolving tractor propeller. One of the earliest of such devices was, in fact, the Vickers-Challenger interruptor gear. By this time aviation had become an arm of the Services, tentatively at first for reconnaissance and later for air attack.

The Crayford works took over the production of Vickers aircraft in late 1914, and the first F.B.5s were delivered from there. Three aircraft comprised the initial delivery to Netheravon, but two were returned to Joyce Green to create the nucleus of the Air Defence of London. The first recorded use of a Gunbus in action was on Christmas Day 1914, when 2nd Lt M. R. Chidson with Corporal Martin as gunner took-off from Joyce Green to attack a German Taube monoplane and, according to circumstantial evidence, destroyed it. The type went to the Western Front, and the first F.B.5 to arrive there was Chidson's, he having been posted to No. 2 Squadron in France on 7 February, 1915.

In November 1915, 2nd Lt G. S. M. Insall was awarded the Victoria Cross for gallantry displayed after forcing down a German Aviatik reconnaissance machine while flying a Vickers Gunbus. Compelled by ground fire to land near the front lines of the Allies, Insall repaired the damage to his aeroplane during the night and returned next morning to his squadron. In spite of these and other successes, the Gunbus suffered in company with other Allied aircraft from the unreliability of the rotary engine, largely because servicing and maintenance in the early days were not of the high standard reached later.

Experimental work was carried out with the Gunbus concept, and the E.F.B.6 was a variant flown in 1914 with extended top wing, presumably to obtain more lift for load carrying, but was not proceeded with. Before that, an advanced project following the general configuration of the E.F.B. 1 Destroyer had been designed under the classification E.F.B.4.

The F.B.5A was fitted with the Le Rhone or Clerget engine of 110 hp, and at least four were constructed with armour-plated nacelles. Two F.B.5s were fitted with the experimental Smith static radial air-cooled engine, nominally of 140 hp, while another was equipped with floats for operation off water but before this could be tried was reconverted to standard form and flown back to France.

<...>

A replica F.B.5 Gunbus was made by the Vintage Aircraft and Flying Association (Brooklands) in 1966 to celebrate the centenary of the Royal Aeronautical Society. It was fitted with a 100 hp Gnome monosoupape rotary engine rebuilt from two surviving examples found in RAF redundant stores. This aeroplane flew faultlessly at the first attempt, piloted by D. G. Addicott, a Vickers test pilot. Despite its low power, the replica disclosed good handling qualities and is an existing testimony to the excellence of the design for the requirement of its day, which was to provide a steady gun platform for air offence.

F.B.5 (Gunbus)

Accommodation: Pilot and gunner

Engine: 100 hp Gnome monosoupape

Span: 36 ft 6 in

Length: 27 ft 2 in

Height: 11 ft

Wing Area: 382 sq ft

Empty Weight: 1,220 lb

Gross Weight: 2,050 lb

Max Speed: 70 mph at 5,000 ft

Service Ceiling:9,000 ft

Climb to: 5,000ft in 16min

Range: 250 miles

Armament: One Lewis

E.F.B.5 prototype in service under serial 664 with gun pylon added - sometimes described as F.B.4, although the E.F.B.4 was a project development of E.F.B.1.

First production F.B.5 at Brooklands for trials before delivery. The two seat Vickers FB 5, popularly known as the 'Gun Bus', had its origins in a visionary 1912 Admiralty requirement for a so-called fighting aeroplane, armed with a machine gun. The contract for this machine was placed with Vickers on 19 November 1912, where its development became somewhat protracted, the first production FB 5s, by now ordered for both the RFC and the RNAS, not reaching No 6 Squadron, RFC until November 1914, while the handful of RNAS FB 5s did not reach the front until early 1915. Powered by a somewhat unreliable 100hp Gnome Monosoupape, the FB 5's top level speed was 70mph at 5.000 feet, while the time taken to reach that altitude was 16 minutes. Excluding prototypes, around 136 FB 5s are known to have been produced by Vickers in Britain and Darracq in France.

One of the first batch of F.B.5s for the Royal Flying Corps presented by the City of Bombay to H.M. Government in 1914; this Gunbus was the pattern for the replica built in 1966.

The replica Gunbus built by the Vintage Aircraft and Flying Association (Brooklands) on an engine test flight piloted by 'Dizzy' Addicott with Alan Blower as observer.

<...>

Experimental work was carried out with the Gunbus concept, and the E.F.B.6 was a variant flown in 1914 with extended top wing, presumably to obtain more lift for load carrying, but was not proceeded with.

Experimental work was carried out with the Gunbus concept, and the E.F.B.6 was a variant flown in 1914 with extended top wing, presumably to obtain more lift for load carrying, but was not proceeded with.

<...>

A side issue of some interest to the Gunbus story was the request from the German Government, made early in 1914, for details of Vickers fighting biplanes. Apparently there was nothing sinister in this approach, which was similar to that made to the Sopwith and other British aircraft companies; Britain was never seriously regarded as a potential enemy by Germany even at that late date, and its interest was doubtless genuine.

In offering the Type 18 series to the Germans, Vickers said, 'What we have at the present moment is a type of machine which is not existent in the German Army, in fact not in Europe except in England. This machine is intended for offensive action in the air against other planes and dirigibles, consequently it is not equipped with a bomb-dropping apparatus. The light Maxim gun mounted in the nose is so placed as to enable the gunner to have a free field of fire against other aeroplanes. We can carry Pilot, Observer, Barograph, Gun, 300 rounds of ammunition, and fuel for 4 hours. Loaded with this, it can easily attain a height of 800 metres in 15 minutes. The speed of the machine is 105 km/hr instead of 90 required by the German Authorities. We can reduce to 70 km/hr if required.'

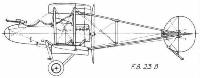

This design was not accepted, but in response to a further request from the German Government, three advanced designs for aircraft, called G.F.B.1, G.F.B.2 and G.F.B.3 (German Fighting Biplanes), which resembled in many respects the Hydravion projects, were prepared during the early months of 1914. Details of only the last two are now available; these were alike, except that the G.F.B.2 had two 100 hp Gnome monosoupape engines while the G.F.B.3 had two 140/165 hp Austro-Daimlers. The engines were mounted side by side in the fuselage, driving two tractor propellers, and clutches could cut out one or both.

These large three-seat biplane designs had provision for a 37-mm one-pounder gun mounted in the nose, and the pilot and observer were seated in the fuselage behind the engines. Specified equipment included wireless and 50 rounds of ammunition. The upper wings were of greater span than the lower, and for hangarage purposes the outer sections of the upper wings could be lowered, thus reducing the span from 72 to 59 ft. The G.F.B.3 was designed for a maximum speed of 72 mph with an endurance of five hours, and the all-up weight was estimated at 4,000 lb. The outbreak of war in August 1914 prevented construction of these interesting designs.

A side issue of some interest to the Gunbus story was the request from the German Government, made early in 1914, for details of Vickers fighting biplanes. Apparently there was nothing sinister in this approach, which was similar to that made to the Sopwith and other British aircraft companies; Britain was never seriously regarded as a potential enemy by Germany even at that late date, and its interest was doubtless genuine.

In offering the Type 18 series to the Germans, Vickers said, 'What we have at the present moment is a type of machine which is not existent in the German Army, in fact not in Europe except in England. This machine is intended for offensive action in the air against other planes and dirigibles, consequently it is not equipped with a bomb-dropping apparatus. The light Maxim gun mounted in the nose is so placed as to enable the gunner to have a free field of fire against other aeroplanes. We can carry Pilot, Observer, Barograph, Gun, 300 rounds of ammunition, and fuel for 4 hours. Loaded with this, it can easily attain a height of 800 metres in 15 minutes. The speed of the machine is 105 km/hr instead of 90 required by the German Authorities. We can reduce to 70 km/hr if required.'

This design was not accepted, but in response to a further request from the German Government, three advanced designs for aircraft, called G.F.B.1, G.F.B.2 and G.F.B.3 (German Fighting Biplanes), which resembled in many respects the Hydravion projects, were prepared during the early months of 1914. Details of only the last two are now available; these were alike, except that the G.F.B.2 had two 100 hp Gnome monosoupape engines while the G.F.B.3 had two 140/165 hp Austro-Daimlers. The engines were mounted side by side in the fuselage, driving two tractor propellers, and clutches could cut out one or both.

These large three-seat biplane designs had provision for a 37-mm one-pounder gun mounted in the nose, and the pilot and observer were seated in the fuselage behind the engines. Specified equipment included wireless and 50 rounds of ammunition. The upper wings were of greater span than the lower, and for hangarage purposes the outer sections of the upper wings could be lowered, thus reducing the span from 72 to 59 ft. The G.F.B.3 was designed for a maximum speed of 72 mph with an endurance of five hours, and the all-up weight was estimated at 4,000 lb. The outbreak of war in August 1914 prevented construction of these interesting designs.

Scout Biplane - One 100 hp Gnome monosoupape. Accommodation pilot and passenger. Span 25 ft; length 20 ft 7 in; wing area 270 sq ft. Empty weight 600 lb; gross weight 1,200 lb. Max speed at ground level 100 mph; range 350 miles.

Shortly after the start of the first world war Vickers engaged Howard Flanders to design a new twin-engined fighting aeroplane to carry a Vickers one-pounder gun. Classified as the E.F.B.7, it was powered with wing-mounted Gnome monosoupape engines, and the pilot was seated behind the wings and the gunner in the nose. It flew some time in August 1915, and thus vied with the comparable French Caudron and other designs for the claim of being the first twin-engined military aircraft to fly successfully.

However, in the E.F.B.7 the distance separating the two-man crew was found unacceptable in practice; in the variant, the E.F.B.7A, the pilot was brought forward of the wings, just behind the gunner. An attempt to re-engine this Flanders-designed machine with two 80 hp air-cooled Renaults (because of the shortage of Gnomes) was unsuccessful, as the loss of some 40 hp meant a serious drop in performance. In consequence, a contract for 11 F.B.7 aircraft being built by Darracq and Company (1905) Ltd of Townmead Road, Fulham, was cancelled.

The E.F.B.8, which appeared in November 1915, powered by two Gnome monosoupapes, was smaller than its predecessor and carried only a single light Lewis gun, which could be accommodated equally well in single-engined types. This redesign was entrusted to Pierson, who stored the knowledge gained and revived it when a new twin-engined bomber was called for from Vickers by the Air Board in 1917.

E.F.B.7 E.F.B.8

Accommodation: Pilot and gunner Pilot and gunner

Engines: Two 100 hp Two 100 hp

Gnome monosoupape Gnome monosoupape

Span: 59 ft 6 in upper, 38 ft 4 in upper

37 ft 6 in lower 36 ft 8 in lower

Length: 36 ft 28 ft 2 in

Height: - 9 ft 10 in

Wing Area: 640 sq ft 468 sq ft

Empty Weight: 2,136 lb 1,840 lb

Gross Weight: 3,196 lb 2,700 lb

Max Speed at 5,000 ft: 75 mph 98 mph

Climb to 5,000 ft: 18 min 10 min

Ceiling: 9,000 ft 14,000 ft

Endurance: 2 1/2 hr 3 hr

Armament: One 1-pdr Vickers gun One Lewis gun

in nose in nose

However, in the E.F.B.7 the distance separating the two-man crew was found unacceptable in practice; in the variant, the E.F.B.7A, the pilot was brought forward of the wings, just behind the gunner. An attempt to re-engine this Flanders-designed machine with two 80 hp air-cooled Renaults (because of the shortage of Gnomes) was unsuccessful, as the loss of some 40 hp meant a serious drop in performance. In consequence, a contract for 11 F.B.7 aircraft being built by Darracq and Company (1905) Ltd of Townmead Road, Fulham, was cancelled.

The E.F.B.8, which appeared in November 1915, powered by two Gnome monosoupapes, was smaller than its predecessor and carried only a single light Lewis gun, which could be accommodated equally well in single-engined types. This redesign was entrusted to Pierson, who stored the knowledge gained and revived it when a new twin-engined bomber was called for from Vickers by the Air Board in 1917.

E.F.B.7 E.F.B.8

Accommodation: Pilot and gunner Pilot and gunner

Engines: Two 100 hp Two 100 hp

Gnome monosoupape Gnome monosoupape

Span: 59 ft 6 in upper, 38 ft 4 in upper

37 ft 6 in lower 36 ft 8 in lower

Length: 36 ft 28 ft 2 in

Height: - 9 ft 10 in

Wing Area: 640 sq ft 468 sq ft

Empty Weight: 2,136 lb 1,840 lb

Gross Weight: 3,196 lb 2,700 lb

Max Speed at 5,000 ft: 75 mph 98 mph

Climb to 5,000 ft: 18 min 10 min

Ceiling: 9,000 ft 14,000 ft

Endurance: 2 1/2 hr 3 hr

Armament: One 1-pdr Vickers gun One Lewis gun

in nose in nose

Vickers Designs 1914-18

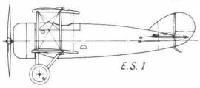

When war broke out in 1914 there was a serious shortage of British military aircraft compared with those possessed by France and Germany, and various aeronautical experimenters made efforts to remedy this deficiency. Among these private-venture attempts was one by Harold Barnwell, who had been appointed chief test pilot by Vickers after the closing of their flying school at Brooklands. In spare moments from testing production Gunbuses he took upon himself the task of designing and constructing under cover a small high-speed scout, fitted with a Gnome engine spirited out of Vickers' Erith stores.

Barnwell's creation was a tubby little machine with a circular-section streamlined fuselage and stubby unstaggered wings of small span. It soon acquired the name of the Barnwell Bullet. On its first flight early in 1915, in the hands of its designer, it was found to have insufficient control, particularly on the elevators. On landing, its undercarriage collapsed, and the Bullet stood on its nose. This mishap must have revealed its existence to Vickers' management, for R. K. Pierson, a young graduate apprentice then in the drawing office who had also learned to fly at Vickers' Flying School, was given the task of redesigning the Bullet into an experimental scout with the designation of E.S.1, powered with a Gnome monosoupape engine.