Книги

Putnam

C.Barnes

Bristol Aircraft since 1910

106

C.Barnes - Bristol Aircraft since 1910 /Putnam/

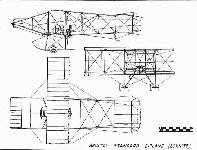

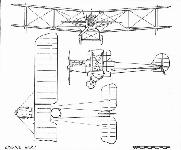

The Bristol Boxkite

The Bristol biplane of 1910, familiarly but inaccurately dubbed 'the Boxkite', was an unashamed copy of the Henri Farman, using the same dimensions and scantlings, but introducing the more refined metal fittings, such as steel clips and cast aluminium strut sockets, of Zodiac practice. The quality of French-built Farmans was somewhat variable, but the Bristol biplane, though similar in general appearance, was equivalent to or better than the best that France had produced at that time. Indeed when the solicitors for Farman Freres proposed to sue the 'Bristol' Directors for infringement of patents, the Directors immediately entered a defence claiming substantial improvements, and no court proceedings ensued. The first two Boxkites were constructed at Filton to drawings made by George Challenger in June 1910, immediately after the abandonment of the Zodiac. They differed from all later Boxkites in having rear elevators with straight trailing edges and in having two, instead of one, intermediate vertical struts between each pair of upper and lower front booms. No. 7 was at first fitted with a 50 h.p. Gregoire four-cylinder engine and No.8 with a 50 h.p. eight-cylinder E.N.V., both being watercooled. A further point of difference was that No.8 had double-surfaced wings whereas No. 7 had a single fabric covering with pockets enclosing the ribs; the latter was standard Farman practice and was adopted on all later Bristol Boxkites, mainly to save weight. The Gregoire was unreliable and deficient in power, so Emile Stern's success in obtaining one of the first 50 h.p. Gnome rotaries released for export was particularly valuable. Fitted with this engine, No.7 was taken to Larkhill on 29 July 1910, assembled overnight, and flown the next day to a height of 150 ft. at the first attempt by Edmond, to the astonishment of beholders who had taken up prone positions on the ground in order to detect the first glimmer of daylight between the grass and the wheels.

With the efficiency of the design thus spectacularly confirmed, the two Boxkites were crated and dispatched to Lanark, where a six-day aviation meeting opened on 6 August at the race course. Only No.7 took part in any events, which Edmond completed without incident but with only one award, the second prize for the slowest lap, in which his speed was 45 m.p.h. Meanwhile, more Boxkites were laid down at Filton and Nos. 7 and 8 were allocated as initial equipment of the flying schools at Brooklands and Larkhill, respectively; No.8 retained the Lanark competition number 19 on its rudders for some months. As new aircraft were completed, the schools' complement was doubled, Larkhill receiving No. 9 in September and Brooklands No. 11 in November. Captain Dickson flew No.9 in the army autumn manceuvres in September and Lt. Loraine accompanied him on No.8, which had been equipped with a Thorne-Baker wireless transmitter. Nos. 10 and 12 were specially prepared for the Missions to Australia and India, respectively, the latter being the first to have upper wing extensions. The next two, Nos. 12A and 14 (No. 13 being unacceptable to any pilot of that date!) were flown from Durdham Down in the first public demonstration of the Company's activities; when these ended No. 12A was lent to Oscar Morison, who flew it in various demonstrations and competitions; No. 14 went on to Larkhill as a school aircraft, releasing No.9 for duty as the spare for the Indian Mission. Two further new Boxkites, Nos. 15 and 16, went to Brooklands, whence No. 11 was brought back for overhaul and packing as the spare for the Australian Mission. No. 16 was fitted with extended wings and a 60 h.p. E.N.V. water-cooled engine; the latter made it technically an 'All British' aeroplane for competition purposes, and thus it became the mount on which Howard Pixton, with Charles Briginshaw as mechanic, won the Manville Prize of ?500 for the highest aggregate time flown on nine specified days in 1911.

Both the Australian and Indian Missions arrived at their destinations in December, and on 6 January 1911 Jullerot demonstrated No. 12 before a Vice-regal party and a large crowd of spectators at the Calcutta Maidan. Invited to participate in the Deccan cavalry manceuvres, Jul1erot made several flights from Aurangabad, from 16 January onwards, carrying Capt. Sefton Brancker as army observer, and later took part in the Northern Manceuvres at Karghpur. Here conditions were very severe and both No. 12 and No.9 came to grief on the rock-strewn terrain, with a ground temperature of 100°F, but many flights were made and repairs kept pace with damage. When all the spares were used up, No. 9 was cannibalised to keep No. 12 flying and the latter survived to return to Larkhill as a school machine, being flown by many notable pupils, including Robert Smith-Barry, who was charged ?15 in October 1911 for repairs after a heavy landing on it.

In Australia, Hammond began flying on No. 10 at Perth late in December, going on to Melbourne, where 32 flights, many with passengers, were made. The Mission then moved to Sydney, whence Hammond went home to New Zealand leaving Macdonald as sole pilot. By 19 May 1911,72 flights totaling 765 miles had been completed without having had to replace a single bqlt or wire on No. 10. The spare machine, No. 11, still in its packing case, was sold to W. E. Hart, of Penrith, N.S.W., together with the unused spares, when the Mission left to return to England. Although this was the only direct sale made by both Missions, the Boxkite had by now begun to attract foreign buyers. The outcome of negotiations with the Russian Attache in Paris, William Rebikoff, was the first Government contract in the world for British aeroplanes, signed on 15 November 1910 for the supply of eight improved Boxkites having enlarged tanks and three rudders, which were called the Military model. The first three of these, Nos. 17, 18 and 19, were at first flown with 50 h.p. Gnomes, although 70 h.p. Gnomes had been specified for delivery in April 1911, when they were to become available. Meanwhile, No. 16, brought up to Military standard with three rudders but retaining its E.N.V. engine, was lent to Claude Grahame-White for an attempt to win the prize of ?4,000 offered by Baron de Forest for a flight from England to the most distant point along the Continental coast. No. 16 was damaged by a storm while waiting to take off from Swingate Downs, Dover, but was repaired in time for a second attempt on 18 December 1910, when Grahame-White was caught by a down-gust at the cliff-edge and crashed. No. 17, which was at Brooklands, was at once dispatched as a replacement, but caught fire soon after arrival at Dover, and Grahame-White then retired from the contest on his doctor's advice. Lt. Loraine had also entered the competition, flying No.8, but this too was badly damaged in the storm; No. 16 was eventually rebuilt and flown again at Brooklands. In April Nos. 18 and 19 were shipped to St. Petersburg together with Nos. 20 to 25 inclusive, after installation of 70 h.p. Gnome engines, but were later exchanged for two new machines, Nos. 26 and 30, in July 1911. No. 18 was damaged in transit back to Filton and written off, but No. 19 survived at Larkhill until May 1913, when it was dismantled and reconstructed as No. 134, which in turn was crashed at the Brooklands school in November 1913.

Still no contract came from the British War Office, and the next two Boxkites, Nos. 27 and 28, were standard school machines bought by the Belgian pilot Joseph Christiaens, who chose them for his flying displays in Malaya and South Africa. He took delivery of them on 19 January 1911, and after successful flights at Singapore on No. 27 went on to Cape Town and Pretoria, where he sold No. 28 to John Weston, who became the Company's agent in South Africa. A further school machine, No. 29, was sent to Brooklands in February 1911 and then two special exhibition models were built, having 70 h.p. Gnome engines, enclosed nacelles and increased span. The first, No. 31, was exhibited at Olympia in March 1911, and the second, No. 32, at St. Petersburg in April. The latter was inspected by the Czar and so impressed his military advisers that a gold medal and certificate of merit were awarded to the Company; and No. 32 was purchased in addition to the eight already ordered.

The War Office at last placed a contract, on 14 March 1911, for four Military Boxkites with 50 h.p. Gnomes as described in a specification submitted on 20 October 1910. Meanwhile Oscar Morison had damaged No. l2A while giving exhibition flights at Brighton, and No. 34 was taken from the production line to replace it. The first two War Office machines, Nos. 37 and 38, were delivered at Larkhill on 18 and 25 May, respectively, but then the War Office asked for the other two to be supplied with 60 h.p. Renault engines for comparison. This required a redesign of the engine mounting and carlingue, which resulted in a substantial nacelle structure in front of the pilot. No. 39, thus modified, was delivered at Larkhill on 9 July, by which time four more had been ordered, two with 50 h.p. Gnomes and two as spare airframes without engines. The latter (Nos. 40 and 41) were dispatched on 31 July, the second Renault machine (No. 42) on 2 August and the remaining Gnome machines (Nos. 48 and 49) during the subsequent fortnight. Nos. 43 and 47 were standard school Boxkites, the first being supplied to Larkhill while the second was taken to France by Versepuy when he returned in September 1911; he demonstrated it at Issy-les-Moulineaux and Vichy, where his mechanic was George Little; subsequently he sold it to the Bulgarian Government, to be flown by Lt. Loultchieff.

By this time the Boxkite production line had become well established and continued, mainly to supply wastage at the various schools, until 1914. In the standard models the wing extensions were retained but the third rudder was deleted. Strict interchangeability of components was maintained, and many later school machines incorporated serviceable parts from earlier aircraft. The 50 h.p. Gnome remained as the standard power unit except for No. 60 and No. 139, which had 70 h.p. Gnomes. The latter machine was supplied to R.N.A.S. Eastchurch in April 1913, receiving Naval serial no. 35, and was standard except for the engine, but No. 60 was similar to Nos. 31 and 32 with an enclosed nacelle, also incorporating longitudinal tanks and a push-pull handwheel control instead of the simple control-stick; this was demonstrated at Cuatros Vientos by Busteed in November 1911 and purchased soon afterwards by the Spanish Government, who ordered a similar spare airframe (No. 79) in which they fitted one of their own 70 h.p. Gnomes. Including rebuilds which received new sequence numbers, the total number of Boxkites built was 76, all at Filton except for the final six (Nos. 394-399), which were the first aeroplanes constructed at the Tramways Company's Brislington works. Although underpowered and out-dated at the end of their career, they survived mishandling often to the point of demolition, but the pupils emerged more or less unscathed and the mechanics performed daily miracles of reconstruction, so that school machines were constantly reappearing Phoenix-like from their own wreckage. Apart from the nine exported to Russia, three were sold to South Africa, two each to Australia, Germany and Spain, and one each to Bulgaria, India, Rumania and Sweden.

In addition to the Boxkite proper, there were two variants, both for competition work. The first of these was No. 44, which had wings of much reduced span and a small single-seat nacelle. This was for Maurice Tetard in the Circuit de l'Europe (racing no. 3) and was first flown on 30 May 1911; in the race it developed engine trouble and Tetard retired at Rheims, half-way through the first stage. The other was No. 69 and was a redesign in November 1911 by Gabriel Voisin using standard wings, but with the gap reduced and the front elevator and booms deleted; a single large tail plane and a single rudder replaced the normal biplane tail unit. It was sent to Larkhill for tests in February 1912. No photograph of this machine has survived and it was apparently soon rebuilt as a standard school Boxkite, in which form it was crashed at Larkhill by Major Forman on 3 November 1912.

SPECIFICATION AND DATA

Type: Bristol Biplane (Boxkite)

Manufacturers: The British & Colonial Aeroplane Co. Ltd., Filton and Brislington, Bristol

Power Plant:

One 50 hp Gregoire

One 50/60 hp E.N.V.

One 50 hp Gnome

One 60 hp Renault

One 70 hp Gnome

Model Standard Extended Racer Voisin

(Military) No. 44 No. 69

Span 34 ft 6 in 47 ft 8 in or 35 ft 32 ft 8 in

46 ft 6 in

Length 38 ft 6 in 38 ft 6 in 38 ft 30 ft 9 in

Height 11 ft 10 in 11 ft 10 in 11 ft 10 in 9 ft 6 in

Wing Area 457 sq ft 517 sq ft 350 sq ft 420 sq ft

Empty Weight 800 lb 900 lb 800 lb 800 lb

All-up Weight 1,050 lb 1,150 lb 1,000 lb 1,000 lb

Speed 40 mph 40 mph 50 mph 50 mph

Accommodation 2 2 1 2

Production 15 61 1 1

Sequence Nos. 7-11 12A 12 15-32 44 69

14 34 43 37-42 47

49 55 62 48 60 67

63 65 66 79 93 99

119 124-129

133-139 179

180 203

204 207

222 226

231 347

394-399

The Bristol biplane of 1910, familiarly but inaccurately dubbed 'the Boxkite', was an unashamed copy of the Henri Farman, using the same dimensions and scantlings, but introducing the more refined metal fittings, such as steel clips and cast aluminium strut sockets, of Zodiac practice. The quality of French-built Farmans was somewhat variable, but the Bristol biplane, though similar in general appearance, was equivalent to or better than the best that France had produced at that time. Indeed when the solicitors for Farman Freres proposed to sue the 'Bristol' Directors for infringement of patents, the Directors immediately entered a defence claiming substantial improvements, and no court proceedings ensued. The first two Boxkites were constructed at Filton to drawings made by George Challenger in June 1910, immediately after the abandonment of the Zodiac. They differed from all later Boxkites in having rear elevators with straight trailing edges and in having two, instead of one, intermediate vertical struts between each pair of upper and lower front booms. No. 7 was at first fitted with a 50 h.p. Gregoire four-cylinder engine and No.8 with a 50 h.p. eight-cylinder E.N.V., both being watercooled. A further point of difference was that No.8 had double-surfaced wings whereas No. 7 had a single fabric covering with pockets enclosing the ribs; the latter was standard Farman practice and was adopted on all later Bristol Boxkites, mainly to save weight. The Gregoire was unreliable and deficient in power, so Emile Stern's success in obtaining one of the first 50 h.p. Gnome rotaries released for export was particularly valuable. Fitted with this engine, No.7 was taken to Larkhill on 29 July 1910, assembled overnight, and flown the next day to a height of 150 ft. at the first attempt by Edmond, to the astonishment of beholders who had taken up prone positions on the ground in order to detect the first glimmer of daylight between the grass and the wheels.

With the efficiency of the design thus spectacularly confirmed, the two Boxkites were crated and dispatched to Lanark, where a six-day aviation meeting opened on 6 August at the race course. Only No.7 took part in any events, which Edmond completed without incident but with only one award, the second prize for the slowest lap, in which his speed was 45 m.p.h. Meanwhile, more Boxkites were laid down at Filton and Nos. 7 and 8 were allocated as initial equipment of the flying schools at Brooklands and Larkhill, respectively; No.8 retained the Lanark competition number 19 on its rudders for some months. As new aircraft were completed, the schools' complement was doubled, Larkhill receiving No. 9 in September and Brooklands No. 11 in November. Captain Dickson flew No.9 in the army autumn manceuvres in September and Lt. Loraine accompanied him on No.8, which had been equipped with a Thorne-Baker wireless transmitter. Nos. 10 and 12 were specially prepared for the Missions to Australia and India, respectively, the latter being the first to have upper wing extensions. The next two, Nos. 12A and 14 (No. 13 being unacceptable to any pilot of that date!) were flown from Durdham Down in the first public demonstration of the Company's activities; when these ended No. 12A was lent to Oscar Morison, who flew it in various demonstrations and competitions; No. 14 went on to Larkhill as a school aircraft, releasing No.9 for duty as the spare for the Indian Mission. Two further new Boxkites, Nos. 15 and 16, went to Brooklands, whence No. 11 was brought back for overhaul and packing as the spare for the Australian Mission. No. 16 was fitted with extended wings and a 60 h.p. E.N.V. water-cooled engine; the latter made it technically an 'All British' aeroplane for competition purposes, and thus it became the mount on which Howard Pixton, with Charles Briginshaw as mechanic, won the Manville Prize of ?500 for the highest aggregate time flown on nine specified days in 1911.

Both the Australian and Indian Missions arrived at their destinations in December, and on 6 January 1911 Jullerot demonstrated No. 12 before a Vice-regal party and a large crowd of spectators at the Calcutta Maidan. Invited to participate in the Deccan cavalry manceuvres, Jul1erot made several flights from Aurangabad, from 16 January onwards, carrying Capt. Sefton Brancker as army observer, and later took part in the Northern Manceuvres at Karghpur. Here conditions were very severe and both No. 12 and No.9 came to grief on the rock-strewn terrain, with a ground temperature of 100°F, but many flights were made and repairs kept pace with damage. When all the spares were used up, No. 9 was cannibalised to keep No. 12 flying and the latter survived to return to Larkhill as a school machine, being flown by many notable pupils, including Robert Smith-Barry, who was charged ?15 in October 1911 for repairs after a heavy landing on it.

In Australia, Hammond began flying on No. 10 at Perth late in December, going on to Melbourne, where 32 flights, many with passengers, were made. The Mission then moved to Sydney, whence Hammond went home to New Zealand leaving Macdonald as sole pilot. By 19 May 1911,72 flights totaling 765 miles had been completed without having had to replace a single bqlt or wire on No. 10. The spare machine, No. 11, still in its packing case, was sold to W. E. Hart, of Penrith, N.S.W., together with the unused spares, when the Mission left to return to England. Although this was the only direct sale made by both Missions, the Boxkite had by now begun to attract foreign buyers. The outcome of negotiations with the Russian Attache in Paris, William Rebikoff, was the first Government contract in the world for British aeroplanes, signed on 15 November 1910 for the supply of eight improved Boxkites having enlarged tanks and three rudders, which were called the Military model. The first three of these, Nos. 17, 18 and 19, were at first flown with 50 h.p. Gnomes, although 70 h.p. Gnomes had been specified for delivery in April 1911, when they were to become available. Meanwhile, No. 16, brought up to Military standard with three rudders but retaining its E.N.V. engine, was lent to Claude Grahame-White for an attempt to win the prize of ?4,000 offered by Baron de Forest for a flight from England to the most distant point along the Continental coast. No. 16 was damaged by a storm while waiting to take off from Swingate Downs, Dover, but was repaired in time for a second attempt on 18 December 1910, when Grahame-White was caught by a down-gust at the cliff-edge and crashed. No. 17, which was at Brooklands, was at once dispatched as a replacement, but caught fire soon after arrival at Dover, and Grahame-White then retired from the contest on his doctor's advice. Lt. Loraine had also entered the competition, flying No.8, but this too was badly damaged in the storm; No. 16 was eventually rebuilt and flown again at Brooklands. In April Nos. 18 and 19 were shipped to St. Petersburg together with Nos. 20 to 25 inclusive, after installation of 70 h.p. Gnome engines, but were later exchanged for two new machines, Nos. 26 and 30, in July 1911. No. 18 was damaged in transit back to Filton and written off, but No. 19 survived at Larkhill until May 1913, when it was dismantled and reconstructed as No. 134, which in turn was crashed at the Brooklands school in November 1913.

Still no contract came from the British War Office, and the next two Boxkites, Nos. 27 and 28, were standard school machines bought by the Belgian pilot Joseph Christiaens, who chose them for his flying displays in Malaya and South Africa. He took delivery of them on 19 January 1911, and after successful flights at Singapore on No. 27 went on to Cape Town and Pretoria, where he sold No. 28 to John Weston, who became the Company's agent in South Africa. A further school machine, No. 29, was sent to Brooklands in February 1911 and then two special exhibition models were built, having 70 h.p. Gnome engines, enclosed nacelles and increased span. The first, No. 31, was exhibited at Olympia in March 1911, and the second, No. 32, at St. Petersburg in April. The latter was inspected by the Czar and so impressed his military advisers that a gold medal and certificate of merit were awarded to the Company; and No. 32 was purchased in addition to the eight already ordered.

The War Office at last placed a contract, on 14 March 1911, for four Military Boxkites with 50 h.p. Gnomes as described in a specification submitted on 20 October 1910. Meanwhile Oscar Morison had damaged No. l2A while giving exhibition flights at Brighton, and No. 34 was taken from the production line to replace it. The first two War Office machines, Nos. 37 and 38, were delivered at Larkhill on 18 and 25 May, respectively, but then the War Office asked for the other two to be supplied with 60 h.p. Renault engines for comparison. This required a redesign of the engine mounting and carlingue, which resulted in a substantial nacelle structure in front of the pilot. No. 39, thus modified, was delivered at Larkhill on 9 July, by which time four more had been ordered, two with 50 h.p. Gnomes and two as spare airframes without engines. The latter (Nos. 40 and 41) were dispatched on 31 July, the second Renault machine (No. 42) on 2 August and the remaining Gnome machines (Nos. 48 and 49) during the subsequent fortnight. Nos. 43 and 47 were standard school Boxkites, the first being supplied to Larkhill while the second was taken to France by Versepuy when he returned in September 1911; he demonstrated it at Issy-les-Moulineaux and Vichy, where his mechanic was George Little; subsequently he sold it to the Bulgarian Government, to be flown by Lt. Loultchieff.

By this time the Boxkite production line had become well established and continued, mainly to supply wastage at the various schools, until 1914. In the standard models the wing extensions were retained but the third rudder was deleted. Strict interchangeability of components was maintained, and many later school machines incorporated serviceable parts from earlier aircraft. The 50 h.p. Gnome remained as the standard power unit except for No. 60 and No. 139, which had 70 h.p. Gnomes. The latter machine was supplied to R.N.A.S. Eastchurch in April 1913, receiving Naval serial no. 35, and was standard except for the engine, but No. 60 was similar to Nos. 31 and 32 with an enclosed nacelle, also incorporating longitudinal tanks and a push-pull handwheel control instead of the simple control-stick; this was demonstrated at Cuatros Vientos by Busteed in November 1911 and purchased soon afterwards by the Spanish Government, who ordered a similar spare airframe (No. 79) in which they fitted one of their own 70 h.p. Gnomes. Including rebuilds which received new sequence numbers, the total number of Boxkites built was 76, all at Filton except for the final six (Nos. 394-399), which were the first aeroplanes constructed at the Tramways Company's Brislington works. Although underpowered and out-dated at the end of their career, they survived mishandling often to the point of demolition, but the pupils emerged more or less unscathed and the mechanics performed daily miracles of reconstruction, so that school machines were constantly reappearing Phoenix-like from their own wreckage. Apart from the nine exported to Russia, three were sold to South Africa, two each to Australia, Germany and Spain, and one each to Bulgaria, India, Rumania and Sweden.

In addition to the Boxkite proper, there were two variants, both for competition work. The first of these was No. 44, which had wings of much reduced span and a small single-seat nacelle. This was for Maurice Tetard in the Circuit de l'Europe (racing no. 3) and was first flown on 30 May 1911; in the race it developed engine trouble and Tetard retired at Rheims, half-way through the first stage. The other was No. 69 and was a redesign in November 1911 by Gabriel Voisin using standard wings, but with the gap reduced and the front elevator and booms deleted; a single large tail plane and a single rudder replaced the normal biplane tail unit. It was sent to Larkhill for tests in February 1912. No photograph of this machine has survived and it was apparently soon rebuilt as a standard school Boxkite, in which form it was crashed at Larkhill by Major Forman on 3 November 1912.

SPECIFICATION AND DATA

Type: Bristol Biplane (Boxkite)

Manufacturers: The British & Colonial Aeroplane Co. Ltd., Filton and Brislington, Bristol

Power Plant:

One 50 hp Gregoire

One 50/60 hp E.N.V.

One 50 hp Gnome

One 60 hp Renault

One 70 hp Gnome

Model Standard Extended Racer Voisin

(Military) No. 44 No. 69

Span 34 ft 6 in 47 ft 8 in or 35 ft 32 ft 8 in

46 ft 6 in

Length 38 ft 6 in 38 ft 6 in 38 ft 30 ft 9 in

Height 11 ft 10 in 11 ft 10 in 11 ft 10 in 9 ft 6 in

Wing Area 457 sq ft 517 sq ft 350 sq ft 420 sq ft

Empty Weight 800 lb 900 lb 800 lb 800 lb

All-up Weight 1,050 lb 1,150 lb 1,000 lb 1,000 lb

Speed 40 mph 40 mph 50 mph 50 mph

Accommodation 2 2 1 2

Production 15 61 1 1

Sequence Nos. 7-11 12A 12 15-32 44 69

14 34 43 37-42 47

49 55 62 48 60 67

63 65 66 79 93 99

119 124-129

133-139 179

180 203

204 207

222 226

231 347

394-399

Pioneers in the field: Edmond in Boxkite No.8 at Lanark in August 1910, with (l. to r.) Crisp, Frank Coles, Lesue Macdonald, Collyns Pizey, G. H. Challenger, Bendall and Briginshaw.

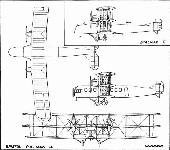

The Bristol Glider

The Bristol Glider was a biplane designed by George Challenger for presentation by Sir George White to the Bristol and West of England Aero Club, of which Sir George was elected President in October 1910; this was a thriving organisation boasting over 75 members. The Glider was designed to carry two persons and was intended to take an engine of 30 h.p. at a later stage. It was sturdily constructed, with double-surfaced mainplanes and tailplane; ailerons were fitted to the upper wing only and the forward and aft elevators were coupled. Two very small rudders were mounted between the upper and lower tail-booms forward of the aft elevator and a conventional control system was used. The Glider was first flown at the Club's flying ground near Keynsham, Somerset, on 17 December 1910, with Challenger at the controls; it was hand-towed down a slope by ropes attached to the lower wing-tips, and a two-wheeled dolly was used for uphill retrieval. On 27 February 1911 it was damaged and was repaired by the Company for the nominal cost of l2s. 6d., but on 4 September 1911 it was more severely crashed and the repairs then cost ?30. No engine was ever installed, but the Glider appears to have survived at least until 1912 ; as it was constructed to Sir George's private order, it had no Bristol sequence number.

SPECIFICATION AND DATA

Type: Glider

Manufacturers: The British & Colonial Aeroplane Co. Ltd., Filton, Bristol

Power Plant: Nil (provision for 30 hp later)

Span: 32 ft 4 in

Length: 33 ft 10 in

Height: 6 ft 8 in

The Bristol Glider was a biplane designed by George Challenger for presentation by Sir George White to the Bristol and West of England Aero Club, of which Sir George was elected President in October 1910; this was a thriving organisation boasting over 75 members. The Glider was designed to carry two persons and was intended to take an engine of 30 h.p. at a later stage. It was sturdily constructed, with double-surfaced mainplanes and tailplane; ailerons were fitted to the upper wing only and the forward and aft elevators were coupled. Two very small rudders were mounted between the upper and lower tail-booms forward of the aft elevator and a conventional control system was used. The Glider was first flown at the Club's flying ground near Keynsham, Somerset, on 17 December 1910, with Challenger at the controls; it was hand-towed down a slope by ropes attached to the lower wing-tips, and a two-wheeled dolly was used for uphill retrieval. On 27 February 1911 it was damaged and was repaired by the Company for the nominal cost of l2s. 6d., but on 4 September 1911 it was more severely crashed and the repairs then cost ?30. No engine was ever installed, but the Glider appears to have survived at least until 1912 ; as it was constructed to Sir George's private order, it had no Bristol sequence number.

SPECIFICATION AND DATA

Type: Glider

Manufacturers: The British & Colonial Aeroplane Co. Ltd., Filton, Bristol

Power Plant: Nil (provision for 30 hp later)

Span: 32 ft 4 in

Length: 33 ft 10 in

Height: 6 ft 8 in

The Bristol Boxkite

The Bristol biplane of 1910, familiarly but inaccurately dubbed 'the Boxkite', was an unashamed copy of the Henri Farman, using the same dimensions and scantlings, but introducing the more refined metal fittings, such as steel clips and cast aluminium strut sockets, of Zodiac practice. The quality of French-built Farmans was somewhat variable, but the Bristol biplane, though similar in general appearance, was equivalent to or better than the best that France had produced at that time. Indeed when the solicitors for Farman Freres proposed to sue the 'Bristol' Directors for infringement of patents, the Directors immediately entered a defence claiming substantial improvements, and no court proceedings ensued. The first two Boxkites were constructed at Filton to drawings made by George Challenger in June 1910, immediately after the abandonment of the Zodiac. They differed from all later Boxkites in having rear elevators with straight trailing edges and in having two, instead of one, intermediate vertical struts between each pair of upper and lower front booms. No. 7 was at first fitted with a 50 h.p. Gregoire four-cylinder engine and No.8 with a 50 h.p. eight-cylinder E.N.V., both being watercooled. A further point of difference was that No.8 had double-surfaced wings whereas No. 7 had a single fabric covering with pockets enclosing the ribs; the latter was standard Farman practice and was adopted on all later Bristol Boxkites, mainly to save weight. The Gregoire was unreliable and deficient in power, so Emile Stern's success in obtaining one of the first 50 h.p. Gnome rotaries released for export was particularly valuable. Fitted with this engine, No.7 was taken to Larkhill on 29 July 1910, assembled overnight, and flown the next day to a height of 150 ft. at the first attempt by Edmond, to the astonishment of beholders who had taken up prone positions on the ground in order to detect the first glimmer of daylight between the grass and the wheels.

With the efficiency of the design thus spectacularly confirmed, the two Boxkites were crated and dispatched to Lanark, where a six-day aviation meeting opened on 6 August at the race course. Only No.7 took part in any events, which Edmond completed without incident but with only one award, the second prize for the slowest lap, in which his speed was 45 m.p.h. Meanwhile, more Boxkites were laid down at Filton and Nos. 7 and 8 were allocated as initial equipment of the flying schools at Brooklands and Larkhill, respectively; No.8 retained the Lanark competition number 19 on its rudders for some months. As new aircraft were completed, the schools' complement was doubled, Larkhill receiving No. 9 in September and Brooklands No. 11 in November. Captain Dickson flew No.9 in the army autumn manceuvres in September and Lt. Loraine accompanied him on No.8, which had been equipped with a Thorne-Baker wireless transmitter. Nos. 10 and 12 were specially prepared for the Missions to Australia and India, respectively, the latter being the first to have upper wing extensions. The next two, Nos. 12A and 14 (No. 13 being unacceptable to any pilot of that date!) were flown from Durdham Down in the first public demonstration of the Company's activities; when these ended No. 12A was lent to Oscar Morison, who flew it in various demonstrations and competitions; No. 14 went on to Larkhill as a school aircraft, releasing No.9 for duty as the spare for the Indian Mission. Two further new Boxkites, Nos. 15 and 16, went to Brooklands, whence No. 11 was brought back for overhaul and packing as the spare for the Australian Mission. No. 16 was fitted with extended wings and a 60 h.p. E.N.V. water-cooled engine; the latter made it technically an 'All British' aeroplane for competition purposes, and thus it became the mount on which Howard Pixton, with Charles Briginshaw as mechanic, won the Manville Prize of ?500 for the highest aggregate time flown on nine specified days in 1911.

Both the Australian and Indian Missions arrived at their destinations in December, and on 6 January 1911 Jullerot demonstrated No. 12 before a Vice-regal party and a large crowd of spectators at the Calcutta Maidan. Invited to participate in the Deccan cavalry manceuvres, Jul1erot made several flights from Aurangabad, from 16 January onwards, carrying Capt. Sefton Brancker as army observer, and later took part in the Northern Manceuvres at Karghpur. Here conditions were very severe and both No. 12 and No.9 came to grief on the rock-strewn terrain, with a ground temperature of 100°F, but many flights were made and repairs kept pace with damage. When all the spares were used up, No. 9 was cannibalised to keep No. 12 flying and the latter survived to return to Larkhill as a school machine, being flown by many notable pupils, including Robert Smith-Barry, who was charged ?15 in October 1911 for repairs after a heavy landing on it.

In Australia, Hammond began flying on No. 10 at Perth late in December, going on to Melbourne, where 32 flights, many with passengers, were made. The Mission then moved to Sydney, whence Hammond went home to New Zealand leaving Macdonald as sole pilot. By 19 May 1911,72 flights totaling 765 miles had been completed without having had to replace a single bqlt or wire on No. 10. The spare machine, No. 11, still in its packing case, was sold to W. E. Hart, of Penrith, N.S.W., together with the unused spares, when the Mission left to return to England. Although this was the only direct sale made by both Missions, the Boxkite had by now begun to attract foreign buyers. The outcome of negotiations with the Russian Attache in Paris, William Rebikoff, was the first Government contract in the world for British aeroplanes, signed on 15 November 1910 for the supply of eight improved Boxkites having enlarged tanks and three rudders, which were called the Military model. The first three of these, Nos. 17, 18 and 19, were at first flown with 50 h.p. Gnomes, although 70 h.p. Gnomes had been specified for delivery in April 1911, when they were to become available. Meanwhile, No. 16, brought up to Military standard with three rudders but retaining its E.N.V. engine, was lent to Claude Grahame-White for an attempt to win the prize of ?4,000 offered by Baron de Forest for a flight from England to the most distant point along the Continental coast. No. 16 was damaged by a storm while waiting to take off from Swingate Downs, Dover, but was repaired in time for a second attempt on 18 December 1910, when Grahame-White was caught by a down-gust at the cliff-edge and crashed. No. 17, which was at Brooklands, was at once dispatched as a replacement, but caught fire soon after arrival at Dover, and Grahame-White then retired from the contest on his doctor's advice. Lt. Loraine had also entered the competition, flying No.8, but this too was badly damaged in the storm; No. 16 was eventually rebuilt and flown again at Brooklands. In April Nos. 18 and 19 were shipped to St. Petersburg together with Nos. 20 to 25 inclusive, after installation of 70 h.p. Gnome engines, but were later exchanged for two new machines, Nos. 26 and 30, in July 1911. No. 18 was damaged in transit back to Filton and written off, but No. 19 survived at Larkhill until May 1913, when it was dismantled and reconstructed as No. 134, which in turn was crashed at the Brooklands school in November 1913.

Still no contract came from the British War Office, and the next two Boxkites, Nos. 27 and 28, were standard school machines bought by the Belgian pilot Joseph Christiaens, who chose them for his flying displays in Malaya and South Africa. He took delivery of them on 19 January 1911, and after successful flights at Singapore on No. 27 went on to Cape Town and Pretoria, where he sold No. 28 to John Weston, who became the Company's agent in South Africa. A further school machine, No. 29, was sent to Brooklands in February 1911 and then two special exhibition models were built, having 70 h.p. Gnome engines, enclosed nacelles and increased span. The first, No. 31, was exhibited at Olympia in March 1911, and the second, No. 32, at St. Petersburg in April. The latter was inspected by the Czar and so impressed his military advisers that a gold medal and certificate of merit were awarded to the Company; and No. 32 was purchased in addition to the eight already ordered.

The War Office at last placed a contract, on 14 March 1911, for four Military Boxkites with 50 h.p. Gnomes as described in a specification submitted on 20 October 1910. Meanwhile Oscar Morison had damaged No. l2A while giving exhibition flights at Brighton, and No. 34 was taken from the production line to replace it. The first two War Office machines, Nos. 37 and 38, were delivered at Larkhill on 18 and 25 May, respectively, but then the War Office asked for the other two to be supplied with 60 h.p. Renault engines for comparison. This required a redesign of the engine mounting and carlingue, which resulted in a substantial nacelle structure in front of the pilot. No. 39, thus modified, was delivered at Larkhill on 9 July, by which time four more had been ordered, two with 50 h.p. Gnomes and two as spare airframes without engines. The latter (Nos. 40 and 41) were dispatched on 31 July, the second Renault machine (No. 42) on 2 August and the remaining Gnome machines (Nos. 48 and 49) during the subsequent fortnight. Nos. 43 and 47 were standard school Boxkites, the first being supplied to Larkhill while the second was taken to France by Versepuy when he returned in September 1911; he demonstrated it at Issy-les-Moulineaux and Vichy, where his mechanic was George Little; subsequently he sold it to the Bulgarian Government, to be flown by Lt. Loultchieff.

By this time the Boxkite production line had become well established and continued, mainly to supply wastage at the various schools, until 1914. In the standard models the wing extensions were retained but the third rudder was deleted. Strict interchangeability of components was maintained, and many later school machines incorporated serviceable parts from earlier aircraft. The 50 h.p. Gnome remained as the standard power unit except for No. 60 and No. 139, which had 70 h.p. Gnomes. The latter machine was supplied to R.N.A.S. Eastchurch in April 1913, receiving Naval serial no. 35, and was standard except for the engine, but No. 60 was similar to Nos. 31 and 32 with an enclosed nacelle, also incorporating longitudinal tanks and a push-pull handwheel control instead of the simple control-stick; this was demonstrated at Cuatros Vientos by Busteed in November 1911 and purchased soon afterwards by the Spanish Government, who ordered a similar spare airframe (No. 79) in which they fitted one of their own 70 h.p. Gnomes. Including rebuilds which received new sequence numbers, the total number of Boxkites built was 76, all at Filton except for the final six (Nos. 394-399), which were the first aeroplanes constructed at the Tramways Company's Brislington works. Although underpowered and out-dated at the end of their career, they survived mishandling often to the point of demolition, but the pupils emerged more or less unscathed and the mechanics performed daily miracles of reconstruction, so that school machines were constantly reappearing Phoenix-like from their own wreckage. Apart from the nine exported to Russia, three were sold to South Africa, two each to Australia, Germany and Spain, and one each to Bulgaria, India, Rumania and Sweden.

In addition to the Boxkite proper, there were two variants, both for competition work. The first of these was No. 44, which had wings of much reduced span and a small single-seat nacelle. This was for Maurice Tetard in the Circuit de l'Europe (racing no. 3) and was first flown on 30 May 1911; in the race it developed engine trouble and Tetard retired at Rheims, half-way through the first stage. The other was No. 69 and was a redesign in November 1911 by Gabriel Voisin using standard wings, but with the gap reduced and the front elevator and booms deleted; a single large tail plane and a single rudder replaced the normal biplane tail unit. It was sent to Larkhill for tests in February 1912. No photograph of this machine has survived and it was apparently soon rebuilt as a standard school Boxkite, in which form it was crashed at Larkhill by Major Forman on 3 November 1912.

SPECIFICATION AND DATA

Type: Bristol Biplane (Boxkite)

Manufacturers: The British & Colonial Aeroplane Co. Ltd., Filton and Brislington, Bristol

Power Plant:

One 50 hp Gregoire

One 50/60 hp E.N.V.

One 50 hp Gnome

One 60 hp Renault

One 70 hp Gnome

Model Standard Extended Racer Voisin

(Military) No. 44 No. 69

Span 34 ft 6 in 47 ft 8 in or 35 ft 32 ft 8 in

46 ft 6 in

Length 38 ft 6 in 38 ft 6 in 38 ft 30 ft 9 in

Height 11 ft 10 in 11 ft 10 in 11 ft 10 in 9 ft 6 in

Wing Area 457 sq ft 517 sq ft 350 sq ft 420 sq ft

Empty Weight 800 lb 900 lb 800 lb 800 lb

All-up Weight 1,050 lb 1,150 lb 1,000 lb 1,000 lb

Speed 40 mph 40 mph 50 mph 50 mph

Accommodation 2 2 1 2

Production 15 61 1 1

Sequence Nos. 7-11 12A 12 15-32 44 69

14 34 43 37-42 47

49 55 62 48 60 67

63 65 66 79 93 99

119 124-129

133-139 179

180 203

204 207

222 226

231 347

394-399

The Bristol biplane of 1910, familiarly but inaccurately dubbed 'the Boxkite', was an unashamed copy of the Henri Farman, using the same dimensions and scantlings, but introducing the more refined metal fittings, such as steel clips and cast aluminium strut sockets, of Zodiac practice. The quality of French-built Farmans was somewhat variable, but the Bristol biplane, though similar in general appearance, was equivalent to or better than the best that France had produced at that time. Indeed when the solicitors for Farman Freres proposed to sue the 'Bristol' Directors for infringement of patents, the Directors immediately entered a defence claiming substantial improvements, and no court proceedings ensued. The first two Boxkites were constructed at Filton to drawings made by George Challenger in June 1910, immediately after the abandonment of the Zodiac. They differed from all later Boxkites in having rear elevators with straight trailing edges and in having two, instead of one, intermediate vertical struts between each pair of upper and lower front booms. No. 7 was at first fitted with a 50 h.p. Gregoire four-cylinder engine and No.8 with a 50 h.p. eight-cylinder E.N.V., both being watercooled. A further point of difference was that No.8 had double-surfaced wings whereas No. 7 had a single fabric covering with pockets enclosing the ribs; the latter was standard Farman practice and was adopted on all later Bristol Boxkites, mainly to save weight. The Gregoire was unreliable and deficient in power, so Emile Stern's success in obtaining one of the first 50 h.p. Gnome rotaries released for export was particularly valuable. Fitted with this engine, No.7 was taken to Larkhill on 29 July 1910, assembled overnight, and flown the next day to a height of 150 ft. at the first attempt by Edmond, to the astonishment of beholders who had taken up prone positions on the ground in order to detect the first glimmer of daylight between the grass and the wheels.

With the efficiency of the design thus spectacularly confirmed, the two Boxkites were crated and dispatched to Lanark, where a six-day aviation meeting opened on 6 August at the race course. Only No.7 took part in any events, which Edmond completed without incident but with only one award, the second prize for the slowest lap, in which his speed was 45 m.p.h. Meanwhile, more Boxkites were laid down at Filton and Nos. 7 and 8 were allocated as initial equipment of the flying schools at Brooklands and Larkhill, respectively; No.8 retained the Lanark competition number 19 on its rudders for some months. As new aircraft were completed, the schools' complement was doubled, Larkhill receiving No. 9 in September and Brooklands No. 11 in November. Captain Dickson flew No.9 in the army autumn manceuvres in September and Lt. Loraine accompanied him on No.8, which had been equipped with a Thorne-Baker wireless transmitter. Nos. 10 and 12 were specially prepared for the Missions to Australia and India, respectively, the latter being the first to have upper wing extensions. The next two, Nos. 12A and 14 (No. 13 being unacceptable to any pilot of that date!) were flown from Durdham Down in the first public demonstration of the Company's activities; when these ended No. 12A was lent to Oscar Morison, who flew it in various demonstrations and competitions; No. 14 went on to Larkhill as a school aircraft, releasing No.9 for duty as the spare for the Indian Mission. Two further new Boxkites, Nos. 15 and 16, went to Brooklands, whence No. 11 was brought back for overhaul and packing as the spare for the Australian Mission. No. 16 was fitted with extended wings and a 60 h.p. E.N.V. water-cooled engine; the latter made it technically an 'All British' aeroplane for competition purposes, and thus it became the mount on which Howard Pixton, with Charles Briginshaw as mechanic, won the Manville Prize of ?500 for the highest aggregate time flown on nine specified days in 1911.

Both the Australian and Indian Missions arrived at their destinations in December, and on 6 January 1911 Jullerot demonstrated No. 12 before a Vice-regal party and a large crowd of spectators at the Calcutta Maidan. Invited to participate in the Deccan cavalry manceuvres, Jul1erot made several flights from Aurangabad, from 16 January onwards, carrying Capt. Sefton Brancker as army observer, and later took part in the Northern Manceuvres at Karghpur. Here conditions were very severe and both No. 12 and No.9 came to grief on the rock-strewn terrain, with a ground temperature of 100°F, but many flights were made and repairs kept pace with damage. When all the spares were used up, No. 9 was cannibalised to keep No. 12 flying and the latter survived to return to Larkhill as a school machine, being flown by many notable pupils, including Robert Smith-Barry, who was charged ?15 in October 1911 for repairs after a heavy landing on it.

In Australia, Hammond began flying on No. 10 at Perth late in December, going on to Melbourne, where 32 flights, many with passengers, were made. The Mission then moved to Sydney, whence Hammond went home to New Zealand leaving Macdonald as sole pilot. By 19 May 1911,72 flights totaling 765 miles had been completed without having had to replace a single bqlt or wire on No. 10. The spare machine, No. 11, still in its packing case, was sold to W. E. Hart, of Penrith, N.S.W., together with the unused spares, when the Mission left to return to England. Although this was the only direct sale made by both Missions, the Boxkite had by now begun to attract foreign buyers. The outcome of negotiations with the Russian Attache in Paris, William Rebikoff, was the first Government contract in the world for British aeroplanes, signed on 15 November 1910 for the supply of eight improved Boxkites having enlarged tanks and three rudders, which were called the Military model. The first three of these, Nos. 17, 18 and 19, were at first flown with 50 h.p. Gnomes, although 70 h.p. Gnomes had been specified for delivery in April 1911, when they were to become available. Meanwhile, No. 16, brought up to Military standard with three rudders but retaining its E.N.V. engine, was lent to Claude Grahame-White for an attempt to win the prize of ?4,000 offered by Baron de Forest for a flight from England to the most distant point along the Continental coast. No. 16 was damaged by a storm while waiting to take off from Swingate Downs, Dover, but was repaired in time for a second attempt on 18 December 1910, when Grahame-White was caught by a down-gust at the cliff-edge and crashed. No. 17, which was at Brooklands, was at once dispatched as a replacement, but caught fire soon after arrival at Dover, and Grahame-White then retired from the contest on his doctor's advice. Lt. Loraine had also entered the competition, flying No.8, but this too was badly damaged in the storm; No. 16 was eventually rebuilt and flown again at Brooklands. In April Nos. 18 and 19 were shipped to St. Petersburg together with Nos. 20 to 25 inclusive, after installation of 70 h.p. Gnome engines, but were later exchanged for two new machines, Nos. 26 and 30, in July 1911. No. 18 was damaged in transit back to Filton and written off, but No. 19 survived at Larkhill until May 1913, when it was dismantled and reconstructed as No. 134, which in turn was crashed at the Brooklands school in November 1913.

Still no contract came from the British War Office, and the next two Boxkites, Nos. 27 and 28, were standard school machines bought by the Belgian pilot Joseph Christiaens, who chose them for his flying displays in Malaya and South Africa. He took delivery of them on 19 January 1911, and after successful flights at Singapore on No. 27 went on to Cape Town and Pretoria, where he sold No. 28 to John Weston, who became the Company's agent in South Africa. A further school machine, No. 29, was sent to Brooklands in February 1911 and then two special exhibition models were built, having 70 h.p. Gnome engines, enclosed nacelles and increased span. The first, No. 31, was exhibited at Olympia in March 1911, and the second, No. 32, at St. Petersburg in April. The latter was inspected by the Czar and so impressed his military advisers that a gold medal and certificate of merit were awarded to the Company; and No. 32 was purchased in addition to the eight already ordered.

The War Office at last placed a contract, on 14 March 1911, for four Military Boxkites with 50 h.p. Gnomes as described in a specification submitted on 20 October 1910. Meanwhile Oscar Morison had damaged No. l2A while giving exhibition flights at Brighton, and No. 34 was taken from the production line to replace it. The first two War Office machines, Nos. 37 and 38, were delivered at Larkhill on 18 and 25 May, respectively, but then the War Office asked for the other two to be supplied with 60 h.p. Renault engines for comparison. This required a redesign of the engine mounting and carlingue, which resulted in a substantial nacelle structure in front of the pilot. No. 39, thus modified, was delivered at Larkhill on 9 July, by which time four more had been ordered, two with 50 h.p. Gnomes and two as spare airframes without engines. The latter (Nos. 40 and 41) were dispatched on 31 July, the second Renault machine (No. 42) on 2 August and the remaining Gnome machines (Nos. 48 and 49) during the subsequent fortnight. Nos. 43 and 47 were standard school Boxkites, the first being supplied to Larkhill while the second was taken to France by Versepuy when he returned in September 1911; he demonstrated it at Issy-les-Moulineaux and Vichy, where his mechanic was George Little; subsequently he sold it to the Bulgarian Government, to be flown by Lt. Loultchieff.

By this time the Boxkite production line had become well established and continued, mainly to supply wastage at the various schools, until 1914. In the standard models the wing extensions were retained but the third rudder was deleted. Strict interchangeability of components was maintained, and many later school machines incorporated serviceable parts from earlier aircraft. The 50 h.p. Gnome remained as the standard power unit except for No. 60 and No. 139, which had 70 h.p. Gnomes. The latter machine was supplied to R.N.A.S. Eastchurch in April 1913, receiving Naval serial no. 35, and was standard except for the engine, but No. 60 was similar to Nos. 31 and 32 with an enclosed nacelle, also incorporating longitudinal tanks and a push-pull handwheel control instead of the simple control-stick; this was demonstrated at Cuatros Vientos by Busteed in November 1911 and purchased soon afterwards by the Spanish Government, who ordered a similar spare airframe (No. 79) in which they fitted one of their own 70 h.p. Gnomes. Including rebuilds which received new sequence numbers, the total number of Boxkites built was 76, all at Filton except for the final six (Nos. 394-399), which were the first aeroplanes constructed at the Tramways Company's Brislington works. Although underpowered and out-dated at the end of their career, they survived mishandling often to the point of demolition, but the pupils emerged more or less unscathed and the mechanics performed daily miracles of reconstruction, so that school machines were constantly reappearing Phoenix-like from their own wreckage. Apart from the nine exported to Russia, three were sold to South Africa, two each to Australia, Germany and Spain, and one each to Bulgaria, India, Rumania and Sweden.

In addition to the Boxkite proper, there were two variants, both for competition work. The first of these was No. 44, which had wings of much reduced span and a small single-seat nacelle. This was for Maurice Tetard in the Circuit de l'Europe (racing no. 3) and was first flown on 30 May 1911; in the race it developed engine trouble and Tetard retired at Rheims, half-way through the first stage. The other was No. 69 and was a redesign in November 1911 by Gabriel Voisin using standard wings, but with the gap reduced and the front elevator and booms deleted; a single large tail plane and a single rudder replaced the normal biplane tail unit. It was sent to Larkhill for tests in February 1912. No photograph of this machine has survived and it was apparently soon rebuilt as a standard school Boxkite, in which form it was crashed at Larkhill by Major Forman on 3 November 1912.

SPECIFICATION AND DATA

Type: Bristol Biplane (Boxkite)

Manufacturers: The British & Colonial Aeroplane Co. Ltd., Filton and Brislington, Bristol

Power Plant:

One 50 hp Gregoire

One 50/60 hp E.N.V.

One 50 hp Gnome

One 60 hp Renault

One 70 hp Gnome

Model Standard Extended Racer Voisin

(Military) No. 44 No. 69

Span 34 ft 6 in 47 ft 8 in or 35 ft 32 ft 8 in

46 ft 6 in

Length 38 ft 6 in 38 ft 6 in 38 ft 30 ft 9 in

Height 11 ft 10 in 11 ft 10 in 11 ft 10 in 9 ft 6 in

Wing Area 457 sq ft 517 sq ft 350 sq ft 420 sq ft

Empty Weight 800 lb 900 lb 800 lb 800 lb

All-up Weight 1,050 lb 1,150 lb 1,000 lb 1,000 lb

Speed 40 mph 40 mph 50 mph 50 mph

Accommodation 2 2 1 2

Production 15 61 1 1

Sequence Nos. 7-11 12A 12 15-32 44 69

14 34 43 37-42 47

49 55 62 48 60 67

63 65 66 79 93 99

119 124-129

133-139 179

180 203

204 207

222 226

231 347

394-399

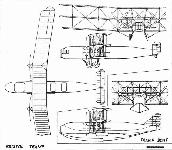

The Bristol Monoplane (1911)

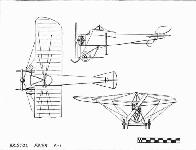

The first Bristol monoplane was designed by George Challenger and Archibald Low in January 1911 and was a single-seater incorporating both Bleriot and Antoinette features, having the warping wing of the former and the slim, triangular-section fuselage of the latter. The 50 h.p. Gnome engine was mounted in a steel frame, and the undercarriage was a simple arrangement of two wheels and a central skid anticipating that of the famous Avro 504 biplane. Two of these monoplanes (Nos. 35 and 36) were constructed in February 1911, and the first was sent to Larkhill for preliminary testing before returning to Filton to be prepared for the Olympia Exhibition in March. It attracted great interest there and the second monoplane was similarly shown at St. Petersburg from 23 to 30 April. When flight tests of No. 35 were attempted by Versepuy at Larkhill, the monoplane failed to take-off and was damaged, and no attempt was made to repair it, in view of Pierre Prier's impending arrival as a monoplane designer.

SPECIFICATION AND DATA

Type: Tractor Monoplane (1911)

Manufacturers: The British & Colonial Aeroplane Co. Ltd., Filton, Bristol

Power Plant: One 50 hp Gnome

Span: 33 ft 6 in

Length: 31 ft 6 in

Wing Area: 215 sq ft

Empty Weight: 580lb

All-up Weight: 760lb

Speed: 55 mph (estimated)

Accommodation: Pilot only

Production: 2

Sequence Nos.: 35,36

The first Bristol monoplane was designed by George Challenger and Archibald Low in January 1911 and was a single-seater incorporating both Bleriot and Antoinette features, having the warping wing of the former and the slim, triangular-section fuselage of the latter. The 50 h.p. Gnome engine was mounted in a steel frame, and the undercarriage was a simple arrangement of two wheels and a central skid anticipating that of the famous Avro 504 biplane. Two of these monoplanes (Nos. 35 and 36) were constructed in February 1911, and the first was sent to Larkhill for preliminary testing before returning to Filton to be prepared for the Olympia Exhibition in March. It attracted great interest there and the second monoplane was similarly shown at St. Petersburg from 23 to 30 April. When flight tests of No. 35 were attempted by Versepuy at Larkhill, the monoplane failed to take-off and was damaged, and no attempt was made to repair it, in view of Pierre Prier's impending arrival as a monoplane designer.

SPECIFICATION AND DATA

Type: Tractor Monoplane (1911)

Manufacturers: The British & Colonial Aeroplane Co. Ltd., Filton, Bristol

Power Plant: One 50 hp Gnome

Span: 33 ft 6 in

Length: 31 ft 6 in

Wing Area: 215 sq ft

Empty Weight: 580lb

All-up Weight: 760lb

Speed: 55 mph (estimated)

Accommodation: Pilot only

Production: 2

Sequence Nos.: 35,36

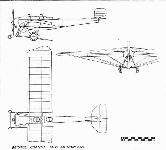

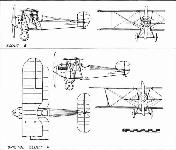

The Bristol-Prier Monoplanes

Pierre Prier was an experienced Bleriot pilot and a qualified engineer, who made the first non-stop flight from London to Paris on 12 April, 1911, while he was chief-instructor of the Bleriot school at Hendon. He was keen to design aeroplanes to his own ideas and found the opportunity to do so when invited to join the British and Colonial Aeroplane Company's staff in June. He at once undertook the design of a fast single-seat monoplane to compete in the annual Gordon Bennett Cup race, at Eastchurch on 1 July, when it was to be flown by Graham Gilmour. In spite of all efforts, this monoplane, Type P-1, No. 46, could not be completed in time for the race, but two more (Nos. 56 and 57), of almost identical design but with overhung engine mountings, were put in hand for the Circuit of Britain competition, in which they were to be flown, respectively, by Prier himself and Oscar Morison. Unfortunately Prier crashed No. 56 on the morning of the race and meanwhile Morison injured his eye, so the Prier monoplane's debut had again to be postponed. The P-1 had a 50 h.p. Gnome engine and Bleriot-type warping wings; its undercarriage had sprung skids, and the tail unit comprised a balanced rudder and a single balanced elevator without any fixed surfaces. The designed top speed of 70 m.p.h. was achieved without difficulty, and the next development was to produce a useful two-seater version. The first of these, No. 58, was the prototype of a successful series of military and training monoplanes, which were produced in some numbers during 1912 and followed the Boxkite into service in military flying schools in Spain, Italy and Germany as well as at Larkhill, Brooklands and the Central Flying School. The single-seat version was also developed as a low-powered runabout for advanced solo pupils, for which purpose it was fitted with a three-cylinder Anzani radial engine of 35 h.p. Nos. 46 and 57 were the first to be so converted, and one new single-seater, No. 68, was built to the same standard. It was intended to install a 40 h.p. Clement Bayard flat-twin engine in No. 57 at a later date, but this engine shed its airscrew while being run on test, causing severe head injuries to Herbert Thomas which nearly proved fatal. No. 56 retained its Gnome engine, and was acquired, after repairs, by James Valentine, who flew it on a cross-country flight to qualify for one of the first Superior Certificates granted by the Royal Aero Club. In November 1911 he fitted it with a 40 h.p. Isaacson radial engine for entry in the British Michelin Cup no. 2 competition, which was restricted to all-British aircraft and pilots.

Prier and Valentine flew the two-seater, No. 58, extensively during September and October 1911 and satisfied the Directors that it was suitable for quantity production with a good prospect in foreign markets. A batch of six, Nos. 71-76, was laid down and the first was specially finished for exhibition at the Paris Salon de l'Aeronautique in December 1911, where it was the sole British representative. All steel parts were burnished and 'blued' to resist rust, aluminium panels were polished to mirror finish and the decking round the cockpits and the wing tread-plates were panelled in plywood. The seats were suspended on wires and, like the cockpit rims, were upholstered in pigskin. A cellulose acetate window was fitted in the sloping front bulkhead to give the passenger a downward view and a sketching board, map case and stowages for binoculars and vacuum flask were also provided. Each cockpit had a Clift compass and the cowling was extended well over the engine to prevent oil being thrown back. A speed of 65 m.p.h. was guaranteed and the price quoted was Fr. 23,750 (about ?950). No. 71 was dispatched from Filton to Paris on 10 December 1911 and No. 72 was shipped to Cuatros Vientos for demonstration to the Spanish Army on 19 December. No. 73 had been sent incomplete to Larkhill in November as a replacement for No. 58 which had crashed on 30 October and No. 74 was rushed out to Issy-les-Moulineaux on 22 December, just before the Filton works closed for Christmas. So when the Paris Salon opened, visitors who had been impressed by the appearance of No. 71 were further delighted by seeing Valentine flying No. 74 round the Eiffel Tower. Valentine was in constant demand for further demonstrations, and on 2 January 1912 made a spectacular arrival with a passenger at St. Cyr in appalling weather just before dusk. A few days later, flying with Capt. Agostini of the Italian Army as passenger, Valentine found his landing baulked by troops, after a long glide with engine off. Unable to restart, he had to swerve through the top of a tree to find a clear space for landing, but, although a branch was carried away, only minor damage resulted. Capt. Agostini was so impressed by this evidence of sturdy construction that an order for two monoplanes arrived from the Italian Government before the end of the week.

Howard Pixton, who had gone to Madrid to demonstrate No. 72, was faced with a more formidable task than Valentine, for Cuatros Vientos is 3,000 ft. above sea level and the Spanish army tests included landing on and taking-off from a freshly ploughed field. The only other competitor, a German, declared this feat to be impossible, and Pixton, too, was worried about the loss of power at this altitude. Then Busteed arrived on Boxkite No. 60 and made short work of the ploughed field test and subsequently both machines were demonstrated to King Alfonso and his staff; the Spanish Government then adopted Bristol aeroplanes as standard equipment for its School of Military Aviation, both aircraft were purchased and two more Prier monoplanes and a further Boxkite were ordered.

When the Spanish trials ended Pixton was summoned to Doberitz, near Berlin, to demonstrate No. 74, which had been shipped to Germany when Valentine returned from Paris. Pixton flew the machine several times before German staff officers at Doberitz and once before the Kaiser at Potsdam. Once when Pixton was challenged by a Rumpler pilot to fly in very gusty conditions he easily out-manoeuvred his rival, but misjudged his height and touched down at high speed, bounced high and then landed safely. Frank Coles, Pixton's mechanic, remarked that this was a test of the undercarriage and was able to warn Pixton before he had time to apologise for an error of judgment, but later a German pilot tried to do the same and came to grief. These demonstrations marked the formation of the Deutsche Bristol-Werke and its associated flying school at Halberstadt, to which No. 74 was handed over on 30 March 1912.

Meanwhile, on 11 January, the War Office had ordered a Prier monoplane for the Army Air Battalion, and on 17 February Lt. Reynolds took delivery of No. 75 at Larkhill. It was generally similar to No. 71 but had a strengthened rudder post and a cane tail skid with an aluminium shoe on the end. Like all Prier monoplanes, it was fitted with a Rubery Owen quick-release catch which could be attached to a rope and picket before starting and released from the cockpit, thus dispensing with wheel chocks and the helpers who were always liable to damage the floating elevator. The last of the initial batch, No. 76, was a two-seater like the others, but was equipped for alternative use as a long-range single-seater, with a combined auxiliary fuel and oil tank to fit the front seat and a waterproof cover for the front cockpit. No. 76 was delivered to the Italian Government on 4 April, and a similar machine from the second production batch, No. 84, followed on 1 June.

The second batch of Prier monoplanes (Nos. 81-98) comprised both single-seaters and two-seaters, and several of the latter were an improved model introduced by Capt. Dickson, having a fixed tailplane and a hinged elevator and the fuselage lengthened by 30 in. The first of this Prier-Dickson type was No. 82, which was sent to Larkhill on 27 July 1912 and proved very successful. No. 81 was a single-seater with Anzani engine similar to No. 68 and was sent to Spain in April, together with No. 83, a two-seater similar to No. 72. No. 83 crashed before acceptance by the Spanish authorities, and No. 82 was then sent to Spain as a replacement, but not before the advantages of the revised fuselage and tail had been noted by the Royal Flying Corps at Larkhill. Consequently, when No. 75 needed repairs in June, it was modified to the new standard and redelivered as a Prier-Dickson, bearing its new military number 256. Almost at once it crashed, but was again repaired at Filton and returned to service on 23 July 1912. Only two more 'short' Prier two-seaters were built, No. 90 which went to Italy in September and No. 94 (largely a rebuild of No. 71) which was demonstrated by Pixton at Bucharest in May and then returned to Brooklands as a trainer, being finally crashed by Lindsay Campbell on 10 August 1912. No. 85 was a Prier-Dickson for the German Government and was delivered on 4 June; Nos. 86 and 88 were similar machines with 70h.p. Gnomes for the Turkish Government and were dispatched in July to Constantinople, where Coles erected and Pixton tested them. No. 87 was delivered to the Bulgarian Government at Sofia on 16 September; it was flown in the Balkan War and once carried Hubert Wilkins (later famous as a polar explorer) as a passenger to take films for a London newspaper. No. 89 was the third two-seater for Italy, shipped on 14 August, while No. 91 was the second machine for the Royal Flying Corps, who took delivery on 23 August 1912, allotting it serial 261. The remainder of the second batch were Anzani-engined single-seaters generally similar to No. 81; Nos. 95 and 96 were sent to Italy in May 1912 and were returned to Filton, intact but well worn, as late as January 1914. No. 97 was built for the Larkhill school in May 1912, but was wrecked a month later, when No. 98 was built as its replacement; the latter had a fixed tailplane, as did the final Prier single-seater, No. 102, which went to Larkhill in November as an additional school machine.

After Prier left the Company in 1912, Coanda perpetuated the long-fuselage model for school duties, and three more were built before December 1912. Of these, No. 130 crashed on a test flight, being rebuilt as No. 155 and retained at Larkhill school. No. 156 was sold to the Deutsche Bristol-Werke school at Halberstadt. Coanda also introduced a side-by-side variant of the Prier-Dickson, of which three were built, No. 107 for the Halberstadt school in June, with No. 109 following as a spare airframe in December, while No. 108 was delivered to the Larkhill school in October and was crashed by Major Hewetson on 18 July 1913. The side-by-side variant was described in one of the Company's catalogues as the 'Sociable' model, the tandem two-seater being called the 'Military' and the single-seater the 'Popular', but these appellations failed to gain currency. Thirty-four Prier monoplanes were built in all between July 1911 and December 1912.

SPECIFICATION AND DATA

Type: Prier Monoplanes

Manufacturers: The British & Colonial Aeroplane Co. Ltd., Filton, Bristol

Power Plants: One 50 hp Gnome (P-1 and 2-seaters)

One 70 hp Gnome (2-seater long-body)

One 35 hp Anzani (single-seaters only)

One 40 hp Isaacson (single-seaters only)

One 40 hp Clement-Bayard (single-seaters only)

Model P-1 single seat two seat two seat two-seat

school short body long body side-by-side

Span 30 ft 2in 30 ft 2 in 32 ft 9 in 34 ft 35 ft 6 in

Length 24 ft 6in 24 ft 6in 24 ft 6in 26 ft 26 ft

Height 9 ft 9 in 9 ft 9 in 9 ft 9 in 9 ft 9 in 9 ft 9 in

Wing Area 166 sq ft 166 sq ft 185 sq ft 200 sq ft 200 sq ft

Empty Weight 640 lb 620 lb 650 lb 660 lb 660 lb

All-up Weight 820 lb 780 lb 1,000 lb 1,080 lb 1,080 lb

Speed 68 mph 58 mph 65 mph 65 mph 65 mph

Accomodation 1 1 2 2 2

Production 3 7 11 10 3

Sequence Nos. 46 56 57 68 81 95- 58 71-76 82 85-89 107-109

98 102 83 84 90 91 130

94 155 156

Pierre Prier was an experienced Bleriot pilot and a qualified engineer, who made the first non-stop flight from London to Paris on 12 April, 1911, while he was chief-instructor of the Bleriot school at Hendon. He was keen to design aeroplanes to his own ideas and found the opportunity to do so when invited to join the British and Colonial Aeroplane Company's staff in June. He at once undertook the design of a fast single-seat monoplane to compete in the annual Gordon Bennett Cup race, at Eastchurch on 1 July, when it was to be flown by Graham Gilmour. In spite of all efforts, this monoplane, Type P-1, No. 46, could not be completed in time for the race, but two more (Nos. 56 and 57), of almost identical design but with overhung engine mountings, were put in hand for the Circuit of Britain competition, in which they were to be flown, respectively, by Prier himself and Oscar Morison. Unfortunately Prier crashed No. 56 on the morning of the race and meanwhile Morison injured his eye, so the Prier monoplane's debut had again to be postponed. The P-1 had a 50 h.p. Gnome engine and Bleriot-type warping wings; its undercarriage had sprung skids, and the tail unit comprised a balanced rudder and a single balanced elevator without any fixed surfaces. The designed top speed of 70 m.p.h. was achieved without difficulty, and the next development was to produce a useful two-seater version. The first of these, No. 58, was the prototype of a successful series of military and training monoplanes, which were produced in some numbers during 1912 and followed the Boxkite into service in military flying schools in Spain, Italy and Germany as well as at Larkhill, Brooklands and the Central Flying School. The single-seat version was also developed as a low-powered runabout for advanced solo pupils, for which purpose it was fitted with a three-cylinder Anzani radial engine of 35 h.p. Nos. 46 and 57 were the first to be so converted, and one new single-seater, No. 68, was built to the same standard. It was intended to install a 40 h.p. Clement Bayard flat-twin engine in No. 57 at a later date, but this engine shed its airscrew while being run on test, causing severe head injuries to Herbert Thomas which nearly proved fatal. No. 56 retained its Gnome engine, and was acquired, after repairs, by James Valentine, who flew it on a cross-country flight to qualify for one of the first Superior Certificates granted by the Royal Aero Club. In November 1911 he fitted it with a 40 h.p. Isaacson radial engine for entry in the British Michelin Cup no. 2 competition, which was restricted to all-British aircraft and pilots.

Prier and Valentine flew the two-seater, No. 58, extensively during September and October 1911 and satisfied the Directors that it was suitable for quantity production with a good prospect in foreign markets. A batch of six, Nos. 71-76, was laid down and the first was specially finished for exhibition at the Paris Salon de l'Aeronautique in December 1911, where it was the sole British representative. All steel parts were burnished and 'blued' to resist rust, aluminium panels were polished to mirror finish and the decking round the cockpits and the wing tread-plates were panelled in plywood. The seats were suspended on wires and, like the cockpit rims, were upholstered in pigskin. A cellulose acetate window was fitted in the sloping front bulkhead to give the passenger a downward view and a sketching board, map case and stowages for binoculars and vacuum flask were also provided. Each cockpit had a Clift compass and the cowling was extended well over the engine to prevent oil being thrown back. A speed of 65 m.p.h. was guaranteed and the price quoted was Fr. 23,750 (about ?950). No. 71 was dispatched from Filton to Paris on 10 December 1911 and No. 72 was shipped to Cuatros Vientos for demonstration to the Spanish Army on 19 December. No. 73 had been sent incomplete to Larkhill in November as a replacement for No. 58 which had crashed on 30 October and No. 74 was rushed out to Issy-les-Moulineaux on 22 December, just before the Filton works closed for Christmas. So when the Paris Salon opened, visitors who had been impressed by the appearance of No. 71 were further delighted by seeing Valentine flying No. 74 round the Eiffel Tower. Valentine was in constant demand for further demonstrations, and on 2 January 1912 made a spectacular arrival with a passenger at St. Cyr in appalling weather just before dusk. A few days later, flying with Capt. Agostini of the Italian Army as passenger, Valentine found his landing baulked by troops, after a long glide with engine off. Unable to restart, he had to swerve through the top of a tree to find a clear space for landing, but, although a branch was carried away, only minor damage resulted. Capt. Agostini was so impressed by this evidence of sturdy construction that an order for two monoplanes arrived from the Italian Government before the end of the week.

Howard Pixton, who had gone to Madrid to demonstrate No. 72, was faced with a more formidable task than Valentine, for Cuatros Vientos is 3,000 ft. above sea level and the Spanish army tests included landing on and taking-off from a freshly ploughed field. The only other competitor, a German, declared this feat to be impossible, and Pixton, too, was worried about the loss of power at this altitude. Then Busteed arrived on Boxkite No. 60 and made short work of the ploughed field test and subsequently both machines were demonstrated to King Alfonso and his staff; the Spanish Government then adopted Bristol aeroplanes as standard equipment for its School of Military Aviation, both aircraft were purchased and two more Prier monoplanes and a further Boxkite were ordered.

When the Spanish trials ended Pixton was summoned to Doberitz, near Berlin, to demonstrate No. 74, which had been shipped to Germany when Valentine returned from Paris. Pixton flew the machine several times before German staff officers at Doberitz and once before the Kaiser at Potsdam. Once when Pixton was challenged by a Rumpler pilot to fly in very gusty conditions he easily out-manoeuvred his rival, but misjudged his height and touched down at high speed, bounced high and then landed safely. Frank Coles, Pixton's mechanic, remarked that this was a test of the undercarriage and was able to warn Pixton before he had time to apologise for an error of judgment, but later a German pilot tried to do the same and came to grief. These demonstrations marked the formation of the Deutsche Bristol-Werke and its associated flying school at Halberstadt, to which No. 74 was handed over on 30 March 1912.