Книги

Putnam

F.Mason

British Bomber since 1914

91

F.Mason - British Bomber since 1914 /Putnam/

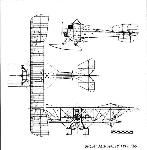

Air Department Type 1000

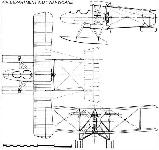

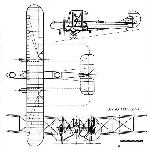

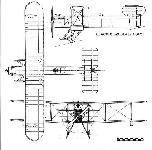

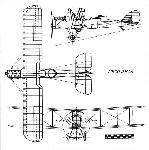

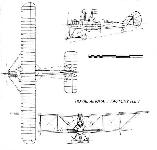

The brainchild of the eccentric engineer, Harris Booth, the massive A.D. 1000 possessed a wing span only marginally less than that of the Wight Twin, but was certainly much heavier. The Admiralty's Air Department was, in 1914, headed by Capt Murray Fraser Sueter, who had been an influential advocate of the aerial bomb and torpedo, and who gave his authority for the design of a large seaplane capable of carrying a single 810 lb 14in naval torpedo or an equivalent weight of bombs.

Booth's design, like Howard Wright's Wight Twin, was of the twin-fuselage configuration, but in other respects differed radically. Unlike the Twin the A.D. 1000 was conceived as a seaplane from the outset, and therein lay the likely reason for its manufacture being undertaken by J Samuel White, whose boat-building factory was equipped to handle large craft and possessed slipways to a sheltered anchorage. Moreover, if nothing else, Booth recognised the importance of providing engines of sufficient power for his huge aeroplane (where others had failed), and selected three 310hp Sunbeam twelve-cylinder water-cooled engines - then the most powerful under development. Thus the A.D. 1000 theoretically possessed more than twice the power of the Wight Twin.

The A.D. 1000 was an all-wooden, four-bay biplane with unequal-span wings, kingposts being used for wire-bracing the upper wing extensions which carried single-acting ailerons; the choice of this layout clearly demanded a very heavy internal wing structure. The big engines were located at the forward ends of the twin fuselages and at the rear of the central nacelle. The latter structure also accommodated the five-man crew, its nose resembling a domestic conservatory with upwards of forty panes of glass, and no concession to drag limitation. The torpedo or bomb load was to be suspended from the lower wing which passed beneath both the fuselages and the central nacelle. The twin main floats were attached by struts to the lower longerons of the fuselages, as were the twin tail floats. There was little to suggest that this float gear would have been adequate to support the enormous machine on any but the calmest water.

The A.D. 1000 was completed at Cowes in the spring of 1915, but was never flown. The Sunbeam engines (later to become the Cossack) were installed with their four-blade propellers. At that time, however, the engines had never flown, and doubt must have been expressed about the efficiency of the cooling system and its extraordinarily cumbersome radiator installation, to say nothing of the float structure's strength. The aircraft was transported to Felixstowe and was almost certainly broken up there in 1916.

Type: Four-bay, five-crew bomber/torpedo-bomber biplane seaplane with one pusher and two tractor engines, central crew nacelle, twin main floats and twin tail floats.

Manufacturer: J. Samuel White & Co. Ltd., Cowes, Isle of Wight, to the design of Harris Booth of the Air Department, Admiralty.

Powerplant: Three 310hp Sunbeam (later named Cossack) 12-cylinder water-cooled inline engines driving four-blade propellers, two driving tractor propellers at the front of the twin fuselages, and one driving a pusher propeller at the rear of the central crew nacelle.

Dimensions: Span, 115ft.

Armament: Designed to carry a bomb load of approximately 800 lb, or one 810 lb 14in Admiralty torpedo.

Prototype: Seven examples ordered, but only one. No 1358, completed and delivered to Felixstowe, but not flown. No production.

The brainchild of the eccentric engineer, Harris Booth, the massive A.D. 1000 possessed a wing span only marginally less than that of the Wight Twin, but was certainly much heavier. The Admiralty's Air Department was, in 1914, headed by Capt Murray Fraser Sueter, who had been an influential advocate of the aerial bomb and torpedo, and who gave his authority for the design of a large seaplane capable of carrying a single 810 lb 14in naval torpedo or an equivalent weight of bombs.

Booth's design, like Howard Wright's Wight Twin, was of the twin-fuselage configuration, but in other respects differed radically. Unlike the Twin the A.D. 1000 was conceived as a seaplane from the outset, and therein lay the likely reason for its manufacture being undertaken by J Samuel White, whose boat-building factory was equipped to handle large craft and possessed slipways to a sheltered anchorage. Moreover, if nothing else, Booth recognised the importance of providing engines of sufficient power for his huge aeroplane (where others had failed), and selected three 310hp Sunbeam twelve-cylinder water-cooled engines - then the most powerful under development. Thus the A.D. 1000 theoretically possessed more than twice the power of the Wight Twin.

The A.D. 1000 was an all-wooden, four-bay biplane with unequal-span wings, kingposts being used for wire-bracing the upper wing extensions which carried single-acting ailerons; the choice of this layout clearly demanded a very heavy internal wing structure. The big engines were located at the forward ends of the twin fuselages and at the rear of the central nacelle. The latter structure also accommodated the five-man crew, its nose resembling a domestic conservatory with upwards of forty panes of glass, and no concession to drag limitation. The torpedo or bomb load was to be suspended from the lower wing which passed beneath both the fuselages and the central nacelle. The twin main floats were attached by struts to the lower longerons of the fuselages, as were the twin tail floats. There was little to suggest that this float gear would have been adequate to support the enormous machine on any but the calmest water.

The A.D. 1000 was completed at Cowes in the spring of 1915, but was never flown. The Sunbeam engines (later to become the Cossack) were installed with their four-blade propellers. At that time, however, the engines had never flown, and doubt must have been expressed about the efficiency of the cooling system and its extraordinarily cumbersome radiator installation, to say nothing of the float structure's strength. The aircraft was transported to Felixstowe and was almost certainly broken up there in 1916.

Type: Four-bay, five-crew bomber/torpedo-bomber biplane seaplane with one pusher and two tractor engines, central crew nacelle, twin main floats and twin tail floats.

Manufacturer: J. Samuel White & Co. Ltd., Cowes, Isle of Wight, to the design of Harris Booth of the Air Department, Admiralty.

Powerplant: Three 310hp Sunbeam (later named Cossack) 12-cylinder water-cooled inline engines driving four-blade propellers, two driving tractor propellers at the front of the twin fuselages, and one driving a pusher propeller at the rear of the central crew nacelle.

Dimensions: Span, 115ft.

Armament: Designed to carry a bomb load of approximately 800 lb, or one 810 lb 14in Admiralty torpedo.

Prototype: Seven examples ordered, but only one. No 1358, completed and delivered to Felixstowe, but not flown. No production.

The A.D. Type 1000, No 1358, moored at East Cowes in 1915. Unlike the Wight Twin seaplane, which abandoned the central crew nacelle, the Type 1000 retained this extraordinary structure until the aircraft was broken up.

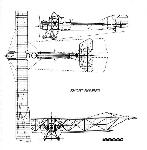

Air Department A.D.I Navyplane

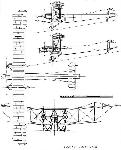

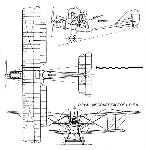

It is sometimes said that Harold Bolas, in effect deputy chief designer at the Admiralty's Air Department, saw part of his job as exerting a restraining influence on the wilder excesses of his immediate senior, Harris Booth. Yet it should be remarked that, although most of Booth's own designs bordered on the grotesque, he was able to use his undoubted influence with the Board of Admiralty when it came to gaining official support for the designs of his subordinates (and he it was who strongly advised Murray Sueter to have such outstanding aeroplanes as the Handley Page O/100, and Sopwith 1 1/2-Strutter, Pup and Camel adopted by the Admiralty when they were still on the drawing board).

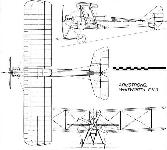

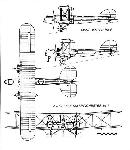

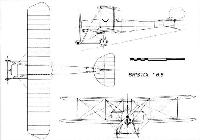

It fell to Harold Bolas to initiate the design early in 1916 of a reconnaissance/bombing seaplane, officially designated the A.D.I, but generally referred to as the Navyplane. As the Air Department's Experimental Construction Depot at Port Victoria, Isle of Grain, was not yet fully equipped to undertake the building of complete aeroplanes, the initial A.D.I design was handed over to the Supermarine Aviation Works at Woolston, Southampton, for the detail design to be completed and construction of a prototype. Working in close collaboration with Bolas, Reginald Mitchell finished the necessary manufacturing drawings in an exceptionally short time, and the prototype, No 9095, was ready for testing by Cdr John Seddon in August.

The A.D.I was a compact two-bay biplane whose two-man crew was accommodated in a finely-contoured lightweight monocoque nacelle located in the wing gap, the experimental air-cooled 150hp Smith Static radial engine driving a four-blade pusher propeller. Twin pontoon-type floats were braced to the nacelle and to the lower wings immediately below the inboard interplane struts. Twin fins and rudders were carried between two pairs of steel tubular tail booms, and the tailplane was mounted above the vertical surfaces. Twin tail floats, each with a water rudder, were attached beneath the lower pair of tail booms. The pilot occupied the rear cockpit, with the observer in the bow position. Two 100 lb bombs were to be carried under the wing centresection.

The ten-cylinder Smith engine, brainchild of an American John W Smith, had evidently attracted the Admiralty's interest, and had shown promise during bench testing. A production order was placed with Heenan & Froude Ltd, but the engine never gave satisfactory performance in the few prototype aircraft in which it was flown.

Little more was heard of the A.D.I until May 1917, when it re-appeared with by an A.R.I engine, designed by W O Bentley. However, although this engine displayed much improved reliability, the A.D.I's performance remained below that demanded by the Admiralty, and six further aircraft originally ordered were not built.

Supermarine had made some efforts to continue development of an enlarged version of the A.D.I, called the Submarine Patrol Seaplane, powered by a 200hp engine, and submitted the design to the Air Board's Seaplane Specification N.3A. Although two prototypes were allotted the serial numbers N24 and N25, work on the project was discontinued when it was decided that the veteran Short Type 184 adequately met the requirements and would continue in service. (In any case the Supermarine aircraft would have been unable to lift the 1,100 lb 18 in torpedo, and did not possess folding wings - both requirements of N.3A.)

Type: Single pusher engine, two-seat, two-bay reconnaissance-bomber biplane with twin main-float undercarriage.

Manufacturer: The Supermarine Aviation Works Ltd, Woolston, Southampton, Hampshire, under the design leadership of Harold Bolas of the Air Department, Admiralty.

Power plant: One 150hp Smith Static ten-cylinder, single-row, air-cooled radial engine driving four-blade pusher propeller; later replaced by a 150hp A.R.I (Admiralty Rotary)

Dimensions: Span: 36ft 0in; length, 27ft 9in; height, 12ft 9in; wing area, 364 sq ft.

Weights (Smith Static engine): Tare, 2,100 lb; all-up, 3,102 lb.

Performance: Max speed, 75 mph at 2,000ft; endurance, 6 hr.

Armament: Provision for one 0.303in Lewis gun on rotatable mounting in nose of nacelle. Provision for bomb load, probably not exceeding 200 lb.

Prototype: One, No. 9095, first flown with Smith Static engine by Lt-Cdr John Seddon RN, in August 1916. Second aircraft. No 9096, was cancelled, as was a batch of five aircraft, N1070-N1074.

It is sometimes said that Harold Bolas, in effect deputy chief designer at the Admiralty's Air Department, saw part of his job as exerting a restraining influence on the wilder excesses of his immediate senior, Harris Booth. Yet it should be remarked that, although most of Booth's own designs bordered on the grotesque, he was able to use his undoubted influence with the Board of Admiralty when it came to gaining official support for the designs of his subordinates (and he it was who strongly advised Murray Sueter to have such outstanding aeroplanes as the Handley Page O/100, and Sopwith 1 1/2-Strutter, Pup and Camel adopted by the Admiralty when they were still on the drawing board).

It fell to Harold Bolas to initiate the design early in 1916 of a reconnaissance/bombing seaplane, officially designated the A.D.I, but generally referred to as the Navyplane. As the Air Department's Experimental Construction Depot at Port Victoria, Isle of Grain, was not yet fully equipped to undertake the building of complete aeroplanes, the initial A.D.I design was handed over to the Supermarine Aviation Works at Woolston, Southampton, for the detail design to be completed and construction of a prototype. Working in close collaboration with Bolas, Reginald Mitchell finished the necessary manufacturing drawings in an exceptionally short time, and the prototype, No 9095, was ready for testing by Cdr John Seddon in August.

The A.D.I was a compact two-bay biplane whose two-man crew was accommodated in a finely-contoured lightweight monocoque nacelle located in the wing gap, the experimental air-cooled 150hp Smith Static radial engine driving a four-blade pusher propeller. Twin pontoon-type floats were braced to the nacelle and to the lower wings immediately below the inboard interplane struts. Twin fins and rudders were carried between two pairs of steel tubular tail booms, and the tailplane was mounted above the vertical surfaces. Twin tail floats, each with a water rudder, were attached beneath the lower pair of tail booms. The pilot occupied the rear cockpit, with the observer in the bow position. Two 100 lb bombs were to be carried under the wing centresection.

The ten-cylinder Smith engine, brainchild of an American John W Smith, had evidently attracted the Admiralty's interest, and had shown promise during bench testing. A production order was placed with Heenan & Froude Ltd, but the engine never gave satisfactory performance in the few prototype aircraft in which it was flown.

Little more was heard of the A.D.I until May 1917, when it re-appeared with by an A.R.I engine, designed by W O Bentley. However, although this engine displayed much improved reliability, the A.D.I's performance remained below that demanded by the Admiralty, and six further aircraft originally ordered were not built.

Supermarine had made some efforts to continue development of an enlarged version of the A.D.I, called the Submarine Patrol Seaplane, powered by a 200hp engine, and submitted the design to the Air Board's Seaplane Specification N.3A. Although two prototypes were allotted the serial numbers N24 and N25, work on the project was discontinued when it was decided that the veteran Short Type 184 adequately met the requirements and would continue in service. (In any case the Supermarine aircraft would have been unable to lift the 1,100 lb 18 in torpedo, and did not possess folding wings - both requirements of N.3A.)

Type: Single pusher engine, two-seat, two-bay reconnaissance-bomber biplane with twin main-float undercarriage.

Manufacturer: The Supermarine Aviation Works Ltd, Woolston, Southampton, Hampshire, under the design leadership of Harold Bolas of the Air Department, Admiralty.

Power plant: One 150hp Smith Static ten-cylinder, single-row, air-cooled radial engine driving four-blade pusher propeller; later replaced by a 150hp A.R.I (Admiralty Rotary)

Dimensions: Span: 36ft 0in; length, 27ft 9in; height, 12ft 9in; wing area, 364 sq ft.

Weights (Smith Static engine): Tare, 2,100 lb; all-up, 3,102 lb.

Performance: Max speed, 75 mph at 2,000ft; endurance, 6 hr.

Armament: Provision for one 0.303in Lewis gun on rotatable mounting in nose of nacelle. Provision for bomb load, probably not exceeding 200 lb.

Prototype: One, No. 9095, first flown with Smith Static engine by Lt-Cdr John Seddon RN, in August 1916. Second aircraft. No 9096, was cancelled, as was a batch of five aircraft, N1070-N1074.

The A.D.I Navy plane. No 9095, at the Supermarine works in 1916 with Cdr John Seddon and Hubert Scott-Payne.The wings were rigged without stagger, but did not fold.

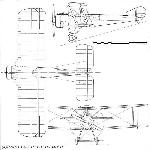

Armstrong, Whitworth F.K.2 and F.K.3

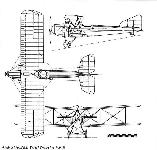

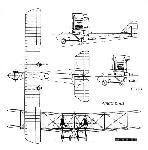

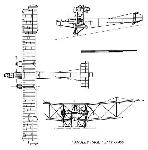

The old-established engineering company of Sir W G Armstrong, Whitworth & Co Ltd had tentatively entered the aircraft industry in 1910 with the rebuilding of a crashed Farman, and two years later began manufacturing ABC engines to the design of Granville Bradshaw. Expansion and diversification in the aircraft business followed in 1913 with airship manufacture at Selby in Yorkshire, and the production of aeroplanes at Gosforth, Newcastle-upon-Tyne. The latter business commenced with the acquisition of the services o f the Dutchman, Frederick Koolhoven, as aeroplane designer.

Early work included War Office contracts for the manufacture of B.E.2As, 2Bs and 2Cs, delivery of which began in 1914, and it was during the production of these aircraft that Koolhoven in March 1915 devised means by which the B.E.2C's structure might be simplified for ease of manufacture. The new design was tendered to the War Office and met with general approval, this leading to the raising of a small exploratory production contract for seven trials aircraft, designated the F.K.2, in August that year. Koolhoven's proposals were vindicated and rewarded by contracts for fairly large-scale production - by the standards of the time although the War Office maintained a stipulation that the production F.K.3 should not compete seriously with the Government Factory's B.E.2C, a policy that would in due course contribute to a serious breakdown in relations between the commercial aircraft manufacturers and the Service authorities.

The F.K.2 differed principally in almost completely eliminating welded joints and complex metal components in the airframe, and featured greater dihedral on the upper wing than on the B.E.2C. The prototype, probably first flown in September or October 1915 by Norman Pratt, was powered by the 70hp Renault, but subsequent aircraft were fitted with 90hp R.A.F. 1A engines. A generally popular and ingenious feature was the oleo-sprung undercarriage, the vertical shock absorbers being set into the sides of the fuselage. The cockpit arrangement of the trials F.K.2s followed that of the B.E.2C in that the pilot occupied the rear position, with the gunner in front; however, owing to the difficulty the gunner experienced in aiming and firing his gun, all subsequent production F.K.3s featured these cockpits reversed, enabling the gunner/observer to provide a more effective defence to the rear.

A single 100 lb or 112 lb bomb could be carried beneath the fuselage, although this precluded the carrying of the gunner owing to the limited engine power available. Alternatively, up to six 16 lb anti-personnel bombs could be attached to underwing racks.

It is said that a temporary shortage of R.A.F. 1A engines led to the fitting of the larger and heavier 120hp Beardmore engine in a number of F.K.3s early in 1916, but this was not considered satisfactory owing largely to a deterioration in handling qualities, and the aircraft reverted to standard when availability of the R.A.F. engine was restored.

Despite returning a slightly better performance than the R.A.F. B.E.2C, the F.K.3 did not see any active service on the Western Front, being delivered instead to No 47 Squadron at Beverley in Yorkshire in March 1916, and accompanying it to Salonika in September that year. Local field reconnaissance work gave place to frequent bombing attacks by the F.K.3s (dubbed Little Acks' by the RFC to distinguish them from the later, larger F.K.8s), particularly against Hudova, while based at Janes.

Nevertheless, the F.K.3 production built up too late for the type's serious consideration for widespread service, and most aircraft were delivered to training units at home, being found to be sufficiently tractable for instruction purposes. By the date of the Armistice none remained with No 47 Squadron, most of its F.K.3s surviving in Palestine and Egypt, while 53 examples were on charge with home training units.

Type: Single-engine, two-seat, two-bay tractor biplane for ground support.

Manufacturers: Sir W G Armstrong, Whitworth & Co., Ltd, Gosforth, Newcastle-upon-Tyne; Hewlett & Blondeau, Ltd., Oak Road, Leagrave, Luton, Beds.

Powerplant: One 90hp R.A.F. 1A or one 105hp R.A.F.IB in-line engine driving four-blade propeller. Some aircraft were fitted temporarily with the 120hp Beardmore engine in 1916.

Structure: All-wood wire-braced construction with dual flying controls and oleo-sprung wheels-and-skid undercarriage.

Dimensions: Span, 40ft 0 5/8in; length, 29ft 0in; height, 11ft 10 3/4in; wing area, 442 sq ft.

Weights (R.A.F.1A engine): Tare, 1,386 lb; all-up, 2,056 lb.

Performance (R.A.F. 1A engine): Max speed, 97 mph at sea level; climb to 5,000ft, 19 min; service ceiling, 12,000ft; endurance, 3 hr.

Armament: One Lewis gun on pillar mounting at the rear of the cockpit; however, when carrying bombs, neither observer nor gun could be carried. Bomb load, one 112 lb or one 100 lb bomb, or up to six 16 lb anti-personnel bombs on external racks.

Prototypes: Seven F.K.2 trials aircraft ordered in April 1915, Nos. 5328-5334, built by Armstrong, Whitworth; first flight by Norman Spratt, late summer 1915.

Production: Total F.K.3s built, 493, excluding the above trials aircraft: Armstrong, Whitworth, 143 (Nos 5504-5553, 5614, 6186-6227, A8091-8140); Hewlett & Blondeau, 350 (A1461-A1510 and B9501-B9800).

Summary of RFC Service: F.K.3s served operationally with No. 47 Squadron, RFC, in Macedonia, and with No. 35 (Reserve) Squadron, RFC, Northolt; served also with No. 31 (Training) Squadron, Schools of Aerial Gunnery, etc.

The old-established engineering company of Sir W G Armstrong, Whitworth & Co Ltd had tentatively entered the aircraft industry in 1910 with the rebuilding of a crashed Farman, and two years later began manufacturing ABC engines to the design of Granville Bradshaw. Expansion and diversification in the aircraft business followed in 1913 with airship manufacture at Selby in Yorkshire, and the production of aeroplanes at Gosforth, Newcastle-upon-Tyne. The latter business commenced with the acquisition of the services o f the Dutchman, Frederick Koolhoven, as aeroplane designer.

Early work included War Office contracts for the manufacture of B.E.2As, 2Bs and 2Cs, delivery of which began in 1914, and it was during the production of these aircraft that Koolhoven in March 1915 devised means by which the B.E.2C's structure might be simplified for ease of manufacture. The new design was tendered to the War Office and met with general approval, this leading to the raising of a small exploratory production contract for seven trials aircraft, designated the F.K.2, in August that year. Koolhoven's proposals were vindicated and rewarded by contracts for fairly large-scale production - by the standards of the time although the War Office maintained a stipulation that the production F.K.3 should not compete seriously with the Government Factory's B.E.2C, a policy that would in due course contribute to a serious breakdown in relations between the commercial aircraft manufacturers and the Service authorities.

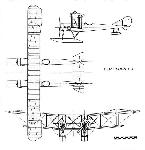

The F.K.2 differed principally in almost completely eliminating welded joints and complex metal components in the airframe, and featured greater dihedral on the upper wing than on the B.E.2C. The prototype, probably first flown in September or October 1915 by Norman Pratt, was powered by the 70hp Renault, but subsequent aircraft were fitted with 90hp R.A.F. 1A engines. A generally popular and ingenious feature was the oleo-sprung undercarriage, the vertical shock absorbers being set into the sides of the fuselage. The cockpit arrangement of the trials F.K.2s followed that of the B.E.2C in that the pilot occupied the rear position, with the gunner in front; however, owing to the difficulty the gunner experienced in aiming and firing his gun, all subsequent production F.K.3s featured these cockpits reversed, enabling the gunner/observer to provide a more effective defence to the rear.

A single 100 lb or 112 lb bomb could be carried beneath the fuselage, although this precluded the carrying of the gunner owing to the limited engine power available. Alternatively, up to six 16 lb anti-personnel bombs could be attached to underwing racks.

It is said that a temporary shortage of R.A.F. 1A engines led to the fitting of the larger and heavier 120hp Beardmore engine in a number of F.K.3s early in 1916, but this was not considered satisfactory owing largely to a deterioration in handling qualities, and the aircraft reverted to standard when availability of the R.A.F. engine was restored.

Despite returning a slightly better performance than the R.A.F. B.E.2C, the F.K.3 did not see any active service on the Western Front, being delivered instead to No 47 Squadron at Beverley in Yorkshire in March 1916, and accompanying it to Salonika in September that year. Local field reconnaissance work gave place to frequent bombing attacks by the F.K.3s (dubbed Little Acks' by the RFC to distinguish them from the later, larger F.K.8s), particularly against Hudova, while based at Janes.

Nevertheless, the F.K.3 production built up too late for the type's serious consideration for widespread service, and most aircraft were delivered to training units at home, being found to be sufficiently tractable for instruction purposes. By the date of the Armistice none remained with No 47 Squadron, most of its F.K.3s surviving in Palestine and Egypt, while 53 examples were on charge with home training units.

Type: Single-engine, two-seat, two-bay tractor biplane for ground support.

Manufacturers: Sir W G Armstrong, Whitworth & Co., Ltd, Gosforth, Newcastle-upon-Tyne; Hewlett & Blondeau, Ltd., Oak Road, Leagrave, Luton, Beds.

Powerplant: One 90hp R.A.F. 1A or one 105hp R.A.F.IB in-line engine driving four-blade propeller. Some aircraft were fitted temporarily with the 120hp Beardmore engine in 1916.

Structure: All-wood wire-braced construction with dual flying controls and oleo-sprung wheels-and-skid undercarriage.

Dimensions: Span, 40ft 0 5/8in; length, 29ft 0in; height, 11ft 10 3/4in; wing area, 442 sq ft.

Weights (R.A.F.1A engine): Tare, 1,386 lb; all-up, 2,056 lb.

Performance (R.A.F. 1A engine): Max speed, 97 mph at sea level; climb to 5,000ft, 19 min; service ceiling, 12,000ft; endurance, 3 hr.

Armament: One Lewis gun on pillar mounting at the rear of the cockpit; however, when carrying bombs, neither observer nor gun could be carried. Bomb load, one 112 lb or one 100 lb bomb, or up to six 16 lb anti-personnel bombs on external racks.

Prototypes: Seven F.K.2 trials aircraft ordered in April 1915, Nos. 5328-5334, built by Armstrong, Whitworth; first flight by Norman Spratt, late summer 1915.

Production: Total F.K.3s built, 493, excluding the above trials aircraft: Armstrong, Whitworth, 143 (Nos 5504-5553, 5614, 6186-6227, A8091-8140); Hewlett & Blondeau, 350 (A1461-A1510 and B9501-B9800).

Summary of RFC Service: F.K.3s served operationally with No. 47 Squadron, RFC, in Macedonia, and with No. 35 (Reserve) Squadron, RFC, Northolt; served also with No. 31 (Training) Squadron, Schools of Aerial Gunnery, etc.

A late-production Hewlett & Blondeau-built F.K.3, B9554, probably in service with a home-based training unit. Note the oleo strut for the undercarriage incorporated into the side of the fuselage.

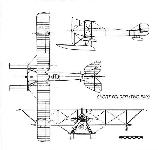

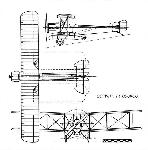

Armstrong, Whitworth F.K.7 and F.K.8

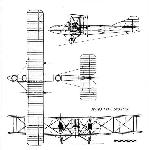

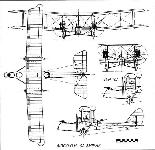

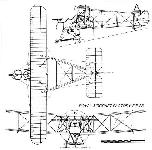

The role of corps reconnaissance must have been one o f the least popular of the duties undertaken by RFC flying personnel during the First World War, and on account of the appalling casualties suffered by the B.E. aircraft over a period of two years, Service pilots tended to be extremely critical of the aeroplanes they were obliged to fly. This was particularly true of the B.E.s themselves, as well as the R.E.8 which was intended to replace them. Frederick Koolhoven, aircraft designer with Sir W G Armstrong, Whitworth Aircraft Ltd, having produced what he considered to be 'an improved version of the B.E.2C with his F.K.3, went further with his bigger and more powerful F.K.8 - predictably known as the 'Big Ack'. As such, the latter was seen to be comparable with the Factory's R.E.8. In terms of performance it was found to be inferior, but this was more than balanced by it being fairly free of handling vices. Moreover, in contrast to the apparent unwillingness to effect improvements in the R.E.8 (for a number of possibly valid reasons), the makers of the F.K.8 went to some effort to improve the features that attracted criticism in their aeroplane.

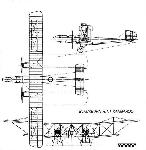

Design of the F.K.8 was orthodox and incorporated the increased strength factors being recommended by the Factory on behalf of the War Office by 1916. Like its predecessor, it was a two bay staggered biplane with ailerons on upper and lower, equal-span wings. Contrary to suggestions that persisted for years, the F.K.8 was powered from the outset by the 160hp Beardmore engine, a powerplant of approximately the same power/weight ratio as the R.E.8's 140hp R.A.F.4A. However the installation of the straight-six, watercooled Beardmore was untidy, with angular cow ling panels and large vertical radiator blocks attached to each side of the nose and angled inwards to meet at a point on the aircraft's centreline above the engine; the provision of cumbersome exhaust manifolds and the triple V-strut undercarriage with oleo struts on the sides of the fuselage all conspired to limit the F.K.8's speed performance. Indeed, the maximum speed of 95 mph at sea level was 5 mph below that considered essential for corps reconnaissance machines, and 8 mph slower than the R.E.8.

Despite these shortcomings, Koolhoven's aeroplane probably became more popular among its pilots, being straightforward and relatively simple to fly, as well as possessing a robust airframe capable of withstanding battle damage.

The prototype, F.K.7 A411, first flew in May 1916, and acceptance tests were flown at Upavon the following month. The first production orders were placed with Armstrong, Whitworth in August, and the first deliveries were made from Gosforth before the year's end, several aircraft joining No 55 Training Squadron at Lilbourne in December. The first examples to fly with a front-line squadron were delivered to No 35 Squadron, which took a full complement to St Omer in France on 25 January 1917. By the end of that fateful April No 35 had been joined by No 2 Squadron, as demands for improvements in the aircraft were already being received by the manufacturers.

Apart from severely restricting the pilot's forward vision, the long, angled radiator honeycomb blocks were inefficient and were replaced by much smaller blocks attached lower on the sides o f the nose. At about the same time the nose cowling was improved in shape, the angular panels giving place to a more rounded profile in side elevation. The crude engine exhaust manifold, whose efflux was found to distort the crew's field of vision through mirage effect, was eventually changed to a conventional pipe which extended aft of the cockpits.

The undercarriage was also criticized as unsatisfactory, and the RFC suggested using components of the Bristol Fighter's plain V-strut gear, a proposal adopted by No 1 Aircraft Depot, where several such conversions were undertaken - until stocks of the Bristol components ran out and resort was made to the use of B.E.2C parts! In due course Armstrong, Whitworth came up with its own improved plain-Y design, still retaining the oleos located in the fuselage sides, but significantly improving the aircraft's performance.

The F.K.8 was ordered in large numbers. Oliver Tapper suggests that the total production amounted to at least 1,652 aircraft, but explains that the exact number may never be known owing to the absence of differentiation between F.K.3s and F.K.8s in some contract documents. Yet, despite this relatively large number of aircraft, the F.K.8 only served on a total of six squadrons in France, and three in the Balkans and Palestine. Three squadrons, based in the United Kingdom, flew the aircraft on home defence and training duties.

Like the R.E.8, the F.K.8 also undertook bombing raids on the Western Front, commencing in September 1917, and later in Macedonia. The aircraft was capable of carrying up to four 65 lb bombs, but more frequently mounted six 40 lb Bourdillon phosphorus weapons, especially when required to lay smokescreens in support of ground forces.

It was while the Big Acks were engaged in bombing operations that two pilots won Victoria Crosses. On 27 March 1918, while returning in the F.K.8 B5773 from a raid during the German offensive on the Western Front, 2/Lieut Alan A McLeod was attacked by a Fokker Dr I triplane, which was quickly shot down by his observer, Lt A W Hammond MC. They were then attacked by seven more Fokkers, of which four were shot down two by McLeod with his front gun. Both crew members were badly wounded, the pilot being hit five times and severely burned when his fuel tank was set on fire. Despite great pain, McLeod climbed out on to the port wing but managed to retain his hold on the control column and, by sideslipping, kept the flames away from the cockpit as he crash landed in No Man's Land, where the two airmen were rescued by British troops. Both miraculously survived, although Hammond lost a leg; McLeod, who was only eighteen years of age, was awarded the Victoria Cross, and Hammond a Bar to his Military Cross.

During a period in the summer of 1918, when F.K.8s were taking part in trials with No 8 Squadron in co-operation with the Army's tanks on the Western Front, the second Victoria Cross was won by a Big Ack pilot. On 10 August, as Capt Ferdinand Maurice Felix West Mc and Lt J A G Haslam (later Gp Capt, MC, DFC) were returning from a bombing raid on German gun batteries, their F.K.8 was attacked at low level by six enemy fighters. Despite Heine hit in both legs, one of which was almost severed, and scarcely conscious owing to excruciating pain and loss of blood, the 22-year-old pilot managed to land in the British lines, yet refused to be taken to hospital until he had passed his vital report to the local tank commander. West's Victoria Cross was gazetted three days before the Armistice, and this officer continued to serve in the RAF until his retirement in March 1946 as an Air Commodore.

The F.K.8 survived in service for a few months after the War, the last Squadron, No 150, being disbanded at Kirec in Greece on 18 September 1919.

Type: Single-engine, two-seat, two-bay tractor biplane for ground support and short-range bombing.

Manufacturers: Sir W.G. Armstrong, Whitworth & Co, Ltd., Gosforth, Newcastle-upon-Type; Angus Sanderson & Co, Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

Powerplant: One 160hp Beardmore six-cylinder water-cooled inline engine driving two-blade propeller. Experimental installations: 150hp R.A.F.4A and 150hp Lorraine Dietrich.

Structure: All-wood wire-braced construction with partial dual flying controls and oleo-sprung undercarriage.

Dimensions: Span, 43ft 6in; length, 31ft 0in; height, 10ft 11in; wing area. 540 sq ft.

Weights: Tare, 1,916 lb; all-up, 2,811 lb.

Performance: Max speed, 94 mph at sea level; climb to 5,000ft, 11 min.; service ceiling, 13,000ft; endurance, 3 hr.

Armament: One forward-firing, synchronized 0.303in Vickers machine gun, and one Lewis or Vickers machine gun on Scarff ring on rear cockpit; provision for bomb load, normally comprising up to six 40 lb, four 65 lb or two 112 lb bombs on underwing racks.

Prototype: One F.K.7 prototype, A411, first flown in May 1916.

Production: Total of 1,652 F.K.8s stated as being delivered to the RFC and RAF prior to 1st September 1918, including 210 probably in component form only. Armstrong, Whitworth, 650 (A2683-A2372, A9980-A9999, B201-B330, B3301-B34OO, B5751-B5850 and C8401-C8650). Angus Sanderson, 600 (C3507-C3706, F7347-F7546 and H4425-H4624). 330 further aircraft were ordered (D5001-D5200, F616-F645 and H4625-H4724) but not all are known to have been completed, and their manufacturers have not been confirmed. Upwards of 40 aircraft were repaired and rebuilt, being re-allocated various isolated B, F, and H-prefixed numbers.

Summary of Service: F.K.8s served operationally with Nos 2, 10, 35, 55 and 82 Squadrons, RFC and RAF, and on tank co-operation trials with No 8 Squadron on the Western Front; with Nos 17, 47 and 150 Squadrons in Macedonia; and with No 142 Squadron in Palestine. They also served with Nos 31, 39 and 98 (Training) Squadrons, No 50 (Home Defence) Squadron, Schools of Army Cooperation, School of Photography, Air Observer and Air Gunnery Schools and other training units.

The role of corps reconnaissance must have been one o f the least popular of the duties undertaken by RFC flying personnel during the First World War, and on account of the appalling casualties suffered by the B.E. aircraft over a period of two years, Service pilots tended to be extremely critical of the aeroplanes they were obliged to fly. This was particularly true of the B.E.s themselves, as well as the R.E.8 which was intended to replace them. Frederick Koolhoven, aircraft designer with Sir W G Armstrong, Whitworth Aircraft Ltd, having produced what he considered to be 'an improved version of the B.E.2C with his F.K.3, went further with his bigger and more powerful F.K.8 - predictably known as the 'Big Ack'. As such, the latter was seen to be comparable with the Factory's R.E.8. In terms of performance it was found to be inferior, but this was more than balanced by it being fairly free of handling vices. Moreover, in contrast to the apparent unwillingness to effect improvements in the R.E.8 (for a number of possibly valid reasons), the makers of the F.K.8 went to some effort to improve the features that attracted criticism in their aeroplane.

Design of the F.K.8 was orthodox and incorporated the increased strength factors being recommended by the Factory on behalf of the War Office by 1916. Like its predecessor, it was a two bay staggered biplane with ailerons on upper and lower, equal-span wings. Contrary to suggestions that persisted for years, the F.K.8 was powered from the outset by the 160hp Beardmore engine, a powerplant of approximately the same power/weight ratio as the R.E.8's 140hp R.A.F.4A. However the installation of the straight-six, watercooled Beardmore was untidy, with angular cow ling panels and large vertical radiator blocks attached to each side of the nose and angled inwards to meet at a point on the aircraft's centreline above the engine; the provision of cumbersome exhaust manifolds and the triple V-strut undercarriage with oleo struts on the sides of the fuselage all conspired to limit the F.K.8's speed performance. Indeed, the maximum speed of 95 mph at sea level was 5 mph below that considered essential for corps reconnaissance machines, and 8 mph slower than the R.E.8.

Despite these shortcomings, Koolhoven's aeroplane probably became more popular among its pilots, being straightforward and relatively simple to fly, as well as possessing a robust airframe capable of withstanding battle damage.

The prototype, F.K.7 A411, first flew in May 1916, and acceptance tests were flown at Upavon the following month. The first production orders were placed with Armstrong, Whitworth in August, and the first deliveries were made from Gosforth before the year's end, several aircraft joining No 55 Training Squadron at Lilbourne in December. The first examples to fly with a front-line squadron were delivered to No 35 Squadron, which took a full complement to St Omer in France on 25 January 1917. By the end of that fateful April No 35 had been joined by No 2 Squadron, as demands for improvements in the aircraft were already being received by the manufacturers.

Apart from severely restricting the pilot's forward vision, the long, angled radiator honeycomb blocks were inefficient and were replaced by much smaller blocks attached lower on the sides o f the nose. At about the same time the nose cowling was improved in shape, the angular panels giving place to a more rounded profile in side elevation. The crude engine exhaust manifold, whose efflux was found to distort the crew's field of vision through mirage effect, was eventually changed to a conventional pipe which extended aft of the cockpits.

The undercarriage was also criticized as unsatisfactory, and the RFC suggested using components of the Bristol Fighter's plain V-strut gear, a proposal adopted by No 1 Aircraft Depot, where several such conversions were undertaken - until stocks of the Bristol components ran out and resort was made to the use of B.E.2C parts! In due course Armstrong, Whitworth came up with its own improved plain-Y design, still retaining the oleos located in the fuselage sides, but significantly improving the aircraft's performance.

The F.K.8 was ordered in large numbers. Oliver Tapper suggests that the total production amounted to at least 1,652 aircraft, but explains that the exact number may never be known owing to the absence of differentiation between F.K.3s and F.K.8s in some contract documents. Yet, despite this relatively large number of aircraft, the F.K.8 only served on a total of six squadrons in France, and three in the Balkans and Palestine. Three squadrons, based in the United Kingdom, flew the aircraft on home defence and training duties.

Like the R.E.8, the F.K.8 also undertook bombing raids on the Western Front, commencing in September 1917, and later in Macedonia. The aircraft was capable of carrying up to four 65 lb bombs, but more frequently mounted six 40 lb Bourdillon phosphorus weapons, especially when required to lay smokescreens in support of ground forces.

It was while the Big Acks were engaged in bombing operations that two pilots won Victoria Crosses. On 27 March 1918, while returning in the F.K.8 B5773 from a raid during the German offensive on the Western Front, 2/Lieut Alan A McLeod was attacked by a Fokker Dr I triplane, which was quickly shot down by his observer, Lt A W Hammond MC. They were then attacked by seven more Fokkers, of which four were shot down two by McLeod with his front gun. Both crew members were badly wounded, the pilot being hit five times and severely burned when his fuel tank was set on fire. Despite great pain, McLeod climbed out on to the port wing but managed to retain his hold on the control column and, by sideslipping, kept the flames away from the cockpit as he crash landed in No Man's Land, where the two airmen were rescued by British troops. Both miraculously survived, although Hammond lost a leg; McLeod, who was only eighteen years of age, was awarded the Victoria Cross, and Hammond a Bar to his Military Cross.

During a period in the summer of 1918, when F.K.8s were taking part in trials with No 8 Squadron in co-operation with the Army's tanks on the Western Front, the second Victoria Cross was won by a Big Ack pilot. On 10 August, as Capt Ferdinand Maurice Felix West Mc and Lt J A G Haslam (later Gp Capt, MC, DFC) were returning from a bombing raid on German gun batteries, their F.K.8 was attacked at low level by six enemy fighters. Despite Heine hit in both legs, one of which was almost severed, and scarcely conscious owing to excruciating pain and loss of blood, the 22-year-old pilot managed to land in the British lines, yet refused to be taken to hospital until he had passed his vital report to the local tank commander. West's Victoria Cross was gazetted three days before the Armistice, and this officer continued to serve in the RAF until his retirement in March 1946 as an Air Commodore.

The F.K.8 survived in service for a few months after the War, the last Squadron, No 150, being disbanded at Kirec in Greece on 18 September 1919.

Type: Single-engine, two-seat, two-bay tractor biplane for ground support and short-range bombing.

Manufacturers: Sir W.G. Armstrong, Whitworth & Co, Ltd., Gosforth, Newcastle-upon-Type; Angus Sanderson & Co, Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

Powerplant: One 160hp Beardmore six-cylinder water-cooled inline engine driving two-blade propeller. Experimental installations: 150hp R.A.F.4A and 150hp Lorraine Dietrich.

Structure: All-wood wire-braced construction with partial dual flying controls and oleo-sprung undercarriage.

Dimensions: Span, 43ft 6in; length, 31ft 0in; height, 10ft 11in; wing area. 540 sq ft.

Weights: Tare, 1,916 lb; all-up, 2,811 lb.

Performance: Max speed, 94 mph at sea level; climb to 5,000ft, 11 min.; service ceiling, 13,000ft; endurance, 3 hr.

Armament: One forward-firing, synchronized 0.303in Vickers machine gun, and one Lewis or Vickers machine gun on Scarff ring on rear cockpit; provision for bomb load, normally comprising up to six 40 lb, four 65 lb or two 112 lb bombs on underwing racks.

Prototype: One F.K.7 prototype, A411, first flown in May 1916.

Production: Total of 1,652 F.K.8s stated as being delivered to the RFC and RAF prior to 1st September 1918, including 210 probably in component form only. Armstrong, Whitworth, 650 (A2683-A2372, A9980-A9999, B201-B330, B3301-B34OO, B5751-B5850 and C8401-C8650). Angus Sanderson, 600 (C3507-C3706, F7347-F7546 and H4425-H4624). 330 further aircraft were ordered (D5001-D5200, F616-F645 and H4625-H4724) but not all are known to have been completed, and their manufacturers have not been confirmed. Upwards of 40 aircraft were repaired and rebuilt, being re-allocated various isolated B, F, and H-prefixed numbers.

Summary of Service: F.K.8s served operationally with Nos 2, 10, 35, 55 and 82 Squadrons, RFC and RAF, and on tank co-operation trials with No 8 Squadron on the Western Front; with Nos 17, 47 and 150 Squadrons in Macedonia; and with No 142 Squadron in Palestine. They also served with Nos 31, 39 and 98 (Training) Squadrons, No 50 (Home Defence) Squadron, Schools of Army Cooperation, School of Photography, Air Observer and Air Gunnery Schools and other training units.

A late production F.K.8, built by Angus Sanderson, F7546. with compact radiators, long exhaust pipe, rounded nose contours and AW-designed plain-V undercarriage.

Avro Type 504 Bombers

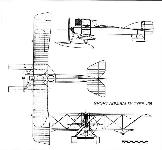

Originating in 1913 as a much improved development of the Type 500, the Avro 504 attracted small pre-War orders by both the War Office and Admiralty, the former contracting for twelve aircraft in the summer of that year, and the latter for a total of five aircraft during the months immediately before the outbreak of war. A small number of RFC 504s accompanied No 5 Squadron to France, but these were used primarily for reconnaissance and gun attacks on ground targets.

The last four of the pre-War 504s ordered by the Admiralty were not completed, and six War Office aircraft were transferred to Admiralty charge. Three of these (Nos 873-875) together with the original naval aircraft (No 179) were formed into a special bombing flight and, flying from Belfort in southeast France on 21 November 1914, Nos 873 (flown by Flt-Lt S V Sippe), 874 (Sqn-Cdr E Featherstone Briggs) and 875 (Flt-Cdr John Tremayne Babington, later Air Marshal Sir John Tremayne KCB, CB, DSO), set out to bomb the airship sheds at Friedrichshafen on the shores of Lake Constance. Each aircraft carried four 20 lb bombs under the fuselage and several bombs scored direct hits on their target, while another hit the hydrogen plant which blew up, causing extensive damage on the airship station. No 874 was shot down, but the other two 504s returned safely. No 873 later served with No 1 Squadron, RNAS, taking part in two bombing attacks on Ostend early in 1915, and hit two U-boats in a raid on a submarine depot near Antwerp on 24 March that year.

The engine most widely used in the Avro 504 was the 80hp Gnome, and considerable orders were placed for subsequent versions of the aircraft, the 504A being the first major production version for the RFC, though relatively few examples were used as bombers. The much-modified 504B was built in quantity for the RNAS, being most easily identified by its large, unbalanced rudder hinged to a long, fixed dorsal fin. Production of the 504C was undertaken by Avro and the Brush Electrical Engineering company. While the majority of 504 variants were employed as training aircraft, conversions to carry bombs were made on an ad hoc basis, and the single-seat 504C was a dedicated antiairship aircraft, being equipped with a Lewis gun and able to carry 20 lb or 65 lb bombs. In place of the front cockpit, which was faired over, there was an extra fuel tank which enabled the aircraft to remain airborne for up to eight hours. A small number of 504As and Bs served at Aboukir and Imbros, several of these being used occasionally as bombers, but primarily for reconnaissance and coastal patrol.

The Avro 504E, also a naval variant but powered by a 100hp Gnome monosoupape, featured cockpits moved further apart to counter the movement of cg caused by installing an extra fuel tank between the cockpits. At least one 504E was equipped to carry light bombs beneath the fuselage, possibly for anti-Zeppelin attack.

Type: Single-engine, two-seat, two-bay tractor biplane modified as light bomber.

Manufacturer: A. V. Roe & Co. Ltd., Clifton Street, Miles Platting, Manchester.

Powerplant: One 80hp Gnome seven-cylinder air-cooled rotary engine driving two-blade propeller.

Structure: All-wood, wire-braced box girder fuselage structure and two-spar wings.

Dimensions: Span, 36ft 0in; length, 29ft 5in; height, 10ft 5in; wing area, 330 sq ft.

Weights: Tare, 924 lb; all-up, 1,574 lb.

Performance: Max speed, 82 mph; climb to 3,500ft, 8 min 30 sec; endurance, 2 hr.

Armament: No gun armament; bomb load normally comprised up to four 20 lb bombs.

Prototype: None. First flight by a bomb-carrying Avro 504 was by Sqn Cdr E. Featherstone Briggs, RNAS, in No 874 during the attack on airship sheds at Friedrichshafen on 21 November 1914; the aircraft was shot down during this flight.

Production: Seven Avro 504s modified for use as bombers by the RNAS, Nos. 179 and 873-878. Served operationally with RNAS. Eastchurch Squadron, Special Bombing Flight, RNAS, and No 1 Squadron, RNAS.

Originating in 1913 as a much improved development of the Type 500, the Avro 504 attracted small pre-War orders by both the War Office and Admiralty, the former contracting for twelve aircraft in the summer of that year, and the latter for a total of five aircraft during the months immediately before the outbreak of war. A small number of RFC 504s accompanied No 5 Squadron to France, but these were used primarily for reconnaissance and gun attacks on ground targets.

The last four of the pre-War 504s ordered by the Admiralty were not completed, and six War Office aircraft were transferred to Admiralty charge. Three of these (Nos 873-875) together with the original naval aircraft (No 179) were formed into a special bombing flight and, flying from Belfort in southeast France on 21 November 1914, Nos 873 (flown by Flt-Lt S V Sippe), 874 (Sqn-Cdr E Featherstone Briggs) and 875 (Flt-Cdr John Tremayne Babington, later Air Marshal Sir John Tremayne KCB, CB, DSO), set out to bomb the airship sheds at Friedrichshafen on the shores of Lake Constance. Each aircraft carried four 20 lb bombs under the fuselage and several bombs scored direct hits on their target, while another hit the hydrogen plant which blew up, causing extensive damage on the airship station. No 874 was shot down, but the other two 504s returned safely. No 873 later served with No 1 Squadron, RNAS, taking part in two bombing attacks on Ostend early in 1915, and hit two U-boats in a raid on a submarine depot near Antwerp on 24 March that year.

The engine most widely used in the Avro 504 was the 80hp Gnome, and considerable orders were placed for subsequent versions of the aircraft, the 504A being the first major production version for the RFC, though relatively few examples were used as bombers. The much-modified 504B was built in quantity for the RNAS, being most easily identified by its large, unbalanced rudder hinged to a long, fixed dorsal fin. Production of the 504C was undertaken by Avro and the Brush Electrical Engineering company. While the majority of 504 variants were employed as training aircraft, conversions to carry bombs were made on an ad hoc basis, and the single-seat 504C was a dedicated antiairship aircraft, being equipped with a Lewis gun and able to carry 20 lb or 65 lb bombs. In place of the front cockpit, which was faired over, there was an extra fuel tank which enabled the aircraft to remain airborne for up to eight hours. A small number of 504As and Bs served at Aboukir and Imbros, several of these being used occasionally as bombers, but primarily for reconnaissance and coastal patrol.

The Avro 504E, also a naval variant but powered by a 100hp Gnome monosoupape, featured cockpits moved further apart to counter the movement of cg caused by installing an extra fuel tank between the cockpits. At least one 504E was equipped to carry light bombs beneath the fuselage, possibly for anti-Zeppelin attack.

Type: Single-engine, two-seat, two-bay tractor biplane modified as light bomber.

Manufacturer: A. V. Roe & Co. Ltd., Clifton Street, Miles Platting, Manchester.

Powerplant: One 80hp Gnome seven-cylinder air-cooled rotary engine driving two-blade propeller.

Structure: All-wood, wire-braced box girder fuselage structure and two-spar wings.

Dimensions: Span, 36ft 0in; length, 29ft 5in; height, 10ft 5in; wing area, 330 sq ft.

Weights: Tare, 924 lb; all-up, 1,574 lb.

Performance: Max speed, 82 mph; climb to 3,500ft, 8 min 30 sec; endurance, 2 hr.

Armament: No gun armament; bomb load normally comprised up to four 20 lb bombs.

Prototype: None. First flight by a bomb-carrying Avro 504 was by Sqn Cdr E. Featherstone Briggs, RNAS, in No 874 during the attack on airship sheds at Friedrichshafen on 21 November 1914; the aircraft was shot down during this flight.

Production: Seven Avro 504s modified for use as bombers by the RNAS, Nos. 179 and 873-878. Served operationally with RNAS. Eastchurch Squadron, Special Bombing Flight, RNAS, and No 1 Squadron, RNAS.

Shown at Belfort, the three Avro 504 single-seat bombers which attacked the Zeppelin works at Friedrichshafen on 21 November 1914, from left to right, Nos 873, 875 and 874. A fourth, No 179 (flown by Flt Sub-Lt R P Cannon) broke its tail skid and was unable to take part in the raid. Just visible under the fuselage of No 873 are its four 20lb bombs, carried for the attack.

No 3315 was an Avro 504C single-seat bomber, built by The Brush Electrical Engineering Co Ltd, Loughborough, and is shown carrying a 65lb bomb under the fuselage. Note the low aspect ratio fin and unbalanced rudder, favoured by the Admiralty on its later 504s.

Avro Type 519

The Avro Type 519 appears to have been a contemporary of the Grahame-White Type 18 and, like that aeroplane, very little is known about it. By a process of elimination, it seems certain that the Type 519 was intended as a possible bomber, and was evidently an attempt to adapt the Avro Type 510 'Round Britain' racing seaplane of 1914 for military consideration. (Although the 1914 race had been cancelled on the outbreak of war, the Admiralty had purchased the prototype and five further examples.)

The Type 519 retained the earlier aircraft's 150hp Sunbeam Nubian watercooled engine as well as similar two-bay wings of unequal span. The fuselage was generally similar, but was faired to incorporate curved upper decking and raised headrest fairings aft of the cockpits. The wheel-and-skid undercarriage with oleo struts was reminiscent of that on the Avro 504. In order to meet naval storage requirements, provision was made to fold the wings.

The design drawings, prepared by Roy Chadwick and H E Broadsmith, met with interest at the Admiralty and War Office to the extent that Avro received orders for four aircraft - two single-seat Type 519s for the RNAS and two two-seat Type 519As for the RFC; the latter featured fixed wings and a plain V-strut undercarriage without the central skid.

All four aircraft are believed to have been delivered to Farnborough by May 1916 for trials, but it is said that they did not meet the Service strength requirements with the Nubian engine, and their ultimate fate is not known.

Type: Single-engine, single- and two-seat, two-bay biplane (probably intended as experimental bomber).

Manufacturer: A Y Roe & Co Ltd, Miles Platting, Manchester.

Powerplant: One 150hp Sunbeam Nubian eight-cylinder, water-cooled, in-line engine driving two-blade propeller.

Dimensions: Span (Type 510), 63ft 0in.

Performance: Max speed, approx 76 mph at sea level.

Armament: No gun armament; provision for bomb load, unknown.

Prototypes: Four; two Type 519s for Admiralty, Nos 8440 and 8441, and two Type 519As for War Office, Nos 1614 and 1615.

The Avro Type 519 appears to have been a contemporary of the Grahame-White Type 18 and, like that aeroplane, very little is known about it. By a process of elimination, it seems certain that the Type 519 was intended as a possible bomber, and was evidently an attempt to adapt the Avro Type 510 'Round Britain' racing seaplane of 1914 for military consideration. (Although the 1914 race had been cancelled on the outbreak of war, the Admiralty had purchased the prototype and five further examples.)

The Type 519 retained the earlier aircraft's 150hp Sunbeam Nubian watercooled engine as well as similar two-bay wings of unequal span. The fuselage was generally similar, but was faired to incorporate curved upper decking and raised headrest fairings aft of the cockpits. The wheel-and-skid undercarriage with oleo struts was reminiscent of that on the Avro 504. In order to meet naval storage requirements, provision was made to fold the wings.

The design drawings, prepared by Roy Chadwick and H E Broadsmith, met with interest at the Admiralty and War Office to the extent that Avro received orders for four aircraft - two single-seat Type 519s for the RNAS and two two-seat Type 519As for the RFC; the latter featured fixed wings and a plain V-strut undercarriage without the central skid.

All four aircraft are believed to have been delivered to Farnborough by May 1916 for trials, but it is said that they did not meet the Service strength requirements with the Nubian engine, and their ultimate fate is not known.

Type: Single-engine, single- and two-seat, two-bay biplane (probably intended as experimental bomber).

Manufacturer: A Y Roe & Co Ltd, Miles Platting, Manchester.

Powerplant: One 150hp Sunbeam Nubian eight-cylinder, water-cooled, in-line engine driving two-blade propeller.

Dimensions: Span (Type 510), 63ft 0in.

Performance: Max speed, approx 76 mph at sea level.

Armament: No gun armament; provision for bomb load, unknown.

Prototypes: Four; two Type 519s for Admiralty, Nos 8440 and 8441, and two Type 519As for War Office, Nos 1614 and 1615.

The first Admiralty single-seat Type 519, No 8440, in Avro's new erecting shops at Hamble in May 1916.

Avro Type 528

Little is known of the Avro Type 528, a single-engine, three-bay biplane whose construction at Miles Platting is said to have followed immediately after the Type 523A Pike in the late summer of 1916. It was covered by Avro Works No 2350 and only one example was built; however, it has been suggested that two serial numbers, A316 and A317, allocated to A V Roe by the Admiralty, may have been allocated to this type, and that a second aircraft was planned, but cancelled.

Powered by a 225hp Sunbeam driving a four-blade propeller, the Type 528 was designed as a bomber, its bombs being carried in two nacelles on the lower wing, inboard of the inner pair of interplane struts. Bearing in mind that the aircraft was in fact larger than the twin-engine Pike with 150hp Green engines, the bomb load must have been relatively small, and in no way comparable with that of the successful Short Type 184. The Avro aircraft also featured folding wings.

The Sunbeam engine installation, though itself neatly cowled, was compromised by the attachment of two large vertical radiators on either side of the front fuselage immediately forward of the pilot's cockpit, a location that must have severely restricted his view, further limited by the bomb containers on the lower wings.

Few details have survived of the aircraft, and the date of first flight - probably during the autumn of 1916 - is not known.

Type: Single-engine, two-seat, three-bay biplane experimental light bomber.

Manufacturer: A V Roe & Co Ltd., Miles Platting, Manchester, and Hamble, Hampshire.

Powerplant: One 225hp Sunbeam eight-cylinder water-cooled in-line engine driving four-blade propeller.

Dimensions: Span, approx 65ft.

Weights and Performance: No details traced.

Armament: Provision for a single 0.303in Lewis gun on rear cockpit; light bomb load carried in nacelles on lower wings.

Prototype: One only (serial number and first flight date not known)

Little is known of the Avro Type 528, a single-engine, three-bay biplane whose construction at Miles Platting is said to have followed immediately after the Type 523A Pike in the late summer of 1916. It was covered by Avro Works No 2350 and only one example was built; however, it has been suggested that two serial numbers, A316 and A317, allocated to A V Roe by the Admiralty, may have been allocated to this type, and that a second aircraft was planned, but cancelled.

Powered by a 225hp Sunbeam driving a four-blade propeller, the Type 528 was designed as a bomber, its bombs being carried in two nacelles on the lower wing, inboard of the inner pair of interplane struts. Bearing in mind that the aircraft was in fact larger than the twin-engine Pike with 150hp Green engines, the bomb load must have been relatively small, and in no way comparable with that of the successful Short Type 184. The Avro aircraft also featured folding wings.

The Sunbeam engine installation, though itself neatly cowled, was compromised by the attachment of two large vertical radiators on either side of the front fuselage immediately forward of the pilot's cockpit, a location that must have severely restricted his view, further limited by the bomb containers on the lower wings.

Few details have survived of the aircraft, and the date of first flight - probably during the autumn of 1916 - is not known.

Type: Single-engine, two-seat, three-bay biplane experimental light bomber.

Manufacturer: A V Roe & Co Ltd., Miles Platting, Manchester, and Hamble, Hampshire.

Powerplant: One 225hp Sunbeam eight-cylinder water-cooled in-line engine driving four-blade propeller.

Dimensions: Span, approx 65ft.

Weights and Performance: No details traced.

Armament: Provision for a single 0.303in Lewis gun on rear cockpit; light bomb load carried in nacelles on lower wings.

Prototype: One only (serial number and first flight date not known)

Avro Type 523 Pike

Designed by Roy Chadwick to the Royal Aircraft factory's Specification Type VII of 1915, the Avro Type 523 Pike represented a realistic approach to the War Office's demand for a night bomber, although it must be said that the Army's attitude at that time towards the need for large bombing aircraft was less than enthusiastic, and was probably influenced more by a determination to keep abreast of the Admiralty's partisan assumption of the strategic bombing role.

The Pike was a fairly large three-bay biplane with equal-span wings, and with a crew of three, comprising pilot, and nose and midships gunners. The handed 160hp Sunbeam Nubian engines were located at mid-gap with frontal car-type radiators and driving pusher propellers through extension shafts so as to clear the wing trailing edges. Ailerons were fitted to upper and lower wings. The bomb load was to be carried internally in the fuselage with horizontal tier stowage.

The Type 523 was assembled at Avro's newly opened works at Hamble in Hampshire after manufacture at the Manchester factory early in 1916. Unfortunately, despite being designed to a Factory specification, neither the Admiralty nor War Office expressed tangible interest in the Pike, with superior bombers already ordered into production.

On the other hand the Avro company itself undertook further development, producing the Type 523A with 150hp Green engines driving tractor propellers, and later proposing the 523B with 200hp Sunbeams and the 523C with 190hp Rolls-Royce Falcon engines. Neither of the latter came to be built, but their design provided much experience in the evolution of the Type 529 and 533 Manchester bombers. Both the Type 523 and 523A continued to fly at Hamble until 1918.

The Type 523 Pike gained small notoriety when, on one occasion during an early test flight the pilot, Fred Raynham, discovered that the cg was too far aft to permit throttling back to land. The situation was saved when R H Dobson (later Sir Roy, CBE, and Chairman of the Hawker Siddeley Group), who was occupying the midships gunner's cockpit, climbed out and made his way along the top of the fuselage to transfer his weight to the front gunner's position. With the cg restored to manageable limits, Raynham was able to throttle back without the danger of stalling.

Type: Twin-engine, three-crew, three-bay biplane day/night bomber.

Manufacturer: A. V. Roe and Co. Ltd., Miles Platting, Manchester.

Powerplant: Type 523. Two 160hp Sunbeam Nubian water-cooled, in-line engines driving handed two-blade pusher propellers. Type 523A. Two 150hp Green water-cooled, in-line engines driving unhanded two-blade tractor propellers.

Dimensions: Span, 60ft 0in; length, 39ft 1in; height, 11ft 8in; wing area, 815 sq ft.

Weights (Type 523): Tare, 4,000 lb; all-up, 6,064 lb.

Performance (Type 523): Max speed, 97 mph; climb to 10,000ft, 27 min; endurance, 7 hr.

Armament: Provision for single Lewis machine guns on nose and midships gunners' cockpits with Scarff rings. Internal, horizontal-tier stowage of two 100 lb or 112 lb bombs.

Avro Type 529

A natural development of the Avro 523A Pike, the Type 529 retained the same basic configuration, being a slightly larger three-bay, twin-engine biplane with parallel-chord, unstaggered wings. Suitably impressed by the choice of more powerful engines and a potential ability to lift a worthwhile weight of bombs over a range of about 400 miles, the Admiralty ordered two prototypes in 1916, allocating the serials 3694 and 3695.

Powered by two 190hp Rolls-Royce Falcon engines, the first aircraft was flown at Hamble in April 1917, having been built entirely at Manchester. The engines, mounted at mid-gap, were uncowled and drove four-blade propellers, a single 140-gallon fuel tank being situated in the centre fuselage. The undercarriage was similar to that of the Pike, and ailerons were again fitted to both upper and lower wings.

The wings of the Type 529 were, on the insistance of the Admiralty, capable of being folded, a feature that dictated a considerable reduction in the tailplane and elevator areas, and this adversely affected the already poor longitudinal control and stability. Directional control, however, was markedly improved by adopting an enlarged rudder (somewhat of the same shape as the Avro 504's famous 'comma' silhouette).

It is likely that the first aircraft was never intended for more than handling evaluation, and in this respect it was generally regarded as satisfactory in most respects, being capable of being flown straight and level on one engine; the elevator control was however sharply criticised. With the large fuel tank in the fuselage, bombs were probably not capable of being carried.

The second aircraft, termed the Type 529A, was flown at Hamble in October 1917, and differed from the first in being powered by two 230hp Galloway-built BHP engines, completely cowled in nacelles located directly on the lower wings, driving two-blade handed propellers. Each nacelle accommodated a 60-gallon fuel tank for its engine, a small wind-driven pump supplying fuel to a 10-gallon gravity tank under the top wing above the engine.

Removal of the fuel to the nacelles allowed the centre fuselage between the wing spars to incorporate a bomb bay in which up to twenty 50 lb HE RL bombs could be stowed, suspended vertically from circumferential rings round their noses. However, owing to the arrangement of the stowage beams, it was not possible to carry fewer, heavier bombs.

The Type 529A carried a three-man crew comprising pilot, midships gunner and nose gunner, the last also being charged with bomb aiming; communications between him and the pilot was by means of a speaking tube. An unusual feature of the aircraft was the provision of dual controls in the midships gunner's cockpit.

There seems little doubt but that the Avro 529A was designed to perform a bombing role (that of a medium bomber over moderate ranges) whose requirement steadily disappeared with the approaching deliveries of the Handley Page O/400, an aircraft that promised to be so highly adaptable in terms of fuel and bomb load that the need for a relatively specialised bomber with the limited capabilities of the Avro 529 had become superfluous by the time the second example flew; accordingly it never progressed beyond the experimental stage.

Type: Twin-engine, three-crew, three-bay biplane medium bomber.

Manufacturer: A. V. Roe & Co. Ltd., Clifton Street, Miles Platting, Manchester, and Hamble Aerodrome, Southampton, Hampshire.

Powerplant: Type 529. Two 190hp Rolls-Royce Falcon I watercooled in-line engines driving handed four-blade tractor propellers. Type 529A. Two 230hp B.H.P. (Galloway-built) water-cooled inline engines driving two-blade tractor propellers.

Structure: All-wood, wire-braced box-girder fuselage and two-spar, three-bay folding wings; dual controls in midships gunner's cockpit.

Dimensions: Type 529. Span, 63ft 0in (Type 529A, 64ft 1in); length, 39ft 8in; height, 13ft 0in; wing area, 922.5 sq ft (Type 529A, 910 sq ft).

Weights: Type 529. Tare, 4,736 lb; all-up, 6,309 lb. Type 529A. Tare, 4,361 lb; all-up, 7,135 lb.

Performance: Type 529. Max speed, 95 mph at sea level; climb to 10,000ft, 21 min 40 sec; service ceiling, 13,500ft; endurance, 5 hr. Type 529A. Max speed, 116 mph at sea level; climb to 10,000ft, 17 min 20 sec; service ceiling, 17,500ft; endurance, 5 hr.

Armament: Single 0.303in Lewis machine guns with Scarff rings on nose and midships gunners' cockpits. Type 529A could carry up to twenty 50 lb bombs in mid-fuselage bay, suspended vertically (nose up).

Prototypes: One Type 529, No 3694, first flown at Hamble in April 1917. One Type 529A, No 3695, first flown in October 1917. No production. (Both prototypes stated to have crashed while on test at Martlesham Heath in 1918.)

Designed by Roy Chadwick to the Royal Aircraft factory's Specification Type VII of 1915, the Avro Type 523 Pike represented a realistic approach to the War Office's demand for a night bomber, although it must be said that the Army's attitude at that time towards the need for large bombing aircraft was less than enthusiastic, and was probably influenced more by a determination to keep abreast of the Admiralty's partisan assumption of the strategic bombing role.

The Pike was a fairly large three-bay biplane with equal-span wings, and with a crew of three, comprising pilot, and nose and midships gunners. The handed 160hp Sunbeam Nubian engines were located at mid-gap with frontal car-type radiators and driving pusher propellers through extension shafts so as to clear the wing trailing edges. Ailerons were fitted to upper and lower wings. The bomb load was to be carried internally in the fuselage with horizontal tier stowage.

The Type 523 was assembled at Avro's newly opened works at Hamble in Hampshire after manufacture at the Manchester factory early in 1916. Unfortunately, despite being designed to a Factory specification, neither the Admiralty nor War Office expressed tangible interest in the Pike, with superior bombers already ordered into production.

On the other hand the Avro company itself undertook further development, producing the Type 523A with 150hp Green engines driving tractor propellers, and later proposing the 523B with 200hp Sunbeams and the 523C with 190hp Rolls-Royce Falcon engines. Neither of the latter came to be built, but their design provided much experience in the evolution of the Type 529 and 533 Manchester bombers. Both the Type 523 and 523A continued to fly at Hamble until 1918.

The Type 523 Pike gained small notoriety when, on one occasion during an early test flight the pilot, Fred Raynham, discovered that the cg was too far aft to permit throttling back to land. The situation was saved when R H Dobson (later Sir Roy, CBE, and Chairman of the Hawker Siddeley Group), who was occupying the midships gunner's cockpit, climbed out and made his way along the top of the fuselage to transfer his weight to the front gunner's position. With the cg restored to manageable limits, Raynham was able to throttle back without the danger of stalling.

Type: Twin-engine, three-crew, three-bay biplane day/night bomber.

Manufacturer: A. V. Roe and Co. Ltd., Miles Platting, Manchester.

Powerplant: Type 523. Two 160hp Sunbeam Nubian water-cooled, in-line engines driving handed two-blade pusher propellers. Type 523A. Two 150hp Green water-cooled, in-line engines driving unhanded two-blade tractor propellers.

Dimensions: Span, 60ft 0in; length, 39ft 1in; height, 11ft 8in; wing area, 815 sq ft.

Weights (Type 523): Tare, 4,000 lb; all-up, 6,064 lb.

Performance (Type 523): Max speed, 97 mph; climb to 10,000ft, 27 min; endurance, 7 hr.

Armament: Provision for single Lewis machine guns on nose and midships gunners' cockpits with Scarff rings. Internal, horizontal-tier stowage of two 100 lb or 112 lb bombs.

Avro Type 529

A natural development of the Avro 523A Pike, the Type 529 retained the same basic configuration, being a slightly larger three-bay, twin-engine biplane with parallel-chord, unstaggered wings. Suitably impressed by the choice of more powerful engines and a potential ability to lift a worthwhile weight of bombs over a range of about 400 miles, the Admiralty ordered two prototypes in 1916, allocating the serials 3694 and 3695.

Powered by two 190hp Rolls-Royce Falcon engines, the first aircraft was flown at Hamble in April 1917, having been built entirely at Manchester. The engines, mounted at mid-gap, were uncowled and drove four-blade propellers, a single 140-gallon fuel tank being situated in the centre fuselage. The undercarriage was similar to that of the Pike, and ailerons were again fitted to both upper and lower wings.

The wings of the Type 529 were, on the insistance of the Admiralty, capable of being folded, a feature that dictated a considerable reduction in the tailplane and elevator areas, and this adversely affected the already poor longitudinal control and stability. Directional control, however, was markedly improved by adopting an enlarged rudder (somewhat of the same shape as the Avro 504's famous 'comma' silhouette).

It is likely that the first aircraft was never intended for more than handling evaluation, and in this respect it was generally regarded as satisfactory in most respects, being capable of being flown straight and level on one engine; the elevator control was however sharply criticised. With the large fuel tank in the fuselage, bombs were probably not capable of being carried.

The second aircraft, termed the Type 529A, was flown at Hamble in October 1917, and differed from the first in being powered by two 230hp Galloway-built BHP engines, completely cowled in nacelles located directly on the lower wings, driving two-blade handed propellers. Each nacelle accommodated a 60-gallon fuel tank for its engine, a small wind-driven pump supplying fuel to a 10-gallon gravity tank under the top wing above the engine.

Removal of the fuel to the nacelles allowed the centre fuselage between the wing spars to incorporate a bomb bay in which up to twenty 50 lb HE RL bombs could be stowed, suspended vertically from circumferential rings round their noses. However, owing to the arrangement of the stowage beams, it was not possible to carry fewer, heavier bombs.

The Type 529A carried a three-man crew comprising pilot, midships gunner and nose gunner, the last also being charged with bomb aiming; communications between him and the pilot was by means of a speaking tube. An unusual feature of the aircraft was the provision of dual controls in the midships gunner's cockpit.

There seems little doubt but that the Avro 529A was designed to perform a bombing role (that of a medium bomber over moderate ranges) whose requirement steadily disappeared with the approaching deliveries of the Handley Page O/400, an aircraft that promised to be so highly adaptable in terms of fuel and bomb load that the need for a relatively specialised bomber with the limited capabilities of the Avro 529 had become superfluous by the time the second example flew; accordingly it never progressed beyond the experimental stage.

Type: Twin-engine, three-crew, three-bay biplane medium bomber.

Manufacturer: A. V. Roe & Co. Ltd., Clifton Street, Miles Platting, Manchester, and Hamble Aerodrome, Southampton, Hampshire.

Powerplant: Type 529. Two 190hp Rolls-Royce Falcon I watercooled in-line engines driving handed four-blade tractor propellers. Type 529A. Two 230hp B.H.P. (Galloway-built) water-cooled inline engines driving two-blade tractor propellers.

Structure: All-wood, wire-braced box-girder fuselage and two-spar, three-bay folding wings; dual controls in midships gunner's cockpit.

Dimensions: Type 529. Span, 63ft 0in (Type 529A, 64ft 1in); length, 39ft 8in; height, 13ft 0in; wing area, 922.5 sq ft (Type 529A, 910 sq ft).

Weights: Type 529. Tare, 4,736 lb; all-up, 6,309 lb. Type 529A. Tare, 4,361 lb; all-up, 7,135 lb.