Книги

Centennial Perspective

J.Herris, T.Phillips

Fokker Aircraft of WWI. Vol.4: V.1-V.8, F.I & Dr.I

236

J.Herris, T.Phillips - Fokker Aircraft of WWI. Vol.4: V.1-V.8, F.I & Dr.I /Centennial Perspective/ (54)

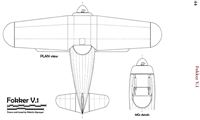

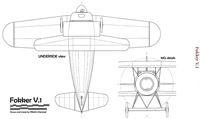

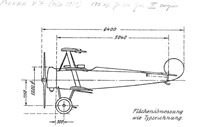

Fokker V.1

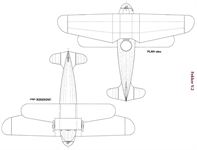

The Fokker V.1 was the first cantilever design and came out in December 1916. Testing started in early 1917. The wooden-sheathed wings had two spars and their cantilever design eliminated the need for bracing wires with their associated significant drag. The relatively small lower wings in a sesquiplane configuration had adjustable incidence.

The V.1, whose factory work number was probably 1458, was equipped with a captured 110 hp French Le Rhone rotary engine. Originally the internal factory designation of this prototype followed their 'D' series designations as the D.III, but was later redesignated V.1; the 'V' stood for Verspannunglos or cantilever. Some sources state it was for Versuch, or test.

Instead of normal control surfaces, the V.1 had rotating wingtips instead of ailerons, a rotating vertical tail tip instead of a normal rudder, and fully moving horizontal tail without fixed surfaces. No production aircraft of the time used rotating wingtips and rudder tips. Two machine guns were fitted.

With the V.1, Fokker tried to apply all available aerodynamic knowledge and the V.1 was very advanced for its time. Despite its good performance, the V.1 was not awarded a production contract for reasons that are not documented. Certainly the round fuselage obstructed downward vision.

After flight testing the V.1 was modified; the vertical stabilizer was slightly enlarged and raised and the angle of attack of the lower wing was decreased.

Fokker V.1 Specifications

Engine: 110 hp Le Rhone

Fuel: 75 L fuel & 10 L oil

Wing: Span Upper 8.60 m

Wing area 17.0 m2

General: Length 5.90 m

Height 2.70 m

Empty Weight 442 kg

Loaded Weight 563 kg

Power to Wt. Ratio Empty 4.02 kg/hp

Maximum Speed: 180 km/h

Climb: 1000 m 2.5 min

2000 m 6 min

3000 m 11 min

4000 m 19 min

5000 m 30 min

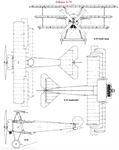

Fokker V.2

The Fokker V.2 was a more powerful development of the V.1. Powered by the 160 hp Mercedes D.III engine, the larger and more powerful V.2 was built in March 1917, when testing also started.

Originally the V.2 was known by its factory designation of D.IV, (work number 1539), but Fokker later changed its factory designation to V.2 to avoid confusion with the military 'D' designation for fighters.

The wings were structurally similar to those of the V.1 and were somewhat larger. From the start the V.2 had the changes made to the V.1 after its test flights; that is, reduced angle of attack of the lower wing and higher movable rudder with larger fixed surfaces. Again two machine guns were fitted.

As with the V.1, great attention was paid to aerodynamic streamlining. The Mercedes engine and Windhoff radiator were completely covered and a large propeller spinner was fitted.

Despite the additional engine power the anticipated performance improvement did not materialize. Maximum speed increased by 10 km/h but climb rate actually decreased because the V.2 was much heavier than the V.1. Again the prototype was not selected for production.

Fokker V.2 Specifications

Engine: 160 hp Mercedes D.III

Fuel: 85 L fuel &5 L oil

Wing: Span Upper 9.30 m

Wing area 22.0 m2

General: Length 6.60 m

Height 2.94 m

Empty Weight 663 kg

Loaded Weight 921 kg

Power to Wt. Ratio Empty 4.14kg/hp

Maximum Speed: 190 km/h

Climb: 1000 m 3 min

2000 m 9 min

3000 m 16 min

4000 m 29 min

5000 m 47 min

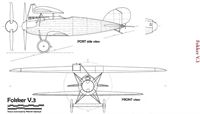

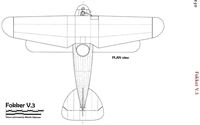

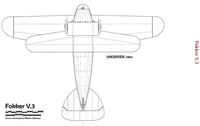

Fokker V.3

The Fokker V.3 (work number 1610) followed the V.2 in May 1917. It was ordered on May 2, 1917 under the factory designation D.VII; that was later changed to V.3 to avoid confusion with the military designation for fighters. Like the V.2 it was powered by a 160 hp Mercedes D.III engine and the two aircraft were nearly identical in size, weight, and performance.

The V.3 had more conventional tail surfaces than the V.2 based on the Albatros D.III to improve flying qualities but retained the rotating wingtips. Two machine guns were designed to be fitted.

The V3 had less streamlined engine and radiator installations than the V.2, likely to improve reliability and maintenance in the field. Nevertheless its performance did not suffer. Like the V.1 and V.2 its round, streamlined fuselage was wide and obstructed the pilots' downward view.

Also like the V.1 and V.2, the V.3 was not given a production order.

Future Fokker prototypes used a thinner, lighter, more advanced cantilever wooden wing design and eliminated the fuselage stringers to simplify construction and improve downward visibility.

Fokker V.3 Specifications

Engine: 160 hp Mercedes D.III

Fuel: 85 L fuel &5 L oil

Wing: Span Upper 9.20 m

Wing area 22.0 m2

General: Length 6.60 m

Height 2.94 m

Empty Weight 680 kg

Loaded Weight 938 kg

Power to Wt. Ratio Empty 4.25 kg/hp

Maximum Speed: 190 km/h

Climb: 1000 m 3.5 min

2000 m 9.5 min

3000 m 17.5 min

4000 m 32 min

5000 m 50 min

The Fokker V.1 was the first cantilever design and came out in December 1916. Testing started in early 1917. The wooden-sheathed wings had two spars and their cantilever design eliminated the need for bracing wires with their associated significant drag. The relatively small lower wings in a sesquiplane configuration had adjustable incidence.

The V.1, whose factory work number was probably 1458, was equipped with a captured 110 hp French Le Rhone rotary engine. Originally the internal factory designation of this prototype followed their 'D' series designations as the D.III, but was later redesignated V.1; the 'V' stood for Verspannunglos or cantilever. Some sources state it was for Versuch, or test.

Instead of normal control surfaces, the V.1 had rotating wingtips instead of ailerons, a rotating vertical tail tip instead of a normal rudder, and fully moving horizontal tail without fixed surfaces. No production aircraft of the time used rotating wingtips and rudder tips. Two machine guns were fitted.

With the V.1, Fokker tried to apply all available aerodynamic knowledge and the V.1 was very advanced for its time. Despite its good performance, the V.1 was not awarded a production contract for reasons that are not documented. Certainly the round fuselage obstructed downward vision.

After flight testing the V.1 was modified; the vertical stabilizer was slightly enlarged and raised and the angle of attack of the lower wing was decreased.

Fokker V.1 Specifications

Engine: 110 hp Le Rhone

Fuel: 75 L fuel & 10 L oil

Wing: Span Upper 8.60 m

Wing area 17.0 m2

General: Length 5.90 m

Height 2.70 m

Empty Weight 442 kg

Loaded Weight 563 kg

Power to Wt. Ratio Empty 4.02 kg/hp

Maximum Speed: 180 km/h

Climb: 1000 m 2.5 min

2000 m 6 min

3000 m 11 min

4000 m 19 min

5000 m 30 min

Fokker V.2

The Fokker V.2 was a more powerful development of the V.1. Powered by the 160 hp Mercedes D.III engine, the larger and more powerful V.2 was built in March 1917, when testing also started.

Originally the V.2 was known by its factory designation of D.IV, (work number 1539), but Fokker later changed its factory designation to V.2 to avoid confusion with the military 'D' designation for fighters.

The wings were structurally similar to those of the V.1 and were somewhat larger. From the start the V.2 had the changes made to the V.1 after its test flights; that is, reduced angle of attack of the lower wing and higher movable rudder with larger fixed surfaces. Again two machine guns were fitted.

As with the V.1, great attention was paid to aerodynamic streamlining. The Mercedes engine and Windhoff radiator were completely covered and a large propeller spinner was fitted.

Despite the additional engine power the anticipated performance improvement did not materialize. Maximum speed increased by 10 km/h but climb rate actually decreased because the V.2 was much heavier than the V.1. Again the prototype was not selected for production.

Fokker V.2 Specifications

Engine: 160 hp Mercedes D.III

Fuel: 85 L fuel &5 L oil

Wing: Span Upper 9.30 m

Wing area 22.0 m2

General: Length 6.60 m

Height 2.94 m

Empty Weight 663 kg

Loaded Weight 921 kg

Power to Wt. Ratio Empty 4.14kg/hp

Maximum Speed: 190 km/h

Climb: 1000 m 3 min

2000 m 9 min

3000 m 16 min

4000 m 29 min

5000 m 47 min

Fokker V.3

The Fokker V.3 (work number 1610) followed the V.2 in May 1917. It was ordered on May 2, 1917 under the factory designation D.VII; that was later changed to V.3 to avoid confusion with the military designation for fighters. Like the V.2 it was powered by a 160 hp Mercedes D.III engine and the two aircraft were nearly identical in size, weight, and performance.

The V.3 had more conventional tail surfaces than the V.2 based on the Albatros D.III to improve flying qualities but retained the rotating wingtips. Two machine guns were designed to be fitted.

The V3 had less streamlined engine and radiator installations than the V.2, likely to improve reliability and maintenance in the field. Nevertheless its performance did not suffer. Like the V.1 and V.2 its round, streamlined fuselage was wide and obstructed the pilots' downward view.

Also like the V.1 and V.2, the V.3 was not given a production order.

Future Fokker prototypes used a thinner, lighter, more advanced cantilever wooden wing design and eliminated the fuselage stringers to simplify construction and improve downward visibility.

Fokker V.3 Specifications

Engine: 160 hp Mercedes D.III

Fuel: 85 L fuel &5 L oil

Wing: Span Upper 9.20 m

Wing area 22.0 m2

General: Length 6.60 m

Height 2.94 m

Empty Weight 680 kg

Loaded Weight 938 kg

Power to Wt. Ratio Empty 4.25 kg/hp

Maximum Speed: 190 km/h

Climb: 1000 m 3.5 min

2000 m 9.5 min

3000 m 17.5 min

4000 m 32 min

5000 m 50 min

Fokker in the Fokker V.1 showing the variable angle of incidence of its lower wing.

The V 1 was a radical cantilever sesquiplane, designed by Reinhold Platz, which began its flight test programme in December 1916.

The V 1 was a radical cantilever sesquiplane, designed by Reinhold Platz, which began its flight test programme in December 1916.

The Fokker V.1 on the Fokker airfield; the Rumpler G.I 15/15, the first Rumpler G.I bomber is in the background.

The Fokker V.1 with engine removed set up for testing a fuel tank in the undercarriage airfoil in 1918.

The Fokker V.1 (without engine) and its airfoil fuel tank alight in the propeller blast of the D.VII without wings.

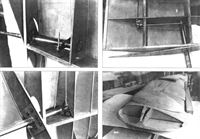

The Fokker V.1 without covering shows its simple structure, including the thick wings. Twin guns are installed.

The Fokker V1 was the first Fokker prototype with a cantilever wing. It had Fokker's welded steel tube fuselage and the first generation thick airfoil cantilever wings covered with plywood. Unusual rotating wingtips were used for roll control; these were replaced by conventional ailerons in subsequent Fokker designs.

The Fokker V1 was the first Fokker prototype with a cantilever wing. It had Fokker's welded steel tube fuselage and the first generation thick airfoil cantilever wings covered with plywood. Unusual rotating wingtips were used for roll control; these were replaced by conventional ailerons in subsequent Fokker designs.

The Fokker V.1. Two LMG.08/15 machine-guns were fitted at this stage, but were later removed.

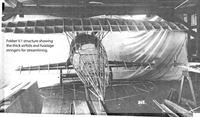

Fokker V.1 structure showing the thick airfoils and fuselage stringers for streamlining.

Fokker V.1 structure showing the thick airfoils and fuselage stringers for streamlining.

Fokker factory photo #900 shows load testing of the Fokker V 1 landing gear. No doubt Fokker was keen to document the strength of his latest design after the failures of the D.I-D.IV quartet. In addition to the usual human load, numerous sandbags come into use as well. As a consequence, the total load of two tons was written onto the chalk board.

The Fokker V.2 was developed from the earlier V.1 but used the more powerful 160 hp Mercedes inline engine. It was larger and heavier than the V.1; despite its greater power the overall performance did not improve.

The Fokker V.2 in its original form, with low-set upper wing and rudder like that of the V.1.

The Fokker V.2 in its original form, with low-set upper wing and rudder like that of the V.1.

The Fokker V.3 was developed from the earlier V.2 and used the same 160 hp Mercedes inline engine. It replaced the unconventional tail surfaces of the V.2 with a conventional tail but retained its rotating wingtips.

The Fokker V.3 was developed from the earlier V.2 and used the same 160 hp Mercedes inline engine. It replaced the unconventional tail surfaces of the V.2 with a conventional tail inspired by contemporary Albatros practice but retained its rotating wingtips. The radiator was offset to the right on the leading edge of the upper wing.

This rearview of the Fokker V.3 shows its rotating wingtips, Albatros-style tail, and bulbous streamlining.

This view of the Fokker V.3 shows it now fitted with two external radiators mounted on the fuselage that significantly reduced its aerodynamic qualities. It still retained its rotating wingtips that were never used on a production Fokker.

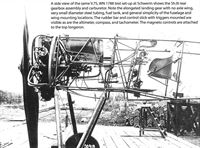

The first Fokker D.VII prototype, V.11, under construction in the foreground. In the background is V.7O with its twin-row Oberursel U.III and deep engine cowling on the floor to the right. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Fokker V.1 with engine removed set up for testing a fuel tank in the undercarriage airfoil in 1918.

July 1918. Hermann Goring, center, with pilots of JG I (Richthofen Circus). Goring became commander of JG I after Reinhard was killed. An ace with 22 victories, Goring later became notorious as Reichsmarschall after Hitler achieved power in Germany. At this period ihe Fokker D VII (seen in background) was entering service in increasing numbers.

Despite not achieving production status, the Fokker V.1, V.2, and V.3 were significant steps. With them Fokker introduced the new, cantilever wooden wing technology and combined the most advanced aeronautical concepts. However, these aircraft more closely resembled armed racing planes than production fighters.

Most significantly, future Fokker designs would use conventional flight controls, a more conventional configuration, and a new, lighter, second-generation wing design.

The original cantilever wooden wing was too thick and too heavy. It was replaced in subsequent designs by a new, second-generation cantilever wooden wing. This more advanced wing had a better airfoil section that was thinner for reduced drag and better flying characteristics. It was also more advanced structurally. Fabric replaced wood in areas that did not need the strength of wood, reducing the weight. The new wing design used a box spar for greater strength with less weight. Verneer covered the leading edge of the wing to maintain the more advanced airfoil section. The new structure was more efficient at the cost of greater complexity.

At this juncture fate, in the form of Idflieg, stepped in. In the spring of 1917 Idflieg was ait the beginning of its Triplane Craze and asked Fokker (and other manufacturers) to build a triplane fighter in the mistaken belief that the triplane configuration offered some unique advantages for a fighter. Just at the point Fokker was on the verge of excellent designs, he responded to Idflieg’s request with the V.4 triplane prototype, that lead to the V.5 and production Dr.I. The Dr.I possessed exceptional climb and maneuverability, qualities not possessed by frontline German fighters at the time.

What the Dr.I did not have was good speed, and that was a result of the extra drag of its triplane configuration and low-powered engine. The later D.VI was essentially a biplane derivative of the Dr.I triplane. Powered by the same 110 hp Oberursel Ur.II rotary as the Dr.I, the lower drag D.VI offered notably better speed and slightly better climb than the Dr.I at the cost of a slight increase in its rolling moment of inertia that caused a small decrease in roll rate. The qualities and appearance of the Dr.I made it famous, while the later, better, and less distinctive D.VI biplane is nearly unknown.

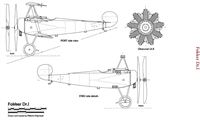

Fokker V.4

Although the V.1, V.2, and V.3 showed admirable turning and handling qualities and benign stall characteristics, overall performance was little better than the Albatros sesquiplane fighters currently equipping the Luftstreitkrafte. The problem was weight to power ratio (W/P), which was too high due to heavy, plywood covered wings and heavy, streamlined fuselages. For the V.1 W/P was 4.02 kg/hp (kilogram per horsepower), for the V.2 it was 4.14 and for the V.3 it was 4.25. Note that each horsepower was carrying more weight as the early V series aircraft evolved. Except for speed, the V.1 actually had superior performance, especially climb, to the later V.2 and V.3. The streamlined fuselages also compromised downward vision on all three types.

Since Fokker had a controlling interest in the Oberursel engine factory, it became obvious any fighter using the 110 hp Oberursel Ur.II copy of the Le Rhone 9J rotary would have to be both small and lightweight, with a weight to power ratio in the 3.0-3.5 kg/hp range. The Oberursel Ur.II was actually a copy of the Le Rhone 9Jb, which with its aluminum pistons, produced 120 hp vs the 110 hp of the steel piston 9J. The Ur.II also had aluminum pistons and British tests of a captured Ur.II showed a maximum horsepower of 127. This was excellent considering the low octane US gasoline being used by the Entente air forces, but was also achieved with good quality castor oil lubricant. The Royal Navy blockade of Germany prevented the Germans from obtaining castor oil relatively early in the war and an inferior substitute lubricant was developed. This T50 substitute lubricant (50% Voltol rapeseed and fish oil and 50% mineral oil) had a very negative effect on German rotary engine operations during the last two years of the war.

Fokker had a contract to provide the Austro-Hungarian Luftfahrtruppe a fighter aircraft through Fokker Magyar Atalanos Gepgyar (MAG) in Matyasfold, Hungary. A triplane fighter was ordered from the Fokker experimental shop on 13 June 1917 with internal designation D.VI, Werknummer 1661, Kommission Nummer 7623. Originally conceived as a biplane, the German triplane craze caused by the success of the Sopwith Triplane, resulted in the design being changed to a triplane.

From the start, Fokker knew he had to keep the design as small and lightweight as possible for use with his Ur.II powerplant. Starting with the fuselage, a short, flat-sided design using very thin steel tubing trussed together with wire at the joints was developed. Thin plywood fillets were sparingly used, as were aluminum cover panels. The flat sides also aided lateral stability compared to the round fuselages of the V.1-V.3 designs and aided downward vision. The Le Rhone 9Jb engine, used until availability of the Ur.II, was covered by a simple aluminum cowl with two ventilation holes designed to force castor or T50 oil fumes out the slot in the bottom of the cowl. This cowl had a full front face, into which the two ventilation holes, propeller shaft hole, and a slot for cylinder rotation and oil vapor exit flow were cut. The Ur.II had passed its tests early in 1917 using castor oil, but modifications for the use of the T50 castor oil substitute meant final approval did not occur until August 1917. This meant most early triplanes were fitted with captured Le Rhone 9Jb engines.

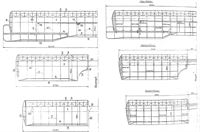

Instead of using plywood covered wings for stiffness like the V.1-V.3, lightweight, fabric-covered wings were developed with a single, very stiff and strong double box spar to maintain the cantilever configuration. This box spar carried through the fuselage for the bottom two wings, which were all in one piece. A thin plywood, almost a veneer, was used on the leading edge of the wings and there was a wire trailing edge. Fabric shrinkage on covering caused the wire to form the familiar scalloped trailing edge. The bottom and middle wings had the same span, while the top wing had a much greater span. Ailerons were only fitted to the top wing, unlike the Sopwith Triplane with its 3 sets of ailerons. For ease of construction, a common rib design and box spar cross section were used for all three wings. The bottom, middle, and center of the top wing had a common chord of 980 mm (millimeters). The wings featured the thick cross section Fokker had come to believe in since his semi-forced partnership with Junkers. Unbalanced ailerons and elevator were matched with a comma shaped rudder with no vertical fin. The only external wires on the aircraft were in an X configuration between the upper wing and fuselage and another X between the landing gear struts. No interplane struts between the wings were used and a small airfoil wing was incorporated around the landing gear axle for extra lift. This actually resulted in some early Idflieg documents referring to Fokker triplanes as vierdeckern (quadraplanes) instead of dreideckern (triplanes).

Construction and testing of the V.4 took place at a very rapid pace, with the V.4 likely flying by 25 June 1917, only 12 days after Fokker ordered the biplane fighter under construction to be completed as a triplane. By 2 July, the English already had an intelligence report that a new triplane fighter was flying. The V4 data table shows the dimensions and other characteristics of the V.4.

From the start, the performance and handling qualities of the V4 were excellent in the hands of an expert pilot. Stall characteristics of the V.4 were relatively benign, like the V.1-V.3. Pitch, roll, and yaw were all relatively unstable, making for a very maneuverable aircraft, with aileron and roll control being one of the primary criticisms of the design. This was likely caused by flexing of the upper wing, due to lack of interplane struts, limiting effectiveness of the ailerons. Top speed was exceptional at 200 km/hr kilometers per hour (124 mph), especially considering the relatively low power of the rotary engine. Climb rate was better than the Albatros V-strutters, but not as good as Fokker had hoped. Werner Voss flew the V.4 and fell in love. The maneuverability of the triplane was phenomenal, with unprecedented rudder authority, and good climb rate. With no dihedral and no vertical fin, the V.4 could happily fly along at ridiculous yaw angles. Flat yaw turns were possible with complete control and the large propeller allowed the triplane to hang on its propeller while pointing the nose in any direction the pilot desired. All of this performance was helped by the much improved weight to power ratio of 3.15 kg/hp, especially when compared to the V.1-V.3, all of which exceeded 4 kg/hp. Details are in the V.4 performance table. Testing was done without the twin machine gun armament, hence the 165 kg payload.

According to Fokker records, Fokker V.4, WN 1661, was painted and shipped to the Ungarische Machinenfabrik, Budapest without an engine or machine guns in August 1917 and received on 3 September 1917 with its cowling missing. It was assigned Austro-Hungarian designation 90.02 and was tested extensively with A-H license built engines. Austro-Hungary received a further triplane for testing, V.7R, WN 1781, at a later date, but decided to go with a version of the simpler V.12/Fokker D.VI biplane fitted with an A-H license built version of the 145 hp, 11 cylinder, Le Rhone rotary.

Fokker V.4 Specifications

Engine: 120 hp Le Rhone 9Jb

Wing: Span Upper 6.21.m

Chord Bottom, Middle, Center top 0.980 m

Wing Area 14.0 m2

General: Length 5.75 m

Height 2.95 m

Empty Weight 346 kg

Loaded Weight 528 kg

Fuel capacity 751

Oil capacity 121

Power to Wt. Ratio Empty 3.15 kg/hp

Maximum Speed: 200 km/h

Climb: 1000m 2.5 min

2000m 5.5 min

3000m 10 min

4000m 17 min

5000m 28 min

Performance with 165 kg load

Fokker V.5 / Idflieg El 101/17

Although V.4, WN 1661, performance and handling characteristics already exceeded that of his Albatros rival's fighters, Fokker could immediately see that changes needed to be made to make aircraft handling more suitable for the average pilot, to increase roll rate, to improve climb rate, and to damp the fluttering of the top wing attached only by the fuselage struts. This would result in a modified design ordered on 5 July 1917, variously identified as a V.4 (Alex Imrie's modified V.4) and V.5 for the same airframe in Fokker sources. The same dichotomy would be found in the two later F.I triplanes, F.I 102/17, WN 1729, and F.I 103/17, WN 1730, also identified as both V.4 and V.5 triplanes, when they were all three V.5 types.

Fokker knew there was a trade-off to be made between climb rate and maximum speed. His observations at the front with Jasta 11 made him think climb rate was more important in summer 1917. This would change in 1918, when maximum speed would become considered most important. Unlike many units, Jagdgeschwader I did not usually fly standing patrols, but used forward airfields to quickly climb after enemy formations were spotted. Warnings came from forward anti-aircraft artillery batteries and other frontline observers, as well as JG I's own observations using binoculars and other optic devices. To increase climb rate Fokker knew the easiest way was to increase wing area and thus decrease wing loading. The spans of the middle and top wings were increased to give an overall wing area of 16 m2 (square meters) compared to the 14 m2 of V.4, WN 1661. This also gave a pleasing symmetry to the wings with their graduated span increase.

To increase roll rate and decrease roll sensitivity, balanced ailerons were fitted with long chord horn balances. To prevent the wing from vibrating and flexing and thus decreasing roll rate, thin wood interplane struts were fitted. The horizontal stabilizer leading edge was less rounded than on V.4, WN 1661, and a balanced elevator with rounded, rectangular horn balances was fitted. This also made the V.5, WN 1697, less sensitive in pitch response and easier to fly.

V.5, WN 1697, was fitted with a Le Rhone 9Jb (120 hp), even though noted in some Fokker sources as an Oberursel Ur.II of 110 hp, others show a 120 hp Le Rhone. The cowling was identical to that on V.4, WN 1661. This design, with a slot in the bottom plate for cylinder rotation, tended to pool castor oil/T50 synthetic substitute oil in the bottom of the cowl and would eventually be changed on the production Dr.I aircraft. Unlike V.4, WN 1661, which was never fitted with machine guns in Germany, V.5, WN 1697, was fitted with two standard, air-cooled, Maxim LMG 08/15 machine guns manufactured by the Spandau Arsenal. Each of these LMG 08/15s carried 500 rounds of ammunition.

Performance of V.5, WN 1697 was spectacular, especially in climb, with climb time to 5000 meters using Fokker figures being nearly halved compared to V.4, WN 1661, 14.5 minutes vs 28. Roll rate increased significantly while being easier to control. Pitch was still very sensitive and the large horn balances on the elevator would be decreased in area on later triplanes. Yaw authority was unchanged, although there would be slight changes to rudder shape as the triplane design progressed, likely more for manufacturing reasons than aerodynamic ones. Fokker still noted a maximum speed of 200 km/ hr (kilometers per hour), although other sources note a decrease to 190 km/hr, to be expected with the increase in weight, payload, and drag from the increased wing span and area. Similarly, other sources noted a 5000 meter climb time of 18 minutes instead of the 14.5 minutes Fokker claimed. This was still a spectacular climb rate for mid-1917.

V.5, WN 1697, was assigned the designation of F.I 101/17 by Idflieg, with the 'F' designation being a new one for the previously non-existent triplane type. This would quickly be changed to 'Dr' for dreidecker. Two further triplane pre-production prototypes, F.I 102/17 and F.I 103/17, for front-line evaluation were ordered on 11 July 1917. These three F.I prototypes were incorporated into an Idflieg order for 20 F.I triplanes from F.I 100/17 through F.I 119/17 made on 14 July 1917. Fokker would eventually figure out how to be paid for F.I 100/17 by assigning the Dr.I 100/17 designator to an experimental triplane built later, V.7O, WN 1830.

In its unpainted, clear-doped linen form and in its later streaked olive and light blue camouflage form, V.5/F.I 101/17 was demonstrated by Fokker and flown by front-line pilots and Idflieg test pilots, including most likely Manfred von Richthofen. Von Richthofen gave a very favorable report on the triplane to his JG I pilots and anxiously awaited its arrival. He had complained about the performance of the Albatros V-strutters equipping JG I that seemed to him little improved over the Albatros D.II of 1916, plus being more fragile.

On 7 August 1917, F.I 101/17, WN 1697, was shipped to Adlershof for testing and its structure was destructively tested, passing with only minor problems. On 11 August 1917, V.5, WN 1697, F.I 101/17, which can be considered the prototype of the Fokker Dr.I series, passed its Bruchprobe (breaking test). V.5/F.I 101/17, WN 1697 details and performance are shown in the accompanying table. This performance would never be matched by a production Fokker Dr.I, especially with the rotary engine problems T50 Voltol induced. The next two V.5/F.I pre-production triplanes, F.I 102/17 and F.I 103/17, though, likely did closely match F.I 101/17's spectacular performance.

Fokker V.5 Specifications

Engine: 120 hp Le Rhone 9Jb

Wing: Span Upper 6.725 m

Wing Area 16.0 m2

General: Length 5.75 m

Height 2.725 m

Empty Weight 375 kg

Loaded Weight 571 kg

Fuel capacity 75 l

Oil capacity 12 l

Maximum Speed: 200 km/h

Climb: 1000m 1.75 min

2000m 3.75 min

3000m 6.5 min

4000m 10 min

5000m 14.5 min

Armament: 2 mgs

V.5 Frontline Prototypes; F.I 102/17 & 103/17

Based on the performance of the V.4, WN 1661 triplane and the praise heaped upon it by frontline pilots, especially Werner Voss, Idflieg ordered a second modified triplane on 5 July 1917. Although this V5, WN 1697 was unlikely to have already flown, Idflieg wanted to get prototypes into the hands of front-line pilots as soon as possible and ordered two more triplanes for operational testing on 11 July 1917. These two triplanes, designated F.I 102/17 (WN 1729) and F.I 103/17 (WN 1730), were destined for Jagdgeschwader I. Pilots would be JG I commander Rittmeister (cavalry captain) Manfred von Richthofen and Jagdstaffel 10 commander Oberleutnant Werner Voss.

Fokker made only minor changes from V.5, WN 1697/F.I 101/17 for these two triplanes. The most obvious were to the horizontal stabilizer and elevator. The large, rectangular horn balances on V5, WN 1697's elevator were reduced in size to match the slightly curved leading edge of the horizontal stabilizer. This slightly curved horizontal stabilizer leading edge was characteristic only of these two prototypes and would be straightened on the production triplanes. The horn balance area decrease alleviated some of the pitch sensitivity noted in the V4 WN 1661, and V5, WN 1697. Both triplanes were fitted with long chord balances on their ailerons that would be shortened on later triplanes. The 980 mm chord on the V.4 and V.5 prototypes' wings would be changed to 1000 mm (1 meter) on the production triplanes.

Since the Oberursel Ur.II was still undergoing qualifications tests with T50 Voltol, both aircraft were fitted with Le Rhone 9Jb engines of 120 hp. F.I 103/17, to be assigned to Oblt Voss, for example, was fitted with an engine, Le Rhone Number 6247, captured from a Nieuport 17 in April 1917. Both engines were fitted with Axial propellers, the one on Voss' triplane having Axial decals covering propeller balance weights, while the one on von Richthofen's triplane had no decals. These decals (or lack of decals) make a handy guide to which F.I is in early photographs. Cowlings identical to that on the V.4, WN 1661 and V5, WN 1697/F.I 101/17 were fitted, with a full front plate with holes and a slot for the cylinders on the bottom. Like Fokker's earlier M series monoplane and biplane fighters, two data plates were riveted to the cowl, one above the other. Production triplanes would only have one data plate.

F.I 102/17 and F.I 103/17 were painted in streaks of olive over clear doped linen on the wing tops, fuselage tops and sides, and horizontal stabilizer tops, with the olive becoming almost solid in the forward part of the fuselage to match the original olive cowls. Cross fields on the upper wing tops and fuselage sides were painted white, as were the rudders. The bottoms of the wings (except for the Eisernkreuz fields, which were left bare clear doped linen), fuselages, and horizontal stabilizers were painted light blue, as were the struts. The wheel covers and top of the landing gear airfoils were also olive, with airfoil bottoms and landing gear struts in light blue. On production triplanes, the light blue paint was returned over the fuselage sides and horizontal stabilizer tops to form a light blue border. This feature was not present on either of the two front line prototype triplanes.

Wingtip skids later fitted to production triplanes were not fitted. Another difference from the production triplanes was that both these F.Is only had the Werk Nummer on the interplane struts without the 'U' for unten (below), 'O' for oben (above), 'L' for links (left), or 'R' for recht (right). As a consequence, Voss' F.I 103/17 eventually had its interplane struts installed with the WN on the struts' insides instead of the correct outsides. Since they were symmetrical, this had no effect on performance or strength.

Both of these F.I triplanes were built by the. Fokker experimental shop with careful attention to materials, construction and workmanship. Neither exhibited any of the poor quality control of wing construction that was to plague early production triplanes. Likely, these two triplanes used some of the scarce remaining castor oil stocks in Germany in August/September 1917, improving reliability of the Le Rhone rotaries.

On 16 August 1917, both F.I triplanes were accepted by ZAK (Zentral-Abnahme-Kommission) at the Fokker factory. On 21 August they were shipped directly from Fokker Schwerin to JG I at Marckebeeke, near Courtrai in Belgium. Arriving with much fanfare at Marckebeeke, both were likely test flown on 28 August 1917, even though the weather was poor. These two triplanes are likely the most photographed aircraft of WWI, with multiple images and extensive movie footage showing Fokker, von Richthofen, Voss, and visiting dignitaries. These visits culminated in the 9 September visit to Jasta 10 by the Austrian Crown Prince with F.I 103/17 displayed in a line-up of shiny new, yellow-nosed Pfalz D.IIIs.

F.I 102/17, WN 1729 Operational History

On 1 September 1917, von Richthofen flew F.I 102/17 operationally for the first time. He approached a 6 Squadron, Royal Flying Corps (RFC) RE8 performing artillery spotting, which apparently misidentified him as a Sopwith Triplane and took no evasive action. Von Richthofen approached within 50 meters and shot the RE8 down using only 20 rounds for his 60th victory.

On 3 September 1917, von Richthofen engaged Lieutenant A. F. Bird of 46 Squadron, RFC in his Sopwith Pup and forced him to land after a fairly long engagement for his 61st victory. Bird later seemed pleased to have survived an engagement with von Richthofen and smiled for photos after his capture. Von Richthofen noted that his triplane was clearly superior to the Pup during the engagement. With a power, speed, maneuverability, firepower, and climb advantage over the 80 hp Pup, this is hardly surprising. After this victory, von Richthofen went on extended leave forced on him by his superiors to recover from his still unhealed 6 July 1917 head wound. He would not score again until 23 November 1917.

F.I 102/17 was turned over to the Jagdstaffel 11 commander, Oberleutnant Kurt Wolff, who had been badly wounded in the hand on 11 July 1917. Wolff returned to flying status on 11 September 1917 and made a visit to the front and Pionierkompanie 89 to familiarize observers on the front with the new triplane aircraft. Several photos were taken of Wolff's visit to Pionierpark Nachtigall.

On 15 September 1917, Wolff was leading Jasta 11's Albatros scouts on a patrol near Moorslede when they encountered a formation of Sopwith Camels. During the subsequent engagement, Sub-Lieutenant N. M. MacGregor of 10 Naval Squadron took a snap shot at F.I 102/17 that unfortunately hit Wolff in the head, instantly killing him. F.I 102/17 dived into the ground very close to where he had visited Pionierkompanie 89, near Klein-Bahnhof Nachtigall (rail substation nightingale). Naval 10's pilots had reported 4 triplanes in the engagement, even though there was only one. MacGregor only claimed an out of control.

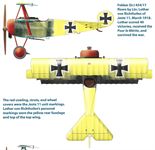

F.I 103/17, WN 1730 Operational History

Werner Voss liked to embellish his aircraft personally and soon decorated his triplane like one of the kites he flew as a child in Krefeld. Jasta 10 was equipped with the brand new Pfalz D.III biplane, which Voss did not like because it was too stable. He was still using an Albatros V-strutter while his pilots flew the new Pfalz aircraft, so he was especially happy to receive F.I 103/17. Voss could do amazing things with an Albatros, and the triplane suited his flying style even better. Voss had already wrung out the V4, WN 1661 triplane, so had a good feel for what his triplane could do. Photographic evidence indicates F.I 103/17 had its cowl and wheel covers painted in what was described by a Jasta 10 pilot as an orangey yellow, sometimes described as mustard colored. To this dark yellow, Voss added the famous eyes, eyebrows and mustache to the cowl in white paint. Later in the war, this dark yellow color became difficult to obtain and Jasta 10 aircraft used a lighter, brighter yellow.

On 3 September 1917, Voss scored his first victory in the triplane over a 45 Squadron, RFC Sopwith Camel. This was Voss' 39th victory and his 2nd over a Camel.

Sometime on the 3rd or 4th of September, Voss' Triplane was hit by machine gun fire that put the famous 9 holes in the rudder and other holes in the right horizontal stabilizer and top wing. This damage was previously thought to have been done on 11 September during an engagement with Sopwith Camels of 45 Squadron. Newly discovered photos from 5 September 1917 at 1600 hours with Fokker and Voss together with F.I 103/17 already show the repaired bullet holes in the rudder. In addition to the photos of Voss and Fokker with the Triplane, a series of 3 photos, front, side, and rear, were likely taken on 5 September that highlight the damage to F.I 103/17. Clearly visible in the rear photo are the 9 repaired bullet holes in the rudder later noted by Lieutenant Rhys Davids, who received F.I 103/17's white rudder as a souvenir. Also visible in the photos are holes in the top wing and horizontal stabilizer. Voss was lucky he was not hit. No details of how the damage was done in early September have been discovered.

On 5 September a Sopwith Pup of 46 Squadron, RFC became Voss' 40th credited victory, although 2nd Lt C.W. Odell managed a forced landing just inside English lines. This Pup was eventually recovered and repaired. Odell survived the war with 7 victories. Voss' second victory of the day was credited as his 41st over a French Caudron, although no matching French loss can be found. The Caudron may have made a forced landing inside French lines and was not counted as a loss by the French.

On 6 September, an F.E.2d of 20 Squadron RFC fell in flames to Voss above Boesdinghe. This was number 42 for Voss.

On 10 September Voss scored a triple. In the same engagement, he shot down two Sopwith Camels of 70 Squadron, RFC, killing both pilots. 25 minutes later, Voss then shot down a French SPAD 7 from Escadrille Spa 7. These were his 43rd, 44th, and 45th victories. On 11 September Voss scored another double, first likely forcing down a Bristol F.2B from 22 Squadron, RFC (also reported as a Sopwith Camel of 45 Squadron) in the morning for number 46. On a later sortie in the afternoon, Voss downed a Sopwith Camel of 45 Squadron, RFC for number 47. While shooting down Lieutenant O. L. McMaking, an ace with 6 victories, Captain Norman MacMillan tried to save McMaking and fired at F.I 103/17. In his book Into the Blue, MacMillan noted Voss looked over his shoulder at him, dismissed the threat, and then continued to shoot down McMaking in flames. Voss was getting increasingly confident as time went on, almost as if he and the Triplane were invulnerable. In this case, Voss was correct, as MacMillan scored no hits on F.I 103/17.

Voss had scored nine victories in only 8 days and was rapidly closing in on von Richthofen's 61 victories. This was especially true since von Richthofen was on extended leave and not expected back until November. After this engagement, Voss went on what was probably a much needed leave. He visited the Fokker factory during this time and a photo exists of him sitting in an early production Triplane with a makeshift headrest never used on production Triplanes.

On 23 September 1917, Voss was back from leave and flying F.I 103/17 again. That morning Voss engaged and quickly shot down a D.H.4 of 57 Squadron, RFC that had been engaged in a bombing mission against Hooglede. A photo was taken of the Voss brothers Werner, Otto, and Max, likely taken after lunch and before his late afternoon sortie.

In the late afternoon of 23 September, Voss and F.I 103/17 were involved in what must be considered one of the greatest aerial engagements and fight against odds in aviation history. Voss engaged S.E.5a aircraft of 60 Squadron and 56 Squadron, RFC, forcing four S.E.5a aircraft out of the fight with serious damage, and putting bullet holes through all 11 aircraft he engaged. As some context, contrasting the performances of the S.E.5a and F.I triplane may help understand the bravery of Voss during this engagement. The S.E.5a top speed at sea level was approximately 135 mph (217 kph), at least 10 mph (16 kph) faster (and probably more) than the triplane's 124 mph (200 kph). At low altitude in climb, though, the F.I had a clear advantage, taking only 6.6 minutes to reach 10,000' (3048 m), while the S.E.5a required 11 minutes to reach the same altitude. This matches with 56 Squadron pilot after action reports and later comments that Voss had a much better climb, was often the highest aircraft in the engagement, and could have climbed east out of danger at any time. This altitude advantage could also be used by Voss to dive and gain airspeed. The triplane also offered a clear advantage in maneuverability over the S.E.5a, which was a fast, tough, and stable gun platform but not particularly maneuverable by rotary engine fighter standards and with a tendency to lose altitude in turns. The F.I triplane's lack of dihedral and thick airfoil section allowed quick, flat rudder turns, which the high dihedral S.E.5a could not match. Several pilots mention Voss making flat rudder turns and throwing the tail behind him without affecting controllability at all. Lastly, the triplane enjoyed firepower superiority to the S.E.5a with its two LMG 8/15 machine guns with 500 rounds each compared to the S.E.5a and its single Vickers with 400 rounds and over the wing Lewis with four 97 round removable drums. Several of the S.E.5a pilots mention departing the fight to change out their Lewis drums, and this cut down on their engagement time.

The outcome of this engagement is well known and extensively documented, with Lieutenant Rhys Davids eventually killing Voss after a nearly 10 minute engagement. F.I 103/17 crashed on the English side of the lines near Plum Farm. This ended the operational history of the two F.I frontline prototypes. Several pieces of F.I 103/17 were recovered, including the rudder mentioned previously, and all eventually ended up at the Imperial War Museum, where they have been lost to history except for photographs.

The first production Fokker Dr.I triplanes, little changed from F.I 102/17 and F.I 103/17, were accepted by ZAK on 9 September and six had been accepted before Voss' final flight on 23 September. The first production triplane, Dr.I 115/17, WN 1783, to reach the front was shipped from Fokker Schwerin on 4 October 1917 for the ill-fated Leutnant Heinrich Gontermann, commander of Jasta 15.

Fokker V.7 & Experimental Dr.I Triplanes

Anthony Fokker's prototype shop built four documented V.7 (Versuchs for experimental) aircraft based on his Fokker Dr.I Triplane. Factory documents show all four V.7 Triplanes having 160 h.p. engines installed, each from a different manufacturer. These four aircraft were easily identified as different from a standard Dr.I by their lengthened fuselages and modified cowlings. The stretched fuselages balanced the extra weight of the heavier, higher horsepower engines fitted to boost performance. The modified cowlings were needed to fit what were considerably larger engines than the Dr.I's standard and interchangeable Oberursel Ur.II and Le Rhone 9J engines.

The V.7 Triplanes were initially built with the intention of gaining more orders for an improved performance Dr.I. Start dates on building the V.7 aircraft fit into the relatively short time period of 13 August - 24 October 1917. Since the V.11 prototype for the eventual Fokker D.VII was started on 20 September 1917, the V.7 Triplanes were most likely not Fokker's highest priority. He was in the process of building numerous new designs for the Adlershof fighter competition scheduled for January 1918.

This lack of priority could also have been exacerbated by the problems rotary engines were having with rotary engine lubricating oil because the English naval blockade had cut off all supplies of castor oil. This did not stop Fokker, however, from producing new rotary engine designs that ultimately became the Fokker D.VI and E.V/D.VIII. With the help of factory documents and photos from the Fokker Heritage Trust, a fairly complete description of these experimental triplanes can be made.

Fokker V.7S WN 1788

The first V.7 was Werknummer (WN) 1788, which was identified by the factory as the V.7S for its 160 h.p. Siemens-Halske III eleven-cylinder rotary engine. V.7S was ordered on 13 August 1917, well before the two prototype Fokker F.I Triplanes were sent to Jagdgeschwader I for operational evaluation. The Sh.III high compression engine was to have severe teething troubles until fully developed. The Sh.III ultimately provided phenomenal performance, especially in climb and at high altitude, in the later Pfalz D.VIII and Siemens-Schuckert SSW D.III and D.IV fighters. In the Sh.III engine, the cylinders rotated in one direction and the crankshaft rotated in the opposite direction. This cleverly overcame the normal rotary engine speed limitation of approximately 1500 revolutions per minute (rpm), above which rotation speed the cylinders tended to come off. By using the counter-rotating design, the cylinders and propeller could rotate at 1800 rpm and the crankshaft in the opposite direction at 900 rpm for an actual rotation speed of propeller and cylinders of 900 rpm. In general, the higher the rpm, the higher the horsepower an internal combustion engine can develop, so the Sh.III had an advantage over typical rotary engines with limited rotation speed.

The only drawback was that the cooling provided by the spinning cylinders was also decreased by the lower rotation speed. The Sh.III's low cylinder rotation speed and high compression, combined with lubricant problems, caused initial overheating, cylinder bluing, piston failure and other heat related issues until Sh.III development matured. Surprisingly, the license built Sh.III (Rh) built by the Rhemag-Rhenania Motorenfabrik in Mannheim did not seem to have as many problems. These cooling problems were not actually solved until summer 1918 when the Sh.IIIa became available from Siemens and Rhemag.

The V.7S, WN 1788 is probably the most familiar of the V.7 Triplanes to WWI aviation enthusiasts. Relatively well documented in photographs while under construction and test at the Fokker factory in Schwerin and while at Adlershof, V.7S was also the most heavily modified of the V.7 aircraft. In addition to the longer fuselage and large, distinctive cowl, made even larger by the Sh.III requirement to provide structure to carry front and rear motor mount bearings and a rear gearbox assembly, the landing gear was also lengthened. This lengthening of the landing gear was necessary to clear the large propeller necessary for the Sh.III to provide maximum performance at low propeller rpm, especially with the initial two bladed propeller.

These extensive modifications made the V.7S the heaviest of all rotary-powered Triplanes, and V.7S was a full 115 kilograms heavier than a standard Dr.I. Photographs of V.7S show it fitted with both two- and four-bladed propellers. Like the Pfalz D.VIII and the SSW D.III/D.IV, the ultimate choice was the four-bladed propeller, which could absorb all the Sh.III's power while turning relatively slowly.

V.7S was initially fitted with a huge axle wing, nearly the size of one lower wing, but this caused the aircraft to float on landing and the axle wing was eliminated, as shown on most V.7S photographs.

V.7S was at Adlershof, but did not compete in the first fighter competition held there. It is known that two modified Dr.I aircraft did participate at Adlershof, and these Dr.I Triplanes will be discussed later. V.7S is one of two V.7 Triplanes Fokker may not ultimately have claimed to convert to a Dr.I, the other being WN 1981, which was sold to the Austro-Hungarian government. Fokker converted (on paper at least) V.7 aircraft back to the Dr.I standard so he could be paid for them as part of the 320 or so Dr.I Triplanes Idflieg ordered. At least one source, however, states V.7S, WN 1788 was refitted as Dr.I 120/17 after having a standard Ur.II installed. There is no record of Dr.I 120/17 ever being accepted, so the conversion is questionable. V.7S could also have been originally ordered as an experimental aircraft by Idflieg. Rumors of Fokker resisting fitting the Sh.III to the Dr.I have been published in the past, but are most likely just that, rumors, his ownership of Oberursel notwithstanding.

Fokker V.7S with Axle Wing

Shown on a photo of V.7S taken at Fokker Schwerin on 29 December 1917 with a very large axle wing. Because of the lengthened landing gear struts, needed to provide clearance for the two-blade and eventual four-blade Axial propellers, the axle wing appears to be nearly twice the size of a standard Dr.I axle wing. It is little wonder it caused the aircraft to float, it is nearly a bottom wing half in size.

Looking at the photo closely, the elevator has been removed. The markings on the top wing show the "DRI XXXX FL N XX" are not centered around the middle rib as on later Dr.I aircraft, but offset to port. Whether this was true of some or all early Dr.I wings is not known because most photos of pre-grounding aircraft are not high enough resolution to see this level of detail. The wings still retain the Fokker F.I style ailerons with the long chord balance horns and two aileron rib taper to merge with the rear of the wing.

The wing rib tapes are very unusual for a Triplane since they appear to have been applied after the wings were painted. On later Dr.I aircraft, it is nearly impossible to see the wing rib tapes except in a very high resolution photograph because they were painted the same colors as the wings. Here they are very visible. Since V.7S was fitted with a set of wings identical to the early Dr.I, the wings would have had to be modified to meet the Idflieg directive on Fokker Dr.I wings. Based on this photo, it now appears Fokker repaired the original early Triplane wings and even reused the same fabric after the repairs. This is the most logical explanation for the light colored rib tapes over the painted fabric.

The cowling is unpainted in this early photograph, but would be painted olive before shipping to Adlershof. The wheels are clear doped over what appears to be very light, bleached linen, and they would also be painted before shipping. The Fokker Dr.I aircraft in the background also have unpainted cowls most likely painted before delivery. The massive Siemens-Halske Sh.III engine is clearly visible. Although its compression ratio was only 5.0-5.1:1, the Sh.III was considered a Hohenmotor or high altitude engine and uberkompromierte or overcompressed.

Fokker V.7O WN 1830

V.7O, WN 1830, was named by the factory for its Gnome-based, twin-row, fourteen-cylinder, 160 h.p Oberursel U.III rotary engine. One other factory document shows it as the V.7m for Gnome. Oberursel engine designations were U.0 - U.III (skipping, apparently, U.II) for Gnome-based engines and Ur.II - Ur.III for Le Rhone based engines. Idflieg and factory documents used Gnome and the Oberursel U-series engines' names interchangeably as they did for the Le Rhone and Oberursel Ur series engines. As an example, an original Dr.I propeller inspected by Fred Murrin was stamped with engine type Le Rhone, not Oberursel.

The U.III, a license-built version of the Gnome double-lambda engine, was essentially two Oberursel U.0, seven-cylinder, 80 h.p. engines mounted on a common crankshaft. The U.III, like the Sh.III, required both front and rear bearings to support the engine. Most rotary engines required only a rear bearing. The front and rear bearing configuration necessitated fitting a large diameter, lengthy cowl to cover the engine and support structure. The Oberursel U.III is the same engine fitted to the thin-winged M-series Fokker E.IV Eindecker and Fokker D.III biplane.

Large and heavy, the U.III provided small performance improvements in the E.IV over the Fokker E.III fitted with the Gnome Delta based, 100 h.p. Oberursel U.I, and only small improvements in the Fokker D.III over the Fokker D.II also fitted with the U.I. Since the U.III used the same early Gnome automatic intake valves as the U.0 and U.I, the U.III also suffered from the same lack of reliability, but with more chances for failure. The U.III did provide a slight increase in top speed and more weight-carrying capability, and the E.IV and D.III could thus carry twin gun armament. Climb, however, was only marginally improved and maneuverability suffered compared to the E.IV's and D.III's lighter engine predecessors. Why Fokker elected to try what was essentially a dead-end engine in a Triplane is unknown, but his ownership of the Oberursel factory undoubtedly had an influence.

Fokker V.7O WN 1830, which was begun on 23 August 1917, is very poorly documented by photographs. The only known photo is Fokker factory photograph #1055 of the Fokker V.11 under construction. In the background of this photo can be seen, head-on, the uncovered fuselage of V.7O with a twin-row Oberursel U.III and sheet metal support structure fitted. Even though published sources on this Triplane have speculated on what engine it carried, careful study of the photograph shows the twin row configuration of the U.III engine. The landing gear appears to be standard Dr.I. On the factory floor next to V.7O can be seen a massive cowl which undoubtedly went with the airframe. As would be expected, V.7O must not have impressed with its performance and was converted to a standard Dr.I. Assigned serial number 100/17 (sometimes seen as 100/18), Dr.I 100/17, WN 1830 was accepted on 26 April 1918. Idflieg's initial order for 20 F.I Triplanes included 100/17 through 119/17, and Fokker made sure he was paid for every one of them.

Fokker V.7G WN 1919

V.7G, WN 1919 was one of several Triplanes fitted with the nine-cylinder, 160-200 h.p. Goebel Goe.Ill rotary engine. The Goe.III's conventional, large diameter (1140 mm vs 960 mm for a Ur.II), single-row, rear-bearing-only layout made it relatively easy to adapt to the Dr.I airframe. The Goe.III weighed 183 kg vs. the approximate 148 kg of the Ur.II or Le Rhone 9J, so it did not have a large impact on aircraft center of gravity.

According to Fokker factory documents, an uberkompromierte (over-compressed or high compression) 160-175 h.p. version of the Goe.III was fitted to V.7G. An NACA (National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, which was the 1915-1958 NASA predecessor) report on Goebel engines published in March 1921, stated that the Goe.II and Goe.III used a single pushrod-actuated exhaust valve and an automatic inlet valve, much like the 100 h.p. Gnome Delta-based Oberursel U.I engine fitted to the Fokker E.III. The automatic intake valves on the early Gnomes and derivative Oberursel U-series engines were a maintenance nightmare and caused no end of in-flight and ground aborts when the intake valves stuck open. The main difference between the Goebel engine and the early Greek letter Gnome engines is that the Goe.III connecting rods provided positive closing of the intake valves.

Only 229 Goe.IIIs were produced during the war and none were used as the production engine in a series-produced aircraft. It is interesting to note Idflieg's original order for the Fokker E.V specified the 160 h.p. Goe.III or the 145 h.p., eleven-cylinder, Oberursel Ur.III. Neither the Ur.III nor the Goe. Ill engine could be produced in sufficient quantity for production use, however, and the original order E.V monoplanes were fitted with 110 h.p. Oberursel Ur.IIs.

V.7G WN 1919 was an especially mysterious V.7 for which no known photographs existed until recently. Peter Grosz' files had a profile drawing of the aircraft from the Baubeschreibung fur D.R. Flugzeuge Fok Dr.I Blatt 2 (Construction Specification for Triplane Aircraft Fokker Dr.I Sheet/Page 2) and the note that it was powered by a 170 h.p. Goe.III.

Fokker began building V.7G on 12 October 1917. Intermediate in weight between a standard Dr.I and the extensively modified V.7S, the high compression engine gave excellent climb performance, especially at altitudes above 4000 meters. This Triplane had standard Dr.I landing gear, the V.7 lengthened fuselage and a bulged cowling to fit over the large diameter engine.

Factory photo #1674 was taken at the Fokker factory in Schwerin and most likely shortly postwar. Sitting in the background of this factory floor shot, with numerous Fokker E.Vs/D.VIIIs and D.VIIs in the foreground, was a V.7 fuselage which could only be V.7G. The fuselage in the photograph perfectly matched Peter Grosz' profile drawing from the Baubeschreibung. Painted with streaked camouflage and the latest Balkenkreuz markings, V.7G must have been updated several times during its life. Fokker records indicate V.7G, WN 1919 was converted to a standard Dr.I, serial number 599/17, the last Dr.I in serial order. This obviously never happened, although a new DR.I fuselage could have been matched with V.7G's standard Triplane wings as DR.I 599/17 WN 1919.

Fokker V.7R WN 1981

V.7R, WN 1981 was named for its Austrian-built, Steyr Le Rhone, 150 h.p. rotary engine. The Steyr Le Rhone was an eleven-cylinder, large-diameter, single-row rotary engine supported by a rear bearing only. The Steyr Le Rhone was virtually a direct copy of its French Le Rhone counterpart and displayed no Oberursel characteristics. This engine is described in various sources as having 145 h.p., 150 h.p., and 160 h.p. ratings, even for the same installation, but there was only one engine type.

The Steyr Le Rhone was very similar to the 145 h.p. Oberursel Ur.III, but was much more successful and actually went into series production. The engine ran well using the castor oil replacement, T50 synthetic lubricant, though shortages of even the synthetic castor oil plagued Austro-Hungarian operations until the end of the war. Production Fokker aircraft were shipped from Schwerin to the Austro-Hungarians with no guns, engines or propellers. These indigenous components were then fitted by Fokker MAG (Magyar Atalanos Gepgyar) in Matyasfold, Hungary.

To give some idea of the high regard in which the Germans held the Steyr Le Rhone, efforts were underway when the war ended to do an exchange for this outstanding rotary engine with the very successful 185 h.p. BMW IIIa inline six. Fokker V.7R, WN 1981 and a sister ship, the Fokker D.VI prototype, V.12, WN 1980, were sent to MAG on 3 January 1918 and may or may not have already had the Austro-Hungarian components fitted as the first prototypes for a possible production buy. In any event, it was the V.12-based Fokker D.VI which was eventually chosen for purchase by the Austro-Hungarian government over the Dr.I-based V.7. Cost may also have been a factor in this decision since factory invoices show that the V.7R, WN 1981 cost DM 26,000 vs. DM 23,500 for both the engineless production Fokker D.VI and for later purchases of engineless Fokker D.VIIs.

A relative bounty of photographs documents V.7R, WN 1981. Begun on 24 October 1917, V.7R had the V.7 lengthened fuselage, standard Dr.I landing gear and a bulged cowl with three additional cooling holes above the normal pair of Dr.I cooling holes. In one photo of V.7R, "DRI 1981" can be seen on the bottom leading edge of the top wing. Given the serial number 90.03 more or less unofficially, V.7R eventually had "M.A.G. BUDAPEST?" painted on its side, the "?" referring to the fact the 90.03 serial number had not yet been allocated officially.

This Triplane took part in the July 1918 Austro-Hungarian equivalent of the Adlershof fighter competitions, which were held at Aspern. Following the Fighter Evaluation competition, V.7R was badly damaged in a crash landing while being flown by MAG factory test pilot Feldwebel Josef Nemeth. During a test flight, the rudder cable broke and the resultant crash landing severely damaged the Triplane. By this time, Fokker was using double rudder cables in Germany to prevent such mishaps. Clearly visible in post-crash photos, the landing gear was destroyed, the starboard side wings and both ailerons were heavily damaged, the horizontal stabilizer and elevator and rudder were nearly destroyed, and the front of the fuselage and cowl were crushed. In all probability, V.7R, WN 1981 was written off after this accident, especially since the decision had already been made to go with the Steyr Le Rhone powered Fokker V.12/D.VI biplane instead.

Fokker V.7 Myths Disproved

It begins to appear that there were several myths about the V.7 Triplanes which have been perpetrated over the years. The first of these myths is that the 145 h.p. Oberursel Ur.III engine was fitted to a V.7. We now know an Oberursel Ur.III was fitted to a relatively standard Dr.I, but never to a V.7. The second myth is that a V.7 was fitted with a captured nine-cylinder, 160 h.p. Gnome 9N monosoupape which normally powered the Nieuport N.28.

This latter myth came about because of confusion in factory documents about a V.7 being fitted with a 160 h.p. Gnome. The engine fitted to V.7m/V.7O was, of course, the license-built Gnome fourteen-cylinder, twin-row rotary, the Oberursel U.III. The Americans did not begin flying the Nieuport 28 until the spring of 1918, by which time the D.VII was Fokker's future, not the Triplane. There is no evidence of an operational Dr.I ever flying with a captured 160 h.p. Gnome 9N either.

The third myth is that the Fokker V.7S, WN 1788 with the Sh.III engine, competed at the first Fighter Competition in January 1918. Written sources now show that two relatively standard Dr.I Triplanes fitted with Oberursel Ur.III and Goebel Goe.III engines flew during the competition, but not as formal competitors. Adlershof was the German WWI equivalent of Edwards AFB today, with many experimental aircraft and production aircraft flying. Just because V.7S spent most of its life at Adlershof does not mean it participated in the competition. Highlighting the V.7S and other Triplanes at Adlershof would have distracted from production orders Fokker hoped to obtain for the eventual Fokker D.VI and D.VII.

Other Experimental Dr.I-based Triplanes

Some sources have stated that as many as 30 Dr.I Triplanes were fitted with Goebel Goe.III engines and delivered for Jasta service. In actual fact, there is no photographic record of any Goe.III-engined Dr.I ever having been delivered for combat use. Only V.7G, WN 1919, and a handful of experimental Dr.I Triplanes were fitted with the Goe.III, and there is virtually no photographic record of the Dr.I fitted with the Goe.III. One confusion factor was the fact that several late production Dr.I Triplanes were delivered with the seven-cylinder, 100 h.p. Goe.II for use at the Jastaschulen, and these Goe.IIs may have been confused with Goe.IIIs. An example of this is Dr.I 416/17, WN 2000, which was stated in some sources as having a lengthened fuselage and Goe.III engine. In fact, there is a widely published photograph, taken at a Jastaschule, of the quite standard, unarmed Dr.I with a seven-cylinder Goe.II and a plainly visible "DRI 2000" stencil on the bottom of the top wing.

The first Dr.I to be fitted with the Goe.III was Dr.I 108/17, which went to Adlershof for evaluation. Converted back to Le Rhone/Ur.II power, Dr.I 108/17, WN 1776, was accepted by Idflieg as a standard Triplane on 12 December 1917. The results of this evaluation were apparently good enough to encourage Fokker to install a Goe.III on Dr.I 200/17, WN 1918, which flew during the January 1918 Adlershof Fighter Competition. This was reported by the factory as a 200 h.p. Goe.III.

The next Triplane in sequence, Dr.I 201/17, WN 1920, was reported to have a 178 h.p. Goe.III and to have been delivered on 13 November 1917. The difference in horsepower ratings between Dr.I 200/17 and 201/17 may have been due to the different power levels the engine developed at different altitudes and may also have been due to experimentation with different compression ratio pistons. If the pistons gave a high enough compression ratio, the engine was called uberkomprimiert. Engines which were uberkompromiert normally could not use full throttle at sea level without risking pre-ignition detonation damage. These engines actually produced more power at altitude where full throttle could be used. The most well-known example is the BMW IIIa inline six, which developed 185 h.p. at sea level, but 260 h.p. at altitude.

It is doubtful 201/17 was still fitted with a Goe.Ill when delivered, and in fact Dr.I 201/17, WN 1920, went to Adlershof on 13 November as the first aircraft fitted with the new, improved wings. It most likely had a Ur.II when shipped. Such an unusual configuration as a Goe.III fitted Dr.I would undoubtedly have generated photographic evidence at the front and Triplanes thus equipped would have gravitated towards one of the top aces. No photographs of 108/17, 200/17, or 201/17, and their Goe.III installations have surfaced. It is interesting to note that three Triplanes in WN sequence received Goebel engines, WNs 1918 (Dr.I 200/17), 1919 (V.7G), and 1920 (Dr.I 201/17).

Hauptman Adolf von Tutschek's Dr.I 404/17, WN 1988, is also mentioned in some sources as being fitted with a Goe.III. All photographs of this machine in Jasta 12 service, however, show an engine that looks exactly like a standard Le Rhone 9J installation. Further research by Peter Grosz, however, discovered that Dr.I 404/17 had actually been fitted with a Ur.II (Rh), serial number 82. Ur.II (Rh) engines are indistinguishable visually in photos from Le Rhone 9J or Jb engines, unlike Ur.IIs with their separate front propeller shaft cover. There was initially confusion over the low serial numbers of the Ur.II (Rh) engines that resulted in postulation they were Goe.III engines.

One modified Dr.I for which photographic evidence exists is Dr.I 469/17, WN 2095, which was fitted with the 145 h.p., eleven-cylinder, Oberursel Ur.III. This aircraft was a more or less standard Dr.I with a bulged cowling to accommodate the large-diameter Ur.III. Some confusion also existed in the past that Dr.I 469/17 was a V.7, but photographic evidence proved otherwise This Triplane flew in the January 1918 Fighter Competition, but not as a formal competitor. Fokker performed a valuable service by painting "Fok DRI 469" in large letters and numbers on this Triplane's wheels.

A later photo of this same Triplane clearly shows the Ur.III installation and that the aircraft by then had no wing tip skids fitted. This photograph was mistakenly identified as F.1101/17, WN 1697, based on its lack of wing tip skids, unpainted aluminum cowl, and clear-doped linen wheel covers. Closer examination of the photo, however, shows the last version Dr.I ailerons, a larger cowl of different shape without the F.I engine slot, a straight leading edge on the horizontal stabilizer, stacking pads which were never fitted to the F.I, too many exposed cylinders, and a standard Dr.I rudder.

Two photographs taken at Adlershof, one of which is shown, are of a Dr.I with an extended cowl much like V.7O, WN 1830. This Dr.I was powered by a Siemens developed Schwade supercharged rotary. Originally thought to be a Ur.II, then an Sh.I, neither matched the layout of the rotary in the photos. Best guess is a captured 80 hp Le Rhone 9C, an Oberursel version of which is not documented. Fitted to an Sh.I in a Nieuport inspired SSW D.I, the supercharger halved climb times to 5000 meters.

Summary

Experimental versions of the Fokker Dr.I, including the V.7 Triplanes, were fitted with a variety of engines to try and improve performance.

The Sopwith Camel, an aircraft with similar performance, was upgraded during its service life with improved performance 140 hp Clergets, the 150 hp BR-1, and the 160 h.p. Gnome 9N to keep it up to date, even though some Camel units soldiered on until the end of the war with 120 h.p. Le Rhone engines.

In the Fokker Dr.I Triplane's case, though, the original order was for a few hundred, not several thousand, aircraft. Despite the phenomenal climb performance of the up-engined V.7s and Dr.Is, line pilots wanted speed more than climb or maneuverability. A triplane's extra drag ensured it would never be as fast as an equivalent biplane or monoplane. By the time the Fokker Dr.I Triplane's grounding was lifted and aircraft were flowing again to a select few units in the winter of 1917/18, Fokker had better designs, both on the drawing board and flying, from which to choose. The miserable service record of aircraft fitted with rotary engines running the synthetic T50 oil was probably also a factor in the lack of interest in an up-engined Triplane.

V.7 and Other Modified Fokker Dr.I Triplanes

Type WN SN Engine Comments Disposition

V.7S 1788 N/A * 11 Cylinder, F&R Bearing Siemens-Halske Sh.III Tested at Adlershof Unknown? 120/1’7 ?

V.7O 1830 N/A * 14 Cylinder, F&.R Bearing, Twin Row Oberursel U.III Little Known of

Test History Delivered as Dr.I 100/17

V.7G 1919 N/A *9 Cylinder, Rear Bearing Goebel Goe.III Markings Latest Balkenkreuz Schwerin 1918/1919

V.7R 1981 N/A * 11 Cylinder, Rear Bearing Steyr Le Rhone Extensively Tested in A-H Heavily Crashed

Dr.I 1776 108/17 160 h.p. Goebel Goe.III Tested at Adlershof Unknown

Dr.I 1918 200/17 200 h.p. Goebel Goe.III Flew Jan 1918

Adlershof Unknown

Dr.I 1920 201/17 178 h.p. Goebel Goe.III Tested Adlershof Unknown

Dr.I 1988 404/17 110 h.p. Ur.II (Rh) Serial

Number 82 Von Tutschek Jasta

12 Destroyed in Combat

Dr.I 2000 416/17 7 Cylinder, 100 h.p. Goebel Goe.II No V.7

Characteristics Delivered Jastaschule

Dr.I 2095 469/17 11 Cylinder, Rear Bearing

145 h.p. Oberursel Ur.III Flew Jan 1918

Adlershof Unknown

Dr.I Unk Unk 9 Cylinder, Schwade Supercharged Rotary Tested at Adlershof Unknown

* All V.7s reported by factory as having 160 h.p. engines.

Time to Climb Performance from the Dr.I Baubeschreibung and A-H Documents

Time to Climb (Mins) Dr.I 141/17

WN 1853 V.7G WN 1919 V.7R

WN 1981* V.7R WN 1981** Dr.I 469/17

WN 2095

0-1000 m 2.9 2.0 1.5 1.9 2.0

0-2000 m 5.5 4.0 4.0 4.3 4.3

0-3000 m 9.3 7.0 7.3 7.9 7.1

0-4000 m 13.9 10.0 11.5 12.5 10.8

0-5000 m 21.9 14.0 N/A N/A 15.5

0-6000 m N/A 20.0 N/A N/A 23.5

* Fokker figures

*‘Official A-H K.u.K. figures from 12 March 1918 test

Weights from the Dr.I Baubeschreibung

Weights Dr.I 141/17 WN 1853 V.7S WN 1788 V.7G WN 1919 Dr.I 469/17

WN 2095

Empty 376 Kg* 491 Kg 440 Kg 430 Kg

Payload 195 Kg 195 Kg 195 Kg 195 Kg

Gross 571 Kg 686 Kg 635 Kg 625 Kg

* Seen as 391 Kg, 195 Kg, and 586 Kg in some sources

Fokker Triplane Serial Numbers & Work Numbers

Type Military Serial Number Fokker Works

Number

See note 100/17 1830

V.5 / F.I 101/17 1697

F.I 102/17-103/17 1729-1730

Dr.I 104/17-119/17 1772-1787

V.7S 1788

V.7O 1830

Dr.I 121/17-140/17 1832-1851

141/17-170/17 1853-1882

171/17-200/17 1889-1918

V.7G 1919

Dr.I 201/17-220/17 1920-1939

V.7R 1981

Dr.I 400/17-429/17 1984-2013

430/17-459/17 2055-2084

460/17-489/17 2086-2115

490/17-519/17 2117-2146

520/17-549/17 2188-2217

550/17-597/17 2220-2267

598/17 2269 (?)

599/17 1919

Fokker Dr.I Production Fighters

The operational debut of the Fokker Triplane had been brief and spectacular. RFC pilots reported there were many more at the front than just the two F.I triplanes. Von Richthofen was notified while on leave that his two good friends, Wolff and Voss, had been killed in combat flying the two prototype Triplanes. One was killed by a more or less lucky shot on 15 September 1917 and the other by a concentrated effort of the aces of 56 Squadron, RFC, and their S.E.5a aircraft on 23 September 1917.

As mentioned earlier, six production Fokker Dr.Is had been accepted by ZAK before 23 September 1917, when Voss was killed. These Triplanes differed only slightly from the two F.I Triplanes flown by Wolff and Voss. For simplicity, the basic wing chord was changed from 980 mm to 1000 mm. The leading edge of the horizontal stabilizer was straightened to simplify production. The early V.4/V.5 cowl shape was changed by eliminating the lower section of the front plate that had been slotted for engine cylinder rotation. This left the lower part of the cowl open so castor/T50 oil was no longer trapped and made the cowl easier to remove. The large central opening for the prop boss was changed to a smaller opening to make it easier to remove. Flight tests of the V.4 and V.5 had shown a tendency to drag a wing tip on rough surfaces, sometimes resulting in a ground loop but always in wing tip damage. So wooden skids were fitted on the bottom of the wings to alleviate this problem. Factory markings were added to identify most assemblies, and the interplane struts were marked with upper and lower, right and left markings in addition to the WN. Instead of being built at the Fokker factory, the wings were now built at Fokker's Perzina Werk piano factory. This latter fact would have grave consequences for early Dr.I Triplanes.

The first production Fokker Triplane to be sent to the front was Dr.I 115/17 on 4 October 1917, fitted with a Le Rhone 9Jb, as were most early Dr.I aircraft. This aircraft was sent to Ltn. Heinrich Gontermann, Staffelfuhrer of Jasta 15 and noted balloon buster. Due to illness Gontermann did not fly the airplane until 26 October. Gontermann considered the Triplane to be "fabulous" but "in any case, with mine I will take my time and feel my way with caution." He had learned the lesson from Wolff's and Voss's deaths.

This first production aircraft was soon followed by 17 more that arrived in late October, then a subsequent batch of five before the end of the month for delivery to Jasta 11, the unit that Richthofen flew with while commanding Jagdgeschwader I, his famous "Flying Circus".

The introduction of the production Triplane into service was traumatic. Vzfw. Lautenschlager was shot down by mistake while flying Dr.I 113/17 by another German fighter aircraft operating in the area of the IVth German Army. The pilot responsible for Lautenschlager's death was to be courtmartialed as a consequence. Upon hearing about this, Manfred von Richthofen intervened and proved that neighboring German units had not been properly informed about the introduction of the new Triplane. The charges were dropped, and the unnamed pilot was later transferred to JG I. Richthofen wrote off 114/17 after an emergency landing due to a cylinder separating from his rotary engine and destroying the cowl. Much worse, on 30 October Ltn. Gontermann was tragically killed when he crashed due to top wing failure, and the next day Ltn. Pastor was killed when the top wing of 121/17 failed in the air. The Triplane was grounded and an investigation was started.

In retrospect a number of technical faults, combined with mediocre quality control during construction, caused the failures of the upper wing and ailerons. The wings of the existing airplanes had to be replaced with new wings. Assembly procedures of the new wings were made more rigorous, the ailerons and aileron hinges were modified for additional strength, and strengthened wing ribs were used. Although not spelled out in the Idflieg requirements, Fokker worried the ailerons were applying too much torque to the wing structure and the aileron balance horn chord was reduced. The Triplane was generally a robust aircraft, but despite the new, strengthened wings, at least three more episodes of wing failure occurred, usually due to combat damage, and fortunately without any further fatalities.