В.Кондратьев Самолеты первой мировой войны

Сопвич "Пап" / Sopwith Pup

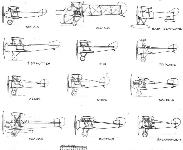

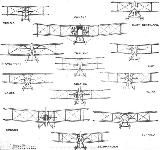

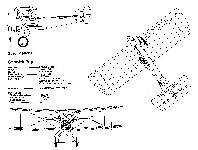

Цельнодеревянный одностоечный биплан с полотняной обшивкой. Автор проекта - инженер-конструктор фирмы "Сопвич Эвиэйшн Компани" Герберт Смит. Самолет представлял собой сильно уменьшенный в размерах и массе вариант Сопвича "полуторастоечного" (отчего и произошло его прозвище "пап", то есть "щенок", позже превратившееся в официальное название).

Прообразом будущего истребителя стал спроектированный Смитом в 1915 году личный самолет известного британского летчика и авиабизнесмена Гарри Хаукера.

"Пап" изначально создавался по заказу руководства RFC и британского Адмиралтейства как легкий одноместный самолет воздушного боя.

Первый полет прототипа состоялся 9 февраля 1916 г. Серийное производство развернуто в октябре на заводах фирмы "Сопвич" в Кингстоне и Бердморе. Кроме того, самолет выпускался фирмами "Стандард Мотор Компани" и "Уайтхэд Эйркрафт". Выпуск завершен в начале 1918г. Всего построено 1847 экземпляров, поступивших на вооружение британской армейской и морской авиации, а также - в части ПВО. Подавляющее большинство машин - 1670 экземпляров - служило в частях RFC.

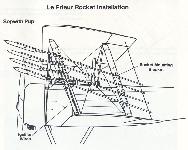

Самолет обычно оснащался 80-сильным ротативным мотором "Рон" 9C, реже - 100-сильным "Гномом моносупапом" и был вооружен синхронным пулеметом "Виккерс". На некоторые машины из частей ПВО дополнительно ставили по восемь ракет "Ле Прие".

Осенью 1916 года первый дивизион, вооруженный "папами" (2-й дивизион RNAS), прибыл на западный фронт. Самолет проявил себя как достойный противник германских "альбатросов", намного превосходя по своим летным данным все типы истребителей, ранее применявшиеся в британской авиации. Особенно высоко оценивалась хорошая горизонтальная маневренность машины, ставшая в дальнейшем "коронной" чертой всех истребителей Сопвича.

Весной 1918-го, в связи с появлением новых типов германских и британских истребителей, "Пап" уже считался морально устаревшим. Его сняли с вооружения фронтовых частей и перевели в учебные подразделения. Несколько экземпляров машины в ходе войны отправили ознакомления в США, Нидерланды, Грецию, Австралию и Россию.

Надо отметить, что "Пап" - первый в мире истребитель корабельного базирования. В 1917-18 годах этими машинами были оснащены семь крейсеров и пять авианосцев британских ВМС, первым из которых стал авианосец "Фьюриес", а также - плавучие аэродромы-баржи, размещенные в Ла-Манше. С них истребители должны были стартовать на перехват немецких бомбардировщиков, совершавших налеты на Англию. Часть самолетов морского базирования оснащалась специальным полозковым шасси.

ЛЕТНО-ТЕХНИЧЕСКИЕ ХАРАКТЕРИСТИКИ

"Пап" 1916г "Пап" 1917г

Размах, м 8,08 8,10

Длина, м 5,89 6,0

Высота, м 2,90 2,90

Площадь крыла, кв.м 23,50 23,60

Сухой вес, кг 358 356

Взлетный вес, кг 556 557

Двигатель "Рон" 9C "Гном-Рон"

мощность, л. с. 80 100

Скорость максимальная, км/ч 179 181

Скорость подъема на высоту

1800 м, мин.сек 6,45

Дальность полета, км 300 450

Продолжительность полета, ч 3

Потолок, м 5330 5200

Экипаж, чел. 1 1

Показать полностью

А.Шепс Самолеты Первой мировой войны. Страны Антанты

Сопвич "Пап" (Pup) 1916 г.

Развитием схемы "Таблоида" стал одноместный истребитель фирмы "Сопвич Авиэйшн Компани" - Сопвич "Пап", выполненный по той же конструктивной схеме одностоечного биплана.

Фюзеляж прямоугольного сечения обтянут полотном. Однако капот двигателя и передняя часть фюзеляжа изготавливалась из алюминиевого листа. Крыло двухлонжеронное, обтянутое полотном, отличалось от крыла "Таблоида" размерами и формой законцовок. Элероны имели большую площадь. Изменилась конструкция горизонтального оперения. Оно стало прямоугольным. Стабилизатор регулируемый. Вертикальное оперение такое же, как на "Таблоиде", но киль имел большую площадь. Шасси с резиновой амортизацией, без противокапотажных лыж. Хвостовой костыль с резиновой амортизацией. Двигатель 7-цилиндровый, воздушного охлаждения, звездообразный, ротативный, мощностью 80 л. с. "Гном-Моносупап" или "Гном-Рон-96". На более поздних машинах - 9-цилиндроый, воздушного охлаждения, звездообразный "Клерже" (100 л. с.). Вооружение самолета состояло из одного синхронного 7,69-мм пулемета "Виккерс" с ленточным питанием. Самолет мог нести четыре 11-кг бомбы. На некоторых машинах устанавливались два пулемета.

В конце 1917 года именно Сопвич "Пап" стали одними из первых палубных истребителей.

Показать полностью

H.King Sopwith Aircraft 1912-1920 (Putnam)

Pup

A rightful and honoured tradition among the hundreds of authors who have published dissertations on the Pup is to characterise it as 'the perfect flying machine’, or something closely akin, and in so doing to honour also the name of Oliver Stewart, whose first-hand knowledge of this aeroplane was so lovingly and memorably expressed in his writings to that effect. Oliver, alas, died when this present book was being planned (December 1976); yet one can still pay tribute to this old friend and at the same time to the Pup - by declaring that he was a man by whom others were measured, and it is certainly no exaggeration to affirm that many of his ways and manners (even, it seemed, his physical characteristics) were consciously or otherwise - reproduced in men around him. So it was with the Pup.

These matters being so, one turns not to Oliver Stewart for an introduction to the Pup, but to a quite exemplary appraisal by Lord Weir of Eastwood, Controller of Aeronautical Supplies and member of the Air Board, 1917/18: Director-General of Aircraft Production, 1918; and - likewise in 1918 - Secretary of State for Air and President of the Air Council. With experienced men to advise him, Lord Weir declared soon after the Armistice:

'The characteristics of the Sopwith Pup, our first good tractor single-seater, were very light surface loading, a small but good rotary 80 h.p. French engine, and every scrap of unnecessary weight eliminated by careful design. The view, particularly overhead, was not very good, but the aeroplane was so handy fore and aft that this did not interfere very seriously with its fighting qualities. The type lasted a very considerable time before it was superseded, which, in view of the comparatively small horse-power, was remarkable. During the period in which this type was in use fighting acrobatics [sic] advanced to a marked degree, and in the next type [the Triplane] an effort was made to increase view and manoeuvrability.'

This last reference to the continuing need for increasing manoeuvrability gives emphasis to the fact that it was not manoeuvrability per se that distinguished the Pup (for that particular attribute was not to be fully realised until the coming of the Camel) though Lord Weir makes special allusion to fore-and-aft handiness, just as Oliver Stewart once mentioned 'the rather powerful and quick elevator'. The Pup's pre-eminent quality in combat was, in fact, its ability to 'hold its height' (in the parlance of those times) as now finally affirmed by Maj Stewart: 'It was this power to hold height during a dog fight that made the Pup a useful aeroplane, and it was this quality that the pilots sought to amplify. By the selection of an appropriate type of airscrew and by lightening the machine as much as possible the height-holding powers were enhanced.'

So much for the significance of the Pup as a fighting machine; and as for its history, it must first be remarked that although manifestly a very near relation of the SL.T.B.P., the traditional ascription of its ancestry to the 1 1/2 Strutter (of which it was supposedly declared by Col Brancker to be 'a pup') is not to be dismissed. This is fairly clear from the fact that 'Pup' was the name insisted upon (if not conferred by) Service pilots, who were familiar with the 1 1/2 Strutter though far less so with Harry Hawker's 'pup' which he liked to take around with him not merely as a pet, but as a development vehicle for a new fighting aeroplane.

Self-evident is the absence from the Pup, or Sopwith Scout as it was first officially known (with or without initial capital for 'Scout') of the salient feature the peculiar form of wing-bracing - which not only identified the 1 1/2 Strutter, but whereafter that type was named. 'So' (as Oliver Stewart summed the matter up) ‘I suppose that [the second of two official orders relating to nomenclature] and the perverse state of mind of the fighting forces when it came to language, both good and bad, accounts for the fact that the aeroplane has ever after been known exclusively as the Sopwith Pup.'

Yet still one has the merest suspicion that the full story of one of the most famous aircraft names in history has not been fully told; for even though Peter Lewis, in his "1809-1914" book, faithfully records that there was built, in 1909, a tiny single-seater called the Neale Pup, it is not explained by Mr Lewis that this same aeroplane was characterised not only by its name, small size and single seat but that (according to an official account) it was built for J. V. Neale at Brooklands, and that this same man later formed an aircraft company at Richmond - obtaining, in fact, a War Office contract for four machines. Both Brooklands and Richmond had strong Sopwith associations, though here, perhaps, we have a chain of mere coincidences.

Whatever the niceties of nomenclature, we now perceive how the "thoroughbred" Pup was really a mongrel by 1 1/2 Strutter out of SL.T.B.P. But that among officially adopted 'scouts' it had a character all its own, in the sharply raked tips of its wings and tailplane, was conveyed by the official recognition drawings.

To do full justice not only to officialdom as well as historical precision, the "Admiralty-system" designation (for the Pup, like the 1 1/2 Strutter, was blooded in operations by the RNAS, and not the RFC) was Sopwith Type 9901.

Though construction was fairly conventional, typically with spruce wing-spars and ribs, ash longerons (earlier spruce) and spruce spacers - or 'transverse struts' and 'side struts', as these last-named members were formally designated - steel tubing was extensively used, not only for the wingtips and trailing edges and for the landing gear, but in the tail - the fin and rudder especially; and visually there were other strongly marked features apart from the sharply raked tips already mentioned. Most prominent among these features was the small size of the four ailerons, contrasting with the large horizontal tail surfaces (the elevators included) the size of these last accounting for the aircraft being, as Lord Weir said, 'so handy fore and aft’. That same minister's critical remark that 'view, particularly overhead, was not very good' (this notwithstanding the more rearwardly positioned cockpit, compared with the SL.T.B.P., and the provision of a trailing-edge cutout) was in some degree met, both experimentally and in service, by the inletting of transparent panels - which unfortunately were prone to splitting - or the provision of non-standard cutouts. Such tampering with wing area was not, of course, compatible with height-holding, and there were even some misgivings at one time (early 1917) concerning the possible effect on performance of a little hole about a foot square only - as a palliative against tail-heaviness.

Possibly in 'the perverse state of mind of the fighting forces' referred to by Oliver Stewart, the first Pup seems to have been criticised by RNAS pilots respecting not only upward view, but 'straight downwards' also, in this last respect being considered inferior to the Nieuport, though otherwise the fields of view were reckoned equal.

The Pup having been regarded above all as a 'pilot's aeroplane', and Oliver Stewart's first-hand knowledge having been so freely drawn upon, it is salutory to consider the affirmations of a pilot hardly less renowned who, though having no first-hand knowledge of the Pup in combat, has nevertheless made a particular study of its design and engineering. Thus Harald Penrose:

'The hand of R. J. Ashfield is discernible in the design of the Pup, and its derivation from the Tabloid is clear when structural drawings of the two are superimposed. The length from stern-post to engine bulkhead is the same; the fuselages have identical depth; and the lower longerons are set at the same upward angle from rear spar to tail, though in plan the Pup is noticeably narrower. Vertical spacer-struts spindled to H-section are displayed in slightly different positions from the Tabloid, but the attachment fittings appear interchangeable, though Pup metalwork had more lightening holes. On a fuselage general arrangement drawing in my possession there is an annotation by Fred Sigrist that the spruce longerons are to be changed to ash in subsequent versions. Wing construction of Pup and Tabloid show further similarities, for the chord is identical, the gap only fractionally different, and spar positions the same, but the Pup's wing stagger is seven inches greater.

'Many features show how attentive Harry Hawker was to the draughtsmen's boards. The wing attachment was his design, and had the simplicity of a flying model of that day, for the butt of each spar was reinforced with a hollow metal ferrule within the end rib, and slid on to projecting ends of the centre-section spars and the lower spars traversing the fuselage. A long thin pin, with localized increased diameter at load points, was externally pushed through a tubular guide in the leading edge and through the spar abutments before emerging through the trailing portion of the wing. An airtight chordwise join resulted, simple and quick to secure compared with separate pin joints enabling the wing cellules to be placed in position or removed while tautly boxed with bracing wires. The original patent was secret, but registered in Hawker's name as No. 113,723, and ultimately dated May 1917. So also was Patent 127,847, protecting the practical and extremely simple method of attaching the annular cowling of the 1 1/2 Strutter and Pup, whereby an encircling groove, formed round the aft end of the aluminium cowl, engaged a similar groove in the nose structure of the aeroplane. A cable passed round the cowl groove and, tightened by turnbuckle, compressed the perimeter into the fuselage groove and locked it in position. It was a system quickly adopted by other makers.

'Because axles slung between the inverted Vs of conventional undercarriages tended to become permanently bowed after several heavy landings, another simple solution was achieved in the articulated axles devised and patented (No. 109.146) by Tom Sopwith and standardized for all his machines. Using two separated horizontal spreaders from apex to apex, he pivoted the half axles between them from a central hinge, springing the hub ends with shock absorber cords wound on studs at the bottom of each undercarriage frame but the crux of the invention was to suspend the central hinge by cable from the fuselage in order to resist collapse as the wheels moved upwards. Compared with sleeving the axle to increase bending strength, it saved several valuable pounds.

'The Pup on early flights had a fixed tailplane like the Tabloid, but slight changes in trim with speed and pilot weight made a trimmer desirable for finesse. To use the nut and worm gear patented for the 1 1/2 Strutter would be unnecessarily expensive, so Hawker devised a simple crank hinged from the stern-post, connecting it at mid-length to a vertical push-tube attached to the rear spar, and operated it with wires running from a diagonal sliding knob on the right side of the cockpit.’

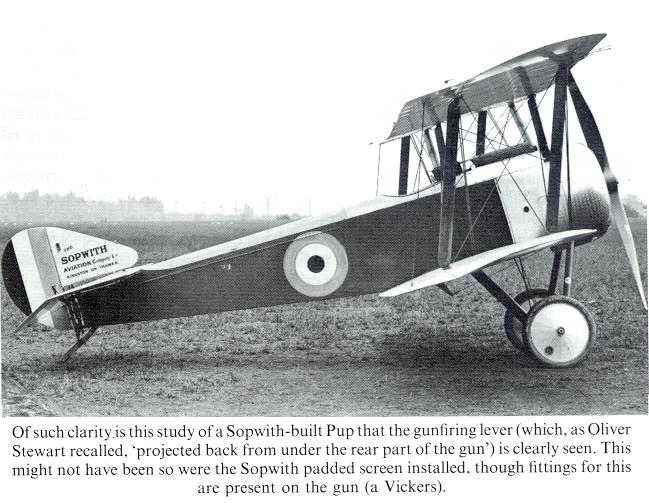

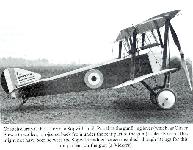

Here it is fitting to note that Mr Penrose's accurate record notwithstanding official notification was given in January 1917 that RFC Pups would have a fixed tailplane as standard. This alteration was, indeed, only one of very numerous modifications made to meet pressing needs or personal preferences. Thus, at various times, tailplane incidence was increased; the landing gear (which had already been somewhat heightened in early-production machines) was strengthened for specialised training applications - for which purpose production was run on into 1918; the 1/3-inch plywood decking round the cockpit was variously cut away; the Sopwith padded screen on the Vickers gun was sometimes abandoned as a further interference with fighting view (one known alternative being a Triplex screen in two halves, one on each side of the gun - though unarmed trainers, for instance, sometimes had an Avro screen): while there were variations too in stagger from the standard 18 inches - eight Sopwith-built Pups, for instance, being turned out with only a 15-in stagger. But among some 2.000 simple aeroplanes (especially when flown by pilots prone to 'perversity'!) alterations must have been vastly more extensive, though the major ones were those later instanced in the context of special Naval applications.

The first Pup was No.3691, which was cleared by Sopwith's experimental department on 9 February. 1916. This example (which had a shorter landing gear and smaller vertical tail surfaces than later versions) may have initially been fitted with a seven-cylinder 80 hp Clerget engine, though a nine-cylinder 80 hp Le Rhone was installed for CFS tests in March. Cierget-powered - initially at least - were the next five Sopwith-built examples (Nos.9496 and 9497 and Nos.9898 9900) and the first eleven built by Beardmore, to which company the initial production contract was transferred, and which was later awarded special Naval development contracts. For the apparently unbuilt N503 a 110 hp Clerget was intended.

With the 80 hp Le Rhone (as made by W. H. Allen, Son & Co Ltd, and in an annular cowling with a segmental slot at the bottom) the Pup airframe became not only chiefly associated but well-nigh identified; and there was wide agreement among Pup pilots that the '80 Le Rhone' (makers' suffix 9C) was the perfect partner - sweet-running and dependable, even when over-revved, as in chases and escapes. (Later a few Pups were fitted with the 110 hp Le Rhone 9J engine, but with this unit - which could, in fact, deliver about 130 hp - airframe-strength suffered quite alarmingly, and already the Camels were coming. The fairly common 80 hp Gnome installation was apparently confined to Pups used for training).

As soon as No.3691 went to the RNAS for service tests in May 1916 (Chingford, Grain and Dunkirk were visited before the aircraft was allocated to 'A' Squadron of No.5 Wing at Furnes, in France) it became apparent that an entirely new class of fighting aeroplane was in Britain's hands - and an ascendancy was established which lasted from the autumn of 1916 until around mid-1917. Although credit for this must go initially to Sopwith (who not only designed the Pup, but together with William Beardmore & Co built large numbers for the RNAS the War Office orders going to the Standard Motor Co and Whitehead Aircraft) it must be recognised that ascendancy over the enemy stands to the glory of Naval and RFC pilots alike. To a member of the first Pup-equipped RFC squadron (No.54) this vivid explanation of that ascendancy is due:

'We attained 18.000 ft with regularity, and could get even higher. Our best chances came from climbing above the maximum height obtainable by the German fighters and then hoping to make a surprise attack. The Germans were always superior in level speed and in the dive, but the Pup was much more manoeuvrable and we could turn inside any German fighter of the day.’ And - as clinching evidence that the Pup did indeed represent an 'entirely new class of fighting aeroplane', as already declared: 'The winter of 1916-17 was bitter in Northern France, and at 18.000 feet everything froze - the engine-throttle, the gun, and the pilot... The aircraft itself always behaved in a most gentlemanly way, but it needed careful handling - a dive of 160 m.p.h. was fast enough, and at 180 m.p.h. the wings were definitely flapping and a gentle recovery was essential, since to lose a wing when one had no parachute offered no future.’

Curiously, this same officer went on to describe the Pup's lightness - one of its great advantages in combat, as earlier established in this chapter - as its 'one disadvantage’, though this was in the context of ground-handling, which, in a strong wind, entailed the calling-out of all available personnel when a patrol was landing-back to seize the wingtips before a gust could blow the aircraft over. Here we have an inter-Service parallel, as well as a technical one, with the famous picture of an RNAS Pup being literally hauled out of the air by a deck-party using rope toggles affixed to the aircraft.

The first RFC Pup squadron was, as already noted. No.54, which arrived in France on Christmas Eve 1916; but considerably earlier by late October - one flight of No.8 Squadron, RNAS, had been equipped, and the Pup's first recorded victory had, in fact, been chalked up on 24 September, when F Sub-Lieut S. J. Goble, of No. 1 Wing, RNAS (later Chief of the Air Staff. R. Australian A.F.), shot down an L.V.G. in flames. By this time the 'image' of the First World War fighter pilot was forming the man in the warm-lined leather coat, with silk gloves under leather gauntlets, sheepskin boots, and perhaps on exposed facial areas - whaleoil.

A consistently successful Pup pilot was, of necessity, a good marksman, for the Pup was armed as standard with a single Vickers gun only, installed as on the 1 1/2 Strutter in conjunction with a Sopwith padded screen and initially Sopwith-Kauper synchronising gear, though some later aircraft had the Scarff-Dibovsky (mechanical) or Constantinesco (hydraulic) gun-gear. As was the case with the 1 1/2 Strutter, there was a non-standard installation of the Vickers gun on the port upper longeron, and there were several unofficial - and generally unsuccessful installations of a Lewis gun above the centre-section.

The Pup's 'perfection' was, of course, relative, and this was manifest not only in criticisms of its field of view and too-light armament (one Vickers gun being standard) but in the difficulty, in late 1916 at least, of holding the sights on-target in a fast dive by reason of a 'surging' motion in the 'up and down' plane. Another point concerning armament was that while the Pup was becoming established in service (early 1917) so, also, was an innovation in feeding the ammunition by the use of the Prideaux disintegrating-link belt. Previous to this, sodden, frozen, swollen or damaged belts (even though these were stoutly made of webbing) had given trouble to the Army and the flying Services alike, and non-disintegrating belts had been briefly tried by the Army in France, though they were never standardised. For aircraft use the Vickers gun presented a particular problem because the used portion of the fabric belt had somehow to be stowed away snugly and safely, where it would not (for instance) seek to reintroduce itself into the gun or create special kinds of mischief to which aeroplanes were sensitive. By making the cartridges themselves form the hinge-pins, the metal links (which were expelled from the side of the gun) and the spent cartridge cases (which came out through the bottom of the gun) could be more conveniently disposed of through chutes, though with the new form of belt the Pup's ammunition box could hold only 350 rounds instead of the specified 500. Removal of the original receptacle for the used webbing belt, however, permitted restoration of the full ammunition supply.

The summer of 1917 found the Pup outclassed in France but still an attractive proposition for Home Defence - especially with the 100 hp Gnome Monosoupape engine to improve the rate of climb and ceiling. Here the light drum-fed Lewis gun came in for special consideration as a top-plane fitment partly to obviate firing 'special' ammunition through the propeller arc; and the great McCudden made himself a 'rough sight of wire and rings and beads' for such an installation.

The ‘H.D.’ Pups which had the 100 hp Gnome Monosoupape engine an installation which had, in fact, been projected early in 1916 for the second and third Sopwith-built examples (Nos.9496 and 9497) though not then implemented were distinguished by a longer, open-bottomed cowling, which was further characterised by four auxiliary lips to admit cooling air, these lips being set in a group round the upper-starboard segment of the rim. (There were, nevertheless, instances of Le Rhone engines in cowlings of similar form). The greater power of the 'Mono Gnome' gave an appreciably better rate of climb; and it may well have been this attribute which, early in 1918, prompted a member of Flight's staff (one seems to recognise his brand of humour from having shared an office with him long ago) to comment in excruciating style on an article by Sous-Lieutenant Viallet in La Guerre Aerienne, this article having the title Considerations sur les Avians de Chasse. The comment made was that the French article dealt chiefly with 'a popular British aeroplane' styled as the Sopwith "Pop". 'Is this', enquired Flight's humourist, 'because it is a machine which has given the Boches ginger, or is it because the useful little scout flies upwards like a cork out of a bottle?" With a 170 hp A.B.C. Wasp radial performance wherewith reached the calculation stage by Sopwith - it should have ascended like a cork out of a magnum; but although in postwar years a Pup in Australia was, in fact, fitted with a radial engine, this was an Armstrong Siddeley Genet of only about 80 hp - and the Pup was no longer in the fighting business.

Certainly the wartime Pup had latterly become an intercepter as well as a dog-fighter, and one must note again that by early 1918 it was still 'flying upwards', although it had (in the past tense) given the enemy ginger in France. Yet what it had really done was far more than has so far been related here; for though its operations with land-based units of the RNAS have already been touched upon, its contribution to 'ship flying' (as it was known) was basic, wide in scope and exceptionally interesting in the purely technical, as well as the operational, sense. That no separate chapter on a special 'ship's Pup' is appended, as was the case with the 1 1/2 Strutter, is explained by the fact that, although such an aeroplane did indeed exist, it was a Beardmore, and not a Sopwith, development; but before passing attention is paid to this very highly specialised machine, praise must be accorded to the contribution made by (more or less) 'ordinary' RNAS Pups to the techniques of flying from ships for these were very great indeed.

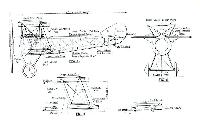

Though landing gears of various sorts were much involved in the work to be discussed (but never floats, as on the Schneider and Baby, it must be emphasised) the first point to be mentioned concerns not the under-part but the overhead centre section; for though the first Pups built by Sopwith for the RNAS (N5180-N5199) were fitted, as standard, with the same form of centre section as the company's Pups for the RFC, there was soon a special Naval requirement for an aperture to be formed between the spars - not. as was the case with some modifications, to improve the pilot's view, but to allow a Lewis gun - mounted on a tripod of steel tubes forward of the cockpit to fire upwards, especially at Zeppelins. This feature was characteristic of the 'Sopwith Type 9901' as built for the RNAS by Beardmore, though, as the Service named was from the earliest times much concerned with the attack of airships, the Beardmore-built Pups - with or without the Lewis gun sometimes had provision for eight strut-attached Le Prieur rockets.

By no mere carelessness or contrivance has this particular part of the narrative - dedicated, as just declared, to the techniques of flying from ships turned towards armament. This turn is readily explained by twin considerations: first, that the Navy did not fly from ships for fun or danger-money, but to serve the Fleet; second, by its particular preoccupation with armament of many forms - best exemplified by Scarff, with his gun mountings, gunsights, synchronising gears and bombsights. Thus it is fitting now to give a note concerning the rockets just named - especially so as they will be mentioned again in the Camel context. Historically, perhaps, there is an even more compelling reason, for the Le Prieur rocket was a stick-stabilised weapon and, as such, a latter-day development of such patterns as the Congreve, deployed by the Royal Navy in the early 1800s. A development by Lieut Y. P. G. Le Prieur of the French Navy (who also designed some complicated gunsights - rivalling in complexity those devised by Scarff) the French rocket gained no high reputation, although it was officially recognised that some early specimens had been damp. Firing was electrical, from steel launching-tubes, and mean velocity about 330 ft per sec - the intended targets being, of course, Zeppelins.

But from airships we must now firmly turn to surface ships; and with those of the Royal Navy, No.4 (Naval) Squadron had been well acquainted after equipment with Pups in March 1917 undertaking not only offensive patrols (fighting Albatros scouts, for instance) but close-protection also. From May 1917 Naval Pups flown from Walmer, between Deal and Dover (at which last-named British stronghold there were also Pups) escorted and protected merchant ships and seaplanes alike - speed-difference between the patrolling Pups, which had air-bags for emergency flotation, and even the merchantmen, being relatively small; and in July of the same year Pups superseded some Sopwith Baby seaplanes when they (the landplanes) took up station with the Seaplane Defence Flight, operating from St Pol, across the Strait of Dover.

Though the high-flying Gotha bombers were by no means easy meat even for a Pup, Flt Lieut H. S. Kerby, manning a Pup attached to Walmer, sent a straggler into the sea.

The flying of Pups from ships - with anti-Zeppelin work especially in view - dated from early 1917, when it was recommended that machines of this type should replace Sopwith Babies aboard aircraft carriers (Campania and Manxman were first proposed), cruisers and other last vessels. Now was the time when the fitting of emergency flotation gear, as well as the special 'Naval' armament earlier described, came in for particular attention together with the services of an officer who had already done much for the glory and efficiency of British Naval flying. This officer was Flt Cdr F. J. Rutland (Rutland of Jutland) who was, perhaps, the Navy's strongest advocate and most determined practitioner in the flying of Pups from ships.

Like Harry Hawker after him (see under 'Atlantic') Rutland contended that it would be safer to ditch a buoyant landplane than to trust oneself to an alighting in a seaway with an inherently frail floatplane; and in any case, he argued, the Pup was the only aircraft that could tackle a Zeppelin near its ceiling. (The first Pups actually delivered to a ship may well have been Nos.9910 and 9911, which went to HMS Vindex following their acceptance on Boxing Day 1916).

With an air-bag lashed inside the narrow rear fuselage of a Pup - much the same arrangement as Bleriot had used to fly across the English Channel in 1909, and much the same also as employed on Hawker fleet fighters of many years later the aforementioned Rutland took-off from HMS Manxman on anti-Zeppelin patrol, but was forced to ditch off the Danish coast, where his Pup remained afloat for twenty minutes only. The date was 29 April, 1917; but on 23 June flotation tests were put in hand on the first Beardmore-built Pup, 9901, moored off the Isle of Grain and having a trial installation of ‘Mark I Emergency Flotation Bags'. To confer on the Pup improved flotation qualities these were of inflatable type their inflation being unconfined, moreover, because they were externally attached (to the undersides of the bottom wings where, while deflated, they lay flat). On this occasion the Pup stayed afloat not for twenty minutes only but for more than six hours.

Another Pup experiment at the Isle of Grain involved the fitting of a jettisonable landing gear, with which, nevertheless, the Pup tended to overturn on ditching. Greater success was achieved when hydrovanes were fitted under the fuselage and on the tailskid.

Early shipboard operation now being our chief concern - with credit being accorded, as due, to the Pup (as to the 1 1/2 Strutter) for its suitability and adaptability - one feels bound to emphasise that careful thought had been given long before the war of 1914 to the use of aeroplanes not only from specialised aircraft-carriers, but from other British Naval vessels also. The following was, in fact, written pseudonymously in 1911:

'Aeroplanes may be carried either in large numbers in a specially built mother-ship, or one or two in every large battleship or cruiser.’ (How remarkably accurate this was to prove is clear from a Naval officer's post-Armistice affirmation, already recorded, that 'My ship carried one Camel and one 1 1/2 Strutter'). The 1911 quotation continued: ‘In the case of the mother-ship the stowing space can be made ample. Also, she can be fitted with large decks or any cumbersome but convenient method of starting the aeroplanes. In fact, she can have all the luxuries of an aerodrome. In a mother-ship the aeroplanes would be well looked after, while in a man-of-war they might lack sympathetic treatment. This however, once aeroplanes have established their utility, will be grown out of. In all probability aeroplanes, at first, will be carried one in every big man-of-war. In that case the aeroplane will have to make the best of what it finds there. It will be stowed, mostly in bits, up among the boats. A tarpaulin cover for its engine will be its hangar. No special arrangements will be fitted unless they are small and unobtrusive, unless they in no way detract from the fighting or sea-going efficiency of the ship.’

And - the saltiest and most sagacious touch of all, having special regard to flotation gear and flying-off platforms, which are very much our present concern::

‘The deck space will always be too limited to permit a return to it, and so the return will always be made to the water. On his return the aviator will be picked up and his machine hoisted in. If it is not boating weather, well, probably the machine won't be flying…’

Against these remarkably prophetic ruminations of 1911 we may now set this backward glance in 1919 noting especially the name 'Deck Pup'. Thus: 'One of the remarkable features of the war has been the way in which all classes of ships (excepting destroyers) have been equipped to carry and fly off small aeroplanes from barbette crowns [i.e. turret tops] in big ships, and from small platforms in light cruisers. In the Carlisle and "D" types of light cruisers, a high "Arc de Triomphe" hangar has been combined with the fore bridges, the fore portion of which can be closed by wind screens or roller shutters.' The reason for this 'huge' structure was thus explained: 'The small Sopwith "Camels" and "Deck Pups" carried in our warships have to attain their flying speed with a remarkably short run, on account of the limited length of flying-off platform. So anxious are they to get into the air, they tend to rise by themselves when the carrying ship is steaming into a head wind. Lashing down the 'planes resulted in straining. Accordingly, small wind screens have sometimes to be rigged round the aeroplanes. But wind screens are a nuisance to rig or unfurl in a rising wind hence the permanent structures adopted in new light cruisers.’

Although the design of post-1919 cruisers is not of present concern, the contribution made by the Sopwith Pup to operations from this class of ship assuredly is; and so it must now be recorded that on 28 June, 1917, Flt Cdr Rutland pursued his experiments by flying a fully armed Pup from a 19 ft 3 in (5.8 m) platform fixed in position over the forward 6-in gun of the 5,250-ton light cruiser Yarmouth (so that for launching, the ship had to steam into wind) leading to a decision in the following August that one ship in each light-cruiser squadron should be fitted with a flying-off area. Earlier Rutland had used and this from the slower Manxman - a platform of only 15 ft 6 in (4.7 m). Thus this particular platform was shorter even than the tiny Pup itself.

On the warlike side, Flt Sub-Lieut B. A. Smart, flying a Pup from the pioneering Yarmouth on 21 August, 1917, shot down Zeppelin L.23. Clearly, this particular Pup had received the 'sympathetic treatment' that the gentleman writing in 1911 thought it 'might lack', though it sank before similar attention could save it.

A few lines earlier in this present account the displacement-tonnage of Yarmouth (5,250) was deliberately quoted to emphasise the relatively small size of a light cruiser as compared with the converted 'light battle cruiser' Furious (roughly four times as much) - Furious being a vessel concerning which there will be far more to say. Meanwhile it may be remarked that, resembling as she did a big destroyer Yarmouth's success stimulated the notion of providing even destroyers and other small craft with aeroplanes (the 'Kittens') though that particular notion came to naught. The war had not long been over, however, when Yarmouth had the then-unrecognised distinction of carrying (as an observer of atmospheric conditions in far lands) a man - Robert Watson-Watt - whose contribution to his nation's defence was in later years to prove certainly no less in value than that of the Sopwith Pup. (HMS Yarmouth herself had served at Jutland also, but was sold in 1929).

Whether or not a Pup was ever catapulted is uncertain, though in May 1917 two or more Beardmore-built examples were sent to Hendon for that purpose; but given a cruiser's speed, a modest platform, a headwind (and, of course, a fittingly 'sympathetic' bunch of officers and deck-hands) what would a Pup need with a catapult? One reflects, in fact, that if a Pup had been fitted with rockets as take-off assisters instead of as 'R.P.s' as already related, it would have run well-nigh the entire 'modern' naval operational gamut (VTOL, of course, being taken for granted).

In the matter of launching, the basic difference between flying-off an aeroplane from a fixed platform, as instanced by that on the light cruiser Yarmouth, and performing a comparable operation from a turret platform (of the kind already mentioned in connection with the 1 1/2 Strutter) aboard a capital ship having rotating turrets for heavy guns - i.e., a battleship or battle cruiser was that the latter ships could rotate the turret/platform combination, or 'turntable', into the 'felt' wind, instead of having to steam into wind. Thus they could maintain a course. For testing the Pup from a capital ship the chosen vessel was the battle cruiser Repulse, and the pilot Flt Cdr F. J. Rutland, whose name has already been acclaimed as 'perhaps the Navy's strongest advocate and most determined practitioner in the flying of Pups from ships'. The first trial was on 1 October, 1917, using a downward-sloping platform on 'B' turret. This trial having proved successful, the platform was transferred to 'Y' turret, and on 9 October Rutland took-off again - on this occasion not over the guns, but over the rear of the turret. By this time, however, the Camel 2F.1 was well advanced in development, and, together with the 1 1/2 Strutter, vas standardised for shipboard use.

The problems of landing an aeroplane on a ship's deck did not arise like a mountainous sea in the course of naval-flying development as some accounts suggest; nor would it be justice to ascribe to any particular proposal its realisation as a workaday procedure. In token whereof it is needful only to remember that as early as 18 January, 1911, Eugene B. Ely had placed a Curtiss pusher quite firmly down aboard USS Pennsylvania. Yet the way ahead was still a rough one, involving in particular the Sopwith Pup and HMS Furious, which joined the Grand Fleet in July 1917 the month after the Rutland/Yarmouth/Pup experiments already recorded.

To HMS Furious now one turns attention - a ship which had the well-nigh incredible distinction of having operated Sopwith Pups in the First World War and Hawker Sea Hurricanes in the Second; so if the Pup was sired by the 1 1/2 Strutter, then it had as its foster-mother-ship a vessel with a history no less curious and distinguished than its own. Although launched in April 1916 as a 'light battle cruiser' designed to have a main armament of two 18-in guns (the Navy's standard then being 15-in) she was completed in March 1918 as an aircraft-carrier - of a kind. The essence of the alteration was in deleting the forward big gun and in building ahead of the ship's superstructure a 228-ft (69.4 m) flying deck, with a hangar below it. In this hybrid form the vessel served from June to November 1917; then the second big gun (aft) was removed and the original flying-provisions more or less duplicated. The ship was re-commissioned on 15 March. 1918, and of her Sopwith links thereafter there will be more to say under the heading of '2F.1 Camel'. Before returning to the Pup, however, let it be recorded that, after yet another rebuilding, chiefly in 1924 (whereby she was given a virtually unobstructed full-length flight deck. Furious had aboard at one time or another Hawker Nimrods and Ospreys, Gloster Sea Gladiators - and the aforementioned Sea Hurricanes. In 1948 she was sold to be broken up.

The Pup and the Furious established this incomparable Sopwith Hawker connection in the manner following already preceded (as earlier intimated) not merely by paper proposals but by the American Ely's example of 1911.

At the Isle of Grain in March 1917 (the very month in which Harry Hawker's compatriot Harry Busteed was posted there to command the Port Victoria Repair Depot) Pups 9912 and 9497 - the latter deserving a special place in the history of deck-flying as perhaps the most frequently and extensively adapted experimental machine of 1914-18 - had been employed for deck-landing experiments using a dummy deck - a device originally utilised considerably earlier (September 1916) in developing arrester gear involving transverse ropes and hooks, though it could not, of course, contribute to the 'felt' wind like a ship under way. By February 1917 a new and larger deck, circular in outline, was being used at Port Victoria by (in addition to an Avro 504C) Pup 9497, this machine having a rigid hook for engagement with transverse ropes supported on 2-ft posts and weighted with sandbags. The lime was now approaching when operational aircraft could be landed back aboard a ship instead of being ditched, though flotation gear was still a 'must'.

With her forward flying-deck installed, HMS Furious was made available, as noted, in June 1917, and on 2 August following, Sqn Cdr E. H. Dunning so manoeuvred his Pup by 'crabbing' ahead of the ship's superstructure (or 'Queen Anne's Mansions'), with Furious steaming at about 26 kt, that he became incontestibly the first man in history to land an aircraft on an aircraft-carrier - indeed on a ship of any kind while she was under way. On 7 August Dunning gave a repeat performance (though slightly damaging the Pup); but shortly afterwards, following a third touch-down the engine of the Pup involved (on this occasion known to have been N6452 - five Pups in all having been shipped) choked on being opened-up again. The Pup went over the starboard bow and Dunning was drowned.

It is important here to emphasise that Dunning was using no elaborate arrester gear, depending almost solely on the low landing-speed and general handling qualities conferred by the Sopwith company on the Pup - though also on the seizure (by the ready hands of a deck-party) of rope toggles, attached to the fuselage and bottom wings.

In November 1917 - within weeks, that is, of Dunning's demonstrations - Furious came once more into the hands of the dockyard mateys, and in about three months only had her aft big gun removed and, in its place, an after flying-deck (284 ft or 86 m) with associated hangar fitted prior to her re-commissioning on 15 March, 1918. This fact is restated and amplified here because it accelerated work in hand at Grain (under Busteed's supervision) on special forms of landing gear for the Pup, of deck arrester gears and other equipment. Jointly with modifications to Furious herself, such developments showed the way to the 'classic' or 'modern' form of aircraft-carrier. Instead of wheels, skids of several patterns were designed, and tested on Pups, the definitive skid-equipped aeroplane being officially known as the Sopwith Type 9901a. Though the skids on this new standard production-type Pup were of plain wooden construction (the wheel-equipped Sopwith Type 9901, as built for the RNAS by Beardmore, having already been introduced in this account with special reference to armament) experimental skids - sprung and otherwise, and sometimes with adjuncts and variations - were given close attention. On the Type 9901a 'dog-lead' clips were sometimes fitted to engage fore-and-aft arrester cables - athwartship cables (though not in themselves by any means new) being a particular feature of the Armstrong Whitworth arrester gear. One form of this gear (for which L. J. Le Mesurier appears to have been largely responsible, as he also was for catapults designed by the same company) had flexible transverse 'loops' formed on fore-and-aft cables passing over pulleys and working in conjunction with an hydraulic cylinder.

Though athwartships and fore-and-aft cables were schemed, and sometimes tried, in various proprietary, official proprietary, official, demi-official, unofficial and 'non-attributable' combinations, the frequently-modified Pup N6190 (Sopwith-built, with 15-in instead of 18-in stagger) can be specially mentioned for its part in testing one form of Armstrong Whitworth arrester gear.

Curiously perhaps, the experimental adjuncts to the aircraft did not generally include wheels, though these had certainly been foreseen - in connection, for instance, with an Armstrong Whitworth arrester scheme - and were, of course, later standardised for deck-landing fighters. It fell, in fact, to the Parnall Hamble Baby Convert (with skids instead of floats as on the Sopwith Baby, though with wheels in addition to the skids) to reverse the historic Tabloid landplane transformations - first to the 1914 Schneider racer and then to the Schneider and Baby naval seaplanes.

Experimental Pups used for deck-landing development work included:

- Pup (N6190 identified) with forward extensions to skids and with arrester hook, for athwartships cables, attached at about mid fuselage. (A similarly 'hooked' Pup also had clips or horns of V form, to engage fore-and-aft cables).

- Pup with sprung skids and short, underslung, forwardly located arrester hook. (The springing was achieved by retaining basic components of the standard wheel gear, complete with shock-absorber cords).

- Pup with fuselage-attached arrester hook and bow-shaped propeller guard on forwardly-extending skid-like members.

- Pup with friction attachment on the tailskid.

- Pup with wheel-cum-skid (or embryonic-skid) landing gear, nine claws or horns on spreader bar, and combined hydrofoil/propeller guard.

These foregoing are merely instanced as illustrating the adaptability, as well as the tractability, of the Pup as a ship's aeroplane; and though such developments which stand largely to the credit of the Isle of Grain RNAS station. Port Victoria; Sqn Cdr Harry Busteed personally; and private contractors like Armstrong Whitworth - do not come strictly within the Sopwith compass they must not pass unheeded. Nor can one fail to mention the fitting of a Pup with paired, grooved tandem wheels fixed outboard under each bottom wing to run along parallel wire cables above a ship's deck, thus obviating altogether a flying-off platform. Yet cable-launching - retrieval even, as also tried with a Pup by engaging a loop on an overhead cable - was already old, having been demonstrated by Pegoud on a Bleriot before war came in 1914. Wooden troughs to accept the wheels of a Pup and ensure a straight take-off were a less exotic notion, and were, indeed, fitted to several ships; but to conclude our study of the Pup as a Service aeroplane, and not as an experimental vehicle, we must return to our deliberately early mention of the Beardmore company.

The award to Beardmore of the first large Pup contract for the Admiralty and the special armament provisions connected with this early association having been recorded, it remains to note that the Sopwith Pup aeroplanes ordered as such from William Beardmore & Co Ltd., Dalmuir, Dunbartonshire, Scotland, were Nos. 9901-9950 and Nos. N6430-N6459. From these aeroplanes 9950 was selected for a metamorphosis - a transformation, at least, which represents one of the most imaginative (if one of the less successful) Naval-air undertakings on the British technical record, spattered though this record is with 'make-dos', ‘mods' and 'variants'.

Stowage-space for Pups in the smaller classes of vessel involved in Naval operations generally and anti-Zeppelin work in particular being clearly at a premium, Beardmore undertook a complete redesign of the Pup accordingly. Not only were the wings (now without stagger, and with less dihedral) adapted to be folded 'Folding Pup' being a popular name for the aircraft but the landing gear likewise was largely 'retractable' into the fuselage. Later the gear was fixed, but could be jettisoned for emergency alighting at sea. Flotation gear, jury struts and wingtip skids were added in the early stages, the control system was redesigned and the fuselage slightly lengthened all these features being connoted by the new designation W.B.III. Though some of the novelties were abandoned or mitigated, one hundred W.B.IIIs were ordered; and though not all reached Service units, at one time the carrier Furious had fourteen of her own.

From Kingston-on-Thames, through ferocious battles over lands and coasts and narrow seas, the Pup - most affectionately remembered of all fighting aeroplanes, and an object-lesson in design - had played all kinds of tricks at the airman's and sailor's behest. And if Oliver Stewart's long-acknowledged verdict 'The perfect flying machine' was not sustained in every transformation, then this could seldom have been the fault of The Sopwith Aviation Co Ltd., which later sought in vain to perpetuate that acknowledged perfection, as we shall later be seeing under 'Dove'.

In small numbers Pups went to some of Britain's Allies (Australia had eleven or more in 1919); and the following examples passed to the British Civil Register: G-EAVF (scrapped 1921); G-EAVV (scrapped circa 1921); G-EAVW (scrapped 1921); G-EAVX (not repaired after an accident in 1921); G-EAVY (scrapped circa 1921); G-EAVZ (scrapped circa 1921); G-EBAZ (scrapped 1924); G-EBFJ (scrapped 1924). The famous 'Shuttleworth Pup' was G-EBKY, converted from a Dove, as noted under the appropriate heading.

Though precise production is indeterminate (some aircraft, for instance, being delivered as spares) nearly 2.000 Pups were ordered, contractors and numbers being as follows:

- Sopwith 3691; 9496-9497; 9898-9900; N5180 N5199; N6160-N6209; N6460-N6479 (N6480-N6529 ordered but cancelled).

- Beardmore 9901-9950; N6430-N6459

- Standard A626-A675; A7301-7350: B1701-B1850: B5901-B6150; C201-C550

- Whitehead A6150-A6249; B2151-B2250; B5251-B5400; B7481-B7580; C1451-C1550; C3707-C3776; D4011-D4210. (The last two Whitehead batches were delivered as spares).

Pup (80 hp Le Rhone)

Span 26 ft 6 in (8.1 m): length 19 ft 3 3/4 in (5.9 m); wing area 254 sq ft (23.6 sq m). Empty weight 787 lb (357 kg): maximum weight 1,225 lb (555 kg). Maximum speed at 5,000 ft (1,520 m) 105 mph (169 km h): maximum speed at 11.000 ft (3,350 m) 101 mph (162 km h); maximum speed at 15,000 ft (4,570 m) 85 mph (137 km/h); climb to 5.000 ft (1.520 m) 6 min 25 sec: climb to 10.000 ft (3.050 m) 16 min 25 sec; climb to 15,000 ft (4,570 m) 32 min 40 sec: service ceiling 17,500 ft (5.330 m); endurance 3 hr.

Pup (100 hp Gnome Monosoupape)

Span 26 ft 6 in (8.1 in): length 19 ft 3 3/4 in (5.9 m): wing area 254 sq ft (23.6 sq m). Empty weight 856 lb (388 kg): maximum weight 1.297 lb (588 kg). Maximum speed at 6.500 ft (1.980 m I 107 mph (172 km h):maximum speed at 10.000ft (3,050m) 104mph(167km h); maximum speed at 15,000 ft (4,570 m) 100mph(161 km/h); climb to 5,000 ft (1,520 m) 5 min 12 sec; climb to 10.000 ft (3,050 m) 12 min 24 sec: climb to 15,000 ft (4.570 m) 23 min 24 sec; service ceiling 18,500 ft (5,640 m); endurance 1 hr 45 min.

Показать полностью

P.Lewis The British Fighter since 1912 (Putnam)

Both projects came to naught but a bright star was rising in the rapidly-developing single-seat firmament with the appearance early in 1916 of the Sopwith Pup. Compact and well-balanced in design, the machine did not betray by its performance and handling qualities the confidence which its appearance inspired. Pilots were unanimous in their unqualified praise for the new product from Kingston. The construction of the Pup, known originally to the R.F.C. as the Sopwith Scout and to the R.N.A.S. as the Sopwith Type 9901, was of standard wood and fabric style and carried on the successful type of split axle undercarriage pioneered by the Sopwith Company. The 80 h.p. le Rhone was chosen to power the Pup, which carried a single Vickers gun fixed on the decking in front of the pilot and synchronized with the Sopwith-Kauper gear. The first six prototype Pups went to the R.N.A.S. and production examples followed in the Autumn of 1916. Ship-board versions featured an alteration in armament in which a Lewis gun was carried on a steel-tubing mounting so that it fired upwards at an angle through the centre section cut-out.

The Pup was a success from its first appearance in service and continued to display its superiority over adversaries throughout 1917, contributing valuable assistance in the day-to-day operations in the air war.

Показать полностью

F.Mason The British Fighter since 1912 (Putnam)

Sopwith Pup

As far as any aeroplane of the First World War could be described as a ‘pilot’s aeroplane’, the delightful little Sopwith Scout - universally known as the Pup, other than in official documents - certainly deserved that description. It is said that the design of the Pup was motivated by the ascendancy of German fighting scouts during the latter half of 1915 and the urgency to give the British flying services an aeroplane that could meet the enemy on equal terms. This urgency clearly dictated the utmost simplicity of design and manufacture, and at least one happy circumstance contributed to the tactical excellence of the Pup in service: the long-awaited availability of front gun interrupter gear, so that almost all Pups were armed with a single forward-firing Vickers gun equipped with Sopwith-Kauper mechanical synchronizing gear.

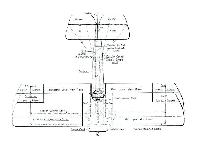

It is difficult to conceive a simpler airframe structure than that of the Pup. The fuselage comprised a box girder made up from ash longerons and spruce spacers, the whole structure wire-braced and surmounted by curved decking formed by stringers. Aft of the front fireproof bulkhead, structure rigidity was achieved by diagonal ash struts. The equal span, single-bay wings were moderately staggered and the cabane struts were splayed outwards to provide a broad centre section which was generously cut away over the pilot’s cockpit. The wing structure was built up on twin spars of spindled spruce with spruce ribs and ash riblets; steel tube was employed in the wingtips and fin, rudder and elevator, as well as the tailplane spar on which the elevator was hinged. The V-struts of the undercarriage were of plain steel tube, and the split wheel axles were sprung by rubber cord, the latter arrangement being patented by T O M Sopwith himself. Relatively small ailerons were fitted on upper and lower wings. At first glance the Pup might appear to be a diminutive offspring of the Sopwith 1 1/2-Strutter - and it was this that may have caused the name Pup to become common usage.

The prototype Pup, No 3691, was passed by Sopwith’s experimental department on 9 February 1916 and was first flown by Harry Hawker at Brooklands almost certainly before the end of that month. Numerous influential visitors from the War Office and Admiralty visited Brooklands to watch the Pup on test, and it was evident that large production orders would be forthcoming. Sopwith was, however, already heavily engaged in producing 1 1/2-Strutters, and it was necessary to initiate considerable sub-contract manufacture, three companies, William Beardmore, Standard Motors and Whitehead Aircraft, being contracted to contribute the lion’s share of Pup production. Meanwhile Sopwith produced five more prototypes, all powered by 80hp Clergets.

Sopwith was, however, primarily an Admiralty contractor, and all six Pup prototypes were delivered to Admiralty charge; and it was for the RNAS that the first production order was placed, for 20 Pups built by Sopwith (N5180-N5199) and powered by 80hp Le Rhone engines. With this modest power the Pup possessed a sea level maximum speed of 111.5 mph, and maintained a top speed of over 100 mph up to around 12,000 feet - a performance not previously matched by any fully-loaded British scout.

The first production Pups began appearing in September 1916 and by the end of that month were being flown by No 1 Wing, RNAS, and had gained their first victories over enemy aircraft. (One of the prototypes had been sent out to France in May for operational trials with Naval ‘A’ Fighting Squadron.)

While Sopwith-built Pups were being delivered to the RNAS in a steadily growing trickle, those destined for the RFC (produced initially by Beardmore) were even slower to materialise, although the first to be delivered arrived on No 54 Squadron, commanded by Maj Kelham Kirk Horn mc, at Castle Bromwich, also in September.

It was a measure of the administrative constraints imposed by the War Office and Admiralty that, despite the heavy aircraft losses suffered by the RFC in the Battle of the Somme during the summer of 1916, there were no means to allow Sopwith to supply Pups to the War Office. Instead, when Sir Douglas Haig appealed to the War Office for reinforcements, the Admiralty - with Cabinet approval - decided to form a new RNAS Pup unit, No 8 (Naval) Squadron on 25 October, under Sqn Cdr G R Bromet (later Air Vice-Marshal Sir Geoffrey, kbe, cb, dso, raf), a Squadron that was to gain immortality with a succession of Sopwith aircraft during the next two years; although only one Flight was initially equipped with Pups, it was soon shown that these aircraft were so much better than the Nieuport Scouts and the 1 1/2-Strutters, and Pups quickly re-equipped the whole Squadron. Within a month the Pups had shot down twenty enemy aircraft, and in February and March 1917 two more units, Nos 3 and 9 (Naval) Squadrons had been equipped with Sopwith-built Pups. During the period immediately before the Battle of Arras, which opened on 9 April, No 3 Squadron, based at Marieux under Sqn Cdr Redford Henry Mulock (later Air Cdre, CBE, dso, raf), destroyed so many enemy aircraft that the Germans began deliberately to avoid combat with the Pups - at a time when other Allied aircraft were suffering catastrophic losses.

Meanwhile No 54 Squadron had completed its working up with Pups and had moved to France on Christmas Eve 1916, and by April the only other two RFC Squadrons to fly these aircraft in France, Nos 46 and 66, had also reequipped. The latter Squadron in particular, commanded by Maj (later Air Vice-Marshal, obe, mc, afc, raf) Owen Tudor Boyd, was very heavily engaged during the Battles of Arras and Messines. No 54 Squadron’s Capt (later Gp Capt) William Victor Strugnell won two Military Crosses when, over a period of three months, he destroyed seven enemy aircraft, the first during the Battle of Arras.

The numerous combat successes by this handful of Pup squadrons during ‘Bloody April’ demonstrated all to clearly that the system of aircraft supply from the factories needed radical overhaul, and that had the Sopwith Pup not taken eight months to begin to emerge from the production lines in 1916, the RFC would have been adequately equipped to meet the emergency that threatened in France in the spring of 1917.

By the autumn of that year the Pups’ single Vickers gun was no longer able to match the new, more heavily armed German scouts, and it was replaced in France by the Sopwith Camel. At home, however, Pups had begun delivery to a number of Home Defence squadrons in order to counter the German bombing attacks which, made by Gotha G IVs, had begun on 25 May 1917 against southeast England.

Alas, through no fault of the aircraft or their pilots but rather because of the lack of a suitable raid warning system, scarcely any success was achieved against the raiders. However the Pup was found to be admirably suitable for night flying and, beginning in December 1917, as the Germans embarked on night raiding with their bombers, they began equipping special night training Squadrons in Britain, namely Nos 187, 188 and 189.

Such were the excellent handling qualities of the Pup that it was a natural instrument for countless experiments, the majority of which were conducted with the naval aircraft. Trials with flotation bags under the lower wings led to their fitting to a number of Pups which operated over the sea; lying flat underneath the lower wings during normal flight, they would inflate if the aircraft was forced to alight on the water, thereby enabling the Pup to remain afloat for several hours.

Pups performed many of the early trials aboard ships at sea. In June 1917 Flt Cdr F J Rutland flew a Pup from a twenty-foot platform on the fo’c’sle of the light cruiser hms Yarmouth which was sailing at 20 knots into wind, an experiment that led to the fitting of similar platforms aboard hm Cruisers Caledon, Cassandra, Cordelia and Dublin. And it was Flt Sub-Lt B A Smart who won a DSO when, on 21 August that year, he took off from hms Yarmouth off the Danish coast to shoot down the Zeppelin L.23 before alighting on the sea beside another British cruiser.

The Pup also made the pioneering landings on the deck of a ship at sea. The first aircraft carrier to be equipped with a fairly large flight deck was hms Furious, whose 228-foot deck was located forward of her superstructure. Sqn Cdr E H Dunning made two successful landings on 2 August 1917 by sideslipping round the superstructure to arrive low over the deck so slowly that naval personnel could grab toggles under the wings to pull the Pup on to the deck. Tragically the Pup suffered a burst tyre on the third landing; it lurched overboard and Dunning lost his life.

Later an after-deck was added to hms Furious to enable aircraft to land more conventionally. However there was nothing to prevent aircraft from slewing sideways and damaging their undercarriage, and some Pups were fitted with skids in place of wheels, as well as rudimentary arrester hooks.

In the RFC many of the Home Defence Pups were powered by 100hp Gnome monosoupape engines, and these served to improve performance at altitude. A pilot who had already won the Military Medal while flying D.H.2s with No 29 Squadron, was flying as an instructor at Joyce Green in mid-1917 and flew a monosoupape aircraft against the raiding Gothas on several occasions. His name was Lieut James Thomas Byford McCudden. A year later, flying the S.E.5 with No 56 Squadron, he raised his victory tally to 57 enemy aircraft destroyed, and in so doing added the Victoria Cross, two DSOs and two MCs to his gallantry decorations. He is on record as having paid unqualified tribute to the little Pup, ‘which could turn twice to an Albatros’ once...’

Type: Single-engine, single-seat, single-bay biplane scout.

Manufacturers: The Sopwith Aviation Co Ltd, Kingston-upon-Thames, Surrey; William Beardmore & Co Ltd, Dalmuir, Dunbartonshire; The Standard Motor Co Ltd, Coventry; Whitehead Aircraft Ltd, Richmond, Surrey.

Powerplant: One 80hp Le Rhone; 80hp Gnome; 80hp Clerget; 100hp Gnome monosoupape engine.

Structure: Wooden box-girder fuselage with ash longerons and spruce spacers, wire-braced and fabric-covered; two-spar staggered wings with spindled spruce spars, spruce ribs and ash riblets; steel tubular wingtips and tail unit with fabric covering.

Dimensions: Span, 26ft 6in; length, 19ft 3 3/4 in; height, 9ft 5in; wing area, 254 sq ft.

Weights: (Le Rhone) Tare, 787lb; all-up, 1,225 lb. (Gnome monosoupape) Tare, 856lb; all-up, 1,297lb.

Performance: (Le Rhone) Max speed, 111.5 mph at sea level; climb to 10,000ft, 14 min; service ceiling, 17,500ft; endurance, 3 hr. (Gnome monosoupape) Max speed, 110 mph at sea level; climb to 10,000ft, 12 min 25 sec; service ceiling, 18,500ft; endurance, 17 hr.

Armament: One 0.303in Vickers machine gun with Sopwith-Kauper synchronizing gear to fire through propeller arc. Some Pups armed with eight Le Prieur rockets in addition to gun; other aircraft fitted with single Lewis gun, but not synchronized.

Prototypes: Six. No 3691 (first flown by Harry Hawker at Brooklands, probably during February 1916); Nos 9496, 9497 and 9898-9900, all built by Sopwith.

Production: Total, 1,770. (Beardmore, Nos 9901-9950 and N6430-N6459; Standard, A626-A675, A7301-A7350, B1701-B1850, B5901-B6150 and C201-C550; Whitehead, A6150-A6249, B2151-B2250, B5251-B5400, B7481-B7580, C1451-C1550, C3707-C3776 and D4011-D4210; Sopwith, N5180-N51199, N6160-N6209 and N6460-N6479)

Summary of Service: Pups served with Nos 46, 54 and 66 Squadrons, RFC, in France; Nos. 46, 61 and 112 Squadrons, RFC, Home Defence; No 66 Squadron, RFC, Italy; with CFS, Upavon, and numerous other training units. Naval Pups served with Nos 3, 4, 8, 9 and 12 (Naval) Squadrons, RNAS; Special Duty Flight; No 1 (Naval) Wing, RNAS; aboard hm Carriers Argas, Campania, Furious and Manxman', hm Light Cruisers Caledon, Cassandra, Cordelia, Dublin and Yarmouth', and hm Battle Cruiser Repulse. Also numerous training units and Stations at home and overseas.

Показать полностью

W.Green, G.Swanborough The Complete Book of Fighters

SOPWITH PUP UK

Possessing an obvious resemblance to the 1 1/2-Strutter, the Pup - again an unofficial appellation which was to become inseparable from the aircraft to which it was affectionately applied - flew in the early spring of 1916 as the Sopwith Scout. A conventional single-bay equi-span staggered biplane primarily of wooden construction with fabric skinning, the Pup had a single 0.303-in (7,7-mm) synchronised machine gun, and all six prototypes and the initial 11 Beardmore-built aircraft had the 80 hp Clerget nine-cylinder rotary engine. Subsequently, the 80 hp Le Rhone rotary was standardised. The Pup was ordered by the Admiralty from Sopwith and Beardmore, and by the War Office from Standard Motor and Whitehead Aircraft, the first production examples appearing in September 1916. Obsolescent as a frontline fighter by the late summer of 1917 - although production continued in 1918, 733 being delivered in that year to bring the grand total to 1,770 - the Pup was assigned to Home Defence units. To improve combat capability against the Gotha bombers then attacking the UK, the Pup was fitted with a 100 hp Gnome Monosoupape, the installation being characterised by a horseshoe-shaped cowling. Many RNAS Pups were armed with a 0.303-in (7,7-mm) gun on a tripod mount in front of the cockpit and some 20 were equipped to carry eight Le Prieur rockets, four each on the interplane struts. Early in 1917, the Pup came into use as a shipboard fighter and was used on the carriers Campania, Furious and Manxman. The following data relate to the standard Le Rhone 9C-powered Pup.

Max speed, 111 mph (179 km/h) at sea level.

Time to 5,000 ft (1 525 m), 5.33 min.

Endurance, 3.0 hrs.

Empty weight, 787 lb (357 kg).

Loaded weight, 1,225 lb (556 kg).

Span, 26 ft 6 in (8,08 m).

Length, 19 ft 3 3/4 in (5,89 m).

Height, 9 ft 5 in (2,87 m).

Wing area, 254 sq ft (23,60 m2).

Показать полностью

J.Bruce British Aeroplanes 1914-1918 (Putnam)

Sopwith Pup

IT has been said that the little Sopwith Scout which was to be known as the Pup was designed as a counter-weapon to the Fokker monoplane. The Fokker began its depredations over the Western Front late in the autumn of 1915: the Sopwith Scout was passed by the Sopwith experimental department on February 9th, 1916.

Possibly the desire to produce a new type urgently led the Sopwith company to embody some design features of an earlier biplane which was a known quantity, for the Pup bore a resemblance to the little SL.T.B.P. which had been built for Harry Hawker. The wings and tailplane had the raked-back tips which had first appeared on Hawker’s single-seater, and the fuselage was generally similar to that of the earlier machine. On the Pup, however, the wing structure incorporated a much wider centre-section supported on outwards-splayed struts, whereas the SL.T.B.P. had had vertical centre-section struts. There was a cut-out in the trailing edge of the Pup’s centre-section, and the pilot sat directly under that cut-out. On the later aircraft ailerons were fitted.

The origin of the name “Pup” is uncertain, but there may be some truth in the story that the delighted Service pilots who first flew it regarded it as an offspring of the 1 1/2-Strutter - in fact, as the 1 1/2-Strutter’s pup. The name was always unofficial, and for a time the authorities did all they could to prevent the use of such a flippant designation for a fighting aeroplane. The official strictures could, of course, have only one result: the name Pup became inseparable from the little Sopwith Scout.

Even if there had been an official system for the naming of aircraft at the time of the Pup’s appearance, it is doubtful whether any more appropriate name could have been found. Gentle, docile, obedient, and in all ways a delight to handle, the Pup was probably the most perfect flying machine ever made and captured the affections of all who flew it.

Like every inspired creation, it had the essential characteristic of simplicity. The fuselage had ash longerons and spruce spacers; the whole assembly was braced as a box girder with wire. Behind the fireproof bulkhead there were diagonal struts of ash, and fairings were fitted on each side of the fuselage behind the circular engine cowling. A rounded top-decking was fitted along the full length of the fuselage. Apart from having aluminium sheet behind the engine cowling and plywood about the cockpit, the fuselage was covered with fabric.

The wings had spars of spindled spruce, spruce ribs and birch riblets; steel tube was used for the wingtips and trailing edges. The ailerons were remarkably small, and hardly seemed capable of making the Pup as manoeuvrable as it was; they were hinged to the rear spars and interconnected by cables. A balance cable ran inside the upper wing, in front of the forward spar.

The tailplane was of composite construction: the rear spar was a 7/8-inch X 22-gauge steel tube, but the remainder was of wood with fabric covering. The elevator, fin and rudder were all made entirely of steel tube.

The undercarriage had two plain steel tube-vees, and had the split-axle wheel attachment which had appeared on Hawker’s single-seater and the 1 1/2-Strutter; springing was by rubber cord. The simple tailskid was mounted on an extension of the stern-post, and was also sprung by means of rubber cord.

If any proof of the Pup’s excellence were needed, it surely lay in the fact that the machine’s good performance was achieved with no greater power than that provided by the 80 h.p. Le Rhone engine. The excellent little rotary was installed on an overhung mounting, and had a circular cowling.

When the Pup was designed the Sopwith company were still Admiralty contractors; and all six prototypes were delivered to the R.N.A.S. The first was numbered 3691 and was followed by 9496, 9497 and 9898-9900. Production was undertaken by Sopwith and by the Beardmore company, and such was the oddness of the Admiralty’s system of designating aircraft types by the serial number of a typical machine that the Pup was known by the number of a Beardmore-built example: to the Admiralty it was the Sopwith Type 9901.

The standard armament of the Pup was a single Vickers gun mounted centrally on top of the fuselage and fitted with a padded windscreen at its rear end. The gun was synchronised to fire through the revolving airscrew by means of the Sopwith-Kauper mechanical synchronising gear. The pilot had no firing button on the control column; instead, he had to depress a lever which projected rearwards from the gun.

Not all of the R.N.A.S. Pups had the Vickers gun, however. Those which were intended for use from ships had a modified centre-section with a rectangular cut-out between the spars; through this cut-out passed the muzzle of a Lewis gun, which was mounted on a tripod of steel tubes immediately in front of the pilot and fired upwards, either at a shallow angle just clear of the airscrew, or nearly vertically.

Production of the Pup for the R.F.C. must have begun only a little later than the building of the R.N.A.S. machines, and was chiefly undertaken by the Standard Motor Co., Ltd., and Whitehead Aircraft, Ltd.

Production machines did not appear until September, 1916, but one of the prototypes was in France as early as May, 1916. At the end of that month it was sent to Furnes, where it was flown by Naval “A” Fighting Squadron.

The first Service unit to use the Pup in quantity was No. 1 Wing of the R.N.A.S., and one of the first enemy aircraft to fall to a Pup was the L.V.G. two-seater which was shot down near Ghistelles by Flight Sub-Lieutenant S. J. Goble on September 24th, 1916.

By late September, 1916, the resources of the Royal Flying Corps had been strained to the utmost by the demands of the Battle of the Somme, and reinforcements were required. Sir Douglas Haig reported the need in his letter to the War Office dated September 30th, 1916. His letter was discussed at a meeting of the War Cabinet held on October 17th, and it was decided to form a R.N.A.S. squadron to help the R.F.C. on the Somme. The equipment of the new unit, known as No. 8 (Naval) Squadron, was drawn from the R.N.A.S. units then at Dunkerque. Six Pups were supplied by No. 1 Wing, whilst the remainder of Naval Eight’s equipment consisted of six Nieuport Scouts and six Sopwith 1 1/2-Strutters.

The new squadron operated from the aerodrome at Vert Galand and made its first patrol on November 3rd. The Pups soon proved to be more than a match for the enemy fighters, and were obviously so much more useful for the squadron’s duties than the Nieuports and 1 1/2-Strutters that it was decided to equip Naval Eight with Pups throughout. The 1 1/2-Strutters were the first to go: by agreement between General Trenchard and Wing Captain C. L. Lambe they were replaced by Pups on November 16th, 1916, and by the end of the year the Nieuport Flight had completed its re-equipment with Pups.

Naval Eight’s Pups were not acquired by a simple act of exchange, however. Engines were scarce, and Wing Captain Lambe had to undertake to provide the necessary 80 h.p. Le Rhones before the airframes could be provided. Most of the engines he obtained from crashed Nieuports, and a few were begged from the French, but enough engines were found to equip the Pups. The engines were thoroughly overhauled at Dunkerque and were then taken across to Dover for installation in the waiting Pups.

By the end of 1916 the Pups of No. 8 (Naval) Squadron had shot down twenty enemy machines. Even Manfred von Richthofen had to admit the Pup’s superiority. Writing of his combat with one of Naval Eight’s machines on January 4th, 1917, he said:

“One of the English aeroplanes (Sopwith one-seater) attacked us and we saw immediately that the enemy aeroplane was superior to ours. Only because we were three against one, we detected the enemy’s weak points. I managed to get behind him and shot him down.”

In March, 1917, Naval Eight was re-equipped with Sopwith Triplanes, but by that time other units were flying Pups. The first R.F.C. Pup squadron, No. 54, arrived in France on December 24th, 1916. No. 3 (Naval) Squadron arrived to relieve No. 8 on February 1st, 1917, and No. 66 Squadron, R.F.C., reached France on March 6th. Only one other unit of the R.F.C. had the Pup: that was No. 46 Squadron, which was re-equipped with the type in April, 1917.

The Pup’s great test in action came during the Battle of Arras in early 1917. The measure of its quality is nowhere better expressed than in the words of Mr H. A. Jones, the official historian, in Volume III of The War in the Air:

“The critical nature of the air position was considerably relieved by the Sopwith Pup and the Sopwith Triplane. These two single-seater aeroplanes ... were as good as the best of the German fighters.”

During the period preceding Arras, the Pups of No. 3 (Naval) Squadron were involved in the fiercest of the fighting. They suffered no casualties, but inflicted such losses on the enemy that German pilots avoided combat with them.

Throughout the Battles of Arras, Messines, Ypres and Cambrai the Pup gave gallant service and accounted for many enemy aircraft. Occasionally it acted as a bomber, and the Pups of Nos. 46 and 66 Squadrons dropped 25-lb bombs on enemy aerodromes at various times.

By the autumn of 1917 the Pup no longer had the performance nor the armament to remain a fully effective fighter, yet its ability to hold its height in combat and its exemplary manoeuvrability enabled it to be used until the end of the year. No. 46 Squadron was re-equipped with Camels during November, 1917, and No. 54 was withdrawn to Bruay on 6th December to receive its Camels. No. 66 Squadron had exchanged its Pups for Camels before its transfer to the Italian front on November 17th, 1917, but one Pup went to Italy in 1918, presumably as a personal aircraft of some officer of the squadron.

In a rather forlorn attempt to augment the Pup’s armament, one or two pilots of No. 54 Squadron fitted a Lewis gun above the centre-section; this was done in October, 1917. It was soon found, however, that the weight of the gun and mounting imposed undesirable loads on the centre-section and impaired manoeuvrability. The idea was discarded.