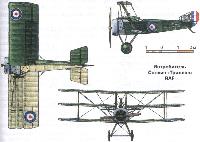

В.Кондратьев Самолеты первой мировой войны

Сопвич "Триплан" / Sopwith Triplane

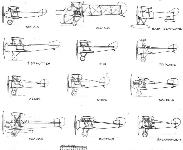

Самолет разработан инженером-конструктором фирмы "Сопвич Эвиэйшн Компани" Гербертом Смитом. Первый полет прототипа состоялся в мае 1916 года под управлением шеф-пилота фирмы "Сопвич" Гарри Хаукера. Применение трипланной схемы обусловлено стремлением повысить маневренность машины и улучшить обзор для летчика. В июне прототип прошел фронтовые испытания во Франции и заслужил высокие оценки пилотов.

Адмиралтейство и военное министерство Великобритании (War Office) выдали совместный заказ на 400 экземпляров истребителя, однако уже в конце того же года серийное производство прекратилось, так как руководство британской авиации сделало ставку на более перспективные модели. Всего успели построить около 150 экземпляров "триплана", из них 95 - на фирме "Сопвич", а остальные - на фирмах "Клэйтон энд Шаттлуорт" и "Окли энд Компани".

Самолет оснащался довольно мощным по тем временам 130-сильным ротативным мотором "Клерже" 9B и синхронным пулеметом "Виккерс". На нескольких экземплярах установили по два синхропулемета (первый подобный случай в авиации союзников).

Один экземпляр истребителя был в экспериментальном порядке оснащен двухрядным двигателем водяного охлаждения "Испано-Сюиза".

"Трипланы" начали поступать во фронтовые части западного фронта в ноябре 1916-го. К весне 1917-го они состояли на вооружении 1-го, 8-го, 9-го, 10-го, 11-го и 12-го дивизионов RNAS (1-й, 8-й и 10-й дивизионы позже были переведены в RFC).

Самолет хорошо проявил себя в воздушных боях, показав выдающиеся скорость, маневренность и скороподъемность. На тот момент "Триплан" был, несомненно, лучшим британским истребителем, хотя к середине 1917 года его стандартное вооружение считалось уже недостаточным. Он произвел такое впечатление на противника, что целый ряд немецких авиафирм срочно взялся за создание собственных истребителей трипланной схемы.

Появление весной 1917-го более совершенного, а главное - двухпулеметного "Кэмела" помешало широкому распространению трехкрылого истребителя. Летом того же года "кэмелы" начали быстро вытеснять "трипланы" из строевых частей, и к началу следующего "трипланов" на фронте уже не осталось.

В том же году четыре экземпляра "Триплана" передали для ознакомления французам, один - американцам и еще один (серийный №5486) - отправили в Россию. Этот самолет применялся на стороне красных в Гражданской войне, затем довольно долго использовался как учебное пособие в московской авиашколе, а сейчас чудом уцелевшая машина является экспонатом Монинского авиационного музея.

ЛЕТНО-ТЕХНИЧЕСКИЕ ХАРАКТЕРИСТИКИ

("Триплан" 1916г)

Размах, м 8,08

Длина, м 5,84

Высота, м 3,10

Площадь крыла, кв.м 21,45

Сухой вес, кг 499

Взлетный вес, кг 700

Двигатель: "Клерже-9b"

мощность, л. с. 130

Скорость максимальная, км/ч 182

Скорость подъема на высоту

2000 м, мин.сек 6,40

Дальность полета, км 560

Потолок, м 6250

Экипаж, чел. 1

Вооружение 1-2 пулемета

Показать полностью

А.Шепс Самолеты Первой мировой войны. Страны Антанты

Сопвич "Триплан" (Triplane) 1916 г.

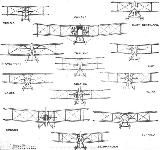

Дальнейшим развитием машин серии "Пап" были истребители Сопвич "Триплан". Главным отличием этой машины от предшественника было наличие трех крыльев, что позволило при том же размахе получить большую площадь поверхности крыльев и уменьшить хорду крыла. Уменьшая нагрузку на крыло, получаем лучшие маневренные, скоростные и взлетно-посадочные характеристики. Верхнее крыло сплошное, консоли крепились к небольшому центроплану. Среднее крыло имело разрыв в районе центроплана для лучшего обзора. Так как крыло имело меньшую хорду, устанавливались одинарные стойки крыла, но вводились дополнительные растяжки. Обычно устанавливался один синхронный пулемет 7,69-мм "Виккерс". Но на некоторых машинах устанавливалось и 2 пулемета. Конструкция фюзеляжа, оперения и шасси аналогичное самолету "Пап" с незначительными изменениями. Управление тросовое, обычное для машин того времени. Двигатель 9-цилиндровый, воздушного охлаждения, звездообразный "Клерже-9b" (130 л. с.). Всего построено только 152 машины этого типа. Несколько машин в 1917-1920 годах попали в Россию по поставкам союзников и как трофеи во время интервенции.

Опыт первых воздушных боев, проведенных "Трипланами", показал их преимущество перед современными германскими аппаратами, однако предпочтение для массового производства было отдано более простому биплану.

Показать полностью

В.Шавров История конструкций самолетов в СССР до 1938 г.

"Сопвич-триплан" - один из удачных английских истребителей, применявшихся на западном фронте в 1917-1918 гг. Двигатель - "Клерже" в 130 л. с. Применялся и в гражданской войне.

В России было несколько таких самолетов, полученных в 1917 г.

Самолет||

Год выпуска||1917

Двигатель , марка||

мощность, л. с.||130

Длина самолета, м||5,9

Размах крыла, м||8

Площадь крыла, м2||25,4

Масса пустого, кг||583

Масса топлива+ масла, кг||82

Масса полной нагрузки, кг||201

Полетная масса, кг||784

Удельная нагрузка на крыло, кг/м2||30,8

Удельная нагрузка на мощность, кг/лс||6

Весовая отдача,%||25

Скорость максимальная у земли, км/ч||185

Время набора высоты||

2000м, мин||6,5

3000м, мин||11,7

Потолок практический, м||6000

Продолжительность полета, ч.||2

Показать полностью

H.King Sopwith Aircraft 1912-1920 (Putnam)

Triplane

By the above style and title only (though with the inevitable diminutive 'Tripe' or the then-stylish "Tripehound") was known one of the daintiest and most distinctive fighters ever to leave Kingston-on-Thames. And with the Pup still close in mind the terms 'dainty' and 'distinctive' are not glibly applied. There was, indeed, a very close relationship between the two machines, though in the Triplane the first aeroplane of its form to be put to practical use a special effort was made to improve not only fighting view (which in the Pup was deficient) but manoeuvrability also for whatever its virtues in respect of handling and height-holding the Pup still invited attention to rate of turn and roll. Even so, Harry Hawker himself considered not only the Pup, but the Triplane also, rather too stable though he himself is said to have recommended for the Triplane the reduction of tailplane area that was to become one further distinction from the Pup.

Design criteria and characteristics were most concisely epitomised by Harald Penrose when he wrote: 'Superimposing the Pup fuselage drawing on that of the Triplane shows, as with the Tabloid, matched profiles, though the spacer-strut disposition varies a little, with particularly clever adaptation at the centre-section struts. The span of the Pup and the Triplane was identical at 26 ft 6 in; the effective stagger from lop leading edge to lower wing trailing edge was the same; and to align the three leading edges the wing chord of the Triplane was made 3 ft 3 in instead of 5 ft 1 1/2 in. However, the weight of the Triplane would beat least 200 lb greater than the Pup; clearly it was desirable to go for the biggest available engine to enhance performance, so a 110 hp Clerget from the 1 1/2 Strutter production line was taken. On 28 May, 1916, the Sopwith Experimental Department passed the machine for flight tests. By that time the Pup was earning tributes everywhere for its impeccable handling.'

To this appraisal the present writer would merely add a note to emphasise the Triplane's quite astounding rate of climb by virtue of a lower power-loading, which more than offset the higher wing-loading.

One manifest disadvantage inherited by the Triplane from the Pup was the fitting of a single machine-gun only, the installations being more or less identical, with the Vickers gun lying on the centre line ahead of the cockpit and having mechanical synchronising gear (Scarff-Dibovsky or Sopwith-Kauper), an ammunition supply of 500 rounds and the Sopwith padded screen. In some degree the disadvantage of low firepower was offset by the Triplane's stability, enabling it to fly hands-off for clearing gun-jams. Departures from standard armament included the fitting of twin Vickers guns in a few examples; the addition of a Lewis gun at the root of the port middle wing; and provision for elevating the Vickers gun to fire upwards at an angle of about five degrees. This last installation entailed fitting an Aldis optical sight having a special graticule, and was intended for stern or underneath attack at relatively long range.

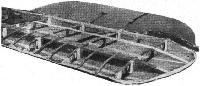

Structurally, of course, the triplane wing cellule commands our first attention and this must go beyond a remark by Lord Weir that 'Some of the aerodynamic disabilities of the triplane were overcome by the pronounced forward stagger and the use of a single strut. This single-strut system increased the difficulties of manufacture and repair, particularly as regards truing-up.'

One's first thought here is what was meant by 'the aerodynamic disabilities of the triplane' that could be overcome by merely staggering the wings, and one can only conclude that these 'disabilities' must have been attributed to interference between the juxtaposed wings-though the gap was substantial and the chord quite narrow. Lord Weir's allusion to 'forward stagger' may conceivably have been deliberate, for as we shall later see, the degree of stagger in the later Snark and Cobham triplanes was sharply unequal-conveying almost an impression of backward stagger from some aspects - while, more pointedly, some Sopwith biplanes (the 'fabric' Snail as well as the Dolphin) had actual negative stagger.

As for difficulties of manufacture, repair and rigging, the last of these was, seemingly at least, simple, the cellule being braced much as a biplane structure, though with upper and lower drag and anti-drag wires. Should the terms 'drag' and 'anti-drag' seem too extremely archaic in respect of such external as distinct from internal-wires, it may be remarked that, well into the 1930s, riggers of RAF Siskins a type officially declared to have 'unusual' wing-bracing were advised: 'The drag and anti-drag bracing wires are "threaded" through the plane framework from their anchorages

Admittedly, there were six ailerons on the Triplane instead of four as on the Sopwith biplane fighters; but the instructions for 'truing-up the main planes' seemed simple and explicit enough-even in this lavishly 'capitalised' verbatim rendering:

'Adjust by Landing Wires, and check by Abney Level and Straightedge, or Dihedral Board and Spirit Level, along the Front Spars of the Upper Main Planes.

'The Stagger from Upper Main Plane to Lower Main Plane is 36", being 18" between Upper and Intermediate and Intermediate and Lower Main Planes respectively.

‘This should be correct at the Centre Section. To ensure that it is constant throughout, place straightedges across the Leading Edges of the Main Planes. Adjust Drag and Anti-Drag Wires until any two of these straightedges are in line.

'Check for Main Planes being square with Machine by taking measurements from Top and Bottom Sockets of Outer Interplane Struts to Rudderpost and Front Drag Wiring Plates. Corresponding measurements should be the same on both sides.

‘The Incidence is 2 for all Main Planes. Check by Abney Level and Straightedge, placing the latter along the chord of a rib.

‘This can only be adjusted if the fittings on Interplane Struts have not been drilled.

'It is important throughout the process of truing the Main Planes to check the Dihedral, Stagger and Incidence to ensure that adjustments for one do not throw the others out.'

These verbatim instructions notwithstanding, it must be acknowledged that there were separate instructions for 'truing-up the centre section’, and that Lord Weir's remark may well have had more substance than suggested.

Oliver Stewart recalled that the Triplane was 'reported to be subject to the same trouble as the Nieuport and to have a habit of twisting one of its planes about the front spar so that control and stability were lost.’ He quickly added, however, that "in fact none of these faults was demonstrated to be inherent in the aeroplane, and as pilots got to know it better they got to like it better until, when it was superseded, it was allowed to go with regret."

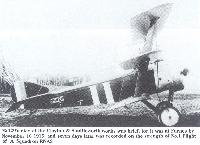

In outlining the Triplane's technical development and operational employment - which were very closely linked by the familiar tale of the "prototype N500" being sent into action a few minutes only after its arrival in France (mid-June 1916) one would first remark that although a photograph now reproduced supposedly shows "N500" under construction, the number prominently placarded on the port rear landing-gear strut is, in fact, "490". Interesting though this observation may be, its significance may be scant, for the airframe depicted appears to match the line 'taxying-at-Brooklands' study in all discernible respects; and though the transparent panelling in the top centre-section may be absent in the view taken before completion, also absent and indubitably in both views is the Vickers gun. It is worth noting, nevertheless, that the figures '490' formed no sequence in Admiralty Contract No. C.P. 117520/16. ascribed to the first Triplane order, though they did appear as three digits in N5490, one of the early Sopwith-built production machines.

In both the pictures just mentioned the engine is apparently a 110 hp Clerget (makers' suffix 9Z), and the tailplane again quite properly, to accord with characteristics usually ascribed to the first, or 'prototype' Triplane appears to be adjustable. This adjustment, it may here be mentioned, was effected (on production Triplanes at least) by the pilot turning a wheel fixed to the starboard centre-section strut where that strut passed through the cockpit. Externally, at higher level, this same strut served to carry a propeller-driven air pump for petrol delivery.

When the first Triplane joined the first Pup at Funics (base of 'A' Squadron, RNAS) in mid-1916 it amazed and delighted pilots, especially by its proven ability to reach 12.000 ft in 13 min; and, like the Pup the type was ordered for the RFC as well as the RNAS, the Navy getting the first machines built by Sopwith themselves, and the War Office depending for its initial supplies on Clayton and Shuttleworth Ltd. of Lincoln. As things turned out, however, the Triplane was never used as standard operational equipment by the RFC, the machines originally intended for that Service being exchanged for Spads.

Even the excellent rate of climb just noted was surpassed by a slightly later Triplane - apparently the second example, N504 - which, by September 1916 was flying with a 130 hp Clerget engine (Type 9B) and averaged a climb-rate of 1,000 ft/min up to a level of 13,000 ft; it may indeed have climbed to 22,000 ft in September 1916 - an achievement which, if true, would have been the more remarkable because in that same month Sqn Cdr Harry Busteed recorded its sea-level speed as 116 mph.

Subsequent re-engining was possibly conlined to the testing of a 110 hp Le Rhone installation. For the greater part Triplanes in service had the 130 hp Clerget, rather than the alternative 110 hp unit of the same make, occasionally with a small pointed spinner on the propeller, as was sometimes the case with Camels; but probably the most interesting experimental development concerned not the power plant but the airframe. This involved the testing, in December 1916, of N5423 (Sopwith-built) with wings increased in chord by three inches - that is, to 3 ft 6 in. Clearly, an increase in chord may well have been associated with a change in section; but although there is no confirmation that this was in fact the case, it is certain that official laboratory studies were made of triplane wings for which the R.A.F.15 section was substituted for the R.A.F.6. Interestingly enough, there were laboratory tests also of model triplane wings having a gap/chord ratio of 1 (almost exactly that of the standard Sopwith Triplane, which had a gap of 3 ft and a chord of 3 ft 3 in) - and with zero stagger, with +30 deg stagger, and with -30 deg stagger.

Although some aspects of the Sopwith Triplane's performance were apparently improved with the long-chord wings, these wings were never standardised; nor was wing-bracing appreciably interfered with until the Triplane's active-service life was over though the type was still a fighter classic, even, for instance, with the School of Aerial Fighting at Marske, in Yorkshire. One RAF Technical Order of 1918 required a compression strut to be fitted spanwise above the externally mounted Vickers gun.

In May 1917 N5486 left the RNAS Depot at White City, London, for White Russia, where it was fitted with skis. Jack Alcock's 'Sopwith Mouse' (so-called) embodied some Triplane components and has a note to itself under 'Apocrypha'.

Although Harald Penrose firmly ascribes to Harry Hawker the recommendation that the Triplane's tailplane should be reduced in area (the most important modification made to improve this fighter's combat performance notably by increasing the rate of turn) the alteration clearly stemmed from operational experience, for it dated from February 1917. The new horizontal surfaces (the elevator as well as the tailplane being involved) spanned only 8 ft instead of about 10 ft, and their area was thus reduced by more than 10 sq ft. Because the leading edge was now shorter than the trailing edge, the familiar inwardly-raked tips which had been so characteristic of the Pup were now reversed in form, and various changes in handling were attributed to this innovation by different pilots.

Short but lustrous was the Triplane's operational career after N500 was sent off on an interception within its first quarter-hour at Furnes in June 1916, though something of an interregnum was implicit in the fact that production Triplanes did not enter service until February 1917. The total number built, in fact, was apparently no more than 150, and from Oakley Ltd. of Ilford, Essex, came only three of their order for twenty-two. Thus in March 1917 the busy-minded and busy-tongued Mr Noel Pemberton Billing asked the Under-Secretary of State for War if he would give the date 'on which the first Sopwith triplane scout was offered to the authorities; the date on which the first order was placed for the same; what proportion of the order has been delivered; and what proportion is now on active service.’ As may be imagined, 'P.B.' was told that it would not be in the public interest to give the particulars asked for and seemingly some mystery remains to this day concerning a substantial reduction in Triplane orders, though the coming of the Camel may have had some influence here. Oakley, moreover, had never built aircraft before, and though their meagre contribution did not begin until the autumn of 1917, they had been asked to fit Camel-style armament (twin Vickers guns).

None of which considerations detracts in any way from an operational career which enabled H. A. Jones to record in The War in the Air that 'The sight of a Sopwith Triplane formation, in particular, induced the enemy pilots to dive out of range.’ And the Triplane having been, as already shown, very much an RNAS fighter, we take from British Naval Aircraft since 1912 (Owen Thetford, Putnam) this fittingly brief summation: Production Triplanes entered service with No. 1 and 8 (Naval) Squadrons in February 1917 and with No.10 (Naval) Squadron in May. Some remarkable engagements were fought by such redoubtable Triplane pilots as Sqn Cdr C. D. Booker, nsc, and F/Sub-Lt R. A. Little, of 'Naval Eight’ and FSub-Lt Raymond Collishaw of 'Naval Ten'. The Triplanes of Collishaw's B' Flight (named Black Death, Black Maria, Black Roger, Black Prince and Black Sheep) became the terror of the enemy: between May and July 1917 they destroyed 87 enemy aircraft. Collishaw personally accounted for 16 in 27 days and shot down the German ace Allmenroder on 27 June ... The Triplane's career was glorious but brief. It remained in action for only seven months: in November 1917 the Camel had supplanted it in squadrons.'

To the French Government went Triplanes N5385 and N5388, and, as already noted, N5486 was despatched to Russia. N5458 (after serving its time at the Front) was exhibited in the USA. The Germans and Austrians were clearly influenced by the design, which underwent close scrutiny at Adlershof (for several examples were captured and tested); but one clear advantage possessed by the hardly less famous Fokker Dr. I was the fitting of twin belt-fed guns as standard equipment. That Sopwith Triplanes N533 N538 are known to have been similarly armed (with two Vickers guns) and that this same armament was intended for the Oakley-built machines was small comfort, though obviously an increased warload meant a decreased rate of climb. And rate of climb, perhaps, was the real trump card in the Triplane's symbolic deck of three.

Triplane production was apparently as follows:

Sopwith N500; N504; N524: N5420-N5494; N6290-N6309

Clayton & Shuttleworth N533-N538; N5350-N5389

Oakley N5910-N5912 (N5913- N5934 were not completed).

Triplane (130 hp Clerget)

Span 26 ft 6 in (8.1 m); length 19ft 10in(6m); height 10 ft 6 in (3.2 m); wing area 231 sq ft (21.5 sq m). Empty weight 993 lb (450 kg): maximum weight 1,415 lb (642 kg). Maximum speed at 6,500 ft (1,980 m) 116 mph (187 km/h): maximum speed at 10,000 ft (3,050 m) 114mph (183 km/h); maximum speed at 15,000 ft (4,570 m) 105 mph (169 km/h): climb to 6.500 ft (1,980 m) 6.3 min; climb to 10,000 ft (3,050 m) 10.6 min: climb to 15,000 ft (4,570 m) 19 min; service ceiling 20,500 ft (6,250 m); endurance 2 hr 45 min.

Показать полностью

P.Lewis The British Fighter since 1912 (Putnam)

Despite its many advanced features, the Night Hawk remained a single prototype but, during the same period, the Sopwith Company was engaged on a comparably unusual design which was destined for fame and success. Supermarine’s quadruplane was unable to make the grade but the Sopwith Triplane’s attributes were such that it soon established itself favourably in service.

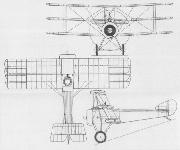

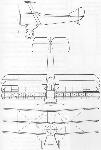

Although it bore itself on three sharply-staggered, narrow-chord wings, the Triplane prototype N.500 when it materialized at the end of May, 1916, was an eminently neat, practical design. Single interplane and centre-section struts braced the single-bay layout which was mated to a fuselage, tail unit and undercarriage close in appearance to those of the Pup. The power of the 110 h.p. Clerget engine, coupled with the small span of 26 ft. 6 in., endowed the Triplane with excellent manoeuvrability, climb and general all-round performance. Standard armament consisted of a single synchronized Vickers gun on the front decking but six were produced carrying a pair of Vickers in the same location.

Both the Admiralty and the War Office ordered the Triplane in substantial numbers but, as a result of inter-Service exchanges of aircraft in an endeavour to redress the position on the Western Front, the Triplane was operated only by the R.N.A.S. squadrons, in whose capable and enthusiastic hands it soon struck fear into the hearts of the German crews once deliveries started at the end of 1916.

The substitution of the 130 h.p. Clerget brought a corresponding benefit to the performance and the Triplane soared to its greatest heights of success with its exploits in the all-Canadian “B” Flight of No. 10 (Naval) Squadron under Flt. Sub-Lt. Raymond Collishaw. The Sopwith Triplane vindicated gloriously the faith which its designers had placed in the radical concept which it represented for a service aeroplane.

Показать полностью

F.Mason The British Fighter since 1912 (Putnam)

Sopwith Triplane (Clerget)

The Pup had not even reached the RNAS or RFC squadrons when the Sopwith Triplane made its first flight in the hands of Harry Hawker at the beginning of June 1916. That the Pup’s design represented the basis of the Triplane almost goes without saying, yet there were two intermediate stages in the process of thought. In the early spring of that year Herbert Smith had started the design of a somewhat grotesque-looking triplane escort fighter with very high aspect ratio wings, the top wing supporting a nacelle in which the gunner’s cockpit was situated; the aircraft was to be powered by a 250hp Rolls-Royce Mk I engine (see Sopwith L.R.T.Tr.). Smith’s next design was a triplane fighter derived from the 1 1/2-Strutter, this aircraft being scheduled for the 150hp water-cooled Hispano-Suiza engine. Neither of these engines was yet readily available and so the airframes were held temporarily in abeyance.

Smith now turned to the Pup, seeing in the application of triplane wings, possessing the same, or smaller chord than those of the L.R.T.Tr., considerable potential for further improvement in performance and handling. The fuselage aft of the cockpit remained almost identical to that of the Pup, though stressed for a larger engine, but the tail surfaces were later reduced in area, the tip rake of the tailplane and elevators being reversed.

The Triplane wings, however, were radical and ingenious. By limiting the chord to no more than 3ft 3in, compared to the Pup’s 5ft 3in, the wing area was in fact reduced from 254 to 231 sq ft - with exactly the same span; at the same time, with ailerons on all six wings, their total area was increased from 22 to 34 sq ft, thereby retaining the crisp handling with no extra stick load. The pilot’s field of view was improved by the reduced wing chord and by the location of the centre wing in line chordwise with the pilot’s eye level. The I-type interplane and cabane struts were the subject of Patent No 127,858, held by Fred Sigrist, and were rigged to give a total stagger of 36 inches between top and bottom wings, compared with 18 inches between the Pup’s two wings. This arrangement of struts permitted fewer bracing wires to be used, with only a single landing wire and a doubled flying wire necessary on each side. Power for the Triplane was provided initially by the 110hp Clerget engine, although the 130hp version was introduced into at least one production batch before the end of 1916. Most aircraft also retained the single synchronized Vickers gun of the Pup.

The prototype Triplane, N500, was sent to France in June for operational trials with Naval ‘A’ Fighting Squadron at Furnes (and was ordered off against a suspected enemy aircraft within fifteen minutes of refuelling). This aircraft was representative of the proposed initial production version, but the second prototype, N504, was powered by the 130hp Clerget and carried twin Vickers guns.

The first production order was placed by the Admiralty in August, followed by orders from the War Office for 100 aircraft to be built by Sop with, and 166 by Clayton & Shuttleworth of Lincoln. In due course, however, owing to the critical shortage of RFC fighters in France, it was agreed that in return for Spad S.7s which were held by the Admiralty, the War Office would relinquish their orders for Triplanes in favour of the RNAS. In the event none of the original 266 RFC Triplanes were built. Instead, the Admiralty placed orders totalling 145 aircraft with Sopwith and Clayton & Shuttleworth, as well as 25 from Oakleys of Ilford (of which only three were completed).

Once again the artificial bureaucracy that concealed petty jealousies between the Admiralty and War Office robbed the fighting men of the weapons that would have stood them in good stead when the air war took such a disastrous turn in the spring of 1917.

As it was, the RNAS put their relatively small number of Triplanes to excellent use. Production had got underway at Sopwith and Clayton in the late autumn of 1916, and the first deliveries were being made to the RNAS at the turn of the year. By the end of February No 1 (Naval) Squadron at Chipilly, under the command of Sqn Cdr F K Haskins (later Air Cdre, dsc, raf) had received seventeen Triplanes; then it was the turn of ‘Naval Eight’ at Auchel, who gave up their Pups in exchange for Triplanes in March, and No 10 (Naval) Squadron in May.

It was a Canadian pilot on Naval Ten who was to become the greatest fighting exponent of the Triplane in the person of Flight Sub-Lt Raymond Collishaw (later Air Vice-Marshal, cb, dso*, obe, dsc, dfc, raf). Given command of ‘B’ Flight, Collishaw generated an extraordinary esprit by his example, and his pilots - all Canadians and superb pilots in their own right - had their Triplanes painted black overall and given names such as Black Prince, Black Death, Black Sheep and Black Maria (Collishaw’s aircraft), and so on. In air combats during June, Collishaw alone shot down no fewer than sixteen German aircraft, of which thirteen were single-seat fighters; apart from Collishaw himself, four other pilots of ‘Black Flight’ between them destroyed 54 German aircraft. Their flight commander would, by the end of the War become the third highest-scoring British Commonwealth fighter pilot, with a score of 60 victories; he also served with great distinction in the Second World War.

As already stated, a few Triplanes were fitted with the 130hp Clerget, an additional power that gave the little fighter a top speed of 117 mph, and six of the aircraft built by Clayton & Shuttleworth (N533-N538) were armed with twin Vickers guns. A total of six Triplanes was loaned to France, but these were returned to the RNAS when the shortage of fighters became acute early in 1917; even the original prototype was pressed into service with Naval One, while the second served with Naval Eight.

The Triplane’s swansong was during the third Battle of Ypres in August 1917. By the end of the month Naval Ten was being re-equipped with the Sopwith Camel, and by Christmas the Triplane had been withdrawn from operational service.

Type: Single-engine, single-seat, single-bay triplane scout.

Manufacturers: The Sopwith Aviation Co Ltd, Kingston-upon-Thames, Surrey; Clayton & Shuttleworth Ltd, Lincoln; Oakley Ltd, Ilford, Essex

Powerplant: One 110hp or 130hp Clerget rotary engine driving two-blade propeller.

Structure: All-wooden wire-braced box-girder fuselage with fabric covering; triplane, single-bay, two-spar wings with single interplane and cabane I-struts.

Dimensions: Span, 26ft 6in; length, 18ft 10in; height, 10ft 6in; wing area, 231 sq ft.

Weights: (130hp Clerget) Tare, 1,101lb; all-up, 1,541lb.

Performance: (130hp Clerget) Max speed, 117 mph at sea level, 104 mph at 13,000ft; climb to 10,000ft, 11 min 50 sec; service ceiling, 20,500ft; endurance, 2 3/4 hr.

Armament: Either one or two synchronized 0.303in Vickers machine guns on nose top decking with Sopwith-Kauper interrupter gear.

Prototypes: Two, N500 and N504 (N500 first flown by Harry Hawker at Brooklands early in June 1916); both built by Sopwith.

Production: Total of 145 (95 by Sopwith: N5420-N5494 and N6290-N6309; 47 by Clayton & Shuttleworth: N524, N533-N538 and N5350-N5389; three by Oakley, N5910-N5912).

Summary of Service: Triplanes served with Nos 1, 8, 9, 10 and 12 (Naval) Squadrons, RNAS, on the Western Front; also with ‘E’ Squadron, RNAS, in Macedonia; with No 2 (Naval) Wing, RNAS, at Mudros in the Aegean; and at RNAS Manston and Port Victoria. A small number was loaned or supplied to France, the USA and Russia.

Показать полностью

W.Green, G.Swanborough The Complete Book of Fighters

SOPWITH TRIPLANE UK

Possessing a fuselage fundamentally similar to that of the Pup, although the disposition of spacers, formers and stringers differed, Sopwith’s next single-seat fighter - designed, like the Pup, by Herbert Smith - initiated a vogue: that of the fighting triplane. The first prototype of what was to be referred to simply as the Triplane was completed in May 1916, its radical wing arrangement of triple narrow-chord mainplanes, with ailerons on all three wings and single broad-chord interplane and centre section struts, resulted in exemplary manoeuvrability and, for its day, a phenomenal climb rate. A measure of the success of the Sopwith Triplane after making its combat debut with the RNAS was provided by the extraordinary variety of single-seat fighters of similar configuration hurriedly developed by German and Austro-Hungarian companies. Initially powered by the 110 hp Clerget 9Z nine-cylinder rotary, but more usually being fitted with the 130 hp Clerget 9B, the Triplane began to appear in production form late in 1916, joining combat in the following February. Armament normally comprised one synchronised 0.303-in (7,7-mm) gun, but a few were fitted with twin weapons of this calibre. At least one aircraft was tested with a 110 hp Le Rhone engine. Although the Tri¬plane was ordered for both the RNAS and RFC, it was, in fact, used operationally by the former service only, an agreement having been reached in February 1917 under which the RNAS exchanged all its SPAD S.VIIs for all the Triplanes then on order for the RFC. As a result, contracts were reduced and only some 150 were completed, the Triplane’s operational career being brief, and its replacement by the Camel in Naval squadrons commencing as early as July 1917. The following data relate to the 130 hp Clerget-engined Triplane.

Max speed, 116 mph (187 km/h) at 6,000 ft (1 830 m).

Time to 6,500 ft (1 980 m), 6.33 min.

Endurance, 2.75 hrs.

Empty weight, 993 lb (450 kg).

Loaded weight, 1,415 lb (642 kg).

Span, 26 ft 6 in (8,08 m).

Length, 19 ft 6 in (5,94 m).

Height, 10 ft 6 in (3,20 m).

Wing area, 231 sq ft (21,46 m2).

Показать полностью

J.Bruce British Aeroplanes 1914-1918 (Putnam)

Sopwith Triplane

THE Sopwith Pup was followed by the Triplane, which was passed by the Sopwith experimental department on May 28th, 1916. Looking back, it is hard to realise the revolutionary nature of the Triplane at the time it appeared. Nothing quite like it had ever been built for military purposes, and the best measure of its success is provided by the profusion of German and Austrian single-seat fighter triplanes which appeared after the impact made by the Sopwith Triplane had earned it a eulogy from General von Hoppner, commander of the German air service.

An astonishing variety of triplanes were built by the A.E.G., Albatros, Austrian Aviatik, Brandenburg, D.F.W., Euler, Fokker, Lohner, Oeffag, Pfalz, Roland, Sablatnig, Schutte-Lanz and W.K.F. concerns; and their very numbers hint at an almost frantic search for the elusive quality, presumably thought to be inherent in the triplane configuration, which made the Sopwith Triplane the fine fighting aeroplane that it was.

It has been said that Anthony Fokker was so anxious to produce an aircraft which would be an adequate reply to the new Sopwith fighter that he resorted to subterfuge to obtain an example of the Triplane. He contrived to arrange for the delivery to his works of the remains of a Sopwith Triplane which had been shot down, despite the fact that the aircraft should have gone to the German experimental field at Adlershof. However, the Fokker Dr. I triplane which was ultimately designed by Reinhold Platz, Fokker’s chief designer, was a very different aeroplane from the Sopwith Triplane.

In the Sopwith type, the triplane layout was adopted in order to give the pilot the widest possible field of vision, and to ensure manoeuvrability. The central wing was level with the pilot’s eyes and obscured very little of his view, and the narrow chord of all the mainplanes ensured that the top and bottom wings interfered less with his outlook than the wings of a biplane. The narrow chord aided manoeuvrability, for the shift of the centre of pressure with changes of incidence was comparatively small; this permitted the use of a short fuselage. At the same time, the distribution of the wing area over three mainplanes kept the span short and conferred a high rate of roll.

The handling qualities of the Triplane were excellent. It is now regarded as only slightly less manoeuvrable than the Pup, but many pilots preferred it to the little biplane.

The fuselage and tail-unit were generally similar to those of the Pup in both appearance and construction, but the structure was stressed to take the 110 h.p. Clerget engine. The wing structure was of considerable interest. Each wing had two main spars, 15 inches apart; those of the upper mainplane were solid, but in the middle and bottom wings they were spindled out between the compression struts. The wings were internally cross-braced with wire.

The most interesting structural feature of the Sopwith Triplane was its interplane bracing. On each side there was only a single broad interplane strut which was continuous from the top wing to the bottom, and passed through a shaped slot in the appropriate compression strut of the middle wing. The centresection struts were similarly continuous from the centre-section to the bottom longerons of the fuselage; the middle wings were secured by means of long pins to special aerofoil-shaped stubs on the centre-section struts. Bracing wires were few: a single landing wire and double flying-wires were fitted on each side, and there were additional drag-wires on the middle wing. Ailerons were fitted to all three mainplanes, and were hinged to the rear spars. The shape of the wing-tips made them similar to those of the Pup, and a similar tailplane was used. Late production Triplanes had a smaller tailplane in which the leading edge was shorter than the trailing edge.

The armament consisted of a single fixed Vickers gun mounted centrally on top of the fuselage and synchronised to fire forward through the airscrew.

The first prototype Sopwith Triplane, N.500, went to France in mid-June, 1916, to undergo Service trials with Naval “A” Fighting Squadron at Furnes. The Triplane was an instant success, and no time was lost in testing it in action, for it was sent up on an interception within a quarter of an hour of its arrival at Furnes.

The type was ordered by the Admiralty for the R.N.A.S., and the War Office followed suit by ordering 266 machines for the R.F.C. As with the Pup, Sopwiths were to build the R.N.A.S. Triplanes, whilst other contractors undertook production of the type for the R.F.C.

After the Battle of the Somme, air fighting increased in intensity, and the balance was not redressed by the transfer of Sopwith 1 1/2-Strutters from the R.N.A.S. to the R.F.C., nor by the loan of R.N.A.S. squadrons to the R.F.C. On November 20th, 1916, Sir Douglas Haig wrote to the War Office and asked for twenty more fighting squadrons. Major-General Trenchard amplified this request at the meeting of the Air Board held on December 11th and, so critical was the situation in France, asked for everything the R.N.A.S. could lend to be handed over to the R.F.C. His specific immediate demands were for four complete R.N.A.S. squadrons, one hundred Rolls-Royce and fifty Hispano-Suiza engines.

The Admiralty complied with as much of this demand as they reasonably could, but suggested that, instead of the fifty Hispano-Suiza engines, they should transfer to the R.F.C. sixty complete Spad S.7s out of their current contract for 120. This offer was accepted with alacrity. In February, 1917, a further agreement was made, under which the R.N.A.S. exchanged all its Spads for all the Sopwith Triplanes then on order for the R.F.C.

Thus it was that the Sopwith Triplane was used operationally by the R.N.A.S. only. In point of fact, all the 266 machines which had been ordered for the R.F.C. were not delivered: it is known that the Clayton and Shuttleworth contract was reduced by 120, and there may have been other reductions.

Deliveries of production Triplanes to the R.N.A.S. had begun late in 1916, and by mid-February, 1917, No. 1 (Naval) Squadron had received sixteen machines. The unit was one of the four R.N.A.S. squadrons which were attached to the R.F.C. in response to Major-General Trenchard’s request, and on February 15th, 1917, it moved from Furnes to Chipilly, where it was attached to the 14th (Army) Wing.

For several weeks the squadron practised formation flying and gunnery, and made its first offensive patrol in early April, 1917. The Battle of Arras began on the 9 th of that month, and aerial fighting reached a pitch which had never previously been experienced. Between April 22nd and May 5th, 1917, the Triplanes of Naval One flew ninety-five offensive patrols, engaged 175 enemy aircraft, destroyed four of them and drove down twelve out of control.

On April 22nd, 1917, two of No.1 (Naval) Squadron’s Triplanes, flown by Flight Commander R. S. Dallas and Flight Sub-Lieutenant T. G. Culling, met an enemy formation of fourteen two-seaters and single-seat fighters. The Germans were flying towards the lines at 16,000 feet. The Triplanes attacked at once, broke up the enemy formation, shot three of them down, and harried the remainder for 45 minutes until the Germans retreated eastward.

By April, 1917, No. 8 (Naval) Squadron also had received Sopwith Triplanes as replacements for its Pups, and in the hands of such pilots as Flight Commander S. J. Goble, D.S.O., D.S.C., Squadron Commander C. Draper, D.S.C., Flight Commander C. D. Booker, D.S.C., Flight Commander R. A. Little and their squadron-mates, the Triplane acquitted itself gloriously.

It was of this period that H. A. Jones wrote in The War in the Air: “The sight of a Sopwith Triplane formation, in particular, induced the enemy pilots to dive out of range.”

The performance of the Triplane had been improved by the installation of the more powerful 130 h.p. Clerget engine. Standard armament continued to be the single Vickers gun, but a small batch of six machines armed with twin Vickers were built by Clayton & Shuttleworth.

After Arras, it was decided to transfer the main Allied effort to the British front in Flanders, and preparations began for the action which became known as the Battle of Messines. On May 15th, 1917, the Eleventh Army Wing was reinforced by the arrival from Dunkerque of No. 10 (Naval) Squadron, equipped with fifteen Sopwith Triplanes. On June 1st, No.1 (Naval) Squadron was transferred from the Third Army.

On June 6th, thirteen of Naval Ten’s Triplanes fought fifteen enemy aeroplanes and shot down five without loss to themselves. Two of the five were Albatros scouts which fell in flames under the fire of Flight Sub-Lieutenant Raymond Collishaw.

Collishaw was probably the best-known exponent of the Sopwith Triplane’s superb fighting qualities. A Canadian, he was given command of “B” Flight of No. io (Naval) Squadron on April ist, 1917. This was the famous “Black Flight”, as redoubtable a fighting unit as took the air during the war: between May and July, 1917, it accounted for no fewer than eighty-seven enemy aircraft. All the pilots were Canadians; the original members were Flight Sub-Lieutenant E. V. Reid, Flight Sub-Lieutenant J. E. Sharman, Flight Sub-Lieutenant G. E. Nash, and Flight Sub-Lieutenant W. M. Alexander. The Triplanes of the Black Flight were named Black Death, Black Maria, Black Roger, Black Prince and Black Sheep.

In a combat on June 26th, 1917, Nash was wounded and forced down behind the enemy lines by Leutnant Allmenroder, a German pilot with thirty victories to his credit. Next day Collishaw avenged the loss of his friend: in a fight which began near Courtrai he shot down and killed Allmenroder, whose green-tailed Albatros crashed on the outskirts of Lille.

In twenty-seven days during June, 1917, Collishaw shot down sixteen enemy machines, of which all save three were Albatros and Halberstadt single-seat fighters.

At the end of August, 1917, No. 10 (Naval) Squadron began to re-equip with Sopwith Camels. Three of its Triplanes were then transferred to No. 1 (Naval) Squadron, which in turn gave up its beloved Triplanes on its withdrawal on November 2nd, 1917. The first Triplane squadrons to begin re-equipment with Camels were No. 8 (Naval), which had received a few Camels by the end of July, 1917, and No. 9 (Naval), which exchanged its Triplanes and Pups for Camels between mid-July and August 4th.

The Battles of Ypres were therefore the last actions over which Sopwith Triplanes flew. They fought with distinction until their final demise.

One Sopwith Triplane, N.5431, was used in Macedonia. It was on the strength of No. 2 Wing R.N.A.S., and in March, 1917, it was allocated to the new R.N.A.S. unit known as “E” Squadron, which later combined with a Royal Flying Corps detachment to form the Composite Fighting Squadron, based at Hadzi Junas as a countermeasure to the German bomber squadron then operating from Hudova. However, N.5431 never reached Hadzi Junas. It flew first to Stavros; and, in company with four 1 1/2- Strutters, set out for Salonika on March 26th, 1917. Its pilot was Flight Lieutenant John Alcock. When landing at Salonika, Alcock made one of the few errors of judgment in his distinguished flying career: he overshot the small aerodrome and wrecked the Triplane. The wreckage was taken back to Mudros and rebuilt: it was still flying from Mudros at the end of September, 1917. On the 30th of that month it was flown by Lieutenant H. T. Mellings when he shot down an enemy single-seat fighter seaplane.

By the end of 1917 the Triplane was no longer a front-line aircraft. Its replacement by the Camel was viewed with mixed feelings by some of the units that had flown it, for it had proved to be a formidable fighter. It combined the manoeuvrability of the Pup with the better performance bestowed by the more powerful engine, yet despite its distinguished record it has always been neglected by historians.

SPECIFICATION

Manufacturers: The Sopwith Aviation Company, Ltd., Canbury Park Road, Kingston-on-Thames.

Other Contractors: Clayton & Shuttleworth, Ltd., Lincoln. Oakley, Ltd., Ilford.

Power: 110 h.p. Clerget; 130 h.p. Clerget.

Dimensions: Span: 26 ft 6 in. Length: 18 ft 10 in. Height: 10 ft 6 in. Chord: 3 ft 3 in. Gap: 3 ft each. Stagger: 1 ft 6 in. Dihedral: 2° 30'. Incidence: 2°. Span of tail: originally 10 ft 1 in., later 8 ft. Wheel track: 5 ft 6 in. Airscrew diameter: 8 ft 11-9 in.

Areas: Wings: top 84 sq ft, middle 72 sq ft, bottom 75 sq ft; total 231 sq ft. Ailerons: each 5-66 sq ft, total 34 sq ft. Tailplane: 14 sq ft. Elevators: 9-6 sq ft. Fin: 3-5 sq ft. Rudder: 4-5 sq ft.

Weights and Performance: Trials conducted at C.F.S.; speed trial on December 9th, 1916, climbing trial on December 7th, 1916. Weights (with 130 h.p. engine): Empty: 1,101 lb. Military load: 80 lb. Pilot: 180 lb. Fuel and oil: 180 lb. Loaded: 1,541 lb. Performance (with 130 h.p. engine): Maximum speed at 5,000 ft: 117 m.p.h.; at 7,000 ft: 112 m.p.h.; at 9,000 ft: 109 m.p.h.; at 11,000 ft: 107 m.p.h.; at 13,000 ft: 104 m.p.h.; at 15,000 ft: 98 m.p.h. Climb to 1,000 ft: 50 sec; to 2,000 ft: 1 min 45 sec; to 3,000 ft: 2 min. 30 sec; to 4,000 ft: 3 min 25 sec; to 5,000 ft: 4 min 35 sec; to 6,000 ft: 5 min 50 sec; to 7,000 ft: 7 min 15 sec; to 8,000 ft: 8 min 40 sec; to 9,000 ft: 10 min 15 sec; to 10,000 ft: 11 min 50 sec; to 11,000 ft: 13 min 35 sec; to 12,000 ft: 15 min 20 sec; to 13,000 ft: 17 min 30 sec; to 14,000 ft: 19 min 50 sec; to 15,000 ft: 22 min 20 sec; to 16,000 ft: 25 min; to 16,400 ft: 26 min 30 sec. Service ceiling: 20,500 ft. Endurance 2 3/4 hours.

Tankage: Petrol: 20 gallons. Oil: 4 gallons.

Armament: One fixed, synchronised Vickers machine-gun mounted centrally on top of the fuselage, firing forward. Several Triplanes had an installation of twin synchronised Vickers guns.

Service Use: Western Front: Naval “A” Fighting Squadron; R.N.A.S. Squadrons Nos. 1, 8, 9, 10 and 12. Macedonia: “E” Squadron, R.N.A.S. Aegean: No. 2 Wing, R.N.A.S., Mudros. Training: R.N.A.S. War School, Manston; R.N.A.S. Port Victoria. Examples of the type went to France, Russia and the U.S.A.

Serial Numbers: The batches A.9000-A.9099 and A.9813-A.9978 were allotted for Triplanes ordered for the R.F.C., but were cancelled. The latter batch was ordered from Clayton & Shuttleworth. N.500: built by Sopwith under Contract No. C.P.117520/16. N.504: built by Sopwith under Contract No. 124352/16. N.524, N.533-N.538: built by Clayton & Shuttleworth under Contract No. A.S.14457. N.541-N.543. N.5350-N.5389: built by Clayton & Shuttleworth. N.5420-N.5494: built by Sopwith. N.5910-N.5934: ordered from Oakley (N.5913-N.5934 were not completed). N.6290-N.6309: built by Sopwith.

Notes on Individual Machines: Used by No. 1 (Naval) Squadron: N.534, N.5364, N.5372, N.5373, N.5377 (later to No. 9 (Naval) Squadron), N.5387 (Aircraft “15”), N.5421 (also used by No. 8 (Naval) Squadron), N.5422, N.5425, N.5426, N.5427, N.5428, N.5432,N-5435,N.5436, N.5437 (later to No. 10 (Naval) Squadron), N.5438, N.5440, N.5441, N.5443, N.5444, N.5445, N.5446, N.5447, N.5451, N.5452, N.5453, N.5454 (“1”), N.5455 (also used by No. 8 (Naval) Squadron), N.5459 (later to No. 9 (Naval) Squadron), N.5461, N.5466 (formerly of No. 10 (Naval) Squadron), N.5472 (“17”), N.5475 (“18”; later to No. 9 (Naval) Squadron), N.5476, N.5479 (“8”), N.5480 (later to No. 10 (Naval) Squadron), N.5484 (later to Nos. 9 and 12 (Naval) Squadrons), N.5485, N.5488, N.5490 (later to Nos. 9 and 10 (Naval) Squadrons), N.5491, N.5494, N.6291 (also used by No. 8 (Naval) Squadron), N.6292 (also used by No. 8 (Naval) Squadron), N.6296, N.6299 (also used by No. 8 (Naval) Squadron), N.6300, N.6303, N.6304 (also used by No. 10 (Naval) Squadron), N.6308, N.6309. Used by No. 8 (Naval) Squadron: N.504, N.5421 (also used by No. 1 (Naval) Squadron), N.5434, N.5442, N.5449, N.5450, N.5455 (a^so used by No. 1 (Naval) Squadron), N.5458 (also used by No. 10 (Naval) Squadron), N.5460, N.5464 (also used by No. 10 (Naval) Squadron), N.5465, N.5468, N.5469, N.5471, N.5472 (also used by No. 1 (Naval) Squadron), N.5474, N.5477, N.5481, N.5482, N.5493 (flown by Flt.-Lt. R. A. Little), N.6290, N.6291 (also used by No. 1 (Naval) Squadron), N.6292 (also used by No. 10 (Naval) Squadron), N.6299 (also used by No. 1 (Naval) Squadron), N.6301. Used by No. 9 (Naval) Squadron: N.5374, N.5377 (formerly of No. 1 (Naval) Squadron), N.5378, N.5459 (formerly of No. 1 (Naval) Squadron), N.5462, N.5475 (formerly of No. 1 (Naval) Squadron), N.5484 (formerly of No. 1 (Naval) Squadron, later to No. 12 (Naval) Squadron), N.5489, N.5490 (formerly used by Nos. 1 and 10 (Naval) Squadrons). Used by No: 10 (Naval) Squadron: N.533, N.5354, N.5355, N.5359, N.5366, N.5367, N.5368, N.5376, N.5380, N.5381, N.5389, N.5429, N.5437 (formerly of No. 1 (Naval) Squadron), N.5458, N.5464, N.5466 (later to No. 1 (Naval) Squadron), N.5478, N.5480 (formerly of No. 1 (Naval) Squadron), N.5483, N.5487, N.5490 (flown by Flt.-Cdr. R. Collishaw; formerly of No. 1 (Naval) Squadron, later to No. 9 (Naval) Squadron), N.5492 (flown by Collishaw), N.6295 (formerly of No. 8 (Naval) Squadron), N.6302, N.6304 (also used by No. 1 (Naval) Squadron), N.6306, N.6307. Used by No. 12 (Naval) Squadron: N.5361, N.5484 (formerly of Nos. 1 and 9 (Naval) Squadrons). Other machines: N.533-N.538 had twin Vickers guns. N.541 and N.542 had been delivered to France, but were returned to the R.N.A.S. N.5385 and N.5388 were sold abroad. N.5424: R.N.A.S. Manston. N.5431: No. 2 Wing R.N.A.S., Mudros, and “E” Squadron.

Показать полностью

O.Thetford British Naval Aircraft since 1912 (Putnam)

Sopwith Triplane

The Sopwith Triplane was one of the great successes of the First World War. Its unusual configuration bestowed such qualities as a remarkable rate of roll and a fast climb, both invaluable in air combat. It was used only by the RNAS, and it gained complete ascendancy over the Western Front during the heavy aerial fighting of 1917.

In the Sopwith chronology the Triplane bridged the gap between the Pup and the Camel, and the first prototype (N500) did Service trials with Naval 'A' Fighting Squadron at Furnes in June 1916. Production Triplanes entered service with No.1 and 8 (Naval) Squadrons in February 1917 and with No.10 (Naval) Squadron in May. Some remarkable engagements were fought by such redoubtable Triplane pilots as Sqn Cdr C D Booker, DSC, and F/Sub-Lt R A Little, of 'Naval Eight' and F/Sub-Lt Raymond Collishaw of 'Naval Ten'. The Triplanes of Collishaw's 'B' Flight (named Black Death, Black Maria, Black Roger, Black Prince and Black Sheep) became the terror of the enemy: between May and July 1917 they destroyed 87 German aircraft. Collishaw personally accounted for 16 in 27 days and shot down the German ace Allmenroder on 27 June.

The Triplane's career was glorious but brief. It remained in action for only seven months; in November 1917 the Camel had supplanted it in squadrons. Total deliveries to the RNAS amounted to 149. All production aircraft were built by sub-contractors: 104 from Clayton & Shuttleworth and 43 from Oakley. The last Triplane (N5912), delivered by Oakley Ltd on 19 October 1917, survives in the RAF Museum at Hendon.

From February 1917 Triplanes had a smaller tailplane of 8 ft span instead of the original Pup-type of 10 ft span. This accompanied the change to a 130 hp engine and improved diving characteristics.

UNITS ALLOCATED

Nos. 1, 8, 9, 10 and 12 (Naval) Squadrons. Western Front. One aircraft (N5431) used by 'E' Squadron of NO.2 Wing. RNAS. in Macedonia.

TECHNICAL DATA

Description: Single-seat fighting scout. Wooden structure, fabric covered.

Manufacturers: Sopwith Aviation Co Ltd. Kingston-on-Thames. Sub-contracted by Clayton & Shuttleworth Ltd. Lincoln (N533-538, N541-543, N5420-5494 and N6290-6309) and Oakley, Ltd, Ilford (N5350-5389 and N5910-5912).

Power Plant: One 110 hp or 130 hp Clerget.

Dimensions: Span. 26 ft 6 in. Length, 18 ft 10 in. Height, 10 ft 6 in. Wing area, 231 sq ft.

Weights: Empty. 1,101 lb. Loaded. 1,541 lb.

Performance (with 130 hp Clerget): Maximum speed, 113 mph at 6.500 ft. Climb, 22 min to 16.000 ft. Endurance, 2 3/4 hr. Service ceiling, 20,500 ft.

Armament: One fixed, synchronised Vickers machine-gun was standard, but a few aircraft had twin Vickers.

Показать полностью

H.King Armament of British Aircraft (Putnam)

Triplane. The second Sopwith fighter produced in 1916, the Triplane was armed, with only three known exceptions, in the manner of the standard Pup, the single Vickers gun lying on the centre line ahead of the cockpit and having Scarff-Dibovsky synchronising gear. Ammunition supply was 500 rounds, and the Sopwith padded screen was fitted. That the Triplane had the 'Scarff Patent Gun Mounting No.3 Made by The Sopwith Aviation Co Ltd. Kingston-on-Thames', was attested by a plate on the instrument panel. Of the three exceptions mentioned, one was the installation of two Vickers guns in a small number of aircraft; another was the fitting of a Lewis gun (additional to the standard Vickers installation) at the root of the port middle wing; and the third was the elevating of the Vickers gun to fire upward at an angle of about five degrees. This last installation entailed fitting an Aldis sight with a special graticule and was intended for stern or underneath attack at relatively long range.

Показать полностью

Журнал Flight

Flight, April 4, 1918.

THE SOPWITH TRIPLANE.

The following particulars of the Sopwith triplane are translated from German aeronautical journals, and we cannot, of course, vouch for the accuracy of the data given, nor can we, for obvious reasons, point out any mistakes that may be present. In spite of this, however, we have thought the following particulars of sufficient interest to include them in our series of descriptive articles on aeroplanes.-ED.]

IN Deutsche Luftfahrer Zeitschrift of August 22nd, 1917, Dipl. Ing. Roland Eisenlohr gives the following description of the Sopwith triplane: Among the new types of aeroplanes which the war has brought into being, the Sopwith occupies a unique position, as being the first triplane to be put into practical use. After some not very successful experiments in the earlier days of aviation, carried out in Germany by Hans Grade in 1907, in England by A. V. Roe, and in France by Goupy, this form of construction had fallen into disuse, and no great future prospects were anticipated for this type of machine.

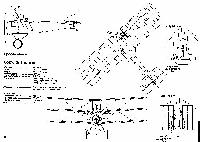

What probably has led to the return of this form of construction is probably the small span which it enables one to use. Another advantage of the triplane arrangement is that the aspect ratio, which should not be less than 6, but which in many machines of short span often has to be considerably less, can be more easily arranged for in the triplane. Thus in the case of the Sopwith triplane the chord is only little over 1 metre, and the span is 8 metres. The increased wing resistance is counteracted by the employment of only one strut on each side and a very simple wing bracing. Furthermore it is possible, owing to the light loading of the wings, to construct the wing spars considerably lighter, and still have a comparatively great free length of spar, in the case of the Sopwith triplane about 2.75 m. with an overhang of 1.40 m. The weight of the total wing area will therefore scarcely come out greater than in the case of a biplane of the same area. Possibly also the arrangement of the wings is advantageous as regards the view obtained by the pilot, as the middle wing is about on a level with his eyes, and the upper and lower wings, on account of their small chord, do not obstruct the view to as great an extent as the wings of the ordinary smaller biplane having a greater wing chord. While both lift wires pass in front of the middle wing, the landing wire runs through it. The bracing cables for the body struts are crossed in the case of those running forward to the nose of the machine, while those bracing the struts in a rearward direction are straight. The gap between the wings is 90 centimetres, and the stagger is about 25 per cent. All the wings are fitted with wing flaps connected by a vertical steel band. In the nose the body carries a 110 h.p. Clerget rotary motor, enclosed in a circular cowl, which projects below the body in order to allow the air to escape.

The body is of rectangular section, rounded off in front by means of a light wooden framework in order to make it merge into the curve of the engine cowl. The width of the fuselage is 0.70 m., and it tapers to a vertical knife-edge at the back, to which the rudder is hinged. The elevator is in two parts, and has in front of it a tail plane of about 3 metre span, which, as in all Sopwith machines, can have its angle of incidence adjusted during flight.

The area of the Sopwith triplane is 27 square metres, so that for a total weight of 670 kilogs, the wing loading is only 25 kilogs. per square metre. With such a light loading the machine has undoubtedly a considerable speed and a very good climb. Further particulars relating to these have not yet been published up to the present. The triplane is built both as a single-seater and as a two-seater, and has always a fixed machine-gun in front above the fuselage, and in the case of the two-seater another machine gun operated by the observer. This increases the weight of the two-seater by about 100 kilogs.

The under-carriage consists, as in all Sopwith machines, of two V's of steel tubing and a divided wheel axle, the hinge of which is braced from the fuselage.

The following remarks are taken from the Flugsport :-

The fuselage with tail plane and rudder is the same as that of the small Sopwith single-seater biplanes. The three wings have a span of 8.07 m. and a chord of 1 m. The lower and middle wings are attached to short wing sections on the fuselage. The upper plane is mounted on a canopy [the German term for a small centre section supported by struts from the body-ED.]. Both spars of the upper wing are left solid, while those of the lower and middle are of I-section. The interplane struts, which are of spruce, and of streamline section, run from the upper to the lower wing, and the inner ones from the upper wing to the bottom rail of the fuselage. In order to give a better view the middle wing, which is on a level with the pilot's eyes, is cut away near the fuselage.

The wing bracing is in the form of streamline wires of 1/4-in. diameter. The very simply arranged landing wires are in the plane of the struts, while the bracing of the body struts, as well as the duplicate lift wires, are taken further forward. From the rear spar of the middle wing, wires are run forward and rearward to the upper rail of the fuselage, and the lower wing also has a wire running forward to the lower rail of the body. All the planes have wing flaps, and inspection windows of celluloid are fitted over the pulleys for the wing flap cables.

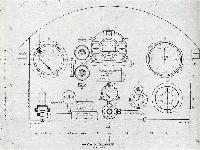

The motor is a 110 h.p. Clerget, and the petrol is led to the engine by means of a small propeller air pump mounted on the right hand body strut. As the air screw was not in place we cannot give details of it. In the pilot's seat were the following instruments :- On the right a hand wheel for varying the angle of incidence of the tail planes, a hand operated air pump, and a petrol indicator. In the middle air speed indicator, manometer, clock, revs, indicator, and switch. On the left a petrol tap, lever for regulating the air, and lever for regulating the petrol. The weight of the machine empty was found to be 490 kilogs., and if the useful load is assumed to be 200 kilogs., we obtain a total weight of 690 kilogs., which, with an area of 21.96 sq. metres, would give a loading of 31.4 kilogs. per square metre.

Further, the following particulars are given :- Motor: Clerget, nominal h.p. 110, brake h.p. 118; fuel capacity for two hours, petrol 85 litres, oil 23 litres; area of wings and flaps (square metres), upper 7.90, middle 6.96, lower 7.10, total 21.96; area of elevators 6 by .5, of wing flaps 1.10, of rudder .41. Angle of incidence (degrees): upper wing, root + 1, tip - .8; middle, root + 1.5, tip + 1.5; lower, root +.5, tip - .5; tail plane, variable + 2 to - 2 degrees. Loading per sq. metre, empty 22.3, fully loaded 31.4; loading per brake h.p., empty 4.15, fully loaded 5.85.

Weights.

Fuselage with under-carriage and accessories 123. 5 kilogs.

Wings 135

Tail plane, rudder and elevator 13

Engine 160

Petrol tank 15

Oil tank 8.5

Propeller 16

Engine accessories 16

Mounting 3

--- All 490

Pilot 80

Gun and ammunition 40

85 litres of petrol and 23 litres of oil 80

--- All 200

Flight, February 6, 1919.

"MILESTONES"

THE SOPWITH MACHINES

The Sopwith Triplane. (May 28, 1916)

Amongst all the Sopwith productions, nearly all of which have attained great fame - so much so, indeed, that their type names are veritably household words - none is more characteristic than the triplane, affectionately known as the "Tripe" or "Tripehound." This machine was fitted with 130 h.p. Clerget engines. The principal objects aimed at in this notable design were, first, the attainment of a high degree of visibility, or, rather, the reduction to a minimum of the pilot's blind angle. With his head on a level with the intermediate plane, he enjoys a practically unrestricted arc of vision through about 120#, whilst sections cut out of the centre of the intermediate plane enable him to have a good view of the ground when landing, the position of the cockpit being such that the bottom plane has no restricting influence on the view. The narrowness of the chord made available by the use of three main planes also allowed the pilot an exceptional view upwards and to either side, an important consideration in a purely offensive machine. The second object aimed at was an increase in manoeuvrability, and the triplane principle was adopted to secure this purpose in consequence of the fact that, owing to the narrow chord, the shift of the centre of pressure with varying angles of incidence is relatively smaller than in a biplane, and consequently demands a shorter length of fuselage to carry the tail. At the same time the small span reduces the moments of inertia in the horizontal plane, and a machine is thus obtained which is highly responsive to its controls and which can add the important ability to dodge to its other strategic advantages The consideration of movement of the centre of pressure enabled single I-struts to be adopted in place of the usual pairs springing one from each spar. This construction also leads to a sensible simplification of the wiring system. Ailerons of the unbalanced type are fitted to all three planes.

Показать полностью