В.Кондратьев Самолеты первой мировой войны

РАФ B.E.2c/B.E.2d/B.E.2e / RAF B.E.2c/B.E.2d/B.E.2e

Весной 1914 года инженер завода РАФ Е.Т.Баск работал над повышением характеристик B.E.2. В результате возник B.E.2c со сдвинутым назад нижним крылом, измененной формой стабилизатора и новой конструкцией шасси без противокапотажных лыж. Кроме того на хвосте появился киль, а на крыльях - элероны. Самолет отличался высокой устойчивостью и мог летать с брошенной ручкой. Незадолго до войны он успешно прошел испытания и был рекомендован к серийной постройке. Одновременно, хотя и в меньшем количестве, выпускался B.E.2d, отличавшийся только небольшим дополнительным бензобаком под верхним крылом. Всего в 1914-15 гг. 22 завода собрали более 1500 B.E.2c и d. 1308 из них было на вооружении RFC.

Разведчики завода РАФ применялись на всех фронтах первой мировой, где воевали англичане. B.E.2c и d составляли матчасть 14 дивизионов RFC и одного авиакрыла RNAS, 17 дивизионов летали на B.E.2e. Несмотря на то, что весьма посредственные летные и боевые характеристики этих аппаратов делали их легкой добычей немецких истребителей, B.E.2c были переведены на учебные аэродромы только в марте 1917-го, а B.E.2e провоевали до конца войны. Однако мало кто из них выдерживал более 20 боевых вылетов.

Кроме англичан на B.E.2 летали бельгийцы, норвежцы и русские. Бельгийцы коренным образом переделали 30 полученных от союзников B.E.2c, заменив двигатели РАФ 1a на гораздо более мощные "Испано-Сюизы" и поменяв местами пилота и летнаба. При этом наконец появилась возможность установить в задней кабине нормальную пулеметную турель.

Истребители

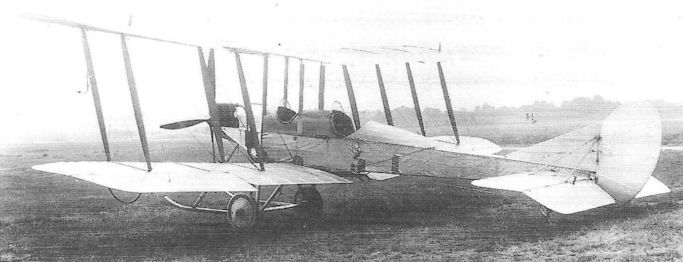

В 1913 году на вооружение Королевского воздушного корпуса был принят самолет РАФ BE.2 - двухместный многоцелевой цельнодеревянный двухстоечный биплан с полотняной обшивкой, разработанный конструкторским коллективом государственного авиазавода "Ройял Эйркрафт Фэктори" (Royal Aircraft Factory, сокращенно - РАФ) под руководством Дж. Де Хэвилленда и Ф.М.Грина. Сокращение BE расшифровывалось как Bleriot Experimental - "экспериментальный самолет типа "Блерио". Так англичане поначалу называли все аэропланы с тянущими винтами и двигателями в носу фюзеляжа.

Первые модификации ВЕ.2 не несли стрелкового вооружения и использовались на раннем этапе Мировой войны в качестве разведчиков и легких бомбардировщиков.

В 1914-м инженер завода РАФ Е.Т. Баск спроектировал очередную модификацию аэроплана - BE.2c, на базе которой в следующем году были созданы первые английские импровизированные истребители ПВО, предназначенные для ночного патрулирования и перехвата германских "цеппелинов", совершавших налеты на Англию. Эти аэропланы вооружались пулеметом "Льюис", закрепленным перед кабиной пилота на специальном кронштейне, позволявшем стрелять вертикально вверх или под углом к вертикали. Угол стрельбы можно было в небольших пределах регулировать в полете.

По имени своего изобретателя - капитана авиации Л.А.Стрейнджа эти установки получили название "лафеты Стрейнджа" (Strange Mount). Необходимость в них обуславливалась тем, что обычная высота полета дирижаблей намного превосходила предельный потолок тогдашних английских перехватчиков. И вести огонь по противнику британские летчики могли только пролетая в нескольких сотнях метров под ним.

Несмотря на всю сложность подобной тактики и примитивность вооружения, английским пилотам BE.2c удалось сбить три германских дирижабля.

Иногда, вместо пулеметов на "лафетах Стрейнджа" (или в дополнение к ним) истребители BE.2c вооружались противоаэростатными ракетами "Ле Прие". 10 реечных пусковых установок таких ракет (по пять с каждой стороны) крепились к внешним стойкам бипланной коробки.

Как правило, истребители ПВО на базе BE.2c были одноместные. Передняя кабина летнаба у них заделывалась, а на ее месте устанавливали дополнительный топливный бак. Но встречались и обычные двухместные машины, просто летчик вылетал на перехват в одиночку.

BE.2c и его следующий вариант BE.2d, отличавшийся только наличием небольшого дополнительного бензобака под верхним крылом, строились в Великобритании на 22-х заводах массовой серией. Всего построено свыше 1500 экземпляров. Сколько из них применялось в качестве истребителей, точно не известно. Предположительно, речь должна идти о нескольких десятках.

Большинство BE.2c было оснащено двухрядными восьмицилиндровыми двигателями воздушного охлаждения РАФ 1a мощностью 90 л.с. Реже применялись американские "Кертисс" OX-5 той же мощности или 105-сильные РАФ 1b.

Модификации

B.E.2с - двухместный разведчик и легкий бомбардировщик, значительно модернизированный. Верхнее крыло вынесено перед нижним. Крылья оборудованы элеронами, а законцовки их стали не эллиптические, а трапециевидные. Горизонтальное оперение новое, прямоугольное. Вертикальное оперение оборудовано килем. Установлен более мощный двигатель RAF-1 (90 л. с.), уменьшено его капотирование. Шасси без противокапотажных лыж. На эти машины стали ставить пулемет "Виккерс".

B.E.2d - тот же B.E.2с, но наблюдатель сидел не в передней, а в задней кабине.

ЛЕТНО-ТЕХНИЧЕСКИЕ ХАРАКТЕРИСТИКИ

B.E.2c B.E.2d

Размах, м 10,97 10,97

Длина, м 8,31 8,31

Высота, м 3,40 3,40

Площадь крыла, кв.м 33,50 33,50

Сухой вес, кг 620 602

Взлетный вес, кг 970 953

Двигатель RAF-1 RAF-1

мощность, л.с. 90 90

Скорость макс., км/ч 129 129

Дальность полета, км 300 300

Набор высоты, м/мин 1500/24

Потолок, м 3050 3050

Экипаж, чел 2 2

Вооружение 1 пулемет 1 пулемет

44 кг бомб 44 кг бомб

Показать полностью

А.Шепс Самолеты Первой мировой войны. Страны Антанты

RAF B.E.2 1912 г.

Самолет проектировался и строился в 1911-1912 годах с участием известного английского авиаконструктора Джефри де Хевилленда.

B.E.2 - двухместный двухстоечный биплан деревянной конструкции. Фюзеляж тонкий - деревянный каркас обтянут полотном. Кабины пилота и наблюдателя (пассажира) неглубокие, и люди на треть корпуса находятся в потоке. Двигатель 8-цилиндровый, воздушного охлаждения, рядный, V-образный, установлен на металлической раме. Двигатель частично закапотирован, а цилиндры находятся в потоке. Крылья двухлонжеронные, деревянные, обтянуты полотном. Стойки бипланной коробки также деревянные. Расчалки выполнены из стальной профилированной ленты. Начиная с серии В.Е.2c крылья оборудовались элеронами. Изменены законцовки крыльев. Горизонтальное оперение нерегулируемое, обычной конструкции. Вертикальное оперение также обычное, на машинах серии "а" и "b" безкилевое, начиная с серии "c" уже устанавливался киль. На этих же машинах начали ставить горизонтальное оперение новой конструкции, прямоугольное, большего размаха. Шасси жесткой конструкции, на машинах первых двух серий - с противокапотажными лыжами. Стойки шасси деревянные. Хвостовой костыль с рыжачной амортизацией. Выхлопные коллекторы выводились первоначально под нижнее крыло, позднее - над центропланом или по бортам. Начиная с серии "c" устанавливалось вооружение - 1-2 пулемета. Управление тросовое, причем на учебных машинах - двойное.

Спроектированный как учебный самолет, с началом Первой мировой войны он использовался и строился как разведчик и легкий бомбардировщик.

Всего с 1912 по 1916 год двадцатью двумя английскими фирмами построено 3535 машин всех модификаций. С 1916 года они заменялись в строевых частях машинами Де Хевилленд D.Н.4 и D.Н.9. Но отдельные машины эксплуатировались в гражданском варианте до 1925 года.

Модификации

В.Е.2с - двухместный разведчик и легкий бомбардировщик, значительно модернизированный. Верхнее крыло вынесено перед нижним. Крылья оборудованы элеронами, а законцовки их стали не эллиптические, а трапециевидные. Горизонтальное оперение новое, прямоугольное. Вертикальное оперение оборудовано килем. Установлен более мощный двигатель RAF-1 (90 л. с.), уменьшено его капотирование. Шасси без противокапотажных лыж. На эти машины стали ставить пулемет "Виккерс".

В.Е.2d - тот же В.Е.2с, но наблюдатель сидел не в передней, а в задней кабине.

Показать полностью

P.Hare Royal Aircraft Factory (Putnam)

B.E.2c

Representing the culmination of E T Busk's investigation into aeroplane stability, the B.E.2c was so different from earlier B.E.2 variants as to be almost a totally new design, yet it retained an obvious family resemblance to its forebears.

Before and immediately after the outbreak of the First World War inherent stability was almost universally considered to be the most desirable attribute of an aeroplane employed in reconnaissance, the primary function of most military machines at that time. A mount which possessed true inherent stability freed its pilot from the need to make constant control inputs, and allowed him to concentrate his attention upon his military duties.

To achieve this desirable quality in the Royal Aircraft Factory's most popular design, Busk took production B.E.2b 602, added a triangular fin, substituted a new non-lifting tailplane of almost rectangular planform, and introduced twenty-four inches of positive stagger. This was done by moving the lower wing back to return the centre of pressure to its correct position, following the loss of the lift previously contributed by the tailplane. The wing structure was almost totally new, being of R.A.F.6 aerofoil section, with ailerons replacing the wing-warping used in previous models. The dihedral angle was increased to 3 1/2, and cutouts were made in the trailing edge of the lower wing roots to restore the pilot's view of the ground.

Busk took the converted 602 for its first flight on 30 May 1914, and thereafter made numerous short flights to enable its stability to be tested and demonstrated. On 9 June it was flown to Netheravon on Salisbury Plain to visit the RFC's 'Concentration Camp'. Its pilot on this occasion was Maj W S Brancker, who, although he was not an experienced pilot, recorded that, after climbing to 2,000ft and setting course, he was able to make the forty-mile journey without placing his hands on the controls until he was preparing to land. He spent his time writing a report on the countryside passing below, although he did admit to the inclusion of a number of extraneous dots and dashes caused by the more violent bumps or gusts.

This demonstration of the benefits of inherent stability was sufficient to ensure that the B.E.2c was put into production by private constructors to supersede the earlier variants in service with the RFC.

Meanwhile, 602 again visited the Concentration Camp on 19 June and stayed there for a week, affording a number of pilots an opportunity to experience its stability at first hand, before returning to Farnborough on the 26th. It was handed over to No 4 Squadron in July, and at the outbreak of war returned to the Aircraft Park, where it was dismantled and crated for shipment to France. When finally reassembled it was erroneously numbered 807, a serial which, it was later realised, duplicated one already issued by the Navy, and it was renumbered 1807. As such it saw service with No 2 Squadron until December, when it returned to England to finish its days in a training unit, being finally struck off charge on 14 December 1915.

Another early variant, 601, was also converted into a B.E.2c. It was fitted with a prototype R.A.F.1a engine, which was dimensionally similar to the Renault but which provided an additional twenty horsepower. On 5 November it caught fire in the air and was completely destroyed, with the tragic loss of its pilot, the aeroplane's designer, Edward Busk.

Although early production B.E.2cs retained the 70hp Renault engine which powered the earlier variants, the Factory's own R.A.F.1a became the standard powerplant as soon as it was available in sufficient numbers. New vertical-discharge exhaust pipes, terminating just above the upper wing centre-section, together with a neat cowling for the engine sump, distinguished the R.A.F.1a-powered examples. A plain vee undercarriage was introduced at the same time, replacing the twin-skid pattern of the earlier machines.

The first production machine, built by Vickers and given the serial 1748, was delivered to the Aeronautical Inspection Department at Farnborough by 19 December 1914. It was followed by the first Bristol-built example, 1652, on 4 January 1915, this aircraft becoming the first production example to go to France, which it did on 25 January. By the end of March there were twelve in service, and by the end of the year there were more than ten times that number.

The B.E.2c's stability was initially well received by service pilots, and remained so in the less demanding theatres of war, earning the machine such affectionate nicknames as Stability Jane or the Quirk. One pilot (Maj WG Moore, Early Bird (Putnam, London, 1963)) wrote of it:

"But the beauty of these machines was that, once you were up to your cruising height, you could adjust a spring which would hold your elevator roughly in the position you wanted for level flying, and you could afford to ignore totally the violent bumps that threw up one wing-tip and then the other. With your rudder central and held in that position by a spring, you could fly hands-off, because the machine was automatically stable and would right itself whatever position it got into provided there was enough space between you and the ground. We used to try, when well up, to see if there was any position we could put them in from which they would not right themselves if left alone. If you pulled them up vertically (so that they hung momentarily on the propellers) and then let go everything, they would tail slide very gently and then down would go the nose until the machine gained flying speed and everything would be normal again."

As originally conceived, the B.E.2 was unarmed. When the fitting of armament became desirable, the location of the observer in the front cockpit, which had been done for sound reasons, made the installation of any kind of defensive weaponry almost impossible. Similarly, the Allies' lack of any synchronisation gear, to allow a gun to fire forwards through the propeller disc, rendered the provision of offensive armament equally difficult. However, almost immediately the type entered service attempts were made to arm it, initially with rifles or pistols and later with machine guns, usually the comparatively light, drum-fed Lewis. The rifles and pistols were usually hand held, but the machine guns required a fixed mounting to enable them to be operated with any effect.

At first the necessary mountings were fabricated, ad hoc, in squadron workshops, but they gradually became standardised into a number of officially adopted types. The earliest of these appears to have been the 'candlestick' mounting, fixed to the cockpit rim, into which a spike or pivot pin attached to the gun could be inserted. This allowed the gun to be swivelled as necessary to engage the enemy, but relied entirely on the observer's skill in avoiding hitting parts of his own machine. This was superseded by the No 2 Mk 1 mounting designed by Lt Medlicott, and frequently known by his name, in which the gun's pivot pin was placed in a socket which was supported from a tube attached to the front centre-section struts, and arranged to slide up and down. A wire guard was frequently fitted which limited the muzzle movement and prevented the observer from shooting his own propeller.

A 'goalpost' mounting between the cockpits, officially designated the No 10 Mk 1, allowed the observer to fire to the rear, over the pilot's head. This gave some measure of protection against attack, but required courage and co-operation in use because the gun's barrel was barely inches above the pilot's head. It was unusual for a machine to be burdened with the weight of more than one gun, and the observer had to transfer it from mounting to mounting as the need demanded. Wooden racks were often fitted to the fuselage sides, outside the rim of the observer's cockpit, to hold spare ammunition drums.

Another type of mounting, more common to single-seaters, had a Lewis gun fixed to the fuselage side, firing forward at an angle to miss the propeller and with its muzzle held in place by cross-wires. A number of such installations were made on B.E.2cs to satisfy the whim of the more aggressive pilots.

None of these arrangements was entirely satisfactory, and they were far from being universally fitted, so for all practical purposes the B.E.2c remained virtually defenceless. Consequently the advent of true fighter aeroplanes, such as the Fokker monoplanes of 1915 and the Albatros biplanes which followed them, meant that the B.E.2c became easy prey, along with its equally unarmed contemporaries. Thus Noel Pemberton Billing was able to shock Parliament, and the nation, with his accusations of incompetence and murder, and so indirectly bring to an end the family of Royal Aircraft Factory aeroplanes.

A few machines were also fitted with bomb racks, either under the wings to carry four 20lb bombs, or under the fuselage, at the centre of gravity, where one 112lb bomb was the normal load.

Losses to ground fire, as the B.E.s monotonously patrolled over the trenches on reconnaissance or artillery observation duties, were also a problem and, in an attempt to provide a solution, a small number of machines were fitted with armour plate which covered the forward fuselage. While this effectively protected the engine, fuel tank and crew against small-arms fire, the reduction in streamlining, together with the addition of over 400lb in weight, so reduced performance that the idea was shortlived.

In common with its predecessors the B.E.2c was used by the Factory as a test bed for a wide range of aeronautical experiments and investigations, a purpose for which its stability and entirely predictable performance made it ideal. The machines used in such experiments were not built at Farnborough, but were standard production machines, built by private contractors and modified as required after inspection.

An oleo undercarriage incorporating a small buffer-type nosewheel was fitted to a few B.E.2cs, but any improvement in landing, and in handling on the ground, could not compensate for the reduction in performance caused by the increased weight and considerable drag, and it was not adopted for general use.

Another undercarriage experiment, which was conducted at the School of Aerial Gunnery, Loch Doon, in November 1916, comprised the removal of the wheels of 4721, an early Vickers-built machine, and the substitution of a central float manufactured by S E Saunders. This was simply attached to the undercarriage skids, and a small tail float was also fitted. Neither the intention nor result of this experiment are now recorded, but it is doubtful whether it served any useful purpose.

Like most other aeroplanes which had a lengthy service career, the B.E.2c was constantly modified and improved with a view either to simplified production or improved performance. It was with the latter object in mind that the wing section was changed early in 1916 from R.A.F.6 to R.A.F. 14, with a consequent slight improvement in rate of climb.

As its performance became the subject of growing criticism, several attempts were made to re-engine the B.E.2c with the 150hp Hispano-Suiza, this having been the first projected use for this impressive new engine. The first attempt managed to produce one of the ugliest installations of this neat and attractive powerplant that it is possible to imagine. The engine was partially enclosed within a crude cowling which left the sides of the cylinder blocks exposed, and cooling was provided by honeycomb radiators of unusual construction attached to the fuselage sides. A later installation was made in the Bristol-built machine 2599. This was neater without being neat, for the radiators, which this time were fitted above the cylinder heads, still looked like the afterthought which, in reality, they were. Although the sixty per cent increase in power obviously improved the aeroplane's performance, it was then decided to develop new machines to realise the Hispano-Suiza's full potential, and the plan to fit it in the B.E.2c was discontinued.

For some obscure reason the R.A.F.1a engine was never popular with the RNAS, so some of the few B.E.2cs operated by that service were equipped either with the six-cylinder 75hp Rolls-Royce Hawk or the 90hp Curtiss OX-5, a car-type radiator being used in each case. It seems strange that this simple solution to engine cooling appears not to have been considered by those responsible for the experimental Hispano-Suiza installations.

When nocturnal bombing raids on London and the eastern counties by the huge German rigid airships brought the war to civilians for the first time, it immediately became apparent that some defensive action was urgently needed, as much to preserve the nation's morale as to prevent the relatively small amount of damage that was being suffered. Here the stable B.E.2c came into its own, for, being easy to fly and to land, it made an admirable night-fighter. However, like most contemporary aeroplanes, it lacked the performance to attack the enemy airships under any but the most favourable circumstances. Whilst they were slower, the airships could better any aeroplane's ceiling, and could ascend at an incredible rate simply by releasing large quantities of ballast. In a commendable attempt to overcome the poor climb and endurance of the B.E.2c compared with that of its intended victim, an experiment was made in 1915 in which the aeroplane was suspended from the envelope of a type SS non-rigid airship. It was intended that the 'airship-plane' would patrol at height until the raiders approached, when the aeroplane would detach itself from the envelope and go into the attack. The experiment was discontinued after 21 February 1916, when a fatal accident occurred after the aeroplane failed to release properly.

This was not the only connection between the B.E.2c and the Submarine Scout airship, for the S.S.I class consisted of a Willows-type envelope from which was suspended an aeroplane fuselage, the early B.E.2c being one of three types used, complete with engine, propeller and undercarriage skids. No wheels were needed, because ascents and landings were made without forward motion.

On the night of 2 September 1916 the Schutte-Lanz airship SL11 was spectacularly brought down over Cuffley in Hertfordshire by Lt William Leefe Robinson of No 39 Squadron RFC, flying B.E.2c No 2092, an act for which he was awarded the Victoria Cross. This was not the first time that an enemy airship had been brought down, for Flt Sub-Lt Rex Warneford had brought down the Zeppelin L37 with a bomb more than a year previously, but it was certainly the most public instance. Warneford's action had taken place over the Belgian coast, whereas Leefe Robinson's victim fell in flames where most of the population of London could see it. Before the end of the year four more raiders, the Zeppelins L21, L31, L32, and L34, had fallen to the guns of night-flying B.E.2cs.

The B.E.2c remained in service, in declining numbers, until the end of the war, gradually being superseded by later variants and by newer designs. It saw service with more than a dozen squadrons of the RFC in France, in Home Defence units and training establishments, with the RNAS, and in every theatre of war, including Africa and the Middle East. At one time it was certainly the most efficient and the most numerous aeroplane in use by the British armed forces. That it was allowed to outlive its usefulness was a tragedy that should be blamed upon those who were responsible for its procurement, not upon the machine or its designers.

The B.E.2c did not survive in service use for very long after the Armistice. At least one was retained as a test vehicle at Farnborough until the mid 1920s, and a small number found their way on to the civil register via the numerous disposal sales held after the war's end. Three examples survive in museums.

Powerplant: 70hp Renault V-8; 90hp R.A.F.1a V-8

Dimensions:

span 37ft 0in;

chord 5ft 6in;

gap 6ft 3in;

stagger 2ft 0in;

dihedral 31/2°;

incidence 3 1/2° (R.A.F.6); 4° 9" (R.A.F.14);

wing area 354 sq ft;

length 27ft 3in;

height 11ft 1 1/2in;

wheel track 5ft 9 3/4in.

Weights: (R.A.F.1a) :

1,370lb (empty);

2,142lb (loaded).

Performance: (R.A.F.1a) :

max speed

86mph at sea level;

72mph at 6,500ft;

ceiling: 10,000ft;

endurance 3 1/4hrs;

climb

6min to 3,000ft;

20min to 6,500ft.

B.E.2d

Although it was structurally similar to the B.E.2c, this new variant included dual controls, presumably to give the observer a chance of survival if the pilot was hit. The provision of controls in the front cockpit necessitated the elimination of the fuel tank which was previously installed under the observer's seat, to allow the rudder cables and the torque tube linking the two control columns to pass through this space. A large gravity tank was substituted, positioned beneath the upper port wing near its root, and was connected to an additional gravity tank within the fuselage top-decking, between the cockpits. At the same time the capacity of the pressure tank, located immediately behind the engine, was increased from fourteen to nineteen gallons. Thus the B.E.2d had a total fuel capacity of forty-one gallons, compared with the thirty-two gallons of the B.E.2c, giving it a useful increase in endurance, albeit at the expense of a reduction in the type's already leisurely rate of climb.

Production orders for the B.E.2d were placed in October 1915, and it was built in relatively small numbers by the British and Colonial Aeroplane Company, Ruston Proctor, and Vulcan. Such great things were expected of the later 'e' variant that all unfulfilled orders for earlier models were changed to the latter type, and consequently many machines which began as B.E.2ds were actually delivered as B.E.2es.

Use of the B.E.2d was largely confined to training establishments, where its dual controls were a boon, its endurance allowed the best use to be made of favourable weather, and its outdated performance was no real handicap.

Powerplant: 90hp R.A.F.1a V-8

Dimensions:

span 36ft 10in;

chord 5ft 6in;

gap 6ft 3in;

wing area 354 sq ft;

stagger 2ft 0in;

dihedral 3 1/2°;

incidence 4° 9";

length 27ft 3in;

height 11ft 0in.

Performance:

max speed

88mph at sea level;

75mph at 6,500ft;

ceiling 7,000ft;

climb

12min to 3,000ft;

36min to 6,500ft.

B.E.10

Designed in May 1914, the B.E.10 was developed from the B.E.2c but had a steel-tube fuselage frame, fabric covered and with a deeper coaming than on previous B.E. types, making it somewhat similar to that of the R.E.5. Its oleo undercarriage incorporated a small 'buffer' nosewheel. The wing span - was slightly reduced from that of the B.E.2c, and the ribs were pressed from alloy sheet. The aerofoil section had a reflex trailing edge, and the full-span ailerons could be operated together as flaps. The rudder was of modified shape, and the small high-aspect-ratio triangular fin anticipated that later adopted for the R.E.8.

Surprisingly, power was to be provided by the rather outdated 70hp Renault, although it may well have been intended that the dimensionally similar 90hp R.A.F.1a would be substituted for full-scale production.

No prototype B.E. 10 was built at Farnborough, but four examples were ordered from the British and Colonial Aeroplane Company. The order was cancelled soon after, when it was decided that the B.E.2c would remain the RFC's standard mount, and none were completed, although enough work was done for the Bristol employees to dub it the 'Gas Pipe Aeroplane'.

Powerplant: 70hp Renault V-8

Dimensions:

span 35ft 8in;

chord 5ft 4in;

wing area 355sqft;

length 27ft 1in;

height 10ft 9in.

B.E.11

No drawing or description of this project has survived, and it therefore seems unlikely that it ever progressed beyond the concept stage. It is almost certain that it was yet another variant upon the B.E.2 theme.

Показать полностью

O.Tapper Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft since 1913 (Putnam)

The B.E.2a, B.E.2b and B.E.2c

<...>

After the outbreak of war in 1914, the B.E.2a and the B.E.2b soon gave place to the better-known B.E.2c, which was built in large numbers by numerous contractors, including Armstrong Whitworth. The B.E.2c, which was designed to have automatic stability, according to the ideas of T. E. Busk, had a fuselage similar to that of the B.E.2b, but the wings were of new design, being heavily staggered and with ailerons on all four planes; the new tailplane was rectangular and a vertical fin was added to the rudder. Early examples of the B.E.2c had the 70 hp Renault engine and the characteristic undercarriage skids, but later production models were powered by the 90 hp RAF la engine and had a simplified V-type chassis. The B.E.2c gave good service as a reconnaissance aircraft in the opening stages of the war, but it was quickly outclassed and soon became an easy victim of enemy fighters.

Armstrong Whitworth built eight B.E.2as and twenty-five BE2bs but it has not been possible to trace the Service numbers of these aircraft. The total number of B.E.2cs built by Armstrong Whitworth is uncertain, but two batches built at Gosforth, amounting to 50 aircraft, carried the serial numbers 1780 to 1800 and 2001 to 2029.

B.E.2c

Span: 37 ft 0 in (11.28m)

Length: 27 ft 3 in (8.31m)

Wing area: 371 sq ft (34.47 sq m)

All-up weight: 2.142 lb (972 kg)

Показать полностью

A.Jackson Blackburn Aircraft since 1909 (Putnam)

B.E.2c

A two-seat trainer, bomber and anti-submarine aircraft of wood and fabric construction designed at the Royal Aircraft Factory, Farnborough, and first flown in 1914. Powered by the 70 hp Renault and later by the 90 hp RAF 1A, it was built in large quantities by a number of sub-contractors including the Blackburn Aeroplane and Motor Co Ltd who produced 111 for the Admiralty. The aircraft were constructed on the shop floor in the Olympia Works at Leeds, without jigs, and test flown from the nearby Soldiers' Field, Roundhay Park, by Rowland Ding. After his death, caused by the failure of an interplane strut while he was looping a new B.E.2c on its first flight, production testing was completed by R. W. Kenworthy. Surviving records show that Blackburns completed 40 by July 1915, 35 of the final batch of 50 by 29 December 1917, four more in January 1918 and five in February of that year.

Blackburn-built B.E.2cs, recognisable by the ringed airscrew motif on the fin, were used for training in the UK and on active service in every theatre during the 1914-18 war. Two aircraft, serialled 968 and 969, were shipped to the South African Aviation Corps in April 1915; 3999 was a special aircraft for Admiralty W/T experiments; 1127 was sent to Belgium in exchange for a Maurice Farman biplane; and 9969 is preserved at the Musee de l'Air, Paris.

SPECIFICATION AND DATA

Manufacturers: The Blackburn Aeroplane and Motor Co Ltd, Olympia Works, Roundhay Road, Leeds, Yorks.

Designers: The Royal Aircraft Factory, Farnborough, Hants.

Power Plants:

One 70 hp Renault

One 90 hp RAF 1A

Dimensions:

Span 37 ft 0 in Length 27 ft 3 in

Height 11 ft 11 in Wing area 371 sq ft

Weights: Tare weight 1,370 lb All-up weight 2,142 lb

Performance:

Maximum speed 72 mph Service ceiling 10,000 ft

Climb to 3,500 ft 6 min Endurance 31 hr

Blackburn production:

(a) With 70 hp Renault

Thirty-seven aircraft comprising 964-975 (quantity 12); 1123-1146 (24); 3999 (1).

(b) With 90 hp RAF IA

Seventy-four aircraft comprising 8606-8629 (24) under Contract C.P.60949 15; 9951-10000 (50) under Contract 132110 15.

Total: 111.

Показать полностью

M.Goodall, A.Tagg British Aircraft before the Great War (Schiffer)

Deleted by request of (c)Schiffer Publishing

BE.2c biplane

The BE.2c was the result of a good deal of development work at Farnborough on stability, carried out on examples of its predecessors. The ability of the aircraft to fly, with the minimum of control movement by the pilot, was regarded as a great attribute for a reconnaissance aircraft, the intended role of the BE.2c. The lack of maneuverability was later to become a great disadvantage, when air fighting developed.

The most apparent change from the BE.2b was the use of wing stagger, which was obtained by moving the lower wing back, to compensate for the loss of lift, occasioned by the use of a smaller non-lifting tailplane. The ailerons replaced wing warping on all four wings and a fin was fitted. The twin skid undercarriage of the BE.2b was used on early aircraft, but was later replaced by a vee type with cross axle on most aircraft. The long exhausts, fitted under the fuselage, were shortened later and some machines had exhausts taken up over the top wing. Many changes and operational additions came much later, among which was the introduction of the RAF. la engine, made by the Factory.

The BE.2c was in production by a number of contractors over a long period and was in service until the end of the war.

Power:

70hp Renault eight-cylinder air-cooled vee

90hp RAF.1a eight-cylinder air-cooled vee

Data

Span 37ft

Chord 5ft 6in

Gap 6ft 3in

Area 354 sq. ft *

Area tailplane 36 sq. ft

Area elevators 27 sq. ft

Area rudder 12 sq. ft

Area fin 4 sq. ft

Length 27ft 3in

Height lift 1 l/2in

* Alternative sources quote 371 & 396 sq. ft

Data RAF. 1a

Weight 1,370lb.

Weight allup 2,142lb.

Max speed

86 mph at sea level

72 mph at 6,500ft

Climb to 6,500ft 20min

Climb to 3,000ft 6 min

Ceiling 10,000ft

Endurance 3 1/4hr

Показать полностью

P.Lewis British Aircraft 1809-1914 (Putnam)

B.E.2c

The B.E.2c represented the culmination of E. T. Busk's two years of practical experimenting devoted to developing the machine into a stable aeroplane, as a result of which it was ordered in quantity for the R.F.C. and the R.N. A.S. At the time of its appearance in June, 1914, the B.E.2c's role in war was envisaged as that of reconnaissance, and the decision to order it in numbers appeared to be justified. In the event, however, its lack of manoeuvrability which went with such an exceptionally highly-developed stability brought about its downfall in the skies of battle, where it was, perforce, pressed into carrying out duties for which it was not designed.

The B.E.2c was a direct development of the B.E.2b, but several distinctive changes had been made. Most prominent among these were the adoption of staggered wings, the addition of a triangular tail fin, a revised tailplane of rectangular shape and new wing-tips. At first, the 70 h.p. Renault was given lengthy exhaust pipes which extended along the lower fuselage, but these were shortened in later versions.

In June, 1914, the prototype was flown from Farnborough to Netheravon by Major Sefton Brancker, who left his starting-point at 2,000 ft. and arrived over his destination at 20 ft. without using the controls, his hands being occupied with writing a reconnaissance report during the flight. When war broke out on 4th August, 1914, this machine was the only B.E.2c flying. The sub-contractors asked to produce the design found, on examination of the plans, that the structure was a comparatively complicated one and was not simple to build. Three months after war was declared, Edward Busk, the person who had done most to develop the machine into a successful flyer, was killed when his B.E.2c crashed on 5th November on Laffan's Plain.

SPECIFICATION

Description: Two-seat tractor biplane. Wooden structure, fabric covered.

Manufacturers: Royal Aircraft Factory, Farnborough, Hants.

Power Plant: 70 h.p. Renault.

Dimensions: Span, 37 ft. Length, 27 ft. 3 ins. Height, 11 ft. 15 ins. Wing area, 371 sq. ft.

Weights: Empty, 1,370 lb. Loaded, 2,142 lb.

Performance: Maximum speed, 75 m.p.h. Service ceiling, 10,000 ft. Endurance, 3.25 hrs.

Показать полностью

J.Bruce British Aeroplanes 1914-1918 (Putnam)

B.E.2c, 2d and 2e

EDWARD TESHMAKER BUSK left King’s College, Cambridge, in 1908. He took the Mechanical Sciences Tripos in 1907, and spent a further year at Cambridge in research. From 1909 until mid-1911 he worked with Halls and Co. of Dartford, and in 1911 he began to develop his interest in aviation.

At that early date he was interested in the problem of inherent stability in aeroplanes, and made some investigations into the nature and causes of wind gusts. Early in 1912, he began to learn to fly at Hendon at the flying school of the Aeronautical Syndicate, Ltd., but did not take his Royal Aero Club certificate.

In June, 1912, Professor Hopkinson of King’s College recommended Busk to Mervyn O’Gorman, the Superintendent of the Royal Aircraft Factory, for the post of Assistant Engineer Physicist, and Busk took up his appointment on June 10th, 1912.

His work at Farnborough consisted chiefly of research in aircraft stability and control design. He realised that, in order to carry out his experiments thoroughly, he must complete his flying training: this he did under the tuition of Geoffrey de Havilland, and by the summer of 1913 was sufficiently skilled as a pilot to be able to begin a series of experiments in stability.

Busk began his investigations with the B.E.2a. He approached his task with perseverance and great courage, for, in establishing the exact degree of instability of the B.E.2a, he flew the machine beyond the limits of its controllability on several occasions. His findings provided data for the design of the R.E.t, which emerged in November, 1913, as the first R.A.F. inherently stable aeroplane, and for a development of the basic B.E.2 design.

The latter machine was designated B.E.2C, and was flying in June, 1914. The prototype had the fuselage, undercarriage and engine installation of the B.E.2b, but new mainplanes with a marked degree of stagger were fitted. Double-acting ailerons replaced the warp control of the earlier B.Es; a fixed fin was added to the tail unit; and a new tailplane was mounted between the upper and lower longerons, braced to the fin by steel-tube struts. The fuselage was a typical wire-braced box girder, made in two parts which were joined just behind the rear cockpit. The wings had wooden spars, ribs and riblets and, in the earlier B.E.2c’s, the external bracing was by cables. The fin and rudder were made of steel tube. The covering was of fabric throughout, apart from the metal engine cowling and the plywood decking about the cockpits.

In June, 1914, Major (later Air Vice Marshal Sir) Sefton Brancker flew the prototype B.E.2C from Farnborough to Netheravon. He climbed to 2,000 feet over Farnborough and thereafter did not touch the controls again until he was at 20 feet on the approach to Netheravon. During his flight he wrote a reconnaissance report of the country over which he flew.

As the summer of 1914 wore on, it became obvious that war was imminent. Aeroplanes were ordered in haste, and it was decided to order the B.E.2C in quantity, since it promised to be superior to the earlier B.E.2 variants in construction and performance. This led to delay, for complete sets of drawings were not immediately available; moreover, some of the contractors for the type had never before built aircraft.

It would be hard to condemn the decision to order what was at that time large-scale production of the B.E.2c: in fact, it was an act of faith and considerable courage. The aircraft had not been fully tested, but it had already shown itself to be an excellent flying machine with remarkable stability, a quality which promised well for its employment as a reconnaissance machine. At that time, aerial combat had not been thought of, save by a few visionaries; and no-one foresaw that the B.E.’s great stability would put it at a serious disadvantage in aerial fighting.

The B.E.2c was not, for its day, particularly simple in its construction, and successive modifications were a sore trial to the first contractors for the type. Among the firms who undertook its manufacture were Messrs G. and J. Weir, Ltd., of Glasgow, and the Daimler Co., Ltd., of Coventry. Contracts were also placed with Sir W. G. Armstrong, Whitworth & Co., Ltd., but after study of the drawings that firm represented that the B.E.2C was unnecessarily complicated. They therefore sought and (what is more remarkable) obtained permission to build an aeroplane which would be simpler but equally efficient. The result was the Armstrong Whitworth F.K.3.

A single B.E.2C was taken to France by the Aircraft Park, which arrived at Boulogne on August 18th, 1914. Production machines began to appear late in 1914, but by March 10th, 1915, the seven squadrons in the field could muster a total of only thirteen B.E.2c’s between them. The first unit to go to France equipped throughout with the type was No. 8 Squadron, R.F.C., which arrived on April 15th, 1915.

The early production B.E.2c’s were very similar to the prototype. They retained the Renault engine and skid undercarriage, but some had a slight refinement in the shape of a cowling over the engine sump. In each outer bay of the wings an auxiliary mid-bay flying-wire was added to the upper front spars. The arrangement of the control cables for the tail surfaces was improved.

The Renault engine which powered the B.E.2c had provided the basis for original design work undertaken at the Factory with the object of producing a satisfactory British power-unit with a reasonable power/weight ratio. This work began in January, 1913, and culminated in the following year in the appearance of the R.A.F. 1 engine of 90 h.p. Like the B.E.2C, the R.A.F. 1 was not fully tested at the outbreak of war, nor were full sets of drawings available, yet it was ordered in quantity from various contractors.� The first R.A.F. 1 was installed in a B.E.2c, but development was delayed by the loss of the engine on November 5th, 1914, when the aircraft in which it was being flown burst into flames at 800 feet above Laffans Plain and crashed. But the crash caused a far greater loss to British aeronautical science than the mere destruction of an engine which could, sooner or later, be replaced: Busk was the pilot of the B.E.2c; and he lost his life.

The production version of the R.A.F. 1 engine was known as the R.A.F. 1a. Deliveries began in the spring of 1915, and the engine became the standard power unit of the B.E.2C. The exhaust pipes varied considerably in length and configuration, but the twin upright stacks running up in front of the centresection were perhaps the best-known arrangement. Many of the B.E.2c’s built for the R.N.A.S. had long pipes running along the fuselage and terminating just abaft the pilot’s cockpit.

At about the same time as the introduction of the R.A.F. 1a engine, the B.E.2c’s undercarriage was modified to consist of two simple vees: each vee was made of steel tube with wooden fairings, and there were two steel-tube spreader bars between which the axle lay. Springing was provided by the 44 feet of 3/8-inch rubber shock cord which bound the axle to each vee strut. Some B.E.2c’s were built with an oleo undercarriage similar to that of the F.E.2b and R.E.7, and a few of these machines went to France. The Daimler Company produced some of the oleo-fitted B.E.2c’s.

Other modifications were introduced as time went on. The tailplane, which was originally made in one piece, was later built in two parts; concurrently, the steel-tube struts bracing the tailplane were replaced by Rafwires.

Rafwires also replaced the cables which had braced the mainplanes of all early B.E.2c’s. The mainplanes themselves were changed: the early machines had had wings of R.A.F.6 section at an angle of incidence of 3 30', but these were changed for surfaces of R.A.F.14 section at 4 09'.

For some months the B.E.2C gave good service as a reconnaissance aircraft, and made occasional bombing attacks. One of the earliest exploits of the latter kind was the daring attack on the enemy airship sheds at Gontrode, made by Lieutenant L. G. Hawker on April 19th, 1915. His B.E.2C carried three bombs.

But in the late summer of 1915, the rather experimental attempts at aerial combat which had occurred up to that time were suddenly superseded by a new fighting technique in which the advantage at first lay wholly with the enemy. The Fokker monoplane was the vehicle which first brought a new weapon into operational use. Armed with a machine-gun which, thanks to a mechanical interrupter gear, could be fired straight ahead through the revolving airscrew, the Fokker spelt doom to many Allied aircraft and particularly B.Es.

In combat, the B.E.2c proved to be nearly helpless. There were several reasons why this was so. Its stability was such that it could not be manoeuvred rapidly; and even if it had been tractable it could not have been provided with effective armament. No British interrupter gear was available at the time, and the observer’s position in the front cockpit, directly under the centre-section, was a severe obstacle to the fitting of any kind of defensive armament.

A remarkable variety of gun-mountings were fitted to B.E.2c’s. Most of them were devised by their crews, but all had one thing in common: they were of little practical use and generally reduced the B.E.’s mediocre performance to a dangerously low level. The observer was usually the gunner, and he had to move his Lewis gun bodily from one mounting to another around his cockpit; but from all save the rearmost his field of fire was hedged about by wings, wires and struts. One of the best arrangements of a Lewis gun fired by the pilot was that devised by Captain L. A. Strange of No. 12 Squadron. The gun was mounted on the side of the fuselage and pointed outwards to clear the airscrew: the pilot had therefore to fly crabwise when he wanted to fire.

The desperation of B.E. crews found expression in a weapon invented by an officer of No. 6 Squadron. From a small winch in the cockpit he lowered a lead weight on a steel cable; this he attempted to entangle in the airscrew of an enemy aircraft by manoeuvring above it. Needless to say, the device was unsuccessful.

From October, 1915, onwards, throughout the months preceding the Battle of the Somme, the history of the war in the air contains a dreary recital of mounting losses, including many B.E.2c’s, inflicted by the Fokker monoplane. Evidence of the Fokker’s effectiveness and the B.E.2c’s defencelessness is provided by the size of the escort which was detailed to accompany a B.E. of No. 12 Squadron on a reconnaissance flight on February 7th, 1916. The flight was not carried out, but the escort was to have consisted of three other B.E.1c’s, four F.E.2b’s, four R.E.7s and one Bristol Scout - twelve machines in all.

In addition to its reconnaissance and artillery-spotting activities, the B.E.2c acted as a bomber on many occasions. Captain Strange, then of No. 6 Squadron, had shown what could be done by his attack on Courtrai station on March 10th, 1915: his B.E.2C was armed with only three 25-lb bombs, but he did sufficient damage to delay rail traffic for three days.

Bombing raids became more frequent as more aircraft became available. The R.F.C.’s first night raid was made by two B.E.2c’s of No. 4 Squadron on the night of February 19th/20th, 1916; the aircraft were flown by Captains E. D. Horsfall and J. E. Tennant. Their objective was Cambrai aerodrome, where Tennant dropped his seven 20-lb Hales bombs on the sheds from 30 feet. Horsfall’s two 112-pounders failed to leave the racks over the target, and did not drop until the B.E. was nearly home again.

On these raids, as on all bombing missions, the B.E.2C was flown without an observer, for it could not lift both bombs and an observer together. Defensive armament was also reduced to a minimum: the pilot usually had nothing more effective than a rifle or carbine. Bombing attacks on enemy railways were carried out by twenty-eight B.E.2c’s during the preparations for the Battle of the Somme, and on July 1st, 1916, the day of the great offensive itself, a similar number made further attacks. On July 28th, the B.E.2c’s of Nos. 8 and 12 Squadrons dropped fifty-seven 112-lb bombs on the railway junction north of Aubigny-au-Bac.

After one or two British aeroplanes had been brought down by rifle and machine-gun fire from the ground the R.F.C. asked for armoured aeroplanes. Some B.E.2c’s were provided with armour about and below the cockpits and engine; but its weight (which was no less than 445 lb) and the total absence of streamlining had a detrimental effect upon the machine’s performance. One of these armoured B.E.2c’s was used by No. 15 Squadron, and was flown on ground-strafing duties by Captain Jenkins of that unit during the Battle of the Somme. In three months it was fitted with no fewer than eighty new wings and many other components.

The B.E.2C was also built in substantial numbers for the R.N.A.S., and that Service was the first to use the type outside France. Two Renault-powered B.E.2c’s reached Tenedos early in April, 1915, to form part of the equipment of No. 3 Wing, R.N.A.S., during the Dardanelles campaign. No. 2 Wing brought six more Renault-powered machines in August.

Many of the B.E.2c’s built with the R.A.F. la engine for the R.N.A.S. had a small bomb-rack directly under the engine; it could carry three bombs. Some of the R.N.A.S. bomber B.E.2c’s had the front cockpit faired over.

On April 3rd, 1915, two B.E.2c’s, numbered 968 and 969, left England for South-West Africa. They had been built for the Admiralty but were transferred to the South African Aviation Corps. They arrived at Walvis Bay on April 30th, but were damaged in trial flights and took no part in the South-West African campaign.

When that campaign was over, some of the officers and men who had taken part in it provided the nucleus of No. 26 Squadron, which arrived at Mombasa with eight B.E.2c’s on January 31st, 1916, for service in German East Africa. The airscrews had not been packed with the machines at Farnborough, so the squadron had to make do with only five spare airscrews, none of which was of the correct type. The B.Es of this squadron did a great deal of excellent work under appalling conditions. On January 30th, 1917, No. 26 Squadron took over three R.A.F.-powered B.E.2c’s of R.N.A.S. type from No. 7 (Naval) Squadron, which had been withdrawn by the Admiralty. It was on one of them, No. 8424, that Captain G. W. Hodgkinson and Lieutenant L. Walmsley made many long-range reconnaissances; the observer carried extra tins of petrol in his cockpit and from them he replenished the tank while in flight.

In the near East, B.E.2c’s flew and fought with Squadrons Nos. 14 and 17 in Egypt; with Nos. 14 and 67 (Australian) Squadrons in Palestine; with No. 30 Squadron in Mesopotamia, where the B.Es helped to drop food to the beleaguered garrison of Kut-al-Imara; and with No. 17 Squadron in Macedonia, whence that unit went from Egypt in July, 1916. One of No. 30 Squadron’s B.E.2c’s was flown as a single-seat fighting scout: with twenty-five gallons of fuel it had a speed of 88 m.p.h. at 2,000 feet, and climbed to 10,000 feet in twenty-two minutes.

In India the B.E.2c was flown by No. 31 Squadron and later by No. 114 Squadron also. There it played a part in quelling the unruly tribes of the North-West Frontier.

The B.E.2C is seldom credited with successes of any kind, but it did perform well on Home Defence duties as an anti-Zeppelin aircraft. Until the enemy began to use the Gotha biplanes in place of his airships, the B.E.2C was the standard British Home Defence aeroplane. In this particular kind of work the machine’s stability was a real asset, for it simplified night-flying and made the aircraft a steady gun platform.

Five enemy airships fell to the guns of B.E.2c’s: the Schutte-Lanz S.L.11 and the Zeppelins L.32, L.31, L.34 and L.21. The wooden-framed Schutte-Lanz airship was shot down on September 3rd, 1916, by Lieutenant W. Leefe-Robinson of No. 39 Squadron, who received the Victoria Cross for this action. Exactly three weeks later, on September 24th, Second Lieutenant F. Sowrey, also of No. 39 Squadron, shot down the Zeppelin L.32 over Billericay; he was flying a Bristol-built B.E.2C, No. 4112.

The British and Colonial Aeroplane Co. built ten specially modified B.E.2c’s, numbered 4700-4709, for Home Defence duties. These were single-seaters, and the space normally occupied by the front seat contained an extra petrol tank to increase endurance for anti-Zeppelin work.

The Home Defence B.Es were armed in a variety of ways. Some carried canisters of Ranken darts, some relied on bombs, but the majority were armed with a Lewis gun firing incendiary ammunition. Experiments were also carried out with Le Prieur rockets: a B.E.2C which had an installation for ten rockets was No. 8407. At Farnborough tests were made with a B.E.2C which had two grapnels attached to cables. These were normally carried under the fuselage and may have been intended to be anti-airship weapons.

In 1915, a slightly modified version of the design, known as the B.E.2d, appeared. This variant had dual controls and a revised fuel system: there was an external gravity petrol tank under the port upper mainplane, an addition which provided the chief external distinguishing feature of the type. The sides of the forward cockpit were rather lower than on the B.E.2C. The B.E.2d began to come into service in the spring of 1916, but was no improvement on the B.E.2C.

<...>

The standard engine for the B.E.2c, 2d and 2e was the 90 h.p. R.A.F.1a, but several other types of engine were installed in some machines. The 105 h.p. R.A.F.1b became available in 1916 and was fitted to some B.Es; this engine had cylinders of larger bore. A few machines were fitted with the later R.A.F.1d, which had aluminium cylinders with deep fins and overhead inlet and exhaust valves. (The R.A.F.1a and 1b had cast-iron cylinders with side inlet valve and overhead exhaust valve. The R.A.F.1d was of considerable historical importance in view of the use of aluminium for its cylinders; it owed its existence to the experimental work of H. P. Boot and G. S. Wilkinson with aluminium cylinders at Farnborough.)

Some B.E.2c’s originally built for the R.F.C. were handed over to the R.N.A.S. without engines, and several were fitted with the 90 h.p. Curtiss OX-5. One of the contractors responsible for fitting the Curtiss engine was the firm of Frederick Sage & Co., Ltd. A few of the B.E.2e’s which were handed over to the R.N.A.S. for training purposes were fitted with the 75 h.p. Rolls-Royce Hawk engine.

The 150 h.p. Hispano-Suiza was fitted to several B.E.2c’s and 2e’s. One of the first installations in a B.E.2c was made unofficially at No. 1 Aircraft Depot at St. Omer early in 1916. At Farnborough, the Hispano was first fitted to the B.E.2c No. 2599; this machine had its radiators disposed in a peculiar manner along each cylinder block.

A more conventional radiator installation for the Hispano-Suiza was made by the Belgians when they modified several of their B.E.2c’s to have the 150 h.p. engine: a flat circular radiator was fitted in the nose. In an attempt further to improve their B.E.ac’s, the Belgians modified the control system and placed the pilot in the front cockpit. He was then provided with a synchronised Vickers gun, and a Nieuport-type ring-mounting was fitted over the rear cockpit for the observer’s Lewis gun. Unfortunately, the additional weight of the greatly improved armament had an adverse effect upon the aircraft’s performance, for its service ceiling was only 11,000 feet. The modifications were made under the direction of Lieutenant Armand Glibert of the 6th Belgian Squadron, but he was one of the first to lose his life on a Hispano-B.E. While on a reconnaissance flight far inside the German lines he and his observer, Lieutenant Callant, were attacked by enemy fighters. Unable to climb or manoeuvre adequately, their B.E.ac was shot down and both were killed.

Some of the R.F.C.’s B.E.2e’s were fitted with the 150 h.p. Hispano-Suiza, but were used only for training purposes.

The B.E.2c and 2e were used in many experiments throughout the war. One of the most startling was begun at Kingsnorth airship station in the summer of 1915. At that time much thought was devoted to the design of an anti-Zeppelin aircraft which, as one of its most desirable qualities, would have a very long flight endurance. Commander N. F. Usborne and Lieutenant-Commander de Courcy W. P. Ireland designed a remarkable composite aircraft which consisted of an S.S.-type airship envelope to which was attached a complete B.E.2C aeroplane. It was argued that the gas bag would keep the aeroplane aloft until a Zeppelin was sighted: by means of quick-release catches the airship envelope would be cast off, and the B.E.2C would attack in the normal way. The first tests of the Airship-plane, as it was called, were made by Flight Commander W. C. Hicks in August, 1915, but the controlling gear was not satisfactory. After modifications had been made, the first trial flight was made by Usborne and Ireland. It ended tragically. At about 4,000 feet the B.E. was seen to separate prematurely from the gas bag: some of the flight controls must have been damaged, for the machine turned over as it fell away, and Lieutenant-Commander Ireland was thrown out. The B.E. crashed out of control in the goods yard of Strood railway station, and Commander Usborne was killed.

In August, 1916, a B.E.2c was used to test the first installation of the Constantinesco synchronising gear for machine-guns. This was probably the B.E.2c’s greatest service to the R.F.C. and R.N.A.S., for the Constantinesco gear was a great improvement over existing types of interrupter or synchronising gear.

An equally great service to aviation in general was rendered by the B.E.2e in which Dr F. A. Lindemann (later Lord Cherwell) carried out his very gallant experiments to investigate the phenomenon of spinning, which was not then understood.

The spinning experiments were conducted at Farnborough, as were many others in which B.Es were fitted with various airscrews, engines, instruments and wings of different aerofoil sections. Wings of R.A.F. 14, 15, 17 and 18 section were tested, and one of the B.E.2e’s which were used was fitted with wings of 6 feet 1 inch chord.

Early in 1918, B.E.2c No. 4122 was fitted with the first R.A.F. variable-pitch airscrew. Operation of the airscrew was purely mechanical and the pilot’s control consisted of a handwheel. Each of the four blades of the airscrew was built up of walnut laminations and was fitted to a steel shank. The hub was a clumsy structure, and the complete airscrew weighed 85 lb: it was 50 lb heavier than the standard walnut airscrew. The total range of angular movement of the blades was 1 o degrees.

Some of the earliest British experiments with superchargers were conducted on B.Es. In these aircraft the engine was the R.A.F.1a, and the blower was fitted directly under the fuel tank. When the blower seized (as it frequently did), the resulting shower of sparks so near the petrol tank was somewhat disquieting for the observer.

The B.E.2C continued on active service until the last year of the war: in 1918, some were still working as anti-submarine patrol aircraft. The great majority of B.Es ended their days at various training units, however. In August, 1918, twelve B.E.2e’s were sold to the Americans, and were used as trainers in England.

Thus these unwilling warriors - for the B.E.2C was originally designed to be merely a stable aeroplane, not a fighting aircraft - ended their days in comparative peace. But they achieved a kind of immortality, for they were regarded as the embodiment of the Government-designed aeroplane, mass-produced by official order, yet inefficient, ineffective and inferior for all military purposes. To blame the B.Es themselves would be to misjudge them, for they were safe and reliable flying machines, lacking only the performance and manoeuvrability necessary to survive the ever-increasing intensity of aerial warfare. The fault lay with those who continued to order the B.Es and, worse still, to send them to war long after they were obsolete.

They were the Fokker Fodder of 1915-16; they were the prey of Albatros, Halberstadt, Roland and Pfalz in 1916-17; they were the reason for Noel Pemberton-Billing’s dramatic charges of criminal negligence against the Administration and higher Command of the R.F.C. In a speech in the House of Commons on March 21st, 1916, Pemberton-Billing said: “I would suggest that’quite a number of our gallant officers in the Royal Flying Corps have been rather murdered than killed.” The Judicial Committee which was set up to investigate these charges was unable to find any foundation in fact for them.

But the stigma remained and survives to this day, redeemed only by its implied, unrecorded quantum of courage - the courage of those who flew the B.Es to war.

SPECIFICATION

Contractors; Sir W. G. Armstrong, Whitworth & Co., Ltd., Gosforth, Newcastle-on-Tyne; The Austin Motor Co. (1914), Ltd., Northfield, Birmingham; Barclay, Curie & Co., Ltd., Whiteinch, Glasgow; William Beardmore & Co., Ltd., Dalmuir, Dumbartonshire; The Blackburn Aeroplane & Motor Co., Ltd., Olympia, Leeds; The British Caudron Co., Ltd., Broadway, Cricklewood, London, N.W.a; The British and Colonial Aeroplane Co., Ltd., Filton, Bristol; The Coventry Ordnance Works, Ltd., Coventry; The Daimler Co., Ltd., Coventry; William Denny & Bros., Dumbarton; The Eastbourne Aviation Co., Ltd., Eastbourne; The Grahame-White Aviation Co., Ltd., Hendon, London, N.W.; Handley Page, Ltd., 110 Cricklewood Lane, London, N.W.; Hewlett & Blondeau, Ltd., Clapham, London; Martinsyde, Ltd., Brooklands, Byfleet; Napier & Miller, Ltd., Old Kilpatrick; Ruston, Proctor & Co., Ltd., Lincoln; The Siddeley-Deasy Motor Car Co., Ltd., Park Side, Coventry; Vickers, Ltd. (Aviation Department), Imperial Court, Basil Street, Knightsbridge, London, S.W.; The Vulcan Motor & Engineering Co. (1906), Ltd., Crossens, Southport; G. & J. Weir, Ltd., Cathcart, Glasgow; Wolseley Motors, Ltd., Adderley Park, Birmingham. Australia: a few B.E.2c’s were built at the Australian Flying School, Point Cook.

Dimensions:

Aircraft B.E.2c B.E.2d B.E.2e Experimental B.E.2e with R.A.F. 18 wings

Span, upper 37 ft 36 ft 10 in. 40 ft 9 in. 40 ft 9 in.

Span, lower 37 ft 36 ft 10 in. 30 ft 6 in. 30 ft 6 in.

Length 27 ft 3 in. 27 ft 3 in. 27 ft 3 in. 27 ft 3 in.

Height 11 ft 1 1/2 in. 11 ft 12 ft 12 ft

Chord 5 ft 6 in. 5 ft 6 in. 5 ft 6 in. 6 ft 1 in.

Gap 6 ft 3-19 in. 6 ft 3 in. 6 ft 3 1/4 in. 6 ft 3 1/4 in.

Stagger 2 ft 2 ft 2 ft 2 ft

Dihedral 3° 30' 3° 30' 3° 30' 3° 30'

Incidence:

R.A.F. 6 3° 30' - - -

R.A.F. 14 4° 09' 4° 09' 4° 15' -

Span of tail 15 ft 6 in. 15 ft 6 in. 14 ft 14 ft

Wheel track 5 ft 9 3/4 in. 5 ft 9 3/4 in. 5 ft 9 3/4 in. 5 ft 9 3/4 in.

Airscrew diameter:

R.A.F.1a 9 ft 1 in. 9 ft 1 in. 9 ft 1 in. 9 ft 1 in.

Hispano-Suiza 8 ft 7 in. - - -

Areas (sq. ft) :

Wings 371 371 360 399

Tailplane 36 36 24 24

Elevator 27 27 22 22

Fin 4 4 8 8

Rudder 12 12 15 15

Power: B.E.2C: 70 h.p. Renault; 90 h.p. R.A.F. 1a; 105 h.p. R.A.F. 1b; 105 h.p. R.A.F. 1d; 90 h.p. Curtiss OX-5; 150 h.p. Hispano-Suiza. B.E.2d: 90 h.p. R.A.F. 1a. B.E.2e: 90 h.p. R.A.F. 1a; 105 h.p. R.A.F. 1b; 150 h.p. Hispano-Suiza; 75 h.p. Rolls-Royce Hawk.

Tankage: B.E.2C, R.A.F. la engine: petrol, main pressure tank, 18 gallons; auxiliary gravity tank, 14 3/4 gallons; total 32 3/4 gallons. Oil: 3 gallons. B.E.2C, 150 h.p. Hispano-Suiza: petrol, 23 gallons. Oil: 3 gallons. Water: 9 gallons. B.E.2d and B.E.2e: petrol, main gravity tank, 19 gallons; auxiliary gravity tank, 10 gallons; service gravity tank, 12 gallons; total 41 gallons. Oil: 4I gallons.

Armament: Defensive armament ranged from nil to four Lewis machine-guns, by way of various assortments of rifles and pistols. Usually a single’ Lewis gun was carried, for which four sockets were provided about the front cockpit: one on either side, one in front and one behind. The gun had to be lifted manually from one socket to another.

A fixed Lewis gun could be fitted on a Strange-type mounting on the starboard side; the gun fired obliquely outwards and forwards to clear the airscrew. A few B.Es had a Lewis gun mounted behind the pilot’s cockpit for rearwards firing.

Some of the Belgian B.E.2c’s with the 150 h.p. Hispano-Suiza engine had a fixed, synchronised Vickers machine-gun for the pilot and a Lewis gun on a Nieuport-type ring-mounting on the rear cockpit.

Some Home Defence B.Es had a Lewis gun or pair of Lewis guns firing upwards behind the centresection: others carried twenty-four Ranken darts plus two 20-lb high explosive bombs plus two 16-lb incendiary bombs. Ten Le Prieur rockets could also be carried.

Some R.N.A.S. B.E.2c’s had a Lewis gun on an elevated bracket immediately in front of the pilot’s cockpit: the gun fired under the centre-section but over the airscrew.

Bombs were carried in racks under the fuselage and under the inner bays of the lower wings. The bomb-load of the Renault-powered B.E.2C consisted of three or four small bombs of 20 or 25 lb. When flown solo, the R.A.F.-powered B.E.2C could take two 112-lb bombs, one 112-lb and four 20-lb bombs, or ten 20-lb bombs. The pilots of the bomber B.Es usually carried a rifle as a defensive weapon.

Service Use:

B.E.2C. Western Front: R.F.C. Squadrons Nos. 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 15, 16 and 21; R.N.A.S., Dunkerque; No. 1 Wing, R.N.A.S.; 6th Squadron, Belgian Flying Corps, both R.A.F. 1a and Hispano-Suiza versions. Home Defence: H.D. Detachments of No. .19 Reserve Squadron, consisting of two machines at each of the following aerodromes: Hounslow, Wimbledon Common, Croydon, Farningham, Joyce Green, Hainault Farm, Suttons Farm, Chingford, Hendon and Northolt. These detachments became No. 39 Squadron on April 15th, 1916. Two B.E.2c’s at Brooklands, two at Farnborough, three at Cramlington. Three machines each to training squadrons at Norwich, Thetford, Doncaster and Dover. Squadrons Nos. 33, 39, 50, 51, 75, 141 and No. 5 Reserve Squadron. R.N.A.S., Great Yarmouth (and landing grounds at Bacton, Holt, Burgh Castle, Covehithe and Sedgeford), Redcar, Hornsea, Scarborough, Eastchurch, Port Victoria. South-West Africa: South African Aviation Corps Unit. East Africa: No. 7 Squadron, R.N.A.S.; No. 26 Squadron, R.F.C. Egypt: R.F.C. Squadrons Nos. 14 and 17. Palestine: R.F.C. Squadrons Nos. 14 and 67 (Australian). Mesopotamia: No. 30 Squadron, R.F.C. Macedonia: No. 17 Squadron, R.F.C. India: R.F.C. Squadrons Nos. 31 and 114. Eastern Mediterranean: No. 2 Wing, R.N.A.S., Imbros and Mudros; No. 3 Wing, R.N.A.S., Tenedos and Imbros. Training: used at various training units; e.g., Netheravon; No. 11 Reserve Squadron, Northolt; No. 20 Training Squadron, Wye; No. 26 Training Squadron, Blandford; No. 35 Reserve Squadron, Filton (later Northolt); No. 39 Training Squadron, Narborough; No. 44 Training Squadron, Waddington; No. 51 Squadron, Marham; No. 63 Squadron, Stirling; W/T Telegraphists School, Chattis Hill; School of Photography, Map Reading and Reconnaissance, Farnborough; Air Observers’ Schools at New Romney, Manston and Eastchurch; School of R.A.F. and Army Cooperation, Worthy Down; R.N.A.S. Cranwell; Belgian Flying School, Etampes; Australian Flying School, Point Cook.

B.E.2d. Western Front: R.F.C. Squadrons Nos. 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12. 13, 15, 16, 42, H.Q. Communication Squadron. Training: No. 63 Squadron, and mainly as for B.E.2C.

B.E.2e. Western Front: R.F.C. Squadrons Nos. 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 15, 16, 21, 34, 42, 52, 53, 100, Special Duty Flight of 9th (H.Q.) Wing, H.Q. Communication Squadron. Eastern Front: used by Russian Flying Corps. Home Defence: obviously distributed on a similar scale to the B.E.2C; Squadrons Nos. 51, 78 and 141 are known to have used the type. Palestine: Squadrons Nos. 14, 67 (Australian), 113, 142; “B” Flight at Weli Sheikh Nuran, formed from No. 23 Training Squadron; “X” Flight at Aqaba. Mesopotamia: No. 30 Squadron. Macedonia: No. 47 Squadron. India: Squadrons Nos. 31 and 114. Training: No. 1 Training Depot Squadron, Stamford; Training Squadrons Nos. 26, 31 and 44; No. 39 Reserve Squadron, Northolt; Chattis Hill, Farnborough, New Romney, Manston, Eastchurch and Worthy Down as detailed for B.E.2C; Advanced Air Firing School, Lympne; R.N.A.S., Cranwell; twelve used by the Americans at Ford Junction; Australian Flying School, Point Cook.�

Weights (lb} and Performance:

Aircraft B.E.2C B.E.2C B.E.2C Armoured B.E.2C B.E.2d B.E.2d B.E.2e B.E.2e

Engine Renault R.A.F.1a Hispano-Suiza R.A.F.1a R.A.F.1a R.A.F.1a R.A.F.1a R.A.F.1b

No. of Trial Report - - - - M.30 M.106 M.20 -

Date of Trial Report - April, 1916 - May, 1916 June, 1917 May 10th, 1916 -

Type of airscrew used on trial - - - - T.7448 - T.7448 -

Weight empty - 1,370 1,750 - 1,375 - 1,431 -

Military load - 160 80 - 80 Nil 70 90

Crew - 360 320 - 320 360 360 360

Fuel and oil - 252 200 - 345 - 239 -

Weight loaded - 2,142 2,350 2,374 2,120 1,950 2,100 2,119

Maximum speed (m.p.h.) at

ground level 75 - 949 85-5 88-5 - 90 94

6,500 ft - 72 91 - 75 89-5 82 -

8,000 ft - - - - 73 - 77-3 -

10,000 ft - 69 86 - 71 83 75 -

m. s. m. s. m. s. m. s. m. s. m. s. m. s. m. s.

Climb to

1,000 ft - - - - 3 00 - 1 36 -

2,000 ft - - - - 7 55 - - -

3,000 ft - - 5 40 - 12 15 - - -

3.500 ft - 6 30 - 10 00 - - - -

4,000 ft - - - - 18 00 - - -

5,000 ft - - - - 24 00 - - -

6,000 ft - - 11 50 - 31 15 - 20 30 12 20

6,500 ft - 20 00 - - 36 00 17 35 - -

7,000 ft - - - - 40 15 - - -

8,000 ft - - - - 52 30 - 32 40 19 20

9,000 ft - - - - 65 10 - - -

10,000 ft - 45 15 26 05 - 82 50 33 40 53 00 26 30

11,000 ft - - - - - - 71 00 -

12,000 ft - - 37 10 - - - 80 00 -

Service ceiling (feet) - 10,000 12,500 - 7,000 12,000 9,000 -

Endurance (hours) - 3 1/4 2 - 5 1/2 - - 3 1/2

Serial Numbers:

Serial No. Type Contractor For delivery to:

952-963 B.E.2C Vickers Admiralty, but transferred to R.F.C.

964-975 B.E.2C Blackburn Admiralty

976-987 B.E.2C Hewlett & Blondeau Admiralty

988-999 B.E.2C Martinsyde Admiralty

1075-1098 B.E.2C Vickers Admiralty

1099-1122 B.E.2C Beardmore Admiralty

1123-1146 B.E.2C Blackburn Admiralty

1147-1170 B.E.2C Grahame-White Admiralty

1183-1188 B.E.2C Eastbourne Admiralty

1189-1194 B.E.2C Hewlett & Blondeau Admiralty

1652-1697 B.E.2C British & Colonial; Contract No. A.2554.A(MA 3) War Office

1698-1747 B.E.2C British & Colonial; Contract No. A.2763 War Office

Between and about B.E.2C War Office

1748 and 1799

Between and about B.E.2C Probably Daimler War Office

2015 and 2092

2470-2569 B.E.2C Wolseley War Office

2570-2669 B.E.2C - War Office

2670-2769 B.E.2C Ruston, Proctor War Office

3999 B.E.2C Blackburn Admiralty

4070-4219 B.E.2C British & Colonial; Contract No. A.3243 War Office

4300-4599 B.E.2C and 2e G. & J. Weir War Office, some transfers to Admiralty War Office

4700-4709 B.E.2C (single-seat) British & Colonial; Contract No. 94/A/14 War Office

4710 B.E.2C - War Office

About 5235 B.E.2C - War Office

Between and about B.E.2C - War Office

5384 and 5445

5730-5879 B.E.2d British & Colonial; Contract No. 87/A/115 War Office

6228-6327 B.E.2d and 2e Ruston, Proctor; Contract No. 87/A/179 War Office, some transfers to R.N.A.S. War Office

6728-6827 B.E.2d and 2e Vulcan War Office

7058-7257 B.E.2d and 2e British & Colonial; Contract No. 87/A/115 War Office

8293-8304 B.E.2C Grahame-White Admiralty

8326-8337 B.E.2C Beardmore Admiralty

8404-8433 B.E.2C Eastbourne Admiralty

8488-8500 B.E.2C Beardmore Admiralty

8606-8629 B.E.2C Blackburn; Contract No. C.P.60949/15 Admiralty

9456-9475 B.E.2C and 2e* - Admiralty

9951-10000 B.E.2C Blackburn Admiralty

A.1261-A.1310 B.E.2C and 2e Barclay, Curie War Office

A.1311-A.1360 B.E.2C and 2e Napier & Miller War Office

A.1361-A.1410 B.E.2C and 2e Denny War Office

A.1792-A.1891 B.E.2C and 2e Vulcan War Office, some transfers to R.N.A.S. War Office

A.2733-A.2982 B.E.2e British & Colonial; Contract No. 87/A/51 War Office

A.3049-A.3148 B.E.2e Wolseley War Office

A.3149-A.3168 B.E.2e - War Office

A.8626-A.8725 B.E.2e British & Colonial; Contract No. 87/A/571 War Office

B.719, 13.723, B.728, B.790 B.E.2e No. 1 (Southern) Aeroplane Repair Depot Rebuilds for R.F.G.

B.3651-B.3750 B.E.2e Vulcan War Office

B.4401-B.4600 B.E.2e British & Colonial; Contract No. 87/A/571 War Office

B.6151-B.6200 B.E.2e British Caudron War Office

C.1701-C.1750 B.E.2e British & Colonial; contract cancelled War Office

C.6901-C.7000 B.E.2e Denny War Office

C.7001-C.7100 B.E.2e Barclay Curie War Office

C.7101-C.7200 B.E.2e Napier & Miller War Office

Between and about

F.4096 and F.4160 (probable batch F.4071-F.4170) B.E.2e - War Office

N.5770-N.5794 B.E.2c Allocated for B.E.2c’s with 150 h.p. Hispano-Suiza engines, but contract cancelled Admiralty

* 9459-9461 were B.E.2e’s transferred from R.F.G. They were originally numbered A. 1829, A. 1833 and A. 1835 respectively.

Production and Allocation: Official statistics group the B.E.2a, 2b, 2c and 2d together, and show that a total of 1,793 B.Es of these four sub-types were built. Deliveries to the R.F.G. only and R.A.F. were as follows (these figures exclude deliveries to the R.N.A.S.):

Type Expeditionary Force Middle East Brigade Training

Units Home Defence Total

B.E.2C 487 200 294 136 1,117

B.E.2d 136 - 54 1 191

B.E.2e 503 225 9’3 160 1,801

On October 31st, 1918, only 474 B.E.2c’s, 2d’s and 2e’s remained on charge with the R.A.F. Of these, one was with the Expeditionary Force in France; sixty-seven were in Egypt and Palestine; six were at Salonika; six were in Mesopotamia; fifty-eight were on the North-West Frontier of India; four were in the Mediterranean area; and seven were en route to the Middle East. At home, three were at Aeroplane Repair Depots; ten were in store; twenty-one were with Home Defence units; six were with Coastal Patrol units; two were at Aircraft Acceptance Parks; four were in Ireland with the 1 ith Group; and 279 were at schools and various other aerodromes.

Notes on Individual Machines: Used by No. 13 Squadron, R.F.G.: 2017, 2043, 2045, 4079, 4084, 5841 (Manfred von Richthofen’s 32nd victory, April 2nd, 1917). Used by No. 30 Squadron, R.F.G.: 2690, 4141, 4183, 4191, 4194, 4398, 4414, 4486, 4500, 4562, 4573, 4584, 4594. Used at Great Yarmouth Air Station, R.N.A.S.: 977, 1151 (transferred to Chingford), 1155 (transferred to Chingford), 1160 (transferred to Chingford), 1194 (transferred to Eastbourne), 8326, 8417, 8418, 8419, 8492, 8614. Used at No. 1 School of Navigation and Bomb Dropping, Stonehenge: B.4498, B.6155, B.8896, B.8899, C.6939, C.7103, C.7127, C.7131, C.7137. Used by No. 1 Training Depot Squadron, Stamford: A.2946, B.6164, B.8828, C.7055, C.7141, C.7151. Other B.Es: 968 and 969: transferred to South African Aviation Corps; left U.K. on April 3rd, 1915. 980: went to France September 20th, 1915. 1109: R.N.A.S., Redcar. 1127: did not go into British service; was sent to Belgium in exchange for a Farman biplane, which was given the serial number 1127 on arrival in Britain. 1145: R.N.A.S., Redcar. 1675: interned in Holland, 1915. 1688: used in tests of R.A.F. Low Altitude Bomb Sight. 1697: became B.E. 12 prototype. 1700: became B.E.9. 1738: transferred to R.N.A.S.; fitted with 90 h.p. Curtiss engine. 1793: R.A.F. ib engine; was used to test effect of weather on performance, summer, 1916. 2015: experimental installation of multiple pitot tubes on mounting in front of fin. 2037: No. 16 Squadron. 2599: 150 h.p. Hispano-Suiza engine. 2735: transferred to R.N.A.S. 2737: transferred to R.N.A.S.; used by “D” Flight, Cranwell. 3999: W/T experimental machine for Admiralty. 4120: tested with R.A.F. 19-section wings, June, 1916; survived until 1921.4122: fitted with R.A.F. variable-pitch airscrew. 4199: No. 20 Training Squadron, Wye. 4205: armoured B.E.2C. 4312: B.E.2e of No. 67 (Australian) Squadron. 4336 and 4337: transferred to R.N.A.S.; fitted with 90 h.p. Curtiss OX-5. 4362: No. 3 Squadron. 4423: transferred to R.N.A.S.; fitted with 90 h.p. Curtiss OX-5. 4426: transferred to R.N.A.S.; used by “D” Flight, Cranwell. 4524, 4525 and 4526: transferred to R.N.A.S. 6232: B.E.2d; Manfred von Richthofen’s 26th victory, March nth, 1917. 6246: B.E.2d, No. 63 Squadron. 6324: B.E.2e; transferred to R.N.A.S., Cranwell; fitted with 75 h.p. Rolls-Royce Hawk engine. 6325 and 6326: transferred to R.N.A.S.; used by “D” Flight, Cranwell. 6327: transferred to R.N.A.S., Cranwell; fitted with Rolls-Royce Hawk. 6742: B.E.2e, No. 16 Squadron; Manfred von Richthofen’s 19th victory, February 1st, 1917. 8423: R.N.A.S., Cranwell, “D” Flight. 8424: No. 7 (Naval) Squadron; later to No. 26 Squadron, R.F.C., German East Africa. 8623: R.N.A.S., Cranwell, “D” Flight. 9456-9458, 9462-9469 and 9471-9475 all had the 90 h.p. Curtiss OX-5 engine. A. 1350: B.E.2e, No. 44 Flying Training Squadron. A. 1829, A. 1833 and A. 1835: B.E.2e’s transferred to R.N.A.S. without engines. A.2815: No. 16 Squadron; Manfred von Richthofen’s 39th victory, April 8th, 1917. A.2884: “Susanne”, No. 31 Training Squadron, Wyton. A.8694-A.8699: B.E.2e’s transferred to R.N.A.S. without engines. B.723: No. 141 Squadron. B.3655: “Remnant”, A.A.F.S., Lympne. C.6986: flown in Australia by Queensland and Northern Territory Aerial Service Co., Ltd., in 1921. C.7086: No. 2 Squadron. C.7095: used by Americans at Ford Junction. C.7133: No. 31 Training Squadron, Wyton.

Costs:

B.E.2C and 2e airframe, without engine, instruments and guns £1,072 10s.

R.A.F.1a engine £522 10s.

70 h.p. Renault £522 10s.

Curtiss OX-5 £693 10s.

Rolls-Royce Hawk £896 10s.

B.E.10