А.Шепс Самолеты Первой мировой войны. Страны Антанты

Этой машине практически не пришлось принимать участие в боевых действиях, так как их поступление в дивизионы "Индепендент Эйр Форс" совпало с окончанием войны. Однако необходимо отметить конструктивные особенности машины, предназначавшейся для решения стратегических задач. Самолет создавался для нанесения бомбового удара по Берлину и другим важным объектам на территории Германии.

Создание подобной машины подстегнули участившиеся налеты германских бомбардировщиков "Гота", "Фридрихсгафен" и "Штаакен" на Лондон и другие города южной Англии.

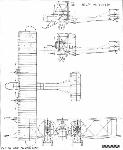

Это был четырехместный двухмоторный биплан. Фюзеляж коробчатого прямоугольного сечения представлял собой деревянный каркас из стрингеров и шпангоутов, имел в носовой части обшивку из фанеры, а в задней части полотняную. Съемный гаргрот за кабиной пилота имел полотняную обшивку по реечному каркасу и крепился к фюзеляжу стальными лентами. В носовой части устанавливалась турельная установка и бомбовый прицел, причем впервые кабина бомбардира имела остекление. За ней располагалась кабина пилотов с двойным управлением, а затем, по задней кромке крыла, хвостовая турельная установка. Далее в нижней части фюзеляжа устанавливалась кинжальная пулеметная установка для обстрела нижней задней полусферы. Вооружение обеспечивало довольно надежную значительную защиту от истребителей противника.

Крыло двухлонжеронное. Нервюры имели ферменную конструкцию и усиление в местах крепления стоек. Элероны устанавливались на верхнем и нижнем крыле и имели деревянный каркас. Вся конструкция обшивалась полотном и покрывалась аэролаком. Оперение представляло из себя двухстоечную бипланную коробку с двумя рулевыми поверхностями. Конструкция была аналогична конструкции крыла. Стойки крыла и оперения имели трубчатую конструкцию и обтекатели из дерева. Над нижним крылом между стойками в шестигранных мотогондолах устанавливались два двигателя Роллс-Ройс "Игл-VIII" мощностью по 360 л. с. Это были 12-цилиндровые V-образные двигатели жидкостного охлаждения с лобовыми радиаторами, оборудованными регулирующими жалюзи. В мотогондоле располагались топливные баки и маслобак. Каждые шесть цилиндров имели отдельный выходной патрубок. Шасси имело жесткую конструкцию из металлических труб и четыре главных колеса, оборудованных шнуровой резиновой амортизацией. Под носовой частью устанавливалась противокапотажная лыжа, а в хвостовой части - костыль. Вооружение состояло из трех-пяти пулеметов 7,62-мм "Льюис" с комплектом до 500 патронов на ствол. Самолет мог нести более 1 т бомб на внешней подвеске под фюзеляжем и центропланом. Стандартная бомбовая нагрузка - 4 бомбы по 115 кг и 8 бомб по 56 кг.

Модификации

"Вими" Mk I - первая серия машин с двигателями Роллс-Ройс "Игл-VIII" (360л. с.).

"Вими" Mk II - развитие серии Mk I, отличался более мощными двигателями Роллс-Ройс "Игл" (400 л. с.) с носовым колесом вместо противокапотажной лыжи. На вертикальном оперении появились два киля.

"Вими-Парашют-тренер" - машина на базе переделанного Mk I, оборудованная для обучения пилотов пользованию парашютом, было снято вооружение и установлена специальная лестница.

"Вими-Трансатлантик" - машина, оборудованная для перелета через Атлантику. Максимально облегченная, с закрытой кабиной и дополнительными топливными баками.

"Вими-Коммершл" - грузопассажирский самолет на базе Мк II с круглым фюзеляжем монококовой конструкции и уширенного сечения, оборудован пассажирской кабиной с окнами и дверью в левом борту.

"Вими" так и не совершил ни одного налета на Берлин, но свою известность он получил благодаря двум знаменитым перелетам, совершенным на нем.

14-15 июля 1919 года два пилота RAF капитан Джон Алкок и лейтенант Артур Виттен Браун совершили впервые перелет из Сент-Джона на о. Ньюфаундленд через Атлантический океан в Ирландию, совершив посадку у городка Клифден. В октябре-ноябре этого же года братья Росс и Кейт Смитт совершили многоэтапный перелет из Великобритании в Австралию, пролетев за 135 летных часов 18250 км со средней скоростью 120,7 км/ч.

F.B.27 "Вими" Mk I "Вими-Трансатлантик"

Размеры, м:

длина 13,27

размах крыльев 20,73

высота 4,76

Площадь крыла, м2 122,4

Вес, кг:

максимальный взлетный 5670 5445

пустого 3230 3230

Двигатель: Роллс-Ройс "Игл VIII"

число х мощность, л. с. 2x360

Скорость, км/ч 165 165

Дальность полета, км 1150 1450

Потолок практический, м 2315 3200

Экипаж, чел. 3-5 2

Вооружение 3-5 пулеметов -

1123 кг бомб

Показать полностью

C.Andrews Vickers Aircraft since 1908 (Putnam)

The Vimy

The E.F.B.8, which appeared in November 1915, powered by two Gnome monosoupapes, was smaller than its predecessor and carried only a single light Lewis gun, which could be accommodated equally well in single-engined types. This redesign was entrusted to Pierson, who stored the knowledge gained and revived it when a new twin-engined bomber was called for from Vickers by the Air Board in 1917, in the following circumstances.

Capt Peter D. Acland, at the time assistant manager in the Aviation Department of Vickers, gave the following account, in 1944, of the inception of the Vimy:

'The initiation of the design of the Vimy by Rex Pierson was the result of a conversation I had with Alec Ogilvie (Holding a position corresponding later to the Director of Technical Development) at the old Hotel Cecil in July 1917. At the time a large number of Hispano engines was surplus to fighter requirements for which they (the Air Board) were seeking a use. At that same time they were not getting sufficient Rolls-Royce Eagles to fulfil all their bombing requirements, and it was suggested to me that Vickers should attempt to build a bomber around the Hispano engine to the same specification as the Handley Page O/400.

'Pierson rapidly produced general layout designs, and an immediate order for prototypes was given. The first of these was flown by Gordon Bell at Joyce Green on 30 November, 1917. There was a different type of engine fitted into each of the other prototypes, including B.H.P., Fiat, Salmson and, subsequently, the Rolls-Royce Eagle.

'When the time came to place the production orders in April 1918, the Rolls was decided upon. History tells us the rest. The designing, building and flying of the machine in a period of four months was, to my mind, one of the highest spots of co-operative effort I have come across in many years in the industry.'

Pierson had related this story in a broadcast talk in 1942, when he said that with Maj J. C. Buchanan of the Air Board (later Air Ministry) he drew up the outline of the proposed Vickers bomber on a piece of foolscap paper in the Hotel Cecil, the Board's headquarters.

The four F.B.27 prototypes were fitted with 200 hp geared Hispano Suizas (later re-engined with 260 hp Salmsons), 260 hp Sunbeam Maoris, 300 hp Fiat A-12 and 360 hp Rolls-Royce Eagle VIIIs. These prototypes were conveniently referred to as Marks I to IV, but surviving Weybridge drawings do not confirm this early nomenclature, and official evidence on the subject seems to be conflicting. The Mark number system was never received with much enthusiasm on the production side until recent history, when it came to mean a lot more than merely airframe or engine modifications.

In the first F.B.27, called Vimy when the official naming of aircraft was introduced in 1918, the Hispanos were changed to Salmsons; the second, with Maoris, was lost soon after trials began because of engine failure; and the third, with the Fiats, also was lost by stalling on take-off at Martlesham and blowing up in the resulting crash as its bombs were armed (presumably for live practice over the nearby Orfordness armament and bombing ranges). The fourth Vimy prototype, with Eagles, went to Martlesham on 11 October, 1918, and confirmed the impression of exceptional performance for the period earned by the original F.B.27 in the previous January, also under test at Martlesham, the then newly established Aeroplane Experimental Establishment (Later renamed Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment).

The original Vimy, with its geared Hispanos of dubious reliability, had lifted a greater load than the much larger and more powerful Handley Page O/400. The Eagle-powered Vimy prototype had a speed of 100 mph and endurance of 11 hours with full crew and a load of nearly 5,000 lb (including fuel) out of a take-off weight of 12,500 lb, a remarkable achievement in its day.

Behind the scenes in official quarters a controversy had raged between the protagonists of tactical and strategic bombing. This seems to have been resolved because of the need to retaliate against the night bombing of targets in Britain by German aeroplanes, which began in September 1917. In consequence, the Vimy was one of the new heavy bombers selected for production. The first contract, for 150, received by Vickers was on 26 March, 1918, and was followed shortly afterwards by another for 200, the first batch to be made at Vickers' Crayford works and the second at Weybridge. With contracts to other firms, the order book reached 1,130, with variations as to the specified power units. Production during 1918 was to be reserved for aircraft for anti-submarine duties (carrying two torpedoes) and subsequent deliveries for night-bombing aircraft.

The urgency of combating the U-boat menace with a more devastating weapon than the Blackburn Kangaroo, then operating, probably dictated the priority for anti-submarine work, but no Vimy was in fact ever used in that role.

In October 1918 one Vimy bomber was flown to Nancy, in northeast France, to stand by for a series of long-range raids deep into Germany, including Berlin. The Armistice of 11 November, 1918, cancelled this plan, and consequently the Vimy was not used operationally in the first world war.

Following the cessation of hostilities, the Government drastically reduced all orders for military aircraft, including those for Vimys, after Crayford had made seven and Weybridge six, but subsequently Weybridge made 99 Vimys for the peacetime Royal Air Force. Components already completed were purchased from certain of the former outside contractors, which aided production, and special aircraft were modified from the military versions to undertake long-distance pioneering flights. Indeed, the first aeroplane to make a trans-oceanic flight non-stop was the now famous Vimy crewed by Capt Jack Alcock (Among his colleagues in the pioneering days of pre-1914 Brooklands, Alcock was known as 'Jack') and Lt Arthur Whitten-Brown on 14-15 June, 1919, across the Atlantic.

The production Vimy followed the conventional design trends of its time, having a wire-braced biplane wing structure and stabiliser, also of biplane form, with twin fins and rudders. The front fuselage was of steel tube and the rear fuselage was of wood with steel end-fittings and swaged tie-rod bracing. The rear longerons were hollow spars to the McGruer patent, devised by a Clyde yacht designer and consisting of wrapped shims machined circumferentially from spruce logs. Recently examined by the inventor, the longerons on the transatlantic Vimy now in the Science Museum in London were found to be in perfect condition. Rudders and ailerons were aerodynamically balanced by extensions forward of the hinge points. The whole design was well proportioned, and upon this factor depended its success. Its Rolls-Royce engines were admirably suited to it, which was a new experience as far as Vickers were concerned, for their designers had suffered miserably from the allocation of unsuitable engines for previous aircraft, as has already been emphasised.

The use of Vickers' own wind tunnel at St Albans, the first commercially owned example anywhere, helped considerably in predicting aerodynamic performance and configuration, and Pierson cleverly exploited the reduction in scale from contemporary designs (as represented by the Handley Page O/400) to reduce structure weight. He also introduced refinements in detail design to achieve maximum strength factors.

Provision was made in the fuselage for part of the bomb load, the rest being carried under the bottom planes, with simple release gear. Two gunners could be carried, one in the nose with a Lewis on a Scarff ring, another similarly armed aft of the wings, with provision for shifting the gun to a pivot mount on the bottom of the fuselage for firing aft under the tail, with side windows for light when changing ammunition drums.

Maximum range was 1,880 miles, and the Vimy was easily capable of carrying what was for its time quite a respectable bomb load to Berlin. Various figures of speed have been quoted, from 98 mph to the 112 mph which Capt Broome, a Vickers pilot, was able to record on one test flight. Climb to 6,000 ft took 18 minutes, and the Vimy's ceiling, when fully loaded, was not more than 12,000 ft. Within this performance envelope, Alcock and Brown had to fly through the weather across the Atlantic. This led them into icing troubles and flying attitudes of the most unfamiliar character, in weather conditions which today's high-flying airliners can usually avoid.

The Ross and Keith Smith brothers' flight to Australia at the end of 1919 in a specially prepared Vimy proved the soundness of the design from another angle. It showed that the aeroplanes of the time could be operated across continents to far distant places and foreshadowed the day when scheduled services would be operated between Europe, the Far East and Australia, just as Alcock and Brown had presaged regular Atlantic air routes. The attempts to reach Cape Town by air by the Vimy of Van Ryneveld and Quintin Brand, and the other, sponsored by The Times and flown by Vickers' test pilots, Cockerell and Broome, did not experience complete success. But a far-reaching discovery had been made. Technical progress was needed to overcome the combined effect of high operating temperatures and greater altitudes on engine behaviour and performance, and on improvements in airframes, for wood and fabric and tropical conditions did not agree with one another.

Although the three pioneering flights undertaken by Vimys soon after the first world war have been fully documented, including a book (The Flight of Alcock and Brown, Graham Wallace (Putnam)) on Alcock and Brown's Atlantic conquest, the essential details are included here to keep the record complete.

For the Atlantic flight all the military equipment was removed from a standard Vimy (The 13th airframe off the post-war production line at Weybridge) and extra tankage installed in its place, thus increasing the fuel capacity from 516 to 865 gallons to give an optimum range of 2,440 miles. Actually, enough fuel for another 800 miles remained in the tanks after the flight had terminated in the Derrygimla bog at Clifden, County Galway, for the prevailing westerly wind had been of some assistance, as is normal in scheduled operations today. The engines were the standard Rolls-Royce Eagle VIIIs of 360 hp each, and they functioned reliably except for an occasional icing-up of the air intakes. In the twin-engined configuration it was possible for the crew to see the radiators and air intakes; with a single-engined tractor aeroplane this was not possible, and one theory now advanced for the failure of Hawker to complete the Atlantic flight on the Sopwith single-engined tractor machine was that his radiator shutters were partially closed through a control maladjustment, thus causing the engine temperature to rise. Had he been able to see his engine, this would not have occurred, and some weight is lent to this conjecture by the fact that the Sopwith also had the Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII engine, the type which did so well in the Vimy.

From take-off near St John's, Newfoundland, to landing in Ireland, the Vimy took 16 hr 27 min on the 1,890 mile non-stop flight, which included the night of 14 June. Visibility was too poor most of the time for the navigator to take sights and the weather anything but good for such an adventure virtually into the unknown. Their objective was Galway Bay, the conditions of the Daily Mail ?10,000 prize having specified 'anywhere in the British Isles' as the terminating point. Whitten-Brown, with his improved nautical methods of navigation, devised while he was a prisoner of war, crossed the Irish coast at Clifden, only a few miles north of his flight plan.

The Vimy was partially wrecked on landing in the bog; had the two airmen but known, the green pasture next to the one they had selected was quite solid, according to eye-witnesses at the time. The omission of the nosewheel in Newfoundland to reduce drag and weight was probably a sound idea, but that wheel might have saved the aircraft from nosing into the bog. The Vimy was rebuilt at Weybridge after recovery, and now is a treasured exhibit in the Science Museum in London, where one can engage in an interesting exercise in comparing it with modern aircraft, particularly with regard to its primitive navigational aids, and to its structure, now partially exposed to public view.

The next major event which was to concern the Vimy was the offer of a prize of ?A10,000 by the Australian Government for the first flight by Australians from Britain to Australia, to be completed within 30 days and before the end of the year 1919. Maxwell-Muller had engineered the Vimy at Weybridge for the Atlantic flight and prepared another for this fresh challenge. It was more or less of the standard military type with few changes apart from the provision of additional stores, to cope with tropical flying, in place of the normal military load.

The pilots chosen were the Smith brothers, Ross and Keith, of the Australian Air Force, as were the two mechanics, Sgts W. H. Shiers and J. M. Bennett. A considerable amount of pre-flight planning had to be done, petrol, oil and essential stores laid down at strategic points en route, and landing grounds carefully surveyed by agents in advance.

As far as Calcutta the air route was fairly well known, but eastwards from there the flight took on the form of trail blazing. The Vimy, valiantly flown and serviced by its Australian crew, won through, like Sir Francis Drake, 'after many vicissitudes', including vile weather, and reached Darwin from Hounslow in just under 28 days on 10 December, 1919, having covered 11,130 miles in 135 hr 55 min elapsed flying time. The aeroplane, G-EAOU, is now preserved in a memorial hall on the airport at Adelaide, home of the pilots, for the building of which the Australian public subscribed some ?A30,000.

The third great flight attempted by the Vimy was for a flight from England to Cape Town. Several efforts were made, but two Vimys achieved the greatest success. One was a standard military type, called the Silver Queen, flown by Lt-Col Pierre Van Ryneveld and Maj C. J. Quintin Brand of the South African Air Force. They left Brooklands on 4 February, 1920, but crashed at Korosko between Cairo and Khartoum a week later, a mishap caused by a leaking radiator. A second Vimy was loaned by the Royal Air Force in Egypt and named Silver Queen II. This one reached Bulawayo in Southern Rhodesia. There it failed to lift off from the high-altitude aerodrome in high temperature with a failing engine, caused by dirty oil, and was put out of action. The crew borrowed a D.H.9, completed the flight to Cape Town and were awarded ?5,000 each by the South African Government. They were knighted by King George V, as were the Smith brothers and Alcock and Brown, after their respective efforts.

Height and heat also defeated the other attempt by a Vimy, chartered from Vickers by The Times, with Dr Chalmers Mitchell as their Press representative on the flight. The aeroplane was the prototype Vimy Commercial G-EAAV (originally K-107). It left Brooklands on 24 January, 1920, and crashed at Tabora, Tanganyika, on 27 February, failing to takeoff in tropical conditions. It was found that the water in the cooling system of one of the engines was contaminated. It was clear that further engine and airframe development would be needed to operate in such conditions if the lessons of these African flights were to be fully applied. Judging from the successful use of the Vimy and its family successors in Egypt, the Middle East and India in later years, it seems clear that these troubles in African flying were taken to heart.

No. 58 Squadron RAF, in Egypt in July 1919, was the first to receive the Vimy bomber, as the Handley Page O/400 replacement, and operated the Vickers type until disbanded in February 1920. Subsequently, the type equipped other Middle East squadrons, and No. 216, with Vimys, ran some of the first mail services between Cairo and Baghdad. No. 7 Squadron at Bircham Newton was equipped with Vimys in June 1923, although 'D' Flight of 100 (the nucleus of 7 Squadron), had previously operated them at Spittlegate. Nos. 9 and 58 home-based Squadrons received Vimys in April 1924, on the re-forming of those units.

After replacement by the larger and more powerful Virginias in 1924 and 1925, the Vimy remained in service with 502 Squadron at Aldergrove, Northern Ireland, until 1929. Subsequent to their withdrawal from firstline service as standard heavy bombers, Vimys were re-engined with aircooled radials, either Bristol Jupiters or Armstrong Siddeley Jaguars, in place of the water-cooled Rolls-Royce Eagles. These were used in flying training schools such as No. 4 F.T.S. at Abu Sueir, Egypt, and for parachute training at Henlow. From Biggin Hill a night-flying unit equipped with Vimys operated long after the type had disappeared from the rest of the Royal Air Force; in fact, the Vimy was used right up to the time of the Munich crisis in 1938 as target aircraft for the searchlight crews of the Royal Engineers training at Blackdown, Hants.

Vimy (F.B.27) Vimy Mk II (F.B.27A)

Accommodation: Pilot and 2 gunners Pilot and 2 gunners

Engines: Two 200 hp Two 360 hp

Hispano-Suiza Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII

Span: 67 ft 2 in 68 ft

Length: 43 ft 6 1/2 in 43 ft 6 1/2 in

Height: 15 ft 3 in 15 ft 7 1/2 in

Wing Area: 1,326 sq ft 1,330 sq ft

Empty Weight: 5,420 lb 7,101 lb

Gross Weight: 9,120 lb 12,500lb

Max Speed: 87 mph at 5,000 ft 103 mph at ground level

Climb to 5,000 ft: 23.5 min 22 min

Service Ceiling: 6,500 ft 7,000 ft

Absolute Ceiling: 9.500 ft 10,500 ft

Endurance: 3 1/2 hr 11 hr

Armament: Two Lewis guns Two Lewis guns

Eighteen 112-lb 2,476-lb bomb load

and two 230-lb bombs

Показать полностью

F.Manson British Bomber Since 1914 (Putnam)

Vickers F.B.27 Vimy

It is perhaps reasonable to speculate that, had a Vickers Vimy, flown by Alcock and Brown, not been the first aeroplane to fly non-stop across the Atlantic, the aircraft might have remained relatively obscure in the annals of the Royal Air Force; it was, after all, too late to give service during the First World War and, in the first half-dozen years of peace thereafter, it served on only five home-based squadrons.

Following hard on the heels of the decision to increase substantially the number of light bomber squadrons in the RFC, the Air Board opened discussions to investigate the possibility of introducing new heavy bombers into service with which to extend the offensive against German targets well beyond the Western Front. It has been told how large orders were quickly placed with Handley Page to hasten deliveries of the O/400, an excellent aeroplane, yet one that apart from the Eagle engines was already a long-established design.

The basic proposals for new heavy bombers were discussed at the Air Board's meeting of 28 July 1917 and, in response to the subsequent memorandum sent to Handley Page and Vickers, both companies embarked on new designs, three prototypes of each being ordered. The Vickers company was approached as it was known that its chief designer, Reginald Kirshaw Pierson, was already working on the preliminary design of a heavy bomber intended to meet the requirements set out in Air Board Specification A.3(B), issued in April, calling for an aircraft able to carry a 3,000 lb bomb load. In this he followed the general configuration of his previous F.B.7 and F.B.8 gun carriers (twin-engine biplanes), though of course the new bomber was to be much larger. The new requirements, in contrast to those of Specification A.3(B), placed less emphasis on bomb load and more on cruising speed and range, the former being reduced to around 2,200 lb and the latter increased to 90 mph and 400 miles respectively; an earlier demand for folding wings was also waived.

Reflecting the urgency attached to the new aircraft, the first Vickers F.B.27 prototype, B9952, was flown by Gordon Bell at Joyce Green on 30 November, only four months after the requirement had been first discussed, but made possible by use of the company's established steel construction.

Power was provided by two geared 200hp Hispano-Suiza engines and, with these, B9952 was delivered to the Aeroplane Experimental Station at Martlesham Heath in January 1918 where, despite some trouble with the engines, at an all-up weight (ballasted for a bomb load of 2,200 lb) it returned a sea-level maximum speed of 90 mph, thereby meeting the Specification's main requirements. This prototype featured horn-balanced ailerons on upper and lower wings, extending outboard of the square-tipped mainplane structure.

By then, however, all Hispano-Suiza engines were being allocated to production S.E.5A fighters, and the second Vickers prototype, B9953, was flown in April with a pair of 260hp Sunbeam Maori II engines, and delivered to Martlesham on the 25th. This aircraft featured inversely tapered ailerons, whose outer ends blended with the curved tips of the wings; it also introduced a ventral hatch through which a Lewis gun was mounted to fire, in addition to the upper gun positions in the nose and midships. B9953 was, however, to be destroyed in a crash in May.

At about this time the first aircraft was returned to Joyce Green, where the Hispano engines were replaced by a pair of 260hp Salmson 9Zm nine-cylinder water-cooled radials (though these engines never succeeded in producing more than about 230hp, and gave constant trouble with the cooling system).

The last o f the original Vimy prototypes, B9954, was fitted with 300hp Fiat A.12bis engines with octagonal frontal radiators, these having been scheduled to power the proposed 'Vimy Mark III' in production. Arriving at Martlesham on 15 August, this prototype demonstrated a maximum sea level speed of 98 mph while carrying 2,124 lb of bombs. This aircraft, however, was also destroyed when, on 11 September, it crashed on take-off for a bombing test from Martlesham and its bombs exploded.

Meanwhile an initial production order for 150 Vimys had been raised with Vickers Ltd for production at the cornpany's Crayford works, the engines being specified as the 230hp BHP, 400hp Fiat or the 400hp Liberty 12 - according to availability. In the event, only twelve of these aircraft were completed, and it is not known what engines were installed, although it is unlikely that any were fitted with Liberties as deliveries from America of these engines were temporarily halted in August.

With uncertainty surrounding the delivery of engines already flown in the Vimy, two further prototypes were ordered in August, it now being intended to fit 360hp Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII engines, whose production and delivery was assured. The first of these aircraft, F9569, arrived at Martlesham on 11 October for brief Service trials, returning a maximum speed of 103 mph at sea level. The aircraft was fitted with a single 452-gallon fuel tank in the fuselage bomb bay, sufficient for an endurance of about eleven hours while carrying two 520 lb bombs on external racks. This Vimy was then delivered to No 3 Aircraft Depot of the Independent Force in France, where it remained until after the Armistice. There is little doubt but that half-formed plans had existed for this aircraft to attempt a bombing raid on Berlin - involving a round flight of about 1.000 miles from the closest Independent Force aerodrome. Such a raid would have been marginally within F9569's capabilities.

The other new Vimy prototype, F9570, was destroyed by fire at Joyce Green before completion on 11 January 1919, but it is not known what engines were intended for this aircraft.

Production of the Vimy was severely reduced following the Armistice and, of the 776 then on order from Vickers and six other contractors, only 199 came to be built for the Royal Air Force, and contracted delivery dates were relaxed considerably owing to the postwar reductions in factory labour forces.

An order for 30 Fiat-powered Vimys (often referred to as Mark IIIs) was placed with the Royal Aircraft Establishment, but delivery of engines was erratic and only twenty aircraft were completed. As far as is known, only Eagle-powered aircraft were delivered to the RAF, and these became officially known as Mark IVs, simply to differentiate from the possible future use of the American Liberty engines in later aircraft (bearing in mind that many D.H.9As were to be powered by this powerplant). 150 Liberty-Vimys were ordered from Westland Aircraft Works, that company having been given the resposibility of designing the Liberty installation in the D.H.9A, but the superiority of the Eagle VIII in the Vimy caused this contract to be changed to the Rolls-Royce engine in the Westland-built Vimys, and the number of aircraft reduced to 25.

The first three production Mark IVs (one aircraft each from Vickers, Clayton & Shuttleworth and Morgan) were delivered in Februarv 1919. No homebased squadrons were yet scheduled to re-equip with Vimys and most of the early aircraft were shipped out to Egypt where they began to re-equip No 58 Squadron at Heliopolis in July that year, joining, and later replacing Handley Page O/400s.

Meanwhile, Vickers had begun the modifications to enable a Vimy to attempt an east-west non-stop crossing of the Atlantic, under conditions stipulated before the War for a prize of ?10,000 offered by the Daily Mail. The thirteenth aircraft in the production line at Vickers' new factory at Weybridge was modified to carry 865 gallons of fuel and all military equipment was omitted. The aircraft was shipped out to Newfoundland and, crewed by Capt John Alcock (later Sir John, KBE) and Lieut Arthur Whitten-Brown (later Sir Arthur, KBE) took off near St John's on 14 June 1919, landing 16 hours 12 minutes later near Clifden, Co Galway in Ireland, a distance flown of 1,890 miles.

The next long-distance Vimy was an aircraft prepared for the first aeroplane flight by Australians from Britain to Australia completed before the end of 1919, for which the Australian government was offering ?A 10,000. The flight was made by the two brothers, Capt Ross Smith and Lieut Keith Smith (later Sir Ross KBE and Sir Keith, KBE) of the Australian Air Force with crew members Sgts W H Shiers and J M Bennett. The flight was made between Hounslow, Middlesex, and Darwin, Australia, and took place between 12 November and 10 December, a distance of 11,294 miles being covered in 135hr 55min elapsed flying time.

The third of the great trail-blazing flights by Vimys was an attempt to fly from England to Cape Town by Lieut. Col Pierre Van Ryneveld (later Gen Sir Pierre, KBE, CB, DSO, MC) and Maj Christopher Joseph Quintin Brand (later Air-Vice Marshal Sir Christopher, KBE, DSO, MC, DFC, RAF). Setting off from Brooklands on 4 February 1920, their aircraft, however, crashed south of Cairo with a leaking radiator, and another attempt was made in a second Vimy, whose flight also ended prematurely, this time at Bulawayo in Southern Rhodesia. They completed their journey in a D.H.9, to be awarded ?5,000 each by the South African government.

At Heliopolis No 58 Squadron was renumbered No 70 in February 1920, this Squadron's role being that of bomber-transport, the Vimys being replaced by Vickers Vernon transports in November that year. The next Squadron to fly Vimys (including some of the aircraft just discarded by No 70) was No 45, reformed at Helwan as a bomber unit on 1 April 1921. This Squadron was tasked with route-proving flights throughout the Middle East in preparation for the introduction of commercial air travel in the region.

The first home-based Vimy Squadron to be equipped was No 100, newly returned from Ireland to become a day bomber squadron flying a mixed complement of D.H.9As and Vimys at Spittlegate (Grantham), and continuing in this role until May 1924 when it was re-equipped with Fairey Fawns.

The next Squadron to receive the Vimy was No 216, at the time regarded as the RAF's premier bomber squadron, having flown O/400s with great distinction during the War, and later equipped with D.H. 10s in Egypt. On receiving Vimys at Heliopolis in June 1922, the Squadron was declared a bomber-transport unit, dividing its efforts between practice bombing and carrying passengers (in some discomfort) and mail throughout the Middle East. No 216 Squadron continued to fly the Vimy until January 1926.

All the remaining four Vimy squadrons were home-based, No 7 re-forming at Bircham Newton in Norfolk with the aircraft on 1 June 1923, and continuing to fly them until April 1927. Most of the aircraft received on the Squadron from mid-1924 onwards were from a new production batch ordered in December 1923 (J7238-J7247). Nos 9 and 99 Squadrons, at Upavon and Netheravon respectively, began receiving Vimy IVs in April 1924, the former moving to Manston in the following month and the latter to Bircham Newton.

The last Squadron to receive Vimys was No 502 of the Special Reserve formed at Aldergrove on 15 May 1925, being declared a dedicated heavy bomber squadron and retaining these aircraft until July 1928.

Second-line duties performed by the Vimy included training, the type becoming the standard heavy bomber training aircraft during the early and mid-1920s. Many ex-squadron aircraft were converted with dual controls and issued to No 2 Flying Training School at Duxford and No 4 FTS in Egypt, and remained with these schools until the early 1930s. Others were used by the Parachute Training School at Henlow and by the Night Flying Flight at Biggin Hill. Many of these aircraft were re-engined late in their lives with air-cooled Bristol Jupiter and Armstrong Siddeley Jaguar radial engines when supplies of Eagle VIIIs became exhausted.

Type: Twin-engine, three-crew, three-bay biplane heavy bomber

Specification: War Office (later RAF) Type V of 1917.

Manufacturers: Vickers Ltd (Aviation Department), Knightsbridge, London (manufacture at Bexley, Crayford and Weybridge); Clayton & Shuttleworth Ltd, Lincoln; Morgan & Co, Leighton Buzzard; Royal Aircraft Establishment, Farnborough, Hants; Westland Aircraft Works, Yeovil, Somerset. Production orders placed (but cancelled) with Boulton and Paul Ltd, Norwich; Ransomes, Sims and Jefferies, Ipswich, Suffolk; Kingsbury Aviation Co, Kingsbury; and The Metropolitan Wagon Co, Birmingham.

Powerplant: Prototypes. Two 200hp Hispano-Suiza, two 260hp Sunbeam Maori II, two 260hp Fiat A.12bis, two 400hp Liberty 12 and two 260hp Salmson 9Zm engines. Production. Two 260hp Fiat A.12bis, two 230hp B.H.P., and (Mk IV) two 360hp Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII engines.

Structure: Composite steel tube and wooden construction with ply and fabric covering.

Dimensions: Span, 67ft 2in; length, 43ft 6 1/2in; height, 15ft 3in; wing area, 1,330 sq ft.

Weights (Mark IV): Tare, 7,101 lb; all-up (with 1,650 lb war load), 12,500 lb.

Performance (Mark IV with bomb load): Max speed, 103 mph at sea level, 95 mph at 6,500ft; climb to 6,500ft, 33 min; service ceiling, 7,000ft.

Armament: One Lewis gun on nose gunner's cockpit with Scarff ring, and another amidships. Bomb load, carried internally and on wing racks, could comprise two 230 lb and eighteen 112 lb bombs (a total of 2,476 lb).

Prototypes: Three, B9952-B9954; B9952 first flown on 30 November 1917 by Capt Gordon Bell. Other prototypes included F9569 (Mark IV prototype) and J6855 (ambulance prototype).

Production: A total of 776 Vimv bombers was ordered before the end of the First World War (excluding prototypes), of which 239 were built, all of them after the Armistice. Those built were: Vickers, 113 (F701-F712, F8596-F8645, F9146-F9195 and H9963); R.A.E., 10 (H651-H660); Clayton & Shuttleworth, 50 (F2996-F3045); Morgan, 41 (F3146-F3186); Westland, 25 (H5065-H5089). 30 Vimy bombers (all Mark IVs) and two ambulances were ordered after the War from Vickers, and all were built: J7143-J7144 (ambulances), J7238-J7247, J7440-J7454 and J7701-J7705.

Summary of Service: Vimy bombers served as follows: With No 7 Squadron at Bircham Newton from June 1923 to April 1927; with No 9 Squadron at Manston from April 1924 to June 1925; with No 24 Squadron at Kenley in 1925; with No 45 Squadron in Iraq from November 1921 to March 1922; with No 58 Squadron at Heliopolis from July 1919 to February 1920 and at Worthy Down from April 1924 to March 1925; with No 70 Squadron from February 1920 to November 1922 at Heliopolis, Egypt, and in Iraq; with No 99 Squadron at Netheravon and Bircham Newton from April to December 1924; with No 100 Squadron at Spittlegate from March 1922 to May 1924; with No 216 Squadron at Heliopolis, Egypt, from June 1922 to January 1926; and with No 502 Squadron of the Special Reserve at Aldergrove from June 1925 to July 1928. They also served with the Night Flying Might, Biggin Hill, and with Nos 2 and 4 FTS.

Показать полностью

P.Lewis British Bomber since 1914 (Putnam)

A further result of the decision of the Air Board on 30th July, 1917, to reverse its policy and to proceed again with development of the heavy night bomber was that contracts were placed forthwith for prototypes of new machines with Vickers and Handley Page. R. K. Pierson undertook the design of the Vickers bomber, three of which were ordered on 16th August, 1917, and which was designated F.B.27.

Pierson retained in the three-seat biplane the basic layout which he had earlier shown to Maj. J. S. Buchanan of the Air Board, and in under four months the prototype B9952 was ready. Twin tractor 200 h.p. Hispano-Suiza engines were mounted at mid-gap between the three-bay, equal-span wings, and the fuselage terminated in a biplane tail. The bomb load was accommodated inside the fuselage about the lower centre-section. Defensive armament was in the form of one Lewis gun in the nose position and another in the cockpit amidships. Four horn-balanced ailerons of generous area provided lateral control.

B9952’s first flight was at the Vickers aerodrome at Joyce Green on 30th November, 1917, piloted by Capt. Gordon Bell. B9953, the second prototype F.B.27, used a pair of 260 h.p. Sunbeam Maoris as power and exhibited several alterations compared with B9952. Two 300 h.p. Fiat A-12bis engines were fitted to B9954, the third F.B.27. Official trials were satisfactory, and the Vimy, as the F.B.27 was eventually called, was put into full-scale production, falling in the category of R.A.F. Type VII Short Distance Night Bomber. One Vimy only had reached the Independent Force in France before the war ended, and the type was never able to fly operationally against Germany.

Показать полностью

J.Bruce British Aeroplanes 1914-1918 (Putnam)

Vickers F.B.27, Vimy

IN the history of the Handley Page O/400 mention has been made of the events underlying the official decision to order night-bombers in quantity and the orders for the prototypes of new heavy bombers. Handley Page Ltd. and Vickers Ltd. each received an order for three experimental machines.

These orders were placed soon after the meeting of the Air Board which was held on July 30th, 1917, and work began on the Vickers design almost immediately. Responsibility for the new design was undertaken by Rex K. Pierson, who sketched his first ideas for the bomber during a discussion of the project with Major J. C. Buchanan at the Air Board. The aircraft which emerged with the designation Vickers F.B.27 bore a general resemblance to those rough sketches.

The design and construction of the first F.B.27 was accomplished in a little under five months, a remarkable achievement when the aircraft concerned was one so large. The F.B.27 was in fact largest aeroplane designed by Vickers Ltd. up to that time. It bore a family resemblance to the F.B.8 of 1915, but was almost twice as large.

The first F.B.27, which was numbered B.9952, was completed in November 1917, and was flown for the first time on the 30th of that month by Captain Gordon Bell. It was a three-bay biplane with wings of equal span, powered by two 200 h.p. Hispano-Suiza engines which were mounted mid-way between the wings. Each engine was enclosed in a wide nacelle, and each had a flat frontal radiator; the exhaust manifolds had tall slender stack pipes which passed through the upper wing in order to exhaust above it. These upright pipes were later removed.

The basic structure was conventional but, in keeping with Vickers practice, use was made of steel tubing in the fuselage: the forward portion was made wholly of steel tubing; behind the rear centre-section struts McGruer hollow spars were used. There was a gunner’s cockpit in the extreme nose and another behind the wings.

The mainplanes were made in three parts. The centre-sections spanned the distance between the engines, and only the outboard portions had dihedral. Horn-balanced ailerons were fitted to upper and lower wings.

The tail-unit was a biplane structure incorporating twin balanced rudders; there was no fixed fin surface. The elevators of B.9952 were horn-balanced but were later replaced by plain elevators, and new tailplanes were fitted.

In January 1918, the F.B.27 was flown to Martlesham Heath to undergo official trials, and created something of a sensation by lifting a greater load than the considerably more powerful Handley Page O/400.

At about this time the second F.B.27, B.9953, was completed. This machine had two 260 h.p. Sunbeam Maori engines, and was fitted with wings and ailerons of different shape from those of B.9952. The mainplanes had square extremities; and the ailerons, which were flush with the wing-tips, were inversely tapered and had no horn-balances. This F.B.27 was not extensively tested because it crashed on an early flight.

The third prototype, B.9954, was fitted with two 260 h.p. Fiat A-12 engines, and was modified in some particulars: it was, in fact, up to production standard. The nose of the fuselage was slightly altered and the extent of the plywood covering was increased. A revised fuel system, incorporating gravity tanks in the upper centre-section, was installed. The engines had flat frontal radiators, and could be distinguished by their single exhaust manifolds along the starboard side of each nacelle.

The third F.B.27 crashed soon after its arrival at Martlesham. It had been loaded with live bombs for test purposes: they exploded, wrecked the aircraft and killed the pilot. However, the performance of the Fiat-powered version proved to be good, and the F.B.27 was ordered in quantities.

The first prototype B.9952 was later fitted with two 260 h.p. Salmson water-cooled radial engines. This version of the design was not developed further, however.� By this time an official system of nomenclature for aircraft had been devised, and the name Vimy was bestowed upon the Vickers bomber. Even official documents conflict with each other over the allocation of Mark numbers, but the generally accepted system regards the first prototype as Vimy Mk. I, the Maori-powered machine as Vimy Mk. II, and the Fiat version as Vimy Mk. III. However, Technical Department Instruction No. 538A, dated January, 1919, lists Mks. I and II as the Maori and Fiat versions respectively, and gives the Mk. Ill designation to a Vimy powered by 230 h.p. B.H.P. engines. Production of the B.H.P.-powered Vimy was envisaged on a considerable scale, but it is doubtful whether any machines were completed with those engines.

The first production version of the Vimy was the Fiat-powered machine, which was earmarked for service as an anti-submarine patrol aircraft. There are indications that it may have been intended to adapt the Vimy to be a torpedo-bomber. The Armistice prevented the issue of any Vimys to coastal units, however.

The Vimy was ordered in large numbers: the first contract for 150 machines was given to Vickers Ltd. on March 26th, 1918, and by mid-September more than 900 had been ordered. It is of interest to note that, where types of engines were specified in the contracts, only the Fiat, B.H.P. and Liberty were mentioned. America was interested in the Vimy and had asked for an examination of the possibility of fitting two Liberty engines in the airframe. A trial installation was made, but the machine was destroyed by fire during erection at Joyce Green. The R.A.F. also asked for a Liberty-powered version, and a Vimy with twin Liberty engines was ultimately tested at Joyce Green. Doubtless the desire to use the Liberty engine was occasioned by the shortage of Rolls-Royce engines (for the Eagle would seem to have been a natural choice for the Vimy) and by the expectation of deliveries of Liberties.

That expectation was only partly realised, however, for deliveries of the American engine to Britain ceased in the summer of 1918. The Vimy then appeared in what was to be its best-known form, with two Rolls-Royce Eagle VIIIs, and the great majority of production machines had these engines. Official records agree that the Eagle-powered Vimy was the Mark IV. It seems that the first Vimy to have Eagle engines was F.9569. The engine nacelles were generally similar to those of the Fiat version, but had exhaust pipes along each side. Modified rudders with enlarged balance areas were fitted to F.9569, but production Vimys Mk. IV were fitted with fin surfaces in front of the rudders, presumably to counteract the greater torque of the more powerful engines. Production Vimy IVs had modified engine nacelles with slightly more angular lines than those of F.9569.

The performance of the Vimy IV was excellent. It could carry a worthwhile bomb load and fuel for an endurance of eleven hours at a top speed of 98 m.p.h. at 5,000 feet. It was intended to equip units of the Independent Force with the Mk. IV Vimy, and one was sent straight from Martlesham to Nancy in October, 1918. This was the only Vimy to go to France, but it arrived too late to see operational service before the Armistice and was returned to Martlesham to complete its trials.

After the Armistice production of the Vimy was reduced, but it was adopted for service use and remained in service for many years, both at home and overseas.

Despite its unspectacular Service career, the Vimy achieved immortality by its performances in long-distance flights immediately after the war. In a modified Vimy IV, Captain John Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown made the first non-stop aerial crossing of the Atlantic. Their Vimy carried 865 gallons of petrol and 50 of oil. Take-off was at 4.28 p.m. (G.M.T.) on June 14th, 1919, at Munday’s Pond, near St. Johns, Newfoundland: at 9.25 a.m. (G.M.T.) on June 15th, the Vimy landed at Glifden in Ireland with fuel for another 800 miles flight still in its tanks.

A Vimy IV also made the first flight from Britain to Australia. Flown by Captain Ross Smith with his brother Keith Smith as navigator, and Sergeants Bennett and Shiers as mechanics, the Vimy left Hounslow on November 12th, 1919. After a remarkable series of adventures and hardships, the machine reached Port Darwin, over 11,000 miles away, at 3 p.m. on December 10th.

The Vimy was again chosen for the flight to Cape Town made by Wing Commander H. A. van Ryneveld, D.S.O., M.C., and Flight Lieutenant C. J. Quintin Brand, D.S.O., M.C., D.F.C. With two mechanics they left Brooklands on February 4th, 1920, but a night forced landing 80 miles from Wadi Haifa wrecked the Vimy, which had been named Silver Queen. A second Vimy, powered by the engines of the first, was obtained; it left Cairo on February 22nd. Silver Queen II was wrecked at Bulawayo, and the flight was completed in a D.H.9 on March 20th, 1920.

In the post-war period the Vimys in R.A.F. service were fitted with various types of engine, and were widely used. The Vimy ended its Service career as a parachute trainer. A passenger-carrying conversion known as the Vimy Commercial did much good work in its own right, and was in turn developed into the Vickers Vernon troop-carrier.

SPECIFICATION

Manufacturers: Vickers Ltd. (Aviation Department), Imperial Court, Basil Street, Knightsbridge, London, S.W. (Prototypes built at Bexley; production undertaken at Crayford and Weybridge works.)

Other Contractors: Clayton & Shuttleworth, Ltd., Lincoln; Morgan & Co., Leighton Buzzard; The Royal Aircraft Establishment, Farnborough, Hants; The Westland Aircraft Works, Yeovil, Somerset. Production was also to have been undertaken by Boulton & Paul, Ltd., Riverside, Norwich, and by Ransomes, Sims & Jefferies, Ipswich, but the contracts placed with those two firms were cancelled before the Armistice.

Power: Two 200 h.p. Hispano-Suiza; two 260 h.p. Sunbeam Maori; two 260 h.p. Fiat A-12; two 300 h.p. Fiat A-12bis; two 230 h.p. B.H.P.; two 360 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII; two 260 h.p. Salmson; two 400 h.p. Liberty.

Dimensions: Span: 67 ft 2 in. (68 ft 4 in. with Maori engines). Length: 43 ft 6 1/2 in. Height: 15 ft 3 in. Chord: 10 ft 6 in. Gap: 10 ft. Stagger: nil. Dihedral: originally 1° on Hispano-Suiza version; 3° on production versions. Incidence: 3° 30'. Span of tail: 16 ft. Airscrew diameter: Hispano-Suiza, 9 ft 3 in.; Fiat A-12bis, 9 ft 5 in.; Eagle, 10 ft 6 in.

Areas: Wings: (Hispano-Suiza version) upper 684 sq ft, lower 642 sq ft, total 1,326 sq ft. (Maori) upper 709 sq ft, lower 667 sq ft, total 1,376 sq ft. (All other versions) upper 686 sq ft, lower 644 sq ft, total 1,330 sq ft. Ailerons: each 60-5 sq ft, total 242 sq ft. (Maori version) each 58-75 sq ft, total 235 sq ft. Tailplanes: (Hispano-Suiza) originally 88 sq ft, later 114-5 sq ft. (Other versions) 114-5 sq ft. Elevators: (Hispano-Suiza) originally 74 sq ft, later 63 sq ft. (Other versions) 63 sq ft. Fins (Rolls-Royce version only) two of 13-5 sq ft each.: Rudders: two of 10-75 sq ft each.

Tankage: Hispano-Suiza engines: petrol 91 gallons; oil 14 gallons. Fiat engines: petrol 170 gallons; oil 17 gallons. Eagle engines: petrol 452 gallons; oil 18 gallons.

Armament: The bomb-load could consist of eighteen 112-lb and two 230-lb bombs, carried in racks under the fuselage and lower centre-section. One Lewis machine-gun on Scarff ring-mounting on cockpit in nose; a second Lewis gun was carried on a Scarff mounting on cockpit aft of wings.

Serial Numbers:

Serial Nos. Contractor Contract No. Engine(s) specified in contract

B.9952-B.9954 Vickers, Bexley A.S.22689/1/1917 -

F.701-F.850 Vickers, Crayford 35A/532/C.4i2 Fiat, B.H.P. or Liberty

F.2915-F.2934 R.A.E. 35A/1029/C.834 Fiat

F.2996-F.3095 Clayton & Shuttleworth 35A/1030/C.835 See Note 1

F.3146-F.3195 Morgan & Co. 35A/1032/C.837 B.H.P.

F.8596-F.8645 Vickers, Weybridge 35a/i257/C.h66 See Note 2

F.9146-F.9295 Vickers, Weybridge 35A/1784/C.1895 See Note 2

F.9569 Vickers 35A/3872/C.4532 Eagle VIII

H.651-H.670 R.A.E. 35a/2O57/C-2334 Fiat

H.4046-H.4195 Boulton & Paul (Contract cancelled on August 30th, 1918) 35A/2295/O-2592 -

H.5065-H.5139 Westland 35A/2388/2689 Liberty

H.9413-H.9512 Ransomes, Sims & Jefferies (Cancelled November 1st, 1918) 35A/2938/C-3353 -

J.251-J.300 Clayton & Shuttleworth 35A/2978/C.34h See Note 1

J.7438-J.7457 - - Eagle VIII

It is believed that H.5230, H.9924 and J.7702 were Vimys.

Note 1. Of the Vimys ordered from Clayton & Shuttleworth, 124 were to be fitted with B.H.P. engines, the remainder with Fiats.

Note 2. Of the Vimys built by Vickers at Weybridge, it was intended to fit ten with Fiat engines, the remainder with B.H.P.s.

Production and Allocation: Over 1,000 Vimys were ordered. The Royal Aircraft Establishment built two in 1918, and Westland built twenty-five in 1918-19. One was sent to the Independent Force in 1918, and on October 31st of that year the R.A.F. had three on charge: one with the Independent Force and two at experimental stations.

Costs:

Airframe without engines, instruments and guns £5,145 0s.

Engines:

Fiat A-12bis (each) £1,617 0s.

Eagle VIII (each) £1,622 10s.

Показать полностью

H.King Armament of British Aircraft (Putnam)

Vimy. That the armament of the Vimy twin-engined bomber (1917) was given high priority during development is suggested by the melancholy fact that the third prototype was blown up by its own bombs at Martlesham Heath. Several alternative loadings appear to have been possible. For the Fiat-engined aircraft, declared obsolete by an Air Ministry Order of 1921, the following stowages appear to have been planned: eight 250-lb + four 112-lb internal (bombs nose-up); two 520-lb under lower longerons; four 230-lb under lower centre-section. The most common variant had Eagle engines, and this appears to have had provision for twelve 112-lb or 250-lb bombs internally; eight 112-lb under lower centre-section; four 112-lb under fuselage; two 230-lb under lower longerons. A loading of eighteen 112-lb + two 230-lb has been recorded and consideration appears to have been given to the earning of two torpedoes.

The heaviest military' load quoted by the makers was 3.410 lb, and in this condition the Eagle-Vimy had a petrol capacity of 1.670 gal, giving a range of 550 miles at 6.000 ft. cruising at 90 mph. The military load instanced probably corresponded to a bomb load of twelve 250-lb. Four Lewis guns and ammunition would account for only about 130 lb. so the rest of the military load would presumably be made up of gun mountings, bombing gear, flares, etc.

Although a load of two 520-lb bombs has been recorded for the Fiat-powered Vimy, similar provision appears to have been made, in post-war years at least, on Eagle-powered aircraft. The sight fitted to production Vimys was the Drift Bomb Sight, High Altitude, Mk.IA, bracket-mounted on the nose. Some post-war Vimys used for training had a modified bomb-aimer's station, in a lengthened nose.

Standard defensive armament of production Vimys comprised a Scarff ring-mounting in the nose, carrying a single Lewis gun; a similar installation on top of the fuselage, roughly in line with the trailing edges (an accompanying photograph confirms twin guns in this position); and a third station in the floor, lit by side windows. A single rear gunner manned the two last-named stations. For the nose gun(s) a 4 1/2-in Neame No.1 illuminated sight was specified, together with four spare ammunition drums; for the ventral gun there was a 2-in Neame No.2 sight, and the two rear positions shared six spare drums between them. A contemporary account stated of the ventral gun:

'The gunner is able to fire through the bottom of the fuselage in a horizontal direction towards the rear. He can thus aim at a machine following at the same level without hitting the tail plane of his own machine.'

A notable experimental installation on one Vimy was made by the fixing of a trunnion-mounted 37-mm Coventry Ordnance Works gun to a pillar mounting, attached externally somewhat lo starboard on a specially modified nose section.

Показать полностью

O.Thetford Aircraft of the Royal Air Force since 1918 (Putnam)

Vickers Vimy

The Vimy, together with the D.H. 10 Amiens and the Handley Page V/1500, was one of the new generation of bombers which, if the First World War had continued, would have been used by the R.A.F. for the bombing of Germany. However, the Vimy, unlike its contemporaries, enjoyed long service with the R.A.F. in the post-war years and until the introduction of the Virginia was the standard heavy bomber. Afterwards it served in various training roles until 1931.

The prototype Vimy (B 9952) made its initial flight in November 1917 with two 207-h.p. Hispano-Suizas and was followed by the Mk. II with 280-h.p. Sunbeam Maori engines, the Mk. III with 310-h.p. Fiat engines and the Mk. IV with 360-h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII engines. The Vimy IV became the standard production version and 240 were built, though many contracts were cancelled at the end of the First World War. The last of about 30 post-war Vimy IVs was the batch J 7701 7705 ordered by the Air Ministry in March 1925. On 31 October 1918 only three Vimy bombers had reached the R.A.K, and the type did not enter full service until July 1919, when it superseded O/400 bombers with No 58 Squadron in Egypt. It subsequently equipped other squadrons in Egypt and remained with No. 216 Squadron, operating some of the mail services between Cairo and Baghdad, until August 1926.

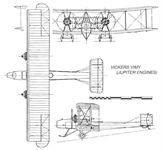

At home, Vimys of 'D' Flight of No. 100 Squadron at Spittlegate were the only twin-engined bombers in service until the formation of No. 7 Squadron at Bircham Newton in June 1923. No. 7's Vimys represented the R.A.F.'s entire home-based heavy bomber force until joined by Nos. 9 and 58 Squadrons in April 1924. In 1924 and 1925 the Vimy was replaced by the Virginia in first-line squadrons, but it remained on bomber duties with No. 502 Squadron in Northern Ireland until January 1929. From 1925 about 80 Vimys were re-engined with Jupiter or Jaguar radials (see three-view) and served at F.T.S.s and as parachute trainers at Henlow.

No account of the Vimy would be complete without reference to Alcock and Brown's epic Atlantic flight in 1919. This, however, was by a nonstandard Vimy owned by Vickers and cannot be credited to the R.A.F.

TECHNICAL DATA (VIMY IV)

Description: Heavy bomber with a crew of 3. Wooden structure, fabric covered. Maker's designation, F.B. 27A. Manufacturers: Vickers Ltd. at Crayford, Kent and Weybridge, Surrey.

Sub-contracted by R.A.F. (Farnborough), Morgan and Westland.

Power Plant: Two 360-h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII.

Dimensions: Span, 68 ft. 1 in. length, 43 ft. 6 1/2 in. Height, 15 ft. 7 1/2 in.

Wing area, 1,318 sq. ft. Weights: Empty, 7,104 lb. Loaded, 10,884 lb.

Performance: Maximum speed, 100 m.p.h. at 6,500 ft.; 96 m.p.h. at 10,000 ft. Initial climb, 360 ft./min.; 25.9 mins. to 10,000 ft. Range, about 900 miles.

Armament: Twin Lewis guns in nose and amidships. Bomb-load, 2,476 lb.

Vickers Vimy Mk IV

The Vimy, together with the DH 10 Amiens and the Handley Page V/1500, was one of the new generation of bombers which, had the First World War continued, would have been used by the RAF to bomb Germany. The Vimy, however, unlike its contemporaries, enjoyed long service with the RAF in the post-war years and, until the introduction of the Virginia, was the RAF’s standard bomber. Afterwards it went on to serve in various training roles until 1933.

The prototype Vimy, B9952, was first flown on 30 November 1917 powered by two 207hp Hispano-Suiza engines, and was followed by the Mk II version with 280hp Sunbeam Maori engines, the Mk III with 310hp Fiat engines, and the Mk IV with 360hp Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII engines.

Wartime plans for some 1,500 Vimy bombers were drastically reduced at the time of the Armistice, so that only about two hundred aircraft were completed on wartime contracts. These were within the serial ranges F701-F714, F2915-F2920, F2996-F3011, F3146-F3186, F8596-F8645, F9146- F9295, F9569, F9570, H651-H670 and H5065-H5089. Initially delivered straight into storage, many of them subsequently reappeared in the 1920s in the new all-silver livery. Post-war contracts between 1923 and 1925 produced an additional thirty Vimys, J7238-J7247, J7440-J7454 and J7701-J7705, in addition to two Vimy Ambulances, J7143 and J7144.

The Eagle-powered Vimy became the standard version with the RAF. The type did not enter full service until July 1919, when it superseded O/400 bombers with No 58 Squadron in Egypt. It subsequently equipped other squadrons in Egypt and remained with No 216 Squadron, operating some of the mail services between Cairo and Baghdad, until August 1926. In 1921 the RAF had eighty-eight Vimy bombers on its strength.

At home, Vimys of ‘D’ Flight of No 100 Squadron at Spittlegate were the only twin-engine bombers in service until the formation of No 7 Squadron at Bircham Newton in June 1923. No 7’s Vimys constituted the RAF’s entire home-based heavy bomber force until joined by Nos 9, 58 and 99 Squadrons in April 1924. In 1924 and 1925 the Vimy was replaced by the Virginia on first-line squadrons, but it remained on bombing duties with No 502 Squadron of the Special Reserve in Northern Ireland until July 1928.

From 1928 most Vimys underwent modification to be fitted with Jupiter or Jaguar radial engines (see accompanying drawing), and served at Flying Training Schools and as parachute trainers at Henlow.

No 2 FTS flew Vimys at Duxford between 1920 and 1924 and again at Digby from 1926 until 1932. No 6 FTS at Mansion had Vimys on strength in 1921-22, and No 4 FTS in Egypt operated them from 1921 until as late as 1933.

In 1928 some reconditioned Vimys were equipped with dual controls, and featured an extended nose section.

No account of the Vimy would be complete without reference to Alcock and Brown’s epic Atlantic crossing in 1919. These airmen were naval officers, and the Vimy was a non-standard aircraft, owned by Vickers, and the achievement cannot, therefore, be credited to the RAF.

TECHNICAL DATA (VIMY IV)

Description: Heavy bomber with a crew of three. Wooden structure, fabric covered. Maker’s Designation: FB 27A.

Manufacturer: Vickers Ltd, Crayford, Kent, and Weybridge, Surrey. Sub-contracted by RAE Farnborough, Morgan and Westland.

Powerplant: Two 360hp Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII.

Dimensions: Span, 68ft lin; length, 43ft 6 1/2in; height, 15ft 7 1/2in; wing area, 1,330sq ft.

Weights: Empty, 7,104lb; loaded, 12,500lb.

Performance: Max speed, 100mph at 6,500ft; 96mph at 10,000ft; initial climb, 360ft/min; 25.9 min to 10,000ft; range, approx 900 miles; service ceiling (normal load), 14,000ft, (max load), 7,000ft.

Armament: One Lewis gun in the nose and two amidships. Bomb load, 2,476lb.

Squadron Allocations: Nos 7 (Bircham Newton), 9 (Upavon and Manston), 45, 70 and 216 (Egypt), 58 (Egypt and Worthy Down), 99 (Netheravon and Bircham Newton), 100 (‘D’ Flight at Spittlegate) and 502 (Aldergrove).

Показать полностью

Jane's All The World Aircraft 1919

VICKERS "VIMY" TWIN-ENGINED BIPLANE.

The Vickers "Vimy" biplane was designed as a long-distance bomber, and, following the usual practice in twin-engined machines, has a single fuselage, carrying the pilot and two gunners, one in the nose and the other just aft of the trailing edge of the main planes.

The engines arc housed in " power eggs," each containing one complete power unit with its respective petrol and oil tanks, carried halfway between the planes, one on either side of the fuselage.

Under each engine-housing is a separate under carriage consisting of two vees of steel tube, between which an axle and two wheels are slung on shock-absorbers.

To prevent the machine standing on its nose after too fast a landing, a skid is fitted under the nose of the fuselage.

Four large balanced ailerons are fitted to the main planes. The empennage consists of a biplane tail unit with two unbalanced elevators, and turn rudders with no fixed fin-area.

It was on a Rolls-Royce engined Vickers " Vimy" that Capt. John Alcock, D.S.C, and Lieut. Arthur Whitten Brown made the first direct flight across the Atlantic ocean.

The following specifications give particulars of this machine fitted with various types of engine :

THE VICKERS "VIMY" (Fiat Engines.)

Type of machine Twin-engine Biplane.

Name or type No. of machine "Vimy" Fiat

Purpose for which Intended Bombing.

Span 67 ft. 2 in.

Gap 10 ft.

Overall length 43 ft. 6 1/2 in.

Maximum height 15 ft. 3 in.

Chord 10 ft. 6 In.

Total surface of wings 1,330 sq.ft.

Span of tail 16 ft.

Total area of tail 177.5 sq. ft

Area of elevators 63 sq. ft. (total).

Area of rudder 21.5 sq. ft. (total).

Area of fin None.

Area of each aileron and total area 60.5 sq. ft.; 242 sq. ft.

Maximum cross section of body 3 ft. 9in. by 3 ft. 9 in.

Horizontal area of body 125 sq. ft.

Vertical area of body 120 sq. ft.

Engine type and h.p. Fiat A/12/ Bis.

Airscrew, diam., pitch and revs. 9.4 ft dia., 5.85 ft. pitch, 1,700 revs.

Weight of machine empty 6,426 lbs.

Tank capacity in gallons Petrol 170 galls.; oil 17 galls.

Performance.

Speed low down 98 m.p.h.

Speed at 5,000 feet 96 m.p.h.

Landing speed 53 m.p.h.

Climb.

To 5,000 feet 14 minutes.

To 10,000 feet 45 minutes.

Disposable load apart from fuel 2,479 lbs, (including crew of 3)

Total weight of machine loaded 10,300 lbs.

Load per sq. ft. 7.75 lbs.

Weight per h.p. 17.2 lbs.

THE VICKERS "VIMY" (Hispano-Suiza Engines)

Type of machine Twin-engine Biplane.

Name or type No. of machine "Vimy" Hispano.

Purpose for which Intended Bombing.

Span 67 ft. 2 In.

Gap 10 ft.

Overall length 43 ft. 6 1/2 In.

Maximum height 15 ft. 3 In.

Chord 10 ft. 6 In.

Total surface of wings 1330 sq. ft.

Span of tail 16 ft.

Total area of tail 177.5 sq. ft.

Area of elevators 63 sq. ft. (total).

Area of rudders 21.5 sq. ft. (total).

Area of fin None.

Area of each aileron and total area 60.5 sq. ft.; 242 sq ft.

Maximum cross section of body. 3 ft. 9 In. by 3 ft. 9 In.

Horizontal area of body 125 sq. ft.

Vertical area of body 120 sq. ft.

Engine type and h.p. Two 200 h.p. Hispano-Suiza.

Airscrew, diam., pitch and revs. 9.25 ft. dia. 5 ft. pitch, 2,100 revs.

Weight of machine empty 5,420 lbs.

Tank capacity in gallons Petrol 91; oil 14

Performance.

Speed low down 90 m.p.h.

Speed at 5,000 feet 87 m.p.h.

Landing speed 51 m.p.h.

Climb.

To 5,000 feet 23.5 minutes.

Disposable load apart from fuel 2,900 lbs, (including crew of 3)

Total weight of machine 9,120 lbs.

Load per sq. ft. 6.85 lbs.

Weight per h.p. 22.8 lbs.

THE VICKERS "VIMY" (Rolls-Royce Engines)

Type of machine Twin-engine Biplane.

Name or type No. of machine "Vimy" Rolls.

Purpose tor which Intended Bombing.

Span 67 ft. 2 in.

Gap 10 ft.

Overall length 44 ft

Maximum height 15 ft.

Chord 10 ft. 6 In.

Total surface of wings 1,330 sq. ft

Span of tail 16 ft.

Total area of tall 177.5 sq. ft.

Area of elevators 63 sq. ft. (total).

Area of rudder 21.5 sq ft.

Area of fin None.

Area of each aileron and total area 60.5 sq ft ; 242 sq ft

Maximum cross section of body 3 ft 9 in. by 3 ft. 9 In.

Horizontal area of body 125 sq. ft.

Vertical area of body 120 sq. ft.

Engine type and h.p. Two 350 h.p. "Eagle Mark VIII" Rolls-Royce.

Airscrew, diam., pitch, and revs 10.5 ft. dia., 9 ft. 11 in. pitch, 1,950 revs.

Weight of machine empty 7,100 lbs

Tank capacity in gallons Petrol 452; oil 18.

Performance.

Speed low down 103 m.p.h.

Speed at 5,000 feet 98 m.p.h.

Landing speed 56 m.p.h.

Climb.

To 5,000 feet 21.9 minutes.

Disposable load apart from fuel 2.010lbs. (including crew of 3)

Total weight of machine loaded 12,500 lbs.

Load per sq. ft. 9.4 lbs.

Weight per h.p. 17.8 lbs.

Показать полностью

A.Jackson British Civil Aircraft since 1919 vol.3 (Putnam)

Vickers F.B.27 Vimy and Vimy Commercial

The Vickers F.B.27 Vimy twin engined bomber of 1918 saw no war service but was the fastest weight lifter of its age. Designed by R. K. Pierson as a three bay, fabric-covered biplane of mixed construction, powered by two 360 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VIIIs, it found employment in many peacetime Service roles and six became famous as civil aeroplanes. The first of these was the 13th Weybridge-built machine which was shipped to Newfoundland in April 1919 to be made ready for its historic Atlantic crossing. This was some weeks before civil flying was permitted officially and it was therefore too early to receive a registration. Piloted by Jack Alcock and Lt. Arthur Whitten Brown, it took-off from St. John’s, Newfoundland on 14 June 1919 with 865 gallons of petrol and 50 gallons of oil at an all-up weight of 13,300 lb. and touched down 1,890 miles away at Clifden, Ireland, 15 hr. 57 min. later, bogged and broken at the end of the world’s first transatlantic flight. After reconstruction at Weybridge it was presented to the Science Museum in London.

The first prototype Vimy, B9952, with 260 h.p. Salmson engines was allotted markings G-EAAR on 1 May 1919 but these were never carried and during its short career - a flight from Brooklands to Amsterdam in August 1919 for static display at the First Air Traffic Exhibition - wore the constructor’s number C-105. Active flying by the Vickers contingent was done by K-107, the Vimy Commercial prototype which had first flown at Joyce Green on 13 April and used the standard Vimy wing structure and tail unit mated to a rotund, oval section, plywood monocoque front fuselage seating 10 passengers. Entry was via a narrow opening in the port side, closed by a roller blind, and two pilots sat in an open cockpit high in the nose.

First flown on 20 September 1919, the next civil Vimy, G-EAOL, was a three seat bomber which left Brooklands in the following month for demonstration to the Spanish Government at Madrid. Although it disappeared into obscurity, its sister ship, G-EAOU, achieved immortality as winner of the Australian Government’s £10,000 prize for the first England-Australia flight. Piloted by Capts. Ross and Keith Smith and carrying Sgts. W. H. Shiers and J. M. Bennett as engineers, ’OU left Hounslow on 12 November 1919 and landed 11,340 miles away at Darwin, N.T., 27 days 21 hr. later on 10 December having averaged 75 m.p.h. for 350 flying hours, an incredible feat for those days and for which both pilots were knighted. After Sir Ross Smith’s 'death in the Viking IV accident at Brooklands (see page 206), the Vimy was stored for 35 years but in 1957 it was taken south from Canberra on two R.A.A.F. trailer vehicles for permanent exhibition in a glass memorial hall specially erected at Adelaide airport. Mainplanes, airscrews and cowlings were damaged by fire at Keith, 160 miles east of Adelaide while in transit on 3 November 1957 necessitating lengthy repairs which delayed final display for two years.

Inspired by the Australia flight, the Daily Mail put up a £10,000 prize for a flight from Cairo to the Cape for which three aircraft competed including Handley Page O/400 G-EAMC (Volume 2, page 226) and Vimy G-UABA ‘Silver Queen’ manned by Lt. Col. P. Van Ryneveld and Flt. Lt. C. J. Quintin Brand who left Brooklands on 4 February 1920 but crashed at Korosko in Upper Egypt. They continued in a borrowed R.A.F. Vimy named ‘Silver Queen II’ which crashed at Bulawayo.

<...>

After its success with the F.B.5 Gunbus replica (see page 351), the Vintage Aircraft and Flying Association built a Vimy replica, G-AWAU, powered by two Eagle VIIIs found in Holland, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the first Atlantic flight. It was first flown at Wisley on 3 June 1969 by B.A.C. test pilot D. G. Addicott who flew it to the Paris Air Show a few days later. Repainted in R.A.F. colours as H651 it then went to Ringway for exhibition to Alcock and Brown’s fellow Mancunians but was seriously damaged by fire due to the heat of the sun on 16 July. After repair it was donated to the R.A.F. Museum, Hendon, bearing a different R.A.F. serial, F8614.

SPECIFICATION

Manufacturers:

Vickers Ltd., Vickers House, Broadway, Westminster, S.W.l; Brooklands Aerodrome, Surrey and Joyce Green Aerodrome, Kent.

Power Plants:

Two 360 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII.

Dimensions:

Span, 67 ft. 2 in.

Height, 15 ft. 3 in.

Wing area, 1,330 sq. ft.

Length (Vimy IV), 43 ft. 6 1/2 in. (Commercial), 42 ft. 8 in.

Weights:

(Vimy IV) Tare weight, 7,101 lb. All-up weight, 12,500 lb.

(Commercial) Tare weight, 7,790 lb. All-up weight, 12,500 lb.

Performance:

(Vimy IV) Maximum speed, 103 m.p.h. Initial climb, 300 ft./min. Ceiling, 10,500 ft.

(Commercial) Maximum speed, 103 m.p.h. Cruising speed, 84 m.p.h. Initial climb, 375 ft./min. Ceiling, 10,500 ft. Range, 450 miles.

Production with export C. of A. dates: Forty-three Vimy Commercials: (c/n 1-40) China, including (39) G-EAUY and (40) G-EAUL; (41) G-EASI; (42) F-ADER Lions 23.12.21, Lorraine-Dietrich 30.6.22; (43) Russia 18.9.22.

Показать полностью

Журнал Flight

Flight, May 8, 1919.

THE TRANSATLANTIC CONTEST

DURING the past week the principal development in connection with the Transatlantic contest has been the accession of the Vickers-Rolls-Royce machine to the list of entries. Details of this machine are given below, and two photographs are reproduced on the next page.

The four-engined Handley Page machine, with Rolls-Royce engines left Liverpool on May 2, and it is not expected that it will be ready to leave Newfoundland before the June full moon.

With a view to giving them a better chance of getting away in certain winds, Messrs. Hawker and Raynham have been searching the island for an auxiliary aerodrome, but so far they have not met with any success. The weather has been so unsettled as to prevent any attempt at the flight.

Dr. Alexander Robinson, the Postmaster-General there, has sealed a second mail and handed it to Mr. Raynham for conveyance across the Atlantic. The stamps are specially surcharged "First Transatlantic Aerial Mail" on the ordinary three-cents stamps. To prevent forgery each stamp is initialled by the Postmaster-General.

While preparing to start for Newfoundland on May 5, two of the United States flying-boats were damaged. Two wings of the N.C. 1 were completely destroyed, and the lower elevator and tail plane of the N.C. 4 were badly damaged. The fire was caused by a spark from an electrically-driven pump falling on a drum of petrol, which took fire. It is expected, however, that N.C. 2 will be sent to Newfoundland as soon as the weather permits. The N.C. type of boat has a span of 126 ft. The lower wing span is 94 ft. The wings are 12 ft. chord. The length of the hull is 44 ft. 9 ins. Its gasoline capacity is 1,890 gallons, contained in 10 separate tanks. Four 400 h.p. Liberty motors are fitted.

The Vickers "Vimy" - Rolls-Royce

THE following information concerning the "Vimy-Rolls" entered for the Transatlantic flight has come to hand, and should prove of considerable interest. - ED.

The construction of the Transatlantic "Vimy" has now been completed at the Weybridge aeroplane works of Messrs Vickers, Ltd. This aeroplane is practically similar in every respect to the standard "Vimy" as supplied to His Majesty's Government. Two standard 350 h.p. Rolls-Royce engines are installed. The capacity of the petrol tanks has been increased to 865 gallons, and the lubricating oil tanks to 50 gallons. With this quantity of fuel the machine has a range of 2,440 miles. The maximum speed is over 100 mile per hour, but, during the flight across the Atlantic the engines will be throttled down to an average cruising speed of 90 miles per hour. The span of the "Vimy" is 67 ft., and overall length 42 ft. 8 ins. The chord of the planes is 10 ft. 6ins. A wireless telegraphy set, capable of sending and receiving messages over long distances, will be carried, and the pilot and navigator will wear electrically heated clothing.

The pilot, Capt. J. Alcock, D.S.C., was born at Manchester in 1892, and received his technical engineering education at the Empress Motor Works, at Manchester. He became interested in aviation in its early days, and adopted it as a profession. He took the Royal Aero Club's Flying Certificate at Brooklands in 1912, and rapidly rose to the head of his profession, taking part in a large number of the early competition flights, amongst others the well-remembered race London to Manchester and return in 1913, in which he secured second place.

At the outbreak of War he immediately joined the R.N.A.S., and was posted to Eastchurch as an instructor. Later he became the Chief Instructor of the Aerobatic Squadron. He did valuable work on the Turkish front, where he won the D.S.C., and held the record for long-distance bombing raids. He was eventually taken prisoner by the Turks owing to an engine failure, and remained as such until the end of the War.

The navigator, Lieut. Arthur Whitten Brown, A.M.I.E.E. M.I.M.E., A.M.F A.I.E., who will be known to our readers as the author of a recent article in FLIGHT on elementary navigation, was born in Glasgow in 1886, and his parents were American citizens. He is an engineer by profession, and received his practical training with the British Westinghouse Co., which is now allied with the Vickers Co. He received a thorough knowledge of surveying, and being interested in aviation, naturally devoted study to aerial navigation as applied to surveying. He enlisted in the University and Public Schools Corps in 1914, later receiving a commission in the Manchester Regiment, and served with the 2nd Battalion in France during 1915. He then transferred to the Royal Flying Corps as an observer, and was wounded and taken prisoner of war in the same year. He was later interned in Switzerland, and repatriated in December, 1917, since which time he has been engaged with the Ministry of Munitions on the production of aero engines, and has put in a considerable amount of flying at home stations. He is also a pilot of some experience, and has flown many types of machines.

Lieut. Brown, after duration tests in the Transatlantic "Vimy," considers he will have no difficulty in making a successful Atlantic flight. He intends to rely upon a system of navigation similar to that employed in marine navigation, and will carry wireless instruments capable of receiving and despatching messages for a distance of 250 miles, and be able to communicate with passing vessels.