J.Forsgren Swedish Military Aircraft 1911-1926 (A Centennial Perspective on Great War Airplanes 68)

Breguet C.U-1

A single Breguet C.U-1 (c/n 53) was delivered to the Royal Swedish Army. Pre-delivery test flights were made at Douai on June 1,1912 by Allan Jungner and Breguet factory test pilot Bebuisy. These tests included altitude, endurance, and load carrying capability. The airplane was then disassembled, and shipped directly to Axvall, where the regular summer army exercises were due to be held.

Henrik Hamilton, the Commander of the Kungl. Falttelegrafkarens Flygskola (Royal Field Telegraphic Corps Flying School), had learned to fly on Breguet biplanes, and was a strong advocate for such airplanes. As a result, assembly of the Breguet C.U-1 took precedence over the Nieuport IVG.The Breguet was designated B 1, ie Biplane 1.

Following assembly, much time was spent on taxiing the airplane around the field. On July 13, Allan Jungner made the first flight, which consisted of a single circuit around the field. The following day, Hamilton took off for his first flight. Just after taking off and having reached an altitude of between 25 to 30 metres, two cylinders suffered ignition failure. Although Hamilton escaped injuries in the resulting crash, the Breguet did not. The wings and landing gear were completely wrecked, with the engine also being badly damaged. After inspecting the bits and pieces, it was decided that airplane could be rebuilt.

Following repairs, the Breguet returned to the air on September 3. The last flight, on October 3, lasted 20 minutes, with Jungner and the observer Lieutenant Hogman landing due to strong winds. During the night, water pump froze, resulting in the airplane being dismantled and shipped to Stockholm for storage at the regiment Ing 3.

Between July 13 and October 3, the B 1 had flown a total of five hours and 49 minutes during 23 flights.

In early February 1913, the Breguet (along with the Nieuport IVG) moved to Lidingo outside Stockholm for winter flying exercise. On February 4, the newspaper Stockholms-Tidningen wrote: ’’The Bleriot machine (...) appear as fragile toys in comparison with these powerful behemoths (...) The Breguet in particular, the world’s fastest biplane - 104 kilometres per hour! - seems to be a terrible war machine, when the engine thundering like several machine guns in action, is started.” Almost daily flights were made on the icy lake surface.

By May 1913, the B 1 was based at Malmen outside Linkoping. On May 29, three flights were made. The following day, the Breguet landing gear suffered slight damage in a landing accident. The wheel was exchanged in 30 minutes, but when another flight was attempted, the engine decided to stop working.

On May 31, Hamilton, along with Sergeant Eugen Andersson as a passenger, made a return flight from Malmen to Norrkoping. On their way back, a forced landing had to be made at Kallerstad. When Hamilton and Andersson took off in the early hours of June 1, the engine stopped at an altitude of 100 metres. Hamilton had no choice but to set the airplane down in a muddy field. The Breguet overturned when it hit the ground, with the lower left wing being damaged beyond repair.

Repairs were quickly made, with the B 1 flying again on June 17. On July 17, Lieutenant Jungner flew to Stockholm, returning to Malmen three days later. During this time, between one and three flights were made daily.

On August 24, Jungner suffered engine failure, being forced down at Ekstrommen. The left wings were smashed, as was the propeller. Nevertheless, after only eight days, the B 1 was flying once again! The second crash of the year (and third in total) occured on October 28, when Hamilton (along with a conscript named Kallstrom) had to force land at Skanninge. Once again, the lower left wing and propeller took the brunt of the crash, with the landing gear also suffering damage. According to Hamilton’s post-crash report: "this damage is easily repaired.”

Along with the pair of Nieuports, the B 1 was temporarily based at Lidingo in early February 1914, before moving to Ostersund for winter trials. Continuous engine trouble resulted in the B 1 being flown only on a few occasions. Although skis were fitted, it is unclear if the airplane ever flew on skis. Neither is there no mention of the B 1 being used for the bomb dropping trials. On April 13, the winter trials ended, with the airplanes being dismantled and returned by train to Malmen.

On June 17, 1914, the B 1 was severely damaged for a fourth time when Hamilton force landed at Eslov. The propeller and one wing was damaged beyond repair. Upon mobilization on August 6, 1914, the B 1 was still undergoing repairs at Malmen. On September 1, the B 1 once again emerged from the workshop. Only four days later, on September 5, Hamilton suffered yet another forced landing, this time during army maneouvres at Arsta Garde south of Stockholm. According to a contemporary diary, the "machine (was) smashed.”

In an inventory list of available airplanes, dated January 15,1915, the B 1 is listed as “being repaired, whether or not capable of use afterwards cannot be determined.”

Nevertheless, the Breguet rose from the ashes once again. By early August 1915, the airplane was ready to fly. As Hamilton had retired from flying (and Jungner being killed in an automobile accident the previous year), a new pilot, Lieutenant Bror Mannstrom, was ordered to test fly the B 1. On August 12, Mannstrom conducted taxiing trials, making his first flight in the B 1 two days later.

On September 9, Mannstrom suffered a forced landing at Tolefors, with the airplane turning turtle. This time around, it was decided that enough was enough. Nevertheless, the B 1 was not formally struck off charge until January 19, 1917.

A reproduction B 1 (including some original components) can be seen at Flygvapenmuseum.

Breguet C.U-1 Technical Data and Performance Characteristics

Engine: 1 x 85 h.p. Canton-Unne

Length: 8,35 m

Wingspan: 12,70 m

Height: 3,25 m

Wing area: 35,25 m2

Empty weight: 500 kg

Maximum weight: 780 kg

Maximum speed: 105 km/h

Armament: -

Preservation

Breguet C.U-1

Following the Breguet’s demise, a few parts were set aside for preservation. Among these were the engine and the tail section. During the 1977 annual meeting of the Swedish Aviation Historical Society (SAHS), the possibility of constructing a full-scale reproduction of the B 1 was discussed at length. Thirteen contemporary drawings - showing the fuselage, wings and landing gear - were located at the National Museum of Science and Technology in Stockholm. Even though the set of drawings were incomplete (two drawings were missing), it was decided to push forward with the project.

Other contemporary documentation included military reports, photographs, articles from French and Swedish aviation and technical-oriented magazines, and even 35 mm film footage, taken in 1913 and 1914. A few individuals, who had worked on the B 1 between 1912 and 1916, were interviewed, but only one, Karl Lignell, could provide useful information, particularly regarding the background to some of the photographs and the B 1’s color scheme.

The volunteer Arlanda Group (which later changed their name to the Tullinge Group after relocating to Tullinge), led by Gothe Johansson, were to reconstruct the airplane, with financial backing from Flygvapenmuseum and the Swedish Aviation Historical Society. Contacts with the Musee de I’Air, which was about to refurbish the Breguet R.U-1 (c/n 40), preserved by the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers in Paris, resulted in the Swedish team being given complete access to this airplane.

Actual work began in 1978 in a workshop at Barkarby north of Stockholm. Gothe Johansson built the wooden fuselage in his house, with the wings being constructed using information collated during the refurbishment of the French Breguet R.U-1. The progress of the B 1 reconstruction was covered by Swedish media, which occasionally resulted in new information, or parts, emerging. Among the latter was an engine magneto coil.

By 1988, the airplane was essentially complete, with the liquid-cooled radial Canton-Unne engine being restored to running order. On February 11,1989, the B 1 was pulled out of its hangar for an engine test. Careful preparations had been made to only run the engine on four out of its seven cylinders. This was made possible by using an ignition system off a Ford Model T. The sound of the engine, bursting into life after 73 years, sounded exactly like as it had been vividly described in contemporary newspapers; "like one-hundred machine guns firing at once!”

On February 22, the B 1 was disassembled, and trucked to Flygvapenmuseum, where the airplane was formally handed over on February 27. It has remained on display ever since.

Показать полностью

Журнал Flight

Flight, December 17, 1910

AEROPLANE SILHOUETTES FROM THE PARIS SHOW.

THE BREGUET BIPLANE.

CONSTRUCTED by Louis Breguet at Douai. Fuselage and framework of steel and wood. Planes double-surfaced throughout. The main planes are connected by four stanchions placed a short distance back from the leading edge. Well known for its weight-lifting powers. On one occasion M. Breguet carried five passengers beside himself, the total weight of the six persons being 420 kilogs. Beside the one described, a racing model with only 26 sq. metres bearing surface, and fitted with a higher-powered engine, is also made.

General Dimensions. - Bearing surface, 38 square metres. Length, overall, 9.20 metres. Span of upper main plane, 13-20 metres; of lower main plane, 9 90 metres. Wings of normal type are 170 metres broad.

Seating capacity. - Two seats, placed one behind the other.

Engine. - 50-60-h.p. 5-cyl. semi-radial R.E.P. motor. Normal revs., 1,000. Any motor fitted.

Propeller. - Breguet, of two blades. Diameter, 2.90 metres. Geared down, variable pitch. Normal revs., 600.

Chassis. - Three wheels, one centrally in front of other two (which are each double); short skids in front of each wheel; front wheel is steerable by means of ordinary control wheel. The entire aeroplane is suspended on these three wheels, there being neither skid nor wheel under the tail.

Tail. - Cruciform monoplane tail, mounted on universal joint.

Lateral stability. - By the flexing of the trailing edges of the main planes.

Weight. - About 475 kilogs. complete with motor.

Speed. - 85 kiloms. an hour.

System of control. - By a wheel placed on a lever. Rotation of the wheel steers the machine. Backward and forward movements of the entire column elevate and depress the aeroplane, and a sideways movement to the right or left depresses the opposite wing in either case.

Price. - With 50-60-h.p. R.E.P. motor, 30,000 francs.

Flight, January 28, 1911

Advancing the Passenger Carrying Record.

PROGRESS continues in practical work accomplished by aeroplanes. On the 19th inst., at Douai, Breguet on a military type Breguet aeroplane (R.E.P. motor), which has been acquired by the Russian Government, beat the world's record for passenger carrying by covering 50 kiloms. in 34 mins. 54 1/5 secs, and 100 kiloms. in 1h. 9m. 28 4/5s., giving an average of 86.368 k.p.h.

Flight, April 1, 1911.

Third International Aero Exgibition at Olympia - 1911.

THE EXHIBITS ANALYSED.

<...>

On the Breguet biplane, where the relative positions of the engine and pilot are reversed, the tail becomes, practically speaking, a non-lifting member, although in actual practice the tail of the Breguet is a slightly cambered plane. Incidentally, of course, the Breguet system facilitates the use of a monoplane type body, because the propeller, being in front, does not interfere with the continuity of the longitudinal spars in the construction of such a member. The enclosing of the body so as to be more or less of stream-line form, which feature has already been discussed, is, of course, only a natural evolution as the outcome of taking a further step in detail design. While on the subject of the Breguet machine it should also be mentioned that quite apart from the question of type this model belongs to a class apart in any case, because it is constructed entirely of steel - timber being now, as formerly, the standard material for aeroplane framework. The Breguet-type aeroplane made by the British and Colonial Aeroplane Co. is constructed of wood.

<...>

Flight, April 29, 1911.

A Breguet Biplane for the Russian Army.

ON the 20th inst. Capt. Alexandroff paid a visit to M. Breguet's headquarters near Douai, to witness a Breguet biplane built for the Russian Army put through its paces. With M. Breguet himself at the wheel the machine had no difficulty in passing the tests laid down, and Capt. Alexandroff expressed himself thoroughly satisfied with the result.

Flight, June 24, 1911.

Breguet Machines for French Army.

AT the Douai Aerodrome on the 15th inst., Lieut. Ludmann and Lieut. Fequant, on behalf of the French military authorities, accepted delivery of five Breguet biplanes. Each one was put through a test flight by either M. Breguet or Debussy, and attained an altitude of 600 metres, a speed of 95 k.p.h., with a useful load of 305 kilogs. on board. Breguet, flying with the wind, attained a speed of 120 k.p.h.

Flight, July 22, 1911.

THE BREGUET AEROPLANE.

AT a time when everything in aeronautics is virtually new it seems inappropriate to refer to any particular machine as out of the ordinary, but the stereotyping influence of the popularity of one or two leading makes has already had a marked tendency in fixing ideas in aeroplane construction so that it is, after all, a matter of necessity to say of the Breguet aeroplane that it is a machine of uncommon design and exceptional interest.

In the first place it is built of steel throughout, whereas most aeroplanes are built of timber with minor metal fittings. The body of the Breguet aeroplane has, in fact, a frame built up with pressed-steel channel-section side members just like the frame of the chassis of a motor car, which point is worthy of immediate reference as it serves to emphasise the completeness of the steel structure and also happens to be invisible in the accompanying illustrations. Another important feature of the Breguet design, which is now becoming more common, is the monoplane type body in conjunction with biplane wings. This firm was one of the first to introduce the combination, and, indeed, M. Breguet was in the habit of describing his aeroplane as a double monoplane, but this definition is not in accord with our own terminology, and it seems to us impossible to regard the Breguet aeroplane as other than a biplane pure and simple, for the planes are unquestionably superposed and their only difference is one of span. The span of the upper plane is, as a matter of fact, very much greater than that of the lower plane.

In the construction and mounting of the main planes the outstanding feature that is apparent from a glance at the accompanying illustrations is the use of a single row of struts, whereas most biplanes have their wings separated by a double row of struts. The presence of only a single row of struts is an indication of the presence of but one main spar and, indeed, the real feature of the Breguet planes is related to this fact. The surfacing material is stretched on ribs that are in themselves flexible and have in addition a flexible attachment to the tubular steel main-spar. (The constructive detail is mentioned in Patent No. 7209 of 1909.) The result is an automatically variable angle of incidence, which the makers also claim acts in the nature of a spring suspension, or, shall we say, "shock damper" in the air.

(To be concluded.)

Flight, July 29, 1911.

THE BREGUET AEROPLANE.

(Continued from page 625.)

WHEN at rest the planes have an angle of incidence of about 11°, the strength of the construction is such that under test a load of 20 lbs. per sq. ft. reduces the angle of incidence to about 2° without permanently distorting any of the constructive details. Tests made by loading the wings with sand have been conducted officially at the Douai works. Of the importance of a variable angle of incidence in connection with the problem of variable speed our readers are already acquainted through our discussion of the subject in a series of articles entitled ''Can we fly faster for less Power," which appeared in FLIGHT recently.

An important outcome of the use of but one row of struts between the main planes is that provision can be made for folding the wings against the body of the machine as a means of reducing the bulk for transport. The manner in which this is done on the Breguet aeroplane is very clearly illustrated by the accompanying illustrations, one of which is a photograph of the machine with its wings thus folded. When we speak of a single row of struts it is necessary to observe that even this single row comprises only four struts in all, and of these four two are immediately adjacent to the body of the machine; thus there is but one strut that is in any way in a position to interfere with the folding of the wings, and this, as will be evident from the photograph, constitutes no sort of inconvenience in practice. The wings are attached to the body by a knuckle-joint that is itself anchored by an adjustment bolt as shown in one of the sketches. This adjustment affords a means of varying the normal angle of incidence, but it is a shop adjustment and users of the machine are not supposed to tamper with it. When disconnected the entire wing can be turned into a vertical position, that is to say, with an angle of incidence of 900, and in this position the knuckle-joint enables the wing to be folded back against the body of the machine. Both wings are rotated in this manner but the initial movement takes place in opposite directions, that is to say, the lower plane has its trailing edge raised, while the upper plane has its trailing-edge lowered. In this way the wings overlap and occupy a minimum of space.

Whilst dealing with the constructive details associated with methods of attachment, it is interesting to observe the manner in which the tail is mounted on the frame by a universal-joint. The details of this joint are also shown in one of the sketches. The tail itself is somewhat uncommon, too, inasmuch as it is of the cruciform type and moves en bloc. The vertical plane is the rudder and the horizontal plane the elevator, but neither can move without the other. The whole structure is carried on the universal-joint already mentioned and is braced to the body by wires that contain fairly stiff compression springs in order that they may accommodate themselves to the movements of the control.

The system of control on the Breguet aeroplane includes wing-warping for balancing and the use of the elevator and rudder already described. These operations are carried out by means of a universally pivoted lever fitted with a steering-wheel at its upper extremity. Rotation of the wheel moves the rudder and the to and fro movement of the lever which forms the steering-column operates the elevator. A sideways movement of the steering-column warps the wings. Either operation can thus be carried out separately or all can be carried out simultaneously. A minor point well worthy of notice is that the wing-warping wires are attached to the steering-column by springs so that the action of wing-warping is necessarily performed gradually.

In addition to the tail already described there is a fixed tail plane situated beneath the body and in advance of the elevator. The object of this fixed tail plane is, of course, to stabilise the machine, and it is designed to carry the light load represented by the after part of the body and the movable tail members. Practically speaking the machine is in balance about the spars of the main wings, for the engine and propeller are situated well forward to balance the pilot, who sits rather to the rear of the trailing-edges of the main planes. In front of the pilot is the passenger, and as our readers know, the Breguet aeroplane has been successful in flying with exceptionally heavy loads.

The undercarriage, like every other part of the machine, is of distinctly original design. It is a three-wheeled structure so arranged that the forward wheel of the three can be used for steering the machine over the ground. For this purpose it is inter-connected with the rudder. The struts by which the undercarriage is attached to the body of the, machine are telescopic and are fitted with compression springs, two of them also have oil shock-dampers. Short skids are provided as a protection against very rough landing, such as might damage the wheels, but lit will be noticed that the wheels themselves are unusually small in diameter and therefore unusually strong.

Flight, September 16, 1911.

Flying in Morocco.

BREGI with a Breguet biplane has arrived at Casablanca where he is to be at the disposal of General Bonnier. He is shortly to carry out a flight with two passengers from Casablanca to Tangier via Rabat, Mequinez, and Fez.

Flight, September 23, 1911.

FLYING IN MOROCCO.

LAST week Bregi on his Breguet machine succeeded in flying with a passenger from Casablanca to Fez, a distance of about 300 kiloms. The idea was started by the Petit Journal, which offered to pay the expenses of the expedition, while the Breguet firm co-operated by lending one of their three-seated machines. Bregi happened at the moment to be doing his military service, so he was sent with the machine to General Moinier in order that he might assist him in the operations which were taking place. After making several flights in the neighbourhood of Casablanca, Bregi, on the 14th inst., set out with M. Lebaud, of the Petit Journal, to fly to Fez. They carried on board their arms and provisions as well as camping equipment, the latter including a cover for the machine in case it should be necessary to land during a storm. The pilot, passenger and baggage represented a load of about 350 kilogs. Bregi on starting from Casablanca made for Rabat, stopping on the way at Feldha in order to deliver a message to his uncle who is in command of a regiment of Zouaves. On the following day he continued on his way and reached Fez safely.

Flight, September 30, 1911.

The Casablanca-Fez Flight.

BREGI did not actually complete his flight to Fez quite so quickly as was reported in our last issue, the mistake being due to a telegraphic error. He was detained at Rabat for five days mainly owing to the sand storms, and it was not till Tuesday morning last week that he was able to get on from Rabat to Mequinez, covering the 81 miles in 1 hr. 35 mins. Delay was experienced there owing to the scarcity of petrol, but on Thursday morning the journey was resumed and Fez reached safely, the aviator and his companion being given a hearty welcome by the European colony at the Moorish capital.

Flight, October 7, 1911.

AIR EDDIES.

HENRI BREGI has undoubtedly had a much better time touring on his Breguet biplane in Morocco, where the natives have been prostrating themselves to the ground before his mechanical bird, than he would have had as a simple sapper in the French military manoeuvres. It is not generally known that the machine on which he has carried out these splendid flights is the same one as that used by de Montalant in breaking the world's record for altitude with a passenger at Brooklands some six weeks ago.

Flight, December 16, 1911.

A Medal for Bregi.

FOR his services in Morocco, and especially for his flight from Casablanca to Fez, Bregi, the Breguet pilot, who is also a sapeur aerostier in the Third Regiment, has been awarded the military medal by the French Minister of War.

Flight, January 6, 1912.

PARIS AERO SHOW.

Breguet.

AMONGST the biplanes present at the Salon there is no doubt that the productions of the Breguet firm must be given pride of place by virtue of the excellence of their performances of the various military trials of the past year. One of the machines on view was the identical machine with which the pilot Moineau obtained second place in the final classification of the machines at the French military trials at Rheims. The machine with which Bregi carried out his flights in Morocco from Casa Blarica to Fez, which machine was previously used by de Montelant at Brooklands in beating the British height record with passenger, was given a place of honour in the gallery. The third was a standard type biplane fitted with a 75-h.p. six-cylinder Chenu motor, driving through reduction gearing a three-bladed Breguet-Regy propeller. In order to preserve more effectively the natural torpedo-like outline of the Breguet fuselage, the engine is covered in by a neat housing of sheet steel. Further improvements had also been made in the bodywork itself, a miniature side-entrance door and light steel ladder being provided to facilitate ingress and egress.

Principal dimensions :-

Length 30 ft. Weight 1,430 lbs.

Span 45 ,, Speed 55 m.p.h.

Area 363 sq. ft. Motor 75-h.p. Chenu.

Price L1,400.

Flight, March 16, 1912.

AEROPLANE UNDERCARRIAGES.

By G. DE HAVILLAND.

Breguet Biplane.- The Breguet undercarriage is a distinct departure from the ordinary type. In this machine the designer has successfully provided a real shock-absorbing device in place of the usual rubbers or springs. The rolling wheels are only 15 in. diameter, with 3 1/2 in. tyres, and therefore well adapted to withstand side strains, at the same time they are comparatively light. No skid is fitted to the rear part of the machine, but the rudder is designed to perform this function should it come in contact with the ground. The weight is normally taken by the two rolling wheels, which are placed under the centre of gravity, and the propeller thrust is sufficient to pull the machine on to the single front wheel, which is steerable, and is coupled up to the hand wheel that operates the rear rudder. By this device the machine can easily be manoeuvred on the ground. This undercarriage has a very short wheel base, and, as might be expected, this does not make for easy rolling on uneven ground. Reference will be made to the Breguet shock absorber later on.

Flight, July 20, 1912.

THE MILITARY COMPETITION - THE MACHINES.

THE BREGUET BIPLANE.

THOSE who attended the flying at the London Aerodrome on Saturday last were treated to a splendid display by Moineau on a machine that is relatively an uncommon one in England - a Breguet. This particular biplane is furnished with a 14-cylinder 100-h.p. Gnome, and drives two two-bladed propellers - virtually a four-bladed one - through pinion reducing gear. As it is the machine that will probably represent the Breguet firm in the forthcoming military trials a brief description will not be amiss.

The photographs we publish give some idea of its appearance; the frontispiece this week shows the machine flying with Moineau as its pilot.

In its design, the greatest ingenuity has been displayed in establishing a machine that will be to a great extent automatically stable, easy to control and transport from place to place, speedy and strong, that will lift much weight, and that will afford the pilot a large degree of safety. All these desiderata, and many more that, perhaps, are not so important as the above, M. Louis Breguet has provided for in the biplane that bears his name.

In the first place, it is a tractor biplane, and for that the pilot may reassure himself with the thought that a lot has to "go" before any of the effects of an assumed smash reach him, that is, if he is suitably strapped to his seat. Again, this system of construction lends itself extremely well to facility of dismantling. A most noticeable point about the cam planes is the small number of vertical struts employed in bracing them. Only four very stout ones are used, and they are arranged in a single rack. In this present machine two extra struts are used to support the top plane extensions. The planes themselves are built about a single tubular spar of steel disposed at the average centre of pressure of the surface - about one-third of the chord from the leading edge. By the Breguet system of fastening the ribs to the spars a very supple supporting surface is formed - a feature which accounts for the remarkable steadiness of the machine in flight and for the ease with which it may be handled in a strong wind. Being so enormously strong, the steel framework needs but little wire bracing, and what there is is calculated to withstand ten times the strain it is likely to be called upon to bear. The body is of torpedo form, constructed of steel tubing, steel girders and ash, the whole covered in by fabric to reduce head resistance to the lowest possible degree.

Here we might mention that wood plays very little part in the construction. It only appears to a very limited extent in the wing and tail skeletons, in the body, and in the landing gear. This latter is formed of three wheels - each protected by a skid. The two main wheels support the body of the machine through oleo pneumatic springs of special design, and they are disposed as near as possible under the centre of' gravity. The forward wheel, spring suspended, is rotatable in conjunction with the rudder, so that when the propeller thrust pulls it into contact with the ground, it may be used for steering on the ground, as one would a motor car.

All three dimensions of control are centred on one column, surmounted by a vertical hand wheel. Rocking it to and fro controls the elevation, from side to side the warping and rotating the hand-wheel governs the rudder. Into all control wires steel coil springs are introduced, to make movements less harsh in action.

The tail is an enormous cruciform organ mounted to the rear point of the fuselage by a massive universal joint.

An idea of the ease with which a Breguet may be got ready for flight is conveyed by the fact that some time since at the La Brayelle aerodrome a machine was completely folded in five minutes and rendered ready for flight in another eight.

Flight, August 10, 1912.

THE MILITARY AEROPLANE COMPETITION - THE MACHINES.

THE BREGUET BIPLANES.

Both the Breguet biplanes met with misfortune in being got to Salisbury Plain. The one flown over by Moorhouse met with a contretemps at Ashford in Kent. The other started from London on Tuesday, July 30th, being conveyed on a trolley drawn by a steam tractor. At both Basingstoke and Andover, wheels gave out, while some time later one of the axles broke. These accidents, of course, occurred to the trolley, and when the biplane was examined at Lark Hill it was found not to be damaged in any way. The delay, however, had prevented it from being present while the assembling tests were in progress.

Neither machine presents any very great difference from the customary Breguet design, excepting that the motors are fitted in a horizontal position, instead of a vertical, as heretofore.

The drive to propeller, instead of being direct, has therefore to operate through a bevel which is geared down 1 to 1.8. The propeller speed is about 720 revs, per minute.

A point to notice is the system whereby the pilot may, if necessary, disconnect the passenger's control while in flight by means of a foot pedal.

Brakes to assist in pulling up after landing are fitted. They are also operated by a foot pedal.

It is possible to start the engine from the passenger's seat.

Main characteristics :-

Overall length 34 ft.

Speed 72 m.p.h.

Span 47 ft.

Weight without complement or fuel 1,300 lbs.

Area 400 sq. ft.

Flight, November 16, 1912.

THE PARIS AERO SALON.

British Breguet.

As we mentioned earlier in our reports, two British firms recognised the wisdom or were in a position to avail themselves of the wisdom, of exhibiting their goods at the Paris Salon. One firm was the Bristol Co., the other Breguet Aeroplanes, Ltd., of 1, Albemarle Street, Piccadilly, W. Under the direction of M. Gamier, the latter firm exhibited a beautifully constructed Breguet three-seater warplane, equipped with one of the new 110-h.p. horizontal Canton-Unne motors. In its main features it is a machine very similar to that which the British Breguet firm sent to Salisbury to compete, last August, in the Military competition there. But as regards its landing gear there is a change, for the single front steerable wheel has been replaced by a pair of wheels mounted on a short axle which is connected to a heavy gauge steel tube extending downwards from the nose of the fuselage by means of a transverse laminated steel spring. We print a sketch to illustrate this point. The rear pair of wheels of the chassis remain as they were formerly, supporting the main weight of the machine through heavy oleo-pneumatic springs of patented design. The body of this machine is covered in entirely with aluminium sheeting, and a very warlike looking job it makes. However, in future machines they intend to cover the fuselage with "Durehide," a type of "synthetic" leather. This material, as a matter of fact, is used on the present machine to bind the leading edge of the planes, in place of the aluminium sheeting that was formerly employed. One of the most noticeable features of this excellent biplane is the care with which the fuselage has been designed and shaped to avoid as much head resistance as possible. This is the chief reason for the setting of the engine in a horizontal position. Another interesting exhibit on the stand was a clever system of dual control, the subject of a patent held by the British Breguet Co. It is so arranged that while the pilot and the observer may have control of the machine, either separately or in unison, the pilot always has command of the situation. By means of a small hand lever he is able at any moment, if the observer is driving, to deprive him of the use of his controls. Further, it is arranged, that should the pilot, in action, be killed or so seriously wounded as to render it impossible for him to continue in charge of the machine, the observer may, by reaching behind him and altering the position of the hand lever, transfer the entire control of the machine to his own column.

Flight, February 22, 1913.

SOME MORE AEROPLANES AT OLYMPIA.

BREGUET AEROPLANES, LTD.

Breguet Aeroplanes, Ltd., who since July of last year have been constructing military biplanes under licence from the French Breguet firm, have on exhibition an 85-h p. Breguet Warplane, the seventh machine they have built since their works at Willesden were put in operation. The outstanding feature of the machine is that it is built throughout of steel, wood being only employed for the manufacture of its ribs. Since he first turned his mind to aeroplane construction, Louis Breguet has favoured steel as the medium of construction of his machines, and to him must be given the credit of having "set the fashion," as it were, for this system of manufacture. He, also, was one of the first to construct a tractor biplane, a type of machine which he has helped, in no small manner, to popularise. At first he was laughed at for his pains; his biplane was jokingly spoken of as a "coffee pot." But since, he has earned the recognition that he so well deserved.

Next in order of importance of the features of his machine is the peculiarity that the supporting and directional surfaces are flexible. The controls, even, are not directly connected to the planes that they operate; steel tension springs are inserted in the control wires, so that, however harsh may be the pilot's movements of his controlling lever, the directional planes change their attitude gently. It is claimed for the Breguet machine that it has been designed as one harmonious whole, not merely as a series of separate units, such as body, chassis and planes, afterwards assembled together.

The body is of two distinct parts, that forward of the pilot's seat, and the portion that extends away behind it. The latter section is formed by a single steel tube, some three inches in diameter, which is braced by numerous steel wires to a four-armed steel fitting welded over the tube just behind the pilot's seat. By the application of sheet aluminium over these wires a very good streamline covering is obtained. The aluminium covering is further supported by longitudinal wood stringers. To the rear end of the large diameter central tube is attached the tail, universally jointed. In front of the pilot's seat, the foundation of the fuselage is formed by two U-section steel girders, wood filled. At right-angles to them, in front of the passenger seat, are fitted the two uprights to which the top planes are attached. Still further in front they converge to form a substantial base to which the motor is bolted. From a casual glance at the machine, no one would think that the body is built in two sections, so gracefully is it streamlined from end to end. At the forward end the motor, an 85-h.p. 7-cylinder Canton Unne, is fitted, driving direct a propeller, the boss of which is covered by a semi-spherical cowl which effectively preserves the excellent lines of the body. Seated in a comfortably upholstered seat, the pilot controls the machine in its three dimensions of altitude, balance, and direction, by a hand-wheel, mounted on a pivoted column, and by foot pedals. On French built Breguets the warping of the planes is operated by rocking the vertical column laterally. On this point it is evident that the designers of the British Breguets have different ideas, for the plane warping on the biplane exhibited at Olympia is effected by means of the foot pedals. The hand-wheel rotates laterally, and is used to steer the biplane in a manner exactly similar to that of a car. The machine is made to rise or descend by rocking the column to and fro.

The landing gear is of a type by itself, since no other aeroplanes are, to our knowledge, fitted with an undercarriage that resembles it in the least. At rest the main weight of the machine is supported by two large diameter tyred-wheels, which are connected to the body by a pair of tubular oleo-pneumatic springs. Some part of the main weight is further taken by another pair of wheels in front of a much less track, which are jointed to a laminated cross spring bolted laterally across a tubular strut which extends downwards from the extreme nose of the body. These two front wheels are so designed that they pivot in conjunction with the rudder, and in this manner the machine may be effectively steered over the ground at slow speeds.

The planes are built about single tubular steel spars, which are universally jointed to the body. Over them fit the wooden I-section ribs, and they would be free to revolve around the spars were they not kept in position by steel leaf springs. These springs are so arranged that the faster the machine is driven through the air the less incident the ribs, and consequently the planes, become to the direction of the air flow. Owing to this system of plane conduction, which is fully patented, by the way, the machine is rendered unusually stable and at the same time is given a remarkably wide speed range.

Flight, September 6, 1913.

The Maidenhead Smash.

IT was tragical that after his success in the Speed Contest at Hendon on Saturday Debussy should have met with disaster later in the afternoon when taking the machine across to Farnborough. He started from Hendon on the Breguet with Mr. H. de Havilland, who only recently qualified for his brevet, and Mr. R. G. Crouch, of the Breguet Co., as passengers, at about half-past five and all went well until over Maidenhead, when the engine began to give trouble, subsequently found to be due to a broken exhaust-valve. As the engine stopped, the pilot apparently tried to plane down into a field near Bray, but from a height of 60 ft. the machine, after flattening out, dived into a field of mangolds. All three occupants were seriously injured, Mr. Debussy sustaining concussion of the brain and a bad sprain of the right ankle, Mr. de Havilland had his left arm fractured, while Mr. Crouch had his right leg broken, both the latter being also cut and bruised a good deal.

Flight, December 13, 1913.

THE STANDS AT THE PARIS AERO SHOW.

BREGUET.

The Breguet firm are showing on their stand one complete hydro-aeroplane with a large central float and two smaller ones situated about half-way along the main planes. Between the two front members of the chassis is mounted a strong headlight which derives its current from a "Radios" dynamo. In addition is shown a fuselage which has been left uncovered for the purpose of showing the new construction, which appears to be a great improvement on that employed in earlier machines. A wireless transmitting apparatus is fitted in front of the observer's seat, where is mounted on a small writing desk the telegraph key and a writing pad. One is inclined to think that the use of the latter would be somewhat hampered by the vibration of the machine when in flight, as the table is not sprung in any way.

Flight, December 27, 1913.

THE PARIS AERO SALON - 1913.

BREGUET.

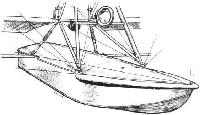

The first impression one receives of the Breguet hydro-biplane exhibited is one of strength and power, and a closer inspection confirms the correctness of this impression. In its general lines this machine resembles the previous Breguet hydros., but an examination of the constructional details soon reveals numerous improvements which should almost totally rectify most of the points that met with adverse criticism in earlier machines of this make.

The fuselage, which is still built of steel practically throughout, is constructed on a quite different and greatly improved principle. It will be remembered that in the earlier machines the rear portion of the fuselage consisted of a single steel tube stiffened with wire bracing which, whilst probably perfectly safe as far as bending stresses are concerned, could not be all that was to be desired for torsional strains. In the present machine this single tube has been supplanted by four thinner steel tubes forming a girder in the more orthodox way with struts and cross members and diagonal wire bracing. On this steel structure are mounted wooden distance pieces connected by longitudinal stringers, which gives the fuselage its streamlined form, the whole being afterwards covered with fabric. The two seats are arranged tandem fashion, the pilot occupying the front one. In front of him are the controls which consist of a rotatable handwheel for steering and elevation and descent. A foot-bar actuates the ailerons, with which one is pleased to note that this machine is fitted. Another improvement has been effected in the wing construction, as the flexible mounting of the ribs on the tubular spars has been discarded. One cannot help wondering, however, why M. Breguet does not go a step further and employ two rows of struts, which method of construction would increase the strength immensely and more than compensate for the extra weight and head resistance of a few extra struts. However, a diagram displayed on the stand shows a loading test, which appears to have proved that the new wing construction possesses ample strength for any practical purpose.

The machine is supported on the water by a big central float and two smaller ones under the first pair of inter-plane struts. The centre float is attached to the fuselage by four steel tubes, of which the rear pair have coil springs introduced in them, while the front pair forms a swivelling joint with the float, thus providing springing of the rear portion of the main float. A small tail float protects the tail planes against contact with the water. The engine - a 130 h.p. Salmson radial water-cooled motor - is mounted in the nose of the fuselage on steel bearers, which are further strengthened by two tubes running up to the upper ends of the two inner plane struts. The radiator, which has been given a shape resembling that of a wing section, is mounted in the place usually occupied by the centre part of the upper plane, a position which ought to combine the advantages of little head resistance and effective cooling.

In order to facilitate alighting in the dark, a strong headlight has been fitted on a transverse tube between the two front chassis struts. The current for this headlight is furnished by a "Radios" dynamo.

The tail planes are of the usual Breguet cruciform type, and are attached to the fuselage by means of a universal joint. A very large tail fin runs along the top of the fuselage from the passenger's seat back to the tail. The object of this fin, which is not fitted on the land machines, is, no doubt, to balance the considerable side area of the central float. The front portion of the fuselage is covered with aluminium, which is fitted very nicely round the engine cylinders, of which only the upper part projects outside the aluminium.

The rear part of the fuselage is covered in the usual way with fabric applied to the longitudinal stringers which give the fuselage the streamline form.

The uncovered fuselage shown is of a similar construction to that of the hydro., and is interesting chiefly on account of the wireless apparatus with which it is fitted. The key of the transmitter is mounted on a small table in front of the observer, and the practical demonstration of the wireless given at the Show never fails to attract a great crowd of interested onlookers, as the hissing of the sparks can be heard distinctly to the farthest corner of the Grand Palais. The wireless installation has been carried out by the Societe Francaise Radio-Electrique. The output of the transmitter is 750 watts, and the frequency is 1,500 periods. It has a range of 200 kiloms., and the total weight is 47 kilogs.

The workmanship in the complete machine as well as in the skeleton fuselage is very good, although no attempt has been made to provide a highly polished "show finish."

Flight, November 19, 1915.

CONSTRUCTIONAL DETAILS.-XI.

<...>

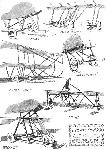

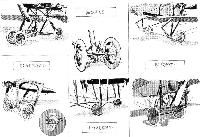

Yet a different form of undercarriage was that of the Breguet biplanes, which was of the four-wheeled variety, as shown in one of the accompanying sketches. The main load is taken by two wheels mounted on a tubular axle, which is, in turn, supported on a pair of telescopic steel tubes with which are incorporated coil springs.

Another pair of wheels is mounted well out in front for the protection of the propeller and to prevent the machine from turning over on its nose in a rough landing. In order to facilitate steering on the ground at low speeds these front wheels are so mounted that their axle can oscillate in a vertical as well as in a horizontal plane. The detail sketch will help to make the exact method clear.

The Breguet chassis as well as the whole machine was, it may be recollected, made entirely of steel, the tubes, in the case of the undercarriage, being given an . approximate streamline form by means of aluminium casings.

<...>

Показать полностью