А.Шепс Самолеты Первой мировой войны. Страны Антанты

Вдохновленный полетом Луи Блерио, французский предприниматель Арман Депердюссен построил свой первый самолет. Самолет имел прогрессивную конструкцию, был дешев и прост. В том же году началось его серийное производство. Хотя понятие "серийное производство" в данном случае было довольно относительным. Машины отличались как конструктивно, так и типами установленных двигателей. Монтировались ротативные "Гномы" и "Клерже", звездообразные, 3-цилиндровые "Анзани" и австрийские, рядные, жидкостного охлаждения "Австро-Даймлер".

В конце 1911 года машина, получившая обозначение Депердюссен тип В, стала двухместной. В 1913 году были попытки создать поплавковый вариант типа В. Но, кроме успеха гоночного поплавкового "Депердюссена", участвовавшего в гонках на кубок Шнейдера (пилот М. Прево), здесь отметить более нечего.

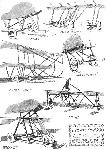

Депердюссен тип В - расчалочный моноплан. Фюзеляж имел деревянную конструкцию и оканчивался полотном в задней части. Рама крепления двигателя изготавливалась из стальных труб. Вокруг мотора фюзеляж обшивался алюминиевым листом. В районе пилотской кабины обшивка выполнялась из фанеры. Фанерными было и выпуклое дно кабины. Крыло самолета -двухлонжеронное, деревянной конструкции, обтягивалось полотном и крепилось системой растяжек к "кабану" и стойкам шасси. Управление по крену осуществлялось перекашиванием задней кромки крыла. Оперение состояло из треугольного стабилизатора, имеющего несущий профиль, и киля. Рули высоты и направления прямоугольные, симметричного профиля. Вся конструкция изготавливалась из дерева, обтягивалась полотном и крепилась растяжками. Система управления очень простая, от штурвала управления и педалей. Шасси жесткой конструкции, с противокапотажной лыжей из ясеневого бруса и костылем в хвостовой части фюзеляжа.

Двигатель в основном 7-цилиндровый, воздушного охлаждения, ротативный, звездообразный, "Гном" мощностью от 50 до 80 л. с, с тянущим винтом типа "Интеграл".

Машина использовалась в начальный период войны как разведчик, но быстро была заменена более надежными машинами фирмы "Фарман". До середины 1915 года оставшиеся "депердюссены" использовались в учебных подразделениях.

Размах, м 8,75

Длина, м 7,65

Высота, м 2,55

Площадь крыла, кв.м 14,25

Сухой вес, кг 225

Взлетный вес, кг 355

Двигатель: "Гном"

мощность, л. с. 50

Скорость максимальная, км/ч 90

Экипаж, чел. 1-2

Показать полностью

L.Opdyke French Aeroplanes Before the Great War (Schiffer)

Deleted by request of (c)Schiffer Publishing

Type B. 1910-1911: A 2-seater similar to the Type C, with small triangular fin and rectangular rudder, and a 50 hp Gnome.

In May 1911 Deperdussin took out a patent on an engine arrangement featuring 2-100 hp Gnomes, one on each side of the front fuselage, combining in a gearbox to drive 2 contra-rotating tractor propellers. A photograph shows the device mounted on an airframe - it may not have been completed. The series continued:

Type C. 1911: This 1 - or 2-seater featured a long gently-curving fin attached to a rectangular rudder; 2 uprights still served as kingposts. The 70 hp Gnome was partly cowled. It also appeared with 2 pairs of undercarriage wheels.

(Span: 10.5 m; length to tailpost: 9 m; 70 hp Gnome)

Type D? a 2-seater.

(Span: 12.75 m; length (to tailpost): 10.5 m; 70 hp Austro-Daimler, 70 hp Panhard-Levassor, 100 hp Clerget, or 70/100 hp Gnome)

Type F? a 2-3-4-seater.

(Span: 15 m; length (to tailpost): 12 m; 70 or 100 hp Gnome)

Type Nardini. 1911: This 75 hp single-seater flown by and perhaps built for Nardini had deep cutouts at the wing-root trailing edges, and an angular extension forward at the wing-root leading edges. A rectangular cut-out in the fin allowed for movement of the one-piece elevator.

Type Concours Militaire. 1911: An Anzani-powered 3-seater similar to the Type Nardini, with a 2nd diagonal brace in the pylon structure. Another Type Militaire appeared at Reims in October 1911 with a Clerget rotary, and without the third pylon strut on each side.

Type Concours Militaire. 1911: A larger and heavier 3-place military machine with a 100 hp inline Clerget. The leading edge extensions were omitted, the pylon consisted of 2 parallel verticals only, and a fuel tank with rounded ends hung under the fuselage.

Type ?. June 1911: Vidart was flying a smaller single-seater with a 2-triangles pylon, and a curved fin.

2-Seat Tandem (year unknown): 3 designs, one with a 70 hp Gnome, one with a 50-60 hp Anzani, one with an 80 hp Anzani.

Type Meeting de Grenoble: Possibly a smoother version of Type B?

Type Militaire (year unknown): 2 single-seater designs, one with a 50 hp Gnome, the other with a 80 hp Anzani.

Type Grand Prix d'Anjou. 1912: A 2-seater with separate cockpits, a 2-triangle pylon, scalloped trailing edges, large wing-root cut-outs, and wheels of large diameter. The angular rudder carried the number 22.

Type ?. 1912: G Busson flew this single-seater at Issy. It had the 2-triangles pylon, scalloped trailing edges, and a swelling aluminum coaming that almost surrounded the pilot.

Type Militaire. 1912: A 3-place machine, perhaps the same as Type Militaire 1911, with the seats tandem in a wide bathtub of a coaming. The fin was small and triangular, the rudder a simple rectangle. The pylon was formed of a pair of triple struts.

(Span: 12.5 m; length: 8.8 m; loaded weight: 930 kg; speed: 110 kmh; 100 hp Gnome)

Type ?. 1912: a 2-place machine. The pilot and passenger sat in 2 separated cockpits, the wing-roots were cut out, and the trailing edges scalloped. (Perhaps Type M? Perhaps for Military?)

(Span: 10.63 m; length: 7.3 m; loaded weight: 550 kg; speed: 105 kmh; 70 hp Gnome).

Monocoque. 80 hp Gnome.

Type E. Ecole. 1912: a single-seater, the long box fuselage uncovered on top, a triangular fin and square rudder with rectangular cut-out for elevator movement, scalloped trailing edges, and a 2-triangles pylon. A similar racing version appeared with flatter airfoil section.

(Span: 8.85 m; length: 7.3 m; loaded weight: 300 kg; speed: 80 kmh; 30 hp Anzani)

Deperdussin de Marc Pourpe. 1914: Similar in its forward coaming to Busson's of 1912, but without scalloped training edges. The twin triangles of the pylon were very high for extra strength in inverted flight, and curved at the top; a fingernail-shaped cowl covered the top of the Gnome. A photo shows Silvio Petrossi, Italian stunt pilot, in a similar machine on the Christofferson wooden runway at Ocean Beach, California, in 1915.

Показать полностью

Журнал Flight

Flight, August 19, 1911.

THE DEPERDUSSIN MONOPLANE.

SINCE the first appearance of their product, which gave all those who were fortunate enough to be present at the last Salon Aeronautique in Paris an impression of neatness in design and workmanlike construction, the Maison Deperdussin has characterised its existence in the aviation industry by a commercial vigour that few have equalled and none exceeded.

They first of all designed a good machine, and then employed good pilots to fly them. They established flying schools on the best aerodromes of France, Belgium and England, and lately have done their best to popularise their models by entering them in all the big competitions, and by putting them on the market at a very alluring price.

From the performances achieved by the Deperdussins in the Circuits of Europe and Britain, and from the fact that it was a "first reserve" in the Gordon-Bennett Race, may be judged their cross-country and speed qualities.

The fuselage under its fabric covering is of the ordinary box-girder type, but is peculiar in that the top and bottom longitudinals are parallel from engine to rudder, while to afford more accommodation for engine mounting, tanks, and pilot, a semi-cylindrical well is provided under the front section, consisting of a light wooden framework covered inside and outside with veneer.

The fuselage is pretty to the eye, but is so shallow that the pilot sits on it rather than in it.

Another unique feature is the method of attaching the cross-bracing wires to the small aluminium sockets accommodating the struts.

The landing carriage is a neat and light wheel and skid combination, the axle being sprung by the conventional radius-rods and elastic shock-absorbers. The cross-members of the chassis are of steel tubing, and it is noticeable that the four main struts are covered with canvas. Very little wire bracing is used, but rigidity is given to the structure by two wooden diagonal struts in compression.

These struts extend in front of the chassis proper, and are curved up in hockey-stick fashion to form a protection for the propeller.

Shocks occasioned by rough landings are distributed over as much fuselage area as possible by means of stranded cables, which pass under the well of the body and over grooves at the top of the chassis-struts, thus forming a kind of cradle.

The method of mounting the motor is, without doubt, neat in the extreme. A sheet-steel cap fits over the front end of the fuselage, and to this is screwed in the usual manner that flat plate keyed to the Gnome crank-shaft which would form the fly-wheel if the cylinders were kept stationary. Aluminium inspection doors are provided for access to the magneto, & c, and an aluminium dome is arranged over the top of the motor, to prevent the spray of oil from the exhaust reaching the pilot.

The weight of the wings when the machine is at rest is supported by two struts erected vertically from the front of the main body in order, at the same time, to strengthen the wings against end stresses when in flight. They are of ample proportions near the base, as they also serve to accommodate the front wing spar.

The construction of the wings follows conventional lines, with the exception that the trailing edge is laced to the ribs and is allowed a small degree of flexibility. Aluminium plates are fastened on the under surface of the wings against the main body, to protect the fabric from becoming saturated with oil. Their brownish tint is due to the treatment of the fabric with "Emaillite," a preparation that renders it weather and oil proof, and endows it with exceptional tautness. This same varnish is also employed to proof the main frame covering and the tail planes.

The control is extremely neat, and the movements are more or less natural. A wheel, mounted in the centre of an inverted U-shaped sweep of wood, is rotated for the correction of lateral balance, while a to-and-fro motion controls the elevation. Steering is effected by the usual form of pivoted foot-lever.

The wires from the warping-wheel are carried to a rock-lever on the rear cross-member of the chassis, and after passing over pulleys on the skids, each wire branches into three. These are connected to clips on the rear wing spar. By rotating the wheel to the left, therefore, the whole of the rear spar of the right wing is pulled down, while the similar spar on the left wing rises a corresponding amount, and vice versa.

The combined oil and petrol tank is mounted in the front of the pilot between the two wooden masts, and gauges are fitted so that he is constantly acquainted with the state of his fuel supply. A small reserve petrol tank is arranged under the seat, and the fuel is fed under pressure to the main tank by a pump on the right of the pilot.

The passenger-carrying and school Deperdussin models have purely flat tail planes triangular in shape, but the racer, probably to render the machine more "lively" to the controls or to introduce greater internal strength, possesses a tail in which the upper surface is considerably cambered. This constitutes a lifting plane and contributes to a certain extent to the efficiency of the machine by actually doing work instead of being a solely directive organ.

Hinged to the rear of the tail plane is the rectangular elevator, while forward of the rudder extends a small vertical stabilising fin.

A neat skid, hinged in the centre and flexibly anchored at the top, protects the rear of the machine from ground contact.

Flight, August 26, 1911.

The Ventnor Flying Week.

FROM a flying point of view the Ventnor week was somewhat of a fiasco, as from one cause or another most of the machines which it had hoped would have taken part were put out of commission. Mr. Valentine, on the Deperdussin machine which he had flown from Brooklands, saved the situation by making a fine series of flights on the 17th inst. Rising from the Dean Farm on the Whitwell Road, he made quite a long trip over the Downs, and also circled round the town.

Flying from Ventnor to Brighton.

ON Monday last Mr. Valentine left Ventnor on his Deperdussin monoplane, and steered for Brighton. Arrived at "London-by-the-Sea," he first circled the Palace Pier and then landed safely at the Shoreham aerodrome.

A telegram handed in at Ventnor as Mr. Valentine left was not delivered at Brighton until some time after the aviator arrived.

Flight, December 16, 1911.

Flying at Night by Searchlight.

A CORRESPONDENT sends us the following interesting account of a night in America by Mr. George M. Dyott, a member and pilot of the Royal Aero Club :-

"The sensation of the week ending October 28 that the Nassau Aerodrome in New York was the ascent by night of two Englishmen, Mr. George Dyott, with Captain Hamilton as passenger, in a Deperdussin monoplane. With the aid of a powerful searchlight attached to the running gear of his aeroplane and connected by electric wires, Mr. Dyott flew all about the vicinity of the Nassau Aerodrome and landed without even straining a wire.

"The other machines had been in their hangars for some time, and all was a thick inky darkness when Mr. Dyott ended his remarkable flight. Captain Hamilton manipulated the searchlight and picked out a landing for Mr. Dyott near his hangar.

"Ths aeroplane presented a most remarkable appearance in the dark sky with the searchlight sending its rays in all directions. At times the light would be shut off, and except for the throbbing of the motor the location of the aeroplane could not be determined. As the monoplane came down from a height of 300 feet the searchlight was turned towards the ground, and the spectacle resembled a monster shooting star rushing earthward.

"Captain Hamilton, who has had much experience in aeronautics in England and France, declared the experiment to be a marked success, and that it would be but a short time before aeroplanes would be flying at night whenever occasion required.

"Mr. Dyott took his brevet at the Bleriot School of Aviation at Hendon last summer, and afterwards spent several weeks in France at the Deperdussin School of Aviation, from there he went to the magnificent works of the Deperdussin Company, and watched the building of the two fine machines which he and Captain Hamilton took with them to America.

"Mr. Dyott and Captain Hamilton left New York on November 1st for Mexico City, where they have arranged to fly for a month."

Flight, December 30, 1911.

PARIS AERO SHOW.

Deperdussin Monoplane.

IN order lo exhibit their four types of monoplanes most effectively, the Deperdussin firm went to the extent of engaging two stands for that purpose. On one stand, situated under the centre dome of the Grand Palais, were exhibited the 100-h.p. Gnome-engined three-seater monoplane and the 50-h.p. single-seater cross-country machine. At the further end of the Show was the other stand, on which the 35-h.p. Anzani-engined popular- and the 70-h.p. two-seater military-types were exhibited. Very little need bу said of these excellent machines, as, in the main, they do not differ from the Deperdussin monoplane, as has already been described in FLIGHT, and demonstrated practically in England by such pilots as W. H. Ewen, Lieut. Porte and Gordon Bell, and on the Continent by Such men as Prevost and Vedrines. The latter model - the 70-h.p. military monoplane, however, is a new one, but its only difference lies in the fact that passenger and pilot are arranged tandem fashion in the fuselage in such a way that the former is so far forward that he can obtain an excellent view of what is directly beneath the aeroplane by glancing over the front of the wings. The importance of this feature for military requirements is readily apparent. Both in design and workmanship the machines are of the highest order, and reflect great credit on the Deperdussin firm, and more particularly on the firm's designer and works manager, M. Bechereau.

Principal dimensions, &c.:-

School type-

Length 25 ft.; Weight 500 lbs.

Span 29 ,,; Speed 55 m.p.h.

Area 165 sq. ft.; Motor 35-h.p. Anzani.

Price L460.

Single-seater military-

Length 25 ft.

Span 29 ,,

Area 264 sq. ft.

Weight 550 lbs.

Speed 65 m.p.h.

Motor 50-h.p. Gnome.

Price L920.

Two-seater military-

Length 26 ft.

Span 36 ,,

Area 310 sq. ft.

Weight 924 lbs.

Speed 65 m.p.h.

Motor 70-h.p. Gnome.

Price L1,080.

Flight, April 20, 1912.

AIR EDDIES.

Signor Sabelli, who has been doing a lot of good flying at Brooklands recently, is really one of the best pilots our English schools have turned out for many a long day. His machine, too, a 28-h.p. Anzani-Deperdussin, must come in for a share of the honours, for never before, to our recollection, have we seen such a low-powered machine remain in the air for such a long time as when Sabelli kept circling over Brookland's track at a height of 1,500 ft. for 1 hr. 8 m. on Sunday last. Pierre Prier, when he was with Bleriot's at Hendon, kept up for over an hour on an Anzani-engined machine, but I don't seem to think he beat Sabelli's time.

Flight, April 27, 1912.

AIR EDDIES.

Mr. G. M. Dyott, who, as recorded in these columns from time to time, has been doing a lot of excellent exhibition work out in America, returned to England on Sunday last on the "Oceanic." He did not, however, remain in England long, for on the following evening he set off for Paris, where he intends to spend the week in selecting and obtaining delivery of a couple of machines to take back with him to America, for his second season's work. This he figures on getting done in time to sail for America to-day.

Dyott reminded me that after all he did fly at Yucatan, although the conditions were such that he had little desire to repeat the performance. The ground was so badly situated that had there not been a forty-mile-an-hour wind blowing at the lime it would have been impossible to get away from it. Even at that, flying head to wind, it was an extremely risky undertaking. Landing there, too, was little better, and Dyott had to arrange for sand to be put down on the ground in order to bring the machine quickly to a standstill.

Flight, January 18, 1913.

SOME EXPERIENCES OF FLYING IN CENTRAL AMERICA.

By G. M. DYOTT.

[ROUGHLY a year ago it will be remembered that Mr. G. M. Dyott and the late Capt. Patrick Hamilton bought two Deperdussin monoplanes, a 60-h.p. two-seater and a 28-h.p. single, and took them over to the United States to complete a tour of exhibition flying. After a period of successful flying at the Nassau Boulevard and other aerodromes, they went down South to fill an engagement in Mexico. Below Mr. Dyott relates some of his impressions of flying in that district].

Taking it on the whole, I did not find flying down in Central America anywhere nearly so comfortable as flying in the North. In all the hot countries in which I have flown, the calmest and most inspiring mornings, I soon learned were the most treacherous, and, in fact, almost dangerous. There might not be a breath of air stirring, yet the air would be riddled with heat eddies and down trends in every direction. Add to this a very gentle wind, and you have the only condition that could be worse, as this caused whirlwinds' of a local character, which would swing even a moderately fast machine 30 or 40 degrees out of its course. Being caught in one of these whirlwinds I found the best way out was to dive the machine with motor stopped, at the same time turning head on to wind, if that were possible. A very curious condition of things existed in the Valley of Mexico. The valley is circular and surrounded on all sides by high mountains. At certain times during the day I found that I could make a complete circle one mile in diameter, having a following wind the whole way round. Up to 1,000 ft. the air would be steady, above that impossible.

Towards 4 p.m. on a cloudless day the heat eddies became less local in character, with the result that the entire atmosphere seemed to be rising. On the other hand a partly clouded afternoon was always bad, and the effect of passing from sunshine to shadow, or vice versa, was always accompanied by a sudden rise or fall of the machine. Another observation I made was that, while heat eddies would rise vertically in an absolute calm, a wind would incline them over at an angle, and under these conditions, flying with the wind, the disturbances would be more noticeable than flying against it. It seemed that the small local whirlwinds, dust devils as they were called, would originate about one of these air chimneys. One day I was flying near Puebla, 8,000 ft. above sea-level, with my 60-h.p. passenger-carrying Deperdussin. For several days I had been flying there, carrying passengers with success, when, about seven days after my arrival, I had an extraordinary experience. I had taken up a passenger, and after flying with him some 20 minutes, started to return to the aerodrome. Somehow the machine seemed to lose power, in spite of the fact that the speed indicator of my motor gave the proper number of revolutions per minute. A row of tall trees was between me and the aerodrome, and I was surprised to find myself almost, as I thought, on top of them. Naturally I elevated, but with no effect except the lowering of the tail. I cleared the trees by about 70 ft. or 80 ft., but at the same time a gust of wind caught me and the machine heeled over to one side. I warped immediately, but the warp seemed to have not the slightest effect. We got so far over that my passenger started to crawl up the higher wing. Then I nosed the machine downwards suddenly, a manoeuvre which sent him flying back into his seat. Finally we landed safely.

This incident set me thinking, and I did not fly for a couple of days pending some explanation. What was wrong I could not conceive. The controls had not jammed and I thought it impossible for a remousto have such an effect upon a machine in good flying condition. Here again the machine was apparently in good condition, for I had flown with her every day for a week, carrying passengers without the slightest trouble. The speed indicator was conclusive proof that the motor was not at fault; so what was wrong? After thinking the matter over for some time, the final analysis showed me that the only difference between this and my other flights was that it had been made after the sun had gone behind the mountains, a trifling difference to be sure, yet nevertheless the keynote of the whole situation. Subsequently I tried the machine in straight away flights with a passenger, when the sun was shining, when it was cloudy, and when it had sunk below the horizon. To my great satisfaction I found that in bright sunlight the machine would lift easily; but once let the sun get behind the clouds, passenger carrying was only carried out by working the machine above the safety limit.

Having determined this fact, the next thing was to experiment with the little three-cylinder Anzani Deperdussin single seater we had out there, which my friend, the late Capt. Hamilton, had not yet attempted to fly, owing to the aerodrome being so high above sea-level. Here the same phenomenon was apparent. The machine would not fly after 5 p.m. Unlike the two-seater it could fly in the morning when the heat eddies were still local in their effect, whereas the two-seater could not carry a passenger until the eddies had become uniform over the whole field.

To fly the small Deperdussin was a source of considerable interest. A run would be made over the ground, tail well in the air, making no attempt to get off. The first heat eddy encountered would lift the machine bodily off the ground like a balloon, some 30 or 40 feet. A slight effort would be made to check the rise until the disturbance had been passed through, then the elevator would be returned to a position of gentle descent, allowing the machine to gradually lose altitude until the next air "chimney" was encountered, when the same performance would be repeated. In this manner altitude could be gained according to the frequency of the heat eddies encountered, it being quite possible to get up to 1,000 ft. in 15 minutes. Towards three and four o'clock in the afternoon the periods of lift would not be as pronounced, as the whole atmosphere would then be rising. The minute the sun went behind the mountains flying was impossible unless the pilot weighed less than 130 lbs. Later observations showed that when the buzzards were soaring well up in the air the small machine would fly and the two-seater carry a passenger. If these birds were flying low and had to do much flapping, the air was only good enough for the two-seater to fly with the pilot alone. This point was soon to be brought home both to poor Capt. Hamilton and myself rather forcibly. We had been invited to pay a visit to the Country Club, some 16 miles from Mexico City. I suggested that we both go over on the two-seater, then, if we were detained till sunset I could fly back alone. Hamilton was rather anxious to put the little machine through its paces, and he decided to make the attempt on that, while I flew over alone on the two-seater. We set out at 2.30 p.m., the little Deperdussin climbing easily and well, and we both arrived safely. After a game of tennis, and some tea, it began to cloud over, and it was 5 before Hamilton started back. I rather urged him not to make the attempt, but he thought he could manage it, so off he went, disappearing over some high trees with 80 ft. or so to spare. He thought he could not clear them, and was trying to force the machine up, when a side gust caught him, turned the monoplane completely over, and it described a vol plane on its back, Hamilton with his knees under the control bridge, still hanging on inside. It landed, breaking everything but the wheels and Hamilton, who then dropped out unhurt - a marvellous escape.

It was an expensive break, but it served to confirm absolutely what we had already supposed, and we were obliged to chalk it up to experience, our fund of which was increasing much more rapidly than our banking account.

While speaking of heat eddies, I might mention an incident at Santa Rita, where I flew over a forest fire of considerable magnitude. Above the smoke region the hot air rose very rapidly, and as soon as the machine entered it, it would rise almost vertically. The first experience came so suddenly and with such alarming force that I felt sure something must have gone wrong, and I was not long in getting back to earth to think the matter over, a habit of mine. It was some time before I could persuade myself to try it again; however, when I did, the effect was the same, and once the cause of it was definitely determined it was rather a source of amusement to me and spectacular for the onlookers.

At this same place I had the disagreeable experience of being lost for an hour and a half. Outside of a few Indian huts and their occupants there was not a single soul within a radius of 30 miles. My mechanics and I ran the machines off two flat railway cars early that morning, and we spent a hard day erecting them in the hot sun. They were ready for action at four o'clock in the afternoon, and the machines were run out on to our improvised aerodrome, a patch some 900 ft. by 500 ft. which we had had burnt off and which was as black as a cinder. To be sure I could see it very plainly from above, so I took no particular care to take any bearings, but here I was mistaken as it turned out afterwards. I started off for the mountains and 15 minutes later by my clock swerved round and headed back again, but where was that little black patch of ground? Nowhere to be seen. Look as I would there was absolutely no trace of it. Imagine my feelings flying over a wild uninhabited country, tropical forests, jungles and swamps, everything but a good landing ground. The next thing I knew was the sight of the ocean looming up ahead of me, and as I knew I had started from a point about 50 miles inland, I turned back again and headed for Mount Orizaba. Back I went, making repeated vol planes to get a better look at the country below, my anxiety increasing at every revolution of the propeller. At last, in the gathering darkness, I caught sight of the flicker of a flame, and, making a beeline for it, found to my great satisfaction that it was our encampment. That night, as I lay awake under the wings of the good old Dep., I wondered what might have happened had I not caught sight of that flame. Once more I mentally chalked up a few figures to my fund of experience, reflecting that things as viewed from above do not necessarily appear as they do from the ground.

On one ground in Yucatan I could not fly unless at least 10 miles an hour of wind were blowing, as the field was too small to lift from without a head wind. Returning to earth was still more ticklish an operation, and I conceived the idea of spreading sand along the far end. It worked excellently, and pulled the two-seater up almost at once.

Flying out there late on in the day a curious feeling of drowsiness very often came over me. The peaceful surroundings, the dim light, the steady hum of the motor, and the uniform rush of the air seemed to induce a semi-hypnotic state which it was difficult to shake off. For this reason I never flew unless I was in good physical condition and had had plenty of rest.

Flight, August 23, 1913.

ARE THESE WING-SPARS BENDING?

WE published last week a very remarkable photograph of Mr. N. Spratt flying the 60-h.p. Deperdussin monoplane in a speed handicap at Hendon. The central portion of that picture we reproduce herewith, and on it we have drawn a series of converging lines. The point of interest is to know whether the photograph is evidence of bending in the wing-spars, or is merely photographic distortion.

The photograph was taken with a focal plane shutter and a Goerz lens in first-class condition. It was a swung photograph, that is to say the operator followed the flight of the machine, which accounts for the background being blurred. That the swinging was successful is obvious from the clearness of the detail in the engine and other small parts. The aperture was probably about F.5, and the exposure probably about one-thousandth of a second.

Ordinarily, the distortion that one obtains with a focal plane shutter, when taking a picture of a racing motor car with a fixed camera, results in an elliptical wheel. Similar distortion in respect to a flying machine would have put the wings on the slant, so that one wing tip would have appeared much further forward than the other. Again, if the distortion of the near wing tip were regarded as due to lack of focus, one would expect the outline to spread itself over the plate, so as to make the front edge concave to the direction of flight instead of convex, as it appears at present.

Actually, when the machine is at rest, the wing spars are straight, and the front edge is straight. There is no dihedral angle. In the photograph the front edge appears curved in both wings, and the row of attachments by which the upper wires are fastened to the spars also lie in a curved line.

The photograph was taken from a pylon and the near wing tip is within about three yards of the lens. The wing tips are more than an inch from the edge of the negative, so that the machine may be regarded as thoroughly in the centre of the plate. At the moment the photograph was taken, the pilot was commencing to recover from his bank, and judging by the position of his hands on the control wheel, he had just warped the near wing tip down in order to increase its angle of incidence.

If the curvature in the photograph represents bending in the wing, the amount is probably about 3 or 4 ins. at the tip on the actual machine, allowing for the difference in scale. We should like to hear the views of constructors, pilots, and photographic experts on the points raised in connection with the picture.

Flight, April 30, 1915.

EDDIES.

Perhaps few of the captures made by the German army have been hailed with greater satisfaction in German aeronautical circles than was the occupation of the Rheims aviation centre in the early part of the war. Their aviation journals have certainly not failed to make the most of the coup by telling credulous readers of the rich booty in the way of engines and modern aeroplanes, of both the mono- and biplane type, which was raked in. Unfortunately - for the German journals - the photographs illustrating these voluble accounts fail to show a single up-to-date aeroplane. In one of the accompanying photographs a German officer is seen standing on the wings of a partly wrecked Deperdussin monoplane, in an attitude suggestive of a gladiator of old, appealing to an appreciative audience for the sign "thumbs up" or "thumbs down." The pose, however, loses much of its apparently intended effect when one looks a little closer at the machine, which will be readily recognised as being of the type used in this country at the time of the first Circuit of Britain. Although these monoplanes were excellent machines in their day, the capture of a few of them by the Germans need not be greatly lamented, since they could not have been of much service for war purposes. One cannot help thinking how much this officer's pose would have gained in dignity, had his booted feet been resting on the wings of a modern Dep. monocoque, or even one of the type similar to the monoplane on which Commander Porte did such excellent flying at Hendon in the pre-war days.

Показать полностью