Журнал Flight

Flight, July 30, 1910

FROM BOURNEMOUTH TO THE NEW FOREST BY AEROPLANE.

THAT within about two years from the first public flight in the world, men should be flying home after fulfilling an engagement at an aviation meeting, instead of elaborately packing up their machines and carting by road or despatching by train, is the most eloquent demonstration it is possible to adduce of the phenomenal progress achieved in the conquest of the air in so short a period. That such a feat should also pass almost unnoticed in the Press is a still further proof of the advances made, rendering such a journey as accepted quite in the ordinary course of daily events. Yet such is the position to-day, whilst it is but three or four months back that there was a big wave of lamentations and sneers that Great Britain was all behind again, and had not a real flyer to her name! After the Bournemouth aviation week had been closed, all haste was made by most of the men who had taken part to forward their machines to the next point of demonstration. Mr. Armstrong Drexel and Mr. W. E. McArdle, who have founded such a fine school of flying at Beaulieu, in Hampshire, however, determined to return home by way of the air, in like manner to the arrival at the Southbourne aerodrome by McArdle a week previously. Then only one Bleriot was available. For the return the two-seated Bleriot of Morane had also been added to their fleet by the firm, so that Drexel was this time able to take a mount as well as his partner. And so it came about that, without fuss or blowing of trumpets, they both set out on Tuesday evening of last week and accomplished what three years ago would have secured for them pages of laudatory notice in practically every newspaper in the world. It is still a feat to be supremely proud of, more particularly from the fact that Drexel took with him Mr. Harry Delacombe, the well-known newspaper correspondent, who is so keenly interested in bringing home to the naval and military authorities the practical and national purposes to which the aeroplane can be put. He has clearly demonstrated the ease with which notes and sketches can be made in writing by a passenger that would in the hands of a General prove of immeasurable value. To this end we reproduce his original notes made during the flight with Drexel. Each of these slips of an ordinary note-book were signed in advance by Mr. Spottiswood and others as blank pages, and from these the announcement of the journey was made in the Morning Post the next morning. Supplementing on the following day the bare facts of the flight, the following details of his experience appeared on Thursday, which are of such historical interest that we reproduce them in full, as well as a special account from the pen of Mr. McArdle of his little trip, in which he was so encircled in clouds and mist that he lost his way, and descended at last at Fordingbridge by reason of petrol shortage. It is thus that Mr. Delacombe describes his trip :-

"When we reached the aerodrome at 4.30 there was a nasty gusty wind blowing, and Mr. McArdle (Mr. Drexel's partner in the Beaulieu Aviation School), considering the conditions quite unsuitable for our attempt to fly over the sea and forest to Beaulieu, suggested postponing the start, hoping the wind might drop. Mr. Drexel thought, on the contrary, that it might become more blustery, and was most anxious to be off. It had been arranged that he and I in the double-seated Bleriot monoplane should start first, followed after a few minutes by Mr. McArdle on the single-seater, as the latter, with only one person to carry, was sure to travel the faster, and probably overtake us en route. There was also the possibility that either machine might drop into the sea (where there was no cordon of motor boats and steam yachts as arranged for the over-sea flights to the Needles last week), be perceived by the other, and perhaps be reached sooner from the definite information it could carry to land. As no change in the weather appeared likely at 6 p.m., we decided to set out. Mr. Drexel thought our safety lay in rising about 1,000 ft. before making the journey, and said it would probably be necessary to encircle the aerodrome two or three times to attain this altitude. A single circuit only enabled us to climb to 350 ft. So round we went again, rising rapidly as we faced the wind, but having great difficulty in keeping our height with the wind astern, the "lift" being enormously decreased and the position of our machine becoming somewhat like that of a kangaroo sitting on its tail. Mr. Drexel's idea in flying high was: first, the hope of escaping gusts and finding a steadier wind than prevailed below; and, secondly, if the motor should perchance stop, the better chance of gliding down either into one of the few small open spaces among the almost endless trees, or else turning about and planning down for the sea, where we had a far better chance than if descending involuntarily among trees, houses, or marshy land.

A Bird's-Eye View.

"Satisfied at last as to our height, he steered direct from Hengistbury Head towards the Needles, which seemed almost below us, though really some two miles distant. We could see Mr. Loraine's aeroplane with people surrounding it very distinctly on the high land over Alum Bay, and as we turned to the left over the promontory of Hurst Castle the view up the Solent as far as Southampton on the left and Cowes on the right was clearly mapped out underneath. At this time the wind had been dead astern, and Mr. Drexel had a hard tussle to preserve our altitude to his liking. Once, when he asked me if I could see anything of 'Mac' following, I turned round, distinguished the aerodrome, but saw no machine aloft. I did, however, see that our tail, instead of being horizontal, was horribly out of the level, and momentary thoughts of head resistance and a backward fall flashed through my mind. The placid smile and cool behaviour of my companion would, however, have reassured the most timid, and I was happy in the sensation of unlimited power conveyed by the regular throbbing of the motor and the mighty beats of our propeller-blades as we soared steadily ahead. Suddenly I heard 'Look! there's old Beaulieu!' Following the direction in which he was gazing, I could distinguish nothing but apparently black forest. A winding road and a peculiar shaped patch of water, however, I guessed were his landing marks, and it was with a feeling rather of regret that I saw we were turning sharply to the left, and leaving the friendly sea behind, to fly over country which, from a height of 1,500 ft., looked everywhere literally unapproachable for our frail craft. With a nudge and a grin Drexel put forward the cloche, and we headed downwards till he was almost standing on his foot tiller, and my feet were pressed against the front part of our little cockpit. Then at last I realized how much we had been leaning backwards during the flight, for we were rushing through the air at about 80 miles an hour at a bigger angle probably than we had previously assumed in the other direction.

"At once I could make out the road and hangars of the Aviation School to our right, and could see a small crowd of black dots running out on what I had just before mistaken for another patch of murky forest. In three minutes we had glided more than 1,500 ft. downwards, and then came the end of my novel experience, for we landed, and were surrounded by friends, to one of whom I gave the notes I had scribbled on leaves of my pocket-book, signed as blank pages by other friends just before we left the ground at Southbourne.

Possibilities of Aeroplane Reconnoitring.

"Throughout the run I was entrusted with a rubber ball, by squeezing which a constant pressure is maintained in the feed, and I also constantly learnt forward and peeped over our bows to keep Drexel informed of our whereabouts. These minor duties, however, did not prevent me from carrying out my cherished hope of proving the practicability of writing legibly during a flight, and my scribbled log of the trip is sufficiently legible to prove beyond any question that trained officers or men could easily do surveying work of the utmost importance and utility at far greater heights than we reached, for with binoculars and a clearer atmosphere I could have distinguished every necessary detail, and transmitted my impressions to paper with explanatory notes in perfect comfort by stooping below the backwash of our propeller and the ordinary rush of air as we raced along. We saw Mr. McArdk flying about 800 ft. over the Beaulieu Aviation School five minutes after our descent, but he passed out of sight in the direction of Lyndhurst. As he did not reappear after an hour's interval, and we knew his petrol supply at the start could only suffice for a flight of one hour and a half, we started off in motor cars to try and glean some news, fearing he might have been obliged to descend in the New Forest, a most risky undertaking. Although we made circles of gradually increasing radii, knocked up every house or cottage showing a light, and questioned everyone we met, we got no definite news until reaching Fordingbridge (from Downton, near Salisbury) at 3 a.m., when, with a sigh of relief, we learnt that he had landed safely in a cornfield at Stuckton, a mile away, at about 7.30 p.m., and that his machine, not much damaged, had been housed for the night in a neighbouring iron-foundry. Fagged out, hungry, and sleepy, Mr. Cecil Grace, who had been driving us ceaselessly since 8.30 p.m., turned his car for Beaulieu, 24 miles distant, and we all enjoyed a good sleep at last, after a somewhat arduous day and very anxious night. Mr. Drexel expressed his opinion yesterday that it would probably be hard to find a more unfavourable part of England for a cross-country flight than that from Southbourne to Beaulieu, especially burdened with a passenger. 'Where ignorance is bliss!' I need not further explain my enjoyment of the trip."

NOTES BY MR. DREXEL.

Mr. Drexel is a man of few words. He believes in action more. We managed nevertheless to obtain a few points from him of his impressions and his methods in connection with a trip of this character. The following are a few of his helpful hints :-

"The first most important discovery I made was that in crossing over water one appears to be much lower than really is the case. It is extraordinary the difference one estimates one has risen to and the exact height registered by the ' altitude finder.' The downward currents which are often encountered over the sea I fortunately only experienced once, and found it necessary in order to increase my altitude to at once turn into the teeth of the wind. My general impressions of the velocity of the wind was that it maintained, as near as I could judge, about 15 miles an hour. And the wind going in the same direction as I was, I had great difficulty in getting to what I consider a safe height, about 800 ft. in flying over water or across country, and, in order to arrive at that height, had twice to turn back near the Aerodrome and face the wind. Over Lymington I had some difficulty in finding Beaulieu owing to some clouds beneath us, but as soon as we had passed them by I immediately recognised our destination by a long white road and a lake near by. All the way over the sea for a good 15 miles I found it very difficult indeed to rise, but as soon as we were over Lymington we got a wind from the opposite direction, and rose without any trouble to 1,500 ft. As soon as we got to 1,000 ft. I felt much easier in my mind, as, personally, I never like to fly across country in England under 800 ft. At that height it seems to me one always has a fair chance it one's engine stops or starts miss-firing, if looking about and planing down on to clear ground, but anything under, unless the country is singularly free from trees and houses. I consider most dangerous, and does not give one a fair chance. There is no doubt in my mind at all that aeroplanes will become the accepted agents for the purpose of scouting in warfare. I was particularly struck with the view we got of the Solent and the land on each side, and although it was a very misty day, we could see a very long way. But coming back to the point before mentioned, my own thought after the flight was that the higher you are the safer it is in cross-country flying."

MR. McARDLE'S EXPERIENCES.

Mr. McArdle's account of his extraordinary experiences during his homeward flight from Bournemouth is as follows: -

"Tuesday, July 19th, three days after the close of the first International aviation week held at Bournemouth, I decided to fly our Bleriot monoplane - the same machine which I flew to Bournemouth the day previous to the opening of the meeting - back to Beaulieu to the school ground. The distance as the crow flies is about 20 miles, but to avoid rather bad forest ground we prefer the sea route, which is about 6 or 8 mins longer. Glancing at the watch strapped in front of me, I noticed it was 6.15 p.m., and setting my motor (Gnome) to run 1,200 revs, per minute, I rose steadily from the aerodrome. Drexel had left just 8 minutes before, accompanied by Harry Delacombe. Before leaving the ground I could easily see them in the distance making for the same place as I intended. I at once went up to 500 feet. Unlike our big machine I had no occasion to circle the aerodrome, as I reached this altitude before passing Hengistbury Head, although the machine did not rise as quick as usual owing to a following wind of about 15 miles an hour. Banks of mist at once loomed ominously ahead, and looking towards the land I noticed the mist was much worse than over the sea. I determined therefore to head direct for Hurst Lighthouse. Flying over the sea the whole way, and rising up to 1,000 ft. on my way, I passed through several banks of mist. I thought it rather strange that these banks of mist should linger idly about, especially considering that it had been blowing fairly hard all day, but the air has a lot of secrets yet to be discovered.

"By way of this, my flight a few days before on the Saturday came back to my recollection, when, flying over part of the town and bay, I found when I turned my machine around in the direction of the aerodrome I appeared to be practically stationary, so strong was the wind against me. Below, more than 1,000 ft., I could see Bournemouth Pier. I gazed at it in almost the same manner as one would from a stationary tower. Easing my motor to come to a lower level, I was almost spun round. Instantly I increased my power sufficient to keep my head to wind until I fell to about 500 ft., when I discovered I was again going ahead, there being less wind at this height, and when I reached the aerodrome fifteen minutes later the flags hung absolutely still! Therefore meditate ye scientists who wish to help to the complete conquest of the air, upon the problem of aviators having to meet violent winds 1,000 ft. up on what below is considered to be a calm day. The secret of success would appear to be plenty of reserve power, considering that on this day in question the 50-h.p. Gnome could not make any appreciable headway with a tiny object like the Type XI Bleriot at an altitude of 1,000 ft.

"To resume my homeward journey, when opposite the Isle of Wight I endeavoured to catch a glimpse of friend 'Jones' or his biplane, but failed. Passing over Hurst Castle I saw it was 6.25. By that it is evident I was travelling more than a mile a minute, the wind being directly behind. At the moment though I did not think much about pace, except that I appeared to be travelling rather slowly than the reverse. Looking below at Hurst I thought how easy it would be to take a 'snap' of the place, and for a foreigner to disclose some of our naval secrets, should any be visible from above.

"Leaving Hurst behind about three miles, I turned over the mainland direct for our Beaulieu school-ground, on which I calculated I ought to have landed in a few minutes. To the right I saw Southampton, and such a thing as losing my way never occurred to me for a moment, as the whole of the forest and the surrounding country is so entirely familiar to me from having motored over it for the past ten years. Again glancing at my clock I saw it was sixteen minutes to seven. I at once realised that I must have passed my destination. It seemed incredible that I could do this, as the flying grounds are nearly 5,000 acres, I believe, in extent. What height could I be up to have done this? Referring to my recorder I found it registered 1,200 feet, from which height I should have seen it easily. However, facts are facts, so I decided to drop down a little and circle round to pick up a bearing. The third circle brought me into a white cloud or mist which enveloped me for a minute or so, thus completing my mystification. After this nothing appeared familiar that might have helped me out of my quandary, although even then I felt I would find my way. So I dropped low enough to follow a road, which I felt sure would give me a clue. But in this I was disappointed. Road after road I picked out and followed with the same result. Small villages that I must have motored through dozens of times were all alike, unrecognisable. Not until 7.30 did I give up hope of getting to Beaulieu. As a last resource, why not try to find the sea, I thought? I had found it very easy to distinguish water from land at almost any height within sight. So I determined I would mount up, spy out the sea, and return to Bournemouth. After steadily rising to over 2,000 ft. or so, I had, however, to give up this idea, as glancing at my petrol and oil, I found it was nearly all gone. Then and not before did I really realise the distance I must have travelled to have used 10 gals, of petrol and 4 1/2 gals, of oil. I quickly made up my mind to find a landing spot. Descending at once to a low level I found I was over the heart of the forest, whereas before my final effort to discover the sea I had noticed plenty of possible decent landing places, had I wished to regain terra firma. Now, flying straight on, in as direct a line as possible, in a very few minutes I was over fields and a small town. The fields, although very small, at least offered fairly safe landing, and selecting what appeared to be the largest, I was forced to switch off my motor and do a vol plane. Levelling my machine up just before reaching the earth, I let her fall flat, the tail slightly low. Unfortunately my propeller had stopped in an upright position and stuck in the earth, causing the machine to heel up. Alighting from the front instead of the usual back way, I caught hold of the tail and pulled her down straight, when I found the two front cross-pieces, top and bottom, were damaged. The propeller had a split from the boss down to about a foot from the end. Previous to landing I saw a lot of people, who now rushed up. One of the locals demanded 'Who be 'e?' To which I replied, 'I hardly know myself. Where am I?' 'Thee be about a mile from Fordingbridge,' came the prompt reply. And it was then about ten minutes to eight, one hour and thirty-five minutes since I left Bournemouth. I must, therefore, have travelled, circles and straight, something over 70 miles. Dismantling my machine, I proceeded at best speed by motor, hired in the village, to Beaulieu to relieve the anxiety of my wife and friends who were following me by cars. I arrived at 10 p.m., but so difficult a course to follow had I flown that poor Drexel, Grace, Delacombe and Spottiswood hunted the Forest till five o'clock next morning before locating the place of my descent. Hearing at last that I was safe, they at once turned for Beaulieu and rest after nearly nine hours' search. They told me afterwards that I passed right oyer the ground and sheds - in fact, clean over the machine which Drexel and Delacombe came in. I was then about eight or ten hundred feet high. Believing I was making for Southampton they did not worry about me until it began to get dark. My wife, who was present, assured them I knew the Forest too well to lose myself; I must, therefore, have come down somewhere, owing to motor or other troubles. That I had lost my way never entered anybody's mind.

"Now the real cause of my losing my way was due to my motor not being sufficiently guarded to restrain the oil from flying in my face. Almost impossible as it may be to believe, this formed a film right over my eyes without my being aware of the fact! The consequence of this was that I thought I was in a dense mist until I bathed my face in hot water. After which the mist disappeared, as if by magic, thus accounting for my passing over the school ground and sheds without seeing them. Upon reflection my route must have been as follows :- Bournemouth direct to 3 or 4 miles beyond Hurst, up the Solent, across Beaulieu Heath and village, Hythe, Sowley, across the railway at Lyndhurst Road direct for Lyndhurst, circled over part of the Forest in the direction of Cadnam, back over the Lyndhurst Road Station, turned again near Totton direct for Salisbury, finally circling over Fordingbridge, and landing in an oatfield one mile out."

Flight, August 20, 1910

PARIS TO LONDON

Moissant Flies the Channel with a Passenger.

JUST as we go to Press news comes to hand that for the fourth time the English Channel has been crossed, and this time by a monoplane carrying two persons. On Tuesday afternoon at five o'clock M. Moissant left Issy, near Paris, announcing his intention of flying to London. He was accompanied by his mechanic, and without more ado, heading for Amiens, landed there at half-past seven. He decided to stay there for the night, but early the next morning he was astir, and at a quarter-past five was in the air and making for Calais; there he descended at 7.15 a.m. A rest of two hours and a half was then made, and meanwhile the faithful mechanic replenished the tanks, and made all preparations for the cross-Channel trip. At a quarter to eleven all was ready, and the Bleriot two-seater once more took the air. A fairly stiff breeze was blowing, driving the aviator a little off his course, so that, instead of striking the English coast at Dover, as he hoped, he passed over Walmer. Owing to a strong wind then encountered it was decided to land, and a safe descent was made at Willows Wood, near Tilmanstone, about 7 miles from Dover, the time then being 11.25 a.m.

Flight, August 27, 1910

"PARIS TO LONDON" BY AEROPLANE

WE were just able to give details in our last issue regarding Mr. John B. Moisant's flight from Paris to his landing on British soil at Tilmanstone, near Walmer. It is a little curious that during the first three stages, up to his landing, everything went off without a hitch, but as soon as the aviator landed in Great Britain, his troubles began in the shape of wind and rain. All day on Wednesday he remained at Tilmanstone waiting for the weather to moderate, and eventually he decided to postpone his departure till the following morning. The sun was shining brilliantly on Thursday morning, when shortly before 5 o'clock the machine was wheeled out, and in a few minutes, with its pilot and his trustful mechanic Fileux on board, it was in the air, and heading for London. Canterbury was soon passed, and good progress made until Sittingbourne was sighted, when a broken valve-rod necessitated a stop after a flight of 1 hour 5 mins. A local mechanic effected a repair, and at half past nine the machine once more rose to continue its journey to the Metropolis. Only a short distance had been covered, however, when the engine stopped again, and Mr. Moisant was forced to make a sudden descent at Upchurch, near Rainham, 7 mins. after leaving Sittingbourne. About the best spot he could reach, under the circumstances, was an allotment garden, and in landing there the machine sank into the soft soil, with the result that the propeller was done for and the chassis damaged. Mr. Moisant sought the assistance of Messrs. Short Bros., whilst Capt. Hordern, R.E., of Chatham, rendered valuable aid, repairs being effected very quickly, and soon all was in readiness with the exception of the propeller. A new one was wired for, but this did not arrive from Paris until Friday morning. It was soon fitted, but then the strong wind rendered it advisable to postpone the start. On Saturday morning Moisant made another trial, but could only advance by between two and three miles, when the wind over the hills proved too much for him, and he landed at Gillingham. There he was forced to remain during Sunday. He was early astir on Monday, and was in the air at 4.29, with the intention of going to the Crystal Palace. He, however, found the tussle with the wind a very fierce one, and at the end of 58 mins. he had been driven considerably off his course. As his petrol supply was then getting rather low he determined to descend, and landed at Wrotham, a distance of about 19 miles from Rainham. The petrol tank was replenished, and another start made after a stop of half an hour. No less than 27 minutes were expended in covering four miles, the aviator finding it impossible to get his machine to rise sufficiently to clear the Otford Hills. He therefore deemed it prudent once more to descend, this time at Kemsing, a little place not far from Sevenoaks. A sudden landing damaged the machine, but Moisant, in his characteristic optimistic manner, set to work at once to put matters right, and announced his determination of completing the journey to London, and that only by aeroplane.

The determination of the man is exemplified by the undertaking of this journey, although it is the first time Mr. Moisant has been in England, and in fact he declares that until he flew to Amiens he was entirely ignorant of the country north of Paris. He is an American architect of Spanish descent, who came to Europe some months ago to study aviation. He went to Issy, and there experimented with a couple of machines of his own construction, and eventually decided that it would expedite his own experiments if he learnt to fly a well-known machine first. He therefore obtained a Bleriot, and soon proved remarkably proficient, obtaining his certificate quite easily. His first noteworthy flight was that from Etampes to Issy on the first day of the Circuit de l'Est. During this trip, as throughout his flight from Paris to England, Mr. Moisant has always been accompanied by his mechanic, and during the last stages from Rainham he has carried an extra passenger in the shape of a little kitten. Mr. Moisant has steered throughout his trip by the aid of a compass floating in glycerine, and he asserts that he has found it perfectly satisfactory.

In referring to the two machines which he has himself designed and had constructed, Mr. Moisant gives some interesting details regarding them. The first had a bird-shaped body, and on its first trial at Issy last year shot up about 90 ft. in the air, but came down again as suddenly. This machine was followed by one which was a cross between a biplane and a monoplane, and its chief peculiarity was that there was not a wire in it. The planes were constructed on the suspension bridge principle, and Mr. Moisant declares they were so strong that a weight of 500 lbs. could be hung at one end without them bending. As soon as Mr. Moisant feels proficient with his Bleriot he proposes to recommence experimenting with this machine, which he says can attain a speed of 120 kiloms. an hour.

Flight, October 8, 1910

FOREIGHN AVIATION NEWS.

Morane Tries for the Michelin Grand Prix.

FRESH from his triumphs in Spain, Morane, after spending a few days at Etampes testing a new two-seated Bleriot fitted with a 100-h.p. Gnome engine, flew over to Issy to try for the Michelin Grand Prix of L4,000. This calls, as our readers will remember, for a flight from Paris to Clermont-Ferrand over the Puy-de-Dome, the machine carrying two passengers throughout. He made his attempt on Wednesday, and it ended in disaster. He left Issy all right, but at Boissy St. Legere the machine fell. Morane had both his legs broken, and his brother, who was accompanying him, sustained a fractured skull.

Flight, October 15, 1910

FOREIGHN AVIATION NEWS.

The Mishap to the Morane Bros.

IN our last issue we were just able to mention the abortive attempt by Leon Morane, accompanied by his brother, to fly from Issy to the Puy-de-Dome. Although both the brothers were seriously injured, they were not so bad as at first reported, and the latest advices from the hospital state that they are now out of danger and progressing satisfactorily. Leon Morane had his right leg broken in two places, while his brother sustained a fracture of the left leg and dislocation of the hip. Up to the present the cause of the accident has not been definitely discovered, but Leon Morane gives it as his opinion that one of the steering wires broke, while Mons. Bleriot himself, after examining the machine, stated that he thought the accident had been caused by a spare tin of petrol shifting its position and jamming one of the wires.

Flight, October 22, 1910

IMPRESSIONS OF THE PARIS SHOW.

By OISEAU.

<...>

The military value of aeroplanes as illustrated during the recent manoeuvres has induced many makers to design specially for the Army. Clerget, for instance, has produced a tandem monoplane with three seats and driven by a 200-h.p. motor. Voisin is the first to fit a mitrailleuse to his two-seater biplane. The effects produced after firing this gun from some height ought to be interesting. The Breguet biplane and the Hanriot and Bleriot monoplanes are also mounted as aeroplanes of war.

<...>

M. Bleriot exhibits machines similar to those which have done so much to increase his reputation during the past few months. He, too, has a military type of monoplane - a two-seater made rather heavier and stronger than usual. Except in so far as the fuselage has been altered to take the Gnome engine, the Bleriot remains the same in appearance now as it was a year ago. The angle of inclination and the wing curvature is much less, and to the passenger machine is fitted a fan-shaped tail. Beyond that no change.

<...>

Flight, December 31, 1910

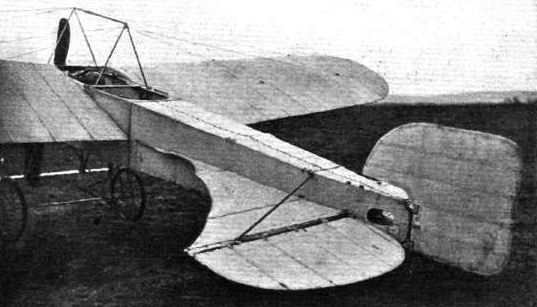

THE BLERIOT TWO-SEATER MONOPLANE, TYPE XI, 2 BIS.

THERE are some names in aviation as in other spheres of life that carry with them, apart from the fame of recent successes, a certain glamour inseparable from intimate association with the making of history. Bleriot is a name like that, for ever since one sunlit morning of July, 1908, when he made the first flight across the English Channel on a heavier-than-air machine his name has entered into the records of all time. His flight was the first to strike the public imagination. Others previously had made longer flights and perhaps more meritorious flights, and he himself had put up performances to his credit of a much more daring kind, but that one romantic crossing of a twenty mile strip of the sea outbalanced all other attainments in the eyes of the world. From that date he and the pilots trained by him, who fly the materialised products of his brain, have stepped from one success to another until now he stands amongst the half dozen who are now supreme in the realm of flight.

Four or five years have elapsed since M. Bleriot first interested himself in a practical manner in the problem of human flight. Nor was his progress to ultimate success at first attended with unvaried good fortune. Accidents happened to his -machine with unerring regularity up to within a month or two of his great flight. Often he changed his designs, but always did he remain a firm supporter of the monoplane principle, and now that he has evolved a successful passenger-carrying machine it is still of this type.

It was at the historic Rheims meeting of 1909 that M. Bleriot flew his first two-seater, but in this machine the seats were placed directly below the main planes, and behind the engine - an 8-cyl. E.N.V. The propeller was chain-driven, and geared down. This type was but a qualified success. It will be remembered that the first machine purchased by Mr. Grahame-White was one of this model, and was named by him the "White Eagle."

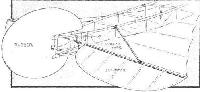

In time for the Rheims meeting of this year, M. Bleriot produced his latest two-seater, which was first seen in England at the Bournemouth meeting. In this model the passenger and pilot sit side by side on a seat similarly arranged to that on the single-seater; in fact, the only essential differences from the smaller model are the wider body and the pigeon-shaped tail.

The Oregon pine body is of the same box-girder construction used on all Bleriot machines. Four slender wooden booms run the entire length of the machine, being strutted apart at intervals of 18 ins. or so, and tied by diagonal wire bracing anchored to small wire V-pieces, which also help to secure the strut-sockets. This method of construction and the use of these V-anchor-pieces is patented by M. Bleriot. At the tail, the wooden booms come together to join a sternpost to which the single rudder is hinged. In front they open out, to admit of the seats and the engine-bearers.

The landing chassis differs but little in fundamental principles from that of the cross-Channel Bleriot, except that it is, of course, much stronger. Two stout ash struts run from the engine to the lower cross bar of the carriage, while a similar pair are carried from a point further back on the body, thus ensuring great rigidity between the carriage and the frame that it supports. As is usual on Bleriot machines there are no skids, but the two wheels are pivoted on castors so that they may turn in any direction. One great advantage of this system is that a sideways landing, so frequently made even by expert pilots, can happen with very little risk of damage, the wheels turning in the direction required, and running quite freely. On the other hand the absence of skids makes it less easy to withstand the shock of a clumsy descent, and even after a good landing the very freedom of the running of the wheels makes it difficult to stop in a reasonable distance.

The wings are double-surfaced with Continental aeroplane fabric spread over slender ribs of pine, which are themselves secured by brass screws to the two main spars of ash running the entire length of the wings. The front spar is situated about a foot from the entering edge of the wing and is secured to the body by a socket formed by a steel tube placed across the frame in front of the pilot. The rear main spar is attached by means of screws to the side members of the body. The planes are of slight curvature, and are suspended from a kind of trestle set above the body by several wire cables running to different parts of the wings, which cables on Messrs. Gibbs' machine are duplicated in every case. Below, the wings are attached to the carriage by steel tapes an inch broad. The wires effecting the flexing of the wings for the recovery of lateral stability are duplicated.

The tail of the two-seater is different to that of any other Bleriot in that it is of the non-lifting type, and has the elevator (which is made in two sections to allow space for the rudder) hinged to its trailing edge. The shape can best be realised by reference to the general plan of the machine annexed to this article. The framework of the tail is of steel tubes, over which the fabric is stretched. The broadest part is at the rearmost edge, where it is 12 ft. span. Along this edge runs a steel tube, to which the elevator is hinged. This tube is stayed at the upper edge of the body by two steel tubes. Under the tail plane is a single landing wheel, sprung in the same manner as those on the carriage.

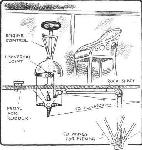

The two seats are placed side by side, that on the right being for the pilot, before whom is the control cloche. This consists of a column surmounted by a fixed wheel, serving the purpose of a handle.

At the base of the column is a large bell-shaped member in aluminium surrounding the pivot on which the column is universally mounted. To this bell the control wires are attached. At the front and back are wires leading to the elevator; on the right is a bar leading to an arm below the body, which controls the warping of the wings. The two elevator wires are attached below the bell to a cross-shaped steel piece, from which run two wires direct to the elevators. Similarly from the flexing arm run wires to the rear spar of either wing. Reference to the accompanying sketch will explain such details as must ever remain complicated in any written description. The movements of the column for the purpose of control are all natural in action. To elevate the aeroplane the column must be pulled backwards, and a movement in the contrary direction brings the machine down again. Falling to the right is corrected by moving the column to the left, and vice versa. Directly below the hand wheel are placed the control levers of the Gnome motor.

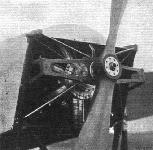

The 50-h.p. 7-cyl. air-cooled Gnome motor is mounted in a special pressed-steel frame fastened to the front of the fuselage. This frame is covered above and at the sides by a sheet aluminium casing. Behind the frame, inside and across the body, are placed the petrol and oil tanks.

The make of propeller naturally varies according to the ideas of the purchaser, but as a rule the Chauviere Integrale is fitted.

The price of the Bleriot two-seater complete with Gnome motor is 28,000 frs.

In concluding we would acknowledge the courtesy of Messrs. L. D. Gibbs, Ltd., for the permission to photograph their Bleriot two-seater for the purpose of illustrating this article. The machine in question is at Brooklands, where, piloted by Mr. Gilmour, it has made some of the finest flights yet performed above British soil.

Flight, March 25, 1911

OLYMPIA-1911

Aeroplanes.

L. Bleriot (STAND 43). - Bleriot type XXI. Monoplanes, single-seaters, fitted with 50 h.p. Gnome engines. Also a Type XXI-"two-seater" military type monoplane, fitted with 70-h.p. Gnome engine.

Single-seater. - Dimensions: length, 23 ft. Span, 29 ft, Weight, 550 lbs.

Remarks. - This type follows closely in general design the well-known Cross-Channel type, but several improvements have been effected, viz. :-

The motor and the tanks are now covered by a metallic bonnet, which has proved a great improvement, to facilitate the power of penetration of the machine through the air at high speed, and it protects very greatly the aviator against the rush of wind caused by the propeller and the speed; this bonnet is fitted with sliding openings to obtain access to the tanks.

The top pylon holding the cables that support the wings has been altered; it is now a single one, which offers less resistance to the air, and the construction of which gives the maximum of strength to that important part.

The back wheel has been replaced by a new skid made of very elastic wood, which greatly absorbs shock in landing and brings the machine more quickly to a standstill.

The elevator or horizontal rudder consists of two ailerons fixed behind the tail, after the principle which has been so successfully used during last year on the double seater.

All the transmission cables, acting on the rudder and elevator, are doubled; all materials are submitted to the most rigorous tests with special machines, and the wings, tested with sand, on the machine turned upside down, can support without deformation or extra strain a pressure of 610 kilogs. on each wing, or a total of 1,220 kilogs. (a security coefficient of 4 according to the rules adopted bv the Ae.C.F.).

This trial was made officially on March 3rd, before the delegates of the French War Ministry and other officials.

Two-seater. - Dimensions: Length, 26 ft. Span, 36 ft. Weight, 700 lbs.

Remarks. - Similar in general design to the single-seater, but has been speciallv designed for military work. The two seats are placed side by side and protected by a bonnet covering the motor, and with the control-levers so arranged that either of the aviators can take command in turn.

The instruments necessary to the proper use of an aeroplane in cross-country flights, such as compass, map-holder, altimeter, block-note holder, &c, are fixed on a sliding rest, which can be shifted in front of one or the other instantly.

The back part of the body is entirely covered and the sides taper down to the end of the tail to reduce the effect of the side wind on the tail and balance it with the front planes when they receive a strong gust of wind.

The general shape of the machine is very graceful and the elevator is placed behind the tail, the rudder coming slightly in front of it over the fuselage.

A special very short landing skid is fitted so as to bring the tail very low down when at rest, so that the wings offer a great resistance in landing and bring the machine at rest in a very short space.

The French and Russian Governments have already ordered a great number of this type of Bleriot monoplane.

Flight, June 3, 1911.

FROM THE BRITISH FLYING GROUNDS.

Liverpool Aviation School, Sandheys Avenue, Waterloo.

ON the 23rd, 24th and 25th ult. no flying was attempted owing to excess of wind. On the 26th Mr. A. Dukinfield-Tones made several straight line flights of half a mile each, and on the 27th in the evening he repeated the performance in a 12-mile wind, showing considerable aptitude in balancing and steering against a nasty cross drift.

On the 28th Mr. Melly had out the two-seater and flew to Southport with Mr. Jones as passenger, total distance 34 miles. On the outward journey he followed the coast line, but on the return journey he took a direct course across country.

On the 30th Mr. Jones made a few short flights before breakfast, but owing to the missing of the engine brought the machine in for examination. Meanwhile Mr. Melly took out the two-seater with Mr Swaby as passenger, and starting in a northerly direction made a complete circle of Liverpool, via Crosby, Amtree, Wavertree, Aigburth, then crossing the Mersey to Port Sunlight. He then followed the left bank of the Mersey passing over Birkenhead Park and west of Liscard, circled the New Brighton Tower, re-crossed the Mersey and landed opposite the school hangars. The total distance was 35 miles, which was accomplished in the extraordinarily short time of 41 minutes. The average height maintained was 1,000 feet.

Flight, June 17, 1911.

BRITISH NOTES OF THE WEEK.

Flying at Liverpool Gymkhana.

A NOVELTY was introduced in the programme of the gymkhana held at Childwall on Saturday by the Liverpool A.C. in conjunction with the Liverpool Polo Club in the shape of a couple of exhibition flights by Mr. Melly. Accompanied by Mr. Dukinfield Jones Mr. Melly flew over from his flying grounds at Waterloo early in the morning. Unfortunately the wind freshened after his arrival, and it was not until about six o'clock in the afternoon that Mr. Melly got into the air again. He then carried Mr. Lyle Rathbonc, of the Liverpool A.C., for a flight of 6 minutes, during which a figure of eight was made. About half an hour later a second trip was made, this time with Mr. J. Grahame Reece. Subsequently, although the weather was not very good, Mr. Melly succeeded in flying back to his hangar at Waterloo, being accompanied again by Mr. Dukinfield Jones.

Flight, August 26, 1911.

FOREIGN AVIATION NEWS.

An American Lady Aviator.

THE number of certificated aviators among the gentler sex is being gradually added to. The first to obtain her certificate under the new rules was Madame Driancourt, at the French Caudron School, but soon after her was Miss Harriet Quimby, of California, who qualified on a Moisant monoplane at Mineola, N.Y., on August 1st. Miss Matilda Moisant, sister of the late J. B. Moisant, has also qualified for a pilot's licence on a Moisant monoplane, and Miss Blanche Scott should qualify shortly.

Flight, October 14, 1911.

NASSAU BOULEVARD MEETING.

<...>

In the event for greatest altitude for women aviators. Miss Mathilde Moisant was the only one entered, and she made a bid under these circumstances for the Rodman-Wanamaker trophy by climbing in her 50-h.p. Gnome-Moisant-Bleriot to a height of about 1,200 ft., descending with a spiral vol plane.

<...>

Flight, April 27, 1912.

FLYING THE IRISH CHANNEL.

Now that well over a week has passed since Mr. D. Leslie Allen set out from Holyhead at about seven o'clock in the morning of Thursday of last week, to cross the Irish Channel, and no news of his whereabouts have come to hand, it certainly seems that it is our sad lot to mourn another British life, sacrificed - we think again quite unnecessarily - in the practising of the sport. It was on the previous day, the Wednesday, that he with Mr. Corbett Wilson, set out from Hendon to fly in company to Dublin. There was no wager between them as to who should get there first, as has been generally seated. They simply had a feeling that they would like to visit their native island by the new method of locomotion, and they both started off in friendly rivalry to fly there together. At that time it was thought by those at the aerodrome that the flight was an unusually risky one for such comparatively inexperienced pilots to attempt. Further, so hastily had the trip been arranged that no precautions were made against the possibility of having to descend in the sea. They both left Hendon soon after half-past three p.m. on Wednesday, and Allen, following the London and Northwestern Railway line, arrived at Chester about half-past six in the evening, after landing some ten miles the other side of Crewe to ascertain his whereabouts, Corbett Wilson landed the same evening at Almeley, about fifteen miles northwards of Hereford.

Just after six on the following morning Allen started from Chester and passing over Holyhead an hour afterwards, flew out to sea. He has not been seen or heard of since. His friend, Corbett Wilson, left Almeley at half-past four that afternoon and was forced to land some few miles further on at Colva in Radnorshire. On Sunday morning early he set off again and this time reached Fishguard, leaving again at six o'clock on the following morning, Monday, and flying across St. George's Channel in the direction of Wexford.

One hour and forty minutes was occupied in crossing the Channel and a landing was made at Crane, two miles from Enniscorthy, the trip being the first occasion that the strip of water separating Ireland from the main land has been entirely crossed by aeroplane. It will be remembered that Mr. Loraine's attempt in 1910 failed by some 300 yards.

Mr. Vivian Hewitt also has the intention of attempting the crossing to Ireland, but his route is to be from Holyhead to Dublin across the Irish Sea. At the time of writing he is waiting at Holyhead for favourable weather. He left Rhyl at 5 a.m. on Sunday morning and after remaining up for an hour and twenty minutes was forced to land at Plas in Anglesey. His flight was made at an average of quite 5,000 ft., for he says he could distinctly see over Snowdon. The wind was boisterous in the extreme and he testifies to the fact that had he remained up much longer he would undoubtedly have been ill, so much was he tossed about. The section from Plas to Holyhead was flown on Monday morning, starting from the former place at about 9.30. Mr. Vivian Hewitt has his machine in Lord Sheffield's grounds and will continue his flight as soon as conditions prove favourable.

Flight, May 4, 1912.

THE IRISH SEA FLIGHT.

MR. VIVIAN HEWITT is to be congratulated upon his excellent flight across the Irish Sea on Friday last, when his exact time from taking off at Holyhead until his landing in Phoenix Park, near the Hibernian Monument, was 1 hr. 15 min. Mr. Hewitt wisely guarded against undue risks by providing himself with a safety belt, &c., in case he should fall short of his destination. Again one further record has been established in regard to crossing the open sea, this following on last week's announcement of St. George's Channel being flown by Mr. Corbett Wilson. This week we give Mr. Vivian Hewitt's portrait as a "Flight Pioneer" and the following is Mr. Hewitt's own version of his trip and the days preceding the actual flight:-

"I started from Rhyl at 5 a.m. last Sunday morning and flew off over the sea in the direction of Holyhead. After rounding the Great Orme at Llandudno I made for a point of land running out to sea. I could see Holyhead Harbour by this time, but the wind started blowing half a gale and I found it impossible to get there. I was up an enormous height, and could distinctly see over Snowdon. The wind blew me right down the coast and I had to put the nose of the machine down and let my engine out, otherwise I should have been blown out to sea. I landed eventually at a place called Plas, in Anglesey, at 6.20. I felt very sick, as I had been tossed about all over the place. The machine was roped down and next day I started for Holyhead at 9.30 and landed in Lord Sheffield's grounds 20 minutes later, it being out of the question to attempt flying the Channel owing to a dense fog. From Monday till Friday morning I was held up at Holyhead owing to wind which was blowing at about 35 miles an hour in the wrong direction. On Friday morning I started off at 10.30. There was a good deal of wind at the time and a lot of haze, and when I passed the Stack I was blown down Channel about 5 miles. I managed to work into it, however, and got my true course from the breakwater. I lost sight of land after ten minutes and about five minutes after I sighted the Mail Packet coming from Kingstown. I passed right over her from stem to stern and lost her smoke about three minutes after in the haze. Although all the boats had been informed, and the Mail Packet was looking out for me, they never saw a thing, showing what a great height I was.

"After leaving the Packet I saw nothing more for fifty minutes, and steered by the sun whenever I could. I ran into dense banks of fog, and at times I could not see the wing tips. After about fifty minutes I saw the Wicklow Mountains, and passed over Kingstown Harbour very high up. I passed over Dublin about 2,000 ft. up, and when planing down experienced the worst air-currents that I have ever come across. I was all but upset twice, and the machine dropped 500 ft. I managed to land safely in the 15 acres in Phoenix Park and was treated very kindly by everyone. The machine I used was my 50 Gnome-Bleriot."

Показать полностью