Журнал Flight

Flight, December 30, 1911.

PARIS AERO SHOW.

Caudron Biplane.

MUCH interest attaches to the little Caudron biplane by reason of its diminutive size and the simplicity of its construction. The machine in question is fitted with one of the new "V" type Anzani engines and is capable of a speed somewhere in the neighbourhood of 55 miles per hour. A certain degree of automatic stability in a lateral sense is obtained by the method of construction of the planes. The rear-boom of the plane is situated only two feet behind the entering edge, and the remainder of the plane that extends for a distance of 2 ft. 6 ins. behind the rear boom is formed by the application of a single surfaced covering over flexible continuations of the ribs. Landing carriage and tail outriggers are combined in this little machine, and in this way much multiplicity of parts is done away with. A little body is provided for the accommodation of the pilot midway between the main plane, and at its forward extremity is mounted its power plant. A single monoplane surface performs duty as both stabiliser and elevator, elevation being effected by flexing the rear half of this surface which is constructed after the same manner as the main planes. Two vertical rudders, working in parallel, provide means whereby steering is done. This handy little machine is listed at L320 and at this price should find many customers.

Principal dimensions, &c.:-

Length 22 ft. Weight 500 lbs.

Span 24 ft. Speed 55 m.p.h.

Area 220 sq. ft. Motor 35-h.p. Anzani.

Price L320

Flight, November 30, 1912.

THE CAUDRON BIPLANE.

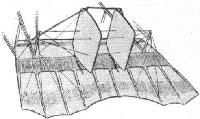

IT is difficult sometimes to follow with quite the closeness that one could wish the line of thought that the designer has pursued in the evolution of the latest product of his brain. But with a machine like the Caudron there is at least the inspiration of an unusual appearance to stir the mind's curiosity to the point of inquiry. You look, for example, at one of those little biplanes that has been doing such good service in the Ewen School at Hendon, and you observe that peculiar little coracle-like body that is so curtailed by comparison with the corresponding member of the ordinary tractor-driven machine. It is at once a point of interest, and one is impelled to ask, why is it built as it is? Its mere presence is a clear indication that the designer appreciates the advantage of protecting the pilot and also of stream-lining his body as a means of reducing head resistance. The reason for curtailing the extension that ordinarily forms the backbone to such machines, however, may be due either to one of two causes, either the designer has a prejudice against the exposure of a backbone, and particularly a surfaced backbone, to the wind, or the reason may be found in the desire to demonstrate some particular principle in connection with the tail of the machine, which does not lend itself so well to the backbone type.

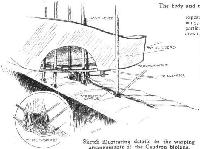

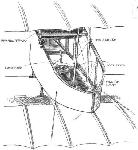

In the Caudron biplane, this latter assumption is more reasonable because the tail is quite one of the most interesting features of its construction at the same time that it is also one of the most simple. The tail of the machine is large; it spans 10 ft. and has a chord of 5 ft. 3 ins. More important than this is the fact that it is designed to warp in unison with the main planes for the purpose of lateral control, and the warping arrangements are facilitated by the outrigger type of support, by means of which the tail-member in the Caudron biplane is attached to the forward part of that machine.

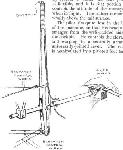

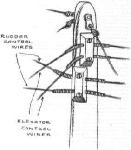

Glancing for a moment at the composite page of sketches that accompany this article, the drawing (5) in the centre thereof illustrates the simple vertical lever that is arranged in front of the pilot, and by means of which he controls the machine in flight. Moving the lever to the left or to the right from its neutral vertical position rocks a shaft that carries the main wing warping-wires attached to it by means of quadrants illustrated in an adjacent sketch (4). At the same time that the handle of the lever moves over, say to the right, the lower extremity of the lever, which projects below the shaft, moves over to the left, and the wires that are attached thereto pass rearwards to the tops of a pair of upright masts that stand at each end of the transverse boom running through the middle of the tail plane. The wires are guided through flexible tubes attached to the mast-heads in the simple manner illustrated in another sketch (3), and terminate by attachment to the flexible trailing-edge of the tail.

When the lever is moved over as mentioned, the lateral displacement of its lower extremity tends to slacken the wires leading to one of the tail-masts and to pull the others taut. In this way one corner of the tail plane warps upwards while the other is deflected downwards; and the action is positive in both respects, because, as another glance at Fig. 5 will show, there is another set of wires running from a higher point on the lever to the underside of the tail plane for this purpose.

These same wires, which are used in the above described manner for warping the tail for lateral balance - in which action the movement of the tail harmonises with the movement of the main wings - also serve to flex the trailing edge of the tail plane upwards and downwards as a whole when it is to be used as an elevator. This action is accomplished by moving the control lever to and fro in the usual way.

Speaking of the flexing of the tail plane naturally attracts attention to the peculiar construction of the plane itself, which is similar, except for an absence of permanent camber in the ribs, to the construction of the main wings. The peculiarity lies in the extent of the trailing edge, which is a little more than one half of the chord in length. As a consequence of this, the main spars are unusually close together, but that portion of the planes which lies between the main spars is of the orthodox rigid construction and is double surfaced. The long trailing edge has its flexible ash ribs enclosed in pockets that are sewn on to a single thickness of fabric.

This combination is extremely interesting, and indeed the machine in every respect deserves study, as the illustrations of it that we reproduce herewith very clearly show.

It is significant of what a remarkably efficient machine the 35-h.p. Anzani-Caudron biplane is, for it has been found that it can fly quite well, even if the motor is only firing on two of its three cylinders. With the motor developing its full power, it can lift a passenger, as Rene Caudron demonstrated when his first biplane came to Hendon. M. Caudron himself can be of no mean weight, and the fact that his passenger sat outside on the cellule did not render the test any too easy to accomplish.

The two-seater Caudron biplane is almost identical with the 35-h.p. single-seater, both as regards its dimensions and its details. It has, however, the difference that its nacelle is designed for two, and that a more powerful motor - a 60-h. p. Anzani - is fitted.

Flight, February 8, 1913.

WHAT THERE WILL BE TO SEE AT OLYMPIA.

THE MACHINES.

The W. H. Ewen Aviation Co., Ltd.

This well-known firm, with centres at Hendon, Lanark, and Glasgow. Will be showing two machines on their stand No. 47, a monoplane and a biplane. Originally they had made arrangements to exhibit a 50-h.p. Gnome-engined single-seater monoplane, and a 35-h.p. Y-type Anzani biplane, both brand-new and of Caudron design and manufacture. However, such has been the demand, that they have sold both these machines, the monoplane to a well-known English customer, and the biplane to Mr. A. W. Jones, who has despatched it to Australia, where Mr. Jones holds the agency for Caudron machines. Thus the Ewen firm have had to fall back on machines that they had already in stock, and for that the exhibit will be none the less interesting. In place of the 50-h.p. Gnome-Caudron monoplane, they will show the 45 h.p. Anzani-engined single-seater, of which Mr. Ewen took delivery at Crotoy and flew back to England in the early part of last year. On this same machine too, M. Guillaux flew in connection with the Aerial Derby last year. Although comparatively low-powered, such was the machine's speed that that excellent pilot would have probably won the race had he not, when quite near the finishing point, lost his way, and then run out of petrol. The monoplane is especially interesting for the fact that it is one of the smallest and speediest successful monoplanes built.

For the biplane, Mr. Ewen is making an attempt to get delivery from the French Caudron works of a new 35-h.p. biplane. If he cannot get delivery in time, his firm will exhibit their brevet biplane, on which, at Hendon, something like 15 tickets have been taken inside seven months. Naturally it will not be a show-finished machine; it will be shown, taken direct from strenuous school work, in its natural oil and mud-bespattered condition.

In addition, the Ewen Co. will have on their stand samples of Kelvin compasses, which have a reputation for being the most deadbeat instruments of their kind ever constructed. They will also be showing a range of Gremont propellers and a type of petrol motor of quite revolutionary design.

Flight, February 15, 1913.

<...>

The 35-h.p. Caudron Biplane is a machine that is becoming increasingly popular. The small model similar to the one shown at Olympia, is chiefly used for instruction work, although many similar ones are privately owned. They are quite inexpensive to buy, and are not by any means difficult to handle, as machines go. The French army own several of this type and use them for instruction purposes As well, of course, they have many of higher engine power, which are used for more serious work. There is at present under test at Farnborough one of these machines fitted with a 70-h.p. Gnome motor which we are inclined to believe has given very good results. In a wind they behave extremely well, for the rear portions of the planes are very flexible, thus allowing the machine to ride through a gusty wind with a certain smoothness, in the same manner as a well-sprung car may travel over rough road surface without the jars being particularly noticeable to those seated inside.

The planes span 30 ft. and 23 ft. 3 ins. respectively, and have a chord measurement of 4 ft. 6 ins. They are separated by 12 stanchions and braced strongly with piano wire. As in the monoplane, the main spars are placed only about 18 ins. apart. The ribs are cut from French poplar and overhang the rear spar nearly 3 ft., forming the flexible trailing edge that we have referred to above. Warping is employed to correct lateral equilibrium.

The body is a small coracle-shaped structure built up in the same manner as a monoplane fuselage. The front is capped by a steel plate, and to this the motor is bolted. Subsidiary supports, in the form of steel tubes support the front of the crank case. The remainder of the body is covered in by fabric to give it a fair streamline shape, and to help shelter the pilot from the wind. The body of the machine at Olympia is fitted with a superstructure that covers in the fuel tanks and acts as a very convenient wind shield. Seated comfortably inside, the pilot has between his knees a vertical jointed lever by which he controls the warping and elevation of the machine. The twin rudders are worked from a foot bar.

The tail is a flexible monoplane surface supported by ash outriggers. A peculiarity of this outrigger construction is, that the lower outrigger members continue forward underneath the machine to form the landing skids. While simplifying the construction considerably, this system has the advantage that these lower outriggers can be made to drag heavily along the ground at the completion of a flight, thus bringing the machine quickly to rest. Again, they are very useful for holding the machine back while the engine is tested, perhaps a minor point, but nevertheless one that is greatly appreciated by the mechanics that attend the machine. They merely have to stand on these outriggers and the outriggers themselves do the rest.

The landing gear is formed by strapping Farman-type wheel units over these outrigger members we have referred to above. Being quite low the chassis is very strong compared with its weight. It is a very ordinary affair - but what matters, it completed the greatly feared rolling test at Farnborough at the first time of asking, without any damage, and there are very few machines that can boast of having done that.

Flight, March 22, 1913.

TEACHING FLYING.

By LEWIS W. F. TURNER.

[These remarks, expressed in simple, everyday language by Mr. Lewis Turner, who through 1912 was one of our busiest flying instructors, will be found of great interest. Mr. Turner was attracted towards aviation in the early days, and first tasted the sensation of flying by going up as a passenger with Mr. Grahame-White, when the latter pilot was flying at the Bournemouth Aviation Meeting in 1910. Following up his enthusiasm, he decided to learn to fly, and, selling his motor business in Dorsetshire, he joined the Grahame-White School at Hendon. That was toward the end of February, 1911. He obtained his flying credencials on April 1st, having the distinction of being the first pilot in England to obtain his brevet after the new right-hand turn test regulations came into force. Thus qualified, he joined the sincedefunct Aeronautical Syndicate Flying School as Pilot Instructor, and flew Valkyrie monoplanes. Leaving that School in August, he went to Russia as Chief Pilot and Engineer to the Kennedy Aviation Company of St. Petersburg. Returning to England in January of last year, he was engaged by the Crahame-White Aviation Company as Chief Pilot and Instructor to the School. Throughout the season until November, when he left that firm, he flew practically every day in all sorts of weather, and had charge of the School instruction work, proving a most painstaking tutor, Mr. Turner it now engaged as Chief Pilot to the W.N. Ewen Aviation Co.'s Schools at Hendon and Lanark.-Ed.]

NOWADAYS it is safe in remark that any pupil who can keep a fairly clear head and who has quite an average amount of common sense can soon learn to fly. He does not need to be an expert at engineering, or particularly well versed in the aero dynamical considerations underlying the flight of an aeroplane. If he is an expert in both these subjects, so much the better, for with an engineer's knowledge he should have an engineer's instinct, and instinct plays a great part in the making of the future airman. A man, to be a good flyer, must necessarily have complete sympathy with his machine. He must not use it harshly, making violent movement with his controlling levers. He must use them gently, and almost you might say, persuasively. There is a great similarity between sailing a boat and flying an aeroplane. On a boat, in changing from one tack to another, you swing the rudder round gently but forcibly. If you were to throw it over suddenly, your boat would not answer her helm anywhere near as well. The same applies to an aeroplane, and personally I find that the best results are obtained by gentle and careful manipulations of the lever. Flying, in a gusty wind, sometimes you have to make harsh movements, but that scarcely concerns the pupil, as his work is confined mainly to flying in relatively calm air.

There is a distinction between putting through a pupil for his certificate and turning out a really efficient pilot who is capable of doing good, plain, straightforward flying without taking unnecessary risks. Some people have an idea that all you have to do to learn to fly is to sit to an aeroplane, have the engine started up, get off the ground, steer the machine about and keep on flying indefinitely as long as the engine remains running. If this were so, flying would indeed be easy. As a matter of fact, it is not difficult by any means, but apart from the actual handling of a machine in the air, there are such things to be learnt as the correct adjustment of controls and wires, the means whereby a sweetly running engine may be always obtained, and so on. There are such things as plugs, magnetos and carburettors, which must be under constant supervision to see that they are doing their work properly. There may be a faulty wire. An oil pipe may become choked. For all such things as these the pupil must be taught to keep a constant look out. As regards actual flying, the pupil who goes steadily, absolutely mastering the points of his first lesson before trying other things which are beyond him, is generally the one who will make the most rapid and thorough progress. Above all, he must pay particular attention to the advice of his instructor. A pupil who is over ambitious rarely gets through his tuition without a smash of some kind, which, although he may escape uninjured, often makes him nervous for some time after, thus, of course, checking his progress. If he does not actually have a smash he will probably come very near to it, and this, most often, has the same effect.

Another thing a pupil will do well to remember is to rely upon himself and his own capabilities, and never trust to luck. He should pay no attention to any superstitious nonsense which is often heard on an aerodrome. One popular superstition is, that when one smash occurs, two others are bound to follow during the day. There is such a thing as your subconscious mind having a reflex on your actions. If a pupil goes out to fly with the idea in his head that, according to superstition there ought to be two other smashes that day, he will probably suffer one of them.

Mascots are much in vogue with some aviators, and although they undoubtedly have some sentimental value, it is of course absurd to believe that they are of any material use in preventing accidents. Personally I have quite a large collection, in fact, if I were to wear them all, I should probably be taken for a Ludgate Hill toy hawker. But whether I wear any or not, my luck, or whatever you like to call it, is invariably the same.

A pupil's first knowledge of aviation is always to be gained in the hangar, where he can learn the working of the controls and become familiar with the different parts of his machine and their adjustments. Then he is taken up as a passenger by one of the school pilots, and this gets him used to being in the air, and to having an extremely noisy engine just in front or behind him. Incidentally, by keeping an eye on the pilot he will see just what movements are required to correct any variation in the attitude of the machine in the air. After a series of passenger flights he is allowed his first practical lesson, commonly termed "rolling." He is put on to a low-powered machine and is permitted to drive it across the aerodrome without leaving the ground. At first he may find a difficulty in keeping the machine on a straight course, but very soon he will pick up the "feeling" of his rudder and be able to run along the ground in a straight line without difficulty from one end of the aerodrome to the other. Having got to that stage, and still keeping up the passenger flight treatment, he is allowed to go out on a higher-powered machine. At first he keeps his engine throttled down and continues to roll until he gets used to being on a different machine. Then he is told to speed up his engine and is permitted to make short hops, using his elevator control gently to lift the machine from the ground and then immediately to return to it. In his early flying practice there is a most important point for the pupil to learn, and that is, never to switch off the motor should he find himself in a difficulty. On a motor car, if there is some difficulty ahead, it is usually right to throttle down the engine and throw out the clutch. But with an aeroplane it is the reverse, for the greater the difficulty you get into, the greater is the engine power necessary to get you out of it. Gradually the lengths of his hops increase, until he is capable of making straight flights the full length of the aerodrome, keeping a few feet off the ground. He is kept at this for some little while, increasing the height of his flights as he gains confidence. The pupil should not be hurried over this stage, because, above all, he is getting good practice at vol plane's, and landings, which are very important.

He is now ready for a left-hand turn, and is sent out to make half turns, using his rudder very slightly at first. He progresses, and eventually succeeds in flying a complete circuit. On reaching this stage he can consider himself well on the way to getting his much-coveted "ticket." Having had plenty of practice at turning to the left, he will attempt to turn to the right. This, in the past, was considered the most difficult task for the pupil, but familiarity has brought with it contempt, and now the right-hand turn is considered to be quite as easy as turning to the left. When proficient with the right-hand turn it is quite a simple matter to fly a figure of eight. With all the experience that he has had up to that point he will not feel any anxiety about flying up to a height of fifty metres, which is the altitude that a pupil must obtain before he can be granted his certificate.

By now the pupil has virtually come to the end of his school tuition, and all that remains to be done is to advise the Royal Aero Club of his readiness to be examined. In his tests he will be required to make two distance flights, each consisting of five figures of eight, flown round marking posts situated not more than 500 metres apart. He must also make an altitude flight as I have mentioned before, going up to fifty metres, but this may be included in one of the distance flights. On each occasion he must land within fifty metres of a predetermined point, and must not use his engine again after touching ground.

Providing he has satisfied the K.Ae.C. observers, he may consider himself a fully qualified pilot, and, in consequence, being pleased with himself and with everything in general, he will undoubtedly follow the usual course of running up to town and standing himself a very excellent dinner on the strength of it.

Another system of tuition is that of dual control. This method consists of the pupil taking numerous flights with an instructor on a machine that is fitted with two sets of controls, so that either may take charge of the machine in the air. Thus the instructor can correct any mistakes that the pupil may make. By this method of instruction a pupil can probably be put through his course of training in a little shorter time, but, in my opinion, it is apt to make him rely too much upon the capabilities of his instructor, thus robbing him of that self-confidence which is so necessary.

Concluding, let me say that the possession of a Royal Aero Club certificate does not necessarily mean that the holder is an expert pilot, for there is invariably a considerable amount to learn before he becomes one. The newly-qualified pilot has as yet only been allowed out in relatively calm weather, and has yet to know what it is to fly in a really bad wind. There are also to be mastered machines which fly somewhat faster than those he has learnt on. As a matter of fact, it is doubtful whether anyone really finishes his tuition, for no one is so wise that he cannot be taught something new, and the best pilots of to-day have still much to learn and many stiff problems to overcome.

Flight, June 28, 1913.

A MAN AND A MACHINE.

THINGS move with remarkable swiftness in aviation. It is speed everywhere. Aviation itself has come upon us with remarkable speed. Aerodromes crop up in the form of a field and a couple of sheds, and in a few short months, before we seem to have time to look round, we have a fashionable racecourse and "White City" combined. Pilots come and go. The pilot of to-day is the memory of to-morrow, and the learner of yesterday is the man of the moment. Only a few weeks ago and Chevilliard was making us catch our breath with his remarkable flying on the Henry Farman at Hendon, now it requires something of an effort to remember just exactly what it was he used to do. We have not forgotten him, of course, but other men have come along to hold our attention, and we are essentially creatures of the moment. I first saw Sydney Pickles at Salisbury, only last year - a pupil - a learner. Nobody seems to take any notice of pupils, but some of them have a way of coming along and forcing themselves into a position where we not only have to notice them, but admire them. They seem to slip from the embryo to the concrete in a few moments, without any intermediate stage, and Sydney Pickles is one of them.

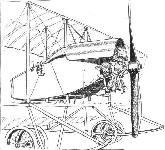

After Salisbury, he next appeared at Brooklands, and all I noticed about him was that he still wore the same hat with the striped band, and seemed very earnest about it all, but did not do much. Then little bits of news began to filter through. "Pickles was flying this machine" or "that machine." Pickles seemed to be flying all machines, everywhere. Then he got to Hendon. A few days, and he had taken out the little Caudron monoplane, that fast little machine which nobody seems to care to tackle, and flown it to Brooklands and back, in what I believe to be record time for the out and home flight: 12 1/4 minutes out, and 17 minutes back over a course of 21 miles - 42 miles in 29 1/4 minutes, with, and against the wind, surely a fine flight. Then came the Caudron biplane, the Handley Page, the Bleriot, and now the Caudron again; and, Pickles, this is your machine in my opinion. It is very noticeable, as time moves on, how certain pilots take to certain machines, and stick to them. We have Hamel on the Bleriot, Pierre Verrier on the Maurice Farman, Chevilliard on the Henry Farman: pilots who fly those machines and no other; and this is, I think, as it should be, for no pilot flies every machine equally well. It is a combination of man and machine, and the men who are our greatest flyers - the men who earn the most money - the men whose names ring throughout the world, are the men who have found the machine to suit them, and stick to it; and for you, Sydney Pickles, it is the Caudron biplane, take my word for it. It has not been my pleasure to see other pilots of the Caudron outside this little isle, so I cannot say how they handle their machines; but I am sure that could our friend Rene Caudron have been at Hendon on Sunday week and have seen Pickles on the new Hewlett and Blondeau British-built 45 h.p. biplane, it would have done his heart good; it was wonderful.

Now as to the machine. It is the second of three built and building for Mr. Ewen, by Messrs. Hewlett and Blondeau, under licence from Caudron Brothers, and as a piece of workmanship leaves nothing to be desired, and could not have been beaten by Caudrons themselves. Could they see it, they would feel pleased and proud that the building of their machines in England had got into such good hands. I had a good look round it, and I had to admit that I had never seen a machine which surpassed it for the excellent way in which everything had been carried out. There is not one little part in the whole machine which one could point to and say that it might have been better done. It has been built, of course, exactly on Caudron lines, and coloured the "Caudron" blue, but owing to the slight yellow tint of the dope, in the air it assumes a pale green colour, and looks remarkably pretty. With the 45 h.p. Anzani engine now fitted, it is remarkably fast, and climbs like a rocket. I do not think I ever saw a biplane - with the possible exception of the Sopwith tractor - climb quite so rapidly. I should like, just as a sporting event, these two machines matched one day in an altitude contest, say, of five minutes' duration, which, taking into consideration that one is of 80 h.p. and the other only 45 h.p., should put up a most interesting event. I think little sporting matches of this description would create a deal of interest, and be very instructive.

And now for the machine and the man, as a combination. On the signal to let go, the machine ran a short, a very short, distance, and leapt into the air - simply leapt, there is no other word for it. In half a circuit of the aerodrome, Pickles had got her up to a great height, and in a very few minutes he was circling at an altitude of well over 3,000 ft. Then, right over the centre of the grounds, he commenced a spiral corkscrew dive of such small radius that from the ground it looked as though the machine was turning in very little over its own length, and diving at an angle that looked appalling. Round and down, down and round it came, accompanied every few seconds by those momentary little puffs from the engine, until when within less than a hundred feet of the ground she flattened out splendidly, and went sailing off round the aerodrome. Coming back to near number one pylon, at a height of only about fifty feet, Pickles now set her to climb at a most terrific angle, and held her to it for so long that we on the ground thought he must surely overdo it, particularly as he was flying against a very strong head-wind. He must have made that poor little 'bus climb at least three hundred feet in one great slanting run, before getting on to an even keel, and it looked too much, though Pickles says it was not, and that he could feel her pulling all the time. Several more flights of the same character completed that day's performance, surely one of the most sensational flying exhibitions put up at Hendon since Chevilliard left us, and gave us a chance to breathe again. A wonderful pilot - a wonderful machine! The Pickles-Caudron combination should not be separated.

H. E. S.

Flight, September 20, 1913.

THE AERIAL DERBY.

PILOTS AND HOW TO RECOGNISE THE MACHINES.

No. 3. The Caudron Biplane

is the smallest biplane entered, and is of the tractor type, i.e., the propeller is situated in front of the main planes. The twin rudders are placed on top of the tail plane.

THE MACHINES, WITH SOME DETAILS.

No. 3. The 60 h.p. Anzani-Caudron biplane is remarkable chiefly for its small size - the span of the upper and lower planes are respectively 30 and 23 ft. - and for the characteristic Caudron flexible trailing edge.

It is a very reliable and steady machine, and its comparatively small initial cost, together with its excellent flying qualities and small size, make it one of the most popular biplanes built.

Flight, May 2, 1914.

AVIATION IN NEW ZEALAND.

JUDGING from some details which are to hand from Mr. J. W. H. Scotland, who has been flying a 45 h.p. Anzani-Caudron out there, New Zealand is anything but an aviator's Paradise. In spite of many difficulties, however, Scotland, on March 6th, succeeded in making a splendid flight of about a hundred miles from Timaru, South Canterbury, to Christchurch. After a preliminary flight at 6.30 a.m. at Timaru, Scotland effected a few adjustments and got away on his journey at half-past eight, the machine quickly rising to a height of 2,500 feet. When passing over Temuka a parcel was delivered by being dropped from the aeroplane, and then, as the conditions were very bumpy, the machine was elevated to 5,000 ft. There was no improvement, however, and Scotland decided to come down at Orari, where several adjustments were made to the machine, and it was not until 3.20 that the re-start was made. Then owing to the gusty wind Scotland went up to 6,000 ft. Finding no improvement he came down to an altitude of about a thousand feet, where the atmosphere was calmest, he reached Christchurch at 5 o'clock, and after circling round the town made a fine landing at Addington. During the journey both the Caudron biplane and the Anzani engine performed splendidly in spite of having to fight their way through most trying conditions. Interviewed after the flight, Mr. Scotland said that if he had not been mounted on such an excellent combination, he would have come to grief several times, as the wind from the hills seemed to form funnels and whirlpools which tossed the little Caudron about like a cork on the sea. On March 21st Scotland was at Wellington, and arranged to give an exhibition at the Athletic Park. The weather, however, was too bad, and the crowd which assembled were given tickets for the following Tuesday. On Sunday and Monday the weather was comparatively calm, but in view of the arrangement made with the ticket holders Scotland was asked not to go up. On Tuesday the weather was bad again, and it was decided to postpone the flying until the following afternoon. Then there was an improvement, although the wind was still very gusty. At half-past three Scotland decided to make a start, and after running for a short distance across the ground, the machine rose into the air. The ground was very restricted, however, and it was necessary to turn, and then it was that the utter unsuitability of the ground as an aerodrome was seen. The wind from the surrounding hills, which was broken into descending currents, eddies and puffs, made it practically impossible for any progress to be made. Realising that it was impossible to go on, Scotland very pluckily, by a great deal of exertion, got the machine over Newton Park, and eventually landed between the branches of two pine trees, the machine being suspended about 20 ft. from the ground. The nacelle and engine were practically undamaged, but, of course, the ends of the planes were crumpled up. Scotland himself climbed down one of the trees, and barring one or two rather severe cuts and bruises, was not very much the worse for his adventure. It was an unfortunate end to what promised to be a most successful tour of the country, and it is to be hoped that some patriotic New Zealanders will come forward with financial assistance to enable Scotland to continue his very useful work for the cause of aviation in New Zealand.

In the meantime, Mr. A. W. Schaef, who, as our readers will remember, has built a monoplane, fitted with a 35 h.p. Y Anzani, which was illustrated in these pages some months ago, has made one or two short flights at Lyall Bay and at Newton Park, Wellington, New Zealand. On March 16th, three flights of about 100 yards each at a height of 20 ft. were made over the beach at Lyall Bay, but unfortunately in landing on the last one a part of the chassis gave way with the result that the wings and propeller were damaged. Mr. Schaef, who, it will be recalled, is the representative of General Aviation Contractors, Ltd., in New Zealand, immediately set to work to get the machine repaired, and hopes that it will not be long now before he is able to make some really long flights.

Flight, May 22, 1914.

THE AERIAL DERBY.

THE PILOTS AND HOW TO RECOGNISE THE MACHINES.

No. 1. The 35 h .p. Caudron Biplane.

This machine is of the tractor type, but may be easily identified by the very short nacelle and by the tail booms, of which the lower ones are continued forward to form the skids.

THE MACHINES AND HOW TO RECOGNISE THEM.

No. 1. The 35 h.p. Caudron Biplane. - This machine is a standard type Caudron biplane, already familiar to our readers through descriptions in FLIGHT. The only alteration is that a different type nacelle has been fitted in order to accommodate the 35 h.p. Statax engine. Great interest will attach to the performance of this machine, since it is the first public appearance of the Statax engine. It will be remembered that a small engine of this type was exhibited at the last Olympia Aero Show, when it was described in these columns.

Flight, July 24, 1914.

EDDIES.

Mr. J. J. Morgan, manager for Mr. A. W. Jones, who took a British-built Caudron biplane, 35 h.p. Anzani engine, out to Australia, where Mr. Jones has been flying it for about eighteen months, sends us the following interesting communication:-

"When being shipped from London the machine was badly smashed, and had to be practically rebuilt on arrival at Brisbane, Queensland. Since then Mr. Jones has given exhibitions at all the principal towns in Queensland, N.S.W. and South Australia. One of his best flights was made in South Australia on January 2nd of this year, when he flew over Adelaide at a height of 3,500 ft., covering about 20 miles. He is practically the pioneer of aviation in Australia, as outside of Sydney and Melbourne there had not been any flying at all. We have found great difficulty in securing grounds especially in such out-back places as Charters Towers (North Queensland) and Broken Hill (N.S.W). The temperature at the latter was 115 degrees, rather trying for an air-cooled engine. The Caudron has covered in all about 3,000 miles in Australia, and has proved itself ideal for flying, its one great drawback for exhibition work being the cost of transport; in a country like this, where you have to travel thousands of miles, it costs a small fortune in freight. The little 35 h.p. Anzani has done exceptionally well, not having given the slightest trouble till we came to Perth a week or so ago, when we were unable to get the right lubricating oil. No doubt the weight of the pilot (9 stone) has something to do with its success. Perhaps these notes and photo, may be of use to you, and I may state that I have come across your paper in all sorts of outback places in Australia. Mr. Jones is giving exhibitions in Perth and Kalgoorlie and other towns in this state."

Flight, August 21, 1914.

EDDIES.

SINCE I referred recently to the doings of Mr. A. W. Jones and his Caudron, in Australia, a further letter is to hand from his manager, Mr. John J. Morgan, which throws some sidelights upon the conditions under which exhibition is carried on down under. From the time the machine arrived in Australia it, up to July 10th, had been erected and dismantled 28 times, while it had travelled 24,200 miles by rail and 21,000 miles by boat. On June 29th, Mr. Jones made some flights at Boulder, W.A., by permission of the Colonial Secretary, and 25 per cent, of the proceeds went to enrich the "Worn-Out Miners' Fund." He flew to Boulder from Kalgoorlie racecourse, passing over the gold mines en route, and afterwards returned to Kalgoorlie. After giving exhibition flights in North Queensland Mr. Jones proposes to fit a 50 h.p. Gnome in his machine and attempt to fly from Melbourne to Sydney.

Flight, August 28, 1914.

An Australian-built Machine.

A FEW details have been sent along by the General Aviation Contractors, Ltd., regarding the work of Mr. Delfosse Badgery, who it may be recalled is agent for G.A.C. specialities, Anzani motors, Emaillite, &c. in Australia. Since returning to Australia after taking his brevet on an Anzani-Caudron at Hendon last January, Mr. Badgery has designed and built a biplane which has proved a very fine flyer. On July 19th, in one of several trials round Sutton Forest and Wollondilly, he went to a height of over 2,000 ft., climbing the first 1,000 ft. in 2 mins. 45 secs. At the first favourable opportunity Mr. Badgery intends to fly from Moss Vale to Sydney, N.S.W. The machine is fitted with a 40-45 h.p. 6-cyl. Anzani, 1914 type, a Rapid propeller, is Emaillite doped, and wherever possible the fittings are British made.

Flight, October 16, 1914.

EDDIES.

A further batch of news is to hand from Mr. Delfosse Badgery, the Australian agent for the G.A.C., dealing with his latest activities on his Australian-built Anzani-engined biplane, which was described in these pages recently. On August 12th last he made a cross-country flight from Moss Vale to Goulburn, a distance of 49 miles. At the latter place he later gave some very successful flights. The following is an extract from a letter sent by Mr. Badgery to the Delfosse Badgery Aviation Co., in which he describes his trip :-

"At 10 minutes to 7 a,m., I had the aeroplane in the straight near the house, and at 7 I gave the signal, and all hands let go. It was interesting for me, because the 'bus had her tanks brim-full. It made no difference to her marvellous lifting power, however, and two circuits of Mewbury was sufficient to give a mean altitude of 1,500 ft., which grew from there to Carrick, where I had attained 12,000 ft. to descend, as I was beginning to lose the use of my hands, owing to the intense cold.

"Not long after this the engine back-fired for some time, and the unfired gas discharging it into the exhaust pipe was fired by the other explosions entering, and this gave rise to a series of loud reports just like huge pistol shots.

"I have heard since a small boy ran into one house and said that there was a 'haroplane lettin' off' crackers coming this way.

"My entrance to the town was at 8,000 ft. - rather sorry I was to lose that other 4,000 - but I could not stand the cold.

"After leaving home behind, the smoke of the limited express was visible about at Kareela, so I steered for that part of the globe direct, where I afterwards picked up the railway line, like a pencil track in amongst a dense forest. It was then that I saw the smoke of the second express, emerging from the hills on to the plain near Carrick. The country was beautiful; Marulan was approaching me slowly on the left, and with the altimetre creeping round over the thousands a feeling of more security came over me, as I knew then that all the dangerous country was passed over.

"Goulburn itself was now very distinct; could see it well, and would have been able to tell it was a big town in a strange land, and yet I was 20 miles away.

"A huge vol plane concluded my flight."

One of the latest machines of the Caudron type to be turned out was tried last week by Mr. L. Hall, at whose works it has been built. This Anzani-engined machine leaves the ground after a very short run, and appears to possess remarkable climbing powers for a machine of only 35 h.p. It will be used as a brevet machine at the Hall school after the pupils have familiarised themselves with the handling of the older biplane of the same type which has now been in use at the school for some time.

Flight, January 1, 1915.

EDDIES.

News reaches us again of the doings of Mr. Delfosse Badgery, who has been giving numerous exhibition flights in various portions of the Southern Hemisphere. The latest accounts of his evolutions appear in the Tasmanian Mail, whose reporter has evidently still a good deal to learn about aeroplanes, to judge from his more picturesque than technically correct descriptions of Mr. Delfosse Badgery's exploits. According to the abovementioned paper, Mr. Badgery had arranged to give demonstrations, which incidentally were the first to be given in public in Tasmania, at the show ground at Elwick. After chronicling the notabilities present at the meeting in the approved style, this valuable journal proceeds to describe the first flight, in the following words :-

"After a considerable wait, the machine, a biplane of the Cordarian type (!) driven by a 45 h.p. Anzani motor, was pulled out from under its canvas tent on to the oval, running along the ground easily on its rubber-tired chassis wheels, and the City Band played 'See the conquering hero comes.' The airman, clad in black rubber overalls and the regulation tight-fitting, bonnet-shape head-gear of the same material, took his seat on the biplane. The tractor screw (unlike the monoplane, the biplane screw acts as a tractor in front, instead of as a propeller) having been set spinning round, the four men holding the machine back released their grip, and the machine instantly shot forward, ran along the ground about 30 or 40 yards, then rose rapidly and gracefully, like a soaring bird over the land, in the direction of Glenorchy."

Flight, January 8, 1915.

EDDIES.

MR. A. W. JONES continues to do a lot of good missionary work in Australia, where, it will be remembered, he is flying a Caudron biplane. In a letter from Brisbane, Mr. J. Morgan, his manager, gives the following account of some of Mr. Jones's experiences :- "People came 200 to 300 miles to see the flights in North Queensland, the Caudron being the first machine to fly in 'Caions.' It was a very bad day, blowing 40 m.p.h., and the country round was heavily timbered. After going about 10 miles Mr. Jones decided to land in a sugar plantation, but was upset before reaching it. It took about two hours to find the machine, as we had to force our way through dense scrub. The pilot was not anywhere about, and we got rather scared, as there was a swamp infested with alligators nearby. (I shot one myself two days afterwards, measuring 12 feet.) Mr. Jones eventually turned up at a Chinaman's camp, where, it appears, he had been carried unconscious by two Chinamen, but he quickly recovered and was quite unhurt. It took two days to rescue the bits of the machine, as we had to chop our way through two miles of scrub.

"Some aboriginals put us on the track of the machine, saying that they saw 'big hawk' fall, but we could not persuade them to go anywhere near it."

One of the photographs which appear on this page is helpful in emphasising Mr. Jones's little adventure.

Flight, February 5, 1915.

EDDIES.

I do not happen to know who at present holds the record for the shortest period of tuition, or whether it still stands to the credit of Lieutenant N. Pemberton-Billing (his would assuredly take a lot of beating), but a very creditable performance was that of one of the pupils at the Hall school, Mr. J. Lloyd Williams, of the Public Schools and University Corps, Royal Fusiliers, who has just obtained his brevet after only 163 minutes, or 2 hours 43 minutes, tuition, covering a period of 13 days. Mr. Lloyd Williams was in camp at Epsom with his Battalion, and was therefore only able to attend the school once or twice a week, having to obtain special permission from his commanding officer each time. The "ticket" was a very good one, and in the altitude test the barograph registered 1,650 ft. By the way, I hear that quite a number of the members of this corps have joined, or are joining, the R.F.C., so that we may expect to hear further of some of them if Mr. Lloyd Williams may be taken as a fair example of the corps.

"AEOLUS."

Показать полностью