D.James Schneider Trophy Aircraft 1913-1931 (Putnam)

Deperdussin

The winning aircraft of the first Schneider Trophy contest appears to have had no designation other than the name of the man who - ostensibly - paid for its design and construction. It was Armand Deperdussin, a French silk broker who, in 1909 had, first, given financial support to Louis Bechereau, a young design engineer obsessed with the idea of speed, and then, a year later, acquired the company which Bechereau had helped to found and changed its name to Societe pour les Appareils Deperdussin or SPAD. The address of the company, prophetically, was 19 rue des Entrepreneurs, Paris. A flying school also was established at Courey-Betheny (Marne). This was not the SPAD company which created many outstanding First World War aircraft. Thus the aeroplane flown to victory on 16 April, 1913, at Monaco was designated simply Deperdussin.

Louis Bechereau, who designed the Deperdussin racing land monoplane in 1912, had earlier studied the designs of Louis Bleriot and Edouard de Nieport. He believed that he could improve on their monoplanes which featured enclosed fuselages and cockpits and streamlined struts. His faith in his abilities was justified when his little 5-94m (19ft 6in) span monoplane, powered by a 160 hp Gnome fourteen-cylinder two-row rotary engine and piloted by Jules Vedrines, won the 1912 Gordon Bennett Aviation Cup in Chicago at a speed of 106-02 mph over a 200 km course; and he repeated this success the following year at Reims when Maurice Prevost flew the Deperdussin F.1 to victory with a speed of 129-79 mph.

A single-seater Deperdussin type B.1, powered by a 50hp Gnome seven-cylinder rotary engine, sold for the equivalent of £960. Built entirely in wood, the first Deperdussin racing seaplane featured a fuselage of monocoque - literally ‘single-shell’ - construction which was of nearly oval section along its length from just behind the engine almost back to the sternpost. This load carrying ‘single-shell’ skin fuselage was built up from three layers of gin thick tulip wood veneers which were glued together over a mandrel or mould in the form of the fuselage shape. The outer surface then had linen fabric glued to it and the shell was removed from the mould. A second layer of linen fabric was then applied to the inner surface and several coats of varnish applied to the linen, each being carefully rubbed down after drying to produce a very fine smooth finish. This method of fuselage construction was used in the Deperdussin seaplane specially prepared for Maurice Prevost to compete in the 1913 Schneider Trophy contest. A fundamental difference between the fuselages of the earlier landplane and the seaplane variants was that the latter was almost circular in section. Of similar depth, the longer fuselage of the seaplane also had a better fineness ratio. This type of construction also provided great strength in the forward part of the fuselage where there was a large cutout for the cockpit and internal mountings for the fuel tank, the controls and the wing spar attachments. It also provided improved protection for the pilot in the event of a crash. The Gnome rotary engine, which was mounted on a wooden bulkhead, revolved inside an aluminium cowl and drove a two-blade mahogany propeller having a large bull-nosed spinner which left only a small annular gap between it and the inside diameter of the cowl for cooling airflow.

Lateral control of the aircraft was through wing-warping, and ailerons were not fitted. The spars and ribs were made of ‘selected timber of great strength’ according to a contemporary description, spruce for the spars and pine for the 23 ribs in each wing. The constant-chord wing had sharply backward-raked wingtips and a stepped-forward leading edge at the root. The linen covering was heavily doped to tighten and protect the material and to prevent distortion of the wooden structure beneath. The wings were each warped by three or four steel cables and had bracing wires running from the top surface to a double tripod-type structure mounted on top of the fuselage in front of the pilot; return control cables and lift wires were attached to the undersurface of the wing and to the floats. The control cables and bracing wires were reputed to be capable of withstanding loadings of up to 20 times those experienced in straight-and-level flight. Turnbuckles were fitted on all cables and wires to enable the wings to be trued-up when rigging the aircraft. It is recorded that ‘a patent device was embodied in the control wires attached to the rear spar which prevented distortion of the wing in gusts but enabled the pilot to have exceedingly powerful and effective warp’. The wing had a medium-cambered section with some washout toward the tips.

The cantilever cruciform tail unit was made of spruce spars with pine ribs and leading and trailing edges, and covered with heavily doped linen fabric.

Spruce was used for the heavily stayed and wire-braced float attachment struts, which were given a streamlined section, and the float spacer bars which were varnished and rubbed down to produce a fine surface finish. The box-section wooden floats had a flat planing surface and were mounted with their leading edges canted upwards to help break the ‘stiction’ between the surfaces of the water and the floats. As the centre of gravity was well aft, there was a small stabilizing float under the tail.

The control system was patented by Bechereau and was the outcome of careful study and experience with the smaller landplane racer. A wheel was mounted at the top of two arms hinged at their lower ends to the wooden monocoque fuselage. Moving the wheel backwards and forwards operated the elevators, and turning the wheel warped the wings to effect lateral control. The rudder was cable-operated by means of an orthodox rudder bar.

Deperdussin landplane racing aircraft won the 1912 and 1913 Gordon Bennett Aviation Cup races. During the second race Maurice Prevost, in a short-span Deperdussin F.1, became the first man to travel more than two miles in a minute. Deperdussins also established ten world speed records, raising the speed to 203-72 km/h (126-59mph). Sadly, Armand Deperdussin had built his achievements on the sands of money which was not his. He was arrested in his Paris flat on 5 August, 1913, and subsequently given a five-year suspended prison sentence following the discovery of his involvement with fraud totalling more than £1 million. Deperdussin ultimately shot himself in a Paris hotel on 11 June, 1924.

When Deperdussin’s empire had crumbled, Louis Bleriot took over ownership and changed the company name to Societe Anonyme pour l’Aviation et ses Derives. The acronym of the name remained Spad and it was for this organization that Louis Bechereau created designs for the renowned Spad fighters of the First World War.

Single-seat twin-float racing monoplane. All-wood construction with monocoque fuselage and fabric-covered wings and tail unit. Pilot in open unfaired cockpit.

1913 - one 160 hp Gnome fourteen-cylinder twin-row air-cooled rotary engine driving a 2-8 m (9 ft 3 in) diameter two-blade fixed-pitch mahogany propeller; 1914 - one 200 hp Gnome eighteen-cylinder twin-row air-cooled rotary engine. Fuel: 136 litres (30gal) in a fuselage tank.

Span 8-95m (29ft 4 1/4in); length 5-75m (18ft 10 1/4in); wing area 9sqm (96-87sqft). Dimensions for 1913 version.

Empty weight 290 kg (639lb); loaded weight 400 kg (882lb); wing loading 44-4kg/sqm (9-1 Ib/sq ft).

Maximum recorded speed 104 6km/h (65 mph).

Production - one long-span aircraft built during 1913.

Colour - Prevost’s Deperdussin for the 1913 contest was blue overall with the contest number 19 in large white figures on each side of the fuselage just forward of the tailplane.

Показать полностью

L.Opdyke French Aeroplanes Before the Great War (Schiffer)

Deleted by request of (c)Schiffer Publishing

The seaplanes were equally famous;

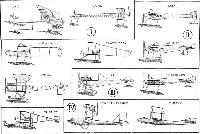

1. No 11 at Deauville - a double 3-strut pylon, each float strut with 2 single diagonal braces attached at both inside and outside edges of the floats, big (1 or 2?) seat cockpit, monocoque fuselage, fully-cowled engine and big spinner. The triangular fin and rectangular rudder did not extend below the aft fuselage. (Type H?)

2. Tandem 2-seater with long double cockpit, long flat-sided fuselage, wing-root cut-outs, float attachments, complex 2-tiered assembly of struts with 2 horizontal bars above each float, 2-triangle pylon, small triangular fin and angular rudder with vertical trailing edge. One flew at Geneva in August 1912; another - perhaps the same aircraft, flew in the same month at St Malo.

(Span: 12.5 m; length: 8.5 m; loaded weight: 640 kg; speed: 100 kmh; 80 hp Gnome)

3. No 19 at Monaco, 1913 - tandem 2-seater with a single long cockpit, wing cut-outs, double 3-strut pylon, each strut float with 2 pairs of diagonal supporting struts, fin and rudder symmetrically above and below aft fuselage, full cowl and large spinner. A similar - the same? - machine flew in the Paris-Deauville race, carrying the number 4.

4. Shown at the 1913 Paris Salon, the seaplane featured a monocoque fuselage with nearly flat sides, a bathtub 2-seat cockpit, a 2-triangle pylon, fully-cowled engine and spinner, each float strut with a pair of diagonal supports. The fin and rudder were set symmetrically above and below the fuselage.

5. At Monaco, 1914 - flown by Prevost, this one featured simple N-strut attachments to the float centerlines, a 2-triangle pylon, and a single-seat oval cockpit in the monocoque fuselage. It carried the number 4.

6. Also at Monaco in 1914, a similar machine with a 4-strut pylon and rectangular rudder.

7. Type Tamise, in 1912, an odd 2-seater with flat sides but a fuller, more streamlined fuselage than the pre-monocoque fuselages, 2 separate cockpits in tandem, angular rudder equally above and below fuselage - with no fin! The float attachments were similar to No 2, above. In fact, this machine was built by De Brouckere, in Belgium, under license.

8. Again, with float attachments like No 2; fuselage shape also like #2; fin and rudder like #3; 2-triangle pylon. One photo shows it in front of yachts.

Показать полностью

M.Goodall, A.Tagg British Aircraft before the Great War (Schiffer)

Deleted by request of (c)Schiffer Publishing

BRITISH DEPERDUSSIN SEAGULL

This was an original design by the British branch of the company, of which the Admiralty ordered two. The fuselage was of monocoque construction and the wings, which were quite unlike any earlier Deperdussin, had an external tubular steel bracing structure below and no overhead bracing. The spanwise members of this structure were broad fairings of aerofoil section intended to contribute lift, and enclosed the aileron control cables.

One aircraft, exhibited at the Aero Show at Olympia in February 1913 was fitted with a broad central step-less float, to which springing was to be added. Small floats of streamlined shape were fitted at the extremities of the bracing girder and a broad float of aerofoil section, with water rudder, below the tail. The machine tested later on the River Blackwater was fitted experimentally with twin step-less main floats and no wingtip floats.

The crew sat in tandem, with the observer in the front, and provision was made to start the engine from the front cockpit. Full chord, wingtip ailerons were pivoted between the wing spars. The engine was a 100hp Anzani.

Although the Admiralty had ordered two machines these were canceled when the prototype proved to be unsatisfactory and the British company failed. A 100hp Anzani-engined landplane, which became No.885, and may have been one of these machines, was impressed in August 1914.

Data

Span 42ft 6in

Chord 6ft 8in tapering to 7ft 2in

Length 30ft 6in

Area 280 sq ft

Area tailplane 30 sq ft

Area elevators 16 sq ft

Area rudder 7 sq ft

Weight 1,300lb

Weight allup 1,980lb

Speed 55 mph

Price ?1,500

Показать полностью

Jane's All The World Aircraft 1913

BRITISH DEPERDUSSINS. British Deperdussin Aeroplane Co., Ltd., 39, Victoria Street. Westminster, London, S.W. School: Hendon.

Chairman: Admiral The Hon. Sir E.R. Freemantle, G.C.B., C.M.G. Managing Directors: Lieut. J.C. Porte, R.N., D. Laurence Santoni. Secretary: N. D. Thompson.

This firm handles the French models of Deperdussins, but has in addition a special hydro-aeroplane of its own, of which one was built in 1912. Details of this special machine are:--Length, 27 feet 10 inches (8.50 m.) Span, 42 feet (12.80 m.) Area, 290 sq. feet (27 m?.) Weight, total, 1,800 lbs. (816 kg.); useful, 1,250 lbs. (566 kg.) Motor, 100 h.p. Anzani. Speed, 67 m.p.h. (110 k.m.) Other models sold by the firm are of French type exactly (see FRANCE).

Показать полностью

Журнал Flight

Flight, February 8, 1913.

WHAT THERE WILL BE TO SEE AT OLYMPIA.

THE MACHINES.

The British Deperdussin Aeroplane Co., Ltd.,

Will be showing two monoplanes, a two-seater hydro-monoplane, fitted with one of the new 10-cyl. 100-h.p. Anzani motors and a 50-h.p. Gnome engined single-seater monocoque. The former of these two machines is British-built. It is at the present time nearing completion under the supervision of Lieut. J. C. Porte and M. Koolhoven, at the firm's excellently equipped works at Highgate, N. The machines chief peculiarity is that the wings are braced, not in the manner usually associated with monoplanes, but similarly to the Etrich monoplane that Lieut. Bier flew in connection with the Daily Mail Round Britain prize. Each wing is built up of two sections, the entering section, perfectly rigid, braced with a steel tubular understructure, and the trailing section, extremely flexible, which is hinged to it, and which is alone used for warping. The body of the monoplane is of the monocoque type; really it should be termed a bicoque because the shell is made in two sections, an upper and a lower, which are afterwards joined together.

<...>

Flight, April 26, 1913.

REFLECTIONS ON THE MONACO MEETING.

Deperdussin.

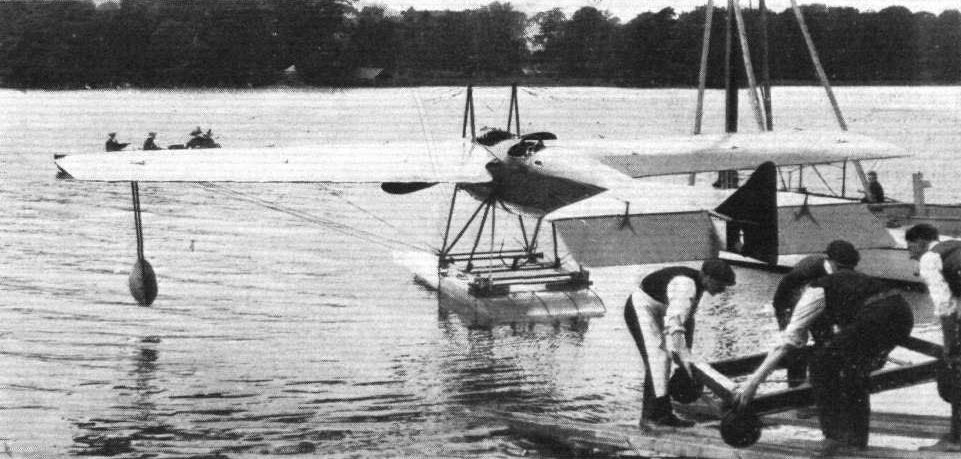

The Deperdussin monoplane at Monaco was constructed on similar lines to the land machines, with the exception, of course, of the under-carriage portion by which the body was attached to the floats. Two floats were employed, and the attachment was rigid. Massive limber struts passed from the shoulders of the body to the middle of the decks on the floats, and lateral stiffness was obtained for this fastening by bracing the sides of the floats to the heads of the struts by steel wires. Tubular steel struts were also inserted diagonally from the sides of the floats to the middle of the principal struts.

Although several Deperdussin monoplanes were to be seen at Monaco, that piloted by Prevost was principally in evidence. It had a 160-h.p. 14-cyl. Gnome, and a minor detail of interest was the presence of a longitudinal air intake-pipe for the carburettor situated beneath the body with its orifice facing into the propeller draught.

Flight, May 10, 1913.

THE DEP. HYDRO-MONOPLANE.

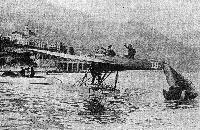

AT the time of the last Aero Show at Olympia we gave a short description of the hydro-monoplane exhibited by the British Deperdussin Aeroplane Co,, Ltd. Since then this machine has been put through an extended series of trials over the Blackwater, near Osea Island and his, we understand, proved very successful.

One of the most interesting features of this machine is the immensely strong wing-bracing, effected by an understructure of steel tubing. It will be remembered that the Etrich monoplane, flown by Lieut. Bier in the Circuit of Britain, had a somewhat similar system of bracing, but the girder of the Etrich machine only partly supplanted the ordinary triangulation bracing, whereas in the "Seagull," as this latest Dep. hydro-monoplane has been named, this structure has been made of sufficient depth to do away with all overhead bracing.

One objection which might be urged against this system of construction is that it would appear to offer head resistance, but the designers claim that it offers no more head resistance than the usual wire bracing, which, as is well known, vibrates considerably, when the machine is flying, and the fact that this machine flies at about 65 miles per hour would seem to indicate that their claim is justified. This method of wing bracing certainly has several advantages, for it gives a structure of almost equal strength to that obtained in biplanes, and greatly minimises the compression in the spars.

It will be easily understood, that with this method of wing construction there are several difficulties which militate against the use of the warping system of control, and these have been overcome by fitting ailerons similar to those employed on some of the earlier Bleriot monoplanes, and later on the Goupy biplanes, to the wing tips. They have been found to work quite well, and this method does away with the weakening of the wing through constant deformation.

The fuselage is of the monocoque type and is very interesting, for it is constructed of wood veneer without any longerons, struts and cross-members or diagonal wiring of any kind. It is built in two halves, each half being built on formers, from narrow strips of tulip wood. Three layers of this wood are used, the strips of the two first layers running at right angles to each other. The different layers are glued together and the whole covered with two layers of strong fabric.

At the rear of the fuselage is carried the empennage, of very neat design. The tail plane - cambered top and bottom, and set at a positive angle of incidence - is secured to the fuselage by steel bands passing underneath the body.

The elevators are pivoted around a steel tube running along the trailing edge of the tail plane, and the levers operating them are accommodated inside the body and the tail fin respectively. The control wires to the rudder are enclosed in a similar way, so that in no instance are the control wires exposed to the effect of the air or sea water.

When at rest the tail is supported by a float situated some six feet in front of the rudder post. This float is built of 3-ply wood, covered with fabric, and painted with boat varnish, and is of such a section that it will support its own weight in flight.

Two main floats support the machine on the water, but a similar machine, which is now going through the works, will be equipped with one large central float, as the designers contend that a single float has several advances especially in a rough sea, and they have fitted this machine with two floats for experimental purposes only. Three-ply wood is the material used in the construction of the floats, which are connected to the body by two U-shaped frames of multi-ply wood. The floats are flat-bottomed, that is to say they have no step, the designers maintaining that the wings of a hydro-aeroplane should perform the functions of steps in raising the machine when sufficient speed is acquired. Inside the body, very comfortable accommodation is provided for the pilot and observer, the latter occupying the front seat. From here he has an excellent view of the sea beneath, as he is situated well forward in the body, and the wings have been cut away near the body from the leading edge to the front spar. In front of him is a starting handle, by means of which he can start the engine without leaving his seat.

Just behind the engine-plate and inside the body is a service tank, divided longitudinally by a partition, the two compartments containing oil and petrol respectively. A small pump, driven by a miniature propeller situated outside the body, and working in the slip-stream of the propeller, feeds petrol to the service tank from a main tank inside the body under the pilot's cockpit. By means of gauges on the Elliott instrument-board, the observer is always able to ascertain if petrol is being pumped up regularly. Should one of these gauges become broken, they can be instantly put out of action, so as to avoid an escape of petrol. Filling up the main tank is done from the outside through a filler in the side of the fuselage, so that there is no possible danger of spilling any petrol inside the body, where it might be accidentally ignited.

Underneath the mica wind screen in front of the pilot, and almost level with his eyes, is a compass, made by Kelvin and James White, Ltd. The pilot does not watch the compass card itself, but its reflection in a glass prism, which shows an enlarged view of a small part of the card.

Control of the machine is effected in the usual Dep. fashion by means of a hand wheel mounted on an inverted LJ shaped frame. From a drum on the hand wheel cables run to one arm of the bell-cranks situated on the chassis members. From the other arm of the bell-cranks cables pass through the streamline casing on the boom of the wing structure, around pulleys on the outer end of the boom and to the trailing edge of the aileron. Another cable, running from the leading edge of an aileron around pulleys on the boom and across to the other wing, interconnects the two ailerons so that when the angle of incidence is increased on one, it is correspondingly decreased on the other. The ailerons are pivoted around a steel tube which is secured inside the wings, roughly half-way between the two main spars.

A 100-h.p. 10-cyl. Anzani engine is bolted on to a steel capping plate on the nose of the machine. It drives directly a Rapid propeller of 8 ft. 6 ins. diameter.

Flight, July 5, 1913.

THE HOME OF THE "SEAGULL."

"COME down to Osea Island and see the 'Seagull,'" said Mr. Santoni to me a few weeks ago, and the invitation was no sooner extended than it was accepted. I might explain that although much has been learnt in the past from studying the ways of the gull, this particular visit had no connection with bird life, its purpose being to see that fine water-plane which was so much in evidence on the stand of the British Deperdussin Co. at the February Aero Show at Olympia. Having accepted the invitation, it was immediately arranged that the visit should take place on the following Sunday, and it may not lie uninteresting to readers of FLIGHT if I set down some of the incidents that befel us on that memorable trip.

On Sundays there is only one train goes that way, and it leaves Liverpool Street at eight-twenty-five ante, change at Witham for Maldon East, where on arriving the fun commences. Outside the station were a number of "flys." Why in the world they were ever so called we could not make out. (I have looked it up in the dictionary since and find "Fly: to shun, to avoid," so perhaps there is something in a name after all.) Certainly they are far remote from flying, though we had to take one to get there. The great trouble we had was to make a choice, but shutting our eyes we picked out one that had been - in about the mid-Victorian era - called a victoria. There really wasn't much wrong with it, provided one was easily pleased. A victoria was originally designed (good word) to accommodate three, including the driver. We were three inside and an equal number on the box, including the little daughter of our coachman, who was a lady "coachman." The footboard of the box had all disappeared except one small board, and as the child promptly went to sleep, our "coachman's" time was equally divided between trying to slip in the top gear when the horse wasn't looking, and preventing her offspring from slipping through the place where the floor ought to have been. That horse, by-the-bye, must have had a slipping clutch, judging by the way he took the hills. A three-mile drive, without exceeding the speed limit, got us safely to Millbeach, a village of two houses, one of which is an inn, where, as the tide was up, we had to wait for the motor launch to come from the island, about three miles away, to fetch us. When the tide is out it is no good waiting for the launch because there is no water, and the only way to get to the island is to walk or drive across a primitive causeway - the hard-staked out with seaweed covered posts in the bed of the creek, which, incidentally, is dangerous to undertake once the tide has turned, for it comes in with extraordinary rapidity, and flowing round the island attacks from both sides.

While waiting for our craft, we were much amused at the antics of a dog that is an expert at fishing. This sagacious canine will creep along the shore "speering" for plaice or soles, and having located one he springs in and catches it with almost unerring aim. We saw him catch two nice-sized fish in less than ten minutes, and I managed to secure a snap of him on his second attempt just as he lifted his head out of the water.

Climbing into the launch was quite exciting, as owing to the sloping shore one could not get close up, and one had first to step into a dinghy about the size of a cocked hat, and from that into the launch. As we were rather a large family, I had the pleasure of being towed behind in this cockle-shell, and as the wind was against the tide, with the help of the propeller they made things lively for me. However, from my position I was able to get a photograph of my tug, showing her churning away with Lieut. Porte guiding her destinies. On arriving at the island we found the mechanics busy fitting various little things to the waterplane, which is one of the most business-like jobs I have seen. It is no joke, however, if any special thing is wanted on Osea Island. By way of example: During the morning it was found necessary to send the motor launch to Heybridge, about four miles away, to fetch a small piece of steel from the local blacksmith. For me it was not so bad, as it enabled me to have another trip, this time not in the dinghy. Arrived at Heybridge we left the launch out in the tideway in charge of Mr. H. M. Brock - the plucky Hendon pilot who recently flew the baby Dep. from Hendon to Brooklands in a fifty-mile wind - and made for the shore in the dinghy. Having secured our cockleshell to a ring in the sloping wall, we started out to find the blacksmith, who we discovered, not under the proverbial spreading chestnut tree, but in his little weather-board cottage, surrounded by his hives of industry in the shape of various workshops. For this blacksmith is not of the common or garden variety. He, like those of his brotherhood, shoes horses and puts on cart wheel tyres, but he does not stop there. Far from it. In addition he is a boat-builder, a fitter of ships' and yachts' cabins, a constructor of portable houses, anything, in fact, from a hangar to a dog-kennel. Above all, he is the resident chief electrician of his own electric light generating plant, which, originally erected to supply his own workshops, has since been extended to light the houses of his fellow villagers. Having obtained what we wanted, on arriving back at the place where we had left the water, we found it had all run out and left our dinghy hanging by the nose half-way up the wall, and no water within yards of her. Being so small, however, we simply lifted our craft off the wall and my companion carried her in his arms, like a child, to the edge of the stream, and so back to the launch, where we found friend Brock supremely contented, stretched restfully out in the sun. The water had by this time run out as though somebody had made a hole in the bottom of the creek, and it was a race against time to get back to the island before we got left high and dry on the mud. Our engine was of 12 h.p., and having such a tide we slipped along pretty fast, our "crew" sounding the depth every few minutes with the boat-hook. It seemed most strange to be out on a stretch of water nearly two miles wide, and be able to touch bottom at 3 ft. or thereabouts. Halfway back we had only a little over 2 ft., and I began to wonder what it would be like to be stuck on the mud for twelve hours, and at the same time it came to my mind that there was only one solitary train back to London, and that at 7.14. However, we just managed to get back to the island with our screw stirring up the mud. Shortly afterwards the "Seagull" was wheeled by many willing hands down to the deep channel on the south side, where there is always plenty of water, and got afloat.

A waterplane on land has always struck me as being somewhat of an ugly duckling, with its big floats which raise it so far from the ground, but on the water I think a more graceful object it would be hard to find, and this one has a particularly pleasing appearance, looking for all the world like a huge grey swan.

With Lieut. Porte in the pilot's seat, the 100 h.p. Anzani was cranked up, and away she skimmed with seemingly a human sense of pride and joy at being in her native element.

Unfortunately, time and the Great Eastern Railway wait for no man, and we had to be content with a few trips, especially as we wanted to walk back over the ground, or, rather, mud, to Millbeach, just to see what it was like to tramp in the bed of the sea, like Pharaoh of old. At Millbeach we were picked up by our friend the antediluvian chariot and whirled back, at some ghastly speed hearing 3 to 4 m.p.h., to Maldon East. A change again at Witham, with a one-stop run to Liverpool Street, and we were back in the hub of the universe, after a most enjoyable day.

H.E.S.

Flight, December 13, 1913.

THE STANDS AT THE PARIS AERO SHOW.

DEPERDUSSIN.

Great interest naturally attaches to the Deperdussin exhibit mainly, perhaps, on account of the tremendous speeds which these machines have put up. It would seem that in the monocoque type the Deperdussin firm have found an entirely satisfactory fuselage construction, for the three machines exhibited on their stand are all of this type. Two machines for use over land are shown, one being the actual machine flown by Gilbert in his flight from Paris to the Baltic Sea (Rutnitz), a distance of 1,050 kilometres, which he covered in 5 hrs. and 11 mins., or at an average speed of over 200 kilometres per hour. The other land machine shown is the machine flown to victory by Prevost in this year's Gordon-Bennett race, and which was described in FLIGHT for November 22nd. A hydro-aeroplane, also of the monocoque type, completes the very interesting exhibit of the Deperdussin firm.

Показать полностью