Описание

Страна: Франция

Год: 1913

Варианты

- Caudron - C / D / E - 1912 - Франция

- Schwade - Caudron-Copy Biplane - 1912 - Германия

- Caudron - G.3 - 1913 - Франция

- Caudron - Type J - 1913 - Франция

- James - biplane - 1914 - Великобритания

- Ruffy-Baumann - biplane - 1914 - Великобритания

- В.Шавров История конструкций самолетов в СССР до 1938 г.

- J.Davilla, A.Soltan French Aircraft of the First World War (Flying Machines)

- L.Opdyke French Aeroplanes Before the Great War (Schiffer)

- Jane's All The World Aircraft 1913

- Журнал Flight

-

Журнал - Flight за 1913 г.

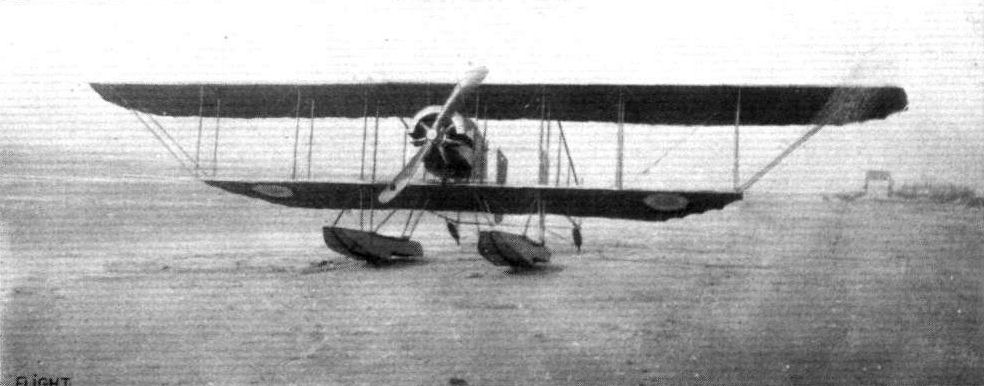

One of the new 80-h.p. Gnome-Caudron hydro biplanes supplied to the French Navy. The target-like devices painted below the lower plane are distinctive of machines belonging to the French maritime service.

-

Журнал - Flight за 1913 г.

AT DEAUVILLE. - The Caudron biplane just getting away from the starting stage in the French Government Waterplane tests.

-

L.Opdyke - French Aeroplanes Before the Great War /Schiffer/

Above: Another J, No 6 at Deauville, powered with an Anzani, and displaying twin double rudders.

-

Журнал - Flight за 1913 г.

Three-quarter front view of the Caudron hydro-biplane.

-

Журнал - Flight за 1913 г.

On left side, view of Caudron hydro, and on right the machine is just getting off.

-

L.Opdyke - French Aeroplanes Before the Great War /Schiffer/

This is a Chinese G-2, this one with floats. Note the star under the wing.

-

В.Шавров - История конструкций самолетов в СССР до 1938 г.

Амфибия "Кодрон" (шасси)

-

J.Davilla, A.Soltan - French Aircraft of the First World War /Flying Machines/

Caudron J seaplane at Saint Raphael on 7 May 1914.

-

L.Opdyke - French Aeroplanes Before the Great War /Schiffer/

One of 2 Type Js aboard La Foudre. This one has a hole in the top wing for the lifting hook.

-

J.Davilla, A.Soltan - French Aircraft of the First World War /Flying Machines/

Caudron G.3. On 8 May 1914, Rene Caudron flew a G.3 amphibian off the Foudre; this was the first shipboard takeoff by the French. R.D. Layman.

-

Журнал - Flight за 1913 г.

Four views of the latest Caudron seaplane, taken at Leysdown on the occasion when Mr. Ewen himself delivered the machine at Grain Island some little time back. It is the same machine that Sydney Pickles flew across the Channel accompanied by his mother, and is fitted with the new 9-cyI. 100 h.p. Gnome.

-

Журнал - Flight за 1914 г.

THE NEW 100 H.P. 9-CYL. GNOME LAND AND WATER CAUDRON FOR THE FRENCH NAVY. - Ready for launching and getting away.

-

Журнал - Flight за 1914 г.

Rene Caudron in the pilot's seat of the new Caudron land and water biplane with, as passenger, the French naval pilot who will be flying this craft.

-

Jane's All The World Aircraft 1913 /Jane's/

1912 hydro. By favour of "Aeronautics," U.S.A., UAS.

-

Jane's All The World Aircraft 1913 /Jane's/

1913 hydro.

-

Журнал - Flight за 1913 г.

Sketch of one of the main floats, showing method of springing.

-

Журнал - Flight за 1913 г.

View from underneath of main float, showing the protective keel.

-

Журнал - Flight за 1913 г.

One of the tail floats.

-

Журнал - Flight за 1913 г.

CAUDRON HYDRO-BIPLANE. - Plan, side and front elevation to scale.

В.Шавров История конструкций самолетов в СССР до 1938 г.

Амфибия "Кодрон" по схеме и конструкции аналогична сухопутному одномоторному самолету "Кодрон", но на двух поплавках, причем колеса проходили сквозь поплавки в специальных гнездах и не имели механизма подъема и выпуска. Было два экземпляра на Черном море.

Самолет|| G-3/Амфибия

Год выпуска||1914/1914

Двигатель , марка||/

мощность, л. с.||80/80

Длина самолета, м||6,8/8,1

Размах крыла, м||13,2/12,75(9,0)

Площадь крыла, м2||28,2/31

Масса пустого, кг||447/450

Масса топлива+ масла, кг||115/70

Масса полной нагрузки, кг||288/250

Полетная масса, кг||735/700

Удельная нагрузка на крыло, кг/м2||26/22,6

Удельная нагрузка на мощность, кг/лс||9,2/8,8

Весовая отдача,%||39/36

Скорость максимальная у земли, км/ч||115/105

Время набора высоты||

1000м, мин||8/15

2000м, мин||20/40

Потолок практический, м||3500/2500

Продолжительность полета, ч.||3/?

J.Davilla, A.Soltan French Aircraft of the First World War (Flying Machines)

Caudron

Several other aircraft were produced before the war. These included:

<...>

6. Type J floatplane (1913) with 100-hp Gnome.

<...>

Caudron J Seaplane

The Caudron brothers produced a twin-float seaplane in 1913 and presented it at the Expositions Internationales de l'Aeronautique that same year. The aircraft was a pusher biplane with two-bay wings, with the upper wing being considerably longer than the lower. A pair of canted struts extended from the tip of the lower wings to the edge of the upper wings. The twin floats incorporated a set of small wheels to permit the aircraft to be handled more easily on the ground. The single rudder and elevator were supported by twin booms. The scalloped rudder had an extension on which was mounted a small tail float. Power was supplied by a single 100-hp Gnome. The aircraft was intended for use as a trainer and carried a crew of two.

An example of the Type J was tested in the 1913 naval concours to select an aircraft to serve aboard French ships. A small number of the type Js were obtained by the navy.

Foreign Service

China

Small number of Type Js served with the Chinese air service. For further details see the section on the G.3.

Russia

Two Caudron seaplanes were purchased by Russia and used in the Black Sea.

United Kingdom

The Royal Naval Air Service is also believed to have acquired several Type J amphibians. The aircraft records of the RNAS indicate that the Caudrons were assigned serial Nos. 55-57. Numbers 55 and 56 were powered with 80-hp Gnome and were a signed to the cruiser HMS Hermes. No.57 had a 100-hp Gnome and was based at the Isle of Grain.

Caudron J Two-Seat Floatplane with 100-hp Gnome

Span 15.10 m; length 9.00 m; wing area 40 sq. m

Empty weight 500 kg; loaded weight 800 kg

Maximum speed: 95 km/h, climb rate 33 meter per minute.

L.Opdyke French Aeroplanes Before the Great War (Schiffer)

Jane's All The World Aircraft 1913

CAUDRON. Caudron Freres, Hue (Somme). Schools: Crotoy and Juvissy. Capacity, about 100-250 a year.

Model and date B. E. Monaco type 1913

1912-13 1912-13 1912 hydro-

biplane. biplane. hydro-biplane. biplane.

Length...feet(m.) 26? (8) 23? (7.15) 22 (6.75) 32? (10)

Span.....feet(m.) 32? (10) 35-1/3 (10.8) 33 (10.10) 46 (14)

Area..sq.ft.(m?.) 431 (40) 301 (28) 268 (25) 378 (35)

Weight, machine..

....lbs.(kgs.) 683(310) 640 (295) 772 (350) 882 400)

Motor........h.p. Anzani Gnome Gnome 70 Gnome

or Gnome

S.........m.p.h. 56 (90) 56 (90) 50 (80) 50 (80)

Number built

during 1912 ... ... ... ...

Notes.--Lateral control, warping. Wood construction. On wheels as well as floats. (Special Caudron patent.)

Журнал Flight

Flight, July 5, 1913.

THE LEISURED AVIATOR.

By SYDNEY PICKLES.

As I ruminate over the doings of the past fortnight or so, I am certainly forced to the conclusion that flying nowadays is busy work. At any rate the period in question has been busy enough for me, and certainly not without interest withal. A few Saturdays ago, on June 14th to be precise, I flew for my superior certificate. This involved a preliminary test at Hendon, after which I left for Brighton about noon.

Steering for Brooklands, I soon came over the aerodrome, and there made a glide from 2,000 feet to within 20 feet of the track, round which I flew one circuit and thereupon re-ascended for a continuation of the journey to Brighton via Leatherhead.

At one period of the flight I entered a thick bank of fog and came down to about 800 feet, where I found the air currents exceedingly strong and difficult, and, familiar as I am with my trusty Caudron, the going at this part of the journey was far from simple.

Beyond the hills, however, the fog disappeared, and I was able to get up to 2,000 ft. again. Somehow or other I must have mistaken the railway track, for I came down at Littlehampton by mistake, and so had to re-ascend and fly along the coast to Shoreham, where I met with a very hospitable reception and an excellent lunch.

After lunch I flew down to Brighton, and appeared to amuse the holiday crowd considerably by a little low flying between the piers. I did not stop at Brighton tor any length of time, however, but started almost immediately for Hendon.

The return flight was in the teeth of a head wind, but although slow by comparison with the outward journey, it was entirely uneventful, except that just as I got over the sheds I found that I had run short of lubricating oil, and therefore had to make a somewhat hurried descent.

Having filled up, and still feeling very fresh, I thought it would be a good idea to fly in the second heat of the speed handicap that was just about to start. This event I won, but in the final Brock beat me. However, I had no reason to be dissatisfied with the day's doings.

On the following Tuesday I went down to the Isle of Grain, to put a new Caudron through its tests for the Admiralty. It was the first time I had ever flown a waterplane of any description, but I found no particular difficulty about it, and was confident enough to take up one of the officers as a passenger and subsequently to give my mother her first flight, which she enjoyed immensely. She thus has, I believe, the distinction of being the first Australian lady to fly in a waterplane.

On Saturday, the 21st, I went up to Dundee to give a flight in my Bleriot, and altogether had rather a poor time. The ground was small and rough, as are so many of these temporary aerodromes over which one is invited to disport oneself in flight. The wind was strong, and there were many obstacles. In themselves these things are not necessarily serious. It is only when one's engine gives trouble that they assume alarming proportions, and as bad luck would have it my engine must needs give trouble on this particular occasion.

The point at which it chose to fail was whilst I was flying in a bee-line towards a chimney, which ordinarily I should have cleared with any amount of room to spare. Instead, the machine sank, struck the chimney, and fell - with me inside it - from a height of 30 ft. Feeling the machine falling, I let go the control and gripped the seat firmly to avoid being thrown out. The machine turned over on its side, and assumed what in a "stunt" flight would be called a vertical bank. On this occasion there was no other word for it except disaster, and I must admit I thought my chances seemed exceedingly small.

The crash came, and I picked myself up undamaged. Not only was I uninjured, but I was free from so much as a scratch. The machine, needless to say, was fairly much of a wreck.

Having seen the remains of it packed up I took the night train to London, for I had an appointment in France at Crotoy on the Monday, and must needs travel on Sunday to get there.

Accordingly, I caught the 9 o'clock boat train from town, where I had made another appointment to meet a friend who was coming over with me in order to fly back as a passenger on a new Caudron of which I was taking delivery. My friend turned up with the news that he was unable to come, which disappointed me considerably, as I disliked the idea of a solitary journey to France followed by a solo flight back again.

My friend was accompanied by a companion, to whom, in no very hopeful spirit, I transferred the invitation at precisely four minutes prior to the time the train was due to start. He had never so much as been in an aeroplane in his life, but he was a sportsman all right; and having thought about it once and-a-quarter times, he rushed off to the ticket-office, and returned just in time comfortably to take his seat in the train with me as we steamed out of the station.

When we got to Crotoy on Monday morning, the new Caudron waterplane was ready and waiting on the beach. I took it up to 2,000 ft. for a preliminary canter, and flew around a little in order 10 satisfy myself that there was nothing amiss. At five minutes past five in the afternoon I set out from Crotoy with my passenger, and flying along the French coast to Cape Grisnez, which I reached at 6.40, I steered an easterly course across the Channel. Owing to haziness of the atmosphere I did not see land again until five minutes past seven. At eight o'clock I reached the English coast, still flying against a stiff wind.

Arriving at Margate, I alighted for fresh fuel supplies, and after restarting, I flew over to the Isle of Grain, which I reached about nine o'clock in the evening.

The journey was interesting to us both, but without incident that calls for any comment. It was flown, I may mention, without a map of any description, and it was my first flight across the Channel.

On the Wednesday following I put the machine through its Admiralty tests, and incidentally made a flight with Lieut. Boyce to the Eastchurch aerodrome, where we landed, and after lunch flew back again to the water. Such is the advantage of an amphibious machine like this.

MY FIRST FLIGHT.

BY A PASSENGER WHO FLEW 175 MILES AND CROSSED THE CHANNEL IN HIS FIRST JOURNEY.

To be invited four minutes before the departure of a Continental express to be the companion of a passenger whom one has come to see off is possibly not in itself such an unusual occurrence: to accept on the spot and board the train forthwith is, however, less of a commonplace incident, being, in fact, more closely related to the conventional episodes of some thrilling novel than to the prosaic course of real life.

Such, however, was the queer turn of the wheel which Fate had in store for me on a memorable Sunday morning two weeks ago. I went down to Charing Cross with a friend in order to meet Sydney Pickles, who was due to start for Crotoy, where he was to obtain a new Caudron waterplane with which he purposed flying back to England. My friend was to have been Pickles' companion on the voyage, but at the last moment was unable to go. My own interest in the matter, up to precisely four minutes to 9 a.m., was the purely passive one of a third party at a leave-taking of two.

Coming events, they say, cast their shadows before them, but it must have been a very ethereal shadow that was cast across my path that day, for it prepared me not one whit for the suddenness of the mental disturbance into which I was thrown when I found myself suddenly being invited to be Pickles' companion in lieu of my friend.

It was preposterous, of course, quite out of the question, in fact, that one could be expected to board the boat train at a mere beckoning, as one might clamber on board a passing 'bus.

But that was not how it appealed to me; the idea that gripped my mind as in a vice was centred upon one thought only - the forthcoming flight. I had never been in an aeroplane in my life, and here was a chance such as might never come again in my whole existence. It was not a mere "once round the aerodrome" circuit that was being offered me, but a real flight with a pilot who is, as I understand it, recognised as one of the best in England.

The fact that Crotoy is not exactly a suburb of London, that I had no travelling conveniences, that I should be away for more than an hour or so, in fact every one of those things that ordinarily would array themselves as insurmountable barriers to the spontaneous accomplishment of a suddenly conceived idea of this order, diminished their perspective until they seemed as nothing at all.

There was, indeed, little time in which to argue, and no time at all in which the seeds of objection could properly take root - far less put forth shoots and bloom - An a mind that already was the stronghold of another great desire. If I thought twice, it was the same way both times. In the one remaining minute of the time available I did that which, strictly speaking, was unnecessary - I went to the booking-office, and bought a ticket.

And so, before I had well had time to come to the full realization of the consequences of my action, I was already far from London, rushing smoothly over the metals in the boat express. But for the pleasant reality of the presence of Pickles, "always merry and bright," I might have fancied myself in a dream, out of which subsequently I should awake from some grotesque parody of a journey by air.

But it was no dream on the Channel, I can assure you, and anon in France it was no dream making the final stages of the journey to Crotoy, where we arrived on the Monday morning.

During the forenoon Pickles spent some of his time making a thorough inspection of the machine and putting it through a trial flight, but after lunch and the arrival of a telegram from England, it was decided to get under way, and preparations for the journey were commenced forthwith.

At five o'clock I donned overcoats, and such wraps as I could secure, and very gingerly accommodated myself in the seat of the Caudron "'bus." Then Pickles got aboard, and proceeded to start the engine from a handle, for all the would like a motor car. Waving "good bye" to our hosts, we moved across the sands, and started the flight at exactly five minutes past the hour.

Rising gently as we flew along the coast, we gradually climbed higher and higher until the ground lay 3,000 ft. below. It was glorious. At this height the country was one vast picture map. Still following the coast line we forged steadily through the air, and 55 mins. from the time of starting had reached Boulogne.

My word, it was cold up there. I had arranged with Pickles to write a log of the flight, but I shivered so much that I could scarcely hold the pencil. Noticing this, Pickles switched off for a glide to warmer levels. But it was only for a little while, for very soon we were fighting our way full speed through the wind again, and the shivering fits came on worse than ever.

It was horrible, there was no doubt about that. All the grandeur, all the glory of flying got frozen out of my soul by this beastly cold that I could neither control nor endure. My mind, my heart, were filled with one insatiable desire for a change of situation. And then suddenly, as I thought I had about reached the limit of my power to suffer such excessive discomfort, a change came over my feelings, and in some strange way I suddenly realised that the sensation that caused me so much agony a few moments ago was not only bearable, but that I looked upon its indefinite continuance as something still within reason.

And so we flew on against the wind to Cape Gris Nez, the name of which Pickles yelled at me through the hurricane draught as a reminder that, shivers or no, I must keep my log. Thence we headed out to sea, and I left behind with the land a heartfelt wish that we had alighted, if only for a moment or two, to ease the strain on my cramped, cold shivering body and limbs.

The idea of the non-stop flight was strong in the mind of the pilot, and he kept going. Clouds loomed thick ahead, and there was no sight of the coast. A steamer came into view on the water below and remained in sight for a minute or two ere it was blotted out by the mist. Presently Pickles switched off, and glided down from 4,000 ft., where we had been flying, to 2000 ft., where he switched on again.

In the distance I noticed a little black ball in the water, which, on closer inspection, turned out to be a fishing boat. There was still no sign of land, and the old feeling of unendurable discomfort returned to me. It seemed years since we started, and the memory of the French coast line had almost faded out of the sense of reality, so long did it seem since we had left it behind.

Occasionally, I noticed the machine would rock quite a lot, and then fly steadily again for a while, until it had another spasm. Ordinarily, I should have been much interested in the performance, and possibly a little alarmed. But, under the present circumstances, I think I was willing to accept anything that fate might ordain, were it only a change.

At seven o'clock in the evening, signs of land ahead were still absent; but, looking backwards, I could dimly discern the outline of France. Three minutes later, however, a tap on the back from Pickles caused me to strain my eyes against the blast. There, in the distance, I could just make out a narrow, dark excrescence on the horizon - the first glimpse of the shores of home.

Two steamers and a lightship that presently came into view gave an air of civilisation to the otherwise deserted space, and cheered my drooping spirits immensely. I rubbed my hands together with renewed vigour, so that I might hold the pencil with better effect, but it was a sorry business.

Keeping Dover well to the left, we made for the mouth of the Thames, and by 8 o'clock we came up with the coast line and followed it round to Margate. About this time, too, Pickles was beginning to get particularly interested in his petrol gauge, and as I obstructed the view in my normal position, I found myself once or twice summarily pushed out of the light.

At Margate, Pickles switched off and alighted on the sea alongside the pier, where the machine rocked about like a row-boat on the swell. From a passing motor boat Pickles, acting for the nonce as a gymnast balancing on one of the floats, secured an anchor and length of rope, with which he proceeded to effect a mooring, whilst the party in the motor boat very kindly went to fetch some petrol from the shore.

In an incredible short space of time we were surrounded by all manner of craft, at which Pickles lustily shouted injunctions against trespassing too close. More than curiosity, however, prompted the approach of the coastguard, to whom he shouted particulars from my log. Having satisfied him that we were just and proper people to enter England, and having filled up with petrol and oil, we once more ascended into the air, after considerable preliminary bumping over the rough surface of the water.

Dusk was now falling, for it was 8.43 when we passed Heme Bay pier. Presently came Sheerness, a prettier sight from above than below, with the lights of the town and the steamers, and the flashing buoys, making a scintillating picture. Suddenly three searchlights shot their beams across the water, and passing over a little bay, Pickles switched off, and made a smooth landing in the Med way precisely at 9 o'clock.

For me it was a memorable flight that thus finished, and not while I live shall I ever forget it. It does not fall to the lot of many people to make their first trip in an aeroplane on a journey of about 175 miles, with a Channel-crossing into the bargain. It was Pickles' first Channel-ciossing, too; and although I am in no way competent to give praise for piloting, I must say I was amazed at the way in which he kept to his pre-arranged route. Much of the time at Crotoy, Pickles spent with M. Caudron, drawing maps on the sand, and the course that he selected in that manner he adhered to throughout.

W.R.M.O.

Flight, August 2, 1913.

THE CAUDRON HYDRO-BIPLANE.

THE advantages of having aeroplanes capable of starting from, and alighting on, land or water with equal facility are too obvious to need enlarging upon, and aeroplane designers at home and abroad are constantly at work endeavouring to devise a machine capable of carrying out either manoeuvre. There may be said to have been three general types of chassis construction developed for the purpose of making the machines amphibious. The first type has "disappearing" wheels - that is to say, it has wheels which can be raised clear of the water when the machine is resting on that element; while, if it is desired to alight on land, the wheels can again be lowered so as to bring them below the level of the floats. In the second type - which has, perhaps, not been developed quite as much - the reverse procedure is followed, the floats, instead of the wheels, being raised and lowered.

In the third type, to which belongs the Caudron hydro-biplane of which we publish illustrations this week, neither wheels nor floats are made to "disappear," but are so arranged relatively to one another that the lower part of the wheels projects far enough below the bottom of the floats to permit of running along the ground without the floats touching, while when the machine is afloat the wheels are partially submerged.

It is yet early days to venture an opinion as to which of the three types will survive ultimately, but the success of the Caudron hydro-biplane serves to show the good qualities of the third system.

In its general appearance this machine resembles the land machines of the same make - with which our readers are already familiar through descriptions in FLIGHT - except, of course, for such alterations as have been necessitated by the purpose for which the machines are built.

Most notable among the innovations is naturally the chassis, which has been modified in order to accommodate floats as well as wheels. A very good idea of the arrangement of this structure may be gained from an examination of the accompanying scale-drawings and sketches. The floats, which are of the single-step type, are placed widely apart, thus making the machine very stable for taxiing on the water.

A rectangular opening is provided in the centre of each float for the accommodation of the wheels. These are not, as might have been expected, sprung from the float, but attached rigidly thereto, springing being effected by means of shock absorbers interposed between the floats and the chassis skids. The method of doing this is shown in one of our sketches. Three pairs of chassis struts carry at their lower extremities two skids placed sufficiently wide apart to allow the float to move between them. A steel tube connecting the forward ends of the skids to which it is fastened runs across the top of the float. Two steel clips bolted to the sides of the float serve as bearings, allowing the float to swivel round the tube. About half-way between the two rear pairs of struts, and secured to the float by steel clips, is a similar tube, the ends of which, however, pass over the skids from which it is sprung by means of rubber shock absorbers. It will thus be seen that the forward tube serves as a pivot for the float, whilst the rear tube acts as an anchorage for the shock-absorber. This construction provides springing of the undercarriage, whether the machine is used on land or water, so that in any case the shock of alighting is greatly minimised.

The main planes are of exactly similar construction to those on the land machines, having the same flexible trailing edge which has proved so successful. The boat-shaped body in which are the seats of the pilot and observer, arranged tandem fashion, carries on overhung bearings in the nose an 80 h.p. Gnome engine, driving directly a propeller of 8 ft. diameter. Control is by means of the usual Caudron central lever, a footbar operating the twin rudders. The tail outrigger differs from that of the land machines, in that the two lower tail booms are attached to the rear spar of the lower main plane instead of being continued forward to form the skids.

Like the rudders, the tail plane, which is fluxed for elevation and descent, and warped in conjunction with the main planes, is similar to those on the land machines of the latest type. Two floats of rather unusual design support the weight of the tail when the machine is resting on the water, and two small cylindrical floats are provided on the top of the lower main plane to protect the wing tips from contact with the water. These machines have been quite successful in France, where a large number have been sold to the Government, and the British Admiralty have bought several of them from the W. H. Ewen Aviation Co., Ltd., who hold the sole rights for Great Britain and Colonies. A machine of this type is now in course of construction at the Clapham works of Messrs. Hewlett and Blondeau.

OVER THE CHANNEL WITH MY SON.

By LILLIE PICKLES (Mrs. M. Pickles, of Australia).

MONDAY, July 21st, 1913, was indeed a wonderful day for me. On the previous evening, in response to a telegram from my son, I had left London, post haste, for Boulogne, in order that I might fly back with him the next day on a waterplane. Imagine, if you can, the intensity of my thoughts, which chased one another out of mind by their rapidity of inception, while the boat was making its way on that clear, moonlight night from Folkestone to Boulogne. Anticipation mingled with reminiscence, and while one minute I was wondering what it would be like to be up in the air over the sea, the next I was recalling incidents and escapades of my boy's career. One of those memories was a day soon after a new 40 h.p. S.P.A. had arrived, when, on answering the telephone, I was told by some kind friend that my boy, who was then but twelve years old, had been seen driving that big car all by himself along the Military Road near Sydney. Cars of 40 h.p. of that period were not quite the docile vehicles they are to-day, and yet he managed it all right. Then I thought of another time when he persuaded me to accompany him in our motor boat. At first it was delightful going about in the fairly quiet water near Manby, but this was hardly satisfying to him. He wanted a little more movement and suggested that we should steer up Sydney Harbour to Mosman's Bay. I consented, as I must confess that I am a kindred soul with my son, where daring is concerned. We started, but while crossing Sydney Heads a sudden storm came up, and there we were, tossing about like a cork on the water, but my boy sat there and kept that boat's head on to every wave, as cool and as calm as though we were on a mill pond, instead of expecting a watery grave every moment. Without hesitation the assistance of a pilot boat was declined, and at last we reached the smooth waters of Mosman's Bay none the worse for our adventure, and secretly I was glad. Had I not been given a glimpse of the strength and courage of my son? So it went on from year to year, but I must not weary you with these tales of the past, or I shall not have space to tell of my wonderful flight.

On the Monday morning, after seeing some friends off by the boat, we were quickly at the hangar making ready. The machine was one of the new water-planes which had been brought along the coast from Crotoy by Rene Caudron a few days previously. After spending about half an hour in going over the machine, to make sure that everything was in order, my son and I climbed into our seats. I think, without a doubt, this was the proudest moment of my life. But there was little time for sentiment. In a moment the propeller was buzzing away merrily, and, with a wave of the hand to the kindly French folk who had come to wish us bon voyage, we started for England. Up - up we climbed into the sky like a huge bird, and with one last glance at France - which was spread out beneath us like a beautiful picture, with its long beaches and green hills studded with quaint old buildings - we turned out over the Channel, not bothering to hug the coast to Cape Grisnez as is usually done. Gradually we found our range of vision being closed in until, after flying for some fifteen minutes, we could see nothing except for a glimpse of the water immediately beneath us. By the aid of the compass, however, and with an occasional anxious look at another instrument, which my son said was an altimeter, we were able to keep going, and five minutes later the monotony was varied by the dim outline of a steamer coming towards us. This my son recognised as the outward-bound steamer for Boulogne, and a minute or so later we caught up the inward-bound boat, which had our friends on board, making its way to Folkestone. Planing down a little we spiraled round the boat, and just as the circuit was completed the engine became fractious, and slowed up by some fifty revolutions per minute. No amount of coaxing would induce it to run at its proper speed, but instead, the indicator slowly but surely crept back until it stood at only 900 r.p.m. The "white cliffs of Old Albion" were, however, well in sight by this time, and my son, without hesitation, brought the machine down to the surface of the sea, and stopped the engine. He happened to have some spare sparking plugs and a spanner in his pocket, and so he climbed out on to the front float, and while the machine bobbed about in the choppy sea, he cleaned every one of the sparking plugs in the 9-cylinder 100 h.p. Gnome engine. To his satisfaction he found that the last one to be attended to was cracked, and naturally felt that he had located the seat of the trouble. The plug replaced, Sydney climbed back into his seat, but on starting up the engine found, to his disgust, that it was in no better mood than before, and so he accepted the situation and resolved to "taxi" the remainder of the distance to Folkestone - about five miles. Our little craft was buffetted about in a most extraordinary manner, and, to crown everything, the steamer by this time had caught us up and passed on, satisfied that our acknowledgment of our friends' greetings denoted that we were happy and comfortable. To such a pass has waterplaning already arrived! We enjoyed (!) their backwash, which sent our wing tips dipping beneath the water alternately. Steadying down once more, we continued to skim over the sea like a gigantic water fowl, and although I have had many exciting times both in motor car and motor boat in Australia, none equalled the exciting, although withal, enjoyable thrills which we experienced on our hundred horse power waterplane. In but a short time we were at Folkestone, the machine answering her "helm" beautifully as we steered round into the harbour and there made her secure, in time to get ashore and see our friends off to London. After the necessary arrangements had been made for the care of the machine, and the securing of mechanics to put the engine right, I boarded the London train, a tired but very happy woman. It isn't given to many mothers to fly with their own son, and the memory of my experience will be with me for all time. Truly Sydney has fulfilled the promise of his youth.

By way of a climax, it is now my one great desire to learn to fly, and I hardly anticipate any great difficulty as I have been driving motor cars for nine years. In fact, I was the first lady to drive in Australia, and so it is perhaps a pardonable aspiration which I have to be the first Australian lady aviator.

Описание:Description: