Описание

Страна: Великобритания

Год: 1841

Вертолет

A.Andrews. The Flying Machine: Its Evolution through the Ages (Putnam)

There is no record at all of any aeronautical activity or theoretical writing by Sir George Cayley between the years 1818 and 1836. Since he was so evidently and fervently busy for the double decades before and after this gap, it seems that there must be archives still to be discovered, and that a mine of further inspiration may be exploited when such missing papers are found. The bustling energy chronicled after the resumption of the records includes a fresh call to ‘the efficient mechanics of this engineering age’ to solve ‘perhaps the most difficult triumph of mechanical skill over the elements man has had to deal with - I mean the application of aerial navigation to the purpose of voluntary conveyance’. Backing his words with action, he founded in 1839 the Polytechnic Institution in Regent Street, London. Then, in 1842, there began a regrettably unsavoury sequence in his professional life.

A young man from America sailed into Liverpool and at once wrote to Cayley, introducing himself as Robert B. Taylor, and stating that his father had been a doctor in Bolton before emigrating to America in 1819. Taylor said that he had ‘imbibed’ from his father, who had known Cayley and had often praised his devotion to flying, ‘a firm conviction of the practicability of travelling thro’ the air by mechanical means, without inflation’.

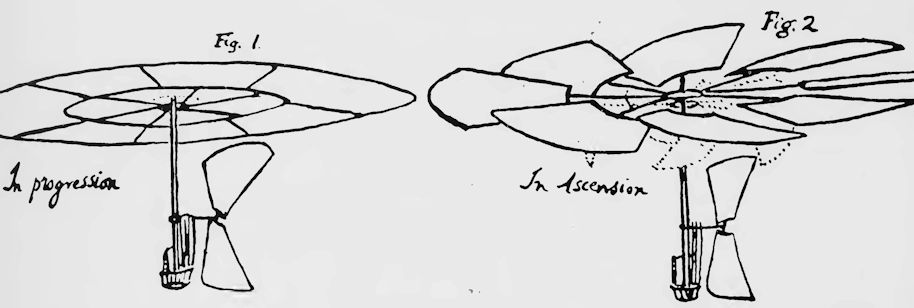

Robert Taylor then freely outlined a strikingly novel idea, and he enclosed a rough sketch of a machine incorporating this invention, the design of which he intended to patent in the United States. The proposal was for a machine that would ascend as a helicopter by the power of two contra-rotating rotors revolving about the same axis as a double hollow perpendicular' shaft. The rotor blades were to be built as vanes, which, once the necessary height had been gained, would close and lock into a flat disk - in effect, a circular mainplane. A pusher propeller would then be operated for forward flight.

Taylor showed that he had not only understood what Cayley had been teaching since 1809 - that the concise problem was ‘to make a surface support a given weight by the application of power to the resistance of air’ - but he had also gone logically beyond that. ‘The lateral movement of a large plane surface edgewise, to attain and retain altitude, is, I conceive, your original invention or idea. ... The rotary ascensive action could be dispensed with if sufficient speed were attained by the rotary propulsive action, with a general angle of the whole machine as in Fig. 1; but to start from the ground requires a perpendicular ascent at first, and I consequently screw the plane up as in Fig. 2.’ (This is a deliciously graphic Americanism which deserved a longer life, but the existence of this letter did not become public knowledge until 1961, by which time even our trainee pilots were mainly in the jet age.)

Taylor had written this letter to enquire ‘whether I have been anticipated in the principle [v/c] ideas’ and to ask if he might visit Cayley. Cayley replied speedily that he had himself anticipated Taylor, but he would be glad to meet him and ‘arrange matters so as to be fair to each’. He wrote: ‘Long ago I came to the same conclusion as you have done, as to the main features of the mechanical aerial locomotive; that is, the first rise to be made by two opposite revolving oblique vanes, which should when required become simple inclined planes, or a part of them, for progressive motion by any other propelling apparatus.’ But, said Cayley, he had laid the project aside to work for 30 years on developing an engine of sufficiently light weight.

Cayley’s assertion that he had a prior claim on this invention must be accounted as either a deliberate untruth or the self-deception of a man 68 years old. There is no evidence on record that Cayley had previously suggested any means of strictly horizontal propulsion - certainly not by the use of an airscrew - as an auxiliary to his 1796 helicopter, though he had referred to the helicopter several times in later papers.

Cayley’s subsequent behaviour is even more questionable. He first privately checked that Robert Taylor had not taken out a British patent for his idea, and then coolly announced that he had invented a similar machine himself. With his superior experience he produced a much more impressive design, but it must still be deemed a straight theft. For reasons that may or may not have any connection with this action, nothing more was ever heard of Robert Taylor. The American eagle had made a first strike at the principle of mechanical flight, and the entrenched establishment had beaten him back.

- A.Andrews. The Flying Machine: Its Evolution through the Ages (Putnam)

Фотографии

-

A.Andrews - The Flying Maschine: Its Evolution through the Ages /Putnam/

Robert Taylor’s rough sketch, sent to Sir George Cayley, of a machine to combine forward propulsion with vertical ascent. The vanes of the contra-rotating rotors lift the craft as in Fig 2. When the required height is reached the vanes merge into one plane as in Fig 1 - ‘my machine will resemble an immense flat umbrella’, said Taylor - and the airscrew pushes the craft forward. The design of the airscrew is based on the new ship’s propeller recently introduced by John Ericsson (the screw-propelled Great Britain did not make her first Atlantic crossing until 1845). The propeller mechanism is operated from the car in the ‘handle’ of the umbrella. Taylor believed that the power for his engine would be ‘derived from electro-magnetism - from which can be obtained from five to ten horse power in the space of an ordinary lady’s band box’.