Книги

Putnam

A.Jackson

Blackburn Aircraft since 1909

83

A.Jackson - Blackburn Aircraft since 1909 /Putnam/

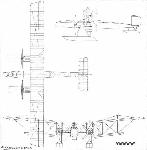

Blackburn Triplane

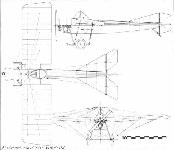

While the batch of T.B. seaplanes was going through the Blackburn works, the firm was also engaged in the construction under contract of two examples of another anti-Zeppelin fighter, the A.D. Scout (later known as the Sparrow), designed by Harris Booth of the Air Department of the Admiralty. This aircraft was a heavily-staggered, single-bay biplane of extremely unorthodox appearance, built to meet an Admiralty requirement for a fighter built from commercially obtainable materials and which could be armed with the Davis two-pounder quick-fire recoilless gun. This lay in the bottom of a short, single-seat nacelle, the top longerons of which were bolted directly to the main spars of the upper wing. With the 100 hp Gnome Monosoupape rotary driving a 9-ft pusher airscrew behind his back, the pilot had a superlative view in nearly every direction.

The aircraft's extraordinary appearance stemmed from the fact that the abnormally large mainplane gap was below instead of above the nacelle, and because the twin fins and rudders, no less than 11 ft apart, were mounted on two pairs of parallel outriggers and supported a vast tailplane of 21-ft span. A suitably bizarre undercarriage reversed the usual pattern, the three points of contact with terra firma being widely spaced skids under the fins and a pair of small wheels mounted close together centrally under the lower mainplane. In this respect it was similar to the Armstrong Whitworth F.K.12 triplane and the projected Bristol F.3A escort and anti-Zeppelin fighters, for it seems that Harris Booth believed in the 'pogo stick' type of landing gear as a means of simplifying cross-wind landings at night.

Four prototype aircraft only were ordered, 1452 and 1453 from Hewlett and Blondeau Ltd of Leagrave, Beds., and two others, 1536 and 1537, from Blackburns. They were all delivered to RNAS Chingford, but being considerably above their estimated all-up weight and difficult to handle in the air, were scrapped.

SPECIFICATION AND DATA

Manufacturers: The Blackburn Aeroplane and Motor Co Ltd, Olympia Works, Roundhay Road, Leeds, Yorks.

Power Plant: One 100 hp Gnome Monosoupape

Dimensions:

Span 33 ft 5 in Length 22 ft 9 in

Height 10 ft 3 in

Performance: No confirmed details

Production:

Four aircraft only, 1452 and 1453 by Hewlett and Blondeau Ltd; 1536 and 1537 by Blackburn, to Contract 38552 15

While the batch of T.B. seaplanes was going through the Blackburn works, the firm was also engaged in the construction under contract of two examples of another anti-Zeppelin fighter, the A.D. Scout (later known as the Sparrow), designed by Harris Booth of the Air Department of the Admiralty. This aircraft was a heavily-staggered, single-bay biplane of extremely unorthodox appearance, built to meet an Admiralty requirement for a fighter built from commercially obtainable materials and which could be armed with the Davis two-pounder quick-fire recoilless gun. This lay in the bottom of a short, single-seat nacelle, the top longerons of which were bolted directly to the main spars of the upper wing. With the 100 hp Gnome Monosoupape rotary driving a 9-ft pusher airscrew behind his back, the pilot had a superlative view in nearly every direction.

The aircraft's extraordinary appearance stemmed from the fact that the abnormally large mainplane gap was below instead of above the nacelle, and because the twin fins and rudders, no less than 11 ft apart, were mounted on two pairs of parallel outriggers and supported a vast tailplane of 21-ft span. A suitably bizarre undercarriage reversed the usual pattern, the three points of contact with terra firma being widely spaced skids under the fins and a pair of small wheels mounted close together centrally under the lower mainplane. In this respect it was similar to the Armstrong Whitworth F.K.12 triplane and the projected Bristol F.3A escort and anti-Zeppelin fighters, for it seems that Harris Booth believed in the 'pogo stick' type of landing gear as a means of simplifying cross-wind landings at night.

Four prototype aircraft only were ordered, 1452 and 1453 from Hewlett and Blondeau Ltd of Leagrave, Beds., and two others, 1536 and 1537, from Blackburns. They were all delivered to RNAS Chingford, but being considerably above their estimated all-up weight and difficult to handle in the air, were scrapped.

SPECIFICATION AND DATA

Manufacturers: The Blackburn Aeroplane and Motor Co Ltd, Olympia Works, Roundhay Road, Leeds, Yorks.

Power Plant: One 100 hp Gnome Monosoupape

Dimensions:

Span 33 ft 5 in Length 22 ft 9 in

Height 10 ft 3 in

Performance: No confirmed details

Production:

Four aircraft only, 1452 and 1453 by Hewlett and Blondeau Ltd; 1536 and 1537 by Blackburn, to Contract 38552 15

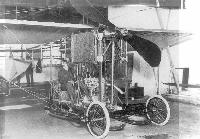

The first Blackburn-built A.D. Scout, 1536, at RNAS Chingford in 1915 with H. C. Watt in the cockpit.

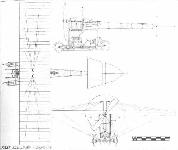

The First Blackburn Monoplane

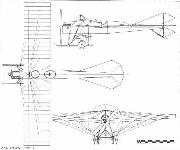

As might have been expected, Robert Blackburn's first aeroplane, being the product of a trained engineering mind, was no stick and string freak. Highly original in concept, it was a wire-and-kingpost braced high-wing monoplane built for strength rather than for economy in weight and in consequence was referred to in later years as the Heavy Type Monoplane to distinguish it from its successor. The parallel-chord square-cut mainplane was bolted across a wooden, wire-braced rectangular box structure which ran on three pneumatic-tyred, rubber-sprung wire wheels, the front being mounted on cantilevers whose trailing ends formed (as an additional safety measure) two long flat skids. A wicker chair from father's garden was pressed into service as a pilot's seat and was mounted on the floor of the box on runners as a means of C.G. adjustment. A 35 hp Green water-cooled engine (one of Gustavus Green's four-cylinder masterpieces and owing nothing to the firm of Thomas Green) was mounted on the floor ahead of the pilot and cooled by two side radiators under the wing. It drove a slow running 8 ft 6 in diameter airscrew of Blackburn's own make through a strong 2 to 1 roller chain and sprocket reduction gear. The overhead airscrew shaft ran in bearings at the front end of a long Warren girder boom which carried a fixed tailplane and, at the extreme end, a cruciform, all-moving, non-lifting, Santos Dumont type empennage mounted on a universal joint.

Not content to copy other experimenters, Blackburn dispensed with the feet for controlling direction, and fitted his patent 'triple steering column' consisting of a single car-type steering wheel which turned to operate the all-moving tail as a rudder, moved up and down when it functioned as an elevator and from side to side when warping the wings. He intended originally to fit his patented stability device in which a pendulum admitted air from an engine-driven compressor to one end or the other of a cylinder, according to which way the machine was banking, and an internal piston then operated the control surfaces so as to maintain straight and level flight. Although brilliantly anticipating the automatic pilot of the future, the device was not proceeded with and in any case would not have worked when the aeroplane was accelerating or decelerating.

The designs having been completed in Paris in 1908, the aircraft was built quite rapidly in the small workshop at Benson Street, Leeds, with the assistance of Harry Goodyear, and in April 1909, and in the face of much scepticism, Blackburn began his trials along the wide stretch of sand between Marske-by-the-Sea and Saltburn on the northeast Yorkshire coast. Painstaking taxying trials continued at intervals and the occasional absence of tyre marks proved that short hops were being made, but the 35 hp Green gave insufficient power for sustained flight and Blackburn dismissed these attempts as 'sand scratching'.

He had suspended such weighty items as engine, tanks and pilot, well below the mainplane in order to obtain a low C.G. position, but the disadvantages of such a pendulous arrangement were not immediately obvious and it was not until 24 May 1910 that he attempted a turn and paid the price. The aircraft sideslipped, dug in the port wing, skidded into a hole and threw the pilot from his seat.

One wing was a write-off, the airscrew broken and the undercarriage twisted and there was no alternative but to take the aeroplane back to Benson Street. There work began on an entirely new design and when the works moved to larger premises in Balm Road, Leeds, the fuselage of the First Monoplane went too. Illustrations in the company's 1911 catalogue show it being dismantled in stages at the end of 1910 during the overhaul of two Bleriot monoplanes for the Northern Automobile Co Ltd and the construction of Robert Blackburn's second monoplane. For no obvious reason it also received a two page descriptive write-up as the firm's new Military Type, increased in span and length and 'specially built for speed, with seating accommodation under the mainplanes and possessing thereby the chief advantage of the biplane - that of an unobstructed view'. The historic but undoubtedly defunct aircraft was then declared eminently suitable for warlike purposes!

Known as the '1909 Replica Group', enthusiastic Blackburn employees at the Brough works of Hawker Siddeley Aviation Ltd were preparing in 1966 to build a full-size replica for exhibition purposes.

SPECIFICATION AND DATA

Construction: By Robert Blackburn and Harry Goodyear at Benson Street, Leeds, Yorks.

Power Plant: One 35 hp Green

Dimensions:

(First Monoplane)

Span 24 ft 0 in Length 23 ft 0 in

Wing chord 6 ft 5 in Wing area 170 sq ft

(Military project) Span 30 ft 0 in Length 26 ft 0 in

Weights: All-up weight 800 lb

Performance: Estimated maximum speed 60 mph

Production: One aircraft only, completed September 1909, damaged beyond repair at Saltburn Sands 24 May 1910, dismantled at Balm Road, Leeds, about December 1910.

As might have been expected, Robert Blackburn's first aeroplane, being the product of a trained engineering mind, was no stick and string freak. Highly original in concept, it was a wire-and-kingpost braced high-wing monoplane built for strength rather than for economy in weight and in consequence was referred to in later years as the Heavy Type Monoplane to distinguish it from its successor. The parallel-chord square-cut mainplane was bolted across a wooden, wire-braced rectangular box structure which ran on three pneumatic-tyred, rubber-sprung wire wheels, the front being mounted on cantilevers whose trailing ends formed (as an additional safety measure) two long flat skids. A wicker chair from father's garden was pressed into service as a pilot's seat and was mounted on the floor of the box on runners as a means of C.G. adjustment. A 35 hp Green water-cooled engine (one of Gustavus Green's four-cylinder masterpieces and owing nothing to the firm of Thomas Green) was mounted on the floor ahead of the pilot and cooled by two side radiators under the wing. It drove a slow running 8 ft 6 in diameter airscrew of Blackburn's own make through a strong 2 to 1 roller chain and sprocket reduction gear. The overhead airscrew shaft ran in bearings at the front end of a long Warren girder boom which carried a fixed tailplane and, at the extreme end, a cruciform, all-moving, non-lifting, Santos Dumont type empennage mounted on a universal joint.

Not content to copy other experimenters, Blackburn dispensed with the feet for controlling direction, and fitted his patent 'triple steering column' consisting of a single car-type steering wheel which turned to operate the all-moving tail as a rudder, moved up and down when it functioned as an elevator and from side to side when warping the wings. He intended originally to fit his patented stability device in which a pendulum admitted air from an engine-driven compressor to one end or the other of a cylinder, according to which way the machine was banking, and an internal piston then operated the control surfaces so as to maintain straight and level flight. Although brilliantly anticipating the automatic pilot of the future, the device was not proceeded with and in any case would not have worked when the aeroplane was accelerating or decelerating.

The designs having been completed in Paris in 1908, the aircraft was built quite rapidly in the small workshop at Benson Street, Leeds, with the assistance of Harry Goodyear, and in April 1909, and in the face of much scepticism, Blackburn began his trials along the wide stretch of sand between Marske-by-the-Sea and Saltburn on the northeast Yorkshire coast. Painstaking taxying trials continued at intervals and the occasional absence of tyre marks proved that short hops were being made, but the 35 hp Green gave insufficient power for sustained flight and Blackburn dismissed these attempts as 'sand scratching'.

He had suspended such weighty items as engine, tanks and pilot, well below the mainplane in order to obtain a low C.G. position, but the disadvantages of such a pendulous arrangement were not immediately obvious and it was not until 24 May 1910 that he attempted a turn and paid the price. The aircraft sideslipped, dug in the port wing, skidded into a hole and threw the pilot from his seat.

One wing was a write-off, the airscrew broken and the undercarriage twisted and there was no alternative but to take the aeroplane back to Benson Street. There work began on an entirely new design and when the works moved to larger premises in Balm Road, Leeds, the fuselage of the First Monoplane went too. Illustrations in the company's 1911 catalogue show it being dismantled in stages at the end of 1910 during the overhaul of two Bleriot monoplanes for the Northern Automobile Co Ltd and the construction of Robert Blackburn's second monoplane. For no obvious reason it also received a two page descriptive write-up as the firm's new Military Type, increased in span and length and 'specially built for speed, with seating accommodation under the mainplanes and possessing thereby the chief advantage of the biplane - that of an unobstructed view'. The historic but undoubtedly defunct aircraft was then declared eminently suitable for warlike purposes!

Known as the '1909 Replica Group', enthusiastic Blackburn employees at the Brough works of Hawker Siddeley Aviation Ltd were preparing in 1966 to build a full-size replica for exhibition purposes.

SPECIFICATION AND DATA

Construction: By Robert Blackburn and Harry Goodyear at Benson Street, Leeds, Yorks.

Power Plant: One 35 hp Green

Dimensions:

(First Monoplane)

Span 24 ft 0 in Length 23 ft 0 in

Wing chord 6 ft 5 in Wing area 170 sq ft

(Military project) Span 30 ft 0 in Length 26 ft 0 in

Weights: All-up weight 800 lb

Performance: Estimated maximum speed 60 mph

Production: One aircraft only, completed September 1909, damaged beyond repair at Saltburn Sands 24 May 1910, dismantled at Balm Road, Leeds, about December 1910.

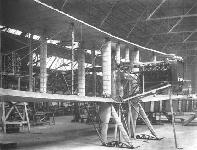

Robert Blackburn's First Monoplane in the workshop at Marske-by-the-Sea where it was housed between attempts to fly from the nearby sands, 1909-10.

The fuselage of the Second Monoplane under construction in the Benson Street works, with the partly dismantled First Monoplane behind.

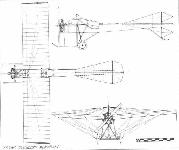

The Second Blackburn Monoplane

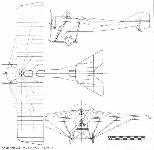

Although Robert Blackburn's second aeroplane bore a marked resemblance to M. Levavasseur's Antoinette monoplane which he had seen in France, so many detailed improvements were incorporated that the resemblance was purely superficial. It was a single-seat, fabric-covered, wooden monoplane with a square-ended, constant-chord mainplane wire-braced to a central kingpost at a considerable dihedral angle, and the fuselage was of triangular cross-section tapering rearwards from the pilot's seat.

The 'triple steering column' was used again but the little all-moving tail was abandoned in favour of the Antoinette's long dorsal fin and its diminutive triangular rudders above and below the elevator. Blackburn also fitted an untried British engine of advanced design then being developed by R. J. Isaacson, a skilled engineer employed by the Hunslet Engine Co of Leeds. The Isaacson engine was a seven-cylinder air-cooled radial of 40 hp arranged so that valves and other working parts were readily accessible for maintenance, and its many novel features (for those days) included pushrod-operated overhead valves and a 2 to 1 reduction gear within the airscrew hub. Being a stationary unit there were none of the gyroscopic problems with which the rotary engine continually plagued designers and pilots alike.

The development of such an engine inevitably took a long time, so that although Blackburn and Goodyear took the monoplane to the Blackpool Flying Meeting of 28 July - 20 August 1910, it could not participate because the engine was unfinished even though installed in the airframe. This was perhaps fortunate, for the undercarriage was so weak that the wing tips had to be supported with timber when in the hangar.

In its original form the undercarriage consisted merely of a downward extension of the wooden kingpost which terminated in a socket carrying a tubular-steel cross-member. Two ash skids, with pneumatic-tyred wire wheels in forks at the rear ends, pivoted about this steel cross member, all landing shocks being taken by a powerful coil spring at the apex of a triangle of struts under the engine. However, after Blackpool, and while he was awaiting the completion of the engine, Blackburn added a stout pair of main undercarriage struts and refitted the wheels on an overlength axle to give a measure of sideways movement under the control of coiled springs. He then took the monoplane to a new stretch of sands on the Yorkshire coast at Filey, but the undercarriage was still unsatisfactory. The front struts with their central coiled spring were removed almost immediately and replaced by four skeins of bungee rubber connecting the ends of each skid via cables to the longerons of the fuselage.

Not long after reaching Filey, the machine attracted the attention of B. C. Hucks who thereupon joined forces with Blackburn to try out the machine and, on Tuesday, 8 March 1911, taxied it for a distance of three miles along the sands before making the initial take-off. He then headed for Filey Brigg at a height of 30 ft and at an estimated speed of 50 mph, but in attempting a turn, always a hazardous manoeuvre when there is negligible difference between maximum speed and stalling speed, he sideslipped into the ground.

After repairs the Second Monoplane flew well and saw a great deal of service as an instructional aircraft at Filey and established Robert Blackburn as one of the foremost British designers of the day.

SPECIFICATION AND DATA

Construction: By R. Blackburn and H. Goodyear at Benson Street, Leeds, Yorks.

Power Plant: One 40 hp Isaacson

Dimensions: Span 30 ft 0 in Length 32 ft 0 in

Weights: All-up weight 1,000 lb

Performance: Maximum speed 60 mph

Production: One aircraft only, completed July 1910, first flown at Filey 8 March 1911.

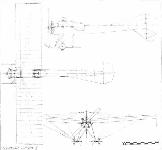

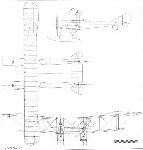

Blackburn Mercury

The Mercury, Robert Blackburn's next aeroplane, was a larger, two-seat development of his Second Monoplane powered by a new 50 hp version of the Isaacson radial. It was built with the assistance of Harry Goodyear, Mark Swann and George Watson in large premises which Blackburn acquired in Balm Road, Leeds. Whereas the earlier machine (with which the Mercury is still frequently confused) had a two-wheeled undercarriage, the Mercury had four wheels mounted in pairs on short, bungee-sprung axles astride two long ash skids attached to the fuselage by a substantial wire-braced, 12-strut, multiple A frame calculated to resist the efforts of the most inexpert pupil. Steel springs projecting sideways under the axle were intended to counteract the effects of landing with drift.

To make wire bracing unnecessary, the triangular-section lattice-work fuselage, also of English ash, was precision-built with vertical and diagonal struts butting accurately on the longerons. The forward part accommodated pilot and passenger in tandem and was planked with polished, veneered wood, but the tapering rear fuselage was fabric-covered.

Constant-chord, shoulder-mounted mainplanes were built up from closely spaced ribs supported on two I-section ash main spars and two subsidiary spars. To reduce the stresses associated with wing warping the mainplane was pivoted about the rear spar and wire-braced to a kingpost built into the fuselage in line with the front spar. The patent 'triple steering column' was used again and the tail surfaces were similar to those of the second Blackburn monoplane, with the long dorsal fin, the 10 ft bird-like tailplane, and the one-piece semi-octagonal elevator moving between two small triangular rudders.

The first Mercury (which for convenience will be referred to hereinafter as the Mercury I) was exhibited at the Olympia Aero Show during the last two weeks of March 1911 and then went to Filey to join the Blackburn Second Monoplane at the newly established Blackburn Flying School, where a new airscrew with wider blades was fitted. On 17 May B. C. Hucks flew it to Scarborough and back in 19 min, averaging 50 mph and reaching a height of 1,200 ft, the highest flight made in North England up to that time. Next day he flew the handling and height tests for his Aviator's Certificate, but differences of opinion between the Aero Club observers about the validity of doing both tests in the course of one flight led Hucks to make a second takeoff. Minutes later the airscrew sleeve overheated, seized up and broke, allowing the airscrew to fly off. Hucks received slight injuries when he sideslipped into the ground but nevertheless was granted Certificate No. 91, no mean achievement for a pilot who was entirely self-taught.

In the repaired machine Hucks (by then the Filey School instructor) made several remarkable flights, notably a cross-country to Scarborough and back on 7 July and a 40 mile moonlight trip over the same route on 10 July. Leaving Filey at 10.10 pm he circled Bridlington, reached Scarborough without difficulty, nursed a failing engine which picked up when he was about to make a forced landing in a cornfield, and landed on the beach by the light of bonfires 45 min after take-off.

Hubert Oxley who succeeded Hucks as the Filey School's instructor, flew Mercury I for the first time on 3 September 1911, and to give new pupils (one of whom was engine designer R. J. Isaacson) an opportunity of watching his control movements, the front passenger seat was turned round to face aft. The aircraft was also used for joyriding, as on 11 October when a local resident, Miss Cook, became the first lady passenger in Yorkshire.

Robert Blackburn was now calling himself 'The Blackburn Aeroplane Co' and advertised the Mercury at ?825 with 50 hp Isaacson; ?925 with 50 hp Gnome; ?730 with 35 hp Green; and ?1,275 with 100 hp Isaacson. None was in fact ever fitted with the Green or the big Isaacson, the first of a production run of eight aircraft which appeared at intervals during the next couple of years being two single-seaters (referred to in this book as Mercury IIs), built for the Daily Mail ?10,000 Circuit of Britain contest, powered by 50 hp Gnome rotaries. They had reduced span and shorter fuselages, the space normally occupied by the front seat was faired over with fabric, and fuel and oil tanks were lowered partially into the fuselage and covered by a curved metal fairing to reduce drag.

Both were entered for the contest by Stuart A. Hirst of the Yorkshire Aeroplane Club - racing No. 22 to be flown by F. Conway Jenkins and No. 27 by B. C. Hucks - and each made its maiden flight at Filey early in July 1911. During the first flight of No. 22 on 7 July, Hucks made a return flight to Scarborough, 15 miles in 15.1 minutes, and reached 3,000 ft, but on the 14th, while attempting to win Hirst's ?50 prize for a flight to Leeds in a Yorkshire-built aeroplane, he damaged it extensively in avoiding grazing cattle and carried away the undercarriage on a barbed-wire fence during a forced landing at East Heslerton Grange. By a prodigious effort it was repaired on site by Robert Blackburn's working party in time for it to be on the line at Brooklands on 22 July, but although Hucks reached Hendon successfully, he retired the next morning after a forced landing with engine trouble at Barton-in-the-Clay, near Luton. Conway Jenkins' machine turned over and was wrecked while taxying out at Brooklands, but there are conflicting reports on the cause, one blaming a strong cross-wind, another crossed warping controls.

Mark Swann and Harry Goodyear once again repaired No. 27 on site and Hucks flew it back to Hendon. It was then converted to two-seater, dismantled and sent by train from Paddington to Taunton where Hucks began a West Country tour in aid of charity, taking with him a portable hangar, Harry Goodyear as mechanic and C. E. Manton Day as manager. After two opening flights before 10,000 people at Taunton Fete on Bank Holiday Monday, 7 August, the aircraft was sent by train to Burnham-on-Sea, but, late on 17 August, because of a railway strike, Hucks flew the next 25 miles across to Minehead in 22 minutes, outflying the telegram which was to have announced his arrival. The next port of call was Locking Road aviation ground, Weston-super-Mare, where considerable publicity attended his 5.10 am take-off on 1 September for a nonstop flight to Cardiff, Whitchurch, Llandaff and back. Attired in a cork life-jacket, he reached 2,250 ft, dropped handbills over Cardiff and landed at Weston 40 minutes later, having made the first double crossing of the Bristol Channel by air. The Weston visit over, Hucks made another early start on 11 September, flew 16 miles to Cardiff in 16 1/2 minutes and landed at Whitchurch polo ground at 6.01 am. Static exhibition for two days at the Westgate Road skating rink was a prelude to daily flying from Cardiff's Ely Racecourse and, while flying at 85 mph at a height of 700 ft on 23 September, Hucks made further history by receiving wireless telegraphy signals transmitted by H. Grindell Matthews.

The tour continued with a 6.16 am take-off for Newport, Mon., on 27 September and on to Cheltenham on 1 October where the aircraft was put on show at the Drill Hall, North Street. Flying took place from Whaddon Farm, Cemetery Road, from 4 October until his departure for Gloucester on 16 October where, two days later, he caused a sensation by flying higher than the cathedral tower, although an attempt to better his personal record of 3,500 ft failed. Eventually, on 21 October, a gale lifted the travel-stained aircraft and its hangar completely clear of the ground, but quick repairs enabled the last three flights of the tour to be completed the same afternoon.

In three months, weather had prevented flying on only two of the 30 advertised flying days and an estimated 1,000 miles had been covered in 90 flights, impressive figures for those days particularly when it is remembered that all take-offs and landings were from unprepared surfaces. The wings, originally white but now black with signatures, were replaced while the aircraft was at Cheltenham. Apart from this, the only other major replacement was the result of a forced landing at Cheltenham during which Hucks ploughed up yards of cabbages with his skids until eventually a wheel came off and rolled forward, breaking the airscrew.

From 7 to 10 January 1912 the aircraft flew at Holroyd's Farm, Moortown Leeds, and was then sent to Shoreham, Sussex, by rail on loan to Lt W. Lawrence of the 7th Essex Regiment pending the delivery of a special steel-framed monoplane he had ordered from Blackburn for service in India. His immediate objective was a cross-Channel flight with society hostess Mrs Leeming as passenger. Taxying practices, begun on 25 January under the watchful eye of Hucks, led to first solos on 29 January and on 26 February to a half hour, 28-mile flight to Eastbourne where he landed down wind on the beach with engine trouble. F. B. Fowler of the Eastbourne Aviation Co gave the Gnome a complete overhaul and fitted a hand pump to overcome fuel starvation in the climb, but test flights on 30 March ended in a bad landing which put the machine on its back with sufficient damage to end Lawrence's cross-Channel aspirations. While under repair in Leeds, the opportunity was taken to modify it for school work and it emerged a month or so later as a single-seater with wing span increased to 36 ft, the wing roots cut away to improve the pilot's downward view, the undercarriage simplified, and the engine cowling extended rearward to form a scuttle over the instrument panel and afford some protection for the pilot. In this form it was historically important as the first Blackburn aircraft to exhibit a designation, each rudder bearing the inscription 'Blackburn Monoplane Type B'. One of the first pupils to fly it at the Filey School in April 1912 was M. G. Christie, DSc, for whom a special Blackburn aircraft was built in the following year.

With the possibility of military contracts looming ahead, it was considered expedient to bring the Blackburn monoplanes more closely to the notice of the War Office. The School therefore moved to Hendon in September that year under a new instructor, Harold Blackburn (no relation of Robert). There the 'brevet' machine, as it was called, was allotted racing No. 33 for the frequent weekend competitions and also bore the maker's name in large capitals on the fuselage. In this guise it was flown by Harold Blackburn on 28 September at the Hendon Naval and Military Aviation Day and on 22 February 1913 in the Aero Show Trophy Race in which he came third.

The soundness of the Mercury design, well-proven by the Hucks tour, prompted the construction of a third variant inscribed 'Mercury Passenger Type' with 60 hp Renault vee-8 air-cooled engine, now usually known as the Mercury III. This was a three-seater structurally similar to the earlier marks but with mainspars of wood-filled tubular-steel around which the cottonwood ribs were free to swivel and thus reduce twisting strains during wing warping. Other refinements included a foot accelerator which could override the hand throttle, and aluminium panels covering the engine bay. Although ready for flying at Filey on 29 October 1911, bad weather prevented Hubert Oxley from making the first flight until 9 November when the machine took off in 30 yards with one passenger and fuel for four hours. It proved very manoeuvrable and had a top speed around 70 mph.

Oxley, who began a series of passenger flights over the sands in bright moonlight at 1 am on 27 November, was the only pilot to fly this machine. On 6 December, with Robert Weiss in the passenger seat, he passed low over Filey bent on his favourite trick of diving steeply over the edge of the 300 ft cliff and then suddenly flattening out to land. This occasion was the last, for on pulling out of a particularly steep dive at a speed estimated at 150 mph, the fabric stripped from the wings which immediately broke up, leaving the wingless fuselage to plummet into the sands with fatal results for both occupants.

At first this machine had a constant-chord mainplane, but at some point during its brief six-week existence it was fitted with new wings having a root chord of 9 ft and tapering to 7 ft at the tip. Despite statements to the contrary made in the Press at the time, this was the only Blackburn Mercury fitted with a tapered wing.

A second Mercury III, with 50 hp Isaacson and faired tanks as on Mercury II, was then built for Oxley's successor Jack Brereton who attempted the Filey-Leeds flight on 29 May 1912. This machine further differed from the Isaacson-powered Mercury I in having the top rudder raised above the fin, removable inspection panels behind the engine, and no wing tip skids. After a 6 am take-off, Brereton forced landed 22 miles away at Malton with engine trouble, and the flight ended in a second forced landing at Welham Park later in the day. The machine went back to Filey by rail and after this episode R. J. Isaacson modified the engine and fitted ball bearings to the connecting rods and crankshaft. It was flying again on 9 June and went to Hendon with the Type B in the following September.

The third Mercury III, built for naval flying pioneer Lt Spenser Grey, RN, had polished aluminium side panels as far aft as the cockpit and for this reason has been continually misrepresented as one of the all-steel monoplanes which Blackburn built in 1912. Redesign of the front fuselage, which began when the tanks on the Mercury IIs and the second Mercury III were lowered and covered, reached finality in Spenser Grey's machine. This had a curved decking over the tanks which continued the line of the circular cowling over the 50 hp Gnome back as far as the cockpit where it formed a 'scuttle-dash' to deflect some of the slipstream from the pilot. This modification was embodied in the Hucks tour machine when it was rebuilt as Type B in 1912. Grey's Mercury III was delivered by rail to Brooklands where Hucks made the first engine runs on 16 December 1911, and the owner flew it for the first time on 25 December. A few days later he made a cross-country flight to Lodmoor, near Weymouth, where he had had a hangar built and on 7 January 1912 crossed Weymouth Bay to Portland and circled over the Home Fleet. Unfortunately, after exhibition flights on 10 January, he returned to find his landing ground full of sightseers and the machine was damaged in the ensuing avoiding action. After repairs at Leeds the redoubtable Harry Goodyear took the machine to Eastchurch by train and re-erected it. Spenser Grey then made the first of many flights there on 21 February. The aircraft was eventually repurchased by Blackburns, fitted with the simplified Type B undercarriage, and put to work as a school machine at Hendon where it took part in the Naval and Military Aviation Day on 28 September 1912.

The fourth Mercury III, identified by a combination of cut-away wing roots and six-strut undercarriage, was built for the Blackburn School and flew at Filey in March 1912. Yet another is said to have had a 50 hp Anzani radial. For the summer season that year, a special single-seat machine with partially cowled 50 hp Gnome, similar to the Type B and with 'Blackburn' in bold lettering under each wing, was built to enable Jack Brereton to give demonstrations similar to those of B. C. Hucks the year before. Although it had the cut-away wing roots of Mercury III No. 4, its undercarriage differed from those of all other Mercury monoplanes. Basically of the simplified type fitted to the Type B, it had a tubular-steel spreader bar between the front struts and laminated skids with turned-down rear ends. It was first flown at Filey on 7 June 1912, and initial engagements were at Bridlington on 15 July and the Lincolnshire Agricultural Show, Skegness, two days later.

Despite the oft repeated assertion that nine Mercury Ills were built, careful research has failed to identify more than six, so that in the absence of further information it can only be assumed that the total of nine included the Mercury I and the two Mercury IIs. The company's Flying School activities seem to have been maintained throughout by four aircraft. At Filey they appear to have been Blackburn's second monoplane, the Mercury I and Isaacson- and Gnome-powered Mercury IIIs, but at Hendon the veteran second monoplane and the old Mercury I were replaced by the Type B and the modified ex-Spenser Grey two-seater. They remained in service until the School closed in the spring of 1913 and were flown by a select band of pupil pilots, only three of whom actually gained Royal Aero Club Aviators' Certificates on the Blackburn types on which they had learned, viz:

No. 91 B.C.Hucks Filey 30 May 1911

No. 409 H.A.Buss Hendon 4 February 1913

No. 410 M.F.Glew Hendon 4 February 1913

SPECIFICATION AND DATA

Constructors: The Blackburn Aeroplane Co (the Aeroplane Dept of Robert Blackburn and Co, Engineers), Balm Road, Leeds, Yorks.

Power Plants:

(Mercury I) One 50 hp Isaacson

(Mercury II) One 50 hp Gnome

(Mercury III)

One 60 hp Renault

One 50 hp Isaacson

One 50 hp Gnome

One 50 hp Anzani

Dimensions, Weights and Performances:

Mercury I Mercury II Mercury III

Span 38 ft 4 in 32 ft 0 in* 32 ft 0 in

Length 33 ft 0 in 31 ft 0 in 31 ft 0 in

Height 6 ft 9 in 8 ft 6 in 8 ft 6 in

Wing area 288 sq ft 200 sq ft* 195 sq ft

All-up weight 1,000 lb** 700 lb 800 lb

Maximum speed 60 mph 70 mph 75 mph***

* Second aircraft later rebuilt with 36 ft span, 220 sq ft mainplane

** With Isaacson engine

*** With Renault engine

Production:

(a) Mercury I

One aircraft only, 50 hp Isaacson, shown at Olympia March 1911 and used by the Blackburn Flying School, Filey, until 1912.

(b) Mercury II

Two aircraft only, both with 50 hp Gnome engines:

1. Racing No. 22, first flown at Filey in July 1911, wrecked at Brooklands 22 July 1911.

2. Racing No. 27,first flown at Filey 7 July 1911, converted to two-seater August 1911, crashed at Eastbourne 23 March 1912, rebuilt as a single-seat school machine for the Filey School April 1912, to the Hendon School September 1912 as racing No. 33, withdrawn from use when the school closed June 1913.

(c) Mercury III

Six aircraft as follows (in approximate production order):

1. 60 hp Renault First flown 9 November 1911, crashed at Filey 6 December 1911.

2. 50 hp Isaacson First flown May 1912, identified by raised top rudder, used by the Blackburn Flying School, Hendon, until June 1913.

3. 50 hp Gnome First flown 25 December 1911, built for Lt Spenser Grey, RN, damaged at Weymouth 10 January 1912, first flown at Eastchurch after repair 21 February 1912, to the Blackburn Flying School, Hendon, by September 1912.

4. 50 hp Gnome School machine, cut-away wing roots, first flown at Filey March 1912.

5. 50 hp Anzani No details.

6. 50 hp Gnome Exhibition machine first flown 7 June 1912.

Although Robert Blackburn's second aeroplane bore a marked resemblance to M. Levavasseur's Antoinette monoplane which he had seen in France, so many detailed improvements were incorporated that the resemblance was purely superficial. It was a single-seat, fabric-covered, wooden monoplane with a square-ended, constant-chord mainplane wire-braced to a central kingpost at a considerable dihedral angle, and the fuselage was of triangular cross-section tapering rearwards from the pilot's seat.

The 'triple steering column' was used again but the little all-moving tail was abandoned in favour of the Antoinette's long dorsal fin and its diminutive triangular rudders above and below the elevator. Blackburn also fitted an untried British engine of advanced design then being developed by R. J. Isaacson, a skilled engineer employed by the Hunslet Engine Co of Leeds. The Isaacson engine was a seven-cylinder air-cooled radial of 40 hp arranged so that valves and other working parts were readily accessible for maintenance, and its many novel features (for those days) included pushrod-operated overhead valves and a 2 to 1 reduction gear within the airscrew hub. Being a stationary unit there were none of the gyroscopic problems with which the rotary engine continually plagued designers and pilots alike.

The development of such an engine inevitably took a long time, so that although Blackburn and Goodyear took the monoplane to the Blackpool Flying Meeting of 28 July - 20 August 1910, it could not participate because the engine was unfinished even though installed in the airframe. This was perhaps fortunate, for the undercarriage was so weak that the wing tips had to be supported with timber when in the hangar.

In its original form the undercarriage consisted merely of a downward extension of the wooden kingpost which terminated in a socket carrying a tubular-steel cross-member. Two ash skids, with pneumatic-tyred wire wheels in forks at the rear ends, pivoted about this steel cross member, all landing shocks being taken by a powerful coil spring at the apex of a triangle of struts under the engine. However, after Blackpool, and while he was awaiting the completion of the engine, Blackburn added a stout pair of main undercarriage struts and refitted the wheels on an overlength axle to give a measure of sideways movement under the control of coiled springs. He then took the monoplane to a new stretch of sands on the Yorkshire coast at Filey, but the undercarriage was still unsatisfactory. The front struts with their central coiled spring were removed almost immediately and replaced by four skeins of bungee rubber connecting the ends of each skid via cables to the longerons of the fuselage.

Not long after reaching Filey, the machine attracted the attention of B. C. Hucks who thereupon joined forces with Blackburn to try out the machine and, on Tuesday, 8 March 1911, taxied it for a distance of three miles along the sands before making the initial take-off. He then headed for Filey Brigg at a height of 30 ft and at an estimated speed of 50 mph, but in attempting a turn, always a hazardous manoeuvre when there is negligible difference between maximum speed and stalling speed, he sideslipped into the ground.

After repairs the Second Monoplane flew well and saw a great deal of service as an instructional aircraft at Filey and established Robert Blackburn as one of the foremost British designers of the day.

SPECIFICATION AND DATA

Construction: By R. Blackburn and H. Goodyear at Benson Street, Leeds, Yorks.

Power Plant: One 40 hp Isaacson

Dimensions: Span 30 ft 0 in Length 32 ft 0 in

Weights: All-up weight 1,000 lb

Performance: Maximum speed 60 mph

Production: One aircraft only, completed July 1910, first flown at Filey 8 March 1911.

Blackburn Mercury

The Mercury, Robert Blackburn's next aeroplane, was a larger, two-seat development of his Second Monoplane powered by a new 50 hp version of the Isaacson radial. It was built with the assistance of Harry Goodyear, Mark Swann and George Watson in large premises which Blackburn acquired in Balm Road, Leeds. Whereas the earlier machine (with which the Mercury is still frequently confused) had a two-wheeled undercarriage, the Mercury had four wheels mounted in pairs on short, bungee-sprung axles astride two long ash skids attached to the fuselage by a substantial wire-braced, 12-strut, multiple A frame calculated to resist the efforts of the most inexpert pupil. Steel springs projecting sideways under the axle were intended to counteract the effects of landing with drift.

To make wire bracing unnecessary, the triangular-section lattice-work fuselage, also of English ash, was precision-built with vertical and diagonal struts butting accurately on the longerons. The forward part accommodated pilot and passenger in tandem and was planked with polished, veneered wood, but the tapering rear fuselage was fabric-covered.

Constant-chord, shoulder-mounted mainplanes were built up from closely spaced ribs supported on two I-section ash main spars and two subsidiary spars. To reduce the stresses associated with wing warping the mainplane was pivoted about the rear spar and wire-braced to a kingpost built into the fuselage in line with the front spar. The patent 'triple steering column' was used again and the tail surfaces were similar to those of the second Blackburn monoplane, with the long dorsal fin, the 10 ft bird-like tailplane, and the one-piece semi-octagonal elevator moving between two small triangular rudders.

The first Mercury (which for convenience will be referred to hereinafter as the Mercury I) was exhibited at the Olympia Aero Show during the last two weeks of March 1911 and then went to Filey to join the Blackburn Second Monoplane at the newly established Blackburn Flying School, where a new airscrew with wider blades was fitted. On 17 May B. C. Hucks flew it to Scarborough and back in 19 min, averaging 50 mph and reaching a height of 1,200 ft, the highest flight made in North England up to that time. Next day he flew the handling and height tests for his Aviator's Certificate, but differences of opinion between the Aero Club observers about the validity of doing both tests in the course of one flight led Hucks to make a second takeoff. Minutes later the airscrew sleeve overheated, seized up and broke, allowing the airscrew to fly off. Hucks received slight injuries when he sideslipped into the ground but nevertheless was granted Certificate No. 91, no mean achievement for a pilot who was entirely self-taught.

In the repaired machine Hucks (by then the Filey School instructor) made several remarkable flights, notably a cross-country to Scarborough and back on 7 July and a 40 mile moonlight trip over the same route on 10 July. Leaving Filey at 10.10 pm he circled Bridlington, reached Scarborough without difficulty, nursed a failing engine which picked up when he was about to make a forced landing in a cornfield, and landed on the beach by the light of bonfires 45 min after take-off.

Hubert Oxley who succeeded Hucks as the Filey School's instructor, flew Mercury I for the first time on 3 September 1911, and to give new pupils (one of whom was engine designer R. J. Isaacson) an opportunity of watching his control movements, the front passenger seat was turned round to face aft. The aircraft was also used for joyriding, as on 11 October when a local resident, Miss Cook, became the first lady passenger in Yorkshire.

Robert Blackburn was now calling himself 'The Blackburn Aeroplane Co' and advertised the Mercury at ?825 with 50 hp Isaacson; ?925 with 50 hp Gnome; ?730 with 35 hp Green; and ?1,275 with 100 hp Isaacson. None was in fact ever fitted with the Green or the big Isaacson, the first of a production run of eight aircraft which appeared at intervals during the next couple of years being two single-seaters (referred to in this book as Mercury IIs), built for the Daily Mail ?10,000 Circuit of Britain contest, powered by 50 hp Gnome rotaries. They had reduced span and shorter fuselages, the space normally occupied by the front seat was faired over with fabric, and fuel and oil tanks were lowered partially into the fuselage and covered by a curved metal fairing to reduce drag.

Both were entered for the contest by Stuart A. Hirst of the Yorkshire Aeroplane Club - racing No. 22 to be flown by F. Conway Jenkins and No. 27 by B. C. Hucks - and each made its maiden flight at Filey early in July 1911. During the first flight of No. 22 on 7 July, Hucks made a return flight to Scarborough, 15 miles in 15.1 minutes, and reached 3,000 ft, but on the 14th, while attempting to win Hirst's ?50 prize for a flight to Leeds in a Yorkshire-built aeroplane, he damaged it extensively in avoiding grazing cattle and carried away the undercarriage on a barbed-wire fence during a forced landing at East Heslerton Grange. By a prodigious effort it was repaired on site by Robert Blackburn's working party in time for it to be on the line at Brooklands on 22 July, but although Hucks reached Hendon successfully, he retired the next morning after a forced landing with engine trouble at Barton-in-the-Clay, near Luton. Conway Jenkins' machine turned over and was wrecked while taxying out at Brooklands, but there are conflicting reports on the cause, one blaming a strong cross-wind, another crossed warping controls.

Mark Swann and Harry Goodyear once again repaired No. 27 on site and Hucks flew it back to Hendon. It was then converted to two-seater, dismantled and sent by train from Paddington to Taunton where Hucks began a West Country tour in aid of charity, taking with him a portable hangar, Harry Goodyear as mechanic and C. E. Manton Day as manager. After two opening flights before 10,000 people at Taunton Fete on Bank Holiday Monday, 7 August, the aircraft was sent by train to Burnham-on-Sea, but, late on 17 August, because of a railway strike, Hucks flew the next 25 miles across to Minehead in 22 minutes, outflying the telegram which was to have announced his arrival. The next port of call was Locking Road aviation ground, Weston-super-Mare, where considerable publicity attended his 5.10 am take-off on 1 September for a nonstop flight to Cardiff, Whitchurch, Llandaff and back. Attired in a cork life-jacket, he reached 2,250 ft, dropped handbills over Cardiff and landed at Weston 40 minutes later, having made the first double crossing of the Bristol Channel by air. The Weston visit over, Hucks made another early start on 11 September, flew 16 miles to Cardiff in 16 1/2 minutes and landed at Whitchurch polo ground at 6.01 am. Static exhibition for two days at the Westgate Road skating rink was a prelude to daily flying from Cardiff's Ely Racecourse and, while flying at 85 mph at a height of 700 ft on 23 September, Hucks made further history by receiving wireless telegraphy signals transmitted by H. Grindell Matthews.

The tour continued with a 6.16 am take-off for Newport, Mon., on 27 September and on to Cheltenham on 1 October where the aircraft was put on show at the Drill Hall, North Street. Flying took place from Whaddon Farm, Cemetery Road, from 4 October until his departure for Gloucester on 16 October where, two days later, he caused a sensation by flying higher than the cathedral tower, although an attempt to better his personal record of 3,500 ft failed. Eventually, on 21 October, a gale lifted the travel-stained aircraft and its hangar completely clear of the ground, but quick repairs enabled the last three flights of the tour to be completed the same afternoon.

In three months, weather had prevented flying on only two of the 30 advertised flying days and an estimated 1,000 miles had been covered in 90 flights, impressive figures for those days particularly when it is remembered that all take-offs and landings were from unprepared surfaces. The wings, originally white but now black with signatures, were replaced while the aircraft was at Cheltenham. Apart from this, the only other major replacement was the result of a forced landing at Cheltenham during which Hucks ploughed up yards of cabbages with his skids until eventually a wheel came off and rolled forward, breaking the airscrew.

From 7 to 10 January 1912 the aircraft flew at Holroyd's Farm, Moortown Leeds, and was then sent to Shoreham, Sussex, by rail on loan to Lt W. Lawrence of the 7th Essex Regiment pending the delivery of a special steel-framed monoplane he had ordered from Blackburn for service in India. His immediate objective was a cross-Channel flight with society hostess Mrs Leeming as passenger. Taxying practices, begun on 25 January under the watchful eye of Hucks, led to first solos on 29 January and on 26 February to a half hour, 28-mile flight to Eastbourne where he landed down wind on the beach with engine trouble. F. B. Fowler of the Eastbourne Aviation Co gave the Gnome a complete overhaul and fitted a hand pump to overcome fuel starvation in the climb, but test flights on 30 March ended in a bad landing which put the machine on its back with sufficient damage to end Lawrence's cross-Channel aspirations. While under repair in Leeds, the opportunity was taken to modify it for school work and it emerged a month or so later as a single-seater with wing span increased to 36 ft, the wing roots cut away to improve the pilot's downward view, the undercarriage simplified, and the engine cowling extended rearward to form a scuttle over the instrument panel and afford some protection for the pilot. In this form it was historically important as the first Blackburn aircraft to exhibit a designation, each rudder bearing the inscription 'Blackburn Monoplane Type B'. One of the first pupils to fly it at the Filey School in April 1912 was M. G. Christie, DSc, for whom a special Blackburn aircraft was built in the following year.

With the possibility of military contracts looming ahead, it was considered expedient to bring the Blackburn monoplanes more closely to the notice of the War Office. The School therefore moved to Hendon in September that year under a new instructor, Harold Blackburn (no relation of Robert). There the 'brevet' machine, as it was called, was allotted racing No. 33 for the frequent weekend competitions and also bore the maker's name in large capitals on the fuselage. In this guise it was flown by Harold Blackburn on 28 September at the Hendon Naval and Military Aviation Day and on 22 February 1913 in the Aero Show Trophy Race in which he came third.

The soundness of the Mercury design, well-proven by the Hucks tour, prompted the construction of a third variant inscribed 'Mercury Passenger Type' with 60 hp Renault vee-8 air-cooled engine, now usually known as the Mercury III. This was a three-seater structurally similar to the earlier marks but with mainspars of wood-filled tubular-steel around which the cottonwood ribs were free to swivel and thus reduce twisting strains during wing warping. Other refinements included a foot accelerator which could override the hand throttle, and aluminium panels covering the engine bay. Although ready for flying at Filey on 29 October 1911, bad weather prevented Hubert Oxley from making the first flight until 9 November when the machine took off in 30 yards with one passenger and fuel for four hours. It proved very manoeuvrable and had a top speed around 70 mph.

Oxley, who began a series of passenger flights over the sands in bright moonlight at 1 am on 27 November, was the only pilot to fly this machine. On 6 December, with Robert Weiss in the passenger seat, he passed low over Filey bent on his favourite trick of diving steeply over the edge of the 300 ft cliff and then suddenly flattening out to land. This occasion was the last, for on pulling out of a particularly steep dive at a speed estimated at 150 mph, the fabric stripped from the wings which immediately broke up, leaving the wingless fuselage to plummet into the sands with fatal results for both occupants.

At first this machine had a constant-chord mainplane, but at some point during its brief six-week existence it was fitted with new wings having a root chord of 9 ft and tapering to 7 ft at the tip. Despite statements to the contrary made in the Press at the time, this was the only Blackburn Mercury fitted with a tapered wing.

A second Mercury III, with 50 hp Isaacson and faired tanks as on Mercury II, was then built for Oxley's successor Jack Brereton who attempted the Filey-Leeds flight on 29 May 1912. This machine further differed from the Isaacson-powered Mercury I in having the top rudder raised above the fin, removable inspection panels behind the engine, and no wing tip skids. After a 6 am take-off, Brereton forced landed 22 miles away at Malton with engine trouble, and the flight ended in a second forced landing at Welham Park later in the day. The machine went back to Filey by rail and after this episode R. J. Isaacson modified the engine and fitted ball bearings to the connecting rods and crankshaft. It was flying again on 9 June and went to Hendon with the Type B in the following September.

The third Mercury III, built for naval flying pioneer Lt Spenser Grey, RN, had polished aluminium side panels as far aft as the cockpit and for this reason has been continually misrepresented as one of the all-steel monoplanes which Blackburn built in 1912. Redesign of the front fuselage, which began when the tanks on the Mercury IIs and the second Mercury III were lowered and covered, reached finality in Spenser Grey's machine. This had a curved decking over the tanks which continued the line of the circular cowling over the 50 hp Gnome back as far as the cockpit where it formed a 'scuttle-dash' to deflect some of the slipstream from the pilot. This modification was embodied in the Hucks tour machine when it was rebuilt as Type B in 1912. Grey's Mercury III was delivered by rail to Brooklands where Hucks made the first engine runs on 16 December 1911, and the owner flew it for the first time on 25 December. A few days later he made a cross-country flight to Lodmoor, near Weymouth, where he had had a hangar built and on 7 January 1912 crossed Weymouth Bay to Portland and circled over the Home Fleet. Unfortunately, after exhibition flights on 10 January, he returned to find his landing ground full of sightseers and the machine was damaged in the ensuing avoiding action. After repairs at Leeds the redoubtable Harry Goodyear took the machine to Eastchurch by train and re-erected it. Spenser Grey then made the first of many flights there on 21 February. The aircraft was eventually repurchased by Blackburns, fitted with the simplified Type B undercarriage, and put to work as a school machine at Hendon where it took part in the Naval and Military Aviation Day on 28 September 1912.

The fourth Mercury III, identified by a combination of cut-away wing roots and six-strut undercarriage, was built for the Blackburn School and flew at Filey in March 1912. Yet another is said to have had a 50 hp Anzani radial. For the summer season that year, a special single-seat machine with partially cowled 50 hp Gnome, similar to the Type B and with 'Blackburn' in bold lettering under each wing, was built to enable Jack Brereton to give demonstrations similar to those of B. C. Hucks the year before. Although it had the cut-away wing roots of Mercury III No. 4, its undercarriage differed from those of all other Mercury monoplanes. Basically of the simplified type fitted to the Type B, it had a tubular-steel spreader bar between the front struts and laminated skids with turned-down rear ends. It was first flown at Filey on 7 June 1912, and initial engagements were at Bridlington on 15 July and the Lincolnshire Agricultural Show, Skegness, two days later.

Despite the oft repeated assertion that nine Mercury Ills were built, careful research has failed to identify more than six, so that in the absence of further information it can only be assumed that the total of nine included the Mercury I and the two Mercury IIs. The company's Flying School activities seem to have been maintained throughout by four aircraft. At Filey they appear to have been Blackburn's second monoplane, the Mercury I and Isaacson- and Gnome-powered Mercury IIIs, but at Hendon the veteran second monoplane and the old Mercury I were replaced by the Type B and the modified ex-Spenser Grey two-seater. They remained in service until the School closed in the spring of 1913 and were flown by a select band of pupil pilots, only three of whom actually gained Royal Aero Club Aviators' Certificates on the Blackburn types on which they had learned, viz:

No. 91 B.C.Hucks Filey 30 May 1911

No. 409 H.A.Buss Hendon 4 February 1913

No. 410 M.F.Glew Hendon 4 February 1913

SPECIFICATION AND DATA

Constructors: The Blackburn Aeroplane Co (the Aeroplane Dept of Robert Blackburn and Co, Engineers), Balm Road, Leeds, Yorks.

Power Plants:

(Mercury I) One 50 hp Isaacson

(Mercury II) One 50 hp Gnome

(Mercury III)

One 60 hp Renault

One 50 hp Isaacson

One 50 hp Gnome

One 50 hp Anzani

Dimensions, Weights and Performances:

Mercury I Mercury II Mercury III

Span 38 ft 4 in 32 ft 0 in* 32 ft 0 in

Length 33 ft 0 in 31 ft 0 in 31 ft 0 in

Height 6 ft 9 in 8 ft 6 in 8 ft 6 in

Wing area 288 sq ft 200 sq ft* 195 sq ft

All-up weight 1,000 lb** 700 lb 800 lb

Maximum speed 60 mph 70 mph 75 mph***

* Second aircraft later rebuilt with 36 ft span, 220 sq ft mainplane

** With Isaacson engine

*** With Renault engine

Production:

(a) Mercury I

One aircraft only, 50 hp Isaacson, shown at Olympia March 1911 and used by the Blackburn Flying School, Filey, until 1912.

(b) Mercury II

Two aircraft only, both with 50 hp Gnome engines:

1. Racing No. 22, first flown at Filey in July 1911, wrecked at Brooklands 22 July 1911.

2. Racing No. 27,first flown at Filey 7 July 1911, converted to two-seater August 1911, crashed at Eastbourne 23 March 1912, rebuilt as a single-seat school machine for the Filey School April 1912, to the Hendon School September 1912 as racing No. 33, withdrawn from use when the school closed June 1913.

(c) Mercury III

Six aircraft as follows (in approximate production order):

1. 60 hp Renault First flown 9 November 1911, crashed at Filey 6 December 1911.

2. 50 hp Isaacson First flown May 1912, identified by raised top rudder, used by the Blackburn Flying School, Hendon, until June 1913.

3. 50 hp Gnome First flown 25 December 1911, built for Lt Spenser Grey, RN, damaged at Weymouth 10 January 1912, first flown at Eastchurch after repair 21 February 1912, to the Blackburn Flying School, Hendon, by September 1912.

4. 50 hp Gnome School machine, cut-away wing roots, first flown at Filey March 1912.

5. 50 hp Anzani No details.

6. 50 hp Gnome Exhibition machine first flown 7 June 1912.

The completed Second Monoplane with fuel and oil tanks in position, narrow-bladed airscrew, and the first undercarriage modification.

Robert Blackburn (standing right) and B. C. Hucks with ihe Mercury I in the cliff-top hangar, Filey 1911.

B.C.Hucks fuelling the Mercury I before the Filey-Scarborough flight of 17 May 1911. The high-mounted tanks which identify this machine are clearly illustrated.

Lawrence's all-steel monoplane (right) under construction in the Balm Road works in April 1912, next to his damaged Mercury II which was awaiting conversion to Type B.

Laurence Spink at the controls of the Type B, Hendon 1913. Details of the Blackburn patent triple steering column are clearly visible.

Robert Blackburn beside the Type B, racing number 33, before the start of the Aero Show Trophy Race at Hendon on 22 February 1913.

The Mercury Passenger Type (the first Mercury III) with 80 hp Renault and the original parallel-chord mainplane

Hubert Oxley and passenger in the ill-fated Mercury Passenger Type outside the Filey hangar after the tapered mainplane was fitted.

Jack Brereton climbing into the second Mercury III (50 hp Isaacson) at Filey in May 1912. The raised top rudder distinguished it from the Isaacson-powered Mercury I.

The fuselage of Lt Spenser Grey's two-seat Mercury III (50 hp Gnome) outside the Balm Road works ready for despatch to Brooklands, December 1911. These views show clearly the third and final stage in Mercury fuselage evolution.

Mark Swann (no hat) and Jack Brereton (right) with the last of the Mercury monoplanes on the promenade at Bridlington on 15 July 1912. The machine is identified by the undercarriage modification.

Jack Brereton flying the fourth Mercury III (50 hp Gnome, cut-away wing roots and six-strut undercarriage) at Filey in May 1912.

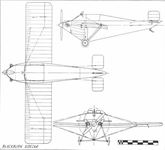

Blackburn Single-Seat Monoplane

On 19 October 1912 Mr Cyril E. Foggin qualified for Aviator's Certificate No. 349 on a Bleriot monoplane of the Eastbourne Aviation Co and soon afterwards placed an order with Robert Blackburn for a private aeroplane. This was a single-seat monoplane built of selected English ash, fabric-covered and powered by a 50 hp Gnome rotary. It was smaller, more compact and streamlined than the Mercury but retained the triangular-section fuselage and wire-braced, square-cut warping wing which was rectangular in planform with I-section spars machined out of straight-grained ash over which were slipped silver spruce ribs with cottonwood flanges. The fabric was held in place by a beading of split cane along each rib. The mainplane was braced to the undercarriage by three flying wires and also to the top of a central pylon which also carried the pulleys for the upper warping cable.

External features which gave the new single-seater a modern appearance were the curved top-decking, the aluminium-plated front fuselage, the one-piece rudder with divided elevator, and the simplified, two-wheel, bungee-sprung undercarriage. For the first time in a Blackburn aeroplane the rudder was operated by a foot bar, and a small, universally mounted, wing-warping wheel was situated on top of the control column. From the pilot's point of view a most disconcerting feature was a crossbar, joining the root ends of the rear wing-spar, which clamped across his lap after he had taken his seat.

The machine was completed with commendable speed and first flew unpainted, in the hands of Harold Blackburn, at the end of 1912. Its rate of climb was a marked improvement on that of its predecessors, and the machine appeared for the first time in public at Lofthouse Park, Leeds, on Good Friday, 21 March 1913, when Blackburn began ten days of demonstration flying which included circuits of Wakefield. The owner, Cyril Foggin, flew it for the first time on Easter Monday, 24 March, and was airborne for 20 min. Exhaust fumes and hot oil, when thrown back into the cockpit do not make for safe and enjoyable flying, and after a few flights the rather abbreviated engine cowling was extended down to the line of the top longerons.

Further demonstration flying with Harold Blackburn at the controls then took place at Lofthouse Park (later known as the Yorkshire Aerodrome) at intervals until the end of May. Cross-country flights were also made to Stamford on 2 and 3 April, when he dropped 2,500 leaflets from 1,200 ft. With the aid of map and compass - one of the earliest attempts at accurate navigation - he flew to Harrogate on 29 April and landed on the Stray in front of the Queen's Hotel, having covered the 18 miles in as many minutes and reached a height of 4,000 ft en route. Finally, on 23, 24 and 25 July, he made daily newspaper flights between Leeds and York to deliver bundles of the Yorkshire Post.

The original hooked undercarriage skids were later replaced by the more usual and less lethal hockey stick variety, and a new mainplane with rounded tips similar to that used on its two-seat derivative, the Type I, was also fitted. Foggin then sold the machine to Montague F. Glew, whom he had met at the Blackburn School, Hendon, earlier in the year. Glew, who on 4 February 1913 had qualified on a Blackburn Mercury for Aviator's Certificate No. 410, flew and eventually crashed the ex-Foggin machine on his father's farm at Wittering, Lines., adjacent to the site of the present RAF aerodrome.

Reconstruction began by cutting 18 in off the fuselage longerons behind the engine bearer plate and this has been interpreted as a C.G. adjustment consistent with an attempt to install a heavier and more powerful engine, but such a scheme was never mentioned by M. F. Glew.

When war came later in 1914, the components were stored in a farm building, where they were discovered by the late R. O. Shuttleworth almost a quarter of a century later, in 1938. Several of the major airframe assemblies were lying under hay but all were collected together and conveyed to the Shuttleworth headquarters at Old Warden Aerodrome, Biggleswade, Beds. The dismantled Gnome engine and parts of a second were found in a barrel, but during the very considerable work of restoration (including the re-insertion of the missing 18-inch fuselage bay) it was decided to fit a 'new' engine. This was the 50 hp Gnome No. 683 which had formerly powered the single-seat Sopwith Type SL.T.B.P. biplane, Harry Hawker's 1914-18 war personal transport. This engine bore the date stamp 6.8.1916 and was sold to R. O. Shuttleworth by Mr R. C. Shelley of Billericay, Essex, who had owned the SL.T.B.P. for a time in 1926.

Work was held up by the outbreak of the 1939-45 war, and it is a tribute to the patience and skill of the Shuttleworth engineers, led by the indefatigable Sqn Ldr L. A. Jackson, that when the work was eventually completed the monoplane flew very well despite the low power output of the old Gnome engine. All the secondary structure of the mainplane, the fittings and wing tip bends are the originals, but new mainspars were made and fitted. The old engine cowlings, quite unserviceable, were replaced by replicas but, apart from this, a few small wooden members and the fabric, all the rest of the structure remains just as it was in 1913.

The first post-restoration flight was made by Air Commodore (then Grp Capt) A. H. Wheeler at Henlow on 17 September 1949 and by 1966 the Blackburn Single-Seat Monoplane had completed 10 hrs in the air. During two decades it has flown in public on many occasions, one of the first being the RAE At Home of 25 September 1949 when Air Commodore Wheeler made three very successful circuits of Farnborough. It performed well in the hands of Sqn Ldr Gordon Banner at the RAF Display, Farnborough, on 7-8 July 1950 and at the RAeS Garden Party, White Waltham, on 6 May 1951. More recently it posed alongside the latest Blackburn Buccaneer strike-fighter at Holme-on-Spalding Moor on 16 April 1962, to mark the 50th anniversary of military aviation, and at Booker among sundry replica aircraft of the period during the filming of 'Those Magnificent Men and their Flying Machines'. Built well over 50 years ago, it is the earliest British design in the Shuttleworth Collection and the oldest flyable British aircraft. For this reason it is regrettable that there is no record of its Blackburn type letter, the brass plate on its dashboard which reads Type B No. 725 being completely meaningless in any Blackburn context.

SPECIFICATION AND DATA

Manufacturers: The Blackburn Aeroplane Co, Balm Road, Leeds, Yorks.

Power Plant: One 50 hp Gnome

Dimensions:

Span 32 ft 1 in Length 26 ft 3 in

Height 8 ft 9 in Wing area 256 sq ft

Weights: Tare weight 550 lb. All-up weight 980 lb

Performance: Maximum speed 60 mph Endurance 21-3 hr

Production: One aircraft only, first flown at Leeds March 1913; crashed at Wittering 1914; rebuilt by the Shuttleworth Trust 1938-47; preserved in airworthy condition at Old Warden, Beds.

On 19 October 1912 Mr Cyril E. Foggin qualified for Aviator's Certificate No. 349 on a Bleriot monoplane of the Eastbourne Aviation Co and soon afterwards placed an order with Robert Blackburn for a private aeroplane. This was a single-seat monoplane built of selected English ash, fabric-covered and powered by a 50 hp Gnome rotary. It was smaller, more compact and streamlined than the Mercury but retained the triangular-section fuselage and wire-braced, square-cut warping wing which was rectangular in planform with I-section spars machined out of straight-grained ash over which were slipped silver spruce ribs with cottonwood flanges. The fabric was held in place by a beading of split cane along each rib. The mainplane was braced to the undercarriage by three flying wires and also to the top of a central pylon which also carried the pulleys for the upper warping cable.

External features which gave the new single-seater a modern appearance were the curved top-decking, the aluminium-plated front fuselage, the one-piece rudder with divided elevator, and the simplified, two-wheel, bungee-sprung undercarriage. For the first time in a Blackburn aeroplane the rudder was operated by a foot bar, and a small, universally mounted, wing-warping wheel was situated on top of the control column. From the pilot's point of view a most disconcerting feature was a crossbar, joining the root ends of the rear wing-spar, which clamped across his lap after he had taken his seat.

The machine was completed with commendable speed and first flew unpainted, in the hands of Harold Blackburn, at the end of 1912. Its rate of climb was a marked improvement on that of its predecessors, and the machine appeared for the first time in public at Lofthouse Park, Leeds, on Good Friday, 21 March 1913, when Blackburn began ten days of demonstration flying which included circuits of Wakefield. The owner, Cyril Foggin, flew it for the first time on Easter Monday, 24 March, and was airborne for 20 min. Exhaust fumes and hot oil, when thrown back into the cockpit do not make for safe and enjoyable flying, and after a few flights the rather abbreviated engine cowling was extended down to the line of the top longerons.

Further demonstration flying with Harold Blackburn at the controls then took place at Lofthouse Park (later known as the Yorkshire Aerodrome) at intervals until the end of May. Cross-country flights were also made to Stamford on 2 and 3 April, when he dropped 2,500 leaflets from 1,200 ft. With the aid of map and compass - one of the earliest attempts at accurate navigation - he flew to Harrogate on 29 April and landed on the Stray in front of the Queen's Hotel, having covered the 18 miles in as many minutes and reached a height of 4,000 ft en route. Finally, on 23, 24 and 25 July, he made daily newspaper flights between Leeds and York to deliver bundles of the Yorkshire Post.

The original hooked undercarriage skids were later replaced by the more usual and less lethal hockey stick variety, and a new mainplane with rounded tips similar to that used on its two-seat derivative, the Type I, was also fitted. Foggin then sold the machine to Montague F. Glew, whom he had met at the Blackburn School, Hendon, earlier in the year. Glew, who on 4 February 1913 had qualified on a Blackburn Mercury for Aviator's Certificate No. 410, flew and eventually crashed the ex-Foggin machine on his father's farm at Wittering, Lines., adjacent to the site of the present RAF aerodrome.

Reconstruction began by cutting 18 in off the fuselage longerons behind the engine bearer plate and this has been interpreted as a C.G. adjustment consistent with an attempt to install a heavier and more powerful engine, but such a scheme was never mentioned by M. F. Glew.

When war came later in 1914, the components were stored in a farm building, where they were discovered by the late R. O. Shuttleworth almost a quarter of a century later, in 1938. Several of the major airframe assemblies were lying under hay but all were collected together and conveyed to the Shuttleworth headquarters at Old Warden Aerodrome, Biggleswade, Beds. The dismantled Gnome engine and parts of a second were found in a barrel, but during the very considerable work of restoration (including the re-insertion of the missing 18-inch fuselage bay) it was decided to fit a 'new' engine. This was the 50 hp Gnome No. 683 which had formerly powered the single-seat Sopwith Type SL.T.B.P. biplane, Harry Hawker's 1914-18 war personal transport. This engine bore the date stamp 6.8.1916 and was sold to R. O. Shuttleworth by Mr R. C. Shelley of Billericay, Essex, who had owned the SL.T.B.P. for a time in 1926.

Work was held up by the outbreak of the 1939-45 war, and it is a tribute to the patience and skill of the Shuttleworth engineers, led by the indefatigable Sqn Ldr L. A. Jackson, that when the work was eventually completed the monoplane flew very well despite the low power output of the old Gnome engine. All the secondary structure of the mainplane, the fittings and wing tip bends are the originals, but new mainspars were made and fitted. The old engine cowlings, quite unserviceable, were replaced by replicas but, apart from this, a few small wooden members and the fabric, all the rest of the structure remains just as it was in 1913.

The first post-restoration flight was made by Air Commodore (then Grp Capt) A. H. Wheeler at Henlow on 17 September 1949 and by 1966 the Blackburn Single-Seat Monoplane had completed 10 hrs in the air. During two decades it has flown in public on many occasions, one of the first being the RAE At Home of 25 September 1949 when Air Commodore Wheeler made three very successful circuits of Farnborough. It performed well in the hands of Sqn Ldr Gordon Banner at the RAF Display, Farnborough, on 7-8 July 1950 and at the RAeS Garden Party, White Waltham, on 6 May 1951. More recently it posed alongside the latest Blackburn Buccaneer strike-fighter at Holme-on-Spalding Moor on 16 April 1962, to mark the 50th anniversary of military aviation, and at Booker among sundry replica aircraft of the period during the filming of 'Those Magnificent Men and their Flying Machines'. Built well over 50 years ago, it is the earliest British design in the Shuttleworth Collection and the oldest flyable British aircraft. For this reason it is regrettable that there is no record of its Blackburn type letter, the brass plate on its dashboard which reads Type B No. 725 being completely meaningless in any Blackburn context.

SPECIFICATION AND DATA

Manufacturers: The Blackburn Aeroplane Co, Balm Road, Leeds, Yorks.

Power Plant: One 50 hp Gnome

Dimensions:

Span 32 ft 1 in Length 26 ft 3 in

Height 8 ft 9 in Wing area 256 sq ft

Weights: Tare weight 550 lb. All-up weight 980 lb

Performance: Maximum speed 60 mph Endurance 21-3 hr

Production: One aircraft only, first flown at Leeds March 1913; crashed at Wittering 1914; rebuilt by the Shuttleworth Trust 1938-47; preserved in airworthy condition at Old Warden, Beds.

Cyril Foggin (right) and Harold Blackburn with the Single-Seat Monoplane at Lofthouse Park, Leeds, in March 1913. The original square-cut wing tips and hooked undercarriage skids are noteworthy.

The Blackburn Single-Seat Monoplane, new and unpainted, out for its first engine run at Leeds late in 1912, with Harold Blackburn at the controls.

The Single-Seat Monoplane after restoration by the Shuttleworth Trust, flying at the RAF Display, Farnborough, July 1950, piloted by Sq Ldr G. Banner.

The 1912 Blackburn Monoplane and a production Buccaneer S. Mk 1, XN924, at Holme-on-Spalding Moor, 16 April 1962.

M. F. Glcw (cloth cap) sitting on the engine of the Single-Seat Monoplane after the crash at Wittering in 1914.

Blackburn Type E

During 1911 the efforts of Robert Blackburn and other British pioneers produced a number of sturdy aeroplanes with good flying characteristics which challenged the supremacy of French machines to the point where the placing of military contracts for British-built aircraft could not long be delayed. As expected, the War Office issued its first military aircraft specification in November that year and called for a reconnaissance two-seater able to carry a useful load of 350 lb over and above essential equipment and to have an initial rate of climb of 200 ft min, 4 1/2 hr endurance, 55 mph maximum speed and able to maintain 4,500 ft for 1 hr. It also had to be transportable in a crate from one operational area to another. Competing firms were given just nine months in which to design, build and test before the commencement of competitive trials on Salisbury Plain in August 1912.