Книги

Putnam

D.James

Schneider Trophy Aircraft 1913-1931

33

D.James - Schneider Trophy Aircraft 1913-1931 /Putnam/

Commander Oliver Schwann taxi-ing his much modified Avro Type D floatplane at Barrow-in-Furness during August 1911. Numerous float designs were tried before the aircraft would take off.

The Avro 539 Falcon taking off during the elimination trials for the 1919 contest. The large amount of 'down' aileron on the port mainplanes and the way the port float is digging in make an interesting comparison with the photograph of the Nieuport

Fairey III

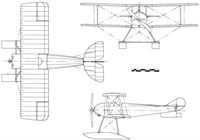

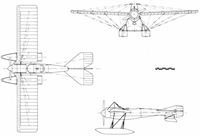

The Fairey III G-EALQ, sometimes known as the N.10 or by its construction number F.128, was the sole prototype of a carrier-based floatplane built to Admiralty specification N.2 (a) during the summer of 1917. It made its first flight from the Isle of Grain on 14 September, piloted by Lieut-Cmdr Vincent Nicholl, just two weeks after delivery from the Hamble factory to the RNAS.

Powered initially by a 260 hp Sunbeam Maori II twelve-cylinder liquid-cooled vee engine, the Fairey III was of wooden construction, with spruce and ash being used for the mainplane and fuselage structure, the whole being fabric covered. In its original form the aircraft had equal-span two-bay folding mainplanes having full-span variable-camber gear on the lower unit and with ailerons only on the upper unit. There were square-section single-step main floats, and a large tail float.

It was extensively modified at the Isle of Grain experimental establishment for test flying as a floatplane and as a landplane during 1917-19; it was then bought back by the Fairey company for competition and communications flying.

For its 1919 Schneider Trophy outing at Bournemouth, G-EALQ was modified yet again to a single-bay configuration and was powered by a 450 hp Napier Lion twelve-cylinder liquid-cooled broad-arrow engine. After the contest, in which the Fairey III, flown by Vincent Nicholl, retired in the first lap due to complete lack of visibility in the fog which enshrouded the course, this aircraft reappeared in August 1920 with a combined wheel/float undercarriage for an Air Ministry competition for commercial aircraft. It was placed third - and last - in the amphibian section, but won a £2,000 prize. This aeroplane was scrapped in 1922 but was the forerunner of the long line of Fairey III variants and sub-variants which, with one exception, were produced in greater numbers than any other British military type between 1918 and the era of the Royal Air Force expansion scheme in the mid-1930s.

Two-seat twin-float biplane. Wooden construction with fabric covering. Pilot in open rear cockpit, front cockpit faired over.

450 hp Napier Lion twelve-cylinder liquid-cooled broad-arrow engine driving a two-blade fixed-pitch wooden propeller of about 9 ft (2-74 m) diameter.

Span 28ft (8-53m); length 36ft (10-97m); height 10ft 6in (3-2m).

Maximum speed at sea level 108mph (173 8km/h).

Production - one prototype Fairey III built by Fairey Aviation Co Ltd, Hayes and Hamble, in 1917.

Colour - believed white upper wing, rear fuselage sides and rudder, with blue lower wing, forward fuselage sides and top decking, fin, tailplane, elevators, main and tail floats.

The Fairey III G-EALQ, sometimes known as the N.10 or by its construction number F.128, was the sole prototype of a carrier-based floatplane built to Admiralty specification N.2 (a) during the summer of 1917. It made its first flight from the Isle of Grain on 14 September, piloted by Lieut-Cmdr Vincent Nicholl, just two weeks after delivery from the Hamble factory to the RNAS.

Powered initially by a 260 hp Sunbeam Maori II twelve-cylinder liquid-cooled vee engine, the Fairey III was of wooden construction, with spruce and ash being used for the mainplane and fuselage structure, the whole being fabric covered. In its original form the aircraft had equal-span two-bay folding mainplanes having full-span variable-camber gear on the lower unit and with ailerons only on the upper unit. There were square-section single-step main floats, and a large tail float.

It was extensively modified at the Isle of Grain experimental establishment for test flying as a floatplane and as a landplane during 1917-19; it was then bought back by the Fairey company for competition and communications flying.

For its 1919 Schneider Trophy outing at Bournemouth, G-EALQ was modified yet again to a single-bay configuration and was powered by a 450 hp Napier Lion twelve-cylinder liquid-cooled broad-arrow engine. After the contest, in which the Fairey III, flown by Vincent Nicholl, retired in the first lap due to complete lack of visibility in the fog which enshrouded the course, this aircraft reappeared in August 1920 with a combined wheel/float undercarriage for an Air Ministry competition for commercial aircraft. It was placed third - and last - in the amphibian section, but won a £2,000 prize. This aeroplane was scrapped in 1922 but was the forerunner of the long line of Fairey III variants and sub-variants which, with one exception, were produced in greater numbers than any other British military type between 1918 and the era of the Royal Air Force expansion scheme in the mid-1930s.

Two-seat twin-float biplane. Wooden construction with fabric covering. Pilot in open rear cockpit, front cockpit faired over.

450 hp Napier Lion twelve-cylinder liquid-cooled broad-arrow engine driving a two-blade fixed-pitch wooden propeller of about 9 ft (2-74 m) diameter.

Span 28ft (8-53m); length 36ft (10-97m); height 10ft 6in (3-2m).

Maximum speed at sea level 108mph (173 8km/h).

Production - one prototype Fairey III built by Fairey Aviation Co Ltd, Hayes and Hamble, in 1917.

Colour - believed white upper wing, rear fuselage sides and rudder, with blue lower wing, forward fuselage sides and top decking, fin, tailplane, elevators, main and tail floats.

The Fairey III, or N10, G-EALQ which was entered for the 1919 contest as a single-bay floatplane is seen here after conversion to a two-bay amphibian for the 1920 Air Ministry amphibian competition in which it was placed third.

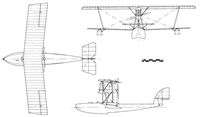

Sopwith Tabloid

Great Britain’s first Schneider Trophy aspirant was the Sopwith Tabloid, a small biplane which was designed by T. O. M. Sopwith and Fred Sigrist. The side-by-side two-seat Tabloid prototype, which was first flown in November 1913 by Harry Hawker, the Sopwith Aviation test pilot, was later to be energetically developed into an effective little single-seat scout for use by the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service during the First World War.

Powered by an 80 hp Gnome nine-cylinder air-cooled rotary engine driving a two-blade wooden propeller, the Tabloid was of wire-braced fabric-covered all-wood construction. It featured slightly staggered biplane wings of constant 5 ft (1-52 m) chord; and with only a single pair of interplane struts in the 4 ft 3 in (1-29 m) gap, and two centre-section struts each side, it was one of the few single-bay biplanes of that period. Ailerons were not fitted and lateral control was achieved by wing-warping. A large bull-nosed metal cowling enclosed the engine and metal panels extended aft to clad the fuselage sides back to the cockpit. A ‘comma’ shaped rudder - which shape typified many subsequent Sopwith aeroplanes - without a fin was used with a large-area tailplane and elevators. These flying surfaces were cable operated. A twin wheel-and-skid main undercarriage and a tailskid were conventional features.

Great Britain’s first Schneider Trophy aspirant was the Sopwith Tabloid, a small biplane which was designed by T. O. M. Sopwith and Fred Sigrist. The side-by-side two-seat Tabloid prototype, which was first flown in November 1913 by Harry Hawker, the Sopwith Aviation test pilot, was later to be energetically developed into an effective little single-seat scout for use by the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service during the First World War.

Powered by an 80 hp Gnome nine-cylinder air-cooled rotary engine driving a two-blade wooden propeller, the Tabloid was of wire-braced fabric-covered all-wood construction. It featured slightly staggered biplane wings of constant 5 ft (1-52 m) chord; and with only a single pair of interplane struts in the 4 ft 3 in (1-29 m) gap, and two centre-section struts each side, it was one of the few single-bay biplanes of that period. Ailerons were not fitted and lateral control was achieved by wing-warping. A large bull-nosed metal cowling enclosed the engine and metal panels extended aft to clad the fuselage sides back to the cockpit. A ‘comma’ shaped rudder - which shape typified many subsequent Sopwith aeroplanes - without a fin was used with a large-area tailplane and elevators. These flying surfaces were cable operated. A twin wheel-and-skid main undercarriage and a tailskid were conventional features.

A HISTORICAL EVENT. - Mr. Hawker, on the first Sopwith side-by-side two-seater "Tabloid," pays bis first flying visit to Hendon in 1913.

The little Sopwith Tabloid which was converted into a floatplane in 1914 to give Great Britain its first Schneider Trophy victory.

The little Sopwith Tabloid which was converted into a floatplane in 1914 to give Great Britain its first Schneider Trophy victory.

Sopwith Tabloid

<...>

On 29 November at the Royal Aircraft Factory, Farnborough, the Tabloid achieved a maximum speed of 92mph with a 36-9 mph stalling speed during official trials, and later the same day was displayed by Hawker at a Hendon flying meeting before some 50,000 people. From his own experience of air racing, Sopwith knew its value in terms of publicity and as a stimulus to engineering and aerodynamic development of aircraft. Accordingly, he decided to modify an early production Tabloid as a seaplane for the 1914 Schneider contest due to take place at Monaco on 20 April, and engaged C. Howard Pixton, an experienced Australian pilot, to undertake the development testing and to fly the Tabloid in the contest. More power was a prime need and Sopwith chose a new 100 hp Monosoupape Gnome rotary which differed from other Gnome engines by dispensing with inlet valves, having only single exhaust valves in each cylinder, hence its Monosoupape - ‘single-valve’ - name. A single central-float alighting gear with wingtip stabilizing floats was designed and fitted very rapidly - perhaps too rapidly - and at the end of March 1914 the Tabloid was moved from Sopwith’s Kingston-upon-Thames factory to a site on the Hamble river for water and air tests. These began on 1 April but when Pixton opened the throttle to taxi away from a jetty, the nose of the main float dug into the water and the aircraft turned over and sank. Fortunately Pixton was thrown out and managed to swim back to the jetty. In their haste to ready the Tabloid for Monaco, Sopwith, Sigrist and Sydney Burgoine, a boatbuilder, had rigged the float too far aft and it could not balance the increased power of the engine. The following morning the soaked and partially wrecked Tabloid was recovered from the mud, dismantled and returned to Kingston, where a new twin-float alighting gear was sketched out. Burgoine simply sawed through the single main float to produce a pair of smaller units which were completed by boxing in their now open inboard sides. Two spreader bars connected them and they were attached to the fuselage by two pairs of struts, the whole gear being wire braced. The underwing floats were removed, a small tail float was fitted, and a small triangular shaped fin was mounted in front of the rudder to balance the increased keel surface of the new floats. As there was insufficient time to return to the Hamble, some furtive early morning trials took place on 7 April on the Thames, initially just below Kingston Bridge, but when Thames Conservancy Board officials objected the Tabloid was moved to Ham below Teddington Lock where the Port of London Authority assumed control of the water, Teddington’s ancient name ‘Tide-end town’ being indicative of the significance of this point on the river. The water trials showed that the new floats performed very well, running smoothly on the surface during the take-off runs.

At Monaco a preliminary flight-trial two days before the contest was scheduled to take place showed that several modifications needed to be made. Pixton found that the engine was over-speeding and the Gnome engine company representatives recommended that, as the large diameter moderate-pitch propeller allowed the engine to run at 1,350 rpm, which was too fast for the contest (expected to last some two hours), a smaller-diameter propeller of coarser pitch should be fitted. An extra six-gallon fuel tank was fitted to increase the flight duration and stronger float bracing wires replaced the original wires which had stretched during the flight trial.

The successful development and modification of the Tabloid as a seaplane not only bore fruit in the contest but also led to the production of the Sopwith Schneider, a single-seat scout seaplane, for the RNAS. Powered by a 100 hp Monosoupape Gnome engine, the Schneider differed very little from Pixton’s Tabloid, the major changes being an extra pair of struts in the alighting gear, a water rudder on the tail float, an increased area fin, the use of ailerons on all four wings in place of wing-warping, and the angled mounting of a Lewis gun firing through an aperture in the upper centre section. The Sopwith Baby was a further aerodynamically refined development which made a valuable contribution to coastal air defence of the United Kingdom during 1915-16. Whatever else justified the creation and development of the Tabloid, it occupies a unique position as the progenitor of an apparently endless line of scouts, fighters and attack aircraft to emanate from Kingston.

Single-seat twin-float racing biplane. Wooden construction with fabric covering. Pilot in open cockpit.

One 100hp Gnome Monosoupape nine-cylinder air-cooled rotary engine with a 7 ft 6 in (2-28 m) diameter two-blade fixed-pitch carved mahogany propeller.

Span 25 ft 6 in (7-77 m); length 20 ft (6 m); height 10 ft (3 m); wing area 240 sq ft (22-29 sq m).

Empty weight 992lb (450 kg); loaded weight 1,433lb (650 kg); wing loading 6 Ib/sq ft (29-29 kg/sq m).

Maximum speed at sea level 92mph (148km/h); stalling speed 38mph (61 km/h).

Production - one Tabloid floatplane racer built by Sopwith at Kingston-upon-Thames in 1914.

Colour - pale golden yellow overall with black markings - SOPWITH on fuselage sides, contest number 3 on rudder - polished aluminium engine cowling and cockpit decking; and varnished natural wood floats and interplane struts.

<...>

On 29 November at the Royal Aircraft Factory, Farnborough, the Tabloid achieved a maximum speed of 92mph with a 36-9 mph stalling speed during official trials, and later the same day was displayed by Hawker at a Hendon flying meeting before some 50,000 people. From his own experience of air racing, Sopwith knew its value in terms of publicity and as a stimulus to engineering and aerodynamic development of aircraft. Accordingly, he decided to modify an early production Tabloid as a seaplane for the 1914 Schneider contest due to take place at Monaco on 20 April, and engaged C. Howard Pixton, an experienced Australian pilot, to undertake the development testing and to fly the Tabloid in the contest. More power was a prime need and Sopwith chose a new 100 hp Monosoupape Gnome rotary which differed from other Gnome engines by dispensing with inlet valves, having only single exhaust valves in each cylinder, hence its Monosoupape - ‘single-valve’ - name. A single central-float alighting gear with wingtip stabilizing floats was designed and fitted very rapidly - perhaps too rapidly - and at the end of March 1914 the Tabloid was moved from Sopwith’s Kingston-upon-Thames factory to a site on the Hamble river for water and air tests. These began on 1 April but when Pixton opened the throttle to taxi away from a jetty, the nose of the main float dug into the water and the aircraft turned over and sank. Fortunately Pixton was thrown out and managed to swim back to the jetty. In their haste to ready the Tabloid for Monaco, Sopwith, Sigrist and Sydney Burgoine, a boatbuilder, had rigged the float too far aft and it could not balance the increased power of the engine. The following morning the soaked and partially wrecked Tabloid was recovered from the mud, dismantled and returned to Kingston, where a new twin-float alighting gear was sketched out. Burgoine simply sawed through the single main float to produce a pair of smaller units which were completed by boxing in their now open inboard sides. Two spreader bars connected them and they were attached to the fuselage by two pairs of struts, the whole gear being wire braced. The underwing floats were removed, a small tail float was fitted, and a small triangular shaped fin was mounted in front of the rudder to balance the increased keel surface of the new floats. As there was insufficient time to return to the Hamble, some furtive early morning trials took place on 7 April on the Thames, initially just below Kingston Bridge, but when Thames Conservancy Board officials objected the Tabloid was moved to Ham below Teddington Lock where the Port of London Authority assumed control of the water, Teddington’s ancient name ‘Tide-end town’ being indicative of the significance of this point on the river. The water trials showed that the new floats performed very well, running smoothly on the surface during the take-off runs.

At Monaco a preliminary flight-trial two days before the contest was scheduled to take place showed that several modifications needed to be made. Pixton found that the engine was over-speeding and the Gnome engine company representatives recommended that, as the large diameter moderate-pitch propeller allowed the engine to run at 1,350 rpm, which was too fast for the contest (expected to last some two hours), a smaller-diameter propeller of coarser pitch should be fitted. An extra six-gallon fuel tank was fitted to increase the flight duration and stronger float bracing wires replaced the original wires which had stretched during the flight trial.

The successful development and modification of the Tabloid as a seaplane not only bore fruit in the contest but also led to the production of the Sopwith Schneider, a single-seat scout seaplane, for the RNAS. Powered by a 100 hp Monosoupape Gnome engine, the Schneider differed very little from Pixton’s Tabloid, the major changes being an extra pair of struts in the alighting gear, a water rudder on the tail float, an increased area fin, the use of ailerons on all four wings in place of wing-warping, and the angled mounting of a Lewis gun firing through an aperture in the upper centre section. The Sopwith Baby was a further aerodynamically refined development which made a valuable contribution to coastal air defence of the United Kingdom during 1915-16. Whatever else justified the creation and development of the Tabloid, it occupies a unique position as the progenitor of an apparently endless line of scouts, fighters and attack aircraft to emanate from Kingston.

Single-seat twin-float racing biplane. Wooden construction with fabric covering. Pilot in open cockpit.

One 100hp Gnome Monosoupape nine-cylinder air-cooled rotary engine with a 7 ft 6 in (2-28 m) diameter two-blade fixed-pitch carved mahogany propeller.

Span 25 ft 6 in (7-77 m); length 20 ft (6 m); height 10 ft (3 m); wing area 240 sq ft (22-29 sq m).

Empty weight 992lb (450 kg); loaded weight 1,433lb (650 kg); wing loading 6 Ib/sq ft (29-29 kg/sq m).

Maximum speed at sea level 92mph (148km/h); stalling speed 38mph (61 km/h).

Production - one Tabloid floatplane racer built by Sopwith at Kingston-upon-Thames in 1914.

Colour - pale golden yellow overall with black markings - SOPWITH on fuselage sides, contest number 3 on rudder - polished aluminium engine cowling and cockpit decking; and varnished natural wood floats and interplane struts.

Scarcely visible. Howard Pixton, winner of the 1914 Schneider Trophy Race at Monaco, lounges nonchalantly in the shadow of the port upper mainplane of the Sopwith Tabloid at Monaco in 1914. The rear part of the floats and support struts are under water, as is the elevator trailing edge.

Surely one of the most enticing 'Wish you were here' postcards ever printed (for, like the preceding Tabloid floatplane picture, it was indeed produced in postcard form) this view calls for little remark beyond affirming that the Sopwith caption reads: '43-100 hp Seaplane. Winner of Schneider Cup at Monaco. April/1914.'

Howard Pixton under way in the Sopwith Tabloid in front of the exotic casinos and hotels of Monaco.

Howard Pixton under way in the Sopwith Tabloid in front of the exotic casinos and hotels of Monaco.

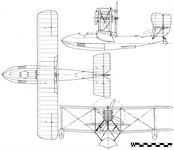

Sopwith Schneider

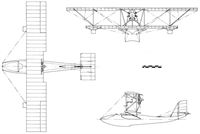

For the first postwar Schneider Trophy contest Tom Sopwith decided to build a new floatplane, using all of his company’s wartime experience of making fast, manoeuvrable fighter-type aircraft. In addition, he abandoned the well-established rotary and inline engines and chose instead the new 450 hp Jupiter nine-cylinder air-cooled direct-drive radial engine, designed by Roy Fedden of Cosmos Engineering Ltd. The circular shape of the Jupiter dictated the cross-sectional shape of the new floatplane’s fuselage, and Sopwith’s designer, W. George Carter, produced a business-like aircraft with good lines. The fuselage was built up from ash longerons with spruce struts and ply formers carrying stringers to give a curved shape to the sides. Fuel was carried in tanks mounted in front of the pilot’s cockpit and immediately aft of a large circular steel-faced multi-ply wooden engine-mounting bulkhead. The single-bay biplane wings had ash spars with spruce struts and ribs. Ailerons were fitted to the upper and lower wings and were interconnected with single streamlined wires. An unusual feature was that the upper wings were staggered 2 1/2in behind the lower wings. The wire-braced tail unit was a wooden structure and, like the remainder of the rear fuselage and the wings, was fabric covered. All the flying control cable runs were inside the main structure and bestowed a very clean external appearance to the Schneider. Aluminium panels enclosed the forward part of the fuselage, and the engine cowling, through which protruded the heavily finned cylinders, was also of aluminium. A large spinner closed the aperture through which the splined propeller shaft passed to drive a two-blade fixed-pitch wooden propeller. The four wooden struts of the alighting gear carried two flat-sided stepless, almost symmetrical, aerofoil-section wooden floats. A small windscreen and faired headrest were provided for the pilot who sat in an open cockpit positioned beneath the trailing edge of the upper wing. Registered G-EAKI and flown by Harry Hawker in the 1919 contest in fog at Bournemouth, the Schneider was a potentially fast entrant which had little opportunity to show its paces in the poor conditions.

After the contest the floats were removed and a wheeled undercarriage fitted. Renamed Rainbow, G-EAKI had 3 ft clipped from its wing-span and was re-engined with an ABC Dragonfly air-cooled radial engine for the 1920 Aerial Derby, from which it was disqualified due to an incorrect finish. It was later entered for the Gordon Bennett race but was lacking a good engine, and when, in September 1920, the Sopwith Engineering Co closed through financial troubles, the Rainbow was withdrawn - although a private enterprise effort by a group of racing enthusiasts and sportsmen almost got it flying again. With the formation of H. G. Hawker Engineering Co Ltd in the same month, the aircraft was again equipped with a Jupiter engine, renamed the Sopwith Hawker and flew in the 1923 Aerial Derby, in which it finished in second place.

Plans to convert G-EAKI back to a floatplane for that year’s Schneider Trophy contest never came to fruition and the aircraft was completely written off in a forced landing on 5 October, 1923.

Single-seat twin-float racing biplane. All-wood construction with fabric and metal covering. Pilot in open cockpit.

One 450 hp Cosmos Jupiter nine-cylinder air-cooled direct-drive normally-aspirated radial engine driving an 8 ft 4 in (2-54 m) two-blade fixed-pitch wooden propeller.

Span 24 ft (7-31 m); length 21 ft 6 in (6-55 m); height 10 ft 6 in (3-2 m); wing area 222 sq ft (20-62 sq m).

Empty weight 1,750 lb (794 kg); loaded weight 2,200 lb (998 kg); wing loading 9-92 Ib/sq ft (48-43 kg/sq m) - approximate figures.

Maximum speed at sea level 170 mph (273-58 km/h); stalling speed 55 mph (88-51 km/h) - estimated figures.

Production - one Schneider built by Sopwith Engineering Co Ltd at Kingston-upon-Thames in 1919.

Colour - believed all-over blue with white interplane and alighting gear struts; white panel on fuselage sides carrying black registration letters G-EAKI and white panel on rudder carrying black national identity prefix letter G; Sopwith in white letters on fin. The allocated contest number 3 was not carried.

For the first postwar Schneider Trophy contest Tom Sopwith decided to build a new floatplane, using all of his company’s wartime experience of making fast, manoeuvrable fighter-type aircraft. In addition, he abandoned the well-established rotary and inline engines and chose instead the new 450 hp Jupiter nine-cylinder air-cooled direct-drive radial engine, designed by Roy Fedden of Cosmos Engineering Ltd. The circular shape of the Jupiter dictated the cross-sectional shape of the new floatplane’s fuselage, and Sopwith’s designer, W. George Carter, produced a business-like aircraft with good lines. The fuselage was built up from ash longerons with spruce struts and ply formers carrying stringers to give a curved shape to the sides. Fuel was carried in tanks mounted in front of the pilot’s cockpit and immediately aft of a large circular steel-faced multi-ply wooden engine-mounting bulkhead. The single-bay biplane wings had ash spars with spruce struts and ribs. Ailerons were fitted to the upper and lower wings and were interconnected with single streamlined wires. An unusual feature was that the upper wings were staggered 2 1/2in behind the lower wings. The wire-braced tail unit was a wooden structure and, like the remainder of the rear fuselage and the wings, was fabric covered. All the flying control cable runs were inside the main structure and bestowed a very clean external appearance to the Schneider. Aluminium panels enclosed the forward part of the fuselage, and the engine cowling, through which protruded the heavily finned cylinders, was also of aluminium. A large spinner closed the aperture through which the splined propeller shaft passed to drive a two-blade fixed-pitch wooden propeller. The four wooden struts of the alighting gear carried two flat-sided stepless, almost symmetrical, aerofoil-section wooden floats. A small windscreen and faired headrest were provided for the pilot who sat in an open cockpit positioned beneath the trailing edge of the upper wing. Registered G-EAKI and flown by Harry Hawker in the 1919 contest in fog at Bournemouth, the Schneider was a potentially fast entrant which had little opportunity to show its paces in the poor conditions.

After the contest the floats were removed and a wheeled undercarriage fitted. Renamed Rainbow, G-EAKI had 3 ft clipped from its wing-span and was re-engined with an ABC Dragonfly air-cooled radial engine for the 1920 Aerial Derby, from which it was disqualified due to an incorrect finish. It was later entered for the Gordon Bennett race but was lacking a good engine, and when, in September 1920, the Sopwith Engineering Co closed through financial troubles, the Rainbow was withdrawn - although a private enterprise effort by a group of racing enthusiasts and sportsmen almost got it flying again. With the formation of H. G. Hawker Engineering Co Ltd in the same month, the aircraft was again equipped with a Jupiter engine, renamed the Sopwith Hawker and flew in the 1923 Aerial Derby, in which it finished in second place.

Plans to convert G-EAKI back to a floatplane for that year’s Schneider Trophy contest never came to fruition and the aircraft was completely written off in a forced landing on 5 October, 1923.

Single-seat twin-float racing biplane. All-wood construction with fabric and metal covering. Pilot in open cockpit.

One 450 hp Cosmos Jupiter nine-cylinder air-cooled direct-drive normally-aspirated radial engine driving an 8 ft 4 in (2-54 m) two-blade fixed-pitch wooden propeller.

Span 24 ft (7-31 m); length 21 ft 6 in (6-55 m); height 10 ft 6 in (3-2 m); wing area 222 sq ft (20-62 sq m).

Empty weight 1,750 lb (794 kg); loaded weight 2,200 lb (998 kg); wing loading 9-92 Ib/sq ft (48-43 kg/sq m) - approximate figures.

Maximum speed at sea level 170 mph (273-58 km/h); stalling speed 55 mph (88-51 km/h) - estimated figures.

Production - one Schneider built by Sopwith Engineering Co Ltd at Kingston-upon-Thames in 1919.

Colour - believed all-over blue with white interplane and alighting gear struts; white panel on fuselage sides carrying black registration letters G-EAKI and white panel on rudder carrying black national identity prefix letter G; Sopwith in white letters on fin. The allocated contest number 3 was not carried.

The completed Sopwith Schneider, with the polished aluminium engine cowling, cylinder fairings and front fuselage panels, the sturdy interplane struts and broad-chord mainplanes, and the design of the twin floats, well displayed in this view.

The first Cosmos Jupiter engine being installed in the Sopwith Schneider fuselage at Sopwith’s Canbury Park Road factory at Kingston. The main fuel and oil tanks are in the uncovered front fuselage section.

Supermarine Sea Lion I

The old Pemberton Billing Co. and its Supermarine Works at Woolston, near Southampton, were bought by Hubert Scott-Paine in 1916 when Noel Pemberton Billing became a Member of Parliament. It was renamed Supermarine Aviation Works and in 1918 designed and built the Baby, to Air Board specification N.1B, which was one of the very few single-seat fighter flying-boats to be produced during the First World War. The Baby was a biplane with a wing span of 30ft 6 in (9-29 m) and, powered by a 200 hp Hispano-Suiza engine, had a maximum speed of 116 mph (186-6 km/h). Two prototypes, N59-60, were built and flown, but the Baby did not go into quantity production because military requirements changed.

When the Schneider Trophy contests were re-established in 1919 and the first postwar venue was to be Bournemouth, Scott-Paine decided that because of its proximity to the Supermarine factory his company would enter the lists. Since time was short, he obtained one of the Babies, whose forward hull had been modified to reduce spray while on the water as part of a programme to produce a civil Baby to be known as the Sea King. The Hispano-Suiza engine was replaced by a 450 hp Napier Lion twelve-cylinder broad-arrow engine driving a two-blade wooden pusher propeller. Although the redesign of this aircraft was to produce a purely racing machine, it was fully equipped with a bilge pump, sea anchor and mooring equipment. The hull, of Linton Hope design, was of similar construction to that used in the Blackburn Pellet. The single-bay mainplanes and centre section were built up around two spruce spars and wooden ribs which were fabric covered. The four mainplanes were built separately and were rigged without stagger but with dihedral from the flat centre section. Large balanced ailerons were carried on all four mainplanes. The interplane struts were sloped out toward the tops to support the longer-span upper mainplane. Deep, narrow, stabilizing floats were carried beneath the lower mainplanes. The tailplane was mounted on top of the fin and was braced on each side by a pair of steel-tube struts to the hull. A horn-balanced rudder, extended downward to act as a water rudder, was carried on the fin which was covered with wood sheeting. The remainder of the tail unit was of wood and fabric construction. The engine was mounted on four steel-tube struts carrying two ash engine-bearers and supported the upper centre section on four more struts. An oval-shaped radiator was mounted in front of the engine and was enclosed in an aluminium nacelle. The redesign work was entrusted to the young Reginald J. Mitchell, who in later years was to become renowned as the designer of a series of Supermarine racing floatplanes for the Schneider contests and of the Spitfire.

The use of the Lion engine prompted the name Sea Lion for this little racer which received the civil registration G-EALP. The eliminating trials to select the British team were scheduled for 3 September, and while the Sopwith, Fairey, and Avro companies had flown their aircraft by the day before the trial, the Sea Lion’s first flight was delayed by the non-delivery of the propeller - due to a strike at the manufacturers. However, it arrived in time for engine running to begin at 8 p.m. in the evening before the trials; but torrential rain prevented these taking place. On 5 September Sqn Ldr Basil Hobbs, the Supermarine pilot, made the initial flight. Flight trials continued with all four British aircraft, the final decision to include the Sea Lion in place of the Avro entrant being delayed until 9 September when a new propeller gave the Sea Lion an additional five or six miles per hour.

The events of the contest day are recorded elsewhere in this book, but afterwards the Sea Lion was dismantled and its hull was loaned to the Science Museum in London for an exhibition in 1921. Sadly it was broken up some years later when the Museum no longer required it.

Single-seat racing biplane flying-boat. Wood and metal construction. Pilot in open cockpit.

One 450 hp Napier Lion IA twelve-cylinder water-cooled normally-aspirated geared broad-arrow engine driving a 7 ft 10 in (2-38 m) diameter two-blade fixed-pitch wooden propeller.

Span 35 ft (10-66 m); length 26 ft 4 in (8 02 m); height 11 ft 8 in (3-55 m); wing area 380 sq ft (35-3 sq m).

Empty weight 2,000lb (907kg); loaded weight 2,900lb (1,315kg); wing loading 7-63 Ib/sq ft (37-22 kg/sq m).

Maximum speed 147 mph (236-57 km/h).

Production - one Sea Lion I built by conversion of Baby by Supermarine Aviation Works, Woolston, Southampton, in 1919.

Colour - believed to have been dark blue hull and tailplane support struts, with remainder pale blue, grey or silver; engine nacelle natural aluminium; Supermarine in large white capital letters on hull sides forward of mainplanes with small Sea Lion above, white civil registration letters G-EALP on hull sides aft of mainplanes; white contest number 5 on fin.

Supermarine Sea Lion II

Expedience and economy were ever the watchwords of British aircraft manufacturers in the years between the wars and, clearly, were observed by Hubert Scott-Paine at Supermarine when producing aeroplanes for the Schneider contests. Following the use of the N.1B Baby hull in the Sea Lion I, when the decision was made to build an entrant for the 1922 contest the company used an existing airframe on which to base it. During 1919 two civil sporting amphibian versions of the Baby, named Sea King I, had been built but neither had been sold. One of these became the Sea Lion I; in 1921 the second was developed as the Sea King II, an amphibian fighting scout with a single .303-in Lewis machine-gun and provision for light bombs, but when it, too, failed to win orders it was modified to become the Sea Lion II G-EBAH.

The Sea King hull, constructed of circular-section wooden frames with wood skinning, was retained. The bow was modified, which shortened the Sea King hull to 24 ft 9 in (7-54 m) in its Sea Lion II form. A built-on wooden planing bottom and steps, which were divided into watertight compartments, were added. The upper surface was single-skin planking and the whole structure was covered with fabric and doped. The manually-operated wheeled undercarriage and all military equipment and fittings were removed. The Sea King’s mainplanes structure was retained, with four vertical interplane struts replacing the splayed-out struts of the Sea Lion I. The Sea King’s wing area was reduced by introducing a narrower chord in the mainplanes, and their span is believed to have been increased by 1ft 6in (45cm) to reach 32ft (9-75m). The mainplanes, built as four separate sections, were attached to the upper and lower centre sections. They were built up around two spruce spars with wooden ribs, all wire braced and fabric covered. In place of the earlier 300 hp Hispano-Suiza engine, a 450 hp Lion II, loaned by Napier, was installed, which drove a four-blade wooden pusher propeller of about 8 ft 6 in (2-59 m) diameter. To offset the increased torque and maintain stability, the fin area above the tailplane was enlarged by forward curvature of the leading edge. Because the engine was mounted high between the wings and produced a high thrust-line resulting in a pitching moment, the tailplane had a reverse camber to counteract this. Fuel was supplied to the engine by a high-pressure air system with all fuel lines being kept short and run as clear of the hull as possible.

The earlier Sea King II had not only proved itself capable of aerobatics - Henri Biard, Supermarine’s test pilot had rolled and spun the aircraft - but it had also been very stable at all speeds. These characteristics were inherited by the Sea Lion II which was a very tractable aeroplane.

The 1922 Schneider contest was scheduled to take place in Naples during the latter part of August, but the Italians decided to advance the date by some ten days. Unfortunately, the Sea Lion II was still incomplete when news of the change was received by the Royal Aero Club, and so the work was pressed ahead with all speed. When the day came for preliminary engine running the Lion started almost immediately and it was decided to make a preliminary test flight. With Biard aboard, the Sea Lion II got airborne very easily after a short take-off run - but suddenly, when it was some 200 ft over rows of luffing cranes and the masts of ships in Southampton Docks, the Lion engine stopped. Biard managed to pick out a stretch of clear water and glided down to alight safely. The Sea Lion was towed back to Woolston where a fault in the fuel system was diagnosed and corrected. But a precious day was used up.

The following evening Biard again flew the Sea Lion and, finding all was going well, opened the throttle wide to achieve a speed in excess of 150mph, faster than any British flying-boat had then flown. There followed several days while final modifications were made to the airframe and flying time was built up, then the Sea Lion was dismantled and crated for its journey by sea to Naples.

With the Sea Lion re-assembled, Biard and the Supermarine team launched a cloak-and-dagger operation, first to find out the strength of the French and Italian opposition, and then to conceal from their prying eyes and stop watches the capabilities of the British flying-boat. Accordingly, Biard confined his full-throttle runs to an area well clear of Naples Bay, and made sure that his practice circuits always included some cautious turns around the pylons. This plan worked so well that the Italians publicly proclaimed the inferiority of the Sea Lion when compared with the Macchi M.17 and Savoia S.51. But there was almost disaster, when he flew too close to Vesuvius in an attempt to look down into its crater, and a strong thermal suddenly lifted the Sea Lion some 2,000ft above its original flight path.

In the contest Biard’s tactical flying, plus the Sea Lion’s speed, brought the Trophy to Britain; additionally they established world closed-circuit speed, duration and distance records, the first to be recognized for seaplanes.

Soon after its return to the Supermarine factory, the Sea Lion II G-EBAH was bought by the Air Ministry for development flying work, but it has not been established whether it was moved to Felixstowe; it was not, however, removed from the Civil Aircraft Register.

There was also a plan to fly G-EBAH in the 1922 King’s Cup air race. That a flying-boat should take part in a race flown entirely over land was a tribute to the reliability of the Lion engine. A report in Flight of 7 September records that 'at the moment of going to press we learn this machine will not start'. There were no other references to the Sea Lion in reports of the race.

Single-seat racing biplane flying-boat. Wood and metal construction. Pilot in open cockpit.

One 450 hp Napier Lion II twelve-cylinder water-cooled normally-aspirated geared broad-arrow engine driving an 8 ft 6 in (2-59 m) diameter four-blade fixed-pitch wooden pusher propeller. Fuel: 55 gal (250 litres).

Span 32 ft (9-75m); length 24ft 9in (7-54m); height 12ft (3-65m) approx; wing area 384 sq ft (35 -67 sq m).

Empty weight 2,115lb (959kg); loaded weight 2.850lb (1,292kg); wing loading 7-42 Ib/sqft (36-22 kg/sq m).

Maximum speed 160mph (257-49 km/h).

Production - one Sea Lion II (G-EBAH) converted from Sea King II by Supermarine Aviation Works, Southampton, in 1922.

Colour - believed to have been overall blue hull, interplane and tailplane support struts; cream or white mainplanes and tailplane; white registration G-EBAH on rear hull sides and national letter G on rudder, black contest number 14 on white panel on hull sides aft of cockpit

Supermarine Sea Lion III

For the 1923 Schneider contest the Air Ministry decided that the old Sea Lion II G-EBAH should participate again. Reginald Mitchell at Supermarine rapidly produced drawings to initiate a general modification programme aimed at cleaning up the hull and increasing its fineness ratio. As a result the hull length was increased by 2 ft 9 in (83 cm). A new planing bottom was attached to the hull and the bow section refined; in addition the wing span was reduced by 4 ft (1-21 m), and the area of the fin and rudder was increased by making them taller.

During the flight-test programme the shoe-shaped floats were removed and oval-section stabilizing floats, with pairs of small hydrovanes at their forward end, were mounted on short struts and wire braced to the underside of the lower mainplanes near the tips. For the first time on a Sea Lion, a small glass windscreen was mounted in front of the open cockpit.

Power for the Sea Lion III came from a 525 hp Napier Lion III which drove a four-blade wooden pusher propeller. The engine, in its aluminium nacelle with a circular-section radiator housed in a long-chord tubular cowling, was supported on a pair of N-struts; the fuel lines were carried up inside a streamlined radiator support strut from the hull fuel tank to the engine.

A strange feature of this cleaning-up process was that the engine starting handle was permanently fixed to the power unit and protruded from the port side of the nacelle; moreover, the tailplane had no less than eight wire-braced support struts, and the original combined water-rudder/tailskid was retained.

In the contest, although Biard and the Sea Lion III returned a speed some 12 mph faster than that at which they had won the previous year’s event, they were outclassed by the Curtiss CR-3s and could only take third place.

During the first few weeks following the contest, Biard flew the Sea Lion III on some further flight trials; then during the first week of December it was taken on RAF charge, serialled N170 and moved to Felixstowe.

Single-seat racing biplane flying-boat. Wood and metal construction. Pilot in open cockpit.

One 525 hp Napier Lion III twelve-cylinder water-cooled normally-aspirated geared broad-arrow engine driving an 8 ft 8 in (2-64 m) diameter four-blade fixed-pitch wooden pusher propeller. Fuel: 60 gal (272 litres).

Span 28ft (8-53m); length 28ft (8-53m); wing area 360sq ft (33-44sq m).

Empty weight 2,400 lb (1,088 kg); loaded weight 3,275 lb (1,485 kg); wing loading 9-09 lb/ sq ft (44-4 kg/sq m).

Maximum speed 175 mph (281-61 km/h); alighting speed 55 mph (88-51 km/h).

Production - one Sea Lion III (G-EBAH) converted from Sea Lion II by Supermarine Aviation Works, Woolston, Southampton, in 1923.

Colour - believed overall blue hull, silver mainplanes and tail unit, natural aluminium engine nacelle. Black registration letters G-EBAH on white panel on hull sides, and contest number 7 on white panel on nose aft of cockpit and on rudder. A sealion’s ‘face’ was painted in white on the noses of the hull and the two stabilizing floats as was the name Sea Lion III on the hull sides beneath the cockpit.

The old Pemberton Billing Co. and its Supermarine Works at Woolston, near Southampton, were bought by Hubert Scott-Paine in 1916 when Noel Pemberton Billing became a Member of Parliament. It was renamed Supermarine Aviation Works and in 1918 designed and built the Baby, to Air Board specification N.1B, which was one of the very few single-seat fighter flying-boats to be produced during the First World War. The Baby was a biplane with a wing span of 30ft 6 in (9-29 m) and, powered by a 200 hp Hispano-Suiza engine, had a maximum speed of 116 mph (186-6 km/h). Two prototypes, N59-60, were built and flown, but the Baby did not go into quantity production because military requirements changed.

When the Schneider Trophy contests were re-established in 1919 and the first postwar venue was to be Bournemouth, Scott-Paine decided that because of its proximity to the Supermarine factory his company would enter the lists. Since time was short, he obtained one of the Babies, whose forward hull had been modified to reduce spray while on the water as part of a programme to produce a civil Baby to be known as the Sea King. The Hispano-Suiza engine was replaced by a 450 hp Napier Lion twelve-cylinder broad-arrow engine driving a two-blade wooden pusher propeller. Although the redesign of this aircraft was to produce a purely racing machine, it was fully equipped with a bilge pump, sea anchor and mooring equipment. The hull, of Linton Hope design, was of similar construction to that used in the Blackburn Pellet. The single-bay mainplanes and centre section were built up around two spruce spars and wooden ribs which were fabric covered. The four mainplanes were built separately and were rigged without stagger but with dihedral from the flat centre section. Large balanced ailerons were carried on all four mainplanes. The interplane struts were sloped out toward the tops to support the longer-span upper mainplane. Deep, narrow, stabilizing floats were carried beneath the lower mainplanes. The tailplane was mounted on top of the fin and was braced on each side by a pair of steel-tube struts to the hull. A horn-balanced rudder, extended downward to act as a water rudder, was carried on the fin which was covered with wood sheeting. The remainder of the tail unit was of wood and fabric construction. The engine was mounted on four steel-tube struts carrying two ash engine-bearers and supported the upper centre section on four more struts. An oval-shaped radiator was mounted in front of the engine and was enclosed in an aluminium nacelle. The redesign work was entrusted to the young Reginald J. Mitchell, who in later years was to become renowned as the designer of a series of Supermarine racing floatplanes for the Schneider contests and of the Spitfire.

The use of the Lion engine prompted the name Sea Lion for this little racer which received the civil registration G-EALP. The eliminating trials to select the British team were scheduled for 3 September, and while the Sopwith, Fairey, and Avro companies had flown their aircraft by the day before the trial, the Sea Lion’s first flight was delayed by the non-delivery of the propeller - due to a strike at the manufacturers. However, it arrived in time for engine running to begin at 8 p.m. in the evening before the trials; but torrential rain prevented these taking place. On 5 September Sqn Ldr Basil Hobbs, the Supermarine pilot, made the initial flight. Flight trials continued with all four British aircraft, the final decision to include the Sea Lion in place of the Avro entrant being delayed until 9 September when a new propeller gave the Sea Lion an additional five or six miles per hour.

The events of the contest day are recorded elsewhere in this book, but afterwards the Sea Lion was dismantled and its hull was loaned to the Science Museum in London for an exhibition in 1921. Sadly it was broken up some years later when the Museum no longer required it.

Single-seat racing biplane flying-boat. Wood and metal construction. Pilot in open cockpit.

One 450 hp Napier Lion IA twelve-cylinder water-cooled normally-aspirated geared broad-arrow engine driving a 7 ft 10 in (2-38 m) diameter two-blade fixed-pitch wooden propeller.

Span 35 ft (10-66 m); length 26 ft 4 in (8 02 m); height 11 ft 8 in (3-55 m); wing area 380 sq ft (35-3 sq m).

Empty weight 2,000lb (907kg); loaded weight 2,900lb (1,315kg); wing loading 7-63 Ib/sq ft (37-22 kg/sq m).

Maximum speed 147 mph (236-57 km/h).

Production - one Sea Lion I built by conversion of Baby by Supermarine Aviation Works, Woolston, Southampton, in 1919.

Colour - believed to have been dark blue hull and tailplane support struts, with remainder pale blue, grey or silver; engine nacelle natural aluminium; Supermarine in large white capital letters on hull sides forward of mainplanes with small Sea Lion above, white civil registration letters G-EALP on hull sides aft of mainplanes; white contest number 5 on fin.

Supermarine Sea Lion II

Expedience and economy were ever the watchwords of British aircraft manufacturers in the years between the wars and, clearly, were observed by Hubert Scott-Paine at Supermarine when producing aeroplanes for the Schneider contests. Following the use of the N.1B Baby hull in the Sea Lion I, when the decision was made to build an entrant for the 1922 contest the company used an existing airframe on which to base it. During 1919 two civil sporting amphibian versions of the Baby, named Sea King I, had been built but neither had been sold. One of these became the Sea Lion I; in 1921 the second was developed as the Sea King II, an amphibian fighting scout with a single .303-in Lewis machine-gun and provision for light bombs, but when it, too, failed to win orders it was modified to become the Sea Lion II G-EBAH.

The Sea King hull, constructed of circular-section wooden frames with wood skinning, was retained. The bow was modified, which shortened the Sea King hull to 24 ft 9 in (7-54 m) in its Sea Lion II form. A built-on wooden planing bottom and steps, which were divided into watertight compartments, were added. The upper surface was single-skin planking and the whole structure was covered with fabric and doped. The manually-operated wheeled undercarriage and all military equipment and fittings were removed. The Sea King’s mainplanes structure was retained, with four vertical interplane struts replacing the splayed-out struts of the Sea Lion I. The Sea King’s wing area was reduced by introducing a narrower chord in the mainplanes, and their span is believed to have been increased by 1ft 6in (45cm) to reach 32ft (9-75m). The mainplanes, built as four separate sections, were attached to the upper and lower centre sections. They were built up around two spruce spars with wooden ribs, all wire braced and fabric covered. In place of the earlier 300 hp Hispano-Suiza engine, a 450 hp Lion II, loaned by Napier, was installed, which drove a four-blade wooden pusher propeller of about 8 ft 6 in (2-59 m) diameter. To offset the increased torque and maintain stability, the fin area above the tailplane was enlarged by forward curvature of the leading edge. Because the engine was mounted high between the wings and produced a high thrust-line resulting in a pitching moment, the tailplane had a reverse camber to counteract this. Fuel was supplied to the engine by a high-pressure air system with all fuel lines being kept short and run as clear of the hull as possible.

The earlier Sea King II had not only proved itself capable of aerobatics - Henri Biard, Supermarine’s test pilot had rolled and spun the aircraft - but it had also been very stable at all speeds. These characteristics were inherited by the Sea Lion II which was a very tractable aeroplane.

The 1922 Schneider contest was scheduled to take place in Naples during the latter part of August, but the Italians decided to advance the date by some ten days. Unfortunately, the Sea Lion II was still incomplete when news of the change was received by the Royal Aero Club, and so the work was pressed ahead with all speed. When the day came for preliminary engine running the Lion started almost immediately and it was decided to make a preliminary test flight. With Biard aboard, the Sea Lion II got airborne very easily after a short take-off run - but suddenly, when it was some 200 ft over rows of luffing cranes and the masts of ships in Southampton Docks, the Lion engine stopped. Biard managed to pick out a stretch of clear water and glided down to alight safely. The Sea Lion was towed back to Woolston where a fault in the fuel system was diagnosed and corrected. But a precious day was used up.

The following evening Biard again flew the Sea Lion and, finding all was going well, opened the throttle wide to achieve a speed in excess of 150mph, faster than any British flying-boat had then flown. There followed several days while final modifications were made to the airframe and flying time was built up, then the Sea Lion was dismantled and crated for its journey by sea to Naples.

With the Sea Lion re-assembled, Biard and the Supermarine team launched a cloak-and-dagger operation, first to find out the strength of the French and Italian opposition, and then to conceal from their prying eyes and stop watches the capabilities of the British flying-boat. Accordingly, Biard confined his full-throttle runs to an area well clear of Naples Bay, and made sure that his practice circuits always included some cautious turns around the pylons. This plan worked so well that the Italians publicly proclaimed the inferiority of the Sea Lion when compared with the Macchi M.17 and Savoia S.51. But there was almost disaster, when he flew too close to Vesuvius in an attempt to look down into its crater, and a strong thermal suddenly lifted the Sea Lion some 2,000ft above its original flight path.

In the contest Biard’s tactical flying, plus the Sea Lion’s speed, brought the Trophy to Britain; additionally they established world closed-circuit speed, duration and distance records, the first to be recognized for seaplanes.

Soon after its return to the Supermarine factory, the Sea Lion II G-EBAH was bought by the Air Ministry for development flying work, but it has not been established whether it was moved to Felixstowe; it was not, however, removed from the Civil Aircraft Register.

There was also a plan to fly G-EBAH in the 1922 King’s Cup air race. That a flying-boat should take part in a race flown entirely over land was a tribute to the reliability of the Lion engine. A report in Flight of 7 September records that 'at the moment of going to press we learn this machine will not start'. There were no other references to the Sea Lion in reports of the race.

Single-seat racing biplane flying-boat. Wood and metal construction. Pilot in open cockpit.

One 450 hp Napier Lion II twelve-cylinder water-cooled normally-aspirated geared broad-arrow engine driving an 8 ft 6 in (2-59 m) diameter four-blade fixed-pitch wooden pusher propeller. Fuel: 55 gal (250 litres).

Span 32 ft (9-75m); length 24ft 9in (7-54m); height 12ft (3-65m) approx; wing area 384 sq ft (35 -67 sq m).

Empty weight 2,115lb (959kg); loaded weight 2.850lb (1,292kg); wing loading 7-42 Ib/sqft (36-22 kg/sq m).

Maximum speed 160mph (257-49 km/h).

Production - one Sea Lion II (G-EBAH) converted from Sea King II by Supermarine Aviation Works, Southampton, in 1922.

Colour - believed to have been overall blue hull, interplane and tailplane support struts; cream or white mainplanes and tailplane; white registration G-EBAH on rear hull sides and national letter G on rudder, black contest number 14 on white panel on hull sides aft of cockpit

Supermarine Sea Lion III

For the 1923 Schneider contest the Air Ministry decided that the old Sea Lion II G-EBAH should participate again. Reginald Mitchell at Supermarine rapidly produced drawings to initiate a general modification programme aimed at cleaning up the hull and increasing its fineness ratio. As a result the hull length was increased by 2 ft 9 in (83 cm). A new planing bottom was attached to the hull and the bow section refined; in addition the wing span was reduced by 4 ft (1-21 m), and the area of the fin and rudder was increased by making them taller.

During the flight-test programme the shoe-shaped floats were removed and oval-section stabilizing floats, with pairs of small hydrovanes at their forward end, were mounted on short struts and wire braced to the underside of the lower mainplanes near the tips. For the first time on a Sea Lion, a small glass windscreen was mounted in front of the open cockpit.

Power for the Sea Lion III came from a 525 hp Napier Lion III which drove a four-blade wooden pusher propeller. The engine, in its aluminium nacelle with a circular-section radiator housed in a long-chord tubular cowling, was supported on a pair of N-struts; the fuel lines were carried up inside a streamlined radiator support strut from the hull fuel tank to the engine.

A strange feature of this cleaning-up process was that the engine starting handle was permanently fixed to the power unit and protruded from the port side of the nacelle; moreover, the tailplane had no less than eight wire-braced support struts, and the original combined water-rudder/tailskid was retained.

In the contest, although Biard and the Sea Lion III returned a speed some 12 mph faster than that at which they had won the previous year’s event, they were outclassed by the Curtiss CR-3s and could only take third place.

During the first few weeks following the contest, Biard flew the Sea Lion III on some further flight trials; then during the first week of December it was taken on RAF charge, serialled N170 and moved to Felixstowe.

Single-seat racing biplane flying-boat. Wood and metal construction. Pilot in open cockpit.

One 525 hp Napier Lion III twelve-cylinder water-cooled normally-aspirated geared broad-arrow engine driving an 8 ft 8 in (2-64 m) diameter four-blade fixed-pitch wooden pusher propeller. Fuel: 60 gal (272 litres).

Span 28ft (8-53m); length 28ft (8-53m); wing area 360sq ft (33-44sq m).

Empty weight 2,400 lb (1,088 kg); loaded weight 3,275 lb (1,485 kg); wing loading 9-09 lb/ sq ft (44-4 kg/sq m).

Maximum speed 175 mph (281-61 km/h); alighting speed 55 mph (88-51 km/h).

Production - one Sea Lion III (G-EBAH) converted from Sea Lion II by Supermarine Aviation Works, Woolston, Southampton, in 1923.

Colour - believed overall blue hull, silver mainplanes and tail unit, natural aluminium engine nacelle. Black registration letters G-EBAH on white panel on hull sides, and contest number 7 on white panel on nose aft of cockpit and on rudder. A sealion’s ‘face’ was painted in white on the noses of the hull and the two stabilizing floats as was the name Sea Lion III on the hull sides beneath the cockpit.

The Supermarine launch Tiddlywinks takes in tow the Sea Lion I, G-EALP, as it is launched from the company’s slipway at Woolston. The uncowled Napier Lion engine, laminated mahogany propeller, and spray dams at the base of the inboard interplane struts, are seen clearly.

This view of the Supermarine Sea Lion II in which Henri Biard won the contest in 1922 shows clearly the hull form.

Henri Biard taxies the Supermarine Sea Lion III G-EBAH past the moored Blackburn Pellet during practice flying. A feature of this Sea Lion variant was the large fin and rudder area above the tailplane.

This close-up view of the Sea Lion III G-EBAH shows details of the long radiator air intake, the engine mounting struts, and fixed starting handle. What appears to be an additional ‘lash-up’ pitot head is carried on the starboard outer interplane struts.

This painting by Leslie Carr shows the Supermarine Sea Lion II passing a balloon marking the 1922 course.

Macchi M.7

The Societa Anonima Nieuport-Macchi, formed by Giulio Macchi in 1912 at Varese, a small Italian town near the Swiss border, undertook the manufacture of Nieuport designs until 1919 when its own designs of landplanes began to enter production. The Macchi flying-boat and seaplane tradition began in a curious manner during hostilities between Italy and Austria in 1915. When the Austrian Lohner L.I flying-boat L.40 was forced down, virtually undamaged, on the water near Porto Corsini seaplane base at Rimini, it was immediately taken to Varese, and Macchi was instructed to build a copy. The Macchi L.1 was in the air for the first time only a little over a month later, and it formed the basis of a number of successful Macchi flying-boats, among them the M.5 single-seat fighter design of Felice Buzio.

An experimental single-seater, the M.6, led on to the M.7, which was the first design of Alessandro Tonini, the Macchi company’s chief engineer. Powered by a 260 hp Isotta-Fraschini six-cylinder water-cooled inline engine, it had a maximum speed of about 210 km/h (130 mph). While the earlier Macchi fighter flying-boat designs had incorporated vee interplane struts, inherited from the classic Nieuport biplane fighters, the M.7 had the more conventional paired interplane struts and a wingspan reduced to 11-88m (39ft).

The slim, single-step, rectangular-section hull was built up from an ash framework with a spruce skin, the fin being built integral with the hull. The slightly swept unequal-span, single-bay, unstaggered biplane mainplanes of markedly curved aerofoil section had ash spars with spruce ribs, all fabric covered. The upper centre section above the engine was supported on wooden N-struts. Ailerons were carried only on the upper mainplane and were mounted at the extreme tips. The pairs of interplane struts were splayed out at the top when viewed both from front and sides, and the whole structure was braced by the conventional wires. The engine was carried above the hull on a pair of N-struts which also supported the upper centre-section struts. It was uncowled, with a large radiator mounted directly in front of the two banks of cylinders, and a smaller oil cooler was in a bulged fairing beneath the radiator. The tail unit consisted of a fabric-covered wooden-structured tailplane which was carried half-way up the quite tall and narrow-chord fin and was strut-braced to the hull. The rudder was only a little more than half the height of the fin and extended very little below the tailplane. Two square-section stabilizing floats were carried on struts under the lower wing. The open cockpit was directly below the water radiator, was protected by a small curved windscreen, and had a faired headrest for the pilot.

Determined to win the 1921 Schneider Trophy contest in Venice, and to take another step toward permanent possession of it, Italy gathered sixteen flying-boats for a series of national elimination trials to select a team. Among them were five M.7s flown variously by de Briganti, Buonsembiante, Corgnolino, Falaschi and de Sio, and with varying fortunes. De Briganti and Corgnolino won places in the Italian team, the M.7s of Buonsembiante and de Sio were withdrawn from the trials, and Falaschi crashed before they got under way.

Having won the 1921 contest, largely through the failure of the other entries either before or during the event, an M.7bis, I-BAFV, was entered for the 1922 contest when one of the selected team aircraft, the Savoia S.50, crashed. It took fourth, and last, place at an average speed of 199-607km/h (124-029mph).

Production of later versions of this tough little flying-boat fighter continued almost throughout the 1920s. One variant, the M.7ter, equipped all of the Italian squadriglie di caccia marittima (seaplane fighter squadrons) until 1929, with 163 Squadriglia retaining its M.7s for a further year.

Single-seat racing biplane flying-boat. Wood construction with wood skinning and fabric covering. Pilot in open cockpit.

One 260 hp Isotta-Fraschini Semi-Asso six-cylinder water-cooled inline engine driving a 2-2 m (7 ft 3 in) diameter two-blade wooden pusher propeller. The 1922 variant had a four-blade propeller.

Span 9-95m (32ft 8 in); length 8-13m (26ft 61 in); height 2-97m (9ft 9in); wing area 23-8sqm (256-18sqft).

Empty weight 780kg (1,719lb); loaded weight 1,080kg (2,381lb); wing loading 45-37 kg/sqm (9-29 Ib/sq ft).

Maximum speed 209km/h (130mph); stalling speed 100km/h (62mph).

Production - five refined versions of the Macchi M.7 military flying-boat were prepared for the 1921 Schneider Trophy contest by Societa Anonima Macchi at Varese. At least one, the M.7bis, had its wings clipped by approximately 2-2 m (7 ft 3 in). It is not certain whether any more M.7s were prepared for racing, but one aircraft, registered I-BAFV, flew in the 1922 contest.

Colour - few details of colour schemes can be found but it is believed that I-BAFV had a pale green hull and silver mainplanes and tail unit. The registration letters were black, carried on a white rectangle on the hull sides aft of the mainplanes, and the contest number 10 was similarly carried on a white rectangle on the hull sides just forward of the cockpit. The name Macchi M.7 was carried on both sides of the hull nose. It is recorded that in common with all the other aircraft participating in the 1921 Italian team selection trials, the M.7s carried on the hull sides forward, a variety of coloured identity ‘patches’ of different shape, including yellow and red rectangles and a green circle or star.

The Societa Anonima Nieuport-Macchi, formed by Giulio Macchi in 1912 at Varese, a small Italian town near the Swiss border, undertook the manufacture of Nieuport designs until 1919 when its own designs of landplanes began to enter production. The Macchi flying-boat and seaplane tradition began in a curious manner during hostilities between Italy and Austria in 1915. When the Austrian Lohner L.I flying-boat L.40 was forced down, virtually undamaged, on the water near Porto Corsini seaplane base at Rimini, it was immediately taken to Varese, and Macchi was instructed to build a copy. The Macchi L.1 was in the air for the first time only a little over a month later, and it formed the basis of a number of successful Macchi flying-boats, among them the M.5 single-seat fighter design of Felice Buzio.

An experimental single-seater, the M.6, led on to the M.7, which was the first design of Alessandro Tonini, the Macchi company’s chief engineer. Powered by a 260 hp Isotta-Fraschini six-cylinder water-cooled inline engine, it had a maximum speed of about 210 km/h (130 mph). While the earlier Macchi fighter flying-boat designs had incorporated vee interplane struts, inherited from the classic Nieuport biplane fighters, the M.7 had the more conventional paired interplane struts and a wingspan reduced to 11-88m (39ft).

The slim, single-step, rectangular-section hull was built up from an ash framework with a spruce skin, the fin being built integral with the hull. The slightly swept unequal-span, single-bay, unstaggered biplane mainplanes of markedly curved aerofoil section had ash spars with spruce ribs, all fabric covered. The upper centre section above the engine was supported on wooden N-struts. Ailerons were carried only on the upper mainplane and were mounted at the extreme tips. The pairs of interplane struts were splayed out at the top when viewed both from front and sides, and the whole structure was braced by the conventional wires. The engine was carried above the hull on a pair of N-struts which also supported the upper centre-section struts. It was uncowled, with a large radiator mounted directly in front of the two banks of cylinders, and a smaller oil cooler was in a bulged fairing beneath the radiator. The tail unit consisted of a fabric-covered wooden-structured tailplane which was carried half-way up the quite tall and narrow-chord fin and was strut-braced to the hull. The rudder was only a little more than half the height of the fin and extended very little below the tailplane. Two square-section stabilizing floats were carried on struts under the lower wing. The open cockpit was directly below the water radiator, was protected by a small curved windscreen, and had a faired headrest for the pilot.

Determined to win the 1921 Schneider Trophy contest in Venice, and to take another step toward permanent possession of it, Italy gathered sixteen flying-boats for a series of national elimination trials to select a team. Among them were five M.7s flown variously by de Briganti, Buonsembiante, Corgnolino, Falaschi and de Sio, and with varying fortunes. De Briganti and Corgnolino won places in the Italian team, the M.7s of Buonsembiante and de Sio were withdrawn from the trials, and Falaschi crashed before they got under way.

Having won the 1921 contest, largely through the failure of the other entries either before or during the event, an M.7bis, I-BAFV, was entered for the 1922 contest when one of the selected team aircraft, the Savoia S.50, crashed. It took fourth, and last, place at an average speed of 199-607km/h (124-029mph).

Production of later versions of this tough little flying-boat fighter continued almost throughout the 1920s. One variant, the M.7ter, equipped all of the Italian squadriglie di caccia marittima (seaplane fighter squadrons) until 1929, with 163 Squadriglia retaining its M.7s for a further year.

Single-seat racing biplane flying-boat. Wood construction with wood skinning and fabric covering. Pilot in open cockpit.

One 260 hp Isotta-Fraschini Semi-Asso six-cylinder water-cooled inline engine driving a 2-2 m (7 ft 3 in) diameter two-blade wooden pusher propeller. The 1922 variant had a four-blade propeller.

Span 9-95m (32ft 8 in); length 8-13m (26ft 61 in); height 2-97m (9ft 9in); wing area 23-8sqm (256-18sqft).

Empty weight 780kg (1,719lb); loaded weight 1,080kg (2,381lb); wing loading 45-37 kg/sqm (9-29 Ib/sq ft).

Maximum speed 209km/h (130mph); stalling speed 100km/h (62mph).

Production - five refined versions of the Macchi M.7 military flying-boat were prepared for the 1921 Schneider Trophy contest by Societa Anonima Macchi at Varese. At least one, the M.7bis, had its wings clipped by approximately 2-2 m (7 ft 3 in). It is not certain whether any more M.7s were prepared for racing, but one aircraft, registered I-BAFV, flew in the 1922 contest.

Colour - few details of colour schemes can be found but it is believed that I-BAFV had a pale green hull and silver mainplanes and tail unit. The registration letters were black, carried on a white rectangle on the hull sides aft of the mainplanes, and the contest number 10 was similarly carried on a white rectangle on the hull sides just forward of the cockpit. The name Macchi M.7 was carried on both sides of the hull nose. It is recorded that in common with all the other aircraft participating in the 1921 Italian team selection trials, the M.7s carried on the hull sides forward, a variety of coloured identity ‘patches’ of different shape, including yellow and red rectangles and a green circle or star.

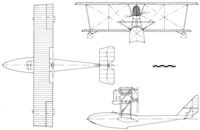

Savoia S.13

As a maritime nation it was only natural that Italy would become a very active participant in the Schneider Trophy contests. Its first entrant was the S.13, a modified version of a fast little two-seat bombing and reconnaissance two-bay biplane flying-boat. In only two weeks it was converted to a single-seater, the mainplanes were clipped for racing and converted to single-bay configuration, and the Isotta-Fraschini engine was tuned to produce some ten additional horse power.

The single-step hull was built up from wooden formers and stringers clad with marine plywood. The strut-braced tailplane was mounted on the fin which was an integral part of the hull structure. The wooden elevators and rudder were fabric covered. The straight mainplanes were of conventional two-spar wooden construction with fabricated wooden ribs and fabric covered; the ailerons, fitted only on the upper mainplane, were of similar construction; two small stabilizing floats were strut-mounted under the lower mainplane; and the whole structure was wire-braced. The engine was mounted above the hull on two N-struts, and two other N-struts supported the upper mainplane. The radiator was carried forward of the engine with an oil cooler below it. All flying-control surfaces were cable-operated. The front and lower portion of the engine was cowled with aluminium panels leaving the rear top section uncowled. The engine drove a four-blade wooden pusher propeller in place of the two-blade unit of the military S.13.

When the modifications were completed, the aircraft was dismantled, crated and transported overland by rail and by ship to Britain. Only a few practice flights were possible before the contest in which the S.13, flown by Sgt Guido Jannello, was the only aircraft to complete the required number of laps, but was flown on an incorrect course.

Single-engine racing biplane flying-boat. All-wood construction with wood and fabric covering. Pilot in open cockpit.

One 250hp Isotta-Fraschini Asso 200 six-cylinder water-cooled, direct-drive normally aspirated inline engine driving a 2-1 m (6 ft 11 in) diameter four-blade fixed-pitch wooden propeller.

Span 8-1 m (26 ft 7 in) (upper), 7-28 m (23 ft 11 in) (lower); length 8-3 m (27 ft 3 in); height 3-05m (10ft); wing area 19-6sq m (210-97sq ft).

Empty weight 730kg (1,609 lb); loaded weight 940kg (2,072lb); wing loading 47-96 kg/sq m (9-82lb/sq ft).

Maximum speed 243 km/h (151 mph).

Production - one S.13 converted to single-seat racing configuration by Societa Idrovolanti Alta Italia in 1919.

Colour - overall red with white bottom to hull and stabilizing floats; natural metal engine cowling; green, white and red national stripes on fin and rudder; white-edged black contest number 7 on rudder; blue and white pennant with name Savoia on hull nose.

Savoia S.12bis

Perhaps the S.12 came nearer to Jacques Schneider’s ideals than any other aircraft which participated in the contests. His aim had been to promote the creation of seaworthy long-distance load-carrying maritime aircraft, and the S.12, basically, was all of these, being developed from a two-seat bomber type which had good range and load-carrying characteristics. As the only entry in the 1920 contest to attempt the navigability trials in appalling weather, through which it came with flying colours, this sturdy flying-boat proved its seaworthiness.

In appearance, it was almost identical to the standard S.13 before its conversion to a racing aircraft. The long slender hull was of all-wood construction with a tall curved-back fin and rudder carrying a strut-braced tailplane. A full-width windscreen protected the open cockpit in front of the mainplane. On the standard S.12 the tailplane span was about 4-8 m (16ft) but this was reduced to 2-9 m (9ft 6 in) on the S.12bis racing variant.

The 15-07 m (49 ft 5 in) span mainplanes of the military original also had been reduced, by more than 3 m. A wire-braced two-bay structure, the two-spar mainplanes had plywood ribs giving a markedly curved aerofoil section. Ailerons were fitted only on the upper mainplane and, like the elevators and rudder, were fabric covered. The inboard inter-plane struts were vertical but the outboard struts were canted outward to their upper ends. Two square-section stabilizing floats were strut mounted beneath the lower mainplanes. The 550 hp Ansaldo-San Giorgio twelve-cylinder water-cooled pusher engine was mounted on a pair of N-struts between the mainplanes. A large radiator and integral oil cooler was fitted in front of the engine, the lower portion of which was cowled leaving the top exposed. A second, lighter, pair of N-struts supported the upper mainplane.

Mechanical troubles, transport difficulties and bad weather eliminated all but the S.12 from the list of entries for the 1920 contest at Venice. Having completed the pre-contest trials, Lieut Luigi Bologna had only to fly it over the course to win, which he did at an average of 172-561 km/h (107-224 mph) and secured the Trophy for Italy.

Single-engined racing biplane flying-boat. All-wood construction with wood and fabric covering. Pilot in open cockpit.

One 550 hp Ansaldo-San Giorgio 4E-29 twelve-cylinder water-cooled direct-drive normally-aspirated vee engine driving an Ansaldo four-blade fixed-pitch wooden pusher propeller of about 1-98m (6ft 6in) diameter. Fuel: about 270 litres (60 gal).

Span 11-72m (38ft 5 1/2 in) (upper); length 10m (32ft 10in); height 3-8 m (12 ft 5 1/2 in); wing area 46-52 sqm (500-74 sqft).

Empty weight 1,560kg (3,438 lb); loaded weight 2.360kg (5,202lb); wing loading 50-73 kg/sqm (10-38 Ib/sq ft).

Maximum speed 222km/h (138mph).

Production - believed to be only one S.12bis produced (serialled 3011) by Societa Idrovolanti Alta Italia at Sesto Calende, Italy, in 1920.

Colour - unknown. Carried contest number 7 on side of hull nose and on rudder, S.12 on hull nose and Savoia in large script letters down length of hull.

As a maritime nation it was only natural that Italy would become a very active participant in the Schneider Trophy contests. Its first entrant was the S.13, a modified version of a fast little two-seat bombing and reconnaissance two-bay biplane flying-boat. In only two weeks it was converted to a single-seater, the mainplanes were clipped for racing and converted to single-bay configuration, and the Isotta-Fraschini engine was tuned to produce some ten additional horse power.