G.Duval British Flying-Boats and Amphibians 1909-1952 (Putnam)

Porte/Felixstowe Fury (1918)

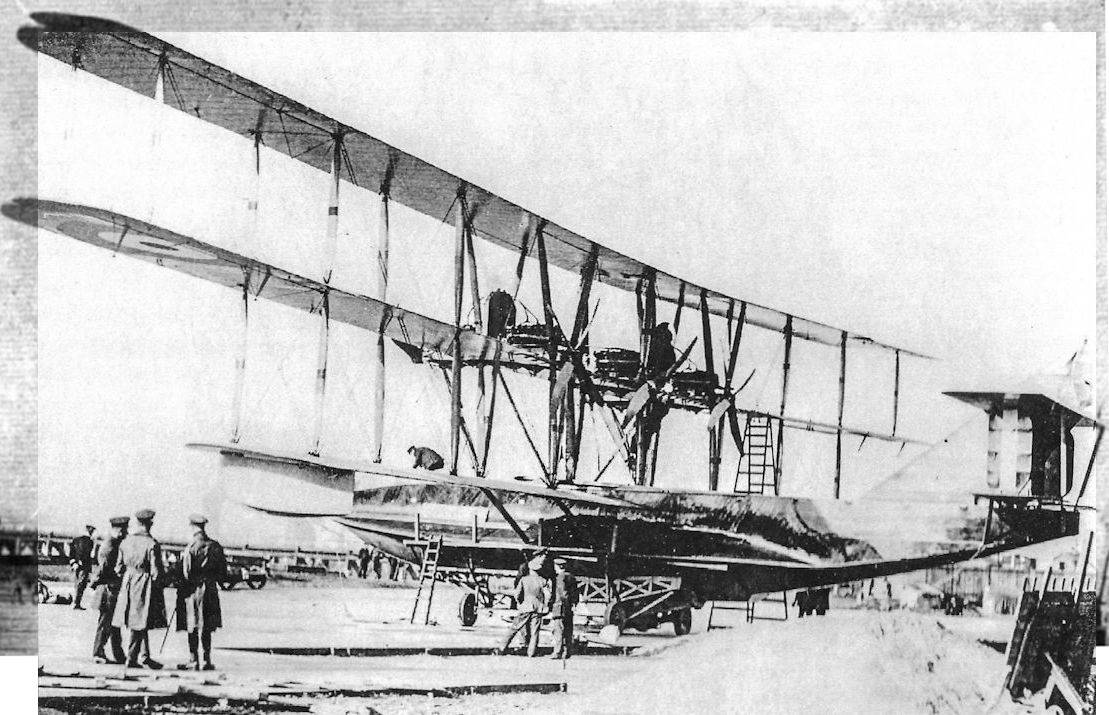

John Porte’s last Felixstowe production was a huge triplane flying-boat, the largest British machine of its day, powered by no fewer than five 334 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VII engines. The Fury was probably inspired by a large Curtiss triplane flying-boat which had been assembled and flown at Felixstowe in 1916, the Curtiss-Wanamaker, serialled No. 3073. This machine was the first delivered of an order for twenty, but even with its original four 250 h.p. Curtiss engines replaced by Rolls-Royce power units, official tests showed that the performance did not measure up to requirements and the order was cancelled. At the time, Porte had little opportunity and insufficient resources to deal with the redesign of the Curtiss-Wanamaker, but it is certain that as an advocate of the large flying-boat he did not forget it, and when the Fury appeared in 1918 several features of the Curtiss machine were embodied. Known to all at Felixstowe as the Porte Super Baby, the Fury was planned for an engine installation of three of the new 600 h.p. Rolls-Royce Condors but was completed before the Condor became available, so the engine mountings were modified to take five Rolls-Royce Eagles arranged as a central pusher flanked by two outboard pairs of pusher and tractor. The hull, basically employing a similar construction and profile to the other Felixstowe boats and 60 feet in length, was regarded as the best of all the Porte hulls. The top and central mainplanes were of equal span, the latter carrying the engines, while the lower mainplane was one bay shorter. The tail unit resembled that of the Curtiss-Wanamaker, with a biplane tailplane fitted with twin rudders mounted upon a central fin. The Fury design incorporated power-operated controls, using servo-motors, and it was almost certainly the first aircraft in the world to fly with these in operation although actually the Fury proved to be remarkably light on all controls and so the weighty servos were dispensed with. The machine’s designed loaded weight was 24,000 pounds, this being gradually increased during testing without adverse effect upon take-off or seaworthiness until it reached the figure of 33,000 pounds, at which enormous weight Porte himself coaxed the great machine into the air from Harwich Harbour. On another occasion, Major T. D. Hallam, d.s.C., flew the Fury with 24 passengers, fuel for seven hours, and 5,000 pounds of ballast. The tail unit was later modified to a more conventional assembly of biplane layout with triple rudders between the tailplanes, and the hull tested in model form in the Froude Tank at the National Physical Laboratory, some of the recommended modifications resulting from this testing being applied to the full-sized aircraft. Never used operationally, the Fury continued experimental flying after the Armistice, powered in its final form by five Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII engines of 365 h.p. each. A few months after Porte and Rennie were demobilised, the Fury stalled and crashed on take-off, possibly due to incorrect loading, the pilot and two crew members losing their lives.

In August 1919, Porte joined the Gosport Aviation Co. Ltd., as chief designer, to work with an old friend, Herman Volk, who had become manager of the company. A number of designs was produced but none was built due to the post-war slump in orders. In October 1919 John Porte died at Brighton. He was thirty-five years old.

SPECIFICATION

Power Plant: Five 334 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VII, or five 365 h.p. Rolls- Royce Eagle VIII

Span: 123 feet

Length: 63 feet 2 inches

Weight Loaded: 25,253 pounds (medium), 33,000 pounds (max. test)

Total Area: 3,108 square feet

Max. Speed: 97 m.p.h. at 2,000 feet

Endurance: 7 hours (medium). In excess of 12 hours with max. fuel load

Armament: Four Lewis guns and heavy bomb load

Показать полностью

J.Bruce British Aeroplanes 1914-1918 (Putnam)

Felixstowe Fury

THE Felixstowe Fury of 1918 was John Porte’s most ambitious flying boat design. It was a very large triplane powered by five Rolls-Royce Eagle VII engines, and as soon as its proportions became apparent it was popularly dubbed the Porte Super Baby. Its official name was the Felixstowe Fury, but in its day it was better known by its unofficial title.

Into the Fury was built all the experience which had been gained with the F.1, F.2 and F.3 hulls, and the Fury hull was regarded as the best of all the Felixstowe hulls built on the Porte principle. It had the same basic structure of four longerons built into a cross-braced box girder, and was planked diagonally with two skins of cedar over an inner longitudinal skin. The keelson and floors were of built-up lattice girder construction, and the bottom was covered with three layers of cedar and mahogany half an inch thick. Great pains were taken to avoid the splitting which occurred at the joints of earlier hulls: the diagonal planking was steamed and bent round the chines and fin tops in order to eliminate the troublesome joints. The vee-bottom of the hull was slightly concave, whereas the F-boats had straight sections of 150° included angle.

The Fury was originally designed for three Rolls-Royce Condor engines of 600 h.p. each, but these were not available when the boat was nearing completion. The five Eagles were therefore substituted, and were installed as two tractor and three pusher units. The outboard pusher engines drove four-bladed airscrews, since they had to work in the slipstream of the tractor airscrews. With these engines the Fury was rather underpowered, but still had a remarkably good performance.

The triplane wings spanned 123 feet. Balanced ailerons were fitted to the top and middle wings, which were of equal span and one bay longer than the bottom wings. The middle wing carried the engines and had a long cut-out in its trailing edge to accommodate the three pusher airscrews.

One of the most interesting features of the Fury was the advanced thinking displayed in the design of its control system. All control surfaces were fitted with servo-motors, for it was thought that in certain conditions their operation might be beyond the physical capability of the pilot. Moreover, the upper and lower elevators did not move synchronously: the lower elevator was, in effect, a trimming surface, and was operated separately by means of a long lever on a quadrant actuated by the main elevator control rod. On test, the Fury proved to be remarkably light on the controls - lighter, in fact, than the smaller F-boats - and the servo-motors were removed, for their use did not warrant the additional weight.

The tail-unit underwent modification. As originally built, the Fury had a large central fin of unusual appearance: both leading and trailing edges of this surface sloped upwards and rearwards; and at its upper extremity, wholly above the tailplane, there was a small balanced rudder. Two outboard rudders were also fitted between the tailplanes. Later, the vertical tail was revised to consist of three fins and rudders mounted wholly between the tailplanes.� The Fury was designed to fly at an all-up weight of 24,000 lb, but in practice it was found that at 28,000 lb launching, seaworthiness and take-off characteristics were still superior to those of the earlier F-boats. Loading tests were continued to greater weights, and Colonel Porte took off in the Fury in Harwich harbour at a weight of 33,000 lb.

During its tests the machine was flown by several experienced flying boat pilots, including Majors Arthur Cooper, T. D. Hallam, B. D. Hobbs and Wright, in addition to Colonel (as he later was) Porte himself. Major Hallam has recorded that he flew the Fury with a load of twenty-four passengers, fuel for seven hours and 5,000 lb of sand ballast.

Some time after the Fury had been completed, in September, 1918, a model of the hull was sent to the National Physical Laboratory for testing in the Froude tank. These tests indicated that certain improvements could be made in the hull and would improve its water performance. Some of the suggested modifications were embodied in the hull. In the course of experiments conducted to investigate the effect of steps on running characteristics the machine had successively one, two and three steps, but finally reverted to two.

The Felixstowe Fury saw no active service, but continued to be flown occasionally for experimental purposes after the Armistice. At one time there was a plan to fly it across the Atlantic. This flight, whether made from east to west or from west to east, would have been well within the Fury’s capacity, for it had tankage for the enormous quantity of 1,500 gallons of fuel. The Atlantic project was abandoned on the score of expense.

Several months after Colonel Porte and Major Rennie were demobilised the Fury was wrecked. The pilot was Major Ronald Moon. In the absence of Porte and Rennie no technical officer was in charge of flying, and it seems possible that the boat’s load was not distributed with any consideration for the position of the centre of gravity. Major Moon apparently attempted to take off before the machine had reached its minimum safe flying speed and, in the absence of any reserve of power, the boat stalled. The bottom caved in at the impact.

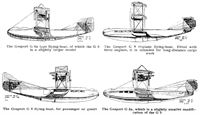

In August, 1919, Wing Commander Porte joined the Gosport Aviation Co., Ltd., and designed a series of flying boats for that firm The largest of these was the Gosport G.9, a triplane powered by three 600 h.p. Rolls-Royce Condors and intended for the transport of mails and freight; there were to be seats for ten passengers. The machine was obviously the Fury design modified for commercial use, but Porte succumbed to his disability in October, 1919, and the G.9 was never built.

SPECIFICATION

Manufacturers: Seaplane Experimental Station, Felixstowe.

Power: Five 334 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VII; five 345 h.p. (low-compression) Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII.

Dimensions: Span: 123 ft. Length: 63 ft 2 in. Height: 27 ft 6 in. Maximum beam: 12 ft 6in. Chord: 10 ft. Gap: 8 ft 6 in. Stagger: nil. Dihedral: upper and middle wings 2°, bottom wings nil.

Areas: Wings: 3,108 sq ft. Tailplane and elevators: 378 sq ft. Fins: 86 sq ft. Rudders: 58 sq ft.

Weights (lb) and Performance:

Flight condition Light load Medium load

No. of Trial Report N.M.250

Date of Trial Report June, 1919

Types of airscrew used on trial 8680, 8701 and 8691

Weight empty 18,563 18,563

Military load 300 300

Crew 720 1,260

Fuel and oil 2,300 5,130

Weight loaded 21,883 25,253

Maximum speed (m.p.h.) at

2,000 ft 97-5 97

6,500 ft 94-5 93

10,000 ft 91 89-5

m. s. m. s.

Climb to

2,000 ft 2 50 3 40

6,500 ft 10 00 14 00

10,000 ft 19 05 28 20

Service ceiling (feet) 14,800 12,000

Tankage: Petrol 1,500 gallons. Oil 100 gallons.

Armament: There was provision for four machine-guns and a substantial load of bombs.

Показать полностью

C.Owers The Fighting America Flying Boats of WWI Vol.2 (A Centennial Perspective on Great War Airplanes 23)

7. The Felixstowe Fury

Another type of flying boat, the largest flown to date, is the Felixstowe Triplane called the “Fury”. It is built along the lines of the H-16 construction, having internal wiring with diagonal struts and longerons. ...In the first flight the boat left the water very easily and attained a speed of 94 knots (107 miles per hour) at sea level. No one was carried in the rear tail cockpit as this is to be washed out in favour of fighting cockpits on the wings. The empennage is being rebuilt along standard lines. The tail setting, in spite of the fact that, in the first flights was found to be neutral, is now being reset to two degrees incidence as originally intended. This will permit an overload in the tail. The landing speed was about 40 knots (46 miles per hour) which permitted the boat to land safely with no porpoising. The ailerons are balanced. Servo motors are attached to ailerons and rudder.

On another trial last Saturday (November 23, 1918) this boat flew with total load of 30,000 lbs, making about 9 lbs., per square foot loading. It attained a speed of 100 miles an hour. The landings were made very softly at 55 miles per hour.

Until the minor deficiencies of this boat are corrected and official trials made, no hard and fast conclusions are to be accepted. It has five 350 H.P. Rolls Royce engines with thrust lines in plane of middle wing. Two tractor and three pushers.

This quotation is taken from a Memorandum by the USN on the latest types of British flying boats and describes the last of the series of Felixstowe flying boats, the largest designed by John Porte and his most ambitious - the Felixstowe Fury.

The Fury, was

designed as an experiment in seaworthiness.

The America might serve for inland waters, the F boats were effective over the narrow seas when operating from a good harbour and well equipped base, but something was needed which could be landed in a heavy sea with safety and also rise again.

It would need to be large so as to be little effected by moderate waves, strong to stand considerable rough usage, and exceptionally good at landing and getting off. It should be able to stay away from its base for days...

Getting off must be done rapidly, the long run usual, in smooth water could not be allowed and a “get off’ in a series of leaps, would have to be reckoned on. To reduce the number of leaps, is highly important. The loading laid down was 13 Ibs/H.P., and not more than 8 lbs/sq. ft.

The 320th Meeting of the Progress and Allocation Committee on 10 April 1918, considered the work being carried out at the Felixstowe Air Station as follows:

Cmdr Porte is undertaking a design on the same lines as the N.4 but in order to get the initial experiment carried out as quickly as possible “he is pressing ahead with the design of a machine fitted with five R.R. Eagle VII engines in order that the experiment should not be delayed by waiting for the higher powered 800 H.P. BHP or R.R. engines.

The primary object was to obtain a seaworthy flying boat that was capable of alighting and rise from the water under average North Sea conditions. With this end in view a basis of low weight per HP was taken and the question of military load, fuel, bombs, etc., was considered to be of secondary importance. It was estimated that the following load and performance would be obtained:

Crew of five.

Fuel 600 gals for 514 hours at 93 knots full speed at sea level, or 8 hours estimated at cruising speed.

Bombs 2 x 500-lb

Armament 10 Lewis guns and 650 rounds per gun. W/T Pat. 54A

Service ceiling was estimated to be 14,000 feet but Porte notes that this was more or less conjecture as there was not sufficient data for a triplane of this type to rely on.

The development of this large flying boat was recommended as it would provide private firms with assistance in developing large flying boats due to Felixstowe’s previous experience in building and operating flying boats under actual service conditions. “As soon as the private firms are educated up to the Felixstowe standard it will be possible to give up Government designing and rely on the firms to continue the development.”

Porte had built a three-engined flying boat in 1916 that was known as the Porte Baby, so it was no surprise that the new project became the Porte Super Baby or P.S.B. in official reports.

In March 1918 Porte informed the RNAS Design branch that he had GA drawings of a new machine. On this letter the note “Is this the F.5 or a new design?” was answered with “new design.” In reply the question was put as to the stressing of the machine, “Would it not be as well to get that checked over up here as soon as possible.” The P.S.B. was already well under construction at Felixstowe at this time as a request for five radiators, three large and two small, was sent the same month as they were “urgently needed in connection with the experimental Flying Boat now under construction.” The engine arrangement was for one pusher on the centre line and either side two engines back to back. It is interesting that this “machine has not received an official designation number, and no requisition has as yet been received in Supplies for material or component parts.”

It would seem that the P.S.B. was progressing under its own steam with officialdom being aware in a general sense but having a lack of detail knowledge of the design. Aircraft Production wrote to Porte, now a Lt Col, RAF, in April, in order to “remind you about letting me have some particulars of your scheme for the Super Baby, so that I can have an idea of the general lay-out of the scheme in its various stages. A few dates showing the stages of the programme would be of assistance.” On the 19th an official request was made for details of the flying boat “in order that official approval may be obtained for the machine to be constructed.” Approval was granted on 3 May 1918, under B.H. No.491, with the serial N123 allotted to the machine.

The fortnightly Reports of the Technical Department recorded the progress of the P.S.B. as follows:-

F/E 26.06.18. The hull is nearly ready to turn over. The wing fittings area being redesigned in accordance with recommendations of this Branch. Arrangements are being made to test a model of this hull in the National Froude Tank.Felixstowe P.S.B. Boat Seaplane.

(Five Eagle VIII). No specification. Design and construction of one machine.

F/E 12.06.18. Work on the hull and wings advancing well. Stress calculations are in hand.

F/E 07.08.18. No report has been received from O. C. Seaplane Experimental Station. Structural alterations have been asked for in the main planes.

F/E 21.08.18. The engine bearers are erected and the centre engine is fitted in place. There is likely to be some delay in this machine from non delivery of engines and streamline wires. Tanks are fitted in the hull and internal fittings are proceeding. Wing root stay tubes have been fitted. The hull has been launched, the cradle and trolley are well advanced and the bulkheads have been tested.

F/E 04.09.18. Streamline wires are not yet available, but all planes except top port have been erected with temporary wires. The tailfin is in position and the tail planes are being erected. Work is delayed by the non delivery of engines. A model has been forwarded for tests in the William Froude National Tank. Several structural alterations are required to bring the machine up to strength.

F/E 18.98.18. Tests results of the hull model in the William Froude National Tank have been received by the N.P.L. Streamline wires are now being fitted. Internal and external fittings being completed. The tail bracing is complete. Several points of structural strength (are) still outstanding.

F/E 02.10.18. N.123. As result of N.P.L. Tank Tests the forward step has been slightly modified. Main planes are being trued up. Collapsible dinghy has been commenced. All exhaust, oil and water pipes finished. Two jig engines are installed; the proper engines are urgently needed.

F/E 16.10.18. Machine N123. Collapsible dinghy design complete. All engines in position and bolted down. Main filter and pumps installed. Truing up complete. Tail unit partially dismantled for strengthening up, and new tail structure now being designed. Petrol system being fitted including throttle controls. Flooring, float attachments and seats are in hand and main controls are all in hand. New outer wing struts being made. Modifications to being machine up to strength under examination.

F/E 30.10.18. N.123. Erection is now complete and engines almost ready for trial run.

F/E 13.11.18. N123. Ready for trial run. Structurally passed for experimental work.

F/E 11.11.18. N123. New tail structure being made and Vickers pumps being fitted. Experimental turning indicators are also being fitted.

27.11.18. N123. This machine has done successful preliminary flights. It is proposed to fit a larger tailplane and also to revise the petrol system using Vickers centrifugal pumps.

Period 12 to 31.12.18. First time referred to as Felixstowe Fury. N123. Being fitted with new tail structure and Vickers pumps. Second machine has been commenced.

Three weeks ending 01.01.19. N123. Being fitted with new tail structure and Vickers pumps. Second machine has been commenced.

Month ending 31.01.19. N123. Having Vickers pump fitted. New tail unit nearly ready for erection. New tanks in hand. N130. Moulds and floors in preparation and keelson being framed up.

The reminiscences of Sqn Ldr Thedore D. Pix Hallam were published in 1919 and throw some light on how Porte was regarded by the men who flew his boats:

By this time Commander Porte had got out several experimental flying boats. He carried out his plans with a scratch collection of draughtsmen, few with any real knowledge of engineering; with boat-builders and carpenters he had trained himself; and he only obtained the necessary materials by masterly wangling. He frequently started a new boat and then asked the authorities for the grudged permission. But in all things connected with the building of flying boats his insight amounted to genius, and the different types of boats kept getting themselves born. His latest boat, known unofficially as the Porte Super Baby, or officially as the Felixstowe Fury, a huge triplane with a wing span of 127 feet, a total lifting surface of 3100 square feet, a bottom of three layers of cedar and mahogany half an inch thick, and five engines giving 1800 horse-power, I flew successfully - it weighed a total of fifteen tons. On this test I carried twenty-four passengers, seven hours’ fuel, and five thousand pounds of sand as a make - weight. Some idea of its huge size can be had when it is realised that its tail unit alone is as large as a modern single-seater scout.

It is evident that the RAF Technical Department, D Branch, on inheriting the P.S.B. from the Admiralty on the amalgamation of the RFC and RNAS to form the RAF, now wanted to control the experimental establishment at Felixstowe. It considered that Felixstowe should be handled exactly the same as a private firm and should follow the same procedure as detailed hereunder.

(1) Felixstowe is sent a RAF type specification for consideration and prepares GA Drawings for discussion, or would ask authority to proceed with an outline design likely to be of benefit to the RAE

(2) On approval of the GA drawings, recommendations would be made to authorise construction. In this case there would be no contract.

(3) On approval being communicated to Felixstowe, construction could begin.

(4) Drawings and particulars required to criticise strength would be called for. Criticisms would be communicated to Felixstowe in order that they could be addressed by Felixstowe.

(5) Construction would be watched by this Branch.

(6) The machine would make test flights by a pilot under Felixstowe control but no other service pilot would be allowed to fly the machine until it had been passed for strength by this Branch.

(7) Test pilots of this Branch would fly the machine for criticism of its flying qualities.

(8) This Branch would give clearance certificate and detail tests that were required, and then official testing would be arranged.

(9) This Branch would remain responsible for the machine until the design had been passed for production or turned down.

(10) Within the limits of the above procedures no communication would take place with Felixstowe on the design, etc., unless through this Branch.

It was in April that questions were raised about the allocation of five Rolls Royce engines to this project as “the boat is eventually intended for 3 Condor engines. Why not wait until the proper engines are available? We shall be very short of Eagle Rolls Royce engines soon, and there are many outstanding demands for them.” In response J.G. Weir, the Controller of the Technical Department, stated that “the results to be obtained from this Large Seaplane are worth the allotment of Eagle 8 engines and if it has to wait for the Condor engines before first trial a delay of four months is almost inevitable.” With the reduced power the performance would suffer but this was accepted.

In June it was noted that the Felixstowe calculations and those in London had used different assumptions. In some cases the factor of safety was below 4 but they could be raised to 4 with minor changes. It was understood that fittings would have to be redesigned “After the first machine, but on account of urgency they are only being strengthened with local additions at present.”

On 15 July the Technical Branch was informed that it was expected to commence erecting the machine within 10 days and the streamline wires, and the five Eagle VIII engines, all left hand tractors, were urgently required. On 8 August Felixstowe wrote that the lack of streamline wire would soon bring the erection of the machine to a halt. It was requested that as Messrs Brunton should have at least some of the wires ready, that they be dispatched by train.

On 14 August 1918, Porte was notified that the P.S.B. Boat Seaplane had been officially registered as the Felixstowe Fury and all “future questions concerning machines of this design should be referred to by these names.” Despite this the term P.S.B. still appears on Felixstowe documents. This same month a model of the Fury’s hull was sent to the William Froude National Tank for testing and as “the fact that the machine itself is nearing completion” it was requested that tests be carried out as a priority.

The Fury was the largest British aircraft of its day. The hull had been developed from the line of Felixstowe flying boats and was similar in construction. It is considered that the Fury also drew on the lessons learned from the massive Curtiss Model T triplane flying boat that had been assembled and flown at Felixstowe.

The hull was 60 feet in length and built on the Porte principle that followed landplane practice with four longerons built into a cross braced box girder, but more minutely designed in detail, the wiring being more systematic and all struts and fittings carefully planned. The keelson and floors were built up of mahogany in a lattice girder construction instead of being solid, as on the smaller boats. Very strong bracing was provided and special struts to transmit landing loads to the boat bottom. The hull was planked diagonally with two skins of cedar. The boat bottom forward of the step had an additional layer of planking making three skins in all. It was laid fore and aft and separated from the second skin by a layer of glued calico. This same material was used between the other two skins. Instead of the top and bottom of the fins meeting at an angle, the diagonal planking was steamed and bent around the chines and fin tops to form a curve of radius 5 to 8 inches. This eliminated the problems that occurred with the earlier F-Boats at these joints, while the thick edge gave a great increase in displacement for a small alteration of draft and made heavy overloading possible. The bottom plank did not end at the fin edge but was carried right over the rounded fin edge and, with another bend at the waist, up to the upper longeron. This provided a very flexible fin while avoiding the risk of leakage that characterised the built up form of fin edge. “It required very careful work to bend and fit the planks, but when completed and secured with the strong rubbing strip, it was a sound job.” The hull bottom was slightly concave. The hydroplaning efficiency of this hull was little inferior to that of the F.5. Bulkheads of Willesdon canvas were provided and tested by filling the fully separate compartments with water.

The upper and middle wings were of equal span of 123 feet, with the lower wing being shorter with a span of 89 feet. In order to avoid deep wing floats there was no dihedral on the bottom plane, the other two were given 2°. Balanced ailerons were fitted to the top and middle wings only and were coupled together. Control wires ran inside the wings. The centre section was separate from rhe wing bracing being supported by the struts.

The tailplane resembled that of the Curtiss Model T being of biplane form with a small balanced rudder mounted wholly above the tailplane, and twin unbalanced rudders mounted between the tailplanes. As with the Model T the lower plane could be adjusted in its entirety in the air for fore and aft balance. This was operated by a lever beside the pilot, through a screw attached to the leading edge of the lower tailplane. The screw was raised or lowered by a nut driven by a chain and sprocket. On the upper tailplane the elevator was worked in the usual way. The machine proved to be tail heavy in a glide and the tail was replaced by a larger more conventional biplane unit with triple rudders, a fixed lower plane with an elevator that could be adjusted by a lever at the pilot’s side to correct for fore and aft balance.

An unusual feature in the building of this boat was that the hull was constructed upside down, which method gave the men

access to their work, and allowed proper inspection.

Another new departure was the launching of the hull alone.

Previously, machines had been completely fitted up before being placed in the water but then leakages might be discovered in inaccessible places. With this boat, the hull was tested for watertightness, while the inside was still clear of obstructions, and all leaks stopped.

It had been hoped that 600-hp Rolls Royce or B.H.E engine would have been available for this boat but their unavailability meant that five Rolls Royce Eagle VIII engines were fitted instead. It was estimated that the arrangement selected, two sets of tandem mounted engines and one pusher, would allow for 67% of propeller efficiency, or a loss of 8% from the 75% allowed for a well designed single airscrew. This meant a loss of 150-hp out of the available 1,800-hp. “The loss at full speed is probably about 6%, but the loss at hump speed is a great deal which is the real crux.”

Six fuel tanks with a total capacity of 750 gallons were provided in the hull. They were all placed horizontally with a deck over them leaving plenty of room between them and the hood for access. “Recently the tank capacity has been doubled, making it 1,500 gallons or 4% tons.”

Cooper Servo-motors were fitted to all controls but were to prove not to be needed as the Fury proved remarkably light on the controls. Major Arthur Cooper had been asked by Porte to design an entirely mechanical servo-motor for the Fury to replace the Sperry servo-motors that had proved troublesome. A lever could lock these servo-motors out of gear when not required. Cooper also assisted in the testing of the Fury as related hereunder.

An adjustable tailplane presents some difficulty in the case of a biplane tail plane. In the case of the P.S.B. the elevator on the lower plane was operated separately by a long lever on a quadrant centred on the elevator control shaft. This was used to obtain trim and the upper elevator for extra control in the usual way. The result was quite satisfactory, but owing to hull interference the efficiency of the lower plane was relatively low.

Engine run ups were conducted on 30 October for final adjustment with one day being set aside for final inspection, launching being set for the 1 November. The launch was delayed until the 12 November 1918. The Fury taxied around the harbour and was taken just off the water several times on three engines and found to behave quite well. On the next day

She was taken off by Col. Porte and Major Cooper with 9 passengers and 300 gals. Fuel i.e. a useful load of about 4,000 lbs. All five engines were running but the centre one was not opened out except for a top speed trial on one flight. The machine was taken off and landed four times, three of which were straight, but on the other flight turns were done with about a 15° bank.

The machine got off and landed well, was fairly clean on the water but at one speed the wash met over the tail of the boat though it did not affect the tail planes.

The machine was rather tail heavy in the air due to an error in the setting of the tail plane but was well under control both with the engines on and off. It was intended to alter the tail setting and continue trials as soon as possible.

Major Cooper considered more tail area was needed but was satisfied that the machine was safe to carry out the trials as she stood. The high centre of thrust did not affect the stability as had been anticipated.

Major John D. Rennie had worked with Porte at the Felixstowe Experimental Section and was a defender of Porte’s method of construction. In his Royal Aeronautical Society address he noted that with

regard to fin and rudders, these were fairly large in the Felixstowe F boats, but barely sufficient for control with one engine cut out completely. The P.S.B. was very satisfactory in this respect due to the engine arrangement of three propellers abreast and three fins and rudders in their slipstreams.

The rudder, ailerons, but not the elevators were balanced; servo-motors were also fitted to all control surfaces as it was thought that while adequate control under certain flying conditions might not be within the capability of the pilot, there being no previous experience with a boat of that size. However she proved to be extraordinarily light on all the controls and superior to the much smaller “F” boats. The servo-motors were removed as Col. Porte decided that any advantage to be gained did not warrant the additional weight and complication.

The 14th of November saw a test to ascertain the maximum air speed attainable. The pilots were Major Cooper and Capt Scott. A large circuit was made over the Cork Lightship whilst climbing. The speed runs from the Felixstowe Pier head to Walton Pier Head and vice versa were accomplished without incident. Average speed was 92.25 knots (about 114 mph). After the conclusion of the speed runs a portion of the port tractor engines exhaust pipe broke away, exposing the radiator and a strut to the hot exhaust. Leakage of the radiator occurred prompting a landing. Whilst flying the servo motor serving the rudder jammed and could not be disengaged. Cooper remembered that one of the new servo-motors that he had designed

had been fitted to the rudder control, and I decided to try it out. When I switched on the servo-motor the rudder became fixed and could not be moved in either direction. I could not disengage the motor by the lever owing to the load. I had prepared to land without rudder when at last I managed to disengage it. The machine took to the water very well. The cause of the jamming of the control was that the wire from the motor had been connected to the wrong wire from the hand control so that it pulled against it instead of assisting.

This would have been one of the longest flights the Fury had made. Most trial flights were of a couple of minutes only.

The water performance of the machine was far ahead of expectations. At a gross weight of 2150 lbs. she got off with three engines only corresponding to 24 Ib/H.P.

There was no sign of diving at low speed porpoising. The nose may have been too high for least head resistance, when hydroplaning, but there was not the least difficulty in getting off. Landing was extraordinarily easy and shockless.

From preliminary testing the following points were brought out:

The speed full out was 92.5 knots with a weight of 25,650 lbs.

The hull was described as “staunch and tight.”

The boat was flown without the servo motors.

The machine was tail heavy in a glide with the fixed tail set at 2°. A new tail unit of greater area was designed.

The petrol pumps were not entirely satisfactory and it was proposed to fit Vickers centrifugal pumps.

No trouble was experienced in getting the boat in and out in a light wind.

The machine handled easily on the concrete areas by about 20 men. The boat handled very easily on the water.

“The trials showed no important defects and the results are considered very promising.”

On 23 November 1918, a test was undertaken to determine what load the “P.S.B.” could take off smooth water and without wind. The pilots were Majors T.D. Hallam and Ronald Moon. Short straight flights were made with the moveable tailplane set at neutral. The fixed tailplane was set at 2°. After alighting the moveable tailplane was set at 1° down. A second and third flight was made at about a height of 40 feet. During the fourth flight the boat got off in 30 seconds and several turns were made at an altitude of 1,500 feet. The load was 30,450 lbs. Takeoff speed was 55 mph and landing speed 60 mph.

For the second test the weight was 32,500 lbs, and the takeoff speed was 62 mph after a run of approximately 49 seconds and after climbing to 100 feet, the boat was landed at 60 mph. “The test showed, that the resistance of the steep V bottom was not excessive. The loading was 18lbs/H.P.”

November also saw tests on the engines to determine that all were running up to speed and that the propellers were performing satisfactorily. The tandem engine installation was new and not fully understood. The USN had a similar problem with the NC flying boat engine configuration for the trans-Atlantic flight of these machines. A collapsible lifeboat was made at this time for the Fury for the “safety and convenience of the crew.” A report of late December noted that the boat was being fitted with a “new tail structure and Vickers pumps.”

Grain test report NM250 is not dated but the speed and climbing trials recorded therein are dated 18 and 19 June 1919. The triplane was described as stable longitudinally at all speeds by setting the adjustable auxiliary elevator. It was stable laterally and directionally.

Under the heading “Controllability,” longitudinally the “Auxiliary elevator makes machine very nice to fly, but main elevator is slightly soft at low speeds especially when landing.” Lateral controllability was very good; directionally it was very good “but heavy, should be fitted with servo motor.” The cockpit layout for controls was good with the only suggestion being made that the engine altitude control should be fitted in reach of the pilot. The machine was not tiring to fly except when manoeuvring when a servo motor was “needed for rudder control.” The boat alighted “very easily and gently but elevator control is slightly soft at low speeds.”

Little information seems to be available on the proposed armament of the Fury but one source suggested that the armament was four Lewis guns and a heavy bomb load. Knowing the number of guns carried by the F.2A this seems too small a number for a boat the size of the Fury. In one file there is a suggestion that the “fighting tops” developed with the F-Boats could be used on the Fury, but the memo corrects the questioner and confirms that the “Fighting Tops” were erected on an F.5 boat, not the Fury. The N.4 flying boats were considered for the mounting of a C.O.W. gun, and although an interim design between the N.3 and N.4 specifications, it appears that this Porte boat was considered for mounting this weapon. The C.O.W. Gun weighed 200 lbs and each complete round weighed 2 3/4 lbs with the mounting and sight adding a further 30 lbs. With respect to the P.S.B. Porte was notified that designs were in hand for an incendiary shell, also an HE shell with a sensitive fabric fuses. An armour piercing shell had been designed and supplies were being made of an HE shell with a “fairly sensitive percussion fuse.” The gun could fire single shells or six automatically at a rate of about 120 rounds per minute. It was suggested that an officer of the Technical Department be sent to Felixstowe to discuss the armament of the P.S.B. in order to keep in touch with the “latest developments.”

From the testing of the Fury it was determined that the extraordinary behaviour of the hull in rough seas was due mainly to the buoyancy of the hull and the lines adopted. With a load of 28,000lbs, the chine at main step was not submerged. Under all conditions, the propellers, cockpit and tail plane were clear of water thrown up. From this point of view it was found that the bow sections could be improved considerably. These were too blunt, resulting in unnecessary pounding when getting off or landing in a rough sea, or at moorings. It was decided in any future designs to drop the keel profile forward, keeping everything else the same, thus obtaining a finer entry, without loss of buoyancy forward.

The development work on the Fury appears to have proceeded at a more leisurely pace with the coming of peace. It was proposed that the Fury undertake a trans-Atlantic flight as it was well within its range. On 28 November 1918, the Assistant Controller, Design, noted that the Fury would not fly again until the New Year owing to changes being made in the tail structure. A second machine to undertake the Atlantic Flight was required “as a demonstration and for encouragement of commercial aeronautics.” As there would be great difficulties in having this built by private firms as the design and drawings were in an incomplete state, the machine should be constructed at Felixstowe and instructions had been issued to Lt Col Hallam to go ahead.

In a report of 21 December 1918, it was stated that construction of the second machine had been commenced at Felixstowe almost entirely from material drawn from RAF stores. For the few small parts that were required it was asked that they be given 1st class priority, due to the urgency of completing the machine for the Trans-Atlantic flight. This was to be made from Cape Broyle Harbour, Newfoundland. The Navy was requested to make shipping available to transport the flying boat to here and for ships to be along the route. The range of the boat was estimated by Col Porte as 1400 statute miles “Although it may be possible to get another 100 out of her.” The Report asked “Is it or is it not worth while that the first Aircraft to cross the Atlantic shall be built, designed, and manned by the British.” In the 27 March edition of Flight it was stated that the “Air Ministry is hurrying on the preparations for an attempt by one of the “Felixstowe Fury” flying-boats, which would be navigated by Col. J. C. Porte, R.A.F. The attempt would be made from Newfoundland with stops at the Azores and possibly Lisbon.” There was a change in direction in June as the prototype was to be used for the flight. It was to be dismantled for shipment to the US for the attempt. It is assumed that the time factors would not allow for the second machine to be completed in time with the number of contestants already in the race. The success of the Alcock and Brown Vickers Vimy doomed this project, although it has been suggested that it was cancelled due to a lack of funds.

The Felixstowe Fury story ended on 11 August 1919, when the machine crashed at Felixstowe. The flying boat was to have to flown to South Africa via Gibraltar, Egypt and the great African lakes. The machine was provisioned and equipped for the trip. The crew comprised Lt Col P.F.M. Fellowes as OIC; Major Edwin Roland Moon, DSO, pilot; Capt C.L. Scott, DSC, pilot; 2/Lt J.E Arnold; Chief Engineers W/O H.S. Locker and W/O J.G. Coburn; Lt S.E.S. McLeod W/T operator. The Fury was taking off for Portsmouth for the start of the African flight. It had just rose from the water when the port wing dipped, struck the water and the machine crashed in Harwich Harbour. McLeod was drowned, the rest of the crew surviving. It appears that the machine lifted off before it reached safe flying speed. Both Porte and Rennie had left the service before this flight and there was no technical officer at Felixstowe to supervise experimental flying.

What follows is an eyewitness report of the tragedy. The copy in the Felixstowe file is not signed and the initials appear to be RDO. The author of this report wrote to Porte on 12 August that he and General Ellington went up to Felixstowe and “saw it all.”

He taxied the machine in a southerly direction first, I.E. to get clear of the jetties, buoys, etc., and then turned left-handed towards the mouth of the Orwell with the object of course, of getting down wind before starting to rise. It struck me that the machine was rather left wing down while taxing and the left float was frequently in the water; this must have been due to the machine turning rather left-handed most of the time. It taxied about 3/4 mile down the river and appeared to be perfectly under control on the water. It then turned round heading rather east of N.E. Moon then opened up the engines and taxied the machine for about 500 yards; the machine seemed to me to take a very long time to rise out of the water at all and appears to be practically as low in the water the whole time as it was when standing still. After about 500 yds, however, the machine began to skim along the top of the water and then rise about 5 ft. in the air for about 20 or 30 yards, then dropped down on to the water again keeping level the whole time, i.e. the tail of the machine was not at all down when it got off the water nor did the nose of the machine drop when it dropped back on to the water again.

I then had a look at the wind and saw that it had changed further round to the north so that the machine was now taxing at an angle of about 45° to the wind, the wind of course coming from the right side of the machine. The machine went on taxing for about another 100 yds. or so and then rose from the water again very awkwardly. It turned right-handed while in the air so as to be heading momentarily almost straight into the wind. It never seemed, however, to have flying speed and a few moments afterwards it dropped towards the water, turned left-handed, the port plane struck the water, and the machine crashed completely. The total time from the moment that Moon opened out his engines until the crash occurred was 59 secs, and it would seem that each time the machine actually rose from the water it was doing nearly 60 m.p.h. According to what Moon stated the machine was very nose heavy. He had the moveable tail plane and elevator right back but even then could not get the nose up.

I had a look at the fixed tail plane when the machine was brought in and it certainly was up, I think in its maximum position, so that there was no question of the controls, at any rate these controls, being reversed.

The measurements of the rigging appear to be absolutely correct and the machine had apparently flown twice since its accident on test some weeks ago.

The only reason that I can see to account for the accident is the loading of the machine. It was not fully loaded, apparently about 2,000 lbs. short of the full load, but I fancy that the load was distributed wrongly. I spoke to one of the mechanics who was responsible for the petrol; he stated that various spares had been loaded in the back part of the machine and that in order to counteract these he had left the rear tanks empty and filled the front tanks about 2/3rds full, the centre tanks being pretty well filled tip. No attempt seems to have been made to weigh out the various spares that were carried and one knows that aeroplane spares look much heavier than they are. However in addition to this there was considerable weight of wireless apparatus, some rifles, ammunition, rations, thermos flasks, officers kits, and other oddments, most of which seem to have been put in more or less at the last moment and in the front part of the machine...

I see according to the Evening papers that the hull of the body opened and let the wireless operator - Macleod - drop to the bottom, this is quite wrong: the port side of the hull did open out more or less along the water line but Macleod was still inside when the machine was dragged to the beach. His position was apparently down below so he really never had a chance.

Flight reported on 14 August 1919, that the Fury made towards Landguard Point and then turned to get a favourable wind but there was apparently some difficulty in clearing some buoys and a river boat.

At the inquest on 12 August 1919, Lt S.E.S. MacLeod who was killed in the crash of the Fury received a verdict of “accidental death” - no light was thrown on the cause of the accident. Charles Gates “served the last four months of my RAF Service there and saw something of it (the Fury). I was friendly with its wireless operator, Lieutenant Sam McLeod (sic) who was drowned when it crashed on 11 August 1919 when taking off on attempt to fly to Cape Town... McLeods station was in the bowels of the ship amongst the fuel tanks. I had often urged him not to be there on take-off and landing. That crash was some months after I had been sacked with a ‘gratuity’ of Ninety Pounds for four years war service. I never flew in the Fury but, with McLeod, tested its radio equipment in a F2A.”

Major Rennie in his RAeS paper made the following observations.

With regard to the “Fury, ” it is quite obvious many important facts are not generally known. Prior to the accident she had done about 30 hours flying, and in every way was found most satisfactory. Under the control of expert boat pilots, such as Colonel Porte, Major Hallam, Hobbs, Wright, and Cooper, porpoising to any serious extent was absent when taking off. The tendency was there, but sufficient elevator control was available to keep it down. Owing to the fact that the tail plane being covered by the propeller slipstream, there is more elevator control over the range of speed between the hump (speed) and taking off) than is probably realised.

The C. G. position had been determined by weighing in the usual way, contrary to what is stated in the report on the accident.

Several months before the accident Colonel Porte and myself were demobilised, there was therefore no technical officer in charge. No one knew where the C. G. ought to be or took the trouble to find out. The result was that the boat was loaded up with spares, etc, and the fuel, of which there was tankage for 1,500 gallons, most likely distributed in the tanks such that the final C. G. position was at least .5 of the chord. Further, from a reliable and intelligent member of the crew, the late Major Moon attempted to take her off, as he had done on a previous occasion, before the minimum safe flying speed had been reached. As loaded, she was underpowered, there was therefore little available h.p. for acceleration, once clear of the water with the inevitable result.

Rennie was of the opinion that the Fury had been taken off in a stalled condition. He recorded that the “elevator control will be sufficient to trim the boat through nearly the whole range of attitude” maintaining the wings at a safe flying angle. Unless there was ample power for acceleration or “take off’ speed, say 5 knots above stalling speed and elevator corrected, “there is the possibility of the boat leaving the water stalled.” Work on the second Fury, N130, was abandoned in September 1919 after the loss of the first machine. It is not known if the improvements mentioned by Rennie were incorporated into the second machine.

After he left the RAF Porte had been employed by the Gosport Aviation Co Ltd and had undertaken a number of designs of commercial flying boats for that concern. These were based on the work he had undertaken at Felixstowe and the Gosport G.9 triplane, powered by three 600 hp Rolls Royce Condor engines was obviously based on the Fury. Porte died in October and the company folded when post-war orders did not materialise.

Rennie recorded that from every point of view the Fury was “the best design turned out at Felixstowe. It was found that the normal load could be increased to 28,000 lbs, under which loading, seaworthiness, ease of taking off and launching were superior to that of previous F-boats. Loading tests continued up to 33,000 lbs, at which Colonel Porte took her off in Harwich Harbour. Landing under all loads was without perceptible shock.” According to Rennie the extraordinary behaviour of the hull in rough seas was due mainly to the buoyancy of the hull and lines adopted. With a load of 28,000 lbs the chine at the main step was not submerged and under all conditions, the airscrews, tailplane and cockpit was clear of water thrown up. The bow sections were too blunt resulting in unnecessary pounding when getting off or alighting in a rough sea or at moorings. It had been decided that in any future designs to drop the keel profile forward but keep everything else the same, thus obtaining a finer entry without loss of buoyancy. He lamented that the hull improvements incorporated in the design of the Fury’s hull had not been followed up as “these improvements led to a hull greatly superior to that of the “F” boat hulls, it is most unfortunate that the development of this type of hull has not been proceeded with, more especially when one realises the achievements and performance of these boats.”

Post-War Civil

The Gosport Aviation Co on the Solent was building the F.5 and, according to H. Penrose, Porte had announced that he would be willing to join the company after the end of the war. Flight for 15 December 1919, devoted an article - “Some Gosport Flying Boats for 1920” to the company’s proposals. The article noted that the late John Porte had joined the company in August 1919 as Chief Designer, and had produced several designs based on his successful types in the late War modified to suit commercial requirements. The types are illustrated by drawings and their Felixstowe lineage can be clearly seen. The G.9 was a triplane flying boat based on the Fury and featuring the 600-hp Rolls Royce Condor engines that were to have originally powered the Fury. They were arranged with the two outboard engines as tractors and the central one as a pusher.

Показать полностью