Книги

Centennial Perspective

C.Owers

The Fighting America Flying Boats of WWI Vol.2

400

C.Owers - The Fighting America Flying Boats of WWI Vol.2 /Centennial Perspective/ (23)

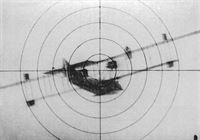

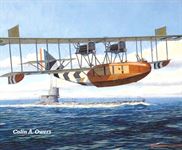

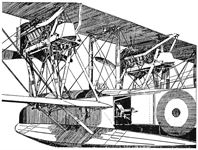

The war over the North Sea did not get the same coverage as that on the Western Front in the pulp magazines between the wars. Here is a sketch from the story "Raiders of the North Sea" from Air Stories, Vol.4, No.4, April 1937, depicting combat between a dazzle painted Felixstowe boat and Brandenburg monoplanes. The W.29 floatplanes bear the intermediate straight cross national insignia as seen on many and are lining up to attack from astern. The Felixstowe boats would dive for the surface of the sea in order to prevent the enemy from attacking from below where they had poor defence.

6. The America Flying Boats in Detail

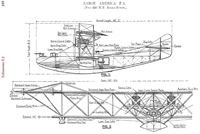

Felixstowe F.1

The Felixstowe F.1 was the name given to John Porte’s experimental flying boat that had an experimental Porte designed hull and H-4 aerostructure. The hull was built on aircraft lines with cross braced girder of simple longerons and spacers to which was attached the bottom of the hull. Power was provided by two 150-hp Hispano-Suiza engines.

Unfortunately on test the following result occurred. “On practically smooth water and with no wind, both with the elevator full up and down, the flying boat failed to unstick the tail.”

Specifications

Length hull 36 ft 2 in. Wing Span: Upper 72 ft. Lower 46 ft. Chord 7 ft; Gap 7 ft 6 in. Engines: Two 150-hp Hispano-Suiza.

Felixstowe F.1

The Felixstowe F.1 was the name given to John Porte’s experimental flying boat that had an experimental Porte designed hull and H-4 aerostructure. The hull was built on aircraft lines with cross braced girder of simple longerons and spacers to which was attached the bottom of the hull. Power was provided by two 150-hp Hispano-Suiza engines.

Unfortunately on test the following result occurred. “On practically smooth water and with no wind, both with the elevator full up and down, the flying boat failed to unstick the tail.”

Specifications

Length hull 36 ft 2 in. Wing Span: Upper 72 ft. Lower 46 ft. Chord 7 ft; Gap 7 ft 6 in. Engines: Two 150-hp Hispano-Suiza.

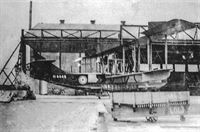

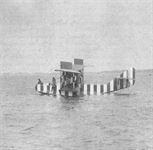

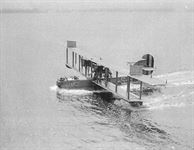

3580 had a new hull built to Porte's method of construction. Initially it has two Anzani radial engines but is shown with two 150-hp Hispano-Suiza engines.This machine became the Porte I, later renamed Felixstowe F.1. It was at the Felixstowe Seaplane School by 29 December 1917, not being written off until early 1919. Note the pitot tube extending from the bow.

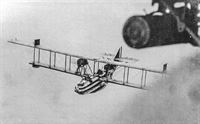

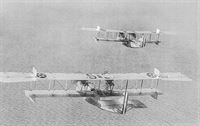

With an original caption stating this is also the F.1, this Felixstowe boat has a revised rudder and forward gun ring.

6. The America Flying Boats in Detail

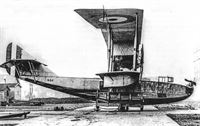

Felixstowe F.2

The evolution of the F.1 and F.2 is described in Chapter 2. 8650 was reported as undergoing overhaul between 14 August and 4 September 1916, and it is likely this is the period it was fitted with the Porte hull. The combination of a new Porte hull with the H-12 wings and a new tail unit led to a better boat that was designated F.2 although it retained the serial 8650. With more powerful engines it was developed as the F.2A.

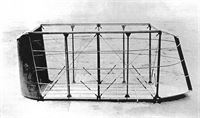

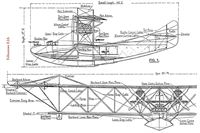

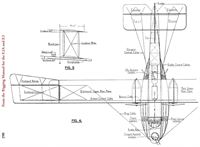

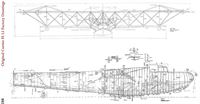

The F.2A Described

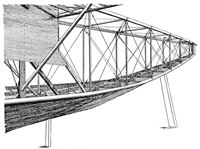

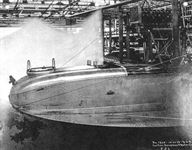

The hull was composed of four longerons with horizontal and vertical spacers braced by diagonals and steel cables. The planning bottom was constructed of two-ply cedar inside and mahogany outside. Varnished or doped fabric was sandwiched between the two layers. The bow, decking and cockpit framework was mahogany while the sides back to the trailing edge of the lower wings was birch plywood. The top of the hull behind the wings was fabric covered to save weight. A 12 inch deep mahogany washboard ran along the lower longerons. The front part of the hull as far back as the rear spar was a rigid built-up structure. From here to the rear the structure was a typical fuselage structure with doped fabric covering above the 12 inch solid mahogany washboard. This was to cause problems, and following the loss of H-16 N4510 on 8 April 1918, in heavy seas, due to the failure of the fabric sides on the tail of the boat, the USN recommended that this defect be corrected on all its H-16 in service. The fabric was to be replaced on some boats with ply sheeting. The fins were built onto the outside of the hull and were planked on the top with three-ply. The hull was double planked. Most WWI built aircraft show variations however the Felixstowe boats show more than others. This was due in part to the different manufacturers of hulls and the aerostructure being allowed considerable latitude and the modifications worked out in active service and applied at stations.

The hull was V-shaped and curved from bow to stern while the tail portion was raised such that it rose clear of the water when at rest. The side fins were built onto the outside of the hull. The planking was double diagonal comprising an inner layer of 1/2 inch cedar and an outer layer of 3/16 inch mahogany, the two with a layer of varnished fabric sandwiched between them. Sliding panels in the hull behind the wings allowed for a Gallows mounting for a Lewis Gun on each side. These could be swung outboard and covered the tail of the boat thus overcoming one of the H-12 defects. A pilot of the F.2A could alight in much rougher seas with less fear that the hull would be damaged, and he could take-off in rougher waters as it did not hammer the water to anything like the extent that the practically flat bottom of an H-12 did. This was despite the F.2A being designed by Porte to utilise the sheltered waters of harbours such as Harwich, the necessities of war calling for more from the boat than its designer intended.

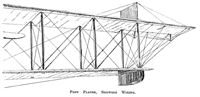

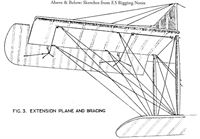

The wings were a typical Curtiss wooden structure and plan form although the F.2A boats had ailerons that projected beyond the wing trailing edge. Late boats had open cockpits and balanced ailerons.

The decision to change from a 23 inch to 20 inch gun ring involved structural alterations and delayed production, the type entering service late in 1917. The number of Large America boats required for the 1918 program was estimated to be 180 in May 1917, and this was revised to 426 with the revised program of July 1917. The average life of the big boats was six months and therefore twice the number of boats was required to meet the estimated establishment figure. The entry of the US into the war and the USN’s agreement to take over and equip five naval air stations provided some relief to the situation as even with the Porte method of construction, it would have been impossible to produce the number of boats required. In March 1918, 161 F.2A and F.3 boats were on order, however only ten F.2A and one F.3 were in service.

The F.2A suffered with problems with its fuel system. The length of piping it contained ran from the main tanks in the hull where wind-driven pumps forced the fuel to the gravity tanks in the top wing centre section. From here the fuel was fed to the carburettors of the Eagle engines.

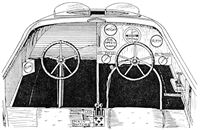

From about September 1918 all the new F.2A had open cockpits, the canopy being done away with. They were slightly faster as a consequence and the pilots had a better view backwards. The fabric was deleted from the rear of the hull and replaced with Consuta sewn ply. Horn balanced ailerons were introduced making them less tiring to fly. The F.2A had dual control unlike the H-12. The co-pilot’s control wheel folded enabling him to leave his position and access the front gun cockpit.

F.2A Serial Allocation

Serials Number Contract Manufacturer First Delivery Notes

N1260-N1274 15 AS3610 (BR17*) Curtiss, Canada. H-16. Presumed renumbered N4060-N4074.

N2280-N2304 30 AS 14154 (BR80) S.E. Saunders Ltd. Renumbered N4280-N4309.

N2530-N2554 25 AS21558 AMC Ltd. Renumbered N4530-N4554.

N4080-N4099 20 AS14154 S.E. Saunders Ltd. Delivered from late July 1918.

N4280-N4309 30 AS 14154 & AS34426 (BR80) S.E. Saunders Ltd. Delivered from mid-November 1917.

N4430-N4479 50 AS4498/18 (BR349) S.E. Saunders Ltd. 18.10.18 Some delivered as F.5s.

N4480-N4504 25 AS4502/18 (BR350) May, Harding & May 21.09.18 Erected by AMC Ltd. At least 21 delivered.

N4510-N4519 10 AS2697 May, Harding & May 12.01.18 Specification N.3B. Sunbeam engines contemplated for this batch.

N4520-N4529 10 AS24912 (BR74 & BR90) May, Harding & May Cancelled.

N4530-N2554 25 AS21558 May, Harding & May Erected by AMC Ltd?

N4555-N4559 5 AS24912 Cancelled.

N4560-N4579 20 38a/551/C564 & AS24912/18 (BR589) May, Harding & May Last seven cancelled.

The cost of an F.2A including hull and trolley, but without engine and armament was £6,738. Eagle VIII engines cost £1,622.10.00 each.

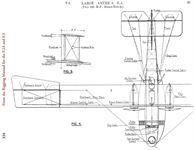

Felixstowe F.2C

At the 12 June 1917, Meeting of the Air Department Progress Committee, Cdr Longmore reported that the trials of the F.2C were being carried out at Felixstowe. The machine was to go to the Isle of Grain for testing. The F.2C was described as being similar to the H-12 “but has a different hull which is not quite so efficient as a hydroplane and has been found to be considerably better for landing as it has not the same inclination to leave the water again on being landed as the H.12 hulls have.” The F.2C had a hull of lighter construction and greater volumetric size than the F.2A and F.3, its proportions seemingly to anticipate the F.5. The hull had steps of revised design and the forebody’s contours were different from those of the F.2A. The pilot’s occupied an open cockpit. This was due to the fact that they had very little rear view in the canopied H-12 and F.2A rather than the usual answer that pilot’s preferred an open cockpit. The front gunner’s cockpit was farther back from the bow and there were no waist gun positions. Powered initially by two 275-hp Rolls-Royce Eagle II engines, these were later replaced by 322-hp Eagle VI engines. Official performance trials were held on 23 June 1917, and although performance was slightly better than the F.2A, there was no chance of it being placed into production and upsetting the F.2A program that was then underway, only the prototypes N64 and N65 were built.

N64 and N65 were sent to Felixstowe where they joined the War Flight. Porte led a patrol of five flying boats from Felixstowe in N65, his latest experimental boat, on 24 July 1917. His pilot was Queenie Cooper, the test pilot. This was the first time that Felixstowe had been able to field this many boats at once. They spent a long time getting into their correct position for take-off. In future this was to become common and they were got away easily.

Discovering a submarine on the surface, the patrol attacked. Three of the boats dropped bombs, including N65. The other two boats stood by but the submarine appeared to be finished. This submarine was incorrectly reported as UC-1.

While on a Beef Convoy patrol in late September 1917 Pix Hallam and Watson in N65 sighted a submarine and they immediately attacked. The F.2C was equipped “with a gadget for dropping bombs by compressed air, which, according to its proud inventor, was to supersede the good old way of dropping them by pulling a Bowen wire.” Unfortunately a good attack was ruined when the bombs hung up. The device hissed as compressed air escaped but the bombs refused to leave the racks. A nearby destroyer then attacked with depth charges.

N65 was written off after it was holed and sank at the Isle of Grain on 13 March 1918.

N64 was converted into an F.3 about October 1917. It was used for patrols and for experiments.

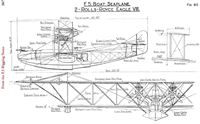

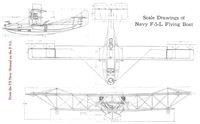

Felixstowe F.3

The F.3 was designed to meet the need to carry a larger bomb load as the 230-lb bomb was considered no longer satisfactory for attacking submarines. A Progress Committee Report of 12 June 1917, noted that all new “Americas” now on order would be of this type.

The F.3 actually preceded the F.2C. The F.3 had the same large overhang of the upper wing and king-post structure above the interplane struts. Its hull was three feet longer than the F.2A and the wing were of greater span and chord. These differences are not very noticeable in photographs and if the serial is not visible the only way to tell the difference is that the F.3 had a slight recess in the leading edge of the upper wing immediately behind the airscrews.

The F.3 had a typical Porte hull and was planked the same way as the F.2A. The fins were planked with three-ply birch. On later examples double diagonal planking was used. The floors of the F.3 were rebated into the keelson on either side and caused the planking to spring and the boats to leak badly. Intermediate timbers were introduced to try and overcome the problem. Sir A Robinson recalled that on

at least one station, where they often had to be bounced off a long swell, it was found that the planking was apt to open up from the keelson. A new boat on arrival would very probably be dismantled and the petrol tanks removed, to permit a series of oak knees to be put in to strengthen and hold together the bottom planking.

The F.3 could carry four 230-lb bombs while the F.2A could only carry two. This may be the reason that more F.3 boats were ordered than F.2A boats. Lt (later Major) J.D. Rennie was Porte’s Chief Technical Officer at Felixstowe and who assisted him in the development of the successful Felixstowe flying boats stated post-war that the F.3 should never have been put into production.

The prototype, the converted N64, was powered by two 320-hp Sunbeam Cossack engines. Production machines had Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII engines.

The F.2A boats went to Felixstowe, Yarmouth, Dundee, Calshot, and Killingholme, until that latter station was taken over by the USN and they began to receive Curtiss H-16 boats. The F.3 on the other hand went to Cattewater, and the Scillies, and to Houton Bay in the Orkneys. The reason for this was simple. The F.3 used the same Rolls Royce Eagle VIII engines that the F.2A used, was heavier and slower and less manoeuvrable and was unable to engage Zeppelins or German seaplanes. The F.2A went to those stations where reconnaissance and fighting was the most important, while the F.3 with their greater fuel capacity and bomb load went to stations where aerial opposition was less and hunting U-boats was more important.

The first operational flight of a F.3 was in July 1917. The type came in for modifications at the stations as had happened to the F.2A. The tail fabric would be replaced with ply sheeting. Sometimes the double bottom planking was put on the wrong way around so that the water flow was across the outer skin of planking and not along it. The bottom would be removed and replanked, a not infrequent activity according to Sir Austin Robinson.

A report on a Phoenix built boat, N4400, noted that:

1. The mahogany outer planks of the hull bottom aft of the step were buckling outwards, due to swelling. The planks were about 4 1/2 inches wide and were only secured along the joints, no intermediate copper clenched nails being employed.

2. Brass screws were freely used to fix the planking to the heavier framing timbers, and many were sunk too far into the outer planking. They should have been only slightly countersunk.

3. The footsteps were not correctly finished off to prevent water getting into the hull. “These should be boxed up on the inside of the hull to make the hull watertight.”

4. The interplane flying and landing cables were not correctly finished.

5. An elastic adjuster “will be fitted to the cloche for balancing the elevators, to replace the present crude arrangement.”

6. There was a great deal of sway between the hull and the main spars.

The report noted that the defects would be corrected at the station and suggested remedies for some problems.

In October 1918 the Technical Department of the RAF wrote to the Admiralty noting that problems with the hulls of flying boats was due to “lack of sufficient transverse strengthening members and incorrect method of fixing the plank on the bottom hulls.” While modifications had been introduced some three months back great difficulty had been experienced with hulls in store and they had been issued to the various “super-structure Contractors” who were not hull builders and had neither the expertise nor facilities to undertake the modifications required. Lack of accommodation and lack of the necessary facilities to carry out the modification work on stored hulls was blamed for the slow rate of production of modified hulls from store and the issuing of unmodified hulls.

The following report of 23 June 1918, from Houton Seaplane Station captures the problems present in the manufacture and operating of these large flying boats. Houton reported that none of its flying boats were fit for action as follows:

- N4245 Capsized on slipway in strong side wind.

- N4232 Sank on arrival and is being recaulked and fitted for service.

- N4406 Developed leaks in hull after 48 hours on the water. Sent to Houton from Stenness for repairs on 21 June.

- N4235 Sank on arrival and is being recaulked and fitted for service.

- N4403. Driven ashore in gale 13 June, bring repaired.

- N4230. Undergoing its first fitting out on arrival.

These were all F.3 boats. The Station also had Porte Baby 9810 that had been driven ashore in the 13 June gale. It had yet to be floated, a special slipway and cradle were being constructed for that purpose.

This unsatisfactory state was due to:

1. The station not being fully completed for service.

2. The machines being leaky and not ready for service when they arrive.

3. The bad weather in June.

4. A severe epidemic of influenza at Houton.

The majority of men on the station were recruits of one or two months service and had no experience of repairing or handling Large America, seaplanes. Only one shed had been available and that provided accommodation for only one seaplane, and all fitting out and repair of other machines had to be done in the open. Two cases of the aircraft breaking adrift of their moorings were due to the moorings being at fault, however the gale was a sever one and the F.3 boats were larger than the Porte Boat for which the moorings had been designed.

Only one seaplane arrived equipped with W/T. All others had to be wired up by station staff and this took about three weeks.

A Report of 23 May 1917, had noted that the Large America seaplanes had proved most satisfactory for submarine patrol work and large numbers would be used in Home Waters in 1918. The greater part of the establishment of 180, if not the whole output, would be needed for Home. It was considered that it was inevitable that these machines would be required for the Mediterranean, particularly in connection with the Otranto barrage. As this establishment was thought to be the output available from the UK and America, it was proposed that the boats for the Mediterranean be built in Malta under Dockyard control.28 The Air Department Progress Committee had already considered this at its Meeting on 15 May. At this Meeting it was suggested that it might be possible to have the hulls built in Malta and as the Maltese carpenters were expert boat builders, there should be no difficulty in turning out first class hulls. The wings would be built in the UK and shipped out for erection at Malta. All F.2A boats were used in home waters however the F.3 was used extensively in the Mediterranean. The F.3 was to be built in Malta. The local craftsmen were skilled boat-builders and local women did the fabric work.

In November 1917 Malta reported that work on wings for F.3 boats was practically at a standstill. The next day another telegram noted that the two Rolls Royce engines “just received for the first boat” were 345-hp. They also requested a full set of F.3 drawings for the 360-hp Rolls Royce engine. By January 1918 Malta reported that some of the Silver Spruce sent for main spars was defective and required 300 feet run 4 inch planks in 32 feet lengths to be sent by quickest means “to complete 12 boats.” A total of 18 F.3 boats were built in Malta.

The F.3 saw service in the Mediterranean and in September 1918, three F.3 boats flew from Malta to Tripoli where they bombed a wireless station on the Gulf of Sirte suspected of communicating with U-Boats. This operation took place over three or four days. In October the type accompanied the naval attack on Durazzo in Albania.

F.3 Serial Allocation

Serials Number Contract Manufacturer First Delivery Notes

N64 1 BRI 17 Felixstowe NAS Completed as F.2C, converted to F.3.

N1950-N1959 10 AMC Ltd Cancelled.

N2160-N2179 20 AS 11426 (BR22) Handley Page Ltd. Renumbered N2160-N2179.

N2305-N2307 3 BR80 May, Harding & May. Cancelled.

N2310-N2321 12 BR86 Malta Dockyard Renumbered N4310-N4321.

N2400-N2449 50 Bristol & Colonial Aeroplane Ltd Ordered 16.07.17, with 320-hp Rolls Royce engines. Cancelled, serials reallocated.

N4000-N4037 38 Short Bros Ltd. 11.07.18 All delivered. N4019 became G-EAQT.

N4100-N4149 11 38a/1090/C & AS4499/18 Dick, Kerr & Co Ltd. Contract for 11 F.3 & 39 F.5.

N4160-N4179 20 AS 11426; AS30303 & AS30620 (BR22) The Phoenix Dynamo Manufacturing Co Ltd All delivered. N4177 became G-EBDQ.

N4180-N4229 11 AS44496/18 (BR348) The Phoenix Dynamo Manufacturing Co Ltd Contract for 11 F.3 and 39 F.5. F.3 to N4190. N4191 E3 or F.5?

N4230-N4279 50 AS 13823 (BR72) Dick, Kerr & Co Ltd. Dick, Kerr’s first F.3s. N4268- N4273 & N4276-N4277 no record of delivery.

N4310-N4321 12 AS 14835 (BR86) Malta Dockyard. 20.03.18 All delivered from March 1918.

N4360-N4397 38 AS14835 (BR. Adm 1269) Malta Dockyard. 05.09.18 N4388-N4397 cancelled.

N4400-N4429 30 AS30620 (BR199) & AS4496/18 The Phoenix Dynamo Manufacturing Co Ltd. 07.02.18. Grain test.

Note that aircraft were not built in order of serial. Some batches with late serials were completed by a manufacturer before a batch with lower serials that were contracted to the same company.

Experimentation

An interesting experiment saw an F.2A and an F.3 (N4230) equipped with a hydrophone. The machine would alight and drop the hydrophone that was attached to a long rod on the side of the fuselage, into the water. The rod or stream-line strut according to the manual, was held to the hull by a bracket. The forward observer had headphones through which he would listen for the sounds of a submarine under water. Tests were carried out with the submarine C25 and N4230 in May 1918.

In August F.3 N4400 was undertaking trials of the Cooper servo-motor and the Cooper auto-flare night landing device “with new type stick.” A Cooper servo-motor was fitted to the aileron control system of N4400. This was tried with different windmills and that of the two bladed 22 inch diameter and 3 feet 6 inch pitch “was more satisfactory.” It was considered that the time taken to put the ailerons hard over should not exceed 1 1/2 seconds.

The “Stick Night Landing Device” was to give a positive signal to the pilot of the close approach of the surface of the water in time for the pilot to flatten out. A streamlined tapered shaft was mounted on a transverse shaft in the nose of the machine. The shaft could move in and out about a foot. When the spar was out of action it lay horizontally along the fin. In calm weather the device showed promise. A landing was made with the pilot keeping his eyes off the water. The signal to the pilot was considered not as distinct as it should have been. In bumpy weather the stick developed a violent lateral sway and this interfered with the accuracy of the warning and it looked as if the stick would eventually break off the shaft.

Experiments are being tried with a stiffer shaft and a rounded stick instead of streamlined. A streamlined stick of larger dimensions and not so whippy can also be tried. A good deal of experiment and practice will be necessary, but it is hoped that a satisfactory method will be arrived at.

Saunders was given a contract for two experimental F.2A hulls to take standard F.2A wings. The Technical Department report for the fortnight ending 12 June 1918, reported that one hull was finished and would now be fitted with standard F.2A wings and fittings. The following report noted that the progress on the second hull was satisfactory.

The F.3 was declared obsolete in September 1921, the F.2A and F.5 becoming the standard RAF flying boats.

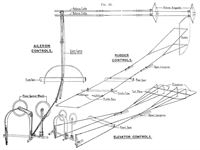

RAF Notes on the “F.2A, V.3 (sic) and F.5 Boat-Seaplanes, Eagle VIII Twin Engines” record that the throttle controls were on the starboard side of the first pilots cockpit on the F.2A and F.3, and the port on the F.5. It was noted that these “controls are not very sensitive owing to the fact that Bowden wire No. 11 is used, and they have a long run.”

The Engineer’s cockpit was situated between the main and rear spars in rear port side of the hull. The engineer had:

(i) Distant reading thermometers for each engine.

(ii) Radiator shutters that could be controlled by the engineer to regulate the temperature of the water.

(iii) A pump for pumping extra water to the radiators. An overflow pipe from the radiators came back to the tank that held about 1 1/2 gallons.

(iv) A Rolls-Royce dope pump with starting magnetos and “change over” switch.

The main fuel tanks were carried in the hull. The petrol system comprised a gravity tank in the upper wing that was kept full by means of a plunger type windmill pump. Petrol could be drawn from any tank by means of the pump and delivered to the gravity tank. Overflow was piped back to the main tanks. A hand plunger pump was fitted in the engineer’s cockpit and used when the machine was at rest or in an emergency when the windmill pump was inoperable.

On 30 November 1918, a trial was conducted with F.5 N86 with an overload of 12,800 lbs, being 1,000 lbs in excess of the

normal load.

With the wind about 8 mph and a smooth sea, a run of 57 seconds was made but the boat showed no signs of hydroplaning and continual heavy streams of spray were going through the airscrews. At the end of the run the starboard engine was vibrating so badly that it could not be run at full speed. Examining the blades of the airscrew it was found that the brass sheathing on the tips had bulged and filled with water causing the airscrew to become unbalanced. It was commented that a machine should be able to take off with at least 30% of normal load. This attitude has been noted in correspondence during the war when it was recorded that the machines would always be loaded with more gear after they entered service due to the demands of that service.

Felixstowe F.5

The prototype F.5, serial N90, appeared in early 1918. It was intended as an improvement over the F.3. A typical Porte construction it embodied a number of refinements. The cockpits were open improving the pilot’s backward view. The top decking of the hull was deeper while the gun positions were the same as the F.3. Aft of the wings the hull sides were fabric covered with a mahogany washboard on the lower half despite the problems with this arrangement on the F.2A. The F.5 hull was regarded as the best of all the Porte hulls. Bomb load was four 230-lb bombs on the underwing racks. The wing was similar to that of the F.2A and F.3 but of longer span and utilised a new aerofoil section and the horn balanced constant chord ailerons were used in place of the inversely tapered ailerons of the earlier boats, tail was essentially the same but the rudder had a balance surface. On official trials with two 350-hp Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII engines driving four-bladed airscrews the prototype, N50, had a better performance than the F.3, even in conditions of overload.

The problem of attaining and keeping aerial supremacy in the North Sea led to many suggestions as to the operation of the Large America flying boats as detailed in the accompanying text. The F.3 was included in these considerations. In July 1917, it was put forward by Cdr Longmore that a twin-engined fighting machine along the lines of the F.2A and F.3 was needed as an escort fighter for the formations of Large Americas operating in the North Sea. This new machine needed to be ready for trials when the new large calibre quick firing guns were ready for testing. The COW Automatic Gun appeared to be most promising. Porte stated that the F.5 that had just been laid down at Felixstowe could be adapted to carry two of these guns. The machine could be ready in about two months and would have a better performance than the F.3. The discussion then went on to consider whether such guns could also be used against submarines and the general opinion was that it was not possible to mount the gun such that it could perform both functions. Documentation that a COW gun was ever carried by an F.5 has not been discovered.

Unfortunately the Ministry of Munitions decided on economic grounds not to introduce the new type. The Ministry did not want to supply new jigs and templates now that the production of the F.3 was well underway, and so a compromise was reached. The production F.5 used a hull similar to the prototype but with as many F.3 components as possible and was planked overall. While a very strong hull it was appreciably heavier than that of N90. The F.5 wing was virtually identical with the F.3 wing reverting to the same RAF 14 aerofoil. The F.5 did have horn balanced ailerons of constant chord. Performance of the production model with Rolls Royce Eagle VII engines was inferior to that of the prototype. The Eagle VII was used as Eagle VIII engines were in short supply but this was not the only reason that the production machines were inferior to the prototype.

Like N90 the F.5 had a balanced rudder and later horn-balanced elevators. The F.5 had a typical Porte type hull with the lower centre section integral with the hull. The upper centre section was supported by two struts, one pair placed on the centre-line of the boat. The cabane struts supporting the engines were also attached to the upper and lower centre section planes. Considerable difficulty was experienced in removing the engines once the planes were in position as it was impossible to get a direct lift on them. Air Commodore Samson noting that “replacing an engine is not an easy job without getting the boat ashore, as of course in an ‘F.2.A.’ you have to remove the planes.” The Rigging Notes for the F.5 noted that “whenever the planes are dismantled advantage should be taken of the opportunity to overhaul the engines.”

The F.5 had flown before there were any tank test results. Maj J.D. Rennie recorded that the positions of the steps on the F.5 by Porte were the result of a great deal of practical experience in takeoff and landing boats in varying weather and sea conditions. Just before the Armistice work was put in hand to fit steps to the F.5 in accordance with tank test results but the work stopped due to demobilisation of staff.

Rennie then went on to state that the F.5 was never put into production, which was a great blunder on the part of the Production Dept, Ministry of Munitions. Instead, the F.3 wing structure, the weight considerably increased to facilitate production, and adapters fitted to take either streamline wires or stranded cables, also permanent slinging gear incorporated, was fitted to a mongrel hull, a cross between the F.5 and the F.3, and the resultant boat was called the F.5. This was done solely because the F.3 was already in production (it never should have been), and the Ministry of Munitions were against a further change as jigs, templates, etc., were already made for the F.3.

In August 1918 it was noted that a further batch of F.5 drawings were received from Dick Kerr that have been traced and included with the official set for issuing to contractors. The set of drawings for this machine were now near completion. It was recorded in January 1919 that the pulley bracket had been modified on as the controls were impossible to work with the present arrangement. Also that owing to the “present military situation” Liberty engines would not be installed in the F.5. Too late to be used operationally in the war, the F.5, along with the F.2A, became the RAF’s standard flying boat post-war until replaced by the Supermarine Southampton in August 1925.

F.5 Serial Allocation

Serials Number Contract Manufacturer Notes

N90 1 Felixstowe NAS. Prototype.

N128 F-5L ordered from USA post-war.

N177 1 Short Bros Ltd Metal hull with E5 aerostructure.*

N178 1 SE Saunders Ltd. Hollow hull with F.5 aerostructure*.

N4038-N4049 12 AS32421 Short Bros Ltd.

N4112-N4149 39 38a/1090/C & AS4499/18 (BR347) Dick Kerr & Co Original contract for 18 F.3 then 32 F.5, but F.3 to N4111 only. N4125-N4149 (10), cancelled?

N4192-N4229 39 AS4496/18 (BR348) The Phoenix Dynamo Manufacturing Co Ltd. Original Contract for 11 F.3 and 39 F.5. N4201-N4229 cancelled, but 10 superstructures completed & delivered.

N4580-N4629 50 38a/550/C563 &AS224911/18 (BR590) SE Saunders Ltd. N4580-N4589 no evidence. N4590-N4629 cancelled post-Armistice.

N4630-N4679 50 38a/552/C565 & AS24910/18. Gosport Aviation Co Ltd. N4640-N4679 Cancelled. N4634 became G-EAIK.

N4680-N4729 50 38a/599/C627 & A26345/18 (BR620) May, Harding & May. Cancelled December 1918.

N4730-N4779 50 38a/604/C633 & AS26344/18 (BR621) Dick Kerr & Co. To have Liberty engines. Cancelled December 1918.

N4780-N4829 50 38a/598/C628 & AS26343/18 (BR622) Phoenix Dynamo Co. Cancelled December 1918.

N4830-N4879 50 38a/600/C629 & AS26368/18 (BR623) Short Bros Ltd. N4880-N4879. Cancelled post Armistice.

* Robertson defines N177 and N178 as a basic F-5

Experiments

There were many experiments carried out on the America boats and some are referred to under the various type histories. One proposal was for the fitting of folding wings to the Large America boats. Handley Page had experience in folding wings on large aircraft such as the O/100, and had been approached to make folding wings for the flying boats to allow more hangar space. In September 1917, it was noted that difficulties had been found owing to one of the interplane struts fouling the tail when folded. Handley Page “could only get the folding dimensions down to 43 feet. If he could be allowed to space the engines out to 18 feet instead of the present 10 feet, he could reduce the folded dimensions to 35 feet. Although the spacing of 43 feet was considered adequate as it would allow for the machines to be hangared in a Bessoneau hangar, this project never came to a satisfactory conclusion. The company had received further orders for their bombers and were devoting their energies towards this instead of getting on with the seaplane work that they already had in hand.

Another interesting experiment concerned a set of Le Vaillant Speaking Tubes that were fitted to F.3 N4409. Several flights of from 314 to 414 hours were carried out. While it was found that a conversation could be easily carried out even with the engines running full out, there were disadvantages. The weight of the observer’s tubes caused a strain on his neck as a considerable length of tube had to be allowed for his movements around the cockpit. The gun ring could not be operated as the tubes caught up on various objects. “The apparatus would be of no use during an action.” The pilot was not inconvenienced to any extent with the tubes permanently attached to his helmet as the tubes were capable of being supported and he did not have to move about. They were not adopted for service us.

Around May 1919, a production F.5 made an endurance flight of 14 hours 8 minutes from Felixstowe. The crew was Capt Scott, as pilot, Capt Dickey, as navigator and two mechanics. No attempt was made to alight until the Eagle VIII engines stopped from lack of fuel. The total weight of the machine with crew was 13,710 lbs of which 150 lbs was water shipped in the choppy sea before takeoff. The average speed was 55 knots and wireless communication with Felixstowe was maintained throughout the flight.

Post-war the F.5 took part in many experiments. In early 1921 N4040 was fitted with a modified rudder with top balance, and tested against N4838 with the standard rudder to ascertain whether the standard F.5 rudder “was overbalanced and liable to take charge.” N4040 was flown by Flt Lt E.S. Goodwin with Wing Cmdr H.R. Busteed and Flt Lt D.E Lucking as observers. Unfortunately trials were not completed owing to engine trouble. Later flights were no more successful due to bumpy conditions. The lack of instrumentation to detect and record results was probably the reason that no recommendations were made.

In another experiment N4839 was fitted with two 450-hp Napier Lion engines. In Report MN271 of 16 August 1922, the test pilot, Flt Lt C.B. Dalison, AFC, recorded that the

seaplane is very nose heavy on climb but trims at nearly full throttle flying level low down at about 78 knots and 2000 r.p.m., under which conditions it flies “hands off’. The above with the maker’s tail setting.

To the rest of remarks regarding Stability and, Controllability and Manoeuvrability, the Report notes all “As Eagle 8.F.5.” No bombs could be carried externally due to position of docking chocks. It was considered that the poor performance was partly due to the excessive radiator size and the Vickers Vernon airscrews used for the test. “The engines are overloaded by the Vickers Vernon propellers.” It was considered that the “improvement in performance over that of the standard Eagle 8.F.5. is so far inconsiderable that no useful purpose would appear to be served by the present conversion scheme.”

There were two special F-boats. N178, that featured a deep Saunders hollow-bottom hull. This machine has standard F.5 wings rigged with a slight stagger. N177 followed with an all metal hull by Short Brothers and known by that firm as their S.2. The hull was an early metal monocoque and proved its strength when the machine was stalled into rough water from about 30 feet and remained undamaged and watertight.

Post-War

The British were anxious to catch as much of the post-war civil and military market as they could. Their main rival was France as the Germany aviation industry was hamstrung by the Allies. Two F.5 boats, N4041 and N4044, set out from Felixstowe on 11 July 1919. N4044 made a round Scandinavia flight of 2,450 sea miles in a flying time of 40 hours 40 minutes as a “demonstration of the commercial uses of flying-boats.” The flight was noteworthy that in the 27 days no kind of trouble was experienced and the low-compression Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII engines ‘worked magnificently throughout.” The flight took in Norway, Denmark and Sweden.

The ELTA Exhibition at Amsterdam in 1919 was to be a showpiece for aviation, especially civil aviation. Aircraft companies from all over Europe presented their products at the exhibition and passenger flights introduced the new method of transportation to the public.

Gosport built F.5 N4634 flown by Lt-Col Ralph Hope Vere was the first F-boat to attend the exhibition. Banned from flying by the British Air Ministry N4634 was only available to invited guests and was not available to the general public. To highlight the British presence Sir Fredrick Sykes, the Controller General of Civil Aviation, arrived with five RAF F.5 flying boats at the naval air station of Schellingwoude on 12 August. These flying boats returned to Britain the next day. F.2A boats N4439 and N4441 were flown to Holland for the ELTA exhibition with N4441 also giving demonstration flights. These two F.2A boats were presented as Vickers exhibits as S.E. Saunders had been taken over by Vickers.

Canada

Canada received eleven F.3 flying boats as part of the Imperial Gift of 1919. They were given civil registrations G-CYBT (N4016); G-CYDH (ex-N4009); G-CYDI (ex-N4010); G-CYDJ (ex-N4011); G-CYDQ(ex-N4014); G-CYEN (ex-N4015); G-CYEO (ex-N4181); and also N4012, N4013, N4178 and N4179 that did not receive civil registrations but were held as spares. A single Curtiss H-16 N4905 (G-CYEP) was included in the Gift but two ended up in Canada. The second was N4902 that was not registered and apparently used for spares. The US Government also gave the Canadians a number of Curtiss HS-2L flying boats that had operated from Nova Scotia during the war.

The flying boats were used for summer patrols over areas where forest fires could break out. By 1922 all the Canadian aircraft were worn out and had not been reconditioned. The last F.3 was withdrawn in 1923, their replacement was the Vickers Vedette that was designed for Canadian conditions and built in Canada by Canadian Vickers at Montreal.

Chile

The Chilean Navy acquired an assortment of British aircraft after the war as payment for the Chilean ships that were under construction in Britain at the declaration of war and were taken over by the British. Sopwith Baby and Short 184 seaplanes were received followed in 1920 by a single F.2A (ex-N4567). This boat had open cockpits and balanced ailerons. Commissioned on 17 October 1921, when it was christened with the name “Guardiamarina Zanartu” after the first naval pilot. It was replaced by the Dornier Wai in 1926 and made its last flight on 15 February 1928.

Japan

The Master of Sempill s British Naval Air Mission to Japan saw British aircraft purchased for use by the Japanese Navy. Before their arrival in April 1921, a small number of Avros and F.5 boats were ordered by Japan. The ten F.5 boats came from Short Brothers. The first to be erected was launched and flown on 30 August 1921, by John Parker. The F.5 “proved a valuable asset to the work of the Mission” and a number of long distance flights were made by trainees. It was the practice to finish each course with a cruise around the shores of Japan. The distance was usually over 1,500 miles and these took more than 9 hours to complete in stages, the longest stage usually being about 500 miles.

The F.5 was to be built in Japan, Short Brothers sending 20 personnel under engineer Dodds to Japan, the contingent arriving in April 1921. They worked at the Yokosuka Arsenals Ordnance Department. The Arsenal erected the imported F.5 boats with the first taking to the water in April 1921. British sources state that in 1922 three Short-built F.5 boats with Napier Lion engines were obtained from Britain.

An US intelligence report noted in March 1923 that two F-5 flying boats had just been completed at Yokosuka for the Naval Air Service at Sasebo. The aircraft were serialled 51 and 57. The first F.5 constructed entirely of local materials was built at the Hiro Naval Arsenal with assistance of Short Brothers personnel. Later some 50 E5 boats were built by the Aichi Tokei Denki Co of Nagoya. In 1925 the Hiro Arsenal powered an F.5 with licence-built 400-hp Lorraine engines, followed by another with 450-hp Lorraines. Designated F.1 and F.2, they were not selected for production as it was realised that the F.5 was outdated. Ten were built by the Hiro Naval Arsenal (Hiro Kaigun Kosho), ten by the Yokosuka Arsenal and forty by Aichi. Several impressive long-distance flights were made by the Japanese F.5 boats, some over nine hours. Some survived still in service in 1929. A report from the Naval Attache, Tokyo, on 18 January 1929, stated that 16 F-5 boats were in first line service with 6 in reserve. Although the type had a good history of service there were also many accidents mainly due to improper maintenance, engine problems and bad weather. Japan was to go on and build some of the best flying boats in the world culminating in the mighty Kawanishi H8K “Emily” of WWII fame.

Australia

Australia sought to obtain Short F.5 flying boats and the serial sequence A11 was allocated to the proposed boats but financial concerns led to the purchase being abandoned. Two wooden hulled Supermarine Southamptons were eventually obtained and they took up the A11 serial prefix.

Netherlands

As related in the text N4551 fell into the Netherlands hands. A number of Large America flying boats ended up in the Netherlands commencing with H-12 8693. This boat was delivered to Felixstowe on 3 June 1917, and was forced down due to engine failure on the 24th the following October. The Dutch torpedo boat G15 found the boat anchored in the Deurloo. The crew of Flt Lt H.C. Gooch, LM C.W. Sivyer and 2AM B.M. Millichamp were taken on board the torpedo boat whereupon the flying boat sank. Sources vary as to the fate of this machine with British sources saying the crew sank the boat, which appears to be most likely, while there is a suggestion in Dutch sources that there may have been a partial salvage of the machine.

Curtiss H-12 Convert 8689 was shot down by Germans and force to alight off the northern tip of the island of Vlieland on 4 June 1918. The machine managed to be run aground but before the crew could set the machine on fire they were prevented by the coast guard stationed on the island. The crew were all interned and the boat was impressed in the MLD as L.1. This day also saw Capt Dickeys F.2A N4533 shot up and set on fire on the water after alighting in Netherlands waters.

On 2 October 1918, F.2A N4551 of No.232 Squadron, RAF, was one of a flight of seven that flew along the Dutch coast within the Dutch territorial waters and were fired on by coastal batteries. Forced to alight, the boat was beached at Noordwijk. The crew were prevented from setting the boat on fire. This F.2A was taken into MLD service as L 2. According to a contemporary report three Canadian and two British men comprised the crew (Lt J.C. Stockman, 2/Lt T.N. Enright, 2/Lt W. Pendleton, 1AM H.L. Curtiss, and 3AM W.A. Mitchell). All were interned. Lt Stockman was injured in the incident, the rest were unhurt.

Portugal

In May 1920 two F.3 boats were reconditioned by Fairey Aviation Co Ltd at Hamble before being flown to Lisbon for the Servico de Avica (Naval Aeronautical Service). They were in service until 1922. One was used for the first flight from Lisbon to Funchal on Maderia Island in 1921. This 7 hour 40 minute flight was captained by Cdr Sacadura Cabral, with Capt Gago Coutinho as navigator. Cabral had flown the first of the boats from the UK to Lisbon. Coutinho was over 60 years of age and a well qualified navigator. This flight served to give them experience in navigation for the proposed first South Atlantic crossing the following year in a Fairy IIID.

Spain

When the Riff War began in Spanish Morocco the Army and Naval air service were poorly equipped and there was a rush to acquire new equipment. The Army purchased Bristol Fighters, De Havilland 9 and 9A bombers from the ADC. Although the war was mainly an Army affair, the Navy purchased 11 Felixstowe flying boats, variously referred to as F.3 and F.5 models from the ADC. Photographs show a cockpit canopy which would confirm that they were the F.3 model. They were erected, inspected, crated and shipped to Spain. As facilities were not available for their operation, the wings and tail sections were stored ashore while the hulls were placed on the davits of two old warships in Barcelona harbour, exposed to the sun and dew, a treatment for which they had not been designed. The first boat was wrecked while attached to its trolley in a gale the night before it was due to fly for the first time. For the story how they were brought into service see Norman Macmillans Freelance Pilot, Heinemann, London, 1937.

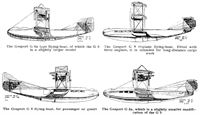

Post-War Civil

The Gosport Aviation Co on the Solent was building the F.5 and, according to H. Penrose, Porte had announced that he would be willing to join the company after the end of the war. Flight for 15 December 1919, devoted an article - “Some Gosport Flying Boats for 1920” to the company’s proposals. The article noted that the late John Porte had joined the company in August 1919 as Chief Designer, and had produced several designs based on his successful types in the late War modified to suit commercial requirements. The types are illustrated by drawings and their Felixstowe lineage can be clearly seen. The G.9 was a triplane flying boat based on the Fury and featuring the 600-hp Rolls Royce Condor engines that were to have originally powered the Fury. They were arranged with the two outboard engines as tractors and the central one as a pusher.

With his death on 22 October 1919, at only 35 years of age, Porte’s ideas for civilian versions of the F-boats died with him. Not one Gosport design was ever built. The North Atlantic was conquered by a flying boat in 1919 before he died. This was the USN NC-4, a design that was radically different from those designed by Porte, but one which he would have been aware of given the constant communication between Felixstowe, Curtiss and the USN. This is not to say that the Porte boats had no influence on civil aviation.

Major W.T Blake departed Croydon in a modified D.H.9 G-EBDE in an attempt to fly around the world on 25 May 1922. The original D.H.9 was lost in a crash and he continued his abortive world flight in a variety of aircraft. F.3 G-EBDQ was reportedly shipped to Canada for this part of his trip but was not used and later sold in Canada in 1922.

Short Brothers Ltd had hoped to sell their F.3 and F.5 boats on the civilian market but had to compete with the low prices from the Aircraft Disposal Co (ADC). In their advertisements Shorts offered their F.3 as an adaption of this machine for passenger work that turned it into a luxurious yacht. A cabin space 9 ft x 4 ft 6 in was fitted out as a lounge for four to six persons. If less comfort and luxury was required then a greater number of passengers could be carried. Two machines ended up on the British civil register as G-EAQT (ex-N4019) and G-EBDQ (ex-N4177), the latter, Blake’s machine, referred to above.

G-EAQT was converted to an air-yacht by Shorts and flew in this form on 28 May 1920. Lebbeus Hordern imported G-EAQT to Australia together with spare parts. In Australian documents it is referred to as a Short F.5 flying boat. The hull was launched but the machine was never erected. In 1923 the Superintendent of Aircraft received a report on the machine. The wings were still in their packing case. The hull was thought to require a considerable amount of repair before the machine would be considered airworthy as all the joints had opened up and the timber had warped badly. Hordern later donated the two Eagle VIII engines to the RAAF in 1927. According to legend the hull became a shelter for fishermen. The British registration had been cancelled in January 1921.

Some sources quote two F.3 boats used for an aerial service in Tasmania but no such service existed.

The Aircraft Disposal Co was still able to offer the following airworthy aircraft for sale in 1924:

Felixstowe F.3, Martinsyde F.4, D.H.9 and 9A, Bristol F.2B, Sopwith Snipe, Avro 504K and Parnall Panther.

Felixstowe F.2

The evolution of the F.1 and F.2 is described in Chapter 2. 8650 was reported as undergoing overhaul between 14 August and 4 September 1916, and it is likely this is the period it was fitted with the Porte hull. The combination of a new Porte hull with the H-12 wings and a new tail unit led to a better boat that was designated F.2 although it retained the serial 8650. With more powerful engines it was developed as the F.2A.

The F.2A Described

The hull was composed of four longerons with horizontal and vertical spacers braced by diagonals and steel cables. The planning bottom was constructed of two-ply cedar inside and mahogany outside. Varnished or doped fabric was sandwiched between the two layers. The bow, decking and cockpit framework was mahogany while the sides back to the trailing edge of the lower wings was birch plywood. The top of the hull behind the wings was fabric covered to save weight. A 12 inch deep mahogany washboard ran along the lower longerons. The front part of the hull as far back as the rear spar was a rigid built-up structure. From here to the rear the structure was a typical fuselage structure with doped fabric covering above the 12 inch solid mahogany washboard. This was to cause problems, and following the loss of H-16 N4510 on 8 April 1918, in heavy seas, due to the failure of the fabric sides on the tail of the boat, the USN recommended that this defect be corrected on all its H-16 in service. The fabric was to be replaced on some boats with ply sheeting. The fins were built onto the outside of the hull and were planked on the top with three-ply. The hull was double planked. Most WWI built aircraft show variations however the Felixstowe boats show more than others. This was due in part to the different manufacturers of hulls and the aerostructure being allowed considerable latitude and the modifications worked out in active service and applied at stations.

The hull was V-shaped and curved from bow to stern while the tail portion was raised such that it rose clear of the water when at rest. The side fins were built onto the outside of the hull. The planking was double diagonal comprising an inner layer of 1/2 inch cedar and an outer layer of 3/16 inch mahogany, the two with a layer of varnished fabric sandwiched between them. Sliding panels in the hull behind the wings allowed for a Gallows mounting for a Lewis Gun on each side. These could be swung outboard and covered the tail of the boat thus overcoming one of the H-12 defects. A pilot of the F.2A could alight in much rougher seas with less fear that the hull would be damaged, and he could take-off in rougher waters as it did not hammer the water to anything like the extent that the practically flat bottom of an H-12 did. This was despite the F.2A being designed by Porte to utilise the sheltered waters of harbours such as Harwich, the necessities of war calling for more from the boat than its designer intended.

The wings were a typical Curtiss wooden structure and plan form although the F.2A boats had ailerons that projected beyond the wing trailing edge. Late boats had open cockpits and balanced ailerons.

The decision to change from a 23 inch to 20 inch gun ring involved structural alterations and delayed production, the type entering service late in 1917. The number of Large America boats required for the 1918 program was estimated to be 180 in May 1917, and this was revised to 426 with the revised program of July 1917. The average life of the big boats was six months and therefore twice the number of boats was required to meet the estimated establishment figure. The entry of the US into the war and the USN’s agreement to take over and equip five naval air stations provided some relief to the situation as even with the Porte method of construction, it would have been impossible to produce the number of boats required. In March 1918, 161 F.2A and F.3 boats were on order, however only ten F.2A and one F.3 were in service.

The F.2A suffered with problems with its fuel system. The length of piping it contained ran from the main tanks in the hull where wind-driven pumps forced the fuel to the gravity tanks in the top wing centre section. From here the fuel was fed to the carburettors of the Eagle engines.

From about September 1918 all the new F.2A had open cockpits, the canopy being done away with. They were slightly faster as a consequence and the pilots had a better view backwards. The fabric was deleted from the rear of the hull and replaced with Consuta sewn ply. Horn balanced ailerons were introduced making them less tiring to fly. The F.2A had dual control unlike the H-12. The co-pilot’s control wheel folded enabling him to leave his position and access the front gun cockpit.

F.2A Serial Allocation

Serials Number Contract Manufacturer First Delivery Notes

N1260-N1274 15 AS3610 (BR17*) Curtiss, Canada. H-16. Presumed renumbered N4060-N4074.

N2280-N2304 30 AS 14154 (BR80) S.E. Saunders Ltd. Renumbered N4280-N4309.

N2530-N2554 25 AS21558 AMC Ltd. Renumbered N4530-N4554.

N4080-N4099 20 AS14154 S.E. Saunders Ltd. Delivered from late July 1918.

N4280-N4309 30 AS 14154 & AS34426 (BR80) S.E. Saunders Ltd. Delivered from mid-November 1917.

N4430-N4479 50 AS4498/18 (BR349) S.E. Saunders Ltd. 18.10.18 Some delivered as F.5s.

N4480-N4504 25 AS4502/18 (BR350) May, Harding & May 21.09.18 Erected by AMC Ltd. At least 21 delivered.

N4510-N4519 10 AS2697 May, Harding & May 12.01.18 Specification N.3B. Sunbeam engines contemplated for this batch.

N4520-N4529 10 AS24912 (BR74 & BR90) May, Harding & May Cancelled.

N4530-N2554 25 AS21558 May, Harding & May Erected by AMC Ltd?

N4555-N4559 5 AS24912 Cancelled.

N4560-N4579 20 38a/551/C564 & AS24912/18 (BR589) May, Harding & May Last seven cancelled.

The cost of an F.2A including hull and trolley, but without engine and armament was £6,738. Eagle VIII engines cost £1,622.10.00 each.

Felixstowe F.2C

At the 12 June 1917, Meeting of the Air Department Progress Committee, Cdr Longmore reported that the trials of the F.2C were being carried out at Felixstowe. The machine was to go to the Isle of Grain for testing. The F.2C was described as being similar to the H-12 “but has a different hull which is not quite so efficient as a hydroplane and has been found to be considerably better for landing as it has not the same inclination to leave the water again on being landed as the H.12 hulls have.” The F.2C had a hull of lighter construction and greater volumetric size than the F.2A and F.3, its proportions seemingly to anticipate the F.5. The hull had steps of revised design and the forebody’s contours were different from those of the F.2A. The pilot’s occupied an open cockpit. This was due to the fact that they had very little rear view in the canopied H-12 and F.2A rather than the usual answer that pilot’s preferred an open cockpit. The front gunner’s cockpit was farther back from the bow and there were no waist gun positions. Powered initially by two 275-hp Rolls-Royce Eagle II engines, these were later replaced by 322-hp Eagle VI engines. Official performance trials were held on 23 June 1917, and although performance was slightly better than the F.2A, there was no chance of it being placed into production and upsetting the F.2A program that was then underway, only the prototypes N64 and N65 were built.

N64 and N65 were sent to Felixstowe where they joined the War Flight. Porte led a patrol of five flying boats from Felixstowe in N65, his latest experimental boat, on 24 July 1917. His pilot was Queenie Cooper, the test pilot. This was the first time that Felixstowe had been able to field this many boats at once. They spent a long time getting into their correct position for take-off. In future this was to become common and they were got away easily.

Discovering a submarine on the surface, the patrol attacked. Three of the boats dropped bombs, including N65. The other two boats stood by but the submarine appeared to be finished. This submarine was incorrectly reported as UC-1.

While on a Beef Convoy patrol in late September 1917 Pix Hallam and Watson in N65 sighted a submarine and they immediately attacked. The F.2C was equipped “with a gadget for dropping bombs by compressed air, which, according to its proud inventor, was to supersede the good old way of dropping them by pulling a Bowen wire.” Unfortunately a good attack was ruined when the bombs hung up. The device hissed as compressed air escaped but the bombs refused to leave the racks. A nearby destroyer then attacked with depth charges.

N65 was written off after it was holed and sank at the Isle of Grain on 13 March 1918.

N64 was converted into an F.3 about October 1917. It was used for patrols and for experiments.

Felixstowe F.3

The F.3 was designed to meet the need to carry a larger bomb load as the 230-lb bomb was considered no longer satisfactory for attacking submarines. A Progress Committee Report of 12 June 1917, noted that all new “Americas” now on order would be of this type.

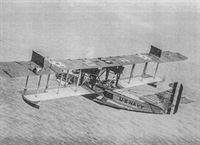

The F.3 actually preceded the F.2C. The F.3 had the same large overhang of the upper wing and king-post structure above the interplane struts. Its hull was three feet longer than the F.2A and the wing were of greater span and chord. These differences are not very noticeable in photographs and if the serial is not visible the only way to tell the difference is that the F.3 had a slight recess in the leading edge of the upper wing immediately behind the airscrews.

The F.3 had a typical Porte hull and was planked the same way as the F.2A. The fins were planked with three-ply birch. On later examples double diagonal planking was used. The floors of the F.3 were rebated into the keelson on either side and caused the planking to spring and the boats to leak badly. Intermediate timbers were introduced to try and overcome the problem. Sir A Robinson recalled that on

at least one station, where they often had to be bounced off a long swell, it was found that the planking was apt to open up from the keelson. A new boat on arrival would very probably be dismantled and the petrol tanks removed, to permit a series of oak knees to be put in to strengthen and hold together the bottom planking.

The F.3 could carry four 230-lb bombs while the F.2A could only carry two. This may be the reason that more F.3 boats were ordered than F.2A boats. Lt (later Major) J.D. Rennie was Porte’s Chief Technical Officer at Felixstowe and who assisted him in the development of the successful Felixstowe flying boats stated post-war that the F.3 should never have been put into production.

The prototype, the converted N64, was powered by two 320-hp Sunbeam Cossack engines. Production machines had Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII engines.

The F.2A boats went to Felixstowe, Yarmouth, Dundee, Calshot, and Killingholme, until that latter station was taken over by the USN and they began to receive Curtiss H-16 boats. The F.3 on the other hand went to Cattewater, and the Scillies, and to Houton Bay in the Orkneys. The reason for this was simple. The F.3 used the same Rolls Royce Eagle VIII engines that the F.2A used, was heavier and slower and less manoeuvrable and was unable to engage Zeppelins or German seaplanes. The F.2A went to those stations where reconnaissance and fighting was the most important, while the F.3 with their greater fuel capacity and bomb load went to stations where aerial opposition was less and hunting U-boats was more important.

The first operational flight of a F.3 was in July 1917. The type came in for modifications at the stations as had happened to the F.2A. The tail fabric would be replaced with ply sheeting. Sometimes the double bottom planking was put on the wrong way around so that the water flow was across the outer skin of planking and not along it. The bottom would be removed and replanked, a not infrequent activity according to Sir Austin Robinson.

A report on a Phoenix built boat, N4400, noted that:

1. The mahogany outer planks of the hull bottom aft of the step were buckling outwards, due to swelling. The planks were about 4 1/2 inches wide and were only secured along the joints, no intermediate copper clenched nails being employed.

2. Brass screws were freely used to fix the planking to the heavier framing timbers, and many were sunk too far into the outer planking. They should have been only slightly countersunk.

3. The footsteps were not correctly finished off to prevent water getting into the hull. “These should be boxed up on the inside of the hull to make the hull watertight.”

4. The interplane flying and landing cables were not correctly finished.

5. An elastic adjuster “will be fitted to the cloche for balancing the elevators, to replace the present crude arrangement.”

6. There was a great deal of sway between the hull and the main spars.

The report noted that the defects would be corrected at the station and suggested remedies for some problems.

In October 1918 the Technical Department of the RAF wrote to the Admiralty noting that problems with the hulls of flying boats was due to “lack of sufficient transverse strengthening members and incorrect method of fixing the plank on the bottom hulls.” While modifications had been introduced some three months back great difficulty had been experienced with hulls in store and they had been issued to the various “super-structure Contractors” who were not hull builders and had neither the expertise nor facilities to undertake the modifications required. Lack of accommodation and lack of the necessary facilities to carry out the modification work on stored hulls was blamed for the slow rate of production of modified hulls from store and the issuing of unmodified hulls.

The following report of 23 June 1918, from Houton Seaplane Station captures the problems present in the manufacture and operating of these large flying boats. Houton reported that none of its flying boats were fit for action as follows:

- N4245 Capsized on slipway in strong side wind.

- N4232 Sank on arrival and is being recaulked and fitted for service.

- N4406 Developed leaks in hull after 48 hours on the water. Sent to Houton from Stenness for repairs on 21 June.

- N4235 Sank on arrival and is being recaulked and fitted for service.

- N4403. Driven ashore in gale 13 June, bring repaired.

- N4230. Undergoing its first fitting out on arrival.

These were all F.3 boats. The Station also had Porte Baby 9810 that had been driven ashore in the 13 June gale. It had yet to be floated, a special slipway and cradle were being constructed for that purpose.

This unsatisfactory state was due to:

1. The station not being fully completed for service.

2. The machines being leaky and not ready for service when they arrive.

3. The bad weather in June.

4. A severe epidemic of influenza at Houton.

The majority of men on the station were recruits of one or two months service and had no experience of repairing or handling Large America, seaplanes. Only one shed had been available and that provided accommodation for only one seaplane, and all fitting out and repair of other machines had to be done in the open. Two cases of the aircraft breaking adrift of their moorings were due to the moorings being at fault, however the gale was a sever one and the F.3 boats were larger than the Porte Boat for which the moorings had been designed.

Only one seaplane arrived equipped with W/T. All others had to be wired up by station staff and this took about three weeks.

A Report of 23 May 1917, had noted that the Large America seaplanes had proved most satisfactory for submarine patrol work and large numbers would be used in Home Waters in 1918. The greater part of the establishment of 180, if not the whole output, would be needed for Home. It was considered that it was inevitable that these machines would be required for the Mediterranean, particularly in connection with the Otranto barrage. As this establishment was thought to be the output available from the UK and America, it was proposed that the boats for the Mediterranean be built in Malta under Dockyard control.28 The Air Department Progress Committee had already considered this at its Meeting on 15 May. At this Meeting it was suggested that it might be possible to have the hulls built in Malta and as the Maltese carpenters were expert boat builders, there should be no difficulty in turning out first class hulls. The wings would be built in the UK and shipped out for erection at Malta. All F.2A boats were used in home waters however the F.3 was used extensively in the Mediterranean. The F.3 was to be built in Malta. The local craftsmen were skilled boat-builders and local women did the fabric work.

In November 1917 Malta reported that work on wings for F.3 boats was practically at a standstill. The next day another telegram noted that the two Rolls Royce engines “just received for the first boat” were 345-hp. They also requested a full set of F.3 drawings for the 360-hp Rolls Royce engine. By January 1918 Malta reported that some of the Silver Spruce sent for main spars was defective and required 300 feet run 4 inch planks in 32 feet lengths to be sent by quickest means “to complete 12 boats.” A total of 18 F.3 boats were built in Malta.

The F.3 saw service in the Mediterranean and in September 1918, three F.3 boats flew from Malta to Tripoli where they bombed a wireless station on the Gulf of Sirte suspected of communicating with U-Boats. This operation took place over three or four days. In October the type accompanied the naval attack on Durazzo in Albania.

F.3 Serial Allocation

Serials Number Contract Manufacturer First Delivery Notes

N64 1 BRI 17 Felixstowe NAS Completed as F.2C, converted to F.3.

N1950-N1959 10 AMC Ltd Cancelled.

N2160-N2179 20 AS 11426 (BR22) Handley Page Ltd. Renumbered N2160-N2179.

N2305-N2307 3 BR80 May, Harding & May. Cancelled.

N2310-N2321 12 BR86 Malta Dockyard Renumbered N4310-N4321.

N2400-N2449 50 Bristol & Colonial Aeroplane Ltd Ordered 16.07.17, with 320-hp Rolls Royce engines. Cancelled, serials reallocated.

N4000-N4037 38 Short Bros Ltd. 11.07.18 All delivered. N4019 became G-EAQT.

N4100-N4149 11 38a/1090/C & AS4499/18 Dick, Kerr & Co Ltd. Contract for 11 F.3 & 39 F.5.

N4160-N4179 20 AS 11426; AS30303 & AS30620 (BR22) The Phoenix Dynamo Manufacturing Co Ltd All delivered. N4177 became G-EBDQ.

N4180-N4229 11 AS44496/18 (BR348) The Phoenix Dynamo Manufacturing Co Ltd Contract for 11 F.3 and 39 F.5. F.3 to N4190. N4191 E3 or F.5?

N4230-N4279 50 AS 13823 (BR72) Dick, Kerr & Co Ltd. Dick, Kerr’s first F.3s. N4268- N4273 & N4276-N4277 no record of delivery.

N4310-N4321 12 AS 14835 (BR86) Malta Dockyard. 20.03.18 All delivered from March 1918.

N4360-N4397 38 AS14835 (BR. Adm 1269) Malta Dockyard. 05.09.18 N4388-N4397 cancelled.

N4400-N4429 30 AS30620 (BR199) & AS4496/18 The Phoenix Dynamo Manufacturing Co Ltd. 07.02.18. Grain test.

Note that aircraft were not built in order of serial. Some batches with late serials were completed by a manufacturer before a batch with lower serials that were contracted to the same company.

Experimentation

An interesting experiment saw an F.2A and an F.3 (N4230) equipped with a hydrophone. The machine would alight and drop the hydrophone that was attached to a long rod on the side of the fuselage, into the water. The rod or stream-line strut according to the manual, was held to the hull by a bracket. The forward observer had headphones through which he would listen for the sounds of a submarine under water. Tests were carried out with the submarine C25 and N4230 in May 1918.

In August F.3 N4400 was undertaking trials of the Cooper servo-motor and the Cooper auto-flare night landing device “with new type stick.” A Cooper servo-motor was fitted to the aileron control system of N4400. This was tried with different windmills and that of the two bladed 22 inch diameter and 3 feet 6 inch pitch “was more satisfactory.” It was considered that the time taken to put the ailerons hard over should not exceed 1 1/2 seconds.

The “Stick Night Landing Device” was to give a positive signal to the pilot of the close approach of the surface of the water in time for the pilot to flatten out. A streamlined tapered shaft was mounted on a transverse shaft in the nose of the machine. The shaft could move in and out about a foot. When the spar was out of action it lay horizontally along the fin. In calm weather the device showed promise. A landing was made with the pilot keeping his eyes off the water. The signal to the pilot was considered not as distinct as it should have been. In bumpy weather the stick developed a violent lateral sway and this interfered with the accuracy of the warning and it looked as if the stick would eventually break off the shaft.

Experiments are being tried with a stiffer shaft and a rounded stick instead of streamlined. A streamlined stick of larger dimensions and not so whippy can also be tried. A good deal of experiment and practice will be necessary, but it is hoped that a satisfactory method will be arrived at.

Saunders was given a contract for two experimental F.2A hulls to take standard F.2A wings. The Technical Department report for the fortnight ending 12 June 1918, reported that one hull was finished and would now be fitted with standard F.2A wings and fittings. The following report noted that the progress on the second hull was satisfactory.

The F.3 was declared obsolete in September 1921, the F.2A and F.5 becoming the standard RAF flying boats.

RAF Notes on the “F.2A, V.3 (sic) and F.5 Boat-Seaplanes, Eagle VIII Twin Engines” record that the throttle controls were on the starboard side of the first pilots cockpit on the F.2A and F.3, and the port on the F.5. It was noted that these “controls are not very sensitive owing to the fact that Bowden wire No. 11 is used, and they have a long run.”

The Engineer’s cockpit was situated between the main and rear spars in rear port side of the hull. The engineer had:

(i) Distant reading thermometers for each engine.

(ii) Radiator shutters that could be controlled by the engineer to regulate the temperature of the water.

(iii) A pump for pumping extra water to the radiators. An overflow pipe from the radiators came back to the tank that held about 1 1/2 gallons.

(iv) A Rolls-Royce dope pump with starting magnetos and “change over” switch.

The main fuel tanks were carried in the hull. The petrol system comprised a gravity tank in the upper wing that was kept full by means of a plunger type windmill pump. Petrol could be drawn from any tank by means of the pump and delivered to the gravity tank. Overflow was piped back to the main tanks. A hand plunger pump was fitted in the engineer’s cockpit and used when the machine was at rest or in an emergency when the windmill pump was inoperable.

On 30 November 1918, a trial was conducted with F.5 N86 with an overload of 12,800 lbs, being 1,000 lbs in excess of the

normal load.

With the wind about 8 mph and a smooth sea, a run of 57 seconds was made but the boat showed no signs of hydroplaning and continual heavy streams of spray were going through the airscrews. At the end of the run the starboard engine was vibrating so badly that it could not be run at full speed. Examining the blades of the airscrew it was found that the brass sheathing on the tips had bulged and filled with water causing the airscrew to become unbalanced. It was commented that a machine should be able to take off with at least 30% of normal load. This attitude has been noted in correspondence during the war when it was recorded that the machines would always be loaded with more gear after they entered service due to the demands of that service.

Felixstowe F.5

The prototype F.5, serial N90, appeared in early 1918. It was intended as an improvement over the F.3. A typical Porte construction it embodied a number of refinements. The cockpits were open improving the pilot’s backward view. The top decking of the hull was deeper while the gun positions were the same as the F.3. Aft of the wings the hull sides were fabric covered with a mahogany washboard on the lower half despite the problems with this arrangement on the F.2A. The F.5 hull was regarded as the best of all the Porte hulls. Bomb load was four 230-lb bombs on the underwing racks. The wing was similar to that of the F.2A and F.3 but of longer span and utilised a new aerofoil section and the horn balanced constant chord ailerons were used in place of the inversely tapered ailerons of the earlier boats, tail was essentially the same but the rudder had a balance surface. On official trials with two 350-hp Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII engines driving four-bladed airscrews the prototype, N50, had a better performance than the F.3, even in conditions of overload.

The problem of attaining and keeping aerial supremacy in the North Sea led to many suggestions as to the operation of the Large America flying boats as detailed in the accompanying text. The F.3 was included in these considerations. In July 1917, it was put forward by Cdr Longmore that a twin-engined fighting machine along the lines of the F.2A and F.3 was needed as an escort fighter for the formations of Large Americas operating in the North Sea. This new machine needed to be ready for trials when the new large calibre quick firing guns were ready for testing. The COW Automatic Gun appeared to be most promising. Porte stated that the F.5 that had just been laid down at Felixstowe could be adapted to carry two of these guns. The machine could be ready in about two months and would have a better performance than the F.3. The discussion then went on to consider whether such guns could also be used against submarines and the general opinion was that it was not possible to mount the gun such that it could perform both functions. Documentation that a COW gun was ever carried by an F.5 has not been discovered.

Unfortunately the Ministry of Munitions decided on economic grounds not to introduce the new type. The Ministry did not want to supply new jigs and templates now that the production of the F.3 was well underway, and so a compromise was reached. The production F.5 used a hull similar to the prototype but with as many F.3 components as possible and was planked overall. While a very strong hull it was appreciably heavier than that of N90. The F.5 wing was virtually identical with the F.3 wing reverting to the same RAF 14 aerofoil. The F.5 did have horn balanced ailerons of constant chord. Performance of the production model with Rolls Royce Eagle VII engines was inferior to that of the prototype. The Eagle VII was used as Eagle VIII engines were in short supply but this was not the only reason that the production machines were inferior to the prototype.

Like N90 the F.5 had a balanced rudder and later horn-balanced elevators. The F.5 had a typical Porte type hull with the lower centre section integral with the hull. The upper centre section was supported by two struts, one pair placed on the centre-line of the boat. The cabane struts supporting the engines were also attached to the upper and lower centre section planes. Considerable difficulty was experienced in removing the engines once the planes were in position as it was impossible to get a direct lift on them. Air Commodore Samson noting that “replacing an engine is not an easy job without getting the boat ashore, as of course in an ‘F.2.A.’ you have to remove the planes.” The Rigging Notes for the F.5 noted that “whenever the planes are dismantled advantage should be taken of the opportunity to overhaul the engines.”