А.Шепс Самолеты Первой мировой войны. Страны Антанты

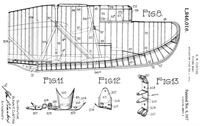

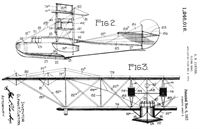

Лодка эта строилась с целью осуществления перелета через Атлантику и получения приза в 10 тысяч фунтов стерлингов, установленного английской газетой "Дейли Мейл". Однако с началом мировой войны перелет отменили. Два самолета с двигателями "Кертисс" OX-5 мощностью до 90 л. с. были закуплены британским Адмиралтейством для RNAS. Двенадцать следующих машин были доставлены в Англию без двигателей, а на первых двух машинах к двум толкающим двигателям OX-5 добавили еще один тянущий. На британской базе Феликстоу на самолеты устанавливали либо два 6-цилиндровых, жидкостного охлаждения, рядных двигателя "Бердмор" по 120л. с., либо два 10-цилиндровых, воздушного охлаждения, звездообразных "Анзани" по 100 л. с., либо два 12-цилиндровых, жидкостного охлаждения, рядных, V-образных "Санбим" по 150л. с. Эти машины получили обозначение Н-4 "Америка". Конструкция лодки была цельнодеревянная, с фанерной обшивкой. Эти самолеты одними из первых зарубежных машин получили закрытую комфортабельную кабину. Лодка была слабокилеватая с сильно развитыми скулами. Крыло двухлонжеронное, изготавливалось из дерева и обтягивалось полотном. Развитые элероны устанавливались на верхнем крыле. Для обеспечения необходимой жесткости над верхним крылом устанавливались шпренгели. Оперение обычного типа, с килем и стабилизатором, поднятым над лодкой на стойках и растяжках. Руль поворота имел роговую компенсацию. Двигатели устанавливались на металлических стойках между крыльями. В зависимости от мощности двигательной установки самолеты могли нести от 90 до 180 кг бомб. Командование, пользуясь способностью машины более 16 часов находиться в воздухе, использовало ее для борьбы с немецкими подводными лодками. Самолеты с 90-100-сильными двигателями получили название "Америка 950", ас 150-160-сильными - "Америка Импрувд". В конце 1915 года Адмиралтейство заказало еще 50 машин, так как полученных ранее не хватало. После того как в 1917 году фирма выпустила более крупный самолет H-12, а затем и H-16, названные "Ладж Америка" (большая Америка), самолеты Н-4 стали называть "Смолл Америка" (маленькая Америка). Не дожидаясь получения самолетов из Америки, англичане на базе "Феликстоу" наладили выпуск лодок по образцу Н-4. Самолеты эти получили обозначение Феликстоу F.1 (было построено 8 машин). Всего на британском флоте эксплуатировалось 70 машин Н-4, из них 62 построены фирмой "Кертисс". Эти машины были заказаны и для российского флота, но получены были только две штуки, одна из которых была разбита при сдаточных испытаниях.

Показатель Кертисс Н-4, 1914г.

Размеры, м:

длина 11,29

размах крыльев 23,09

высота 4,87

Вес, кг:

максимальный взлетный 2260

пустого 1356

Двигатель: "Кертисс" OX-5

число х мощность, л.с. 2x100

Скорость, км/ч 97

Дальность полета, км 1160

Экипаж, чел. 3

Вооружение 108 кг бомб

P.Bowers Curtiss Aircraft 1907-1947 (Putnam)

Model H America. The Model H twin-engined flying-boat originated at the request of Rodman Wanamaker, wealthy owner of department stores in New York and Philadelphia, who sought to win the ?10,000 (then 50,000 US dollars) prize offered by the British newspaper The Daily Mail for the first aerial crossing of the Atlantic Ocean. The Curtiss organization was the logical one to develop the required aeroplane, which the patriotic Mr Wanamaker had already named America, and an order for two machines was placed in August 1913.

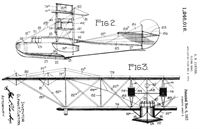

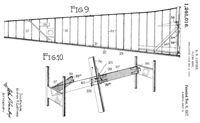

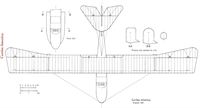

In form, the Model H followed the layout of previous Curtiss flying-boats, but it was enlarged in order to carry the fuel needed for a flight of 1,100 miles, the longest leg of the proposed transatlantic flight, and had two 90 hp Curtiss OX engines mounted as pushers. To increase their comfort, the two pilots and the mechanic were seated in an enclosed cabin. The wings, with two bays of struts on each outer panel, had tapered ailerons built into the upper wing, which also had a large overhang. The wings, which became the pattern for subsequent multi-engined flying-boats and their British-built counterparts for the coming war years, were designed by B. Douglas Thomas. Thomas was assisted to a considerable degree by another Briton, Lt John C. Porte, then on leave from the Royal Navy, who was selected by Wanamaker to pilot the America.

Since the Wright patent suit was active at the time, Curtiss sought to avoid duplicating certain details of the Wright system. The ailerons were hooked up so that only one worked at a time, one being pulled down by the action of the pilot's foot instead of both being moved in opposite directions by a control wheel. The wheel control was used to operate the rudder.

Following naming ceremonies on 22 June, 1914, the America began an extensive test programme. One of the early troubles was the tendency of the bow to submerge as power was applied to the engines. The high thrust-line of the engines applying forward force and the water drag on the hull acting in the opposite direction created a downward force on the bow. This phenomenon had not been significant in the past because of the relatively low power available in the smaller single-engined flying-boats.

The need for more forward buoyancy in the hull was met first by adding planing surfaces to the sides of the hull forward of the step. These were soon replaced by additional structures that Curtiss called 'fins' attached to each side of the hull, above the chines, that increased the volume and buoyancy of the hull as well as adding planing area. This Curtiss-developed feature was to be used on many other flying-boats into the 1930s but were called sponsons rather than fins.

With its take off problems solved, the America still could not carry the required fuel load for the distance, and the lifting capacity was then increased by adding a third engine to the top of the wing in a tractor position.

With the America finally considered to be ready, the oft-postponed flight was scheduled for 5 August, 1914, with Lt Porte as pilot. The starting point was to be St John's, Newfoundland, with intermediate stops at Fayal and San Miguel in the Azores and on to Portugal. Crews had actually been dispatched to some of these points when the flight was cancelled by the outbreak of what was to become the Great War, or World War 1 to later historians.

Lt Porte was recalled to duty in the United Kingdom and was able to persuade the Admiralty to purchase the America and its sister ship. These were to become the prototypes of a long line of twin-engined biplane flying-boats that would serve Britain and the US Navy well into World War II. The original America, in fact, gave its name to the class, and later developments up to H-16 sold to Britain became known as Small Americas and Large Americas.

Model H America

Three crew.

Span 74 ft (22,55 m) upper, 46 ft (14 m) lower; length 37 ft 6 in (11,43 m); height 16 ft (4,87 m).

Empty weight 3,000 lb (1,360 kg); gross weight 5,000 lb (2,268 kg).

Maximum speed 65 mph (104,6 km/h); range 1,100 miles (1,770 km).

Powerplant two 90 hp Curtiss OX.

RNAS serial numbers: 950, 951 (Curtiss prototypes), 1228/1235 (8, Aircraft Manufacturing Co, UK), 1236/1239 (4, Curtiss), 3545/3594 (50, Curtiss).

Model H Series (Model 6)

The Curtiss twin-engined flying-boat line that started with the America in 1914 continued into 1918 with designations in the H-series up to H-16. Only seven of the designations from H to H-16 are known to have been carried by existing aircraft. In the 1935 system, Model 6 applied to H-4, 6, 7,8, and 10, but details are not available.

Until the introduction of the H-12, the only customer was Britain's Royal Naval Air Service. Curtiss's lead in large flying-boat development was a notable exception to the state of American aviation in the 1915-17 period, when European designs made great advances under the stimulation of war requirements while America, isolated from these developments, fell farther and farther behind.

Even so, the design of the Curtiss hulls demonstrated notable structural and hydrodynamic deficiencies in British wartime service. Late in 1915, Lt Porte, now back in uniform, designed and built improved hulls and fitted them with standard Curtiss wings and tails. The improvements proved desirable, and the F-series of large flying-boats was produced with the new hulls and British-built Curtiss wings to become the standard patrol/bomber flying-boat of the RNAS and the later Royal Air Force. The final F-5 model was to be built in the United States by Curtiss in 1918 in parallel with Curtiss's own Model H-16.

H-4 (Model 6) - The designation H-4 was assigned to the original America after modification in Britain. Subsequent production versions were identified in RNAS service as the Small Americas. As built by Curtiss, the powerplants were two 90 hp Curtiss OX installed as tractors. These were not favoured by the RNAS, which substituted ten-cylinder 100 hp French Anzani air-cooled radial engines or two 130 hp British Clerget rotary engines for the water-cooled Curtiss types.

Curtiss built sixty-two H-4s including the prototypes and another eight were built in the United Kingdom by the Aircraft Manufacturing Company (Airco) and Saunders.

RNAS serial numbers: 882, 883, 950, 951,1232/1239 (Built by Aircraft Manufacturing Company and Saunders),3454/3594.

H-8 - No data available other than published photographs that show it to be a twin pusher slightly smaller than the America and powered with the same Curtiss OX engines.

H-14 - The H-14 was a smaller twin-engined flying-boat than the H-12 and reverted to the pusher engine arrangement of the original America. The US Army ordered sixteen examples, serial numbers 396/411, before the prototype was completed late in 1916. This did not come up to expectations and work on the Army machines was halted.

In mid-1917, the prototype was converted to a single-engined type with 200 hp Curtiss V-X-3 engine and was redesignated HS-1 (H-model with single engine). The Army having cancelled its order, the sixteen former H-14s were completed for the Navy in the HS-1 configuration and delivered with Navy serial numbers A800/A815 and new Liberty engines that resulted in the designation HS-1L.

H-14

Powerplant two 100 hp Curtiss OXX-2.

Span 55 ft 9 5/32 in (16,99 m)(upper), 45 ft 9 5/32 in (13,94 m) (lower); length 38 ft 6 5/8 in (11,75 m); wing area 576 sq ft (53,51 sq m).

Empty weight 3,130 lb (1,420 kg); gross weight 4,230 lb (1,919 kg).

Maximum speed 65 mph (104,6 km/h); climb 2,000 ft (610 m) in 10 min.

G.Duval British Flying-Boats and Amphibians 1909-1952 (Putnam)

Porte/Felixstowe F.1 (1915)

John Cyril Porte was invalided out of the Royal Navy in 1911, a victim of pulmonary tuberculosis, which in those days meant severe disability and premature retirement. Porte, however, had other ideas. During his Service career he had been actively interested in aviation, and this he resolved to continue. On 28 July, 1911, he gained his aviator’s certificate with the Aero Club de France, flying a Deperdussin monoplane, shortly afterwards becoming a partner and test pilot of the newly formed British Deperdussin Company. This company broke up in 1913, by which time Porte had achieved a considerable reputation as a skilled pilot, notably by his demonstrations at the weekend Hendon air displays. In the autumn of 1913 he joined the White and Thompsons Company as test pilot, gaining his first experience of flying-boats in October, when, with Gordon England, he went to Volk’s Seaplane Base on Brighton beach to meet Glenn Curtiss and to be given demonstration flights in the Curtiss machine purchased by Captain Ernest Bass, an ex-member of the Deperdussin Company. Further experience followed soon after this, when White and Thompsons were commissioned to maintain the Curtiss machine and secured the British rights to build similar aircraft under licence.

In early 1914, Curtiss began work in America upon a large twin-engined flying-boat capable of flying the Atlantic, this project being financed by Rodman Wanamaker, and Porte was offered the honour of piloting the machine. He accepted immediately, sailing to America on the first available passage. The machine was completed in record time, being launched in June 1914 and named ‘America’. Initial tests were carried out on Lake Keuka and were quite successful, but when fully loaded its 90 h.p. engines were unequal to the task, and Porte could not coax it oif the water. Work began at once on its modification to take more powerful engines, but the outbreak of war intervened, and on 4 August, 1914, Porte sailed for England, being at once accepted into the R.N.A.S. on his arrival, despite his disability. Soon after, Porte saw Captain Murray Sueter, the Director of the Air Department of the Admiralty, and gave him details of the ‘America’ flying-boat. Captain Sueter, fully aware of the problems involved in countering U-boat and Zeppelin attacks, and already largely responsible for the purchase of the F.B.A. and Sopwith flying-boats, immediately obtained Admiralty sanction for the purchase of ‘America’ and one sister-ship. They were delivered in November 1914, serialled Nos. 950 and 951, and sent to Felixstowe for testing, where they received the official designation of Curtiss H.4. A favourable test report resulted in a further order for a small batch of the type, Curtiss delivering four, and eight being constructed under licence by the Aircraft Manufacturing Company in this country. However, the 90 h.p. Curtiss engines left much to be desired, as Porte had already discovered; consequently five H.4s were re-engined with 100 h.p. Anzani radials, which gave a reasonable performance.

<...>

SPECIFICATION

Power Plant:

F.1 - Two 150 h.p. Hispano-Suiza

H.4 - Two 90 h.p. Curtiss, or two 100 h.p. Anzani

Span: F.1 and H.4 - 72 feet

Length:

F.1 - 39 feet 2 inches

H.4 - 35 feet

Weight Loaded:

H.4 - 4,983 pounds

Total Area: F.1 and H.4 - 842 square feet

Max. Speed:

F.1 - 85 m.p.h.

H.4 - 75 m.p.h.

Endurance: Not available

Armament: F.1 and H.4 - One or two Lewis guns, light bombs only

O.Thetford British Naval Aircraft since 1912 (Putnam)

Curtiss H.4 Small America

The H.4 was the first of the Curtiss flying-boats acquired from the USA to enter service with the RNAS. The firm of Curtiss had been the first to produce a successful flying-boat, which flew on 12 January 1912, and in the following year a British agency for Curtiss boats was acquired by the White and Thompson Company of Bognor, Sussex. It was in this way that John Porte, whose name is synonymous with the development of flying-boats for the RNAS during the First World War, first came into contact with Curtiss types and soon afterwards joined the parent company in the USA, for in 1913 he was the White and Thompson Company's test pilot.

If the World War had not intervened, John Porte was to have flown the Atlantic in a flying-boat named America. In the event, he re-joined the RNAS as a squadron commander in August 1914 and persuaded the Admiralty to purchase two Curtiss flying-boats (Nos.950 and 951), which were delivered in November 1914. These boats were tried out at Felixstowe air station and were followed by 62 production aircraft, four of which (Nos.1228 to 1231) were built in Britain. Curtiss supplied an initial batch of eight (Nos.1232 to 1239) and a second of 50 (Nos.3545 to 3594). The entire series was given the official designation H.4 and acquired the name Small America, retrospectively, after the introduction later of the larger H.12, or Large America.

Despite numerous deficiencies such as poor seaworthiness, the H.4 boats saw operational service. More important, however, was the contribution they made to the evolution of flying-boats generally as a result of the experiments they underwent at the hands of John Porte, a designer and innovator of genius. The H.4s so employed were Nos.950, 1230, 1231,3545,3546 (the 'Incidence Boat'), 3569 and 3580. Various hulls and planing bottoms were tried to improve take-off and alighting characteristics. This knowledge was put to good use in the later Curtiss and Felixstowe flying-boats.

A few H.4 flying-boats were still in service as late as June 1918 when, it is recorded, Nos.1232, 1233 and 1235 were at Killingholme coastal air station.

TECHNICAL DATA (CURTISS H.4)

Description: Reconnaissance flying-boat with a crew of four. Wooden structure with wood and fabric covering.

Manufacturers: Curtiss Aeroplanes and Motors Corporation, Buffalo, Hammondsport. NY. Sub-contracted by Aircraft Manufacturing Co in Great Britain.

Power Plant: Variously, two 90 hp Curtiss, two 100 hp Curtiss, two 150 hp Sunbeam or two 100 hp Anzani.

Dimensions: Span, 72 ft 0 in. Length, 36 ft 0 in. Height, 16 ft 0 in.

Weights: Empty, 2,992 lb. Loaded, 4,983 lb.

Performance: Not available.

Armament: Flexibly-mounted machine-gun in bows and light bombs below the wings.

C.Owers The Fighting America Flying Boats of WWI Vol.1 (A Centennial Perspective on Great War Airplanes 22)

1. The Development of the America Flying Boats

It is often stated that no US designed and built aircraft saw active service in World War I. What is not generally recalled is that US Curtiss flying boats were in use by the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) of Britain before the US entered the war. These flying boats carried out anti-submarine and anti-Zeppelin patrols over the North Sea and were frequently engaged in combat with German floatplanes.

On Bleriot’s successful flight across the English Channel, the British newspaper publisher, Alfred Harmsworth, (better known as Lord Northcliffe), is reputed to have stated, “England is no longer an island”. He was aware of the importance of aviation and the effect that German airships could have on England in the event of a war. He foresaw that the flying boat offered a solution to the problems with operating long-range aircraft in those days of low power engines. On April 1, 1913, Northcliffe's London Daily Mail announced a prize for the first flight across the Atlantic Ocean. The rules allowed 72 hours for the flight and the aircraft would be allowed to land for repairs and refuelling. The flight crew could board a surface vessel as long as they recommenced the flight no further advanced than when they landed. The flight could be from anywhere in the British Isles to or from anywhere in North America. It was to be hoped that the prize would promote real progress in aircraft design.

Glen Curtiss was the foremost builder of seaplanes at the time and he was approached by Rodman Wanamaker, heir to the Philadelphia mercantile fortune, to build an aircraft to make the flight. In September 1913, Curtiss left for Europe to make arrangements for the licensed sale of his aircraft. In England he met John Cyril Porte, late of the Royal Navy. Porte had been invalided out of the submarine service with tuberculosis in 1911. Porte had been invited by Captain Ernest C Bass, a wealthy young Englishman, to join a syndicate to build/market Curtiss flying boats in the United Kingdom (UK). Bass gained the sole agency for Curtiss flying boats and engines in Europe, and in February 1914, transferred this to the White and Thompson Co. The latter set up a flying boat school and Porte was appointed flying instructor. It appears that Curtiss was impressed by Porte’s flying of the Curtiss boat.

John Cyril Porte was born on February 26, 1884, at Bandon, County Cork Ireland. The son of an Irish clergyman, the vicar of Denmark Hill, he was the fourth child of seven children. Educated at private schools he joined HMS Britannia, the Royal Naval College at Dartmouth, at the age of 14, leaving at the end of December 1899. He then went to sea on HMS St George in January 1900. He remained at sea in various ships until February 1902 when, as a Sub-Lieutenant, he went to the Royal Naval College, Greenwich. In January 1904 he left Greenwich for the college at Portsmouth, leaving here in March the same year. Returning to sea in HMS Royal Oak, he remained at sea until Christmas 1904.

In February 1905, the same month he joined the Submarine Service, he was promoted to Lieutenant. He remained in the Service until August 1910. He served on the submarines B3 and C38. It was while in the Submarine Service that he became interested in aeronautics. Returning to sea again in August 1910 on the Duncan, he became sick in October 1910 having contracted pulmonary tuberculosis. Given a years leave, he was then placed on the retired list in October 1911.

Porte was a fine naval officer and his association with the submarine service is common amongst many of the early naval aviators. After three or four months in Switzerland he returned to the United Kingdom and began a career in aviation. He had built several gliders while stationed at the Submarine Depot, Portsmouth, and also purchased a machine, a little monoplane of the Santos Dumont Demoiselle type.

Porte learned to fly at Reims, France, and gained French Aero Club Certificate No.548 on July 28, 1911, flying a Deperdussin monoplane. He had a successful racing season and he started an aviation syndicate with an Italian, Mr D. Lawrence Santoni. This syndicate was later transferred into a company, the British Deperdussin. Aeroplane Company Ltd. The company ran a flying school at Brooklands and later at Hendon and were agents for the French Deperdussin company. Porte states that during this time he was working with aeroplanes and seaplanes.

In the latter part of 1913 he joined the firm of White and Thompson of Bognor. He worked with them for only a few months as Assistant Manager. While with this firm he first saw the Curtiss flying boat at Brighton and met Glenn Curtiss through his friend Captain Bass who had bought one of the Curtiss boats. Bass convinced Porte to join a syndicate to build/market Curtiss flying boats in the United Kingdom. Bass gained the sole agency for Curtiss flying boats and engines in Europe, and in February 1914, transferred this to the White and Thompson Co. The latter set up a flying boat school and Porte was appointed flying instructor. It appears that Curtiss was impressed by Porte’s flying of the Curtiss boat.

Porte was ’’very struck” with the possibilities of the Curtiss F-Boat and flew it several times, including times when Curtiss was present. It was the first time Porte had seen a flying boat. It “was a boat with wings on it rather than an aeroplane with floats on it and was therefore it had much greater seaworthiness and much greater stability.”

Curtiss had brought a 1913 Model F flying boat with him to demonstrate in Europe. This boat differed from the “standard” F-Boat in that the ailerons were attached to the trailing edge of the upper wing rather than mid-wing as on most other F-Boats. The English F-Boat was detailed in Flight magazine of 11 April 1914. The flying boat was criticised as it was considered structurally weak and poorly constructed.

Norman Thompson also considered the Curtiss to be poorly constructed and set about overcoming these deficiencies in his design of the White and Thompson No.2 Flying Boat. Bass crashed his Curtiss boat and it was reconstructed with wings of RAF 6 section. Fitted with a 100 hp Anzani radial engine its performance was markedly superior as compared to that with the original Curtiss wings. In this guise it was known as the Bass-Curtiss Airboat.

Porte contends that he was one of the first persons to talk seriously about flying the Atlantic as far back as 1911. He thought that the flying boat was the answer to the task of flying the Atlantic. He eventually saw Mr Tuchy of the New York World in London and discussed the idea with him. This scheme nearly came about but fell through at the last moment. He saw one of the directors of the English Daily Mail and shortly thereafter they made their famous offer of a prize for the first flight across.

Porte then obtained an introduction to Rodman Wanamaker in February 1914. Wanamaker agreed to finance the scheme using a Curtiss machine. Wanamaker’s agents had already been in touch with Curtiss. Porte only stayed ten days and then returned to England.

Prior to his trip to America Porte had gone to Paris in December 1913 where he again met with Curtiss who was showing a boat there. Porte recalled that “Curtiss took a great liking to me and was deeply interested in my ideas for the development of his flying boat and we got on extremely well together.” Curtiss and Porte discussed the Atlantic flight and Porte agreed to go to America “as long as my travelling expenses and one hundred dollars a week were paid for my living expenses.” This amount was eventually paid by Wanamaker.

It was originally suggested that the machine for the Atlantic flight be a land machine with a 200 hp motor. When he realized that such a motor was not going to materialize, Porte states that he went back to Curtiss with the suggestion that “a large boat with 2 of his engines of 90 horse power each” would be the best machine for the proposed flight.5 Glenn Curtiss testified that Porte had suggested a floatplane with two cylindrical floats that would also serve as fuel tanks. Whatever the truth of the matter, the machine finally agreed on was a twin-engined flying boat.

In April 1914 Porte returned to America with the intention of “helping to design the machine and prepare the boat and make all necessary arrangements for flying” the Atlantic. “In fact in this particular machine the improvements were entirely my idea...this machine was built under my supervision and I also made a number of suggestions with regard to the alterations to the hull which were carried out and my suggestions were taken up by Mr. Curtiss.”

Porte had worked closely with Norman Thompson on the work of improving the Curtiss F-Boats. The experience was his introduction to his practical knowledge of flying boat construction, and he took this expertise with him to America where it enabled him to be of practical assistance in the work of designing the Americas hull. Casey gives credit for the design of the America boat to B. Douglas Thomas, an Englishman that Curtiss met on his European trip in 1913. Thomas designed the Curtiss Jenny and it would be logical that he would have had a great input into the design of the boat, especially the wing structure.

Wanamaker wanted a mixed American and British crew as he wanted the flight to celebrate 100 years of peace between the USA and Britain. Curtiss was so impressed with Porte that he had invited him to join the crew of the proposed trans-Atlantic boat as pilot. Lt John H Jack Towers, USN, was suggested by Curtiss as the American half of the crew. Towers was a pilot as well as an expert navigator. Towers had flown the Navy’s first hydroaeroplane, the Curtiss A-1, and had carried out experimental work with Curtiss on Naval aircraft. The USN had difficulty in accepting that a serving officer would be co-pilot to a British citizen, and the American crewmember was not resolved when Towers was ordered back to duty, sailing for Mexico in April 1914.

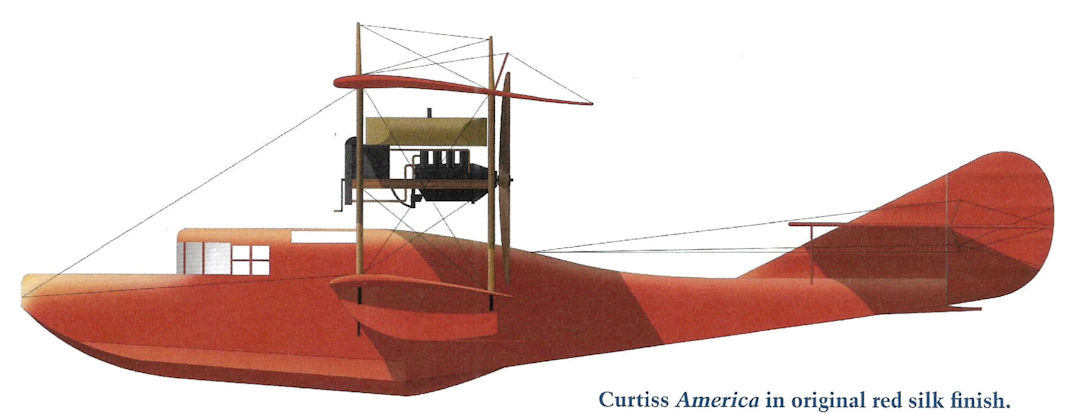

The Wanamaker flying boat was erected in on the shore of the lake as no building in the Curtiss factory was large enough to house it. The biplane flying boat was a handsome craft with a single step to the hull and of narrow beam. The hull was built on a framework of white cedar and ash following boat building practice with stringers and formers to give the hull its shape. The skin comprised longitudinal 1/2 inch strips of spruce secured with brass screws. The V-bottom of the hull had two layers of 1/4 inch planks laid at an angle to each other, the layers separated by a layer of cotton fabric set in marine glue. The whole was covered with red Japanese silk and varnished. The wings were in seven sections; a centre section; four main panels and two overhangs at the extremities of the upper wing. They were covered with red silk. In the event of a mid-ocean landing the wings could be jettisoned. The rudder was attached to the rear of the hull which terminated in a vertical knife edge. The lower section of the rudder was metal bound oak for steering in the water. The upper section was constructed of ash and covered with fabric. Power was provided by two 90 hp Curtiss OX V-8 water-cooled engines mounted between the wings turning eight-foot counter-rotating pusher propellers. There were two bays of interplane bracing outboard of the engines. The upper wing had long extensions that were braced from king posts on the upper wing set above the interplane struts.

Four watertight bulkheads plus four watertight tanks in the stern were to provide buoyancy in the event of a forced landing. Three tanks were mounted forward of the step and allowed for 500 gallons of fuel. Fuel was pumped from the main tanks to a gravity tank in the upper wing by a rotary gear pump. An auxiliary hand pump was fitted for emergency use. Unusual for the time “over the body of the boat is a permanent cabin top fitted with celluloid windows on top, in front and on both sides, forming an enclosed cabin and pilot house.” The pilots sat side by side on a bench seat with dual controls. The wheel controlled the rudder and each aileron was independently controlled by the foot pedals. The “horizontal rudders” (elevators) were controlled by lateral movement of the control column. This arrangement was incorporated due to the litigation being undertaken by the Wrights over patent infringement. A mattress was situated in front of the fuel tanks so that one crewmember could rest at a time. Directly in front of the pilots were the instruments including tachometers, aneroids, wind speed gauge, inclinometer, fuel and oil gauges, compass, etc.

The triangular fin was of low aspect ratio with a rounded rudder of pleasing shape. The tailplane was mounted high up on the fin.

On June 19, the name for the new flying boat was announced. It was America. In 1910 Walter Wellman, together with five crew, had tried to fly a hydrogen balloon across the Atlantic. Their effort came to nought when they were wrecked in a gale and miraculously; all were rescued by a British mail packet. The balloon had been named America.

The 16 year old daughter of Curtiss’ friend, Leo Masson had been selected to officially christen the boat. On the 22nd the ceremony took place. Unfortunately a British flag could not be located. After two failed attempts a sledgehammer was used to break the bottle of Great Western champagne and the boat was pushed into the water. It was too late to fly and it was to be the next day when the engines were run up and Curtiss and Porte took the aircraft up at 3.00PM for its first flight.

Who Designed the America?

In June 1923 the Royal Commission on Awards to Inventors considered the Curtiss Corporations; Mrs Porte’s and the Norman Thompson claims at the same time. As the Curtiss attorney had intimated that Porte had no input into the design of the America flying boat, Glenn Curtiss was called as a witness. Mrs Porte’s representative questioned Curtiss in depth as to the events that led up to the successful conclusion to the America boat as purchased by the British. Curtiss insisted that he was the designer but after evidence was produced in the form of correspondence between Porte and Capt Creagh-Osborne, RN, Curtiss agreed that Porte did have some input into the design of the America. He stated that “There is no question but that Colonel Porte’s experience was of value and these matters were determined by experiment there and then.”

Sometime in April 1914 Porte wrote to Creagh-Osborne, who was to be sent to the USA to keep the Admiralty up to date on the progress being made at Hammondsport. According to Glenn Curtiss’ testimony, he was only aware that Porte had requested Creagh-Osborne as he was an expert on compasses and Porte wanted “to get him over there to help arrange and test the compasses.” In his letter to Creagh-Osborne, Porte wrote that “he had not been able to arrange anything definitely yet as the date of the flight seems uncertain, but during the past week we have altered the whole scheme, chiefly through my persuasion and arguments so I think by the end of this week we may know something pretty definite all round... We have now designed a real sensible machine which I hope will be able to rise decently from rough water and carry about 22 hours fuel supply.”

In a further letter to Creagh-Osborne, Porte left a detailed account of the experiments undertaken to bring the America to a standard that would be capable of undertaking the transatlantic flight as follows:

Result of Trials to Date, July 9 th

“Directly the America was taken out for the first time it was seen that she had insufficient planning surface and would only get off the water with about 3,500 pounds total weight. Small submerged fins of about one square foot each were fitted each side of the step, and proved of no value at all. A radical change was then made and large fins of triangular (sic) cross section, were fitted each side of the hull in front, the bottom sloping slightly outward and upward. These extended 2’ on either side with the back edge at the step. It was at once seen that there were a considerable improvement. The total load raised was 4,400 lbs, but this was the limit.

The main step was then extended back some 40” and tried again. This proved useless as the machine persisted in violent porpoising. Extensions were then fitted to the back and sides of the fins, but made of flat boarding. These did not seem to have any effect, probably due to their not assisting at all in the floatability of the machine. Two flat pontoons were then fitted underneath the first strut outside the engine section. These pontoons were ten feet by three by eight inches/deep, the bottom being three inches above the bottom of the boat. These again proved of considerable assistance, the machine raising a total weight of 5,000 pounds off the water.

However, all these fittings were of too complex a nature to be serviceable so the whole lot was discarded and a false bottom 14 feet wide was built underneath the boat, this false bottom being made of flat planking slightly sloping upwards on each side of the boat. This again proved entirely useless, due no doubt to no increase in the floatability of the boat. This false bottom was again discarded and submerged fins substituted, these extending from just in front of the step at right angles to the boat slightly sloping upwards; these were six feet by a foot and a half. On trying these the machine immediately came to the surface bringing the fins out of the water with the result that he machine immediately dropped back again to her original position without having attained a speed greater than twelve or fifteen miles an hour.

A second fin was mounted underneath this, shorter and a foot lower, being beneath the bottom of the boat, the only result being the machine rearing right up on the water on the lower fin and repeating the operation of porpoising and falling back again. These fins, although they might eventually be made to work on a smooth lake or river, it is doubtful if they would ever be of any value in a seaway. After this the fins were cut off and pontoons reverted to, these are still on trial.”

The hull was originally wall sided and the seaplane had difficulty in getting off with this hull. Experiments were carried out to overcome this problem. Curtiss documents give the following diary of events:

June 23 20 minute taxi flight at 3.00PM. 4.06PM Porte made second flight.

June 24 Hydroplane boards added to hull did not work as aircraft could not lift required load. Men worked all night to change boards. Porte made night flight at 8.00PM, carrying 500 lbs more than that of the 23rd.

June 25 Hull changes worked well. The boat raced a Curtiss M-boat and Curtiss in his hydroplane boat Skimmer. The hydroplane boards were changed to a larger size (24 inch) by the men working all night in order to allow the aircraft to carry a 1,400 lb load.

June 26 No flight.

June 27 Seven men carried aloft.

June 28 Storm threatened aircraft.

June 29 One flight with eight men and a second with ten men (reporters). Removed tail hydroplane.

June 30 Three flights made. Confirms can carry over 4,000 lbs but needs safety factor.

July 1 Two 1 1/2 minute flights. Side fins lengthened and special Olmsted propellers were fitted. In this form the aircraft met its specifications. Curtiss was not satisfied as Olmsted propellers were prone to splitting.

July 2 Olmsted propeller tests. Langley pontoons added for tests. New bottom to be placed on boat - two feet deep loaded.

July 3 Test of new hydroboards (so called “barn door bottom”). No flight.

July 5 Flight tests on one engine. First one then other. 3.00PM flight with seven passengers (4,500 lb load).

July 7 Porte flies America.

July 8 Langley pontoons placed back on boat.

July 15 Rebuilding hull after water trails.

July 16 Sea sled hull repaired and tested on water.

July 18 Test failed as nose rose and tail went down into water.

Possibility of third engine considered. Also the engines did not develop their designed power, but only about 85 hp. Curtiss installed a third motor driving a tractor propeller on the wing centre section.

July 20 Third motor added. Changes in hull. Auto searchlight mounted with lamp in cockpit and small hand lamp for use by mechanic.

July 23 Flight with third motor. Must carry 2,289 lbs for flight across Atlantic, flew with total load of 2,654 lbs. Fuel consumption tests. Tip flew off Olmsted prop damaging wing rib and fabric. Repairs delay teat until evening. Bottom to be rebuilt before shipping to Newfoundland.

July 25 Trans-Atlantic flight delayed till October. Time required to rebuild bottom of hull and more test flights need to be made. On test it was discovered that the third engines fuel requirements offset any advantage. 28 changes were made to hull during experiments and came back to second plan as the best method.

Port was to recall that the whole bottom of the hull was then rebuilt with fins extending from the stern (Porte must mean the bow. Authors note.) as far as the step on each side. The overall width being 8 feet and the hull proper only 4 feet. In cross section the bottom showed a slight (straight sided) V form from keel to fin edges and extending as far aft as the step. The tail being flat bottomed. This form of hull was embodied in all the Small Americas.

It is to be noted that Curtiss carried out trials and modifications in the field in a crash program with a full sized machine rather than theoretical knowledge from model hull experiments. There was little knowledge available at the time relating to the problems that they were trying to solve. Porte would use the same methods when he returned to the UK and was placed in charge of developing an effective flying boat. As noted above, the trials on Lake Keuka confirmed that the America, the largest flying boat built up to this time, could not carry the required load for the trans-Atlantic flight. With full load it would not lift from the water. The bow would submerge when power was applied and a program began to add buoyancy and increase the planning area of the hull. Hydrofoils were tried at least two different locations before being discarded. Various other methods were tried including fitting a broad seasled type of device to broaden the hull. Later this was matched by fins/sponsons built into the hull. Also the engines did not develop their designed power, but only about 85 hp.

According to F.N. Hillier, who was with Porte “during those days of fruitless preparations at Hammondsport, New York, during the summer of 1914,” up to the end of July, “when we all packed up to come home in view of the imminent outbreak of war, it had been impossible to coax the aircraft off Lake Keuka with any better load than two bodies and a few gallons of petrol.”

On the declaration of war, Porte immediately returned to England. “In fact I actually sailed from America on the 4th August one and half hours after war was declared. I was so rushed that I left a lot of my clothes and papers at Hammondsport. I had a long interview with Mr. Curtiss in New York just before I left to come back.” He asked if the two boats would be available if the British Admiralty wanted them and Curtiss agreed that they would be available.

As soon as he arrived he volunteered his services to the Navy and, although still suffering from tuberculosis, he was accepted and appointed a Squadron Commander, and took up duties at Hendon. He saw Commander Murray Sueter, the head of the Air Department of the Admiralty and Porte informed him that the two America flying boats were available for sale in the USA. Porte did not know the price of the boats but knew that they would “cost a great deal of money.” Sueter recognized the value of such machines for the new type of warfare that was likely to be waged against German submarines around the British coast, and asked Porte to find out the cost of obtaining the two boats and the cabled prices were £6,000 and £4,500.

In a letter to Sueter on 14 August Porte wrote that the “hull is built very strongly and should be capable of standing a good sea. She will arise from the water with a great facility except when heavily loaded when it is necessary to have a smooth sea. The machine is very steady in the air and specially built to facilitate navigation, the compass behaving well. This machine should be finished this week, and I have no doubt it could be shipped in about three weeks.”

It is assumed that Porte was referring to the changes that had to be made to the original America rather than a completely new boat. He continued...

“A duplicate is about three parts built and could be finished in about three weeks. If it is desired, these machines could be purchased privately and shipped via Halifax, but there seems some doubt whether this course will be necessary."

Sueter considered that “these machines would be used for operations in the North Sea as they can lift a large weight, either in the form of fuel for scouting purposes, or in the form of explosives for offensive purposes.” He considered that the price asked was fair and that while no money was available for the purchase, it was a small amount, and he recommended that the two machines be purchased for £9,500. Delivery would be in New York, packed ready for shipment as Curtiss “refuse to consider the question of shipping the machines.”

The initial price asked was considered too high and Porte was asked to negotiate a reduction. Curtiss dropped the price to $25,000 for the first machine and $22,500 for the second one, which Porte considered a “considerable reduction.” This was accepted provided that Curtiss deliver both complete and properly packed for shipment. It was stated that the names “AMERICA” or “TRANSATLANTIC” were not to be used. The reason for this is not stated, but may have been an attempt to disguise the shipment from German agents. If so then they were not successful. The Admiralty’s General Agent in New York wrote that while the greatest secrecy should be observed, the shipment had been well advertised in the UK and the British Consul General “has been mixing in this quite a great deal.” The small town of Hammondsport where the machine was shipped from meant that it was impossible to keep its movements a secret; also a special train had to be employed. US newspapers commented on the acquisition and how it may have international implications due to the war.

The Admiralty purchased the two boats on Contract No.C.P.52840/14. The first was shipped via the Mauretania as deck cargo under a dummy bill of lading. The Germans protested but the US Secretary of State declared that aeroplanes were not contraband of war. Designated H-1 in British service they received serials 950 and 951.22 The first arrived at Felixstowe in October 1914, the second about six weeks later via the infamous SS Lustinia.

They were taken directly to RNAS Station at Felixstowe and erected. Porte went to Felixstowe to see the boats when they arrived but was not involved with them at this time as he was in charge of Hendon aerodrome. “I was to test the first one and Commander Suter (sic) himself came down to take a flight in it and examine it himself. I took him for a short flight, that was at the beginning of November 1914 and he returned to London.” On arriving in London Sueter reported to the First Sea Lord, Winston Churchill, praising the boats saying that he considered them excellent. Apparently Churchill was impressed as he wrote on the report: “Order 12 of these at once.” According to testimony given to the Royal Commission of Awards to Inventors post-war, none of the Small America boats ever made a patrol, the 56 supplied by Curtiss being used only for training in sheltered waters. Other sources state that patrols were made but being experimental they may not have been officially considered as an active service patrol?

Originally these boats had lifting tails which made them easy to get off the water with a full load, but they were not very stable in the air. To correct the instability the weights were rearranged and the tailplane incidence decreased. This made them stable fore and aft. In rearranging the weights the engines were changed from pusher to tractor configuration. This improved their flying qualities but they were nothing like as good in getting off the water. Anzani engines were substituted for the Curtiss engines as the latter had proved very unreliable. Although the boats were still satisfactory in getting off in smooth water, in a sea way they were very wet. Water was frequently thrown over the engines in sufficient quantities to cause them to misfire and prevent getting off.

Porte recommended that the boats be built in the United Kingdom rather than being purchased abroad. Eventually an order for eight was given to the Aircraft Manufacturing Company (AMC) at Hendon (1228-1235), and four were ordered from Curtiss (1236-1239). As explained hereunder, there were some dubious dealings undertaken with respect to this order with the AMC.

Four Curtiss Transatlantic “America” type Seaplanes were ordered at a cost of $22,500 each together with 20 Curtiss OX motors (ten LH and ten RH) at $2,800 each for a total contract price of $146,000. The boats were to have “the Deperdussin type of control with ball bearing pulleys” fitted in each machine. Lyman J. Seely, the Curtiss Company representative in the UK, sent a Telegram to the Curtiss Company at Hammondsport noting that the official acceptance of the tender for “four H. Oats twenty motors” would be in the nights mail. In this telegram Seeley states that the specifications “demand boats with long tail hulls like America second (Author’s italics) with wings attached at center (sic) by sockets and pins for quick demounting hulls tighter bottoms braced and strengthened between wings beams and bottom.”

The Admiralty also asked that the question of providing folding wings be considered but this came to nothing. The four Curtiss built boats arrived in the spring of 1915 and were sent to Felixstowe. They were received long before those manufactured in England were completed.

These latter boats should have been produced early in 1915 but were delayed for a variety of reasons. They were constructed under Porte’s supervision at Hendon, the local manufacturers were allowed to measure and take details of the construction of the Curtiss boats. The hulls were built by Saunders at Cowes using their patented Consuta form of construction. The straight lines of the Curtiss boat were replaced by curves, the planking being sewn with stranded copper wire. They were not a success mainly due to their form of hull construction, the copper stitching breaking through the planking. The work done with these boats tie the development of the Curtiss machines into the following Felixstowe F-boats and their story is detailed in Chapter 2.

Marketing of the America Boats

That it had not started for its momentous voyage from St. John’s, Newfoundland, to the Azores Islands under the guidance of Lieut. John Cyril Porte, R.N., at the time war was declared was due to so small a chance as the accidental stripping of the copper sheathing from the special propellers he was to have used.

So ran Curtiss advertising following the outbreak of World War I as Curtiss tried to market the America flying boat. From the above there can be seen a distortion of the truth in that the boat would not have embarked on the trans-Atlantic flight until after more testing and redesign.

In his advertisements Curtiss noted that the machine could be used “either as a sporting vehicle or for naval use... Her weight-carrying capacity and her steadiness make the mounting of a gun of considerable size, the use of light armor (sic) plate, and her equipment with long range wireless apparatus entirely feasible.” As a civilian machine it could carry up to a dozen passengers or for long range cruising it would be fitted with folding berths for two or three men.

As far as is known the only America boat ordered by other than the British was one ordered by the Danish Ministry for the Navy in the autumn of 1916. Lt (jg) W. Capehart of the USN Bureau of Construction and Repair, reported on the boat built for the Danish Government in November 1916.

Capehart wrote that the H-4 type P.B. (Patrol Boat) flying boat had a windmill pump that forced fuel from the 200-gallon tank in the hull to the 12-gallon gravity tank that fed both motors. The auxiliary oil tank contained 8 gallons for each motor. Zentih Duplex carburettors were installed. Each motor had an independent hand throttle and switch.

He did not like the “big overhang of the upper wing for structural reasons”. He considered that the lack of leverage for the tail controls was “evidently made up for by size.” The vertical fin and horizontal stabilizer looked like “the biggest I have ever seen.” He also considered that the boat had an usual shape and referred to the photographs in his report.29 It is evident that he was not impressed with the machine.

At 2PM on 10 November, Carlstrom, the Curtiss test pilot, made a short solo flight. The machine appeared to get off satisfactorily but it was immediately evident that the machine was tail heavy or else the setting of the tailplane was out. In order to get back onto the water without tail sliding or stalling, Carlstrom had to jolt the nose down by sudden and frequent bursts of power. He was finally able to make a 12 minute flight that afternoon after several attempts to get the boat into flying shape. He had 700 lbs of weight in the bow to overcome the tail heaviness.

The next day it was discovered that the hull had a great deal of water at the tail. This was the cause of the extreme tail heaviness the day before. With the boat dry and 335 gallons of fuel in the main tank, the boat was balanced with Carlstrom alone and 150 lbs ballast in the bow. When he came back from his first flight of the 11th, Capehart and Lt Scofield joined him for a timed flight. Scofield sat back in the body of the hull near the main fuel tank. The average speed over the one mile course was 66.6 mph. On trying to climb, 300 feet was reached in the first minute, then the port engine gave trouble and the boat came down.

At slow speed in rough water, the boat would plow badly. It planes readily, gets off readily, and lands readily. I could see no particular difference between its action and that of the smaller flying boats which I have flown at Pensacola. I do not consider it would be a satisfactory machine for our use.

Capehart noted how hard Carlstrom had to work the controls. He considered it would tire a man in about 15 minutes. “It was impossible for him to turn the rudder far enough for it to be of any great use.” Carlstrom would run over the course, land, turn around on the water and then take off again and run back over the course in the opposite direction. Capehart considered it too dangerous to attempt a slow speed run under these conditions. ”It seems likely that “Servo” Motors would be necessary for the aileron controls of a big boat as well as the rudder controls, or balanced controls.”

The following notes were made by Capehart:

- Do not like such big overhang of upper wing for structural reasons;

- Tail control wires lead out of Boat body on way aft just inline with propellers;

- Clearance between the Propeller blades and control wires about 10 inches,

- Motors were started by hand cranks every time, but with difficulty;

- The Boat body is relatively short;

- Lack of leverage of tail controls evidently made up for by size;

- Vertical tail fin and horizontal stabilizer looked like biggest that I have ever seen;

- Boat has unusual shape;

- Do not like structural details of tail controls, horizontal stabilizer, etc.; should hate to have to pull out of steep dive suddenly;

- Horns for control leads to rudder are very short, giving poor leverage, - 6".

1st Lt Asger E.V. Grandjean, later commander in chief of Danish Naval Aviation, was present when the aircraft was test flown on Lake Keuka at the beginning of 1917. The original 100-hp Curtiss OXX-2 engines could not meet the performance specifications and were replaced with engines of higher power. However, these did not improve the performance of the aircraft sufficiently and the Danish authorities refused acceptance and the contract was annulled. The funds were used to purchase a number of 100 and 200-hp engines that were installed in Danish made Madge (Gull) flying boats.

There is mention of a boat for Norway in USN documents. Photographs in the file show an America type boat with conventional tail surfaces, a balanced rudder and pusher engines. A Memorandum from J.W. Scott of the Curtiss Aeroplane Co, to Hunsaker, noted that a H-4 being constructed for Denmark would be ready about 8 November 1916.33 The Memorandum continues...

“A somewhat similar aeroplane built for Norway was inspected by representatives of the Bureau(s) of Construction and Repair and Steam Engineering at Hammondsport, N.Y., recently, and was found badly out of balance and recommended as unsuitable for purchase.”

It is possible that the Danish machine was confused and referred to as one for Norway. The tests attended by Capehart may have been for the re-engined Danish boat. As with so many early aircraft, it is hard to be precise as to which aircraft is being referred to in surviving documents.

In March 1916 Mark L. Bristol, the officer in charge of US Naval Aviation, noted that the large type of flying boat produced by Curtiss “commonly known as the American type, has received no real demonstration in this country in rough water.” Curtiss was going to have one of the machines shipped to Hampton Roads where “they have a flying station” and then it would be possible to demonstrate the type in the open sea. “A number of these machines have been sent abroad, but exact knowledge as to their behaviour in the open sea is not available.” No documents relating to such a test have been found. The USN continued to develop the pontoon aircraft for sea use.

Curtiss H-4 Small America in British Service

The Admiralty used its seaplanes for anti-submarine patrols and mine hunting in support of the ship patrol as well as its responsibility for home defence. The Sopwith and Short floatplanes were next to useless for this work but were all that was available. It was felt that the Curtiss boats would give the Admiralty an effective weapon.

The first two boats supplied to the Admiralty were the original America boats. This is confirmed in US newspaper articles of the time. The first boat, 950, was delivered to Felixstowe on 13 October 1914, with the other, 951, following on 25 November. John Towers, USN, was in the UK to report on British developments for the US Navy at the time and while “poking about Hendon...watched Cyril Porte test the two modified Curtiss America flying boats just brought over from Hammondsport.” Until the US entered the war on the Allies side, Towers received very little cooperation from the British. F.N. Hillier recorded that when he next saw Porte “at Felixstowe in the early summer of 1915, the America, in which Porte gave me a short flight, had two sister ships which were doing three-hour patrols over the North Sea.”

As noted above the next Curtiss boats purchased by the British (serials 1236-1239), were ordered from the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Co, Hammondsport, and were similar to the first two boats. Although they are referred to under the designation of H-4, Casey states that one of these was a sister ship to the America (an H-1) and the other three were H-2 boats. The information supplied by Curtiss in its claim for compensation post-war indicates that these four boats carried the factory designation H-2. The British designation H-4 will be used here. The H-4 had a hull two feet longer than 950, the tail was more square and, unlike the AMC/Saunders hulls, they had a plain V bottom.

The first Curtiss machine (serial 1236) was delivered to Felixstowe on 17 January and the last in March 1915. The first AMC boat was not delivered until 20 June 1915. In February 1916, C.L. Vaughan-Lee, the RNAS Director of Air Services wrote that there had been some cases of Aeroplanes and Seaplanes on order whose delivery has been so long delayed that they are hopelessly out of date and already useless before delivery.

Vaughan-Lee wanted such contracts cancelled on “the best possible terms”. The AMC contract was one considered by Vaughan-Lee for cancellation as five of the eight Curtiss Boats ordered “have been overdue for more than one year and action is being taken to consider the cancelling of the outstanding portion of the contract.” Despite this the AMC contract was completed the last boat being delivered to Felixstowe in January 1917. Porte recorded that the “Boats were built under my supervision at Hendon. The hulls were built by Sanders (sic) at Cowes.”

On 12 March 1915, Felixstowe had a White & Thompson, two H-1 and four Curtiss built H-4 flying boats on strength as well as a number of Short floatplanes. The Curtiss engines were replaced by 150-hp Sunbeams or 125-hp Anzani radials as the Curtiss engines did not produce their required power and were considered unreliable. It was reported that the original boats could not get off the water with their Curtiss engines even when all excess weight was removed from the boats. It was found that the hull was weak at the step and would break at this point in a sea wave. Due to the very short fore-body and lack of buoyancy forward the boat was entirely unseaworthy. The hull was so weak that the tailplane would sag under its own weight and alter the trim of the boat once the machine got under way.

Despite its shortcomings the First Lord of the Admiralty pointed out that “the Curtiss machines, and in fact all aeroplanes and seaplanes delivered from America - must be considered as an addition to our forces. The machines must be taken as they are, and must be made the most of in spite of the defects.” As noted above, eight America type flying boats had been ordered from the Aircraft Manufacturing Co (Serials 1228 to 1235) under Contract C.P.65070/14. The first three British built H-4 boats were delivered from June 1915; however the latter five not delivered until 1916.

Curtiss received an additional order for 50 “H-4 Transatlantic Boats” in March 1915 under Contract C.P.01533/15 (Serials 3545-3594). As related below, these would be the aircraft from the order for 150 machines that Porte reduced to 50. Records show that 31 boats on the order were delivered as complete machines, while the rest were delivered without engines for a total cost of $1,125,000. The same schedule shows that nine spare H-4 hulls, 18 sets of spare main planes, rudders and wing floats, plus nine tail units, were ordered under Contract No.C.P. 105569/16/X, and were all delivered at an additional total cost of $112,590.

T.D. Hallam, a Canadian, had learned to fly on Curtiss flying boats at Hammondsport before the declaration of war. He eventually found his way into the RNAS and ended up at Felixstowe. He recounted his experiences in his classic book, The Spider Web - The Romance of a Flying-Boat Flight in the First World War. He recalled that the early Curtiss H-4 flying boats were comic machines, weighing well under two tons; with two comic engines giving, when they functioned, 180 horse-power; and comic control, being nose heavy with engines on and tail heavy in a glide. And the stout lads who tried impossible feats in them usually had to be towed back by annoyed destroyers... the Navy people could not understand anything that could not be dropped with safety from a hundred feet, or seaworthy enough to ride out a gale.

This assessment is harsh. The Curtiss engines were changed for Anzani engines that, although rated lower, were more reliable and therefore considered more satisfactory. The machines proved to be excellent pilot trainers, it being possible to make every kind of bad alighting without damage to the hull when operating in sheltered waters (authors italics). Propeller shafts sometimes broke and it was not unusual to spend an hour changing plugs before a machine could get away. It was often only just possible to keep in the air with cylinders missing.

These boats have been known to climb as high as high as 6000 ft. but usually they were only just able to get off the water, and struggle up to 500 or 1000 ft. The least sea caused spray to be thrown over the pilots. It was a common sight to see clouds of steam generated from the sea water going over the engines. A certain number of patrols were carried by these machines early in the war from Felixstowe. The armament was 2 16 lb hand/bombs and a rifle. The operational success was not great, but these boats paved the way for the important developments which followed."

Most of the pilots who made the Large Americas a success had spent hours training on these boats.

The shortcomings of these early boats were such that it would take a lot of work to improve the design to where it could operate under North Sea conditions, but progress was already underway under the hand of Porte. He had started to experiment with modifications to the hull in an effort to improve performance.

In early 1915 it was decided to establish a Naval Air station at Gibraltar and two “large seaplanes of the Atlantic type and 4 aeroplanes have left England. These machines will be supplemented when the station is erected.” These machines would have been H-4 boats 1236 and 1237 that were shipped to Gibraltar around May 1915. They performed patrols in the Mediterranean, America 1237 lasting until February 1916.

The first H-4 was written ofF at Felixstowe in January 1916. Declared obsolete in August 1918, three managed to survive the war. Serial 3580, which had been modified to become the Porte I, was the last Small America boat afloat. 3545 was scrapped in November 1918. The hull of 3548 had been sent to the Agricultural Hall, Islington, London, for preservation, but along with other priceless exhibits was later destroyed.

When the US entered the war on the Allies side, many personnel were trained in the UK and France. Some US Naval aviators were trained at Felixstowe and flew the Small America boats. 3587 was delivered to Felixstowe for erection on 16 March 1917. Ens Phillips Ward Page was flying this machine solo on 17 December that year. He had just performed a perfect alighting and taken off again. When he was at about 40 feet, for no apparent reason, he sideslipped to the left and nosedived into the water, the left wing apparently striking first. An F-boat had just alighted and taxied to the stricken machine that was floating with half the wings submerged and the tail vertical. Three motor boats from the Station and several life boats from trawlers anchored nearby also arrived. They were unable to right the aircraft or get to the pilot. On towing the wreck to the beach it was discovered that the upper part of the bow had been torn away and the pilot had been washed out. No trace of his body had been discovered by the following day. The flying boat was a complete wreck and was deleted on 12 January.

White & Thompson Ltd acquired the exclusive rights for the sale of Curtiss aeroplanes, flying boats and engines for Great Britain in 1914. Porte was one of the company’s pilots and flew the English Curtiss Model F flying boat that Glenn Curtiss brought to the UK in 1913. As such all negotiations for the supply of Curtiss boats should have gone through the company and this was the basis of the dispute that the company, renamed the Norman Thompson Flight Co, had with the Curtiss Company.

Norman Thompson built their own twin engined flying boat as the N.T.4 and N.T.4a, and to further complicate matters, they were also known as America/Small America flying boats. They differed considerably in design from the Curtiss America boats, being larger and their hull design owed little to the Curtiss boats. They are described in detail in Chapter 5.

The Felixstowe Line

At the end of January 1915 Porte was given charge of the Felixstowe Naval Air Station and in May he left Hendon altogether. He had also been appointed in charge of the Chingford and Chelmsford Naval Air Stations, but had to give them up at the same time as “Felixstowe became so important that it required my full attention.” At the time Felixstowe comprised 30 men and three small sheds engaged in local patrols with a few antiquated seaplanes. By the end of the war it had grown to some 1,000 men and a large number of buildings to be the largest Naval Air Station in England. Long range patrols were carried out with greatly improved flying boats. The station became an experimental as well as a war station under Porte’s command.

According to Porte, a Capt Elder went to the US in March or April 1915 to arrange a very large order with the Curtiss Company. “The order was loosely placed and was badly placed, in fact, one could not make head for tail of it and it was over the difficulties of this contract and the frightful mess then made” that Porte went to the US to sort the contract out. The Admiralty had placed an order for 150 Curtiss boats. “I informed the authorities verbally that it was ridiculous - we could not do with 150 and there was nowhere to put them and so eventually in July or August 1915, I proposed I should go over to America to the Curtiss Company, stop the order at 50 and place an order for a further 50 to be of a new design of a larger type which I was designing myself. The 50 machines of the original type were delivered and I went over and designed the improved boats and ordered 50 of these machines.” Porte went to America in August and returned in September 1915.

Porte flew the early Curtiss boats and was aware of their shortcomings which included a lack of seaworthiness, poor hydroplaning characteristics and poor stability on the water. It appears that the H-4 boats were armed with bombs but definite confirmation and details are lacking. He obtained permission to experiment to produce a flying boat with the operational characteristics required by the RNAS. These experiments are fully covered in Chapter 2.

Porte also designed and built a large three engined flying boat at Felixstowe. Named the Porte Baby its history is detailed in Chapter 6.

By practical experimentation Porte was developing his knowledge of what was required for a successful flying boat. It was alleged by the Crown when Porte’s contribution to the development of the flying boat was examined at the Royal Commission of Awards to Inventors after the war, that the development was a natural progression (author’s italics) and Mrs Porte, Porte having died in the interim, did not warrant an award.

When the larger H-8/H-12 were received all the earlier Curtiss boats were referred to as Small Americas, the H-12 boats, F.2A , F.3 and F.5 boats becoming Large Americas.

The Curtiss Flying Cruiser

The English journal Flight published a photograph of a “Curtiss aero-yacht de luxe, built for the America Trans-Oceanic Co. It is luxuriantly fitted up and carries five passengers.” This machine was apparently based on the late H-7. A single outrigger joined the rear centre section interplane strut to the leading edge of the tail plane rather than the two of the H-7. The machine was designed for the sportsman and the hull had accommodation for five. The two pilots sat in the large front cockpit that allowed for the accommodation of two passengers behind the pilots. Further aft was the cockpit for a mechanic.

Designed for sporting rather than for military use, the design and equipment of the Curtiss “cruiser”, afford an indication of the trend that development undoubtedly will take once the war is over. It is a twin-motor flying boat of the pusher type with a speed range of 65-48 miles per hour and weighs over 2 tons fully loaded. The equipment includes a Sperry gyroscope, searchlight, marine running lights, lights at the top of each strut, and electric starters for the motors. Current for all these purposes is developed by two small fan-driven generators located on the inner end of the outrigger which supports the tail unit.

Flat steel tube was used for the leading edge of the wings, the upper planes being in five sections. Spars were of “I” section spruce with ribs of pine, birch and spruce, except that the compression ribs are solid pine. Ailerons are on the upper wings only. Antiskid fins were affixed on the upper wing and braced the wing overhang. The lower wings were comprised of four sections. The two sections next to the fuselage were three feet long and were built rigid and covered with rubber matting in order that the mechanic could walk on them to service the engines. The outer wing sections were 19 feet in length.

The horizontal tailplane was carried on outriggers from the engine beds and struts arising from the stern of the hull. A large fin was mounted and an unbalanced rudder was mounted.

Two Curtiss 100-hp V-type motors were mounted between the wings. They drove opposite handed eight feet eight inch propellers and were equipped with electric self starters, though cranks were fitted for a hand start if required. The hull had an overall length of 34 ft 3 inches and a maximum beam of four feet at the leading edge of the wings. The hull was an ash frame and keel with mahogany and cedar sides covered with cloth.

Instruments included a compass attached to and synchronised with a drift indicator, and air speed indicator, fuel gauge, oil gauge, banking indicator, angle of incidence indicator, inclinometer. The throttle controls were placed amidships just between the two pilots.

Glenn Curtiss and Rodman Wanamaker formed the America Trans Oceanic Company in 1914 to promote the business that the success of the America flying boat was to bring to the aviation business. The outbreak of war ended the dream of a trans-Atlantic flight for the immediate future, however Wanamaker continued to negotiate with Curtiss for a trans-Atlantic aircraft and contracts exist of these proposals. In an interview with the New York World Curtiss noted that when the planed flight was abandoned he had purchased the America back from Wanamaker “on the understanding that he would build Mr. Wanamaker another machine with which to make the attempt as soon as circumstances would permit.” What operations were carried out by the Trans Oceanic Cruiser are not known.

J.L. Callan reported on the condition of the Trans-Oceanic Cos Cruiser directly to Glenn Curtiss as follows:

After having examined the Trans-Oceanic Co. Cruiser at Port Washington and talked to those who have it in charge I recommend that it shall not be flown until the hull now on the machine be replaced.

When this machine was first tried out at Hammondsport the motors were turning up 1650 R.P.M. and the boat was very light having been drying out in a barn at Hammondsport for over a year.

Unfortunately Callan did not date his report. It is possible that this report is post-war with the intention to bring the machine back into passenger service. Callan wrote that now the Sperry equipment has been installed on the machine and the hull becomes heavier through water soaking, the machine does not handle well in flight and no reserve is to be had from the motors. While at first it was possible to carry a dozen passengers it is now hardly possible to get off the water with five. (Authors italics).

This reference to a dozen passengers does not fit the description of the Cruiser in the 3 March 1917, article on the “Curtiss Flying Cruiser” in Aerial Age that stated that the Cruiser was with the America Trans-Oceanic Co at Port Washington, L.I.

The Company conducted training with a Curtiss F-Boat and offered the Navy a number of F-Boats after the US entered the war. The author has not been able to find any reference to the Cruiser being offered to the US Navy.

Post-war Trans Oceanic operated a Curtiss H-16 (the Big Fish), HS-2L, a Curtiss Seagull with a 150-hp Curtiss engine, and a Curtiss MF flying boat with a 90-hp Curtiss engine. The Company had contracts with the US Post Office and ran daily mails from their New York base to Chicago and Atlanta.

Curtiss Cruiser Specifications

Source Note 1 Note 2

Length overall 29 ft 0 in

Length Hull 34 ft 3 in 34 ft 3 in

Span upper 75 ft 10 in 75 ft Win

Span Lower 48 ft 0in 48 ft 0 in

Chord 7ft 0in

Aerofoil Modified RAF 6 Modified RAF 6

Gap 7 ft 6 in 7ft 6 in

Dihedral 1° -

Incidence 4° -

Span tailplane 16ft 0in 16 ft 0 in

Chord tailplane 6 ft 3 in -

Area, Sq. Ft.

Wings upper 457.63 -

Wings lower 301.83 -

Ailerons 46.85 (each) 46.8 (each)

Non-skid fins 12.4 (each) -

Horizontal tailplane 63.9 63.9

Elevators 24.9 (each) 49.8

Fin 34.9 34.9

Rudder 31.2 31.2

Hull Weight (with seats, accessories, etc.) 885 lbs 885 lbs

Empty Wt - 2,240.1 lbs

Engine Wt. (Curtiss OXX-2) - 1,316.5 lbs

Fuel & oil Wt. - 620 lbs

Net Weight 3,556 3,556 lbs

Useful load - 1,100 lbs

Gross Weight 4,656 4,656 lbs

Fuel 90 gal -

Climb in 10 min 2,000 ft 760 lbs

Source Notes:

(1). “The Curtiss Flying Cruiser,” Aerial Age, 5 March 1917, P.718.

(2). Typed specification table. RAFM J.M. Bruce Collection, Box 22 Felixstowe File.

The H-8 Pusher

This is another Curtiss flying boat that has a confused history. The flying boat referred to as the H-8 by Bowers in his history of Curtiss aircraft was a small biplane flying boat of pusher configuration. The change back to a pusher made it necessary to change from the twin booms of the H-7 to a single tail boom on the H-8 to avoid the propellers. This boom connected the engine section of the centre bay of the wings to the horizontal stabiliser at the intersection of the stabilizer and the fin. The hull appears to be similar (the same?) as that of the H-7. Only a single example of this aircraft was constructed in December 1915, at the Churchill Street plant. No reason has been found for the reuse of the H-8 designation if indeed this was the correct designation.

Casey states that the pusher configuration was not desired by the British and the machine was changed to a tractor before being shipped to the UK, however the size of the pusher aircraft appears to be much smaller than the H-8 as supplied to the British. Without data it is impossible to tell and no data are available.

The H-14

The H-14 was larger than the original America boat but smaller than the H-12. In November 1916, the Curtiss Aeroplane Co had written to the USN Bureau of Construction & Repair forwarding blue prints and specifications of the H-14. The machine was claimed to have an endurance of five hours “at rated horsepower” with a guaranteed high speed of 65 mph and a low speed of 48 mph. Climb to 2,000 feet was to be 10 minutes. “We feel confident that it can be relied upon for the above performance under all ordinary conditions and that it will do considerably better under usual normal conditions.” The quoted cost was $22,500 FOB Buffalo. Capehart forwarded the letter and documents to the Bureau of Construction & Repair and added the comments that it was understood “that this type boat is the type that the Company is bidding on in answer to the Army proposal for 144 water machines.” He repeated the statement that it was the H-7 “boat body with H-4 wings and control surfaces. In addition there is a stay rod as shown running back to the horizontal stabilizer thus making the tail controls stronger than those in the H-4 type.”

The Navy considered the offer and noted that this “boat is similar to one recently constructed for Mr. Wanamaker and the weights, performance, etc., are taken from the actual construction.” While the Company representatives stated that the Wanamaker boat had a high speed of 68 mph and climb to 2,400 feet (in ten minutes), they were not prepared to guarantee this. Notwithstanding these concerns, the Navy considered that two H-14 boats be purchased “by proprietary requisition for experimental purposes.” The hulls of the boats were to be stronger than that of the boat sold to the Trans Oceanic Co. A requisition for two H-14 boats, one equipped with Sperry Servo motor control was being prepared on December 6, the total revised price delivered to Pensacola being $35,664.

As noted above the H-14 was recorded by Lt (jg) W. Capehart, the USN officer at Curtiss, Buffalo, as having an H-7 hull with H-4 wings and control surfaces. By saying the machine had H-4 wings, etc., it is assumed that Capehart meant that the plan form was the same as the earlier boats. The H-14 had a very short overhang of the upper wing compared with the America. The wingspan of the H-series of boats varied according to the size and load of the designed machine but the same basic shape and layout was followed by Curtiss and Porte. The H-14 was powered by twin pusher Curtiss OXX-2 engines. Sixteen machines were ordered by the US Army before the prototype had flown (Army serials 396 - 411).