Описание

Страна: Великобритания

Год: 1916

Single-seat anti-submarine patrol seaplane

Варианты

- Sopwith - Schneider/Baby - 1914 - Великобритания

- Fairey - Hamble Baby - 1916 - Великобритания

- H.Taylor Fairey Aircraft since 1915 (Putnam)

- K.Wixey Parnall Aircraft Since 1914 (Putnam)

- H.King Sopwith Aircraft 1912-1920 (Putnam)

- F.Mason The British Fighter since 1912 (Putnam)

- W.Green, G.Swanborough The Complete Book of Fighters

- J.Bruce British Aeroplanes 1914-1918 (Putnam)

- O.Thetford British Naval Aircraft since 1912 (Putnam)

- H.King Armament of British Aircraft (Putnam)

-

H.King - Armament of British Aircraft /Putnam/

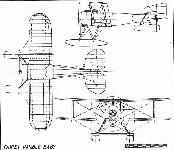

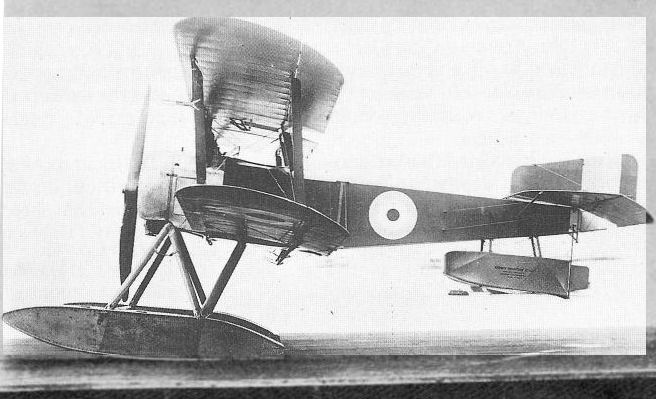

Fairey-built Hamble Baby N1452 with 110/130 hp Clerget. The full-span trailing-edge flaps can be seen as well as the differences between Falrey- and Parnall-built examples.

Fairey Hamble Baby, showing evidence of Lewis gun associated with centre section cut-out and attachment for bomb-carrier under fuselage. -

H.Taylor - Fairey Aircraft since 1915 /Putnam/

This completed production Hamble Baby - probably N1320 (F.130) - has the Fairey trademark’ square-cut fin and rudder and Fairey-designed floats.

Old soldiers never die and neither it seems do good aircraft designs, as evidenced by the 1916 Fairey Hamble Baby resurrection of the little Sopwith floatplanes sired by the 1914 Schneider Tabloid. In essence, the Hamble Baby was little more than the earlier Sopwith Baby except in one respect. The difference lay in the use of the Fairey Camber Changing gear, which in effect was a system of right and left side, half span trailing edge flaps that could be made to work in unison for increased lift, or differentially for lateral, or roll control. Incidentally, this system, which allowed the machine to fly with higher loads than previously possible, was to be employed on every subsequent Fairey biplane up to and including their Swordfish. The first of the Fairey machines completed prior to the end of 1916 was, in fact, a converted Sopwith Baby, this being followed six months later by the first production Hamble Babys, these going into service as single-seat anti-submarine patrollers during the summer of 1917. Powered by either a 110hp or 130hp Clerget, the Hamble Baby had a top speed of 90mph at 2.000 feet to which height it could climb in 5 minutes 30 seconds. Its defensive armament comprised a single, synchronised Lewis gun, while its offensive warload was two underslung 65lb bombs. As was often the case, Faireys themselves only produced 50 of the total 180 examples built, the 130 lion's share coming from sub-contractor Parnall & Sons, Bristol. -

H.King - Sopwith Aircraft 1912-1920 /Putnam/

Fairey Hamble Baby, with its distinctive tin and rudder and camber-changing flaps clearly in evidence

-

K.Wixey - Parnall Aircraft since 1914 /Putnam/

Used as an anti-submarine patrol seaplane, the Hamble Baby played a mundane, but important part in the war at sea. This Fairey-built machine has two 65-lb bombs slung beneath the centre fuselage.

-

J.Bruce - British Aeroplanes 1914-1918 /Putnam/

A Fairey-built Hamble Baby. The tailplane span of these aircraft was over a foot greater than that of Sopwith-built aircraft.

-

K.Delve - World War One in the Air /Crowood/

Sopwith Baby - the type was designed as a scout-bomber to operate from seaplane carriers in the Mediterranean and around the UK. N1452, here, was delivered to Calshot in October.

-

K.Wixey - Parnall Aircraft since 1914 /Putnam/

Believed to be N1970, this Parnall-built Hamble Baby reveals clearly the retained Sopwith design of vertical tail surfaces and floats.

-

H.King - Sopwith Aircraft 1912-1920 /Putnam/

The Parnall-built Hamble Baby retained Sopwith-designed fin and rudder and floats, but had Fairey-designed wings with camber-changing flaps.

-

C.Owers - The Fighting America Flying Boats of WWI Vol.1 /Centennial Perspective/ (22)

This De Havilland D.H.4, A7830, is readily recognised by its striking black and white colour scheme. Allocated to Great Yarmouth for special service in December 1917, it attacked a U-Boat on 21 March 1918, dropping two 65-lb bombs. The pilot on this occasion was the redoubtable Wing Cmdr Charles Rumney Samson with AM Radcliffe in the rear cockpit. This biplane survived into the 1920s.There is a Fairey Hamble Baby and what appears to be a standard Sopwith Baby sharing the hard stand with A7830. A twin-engine flying boat is in the far background. C.F. Snowden Gamble considered the D.H.4 one of the most successful two-seaters issued to Great Yarmouth in 1917.

Другие самолёты на фотографии: De Havilland D.H.4 - Великобритания - 1916Sopwith Schneider/Baby - Великобритания - 1914

-

K.Wixey - Parnall Aircraft since 1914 /Putnam/

In this view of Parnall Hamble Baby Convert N2002 (Parnall c/n P.1/17), the Sopwith lineage is obvious. Also noticeable is the Parnall trade mark on the side of the rear fuselage.

Of the 130 Hamble Babies built by Parnall under sub-contract, 74 were fitted with land undercarriages and called Hamble Baby Converts. -

K.Wixey - Parnall Aircraft since 1914 /Putnam/

Hamble Baby Convert N2059 nearing completion in the Coliseum works of Parnall at Park Row, Bristol. The Parnall c/n P.1/74 appears beneath serial number. An Avro 504 is under construction in the background.

-

J.Bruce - British Aeroplanes 1914-1918 /Putnam/

Parnall-built Hamble Baby. Note the retention of the original Sopwith-type fin.

-

K.Wixey - Parnall Aircraft since 1914 /Putnam/

This view of the Parnall Hamble Baby Convert shows to advantage the wide-track undercarriage in which skids and axle simply replaced the floats, and rounded wingtips. Most of these aeroplanes were used as trainers by the RNAS.

-

H.Taylor - Fairey Aircraft since 1915 /Putnam/

The partially-assembled prototype Hamble Baby, which was originally Sopwith Baby 8134.

-

O.Thetford - British Naval Aircraft since 1912 /Putnam/

Fairey Hamble Baby

H.Taylor Fairey Aircraft since 1915 (Putnam)

Hamble Baby

In terms of new design thinking, the most important aircraft built by Fairey in the years before the legendary Fox was not one of their own, but a redesigned version of the Sopwith Baby single-seat seaplane. This variant, named the Hamble Baby, was the first production aircraft to be fitted with a practical system of adjustable trailing-edge flaps as a means of increasing lift for take-off and landing. The Fairey patent camber-changing gear, as the system was to be known for a decade or more afterwards, was fitted to most of the company’s biplanes up to and including the Seafox of the late 1930s and, in a simplified form involving only the ailerons, to the Swordfish.

As Oliver Stewart put it in the narrative which accompanied Leonard Bridgman’s evocative drawings for The Clouds Remember, the Hamble Baby demonstrated the fact that ‘in aviation there is nothing new under the sun’. Writing in the early 1930s, he commented that future historians should remember that the Hamble Baby ‘showed the way to developments which were to enable much higher speeds to be reached in the future without additional risks and without flying difficulties’.

This is, perhaps, an overstatement of the importance of the advance represented by the Fairey flap gear as such. This certainly worked to special advantage in the case of seaplanes, because the increased lift at lower speeds enabled them to get ‘on top of the water’ with greater ease; more power was needed to do this, in some conditions of wind and sea, than to become airborne. But many designers and others considered that the increased lift provided by these somewhat primitive flap systems was more than offset by the weight penalties and the complications and control loadings involved. Few other British manufacturers attempted to make use of high-lift devices during the two decades following the appearance of the Hamble Baby.

The Sopwith Baby, a more powerful scouting and bombing derivative of the Schneider seaplane and the earlier Tabloid, was being flown operationally in 1916 at loads which caused the lift-off speed to be too high for safety in any but favourable wind/sea conditions. The float undercarriage was sometimes breaking up under wave impact before the aircraft could become airborne while carrying the anti-submarine and other loads which were possible with the power of the Clerget rotary engine. Two 65-lb bombs in racks under the fuselage had to be lifted - as well as a forward-firing synchronized Lewis gun and its ammunition, emergency rations, a sea anchor, and accommodation for the carrier pigeons which in those days stood-in for non-existent lightweight radio.

The most immediately obvious way of dealing with the difficulty was to replace the existing conventional thin-section wings of the Baby with others of a more heavily cambered high-lift section. This approach was tried in different forms not only by Blackburn, who had by then taken over the production of the Baby from Sopwith, but also by Sqn-Cdr John Seddon of the Experimental Construction Department (ECD) of the Marine Experimental Aircraft Depot at Port Victoria, Isle of Grain. Seddon used aerofoils based on wind-tunnel work done at the National Physical Laboratory, together with a considerable modification of the wing arrangement of the Baby.

To a degree, the resultant aircraft, the Port Victoria P.V.1 was a success; it was taken off at a weight some 450 lb higher than that of the standard Baby, but, expectedly, its maximum speed was reduced from 95-100 mph to 77 mph. The ECD was to continue development on these lines with the P.V.2, and a version of this appeared to be promising and was liked; however, it was overtaken, in effect, by the Hamble Baby which was by then (1917) going into quantity production.

The Fairey approach to the problem was nothing if not radical for the era. The plan was to hinge the trailing edges of each wing so that these ‘margins’ could be lowered to increase the lift while continuing to be available for use, with differential action, as ailerons. By thus providing adjustable camber, some, at least, of both slow-speed and high-speed requirements could be met.

This was not, of course, the first attempt to provide a variable-camber system. The Royal Aircraft Factory had done experiments before the war, and, as Harald Penrose points out in the second volume of his British aviation history, the Varioplane Company had been working for some years on a system for flexing a wing surface The Fairey approach, however, he writes, ‘was that of a practical engineer, using one abrupt change of camber and then applying an ingenious geometry of cable operation to give either simultaneous or differential application of the flap’.

After discussions about the problem with Sq-Cdr Seddon, Fairey were given a contract for the construction and test of six sets of wings for the Baby. Each set was to be of different section. The variable-camber principle was introduced in the second set to be designed and made by Fairey. For the development work, a Sopwith-built Baby (8134) was delivered to the Fairey works at Clayton Road, Hayes. This, as F.129, was eventually fitted with redesigned wings with a span 2 ft longer than standard and increased chord, and with rounded wingtips in place of the blunt planform of the original Baby.

Photographs of 8134 suggest that it was flown both as a landplane and a seaplane and that it retained in both forms, at least initially, the original rounded Sopwith fin and rudder. All production Hamble Babies from Fairey were fitted with a redesigned tail unit, with a near-square outline, following the pattern of that on the Campania. This empennage outline was to be a Fairey ‘trademark’ for a decade or more until the appearance of the IIIF. Fairey-designed main floats were used and a larger-capacity tail-float was also fitted.

The first of several British and US patent specifications covering the principle and method of operation of the camber gear was applied for in provisional form on 19 May, 1916, and the complete specification (No.132,541) was dated 19 December, 1916. In this specification it was proposed that the control column should be telescopically adjustable in length by means of a handwheel-operated rack-and-pinion gear. The flaps were moved differentially for lateral control by a cable system operated by a control-wheel and drum on this column. As the column was lengthened, the cable system would be tightened against spring (or bungee) loading, pulling down the flaps symmetrically while retaining adequate differential action except at large flap angles.

Whether this system, or one of the other patented methods of operation, was that used on the Hamble Baby can only be guessed - but the principle behind all such systems was similar. When officially tested from Hamble by Maurice Wright, the prototype Hamble Baby demonstrated its ability to lift two 65-lb bombs with much greater ease than the standard Baby, though the lateral control was inevitably a good deal heavier.

Needless to say, there had been no shortage of problems in the design and development of the camber-changing device. The pressure distribution over the wing did not turn out as expected, so the movement of the centre of pressure had to be watched carefully; and there were very heavy stresses in the operating gear. The early systems had to be operated with very low gear ratios so that no rapid changes of flap angle would be possible.

The Hamble Baby was produced at Hayes and Hamble by Fairey and, under a sub-contract arrangement, by Parnall & Sons at Bristol - the latter company making very much the greater number if their Hamble Baby Converts are included. These variants were fitted with land undercarriages and were used for training by the RNAS - notably at Cranwell. The Converts had their floats replaced by skids, to which the straight axle for the wheels was attached by rubber bungee cords; as the geometry of the undercarriage struts remained unchanged, the result was a very wide-track undercarriage which must have been appreciated for training work.

The Parnall-built Babies, including the Converts, could be distinguished from Fairey-built aircraft by the fact that they retained the Sopwith fins and rudders and, in the case of the seaplanes, the Sopwith floats. All were powered by Clerget nine-cylinder air-cooled rotary engines, but there is some difference in the record of the proportions using the 110 hp and the 130 hp versions of the engine. Of the 180 Hamble Babies and Converts built, the first 50 - including 30 by Parnall and 20 by Fairey - probably had the lower-powered Clerget, but at least one record says that they were fitted only to the first ten of the 50 built by Fairey - N1320-1339 (F.130-149) and N1450-1479 (F.150-179). Parnall built 130 with the serials N1190-1219 and N1960-2059, including 74 Converts (N1986-2059). Each one cost the taxpayer about ?2,100 excluding armament and instruments.

Apart from the landplane Convert the Hamble Baby was employed on work similar to that done by the standard Sopwith Baby. They were based for the most part at coastal stations in Britain and in Mediterranean areas on anti-submarine patrolling and attacking duties. They operated from the RNAS stations at Fishguard, Calshot and Cattewater in Britain; from Santa Maria di Leuca, near Taranto, in Italy; from Suda Bay (Crete), Syra, Talikna (Lemnos) and Skyros in the Aegean; and from Port Said and Alexandria in Egypt. They flew from at least one seaplane carrier - HMS Empress, a converted Channel steamer, from which, while in the eastern Mediterranean late in 1917, her two Hamble Babies and four Sopwith Babies made several bombing attacks on Turkish installations in Palestine.

Span 27 ft 9 in (6.46 m); length 23 ft 4 in (711 m); height 9 ft 6 in (2-89 m); total wing area 302 sq ft (28-1 sq m). Empty weight 1,386 lb (629 kg); military load 185 lb (84 kg); pilot 180 lb (82 kg); fuel and oil, 195 lb (89 kg); loaded weight 1,946 lb (883 kg). Maximum speed at 2,000 ft (610 m) 90 mph (145 km/h). Climb to 2,000 ft (610 m) 5 min 30 sec; to 6,500 ft (1,981 m) 25 min; service ceiling 7,600 ft (2,316 m). Endurance 2 hr.

Описание: