Книги

Putnam

G.Duval

British Flying-Boats and Amphibians 1909-1952

52

G.Duval - British Flying-Boats and Amphibians 1909-1952 /Putnam/

A.D. Flying-boat (1915/17)

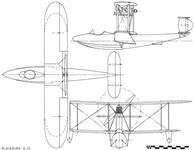

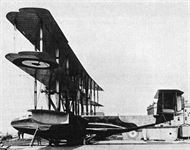

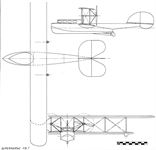

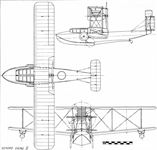

The A.D. Flying-Boat was built to a design of the Air Department of the Admiralty as a patrol and reconnaissance machine to Specification N.2A. The design team consisted of Harold Yendall, Harold Bolas, Clifford Tinson, and Lt.-Col. Linton Hope, the latter responsible for the construction layout of the monocoque hull. Construction of two prototypes commenced in October 1915, the serials allocated being No. 1412 and No. 1413, contracts having been placed with Pemberton-Billing, Ltd, for the superstructure, and with May, Harden and May, for the hulls. A two-seater biplane, the A.D. boat was of mixed wooden construction, fabric covered and wire braced, with the mainplanes arranged to fold forward for shipboard stowage. A biplane tail unit was fitted, with twin fins and rudders, the lower plane made as a watertight unit as it was awash during taxying. The upper tailplane had an inverted aerofoil and a negative angle of incidence, to prevent a tail-heavy trim change when the engine was throttled back. In its original form, the first prototype, No. 1412, was powered by a pusher Sunbeam Nubian engine of 150 h.p. driving a 10-foot diameter four-bladed propeller, and with this power unit No. 1412 underwent its first trials in the summer of 1916. The results were not promising, for the machine suffered from porpoising and poor rudder control, and the design weight had already been exceeded by 500 pounds. At the suggestion of Sqdn. Comm. Travers, the step was moved 2 feet aft to improve water handling, but this had little effect, and as a result of porpoising trials held at Southampton in August 1916, by a Seaplane Research Team under G. S. Baker, o.b.e., a trials report stated that the machine was unsatisfactory, further trials being cancelled by the Air Department. Work continued on the machine throughout the winter of 1916, the most obvious changes being the installation of a 200 h.p. Hispano-Suiza engine, shorter span ailerons, and greatly enlarged wing-tip floats. In this form, No. 1412 was tested at Southampton on 12 and 15 March, 1917, and performed satisfactorily. Production was soon under way, and on 5 September, 1917, the first production machine, N1520, was the subject of a satisfactory trials report from the Isle of Grain.

However, engine trouble proved to be the main reason for the A.D. boat’s eventual downfall, apart from the fact that it was not an easy machine to handle both in water manoeuvring and on take-off. The geared Hispano- Suiza engine, French-built, was vibrating and failing in flight, the same faults that were giving cause for anxiety with the S.E.5a. In July 1917, No. 1412 was fitted with a 150 h.p. direct-drive Hispano-Suiza engine in an attempt to remedy the situation, but with this power unit the performance was impaired. February 1918 saw No. 1412 fitted with a 200 h.p. Sunbeam Arab, but this engine performed no better in the A.D. boat than in other aircraft to which it had been fitted, and it, too, was shelved. In mid-1918, a production machine, N1525, was fitted with a Wolseley Python engine of 211 h.p., and later with a 200 h.p. Wolseley Viper, neither installation being satisfactory. Most of the A.D. boats produced other than those mentioned went into storage, with the exception of N1719 and N1712 which were allocated to the Isle of Grain for experimental purposes. In 1921, Harry Busteed and G. Bentley Dacre, both by now senior R.A.F. officers, used N1719 for successful hydrofoil experiments. The total A.D. boat production consisted of the two prototypes and twenty-seven production machines, and the type was declared obsolete in the late autumn of 1918. In June 1919, ten A.D. boats were re-purchased by Supermarines, lately Pemberton-Billing, Ltd, and after fitment of a 160 h.p. Beardmore engine and some modification became civilianised as the Supermarine Channel, the first Channel being a conversion of N1529. Further purchases of A.D. boats were made later, to a total of some nineteen machines in all.

SPECIFICATION

Power Plant:

150 h.p. Sunbeam Nubian

200 h.p. Hispano-Suiza

150 h.p. Hispano-Suiza

200 h.p. Wolseley Python

200 h.p. Wolseley Viper

200 h.p. Sunbeam Arab

Span: 50 feet 4 inches. Folded: 14 feet

Length: 30 feet 7 inches. Folded: 42 feet 3 inches

Weight Loaded:

2,880 pounds (No. 1412) (200 h.p. Hispano-Suiza)

3,388 pounds (N1525) (200 h.p. Wolseley Python)

Total Area: 479 square feet

Max. Speed: 87,5 - 100 m.p.h., depending upon loaded weight and engine installed

Endurance: 3,5 - 5 hours, as above

Armament:

Production - one .303-inch Lewis gun

Type 54A wireless set fitted

The A.D. Flying-Boat was built to a design of the Air Department of the Admiralty as a patrol and reconnaissance machine to Specification N.2A. The design team consisted of Harold Yendall, Harold Bolas, Clifford Tinson, and Lt.-Col. Linton Hope, the latter responsible for the construction layout of the monocoque hull. Construction of two prototypes commenced in October 1915, the serials allocated being No. 1412 and No. 1413, contracts having been placed with Pemberton-Billing, Ltd, for the superstructure, and with May, Harden and May, for the hulls. A two-seater biplane, the A.D. boat was of mixed wooden construction, fabric covered and wire braced, with the mainplanes arranged to fold forward for shipboard stowage. A biplane tail unit was fitted, with twin fins and rudders, the lower plane made as a watertight unit as it was awash during taxying. The upper tailplane had an inverted aerofoil and a negative angle of incidence, to prevent a tail-heavy trim change when the engine was throttled back. In its original form, the first prototype, No. 1412, was powered by a pusher Sunbeam Nubian engine of 150 h.p. driving a 10-foot diameter four-bladed propeller, and with this power unit No. 1412 underwent its first trials in the summer of 1916. The results were not promising, for the machine suffered from porpoising and poor rudder control, and the design weight had already been exceeded by 500 pounds. At the suggestion of Sqdn. Comm. Travers, the step was moved 2 feet aft to improve water handling, but this had little effect, and as a result of porpoising trials held at Southampton in August 1916, by a Seaplane Research Team under G. S. Baker, o.b.e., a trials report stated that the machine was unsatisfactory, further trials being cancelled by the Air Department. Work continued on the machine throughout the winter of 1916, the most obvious changes being the installation of a 200 h.p. Hispano-Suiza engine, shorter span ailerons, and greatly enlarged wing-tip floats. In this form, No. 1412 was tested at Southampton on 12 and 15 March, 1917, and performed satisfactorily. Production was soon under way, and on 5 September, 1917, the first production machine, N1520, was the subject of a satisfactory trials report from the Isle of Grain.

However, engine trouble proved to be the main reason for the A.D. boat’s eventual downfall, apart from the fact that it was not an easy machine to handle both in water manoeuvring and on take-off. The geared Hispano- Suiza engine, French-built, was vibrating and failing in flight, the same faults that were giving cause for anxiety with the S.E.5a. In July 1917, No. 1412 was fitted with a 150 h.p. direct-drive Hispano-Suiza engine in an attempt to remedy the situation, but with this power unit the performance was impaired. February 1918 saw No. 1412 fitted with a 200 h.p. Sunbeam Arab, but this engine performed no better in the A.D. boat than in other aircraft to which it had been fitted, and it, too, was shelved. In mid-1918, a production machine, N1525, was fitted with a Wolseley Python engine of 211 h.p., and later with a 200 h.p. Wolseley Viper, neither installation being satisfactory. Most of the A.D. boats produced other than those mentioned went into storage, with the exception of N1719 and N1712 which were allocated to the Isle of Grain for experimental purposes. In 1921, Harry Busteed and G. Bentley Dacre, both by now senior R.A.F. officers, used N1719 for successful hydrofoil experiments. The total A.D. boat production consisted of the two prototypes and twenty-seven production machines, and the type was declared obsolete in the late autumn of 1918. In June 1919, ten A.D. boats were re-purchased by Supermarines, lately Pemberton-Billing, Ltd, and after fitment of a 160 h.p. Beardmore engine and some modification became civilianised as the Supermarine Channel, the first Channel being a conversion of N1529. Further purchases of A.D. boats were made later, to a total of some nineteen machines in all.

SPECIFICATION

Power Plant:

150 h.p. Sunbeam Nubian

200 h.p. Hispano-Suiza

150 h.p. Hispano-Suiza

200 h.p. Wolseley Python

200 h.p. Wolseley Viper

200 h.p. Sunbeam Arab

Span: 50 feet 4 inches. Folded: 14 feet

Length: 30 feet 7 inches. Folded: 42 feet 3 inches

Weight Loaded:

2,880 pounds (No. 1412) (200 h.p. Hispano-Suiza)

3,388 pounds (N1525) (200 h.p. Wolseley Python)

Total Area: 479 square feet

Max. Speed: 87,5 - 100 m.p.h., depending upon loaded weight and engine installed

Endurance: 3,5 - 5 hours, as above

Armament:

Production - one .303-inch Lewis gun

Type 54A wireless set fitted

Blackburn N.IB (1918)

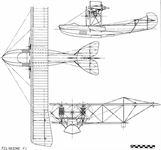

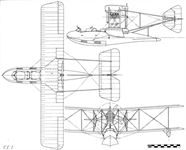

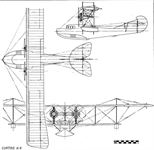

Designed to the same Air Board Specification as the Supermarine Baby, work commenced on the Blackburn N.1B at the Leeds factory in mid-1918. The hull, of Linton Hope design, was similar to the Baby, being of the usual monocoque construction with external side fins, which extended aft to the main step amidships, and having a small auxiliary step mid-way towards the stern. The bows were longer and more pointed than those of the Baby, however, and the rear part of the hull had a distinctive upward curve towards the stern. The complete machine was to be a single-seat single-bay biplane, the lower mainplane mounted on the hull top and braced from the main step by Vee-struts. A 200 h.p. Hispano-Suiza pusher engine, driving a two-bladed propeller was to be mounted on struts high up in the centre section. The tail unit design was of biplane layout, with twin rudders, the upper plane of inverted camber as on the A.D. Boat and the Supermarine Baby. Large wingtip floats were to be attached directly to the lower wing undersurface. Some difficulties were encountered during hull construction; the American elmwood required was late in delivery, and eventually other woods had to be be used. The hull was then found to require extra stiffening, and eventually, although good progress was made, the coming of the Armistice brought the development to a halt. The completed hull was put into storage. In 1923, an inspection found it still in good condition, and fitted with a new engine and flight structure it was entered for the Schneider Trophy as the Blackburn Pellet.

SPECIFICATION

Power Plant: One 200 h.p. Hispano-Suiza

Span: 34 feet 10 inches

Length: 28 feet 3 1/2 inches

Weight Loaded (estimated): 2,390 pounds

Total Area: 376 square feet

Max. Speed (estimated): 114 m.p.h.

Endurance (estimated): 3 hours

Armament: One free-mounted Lewis gun

Serials Allotted: N56-N58

Designed to the same Air Board Specification as the Supermarine Baby, work commenced on the Blackburn N.1B at the Leeds factory in mid-1918. The hull, of Linton Hope design, was similar to the Baby, being of the usual monocoque construction with external side fins, which extended aft to the main step amidships, and having a small auxiliary step mid-way towards the stern. The bows were longer and more pointed than those of the Baby, however, and the rear part of the hull had a distinctive upward curve towards the stern. The complete machine was to be a single-seat single-bay biplane, the lower mainplane mounted on the hull top and braced from the main step by Vee-struts. A 200 h.p. Hispano-Suiza pusher engine, driving a two-bladed propeller was to be mounted on struts high up in the centre section. The tail unit design was of biplane layout, with twin rudders, the upper plane of inverted camber as on the A.D. Boat and the Supermarine Baby. Large wingtip floats were to be attached directly to the lower wing undersurface. Some difficulties were encountered during hull construction; the American elmwood required was late in delivery, and eventually other woods had to be be used. The hull was then found to require extra stiffening, and eventually, although good progress was made, the coming of the Armistice brought the development to a halt. The completed hull was put into storage. In 1923, an inspection found it still in good condition, and fitted with a new engine and flight structure it was entered for the Schneider Trophy as the Blackburn Pellet.

SPECIFICATION

Power Plant: One 200 h.p. Hispano-Suiza

Span: 34 feet 10 inches

Length: 28 feet 3 1/2 inches

Weight Loaded (estimated): 2,390 pounds

Total Area: 376 square feet

Max. Speed (estimated): 114 m.p.h.

Endurance (estimated): 3 hours

Armament: One free-mounted Lewis gun

Serials Allotted: N56-N58

Burney X.1, X.2, and X.3 (1911-1913)

In the summer of 1911, Lieut. Charles Burney, r.n. (later Sir Charles Burney, of Airship R.100 fame) obtained Admiralty sanction for the British and Colonial Aeroplane Company to undertake design of a ship-borne aircraft employing hydrofoils to achieve take-off and landing on rough water. Burney had studied the works of the Italian pioneers Foriannini and Guidoni on the application of hydrofoils to improve the performance of fast motor boats, and was convinced that the hydrofoil had applications to the design of marine aircraft. Experiments began in the autumn of 1911, when Burney co-operated with Howard Pixton in a series of over-water flights from Hayling Island in a Bristol Boxkite equipped with flotation bags. In December, Frank Barnwell was appointed experimental designer for the project, taking up his duties in a private house at Filton which became known as ‘X’ Department, and was shrouded in secrecy.

X.1

In collaboration with Burney, Barnwell produced the first design study, known as the X.1 This was a modification of the Gordon England biplane (G.E.1). The original 50 h.p. Clerget engine was to be replaced by a more powerful eight-cylinder E.N.V., driving a shaft between the cylinder banks with a Hele-Shaw clutch at each end. The front clutch was to drive a normal tractor propeller, while the rear clutch drove a bevel gearbox from which two shafts extended downwards inside tubular undercarriage legs fitted with groups of hydrofoils. At the bottom of each leg there was a further bevel drive to a water propeller. A third strut, also equipped with hydrofoils, was fitted under the rear fuselage. These grouped hydrofoils were called ‘hydropeds’. The idea was that, when driven by the water propellers, the craft would rise out of the water on the hydropeds until there was sufficient clearance for the flight propeller to be clutched in, and take-off would then be made. While at rest on the water, the aircraft would have floated on five torpedo-shaped air bags, which were not, however, intended to act as planing surfaces.

In January 1912, Barnwell, now joined by an assistant, Clifford Tinson, proposed that the biplane arrangement should give way to a monoplane wing of startling ingenuity. This was to be pneumatic, formed of eight span-wise air bags arranged to fit into a suitable wing section and capable of inflation to high pressure. The aerofoil profile would be maintained by flat spruce strips, forming ribs, and hinged at leading and trailing edges, with bicycle spokes acting as tension members between the upper and lower strips. Externally braced, the wing was to be fitted with ailerons, also inflatable. Storage would be simplified by deflation of the entire wing structure. Unfortunately, the rubberised canvas of the day proved to be too weak and too heavy for the demands made upon it, and the idea had to be shelved.

X.2

In February 1912, a new design, the X.2, was produced, and construction commenced. In this, the flotation bags were eliminated, and the fuselage was built as a proper hull, planked with mahogany and covered with varnished sailcloth, a normal monoplane wing being fitted. This craft, Works No. 92, was built in the experimental shop at Filton, and equipped with side-by-side dual controls. The clutches and hydropeds developed for X.1 were used, but the engine was a water-cooled radial Canton-Unne of 80 h.p. On 9 May, 1912, X.2 was put aboard the lighter Sarah at Avonmouth, and taken to Dale, near Milford Haven. After overcoming initial leakages, taxying under power from the water screws was attempted, and later the craft was towed behind a torpedo boat. Despite modification, it proved impossible to prevent the machine from heeling over when the water screws were clutched in during towing. Eventually, in September 1912, it was decided to rely upon towing for the preliminary air tests. The engine was replaced by 500 lb of ballast, and on 21 September, X.2 was towed into a 30-knot wind with Lieut. G. Bentley Dacre, R.N., in the cockpit. At an airspeed of 42 knots, it rose clear of the water in a climbing attitude, but premature release by the towline party caused it to stall and crash, though without injury to Dacre.

X.3

The Admiralty agreed to continue the experiments, and work commenced on an improved design, the X.3. The engine fitted was a 200 h.p. Canton-Unne, and although similar to X.2 in most respects, this machine had wingtip floats with small hydrofoils under them. The hull frame, constructed at Filton, was then transported to Saunders at Cowes for covering with their patent ‘Consuta’ sewn plywood. To overcome torque reaction, the water screws were mounted back to back on a central pylon, so that they rotated in opposite directions. This machine, Works No. 159, was shipped to Dale in August 1913, and towing tests were very satisfactory. The nose dipped when the flight propeller was clutched in, - so to overcome this Barnwell designed an elevator, located in front of the mainplane and linked to the propeller clutch control. However, before the device could be fitted, X.3 came to grief while taxying, when it was wrecked on a sandbank.

With this mishap, the experiments came to an end, but the principle of the hydrofoil was employed by Burney in his invention of the paravane for minesweeping. In 1930, the Piaggio Pegna P.C.7 racing seaplane project utilised an almost identical layout to X.3, but also was a failure due to mechanical problems with the water screw.

SPECIFICATION

Power Plant:

X.1 (project) - 60 h.p. E.N.V. Vee-eight engine

X.2 - 80 h.p. Canton-Unne water-cooled radial engine

X.3 - 200 h.p. Canton-Unne engine

Span:

X.1 - 34 feet

X.2 - 55 feet 9 inches

X.3 - 57 feet 10 inches

Length:

X.1 - 30 feet

X.2 - 30 feet 8 inches

X.3 - 36 feet 8 inches

Wing Area:

X.1 - 325 square feet

X.2 - 480 square feet

X.3 - 500 square feet

In the summer of 1911, Lieut. Charles Burney, r.n. (later Sir Charles Burney, of Airship R.100 fame) obtained Admiralty sanction for the British and Colonial Aeroplane Company to undertake design of a ship-borne aircraft employing hydrofoils to achieve take-off and landing on rough water. Burney had studied the works of the Italian pioneers Foriannini and Guidoni on the application of hydrofoils to improve the performance of fast motor boats, and was convinced that the hydrofoil had applications to the design of marine aircraft. Experiments began in the autumn of 1911, when Burney co-operated with Howard Pixton in a series of over-water flights from Hayling Island in a Bristol Boxkite equipped with flotation bags. In December, Frank Barnwell was appointed experimental designer for the project, taking up his duties in a private house at Filton which became known as ‘X’ Department, and was shrouded in secrecy.

X.1

In collaboration with Burney, Barnwell produced the first design study, known as the X.1 This was a modification of the Gordon England biplane (G.E.1). The original 50 h.p. Clerget engine was to be replaced by a more powerful eight-cylinder E.N.V., driving a shaft between the cylinder banks with a Hele-Shaw clutch at each end. The front clutch was to drive a normal tractor propeller, while the rear clutch drove a bevel gearbox from which two shafts extended downwards inside tubular undercarriage legs fitted with groups of hydrofoils. At the bottom of each leg there was a further bevel drive to a water propeller. A third strut, also equipped with hydrofoils, was fitted under the rear fuselage. These grouped hydrofoils were called ‘hydropeds’. The idea was that, when driven by the water propellers, the craft would rise out of the water on the hydropeds until there was sufficient clearance for the flight propeller to be clutched in, and take-off would then be made. While at rest on the water, the aircraft would have floated on five torpedo-shaped air bags, which were not, however, intended to act as planing surfaces.

In January 1912, Barnwell, now joined by an assistant, Clifford Tinson, proposed that the biplane arrangement should give way to a monoplane wing of startling ingenuity. This was to be pneumatic, formed of eight span-wise air bags arranged to fit into a suitable wing section and capable of inflation to high pressure. The aerofoil profile would be maintained by flat spruce strips, forming ribs, and hinged at leading and trailing edges, with bicycle spokes acting as tension members between the upper and lower strips. Externally braced, the wing was to be fitted with ailerons, also inflatable. Storage would be simplified by deflation of the entire wing structure. Unfortunately, the rubberised canvas of the day proved to be too weak and too heavy for the demands made upon it, and the idea had to be shelved.

X.2

In February 1912, a new design, the X.2, was produced, and construction commenced. In this, the flotation bags were eliminated, and the fuselage was built as a proper hull, planked with mahogany and covered with varnished sailcloth, a normal monoplane wing being fitted. This craft, Works No. 92, was built in the experimental shop at Filton, and equipped with side-by-side dual controls. The clutches and hydropeds developed for X.1 were used, but the engine was a water-cooled radial Canton-Unne of 80 h.p. On 9 May, 1912, X.2 was put aboard the lighter Sarah at Avonmouth, and taken to Dale, near Milford Haven. After overcoming initial leakages, taxying under power from the water screws was attempted, and later the craft was towed behind a torpedo boat. Despite modification, it proved impossible to prevent the machine from heeling over when the water screws were clutched in during towing. Eventually, in September 1912, it was decided to rely upon towing for the preliminary air tests. The engine was replaced by 500 lb of ballast, and on 21 September, X.2 was towed into a 30-knot wind with Lieut. G. Bentley Dacre, R.N., in the cockpit. At an airspeed of 42 knots, it rose clear of the water in a climbing attitude, but premature release by the towline party caused it to stall and crash, though without injury to Dacre.

X.3

The Admiralty agreed to continue the experiments, and work commenced on an improved design, the X.3. The engine fitted was a 200 h.p. Canton-Unne, and although similar to X.2 in most respects, this machine had wingtip floats with small hydrofoils under them. The hull frame, constructed at Filton, was then transported to Saunders at Cowes for covering with their patent ‘Consuta’ sewn plywood. To overcome torque reaction, the water screws were mounted back to back on a central pylon, so that they rotated in opposite directions. This machine, Works No. 159, was shipped to Dale in August 1913, and towing tests were very satisfactory. The nose dipped when the flight propeller was clutched in, - so to overcome this Barnwell designed an elevator, located in front of the mainplane and linked to the propeller clutch control. However, before the device could be fitted, X.3 came to grief while taxying, when it was wrecked on a sandbank.

With this mishap, the experiments came to an end, but the principle of the hydrofoil was employed by Burney in his invention of the paravane for minesweeping. In 1930, the Piaggio Pegna P.C.7 racing seaplane project utilised an almost identical layout to X.3, but also was a failure due to mechanical problems with the water screw.

SPECIFICATION

Power Plant:

X.1 (project) - 60 h.p. E.N.V. Vee-eight engine

X.2 - 80 h.p. Canton-Unne water-cooled radial engine

X.3 - 200 h.p. Canton-Unne engine

Span:

X.1 - 34 feet

X.2 - 55 feet 9 inches

X.3 - 57 feet 10 inches

Length:

X.1 - 30 feet

X.2 - 30 feet 8 inches

X.3 - 36 feet 8 inches

Wing Area:

X.1 - 325 square feet

X.2 - 480 square feet

X.3 - 500 square feet

Porte/Felixstowe F.1 (1915)

<...>

Early in 1915, Porte was stationed at Felixstowe, and flew the H.4 operationally, being therefore well qualified to understand its shortcomings. In the spring of 1915, he began a series of experiments, officially approved, with the aim of producing a seaworthy and operationally useful flying-boat. This involved re-designing and fitting of completely new hulls to four H.4s, Nos. 950, 1230, 3545, and 3569, culminating in the modification of H.4 No. 3580 with a new hull incorporating all the structural and hydrodynamic features developed to high efficiency in the preceding experiments. This hull, built at Felixstowe, was named the Porte 1, the complete machine being designated F.1, the first of the line of Felixstowe ‘F’ boats. The wings and tail unit of the F.1 were standard H.4 components, but its chief interest lay in the hull construction, which differed little from the fuselages of most contemporary landplanes. Of strong cross-braced box girder configuration, it was fitted with an external vee-shaped planing bottom and long side fins. Overall, the hull was 36 feet 2 inches in length, with a maximum beam of 8 feet, and unlike its predecessors, possessed open cockpits. Originally the hull had only one step, but performance requirements were not met, so a second and finally a third step were added. The machine was powered by two 150 h.p. Hispano-Suiza engines driving tractor propellers.

SPECIFICATION

Power Plant:

F.1 - Two 150 h.p. Hispano-Suiza

H.4 - Two 90 h.p. Curtiss, or two 100 h.p. Anzani

Span: F.1 and H.4 - 72 feet

Length:

F.1 - 39 feet 2 inches

H.4 - 35 feet

Weight Loaded:

H.4 - 4,983 pounds

Total Area: F.1 and H.4 - 842 square feet

Max. Speed:

F.1 - 85 m.p.h.

H.4 - 75 m.p.h.

Endurance: Not available

Armament: F.1 and H.4 - One or two Lewis guns, light bombs only

<...>

Early in 1915, Porte was stationed at Felixstowe, and flew the H.4 operationally, being therefore well qualified to understand its shortcomings. In the spring of 1915, he began a series of experiments, officially approved, with the aim of producing a seaworthy and operationally useful flying-boat. This involved re-designing and fitting of completely new hulls to four H.4s, Nos. 950, 1230, 3545, and 3569, culminating in the modification of H.4 No. 3580 with a new hull incorporating all the structural and hydrodynamic features developed to high efficiency in the preceding experiments. This hull, built at Felixstowe, was named the Porte 1, the complete machine being designated F.1, the first of the line of Felixstowe ‘F’ boats. The wings and tail unit of the F.1 were standard H.4 components, but its chief interest lay in the hull construction, which differed little from the fuselages of most contemporary landplanes. Of strong cross-braced box girder configuration, it was fitted with an external vee-shaped planing bottom and long side fins. Overall, the hull was 36 feet 2 inches in length, with a maximum beam of 8 feet, and unlike its predecessors, possessed open cockpits. Originally the hull had only one step, but performance requirements were not met, so a second and finally a third step were added. The machine was powered by two 150 h.p. Hispano-Suiza engines driving tractor propellers.

SPECIFICATION

Power Plant:

F.1 - Two 150 h.p. Hispano-Suiza

H.4 - Two 90 h.p. Curtiss, or two 100 h.p. Anzani

Span: F.1 and H.4 - 72 feet

Length:

F.1 - 39 feet 2 inches

H.4 - 35 feet

Weight Loaded:

H.4 - 4,983 pounds

Total Area: F.1 and H.4 - 842 square feet

Max. Speed:

F.1 - 85 m.p.h.

H.4 - 75 m.p.h.

Endurance: Not available

Armament: F.1 and H.4 - One or two Lewis guns, light bombs only

Porte/Felixstowe F.2 and F.2A (1917)

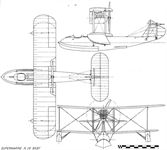

As a result of the shortcomings of the Curtiss H.4 regarding long-range patrol work, Porte requested Glenn Curtiss to develop a larger flying-boat with greater range and load-carrying capacity, and an order for fifty such machines was placed in 1915, the first being delivered in July 1916. This was the Curtiss H.8, or ‘Large America’, powered by two 160 h.p. Curtiss engines. These engines proved to be unsatisfactory, however, and Porte had them replaced by two 250 h.p. Rolls-Royce units, the modified machines being designated Curtiss H.12. They performed quite well, but suffered from weak, unseaworthy hulls, and poor fields of fire for the defensive armament. Encouraged by the excellent results obtained for the Porte 1 hull, Porte decided to redesign the hull of the H. 12, ably assisted by his Chief Technical Officer, Lieut, (later Major) J. D. Rennie. The new hull used the same construction method as the Porte 1 and measured 42 feet 2 inches from bow to stern, with two steps, and side fins 30 feet in length. Fitted with the mainplanes of an H.12, two 250 h.p. Rolls-Royce engines and a new tail unit, the machine, serialled No. 8650, was designated F.2 and proved vastly superior in performance to the standard H.12, taking off smoothly and easily at a loaded weight of 10,500 pounds. After some structural modifications were made in the light of operational experience, quantity production was authorised, the production version designated F.2A. Fitted with the more powerful Marks of the Rolls-Royce Eagle, the F.2A had a range and endurance more than adequate for defensive and offensive patrols, and a formidable armament consisting of two 230-pound bombs and up to five Lewis guns with excellent fields of fire. The fuel system, however, gave a lot of trouble, mainly due to its layout. A 409-gallon tank situated in the hull fed a 26-gallon gravity tank in the upper mainplane centre section by means of wind-driven pumps, the fuel then passing to the engines by gravity. Blocked pipes and filters, and fuel pump failures caused many forced alightings, and a contemporary report stated that ‘our real enemy is our own petrol pipes’. This situation led to the adoption of bizarre colour schemes for F.2A hulls, using red, white, and yellow paint, so that stricken machines could be readily spotted and towed home. Production F.2As began to appear late in 1917, a sub-contract having been arranged with Short Brothers, of Eastchurch. These machines had a two-stepped hull, only slightly differing from that of the F.2. In the bows, the front gunner’s cockpit was equipped with twin Lewis guns on a Scarff ring-mounting, while the rear gunner was positioned aft of the lower mainplane with similar armament. Some aircraft also had single guns, fired from side-hatches in the hull. The first and second pilots, the latter acting as front gunner, were partially enclosed in a glazed cabin, although this was often removed to improve visibility and performance. Engine control was simplified by the employment of an engineer-gunner, positioned in an internal compartment and controlling engine starting and inflight temperatures. The fourth crew member was usually a rigger-gunner. This crew arrangement tended to make the boats less dependent on their bases for servicing and minor repairs, and was standard in all large R.N.A.S. flying-boats. The F.2A power units were two Rolls-Royce Eagle VI Ils, developing 346 h.p. at 1,800 r.p.m. and driving four-bladed tractor propellers, the revolutions of which were reduced to 1,080 r.p.m. by epicyclic gearing. Some of the early F.2As had fabric decking to their hulls, but the ravages of wind and weather soon indicated its weakness and later machines had plywood decking. Production was greatly facilitated by the fact that the relatively simple hull construction did not call for highly skilled labour, and also by the availability of H.12 components, but demands for Rolls-Royce engines so far exceeded the supply that the total number of F.2As on charge never reached official requirements. To offset this situation several H.12s were rebuilt with Porte hulls and F.2A tail units, these modifications rendering them indistinguishable from F.2As.

Together, the F.2As and H.12s rendered great service in the critical year of 1917, when U-boat warfare was at its height. The first success came on 20 May, when the H.12 commanded by Fit. Sub-Lieut. Morrish destroyed submarine UC-36, and by the end of the year the flying-boats had sighted sixty-seven U-boats and had attacked forty-four. The Zeppelins, too, came in for attention, and on 14 May, 1917, L.22 fell to the guns of H.12 No. 8666, captained by Fit. Lieut. Galpin. In June, L.43 was destroyed by H.12 No. 8677, and a year later an F.2A from Killingholme, flown by Captains Pattinson and Munday, was responsible for the destruction of L.62 over the Heligoland minefields. All this activity took place in the face of strong German opposition, mainly from seaplanes under the command of the German Naval ‘ace’, Christiensen, and many combats took place, culminating in a pitched battle on 4 June, 1918. On that day, Capt. Robert Leckie led a force of four F.2As and a single H.12 on an offensive patrol towards the Haaks Light Vessel, three hours flying time from Felixstowe. After two-and-a-half hours, one of the F.2As was forced down by a broken petrol feed pipe, and its pilot, Capt. R. F. L. Dickey, had no choice but to taxi to the Dutch coast. On the way, five German seaplanes made a half-hearted attack upon the crippled machine, losing one of their number to its gunners, the rest breaking off the action, hotly pursued by the H.12, while the three F.2As formed a protective circle over Dickey’s machine. Soon afterwards, a formation of ten more German seaplanes arrived and Leckie charged them head-on, losing his wireless aerial on the upper wing of the enemy leader and splitting up the formation. The battle which followed lasted forty minutes, during which time the flying-boats shot down two Germans and probably destroyed four more without loss to themselves, although one F.2A went down on the Zuider Zee with a broken petrol pipe during the action. This was repaired by the engineer, however, and the machine rejoined the others. On the way back to Great Yarmouth, Capt. J. Hodson’s aircraft had an engine failure, flight being maintained on half-power while repairs were effected. Two flying-boats had been lost, for the H.12 force-landed in Dutch waters also, and both crews were interned. In 1918 the range of the flying-boats was extended by the use of special lighters designed by Porte, the machines being floated on to the fighters and towed by destroyers to a launching point off the German coast, returning after reconnaissance flights to be towed home. This system had its limitations, but several successful operations were completed. Another method of extending range was the carriage of extra fuel in cans, and by this means flights of over nine hours’ duration were made, pilot fatigue being minimised by the fitting of dual control to the F.2A.

Two illustrations are on record to prove the strength of the F.2A; in one, a machine was actually looped over Killingholme by an aggrieved American trainee, and in the other a single-engined approach aimed at Leeds Reservoir was misjudged and terminated in a ploughed field, the only damage incurred being strained bracing wires.

SPECIFICATION

Power Plant:

F.2 and H.12 - Two 250 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle I

F.2A - Two 345 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII

Span: F.2, F.2A, and H.12 - 95 feet 7 1/2 inches

Length:

H.12 - 46 feet 6 inches

F.2 and F.2A - 46 feet 3 inches

Weight Loaded:

H.12 - 10,650 pounds

F.2 - 10,000 pounds

F.2A - 10,978 pounds

Total Area: F.2, F.2A, and H.12 -1,133 square feet

Max. Speed:

H.12 - 85 m.p.h.

F.2 - 95 m.p.h.

F.2A - 95-5 m.p.h.

Endurance: F.2, F.2A, and H.12 - 6 hours (normal)

Armament:

H.12 - Up to four Lewis guns on flexible mountings in bow and pilot’s cockpit. Four 100-pound or two 230-pound bombs

F.2 - Experimental gun installations for F.2A, max. bomb load of 460 pounds

F.2A - Four to seven Lewis guns on flexible mountings, two 230-pound bombs

Porte/Felixstowe F.2C (1917)

An experimental version of the F.2A, the F.2C did not pass beyond the prototype stage. It was fitted with a modified hull of lighter construction, having alterations to the front gun position, an open cockpit for the pilots, and no hull side hatches. The F.2C power units were initially 275 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle Ils, later replaced by the 322 h.p. Eagle VI. Official trials took place on 23 June, 1917, the machine showing a slightly better performance than the F.2A, but the margin was too small to justify interference with the F.2A production programme. However, the F.2C, serialled N65, saw active service with the R.N.A.S. at Felixstowe and on 24 July, 1917, flown by Wg. Cmdr. Porte, released two of the five 230-pound bombs which sank submarine UC-1. Some time later the machine was fitted with experimental pneumatic bomb-release gear which chose to be temperamental at the worst possible moment resulting in a surfaced U-boat escaping unscathed.

SPECIFICATION

Power Plant: Two 275 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle II or 322 h.p. Eagle VI

Span: 95 feet

Length: 46 feet

Weight Loaded: 10,240 pounds

Total Area: 1,136 square feet

Max. Speed: 98-5 m.p.h.

Endurance: 6-5 hours

Armament: Two Lewis guns, two 230-pound bombs

Porte/Felixstowe F.5 (1918)

Intended as an improvement upon the F.3, the F.5 appeared in early 1918. Externally similar to its predecessors, and employing the standard Porte hull construction, it embodied a number of refinements developed as a result of experience with the previous designs. The top decking of the hull was deeper than before, and the pilots were seated in an open cockpit, while the gun positions were of the same arrangement as the F.3. Four 230-pound bombs could be carried in the standard underwing racks. The wing structure was entirely new, with a span greater than the F.3 and a modified section, also constant-chord ailerons. A broad-chord tailplane projected ahead of the fin leading edge, the rudder, and the ailerons, being horn-balanced. Serialled N90, the prototype was powered by two 350 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VIIIs driving four-bladed tractor propellers, and on its official trials it displayed a much better performance than the F.3, even under conditions of overload. Unfortunately, the prototype F.5 fell foul of economics, for the large F.3 construction programme did not readily permit the introduction of a new type. A compromise was reached with the extensive modification of the F.5 to incorporate as many F.3 components as possible, resulting in a machine not wholly satisfactory, but nevertheless put into production. The hull of the modified machine was similar to that of N90, but its overall covering of plywood, with only the top decking of fabric, added considerably to the weight, which, in the completed aircraft, exceeded that of N90 by more than 1,000 pounds. The wing structure was that of the F.3, modified to take constant-chord ailerons, and the tail unit was identical to that of the prototype, although later F.5s had horn-balanced elevators. The slightly greater wing span of the F.5 as compared to the F.3 was accounted for by the ailerons, which extended beyond the wing-tips. Official test figures show that the performance of the production F.5 was inferior to that of the F.3, and in some instances this was further impaired by the fitting of lower powered engines, the 325 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VII.

Too late for operational service, the type was adopted as the R.A.F.’s standard post-war flying-boat and remained in service until replacement by Southamptons in 1925. In the summer of 1919, an early production F.5, N4044, toured Scandinavia to demonstrate the capabilities of flying-boats, covering 2,450 miles in 27 days and returning to Felixstowe fully serviceable. Another equally successful tour took place in 1923, when two F.5s commanded by Air Commodore Bigsworth completed a cruise to Gibraltar, Malta, Bizerta, and Oran without mishap.

Before the Armistice, F.5 production had started in Canada at the factory of Canadian Aeroplanes Ltd to the order of the United States Air Board. These machines were fitted with the Liberty 12 engine of 400 h.p. and equipped the U.S. Naval Air Service in 1918. A series of structurally modified F.5s was also built by the U.S. Naval Aircraft Factory at Philadelphia; these too had the Liberty engine and were designated F.5L. The F.5L could carry 1,000 pounds of bombs and up to eleven machine-guns, and some mounted a Davis quick-firing gun in the bows. These machines gave years of service to the U.S. Navy,both in the Atlantic and the Pacific Fleets, later versions having a greatly enlarged fin and a horn-balanced rudder. Also in America, two converted F.5Ls formed the equipment of one of the first airlines to operate flying-boats, Aeromarine West Indies Airways, Inc., in 1920. In 1921, the Japanese company, Aichi of Nagoya, obtained a licence to build F.5s and produced fifteen machines which served with the Imperial Japanese Naval Air Service and made several notable long-distance flights, recording durations of over nine hours in some cases. In this country, the F.5 was used for a number of experiments, among which were the trial of auxiliary aerofoil aileron balances on N4838, and the fitting of a special hollow-bottom Saunders hull to N178. In 1924, Short Brothers produced an F.5, N177, with an all-metal hull, the first military flying-boat in the world to be so fitted. The F.5 formed the equipment of eight R.A.F. squadrons, a ninth, No. 230, being renumbered No. 480 Flight at the end of 1922 and forming the training establishment for flying-boats at Calshot.

SPECIFICATION

Power Plant:

Prototype - Two 350 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII

Production - Two 350 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII or two 325 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VII

Canadian F.5s and American F.5Ls - Two 400 h.p. Liberty 12

Span: 103 feet 8 inches

F.5L-103 feet 9 inches

Length : 49 feet 3 inches

Prototype - 49 feet 6 inches

Weight Loaded: 12,682 pounds

Prototype - 12,268 pounds

F.5L - 13,000 pounds

Total Area: 1,409 square feet

F.5L - 1,397 square feet

Max. Speed:

Prototype - 102 m.p.h.

Production - 88 m.p.h.

F.5L - 87 m.p.h.

Endurance: 7 hours (normal)

F.5L - 7-9 hours

Armament:

Four Lewis guns, four 230-pound bombs

Canadian machines could have up to eight Lewis guns

F.5L - maximum armament of one Davis gun, eleven Lewis guns. Normal armament was one Davis gun, four Lewis guns, and four 230-pound bombs or two 500-pound bombs

As a result of the shortcomings of the Curtiss H.4 regarding long-range patrol work, Porte requested Glenn Curtiss to develop a larger flying-boat with greater range and load-carrying capacity, and an order for fifty such machines was placed in 1915, the first being delivered in July 1916. This was the Curtiss H.8, or ‘Large America’, powered by two 160 h.p. Curtiss engines. These engines proved to be unsatisfactory, however, and Porte had them replaced by two 250 h.p. Rolls-Royce units, the modified machines being designated Curtiss H.12. They performed quite well, but suffered from weak, unseaworthy hulls, and poor fields of fire for the defensive armament. Encouraged by the excellent results obtained for the Porte 1 hull, Porte decided to redesign the hull of the H. 12, ably assisted by his Chief Technical Officer, Lieut, (later Major) J. D. Rennie. The new hull used the same construction method as the Porte 1 and measured 42 feet 2 inches from bow to stern, with two steps, and side fins 30 feet in length. Fitted with the mainplanes of an H.12, two 250 h.p. Rolls-Royce engines and a new tail unit, the machine, serialled No. 8650, was designated F.2 and proved vastly superior in performance to the standard H.12, taking off smoothly and easily at a loaded weight of 10,500 pounds. After some structural modifications were made in the light of operational experience, quantity production was authorised, the production version designated F.2A. Fitted with the more powerful Marks of the Rolls-Royce Eagle, the F.2A had a range and endurance more than adequate for defensive and offensive patrols, and a formidable armament consisting of two 230-pound bombs and up to five Lewis guns with excellent fields of fire. The fuel system, however, gave a lot of trouble, mainly due to its layout. A 409-gallon tank situated in the hull fed a 26-gallon gravity tank in the upper mainplane centre section by means of wind-driven pumps, the fuel then passing to the engines by gravity. Blocked pipes and filters, and fuel pump failures caused many forced alightings, and a contemporary report stated that ‘our real enemy is our own petrol pipes’. This situation led to the adoption of bizarre colour schemes for F.2A hulls, using red, white, and yellow paint, so that stricken machines could be readily spotted and towed home. Production F.2As began to appear late in 1917, a sub-contract having been arranged with Short Brothers, of Eastchurch. These machines had a two-stepped hull, only slightly differing from that of the F.2. In the bows, the front gunner’s cockpit was equipped with twin Lewis guns on a Scarff ring-mounting, while the rear gunner was positioned aft of the lower mainplane with similar armament. Some aircraft also had single guns, fired from side-hatches in the hull. The first and second pilots, the latter acting as front gunner, were partially enclosed in a glazed cabin, although this was often removed to improve visibility and performance. Engine control was simplified by the employment of an engineer-gunner, positioned in an internal compartment and controlling engine starting and inflight temperatures. The fourth crew member was usually a rigger-gunner. This crew arrangement tended to make the boats less dependent on their bases for servicing and minor repairs, and was standard in all large R.N.A.S. flying-boats. The F.2A power units were two Rolls-Royce Eagle VI Ils, developing 346 h.p. at 1,800 r.p.m. and driving four-bladed tractor propellers, the revolutions of which were reduced to 1,080 r.p.m. by epicyclic gearing. Some of the early F.2As had fabric decking to their hulls, but the ravages of wind and weather soon indicated its weakness and later machines had plywood decking. Production was greatly facilitated by the fact that the relatively simple hull construction did not call for highly skilled labour, and also by the availability of H.12 components, but demands for Rolls-Royce engines so far exceeded the supply that the total number of F.2As on charge never reached official requirements. To offset this situation several H.12s were rebuilt with Porte hulls and F.2A tail units, these modifications rendering them indistinguishable from F.2As.

Together, the F.2As and H.12s rendered great service in the critical year of 1917, when U-boat warfare was at its height. The first success came on 20 May, when the H.12 commanded by Fit. Sub-Lieut. Morrish destroyed submarine UC-36, and by the end of the year the flying-boats had sighted sixty-seven U-boats and had attacked forty-four. The Zeppelins, too, came in for attention, and on 14 May, 1917, L.22 fell to the guns of H.12 No. 8666, captained by Fit. Lieut. Galpin. In June, L.43 was destroyed by H.12 No. 8677, and a year later an F.2A from Killingholme, flown by Captains Pattinson and Munday, was responsible for the destruction of L.62 over the Heligoland minefields. All this activity took place in the face of strong German opposition, mainly from seaplanes under the command of the German Naval ‘ace’, Christiensen, and many combats took place, culminating in a pitched battle on 4 June, 1918. On that day, Capt. Robert Leckie led a force of four F.2As and a single H.12 on an offensive patrol towards the Haaks Light Vessel, three hours flying time from Felixstowe. After two-and-a-half hours, one of the F.2As was forced down by a broken petrol feed pipe, and its pilot, Capt. R. F. L. Dickey, had no choice but to taxi to the Dutch coast. On the way, five German seaplanes made a half-hearted attack upon the crippled machine, losing one of their number to its gunners, the rest breaking off the action, hotly pursued by the H.12, while the three F.2As formed a protective circle over Dickey’s machine. Soon afterwards, a formation of ten more German seaplanes arrived and Leckie charged them head-on, losing his wireless aerial on the upper wing of the enemy leader and splitting up the formation. The battle which followed lasted forty minutes, during which time the flying-boats shot down two Germans and probably destroyed four more without loss to themselves, although one F.2A went down on the Zuider Zee with a broken petrol pipe during the action. This was repaired by the engineer, however, and the machine rejoined the others. On the way back to Great Yarmouth, Capt. J. Hodson’s aircraft had an engine failure, flight being maintained on half-power while repairs were effected. Two flying-boats had been lost, for the H.12 force-landed in Dutch waters also, and both crews were interned. In 1918 the range of the flying-boats was extended by the use of special lighters designed by Porte, the machines being floated on to the fighters and towed by destroyers to a launching point off the German coast, returning after reconnaissance flights to be towed home. This system had its limitations, but several successful operations were completed. Another method of extending range was the carriage of extra fuel in cans, and by this means flights of over nine hours’ duration were made, pilot fatigue being minimised by the fitting of dual control to the F.2A.

Two illustrations are on record to prove the strength of the F.2A; in one, a machine was actually looped over Killingholme by an aggrieved American trainee, and in the other a single-engined approach aimed at Leeds Reservoir was misjudged and terminated in a ploughed field, the only damage incurred being strained bracing wires.

SPECIFICATION

Power Plant:

F.2 and H.12 - Two 250 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle I

F.2A - Two 345 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII

Span: F.2, F.2A, and H.12 - 95 feet 7 1/2 inches

Length:

H.12 - 46 feet 6 inches

F.2 and F.2A - 46 feet 3 inches

Weight Loaded:

H.12 - 10,650 pounds

F.2 - 10,000 pounds

F.2A - 10,978 pounds

Total Area: F.2, F.2A, and H.12 -1,133 square feet

Max. Speed:

H.12 - 85 m.p.h.

F.2 - 95 m.p.h.

F.2A - 95-5 m.p.h.

Endurance: F.2, F.2A, and H.12 - 6 hours (normal)

Armament:

H.12 - Up to four Lewis guns on flexible mountings in bow and pilot’s cockpit. Four 100-pound or two 230-pound bombs

F.2 - Experimental gun installations for F.2A, max. bomb load of 460 pounds

F.2A - Four to seven Lewis guns on flexible mountings, two 230-pound bombs

Porte/Felixstowe F.2C (1917)

An experimental version of the F.2A, the F.2C did not pass beyond the prototype stage. It was fitted with a modified hull of lighter construction, having alterations to the front gun position, an open cockpit for the pilots, and no hull side hatches. The F.2C power units were initially 275 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle Ils, later replaced by the 322 h.p. Eagle VI. Official trials took place on 23 June, 1917, the machine showing a slightly better performance than the F.2A, but the margin was too small to justify interference with the F.2A production programme. However, the F.2C, serialled N65, saw active service with the R.N.A.S. at Felixstowe and on 24 July, 1917, flown by Wg. Cmdr. Porte, released two of the five 230-pound bombs which sank submarine UC-1. Some time later the machine was fitted with experimental pneumatic bomb-release gear which chose to be temperamental at the worst possible moment resulting in a surfaced U-boat escaping unscathed.

SPECIFICATION

Power Plant: Two 275 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle II or 322 h.p. Eagle VI

Span: 95 feet

Length: 46 feet

Weight Loaded: 10,240 pounds

Total Area: 1,136 square feet

Max. Speed: 98-5 m.p.h.

Endurance: 6-5 hours

Armament: Two Lewis guns, two 230-pound bombs

Porte/Felixstowe F.5 (1918)

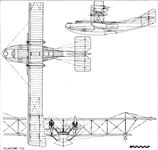

Intended as an improvement upon the F.3, the F.5 appeared in early 1918. Externally similar to its predecessors, and employing the standard Porte hull construction, it embodied a number of refinements developed as a result of experience with the previous designs. The top decking of the hull was deeper than before, and the pilots were seated in an open cockpit, while the gun positions were of the same arrangement as the F.3. Four 230-pound bombs could be carried in the standard underwing racks. The wing structure was entirely new, with a span greater than the F.3 and a modified section, also constant-chord ailerons. A broad-chord tailplane projected ahead of the fin leading edge, the rudder, and the ailerons, being horn-balanced. Serialled N90, the prototype was powered by two 350 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VIIIs driving four-bladed tractor propellers, and on its official trials it displayed a much better performance than the F.3, even under conditions of overload. Unfortunately, the prototype F.5 fell foul of economics, for the large F.3 construction programme did not readily permit the introduction of a new type. A compromise was reached with the extensive modification of the F.5 to incorporate as many F.3 components as possible, resulting in a machine not wholly satisfactory, but nevertheless put into production. The hull of the modified machine was similar to that of N90, but its overall covering of plywood, with only the top decking of fabric, added considerably to the weight, which, in the completed aircraft, exceeded that of N90 by more than 1,000 pounds. The wing structure was that of the F.3, modified to take constant-chord ailerons, and the tail unit was identical to that of the prototype, although later F.5s had horn-balanced elevators. The slightly greater wing span of the F.5 as compared to the F.3 was accounted for by the ailerons, which extended beyond the wing-tips. Official test figures show that the performance of the production F.5 was inferior to that of the F.3, and in some instances this was further impaired by the fitting of lower powered engines, the 325 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VII.

Too late for operational service, the type was adopted as the R.A.F.’s standard post-war flying-boat and remained in service until replacement by Southamptons in 1925. In the summer of 1919, an early production F.5, N4044, toured Scandinavia to demonstrate the capabilities of flying-boats, covering 2,450 miles in 27 days and returning to Felixstowe fully serviceable. Another equally successful tour took place in 1923, when two F.5s commanded by Air Commodore Bigsworth completed a cruise to Gibraltar, Malta, Bizerta, and Oran without mishap.

Before the Armistice, F.5 production had started in Canada at the factory of Canadian Aeroplanes Ltd to the order of the United States Air Board. These machines were fitted with the Liberty 12 engine of 400 h.p. and equipped the U.S. Naval Air Service in 1918. A series of structurally modified F.5s was also built by the U.S. Naval Aircraft Factory at Philadelphia; these too had the Liberty engine and were designated F.5L. The F.5L could carry 1,000 pounds of bombs and up to eleven machine-guns, and some mounted a Davis quick-firing gun in the bows. These machines gave years of service to the U.S. Navy,both in the Atlantic and the Pacific Fleets, later versions having a greatly enlarged fin and a horn-balanced rudder. Also in America, two converted F.5Ls formed the equipment of one of the first airlines to operate flying-boats, Aeromarine West Indies Airways, Inc., in 1920. In 1921, the Japanese company, Aichi of Nagoya, obtained a licence to build F.5s and produced fifteen machines which served with the Imperial Japanese Naval Air Service and made several notable long-distance flights, recording durations of over nine hours in some cases. In this country, the F.5 was used for a number of experiments, among which were the trial of auxiliary aerofoil aileron balances on N4838, and the fitting of a special hollow-bottom Saunders hull to N178. In 1924, Short Brothers produced an F.5, N177, with an all-metal hull, the first military flying-boat in the world to be so fitted. The F.5 formed the equipment of eight R.A.F. squadrons, a ninth, No. 230, being renumbered No. 480 Flight at the end of 1922 and forming the training establishment for flying-boats at Calshot.

SPECIFICATION

Power Plant:

Prototype - Two 350 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII

Production - Two 350 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII or two 325 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VII

Canadian F.5s and American F.5Ls - Two 400 h.p. Liberty 12

Span: 103 feet 8 inches

F.5L-103 feet 9 inches

Length : 49 feet 3 inches

Prototype - 49 feet 6 inches

Weight Loaded: 12,682 pounds

Prototype - 12,268 pounds

F.5L - 13,000 pounds

Total Area: 1,409 square feet

F.5L - 1,397 square feet

Max. Speed:

Prototype - 102 m.p.h.

Production - 88 m.p.h.

F.5L - 87 m.p.h.

Endurance: 7 hours (normal)

F.5L - 7-9 hours

Armament:

Four Lewis guns, four 230-pound bombs

Canadian machines could have up to eight Lewis guns

F.5L - maximum armament of one Davis gun, eleven Lewis guns. Normal armament was one Davis gun, four Lewis guns, and four 230-pound bombs or two 500-pound bombs

N4839, a production F.5, was visually similar to the prototype but the performance suffered due to official interference in the design. N4839 was from a batch of 50 boats ordered from Short Brothers Ltd. It made its first flight at Short's, Rochester, on 23 March 1920. Served with the Development Flight at Grain in 1922 and was still with the Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment in June 1923.

Porte/Felixstowe Fury (1918)

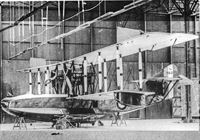

John Porte’s last Felixstowe production was a huge triplane flying-boat, the largest British machine of its day, powered by no fewer than five 334 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VII engines. The Fury was probably inspired by a large Curtiss triplane flying-boat which had been assembled and flown at Felixstowe in 1916, the Curtiss-Wanamaker, serialled No. 3073. This machine was the first delivered of an order for twenty, but even with its original four 250 h.p. Curtiss engines replaced by Rolls-Royce power units, official tests showed that the performance did not measure up to requirements and the order was cancelled. At the time, Porte had little opportunity and insufficient resources to deal with the redesign of the Curtiss-Wanamaker, but it is certain that as an advocate of the large flying-boat he did not forget it, and when the Fury appeared in 1918 several features of the Curtiss machine were embodied. Known to all at Felixstowe as the Porte Super Baby, the Fury was planned for an engine installation of three of the new 600 h.p. Rolls-Royce Condors but was completed before the Condor became available, so the engine mountings were modified to take five Rolls-Royce Eagles arranged as a central pusher flanked by two outboard pairs of pusher and tractor. The hull, basically employing a similar construction and profile to the other Felixstowe boats and 60 feet in length, was regarded as the best of all the Porte hulls. The top and central mainplanes were of equal span, the latter carrying the engines, while the lower mainplane was one bay shorter. The tail unit resembled that of the Curtiss-Wanamaker, with a biplane tailplane fitted with twin rudders mounted upon a central fin. The Fury design incorporated power-operated controls, using servo-motors, and it was almost certainly the first aircraft in the world to fly with these in operation although actually the Fury proved to be remarkably light on all controls and so the weighty servos were dispensed with. The machine’s designed loaded weight was 24,000 pounds, this being gradually increased during testing without adverse effect upon take-off or seaworthiness until it reached the figure of 33,000 pounds, at which enormous weight Porte himself coaxed the great machine into the air from Harwich Harbour. On another occasion, Major T. D. Hallam, d.s.C., flew the Fury with 24 passengers, fuel for seven hours, and 5,000 pounds of ballast. The tail unit was later modified to a more conventional assembly of biplane layout with triple rudders between the tailplanes, and the hull tested in model form in the Froude Tank at the National Physical Laboratory, some of the recommended modifications resulting from this testing being applied to the full-sized aircraft. Never used operationally, the Fury continued experimental flying after the Armistice, powered in its final form by five Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII engines of 365 h.p. each. A few months after Porte and Rennie were demobilised, the Fury stalled and crashed on take-off, possibly due to incorrect loading, the pilot and two crew members losing their lives.

In August 1919, Porte joined the Gosport Aviation Co. Ltd., as chief designer, to work with an old friend, Herman Volk, who had become manager of the company. A number of designs was produced but none was built due to the post-war slump in orders. In October 1919 John Porte died at Brighton. He was thirty-five years old.

SPECIFICATION

Power Plant: Five 334 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VII, or five 365 h.p. Rolls- Royce Eagle VIII

Span: 123 feet

Length: 63 feet 2 inches

Weight Loaded: 25,253 pounds (medium), 33,000 pounds (max. test)

Total Area: 3,108 square feet

Max. Speed: 97 m.p.h. at 2,000 feet

Endurance: 7 hours (medium). In excess of 12 hours with max. fuel load

Armament: Four Lewis guns and heavy bomb load

John Porte’s last Felixstowe production was a huge triplane flying-boat, the largest British machine of its day, powered by no fewer than five 334 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VII engines. The Fury was probably inspired by a large Curtiss triplane flying-boat which had been assembled and flown at Felixstowe in 1916, the Curtiss-Wanamaker, serialled No. 3073. This machine was the first delivered of an order for twenty, but even with its original four 250 h.p. Curtiss engines replaced by Rolls-Royce power units, official tests showed that the performance did not measure up to requirements and the order was cancelled. At the time, Porte had little opportunity and insufficient resources to deal with the redesign of the Curtiss-Wanamaker, but it is certain that as an advocate of the large flying-boat he did not forget it, and when the Fury appeared in 1918 several features of the Curtiss machine were embodied. Known to all at Felixstowe as the Porte Super Baby, the Fury was planned for an engine installation of three of the new 600 h.p. Rolls-Royce Condors but was completed before the Condor became available, so the engine mountings were modified to take five Rolls-Royce Eagles arranged as a central pusher flanked by two outboard pairs of pusher and tractor. The hull, basically employing a similar construction and profile to the other Felixstowe boats and 60 feet in length, was regarded as the best of all the Porte hulls. The top and central mainplanes were of equal span, the latter carrying the engines, while the lower mainplane was one bay shorter. The tail unit resembled that of the Curtiss-Wanamaker, with a biplane tailplane fitted with twin rudders mounted upon a central fin. The Fury design incorporated power-operated controls, using servo-motors, and it was almost certainly the first aircraft in the world to fly with these in operation although actually the Fury proved to be remarkably light on all controls and so the weighty servos were dispensed with. The machine’s designed loaded weight was 24,000 pounds, this being gradually increased during testing without adverse effect upon take-off or seaworthiness until it reached the figure of 33,000 pounds, at which enormous weight Porte himself coaxed the great machine into the air from Harwich Harbour. On another occasion, Major T. D. Hallam, d.s.C., flew the Fury with 24 passengers, fuel for seven hours, and 5,000 pounds of ballast. The tail unit was later modified to a more conventional assembly of biplane layout with triple rudders between the tailplanes, and the hull tested in model form in the Froude Tank at the National Physical Laboratory, some of the recommended modifications resulting from this testing being applied to the full-sized aircraft. Never used operationally, the Fury continued experimental flying after the Armistice, powered in its final form by five Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII engines of 365 h.p. each. A few months after Porte and Rennie were demobilised, the Fury stalled and crashed on take-off, possibly due to incorrect loading, the pilot and two crew members losing their lives.

In August 1919, Porte joined the Gosport Aviation Co. Ltd., as chief designer, to work with an old friend, Herman Volk, who had become manager of the company. A number of designs was produced but none was built due to the post-war slump in orders. In October 1919 John Porte died at Brighton. He was thirty-five years old.

SPECIFICATION

Power Plant: Five 334 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VII, or five 365 h.p. Rolls- Royce Eagle VIII

Span: 123 feet

Length: 63 feet 2 inches

Weight Loaded: 25,253 pounds (medium), 33,000 pounds (max. test)

Total Area: 3,108 square feet

Max. Speed: 97 m.p.h. at 2,000 feet

Endurance: 7 hours (medium). In excess of 12 hours with max. fuel load

Armament: Four Lewis guns and heavy bomb load

Fury on initial trials, with original tail surfaces. Its hull was the best developed by Porte and threw up less water than previous hulls.

Wyvenhoe Flier (1909)

Historically important as the first serious attempt to produce a flying-boat in Britain, work commenced upon the Wyvenhoe Flier in October 1908, supervised by its designer, Mr J. E. Humphreys, construction being carried out in a small hangar between Forrestt’s boatyard at Wyvenhoe and the river bank opposite Rowhedge, in Essex. Humphreys, a dental surgeon, was by no means an amateur regarding aerodynamics, having experimented with bird flight and structure since 1902, and had actually flown two of his own gliders from the cliffs at Fowey, Cornwall.

The Flier was built by local skilled marine craftsmen, with the co-operation of Mr (later Sir James) Bird, managing director of Forrestts.

In many ways advanced for its time, the machine was a biplane, with the wings mounted above the hull and the engine and propellers in mid-gap, thus anticipating a design layout for flying-boats that endured for a quarter of a century. For the first time in aviation history, extensive metal skinning was employed, both mainplanes being covered with light-gauge aluminium sheet. The coracle-type hull had a double skin of thin cedar planking, with varnished silk interposed, with a small scuttle in the bows serving as protection for the pilot. No water rudder was fitted. The lower wing was secured to the hull gunwales, its multiple spars as extensions of the hull ribs and curved downwards to the tips, which formed full-chord ‘air boxes’ for lateral stability on the water. A wheeled undercarriage consisting of two pairs of cycle-type wheels mounted in tandem on bamboo poles, and arranged to make use of the natural spring thereof, was designed to fit up under the lower wing, but was never used in practice. The upper wing, supported upon tubular steel interplane struts and wire braced, had large drooping tip extensions of triangular shape built up of long narrow sections covered with strips of rubber-impregnated cotton silk. These extensions were similar in function and appearance to the wing-tip feathers of a bird. Strut-mounted on the lower wing trailing edge was a bird-like tailplane/rudder, universally jointed, and of the same ‘feather’ construction as the wing tips. The control surfaces were completed by a triangular elevator, carried forward of the hull and wing structure on outriggers. Elevator and tailplane were both operated by a single control.

A 35 h.p. J.A.P. Vee-eight air-cooled engine was transversely mounted on steel tubular bearers in mid-gap behind the pilot, driving two 8-foot diameter metal pusher propellers through shafts, bevel gears, and centrifugal clutches. The propeller blades were curved rearwards towards the tips, with the idea of concentrating the slipstream into a ‘jet wake‘ to assist thrust.

The first launching was made on 3 April, 1909, in rather marginal conditions of wind and tide. Inevitably, a gust canted the machine, and it sank. Humphreys, aboard at the time, extricated himself from the numerous bracing wires with some difficulty. The Flier was salvaged at midnight, and returned to its shed. Repairs having been completed, the second launching took place on 15 April. Again bad fortune attended, for one of the propeller drive gears sheared. At a third launching on the 18th, everything appeared to be in order, and the machine was towed down river by steam tug to a point between the Alresford and Fingringhoe Banks, cast off, and the engine started. It was immediately apparent that the wing-tip air boxes created impossible water drag, and that with the engine stopped, directional control was nil. The machine was towed back for alterations to be made, these consisting of canoeshaped wing-tip floats with controllable water rudders at the stern.

In the evening of 14 May, 1909, the Flier was towed to the swing bridge at Alresford Creek, and started up. This time, directional control proved excellent, the Flier skimming the water beautifully at a speed of 10 to 12 knots, but resisting all Humphreys’ efforts to ‘unstick’.

Financial considerations precluded further development, and the Flier was abandoned. Its engine finally did take to the air, being sold to Mr E. T. Willows, who used it to power his little dirigible airship on her memorable flight from Cardiff to London.

SPECIFICATION

Power Plant: One 35 h.p. J.A.P. Vee-eight air-cooled engine, with Bosch magneto

Span:

Main metal-clad wing section - 21 feet

Wing-tip extensions - 10 feet 6 inches each

O.A. Span - 42 feet

Length, O.A.: 26 feet (Hull - 17 feet)

Height: 12 feet

Weight Loaded: 1,750 pounds

Total Area: 1,100 square feet

Historically important as the first serious attempt to produce a flying-boat in Britain, work commenced upon the Wyvenhoe Flier in October 1908, supervised by its designer, Mr J. E. Humphreys, construction being carried out in a small hangar between Forrestt’s boatyard at Wyvenhoe and the river bank opposite Rowhedge, in Essex. Humphreys, a dental surgeon, was by no means an amateur regarding aerodynamics, having experimented with bird flight and structure since 1902, and had actually flown two of his own gliders from the cliffs at Fowey, Cornwall.

The Flier was built by local skilled marine craftsmen, with the co-operation of Mr (later Sir James) Bird, managing director of Forrestts.

In many ways advanced for its time, the machine was a biplane, with the wings mounted above the hull and the engine and propellers in mid-gap, thus anticipating a design layout for flying-boats that endured for a quarter of a century. For the first time in aviation history, extensive metal skinning was employed, both mainplanes being covered with light-gauge aluminium sheet. The coracle-type hull had a double skin of thin cedar planking, with varnished silk interposed, with a small scuttle in the bows serving as protection for the pilot. No water rudder was fitted. The lower wing was secured to the hull gunwales, its multiple spars as extensions of the hull ribs and curved downwards to the tips, which formed full-chord ‘air boxes’ for lateral stability on the water. A wheeled undercarriage consisting of two pairs of cycle-type wheels mounted in tandem on bamboo poles, and arranged to make use of the natural spring thereof, was designed to fit up under the lower wing, but was never used in practice. The upper wing, supported upon tubular steel interplane struts and wire braced, had large drooping tip extensions of triangular shape built up of long narrow sections covered with strips of rubber-impregnated cotton silk. These extensions were similar in function and appearance to the wing-tip feathers of a bird. Strut-mounted on the lower wing trailing edge was a bird-like tailplane/rudder, universally jointed, and of the same ‘feather’ construction as the wing tips. The control surfaces were completed by a triangular elevator, carried forward of the hull and wing structure on outriggers. Elevator and tailplane were both operated by a single control.

A 35 h.p. J.A.P. Vee-eight air-cooled engine was transversely mounted on steel tubular bearers in mid-gap behind the pilot, driving two 8-foot diameter metal pusher propellers through shafts, bevel gears, and centrifugal clutches. The propeller blades were curved rearwards towards the tips, with the idea of concentrating the slipstream into a ‘jet wake‘ to assist thrust.

The first launching was made on 3 April, 1909, in rather marginal conditions of wind and tide. Inevitably, a gust canted the machine, and it sank. Humphreys, aboard at the time, extricated himself from the numerous bracing wires with some difficulty. The Flier was salvaged at midnight, and returned to its shed. Repairs having been completed, the second launching took place on 15 April. Again bad fortune attended, for one of the propeller drive gears sheared. At a third launching on the 18th, everything appeared to be in order, and the machine was towed down river by steam tug to a point between the Alresford and Fingringhoe Banks, cast off, and the engine started. It was immediately apparent that the wing-tip air boxes created impossible water drag, and that with the engine stopped, directional control was nil. The machine was towed back for alterations to be made, these consisting of canoeshaped wing-tip floats with controllable water rudders at the stern.

In the evening of 14 May, 1909, the Flier was towed to the swing bridge at Alresford Creek, and started up. This time, directional control proved excellent, the Flier skimming the water beautifully at a speed of 10 to 12 knots, but resisting all Humphreys’ efforts to ‘unstick’.

Financial considerations precluded further development, and the Flier was abandoned. Its engine finally did take to the air, being sold to Mr E. T. Willows, who used it to power his little dirigible airship on her memorable flight from Cardiff to London.

SPECIFICATION

Power Plant: One 35 h.p. J.A.P. Vee-eight air-cooled engine, with Bosch magneto

Span:

Main metal-clad wing section - 21 feet

Wing-tip extensions - 10 feet 6 inches each

O.A. Span - 42 feet

Length, O.A.: 26 feet (Hull - 17 feet)

Height: 12 feet

Weight Loaded: 1,750 pounds

Total Area: 1,100 square feet

Norman Thompson N.T.4 and N.T.4A (1915)

On 4 October, 1915, the White and Thompson Company changed its name to the Norman Thompson Flight Company, Ltd, with F. P. H. Beadle as chief designer. The first machine to appear under the new name was the N.T.4. A development of the twin-engined Round Britain Race entrant of 1914, the N.T.4 was ordered for R.N.A.S. use, becoming known as the ‘America’ flying-boat, and later, with the introduction of the Curtiss H.12, as the ‘Small America’ although there was little resemblance between the Norman Thompson and Curtiss machines. It should be noted that at this time there was a confusing tendency to class all flying-boats as ‘Americas’, regardless of type or manufacture.

A biplane, with twin 150 h.p. Hispano-Suiza pusher engines driving two- bladed propellers, the N.T.4 had two side-by-side seats in an enclosed cabin. The hulls were made by S. E. Saunders at Cowes. The first production machine of a batch of six, No. 8338, was experimentally fitted with a two-pounder Davis gun mounted horizontally above the cabin roof. This gun was subsequently removed, not having been used operationally. Commencing with the second production batch, the N.T.4s had modified cabin windows to give better vision, and were fitted with 200 h.p. Hispano-Suiza engines. With these modifications the machines were designated N.T.4A, the first one, No. 9061, being stationed at Calshot. A total of over fifty machines of both versions served with the R.N.A.S. at seven coastal stations, where they were employed for patrols, and later for training duties.

SPECIFICATION

Power Plant:

N.T.4 - Two 150 h.p. Hispano-Suiza engines

N.T.4A - Two 200 h.p. Hispano-Suiza engines

Span: 78 feet 7 inches

Length: 41 feet 6 inches

Loaded: N.T.4A-6,469 pounds

Total Area: 936 square feet

Max. Speed: N.T.4A-95 m.p.h.

Endurance: 4 hours

Armament: Light bombs, .303-inch Lewis gun in cabin roof

Norman Thompson N.2C (1918)