В.Обухович, А.Никифоров Самолеты Первой Мировой войны

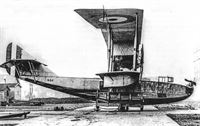

В 1913 г. американская компания "Кертисс" основала в Великобритании дочернюю фирму "Уайт энд Томпсон", которая занималась продвижением летающих лодок на английский рынок. Летчиком-испытателем фирмы стал англичанин Джон Порте, тесно сотрудничавший с Кертиссом в подготовке беспосадочного перелета через Атлантику на его летающей лодке, названной "Америка". Начавшаяся война помешала осуществлению этого проекта. Порте поступил на службу в морскую авиацию и был направлен в Америку для закупки летающих лодок Кертисс Н-4. После возвращения в 1915 г. в Англию он был назначен командиром авиационной базы ВМС Великобритании в Феликстоу. Большой опыт морского летчика позволил Порте взяться за разработку летающей лодки собственной конструкции, названной Феликстоу F.1. Впрочем, новым был лишь однореданный корпус лодки. Крыло и оперение Порте взял от гидросамолета Кертисс Н-4. Феликстоу F.1 был оснащен двумя двигателями Испано-Сюиза.

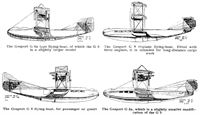

Документация на F.1 была передана компании "Кертисс", где проект был усовершенствован и запущен в серийное производство с двигателями Кертисс (160 л. с.) под обозначением Н-8 "Большая Америка". В 1916 г. 50 таких летающих лодок были закуплены Великобританией. Мощность двигателей была недостаточной, и Порте решил установить на Н-8 новые 12-цилиндровые V-образные двигатели жидкостного охлаждения Роллс-Ройс "Игл I" (250 л. с). Этот вариант получил наименование H-12. Однако лодка плохо показала себя в условиях Северного моря, и Порте спроектировал новый двухреданный корпус, а также модифицировал хвостовое оперение. Крылья и двигатели остались прежними, как у H-12. Летные характеристики лодки значительно выросли. Серийно выпускался вариант F.2A с двигателями Роллс-Ройс "Игл VIII" (355 л. с). Модификация Феликстоу F.2C имела корпус облегченной конструкции и двигатели Роллс-Ройс "Игл II" (275 л. с), которые впоследствии были заменены на Роллс-Ройс "Игл VI" (322 л. с). Эта летающая лодка имела отличные летные данные, но в серию она запущена не была.

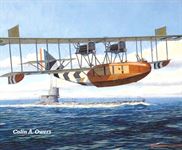

Самолеты Феликстоу F.2А применялись для дальней разведки, противолодочного патрулирования и в качестве многоместного истребителя охраны побережья. 4 июля 1918 г. капитан Паттисон, пилотирующий F.2A, сумел сбить над Гельголандом германский морской дирижабль L 62.

Увеличенный вариант F.2 с двумя двигателями Санбим "Коссак" (330 л. с.) или Роллс-Ройс "Игл VIII" был облетан в феврале 1917 г. и получил обозначение Феликстоу F.3. Бомбовая нагрузка возросла вдвое. Конструкция летающей лодки получилась удачной, хотя скорость считалась недостаточной, поэтому самолет, в основном, применялся для противолодочного патрулирования. Самолеты F.3 производились также компаниями "Шорт" и "Феникс". До конца войны было изготовлено около 100 машин, которые использовались на Средиземном море. Впоследствии многие летающие лодки Феликстоу F.3 были переоборудованы в следующую (послевоенную) модификацию F.5, которая по конструкции была аналогична F.2.

Двигатель 2 х Роллс-Ройс "Игл VIII" (355 л. с.)

Размеры:

размах х длина х высота 29,15 х 14,1 х 5,33 м

Площадь крыльев 105,26 м2

Вес:

пустого 3424 кг

взлетный 4980 кг

Максимальная скорость 153 км/ч

Потолок 2900 м

Дальность 950 км

Продолжительность полета 6 ч

Вооружение:

стрелковое 4-7 х 7,7-мм пулеметов "Льюис"

бомбовое 2 х 104 кг

Экипаж 4 чел.

Показать полностью

G.Duval British Flying-Boats and Amphibians 1909-1952 (Putnam)

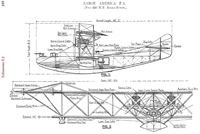

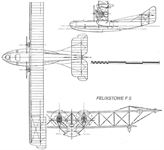

Porte/Felixstowe F.2 and F.2A (1917)

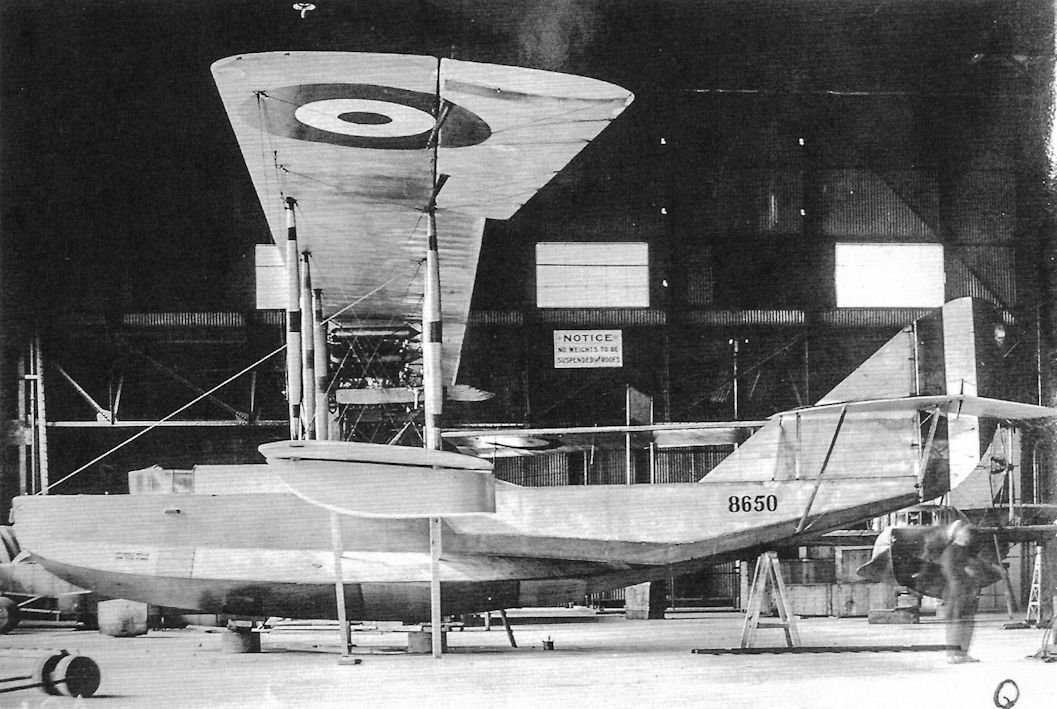

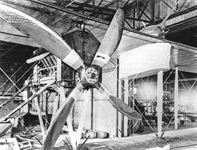

As a result of the shortcomings of the Curtiss H.4 regarding long-range patrol work, Porte requested Glenn Curtiss to develop a larger flying-boat with greater range and load-carrying capacity, and an order for fifty such machines was placed in 1915, the first being delivered in July 1916. This was the Curtiss H.8, or ‘Large America’, powered by two 160 h.p. Curtiss engines. These engines proved to be unsatisfactory, however, and Porte had them replaced by two 250 h.p. Rolls-Royce units, the modified machines being designated Curtiss H.12. They performed quite well, but suffered from weak, unseaworthy hulls, and poor fields of fire for the defensive armament. Encouraged by the excellent results obtained for the Porte 1 hull, Porte decided to redesign the hull of the H. 12, ably assisted by his Chief Technical Officer, Lieut, (later Major) J. D. Rennie. The new hull used the same construction method as the Porte 1 and measured 42 feet 2 inches from bow to stern, with two steps, and side fins 30 feet in length. Fitted with the mainplanes of an H.12, two 250 h.p. Rolls-Royce engines and a new tail unit, the machine, serialled No. 8650, was designated F.2 and proved vastly superior in performance to the standard H.12, taking off smoothly and easily at a loaded weight of 10,500 pounds. After some structural modifications were made in the light of operational experience, quantity production was authorised, the production version designated F.2A. Fitted with the more powerful Marks of the Rolls-Royce Eagle, the F.2A had a range and endurance more than adequate for defensive and offensive patrols, and a formidable armament consisting of two 230-pound bombs and up to five Lewis guns with excellent fields of fire. The fuel system, however, gave a lot of trouble, mainly due to its layout. A 409-gallon tank situated in the hull fed a 26-gallon gravity tank in the upper mainplane centre section by means of wind-driven pumps, the fuel then passing to the engines by gravity. Blocked pipes and filters, and fuel pump failures caused many forced alightings, and a contemporary report stated that ‘our real enemy is our own petrol pipes’. This situation led to the adoption of bizarre colour schemes for F.2A hulls, using red, white, and yellow paint, so that stricken machines could be readily spotted and towed home. Production F.2As began to appear late in 1917, a sub-contract having been arranged with Short Brothers, of Eastchurch. These machines had a two-stepped hull, only slightly differing from that of the F.2. In the bows, the front gunner’s cockpit was equipped with twin Lewis guns on a Scarff ring-mounting, while the rear gunner was positioned aft of the lower mainplane with similar armament. Some aircraft also had single guns, fired from side-hatches in the hull. The first and second pilots, the latter acting as front gunner, were partially enclosed in a glazed cabin, although this was often removed to improve visibility and performance. Engine control was simplified by the employment of an engineer-gunner, positioned in an internal compartment and controlling engine starting and inflight temperatures. The fourth crew member was usually a rigger-gunner. This crew arrangement tended to make the boats less dependent on their bases for servicing and minor repairs, and was standard in all large R.N.A.S. flying-boats. The F.2A power units were two Rolls-Royce Eagle VI Ils, developing 346 h.p. at 1,800 r.p.m. and driving four-bladed tractor propellers, the revolutions of which were reduced to 1,080 r.p.m. by epicyclic gearing. Some of the early F.2As had fabric decking to their hulls, but the ravages of wind and weather soon indicated its weakness and later machines had plywood decking. Production was greatly facilitated by the fact that the relatively simple hull construction did not call for highly skilled labour, and also by the availability of H.12 components, but demands for Rolls-Royce engines so far exceeded the supply that the total number of F.2As on charge never reached official requirements. To offset this situation several H.12s were rebuilt with Porte hulls and F.2A tail units, these modifications rendering them indistinguishable from F.2As.

Together, the F.2As and H.12s rendered great service in the critical year of 1917, when U-boat warfare was at its height. The first success came on 20 May, when the H.12 commanded by Fit. Sub-Lieut. Morrish destroyed submarine UC-36, and by the end of the year the flying-boats had sighted sixty-seven U-boats and had attacked forty-four. The Zeppelins, too, came in for attention, and on 14 May, 1917, L.22 fell to the guns of H.12 No. 8666, captained by Fit. Lieut. Galpin. In June, L.43 was destroyed by H.12 No. 8677, and a year later an F.2A from Killingholme, flown by Captains Pattinson and Munday, was responsible for the destruction of L.62 over the Heligoland minefields. All this activity took place in the face of strong German opposition, mainly from seaplanes under the command of the German Naval ‘ace’, Christiensen, and many combats took place, culminating in a pitched battle on 4 June, 1918. On that day, Capt. Robert Leckie led a force of four F.2As and a single H.12 on an offensive patrol towards the Haaks Light Vessel, three hours flying time from Felixstowe. After two-and-a-half hours, one of the F.2As was forced down by a broken petrol feed pipe, and its pilot, Capt. R. F. L. Dickey, had no choice but to taxi to the Dutch coast. On the way, five German seaplanes made a half-hearted attack upon the crippled machine, losing one of their number to its gunners, the rest breaking off the action, hotly pursued by the H.12, while the three F.2As formed a protective circle over Dickey’s machine. Soon afterwards, a formation of ten more German seaplanes arrived and Leckie charged them head-on, losing his wireless aerial on the upper wing of the enemy leader and splitting up the formation. The battle which followed lasted forty minutes, during which time the flying-boats shot down two Germans and probably destroyed four more without loss to themselves, although one F.2A went down on the Zuider Zee with a broken petrol pipe during the action. This was repaired by the engineer, however, and the machine rejoined the others. On the way back to Great Yarmouth, Capt. J. Hodson’s aircraft had an engine failure, flight being maintained on half-power while repairs were effected. Two flying-boats had been lost, for the H.12 force-landed in Dutch waters also, and both crews were interned. In 1918 the range of the flying-boats was extended by the use of special lighters designed by Porte, the machines being floated on to the fighters and towed by destroyers to a launching point off the German coast, returning after reconnaissance flights to be towed home. This system had its limitations, but several successful operations were completed. Another method of extending range was the carriage of extra fuel in cans, and by this means flights of over nine hours’ duration were made, pilot fatigue being minimised by the fitting of dual control to the F.2A.

Two illustrations are on record to prove the strength of the F.2A; in one, a machine was actually looped over Killingholme by an aggrieved American trainee, and in the other a single-engined approach aimed at Leeds Reservoir was misjudged and terminated in a ploughed field, the only damage incurred being strained bracing wires.

SPECIFICATION

Power Plant:

F.2 and H.12 - Two 250 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle I

F.2A - Two 345 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII

Span: F.2, F.2A, and H.12 - 95 feet 7 1/2 inches

Length:

H.12 - 46 feet 6 inches

F.2 and F.2A - 46 feet 3 inches

Weight Loaded:

H.12 - 10,650 pounds

F.2 - 10,000 pounds

F.2A - 10,978 pounds

Total Area: F.2, F.2A, and H.12 -1,133 square feet

Max. Speed:

H.12 - 85 m.p.h.

F.2 - 95 m.p.h.

F.2A - 95-5 m.p.h.

Endurance: F.2, F.2A, and H.12 - 6 hours (normal)

Armament:

H.12 - Up to four Lewis guns on flexible mountings in bow and pilot’s cockpit. Four 100-pound or two 230-pound bombs

F.2 - Experimental gun installations for F.2A, max. bomb load of 460 pounds

F.2A - Four to seven Lewis guns on flexible mountings, two 230-pound bombs�

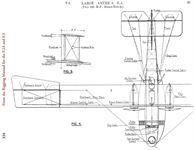

Porte/Felixstowe F.2C (1917)

An experimental version of the F.2A, the F.2C did not pass beyond the prototype stage. It was fitted with a modified hull of lighter construction, having alterations to the front gun position, an open cockpit for the pilots, and no hull side hatches. The F.2C power units were initially 275 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle Ils, later replaced by the 322 h.p. Eagle VI. Official trials took place on 23 June, 1917, the machine showing a slightly better performance than the F.2A, but the margin was too small to justify interference with the F.2A production programme. However, the F.2C, serialled N65, saw active service with the R.N.A.S. at Felixstowe and on 24 July, 1917, flown by Wg. Cmdr. Porte, released two of the five 230-pound bombs which sank submarine UC-1. Some time later the machine was fitted with experimental pneumatic bomb-release gear which chose to be temperamental at the worst possible moment resulting in a surfaced U-boat escaping unscathed.

SPECIFICATION

Power Plant: Two 275 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle II or 322 h.p. Eagle VI

Span: 95 feet

Length: 46 feet

Weight Loaded: 10,240 pounds

Total Area: 1,136 square feet

Max. Speed: 98-5 m.p.h.

Endurance: 6-5 hours

Armament: Two Lewis guns, two 230-pound bombs

Porte/Felixstowe F.5 (1918)

Intended as an improvement upon the F.3, the F.5 appeared in early 1918. Externally similar to its predecessors, and employing the standard Porte hull construction, it embodied a number of refinements developed as a result of experience with the previous designs. The top decking of the hull was deeper than before, and the pilots were seated in an open cockpit, while the gun positions were of the same arrangement as the F.3. Four 230-pound bombs could be carried in the standard underwing racks. The wing structure was entirely new, with a span greater than the F.3 and a modified section, also constant-chord ailerons. A broad-chord tailplane projected ahead of the fin leading edge, the rudder, and the ailerons, being horn-balanced. Serialled N90, the prototype was powered by two 350 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VIIIs driving four-bladed tractor propellers, and on its official trials it displayed a much better performance than the F.3, even under conditions of overload. Unfortunately, the prototype F.5 fell foul of economics, for the large F.3 construction programme did not readily permit the introduction of a new type. A compromise was reached with the extensive modification of the F.5 to incorporate as many F.3 components as possible, resulting in a machine not wholly satisfactory, but nevertheless put into production. The hull of the modified machine was similar to that of N90, but its overall covering of plywood, with only the top decking of fabric, added considerably to the weight, which, in the completed aircraft, exceeded that of N90 by more than 1,000 pounds. The wing structure was that of the F.3, modified to take constant-chord ailerons, and the tail unit was identical to that of the prototype, although later F.5s had horn-balanced elevators. The slightly greater wing span of the F.5 as compared to the F.3 was accounted for by the ailerons, which extended beyond the wing-tips. Official test figures show that the performance of the production F.5 was inferior to that of the F.3, and in some instances this was further impaired by the fitting of lower powered engines, the 325 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VII.

Too late for operational service, the type was adopted as the R.A.F.’s standard post-war flying-boat and remained in service until replacement by Southamptons in 1925. In the summer of 1919, an early production F.5, N4044, toured Scandinavia to demonstrate the capabilities of flying-boats, covering 2,450 miles in 27 days and returning to Felixstowe fully serviceable. Another equally successful tour took place in 1923, when two F.5s commanded by Air Commodore Bigsworth completed a cruise to Gibraltar, Malta, Bizerta, and Oran without mishap.

Before the Armistice, F.5 production had started in Canada at the factory of Canadian Aeroplanes Ltd to the order of the United States Air Board. These machines were fitted with the Liberty 12 engine of 400 h.p. and equipped the U.S. Naval Air Service in 1918. A series of structurally modified F.5s was also built by the U.S. Naval Aircraft Factory at Philadelphia; these too had the Liberty engine and were designated F.5L. The F.5L could carry 1,000 pounds of bombs and up to eleven machine-guns, and some mounted a Davis quick-firing gun in the bows. These machines gave years of service to the U.S. Navy,both in the Atlantic and the Pacific Fleets, later versions having a greatly enlarged fin and a horn-balanced rudder. Also in America, two converted F.5Ls formed the equipment of one of the first airlines to operate flying-boats, Aeromarine West Indies Airways, Inc., in 1920. In 1921, the Japanese company, Aichi of Nagoya, obtained a licence to build F.5s and produced fifteen machines which served with the Imperial Japanese Naval Air Service and made several notable long-distance flights, recording durations of over nine hours in some cases. In this country, the F.5 was used for a number of experiments, among which were the trial of auxiliary aerofoil aileron balances on N4838, and the fitting of a special hollow-bottom Saunders hull to N178. In 1924, Short Brothers produced an F.5, N177, with an all-metal hull, the first military flying-boat in the world to be so fitted. The F.5 formed the equipment of eight R.A.F. squadrons, a ninth, No. 230, being renumbered No. 480 Flight at the end of 1922 and forming the training establishment for flying-boats at Calshot.�

SPECIFICATION

Power Plant:

Prototype - Two 350 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII

Production - Two 350 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII or two 325 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VII

Canadian F.5s and American F.5Ls - Two 400 h.p. Liberty 12

Span: 103 feet 8 inches

F.5L-103 feet 9 inches

Length : 49 feet 3 inches

Prototype - 49 feet 6 inches

Weight Loaded: 12,682 pounds

Prototype - 12,268 pounds

F.5L - 13,000 pounds

Total Area: 1,409 square feet

F.5L - 1,397 square feet

Max. Speed:

Prototype - 102 m.p.h.

Production - 88 m.p.h.

F.5L - 87 m.p.h.

Endurance: 7 hours (normal)

F.5L - 7-9 hours

Armament:

Four Lewis guns, four 230-pound bombs

Canadian machines could have up to eight Lewis guns

F.5L - maximum armament of one Davis gun, eleven Lewis guns. Normal armament was one Davis gun, four Lewis guns, and four 230-pound bombs or two 500-pound bombs�

Показать полностью

J.Bruce British Aeroplanes 1914-1918 (Putnam)

Felixstowe F.2A and F.2C

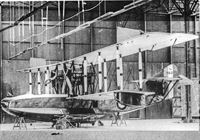

AFTER the success which had been achieved with the F.1, Squadron Commander Porte extended his A experiments to larger hulls. He began work with No. 8650, the first Curtiss H.12 flying boat to be delivered to the R.N.A.S.

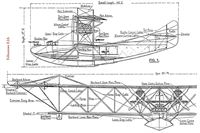

The H.12 was generally similar in design to the H.4, but was considerably larger. On its appearance in service it was named the Large America, whereafter the H.4 was known as the Small America. As delivered, the H.12 had two 160 h.p. Curtiss engines, but when Porte began his experiments with No. 8650, these proved to be insufficiently powerful to get the boat off the water at a weight of 8,700 lb. The Curtiss engines were replaced by two 250 h.p. Rolls-Royce engines. Take-off was then accomplished, but with difficulty, owing to lack of buoyancy forward. The hull of the H.12 was weak structurally, yet these Large Americas did some excellent work when powered by two Rolls-Royce Eagle engines of later marks.

It was obvious that the F.1 hull was superior to that of the Curtiss H.12, so it was decided to build a hull similar to the Porte I but large enough to take the wings of the Large America. The new hull was known as the Porte II, and the aircraft to which it was fitted was designated F.2. It was the prototype of the line of successful F-boats, which gave such distinguished service up to and beyond the Armistice.

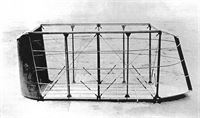

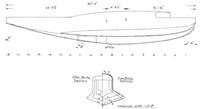

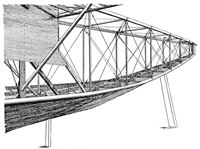

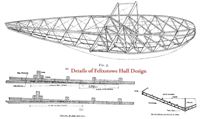

The F.2’s hull was almost identical to that of the F.1 in outline but was larger: it was 42 feet 2 inches long, and its maximum beam was 10 feet. It had only two steps, and these were applied outside the skin of the hull, as had been done on the F.1. The forward step was directly under the rear spar of the wings, and the rear step was 6 feet 5 inches farther aft. Structurally the hull was basically a cross-braced box girder, as opposed to the original Curtiss boat-built hull. Forward of the rear spar of the centre-section the sides of the hull were braced as N-girders; elsewhere the cross-bracing was by means of wires or tie-rods. The spars of the lower centre-section were integral parts of the hull box girder. The bottom longerons were spaced by solid mahogany members known as floors: these floors were inverted triangles whose downwards-pointing apices formed the ridge of the keel. Athwartships they were unbroken, but for two- thirds of their depth they were notched out to fit over the solid keelson, which was correspondingly notched out for one-third of its depth and ran from bows to sternpost as a continuous structural member.

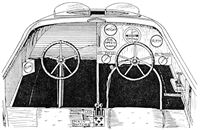

As on the F.1, hull, the side fins were built on to the outside of the basic hull structure. To give adequate support to the planking between floors, intermediate timbers of rock elm ran from chine to chine. The double-diagonal planking consisted of an inner skin of 1/8-inch cedar and an outer of 3/16-inch mahogany separated by a layer of varnished fabric. This planking was applied to the hull bottom, whilst the fin tops and the hull sides were planked with three-ply; abaft the rear spar the hull sides were fabric-covered and had a solid mahogany washboard along the lower longerons. The top of the hull was also fabric-covered, with the exception of the portion in front of the cockpit, which was planked with plywood. A semi-enclosed cabin was provided for the crew. The shape of the hull was such that the tail was carried high: this served not only to keep the tailplane out of spray when taxying, but also to give the waist gunners a good field of fire towards the rear.

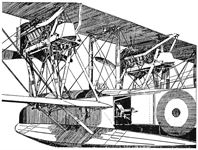

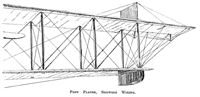

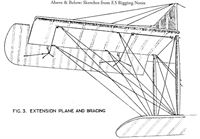

The wings were similar to those of the Curtiss H.12. The upper mainplanes had long extensions, the landing wires for which ran from rectangular pylons above the outermost interplane struts: these pylons were faired over with fabric, but the resulting vertical surfaces had no designed aerodynamic function. There were three bays of struts outboard of the engines.

The Porte II hull proved to be an excellent design, and the F.2 was strong and seaworthy. One of the great advantages of the Porte design of hull was its structural simplicity, which enabled it to be made by firms which had no experience of boat-building. The type was placed in production with several contractors in 1917, but delays occurred: an official decision to change from the original 23-inch gun-ring to one of 20-inch diameter necessitated structural modifications and held up. production.

The production machines had two 360 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII engines, and embodied other minor modifications. They were designated F.2A. Deliveries began to be made at the end of 1917, and from early 1918 until the Armistice the type was in use at almost every flying-boat station of the R.N.A.S. This widespread use gave some trouble with the early F.2A hulls, for the machine had been designed to operate from sheltered harbours, and exposure to unfavourable sea conditions led to deterioration of the hull. The original 5-inch planks on the hull bottom warped, the plywood on the fin tops and sides opened up, and the fabric rotted. Narrower planks were therefore fitted, double-diagonal planking of mahogany and cedar was applied to the fin tops, and the sides were either given single planking with fabric covering or were completely planked with Consuta, the special material invented by S. E. Saunders, Ltd. It consisted of plywood sewn with copper into large sheets. Other structural modifications had to be made to meet the rigours of operational service.

The estimated life of the F.2A under mooring conditions was six to eight months, but where hangar and slipway facilities were available the boats were taken ashore on wheeled trolleys specially made to conform to the shape of the hull bottom. Manhandling these relatively fragile wooden hulls could be a tricky business, and the beaching crew had to be both numerous and skilful. A vivid account of a launching, take-off, flight, and landing and beaching of an F.2A is to be found in pages 352-357 of The Story of a North Sea Air Station, by C. F. Snowden Gamble.

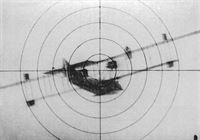

The flying boats of Felixstowe air station are probably best remembered for their connexion with the famous “Spider Web” patrol. This patrol was flown as an octagonal figure centred on the North Hinder Light Vessel. Sixty nautical miles across, it enabled some 4,000 square miles of sea to be systematically searched: this area lay across the most possible tracks of enemy submarines. The five flying boats which began to operate the Spider Web patrol on April 13th, 1917, made twenty-seven patrols before the month was out, sighted eight U-boats and bombed three of them, and had one engagement with enemy destroyers.

It was into action of this tradition that the F-boats came. Unfortunately, the shortage of Rolls-Royce engines severely hampered the production of the big flying boats. In May, 1917, when the requirements of aircraft for 1918 were under consideration, it was estimated that 180 flying boats of the Large America type would be needed. The Government’s decision to double the size of the British air services, taken in July, 1917, increased that number to 426. In view of the fact that the average life of a flying boat was six months, the total requirements for the full year of 1918 amounted to 852 flying boats. This figure was impossible of achievement, but the net requirements were reduced to 234 upon the U.S. Navy Department’s agreement to equip five seaplane stations and upon the decision to build at Malta the sixty boats required for the Mediterranean area.

By March, 1918, 161 F.2As had been ordered, but only ten were in service. The required total of 234 was to consist of both F.2As and the later F.3s, but it was never realised. A review of the production of Rolls-Royce engines showed that sufficient Eagles would be available to equip only 170 Large America boats by the end of May, 1918. Even that estimate proved to be over-optimistic, for only 104 F-boats had been delivered by that date.

All the big twin-engined Porte-designed flying boats were known as Large Americas, and it is difficult to distinguish one type from another or from the original Curtiss H.12 in the official history. The F.2A was the best-known boat of the series, partly because it was a better machine than the F.3 and partly because the F.5 arrived too late to see service on a large scale.

The R.N.A.S. air station at Great Yarmouth received the first of its F.2As early in February, 1918, but trouble was experienced with the fuel system. The main fuel tanks were in the hull, and petrol was pumped to a gravity tank in the centre-section by means of wind-driven pumps; the carburettors were fed from the gravity tank. The total length of piping in the system was therefore considerable, and most of the faults occurred in the fuel pipes. On February 5th, 1918, the first patrol to be attempted by a Great Yarmouth F.2A was balked by a partial choke in a petrol pipe, and eleven days later the same machine, N.4511, was forced down one hour out from base with the gravity tank filter clogged. The crew were picked up by H.M.S. Glowworm, and owed their rescue to a home-made precursor of the dinghy radio developed in World War II. Leading Mechanic Walker had been experimenting at Yarmouth with a 5-foot linen box kite carrying an aerial, and on this occasion he had his apparatus with him on board N.4511. From its signals the position of the flying boat was fixed, and H.M.S. Glowworm found it only eight miles down wind from the position she was given.

The F-boats from Yarmouth and Felixstowe had many brushes with the Brandenburg W.12 and W.29 seaplane fighters from the enemy seaplane stations at Borkum, Norderney and Zeebrugge. The boats usually gave as good as they got, for their heavy defensive armament and the determination of their crews made up for their lack of speed and manoeuvrability.

On June 4th, 1918, five flying boats led by Captain R. Leckie set out for the Haaks Light Vessel with the one intention of seeking out and fighting enemy seaplanes. The force consisted of four F.2As and one Curtiss H.12: the F.2As were N.4295 and N.4298 from Great Yarmouth, and N.4302 and N.4533 from Felixstowe; whilst the H.12 was 8689 from Felixstowe. But even before the enemy were sighted the petrol feed pipe to one of the engines of N.4533 broke, and the F.2A was forced down. Its pilot (Captain Dickey) could do no more than taxi to Holland, where he beached and burned the machine. The H.12 had set off in hot pursuit of some German machines which had attacked and were intent on harassing the limping N.4533, and the three remaining F.2As were later engaged by a mixed force of fourteen enemy seaplanes. The F.2As fought an action which must rank as a veritable Jutland of the skies, and Leckie led the little force with magnificent audacity. N.4302 was compelled to go down with a broken petrol pipe, and Captain Hodson flew N.4289 on one engine whilst the other was repaired during the combat. The engineer of N.4302, Private Reid, made a temporary repair which enabled the boat to return to Great Yarmouth, despite a damaged wing-tip float.

At 7.10 p.m. the three F.2As alighted in Great Yarmouth Roads after being airborne just over six hours and fighting one of the greatest air battles of the war, for the enemy lost six seaplanes. But Leckie’s report included the acrid comment: “It is again pointed out that these operations were robbed of complete success entirely through faulty petrol pipes.... It is obvious that our greatest foes are not the enemy, but our own petrol pipes.”

This action was largely responsible for the general adoption of the gaudy “dazzle-painting” of many F-boats. The F.2A flown by Captain Hodson, N.4289, “was terrible in appearance, painted post-box red, with yellow lightning marks running diagonally across her ... he fondly hoped that this would put the wind up the Hun.” Whether it did that or not is not known, but it left Hodson’s comrades in no doubt about his aircraft’s identity. The first object of the dazzle-painting was to identify the pilot of any particular flying boat, so, at Great Yarmouth, the choice of scheme was left to individual pilots. This produced some bizarre combinations of checks, stripes and zig-zags in bright colours. Felixstowe had a more or less standard (but no less striking) colour scheme for its boats.

One of the Felixstowe F.2As was experimentally fitted with two “howdah” gun positions on the upper wing. Each contained a gunner and twin Lewis guns on a Scarff ring. The bow gunner also had twin Lewis guns, and it seems probable that the machine was intended to act as an escort fighter for the patrolling F.2As. The experiment was not a success, however, and the idea was abandoned.

On May 10th, 1918, an F.2A from Killingholme, flown by Captains T. C. Pattinson and A. H. Munday, engaged the Zeppelin L.62 at 8,000 feet over the Heligoland minefields. Captain Munday opened fire from the bow cockpit and Sergeant H. R. Stubbington, the engineer, also brought his Lewis gun to bear on the target. Many hits appeared to be scored, but the flying boat broke an oil feed pipe and had to alight on the sea. The Zeppelin made off due east, losing height and emitting smoke, and soon afterwards blew up and fell in flames.

A most ambitious scheme in which F.2A flying boats were concerned was the use of lighters, towed by destroyers, as a means of increasing the radius of action of the flying boats. The idea had first been proposed by Squadron Commander Porte in September, 1916. His original design was for a channel-shaped lighter which could be submerged by the flooding of tanks; after the flying boat had been floated into position, the water was blown out of the tanks by compressed air. This raised the flying boat clear of the water, and the lighter was free for towing.

Orders for four lighters were placed in January, 1917, and the first was successfully tested in the following June. As actually built, the lighter was made to submerge only at the stern and the flying boat was warped aboard. Towing trials promised well, and in September, 1917, a lighter with a flying boat aboard was towed at speeds up to 32 knots. Twenty-five lighters were ordered immediately, a number which was subsequently increased to fifty. The first was delivered in May, 1918, and fifty-one had been delivered by the time of the Armistice.

One of the chief objects of the use of lighter-borne flying boats was to carry out bombing attacks on the German naval bases in the North Sea, but their first use was to provide advanced take-off facilities for distant reconnaissances in the Heligoland Bight. The first operation of this kind took place on March 19th, 1918, apparently using three of the prototype lighters. At 5.30 a.m. three destroyers towed flying boats to a point off the German coast, and the three boats were airborne by 7 a.m. During their patrol they shot down one of two enemy seaplanes which attacked them, and flew back to their base direct. Next day the operation was successfully repeated, and the towed flying boats were used on several later occasions in 1918. The original intention of using the lighter-borne flying boats to bomb enemy naval bases was abandoned in July, 1918, by which time sufficient progress had been made with long-range bomber landplanes to bring the targets within their radius of action.

The F.2A remained in service right up to the time of the Armistice. Because its performance was better than that of the F.3 it was chiefly used from stations which covered the sea areas where fighting, anti-Zeppelin work and reconnaissance predominated. The F.3 was used at stations responsible for antisubmarine patrols, for which duty its longer range made it more suitable.

Many modifications were made to production F.2As: some were incorporated on the production lines; others were made locally at seaplane stations to meet the personal tastes of crews. One of the most noticeable changes Was the absence of the cabin top over the pilots’ cockpits on later F.2As: its removal improved their view considerably, particularly towards the rear, and added a few knots to the speed. Such F.2As began to appear about September, 1918. They also had the sides of the hull planked overall with mahogany or, in the case of the Saunders-built machines, Consuta.

A further significant modification, incorporated at this time, was the fitting of constant-chord horn-balanced ailerons similar to those of the F.5. This helped to relieve some of the considerable physical strain imposed upon the pilot; protracted patrols could be exhausting in a heavy aircraft which had no balanced controls of any kind. Several pilots went so far as to fit modified flight controls of their own design.

It is doubtful whether an F.2B variant was ever built, but the designation has been applied to the open-cockpit version of the F.2A. A modified type known as the F.2C was, however, built and flown. It had a lightened hull with modified steps and new contours for the forebody. The bow gunner’s cockpit was farther back from the bows than on the F.2A, and the cockpit for the pilots was open. A deep top-decking was fitted to the hull, and there were no waist hatches behind the wings.

Although the F.2C did not go into production, it was used operationally by the War Flight at Felixstowe seaplane station. On July 24th, 1917, Felixstowe sent out a patrol of five flying boats, the greatest number despatched together up to that time. The patrol was led by Wing-Commander Porte himself in the F.2C. Near the North Hinder Light Vessel, the periscope of a U-boat was sighted. Three of the flying boats dropped a total of five 230-lb bombs on the submarine and sank it: two of the bombs were, dropped by the F.2C, which thus played a leading part in the destruction of the enemy submarine U.C.1.

The F.2C was fitted with an experimental bomb-dropping gear which was actuated by compressed air instead of the simple Bowden cable mechanism which was used on the other F-boats. The compressed air gear was elaborate and not wholly reliable: at least one enemy submarine owed its escape to the gear’s defection one day late in September, 1917, when the F.2C was being flown by Squadron Commander T. D. Hallam, D.S.C. He attacked a surfaced U-boat, but his bombs failed to leave the racks.

SPECIFICATION

Manufacturing Contractors: The Aircraft Manufacturing Co., Ltd., Hendon, London, N.W.; hulls made by May, Harden & May, Southampton Water. S. E. Saunders, Ltd., East Cowes, Isle of Wight (built 100 F.2As). The Norman Thompson Flight Co., Bognor Regis (F.aAs built at the Littlehampton works; production may have consisted of hulls only).

Power: F.2A: two 345 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII. F.2C: two 275 h.p. Rolls-Royce Mk. II (322 h.p. Eagle VI).

Dimensions: Span: upper (F.2A) 95 ft 7 1/2in.; (F.2C) 95 ft; lower (F.2A) 68 ft 5 in. Length: F.2A, 46 ft 3 in.; F.2C, 46 ft. Height: 17 ft 6 in. Chord: 7 ft 1 in. Gap: 7 ft 1 in. Stagger: nil. Dihedral: 1°. Incidence: 4° 15'.

Areas: Wings: F.2A, 1,133 sq ft. F.2C, 1,136 sq ft.

Tankage: F.2C: petrol, 220 gallons; oil, 16 gallons.

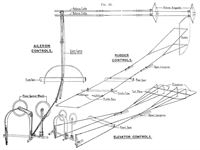

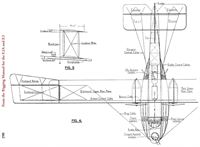

Armament: Four Lewis machine-guns were usually carried: one was on a Scarff ring-mounting on the nose cockpit; another was mounted in the upper rear cockpit behind the wings; and there was one in each waist position. Sometimes a double-yoked pair of Lewis guns were carried in the bow and upper rear cockpits, and frequently an additional Lewis was mounted on top of the pilots’ cockpit canopy. Two 230-lb bombs were carried in racks under the lower mainplane.

One experimental F.2A had a “howdah” gunner’s cockpit let into each upper mainplane above the first pair of interplane struts outboard of the engines. Each gunner had a pair of double-yoked Lewis guns on a Scarff ring-mounting.

F.2C: twin Lewis guns on Scarff ring-mounting on bow cockpit. Two 230-lb bombs under each lower wing.

Service Use: Flown from R.N.A.S. seaplane stations at Felixstowe, Great Yarmouth, Killingholme, Calshot, Dundee, Scapa Flow and Tresco, Scilly Isles (later No. 234 Squadron); No. 230 Squadron, R.A.F.

Distribution: On October 31st, 1918, the R.A.F. had fifty-three F.2As on charge. All were at seaplane stations in the United Kingdom; none were overseas.

Serial Numbers: N.4080-N.4099: ordered as F.2As from S. E. Saunders; some delivered as F.5s. N.4280-N.4309: ordered as F.2As from S. E. Saunders. N.4430-N.4479: ordered as F.2As from S. E. Saunders; some delivered as F.5s. N.4480-N.4504: ordered as F.2As from the Aircraft Manufacturing Co. (May, Harden & May); some delivered as F.5s. N.4510-N.4519: built by the Aircraft Manufacturing Co. (May, Harden & May). It was at one time intended to fit Sunbeam engines to these ten F.2As. N.4530-N.4554: built by the Aircraft Manufacturing Co. (May, Harden & May). Between N.4560 and N.4568 were F.2As. It is believed that N.4584 was an F.2A. N.65: the F.2C.

Weights (lb) and Performance:

Type F.2A F.2C

No. of Trial Report N.M. 125 -

Date of Trial Report March, 1918 June 23rd, 1917

Type of airscrew used on trial A.B.665 A.B.665

Weight empty 7,549 6,768

Military load 585 402

Crew 720 720

Fuel and oil 2,124 2,350

Weight loaded 10,978 10,240

Maximum speed (m.p.h.) at

2,000 ft 95-5 98

6,500 ft 88-5 94

10,000 ft 805 91

m. s. m. s.

Climb to

2,000 ft 3 50 4 50

6,500 ft 16 40 18 20

10,000 ft 39 30 38 00

Service ceiling (feet) 9,600 10,300

Endurance (hours) 6 -

Notes on Individual Machines: F.2As used at Great Yarmouth: N.4283, N.4289, N.4295, N.4298, N.4303, N.4305,

N.4511, N.4512, N.4549, N.4550. F.2As used at Felixstowe: N.4302 and N.4533. F.2As used at Killingholme: N.4287, N.4290, N.4291, N.4516. N.4545 had the later open cockpit for the pilots.

Costs:

F.2A flying boat including hull and trolley, but without engines, instruments and guns £6,738 0s.

Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII engine, each £1,622 10s.

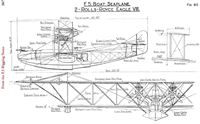

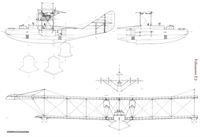

Felixstowe F.3

ALTHOUGH the F.3 was almost indistinguishable from the F.2A and was produced in larger numbers, it was not so well-liked as the earlier design. The F.3 was a rather larger flying boat and could carry double the load of bombs on the same power, but it did not handle so well as the F.2A.

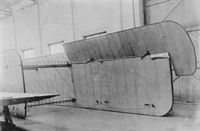

The hull was very similar to that of the F.2A, but was about three feet longer. The “fuselage-type” construction was again employed, but an unfortunate change was made in the design of the floors: instead of being continuous athwartships, as on the F.2A, they were made in two halves, each of which was rebated into the keelson on either side. This produced an unsatisfactory structure, and the planking sprang readily along the garboard strake, with subsequent leakage. Intermediate timbers were later introduced to support the planking, but the F.3 hull was never so satisfactory as that of the F.2A. The hull was planked in the same way as that of the F.2A. As on the earlier aircraft, the birch three-ply covering of the fin tops was later replaced by double-diagonal planking.

The wings were of greater span and chord, but the interplane bracing was of the same configuration as that of the F.2A. The leading edge of the upper wing was slightly recessed immediately behind the airscrews. On the prototype F.3 a vertical surface was fitted between the first pair of interplane struts outboard of the engines, but this feature was not reproduced on later machines.

The prototype, N.64, was tested with two 320 h.p. Sunbeam Cossack engines, but production F.3s had two Rolls-Royce Eagle VIIIs which drove opposite-handed airscrews. The tail-unit was indistinguishable from that of the F.2A; The wing-tip floats were the same as those of the earlier type, and therefore did not quite reach the trailing edge of the lower wing. It appears that N.64 was used operationally, for an F.3 was reported in use with Felixstowe’s War Flight as early as July, 1917, long before production F.3s were available. (This first F.3 survived until May 15th, 1918, when it was written off at Felixstowe.)

The F.3 was ordered in such quantities that it seems that it was preferred to the F.2A, possibly because of its larger bomb load. The allocations of serial numbers for batches of F.2As and F.3s (though by no means a reliable guide) seem to indicate that orders for the two types of flying boat were placed simultaneously. Production was begun in 1917 by several contractors.

There are indications that Porte and his colleagues had misgivings about the official decision to produce the F.3 in such quantities; and indeed the decision’s effect was to reach beyond the type F.3 itself, for it later affected the F.5 also. By March, 1918, orders for F.3s totalled 263; only one was in service at that time.

The shortage of Rolls-Royce engines had an adverse effect upon the production of F.3s just as it had held up the F.2A. It had been known as early as the spring of 1917 that the demands of home seaplane stations would absorb all the flying boats that could be built in Britain: this situation is analysed in some detail in the history of the F.2A. In the Mediterranean there was, however, a clamant need for flying boats for anti-submarine patrols, and it was therefore decided to build F.3s at Malta. Local labour was employed. The men, who were expert boat-builders, had no difficulty in making the simple Porte-type hulls, and Maltese women were employed as fabric workers under the supervision of Lady Methuen, the wife of the Governor of the island. The first Maltese-built F.3 was completed in November, 1917, and seventeen more were built there during the following twelve months.

Because of its greater range and inferior performance relative to the F.2A, the F.3 was used from seaplane stations responsible for anti-submarine patrols rather than fighting. The type had the added distinction of serving in the Mediterranean; one accompanied the Allied fleet in its attack upon the Albanian port of Durazzo on October 2nd, 1918.

The flight condition of the F.3 depended upon the nature of its duty and upon the duration of the flight. It was loaded to four different flight conditions, as the performance tables show.

In the experimental field, an F.3 was used to test servo-operated controls; and another was fitted with the automatic landing device invented by Major A. Q. Cooper. A long arm, connected to the pilot’s control column by an elastic linkage, was allowed to trail below the aircraft in flight; on striking the water the arm moved the control column backwards and automatically rounded-out the boat’s approach. Success was not achieved at once, but fully automatic landings were ultimately accomplished.

The prototype F.3 had flown as early as February, 1917, and the production machines were contemporary with the production F.2As. After the Armistice, the F.3 was withdrawn in favour of the F.2A and the F.5, and was finally declared obsolete in September, 1921.

SPECIFICATION

Manufacturing Contractors: Dick, Kerr & Co., Ltd., Preston; The Phoenix Dynamo Manufacturing Co., Ltd., Bradford; Short Brothers, Ltd., Rochester; Dockyard Constructional Unit, Malta.

Power: Prototype: two 320 h.p. Sunbeam Cossack. Production: two 345 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII.

Dimensions: Span: upper 102 ft, lower 74 ft 2 in. Length: prototype 45 ft, production 49 ft 2 in. Height: prototype 18 ft, production 18 ft 8 in. Chord: 8 ft. Gap: 8ft 6in. Stagger: nil. Dihedral: 1° 30'. Incidence: 4°. Span of tail: 22 ft. Airscrew diameter (Eagles): 10 ft.

Areas: Wings: 1,432 sq ft. Ailerons: each 65 sq ft, total 130 sq ft. Tailplane: 118 sq ft. Elevators: 67 sq ft. Fin: 37-2 sq ft. Rudder: 30-3 sq ft.

Tankage: Petrol, maximum: 400 gallons. Oil: 15 gallons.

Armament: One Lewis machine-gun on rotatable mounting on bow cockpit; one on cockpit aft of wings; and one in each waist position. Four 230-lb bombs were carried in racks under the lower wings.

Service Use: Used from seaplane stations at Felixstowe, Cattewater, Houton Bay, Scilly Isles, and flown in the Mediterranean, probably from Taranto.

Distribution: On October 31st, 1918, the R.A.F. had ninety-six F.3 flying boats on charge. Eighteen were attached to the Grand Fleet for patrol duties; twenty-six were at various seaplane stations and three others were at non-operational stations in the United Kingdom; thirteen were in the Mediterranean; one was at an Aeroplane Repair Depot; eighteen were with contractors; and seventeen were in store.�

Weights (lb) and Performance:

Engines Two 320 h.p. Sunbeam Cossack Two 345 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII

Flight condition - Light load Medium load Normal load Overload

No. of Trial Report - N.M.155 N.M.155 N.M.155 N.M.155

Date of Trial Report February 9th, 1917 and April 19th, 1917 April 26th, 1918 April 26th, 1918 April 29th, 1918 May 7 th, 1918

Type of airscrew used on trial A.B.586 A.B.665 A.B.665 A.B.665 A.B.665

Weight empty 8,270 7,958 7,958 7,958 7,958

Military load Nil 238 1,317 1,461 1,461

Crew 900 720 720 720 720

Fuel and oil 2,455 836 2,089 2,096 3,142

Weight loaded 11,625 9,752 11,084 12,235 13,281

Maximum speed (m.p.h.) at

400 ft 88-5 - - - -

2,000 ft - 93 92,5 91 90

6,500 ft - 91-5 - 86 87

10,000 ft - 87-5 - - -

m. s. m. s.

Climb to

2,000 ft 3 00 3 10 4 00 5 25 7 50

6,500 ft 27 00 12 55 18 00 24 00 41 00

10,000 ft 60 00 24 50 41 30 - -

Service ceiling (feet) - 12,500 10,000 8,000 6,000

Endurance (hours) - 2 1/4 6 6 9 1/2

Serial Numbers: N.64: prototype F.3. N.4000-N.4049: ordered as F.3s from Short Bros., some delivered as F.5s. N.4100-N.4159: built by Dick, Kerr & Go. N.4160-N.4179: built by Phoenix Dynamo Manufacturing Co. N.4180-N.4229: ordered as F.3s from Phoenix Dynamo Manufacturing Co.; some delivered as F.5s. N.4230- N.4279: built by Dick, Kerr & Co. N.4310-N.4321: built at Malta Dockyard. N.4370: built at Malta Dockyard. N.4400-N.4429: built by Phoenix Dynamo Manufacturing Co.

Notes on Individual Machines: Used at Tresco, Scilly Isles (later No. 234 Squadron): N.4000, N.4001, N.4002, N.4234, N.4238, N.4240, N.4241, N.4415.

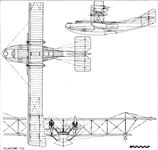

Felixstowe F.5

THE designation F.5 was applied to two different flying boats. The first was the boat whose serial number was N.90, and was John Porte’s last Felixstowe biplane design.

The hull was structurally similar to Porte’s earlier hulls, but was rather deeper and had no cabin enclosure for the crew. The sides abaft the mainplanes were fabric-covered and had the usual mahogany washboard along the entire length of their lower edges. The F.5 hull was regarded as the best of the Porte hulls, with the possible exception of that of the Felixstowe Fury, which had the inherent advantage of greater size.

The wing structure was almost identical to that of the F.3, but the ailerons were horn-balanced and rectangular in shape, whereas those of the earlier F-boats had retained the inverse taper of the ailerons of the original Curtiss design. The trailing edge of the ailerons lay behind that of the upper wing. A different wing section was employed.

The tail-unit was very similar to that of the F.2A and F.3, but the chord of the tailplane was greater and the surface projected in front of the leading edge of the fin. The rudder had a balancing surface inset into the fin.

The original F.5 was an excellent flying boat, and would probably have been a much better proposition than the F.3 for large-scale production. However, the F.3 had already been put into production with several manufacturers, and the Ministry of Munitions set its hand against the new jigs and templates which would have been required to produce the F.5.

A type of flying boat was produced under the designation F.5, but it differed considerably from N.90. The hull was a hybrid in which as many F.3 components as possible were used to produce a hull with approximately the characteristics of the original F.5 design. The hull was planked overall, and this stronger covering together with the modifications made the hull of the production F.5 appreciably heavier than that of the original machine.

The wings of the production aircraft were identical to those of the F.3, and reverted to the R.A.F. 14 aerofoil section of the earlier boats. However, the modifications necessary to make the wings suitable for production increased their weight; adapters were fitted to accommodate either Rafwires or stranded cables for the interplane bracing; and permanent slinging gear was fitted. Rectangular horn-balanced ailerons similar to those of N.90 altered the shape of the wing-tips.

The tail-unit was similar to that of N.90: the balanced rudder was retained, and the elevators had horn balances. At the Isle of Grain an F.5 was flown with experimental aileron balances of the “park bench” type, as fitted to the Avro Manchester and Bristol Badger.

Production F.5s appeared too late for the type to see operational service; none were recorded as on charge with the R.A.F. on October 31st, 1918. Contracts for all types of flying boats were cancelled or reduced after the Armistice, and a number of F.5s went into store, whence they were later withdrawn and reconditioned for the equipment of the R.A.F.’s flying boat units in the years following the Armistice. The type was adopted as the standard Service flying boat.

With the F-5, the wheel of flying boat design turned full circle, for the type was produced in America, and was the U.S. Navy’s standard flying boat in the early 1920s. The American machines were powered by two Liberty engines of 400 h.p. each, and the aircraft was known as the F-5L. Later F-5Ls had a modified fin and rudder assembly: the leading edge of the fin was rounded, and the rudder had a horn balance. The armament of the F-5L could include a 1 1/2-pounder quick-firing gun, presumably for anti-submarine work.

In late 1919 the Aeromarine Plane & Motor Company of Keyport, New Jersey, modified two F-5Ls to accommodate twelve passengers in two cabins within the hull, which was provided with circular windows. This conversion was known as the Aeromarine Model 75, and the boats were used on the Key West-Havana route operated by Aeromarine West Indies Airways, Inc. They carried hundreds of prohibition-weary passengers to and from Cuba without incident until the collapse of the operating company in 1923, when the air-mail subsidies were withdrawn.

A proposal was made in 1920 for the commercial operation of F.5s between the West Indies and Venezuela, but it came to naught.

Japan bought fifteen F.5s for use by the Imperial Japanese Naval Air Service in 1921. These machines gave excellent service and were particularly useful to the British Air Mission which went to Japan in 1921. The F.5s made a number of commendable long-distance flights, and on several occasions were airborne for more than nine hours.

In the post-war years, two experimental conversions of the F.5 appeared. The more significant of the two was N.177, otherwise the Short S.2, which had an all-metal hull designed and made by Short Bros.: it was claimed to be the first flying boat in the world to be so equipped. Earlier in point of time was N.178, which had a special hollow-bottom hull made by S. E. Saunders.

SPECIFICATION

Manufacturing Contractors: The Gosport Aviation Co., Ltd., Gosport; The Aircraft Manufacturing Co., Ltd., Hendon, London, N.W. (May, Harden & May, Southampton Water); Phoenix Dynamo Manufacturing Co., Ltd., Bradford; S. E. Saunders, Ltd., East Cowes, Isle of Wight; Short Bros., Rochester; Canadian Aeroplanes, Ltd., Toronto, Ontario, Canada; U.S. Naval Aircraft Factory, League Island, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S.A.

Power: British-built F.5: two 325 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VII; two 350 h.p. Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII. Canadian-built F.5: two 400 h.p. Liberty 12. F-5L: two 400 h.p. Liberty 12.

Dimensions: Span: upper 103 ft 8 in., lower 74 ft 2 in. Length: 49 ft 3 in. Height: 18 ft 9 in. Chord: 8 ft. Gap: 8 ft 6 in. Stagger: nil.

Areas: Wings: 1,409 sq ft. Tailplane and elevators: 178 sq ft. Fin: 41 sq ft. Rudder: 33 sq ft.

Data for F-5L: Weight empty: 8,250 lb. Weight loaded: 13,000 lb. Maximum speed: 87 m.p.h. Climb to 2,625 ft: 10 min. Endurance: 10 hours.

Armament: One Lewis machine-gun on rotatable mounting on bow cockpit; one in cockpit aft of wings; and one in each waist position. The F-5L had additionally a 1 1/2-pounder quick-firing gun, and could be armed with as many as eleven machine-guns. Four 230-lb bombs were carried on racks under the lower wings.

Use: Seaplane stations at Felixstowe, Calshot, Mount Batten, Great Yarmouth. No. 230 Squadron, R.A.F. (later No. 480 Flight) Calshot. Navigation Training Flight, Calshot.

Serial Numbers: N.90: prototype F.5. Some of batch N.4000-N.4049, originally ordered as F.3s from Short Bros.; N.4039, N.4041 and N.4044 known to have been F.5s. Some of N.4080-N.4099, ordered as F.2As from S. E. Saunders; N.4091 known. Some of N.4180-N.4229, ordered as F.3s from Phoenix Dynamo Manufacturing Co.; N.4192 and N.4193 known. Some of N.4430-N.4479, ordered as F.2As from S. E. Saunders; N.4462 and N.4467 known. Some of N.4480-N.4504, ordered as F.2As from the Aircraft Manufacturing Co.; N.4488, N.4497 and N.4499 known. N.4580: built by Saunders. N.4630, N.4634, N.4636 and N.4637: built by Gosport Aviation Co. N.4838 and N.4839.

Показать полностью

O.Thetford Aircraft of the Royal Air Force since 1918 (Putnam)

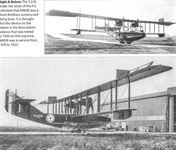

Felixstowe F 2A

The F 2A was the most famous in the series of Felixstowe flying boats that were used on the North Sea patrols, and some of them remained in service with the RAF for a few years after the war. Fifty-three were still on RAF charge on 31 October 1918, and equipped Nos 228, 230, 231, 232, 238, 240, 247, 257 and 267 Squadrons. The last examples in service were those of No 267 Squadron at Kalafrana, Malta, in August 1923, one of whose aircraft, N4490, is illustrated. Powerplant: Two 345hp Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII engines. Span, 95ft 7in; length, 46ft 3in; loaded weight, 10,978lb; max speed, 95mph at 2,000ft; endurance, 6hr; service ceiling, 9,600ft.

Felixstowe F 3

The F 3 provided the link between the F 2A and F 2C flying boats of the First World War and the post-war F 5, possessing a greater wing span than the earlier boats. A total of ninety-six F 3s was on RAF charge in October 1918, equipping Nos 231, 232, 234, 247, 263, 267 and 271 Squadrons. Unlike the F 2As, which survived in service until August 1923, the last F 3s w'ere disposed of by No 267 at Kalafrana, Malta, in May 1921. Powerplant: Two 345hp Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII engines. Span, 102ft; length, 49ft 2in; loaded weight, 12,335lb; max speed, 93mph at 2,000ft; endurance, 6hr; service ceiling, 8,000ft.

Felixstowe F 5

The F 5 was the standard flying-boat in service with the RAF in the years immediately following the Armistice in 1918. It was the last of the line of Felixstowe boats designed by Lt Cdr John Porte which served with such distinction in the First World War, but was itself too late to serve during the war.

The F 5’s design followed fairly closely that of its predecessors, the F 2A, F 2C and F 3. The prototype, N90, passed through its acceptance tests in May 1918 and proved to be over 10mph faster than the F 3, from which it differed in having a new wing structure of greater span (103ft 8in, as against 102ft on the F 3 and 95ft 7 1/2in on the F 2A), a new type of wing section and numerous detail improvements, including rectangular, horn-balanced ailerons on the upper wings. To facilitate manufacture, however, the production version of the F 5 was extensively modified to incorporate F 3 components, with the result that its loaded weight was increased and the final performance figures were somewhat inferior to those of the F 3.

The prototype F 5 was built at the Seaplane Experimental Station at Felixstowe, but production aircraft were contracted out to Short Bros at Rochester, the Phoenix Dynamo Co of Bradford, S E Saunders in the Isle of Wight, Boulton and Paul of Norwich (hulls only) and the Aircraft Manufacturing Co of Hendon.

F 5 flying-boats equipped No 230 Squadron at Felixstowe, moving to Calshot in 1922. Their task was naval co-operation with the Portsmouth submarine flotilla at Portland, and exercises with the Atlantic Fleet. No 230 Squadron was renumbered No 480 Flight at the end of 1922, but it retained its F 5 boats until disbanded in April 1923. In 1921, the RAF had 109 Felixstowe flying-boats on its strength. In July 1919 an F 5 flying-boat, N4044, made a tour of Scandinavia, a flight of 2,450 miles in 27 days. In December 1924 Short Bros produced an F 5, N177, with an all-metal hull, this being the first military flying-boat in the world to depart from the traditional wooden construction.

Since production records invariably group F 3 and F 5 statistics, it is difficult to be sure of the exact number of F 5 boats delivered to the RAF. It seems unlikely to have exceeded by very much the twenty-three examples (N4037-N4049 and N4830-N4839) completed by Short Bros, although some aircraft from the Phoenix and Boulton and Paul contracts (N4184-N4198), Saunders (N4430-N4479) and Airco (N4480-N4579) may have been delivered, if only to go into storage.

TECHNICAL DATA (FELIXSTOWE F. 5)

Description: General reconnaissance flying-boat with a crew of four. Wooden structure with ply and fabric covering.

Manufacturers: See list in accompanying text.

Powerplant: Two 375hp Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII.

Dimensions: Span, 103ft 8in; length, 49ft 3in; height, 18ft 9in; wing area, 1,409sq ft.

Weights: Empty, 9,100lb; loaded, 12,682lb.

Performance: Max speed, 88mph at 2,000ft; climb, 30 min to 6,500ft; endurance, 7hr; service ceiling, 6,800ft.

Armament: One Lewis gun in bows and three amidships. Bomb load of 920lb carried below the wings.

Squadron Allocations: Nos 230 (Felixstowe and Calshot) and 231 (Felixstowe). No 480 Flight (Calshot).

Показать полностью

O.Thetford British Naval Aircraft since 1912 (Putnam)

Felixstowe F.2A

Though it saw action only during the last year of the First World War, the F.2A earned a reputation comparable with that of the Sunderland in the Second World War. By virtue of its great endurance and heavy defensive armament, it bore the brunt of the long-range anti-submarine and anti-Zeppelin patrols over the North Sea in 1918 and figured in innumerable fights with German seaplanes; the exploits of Great Yarmouth's boats were typical, and are related at length in C F Snowden Gamble's classic, The Story of a North Sea Air Station. It established the trend of British flying-boat design for two decades and was a triumphant justification of the pioneer work of John Porte, who had from 1914 devoted himself unceasingly to the development of the flying-boat as a weapon of war.

The F.2A was the first of the Felixstowe boats to be widely used by the RNAS. The first of the series was the F.1 (No.3580), which combined the Porte I type of hull with the wings and tail assembly of a Curtiss H.4. This was an experimental design only and was not put into quantity production. The success of the Porte I hull was such that it was decided to build a larger one on the same principles which could be married to the wings and tail assembly of the Curtiss H.12 Large America. The outcome of this idea was the Felixstowe F.2, the immediate forerunner of the F.2A. The Porte-type hulls offered greater seaworthiness than had been the case with the Curtiss hulls, yet their method of construction was such that they could be produced by firms with no previous boat-building experience. This was an obvious asset at a period of the war when the need for greater numbers of flying-boats for anti-submarine patrol was becoming urgent.

The first F.2A flying-boats were delivered late in 1917, and by March 1918 some 160 had been ordered; by the Armistice just under 100 had been completed, and in the immediate post-war period some aircraft ordered under these contracts were converted on the production line to F.5 flying-boats. The total production of 180 would undoubtedly have been greater if a decision had not been taken by the Admiralty to issue extensive contracts for the F.3, a flying-boat in some respects inferior to the F.2A. As the F.2A had originally been intended for operation from sheltered harbours, it was necessary to make some structural modifications to the hull when its use became more widespread and indiscriminate. Nevertheless, the F.2A stood up well to harsh operational conditions, and such setbacks as it had were due not to lack of seaworthiness, but rather to the inadequacies of the fuel system, for the windmill-driven piston pumps failed all too frequently.

One of the great advantages of the F.2A in view of its considerable range (some boats stayed airborne for as long as 9 1/4 hours by carrying extra petrol in cans) was the provision of dual control; this had not been available on earlier types, such as the H.12. Modifications to the boats to suit the ideas of individual air stations were quite common; one of the most noteworthy was the removal of the cabin for the pilot and second pilot, leaving an open cockpit. This improved both visibility and performance, and from about September 1918 was incorporated in aircraft as they left the works.

F.2As of the Felixstowe air station inherited from the Curtiss H.12s the historic 'Spider's Web' patrol system. This patrol began in April 1917, and was centred on the North Hinder Light Vessel, which was used as a navigation mark. Flying-boats operated within an imaginary octagonal figure, 60 sea-miles across, and followed a pre-arranged pattern which enabled about 4,000 square miles of sea to be searched systematically. One flying-boat could search a quarter of the whole web in about three hours, and stood a good chance of sighting a U-boat on the surface, as submarines had to economise on battery power. Moreover, flying-boats had the advantage over other heavier-than-air anti-submarine aircraft in that they could carry bombs of 230 lb, which could seriously damage a submarine, even if a direct hit were not secured.

The F.2A, despite its five-and-a-half tons, could be thrown about the sky in a 'dog-fight' with enemy seaplanes, and on 4 June 1918 there occurred one of the greatest air battles of the war, waged near the enemy coastline, over three hours' flying time from the RNAS bases at Great Yarmouth and Felixstowe. The formation of flying-boats, led by Capt R Leckie, consisted of four F.2As (N4295 and N4298 from Great Yarmouth and N4302 and N4533 from Felixstowe) and a Curtiss H.12. One F.2A (N4533) was forced down before the engagement, due to the old trouble of a blocked fuel line, but the remaining F.2As fought with a force of 14 enemy seaplanes and shot six of them down. During the action another F.2A (N4302) was forced down with a broken fuel pipe, but a repair was effected, and finally three F.2As returned triumphantly to base having suffered only one casualty. Following this action, in which the danger of being forced down on the sea with fuel-pipe trouble became only too evident, it was decided to paint the hulls of the F.2As in distinctive colours for ready recognition. Great Yarmouth boats were painted to the crews' own liking, and some bizarre schemes resulted; Felixstowe, on the other hand, imposed a standardised scheme of coloured squares and stripes. The scheme of each individual F.2A was charted, and copies were held by all air and naval units operating off the East Coast.

The F.2a was also successful against Zeppelins. The most remarkable of these engagements was on 10 May 1918, when N4291 from Killingholme, flown by Capts T C Pattinson and A H Munday, attacked the Zeppelin L62 at 8,000 ft over the Heligoland minefields and shot it down in flames. Some F.2As, operating as far afield as Heligoland, were towed to the scene of action on lighters behind destroyers. This technique was first employed on 10 March 1918, and was originally part of a scheme to extend the flying-boats' range so as to mount a bombing offensive on enemy naval bases.

One variation of the F.2A was built with the designation F.2C ( 65); it had a modified hull of lighter construction and alterations to the front gun position. Although only one F.2C was produced, it saw active service with the RNAS at Felixstowe. The F.2C, flown by Wg Cdr J C Porte, the famous flying-boat pioneer, shared the credit with two other flying-boats in the same formation for the destruction of a U-boat.

UNITS ALLOCATED

No.228 Squadron (ex-324, 325 and 326 Flights) at Great Yarmouth; Nos.230, 231, 232 and 247 Squadrons (ex-327, 328, 329, 330, 333, 334, 335, 336, 337 and 338 Flights) at Felixstowe; No.238 Squadron (ex-347, 348 and 349 Flights) at Cattewater; No.240 Squadron (ex-345, 346, 410 and 411 Flights) at Calshot; No.257 Squadron (ex-318 and 319 Flights) at Dundee and No.267 Squadron (ex-360, 361, 362 and 363 Flights) at Kalafrana. Also Nos.320, 321 and 322 Flights at Killingholme.

TECHNICAL DATA (F.2A)

Description: Fighting and reconnaissance flying-boat with a crew of four. Wooden structure, with wood and fabric covering.

Manufacturers: Aircraft Manufacturing Co Ltd, Hendon (with hulls from May, Harden & May, Southampton); S E Saunders Ltd, Isle of Wight; Norman Thompson Flight Co, Bognor Regis. Serial numbers allocated were N4080 to N4099, N4280 to N4309, N4430 to N4504, N4510 to N4519, N4530 to N4554 and N4560 to N4568, but some aircraft were eventually delivered as F.5s.

Power Plant: Two 345 hp Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII

Dimensions: Span, 95 ft 7 1/2 in. Length, 46 ft 3 in. Height, 17 ft 6 in. Wing area, 1,133 sq ft.

Weights: Empty, 7,549 lb. Loaded, 10,978 lb.

Performance: Maximum speed, 95 1/2 mph at 2,000 ft; 80Y2 mph at 10,000 ft. Climb, 3 min 50 sec to 2,000 ft; 39 min 30 sec to 10,000 ft. Endurance (normal) 6 hr. Service ceiling, 9,600 ft.

Armament: From four to seven free-mounted Lewis machine-guns (in bows, waist positions, rear cockpit and above pilot's cockpit) and two 230 lb bombs mounted in racks below the bottom wings.

Felixstowe F.3

It is generally conceded that the F.3, though the subject of large-scale production contracts (263 ordered and 176 delivered), was in many respects the inferior of the F.2A. Admittedly it could carry twice as many bombs, but it was slower and less manoeuvrable, and hence lacked the qualities which had enabled the F.2A to take on German seaplane fighters in air combat. On the other hand, it was capable of a greater range. It first entered service in February 1918 and was not declared obsolete until September 1921.

The prototype F.3 (N64) differed from production aircraft in having twin 320 hp Sunbeam Cossack engines instead of Rolls-Royce Eagles. It is recorded that it served operationally during 1917-18 with the Royal Naval air station at Felixstowe. It made its maiden flight in February 1917 and was finally written off in May 1918.

The F.3 operated extensively in the Mediterranean, and in October 1918 accompanied the Naval attack on Durazzo in Albania. The operational requirements for anti-submarine flying-boats in the Mediterranean area were, in fact, so pressing that manufacture of F.3 flying-boats was undertaken locally in Malta dockyards. Twenty-three were built in Malta between November 1917 and the Armistice.

UNITS ALLOCATED

No.234 Squadron (ex-350, 351, 352 and 353 Flights) at Tresco; No.238 Squadron (ex-347, 348 and 349 Flights) at Cattewater; No.263 Squadron (ex-359, 435, 436 and 441 Flights) at Otranto; No.267 Squadron (ex-360, 361, 362 and 363 Flights) at Kalafrana and No.271 Squadron (ex-357, 350, 359 and 367 Flights) at Taranto. Also No.300 Flight at Catforth, Nos.306 and 307 Flights at Houton and Nos.309, 31 () and 311 Flights at Stemless.

TECHNICAL DATA (FELlXSTOWE F3)

Description: Anti-submarine patrol flying-boat with a crew of four. Wooden structure, with wood and fabric covering.

Manufacturers: Short Bros Ltd, Rochester (N4000 to N4036); Dick, Kerr & Co Ltd, Preston (N4100 to N4117 and N4230 to N4279); Phoenix Dynamo Manufacturing Co Ltd, Bradford (N4160 to N4176 and N4400 to N4429); Malta Dockyard (N43 10 to N4321 and 4360 to 4370).

Power Plant: Two 345 hp Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII.

Dimensions: Span, 102 ft. Length, 49 ft 2 in. Height, 18 ft 8 in. Wing area, 1,432 sq ft.

Weights: Empty, 7,958 lb. Loaded (normal), 12,235 lb.

Performance: Maximum speed, 91 mph at 2,000 ft; 86 mph at 6,500 ft. Climb, 5 1/4 min to 2,000 ft; 24 min to 6,500 ft. Endurance, 6 hr. Service ceiling, 8,000 ft.

Armament: Four Lewis machine-guns on free mountings and four 230 lb bombs on racks beneath the wings.

Показать полностью

H.King Armament of British Aircraft (Putnam)

F.2A. Extraordinary technical and military qualities were possessed by this most famous of the 'Felixstowe boats' and only in comparatively recent years have these qualities received full recognition. Dating from 1917, the F.2A had an armament of Lewis guns concentrated in the forward part of the hull and at the waist. Typically, there was a Scarff ring-mounting in the bow for one or twin-yoked guns. This was sometimes, perhaps generally, of the familiar No.2 pattern, though there is some evidence to suggest that in a few instances a type of Scarff ring-mounting wherein the quadrant moved with the gun-carrying 'bow', and was invisible when the bow was at its lowest position, may have been fitted. This type of mounting, which will be mentioned again in connection with the Handley Page O/400 and which will be shown in official drawings in Volume 2, was one of several mountings designed by F. W. Scarff. Sometimes the F.2A had a pillar-mounted Lewis gun on top of the pilot's cockpit canopy; there was a single Lewis gun at each waist hatch behind the wings; and atop the hull in this same area was another gun, or sometimes twin-yoked guns. In some instances at least the waist guns appear to have had the Scarff compensating sight. The pillar carrying each gun was mounted at the outer ends of two superimposed struts, braced to an inboard member and allowing the assembly to be swung outboard. There was under-wing provision for two 230-lb bombs just outboard of the attachments of the wing hull bracing struts, the carrier being staved to the wing inboard. One experimental F.2A had two 'howdah' or 'fighting-top' gun-nacelles, each with twin-yoked Lewis guns on a Scarff ring-mounting at its forward end, built on to the upper wing. These guns further broadened an already commanding field of fire; for, compared with the H.12 type of boat, the F.2 was well endowed in this regard, having a 'cocked-up' rear hull which permitted the midships beam guns to be swung outboard on their pillars so that their lines of fire could meet little more than twenty feet astern.

For comparison with the Sunderland, and with flying-boats between, this contemporary description of accommodation and battle stations is offered:

'A gunner is located immediately below the fore gun-ring, and a table for his use extends from his seat to the nose of the hull. Underneath the table is an ammunition box and trays... Abaft is the station for the pilot and assistant pilot... Their seats are well upholstered with kapok cushions, which act as lifebuoys if required. The assistant-pilot's seat is made to hinge, so that a clear passage may be obtained for walking fore and aft. A few feet behind the pilot is the wireless cabinet, with operator's seat, while at the port side of this a ration box is fitted. The engineer's accommodation is situated aft, with a ladder giving access to the top deck. Further aft is the second gun ring, with an adjustable platform to allow a gunner to have a good range of heights...'

In a photograph showing an F.2A built by the Aircraft Manufacturing Co. the sights on the beam gun are mounted on an arm on the gun's left side, with an eye-piece for the rear component. The forward gun, on its Scarff No.2 ring-mounting, does not have Norman vane-type sights, but apparently a form of ring-and-bead sight mounted laterally on the gun's axis.

F.2C. One experimental installation on this F.2A development was a compressed-air bomb-release system, eliminating the usual Bowden cable, but introducing its own problems of complexity and reliability. Only one F.2C was built. Flown by Wg Cdr J. C. Porte, to whom the greatest honour is due for developing the F-boats, this shared with two other machines of the same formation in the destruction of a submarine.

F.3 and F.5. Emphasis was placed, in the arming of these two flying-boats (1917 and 1918 respectively), upon anti-submarine operations, and the bomb load was accordingly increased to four 230-lb bombs. Machine-gun deployment was much as on the F.2 boats, the standard arrangement, as shown in an official publication on the F.5, being single Lewis guns at bow, dorsal and beam positions. No installation of a Davis gun or other heavy ordnance is known to have been made on a British F.3 or F.5, although interest in such armament was very much alive at this period and the American-built F.5 had an installation of the Davis gun. One Lion-engined F.5 for Japan is said to have had a revised bow cockpit for a '1-pounder shell-firing gun'.

F.5 (Metal Hull). Late in 1924 the upperworks of a Felixstowe F.5 flying-boat were fitted to an experimental metal hull of Short construction. Notwithstanding its experimental nature, this hull had two Scarff ring-mountings for Lewis guns. One was in the bow and the second in line with the trailing edges of the wings.

Показать полностью

C.Barnes Short Aircraft since 1900 (Putnam)

The Short N.3 Cromarty

Although Oswald Short had been a member of the firm from its very first venture into balloon manufacture, some nine years before Horace Short joined his brothers, he was always regarded by Horace as too young and inexperienced to be allowed a free hand in aeroplane design; even up to the time of Eustace Short’s death in 1932, Oswald was always referred to by his elder brother as ‘The Kid’. This did not prevent him from making his own very competent and continuous contribution to general progress, and in fact sprung floats and pneumatic flotation bags were both his invention, although nearly all patents for new inventions were taken out in the joint names of all three brothers. After war broke out in 1914 it seems that Oswald tried to gain a little more autonomy in design matters, rather against Horace’s wishes, and on the famous occasion in 1916 when Horace at last acceded to John Parker’s request to be allowed to fly, the conditions he stated were: ‘You don’t interfere with the design, and you don’t take any notice of what the bloody Kid says.’