Книги

Centennial Perspective

C.Owers

The Fighting America Flying Boats of WWI Vol.1

346

C.Owers - The Fighting America Flying Boats of WWI Vol.1 /Centennial Perspective/ (22)

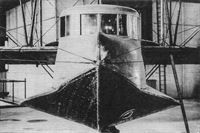

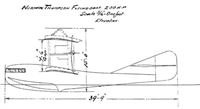

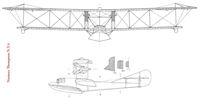

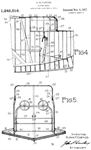

The Admiralty Air Department A.D. flying boat used the Linton Hope method of construction and represented the future type of wooden construction that was to be used on the first Supermarine Southampton flying boats post-war. Supermarine received a contract for A.D. boats, the hulls being delivered to this firm where the wings, etc., were added. The prototype 1412 is illustrated here. Supermarine sold versions of the A.D. Boat as their Channel seaplane post-war.

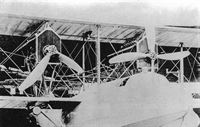

9800 with Bristol Scout 3028 mounted over the top wing. Porte thought that this method of attacking Zeppelins had great promise and it was "a great pity in the light of after experience that this scheme was not used in actual service."

DH.4 A7459 was one of two modified for a reconnaissance of the Kiel Canal. This mission was never flown and A7459 attacked Zeppelin L.44 on 4 Sept. 1917 in company with H-12 8666. A7459 was damaged and forced to ditch, the crew of F/Lt. A.H.H. Gilligan and L/Lt. G. Trewin being rescued by H-12 8666.

Flown by W/Cdr. Charles Rumney Samson and AM Radcliffe, DH.4 A7830 attacked a U-Boat with two 65 pound bombs on 21 March 1918. A7830 survived into the 1920s.

This De Havilland D.H.4, A7830, is readily recognised by its striking black and white colour scheme. Allocated to Great Yarmouth for special service in December 1917, it attacked a U-Boat on 21 March 1918, dropping two 65-lb bombs. The pilot on this occasion was the redoubtable Wing Cmdr Charles Rumney Samson with AM Radcliffe in the rear cockpit. This biplane survived into the 1920s.There is a Fairey Hamble Baby and what appears to be a standard Sopwith Baby sharing the hard stand with A7830. A twin-engine flying boat is in the far background. C.F. Snowden Gamble considered the D.H.4 one of the most successful two-seaters issued to Great Yarmouth in 1917.

De Havilland D.H.4 A7830 shows its unusual camouflage scheme including camouflage on the lower surfaces.

De Havilland D.H.4 A7457 and A7459 were modified for a long range reconnaissance of the Kiel Canal. When this did not eventuate A7459 was chosen as an anti-Zeppelin fighter. Still bearing its fawn and blue camouflage A7459 is illustrated here in the configuration it is thought to have been in when it attacked Zeppelin L.44. Twin Lewis guns are mounted above the centre section in addition to the pilot's synchronised Vickers gun, and the gunner also had twin Lewis guns on a ring mounting. Flt Lt A.H.H. Gilligan (pilot) with Flt Lt G.S.Trewin (gunner) are occupying the cockpits. The light coloured rectangle under the cockpit is believed to bear the aircraft's nickname "ALLO LEDE BIRD." The unusual cockades adopted for this colour scheme are noteworthy as is the application of the camouflage to the lower surfaces.

This De Havilland D.H.4, A7830, is readily recognised by its striking black and white colour scheme. Allocated to Great Yarmouth for special service in December 1917, it attacked a U-Boat on 21 March 1918, dropping two 65-lb bombs. The pilot on this occasion was the redoubtable Wing Cmdr Charles Rumney Samson with AM Radcliffe in the rear cockpit. This biplane survived into the 1920s.There is a Fairey Hamble Baby and what appears to be a standard Sopwith Baby sharing the hard stand with A7830. A twin-engine flying boat is in the far background. C.F. Snowden Gamble considered the D.H.4 one of the most successful two-seaters issued to Great Yarmouth in 1917.

2. Development of the Felixstowe Flying Boats

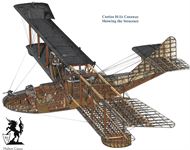

The Felixstowe flying boats were developed at the RNAS Seaplane Experimental Station, Felixstowe by John Cyril Porte from the Curtiss flying boats into the superb F.2A boats that carried the anti-submarine war into the North Sea. Despite their many shortcomings, the Felixstowe boats were practical machines that served successfully in the war and for a goodly time afterwards in the UK and the USA. There arose two schools of thought on the construction of flying boats in the UK, one that supported the Porte method of construction and the other that supported the ideas of Linton Hope. A series of lectures with question and answer sessions given to the Royal Aeronautical Society by exponents of both methods of construction have left a rich vein of historical material, with a deep undercurrent of a desire to discredit John Porte, that has formed the basis for this chapter.

As noted in Chapter 1, Porte had been invited to the USA to be the pilot of the Curtiss-Wannamaker America flying boat that was to fly the Atlantic in response to the Daily Mail’s offer of a prize for the first crossing by an aircraft. With the outbreak of war, the flight was postponed and Porte returned to England where he volunteered for the RNAS. He was appointed Squadron Commander at Hendon.

Directly I got back I saw Commander Suter (sic) the head of the Air Department.

I saw him the next morning after I arrived and I also informed him that there were these two flying boats which we had built in America to fly the Atlantic which were available and could be bought by the Admiralty if they desired to buy them....

The boats were delivered to Felixstowe and Porte, who was at the time in charge of Hendon, was to test the first one. Commander Seuter came down and after a flight with Porte reported to the First Sea Lord, Winston Churchill, that he considered them excellent and Churchill then ordered that 12 be contracted for at once.

In order to understand the experiments and development of the Felixstowe F boats, it is first necessary to understand the difference between a landplanes and a flying boat’s requirements. The following has been taken from the lecture given by Major J.D. Rennie, who had been the Chief Technical Officer while Porte was in command of RNAS Station Felixstowe, to the Royal Aeronautical Society and published in their Journal in 1923.

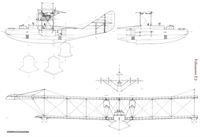

The usual biplane configuration of a flying boat differs from that of a large aeroplane in that the span of the upper wing is considerably longer than the lower. This is not intended primarily to obtain greater aerodynamic efficiency owing to the absence of biplane interference on the extensions, but to reduce the wing area in proximity to the surface of the water, thus minimising the risk of damage to the lower wing in a rough sea. For the same reason ailerons are not fitted to the lower plane. To allow for adequate lateral control the ailerons should be positioned as far outboard as possible.

The position of the wing tip floats should be as close to the hull as possible so that less shock is transmitted to the wing structure on takeoff, landing and rolling, one wing down. The result of these considerations is the wing arrangement described above.

“It is said of the “F” boats that the use of stabilisers (antiskid fins) on the top plane is a very inefficient aid to lateral stability. They were never really intended as such,” the top plane extensions requiring bracing to withstand downloads that are applied at high speed flight or inertial load during a bad landing. The rectangular cross-braced kingposts were considered to be better than the triangular type, and by fairing it in, it also acted as a stabiliser.

“In the F boats, which had twin tractor airscrews, about three-quarters of the tailplane was in the slipstream and seemed fairly satisfactory, but on trial the boat was decidedly tail heavy, as were all of the F boats. This was partly due to the fact that when carrying full military load the CG was further back than was originally intended. With pusher propellers the conditions are simpler but they are very liable for damage from parts that may work loose, or even tools that have been left through carelessness.

“With regard to fin and rudders, these are of relatively large area due to the long forebody of the flying boat. The rudder area of the F boats was barely sufficient for control with one engine out.

“As with the aeroplane, controllability at low speeds is of importance, but probably less so as generally the extent of a landing ground is not so restricted. Also once alighted the boat pulls up quickly due to the large hull resistance. Thus it is possible to glide at a comparatively high speed until close to the water before flattening out and alighting.”

The modifications carried out on and the new type hulls evolved at Felixstowe were arrived at from full size experimentation as model hull testing was not available at the time with the exception of the Fury triplane. From 1915 experiments with full sized machines were carried out to correlate the results of tank tests at the National Physical Laboratory’s William Froude tank. These were not successful due to the problems of collecting data. Visits were made to seaplane stations for the purpose of studying the behaviour of the machines in disturbed water when getting off and alighting. The following visits took place:

July 1916 at Felixstowe when the “America” flying boat and Short seaplanes were flown. The machine was described as the 4,000 lb America type with propellers rotating in the same direction.

Reputed getting of speed 38 knots, speed in flight 48 knots. The machine rose and settled three times. The pilot held the tail down on the water and bow up until 30 knots was reached then decreased the angle so that the tail came off, after which the flying speed was quickly reached. To lift the tail earlier than 30 knots would mean throwing up a lot of water at the fore end and it could not be lifted earlier than 18 knots. The machine took a little time to reach the speed of 30 knots, but when the tail was lifted accelerated rapidly. This agrees with tank results which show that the drag of the tail adds very largely to the resistance. The landing was gentle on each occasion, once on the tail tip and twice on the step. The machine was run up once, for a few seconds, at a speed slightly over 30 knots tail out, without control. The air balance was fairly good and the machine moved but very slowly from its longitudinal trim.

September 1916 at Calshot where the F.B.A. flying boat was flown.

August 1916 to Southampton to view the A.D. flying boat.

October 1916 at Felixstowe saw some data obtained on a Porte boat.

A “Porte” boat with chine running continuous from stem to stem, front step a little abaft the centre of gravity and two other steps at the rear and under the chine. On practically smooth water and with no wind, both with the elevator full up and down, failed to unstick the tail. With no observer, less petrol, and a little wind, this machine got off, but it was too far away for its behaviour to be noted.

“The great drawback in all these cases was the absence of any reliable scientific data and the contradictory character of the opinions expressed by those concerned in the running of the machines. It was in no case possible to get reliable speeds or inclinations of the machine. The visits served, however, to show the general character of “porpoising” and to some extent the means adopted by pilots in evading this phenomenon.” It was hoped that by using models in the Tank it would be possible to save a certain amount of experimental work at the stations with greater ease and considerable savings. Until the results of tank testing and full sized boats could be established the only way to determine the best type of hull was by full scale experimentation and this was how Porte approached the problem.

At rest the total weight of a flying boat is supported by hull buoyancy, and lateral stability by means of the wing tip floats. Owing to the high centre of thrust and low water and air resistance up to speeds of say 10 knots, the throttle is opened slowly, and elevators held up to prevent trimming by the bow. As speed increases, elevators are put into neutral when the hull should trim back of its own accord. From this speed the load that is supported by the buoyancy is gradually transferred to the hydrodynamic water forces acting on the planing surface, the fore body rising first, followed by the tail, which may be assisted by putting the elevators down slightly until the boat is planning cleanly. Water resistance will increase steadily, however if the hull is designed correctly, it will continue to drop owing to the improved working to the step and to the increasing percentage of the load taken by the wings. The speed at which the water resistance reaches a maximum is generally known as the “hump” speed. Generally a boat that gets over the hump has power for flight. From this speed or generally a little above, a sharp pull up on the elevators will make a clean break away from the water, the boat becoming entirely airborne. The elevators are then depressed before trimming to gain height.

The hull should be designed so that it is able to be trimmed back to such an attitude that the angle of incidence of the wings is that corresponding to the lowest safe speed, usually a few knots above stalling speed, without excessive elevator movements and increase in hull resistance. Serious accidents due to taking off in a stalled condition are rare as flying boats are generally well above the lowest flying speed providing sea conditions are suitable.

Up to about the “hump” speed lateral stability is obtained by use of the wing tip floats and such aileron control as is available. After the “hump” speed the boat trims naturally onto an even keel due to the stable hydrodynamic forced acting on the planning surface. As speed increases the aileron control becomes more effective.

Thus a flying boat hull must

(a) Avoid diving at low speeds.

(b) Have seaworthiness.

(c) Have hydroplaning efficiency and landing with minimum shock.

(d) Have stability at high speeds on the water.

(e) Have the ability to trim fore and aft to enable take offs and alightings.

As noted in Chapter 1 the Admiralty bought the two Curtiss America flying boats that had been built for the proposed pre-war trans-Atlantic flight. These boats were delivered to Felixstowe in October 1914 where they underwent trials. The boats proved promising and, as previously recorded, Churchill, First Sea Lord, ordered a dozen as the Curtiss H.4 with more powerful engines.

Porte has recorded that he wanted to build the boats in the UK and so an order for eight (1228-1235) was given to the Aircraft Manufacturing Company. These were designated as H-4 America flying boats. Four were ordered at the same time from the Curtiss Aeroplane & Motor Co Inc (1236-1239). As noted further on it appears that Curtiss provided the AMC with details of the design. The four Curtiss boats arrived long before the ones to be made in England were completed. These latter boats were built under Porte’s supervision at Hendon. The hulls were built by Saunders at Cowes. Later orders followed with 50 H-4 boats being supplied by Curtiss under Contract No. C.P.01533/15.

Porte had flown the H.4 and knew of their limitations and began the task of modifying the boats to get one that would be usable in the North Sea. “At the end of January 1915 I was appointed to take charge of Felixstowe Air Station and in May of that Year I left Hendon altogether and took over Felixstowe completely and have remained there practically continuously” since then. When he went to Felixstowe there were then only “50 men and three small sheds; there are now 1,000 men and an enormous number of sheds... I have built the whole thing up”

Felixstowe’s Experiments

When the first of the Curtiss flying boats arrived in the UK, “Commander Porte was specifically instructed by the Director of the Air Department Admiralty to experiment with and improve the said boats.”

“When the first experiments were taken in hand no engines of high power were available. Consequently, seaplane designers were faced with the problem of “Getting off’ as the chief difficulty. For this reason the early experiments were made with the main object of developing hydroplaning efficiency and the question of simplicity of structure and shockless landing were neglected.”

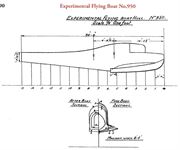

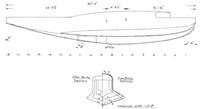

The first hull tested was a modified Curtiss America flying boat serial 950, one of the original America boats purchased by the Admiralty. This hull weighed light 3,100 lbs and, on certain occasions, 4,500 lbs was taken off the water. The original hull was 30 feet long, and was modified by the addition of a wide longitudinal projecting fin forward, ending at the single step that was under the CG of the machine. The fore and aft angle between the underside of the tail and planning surface of the ship was 10°. The available engines gave about 160-hp.

At high speeds all single step hulls balance on the step and trim depends on the angle of the tail portion, which in order to avoid water drag, should be kept up while accelerating the boat. The original tail plane was lifting and hence excellent from this point of view, and as much load as could be flown with could be taken off the water. In order to improve stability in flight the tailplane was made negative. In smooth water there did not seem to be any appreciable loss in hydroplaning efficiency, but in rough weather, owing to the lack of buoyancy forward, this hull was very wet. The nose of the hull tended to dig in and water was thrown up over the engines to such an extent as to cause the engines to misfire, thus indirectly making it difficult to get off.

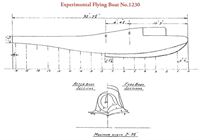

A new hull was built for the Aircraft Manufacturing Company by S.E. Saunders Ltd in which the fins were narrower and carried further aft as the step was under the rear spar. The straight lines of the previous form were replaced by curves, the planning bottom being slightly hollow. The underside of the tail was rounded and construction was lighter. This machine was given the serial 1230. This hull proved inferior to that of 950, largely due to the rounded tail section that was not only a less efficient hydroplaning surface but increased suction making it very difficult to lift out of the water in calm weather. This hull was 32 ft in in length. While there was a savings of 300 lbs in weight over previous hulls due to its different construction, it was considerably weaker and “did not outlast many landings.” The Saunders hulls were covered in the patented Consuta stranded copper wire sewn plywood and heavily varnished.

The next hull was made for Curtiss H.4 serial 3545 and was similar to 950 but the tail portion was 2 feet longer, and the fins were wider. The fore and aft angle was reduced from 10° to 7°. “Consequently the machine had to be held at a finer angle of incidence when planning to avoid drag due to (the) submersion of the tail, which caused the getting off speed to be higher.” In smooth water the hull gave a better planning efficiency than the original hull. While the total weight of 4,500 lbs was taken off the water by this hull, the same load as for the original hull, this hull was 300 lbs heavier than the original one.

“The main conclusion arrived at from these experiments were that, from the point of view of planning efficiency and low getting off speed, a large fore and aft angle was essential and a flat bottomed tail portion was advantageous. But it was also evident that much remained to be done in the direction of lighter construction and of general seaworthiness.” From the experiments with these hulls it was learnt that from the point of view of the ability to hydroplane and low take off speed, the tail portion should be flat bottomed to reduce suction, and the fore and aft angle should be large to obtain the necessary trim.

Next it was decided to tackle the problem of easy landing conditions, and increased strength of the hull without sacrificing planning efficiency. “This series ended with the production of ‘Porte I’, which machine showed marked improvement in these particulars.”

In the early days all landing breakages of flying boat hulls occurred at the step, a structural weak point, indeed a Small America had broken in half at the step. The need to reconsider the best form of hull was evident. The next experiment was to find if a step was necessary at all. A complete new steeper V bottom was built on 3545 having no step but with a steeper fore and aft angle of nearly 20° and with the tail very much swept up with the keel line following a smooth curve. The fins that extended for % of the length were extended back to meet the hull instead of ending off square under the wings as before. The result was to decrease head resistance by making the whole hull more streamline and also to make a stronger hull. This machine was given the serial 3569 and was known as the Transitional boat, as it was the link between the America boats, all those boats that had their fins cut off short at the step, and the Felixstowe group with their long fins and steep V bottom. This hull was 32 ft 2 in long. With the available engines (presumably of nominal 200-hp) there was not enough power to take off. A step was added 5 feet behind the CG and the hull was then capable of getting off but with only 4,200 lbs total load as against 4,500 lbs with the earlier hulls. Although “Getting Off” was not as good as the America boats, landing was exceptionally easy owing to the large fore and aft angle. The deeper V resulted in little or no landing shock with a normal or nearly stalled landing. “This latter method of landing is a very severe test because, immediately the tail portion touches the water, the heavy water drag pulls the machine down very suddenly.” Owing to the step being so far aft of the CG, the hull ran at a small angle and required a large moment to trim the machine back for takeoff. To relieve the pilot of this load the step was shifted 3 feet forward.

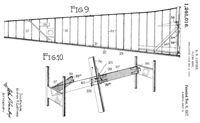

The next experiment was the building of “Porte I” an entirely new single step hull built at Felixstowe to carry the same Curtiss superstructure as before. The bows were kept fuller and given a flare or concave entry. Porte used an entirely different form of construction for the next hull with longerons and spacers with wire bracing as used in the construction of landplanes, rather than the boat builder methods used for the Curtiss hulls. The America hulls depended on their tubular shape and stiffness of their skins for strength. They had reinforcement from the keel and, in the larger boats, from bulkheads, and some centre line wiring in the tail, but the rounded form and continuous planking was essential to the structure. Porte’s method gave the requisite strength for a low weight. Originally a single step, located below the rear spar, was fitted. The hull was 36 feet overall in length, three feet longer in the nose and two feet in the tail than the third type of hull.12 The fore and aft angle was 18° and the tailplane was raised 7 inches more than that of the fourth hull, and the line of the keel was kept higher. Fins were carried well at of the step and swept back into the hull. The V-bottom was similar to 3569 and the bows were fuller with a distinct flair on the first three feet.

With this hull the tail portion was liable to catch the water and drag held the speed down to below take off speed. To overcome this, a second step was added 7 1/2 feet from the stern. This modification meant that it was now possible to takeoff but with less load than the earlier hulls. A third step was added intermediate between the main and aft steps. This allowed the load to be brought back to very nearly that of the earlier hulls. This hull was far superior to any hull previously tested at Felixstowe. Owing to the improved form of bow, the cockpits were perfectly dry. Landing shocks were reduced to a minimum, and behaviour generally in alighting and getting off was excellent. Seaworthiness was far superior to the preceding hulls. This hull was named Porte I and the aircraft was subsequently designated the F.1.

3580 had a long and varied career and at the Felixstowe Seaplane School by December 1917, and was flown for many hours by students who did their worse to her. When dismantled for overhaul no serious defects were found other than corrosion of various metal fittings. It survived until January 1919.

In 1918 she was re-engined with two 150-hp Hispano-Suiza engines and subject to further testing. With no step she just staggered into the air in a stalled condition showing that such a thing was possible with a low enough loading. With a single step she was not as efficient as with two steps, thus seeming to confirm the results of the Transitional Boat.

<...>

The Felixstowe flying boats were developed at the RNAS Seaplane Experimental Station, Felixstowe by John Cyril Porte from the Curtiss flying boats into the superb F.2A boats that carried the anti-submarine war into the North Sea. Despite their many shortcomings, the Felixstowe boats were practical machines that served successfully in the war and for a goodly time afterwards in the UK and the USA. There arose two schools of thought on the construction of flying boats in the UK, one that supported the Porte method of construction and the other that supported the ideas of Linton Hope. A series of lectures with question and answer sessions given to the Royal Aeronautical Society by exponents of both methods of construction have left a rich vein of historical material, with a deep undercurrent of a desire to discredit John Porte, that has formed the basis for this chapter.

As noted in Chapter 1, Porte had been invited to the USA to be the pilot of the Curtiss-Wannamaker America flying boat that was to fly the Atlantic in response to the Daily Mail’s offer of a prize for the first crossing by an aircraft. With the outbreak of war, the flight was postponed and Porte returned to England where he volunteered for the RNAS. He was appointed Squadron Commander at Hendon.

Directly I got back I saw Commander Suter (sic) the head of the Air Department.

I saw him the next morning after I arrived and I also informed him that there were these two flying boats which we had built in America to fly the Atlantic which were available and could be bought by the Admiralty if they desired to buy them....

The boats were delivered to Felixstowe and Porte, who was at the time in charge of Hendon, was to test the first one. Commander Seuter came down and after a flight with Porte reported to the First Sea Lord, Winston Churchill, that he considered them excellent and Churchill then ordered that 12 be contracted for at once.

In order to understand the experiments and development of the Felixstowe F boats, it is first necessary to understand the difference between a landplanes and a flying boat’s requirements. The following has been taken from the lecture given by Major J.D. Rennie, who had been the Chief Technical Officer while Porte was in command of RNAS Station Felixstowe, to the Royal Aeronautical Society and published in their Journal in 1923.

The usual biplane configuration of a flying boat differs from that of a large aeroplane in that the span of the upper wing is considerably longer than the lower. This is not intended primarily to obtain greater aerodynamic efficiency owing to the absence of biplane interference on the extensions, but to reduce the wing area in proximity to the surface of the water, thus minimising the risk of damage to the lower wing in a rough sea. For the same reason ailerons are not fitted to the lower plane. To allow for adequate lateral control the ailerons should be positioned as far outboard as possible.

The position of the wing tip floats should be as close to the hull as possible so that less shock is transmitted to the wing structure on takeoff, landing and rolling, one wing down. The result of these considerations is the wing arrangement described above.

“It is said of the “F” boats that the use of stabilisers (antiskid fins) on the top plane is a very inefficient aid to lateral stability. They were never really intended as such,” the top plane extensions requiring bracing to withstand downloads that are applied at high speed flight or inertial load during a bad landing. The rectangular cross-braced kingposts were considered to be better than the triangular type, and by fairing it in, it also acted as a stabiliser.

“In the F boats, which had twin tractor airscrews, about three-quarters of the tailplane was in the slipstream and seemed fairly satisfactory, but on trial the boat was decidedly tail heavy, as were all of the F boats. This was partly due to the fact that when carrying full military load the CG was further back than was originally intended. With pusher propellers the conditions are simpler but they are very liable for damage from parts that may work loose, or even tools that have been left through carelessness.

“With regard to fin and rudders, these are of relatively large area due to the long forebody of the flying boat. The rudder area of the F boats was barely sufficient for control with one engine out.

“As with the aeroplane, controllability at low speeds is of importance, but probably less so as generally the extent of a landing ground is not so restricted. Also once alighted the boat pulls up quickly due to the large hull resistance. Thus it is possible to glide at a comparatively high speed until close to the water before flattening out and alighting.”

The modifications carried out on and the new type hulls evolved at Felixstowe were arrived at from full size experimentation as model hull testing was not available at the time with the exception of the Fury triplane. From 1915 experiments with full sized machines were carried out to correlate the results of tank tests at the National Physical Laboratory’s William Froude tank. These were not successful due to the problems of collecting data. Visits were made to seaplane stations for the purpose of studying the behaviour of the machines in disturbed water when getting off and alighting. The following visits took place:

July 1916 at Felixstowe when the “America” flying boat and Short seaplanes were flown. The machine was described as the 4,000 lb America type with propellers rotating in the same direction.

Reputed getting of speed 38 knots, speed in flight 48 knots. The machine rose and settled three times. The pilot held the tail down on the water and bow up until 30 knots was reached then decreased the angle so that the tail came off, after which the flying speed was quickly reached. To lift the tail earlier than 30 knots would mean throwing up a lot of water at the fore end and it could not be lifted earlier than 18 knots. The machine took a little time to reach the speed of 30 knots, but when the tail was lifted accelerated rapidly. This agrees with tank results which show that the drag of the tail adds very largely to the resistance. The landing was gentle on each occasion, once on the tail tip and twice on the step. The machine was run up once, for a few seconds, at a speed slightly over 30 knots tail out, without control. The air balance was fairly good and the machine moved but very slowly from its longitudinal trim.

September 1916 at Calshot where the F.B.A. flying boat was flown.

August 1916 to Southampton to view the A.D. flying boat.

October 1916 at Felixstowe saw some data obtained on a Porte boat.

A “Porte” boat with chine running continuous from stem to stem, front step a little abaft the centre of gravity and two other steps at the rear and under the chine. On practically smooth water and with no wind, both with the elevator full up and down, failed to unstick the tail. With no observer, less petrol, and a little wind, this machine got off, but it was too far away for its behaviour to be noted.

“The great drawback in all these cases was the absence of any reliable scientific data and the contradictory character of the opinions expressed by those concerned in the running of the machines. It was in no case possible to get reliable speeds or inclinations of the machine. The visits served, however, to show the general character of “porpoising” and to some extent the means adopted by pilots in evading this phenomenon.” It was hoped that by using models in the Tank it would be possible to save a certain amount of experimental work at the stations with greater ease and considerable savings. Until the results of tank testing and full sized boats could be established the only way to determine the best type of hull was by full scale experimentation and this was how Porte approached the problem.

At rest the total weight of a flying boat is supported by hull buoyancy, and lateral stability by means of the wing tip floats. Owing to the high centre of thrust and low water and air resistance up to speeds of say 10 knots, the throttle is opened slowly, and elevators held up to prevent trimming by the bow. As speed increases, elevators are put into neutral when the hull should trim back of its own accord. From this speed the load that is supported by the buoyancy is gradually transferred to the hydrodynamic water forces acting on the planing surface, the fore body rising first, followed by the tail, which may be assisted by putting the elevators down slightly until the boat is planning cleanly. Water resistance will increase steadily, however if the hull is designed correctly, it will continue to drop owing to the improved working to the step and to the increasing percentage of the load taken by the wings. The speed at which the water resistance reaches a maximum is generally known as the “hump” speed. Generally a boat that gets over the hump has power for flight. From this speed or generally a little above, a sharp pull up on the elevators will make a clean break away from the water, the boat becoming entirely airborne. The elevators are then depressed before trimming to gain height.

The hull should be designed so that it is able to be trimmed back to such an attitude that the angle of incidence of the wings is that corresponding to the lowest safe speed, usually a few knots above stalling speed, without excessive elevator movements and increase in hull resistance. Serious accidents due to taking off in a stalled condition are rare as flying boats are generally well above the lowest flying speed providing sea conditions are suitable.

Up to about the “hump” speed lateral stability is obtained by use of the wing tip floats and such aileron control as is available. After the “hump” speed the boat trims naturally onto an even keel due to the stable hydrodynamic forced acting on the planning surface. As speed increases the aileron control becomes more effective.

Thus a flying boat hull must

(a) Avoid diving at low speeds.

(b) Have seaworthiness.

(c) Have hydroplaning efficiency and landing with minimum shock.

(d) Have stability at high speeds on the water.

(e) Have the ability to trim fore and aft to enable take offs and alightings.

As noted in Chapter 1 the Admiralty bought the two Curtiss America flying boats that had been built for the proposed pre-war trans-Atlantic flight. These boats were delivered to Felixstowe in October 1914 where they underwent trials. The boats proved promising and, as previously recorded, Churchill, First Sea Lord, ordered a dozen as the Curtiss H.4 with more powerful engines.

Porte has recorded that he wanted to build the boats in the UK and so an order for eight (1228-1235) was given to the Aircraft Manufacturing Company. These were designated as H-4 America flying boats. Four were ordered at the same time from the Curtiss Aeroplane & Motor Co Inc (1236-1239). As noted further on it appears that Curtiss provided the AMC with details of the design. The four Curtiss boats arrived long before the ones to be made in England were completed. These latter boats were built under Porte’s supervision at Hendon. The hulls were built by Saunders at Cowes. Later orders followed with 50 H-4 boats being supplied by Curtiss under Contract No. C.P.01533/15.

Porte had flown the H.4 and knew of their limitations and began the task of modifying the boats to get one that would be usable in the North Sea. “At the end of January 1915 I was appointed to take charge of Felixstowe Air Station and in May of that Year I left Hendon altogether and took over Felixstowe completely and have remained there practically continuously” since then. When he went to Felixstowe there were then only “50 men and three small sheds; there are now 1,000 men and an enormous number of sheds... I have built the whole thing up”

Felixstowe’s Experiments

When the first of the Curtiss flying boats arrived in the UK, “Commander Porte was specifically instructed by the Director of the Air Department Admiralty to experiment with and improve the said boats.”

“When the first experiments were taken in hand no engines of high power were available. Consequently, seaplane designers were faced with the problem of “Getting off’ as the chief difficulty. For this reason the early experiments were made with the main object of developing hydroplaning efficiency and the question of simplicity of structure and shockless landing were neglected.”

The first hull tested was a modified Curtiss America flying boat serial 950, one of the original America boats purchased by the Admiralty. This hull weighed light 3,100 lbs and, on certain occasions, 4,500 lbs was taken off the water. The original hull was 30 feet long, and was modified by the addition of a wide longitudinal projecting fin forward, ending at the single step that was under the CG of the machine. The fore and aft angle between the underside of the tail and planning surface of the ship was 10°. The available engines gave about 160-hp.

At high speeds all single step hulls balance on the step and trim depends on the angle of the tail portion, which in order to avoid water drag, should be kept up while accelerating the boat. The original tail plane was lifting and hence excellent from this point of view, and as much load as could be flown with could be taken off the water. In order to improve stability in flight the tailplane was made negative. In smooth water there did not seem to be any appreciable loss in hydroplaning efficiency, but in rough weather, owing to the lack of buoyancy forward, this hull was very wet. The nose of the hull tended to dig in and water was thrown up over the engines to such an extent as to cause the engines to misfire, thus indirectly making it difficult to get off.

A new hull was built for the Aircraft Manufacturing Company by S.E. Saunders Ltd in which the fins were narrower and carried further aft as the step was under the rear spar. The straight lines of the previous form were replaced by curves, the planning bottom being slightly hollow. The underside of the tail was rounded and construction was lighter. This machine was given the serial 1230. This hull proved inferior to that of 950, largely due to the rounded tail section that was not only a less efficient hydroplaning surface but increased suction making it very difficult to lift out of the water in calm weather. This hull was 32 ft in in length. While there was a savings of 300 lbs in weight over previous hulls due to its different construction, it was considerably weaker and “did not outlast many landings.” The Saunders hulls were covered in the patented Consuta stranded copper wire sewn plywood and heavily varnished.

The next hull was made for Curtiss H.4 serial 3545 and was similar to 950 but the tail portion was 2 feet longer, and the fins were wider. The fore and aft angle was reduced from 10° to 7°. “Consequently the machine had to be held at a finer angle of incidence when planning to avoid drag due to (the) submersion of the tail, which caused the getting off speed to be higher.” In smooth water the hull gave a better planning efficiency than the original hull. While the total weight of 4,500 lbs was taken off the water by this hull, the same load as for the original hull, this hull was 300 lbs heavier than the original one.

“The main conclusion arrived at from these experiments were that, from the point of view of planning efficiency and low getting off speed, a large fore and aft angle was essential and a flat bottomed tail portion was advantageous. But it was also evident that much remained to be done in the direction of lighter construction and of general seaworthiness.” From the experiments with these hulls it was learnt that from the point of view of the ability to hydroplane and low take off speed, the tail portion should be flat bottomed to reduce suction, and the fore and aft angle should be large to obtain the necessary trim.

Next it was decided to tackle the problem of easy landing conditions, and increased strength of the hull without sacrificing planning efficiency. “This series ended with the production of ‘Porte I’, which machine showed marked improvement in these particulars.”

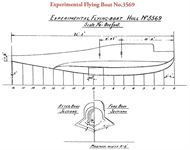

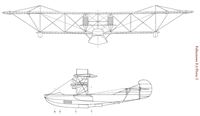

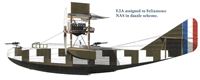

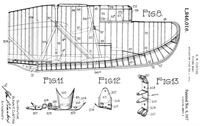

In the early days all landing breakages of flying boat hulls occurred at the step, a structural weak point, indeed a Small America had broken in half at the step. The need to reconsider the best form of hull was evident. The next experiment was to find if a step was necessary at all. A complete new steeper V bottom was built on 3545 having no step but with a steeper fore and aft angle of nearly 20° and with the tail very much swept up with the keel line following a smooth curve. The fins that extended for % of the length were extended back to meet the hull instead of ending off square under the wings as before. The result was to decrease head resistance by making the whole hull more streamline and also to make a stronger hull. This machine was given the serial 3569 and was known as the Transitional boat, as it was the link between the America boats, all those boats that had their fins cut off short at the step, and the Felixstowe group with their long fins and steep V bottom. This hull was 32 ft 2 in long. With the available engines (presumably of nominal 200-hp) there was not enough power to take off. A step was added 5 feet behind the CG and the hull was then capable of getting off but with only 4,200 lbs total load as against 4,500 lbs with the earlier hulls. Although “Getting Off” was not as good as the America boats, landing was exceptionally easy owing to the large fore and aft angle. The deeper V resulted in little or no landing shock with a normal or nearly stalled landing. “This latter method of landing is a very severe test because, immediately the tail portion touches the water, the heavy water drag pulls the machine down very suddenly.” Owing to the step being so far aft of the CG, the hull ran at a small angle and required a large moment to trim the machine back for takeoff. To relieve the pilot of this load the step was shifted 3 feet forward.

The next experiment was the building of “Porte I” an entirely new single step hull built at Felixstowe to carry the same Curtiss superstructure as before. The bows were kept fuller and given a flare or concave entry. Porte used an entirely different form of construction for the next hull with longerons and spacers with wire bracing as used in the construction of landplanes, rather than the boat builder methods used for the Curtiss hulls. The America hulls depended on their tubular shape and stiffness of their skins for strength. They had reinforcement from the keel and, in the larger boats, from bulkheads, and some centre line wiring in the tail, but the rounded form and continuous planking was essential to the structure. Porte’s method gave the requisite strength for a low weight. Originally a single step, located below the rear spar, was fitted. The hull was 36 feet overall in length, three feet longer in the nose and two feet in the tail than the third type of hull.12 The fore and aft angle was 18° and the tailplane was raised 7 inches more than that of the fourth hull, and the line of the keel was kept higher. Fins were carried well at of the step and swept back into the hull. The V-bottom was similar to 3569 and the bows were fuller with a distinct flair on the first three feet.

With this hull the tail portion was liable to catch the water and drag held the speed down to below take off speed. To overcome this, a second step was added 7 1/2 feet from the stern. This modification meant that it was now possible to takeoff but with less load than the earlier hulls. A third step was added intermediate between the main and aft steps. This allowed the load to be brought back to very nearly that of the earlier hulls. This hull was far superior to any hull previously tested at Felixstowe. Owing to the improved form of bow, the cockpits were perfectly dry. Landing shocks were reduced to a minimum, and behaviour generally in alighting and getting off was excellent. Seaworthiness was far superior to the preceding hulls. This hull was named Porte I and the aircraft was subsequently designated the F.1.

3580 had a long and varied career and at the Felixstowe Seaplane School by December 1917, and was flown for many hours by students who did their worse to her. When dismantled for overhaul no serious defects were found other than corrosion of various metal fittings. It survived until January 1919.

In 1918 she was re-engined with two 150-hp Hispano-Suiza engines and subject to further testing. With no step she just staggered into the air in a stalled condition showing that such a thing was possible with a low enough loading. With a single step she was not as efficient as with two steps, thus seeming to confirm the results of the Transitional Boat.

<...>

The "Incidence Boat", H-4 3546 with experimental hull. It is fitted with rotary engines in this photograph. Initially fitted with two 100-hp Clerget engines, it was re-engined with 100-hp Gnome Monosoupape engines. It was finally given two Anzani radials. It served from July 1915 to April 1917. Its part in the Felixstowe story is still unknown.

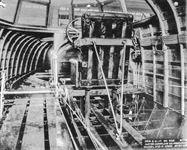

The hull of 8651, the first Curtiss H-12 to arrive at Felixstowe. The hull bottom is concave and the canopy is different to later H-12 boats. Note the "Incidence Boat" in the background.

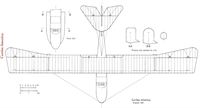

3569 was fitted with a steep V-bottom with fins that carried on almost to the tail without a step. It proved incapable of getting off the water and a step was added as shown on Plan No.5. This enabled the machine to takeoff and exceptionally smooth landings were accomplished due to the deep V-bottom. It was recorded as being tested by Porte and Flt Lt R.J.J. Hope-Vere on 30 May 1916. It lasted until being deleted on 25 April 1917.

3569 was fitted with a steep V-bottom with fins that carried on almost to the tail without a step. It proved incapable of getting off the water and a step was added as shown on Plan No.5. This enabled the machine to takeoff and exceptionally smooth landings were accomplished due to the deep V-bottom. It was recorded as being tested by Porte and Flt Lt R.J.J. Hope-Vere on 30 May 1916. It lasted until being deleted on 25 April 1917.

Curtiss H-4 3570 still has its Curtiss engines installed. This experimental hull had a relative deep afterbody and reduced fin area. Compare with that of 3579. Note the curved shape to the cockpit that has windows in the roof. Compare with 3570. These photographs were included in the section on 3545 in Sueter's report. Unfortunately no photographs of 3545 have been located to date.

Curtiss H-4 3570 still has its Curtiss engines installed. This experimental hull had a relative deep afterbody and reduced fin area. Compare with that of 3579. Note the curved shape to the cockpit that has windows in the roof. Compare with 3570. These photographs were included in the section on 3545 in Sueter's report. Unfortunately no photographs of 3545 have been located to date.

Probably 3579 with a standard hull showing the Curtiss shallow V-form with a slight concave planning bottom.

Curtiss H-4 3579 with Porte type hull. Compare the flat appearance of the cockpit with that of 3570. Note the torpedoes lying in the background.

Aircraft Manufacturing Co (AMC) version of the H-4 1231 was fitted with an experimental hull built by Saunders to Porte's design. The rounded aft section would be similar to that of 1230. Suction prevented the boat's ability to take off and was blamed on the shape of the hull.

Another experimental hull, built by Saunders, and flown at Felixstowe. Aircraft No. 1231, with flight organs of Curtiss H.4, and two Anzani radial engines of 100 h.p. each. fifty machines of similar design but with more powerful engines. These aircraft were delivered in the second half of 1915 and were officially designated Curtiss H.4.

Another experimental hull, built by Saunders, and flown at Felixstowe. Aircraft No. 1231, with flight organs of Curtiss H.4, and two Anzani radial engines of 100 h.p. each. fifty machines of similar design but with more powerful engines. These aircraft were delivered in the second half of 1915 and were officially designated Curtiss H.4.

Saunder's built hull on 1231. The actual input that Porte had into the design of the AMC batch's hulls is unknown, however it must have been considerable given the different hull shapes tried out. They were built under his supervision.

Porte Baby prototype 9800 outside the camouflaged hangars at Felixstowe with another boat with an experimental hull in the background. Note the small cockade on the underside of the Baby's upper wing.

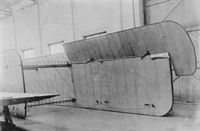

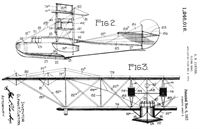

Rearview of the Porte I showing the V-bottom and how the tail of the fuselage like rear hull rose quickly above the water line.

The Porte I hull. When combined with the flight surfaces of 3580 and with two 150-hp Hispano Suiza engines providing power, became the Felixstowe F.1. Note the straight V-form of the hull bottom.

2. Development of the Felixstowe Flying Boats

<...>

The decision was made to experiment with larger hulls and the Curtiss H-8 Large America serial 8650 was obtained. The H-8 was a larger boat built by Curtiss and one that Porte claimed that he had designed. Porte was in Canada in 1915 to witness the testing of the Curtiss Canada twin engined landplane based on the Curtiss America flying boats. Given his connections with Curtiss it is assumed that he would have taken the opportunity to visit the Curtiss manufacturing facilities and discuss his ideas for flying boats for operations in the North Sea. He so claimed in his post-war application for payment due to his inventions with respect to flying boats.

As detailed in Chapter 1 the H-8 was modified to become the H-12. With more powerful engines the H-12 boats did good work but their hull was structurally weak.

Particulars of the H-12 were as follows: Hull length: 40 feet; Maximum beam: 10 feet; Fore and aft angle: 7 1/2°. The hull weighed 2,200 lbs and the complete machine 6,200 lbs when light. The intended takeoff weight was 8,700 lbs with the two 160-hp Curtiss engines. Unfortunately these engines proved incapable of taking this load off and 240-hp Rolls Royce engines were substituted. Even with these engines this load could only be taken off with difficulty. “This was due to lack of buoyancy and it was only when lightly loaded that “getting off’ could be accomplished with ease.”

There was a distinct “hump” speed of about 18 knots, due in part to propeller inefficiency at that speed but mainly to the fact that while at that speed the wings were lifting very slightly while the lift of the hull was also poor and its water resistance high. Once over this “hump” speed, there was little trouble in getting off. “It was evident that a greater load could be taken off were not for this phase of inefficiency.”

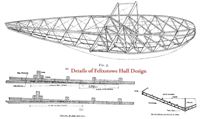

The Porte I hull was superior to that of 8650, so it was decided to construct a new hull on the same lines to take the same Large America, super structure of the Porte I. This was known as the Porte II (later F.2) and was designed along the lines of the Porte I as much as possible on a larger scale. The same construction of a crossed-braced girder with simple longerons and spacers to which the fins were attached was followed. Specifications of this boat were: 16,500 lbs loaded weight; length of hull 42 ft; fore and aft angle 20°. The bows were two feet longer than 8650 and owing to this increase in length it was possible to form the bows with a distinct forward flare. There were two steps, one under the rear spar and the other 7 feet aft of the spar.

This proved a much superior boat. The hump that had been so troublesome with the original hull practically disappeared, the machine accelerated evenly and rapidly to take off; there was no difficulty in getting off with 500 or 600 lbs additional load. The large fore and aft angle proved to have practically eliminated all shock on getting off and landing, and the general seaworthiness was greatly improved. In addition there was a considerable gain in buoyancy and structural strength without increase of weight. The Rolls Royce engines gave the reliability to justify long patrols. The machine retained her original serial.

Felixstowe daily reports do not record when the new hull was fitted but the machine was described as under repair from 10 to 30 June 1916. 8650 made several patrols until 30 September when she was accidently damaged near the Dutch island of Terschelling. Taken in tow she was brought back close to land when the tow line parted and was lost. The wreck was washed up including the whole boat bottom that was found to be still intact. On 4 October the first Curtiss H-12 had arrived and was being erected at Felixstowe.

The Porte Baby was an attempt to build a very large three-engined patrol flying boat. Its development was separate from

the evolving F-boats, and its history is related in Chapter 6.

Commodore Murray F. Sueter wrote in February 1917 that these experiments “are of great value as a ground work in flying boat research and the experience gained in these long and patiently conducted tests will, I trust, enable Wing Commander Porte and the staff of Felixstowe Air Station to continue research on hull design with success proportionate to their efforts.”

The Felixstowe F.2A, F.2B, F.2C, Curtiss H-16 and H-12 Converts are all grouped together as they are all variations of one model, the original F.2.

Their leading dimensions are nearly the same, and their differences are largely due to preferences of their different makers.

F.2C: N64. Built at Felixstowe, open cockpit, tandem dual control and streamline wires. Fastest boat in 1917 reaching a speed of 88 knots. Later converted to F.3.

F.2A: Built by contractors from Felixstowe drawings or modifications of them. The centre sections were wider than F.2C and F.2B to allow for larger airscrews. The early boats had cabin tops, but later ones had open cockpits.

F.2B: The name given to some spare hulls ordered to replace the America, hulls of the H-12 machines, before completion they were altered to be interchangeable with F.2A hulls and the altered machines were known as H-12 Converts.

H-16: The name given by the Curtiss Company to the F.2A built by them.

The story of these machines is one of constant improvement and modification. The original rather crude detail design was perfected and petrol systems, armament, etc., were improved as experience dictated. The gross weight was increased until it had become 11,500 lb, and on special occasions, 12,000 lbs. The increase in power of the Rolls Royce engines compensated in some measure for this increase. Boats failed to get off on occasion, pounding until their bottoms failed. Top speed was usually 80 to 84 knots, while cruising speed was 60 knots.

In 1916 the demand for a long range flying boat led to the design of the F.3 to take the most powerful engines then available, the 310-hp Sunbeam. Due to the demand for this boat it was rushed through the design stage rather than incorporate many improvements in detail that experience had suggested. Redesigning would have caused delays to established manufacturing processes. The hull was still 14 feet wide, but overall length was increased to 45 feet. Gap, chord and span were increased to give an additional 300 square feet of wing area. Provision was made for 430 gallons of fuel. A speed of 77 knots was obtained on trial with an initial climb of 400 feet/minute.

The wings employed a RAF 14 aerofoil section, subsequently changed to a modified RAF 5 section. A great deal of trouble was experienced with the Sunbeam engines and Rolls Royce Eagle VIII engines were substituted. The performance with the Rolls Royce engines was rather better than with the Sunbeams due to their lighter weight, and the useful load was increased.

The F.3 was officially adopted for anti-submarine work in 1917 but did not appear until a year later, but they did some good work before the end of the war. The F.3 proved to have a weakness in the design of the hull planking that would spring and leak badly. Being larger and heavier than the F.2A they were not liked by their pilots. They were restricted to areas where opposition from German aircraft was not likely.

The original F.3, the again modified N64, was completed in December 1916, and was used for patrol work during 1917 as well as participating in various trials and experiments. She outlasted many H-12 machines and was finally deleted thoroughly worn out.

It was decided to design a new boat, the F.5 (there is no record of an F.4), of the same overall dimensions as the F.3 but incorporating all the improvements that experience had suggested but had not been able to be incorporated into the F.3. Originally it was intended to fit one or possibly two Coventry Ordnance Works guns into the design but they were not perfected in time, and the machine was completed for antisubmarine work. The machine had to carry two 500-lb bombs or 4 x 250-lb bombs. The water performance of the F.2A and F.3 had deteriorated as they were more heavily loaded, so the new F.5 was made with a deeper back step and a fuller Reel line amidships. These changes were effective and the boat planned more easily than any of its predecessors.

The chief improvements besides the hull form were as follows:

The size and distribution of the main girder structure were revised and a stronger form of transverse bracing introduced. The junction of planking and keel was strengthened by carrying the timber right across and the disposition of the bulkheads was corrected. Any two compartments could be flooded without the boat sinking. Fuel tanks were rearranged to give a clear access along a gangway on the port side. The rudder post was strengthened considerably making the tail more secure.

A modified RAF 6 aerofoil wing section was employed. Streamline wires were adopted. The whole tail was redesigned, given more chord and lesser span, and better fastening to the hull. As the tail was so much stronger it reduced the rather alarming swaying of the tail which took place with the F.3 when the engines were run up on the ground.

The balanced ailerons and rudder overcame the heaviness that plagued the F.3 s controls. A servo motor was fitted to the ailerons but hardly ever needed. An open cockpit was chosen to give a better view for alighting and fighting instead of the cabin with glass windows. The problem with the windows fogging up was thus eliminated. It was also felt that the open cockpit improved the streamline form and gave a slight increase in speed.

The Porte Super Baby (PSB) or Felixstowe Fury was designed for three 600-hp Rolls Royce Condor engines. As these engines were not available five Rolls Royce Eagle VIII engines had to be used which led to a drop in performance. The PSB was the best boat turned out at Felixstowe. (See Chapter 8)

All the F boats tend to porpoise when the boat was on the step, especially in rough seas, but there was generally sufficient elevator control to check these oscillations.

The Porte Form of Construction:

The main framework of the hull was of the box girder principle fuselage comprising two upper and lower longerons running right fore and aft meeting at the stem and sternpost. Aft of the front spar the sides and top were braced in the usual manner with struts and wire or tie rods. Forward of the front spar the sides were N girders with the top braced as above. Between and below the level of the lower longerons ran the keel and solid keelson without a break. The keel ran from the stern post right around the stem to finish at the gun ring. The keelson terminated at the stem and at the stern post. Deep solid floors, on a level with the top of the lower longerons, joined up the keel, keelson and these longerons to form the backbone of the hull. The chine and fin top longitudinal sweep up into the lower longerons to complete the framework. David Nicolson was a critic of Porte and a supporter of Linton Hope. He was “of the opinion that the keel is of faulty design, for many boats were found to leak badly, partly due to the bad connections between the keel and bottom planking, and partly because the keel is too narrow. The keel and planking are fastened with only one row of brass screws which secure the bottom planking to the keel in the hulls of the F.3 type.”

In the F.5 the timbers were continuous from fin chine to fin chine, notched through the keelson on keel level and from chine to fin top longitudinal, using copper rivets, forming a much stronger combination than in previous F boats.

A timber was fastened on each side of a floor, of which there was usually one at each strut position and one between struts, and two timbers between each floor. Planking was fastened to these timbers. Several fore and aft stringers were fitted, notched out to receive the timbers to which they were fastened. On the original F boats the planking was double diagonal, continuous from stem to stern, fore and aft, and to chine athwart ship, and the step planking added separately. The fin tops and sides to just aft of the rear spar were planked with three-ply, aft of which the sides were covered with doped fabric, a solid mahogany washboard about 1 foot deep extending along this length. The top from aft the pilot’s cockpit was covered in doped fabric laid on fore and aft stringers, supported on formers, forward of which the top of the hull was planked.

Bottom planking was arranged on a diagonal system the inner skin of cedar 1/8 inch thick at the ends and 3/16 inch thick amidships, fitted at an angle of 45° inclination to the keel. The outer mahogany skin was 5/32 inch thick forward, 3/16 inch thick amidships and 1/8 inch aft. The planking being laid at an angle of 30° with the forward end of the planks butting the keel. A layer of varnished fabric was fitted between the two layers making a strong structure.

The fin top on the first series of F boats was of three-ply birch, and in later types was covered with fabric and varnished. The timbers under the fin of the early F.3 hulls were heavy and widely spaced. On later boats smaller timbers spaced closer were substituted to permit all though fastening of the diagonal planking on the hard wood timbers. All the fins on the F.3 were flat, but on the F.5 were given a 1/2 inch camber, that added strength, and assisted in getting rid of water easily.

The timbering at the bow was composed of rock elm and reinforced by horizontal stiffeners below the top longerons. Above the top longerons there were 10 deck-stringers that were notched to take the ribs, together with three strong beams which subdivide the athwartship ribs. This skeleton, which was shaped like a dome, was planked diagonally, the inner skin being laid at 45°, with the outer skin being laid approximately fore and aft to suit the curve of the nose. Each skin was of mahogany 5/32 inch thick, the planking being fastened to the strong beams with wood screws. Although slightly heavier than the rest of the hull, “it is the best piece of construction in the whole boat.” Strength of the fore body is essential for at high speeds the resistance of the air is great and a weak nose would be very easily damaged and driven in.

Abaft the bow planking the sides were of three-ply birch and extended from the bottom of the fin member to the top longeron, running aft to the gun-port openings, a distance of about 18 feet. The rear of the hull had fabric sides, however there were incidents where the fabric did not stand up to the sea and boats were lost. This happened with RAF F.2A and USN H-16 boats. The fabric was eventually replaced with diagonal planking of two skins, each 1/16 inch thick with nainsook between. This was a great improvement as it increased torsional strength and was only about 47 lbs heavier.

For operation from sheltered harbours such as Felixstowe the hulls were suitable. When operational requirements meant that they had to be carried out under less favourable sea conditions, several weaknesses became apparent. The joints leaked, the three ply on the fin tops and hull sides rotting and opening up the laminations. Similarly wash boards split and the fabric rotted. The fin tops were then double planked diagonal with mahogany and cedar, and the sides were either single planked fore and aft, and fabric covered, or planked with “Consuta.”

The solid transverse mahogany floors were fastened to the lower longerons by metal angle plates and notched for two thirds of their depth for the bottom to fit over the keelson. The keelson was notched out one-third of its depth from the top. Although the keelson was nearly 12 deep in parts it was greatly weakened by having one-third of its depth cut away to accommodate the floors. The corner of the joint were filled with square fillets for the whole depth. This was a weak and uneconomical form of construction, resulting in frequent splitting of the floors. The floor was cutaway about two-thirds its depth, thereby sacrificing strength to accommodate the keelson. In Nicolson’s opinion, the “keel is of faulty design ... for many boats were found to leak badly, partly due to the bad connections between the keel and bottom planking, and partly because the keel is too narrow...only one row of brass screws secure the bottom planking to the keel in the hulls of the F.3 type.’

The steps on the F.2A and F.3 were framed with ash bearers 1/2 inch thick, and were three inches deep at the after edge, tapering to meet a board that ran off to a feather edge forward. The steps were of the open type and the planking was fastened with wood screws to the ash bearers. The inner skin was cedar with a mahogany outer skin, both laid diagonally. The whole step was constructed on a bench and then screwed onto the bearers. In some cases the steps would be wrenched off the bottoms of the hull just prior to the boat getting off the water. This was remedied in the F.5 by carrying the inner skin of the bottom right through from end to end of the boat. The outer skin was then put on and carried forward to a feather edge under the main step.

Nicolson considered that another “weak point (in the F boats) is the discontinuity of transverse strength caused by running the timbers down to the keel and stopping them there, no provision really being made to hold the centre girder to the bottom planking or sides of the hull.”

The hull framework, wings and tail structure formed a complete and simple braced structure independent of the hull skin. The only drawback to the wing root structure was the absence of a clear passage through the hull. The wing root spars were one of the most important structures in the machine. They not only carried the weight of the wings, but they supported the engines. When in the air the hull was suspended from them. They were held in position at the sides and centre of the hull by heavy stanchions and struts. They were originally solid wood but in later boats were laminated in two or three sections. Outside the hull they were covered with three-ply birch.

The top of the hull had many openings. The foremost being the gunner’s cockpit with gun ring, followed by the pilots cockpit. Further aft was the wireless operators hatch. The engineers hatch was placed on the port side immediately aft of which was a three-ply footway extending across the hull. Another opening accommodated the wireless mast and lastly there was an 8 inch triangular ventilator. The deck aft was built up with the minimum number of stringers and covered in fabric in order to keep the weight to a minimum. Tie heavier the rear of the hull the greater the bending moment and tendency to shear. The interior of the hull was well lighted due to the doped fabric top.

The front gunners cockpit had a table that extended from his seat to the nose of the hull. Underneath the table was an ammunition box for the Lewis gun trays. The three-ply hinged seat had a high back. The pilots cockpit’s seats for the pilot and assistant pilot had well upholstered seats of kapok cushions that could act as flotation devices if required. The assistant pilot’s seat folded out of the way to open up a clear passage aft. A few feet behind the pilot was located the wireless cabinet together with the operator’s seat, while on the opposite side a ration box was fitted. The engineer’s compartment was situated aft with a ladder giving access to the top of the deck.

A considerable number of metal fittings were used in the construction of the F boats. The chief elements of the structure, such as struts, floors, wing root spars, etc, were held together by light steel fittings. The fittings in the F boats were so many that their manufacture in quantity had a considered influence on production of the boats during the war. Despite Major Rennie’s assertion that they “are readily inspected and do not corrode or rust away in a few weeks as some critics would have us believe. With little attention they will outlive the hull,” many of these were in inaccessible places and to replace them would mean dismantling the hull.

One criticism of this type of construction was that it did not readily admit to the fitting of a double bottom. Major Rennie answered that the F boats on operations had shown that damage caused by flotsam was a very infrequent occurrence. While Capt David Nicolson agreed that the F boats were a “great improvement on the Curtiss type, and were fitted with engines of considerable greater power,” he also noted that “as in previous boats, the bottom gave trouble owing to faulty floor and keel construction.”

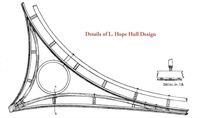

Comparison of the Porte - Linton Hope Methods of Construction

The Linton Hope or flexible type of construction was totally different to the Porte type. It consisted of a keel and keelson continuous from stem to stern post, and a large number of fore and aft stringers distributed evenly around the periphery of the hull that was of streamline form. Small section timbers closely pitched were bent round the stringers, ending at the keel. To these timbers was attached the planking, the inner being diagonally laid, and the outer fore and aft. The planning surface extended from the bows to the main step and was attached to the three-ply formers on the hull bottom and at the step, which was closed, to fore and aft bearers. The fin top was straight and the chine ended at the step. The after step was attached in a similar way. This form of construction led to a double bottom in way of fins.

Nicolson promoted the Linton Hope hull. Linton Hope was a naval architect and designer of racing yachts. The Linton Hope form of construction was entirely different to the method Porte developed. This was claimed to offer fair and easy lines from a circular cross section, consequently offering less air resistance and higher speeds for the same horsepower. They were stated to be generally stronger weight for weight than the F boats, and more seaworthy. The F boat was said to be a compromise with a flying boat forebody attached to a fuselage tail. According to Nielson this compromise proved weak and, as described above, additional planking had to be added to strengthen the hull. Having rectangular hulls they were stated to be weaker in transverse strength than the Linton Hope circular design.

Linton Hope designed the hulls of the A.D., the Phoenix P.5, and the Fairey N.4 flying boats. The A.D. boat was not a success, and while the P.5 had potential the Armistice ended any chance of it being produced in quantity. Nicolson considered the P.5 as “being far ahead of anything previously accomplished.” It was stated that the complicated movement of the elevator to get an F boat off the water was not required with the Linton Hope type as these were designed from model results in the tanks of the National Physics Laboratory, and none of these control movements were necessary. Also the Linton Hope type did not need the complicated wing root structure necessary in the F boats. It was noted that the flying boats were hard to hanger and were often left out at moorings. The Linton Hope hull was considered by Nicolson to have better qualities when moored out.

Replying to Nicolson's 1919 paper, John Porte pointed out that the F boats had a long war record no Linton Hope hull had seen war service and had only been in use for a limited time as experimental models. Nicolson had made no attempt to prove that the Linton Hope type of hull was stronger weight for weight than the F type and as the Linton Hope boat had not been subject to rough usage and handling under actual service conditions, “it did not seem justifiable to make such a statement... During a period of 18 months two seaplane stations operating F boats on the east coast on submarine and reconnaissance patrols had 230,000 sea miles flown to their credit, and not one man lost through unseaworthiness of these boats, although several forced landings had to be made in the North Sea either due to enemy action or failure in the power plant.”

The size of the boats meant that they had to be housed in sheds except where they operated from sheltered harbours and even there they had to be frequently taken out of the water for repairs and overhaul.

To bring in the boats they were put on trolleys while in the water. The trolley ran up an inclined slipway to suit the rise of tide, and were pulled up with the boats in place, and housed in a shed. Now, experience has shown that, apart from crashes and really bad landings, the most serious local stresses which a hull had to withstand were those suffered during its life on the trolley, or getting off and on the trolley. If a flying boat were to be safely and quickly put on a trolley, and, when on, not be distorted locally, the whole weight should be taken on the trolley at the keel. With the F type that could be done, as the transverse bracing at the centre section, where the wing structure joined the hull, was so designed that the resultant loads due to the various weights, such as wings, engines., passed through the keel. The necessary side support was taken off the side bottom longerons, which also formed part of the transverse structure, but no load was taken by the fin or hull planking between the keel and longerons. In the Linton Hope type that was not possible, as there was no such transverse bracing, the result being that unless special props were provided on the trolley to take the load under the engine struts, the hull would distort locally, probably to such an extent that it would be very difficult to keep the hull in the vicinity of the step watertight. Time and experience alone could tell which type of construction would survive as being most suitable to fulfil the many and complex conditions of service,

The critic of Porte hulls, David Nicolson, considered that the F boats were too nose heavy due to the stringers being too closely spaced, while the timbers and bottom were much under strength. Nicolson had “pointed out for many years that any hull construction methods employed on the F.2A. boats could not be seaworthy.” He considered that the hull of a flying boat should be as seaworthy as a motor boat. “A seaworthy hull that could fly was what was required, and could be accomplished if the best yacht builders were given a free hand.” G.S. Baker on the other hand stated that the “real defect” of both the F and P type hulls, that is Porte and Linton Hope, hulls, was that “one could not get at them inside.” For impact experiments on an F hull he had been given a hull “not quite three years old, and the inner skin was rotten in places, not because of bad work, but because it was almost impossible to get there to keep it clean. One could hardly get at some of the structure inside the boats, and if the hulls were to last more than two or three years they must be readily accessible inside.”

“The fact remains that the Porte hulls stood up and are still standing up to the work for which they were designed, in spite of all the adverse criticism and condemnation which they have been and are subject to. Admittedly there are many faults and weaknesses in the Porte hulls, but there are just about as many in the Linton-Hope hulls.” What must be remembered was that Porte was not a theoretician but flew his boats in combat and knew what was necessary to produce a fighting machine that could be produced by firms without the boat building skills needed for the Linton-Hope form of construction.

Just before the Armistice work was in hand to fit steps to the F.5 in accordance with results developed in the NPL tank. This work ceased due to demobilisation. Porte developed the position of the steps from observation as the result of a great deal of experience of taking off and landing flying boats in all types of seas and weather. The experimental F.5 had been flown before there were any full-scale tests of the tank arrangement of the steps.

The US Navy used the F-5-L successfully for many years post war. Maj Buchanan “did not wish to diminish what had been done by the late Major Linton-Hope, with whom he had been in close contact at the Air Ministry and the Admiralty, he pointed out that while he agreed with the criticisms of the F type boats, he thought that to claim that the Linton-Hope method was a complete solution was “going rather long way.” His reason was that there was a lot of experience that had been gained with the F boats while that with the Linton Hope hull was very limited. The wooden hulled Supermarine Southampton utilised a Linton Hope type of hull, but this was soon superceded by the metal hulled Southampton. The argument as to which hull construction was the better was now of academic interest only.

Post-war Porte made a claim to the Royal Commission on Awards to Inventors for the work he had carried out on developing the flying boat during the war. The claim was separated into two separate cases:

1. The claim in respect of the American Flying Boats delivered in Felixstowe in August 1914.

2. The claim with respect to the subsequent modification of this flying boat.

The claim was considered under three heads:

(a). What was the value of the novel features in this boat?