Журнал Flight

Flight, March 9, 1912.

AIR EDDIES.

Illustrative of the difference of meaning one small word can effect in a sentence, is the inscription that appeared last week under the photograph depicting the landing chassis of the new Hanriot-Pagny monoplane. By a slight slip on the part of the compositor the phrase "modelled on pronounced Nieuport lines" was made to refer to the chassis in question, instead of to the machine itself. As a matter of fact the landing gear is really the only section of the machine that differs a great deal from contemporary Nieuport practice.

Flight, April 27, 1912.

FOREIGN AVIATION NEWS.

A New Fast Hanriot Monoplane.

ANDRE FREY has been carrying out, at the Hanriot School at Rheims, some tests with a new Hanriot monoplane built for speed. After a cross-country trip on the 13th inst., the machine was timed to cover a kilometre in 25 seconds, giving a speed of 138 k.p.h.

Flight, May 25, 1912.

AIR EDDIES.

Sydney Sippe is now definitely engaged as chief pilot to Hanriot (England) Limited, and, as one who knew him when aviation here in England was quite a little infant, I must indeed congratulate him on his appointment. He will not be back over here just yet. He plans to stay at Rheims for another week or so to get more practice on the new machine. When that is over he reckons to bring the new monoplane with him, maybe by air.

Sippe Doing Well at Rheims.

ON the 15th inst. at Rheims, Sydney V. Sippe was trying one of the new Hanriot machines and made a trip of 50 kiloms. at a height of 400 metres. On Saturday he also made a good flight at a height of about 600 metres.

Flight, April 27, 1912.

FOREIGN AVIATION NEWS.

Marcel Hanriot a Superior Pilot.

ON the 18th inst. Marcel Hanriot completed his qualifying flights in order to obtain a French superior brevet. Leaving the Betheny ground at Rheims at 6.7 p.m. he turned at Vitry-le-Francois at 6.44 and was back at Rheims at 7.23 p.m. During the outward journey he was at a height of 1,500 metres and coming back his speed was well over 120 k.p.h. He had made a similar flight on the previous day.

Flight, June 15, 1912.

Testing a New Hanriot.

BIELOVUCIE, on the 7th inst., was testing at Rheims the new 80-h.p. three-seater Hanriot built for the Ae.C.F. Grand Prix. With a pilot weighing 70 kilogs. and a load of 170 kilogs., including oil and petrol for two hours, the machine climbed 360 metres in 4 mins. 30 secs.

Flight, July 13, 1912.

A Fast Run Home.

AFTER the opening ceremony at the Bar-le-Duc Aerodrome, Lieut. Marlin started up on his Hanriot monoplane, and flew back to Rheims, covering the 100 kiloms. in 65 mins.

Flight, August 31, 1912.

BRITISH NOTES OF THE WEEK.

Sabelli Flies to Salisbury Plain.

ON Thursday, last week, Sabelli on a 50-h.p. Hanriot, made an excellent flight from Brooklands to Salisbury Plain where the Army Trials are in operation. In spite of a strong wind averaging about 25 m.p.h., Sabelli steered a straight course for his destination.

Flight, October 19, 1912.

THE HANRIOT MONOPLANE.

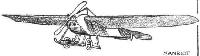

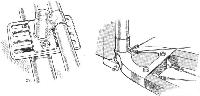

IT is not surprising that the new Hanriot monoplane has a great deal in common with the Nieuport, for the reason that its designs are due to M. Pagny, who had collaborated with M. Edouard Nieuport in producing the latter's monoplane. There are refinements of design noticeable throughout in the new Hanriot, but the main differences are centred at the landing chassis - the shape of the stabilizer, and the operation of the controls. Let us therefore deal with these first. Recognising the difficulty that not a few pilots have experienced in using the Nieuport chassis, the Hanriot firm have been most wise in adopting a form of landing gear that is, we might almost say "fool proof." It consists simply of an orthodox pair of skids with an orthodox pair of wheels strapped down to them by elastic bands. But even in such a much used form of chassis there has been introduced a very useful refinement. In place of the usual plain types of radius rod, a system of tie rods is used, whereby the axle carrying the landing wheels may travel, when the wheels encounter a bump, in a straight vertical path. With the ordinary type of radius rod the axle travels along an arc of a circle, a movement which is none too kind to the rubber straps employed. One of our sketches illustrates this point.

Another advantage this chassis has is that it extends sufficiently far back to enable the rear struts to serve as a point from which the wing warping may be operated. In this manner the more or less customary form of lower cabane is done away with - and the head resistance that it would give rise to also.

One of our sketches shows one of the two bell cranks, one on either side, through which the warping is actuated. It is rather noticeable that the warp is geared up, for the arm taking the control wire is shorter than the other.

As for the wings, they are, to outside appearance, so exactly like those of the Nieuport that there is little need to describe them. They have the refinement that provision is made whereby they may be folded, for convenience sake, along the side of the fuselage.

The upper cabane has a very good point about it. The top wires from the wings pass through a fitting which may be adjusted in relation to the cabane skeleton. By this system the top wires can be dismantled very easily and their tautness can as simply be varied. The stabilizer is made so that it may fold down readily in two halves. Each half is hinged to a tube running parallel to, and on a level with each top member of the fuselage at the rear. It is kept up in place by wires when in use. The rudder, too, folds in neatly.

Naturally, when a new machine makes its appearance, everyone who has anything to do with aeroplanes makes it his business to "quizz around," criticise and communicate the result of his inspection to anyone who may be similarly interested.

Everyone on the Plain had a good look round the Hanriot, but, for once, no criticism reached our ears. But there, perhaps, we are wrong - we heard one of the official passengers in the three hours' duration test relate that his neck had got seriously out of truth through having to resist, for such an extended period, the pressure of the relative wind. The 100-h.p. Hanriot monoplane averages a speed of about 73 m.p.h.

Main characteristics :-

Length 24 ft.

Span 41 ft. 9 ins.

Weight without complement or fuel 981 lbs.

Motor 100-h.p. Gnome

Propeller, Chauviere 2.55 m.diam.

The Hanriot School at Rheims.

TESTING a new 50-h.p. Hanriot monoplane sold to Italy, Bielovucie, on Saturday, mounted 1,500 meters in 9 mins., the machine carrying a load of 160 kilogs. Ponnier on the machine, with Rossel-Peugeot motor, put up a flight of two hours-duration. Ranlet and Favre also did good work on a new machine with a 60-h.p. Anzani motor. Two days previously "Bielo" took a passenger for a round trip: Rheims-St. Quentin-Compiegne-Rheims.

Flight, October 26, 1912.

Two Hours on a Hanriot.

PONNIER made a two-hour trial on the Hanriot monoplane with Rossel-Peugeot motor, on the 18th inst., and Bielovucie took up 160 kilogs. of ballast on a 50-h.p. military machine, 1,101 metres in 11 mins. "Bielo" and Frey afterwards tested four machines before handing them over to the French Army. Four more were delivered on Sunday.

Flight, November 9, 1912.

THE PARIS AERO SALON.

Hanriot.

THESE machines are in general outline a great deal like the Nieuport. The main difference lies in the chassis, which, m the Hanriot, is a particularly neat and robust wheel and skid construction. M. Pagny, who is responsible for its design, gave us a most thorough demonstration of all its fine points. To start with, the workmanship throughout is superb, and that is not only confined to show machines. The machines they turn out in the ordinary course of things are just as finely made.

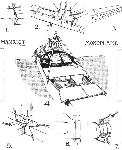

First of all, the propeller. Most of those who have had anything to do with Gnome-engined monoplanes know what a delicate job it is to remove a propeller that has become stuck on its taper. Unless a special tool is used, a good deal of jarring has to be resorted to, and many good Gnome noses have not been improved by the treatment. Pagny sees this, and obviates it by running a thread at the wider end of the taper, and putting on a screw ring before the coupling is placed in position. Thus, if it is at all tiresome to remove, just a turn or two of the screw ring will bring it off. Then, as previously mentioned, the motor may be taken out of the machine, carlingues and all, in almost no time. One of our sketches shows this detail well. Each side of the front carlingue is formed as a hinge, the core of which can be removed by knocking out the key that keeps it locked in its place.

The back-plate of the Gnome is treated in the same fashion. There is an interesting fitting, at the cabane on top. All the upper wing cables pass through this fitting, and the whole fitting, cables and all, can be taken clear by unscrewing a nut and lock nut. Thus there is no necessity to disconnect these cables when transporting the machine from place to place, for the wings may be fixed horizontally along the side of the fuselage in special fittings provided for that purpose. The tail is built up of steel tubing acetylene welded. That, too, is made to fold down alongside the fuselage by merely removing a bolt or two. Another of our sketches shows the cockpit and its assortment of cross-country instruments. It also shows the tool box conveniently arranged just behind the pilot's seat. A point of failing about the Hanriot monoplanes that figured in the British Military Trials was that observation was rather difficult. In the 100-h.p. Gnome two-seater shown the passenger's seat is much further forward, and allows of a view almost directly beneath the machine. Another Hanriot monoplane is shown on the Rossel-Peugeot stand. It is an all-metal product and wonderfully made.

As for weight, there is a considerable saving on this machine, for whereas a machine of a similar type in wood weighs, all on, 660 lbs., this model complete turns the scale at only 550 lbs. So that the wings may warp without permanently deforming the wing skeleton, each rib, which only weighs 8 1/2 ozs., is jointed loosely at its four points, the leading edge, the front and rear spars, and the trailing edge. A 50-h.p. Rossel-Peugeot motor is installed in this machine, and, Pagny says, it is giving excellent results. We sometimes wonder why more of this engine has not been heard in the past. It is an excellent job throughout, easily one of the best specimens of rotary engine construction at present on the market, and, by the way, there are quite a number now. It has been in existence something like two years, and yet no one seems to have used it. But perhaps their time is coming now. This, however, scarcely concerns the Hanriot monoplane. All praise to them!

Flight, December 7, 1912.

WHERE AEROPLANES ARE BUILT.

A Visit to the Works of Messrs. Hewlett and Blondeau.

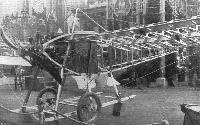

You enter, and there, at the nearer end of the main shop, which covers a floor space of, roughly speaking, 150 ft. by 60 ft., is a magnificent specimen of a 50-h.p. single-seater Hanriot monoplane, standing fully assembled and completed, and waiting simply for the attention of the dismantler and packer to see it away on its journey to Rheims. Once there it will be tested in flight, and then handed over to a foreign government. For the French Hanriot firm have so many orders on hand that they have a difficulty in keeping pace with the demand for their machines. Three aeroplanes altogether have they instructed Messrs. Hewlett and Blondeau to build for them, this Gnome-engined single-seater, another single-seater with a 45-50 h.p. Rossel-Peugeot motor, and a 80-h.p. Gnome two-seater. And what better tribute to British workmanship, and more particularly to the workmanship of the firm we are considering at the moment, could be paid, than by the mere fact that these machines are being constructed to the order of a concern that has such a high international reputation for excellence in every branch of its work.

Down to the smallest detail, with the exception of some few of a special type of wire strainer that are obtained from France, these machines are entirely British built. But let us turn to the works itself, and to the system under which the turning of the crude materials into complete aeroplanes proceeds.

In dealing with aeroplanes the raw material falls into three classifications - wood, fabric and metal.

So we find that three sections of Messrs. Hewlett and Blondeau's works have been set apart for dealing solely with these three materials. At the near end the wing covering is done. All the wood working machinery is arranged to the left, the metal working machine tools to the right, and in the open space between, the assembling of the finished parts is carried on. Let us trace the works system, beginning with the assumption that the blue prints for the machine to be built have arrived. They are first scrutinized by the works manager who notes the materials and the quantities of it that are required to see the work safely through. Orders are written for the material that does not happen to be in stock, and the blue prints are sent on to the pattern shop where all the jigs, patterns and special tools that will be required for the work in hand are made. These are probably completed by the time the material ordered has been delivered. As delivery takes place so the material is sorted. Raw material, such as sheet steel and planks of wood, passes into the general store; finished material, such as piano wire, nuts, bolts, and wire strainers being sent to the finished-parts store. From the pattern shop, the blue prints are handed luck to the Works manager, who passes them on to the foreman who has charge of the various departments in which the work appropriate to the several drawings is carried out. They in their turn pass them on to their workmen, and the actual work of construction commences.

Material is obtained from the stores, which are presided over by one whose duty it is to keep an account of every scrap of metal, wood, or fabric that leaves his department. To facilitate his work, every part that goes to make up a complete aeroplane is allotted a number, and whatever materials are "requisitioned" from the store for the making of that part are booked down to that number. Thus the storekeeper can tell, from reference to his books, the exact cost of the material that has been used in the production of any one part.

But this does not give the total cost of the part, for labour must be taken into account. The manner adopted by Messrs. Hewlett and Blondeau is to send out with the drawings for each fitting a card which bears the same number as the fitting, and which always accompanies it, no matter whose hands it passes through in the process of manufacture. On this card all those men who have anything to do with the manufacture of that part write down the time they have spent on it. Take, for example, the case of a gross of welded steel strut sockets to be manufactured. The material has already been taken from the store and with it a time card. The first operation is to stamp out the steel base-plates and he who carries this out makes a note on the card to the effect that workman such and such a number - every workman bears a number, as well as each fitting - has spent so much time on that part. While this is being done, we will say that three lads are busy cutting off short lengths of streamline steel tubing for the sockets. They, too, make a note on the same card as to how long they have taken over their section of the job. Then comes the welder, and after him the finisher. By the time the gross of sockets is completed, the cards bears the numbers of all those who have worked on the job, and the respective times they have spent on it. Thus the total cost for labour in the production of that particular gross of sockets is established.

But even that, added to the cost of material, does not give the total cost, for a proportion of the general works and office expenses, such as rent, rates, lighting, &c, must be added.

When the part is finished, it is taken into stock in the finished part store. In this manner the whole of the parts that go to the making of the complete aeroplane, or the batch of them, are finished and stocked away in their proper place.

When all the parts are ready, assembling is commenced. In assembling, too, a similar system of material and labour recording is observed, so that by the time the machine is ready for the aerodrome its total cost, even down to the last nut, may be determined.

Such then, in its broad outlines, is the system governing aeroplane construction in the works of Mrs. Maurice Hewlett, our first British airwoman, and her partner, Mr. Blondeau, also a certified pilot. They have established a works wherein they may, unoccupied by the consideration of any machine of their own type, construct aeroplanes on a large scale at a correspondingly low cost, to the designs of their clients. And their example is one that should be a lesson in many ways, and should dispose of much misconception as to the real source of profit in aeroplane construction. This firm is certainly exceptionally well placed for doing well for themselves, as their plant is most complete, their workmen thoroughly experienced and well chosen, and their stores well stocked with everything that could possibly be required in aeroplane construction. In their finished-part store we saw an enormous stock of Gnome engine spare parts, for in these, we understand, Messrs. Hewlett and Blondeau do a considerable trade.

One of their chief features is oxy-acetylene welding work, not only for steel but for all metals. Mr. Blondeau told us that he had no fewer than ten men on probation before he decided which one to select to place in charge of that department.

"Remember you have a man's life depending on how you do your work" runs the shop's motto. The men have the seriousness of their work at heart.

Flight, December 28, 1912.

TESTING A 100-H.P. MONOPLANE.

A REMINISCENCE By SIDNEY V. SIPPE.

Il est quatre heures, Monsieur, et il n'v a pas de vent!

There was a tired night porter bending over me turned over sleepily, and gradually roused myself "Four o'clock, is it?" and then it suddenly dawned across my sleepy brain that I must be up and doing, for way out at the Aerodrome de la Champagne was a new type of monoplane that I had to go and test that morning. Although so early, the sun was already beginning to make itself felt, which was perhaps as well, for the previous night had been so stifling that my friends and I had taken our mattresses and bed trappings out on to the balcony and had turned in there. Dressing did not take long, and within a few minutes we were a merry and thoroughly awake party, settled more or less comfortably in a car that had been sent down from the aerodrome to carry us there. With the exception of ourselves and a party of revellers from a cafe opposite, who were making a noisy departure after carrying their celebrations so far into the morning, no one was astir. We sped through the deserted cobbled streets of the town as rapidly as possible, considering the nature of their surface. We were impatient to get to the aerodrome, and had no eyes to appreciate the beautiful gardens and well laid-out flower-beds that we passed. Striking the Neufchatel road, a quarter of an hour brought us to the flying ground, by which time the sun, intent on providing another stifling day, had almost cleared the atmosphere.

This was the celebrated Rheims aerodrome, stretching away perfectly flat in all directions as far as the eye could reach. Dotted here and there one could discern the several pylons that marked out the 10-kilom. course, over which the Gordon-Bennett Eliminating Trials were to be run. Away to the left, about a mile and a half distant, was a battery of 40 hangars, owned and used exclusively by one well-known monoplane firm. Here, I thought, was activity with a vengeance. In England, forty sheds are as many as we get in an average aerodrome, occupied, perhaps, by twenty or more different firms or individuals. Our interest was centred around one of our line of hangars, whose shutters were being rapidly taken down by four mechanics. They ran out two machines, the big 100-h.p. passenger-carrier that I was destined to test, and a miniature racing monoplane. There was something like father and son about the two machines, so alike were they, but so different in size. Although there was little to do to my machine, since all preparations had been made and fuel tanks filled overnight, the mechanics were bustling around in a typically vigorous fashion. It is a peculiarity of French mechanics that, even if there is little or nothing to be done, they seem bent on making a brave exhibition of excited activity. And this is infinitely more noticeable when the designer, the business manager, or the works' manager happens to be near. It was so in this case, for the man whose clever brain had evolved the machine was here, there, and everywhere, pulling at the cables, examining fastenings, drumming the fabric, and thoroughly examining everything. Personally I had no preparations to make, except to have a glance round the machine, tread into my overalls, put on a helmet, and get my goggles ready.

My feelings were rather difficult to analyse, and I stood there waiting for the machine to be pronounced ready, badgered the while by well meaning, but fearfully annoying friends, who kept up a running fire of advice as to how best to contend with the peculiarities of a powerful high-speed monoplane, and more especially what to be prepared for when turning to the right with such a high-powered rotary motor. None of them appeared to me as if they had ever flown a yard, let alone a machine of that power. My feelings were very similar to those I had experienced in my schooldays when waiting outside the schoolroom to be admitted in five minutes' time to undertake the answering of a dozen or so unknown questions. It was not nervousness - it was a vague feeling of wonder as to what would happen.

The machine now stood ready, and I clambered up, and got comfortably installed in the spacious cockpit. The arrangement of the controls was exactly the same as on the lower horse-powered monoplanes of the same type that I had previously flown. There only remained to waggle the lever and the rudder-bar to see that the warping, rudders, and the elevator were working properly. In front one of the mechanics was priming up the engine with petrol. Two of his fellows were lying full length under the fuselage, gripping the wheels, two more were hanging on to the wing tips, and the rest of them were clinging to the tail. "Contact," said he in front, and I switched on. He gave the propeller a lusty swing. The motor spluttered and got into its stride. Fourteen cylinders spitting fire, oil and smoke and emitting a deep rhythmic roar, for all the world like a low Bourdon organ note. It is infinitely more plowing to the ear than the staccato of the 50-h.p. Gnome. Tin oil is coming through and pulsating in the gauges; I try the petrol-tap and the switch and find them working properly, so I wave to the mechanics to release their hold. Frankly, I must admit to being rather paralysed at the speed with which the big monoplane bounded away over the ground. Very gingerly I pulled the lever back, and sat there holding on tight and waiting for something dreadful to happen. A few seconds passed - to me they seemed an eternity. Nothing terrible had happened so far - perhaps nothing terrible would happen. My muscles subconsciously relaxed, and I settled down to think things out quietly. Here I was, sitting in a big machine, rushing through space at nearly 80 miles an hour in a relative wind which threatened, so it seemed, to blow my head clean off my shoulders. There was nothing to do, and gradually it dawned upon me that this was quite the simplest machine I had ever flown. The sense of security was remarkable, indeed. I was perfectly convinced by this time that nothing dreadful could possibly happen. I might have been sitting in a Dreadnought, so steadily and solidly did the machine force its way through the air. I began to look around. The ground was about a thousand feet below, and the machine was still rising, although the inclinometer showed that the machine must have been doing so on a perfectly even keel. Another curious point was that the engine seemed somehow not to be pulling. The revolution indicator, however, showed that it was doing, if anything, a trifle over its normal 1,200 revolutions a minute. It was the evenness and smoothness of the turning of these fourteen cylinders that gave rise to this delusion. Surely about time I turned; so putting the nose of the machine down a few degrees, I pushed the rudder-bar over to the left. The big monoplane banked slightly, and the ground below, sheds, bushes, hedges, and everything, revolved through 180". I was now heading for the sheds, feeling perfectly comfortable, and enjoying myself immensely. Now that they were directly below me, and, forgetting all that my friends had told me about the terrors of a right hand turn with a big engine, I pushed my right foot forward, and swung round. Not until I was right round did I realise that I had accomplished a supposedly difficult manoeuvre. I straightened the machine out to get a clear run down to the ground in front of the sheds, and putting the elevator slightly forward, cut off the petrol. Immediately there was silence, except for the gentle hum from the propeller and wing cables as I planed down. The machine touched ground, ran along, rapidly losing speed, bumped twice, and stood still. Almost before I had time to look round the machine was surrounded by a crowd of mechanics, all firing off questions in rapidly spoken French. I had little or no idea what they were talking about, but my stock phrase, "Ca marche bien," seemed to please them well enough. In fact, we were all very pleased; the designer because another of his machines had proved eminently successful, the mechanics because they had followed the machine right through the works from crude steel and wood, and myself because I had done what little I had done.

* * * *

Just outside the aerodrome there is a little inn named, appropriately enough, "Le Progres de l'Aviation." Anyone passing might have remarked a noisy group of oily-looking individuals sitting around one of the tables outside. Nothing short of "fizz" that morning!

Flight, February 1, 1913.

FLYING THE ALPS.

AFTER waiting over three weeks, and almost deciding to give up his attempt to cross the Alps, at any rate for the present, Bielovucic was confronted with a favourable opportunity on the 25th ult., and immediately took advantage of it. During the previous night and early morning there had been heavy falls of snow, but the conditions overhead were good, and so preparations were made for the start. The snow was cleared away to provide a getting-away ground, and the Hanriot machine, the slight damage sustained a fortnight previous having been made good, was thoroughly looked over. Satisfactory reports as to the weather in the Pass and at Domo d'Ossola were received, and at 12 o'clock "Bielo" had started from Brigue. Ascending spirally to a great height, he disappeared in the direction of the Simplon, passing over the Saltine ravine. He was continuing to rise, and there was an anxious moment when the engine suddenly stopped. Fortunately it started again, and in a few minutes the machine was over the Hospice. In fourteen minutes he had passed Simplon Village, and shortly after he was in sight of his goal. Carefully avoiding the dreaded Gondo Valley, he passed over the Monscera mountain and then vol planed down to within a hundred yards or so of the monument to his countryman, Chavez. He had taken 26 minutes for the trip for the distance of between 12 and 13 miles. The Hanriot machine which was used was equipped with an 80-h.p. Gnome driving a Chauviere propeller.

Показать полностью