Книги

Журнал

Flight за 1913 г.

819

Журнал - Flight за 1913 г.

Flight, July 5, 1913.

THE PIONEERS.

<...>

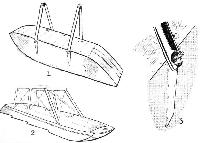

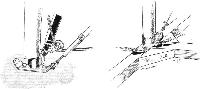

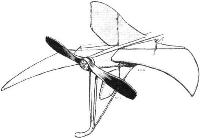

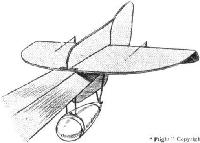

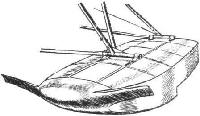

A pioneer who is perhaps not so well remembered as he should be is Hargrave, who is, of course, famous as the inventor of the box kite, but whose researches in aviation generally are less well known. He read a most interesting and instructive series of papers before the Royal Society of New South Wales, and in 1885 he succeeded in demonstrating before that assembly the successful flight of a model that was propelled by flapping wings.

<...>

THE PIONEERS.

<...>

A pioneer who is perhaps not so well remembered as he should be is Hargrave, who is, of course, famous as the inventor of the box kite, but whose researches in aviation generally are less well known. He read a most interesting and instructive series of papers before the Royal Society of New South Wales, and in 1885 he succeeded in demonstrating before that assembly the successful flight of a model that was propelled by flapping wings.

<...>

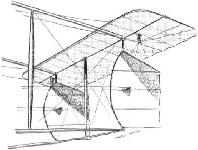

Hargrave's wing-propelled model built in Australia in 1885. - The wings were for propulsion only, the weight in flight being supported by the aeroplane surfaces fore and aft. Several successful flights were made. Elastic provided the motive power.

Flight, September 13, 1913.

Berlin - Paris.

STARTING on Friday of last week at 5.30 a.m. from the Johannisthal aerodrome, the German pilot Herr Friedrich with Dr. Ellias as passenger, on an Etrich-Taube, commenced a voyage which he hoped to terminate the same day in Paris, but circumstances were against him. Although he was bothered by mist, he determined to make the attempt, and after a good flight he descended at Walhrewald, near Hanover, at 7 o'clock, where he replenished his fuel and oil tanks, making a re-start at 9.15, steering away towards the west. Flying well, after a descent at Gelsenkirchen, he arrived at Berghen Sainte-Agathe, about 13 kilometres from Brussels, at 2.15p.m., where the two voyagers replenished the inner man as well as again taking in petrol and oil. At 4 o'clock Friedrich was away again, hoping to reach Paris during the evening, but after passing over the Belgian frontier he encountered a violent storm which was raging in the district, forcing him down at Sart les Bruyeres, a few kilometres from Mons, where he decided to stay for the night, having accomplished roughly about 700 kilometres from his starting point. Next day the weather was still as bad as ever and he therefore postponed the last lap of the journey until Sunday, when he got away at 1.15 in spite of a thick fog, a damaged map, and a compass out of order. After a couple of stops at Guise and Senlis, he arrived at Villacoublay at 5.15 (passing over Paris, which was enveloped in a heavy mist) there to be received with a splendid ovation by a large crowd of his fellow aviators who were in strong evidence by reason of there being a big festival in full swing at the time of his arrival.

Flight, September 20, 1913.

FLYING AT HENDON.

<...>

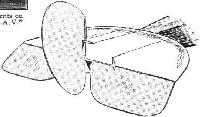

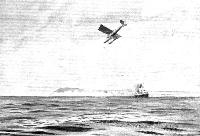

After two laps had been completed all attention was transferred from the cross-country race to a bird-like machine approaching the aerodrome from the south some 3,000 ft. up. When above the aerodrome the machine was easily recognised as an Etrich, with its dove-like wings and fan-shape fail. The pilot made a beautiful spiral descent, banking well over 60°, just as some of the cross-country competitors were entering the aerodrome. It was a very impressive sight, for the Etrich is certainly one of the prettiest monoplanes extant. The monoplane came to rest close to No. 1 pylon, and was immediately surrounded by a crowd thirsting for information. When the passenger - for there were two on board - removed his goggles, we recognised in him Herr I. Etrich, the designer of the much admired monoplane. The pilot was Alfred Friedrich. With the help of E. Baumann, who acted as interpreter, we ascertained that the aviators had left Paris at 11.20 that morning, arriving at Calais at 1.55, where a stay of 1 1/2 hours was made. The remainder of the journey to Hendon was made without a stop in 2 hours 5 mins., flying at an altitude of about 4,500 ft., and encountering very rough weather. Having found out all about our visitors, we turned our attention to the neglected cross-country race, which had by then finished.

<...>

In spite of the very high wind on Sunday afternoon several of the Hendon pilots ventured out and put up some fine exhibition and passenger flights. The star turns of the afternoon, however, were the splendid displays by Gustav Hamel on the 80 h.p. Bleriot and Igo Etrich on the Etrich-dove monoplane. The former indulged in a cloud-hunt lasting over an hour. It was a performance strange to behold; he made for cloud after cloud, turning again and again, only to find the clouds still above him. Eventually he saw a large one, which he made for and passed over the top. Having accomplished this feat he descended, as he was running short of oil. He was stiff with cold when he alighted, and the barograph recorded a height of 9,500 ft. The flights of the Etrich monoplane were very picturesque, the pilot executing some remarkable highly banked spirals.

HERR FRIEDRICH FLIES TO LONDON.

FOLLOWING on his flight from Berlin to Paris, recorded in last week's issue, Herr Friedrich, on Saturday morning last at 11.20, accompanied by Herr Igo Etrich, on the Etrich-Taube with Chauviere propeller, left Issy for London by way of the air. At Calais he descended at I.55, where he was delayed somewhat in connection with some of the official requirements, so that he was not able to continue his flight until 3.45. At that hour he was away again, arriving at Hendon aerodrome, after a magnificent flight, in the middle of one of the speed races, at 5.50, his altitude being about a thousand metres during most of the trip. Directly it was recognised who the voyagers were, they were very hospitably treated, and during the afternoon Herr Friedrich gave some exhibitions of his flying on the Etrich-Taube. On Wednesday this week, Friedrich was due to leave England again, this time taking as passenger Mr. John Rozendaal, the managing director of the Etrich Co. It is proposed to cross the Channel to Calais, and then fly direct for Utrecht, Holland, before returning to Germany. Mr. Rozendaal has from the earliest days been associated with aviation, he having been in Germany connected with the Wright machines before taking up the Etrich monoplane. It was Mr. Rozendaal also who engineered the late Mr. Latham's flight in Berlin from the Tempelhofer Feld to Johannisthal in 1909.

Berlin - Paris.

STARTING on Friday of last week at 5.30 a.m. from the Johannisthal aerodrome, the German pilot Herr Friedrich with Dr. Ellias as passenger, on an Etrich-Taube, commenced a voyage which he hoped to terminate the same day in Paris, but circumstances were against him. Although he was bothered by mist, he determined to make the attempt, and after a good flight he descended at Walhrewald, near Hanover, at 7 o'clock, where he replenished his fuel and oil tanks, making a re-start at 9.15, steering away towards the west. Flying well, after a descent at Gelsenkirchen, he arrived at Berghen Sainte-Agathe, about 13 kilometres from Brussels, at 2.15p.m., where the two voyagers replenished the inner man as well as again taking in petrol and oil. At 4 o'clock Friedrich was away again, hoping to reach Paris during the evening, but after passing over the Belgian frontier he encountered a violent storm which was raging in the district, forcing him down at Sart les Bruyeres, a few kilometres from Mons, where he decided to stay for the night, having accomplished roughly about 700 kilometres from his starting point. Next day the weather was still as bad as ever and he therefore postponed the last lap of the journey until Sunday, when he got away at 1.15 in spite of a thick fog, a damaged map, and a compass out of order. After a couple of stops at Guise and Senlis, he arrived at Villacoublay at 5.15 (passing over Paris, which was enveloped in a heavy mist) there to be received with a splendid ovation by a large crowd of his fellow aviators who were in strong evidence by reason of there being a big festival in full swing at the time of his arrival.

Flight, September 20, 1913.

FLYING AT HENDON.

<...>

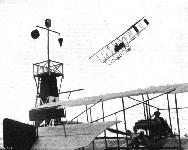

After two laps had been completed all attention was transferred from the cross-country race to a bird-like machine approaching the aerodrome from the south some 3,000 ft. up. When above the aerodrome the machine was easily recognised as an Etrich, with its dove-like wings and fan-shape fail. The pilot made a beautiful spiral descent, banking well over 60°, just as some of the cross-country competitors were entering the aerodrome. It was a very impressive sight, for the Etrich is certainly one of the prettiest monoplanes extant. The monoplane came to rest close to No. 1 pylon, and was immediately surrounded by a crowd thirsting for information. When the passenger - for there were two on board - removed his goggles, we recognised in him Herr I. Etrich, the designer of the much admired monoplane. The pilot was Alfred Friedrich. With the help of E. Baumann, who acted as interpreter, we ascertained that the aviators had left Paris at 11.20 that morning, arriving at Calais at 1.55, where a stay of 1 1/2 hours was made. The remainder of the journey to Hendon was made without a stop in 2 hours 5 mins., flying at an altitude of about 4,500 ft., and encountering very rough weather. Having found out all about our visitors, we turned our attention to the neglected cross-country race, which had by then finished.

<...>

In spite of the very high wind on Sunday afternoon several of the Hendon pilots ventured out and put up some fine exhibition and passenger flights. The star turns of the afternoon, however, were the splendid displays by Gustav Hamel on the 80 h.p. Bleriot and Igo Etrich on the Etrich-dove monoplane. The former indulged in a cloud-hunt lasting over an hour. It was a performance strange to behold; he made for cloud after cloud, turning again and again, only to find the clouds still above him. Eventually he saw a large one, which he made for and passed over the top. Having accomplished this feat he descended, as he was running short of oil. He was stiff with cold when he alighted, and the barograph recorded a height of 9,500 ft. The flights of the Etrich monoplane were very picturesque, the pilot executing some remarkable highly banked spirals.

HERR FRIEDRICH FLIES TO LONDON.

FOLLOWING on his flight from Berlin to Paris, recorded in last week's issue, Herr Friedrich, on Saturday morning last at 11.20, accompanied by Herr Igo Etrich, on the Etrich-Taube with Chauviere propeller, left Issy for London by way of the air. At Calais he descended at I.55, where he was delayed somewhat in connection with some of the official requirements, so that he was not able to continue his flight until 3.45. At that hour he was away again, arriving at Hendon aerodrome, after a magnificent flight, in the middle of one of the speed races, at 5.50, his altitude being about a thousand metres during most of the trip. Directly it was recognised who the voyagers were, they were very hospitably treated, and during the afternoon Herr Friedrich gave some exhibitions of his flying on the Etrich-Taube. On Wednesday this week, Friedrich was due to leave England again, this time taking as passenger Mr. John Rozendaal, the managing director of the Etrich Co. It is proposed to cross the Channel to Calais, and then fly direct for Utrecht, Holland, before returning to Germany. Mr. Rozendaal has from the earliest days been associated with aviation, he having been in Germany connected with the Wright machines before taking up the Etrich monoplane. It was Mr. Rozendaal also who engineered the late Mr. Latham's flight in Berlin from the Tempelhofer Feld to Johannisthal in 1909.

AT HENDON AERODROME. - Arrival of the Etrich-Taube monoplane at Hendon during the progress of a race on Saturday.

A STRANGER WITHIN OUR GATES. - The gathering of the pilots and others immediatelly after the arrival from France of the Etrich monoplane at Hendon on Saturday.

THE ETRICH MONOPLANE AT HENDON. - From left to right: Herr Friedrich (pilot) Mr. Claude Grahame-White and Herr Igo Etrich.

AT THE AVRO FLYING SCHOOL, SHOREHAM. - From left to right, Messrs. Geere (Instructor,) Elliot, Mellersh, England, Rolshoven, and (under fuselage) Shaw.

Flight, February 8, 1913.

WHAT THERE WILL BE TO SEE AT OLYMPIA.

THE MACHINES.

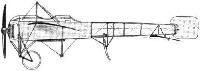

Messrs. A. V. Roe and Co., Ltd.,

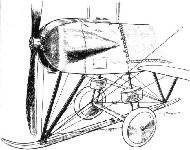

Will be exhibiting on their stand one of the 50-h.p. Gnome-engined passenger-carrying biplanes that have given the War Office such satisfaction. It is interesting to recall, too, that a similar machine was recently supplied to the Portuguese Republic. Light, but strongly-constructed, fast, able to carry weight well, the 50-h.p. Avro biplane has proved itself one of the most successful machines of the day. And it reflects great credit on its designer, Mr. A. V. Roe who, having tasted the bitter sweetness of the pioneer, has gone doggedly ahead to such success. Mr. Roe has the distinction of being the only constructor, we believe, in the world who has designed and constructed successful monoplanes, biplanes, and triplanes.

Flight, February 15, 1913.

A. V. ROE AND CO., LTD.

They are exhibiting a 50-h.p. Avro biplane, fitted with a Gnome engine, and arranged to carry a passenger. Similar machines to the one shown have been supplied in numbers to the Royal Flying Corps, and we have heard that they are extremely popular mounts with those pilots who fly them. Back in last October, too, one of these machines was delivered to the Portuguese Republic, it having been bought by public subscription. Perhaps our readers, or at any rate those of them who follow the progress of things fairly closely, will recall that the first machine of this type to leave the Avro works was supplied to Mr. J. Duigan as far back as in the September of 1911. It is thus quite an old design, but that is not to say that it is old-fashioned - it is as much up-to-date to-day as any machine we could mention.

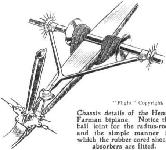

The body of the biplane is an ordinary form of built-up box girder covered with fabric to preserve its lines, and to permit of it travelling through the air with as little disturbance as possible. In front, under a metal cowl, is mounted the 50-h.p. Gnome motor, swung between double bearings and turning a 10 ft. Avro propeller at the rate of 1,200 r.p.m. As our sketch shows, inspection doors are fitted in the side of the body so that the motor may be readily accessible when it requires adjustment. The passenger is seated some distance behind the motor, and his seat is so low down in the body that only the upper part of his head projects through the well-padded cockpit well. Thus he is protected to a great extent from the propeller draught. The pilot is equally as comfortably installed in his cockpit behind and what he is not able to see over the side of the machine, he can obtain a sight of by looking through a window let into the floor between his feet.

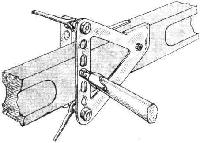

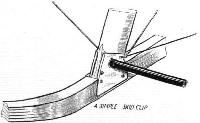

The landing gear resembles, to a great extent, that originated by Nieuport, used on Nieuport monoplanes. There are a few improvements, however, among them being that the laminated cross-springs are assembled to the wheel hubs in a rather more satisfactory way than is employed on the Nieuport. Mr. A. V. Roe, too, has introduced, on this machine, a clever form of skid toe, which, instead of being rigid, can adapt itself to any shock caused by striking an obstacle. Its general details can be seen from the sketch we publish.

The planes. - Span 36 ft., and have a chord measurement or 4 ft. 9 ins. Having a high aspect ratio, they are, as may be supposed, very efficient. Their cross-section has a Phillip-type entry, while it has the peculiarity that the under-surface of that part of the section to the rear of the rear-spar is level in normal horizontal flight. Twelve spruce struts separate the planes, and the bracing is entrusted to stranded-steel cable of generous cross section. The planes warp for the correction of lateral balance.

The tail is formed by a flat surface rectangular in plan, at the back of which are hinged two elevator flaps of a total area of 12 square feet. The rudder is novel, in that it is arranged to slide vertically up the rudder bar, against the compression of a coil spring. It is armoured on the underside by a steel shoe, and this is made to serve the double purpose of rudder and tail skid. The average speed of this Avro biplane may be taken as being 65 m.p.h.

Flight, September 20, 1913.

THE AERIAL DERBY.

PILOTS AND HOW TO RECOGNISE THE MACHINES.

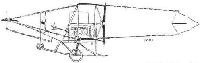

No. 8. The Avro Biplane

is of the tractor type with the engine in front. The fuselage, or body, is covered in throughout its entire length. The main planes have a very pronounced dihedral angle.

THE MACHINES, WITH SOME DETAILS.

No. 8. The Avro biplane, fitted with an 80 h.p. Gnome engine, is similar to the usual Avro type, except that the planes are slightly staggered, and that there are minor modifications in the landing chassis. The span of both upper and lower planes is 36 ft.

It is a tractor biplane, and, as is to be expected from the length of experience of its designer and constructor, Mr. A. V. Roe, it is a fast machine, very stable, and thoroughly reliable.

WHAT THERE WILL BE TO SEE AT OLYMPIA.

THE MACHINES.

Messrs. A. V. Roe and Co., Ltd.,

Will be exhibiting on their stand one of the 50-h.p. Gnome-engined passenger-carrying biplanes that have given the War Office such satisfaction. It is interesting to recall, too, that a similar machine was recently supplied to the Portuguese Republic. Light, but strongly-constructed, fast, able to carry weight well, the 50-h.p. Avro biplane has proved itself one of the most successful machines of the day. And it reflects great credit on its designer, Mr. A. V. Roe who, having tasted the bitter sweetness of the pioneer, has gone doggedly ahead to such success. Mr. Roe has the distinction of being the only constructor, we believe, in the world who has designed and constructed successful monoplanes, biplanes, and triplanes.

Flight, February 15, 1913.

A. V. ROE AND CO., LTD.

They are exhibiting a 50-h.p. Avro biplane, fitted with a Gnome engine, and arranged to carry a passenger. Similar machines to the one shown have been supplied in numbers to the Royal Flying Corps, and we have heard that they are extremely popular mounts with those pilots who fly them. Back in last October, too, one of these machines was delivered to the Portuguese Republic, it having been bought by public subscription. Perhaps our readers, or at any rate those of them who follow the progress of things fairly closely, will recall that the first machine of this type to leave the Avro works was supplied to Mr. J. Duigan as far back as in the September of 1911. It is thus quite an old design, but that is not to say that it is old-fashioned - it is as much up-to-date to-day as any machine we could mention.

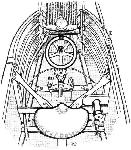

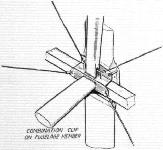

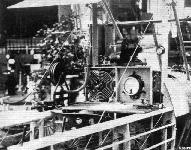

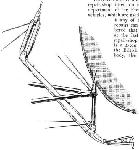

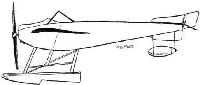

The body of the biplane is an ordinary form of built-up box girder covered with fabric to preserve its lines, and to permit of it travelling through the air with as little disturbance as possible. In front, under a metal cowl, is mounted the 50-h.p. Gnome motor, swung between double bearings and turning a 10 ft. Avro propeller at the rate of 1,200 r.p.m. As our sketch shows, inspection doors are fitted in the side of the body so that the motor may be readily accessible when it requires adjustment. The passenger is seated some distance behind the motor, and his seat is so low down in the body that only the upper part of his head projects through the well-padded cockpit well. Thus he is protected to a great extent from the propeller draught. The pilot is equally as comfortably installed in his cockpit behind and what he is not able to see over the side of the machine, he can obtain a sight of by looking through a window let into the floor between his feet.

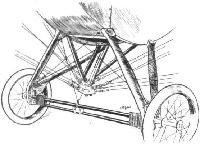

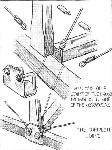

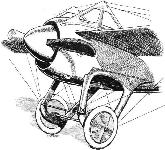

The landing gear resembles, to a great extent, that originated by Nieuport, used on Nieuport monoplanes. There are a few improvements, however, among them being that the laminated cross-springs are assembled to the wheel hubs in a rather more satisfactory way than is employed on the Nieuport. Mr. A. V. Roe, too, has introduced, on this machine, a clever form of skid toe, which, instead of being rigid, can adapt itself to any shock caused by striking an obstacle. Its general details can be seen from the sketch we publish.

The planes. - Span 36 ft., and have a chord measurement or 4 ft. 9 ins. Having a high aspect ratio, they are, as may be supposed, very efficient. Their cross-section has a Phillip-type entry, while it has the peculiarity that the under-surface of that part of the section to the rear of the rear-spar is level in normal horizontal flight. Twelve spruce struts separate the planes, and the bracing is entrusted to stranded-steel cable of generous cross section. The planes warp for the correction of lateral balance.

The tail is formed by a flat surface rectangular in plan, at the back of which are hinged two elevator flaps of a total area of 12 square feet. The rudder is novel, in that it is arranged to slide vertically up the rudder bar, against the compression of a coil spring. It is armoured on the underside by a steel shoe, and this is made to serve the double purpose of rudder and tail skid. The average speed of this Avro biplane may be taken as being 65 m.p.h.

Flight, September 20, 1913.

THE AERIAL DERBY.

PILOTS AND HOW TO RECOGNISE THE MACHINES.

No. 8. The Avro Biplane

is of the tractor type with the engine in front. The fuselage, or body, is covered in throughout its entire length. The main planes have a very pronounced dihedral angle.

THE MACHINES, WITH SOME DETAILS.

No. 8. The Avro biplane, fitted with an 80 h.p. Gnome engine, is similar to the usual Avro type, except that the planes are slightly staggered, and that there are minor modifications in the landing chassis. The span of both upper and lower planes is 36 ft.

It is a tractor biplane, and, as is to be expected from the length of experience of its designer and constructor, Mr. A. V. Roe, it is a fast machine, very stable, and thoroughly reliable.

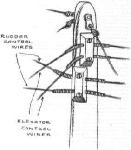

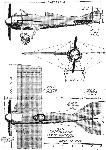

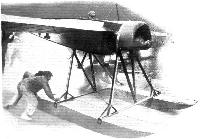

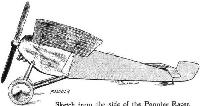

The front section of the Avro biplane, showing the mounting of the 50-h.p. Gnome motor and the inspection doors.

Flight, February 8, 1913.

WHAT THERE WILL BE TO SEE AT OLYMPIA.

THE MACHINES.

Messrs. A. V. Roe and Co., Ltd.,

Will be exhibiting on their stand one of the 50-h.p. Gnome-engined passenger-carrying biplanes that have given the War Office such satisfaction. It is interesting to recall, too, that a similar machine was recently supplied to the Portuguese Republic. Light, but strongly-constructed, fast, able to carry weight well, the 50-h.p. Avro biplane has proved itself one of the most successful machines of the day. And it reflects great credit on its designer, Mr. A. V. Roe who, having tasted the bitter sweetness of the pioneer, has gone doggedly ahead to such success. Mr. Roe has the distinction of being the only constructor, we believe, in the world who has designed and constructed successful monoplanes, biplanes, and triplanes.

WHAT THERE WILL BE TO SEE AT OLYMPIA.

THE MACHINES.

Messrs. A. V. Roe and Co., Ltd.,

Will be exhibiting on their stand one of the 50-h.p. Gnome-engined passenger-carrying biplanes that have given the War Office such satisfaction. It is interesting to recall, too, that a similar machine was recently supplied to the Portuguese Republic. Light, but strongly-constructed, fast, able to carry weight well, the 50-h.p. Avro biplane has proved itself one of the most successful machines of the day. And it reflects great credit on its designer, Mr. A. V. Roe who, having tasted the bitter sweetness of the pioneer, has gone doggedly ahead to such success. Mr. Roe has the distinction of being the only constructor, we believe, in the world who has designed and constructed successful monoplanes, biplanes, and triplanes.

Flight, July 12, 1913.

THE AVRO WATERPLANE.

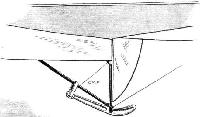

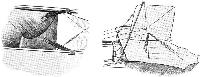

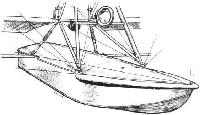

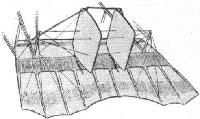

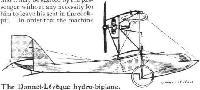

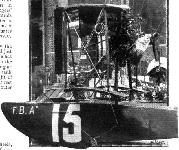

THE new Avro 100 h.p. waterplane, which has been flying so well at Shoreham in the hands of Mr. Raynham, is the first machine to have floats designed by A. V. Roe and Co., their earlier hydroplanes having been built to customers' designs. The result appears to have justified the enterprise, for the machine gets off the water within 60 yards in calm weather, and requires but little more space in a moderate swell.

In general, the Avro waterplane has a close resemblance to the usual Avro type, which is already so well known in the R.F.C. It is, of course, considerably larger throughout, as is rendered necessary by the larger engine power, and by the comparative difficulty of arising from water, as compared with getting off land. Furthermore, there are certain alterations in construction which have been rendered necessary by the altered conditions, as, for example, the substitution of flaps for warping.

The main planes measure 50 ft. in span, as compared with the standard span of 36 ft., and contain five panels instead of three, as in the standard Army type. They have a chord of 6 ft., and the gap between planes is 6 ft. 9 ins. The upper plane only is provided with flaps of 12 ft. 9 ins. span each, increasing in chord towards the tips. These are balanced to pull up as well as down.

The body is supported from the wings in the usual Avro style, with the exception that the planes, instead of detaching from the body itself, detach from a fixed inner cellule having a span of 9 ft., so that the struts at its extremities are immediately above the floats.

These latter are of the pure hydroplane type with 2 steps, and are 14 ft. long x 2 ft. 6 ins. wide, with their inner edges 6 ft. 6 ins. apart. The total buoyancy when submerged is 4,400 lbs., or twice the weight of the machine. The chassis struts are all of steel bound with varnished fabric, and are 14 in number, 7 each side, of which 6 support the cellule from the float, whilst the 7th is carried direct to the engine bearers on the fuselage.

The body itself is rectangular in cross-section with a horizontal top and curved bottom. It tapers at the rear to a vertical rudder post which carries the rudder, and with it a small tail float, which moves with the rudder for steering purposes. The elevators and empennage are of the standard Avro size. The pilot's seat is behind the passenger's, the latter being placed on the centre of gravity of the machine. The engine is enclosed in the usual housing, with a wind-shield for the pilot.

The tractor-screw is an Avro with brass-capped leading edge at the tips, having a diameter of 8.9 ins. and a pitch of 6 ft. The control is by wheel and rudder bar, and is of the usual type.

The weight of the whole machine with full allowance of fuel is just under one ton, and the surface of the main planes being 567 sq. ft. gives a loading of rather under 4 lbs. per sq. ft., and 22 lbs. per h.p. This means, of course, that the machine is not a very high speed one, its estimated velocity being about 48 to 50 miles per hour. This slow speed was adopted as being more likely to be successful, considering the experimental state of our present-day knowledge of hydroplane floats.

It is interesting to know that this machine is already purchased by a private owner, and that several are already on order for the Admiralty.

THE AVRO WATERPLANE.

THE new Avro 100 h.p. waterplane, which has been flying so well at Shoreham in the hands of Mr. Raynham, is the first machine to have floats designed by A. V. Roe and Co., their earlier hydroplanes having been built to customers' designs. The result appears to have justified the enterprise, for the machine gets off the water within 60 yards in calm weather, and requires but little more space in a moderate swell.

In general, the Avro waterplane has a close resemblance to the usual Avro type, which is already so well known in the R.F.C. It is, of course, considerably larger throughout, as is rendered necessary by the larger engine power, and by the comparative difficulty of arising from water, as compared with getting off land. Furthermore, there are certain alterations in construction which have been rendered necessary by the altered conditions, as, for example, the substitution of flaps for warping.

The main planes measure 50 ft. in span, as compared with the standard span of 36 ft., and contain five panels instead of three, as in the standard Army type. They have a chord of 6 ft., and the gap between planes is 6 ft. 9 ins. The upper plane only is provided with flaps of 12 ft. 9 ins. span each, increasing in chord towards the tips. These are balanced to pull up as well as down.

The body is supported from the wings in the usual Avro style, with the exception that the planes, instead of detaching from the body itself, detach from a fixed inner cellule having a span of 9 ft., so that the struts at its extremities are immediately above the floats.

These latter are of the pure hydroplane type with 2 steps, and are 14 ft. long x 2 ft. 6 ins. wide, with their inner edges 6 ft. 6 ins. apart. The total buoyancy when submerged is 4,400 lbs., or twice the weight of the machine. The chassis struts are all of steel bound with varnished fabric, and are 14 in number, 7 each side, of which 6 support the cellule from the float, whilst the 7th is carried direct to the engine bearers on the fuselage.

The body itself is rectangular in cross-section with a horizontal top and curved bottom. It tapers at the rear to a vertical rudder post which carries the rudder, and with it a small tail float, which moves with the rudder for steering purposes. The elevators and empennage are of the standard Avro size. The pilot's seat is behind the passenger's, the latter being placed on the centre of gravity of the machine. The engine is enclosed in the usual housing, with a wind-shield for the pilot.

The tractor-screw is an Avro with brass-capped leading edge at the tips, having a diameter of 8.9 ins. and a pitch of 6 ft. The control is by wheel and rudder bar, and is of the usual type.

The weight of the whole machine with full allowance of fuel is just under one ton, and the surface of the main planes being 567 sq. ft. gives a loading of rather under 4 lbs. per sq. ft., and 22 lbs. per h.p. This means, of course, that the machine is not a very high speed one, its estimated velocity being about 48 to 50 miles per hour. This slow speed was adopted as being more likely to be successful, considering the experimental state of our present-day knowledge of hydroplane floats.

It is interesting to know that this machine is already purchased by a private owner, and that several are already on order for the Admiralty.

Flight, October 11, 1913.

THE WAR OF THE ROSES.

A "WAR of the Roses" was fought out again last week in the form of a race between F. R. Raynham on an Avro biplane, which, of course, was built in Lancashire, and Harold Blackburn on a Blackburn monoplane, a Yorkshire product. The race, which was for a challenge cup offered by the Yorkshire Evening News, started and finished at Leeds, and was held over a circuit of which the chief points were York, Doncaster, Sheffield and Barnsley, a total distance of nearly 100 miles. To see the start about 60,000 people gathered on Moortown on Thursday of last week and both pilots got away from Leeds promptly at 2.14 p.m., Mr. Blackburn with Dr. Christie as passenger and Raynham accompanied by Mr. H. V. Roe. The weather was very bad, the mist making it very difficult to pick up the landmarks and keep on the course, in which respect Blackburn scored over his opponent, as he was more familiar with the country. It will be seen from our table that Raynham had an advantage by the time York was reached, and he was the first away again. At Doncaster, however, he was three seconds behind. Both men got away promptly from the Town Moor, Doncaster, and Blackburn still further improved his position, Raynham being handicapped by being unable to locate the control at Sheffield. He had to make two descents before reaching his destination, and he had the same trouble at the next control, Barnsley. In fact he flew right past it, and when he did descend it was at Dewsbury, some miles away. As it was then hopeless to try and put matters right, he flew direct to Leeds, and arrived some time before Blackburn. Soon after Blackburn's arrival the cup was presented to Dr. Christie, and handed by him to Blackburn. We understand that a return match will be held in Lancashire towards the end of the month, and it is anticipated that the event will become an annual one.

Blackburn. Raynham.

h. m. s. h. m. s.

Start 2 14 0 2 14 0

York arr. 2 39 48 1/5 2 38 59 2/5

,, dep. 3 1 28 4/5 3 0 40

Doncaster arr. 3 33 0 3 33 3

,, dep. 3 51 0 3 5' 3

Sheffield arr. 4 19 50 4 23 50

,, dep. 4 42 0 4 43 0

Barnsley arr. 4 55 23 3/5 -

,, dep. 5 19 0 -

Leeds finish 5 48 0 Disqualifie

Flight, December 6, 1913.

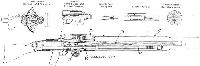

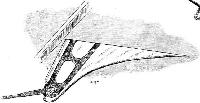

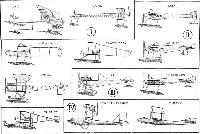

THE 80 H.P. AVRO BIPLANE.

IT is not so very long ago that really high speed was almost invariably associated with the monoplane type of aeroplane; the biplane being looked upon as more suitable for weight carrying at comparatively slow speeds. Things alter rapidly in the aviation world, however, and what seems to be a fantastic dream to-day is an accomplished fact to-morrow.

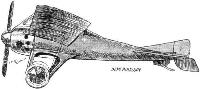

With his new 80 h.p. biplane, Mr. A. V. Roe has proved that it is possible to-day to produce a machine of the biplane type which is as fast as, if not faster than, most monoplanes, and which, moreover, has the advantage that it can be landed at a speed which is very much below its normal flying speed. As a matter of fact the new Avro biplane possesses a speed range of very nearly 50 per cent.

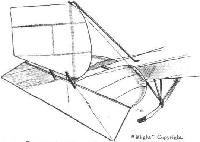

A good idea of the general arrangement should be gained from the accompanying illustrations. It will be seen that the most noticeable departure from the usual Avro practice is the staggering of the main planes, the reason for this no doubt being, that for the same gap and chord extra efficiency is obtained by having the upper plane placed in advance of the lower plane.

In plan the main planes are of the same shape as those of the 50 h.p. non-staggered type, but in section they are naturally of a much smaller camber and angle of incidence.

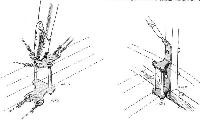

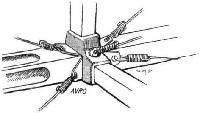

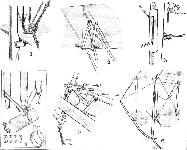

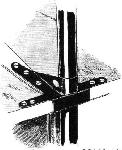

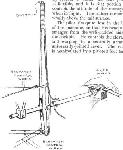

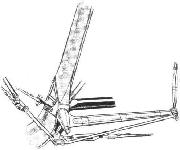

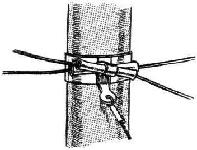

Four pairs of struts of hollow spruce connect the main planes, whilst another two pairs of ash struts connect the upper plane to the fuselage. The method of attaching the lower plane to the fuselage is shown in one of the accompanying sketches. It will be noticed, that a steel lug bolted to the lower longeron has two bolts passing through the plane, but not through the spar inside the inner end rib. Thus the spar is not weakened by piercing, and the wing is prevented from slipping out of the socket partly by the bolts passing inside the rib, and partly by the diagonal wing-bracing cables. Another of our sketches shows the method of joining the inter-plane struts to the main spars in a similar way. It is by close attention to details like these that it has been possible to construct a machine which combines light weight with a high factor of safety. It is really the keynote of the new Avro design that the weight has been cut down to a minimum without undue sacrifice of strength.

The fuselage, which is of rectangular section, is built up of longerons of ash channelled out between the strut attachments for lightness and strengthened by flanges of three-ply wood against bending stresses. The struts and cross-members are of spruce, and diagonal cross-wiring completes the construction of the fuselage.

The pilot's and passenger's seats are arranged tandem fashion, the pilot occupying the rear seat, from where he has an excellent view in all directions, and, owing to the small width of the fuselage - 2 ft. 6 ins. to be exact - he is able to survey the country below without the necessity of leaning out over the side. From the passenger's seat an equally excellent view is obtained, and the wind-shield enables him to make his observations in comfort protected as he is against the flow of air. The controls are of the usual Avro type and consist of a vertical lever pivoted on a longitudinal rocking shaft. A to-and-fro movement operates the elevator, whilst the ailerons are actuated by a side-to-side movement of the hand lever. A foot-bar operates the rudder through double control wires. In this particular machine dual control is not fitted, but could easily be introduced by lengthening the longitudinal rocking shaft.

At the rear the fuselage terminates in a vertical knife's edge to which is hinged the rudder, which is of the usual Avro type; as are also the tail plane and elevators. A swivelling tail skid of the laminated steel spring type protects the tail planes against contact with the ground.

In the front portion of the fuselage and enclosed by one of the neatest aluminium shields we have seen is the engine - an 80 h.p. Gnome - which is carried in double bearings, the front one of which is formed by four tubular extensions of the longerons which converge until they meet on a channel steel ring which carries the front ball-bearing. A small inspection door on each side of the engine housing permits of a general examination of the magneto, carburettor, oil pump, &c, whilst for close inspection the whole engine housing can be removed by undoing the butterfly fasteners by means of which the cowl is attached to the fuselage.

The planes as well as the fuselage are covered with a fabric, which has squares of stronger threads woven into it, so that should the fabric become pierced by a bullet or through any cause, these squares will prevent the fabric from tearing.

One of our sketches illustrates the very neat aileron hinge employed. In order to prevent the air from escaping through the opening between the rear spar and the aileron a strip of wood of triangular section is screwed on to the leading edge of the aileron. The edge of this strip of wood is held tight against the rear spar by means of coil springs on the part of the hinge which is attached to the rear spar, thus making a practically air-tight joint at any angle of the aileron, without causing any undue friction which might otherwise interfere with the free movement of the lateral control.

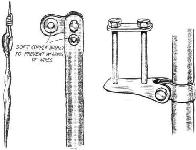

The chassis, it will be noticed, has been slightly altered. Two pairs of V struts of streamlined steel tubes carry on their lower extremities a stout ash skid. Instead of the laminated steel spring axle is fitted a tubular axle which is not connected to the skid, and which carries on its ends the two disc wheels. Two steel tubes run from each end of the axle to a cross-piece, whilst another single tube, pivoted to the lower longeron and passing through the cross-piece of the lower tubes, carries another cross-piece on its lower extremity. Rubber shock absorbers connect the two cross-pieces, thus effecting the springing of the wheels. A neat streamline casing, open at the bottom, encloses the shock absorbers and protects them against oil thrown out from the engine. By sliding the casing up along the tube until the shock absorbers are uncovered, these may readily be adjusted and examined or, if need be, replaced. Stout stranded cables running from the lower ends of the skid struts to the top and bottom of the first pair of inter-plane struts, brace the wings very effectively against drift. During the official tests at Farnborough recently, we understand, the machine, with pilot, passenger and four hours' fuel, climbed 1,000 ft. in 175 mins. Her maximum speed was 80 m.p.h. and her minimum speed 43 m.p.h., thus giving a speed range of nearly 50 per cent.

The weight of the machine with fuel for three hours and a passenger is 1,550 lbs., giving a loading of about 4 1/2 lbs. per square foot.

THE WAR OF THE ROSES.

A "WAR of the Roses" was fought out again last week in the form of a race between F. R. Raynham on an Avro biplane, which, of course, was built in Lancashire, and Harold Blackburn on a Blackburn monoplane, a Yorkshire product. The race, which was for a challenge cup offered by the Yorkshire Evening News, started and finished at Leeds, and was held over a circuit of which the chief points were York, Doncaster, Sheffield and Barnsley, a total distance of nearly 100 miles. To see the start about 60,000 people gathered on Moortown on Thursday of last week and both pilots got away from Leeds promptly at 2.14 p.m., Mr. Blackburn with Dr. Christie as passenger and Raynham accompanied by Mr. H. V. Roe. The weather was very bad, the mist making it very difficult to pick up the landmarks and keep on the course, in which respect Blackburn scored over his opponent, as he was more familiar with the country. It will be seen from our table that Raynham had an advantage by the time York was reached, and he was the first away again. At Doncaster, however, he was three seconds behind. Both men got away promptly from the Town Moor, Doncaster, and Blackburn still further improved his position, Raynham being handicapped by being unable to locate the control at Sheffield. He had to make two descents before reaching his destination, and he had the same trouble at the next control, Barnsley. In fact he flew right past it, and when he did descend it was at Dewsbury, some miles away. As it was then hopeless to try and put matters right, he flew direct to Leeds, and arrived some time before Blackburn. Soon after Blackburn's arrival the cup was presented to Dr. Christie, and handed by him to Blackburn. We understand that a return match will be held in Lancashire towards the end of the month, and it is anticipated that the event will become an annual one.

Blackburn. Raynham.

h. m. s. h. m. s.

Start 2 14 0 2 14 0

York arr. 2 39 48 1/5 2 38 59 2/5

,, dep. 3 1 28 4/5 3 0 40

Doncaster arr. 3 33 0 3 33 3

,, dep. 3 51 0 3 5' 3

Sheffield arr. 4 19 50 4 23 50

,, dep. 4 42 0 4 43 0

Barnsley arr. 4 55 23 3/5 -

,, dep. 5 19 0 -

Leeds finish 5 48 0 Disqualifie

Flight, December 6, 1913.

THE 80 H.P. AVRO BIPLANE.

IT is not so very long ago that really high speed was almost invariably associated with the monoplane type of aeroplane; the biplane being looked upon as more suitable for weight carrying at comparatively slow speeds. Things alter rapidly in the aviation world, however, and what seems to be a fantastic dream to-day is an accomplished fact to-morrow.

With his new 80 h.p. biplane, Mr. A. V. Roe has proved that it is possible to-day to produce a machine of the biplane type which is as fast as, if not faster than, most monoplanes, and which, moreover, has the advantage that it can be landed at a speed which is very much below its normal flying speed. As a matter of fact the new Avro biplane possesses a speed range of very nearly 50 per cent.

A good idea of the general arrangement should be gained from the accompanying illustrations. It will be seen that the most noticeable departure from the usual Avro practice is the staggering of the main planes, the reason for this no doubt being, that for the same gap and chord extra efficiency is obtained by having the upper plane placed in advance of the lower plane.

In plan the main planes are of the same shape as those of the 50 h.p. non-staggered type, but in section they are naturally of a much smaller camber and angle of incidence.

Four pairs of struts of hollow spruce connect the main planes, whilst another two pairs of ash struts connect the upper plane to the fuselage. The method of attaching the lower plane to the fuselage is shown in one of the accompanying sketches. It will be noticed, that a steel lug bolted to the lower longeron has two bolts passing through the plane, but not through the spar inside the inner end rib. Thus the spar is not weakened by piercing, and the wing is prevented from slipping out of the socket partly by the bolts passing inside the rib, and partly by the diagonal wing-bracing cables. Another of our sketches shows the method of joining the inter-plane struts to the main spars in a similar way. It is by close attention to details like these that it has been possible to construct a machine which combines light weight with a high factor of safety. It is really the keynote of the new Avro design that the weight has been cut down to a minimum without undue sacrifice of strength.

The fuselage, which is of rectangular section, is built up of longerons of ash channelled out between the strut attachments for lightness and strengthened by flanges of three-ply wood against bending stresses. The struts and cross-members are of spruce, and diagonal cross-wiring completes the construction of the fuselage.

The pilot's and passenger's seats are arranged tandem fashion, the pilot occupying the rear seat, from where he has an excellent view in all directions, and, owing to the small width of the fuselage - 2 ft. 6 ins. to be exact - he is able to survey the country below without the necessity of leaning out over the side. From the passenger's seat an equally excellent view is obtained, and the wind-shield enables him to make his observations in comfort protected as he is against the flow of air. The controls are of the usual Avro type and consist of a vertical lever pivoted on a longitudinal rocking shaft. A to-and-fro movement operates the elevator, whilst the ailerons are actuated by a side-to-side movement of the hand lever. A foot-bar operates the rudder through double control wires. In this particular machine dual control is not fitted, but could easily be introduced by lengthening the longitudinal rocking shaft.

At the rear the fuselage terminates in a vertical knife's edge to which is hinged the rudder, which is of the usual Avro type; as are also the tail plane and elevators. A swivelling tail skid of the laminated steel spring type protects the tail planes against contact with the ground.

In the front portion of the fuselage and enclosed by one of the neatest aluminium shields we have seen is the engine - an 80 h.p. Gnome - which is carried in double bearings, the front one of which is formed by four tubular extensions of the longerons which converge until they meet on a channel steel ring which carries the front ball-bearing. A small inspection door on each side of the engine housing permits of a general examination of the magneto, carburettor, oil pump, &c, whilst for close inspection the whole engine housing can be removed by undoing the butterfly fasteners by means of which the cowl is attached to the fuselage.

The planes as well as the fuselage are covered with a fabric, which has squares of stronger threads woven into it, so that should the fabric become pierced by a bullet or through any cause, these squares will prevent the fabric from tearing.

One of our sketches illustrates the very neat aileron hinge employed. In order to prevent the air from escaping through the opening between the rear spar and the aileron a strip of wood of triangular section is screwed on to the leading edge of the aileron. The edge of this strip of wood is held tight against the rear spar by means of coil springs on the part of the hinge which is attached to the rear spar, thus making a practically air-tight joint at any angle of the aileron, without causing any undue friction which might otherwise interfere with the free movement of the lateral control.

The chassis, it will be noticed, has been slightly altered. Two pairs of V struts of streamlined steel tubes carry on their lower extremities a stout ash skid. Instead of the laminated steel spring axle is fitted a tubular axle which is not connected to the skid, and which carries on its ends the two disc wheels. Two steel tubes run from each end of the axle to a cross-piece, whilst another single tube, pivoted to the lower longeron and passing through the cross-piece of the lower tubes, carries another cross-piece on its lower extremity. Rubber shock absorbers connect the two cross-pieces, thus effecting the springing of the wheels. A neat streamline casing, open at the bottom, encloses the shock absorbers and protects them against oil thrown out from the engine. By sliding the casing up along the tube until the shock absorbers are uncovered, these may readily be adjusted and examined or, if need be, replaced. Stout stranded cables running from the lower ends of the skid struts to the top and bottom of the first pair of inter-plane struts, brace the wings very effectively against drift. During the official tests at Farnborough recently, we understand, the machine, with pilot, passenger and four hours' fuel, climbed 1,000 ft. in 175 mins. Her maximum speed was 80 m.p.h. and her minimum speed 43 m.p.h., thus giving a speed range of nearly 50 per cent.

The weight of the machine with fuel for three hours and a passenger is 1,550 lbs., giving a loading of about 4 1/2 lbs. per square foot.

Avro 504 in its earliest production form in August 1914 after receiving constant-chord aileron in 1913. This was the original machine fitted with an 80 h.p. Gnome. It was on similar machines that a raid was carried out on the Zeppelin factories at Friedrichshafen, in which Commander Briggs was brought down and captured.

THE YORKSHIRE AIR RACE. - The Avro biplane and the Blackburn monoplane in line just at the moment of getting away.

A couple of snaps of the Blackburn monoplane, taken by Mr. H. V. Roe from the Avro biplane, piloted by Mr. F. P. Raynham in the Yorkshire Air Race between York and Doncaster on October 2nd. Both competitors were well up, and by the photographs it will be seen the weather was extremely wretched with a haze over everything.

Mr. F. P. Raynham on the remarkable new Avro biplane on which he made such splendid speed flights in the competition at Hendon on Saturday. Our picture shows Mr. Raynham at sunset, in the final for the Shell Trophy, which he only missed winning by a "head."

Attachment of inter-plane struts to spar on the Avro biplane, and on the right attachment of lower plane to fuselage.

MR. BLACKBURN FLYING THE BLACKBURN MONOPLANE AT HENDON. - A curious optical illusion is produced, it being difficult, without knowledge, to say whether the machine is travelling towards or away from the spectator.

Flight, March 29, 1913.

FROM THE BRITISH FLYING GROUNDS.

The Blackburn at Leeds.

DURING Easter week Mr. Harold Blackburn has been giving exhibition flights at Leeds. On Good Friday and Saturday he made several ascents on Mr. Foggin's new 50-h.p. Gnome-Blackburn, rising on one occasion to a big altitude. This machine climbs exceedingly quickly and shows a speed of about 60 m.p.h. At noon on Monday Mr. Blackburn made his first ascent, flying around Wakefield and the surrounding country. During the whole afternoon flying was in progress, no less than seven ascents being made by Mr. Blackburn. The final flight was made by Mr. Foggin, who mounted his machine for the first time, and made a splendid flight of nearly 20 mins. duration. He rose to a good altitude, and handled his machine in such excellent style that one could hardly believe that this was his first flight on this type of machine. On Tuesday afternoon Mr. Blackburn made a long flight on Mr. Foggin's machine. He made some very fine banked turns with his usual skill, finishing off with a neat vol plane. The flights were witnessed by hundreds of spectators, who were very enthusiastic in showing their appreciation of the flights of Mr. Blackburn and Mr. Foggin.

Flight, May 3, 1913.

Wakefield-Harrogate Flight.

MR. HAROLD BLACKBURN, flying a new type 50-h.p. Blackburn monoplane, left on Tuesday, last week, the Yorkshire Aerodrome, near Wakefield, at 1.34 p.m., for Harrogate. When he reached Leeds he had the town on his left, and was then flying beautifully at an altitude of 2,000 ft. The machine was fitted with map and compass, and Mr. Blackburn made a perfect course for the Queen's Hotel, in front of the Stray, at Harrogate - the ground used for alighting in the Circuit of Britain. He had never been to Harrogate before, but he arrived exactly at the appointed place at 1.52, about the time expected. The distance is some 18 miles. When he arrived over the Stray, he was flying at all 4,000 ft. altitude, and made a very fine spiral glide down, landing just in front of the Queen's Hotel. The descent took 5 minutes.

Unfortunately when he was about to make the return journey, owing to the enormous crowd which had collected on the Stray, he had the misfortune to smash the machine before getting away. Mr. Blackburn was, however, not hurt in the slightest, although greatly disappointed, as this was his first smash.

Flight, August 2, 1913.

BRITISH NOTES OF THE WEEK.

Mr. H. Blackburn Carries Newspapers.

FOR some time, Mr. Harold Blackburn has been doing quite a lot of flying on his 50 h.p. Blackburn monoplane at Leeds, and on Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday of last week he carried a large bundle of the Yorkshire Evening Post from Leeds to York, landing at the ground of the Yorkshire Agricultural Show. On the first day he had to fight his way through a gale, as is shown by the fact that he took an hour for the trip, whereas on the two following days his time was 35 mins. Each day a large crowd gathered at York to welcome Mr. Blackburn, and needless to say the papers were eagerly sought after as souvenirs.

FROM THE BRITISH FLYING GROUNDS.

The Blackburn at Leeds.

DURING Easter week Mr. Harold Blackburn has been giving exhibition flights at Leeds. On Good Friday and Saturday he made several ascents on Mr. Foggin's new 50-h.p. Gnome-Blackburn, rising on one occasion to a big altitude. This machine climbs exceedingly quickly and shows a speed of about 60 m.p.h. At noon on Monday Mr. Blackburn made his first ascent, flying around Wakefield and the surrounding country. During the whole afternoon flying was in progress, no less than seven ascents being made by Mr. Blackburn. The final flight was made by Mr. Foggin, who mounted his machine for the first time, and made a splendid flight of nearly 20 mins. duration. He rose to a good altitude, and handled his machine in such excellent style that one could hardly believe that this was his first flight on this type of machine. On Tuesday afternoon Mr. Blackburn made a long flight on Mr. Foggin's machine. He made some very fine banked turns with his usual skill, finishing off with a neat vol plane. The flights were witnessed by hundreds of spectators, who were very enthusiastic in showing their appreciation of the flights of Mr. Blackburn and Mr. Foggin.

Flight, May 3, 1913.

Wakefield-Harrogate Flight.

MR. HAROLD BLACKBURN, flying a new type 50-h.p. Blackburn monoplane, left on Tuesday, last week, the Yorkshire Aerodrome, near Wakefield, at 1.34 p.m., for Harrogate. When he reached Leeds he had the town on his left, and was then flying beautifully at an altitude of 2,000 ft. The machine was fitted with map and compass, and Mr. Blackburn made a perfect course for the Queen's Hotel, in front of the Stray, at Harrogate - the ground used for alighting in the Circuit of Britain. He had never been to Harrogate before, but he arrived exactly at the appointed place at 1.52, about the time expected. The distance is some 18 miles. When he arrived over the Stray, he was flying at all 4,000 ft. altitude, and made a very fine spiral glide down, landing just in front of the Queen's Hotel. The descent took 5 minutes.

Unfortunately when he was about to make the return journey, owing to the enormous crowd which had collected on the Stray, he had the misfortune to smash the machine before getting away. Mr. Blackburn was, however, not hurt in the slightest, although greatly disappointed, as this was his first smash.

Flight, August 2, 1913.

BRITISH NOTES OF THE WEEK.

Mr. H. Blackburn Carries Newspapers.

FOR some time, Mr. Harold Blackburn has been doing quite a lot of flying on his 50 h.p. Blackburn monoplane at Leeds, and on Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday of last week he carried a large bundle of the Yorkshire Evening Post from Leeds to York, landing at the ground of the Yorkshire Agricultural Show. On the first day he had to fight his way through a gale, as is shown by the fact that he took an hour for the trip, whereas on the two following days his time was 35 mins. Each day a large crowd gathered at York to welcome Mr. Blackburn, and needless to say the papers were eagerly sought after as souvenirs.

Mr. Harold Blackburn on the Stray, at Harrogate, after his flight from Yorkshire Aerodrome. Starting on the return journey.

Flight, September 6, 1913.

Mr. Blackburn at Bridlington.

THROUGHOUT last week, Mr. Harold Blackburn was giving exhibition flights on his 80 h.p. Blackburn monoplane at Bridlington. Starting from Harrogate, where he had been flying for a few days, on the evening of Monday week, he flew with Dr. M. G. Christie to Bridlington, arriving in the twilight, being received by the Mayor. During the week he took up a number of passengers, and two of them were carried to Filey. Each day Blackburn was flying, and doing some fine banked turns over the bay. On Saturday, after taking up several passengers, he went with Dr. Christie over to Leyburn, a distance of about 75 miles, taking 70 mins. for the trip. Later the two journeyed by way of Ripon to Harrogate, where they landed on the Stray just as it was getting dusk. Flying with the wind this last trip of 40 miles was made in 23 mins. For the past two months Mr. Blackburn has been flying daily, and that the machine has been left out in the open without any protection from the weather speaks well for its sound construction.

Flight, September 20, 1913.

Harrogate to Bridlington and Back.

ON Monday last Mrs. Leigh, of Harrogate, had an exceptional experience in a trip on Mr. Harold Blackburn's monoplane from Harrogate to Bridlington and back, when the return journey was made at a very high speed owing to a terrific following wind, which enabled the distance to be covered in about 40 mins.

Flight, September 27, 1913.

Mr. Harold Blackburn at Harrogate, &c.

ON Monday, last week, Mr. Harold Blackburn, on the 80 h.p. Blackburn monoplane, left Ripon, where he had been giving exhibition flights during the week-end, for Harrogate, taking Dr. Christie, the owner of the machine, as passenger. They landed on the Stray at Harrogate, after doing the flight in 10 mins. at an altitude of about 2,000 ft. At 11.50 Monday morning, Mr. Blackburn started for a trip to Bridlington and back, with Mrs. Leigh as passenger. Mrs. Leigh, who is nearly 70 years of age, is probably one of the oldest ladies who has made such a long trip. They did the 65 miles to Bridlington in a little under the hour, having passed over York and Driffield and encircling the Bay before alighting. The return journey was started at 3.50 in the afternoon, and Harrogate reached 40 mins. afterwards.

The same evening Mr. Harold Blackburn took Dr. Christie up for a flight over the Stray, making some fine banked turns and spirals. On Thursday, Lt.-Gen. Broadwood went for a short passenger trip at Harrogate. They attained an altitude of 4,000 ft., and were flying for about a quarter of an hour. Later on Dr. Christie again accompanied Mr. Blackburn, when they did some fancy flying. Mr. Blackburn was again flying with Dr. Christie on the Friday.

On Saturday, Dr. Christie and Mr. Blackburn left Harrogate for Doncaster, where they arrived after a 40-min. flight. On Saturday afternoon Mr. Blackburn was giving exhibition and passenger flights, taking up seven different passengers during the course of the afternoon. On his first flight with Dr. Christie, he gave a very brilliant display of sharp banked turns, showing the wonderful control he has over the machine. After the exhibition they left just before dusk for Wetherby, where they were staying the night. The distance from Doncaster to Wetherby is about 30 miles. They returned to Doncaster on Sunday noon to give a further exhibition there. During the course of Sunday, about 12 passengers took trips in the machine.

Flight, October 11, 1913.

THE WAR OF THE ROSES.

A "WAR of the Roses" was fought out again last week in the form of a race between F. R. Raynham on an Avro biplane, which, of course, was built in Lancashire, and Harold Blackburn on a Blackburn monoplane, a Yorkshire product. The race, which was for a challenge cup offered by the Yorkshire Evening News, started and finished at Leeds, and was held over a circuit of which the chief points were York, Doncaster, Sheffield and Barnsley, a total distance of nearly 100 miles. To see the start about 60,000 people gathered on Moortown on Thursday of last week and both pilots got away from Leeds promptly at 2.14 p.m., Mr. Blackburn with Dr. Christie as passenger and Raynham accompanied by Mr. H. V. Roe. The weather was very bad, the mist making it very difficult to pick up the landmarks and keep on the course, in which respect Blackburn scored over his opponent, as he was more familiar with the country. It will be seen from our table that Raynham had an advantage by the time York was reached, and he was the first away again. At Doncaster, however, he was three seconds behind. Both men got away promptly from the Town Moor, Doncaster, and Blackburn still further improved his position, Raynham being handicapped by being unable to locate the control at Sheffield. He had to make two descents before reaching his destination, and he had the same trouble at the next control, Barnsley. In fact he flew right past it, and when he did descend it was at Dewsbury, some miles away. As it was then hopeless to try and put matters right, he flew direct to Leeds, and arrived some time before Blackburn. Soon after Blackburn's arrival the cup was presented to Dr. Christie, and handed by him to Blackburn. We understand that a return match will be held in Lancashire towards the end of the month, and it is anticipated that the event will become an annual one.

Blackburn. Raynham.

h. m. s. h. m. s.

Start 2 14 0 2 14 0

York arr. 2 39 48 1/5 2 38 59 2/5

,, dep. 3 1 28 4/5 3 0 40

Doncaster arr. 3 33 0 3 33 3

,, dep. 3 51 0 3 5' 3

Sheffield arr. 4 19 50 4 23 50

,, dep. 4 42 0 4 43 0

Barnsley arr. 4 55 23 3/5 -

,, dep. 5 19 0 -

Leeds finish 5 48 0 Disqualifie

Flight, December 27, 1913.

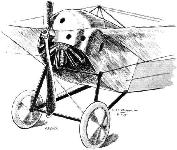

THE 80 H.P. BLACKBURN MONOPLANE.

ALTHOUGH the doings of the new Blackburn monoplane have not received such publicity as doubtlessly would have been the case had the flights been made in the neighbourhood of one of the well-known aerodromes, this machine has nevertheless done a considerable amount of flying in the north of England, and has, it is to be hoped, helped in no small measure to arouse the interest in aviation in that part of the country. A machine of this type, it will be remembered, was delivered to Dr. M. G. Christie in the middle of August and - piloted by Mr. Harold Blackburn - has been flying regulaêly since then, the distance traversed aggregating 1,800 miles, while over 120 passengers have been carried. It was this same machine which Mr. Blackburn flew with Dr. Christie as a passenger in the inter-county air race, for a distance of 100 miles, the Cup being won by Blackburn.

Constructionally this new machine differs considerably from the older type, and is a distinct advance on anything hitherto turned out by the Blackburn firm. The fuselage is streamline in shape and triangular in section, and is built up in the form of a lattice girder. The front part is of English ash, and is covered with sheet aluminium, giving it additional strength and reducing the head resistance. The engine is covered over for about five-eighths of its circumference by a beaten aluminium cowl, which is continued to form a scuttle dash. This effectively prevents the exhaust from the engine reaching either pilot or passenger.

The main planes are rectangular in form, and of a curvature designed to give maximum lift for a minimum drift. The main spars on which the ribs are built up are of the finest selected straight-grained English ash, the spars being machined out of the solid to the most efficient section, and not built up.

The webs are of silver spruce cut out to their true form and built up with cottonwood flanges, forming the ribs to which is attached the fabric. These ribs are strengthened by cottonwood distance pieces where pierced for spars, and are equally spaced by means of leading and trailing edge laths. The whole of the woodwork is well varnished before being covered with fabric, and is strongly braced internally to take the backward thrust imposed on the planes in flight. The planes are covered with finest quality fabric, which is fitted down with split cane beading.

The machine is supported on a very strong chassis composed of two long skids connected up to the fuselage by heavy ash struts. The skids and struts are of specially selected straight long-grained English ash, thoroughly seasoned and designed to withstand alighting on rough uneven ground. To the skids are attached a pair of wheels whose axle is held down by strong elastic shock absorbers, thus preventing shocks due to landing being transmitted to the main frame. The wheels are built up with specially wide hubs to resist any side thrust, and are streamlined with fabric.

The fabric with which the fuselage and planes are covered is very strong compared to its weight. It is carefully stretched on the framework, and is rendered oil- and water-proof by the application of a non-inflammable solution, which impregnates and tightens the fabric and gives a smooth and highly-polished surface.

The standard type of control is fitted, i.e., foot bar for operating rudder, to-and-fro motion of vertical column for operating elevators, and rotating handwheel for lateral balance. All control wires are duplicated.

An 80 h.p. Gnome engine is mounted in front of the fuselage, the supporting plates being of pressed steel. Engine controls are fitted on the right hand of the pilot's seat, and in a convenient position for rapid operation.

The seats for pilot and passenger are arranged in tandem, the passenger in front being situated over the C.G., thus enabling the machine to be flown either with or without a passenger without altering the balance.

For taking the weight of the machine in flight, each front spar is stayed to the chassis by three stranded cables. Three upper tie wires are attached to the front spar from the pylon. The breaking load of the upper wires is not less than two-thirds that of the lift wires. The three warping wires are attached to one main wire passing over pulleys on the rear chassis. The rear spar is, therefore, not bent when the wing is warped, but has an angular movement about the hinge on the fuselage; the corresponding top wires pass over a pulley on the pylon. All cables have a factor of safety of ten, and are spliced and bound with galvanised steel wire.

A Blackburn propeller of 9 feet diameter, built of specially selected laminated walnut, is coupled direct to the engine.

A lifting tail of 30 sq. feet area is fitted. Rudders and elevators are double surfaced.

The accommodation for both pilot and passenger is very comfortable, and a scuttle is fitted up to each seat which prevents the force of the wind from being uncomfortable on the pilot's and passenger's faces. The speed of the machine is 70 m.p.h., and the gross weight 1,500 lbs.

Mr. Blackburn at Bridlington.

THROUGHOUT last week, Mr. Harold Blackburn was giving exhibition flights on his 80 h.p. Blackburn monoplane at Bridlington. Starting from Harrogate, where he had been flying for a few days, on the evening of Monday week, he flew with Dr. M. G. Christie to Bridlington, arriving in the twilight, being received by the Mayor. During the week he took up a number of passengers, and two of them were carried to Filey. Each day Blackburn was flying, and doing some fine banked turns over the bay. On Saturday, after taking up several passengers, he went with Dr. Christie over to Leyburn, a distance of about 75 miles, taking 70 mins. for the trip. Later the two journeyed by way of Ripon to Harrogate, where they landed on the Stray just as it was getting dusk. Flying with the wind this last trip of 40 miles was made in 23 mins. For the past two months Mr. Blackburn has been flying daily, and that the machine has been left out in the open without any protection from the weather speaks well for its sound construction.

Flight, September 20, 1913.

Harrogate to Bridlington and Back.

ON Monday last Mrs. Leigh, of Harrogate, had an exceptional experience in a trip on Mr. Harold Blackburn's monoplane from Harrogate to Bridlington and back, when the return journey was made at a very high speed owing to a terrific following wind, which enabled the distance to be covered in about 40 mins.

Flight, September 27, 1913.

Mr. Harold Blackburn at Harrogate, &c.

ON Monday, last week, Mr. Harold Blackburn, on the 80 h.p. Blackburn monoplane, left Ripon, where he had been giving exhibition flights during the week-end, for Harrogate, taking Dr. Christie, the owner of the machine, as passenger. They landed on the Stray at Harrogate, after doing the flight in 10 mins. at an altitude of about 2,000 ft. At 11.50 Monday morning, Mr. Blackburn started for a trip to Bridlington and back, with Mrs. Leigh as passenger. Mrs. Leigh, who is nearly 70 years of age, is probably one of the oldest ladies who has made such a long trip. They did the 65 miles to Bridlington in a little under the hour, having passed over York and Driffield and encircling the Bay before alighting. The return journey was started at 3.50 in the afternoon, and Harrogate reached 40 mins. afterwards.

The same evening Mr. Harold Blackburn took Dr. Christie up for a flight over the Stray, making some fine banked turns and spirals. On Thursday, Lt.-Gen. Broadwood went for a short passenger trip at Harrogate. They attained an altitude of 4,000 ft., and were flying for about a quarter of an hour. Later on Dr. Christie again accompanied Mr. Blackburn, when they did some fancy flying. Mr. Blackburn was again flying with Dr. Christie on the Friday.

On Saturday, Dr. Christie and Mr. Blackburn left Harrogate for Doncaster, where they arrived after a 40-min. flight. On Saturday afternoon Mr. Blackburn was giving exhibition and passenger flights, taking up seven different passengers during the course of the afternoon. On his first flight with Dr. Christie, he gave a very brilliant display of sharp banked turns, showing the wonderful control he has over the machine. After the exhibition they left just before dusk for Wetherby, where they were staying the night. The distance from Doncaster to Wetherby is about 30 miles. They returned to Doncaster on Sunday noon to give a further exhibition there. During the course of Sunday, about 12 passengers took trips in the machine.

Flight, October 11, 1913.

THE WAR OF THE ROSES.

A "WAR of the Roses" was fought out again last week in the form of a race between F. R. Raynham on an Avro biplane, which, of course, was built in Lancashire, and Harold Blackburn on a Blackburn monoplane, a Yorkshire product. The race, which was for a challenge cup offered by the Yorkshire Evening News, started and finished at Leeds, and was held over a circuit of which the chief points were York, Doncaster, Sheffield and Barnsley, a total distance of nearly 100 miles. To see the start about 60,000 people gathered on Moortown on Thursday of last week and both pilots got away from Leeds promptly at 2.14 p.m., Mr. Blackburn with Dr. Christie as passenger and Raynham accompanied by Mr. H. V. Roe. The weather was very bad, the mist making it very difficult to pick up the landmarks and keep on the course, in which respect Blackburn scored over his opponent, as he was more familiar with the country. It will be seen from our table that Raynham had an advantage by the time York was reached, and he was the first away again. At Doncaster, however, he was three seconds behind. Both men got away promptly from the Town Moor, Doncaster, and Blackburn still further improved his position, Raynham being handicapped by being unable to locate the control at Sheffield. He had to make two descents before reaching his destination, and he had the same trouble at the next control, Barnsley. In fact he flew right past it, and when he did descend it was at Dewsbury, some miles away. As it was then hopeless to try and put matters right, he flew direct to Leeds, and arrived some time before Blackburn. Soon after Blackburn's arrival the cup was presented to Dr. Christie, and handed by him to Blackburn. We understand that a return match will be held in Lancashire towards the end of the month, and it is anticipated that the event will become an annual one.

Blackburn. Raynham.

h. m. s. h. m. s.

Start 2 14 0 2 14 0

York arr. 2 39 48 1/5 2 38 59 2/5

,, dep. 3 1 28 4/5 3 0 40

Doncaster arr. 3 33 0 3 33 3

,, dep. 3 51 0 3 5' 3

Sheffield arr. 4 19 50 4 23 50

,, dep. 4 42 0 4 43 0

Barnsley arr. 4 55 23 3/5 -

,, dep. 5 19 0 -

Leeds finish 5 48 0 Disqualifie

Flight, December 27, 1913.

THE 80 H.P. BLACKBURN MONOPLANE.

ALTHOUGH the doings of the new Blackburn monoplane have not received such publicity as doubtlessly would have been the case had the flights been made in the neighbourhood of one of the well-known aerodromes, this machine has nevertheless done a considerable amount of flying in the north of England, and has, it is to be hoped, helped in no small measure to arouse the interest in aviation in that part of the country. A machine of this type, it will be remembered, was delivered to Dr. M. G. Christie in the middle of August and - piloted by Mr. Harold Blackburn - has been flying regulaêly since then, the distance traversed aggregating 1,800 miles, while over 120 passengers have been carried. It was this same machine which Mr. Blackburn flew with Dr. Christie as a passenger in the inter-county air race, for a distance of 100 miles, the Cup being won by Blackburn.

Constructionally this new machine differs considerably from the older type, and is a distinct advance on anything hitherto turned out by the Blackburn firm. The fuselage is streamline in shape and triangular in section, and is built up in the form of a lattice girder. The front part is of English ash, and is covered with sheet aluminium, giving it additional strength and reducing the head resistance. The engine is covered over for about five-eighths of its circumference by a beaten aluminium cowl, which is continued to form a scuttle dash. This effectively prevents the exhaust from the engine reaching either pilot or passenger.

The main planes are rectangular in form, and of a curvature designed to give maximum lift for a minimum drift. The main spars on which the ribs are built up are of the finest selected straight-grained English ash, the spars being machined out of the solid to the most efficient section, and not built up.

The webs are of silver spruce cut out to their true form and built up with cottonwood flanges, forming the ribs to which is attached the fabric. These ribs are strengthened by cottonwood distance pieces where pierced for spars, and are equally spaced by means of leading and trailing edge laths. The whole of the woodwork is well varnished before being covered with fabric, and is strongly braced internally to take the backward thrust imposed on the planes in flight. The planes are covered with finest quality fabric, which is fitted down with split cane beading.

The machine is supported on a very strong chassis composed of two long skids connected up to the fuselage by heavy ash struts. The skids and struts are of specially selected straight long-grained English ash, thoroughly seasoned and designed to withstand alighting on rough uneven ground. To the skids are attached a pair of wheels whose axle is held down by strong elastic shock absorbers, thus preventing shocks due to landing being transmitted to the main frame. The wheels are built up with specially wide hubs to resist any side thrust, and are streamlined with fabric.

The fabric with which the fuselage and planes are covered is very strong compared to its weight. It is carefully stretched on the framework, and is rendered oil- and water-proof by the application of a non-inflammable solution, which impregnates and tightens the fabric and gives a smooth and highly-polished surface.

The standard type of control is fitted, i.e., foot bar for operating rudder, to-and-fro motion of vertical column for operating elevators, and rotating handwheel for lateral balance. All control wires are duplicated.

An 80 h.p. Gnome engine is mounted in front of the fuselage, the supporting plates being of pressed steel. Engine controls are fitted on the right hand of the pilot's seat, and in a convenient position for rapid operation.

The seats for pilot and passenger are arranged in tandem, the passenger in front being situated over the C.G., thus enabling the machine to be flown either with or without a passenger without altering the balance.

For taking the weight of the machine in flight, each front spar is stayed to the chassis by three stranded cables. Three upper tie wires are attached to the front spar from the pylon. The breaking load of the upper wires is not less than two-thirds that of the lift wires. The three warping wires are attached to one main wire passing over pulleys on the rear chassis. The rear spar is, therefore, not bent when the wing is warped, but has an angular movement about the hinge on the fuselage; the corresponding top wires pass over a pulley on the pylon. All cables have a factor of safety of ten, and are spliced and bound with galvanised steel wire.

A Blackburn propeller of 9 feet diameter, built of specially selected laminated walnut, is coupled direct to the engine.

A lifting tail of 30 sq. feet area is fitted. Rudders and elevators are double surfaced.

The accommodation for both pilot and passenger is very comfortable, and a scuttle is fitted up to each seat which prevents the force of the wind from being uncomfortable on the pilot's and passenger's faces. The speed of the machine is 70 m.p.h., and the gross weight 1,500 lbs.