Книги

Centennial Perspective

J.Herris

Zeppelin-Staaken Aircraft of WW1. Vol 2: R.VI R.30/16 - E.4/20

316

J.Herris - Zeppelin-Staaken Aircraft of WW1. Vol 2: R.VI R.30/16 - E.4/20 /Centennial Perspective/ (48)

Staaken R.XIV with five 245 hp Maybach Mb.IVa engines.The Fokker D.VII at right both gives scale to the Staaken and indicates it is on an operational airfield. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

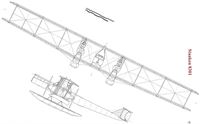

Staaken R.VII

The Staaken R.VII serial R.14/16 reverted to the basic configuration of the R.IV; the same engines were used in the same configuration. A number of details were different, but for practical purposes the R.VII could have been considered an R.IV.

The most important detail differences the R.VII displayed compared to the R.IV included the lack of the upper wing gun positions and the rear fuselage was shorter to make it stiffer and improve its controllability. More minor differences included open cockpits for the flight engineer's cockpit, more wheels on the main landing gear, and the bracing of the tail structure.

The Army accepted the R.VII on June 16, 1917 after it reached an altitude of 3,800 m in 100 minutes with a useful load of 3,600 kg. Delivered to Idflieg on July 3 and assigned to Rfa 501 on July 29, the R.VII was destined to have a brief life. Enroute to the Front, on August 16, 1917 the R.VII was destroyed in a take-off accident; of the crew of 11, only three badly burned men and the starboard flight mechanic survived.

The immediate cause was determined to be failure of the leather clutch of one of the starboard engines. That engine over-sped, then overheated and seized. The remaining starboard engine was not able to maintain propeller speed and the propeller lost thrust. The right wing dropped. The port engines were throttled back in an attempt to level the aircraft, but then it started to descend. The starboard mechanic interpreted the aircraft commander's frantic hand signals as an order to shut off the engines and did so. The right wing again dropped and, being at low altitude, the right wing hit a tree and the R.VII crashed and was destroyed.

The Staaken R.VII serial R.14/16 reverted to the basic configuration of the R.IV; the same engines were used in the same configuration. A number of details were different, but for practical purposes the R.VII could have been considered an R.IV.

The most important detail differences the R.VII displayed compared to the R.IV included the lack of the upper wing gun positions and the rear fuselage was shorter to make it stiffer and improve its controllability. More minor differences included open cockpits for the flight engineer's cockpit, more wheels on the main landing gear, and the bracing of the tail structure.

The Army accepted the R.VII on June 16, 1917 after it reached an altitude of 3,800 m in 100 minutes with a useful load of 3,600 kg. Delivered to Idflieg on July 3 and assigned to Rfa 501 on July 29, the R.VII was destined to have a brief life. Enroute to the Front, on August 16, 1917 the R.VII was destroyed in a take-off accident; of the crew of 11, only three badly burned men and the starboard flight mechanic survived.

The immediate cause was determined to be failure of the leather clutch of one of the starboard engines. That engine over-sped, then overheated and seized. The remaining starboard engine was not able to maintain propeller speed and the propeller lost thrust. The right wing dropped. The port engines were throttled back in an attempt to level the aircraft, but then it started to descend. The starboard mechanic interpreted the aircraft commander's frantic hand signals as an order to shut off the engines and did so. The right wing again dropped and, being at low altitude, the right wing hit a tree and the R.VII crashed and was destroyed.

The Staaken R.VII R.14/15 reverted to the configuration of the R.IV and for practical purposes could have been considered an R.IV. However, whereas the R.IV was the most successful R-plane of the war, the R.VII was destroyed in a take-off accident while enroute to the front on August 16, 1917. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken R.VII being viewed by a crowd of admirers. The nose engines drive a 2-bladed propeller. No camouflage has yet been applied. The radiators for the nacelle engines are separate with the forward radiator above the rear radiator. These unstreamlined radiators generated a lot of drag. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken R.VII (R.14/16) reverted to the configuration of the R.IV although some details were different. Here it is shown at the factory after completion. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Front view of the Staaken R.VII. The people viewing the aircraft give scale to its huge size. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken R.VII on its field photographed from beyond the airfield fence. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The completed Staaken R.VII being admired by VIPs. The nose engines now drive a 4-bladed propeller. The aircraft is resting on its tail skid. The nose engine radiators are prominent and drag producing. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken R.VII with 4-bladed nose engines. The radiators are in out in the slip-stream for maximum cooling. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken R.VII provides the background for a portrait of Staaken staff. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

In flight photo of the Staaken R.VII taken from its starboard engine nacelle toward the tail. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB).

Photo of the port engine nacelle of the Staaken R.VII taken from within the nacelle.The tail is in the left background. (Peter M. Grosz collection/ STDB)

245 liter fuel tanks installed in a Staaken R.VII bomber. Note that each fuel tank has a painted number; it was important for the flight engineer to correctly distribute fuel during the flight to maintain the center of gravity. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken L

The German Navy had an increasing need for a long-range, high-endurance seaplane despite the crash of the R.M.L.1. This military requirement was driven by the increasing success of the British America/Felixstowe flying boats against the German airships. Additional advantages of large seaplanes over airships included being faster and more heavily armed, cheaper, and could use smaller hangars, required fewer support personnel, and had faster response time. The primary task was to be low-altitude reconnaissance for mine-spotting, antisubmarine warfare, and shipping control; the low planned cruising altitude of 500 m demanded greater reliability than any other aircraft type.

Only two companies, Zeppelin-Staaken and Zeppelin-Lindau, delivered R-seaplanes to the German Navy. A report of 26 December 1916 by Oblt.z.S Mans, who had just visited Zeppelin-Lindau to inspect the all-metal Dornier R-type flying boat prototype then under construction, noted that Staaken was planning to propose a new R-type seaplane. This proposal was the Staaken L. The German Navy ordered an example of this aircraft on February 15, 1917, and assigned it the Marine Number 1432. This aircraft was delivered on November 14, 1917.

The Staaken L, designed as a floatplane derivative of the R.VI, was built as a landplane, most likely to facilitate flight-testing at the factory and its delivery flight to Potsdam where the floats were fitted. During taxi trials there a number of modifications were made; a central fin was added to improve stability, standard two-bladed pusher propellers replaced the four-bladed pusher propellers, and the floats were reinforced.

Apart from being a floatplane, the Staaken L was very similar to the R.VI. The wing area was increased and the ailerons were enlarged and balanced. The all-duralumin floats were highly compartmentalized to retain buoyancy in case of damage. The float struts were made of steel. The Navy classed the Staaken L as a bomber, and the lack of cross-bracing between the float struts indicates that carriage of torpedoes was considered a possibility.

The fuel tanks were the 245 liter type used in the R.VI, but instead of the 8 or 10 used in the R.VI, 14 were installed in the Staaken L. Additional fuel was carried in two 150 liter tanks in each nacelle and a 155 liter gravity tank as used in the R.VI. The fuel load enabled a 10-hour endurance at cruise speed compared to the 7-hour endurance standard for the R.VI - which did not have the heavy floats of the L. During evaluation flights it was determined that the endurance of the Staaken L could be extended by cruising on only three engines once the Staaken L had burned enough fuel to reduce its weight to a certain point. This procedure is used by some modern patrol planes for the same reason.

Once the Staaken L was completed it was assigned to the SVK (Seeflugzeug-Versuchs-Kommando - Seaplane Testing Command). A special wooden hangar for the Staaken L was built for the aircraft on piles over the water.

On June 3, 1918 the Staaken L crashed over Warnemunde killing the crew, reportedly after engine failure. The Staaken L was not as stable on the water as the Dornier all-metal R-flying boats; at a 7° heel the tips of the lower wings would touch the water whereas the Dornier R-flying boat accepted a 14° heel before its wingtips would touch the water. However, the Staaken L was based on a proven design and was far easier to produce than the metal Dornier flying boats.

The German Navy had an increasing need for a long-range, high-endurance seaplane despite the crash of the R.M.L.1. This military requirement was driven by the increasing success of the British America/Felixstowe flying boats against the German airships. Additional advantages of large seaplanes over airships included being faster and more heavily armed, cheaper, and could use smaller hangars, required fewer support personnel, and had faster response time. The primary task was to be low-altitude reconnaissance for mine-spotting, antisubmarine warfare, and shipping control; the low planned cruising altitude of 500 m demanded greater reliability than any other aircraft type.

Only two companies, Zeppelin-Staaken and Zeppelin-Lindau, delivered R-seaplanes to the German Navy. A report of 26 December 1916 by Oblt.z.S Mans, who had just visited Zeppelin-Lindau to inspect the all-metal Dornier R-type flying boat prototype then under construction, noted that Staaken was planning to propose a new R-type seaplane. This proposal was the Staaken L. The German Navy ordered an example of this aircraft on February 15, 1917, and assigned it the Marine Number 1432. This aircraft was delivered on November 14, 1917.

The Staaken L, designed as a floatplane derivative of the R.VI, was built as a landplane, most likely to facilitate flight-testing at the factory and its delivery flight to Potsdam where the floats were fitted. During taxi trials there a number of modifications were made; a central fin was added to improve stability, standard two-bladed pusher propellers replaced the four-bladed pusher propellers, and the floats were reinforced.

Apart from being a floatplane, the Staaken L was very similar to the R.VI. The wing area was increased and the ailerons were enlarged and balanced. The all-duralumin floats were highly compartmentalized to retain buoyancy in case of damage. The float struts were made of steel. The Navy classed the Staaken L as a bomber, and the lack of cross-bracing between the float struts indicates that carriage of torpedoes was considered a possibility.

The fuel tanks were the 245 liter type used in the R.VI, but instead of the 8 or 10 used in the R.VI, 14 were installed in the Staaken L. Additional fuel was carried in two 150 liter tanks in each nacelle and a 155 liter gravity tank as used in the R.VI. The fuel load enabled a 10-hour endurance at cruise speed compared to the 7-hour endurance standard for the R.VI - which did not have the heavy floats of the L. During evaluation flights it was determined that the endurance of the Staaken L could be extended by cruising on only three engines once the Staaken L had burned enough fuel to reduce its weight to a certain point. This procedure is used by some modern patrol planes for the same reason.

Once the Staaken L was completed it was assigned to the SVK (Seeflugzeug-Versuchs-Kommando - Seaplane Testing Command). A special wooden hangar for the Staaken L was built for the aircraft on piles over the water.

On June 3, 1918 the Staaken L crashed over Warnemunde killing the crew, reportedly after engine failure. The Staaken L was not as stable on the water as the Dornier all-metal R-flying boats; at a 7° heel the tips of the lower wings would touch the water whereas the Dornier R-flying boat accepted a 14° heel before its wingtips would touch the water. However, the Staaken L was based on a proven design and was far easier to produce than the metal Dornier flying boats.

The Staaken L in its fourth configuration on its handling dolley. The floats are now black. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken L photographed at Warnemunde test centre on 13 February 1918. The Zeppelin-Staaken L was a floatplane conversion of the R.VI with modifications for long-range maritime reconnaissance. It was intended as an interim type pending arrival of Dornier's metal flying boats.

The Staaken L was essentially an R.VI on floats with additional equipment to suit is role as a long-range maritime reconnaissance airplane and bomber. A fixed fin and third rudder were added to improve stability and control, and the ailerons were balanced to reduce control forces. Assigned marine number 1432, it was modified a number of times in light of test-flight results; here it is in the 4th of five configurations. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken L photographed at Warnemunde test centre on 13 February 1918. The Zeppelin-Staaken L was a floatplane conversion of the R.VI with modifications for long-range maritime reconnaissance. It was intended as an interim type pending arrival of Dornier's metal flying boats.

The Staaken L was essentially an R.VI on floats with additional equipment to suit is role as a long-range maritime reconnaissance airplane and bomber. A fixed fin and third rudder were added to improve stability and control, and the ailerons were balanced to reduce control forces. Assigned marine number 1432, it was modified a number of times in light of test-flight results; here it is in the 4th of five configurations. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken L in its third configuration with additional fin on its handling dolley. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken L in its fourth configuration on its handling dolley. The floats are now black. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken L in its third configuration with fixed, central fin and rudder on its handling dolley. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken L in its fourth configuration with fixed, central fin and rudder on handling dolley in its hangar. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken L in its third configuration with fixed, central fin and rudder on its handling dolley. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken L in its fourth configuration on its handling dolley in its hangar. The floats are now black. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Zeppelin-Staaken L, Naval number 1432, in the Potsdam airship hall with the mounted dural floats.

The Staaken L in its fourth configuration and carrying the nickname "Lisbet" on its handling dolley in its hangar at Potsdam. The floats are now black. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken L in its fourth configuration and carrying the nickname "Lisbet" on its handling dolley in its hangar at Potsdam. The floats are now black. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken L in its second configuration being manhandled to the water. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The completed Staaken L with its floats on a handling dolley after it has been rolled out of the factory. This is the second configuration of the aircraft. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken L in its fourth configuration on its handling dolley. The floats are now black. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken L in its fourth configuration with fixed, central fin and rudder on its handling dolley. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken Lin its fourth (second ?) configuration being manhandled on its handling dolley. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The completed Staaken L in its second configuration with no fixed, central fin or rudder. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The completed Staaken L in its second configuration with no fixed, central fin or rudder. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken L in its fourth configuration with fixed, central fin and rudder on the water. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The third configuration of Staaken L takes off from water. A fixed, central fin and rudder have been added to compensate for the destabilizing effects of the floats. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The third configuration of the Staaken L takes off from water. A fixed, central fin and rudder have been added to compensate for the destabilizing effect of the floats. The Staaken L was basically an R.VI adopted to floats for maritime reconnaissance. The prototype eventually crashed and was not adopted by the Navy. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken L in its fourth configuration with fixed, central fin and rudder on the water. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Factory staff by the tail of the Staaken L. Here it is seen in its original configuration as a landplane with no central fin and rudder. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

View of the incomplete Staaken L in its original configuration as a landplane. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken L was essentially an R.VI on floats with additional equipment to suit is role as a long-range maritime reconnaissance airplane. This image shows it under construction with its 14 fuel tanks. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R.VI R.30/16 was powered by four 260 hp Mercedes D.IVa engines and differed from standard production R.VI aircraft in being used as a test-bed for a Brown-Boveri supercharger driven by a separate 120 hp Mercedes D.II engine mounted in the fuselage behind the copilot. With the supercharger operating, ceiling was increased from the usual 12,500' to 19,357' and speed from 130-135 km/h to 160 km/h. In its original configuration it had the standard twin fins and rudders with no central fixed fin. Five-color printed night camouflage fabric covered the fuselage. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R.VI R.30/16 with interim form of national insignia and central fin & rudder. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R.VI R.30/16 with final insignia but before the serial 'R.30' was added. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The exhausts for the supercharger engine are visible behind R.30's cockpit. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R.VI 30/16 prepared for flight. Before installation of supercharger. Oberleutnant Meyer is the pilot.

Staaken R.VI R.30/16 was powered by four 260 hp Mercedes D.IVa engines and differed from standard production R.VI aircraft in being used as a test-bed for a Brown-Boveri supercharger driven by a separate 120 hp Mercedes D.II engine mounted in the fuselage behind the copilot. With the supercharger operating, ceiling was increased from the usual 12,500' to 19,357' and speed from 130-135 km/h to 160 km/h. In its original configuration it had the standard twin fins and rudders with no central fixed fin. Five-color printed night camouflage fabric covered the fuselage. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Zeppelin R.VI production Four-engined Biplane in Flight. (4-250 h.p. Maybach engines.)

The Staaken R.VI (R30/16) was equipped with an additional 120 hp Mercedes D-II engine mounted in the fuselage, driving a Brown-Boveri compressor. The controllable Helix propeller was tested on this aircraft as well.

Staaken R.VI R.30/16 with interim form of national insignia and central fin and rudder takes off. Its designation 'R30' has now been painted on the rear fuselage. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken R.VI (R30/16) was equipped with an additional 120 hp Mercedes D-II engine mounted in the fuselage, driving a Brown-Boveri compressor. The controllable Helix propeller was tested on this aircraft as well.

Staaken R.VI R.30/16 with interim form of national insignia and central fin and rudder takes off. Its designation 'R30' has now been painted on the rear fuselage. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R VI 30/16. Engine mechanic leaving his nacelle cockpit in flight, to mount the ladder that led to a bulged fairing on the upper wing surface fitted with a machinegun. Not all machines of the type had these installations which utilized captured Lewis guns because of their light weight and ease of portability, but they increased the defensive armament considerably and had better fields of fire than the other gun positions on the aircraft.

Experimental controllable pitch propellers were tested on R.30/16 during the war. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Engine nacelle of R.30. It appears the experimental controllable pitch propellers were fitted. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R.VI R.30/16 had an engine failure on May 24, 1918, while performing some tests for Idflieg while flying over Berlin. The engine caught fire and set the lower wing on fire, but R.30 landed safely after diving steeply to blow out the flames, then Dipl-Ing. Noack climbed over the lower wing and extinguished the smoldering fire with a portable fire extinguisher. Experimental controllable pitch propellers were fitted. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R.VI R.30/16 postwar was painted as Fletcher's World for publicity flights. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R.VI R.30/16 postwar with Fletcher's World added. Zeppelin LZ 120 Bodensee flys overhead. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R.VI R.30/16 postwar marked as Fletcher's World for civilian use. Actress Alia Kay is shown in this advertisement. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R.VI R.30/16 Fletcher's World being used as the stage for a dramatic presentation postwar. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R.VI R.33/16 with Hptm. Erich Schilling and officers of Rfa 500. The dog on the nose is Schilling's pet Rodax, carried for good luck. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R.VI of the 33-35/16 production batch. The Staaken below is on the Aviatik factory airfield. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Officers of Rfa 500 with Aviatik-built Staaken R VI 33/16. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R.VI on exhibit for VIPs. The aircraft is covered in hand-painted night lozenge pattern, and the engine nacelles are over-painted dark bluish-gray. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken RVI was the most prolific of the giant R planes with 18 built. They saw service on the Western Front from mid 1917, the first raid against England being on 17 September.

Staaken R.VI on exhibit for VIPs. The aircraft is covered in hand-painted night lozenge pattern, and the engine nacelles are over-painted dark bluish-gray. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken RVI was the most prolific of the giant R planes with 18 built. They saw service on the Western Front from mid 1917, the first raid against England being on 17 September.

Staaken R.VI R.33 under repair. Most of the fabric covering has been removed to facilitate the repair work. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R.VI of the 33-35/16 production batch being built in the Aviatik factory. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R.VI of the 33-35/16 production batch on the Aviatik factory airfield. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R.VI of the R.33-R.35/16 production batch with Aviatik personnel. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R.VI of the R.33-R.35/16 production batch with personnel at the factory. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken-built Staaken R.VI 39/16. The R.39 was the only R-plane to drop 1,000 kg bombs on the UK, dropping them on the nights of 16/17 February, 7/8 March, and 19/20 May 1918. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R.VI 39/16 on the Rfa field with R.26 on the right and another R-plane at left. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Crew of the Staaken R.VI 39/16. The flying crewmen have Paulus parachute belts. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Aviatik-built Staaken R.VI 52/17 the day of its maiden flight on May 7, 1918. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Aviatik-built Staaken R.VI of the R.52-R.54/17 production batch. The nose contours of this batch were different from other R.VI aircraft; the cabin was extended to the front, raising its profile, and the cockpit was open. The nose gun position was raised also. A central fin was also fitted. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Aviatik-built Staaken R.VI of the R.52-R.54/17 production batch on the Rfa field. A central fin was standard. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Aviatik-built Staaken R.VI 52/17 over Leipzig on the way to Rfa 500. The aircraft has its nose gun position at the front of the cabin. It has a central fin and rudder and balanced ailerons. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Pilots' cockpit of Staaken R VI 31/16. The apparent deficiency in the number of instruments is explained by the fact that engine indicators were situated in the mechanics' cockpits in the engine nacelles, whence they kept the commander informed of the condition of their charges by a signalling system, whose battery of lights and switches can be seen in the roof panel. Note the two barographs that recorded height against time on a clockwork-driven paper cylinder, the carriage of these being a normal requirement on all German military aircraft. The dual flying controls with the throttle levers on the pedestal and the tail trim wheel at the rear is a layout that has not changed in principle over 70 years. The hand-operated drum for the trailing wireless aerial can be seen on the left and two mouthpieces and speaking tubes are draped over the navigator's table on the right. Prominently positioned in the centre of the forward windscreen (note stowed curtain at right vertical member for excluding searchlight glare) is the Drexler bank indicator, which used a front view of the aeroplane on a moving card stabilized by a gyroscope revolving at 20,000rpm powered by three-phase current provided by a windmill generator, thus being independent of the aircraft's electrical system.

Pilots' cockpit of Staaken R VI 31/16. The apparent deficiency in the number of instruments is explained by the fact that engine indicators were situated in the mechanics' cockpits in the engine nacelles, whence they kept the commander informed of the condition of their charges by a signalling system, whose battery of lights and switches can be seen in the roof panel in the photo.

On the giant bombers of the R category electrically operated bomb releases were used. Shown is the bomb selector panel on Staaken R VI 30/16. Bombs could be released as required or in sequence, but there was also a salvo or jettison override that allowed all bombs to be dropped at the same time. Each selector switch had an adjacent light which was illuminated by contacts that closed once a bomb had left its rack. The instrument at upper right is an altimeter suspended by three coil springs to prevent errors due to vibration; its dial is calibrated in hundreds of metres, maximum scale being 5km (16,400ft).

Staaken R.VI R.33/16 after a rough landing tore off the landing gear. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Albatros-built Staaken R VI 37/16 burned out after crashing after being hit by French anti-aircraft fire on the night of June 1/2, 1918. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Wreckage of R.31 shot down the night of 15/16 Sep. 18, the second and last R-plane shot down by a Allied fighters, a No.151 Sqdn Camel nightfighter. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Hauptmann Schilling, Kommandeur of Rfa 501, and four members of his crew were killed when Staaken R VI 52/17 crashed into a house south-east of Chimay near Villers la Tour early in the morning of 12 August 1918; they were returning from a short-range operation against Beauvais. Unfamiliar with the more aft position of the pilot's seat compared with previous types and the increased weight of the newly assigned R52, the handling pilot became disorientated when flying blind and lost control. By this time machines of the R category were fitted with quite sophisticated instruments including artificial horizons, but the art of blind flying would not be understood for some years to come.

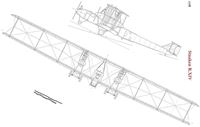

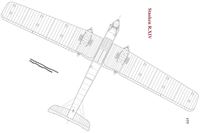

Staaken R.XIV

The next Staaken giant design to be built was designated the Staaken R.XIV; the R.VIII and R.IX designations were used for projects that were not built and the R.X through R.XIII are not known. The R.XIV followed the basic R.VI configuration but the rear nacelle engines were the 350 hp Austro-Daimler V-12. The first R.XIV, R.43/17, flew in March 1918. The nose contours were different than the R.VI because the cockpit was redesigned with an open cockpit to give a better view for the pilots.

The R.43 was built without reduction gears for the propellers to gain performance data to compare with the geared propellers of other R-planes. On April 12, during a flight for its acceptance program, a connecting rod broke in one of its rear V-12 engines. The Austro-Daimler engines were not ready for operational service and the next day they were replaced by 300 hp Basse & Selve BuS.IVa engines. The next flight was scheduled for May 10. However, the Basse & Selve engines were also new designs that were not fully de-bugged and were prone to failure. They in turn were replaced by the proven 245 hp Maybach Mb.IVa engines. However, this required a highly visible modification; a fifth Maybach engine had to be installed in the nose to compensate for their lower power because the R.XIV was substantially heavier than the R.VI which used four of these engines.

Installing the fifth engine in the R.43 took two months; the modified R.43 was ready for acceptance in July. The R.44, which had been built originally with four Basse & Selve engines, did not fly with those engines and was modified with the five Maybach engines. It was delivered in August and the R.45, which was built with the five Maybach engines, was delivered in July. The nacelle tractor propellers for these aircraft did not have reduction gears.

Balanced ailerons were added to the R.XIV design in an attempt to reduce control forces; the balance was kept within the wing outline. Upper wing gun positions were fitted outboard of the engine nacelle centerlines. The nacelles themselves were slimmer than those of the R.VI, mounted higher, and the struts were rearranged. Large spinners were fitted to the tractor propellers.

The R.XIV carried parachutes for all crewmembers; these were carried in external fuselage compartments with lines running to each crewman's station. Six machine guns were carried; one in each upper wing position and two guns in the dorsal and ventral positions. The increased armament reflected the greater Allied use of night-fighters.

The R.45 had its pilots' cockpit moved aft of the wing trailing edge for a better view of the main wheels when landing. Tests were made with wingroot panels open for a better view during landing, but these were covered before R.45 left for the front on August 9, 1918.

During a bombing raid together with R.31, R.45 received a wireless message that it was not to return to its base at Morville, then the home base of Rfa 500, because enemy aircraft over the field meant the landing lights could not be turned on. However, the aircraft commander decided that the low fuel state of R.45 meant that it had to land at Morville. The radio operator notified the field of the decision and requested ground personnel signal with flashlights. The first two landing attempts were not successful; on the third attempt signal flares were fired to better illuminate the field. R.45 landed but missed the runway and hit obstructions that stopped the aircraft. The following morning the obstructions were found to be a water wagon and large ladder on the left and construction material and the roof of a house on the right. Had the R.45 not hit the obstructions, it would have run into a barracks where 60 men were sleeping. R.45 is not thought to have been repaired in time for more missions.

R.43 was one of two R-planes shot down during a bombing mission. On the night of 10/11 August 1918 R.43 was assigned a target not far behind the lines; lit up by searchlights it was attacked by four Sopwith Camels from 151 Squadron, RAF, a specialized night fighter unit that had recently been transferred to France from Home Defence in Britain. R.43 was attacked by four aircraft and shot down by Capt. A.B. Yuille, who got in close under the tail of R.43. R.43 was totally destroyed when a bomb exploded when it hit the ground and all nine crewmen were killed.

The R.XIV, powered by five engines, was not a significant advance over the four-engine R.VI. The fifth engine gave the R.XIV greater reliability in case of engine failure. However, the installation of the nose engine again made the aircraft more likely to catch fire in the event of a crash-landing, and its vibrations affected the more delicate instruments. The smaller diameter and higher RPM of the ungeared propellers also reduced their aerodynamic efficiency. The R.XIV was also heavier than the R.VI for several reasons; it had another engine, its structure was built heavier and stronger for the 350 hp V-12s expected to be used, and various other changes had been made that increased weight.

Staaken R.XIVa

The Staaken R.XIVa was an improved model of the R.XIV, although it was delivered later than the Staaken R.XV The R.XIVa was intended to offer better climb and ceiling than the R.XIV while carrying a greater bombload, so it was given reduction gearing on all engines to improve propeller efficiency. The weight of the R.XIVa was reduced by lightening the structure, removal of the wing machine gun positions, and removal of the bomb bay fairings. A small reduction of the fuselage and engine nacelle cross sectional area contributed to a slight speed increase. The elevators were balanced, a first for a Staaken design.

Idflieg ordered four R.XIVa aircraft, serial numbers R.69 to R.72, from Staaken; these were the last R-planes built by Staaken during the war. The first aircraft, R.69, was built so quickly that not all the modifications could be included. Despite the rushed construction, R.69 was only delivered on Oct. 19, 1918, and did not have time to see operational service. R.70 and R.71 incorporated the modifications and were completed post-war; it is not known if R.72 was completed.

All three aircraft were used to transport money into the Ukraine after the war. R.69 was seized by the IAACC (Inter-Allied Aircraft Control Commission) after landing at Aspern near Vienna on a return flight from the Ukraine. On September 19, 1919 R.70 was seized by Romania when it has to make a forced landing in Bessarabia. R.71 crashed of unknown causes during the summer of 1919.

Schutte-Lanz was given a contract for three R.XIVa aircraft, R.84-R.86, but these were not completed before the Armistice.

Staaken R.XV

The Staaken R.XV was almost identical to the R.XIV; it looked nearly the same and had the same engine configuration, five 245 hp Maybach Mb.IVa engines. The differences are not documented but were probably focused on weight reduction to improve performance because the shape of the nose was slightly refined.

The R.46/17, the first of three R.XV aircraft completed, was ready for its maiden flight on July 25, 1918 and was delivered in August. Both the R.47/17 and R.48/17 were accepted on September 1, 1918. At least two of the aircraft were in time to see service over the Western Front. Postwar, R.47 was shipped to Japan as spoils of victory, and the IAACC found R.48 in the factory in 1919.

The next Staaken giant design to be built was designated the Staaken R.XIV; the R.VIII and R.IX designations were used for projects that were not built and the R.X through R.XIII are not known. The R.XIV followed the basic R.VI configuration but the rear nacelle engines were the 350 hp Austro-Daimler V-12. The first R.XIV, R.43/17, flew in March 1918. The nose contours were different than the R.VI because the cockpit was redesigned with an open cockpit to give a better view for the pilots.

The R.43 was built without reduction gears for the propellers to gain performance data to compare with the geared propellers of other R-planes. On April 12, during a flight for its acceptance program, a connecting rod broke in one of its rear V-12 engines. The Austro-Daimler engines were not ready for operational service and the next day they were replaced by 300 hp Basse & Selve BuS.IVa engines. The next flight was scheduled for May 10. However, the Basse & Selve engines were also new designs that were not fully de-bugged and were prone to failure. They in turn were replaced by the proven 245 hp Maybach Mb.IVa engines. However, this required a highly visible modification; a fifth Maybach engine had to be installed in the nose to compensate for their lower power because the R.XIV was substantially heavier than the R.VI which used four of these engines.

Installing the fifth engine in the R.43 took two months; the modified R.43 was ready for acceptance in July. The R.44, which had been built originally with four Basse & Selve engines, did not fly with those engines and was modified with the five Maybach engines. It was delivered in August and the R.45, which was built with the five Maybach engines, was delivered in July. The nacelle tractor propellers for these aircraft did not have reduction gears.

Balanced ailerons were added to the R.XIV design in an attempt to reduce control forces; the balance was kept within the wing outline. Upper wing gun positions were fitted outboard of the engine nacelle centerlines. The nacelles themselves were slimmer than those of the R.VI, mounted higher, and the struts were rearranged. Large spinners were fitted to the tractor propellers.

The R.XIV carried parachutes for all crewmembers; these were carried in external fuselage compartments with lines running to each crewman's station. Six machine guns were carried; one in each upper wing position and two guns in the dorsal and ventral positions. The increased armament reflected the greater Allied use of night-fighters.

The R.45 had its pilots' cockpit moved aft of the wing trailing edge for a better view of the main wheels when landing. Tests were made with wingroot panels open for a better view during landing, but these were covered before R.45 left for the front on August 9, 1918.

During a bombing raid together with R.31, R.45 received a wireless message that it was not to return to its base at Morville, then the home base of Rfa 500, because enemy aircraft over the field meant the landing lights could not be turned on. However, the aircraft commander decided that the low fuel state of R.45 meant that it had to land at Morville. The radio operator notified the field of the decision and requested ground personnel signal with flashlights. The first two landing attempts were not successful; on the third attempt signal flares were fired to better illuminate the field. R.45 landed but missed the runway and hit obstructions that stopped the aircraft. The following morning the obstructions were found to be a water wagon and large ladder on the left and construction material and the roof of a house on the right. Had the R.45 not hit the obstructions, it would have run into a barracks where 60 men were sleeping. R.45 is not thought to have been repaired in time for more missions.

R.43 was one of two R-planes shot down during a bombing mission. On the night of 10/11 August 1918 R.43 was assigned a target not far behind the lines; lit up by searchlights it was attacked by four Sopwith Camels from 151 Squadron, RAF, a specialized night fighter unit that had recently been transferred to France from Home Defence in Britain. R.43 was attacked by four aircraft and shot down by Capt. A.B. Yuille, who got in close under the tail of R.43. R.43 was totally destroyed when a bomb exploded when it hit the ground and all nine crewmen were killed.

The R.XIV, powered by five engines, was not a significant advance over the four-engine R.VI. The fifth engine gave the R.XIV greater reliability in case of engine failure. However, the installation of the nose engine again made the aircraft more likely to catch fire in the event of a crash-landing, and its vibrations affected the more delicate instruments. The smaller diameter and higher RPM of the ungeared propellers also reduced their aerodynamic efficiency. The R.XIV was also heavier than the R.VI for several reasons; it had another engine, its structure was built heavier and stronger for the 350 hp V-12s expected to be used, and various other changes had been made that increased weight.

Staaken R.XIVa

The Staaken R.XIVa was an improved model of the R.XIV, although it was delivered later than the Staaken R.XV The R.XIVa was intended to offer better climb and ceiling than the R.XIV while carrying a greater bombload, so it was given reduction gearing on all engines to improve propeller efficiency. The weight of the R.XIVa was reduced by lightening the structure, removal of the wing machine gun positions, and removal of the bomb bay fairings. A small reduction of the fuselage and engine nacelle cross sectional area contributed to a slight speed increase. The elevators were balanced, a first for a Staaken design.

Idflieg ordered four R.XIVa aircraft, serial numbers R.69 to R.72, from Staaken; these were the last R-planes built by Staaken during the war. The first aircraft, R.69, was built so quickly that not all the modifications could be included. Despite the rushed construction, R.69 was only delivered on Oct. 19, 1918, and did not have time to see operational service. R.70 and R.71 incorporated the modifications and were completed post-war; it is not known if R.72 was completed.

All three aircraft were used to transport money into the Ukraine after the war. R.69 was seized by the IAACC (Inter-Allied Aircraft Control Commission) after landing at Aspern near Vienna on a return flight from the Ukraine. On September 19, 1919 R.70 was seized by Romania when it has to make a forced landing in Bessarabia. R.71 crashed of unknown causes during the summer of 1919.

Schutte-Lanz was given a contract for three R.XIVa aircraft, R.84-R.86, but these were not completed before the Armistice.

Staaken R.XV

The Staaken R.XV was almost identical to the R.XIV; it looked nearly the same and had the same engine configuration, five 245 hp Maybach Mb.IVa engines. The differences are not documented but were probably focused on weight reduction to improve performance because the shape of the nose was slightly refined.

The R.46/17, the first of three R.XV aircraft completed, was ready for its maiden flight on July 25, 1918 and was delivered in August. Both the R.47/17 and R.48/17 were accepted on September 1, 1918. At least two of the aircraft were in time to see service over the Western Front. Postwar, R.47 was shipped to Japan as spoils of victory, and the IAACC found R.48 in the factory in 1919.

Staaken R.XIVa R.70 of the Deutsche Luft-Reederei in 1919. The aircraft was used to fly newly printed Ukrainian currency from Germany to help finance Ukraine’s war against Rumania and Poland.

The Staaken R.XIV R.43/17 in its original configuration with four Austro-Daimler V-12 engines in push-pull configuration like the earlier R.VI. These engines were not ready for production and were replaced by 300 hp Basse & Selve BuS.IVa engines. These engines were not ready for production either and where in turn replaced. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Zeppelin-Staaken R XIV R.43 as originally completed with four 350 hp Austro-Daimler V12 engines. These engines were not ready for use and R.43 was rebuilt with five 245 hp Maybach Mb.IVa engines. (1917)

The Staaken R.XIV R.43 in its original configuration with four 350 hp Austro-Daimler V-12 engines. These engines were not fully developed and were not ready for production, so had to be replaced. The entire nose was glassed in and the nose gun position was raised. Here the R.43 has drawn an admiring crowd of VIPs. (Peter M. Grosz collection/ STDB)

The next Staaken design to be built was the R.XIV. Originally designed with four 350 hp Austro-Daimler V-12 engines in the configuration of the R.VI, they had to be rebuilt with a fifth engine in the nose after the Austro-Daimler engines proved to be not developed enough for production. Here an R.XIV is shown after modification to five engines. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken R.XIV was an improved version of the R.VI, with four 350hp Austro-Daimler engines. R43/17, the first of the type, flew in February 1918 and the few operational aircraft saw active service in late summer 1918. One aircraft, R43, was operating with RFa 501 on the night of 10/11 August when it was shot down.

The Staaken R.XIV was an improved version of the R.VI, with four 350hp Austro-Daimler engines. R43/17, the first of the type, flew in February 1918 and the few operational aircraft saw active service in late summer 1918. One aircraft, R43, was operating with RFa 501 on the night of 10/11 August when it was shot down.

Staaken R.XIV R.43/17 taking off. On the night of 10/11 August 1918, R.43 was shot down by a Sopwith Camel nightfighter of No. 151 Sqdn, the first R-plane shot down by a fighter. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R.XIV under construction. The serial is partly obscured but appears to be R.43/17. (National Archives)

Staaken R.XIV R.44/17 was completed with five 245 hp Maybach Mb.IVa engines. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R.XIV with five 245 hp Maybach Mb.IVa engines being reviewed. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R.XIV with five 245 hp Maybach Mb.IVa engines. The Fokker D.VII at right both gives scale to the Staaken and indicates it is on an operational airfield. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R.XIV with the Linke-Hofmann works in the background. Linke-Hofmann was also involved in R-plane development but only one, Linke-Hofmann R.I 40/16, was completed and flown. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R.XV R.47/17 on the factory airfield. The white outline of the national insignia has been painted black for night operations. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken R.XV was nearly identical to the earlier R.XIV. Its minor modifications were made to reduce weight. The nose was slightly refined. The IAACC found R.48/17 in the factory in 1919. Note the parachute bags (sewn under the fuselage canvas) and static lines for the dorsal gunners. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken 8301 at the factory in its original configuration for flight testing. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R.XIVa 69/18 with a visiting Argentine commission at Doberitz.

The R.XIVa was an improved R.XIV but the differences were not readily apparent from a photograph. Note the parachute bags seen just under the front of the cabin (sewn beneath the fuselage canvas) and static lines (Zugleine) for pilots. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The R.XIVa was an improved R.XIV but the differences were not readily apparent from a photograph. Note the parachute bags seen just under the front of the cabin (sewn beneath the fuselage canvas) and static lines (Zugleine) for pilots. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R.XIVa 69/18 draws a crowd after landing in the Ukraine. The R.XIVa was an improved R.XIV but used the same powerplants, five 245 hp Maybach Mb.IVa engines. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

A Staaken R.XIVa draws a crowd after landing in the Ukraine. The R.XIVa was an improved R.XIV but used the same powerplants, five 245 hp Maybach Mb.IVa engines. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R.XIVa R69 postwar. The R.XIVa aircraft were not delivered in time for combat. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R.XIVa R.70 in civilian DLR markings. A Ukrainian marking has been applied. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R.XIVa R70 at the factory. R.70 displays the final form of national marking without the white outline for night operations. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R.XIVa R71 at the factory before it crashed. R71 may have been the last R-plane built by Staaken; R72 was ordered but its completion is not confirmed and there are no photos of it. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R.XIVa(Schul) photographed in the factory.

The Staak R.XIVa, completed under license at Schutte-Lanz in Zeesen, had a total of 5 Maybach engines with a total power of 1300 hp.

The Staak R.XIVa, completed under license at Schutte-Lanz in Zeesen, had a total of 5 Maybach engines with a total power of 1300 hp.

Staaken R.XIVa (Schul) 84/18 prior to the fitting of propeller spinners.

Staaken R.XIVa(Schul) was built by Schutte-Lanz, which was given a contract for three aircraft, serial numbers R.84 to R.86. None were completed before the war ended. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R.XIVa(Schul) was built by Schutte-Lanz, which was given a contract for three aircraft, serial numbers R.84 to R.86. None were completed before the war ended. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

"Цеппелин-Штаакен" R-XIV, послевоенный снимок. На переднем плане - группа авиаконструкторов.

Staaken R.XIVa(Schul) R.84/18 with Schutte-Lanz factory staff. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R XIVa R69/18 (???) was built by Schutte-Lanz and powered by five 260 hp Maybach Mb.IVa engines.

Staaken R.XIVa(Schul) R.84/18 with Schutte-Lanz factory staff. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R XIVa R69/18 (???) was built by Schutte-Lanz and powered by five 260 hp Maybach Mb.IVa engines.

Staaken R.XIVa(Schul) photographed with factory staff. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Example of decentralized power arrangement with five 245 h.p. Maybach Mb.IVa engines.

Example of decentralized power arrangement with five 245 h.p. Maybach Mb.IVa engines.

Staaken R.XIVa lined up with Nieuports and Breguets, probably in the Ukraine. In 1919 the German Government allowed DLR to charter a number of aircraft to the Ukraine Government for the transportation of new money for the young state [that the Germans were printing clandestinely]. The Ukraine was at war with Rumania and Poland and wanted to stimulate its economy by introducing a new currency. Some of the DLR aircraft were secretly transferred to the Ukraine and in addition the Ukraine Government chartered the three five-engine Staaken R.XIVa aircraft from DLR. These aircraft had serial numbers R.69, R.70, and R.71 and registration D.129, D.130, and D.131 respecitively. All three were lost. The first, R.69, was confiscated on 29 July by French troops on behalf of the IAACC at the airport of Wien, Aspern. R.71 crashed and burned on 4 August in Oberschlesien. The last Staaken R.XIVa, R.70, commanded by Captain Count Hans Wolf von Harah and with pilots Heinrich Smiltz and Henrig Tretken, was forced down due to fuel problems on 19 September on its way to Kamenets-Podolski. Upon landing the crew was captured by two soldiers of the Rumanian 37th Infantry Regiment. On board the Rumanians found 303 million Griverns (Ukraine roubles), issued 5,6, and 24 October 1918. The Ukraine passengers were sent to a Ukraine-controlled area on the other side of the river Dnestr, while the Germans were imprisoned. The aircraft was repaired by Rumanian aeronautical engineers and flown by Petre Macavei (Technical 1st Lieutenant) and other crew members to the capital of Rumania, Bucharest. On its way the engine caused more trouble, but in the end the aircraft managed to arrive safely. It never flew again, but was stationed at the airport for several years before it was dismantled. Its wooden propellers went to the military museum in Bucharest. Without aircraft, the DLR had to supply new aircraft and offered the Friedrichshafen G.IIIa for Ukraine operations. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Another view of a Staaken R.XIVa. The number of wheels were reduced to reduce weight. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

More detail views of a Staaken R.XIVa. Unlike the R.XIV, the R.XIVa omitted the upper wing gun positions over the nacelles. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R.XIVa(Schul) being promoted as a passenger plane - still with German national insignia. These civilian flights were hardly mentioned in the daily and aeronautical press of the day, and it would appear that they brief and unimportant. The Allies were not enamored having these aircraft flying and Germany could not afford to subsidize them. A parachute shock cord runs from the rear exit to the parachute compartment - in a transport! (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken R.XIV 45/17. Photograph shows the condition of the machine after a night landing at Morville, Belgium. Notice the position of the cockpit behind the wings, unique to the R.45 among Staaken R-planes.

Staaken R.XIVa, perhaps R.71, after crashing. The pilot had to work hard for such an outcome. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Derelict Staaken R-plane on Cologne airfield, February 1919. The airplane has a central fin and rudder. (Peter M. Grosz collection/ STDB)

Derelict Staaken R.XIV after the war. The gun positions in the wing over the engine nacelle are clearly visible. Allied soldiers are doing some sight-seeing. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Staaken Projects

There were several Staaken design projects that were not built. One project was a biplane with 50 m span and 6 m chord; the engines are not known.

In 1917 Idflieg began to think of building R-planes with sufficient performance to permit daylight bombing raids. Consideration of the problem led to the conclusion that the latest technology would be needed, and the thinking converged on all-metal, thick-wing monoplanes with buried engines. Engineers with experience in all-metal construction from the Zeppelin-Lindau factory were transferred to Zeppelin-Staaken and enabled Staaken to design and build all-metal R-planes.

There were at least two other Zeppelin-Staaken projects.

Staaken R.VIII: Three of these aircraft, R.201/16 to R.203/16, were ordered by Idflieg. The Staaken R.VIII was to have been an all-metal aircraft (duralumin) bomber powered by eight engines, either 260 hp Mercedes D.IVa or 245 hp Maybach Mb.IV.

Staaken R.IX: One, R.IX, R.206/16, was projected. This was similar in all respects to the R.VIII.

While design work was done on the R.VIII and R.IX, it is not known if any construction work was done on these projects. It is not known what the R.X to R.XIII might have been.

The last Staaken project as a seaplane assigned Naval Number 8307. It was to be a large seaplane with four 530 hp Benz Bz.VI V-12 engines. It was most likely intended to be similar to the R.XVI but details are not known.

There were several Staaken design projects that were not built. One project was a biplane with 50 m span and 6 m chord; the engines are not known.

In 1917 Idflieg began to think of building R-planes with sufficient performance to permit daylight bombing raids. Consideration of the problem led to the conclusion that the latest technology would be needed, and the thinking converged on all-metal, thick-wing monoplanes with buried engines. Engineers with experience in all-metal construction from the Zeppelin-Lindau factory were transferred to Zeppelin-Staaken and enabled Staaken to design and build all-metal R-planes.

There were at least two other Zeppelin-Staaken projects.

Staaken R.VIII: Three of these aircraft, R.201/16 to R.203/16, were ordered by Idflieg. The Staaken R.VIII was to have been an all-metal aircraft (duralumin) bomber powered by eight engines, either 260 hp Mercedes D.IVa or 245 hp Maybach Mb.IV.

Staaken R.IX: One, R.IX, R.206/16, was projected. This was similar in all respects to the R.VIII.

While design work was done on the R.VIII and R.IX, it is not known if any construction work was done on these projects. It is not known what the R.X to R.XIII might have been.

The last Staaken project as a seaplane assigned Naval Number 8307. It was to be a large seaplane with four 530 hp Benz Bz.VI V-12 engines. It was most likely intended to be similar to the R.XVI but details are not known.

Staaken R.XVI

The Staaken R.XVI was similar in appearance to the original, four-engine configuration of the R.XIV with squared-off nose. The key difference was installation of powerful new V-12 engines in the pusher position.

In May 1917, Idflieg ordered 20 new Benz Bz.VI V-12 engines designed to produce 530 hp. The increased power was intended to improve R-plane performance and increase bombload. When in early 1918 the first engines became available, they were delivered to Aviatik for the R.XVI. Aviatik had already built several R.VI aircraft under license so had the qualifications, and Staaken was already committed to development of all-metal aircraft.

Three of these aircraft, R.49/17 to R.51/17, were ordered from Aviatik as the R.XVI(Av). They were nearly identical to the last series of R.VI aircraft built by Aviatik that had the squared-off nose. The engine nacelle was refined and somewhat enlarged to accommodate the large V-12 engines installed as pushers. The 300 hp Basse & Selve BuS.IVa engine was installed as the tractor engine with a large spinner. However, as in the R.XIV, the Basse & Selve engines had to be replaced due to their poor reliability. The replacement engine was the reliable 220 hp Benz Bz.IV.

Radiators were mounted on the same struts that supported the engine nacelles, with the V-12 engines receiving two radiators. Oil radiators were located at the bottom of each nacelle. Wing area was slightly increased over the earlier aircraft by eliminating the indentations in the trailing edge of the wing for propeller clearance.

Bench testing of the Benz Bz.VI V-12 engine and associated reduction gears was progressing by May 1918; delivery of the R.49 was expected in June. By September the R.49 had made a number of satisfactory flights and there were no problems with the engines. In October R.49 was performing its acceptance flights. During these flights, a heavy landing collapsed the landing gear and the lower wings were badly damaged. R.49 was probably not rebuilt.

R.50 was not completed until early 1919, and was converted into a civil aircraft during construction. The upper wing gun mounts, ladders, and bomb-bay fairing were omitted, which were not necessary for a passenger aircraft and saved weight. The aircraft had 'Aviatik' painted under the lower wings.

The third aircraft of the batch, R.51, was three-quarters complete in January 1919 but was never finished. The R.XVI was the most powerful aircraft built and flown in Germany during WWI.

The Staaken R.XVI was similar in appearance to the original, four-engine configuration of the R.XIV with squared-off nose. The key difference was installation of powerful new V-12 engines in the pusher position.

In May 1917, Idflieg ordered 20 new Benz Bz.VI V-12 engines designed to produce 530 hp. The increased power was intended to improve R-plane performance and increase bombload. When in early 1918 the first engines became available, they were delivered to Aviatik for the R.XVI. Aviatik had already built several R.VI aircraft under license so had the qualifications, and Staaken was already committed to development of all-metal aircraft.

Three of these aircraft, R.49/17 to R.51/17, were ordered from Aviatik as the R.XVI(Av). They were nearly identical to the last series of R.VI aircraft built by Aviatik that had the squared-off nose. The engine nacelle was refined and somewhat enlarged to accommodate the large V-12 engines installed as pushers. The 300 hp Basse & Selve BuS.IVa engine was installed as the tractor engine with a large spinner. However, as in the R.XIV, the Basse & Selve engines had to be replaced due to their poor reliability. The replacement engine was the reliable 220 hp Benz Bz.IV.

Radiators were mounted on the same struts that supported the engine nacelles, with the V-12 engines receiving two radiators. Oil radiators were located at the bottom of each nacelle. Wing area was slightly increased over the earlier aircraft by eliminating the indentations in the trailing edge of the wing for propeller clearance.

Bench testing of the Benz Bz.VI V-12 engine and associated reduction gears was progressing by May 1918; delivery of the R.49 was expected in June. By September the R.49 had made a number of satisfactory flights and there were no problems with the engines. In October R.49 was performing its acceptance flights. During these flights, a heavy landing collapsed the landing gear and the lower wings were badly damaged. R.49 was probably not rebuilt.

R.50 was not completed until early 1919, and was converted into a civil aircraft during construction. The upper wing gun mounts, ladders, and bomb-bay fairing were omitted, which were not necessary for a passenger aircraft and saved weight. The aircraft had 'Aviatik' painted under the lower wings.

The third aircraft of the batch, R.51, was three-quarters complete in January 1919 but was never finished. The R.XVI was the most powerful aircraft built and flown in Germany during WWI.

Staaken R.XVI(Av) 50/17, one of the R-planes completed after 31 January 1919, with company markings.

Staaken R.XVI(Av) in the factory; a mechanic works on the rear starboard engine. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The engine nacelle of a Staaken R.XVI with its Benz V-12 at the Aviatik factory where it was built under license.

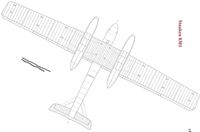

Staaken 8301 & 8303

Staaken's R-floatplane family did not stop with the Staaken L; it had been successful enough that the Navy ordered additional aircraft. In December 1917 the Navy ordered two developments of the Staaken L, given Marine Numbers 8301 and 8302. The next month the Navy ordered two slightly improved aircraft, Marine Numbers 8303 and 8304. These four aircraft were improved developments of the Staaken L with modifications based on the lessons learned from evaluating that aircraft.

These aircraft were very similar to the Staaken L, with the most visible difference being the fuselage was raised above the lower wing. Raising the fuselage and tail higher above the water improved the sea keeping. The forward gun ring was raised level with the top of the fuselage, giving the aircraft a rectangular nose profile.

Windows of Cellon were installed around the nose giving a wide field of view. The nose also had the bomb releases for ten 10 kg bombs stored in two containers along each side of the nose. An anchor winch was installed there for a small anchor hung externally on the nose. A mast antenna enabled the radio to transmit while the aircraft was on the surface and was collapsible for flight.

Other improvements to the 8301/8303 over the Staaken L were derived from the modifications introduced by the newer Staaken landplanes. The wing and control surfaces resembled the R.XIV and the tail had balanced elevators. Becker 2 cm cannon were planned for the rear gun positions. The five-man crew, less then that for the R.VI, reduced the weight to enable the larger fuel load to be carried. Twelve 300-liter fuel tanks gave an endurance of 9-10 hours at cruising speed on all four engines.

In the summer of 1918 the 8301 made its maiden flight as a landplane. The wheeled landing gear resembled that of the standard Staaken R-planes except that the raised fuselage meant the nose landing gear had to be longer. All-duralumin floats were then fitted; these were longer than those on the Staaken L and divided into 12 compartments to minimize flooding in case of damage.

The 8301 and 8302 were based at Warnemunde for evaluation until the Armistice.

The 8303 and 8304 were completed but not delivered; postwar they were found at the Staaken seaplane hangar at Wildpark near Potsdam by the IAACC. The most visible difference between the 8301/8302 and the 8303/8304 is the later aircraft had slightly swept wings. Postwar, the 8301 and perhaps the 8303 and 8304 were used on regular weekend passenger flights between Berlin and Swinemunde.

These Staaken floatplanes are the largest, though not the heaviest, floatplanes ever built.

Staaken's R-floatplane family did not stop with the Staaken L; it had been successful enough that the Navy ordered additional aircraft. In December 1917 the Navy ordered two developments of the Staaken L, given Marine Numbers 8301 and 8302. The next month the Navy ordered two slightly improved aircraft, Marine Numbers 8303 and 8304. These four aircraft were improved developments of the Staaken L with modifications based on the lessons learned from evaluating that aircraft.

These aircraft were very similar to the Staaken L, with the most visible difference being the fuselage was raised above the lower wing. Raising the fuselage and tail higher above the water improved the sea keeping. The forward gun ring was raised level with the top of the fuselage, giving the aircraft a rectangular nose profile.

Windows of Cellon were installed around the nose giving a wide field of view. The nose also had the bomb releases for ten 10 kg bombs stored in two containers along each side of the nose. An anchor winch was installed there for a small anchor hung externally on the nose. A mast antenna enabled the radio to transmit while the aircraft was on the surface and was collapsible for flight.

Other improvements to the 8301/8303 over the Staaken L were derived from the modifications introduced by the newer Staaken landplanes. The wing and control surfaces resembled the R.XIV and the tail had balanced elevators. Becker 2 cm cannon were planned for the rear gun positions. The five-man crew, less then that for the R.VI, reduced the weight to enable the larger fuel load to be carried. Twelve 300-liter fuel tanks gave an endurance of 9-10 hours at cruising speed on all four engines.

In the summer of 1918 the 8301 made its maiden flight as a landplane. The wheeled landing gear resembled that of the standard Staaken R-planes except that the raised fuselage meant the nose landing gear had to be longer. All-duralumin floats were then fitted; these were longer than those on the Staaken L and divided into 12 compartments to minimize flooding in case of damage.

The 8301 and 8302 were based at Warnemunde for evaluation until the Armistice.

The 8303 and 8304 were completed but not delivered; postwar they were found at the Staaken seaplane hangar at Wildpark near Potsdam by the IAACC. The most visible difference between the 8301/8302 and the 8303/8304 is the later aircraft had slightly swept wings. Postwar, the 8301 and perhaps the 8303 and 8304 were used on regular weekend passenger flights between Berlin and Swinemunde.

These Staaken floatplanes are the largest, though not the heaviest, floatplanes ever built.

The Staaken 8301 and 8303 were developments of the earlier Staaken L. The Staaken L had been successful enough that the Navy ordered four aircraft that were developments of it; the 8301 (shown) and 8302, then the 8303 and 8304 that had slight improvements. The most significant improvement was raising the fuselage above the lower wing to get the airframe and tail further out of the water. The nose was also slightly redesigned to give all-around visibility for its maritime reconnaissance role. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

Although not officially accepted for naval service, the display of its marine number shows that this Staaken R (Riesenflugzeug) was ordered by the Navy and completed before the conditions of the Treaty of Versailles came into effect. This machine shows the stage the Germans reached in the development of the giant twin-float seaplane by the end of hostilities. It was operated for a period on a regular basis, from the large lakes between Potsdam and Berlin to Travemiinde, taking Berliners to the seaside in what must have been the first holiday air traffic charters from that city.

Although not officially accepted for naval service, the display of its marine number shows that this Staaken R (Riesenflugzeug) was ordered by the Navy and completed before the conditions of the Treaty of Versailles came into effect. This machine shows the stage the Germans reached in the development of the giant twin-float seaplane by the end of hostilities. It was operated for a period on a regular basis, from the large lakes between Potsdam and Berlin to Travemiinde, taking Berliners to the seaside in what must have been the first holiday air traffic charters from that city.

The Staaken 8301 taking on passengers for a weekend excursion between Berlin and Swinemunde. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken 8301 at the factory in its second configuration with floats being manhandled to take it to the water on its handling dolley. The aircraft has night-type printed lozenge camouflage covering as applied to the Staaken bombers. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken 8303 ready for a water take-off. This aircraft is covered with naval printed camouflage fabric featuring three colors. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken 8301 was built as a land-plane to facilitate flight testing. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken 8301 at the factory in its original configuration for flight testing. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken 8301 at the factory in its original configuration for flight testing. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken 8301 was built as a land-plane to facilitate flight testing. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

The Staaken 8301 as a landplane taking off during its flight evaluations. (Peter M. Grosz collection/STDB)

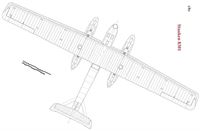

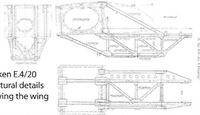

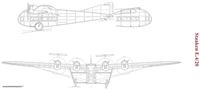

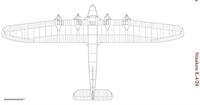

Staaken E.4/20

The all-metal Staaken E.4/20, a result of the desire to build advanced R-planes for daylight bombing missions, was a complete departure from the earlier Staaken designs. Built after the Armistice, it was built as a transport instead of a bomber for the postwar era.

Construction of the Staaken E.4/20 started in May 1919 with the intention of starting passenger service between Friedrichshafen and Berlin. The aircraft was completed on a relaxed schedule on September 30, 1920.

The Staaken E.4/20 was a high-wing cantilever monoplane with four 245 hp Maybach Mb.IVa engines buried in the leading edge of the thick wing. The engines had frontal, car-type radiators and a conventional tail assembly was fitted. The fixed main landing gear had two wheels on each side with a small tail skid. The configuration was very modern and set the style for later passenger airplanes. The structure was all-metal semi-monocoque throughout. This advanced construction was subsequently used for high-performance aircraft to the present day.

The width of the massive wing spar was 1/3 of the chord of the wing and was 1.5 m deep at the wing roots. The leading edge was made of 4 mm thick duraluminium and was attached to the wing spar, as was the trailing edge. The rest of the wing was covered with fabric. The wing spar had oval openings to enable a mechanic to access the engines in flight. Supplementary bracing cables were added to the wing for safety; however, all the normal flight loads could be handled without them. Fuel was carried in two large tanks placed in the leading edge between the engines and four fuel tanks located in the trailing edge structure.

The pilot's open cockpit was located on the upper fuselage just forward of the wing leading edge. Later the nose was cut down and a fully-enclosed cabin with cellon windows was added. The passenger door was in the nose and 12-18 passengers could be carried. A large mail compartment was installed together with toilet, wash-room, and luggage space.

During construction the Staaken E.4/20 was inspected by the IAACC, who permitted Staaken to complete it. The IAACC felt they could not determine the military potential until the aircraft was completed and test flown.

Test pilot Carl Kuring performed a number of very successful test flights as soon as the aircraft was completed. During one flight the aircraft was clocked at 225 km/h, an unprecedented speed for the time for an aircraft of its size. This was a speed that could be achieved by only the fastest contemporary fighters and reconnaissance planes. Staaken had achieved its goal of R-plane performance enabling daylight bombing missions - albeit if the aircraft had been completed as a bomber instead of a passenger plane. Although a design goal was to be able to maintain flight on two engines, the E.4/20 could not do that. It needed fully-feathering propellers to reduce the drag of wind-milling propellers, a technology that was not available at the time. Further test flights were prohibited by the IAACC, which was now convinced the E.4/20 had military potential. The IAACC obstinately prohibited selling or giving away this aircraft, forcing its scrapping on November 21, 1922. The opinion of the company was the IAACC did this to financially damage the Zeppelin-Staaken company to drive it out of business. Unfortunately, this historic aircraft, the forerunner of later large transport and military aircraft, was not preserved for posterity.

The all-metal Staaken E.4/20, a result of the desire to build advanced R-planes for daylight bombing missions, was a complete departure from the earlier Staaken designs. Built after the Armistice, it was built as a transport instead of a bomber for the postwar era.

Construction of the Staaken E.4/20 started in May 1919 with the intention of starting passenger service between Friedrichshafen and Berlin. The aircraft was completed on a relaxed schedule on September 30, 1920.

The Staaken E.4/20 was a high-wing cantilever monoplane with four 245 hp Maybach Mb.IVa engines buried in the leading edge of the thick wing. The engines had frontal, car-type radiators and a conventional tail assembly was fitted. The fixed main landing gear had two wheels on each side with a small tail skid. The configuration was very modern and set the style for later passenger airplanes. The structure was all-metal semi-monocoque throughout. This advanced construction was subsequently used for high-performance aircraft to the present day.

The width of the massive wing spar was 1/3 of the chord of the wing and was 1.5 m deep at the wing roots. The leading edge was made of 4 mm thick duraluminium and was attached to the wing spar, as was the trailing edge. The rest of the wing was covered with fabric. The wing spar had oval openings to enable a mechanic to access the engines in flight. Supplementary bracing cables were added to the wing for safety; however, all the normal flight loads could be handled without them. Fuel was carried in two large tanks placed in the leading edge between the engines and four fuel tanks located in the trailing edge structure.

The pilot's open cockpit was located on the upper fuselage just forward of the wing leading edge. Later the nose was cut down and a fully-enclosed cabin with cellon windows was added. The passenger door was in the nose and 12-18 passengers could be carried. A large mail compartment was installed together with toilet, wash-room, and luggage space.

During construction the Staaken E.4/20 was inspected by the IAACC, who permitted Staaken to complete it. The IAACC felt they could not determine the military potential until the aircraft was completed and test flown.

Test pilot Carl Kuring performed a number of very successful test flights as soon as the aircraft was completed. During one flight the aircraft was clocked at 225 km/h, an unprecedented speed for the time for an aircraft of its size. This was a speed that could be achieved by only the fastest contemporary fighters and reconnaissance planes. Staaken had achieved its goal of R-plane performance enabling daylight bombing missions - albeit if the aircraft had been completed as a bomber instead of a passenger plane. Although a design goal was to be able to maintain flight on two engines, the E.4/20 could not do that. It needed fully-feathering propellers to reduce the drag of wind-milling propellers, a technology that was not available at the time. Further test flights were prohibited by the IAACC, which was now convinced the E.4/20 had military potential. The IAACC obstinately prohibited selling or giving away this aircraft, forcing its scrapping on November 21, 1922. The opinion of the company was the IAACC did this to financially damage the Zeppelin-Staaken company to drive it out of business. Unfortunately, this historic aircraft, the forerunner of later large transport and military aircraft, was not preserved for posterity.

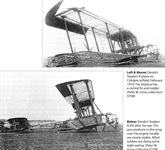

The war-time Staaken bombers took contemporary wood construction to its limit and produced useful operational night bombers. The next step was to develop R-planes with high enough performance to enable daytime bombing, and that required the best technology then available. These were designed during the war but too late for construction. In 1919 Staaken designed the modern all-metal E.4/20 passenger plane development of this research. Above, with open pilot's cockpit and an airspeed indicator on its wing, is the stunning, high-performance result. (PM Grosz Collection/STDB)

The Staaken E.4/20 shows off its very clean lines. (PM Grosz Collection/STDB)

The E.4/20 of 1919-20. Designed by Adolf Rohrbach and built at Staaken: wingspan 31.0 m, length 16.6 m, wing area 106 sq m, all-up weight 8,500 kg, four 260 hp Maybach engines.

The E.4/20 of 1919-20. Designed by Adolf Rohrbach and built at Staaken: wingspan 31.0 m, length 16.6 m, wing area 106 sq m, all-up weight 8,500 kg, four 260 hp Maybach engines.

The Staaken E.4/20 after the cockpit was converted from the open cockpit to a cabin. (PM Grosz Collection/STDB)

Closeup of the main landing gear of the Staaken all-metal E.4/20. The name 'Staaken' has been painted on the fuselage. (PM Grosz Collection/STDB)

Another view of the all-metal Staaken E.4/20 under construction in the factory. (PM Grosz Collection/STDB)

Original configuration of the pilot's cockpit in Staaken E.4/20 in the factory. (PM Grosz Collection/STDB)