Книги

Putnam

C.Barnes

Short Aircraft since 1900

129

C.Barnes - Short Aircraft since 1900 /Putnam/

The Short N.3 Cromarty

Although Oswald Short had been a member of the firm from its very first venture into balloon manufacture, some nine years before Horace Short joined his brothers, he was always regarded by Horace as too young and inexperienced to be allowed a free hand in aeroplane design; even up to the time of Eustace Short’s death in 1932, Oswald was always referred to by his elder brother as ‘The Kid’. This did not prevent him from making his own very competent and continuous contribution to general progress, and in fact sprung floats and pneumatic flotation bags were both his invention, although nearly all patents for new inventions were taken out in the joint names of all three brothers. After war broke out in 1914 it seems that Oswald tried to gain a little more autonomy in design matters, rather against Horace’s wishes, and on the famous occasion in 1916 when Horace at last acceded to John Parker’s request to be allowed to fly, the conditions he stated were: ‘You don’t interfere with the design, and you don’t take any notice of what the bloody Kid says.’

Oswald was evidently keen to build larger, more heavily armed seaplanes, as indicated by the twin-fuselage twin-engined design described in patent No. 3,203 of 1915, already mentioned as the possible basis of a twin-engined bomber. This patent was accepted in the name of H. O. Short alone, indicating that Horace either declined to support it or possibly was not even told of it at the time of application. It is nevertheless a fact that no interest in flyingboats or other large multi-engined seaplanes was ever shown by Horace, in spite of progress by John Porte at Felixstowe and Linton Hope at Southampton; this may have stemmed partly from Porte’s well-known dislike of float seaplanes, which he would have liked to exclude from the Felixstowe establishment altogether. Had he lived longer, Horace might have acknowledged the advantages of flying-boats; soon after his death Short Brothers removed from Eastchurch to concentrate their activities on the Medway, and about this time were asked to undertake production of standard designs, both aeroplanes and flying-boats, as part of the accelerated Ministry of Munitions programme. Early in 1918 they built 100 D.H.9 aeroplanes, some of which were adapted for carrier operation, and also began a batch of 50 Porte flying-boats, initially F.3s and later F.5s. These activities required extensions to the Rochester factory, and a large new erecting shop, No.3, was built on the waterfront upstream of the existing works, involving very heavy excavations of chalk for the site at a cost of some £18,000. A boat-yard at Strood, on the opposite bank of the Medway, was also taken over for the manufacture of F.3 and F.5 hulls, which were towed across to No.3 Shop for assembly of the wings, engines and tail unit.

The first Short-built F.3 boat, N4000, was ready for launching on 15 May, 1918, and since the slipway was not yet finished, the boat was hoisted out by the crane on the adjacent jetty. Thirty-five F.3s had been built by 8 May, 1919, by which time the remainder were nearing completion as improved F.5s of similar size and with the same Rolls-Royce Eagle VIIIs of 360 hp. Short-built Porte boats did well in R.A.F. service, although none arrived in time to see action before the Armistice; during July 1919 two of them (N4041 and N4044, S.620 and S.623) from Felixstowe made a 2,450 miles tour of Scandinavian and Baltic ports; a further batch of 50 F.5s had already been ordered and were well under way by this time, but soon afterwards the last 40 were cancelled as a post-war economy measure; the last of the 10 built, N4839, was first flown by Parker on 23 March, 1920, while the previous one, N4838, delivered to Grain in February, remained there for tests under various loading conditions and was flown for a time with ‘park-bench’ aileron balances. In August 1922, N4839 was temporarily fitted with Napier Lion engines and successfully completed an 18-day cruise from Grain to the Isles of Scilly and back. During 1920 a few F.3s were bought back from the Air Ministry to be reconditioned for export; one of these, Phoenix-built N4400, was sold to the Portuguese Government as C-PAON on 23 April, 1920; another, N4019 (S.607), was fitted out as an air yacht, with a spacious luxury cabin amidships; registered G-EAQT, it was first flown at Rochester on 28 May, 1920, and was then shipped to Botany Bay for the private use of Lebbaeus Hordern, a wealthy resident of Sydney, N.S.W., but before it could be re-erected there his interest faded, and after the hull had been launched no further attempt was made to complete the assembly; the hull finished up as a shelter for local fishermen. Nine of the cancelled new F.5s (S.546-554) were completed for the Imperial Japanese Navy in May 1920 and were shipped to Japan in advance of Colonel the Master of Sempill’s British Naval Air Mission, which arrived in Tokyo in April 1921; the first to be re-erected, S.547, was launched and flown on 30 August, 1921, at Yokosuka by John Parker, who had gone out to Japan with Oswald Short to assist the Mission. The first of the batch, S.546, was reassembled later and reserved for training, together with one new F.5 (Taura No.1) built entirely from local resources at the Hiro Naval Arsenal with assistance from a small team from Short Brothers; later the Aichi Tokei Denki Co of Nagoya built over 50 more F.5s, some of which were still in use at Yokosuka and Sasebo for training as late as 1929. Flying training of I.J.N. personnel was superintended by Major Herbert G. Brackley, who met Oswald Short and John Parker for the first time in Japan; the initial fleet of ten was augmented a year later by three Short-built F.5s with Napier Lion engines; one had a revised bow cockpit mounting a 1-pounder shell-firing gun; the first Lion-engined F.5 was flown at Rochester on 26 April, 1922, by Frank Courtney, deputising for Parker, who returned from Japan a month later. F.5s remained the standard R.A.F. flying-boat, and although the ‘Geddes Axe’ precluded any new orders for them, 24 were returned to Rochester for major overhaul under contract No. 412569/23, and the first of these (N4046) was passed out by Parker on 10 January, 1924.

<...>

Although Oswald Short had been a member of the firm from its very first venture into balloon manufacture, some nine years before Horace Short joined his brothers, he was always regarded by Horace as too young and inexperienced to be allowed a free hand in aeroplane design; even up to the time of Eustace Short’s death in 1932, Oswald was always referred to by his elder brother as ‘The Kid’. This did not prevent him from making his own very competent and continuous contribution to general progress, and in fact sprung floats and pneumatic flotation bags were both his invention, although nearly all patents for new inventions were taken out in the joint names of all three brothers. After war broke out in 1914 it seems that Oswald tried to gain a little more autonomy in design matters, rather against Horace’s wishes, and on the famous occasion in 1916 when Horace at last acceded to John Parker’s request to be allowed to fly, the conditions he stated were: ‘You don’t interfere with the design, and you don’t take any notice of what the bloody Kid says.’

Oswald was evidently keen to build larger, more heavily armed seaplanes, as indicated by the twin-fuselage twin-engined design described in patent No. 3,203 of 1915, already mentioned as the possible basis of a twin-engined bomber. This patent was accepted in the name of H. O. Short alone, indicating that Horace either declined to support it or possibly was not even told of it at the time of application. It is nevertheless a fact that no interest in flyingboats or other large multi-engined seaplanes was ever shown by Horace, in spite of progress by John Porte at Felixstowe and Linton Hope at Southampton; this may have stemmed partly from Porte’s well-known dislike of float seaplanes, which he would have liked to exclude from the Felixstowe establishment altogether. Had he lived longer, Horace might have acknowledged the advantages of flying-boats; soon after his death Short Brothers removed from Eastchurch to concentrate their activities on the Medway, and about this time were asked to undertake production of standard designs, both aeroplanes and flying-boats, as part of the accelerated Ministry of Munitions programme. Early in 1918 they built 100 D.H.9 aeroplanes, some of which were adapted for carrier operation, and also began a batch of 50 Porte flying-boats, initially F.3s and later F.5s. These activities required extensions to the Rochester factory, and a large new erecting shop, No.3, was built on the waterfront upstream of the existing works, involving very heavy excavations of chalk for the site at a cost of some £18,000. A boat-yard at Strood, on the opposite bank of the Medway, was also taken over for the manufacture of F.3 and F.5 hulls, which were towed across to No.3 Shop for assembly of the wings, engines and tail unit.

The first Short-built F.3 boat, N4000, was ready for launching on 15 May, 1918, and since the slipway was not yet finished, the boat was hoisted out by the crane on the adjacent jetty. Thirty-five F.3s had been built by 8 May, 1919, by which time the remainder were nearing completion as improved F.5s of similar size and with the same Rolls-Royce Eagle VIIIs of 360 hp. Short-built Porte boats did well in R.A.F. service, although none arrived in time to see action before the Armistice; during July 1919 two of them (N4041 and N4044, S.620 and S.623) from Felixstowe made a 2,450 miles tour of Scandinavian and Baltic ports; a further batch of 50 F.5s had already been ordered and were well under way by this time, but soon afterwards the last 40 were cancelled as a post-war economy measure; the last of the 10 built, N4839, was first flown by Parker on 23 March, 1920, while the previous one, N4838, delivered to Grain in February, remained there for tests under various loading conditions and was flown for a time with ‘park-bench’ aileron balances. In August 1922, N4839 was temporarily fitted with Napier Lion engines and successfully completed an 18-day cruise from Grain to the Isles of Scilly and back. During 1920 a few F.3s were bought back from the Air Ministry to be reconditioned for export; one of these, Phoenix-built N4400, was sold to the Portuguese Government as C-PAON on 23 April, 1920; another, N4019 (S.607), was fitted out as an air yacht, with a spacious luxury cabin amidships; registered G-EAQT, it was first flown at Rochester on 28 May, 1920, and was then shipped to Botany Bay for the private use of Lebbaeus Hordern, a wealthy resident of Sydney, N.S.W., but before it could be re-erected there his interest faded, and after the hull had been launched no further attempt was made to complete the assembly; the hull finished up as a shelter for local fishermen. Nine of the cancelled new F.5s (S.546-554) were completed for the Imperial Japanese Navy in May 1920 and were shipped to Japan in advance of Colonel the Master of Sempill’s British Naval Air Mission, which arrived in Tokyo in April 1921; the first to be re-erected, S.547, was launched and flown on 30 August, 1921, at Yokosuka by John Parker, who had gone out to Japan with Oswald Short to assist the Mission. The first of the batch, S.546, was reassembled later and reserved for training, together with one new F.5 (Taura No.1) built entirely from local resources at the Hiro Naval Arsenal with assistance from a small team from Short Brothers; later the Aichi Tokei Denki Co of Nagoya built over 50 more F.5s, some of which were still in use at Yokosuka and Sasebo for training as late as 1929. Flying training of I.J.N. personnel was superintended by Major Herbert G. Brackley, who met Oswald Short and John Parker for the first time in Japan; the initial fleet of ten was augmented a year later by three Short-built F.5s with Napier Lion engines; one had a revised bow cockpit mounting a 1-pounder shell-firing gun; the first Lion-engined F.5 was flown at Rochester on 26 April, 1922, by Frank Courtney, deputising for Parker, who returned from Japan a month later. F.5s remained the standard R.A.F. flying-boat, and although the ‘Geddes Axe’ precluded any new orders for them, 24 were returned to Rochester for major overhaul under contract No. 412569/23, and the first of these (N4046) was passed out by Parker on 10 January, 1924.

<...>

Short Brothers' first F.3 flying boat, N4000, ready for launching on 15 May, 1918: No.3 Shop was incomplete, and its slipway had not yet built, so the crane had to be used.

The antepenultimate Rochester-built F.3, N4033, on the newly-built slipway at No.3 Shop on 26 February, 1919, showing its horn-balanced ailerons.

Napier Lion engines were installed in the last three F.5s supplied to Japan from Rochester in April 1922, and another Lion-engined F.5 completed an 18-day cruise from Grain to the Scilly Isles and back in August 1922, an event in which the Cromarty came to grief at St Mary’s.

9085, first of ten 184 Type B seaplanes built by Mann, Egerton & Co at Norwich in 1916. Note the very long, inversely-tapered ailerons fitted on the upper wings only.

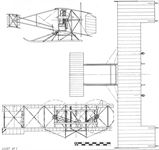

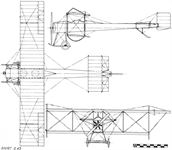

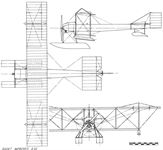

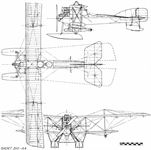

Short Biplane No. 1

Immediately after his flight with Wilbur Wright at Le Mans in November 1908, Frank McClean had to go to China to observe a solar eclipse; from his ship he wrote to Horace Short (whom he had met only once), saying, in effect, ‘Build me an aeroplane’ with no other conditions stipulated. Frank McClean was a leading light in the Aero Club, and his very generous patronage was a principal source of the Shorts’ early business. Even before the Wright brothers awarded their licence, Horace Short began designing Short No. 1 at Battersea, and after only four weeks of manufacturing effort enough progress had been made for the uncovered airframe to be exhibited in March 1909 at the first Aero and Motor Boat Show at Olympia. Although superficially similar to the Wright Flyer, it differed in principle and in detail, having a rigidly braced three-bay cellule with flexible trailing-edge extensions at the outer bays, where the chord was increased from 6 ft 6 in to 10 ft 6 in over a span of 6 ft at each wing-tip. The mainplanes were slightly staggered and double-surfaced, with sharp leading edges and pronounced camber, the profile being derived from steam-turbine experience. A similarly cambered biplane elevator was carried in front and there was no tail; instead, there was a central fixed fin between the front elevators, and four rudders were pivoted in pairs from the wing-tip extensions. Control was by two hand levers and a foot bar, the left-hand lever controlling the elevator, the right-hand the rudders and the foot control warping the flexible wing extensions. The single engine drove two 10 ft diameter laminated spruce propellers mounted aft of the wing through a chain drive; at first it was intended that the port chain should be crossed to effect counter-rotation, as in the Wright system, but this could not easily be done without infringing the Wright patents. The landing-gear comprised a pair of robust skids carried by numerous struts; the chassis had no wheels, and a starting rail was used for take-off. The uncovered airframe was inspected by the Prince of Wales (later King George V) when he visited Short Brothers’ stand at Olympia on 26 March, 1909.

Except for the ash skids, the machine was built entirely of spruce, and the spars incorporated bolted flitch joints to enable the wing assembly to be dismantled into three sections for transport; the covering was ‘Continental’ balloon fabric, already rubberised, but difficulty arose in attaching it to the concave undersurfaces, and covering was still unfinished at Shellbeach in May. A Wright-type Bariquand & Marre engine of 30 hp was on order, but had not been delivered by July, when Frank McClean got back from China, and he was so anxious to begin flying that he bought a second-hand Nordenfelt car from which he removed the engine; this was rated at 30 hp, but weighed over 600 lb when installed, and in the first trials in September it failed to propel the biplane even as far as the end of the starting rail, after which it was transferred to Short-Wright No. 3, but with no better success. The Bariquand & Marre engine arrived in October, and with this McClean almost got No. 1 airborne during three attempts on 2, 3 and 6 November, but on the last occasion he pulled up the elevator to its limit and the machine stalled in a nose-up attitude off the end of the rail, slewed sideways, demolishing its chassis, and fell over backwards, so breaking both propellers. It has been suggested that it was repaired and successfully flown later with a 60 hp Green engine, but in later years this report was denied by both Sir Francis McClean and Lord Brabazon. Virtually nothing was recorded about Short No. 1 in the Press of the day because, to quote the editor of the first edition of the Aero Manual, published in 1909: ‘Messrs Short Bros are pursuing a policy of reticence, and up to the time when this book has gone to press have asked us not to make public any information about their aeroplanes.’

Span 40 ft (12 2 m); length 24 ft 7 in (7-5 m); area 576 sq ft (53-5 m2); loaded weight 1,200 lb (545 kg).

Immediately after his flight with Wilbur Wright at Le Mans in November 1908, Frank McClean had to go to China to observe a solar eclipse; from his ship he wrote to Horace Short (whom he had met only once), saying, in effect, ‘Build me an aeroplane’ with no other conditions stipulated. Frank McClean was a leading light in the Aero Club, and his very generous patronage was a principal source of the Shorts’ early business. Even before the Wright brothers awarded their licence, Horace Short began designing Short No. 1 at Battersea, and after only four weeks of manufacturing effort enough progress had been made for the uncovered airframe to be exhibited in March 1909 at the first Aero and Motor Boat Show at Olympia. Although superficially similar to the Wright Flyer, it differed in principle and in detail, having a rigidly braced three-bay cellule with flexible trailing-edge extensions at the outer bays, where the chord was increased from 6 ft 6 in to 10 ft 6 in over a span of 6 ft at each wing-tip. The mainplanes were slightly staggered and double-surfaced, with sharp leading edges and pronounced camber, the profile being derived from steam-turbine experience. A similarly cambered biplane elevator was carried in front and there was no tail; instead, there was a central fixed fin between the front elevators, and four rudders were pivoted in pairs from the wing-tip extensions. Control was by two hand levers and a foot bar, the left-hand lever controlling the elevator, the right-hand the rudders and the foot control warping the flexible wing extensions. The single engine drove two 10 ft diameter laminated spruce propellers mounted aft of the wing through a chain drive; at first it was intended that the port chain should be crossed to effect counter-rotation, as in the Wright system, but this could not easily be done without infringing the Wright patents. The landing-gear comprised a pair of robust skids carried by numerous struts; the chassis had no wheels, and a starting rail was used for take-off. The uncovered airframe was inspected by the Prince of Wales (later King George V) when he visited Short Brothers’ stand at Olympia on 26 March, 1909.

Except for the ash skids, the machine was built entirely of spruce, and the spars incorporated bolted flitch joints to enable the wing assembly to be dismantled into three sections for transport; the covering was ‘Continental’ balloon fabric, already rubberised, but difficulty arose in attaching it to the concave undersurfaces, and covering was still unfinished at Shellbeach in May. A Wright-type Bariquand & Marre engine of 30 hp was on order, but had not been delivered by July, when Frank McClean got back from China, and he was so anxious to begin flying that he bought a second-hand Nordenfelt car from which he removed the engine; this was rated at 30 hp, but weighed over 600 lb when installed, and in the first trials in September it failed to propel the biplane even as far as the end of the starting rail, after which it was transferred to Short-Wright No. 3, but with no better success. The Bariquand & Marre engine arrived in October, and with this McClean almost got No. 1 airborne during three attempts on 2, 3 and 6 November, but on the last occasion he pulled up the elevator to its limit and the machine stalled in a nose-up attitude off the end of the rail, slewed sideways, demolishing its chassis, and fell over backwards, so breaking both propellers. It has been suggested that it was repaired and successfully flown later with a 60 hp Green engine, but in later years this report was denied by both Sir Francis McClean and Lord Brabazon. Virtually nothing was recorded about Short No. 1 in the Press of the day because, to quote the editor of the first edition of the Aero Manual, published in 1909: ‘Messrs Short Bros are pursuing a policy of reticence, and up to the time when this book has gone to press have asked us not to make public any information about their aeroplanes.’

Span 40 ft (12 2 m); length 24 ft 7 in (7-5 m); area 576 sq ft (53-5 m2); loaded weight 1,200 lb (545 kg).

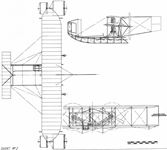

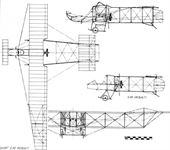

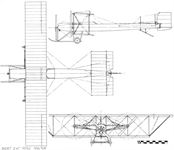

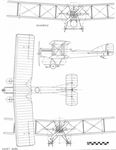

Short Biplane No. 2

The second biplane designed by Horace Short was ordered in April 1909 by J. T. C. Moore-Brabazon, specifically for his attempt to win the Daily Mail’s prize of £1,000 for the first flight of one mile in a closed circuit by a British pilot in an all-British aeroplane. Moore-Brabazon had built himself a biplane as early as 1907, for which Short Brothers had manufactured various components, although they had no part in its design. When it failed to fly at Brooklands, on the meagre power of a single 12 hp Buchet engine, he abandoned it and went to France, where he bought three Voisins in succession, the third being the E.N.V.-engined Bird of Passage, which he brought to Shellbeach in the spring of 1909; on this he became the first Englishman to fly in England, at the end of April. The Daily Mail’s prize was announced just previously, on 7 April, and had to be won within one year from that date, so Moore-Brabazon was naturally keen to add to his laurels.

By this time Short Brothers’ works at Shellbeach were in commission and Horace Short had become familiar with the details of the Wright Flyer and indeed critical of some of its design features. It was by no means certain that any British engine of more than 30 hp would be available, but a 50-60 hp Green was ordered, although delivery from the Aster works, where they were being made, was at that time very slow. Moore-Brabazon had salvaged the Vivinus engine originally fitted to his second Voisin, and this was available for practice flights, although ineligible for competition, because of its Belgian origin.

Short No. 2 incorporated a great deal of Wright practice, but differed in several important respects. The biplane wings and front elevators were somewhat similar to the Wrights’, but of higher aspect ratio. The chassis comprised a pair of strongly trussed girders shaped like a sleigh to ride across the Leysdown dykes in a forced landing; each girder consisted of upper and lower longerons, parallel below the wings but curved upwards at the front to meet at the elevator pivots, separated by nine vertical struts braced by diagonal steel strips in each bay, the strips being twisted so as to lie flat where they crossed each other. Like Short No. 1, both of No. 2’s propellers turned the same way, being driven by uncrossed chains. The elevators were of wide span and narrow chord and gap, with square tips, and incorporated a new type of camber-changing linkage (patent No. 23,166/09) which avoided infringement of the Wright patent (No. 16,068/09). The mainplanes were rigidly braced throughout their span, warping being replaced by differentially linked ‘balancers’, or mid-gap ailerons, for lateral control; these were of very low aspect ratio, and each comprised a pair of forward and aft ‘sails’ carried on a centre-pivoted boom mounted just above the middle of the outermost wing strut; the fabric of each sail was stretched on its frame by tension springs along the trailing edge so that the surface took up a camber appropriate to its angle of attack. The balancers were controlled by a centre-pivoted foot-bar with stirrups at each end, while the pilot had also two hand-levers, the right for the elevator and the left for the rudder, both moving fore-and-aft. The pilot’s seat was mounted on the lower leading edge to starboard, with the engine on the centre-line farther aft, leaving space for a passenger’s seat on the port side, if required. The single rudder was a tall narrow rectangle carried on short outriggers immediately aft of the elevator assembly, and a large vertical fin was carried by a pair of booms behind the wings. Horace Short was convinced that a large fixed fin surface in the slipstream was necessary to counteract yaw due to warping or aileron drag; he had argued unsuccessfully to this effect with the Wright brothers, who preferred their fixed keel area (‘blinkers’) forward and their rudders aft.

Short No. 2 was completed during September 1909, but the Green engine had not been delivered by then, so the Vivinus was installed for preliminary trials; in spite of being underpowered with this rather heavy engine, Moore-Brabazon succeeded in flying nearly a mile after being launched by derrick and rail on 27 September; he made a second flight of about 400 yards on 30 September, but landed heavily and damaged the port wing-tip. This was repaired, and the Green engine, which had just arrived, was installed, giving a larger reserve of power. Notice was given to the Daily Mail and the Aero Club that all was ready for the attempt on the £1,000 prize, and Lord Northcliffe sent Charles Hands to observe the flight; at once the weather became unsettled and remained so for a fortnight, but at last the day came; Moore-Brabazon rounded a mark-post half a mile away and landed back beside the starting rail, in an undulating flight varying in altitude from 20 ft to a few inches, but without actually touching the ground; he had won the prize, and the date was 30 October, 1909. This was two days before Charles Rolls made his first true flight on the first of the Short-Wright Flyers, and Moore-Brabazon could have claimed the David Salomans Cup also, but very sportingly waived his claim to it provided Rolls could himself qualify for it within one week, which he did. Moore-Brabazon’s prize-winning flight was followed by appropriate celebrations at Mussel Manor, during which he was challenged to take up a piglet to disprove the adage that ‘pigs can’t fly’; this he did in style on 4 November with a 3 1/2 miles cross-country flight outside the Shellbeach ground; on 7 January, 1910, he flew 4 1/2 miles from Shellbeach to the new flying ground at Eastchurch, after first winning the second of the Aero Club’s £25 prizes for an observed flight of 250 yards. Before leaving Shellbeach a larger cruciform tail, carried on four booms, had been fitted to No. 2, to improve stability for an attempt on the British Michelin Cup. Moore-Brabazon began practising in earnest for this competition, which closed on 31 March, 1910, and made four short flights on 12 February, followed by one of eight minutes on the 14th, carrying 20 gallons of petrol. All was ready for a serious attempt on 1 March, and he had covered 19 miles in 31 minutes before his crankshaft broke as a result of running continuously at maximum power. A spare engine was available and was fitted two days later, but then No. 2 was due to be exhibited on the Royal Aero Club’s stand at Olympia. After the show, No. 2 was taken back to Eastchurch, where the empennage was raised 21-in to a position level with the upper wing; Moore-Brabazon flew it once in this condition on 25 March, finding no improvement in control, but knew by then that nobody else with an all-British machine had a chance of beating his earlier performance, and in April he was adjudged the winner of the Cup; much longer distances had been flown by Rolls in his Short-Wright, but this was ineligible because of its French engine. After this Moore-Brabazon ordered one of the newer Farman-type biplanes that Horace had begun building after moving his works to Eastchurch and No. 2 was not flown again; there is an excellent 1/10 scale model of it in the Science Museum at South Kensington.

Span 48 ft 8 in (14-9 m); length 32 ft (9-75 m); area 450 sq ft (41-8 m2); loaded weight 1,485 lb (674 kg); speed 45 mph (72-5 km/h).

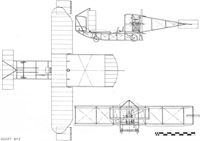

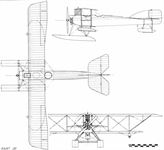

Short Biplane No. 3

Like the Wright Type A, the Short No. 2 biplane was handicapped by its dependence on rail and derrick launching, quite apart from its general instability and unorthodox control system. Horace Short was well aware of these disadvantages and discussed them at length with members of the Aero Club at Mussel Manor. Late in 1909 he designed and built to Charles Rolls’ order an improved lightweight biplane, Short No. 3, which was completed in time for the next Olympia show in March 1910. It was much smaller than No. 2, although similar in layout, and had four wheels which could be held down below the skid runners for taxying and take-off, and retracted by springs before landing. The engine, a 35 hp Green, was mounted high up, with a direct-drive propeller, permitting the use of widely spaced booms to carry a fixed cruciform tail. Improved balancers with spring-tensioned fabric, as in No. 2, were operated by a right-hand lever with sideways movement only; the left-hand lever moved fore-and-aft to control the elevator, and there were foot pedals for direct control of the rudder, which was rubber-sprung to return to neutral if released. Thus the control system more nearly conformed to the single lever and rudder-bar system evolved by Esnault-Pelterie and popularised by Bleriot and Farman. The fixed tail comprised a low aspect ratio fin mounted centrally on a high aspect ratio tailplane, whose incidence could be adjusted on the ground through a limited range. The front rudder was larger than No. 2’s and the front elevators had no camber. Horace Short was anxious to find alternative means of lateral control at low speeds and took out several further patents for both leading-edge spoilers and trailing-edge intercostal vents or valves, to act as ‘lift dumpers’ on one side at a time. These are described in patents Nos. 2,613-5 of February 1910, but were not tested in flight, so far as is known. The chassis construction was generally similar to No. 2’s, with the same twisted-strip cross-bracing, and the wheel retraction device allowed the wheels to remain in use for landing if preferred, when they were sprung so as to bring the skids into play if the landing was too hard.

Five replicas of No. 3 were ordered even before the show opened, but in spite of its excellent workmanship, it was obviously out-of-date by comparison with the robust and uncomplicated Farman type, whose latest development by Roger Sommer had just been bought by Charles Rolls and was also on view. After the show ended, Rolls had only a few days to spare before taking part in the International Meeting at Nice, where he flew the French-built Wright on which he was killed at Bournemouth in July. When Short No. 3 failed to fly in its original form it seems that Rolls dismantled it and combined its chassis members with the wings, elevators and tail-booms of Short-Wright No. 6, as a prototype of his own design, called the Rolls Power Glider; this name indicates that he aimed to fly on as little power as possible at a low wing-loading. In the R.P.G. the 35 hp Green engine was installed on the starboard side, as in the Wright, but drove uncrossed Renolds chains, so that both propellers turned the same way; to compensate for the higher offset engine weight, the flat rectangular radiator was placed outboard of the port propeller shaft and was connected to the engine water jacket by long pipes. Apparently Rolls hoped to develop this contraption into a saleable article, but it was unfinished at his death, and the Wright components were retrieved by Short Brothers, who paid Rolls’ executors £200 for the dismantled No. 6, but could find no bidder for the remains of Short No. 3. The other five replicas of No. 3 were never started, and the only other aeroplanes built at Shellbeach were two designed by J. W. Dunne, one of them being Professor Huntington’s and the other the D.5 tailless biplane for the Blair Atholl Syndicate; it is not known whether these received Short constructor’s numbers, but the remaining c/ns up to 25 were not used, and a fresh start was made at Eastchurch with S.26, the first of the Short-Farman-Sommer boxkites.

Span 35 ft 2 in (10-7 m); length 31 ft (9 45 m); area 282 sq ft (261 m2); empty weight 657 lb (296 kg); loaded weight 860 lb (390 kg); estimated speed 45 mph (72-5 km/h).

The second biplane designed by Horace Short was ordered in April 1909 by J. T. C. Moore-Brabazon, specifically for his attempt to win the Daily Mail’s prize of £1,000 for the first flight of one mile in a closed circuit by a British pilot in an all-British aeroplane. Moore-Brabazon had built himself a biplane as early as 1907, for which Short Brothers had manufactured various components, although they had no part in its design. When it failed to fly at Brooklands, on the meagre power of a single 12 hp Buchet engine, he abandoned it and went to France, where he bought three Voisins in succession, the third being the E.N.V.-engined Bird of Passage, which he brought to Shellbeach in the spring of 1909; on this he became the first Englishman to fly in England, at the end of April. The Daily Mail’s prize was announced just previously, on 7 April, and had to be won within one year from that date, so Moore-Brabazon was naturally keen to add to his laurels.

By this time Short Brothers’ works at Shellbeach were in commission and Horace Short had become familiar with the details of the Wright Flyer and indeed critical of some of its design features. It was by no means certain that any British engine of more than 30 hp would be available, but a 50-60 hp Green was ordered, although delivery from the Aster works, where they were being made, was at that time very slow. Moore-Brabazon had salvaged the Vivinus engine originally fitted to his second Voisin, and this was available for practice flights, although ineligible for competition, because of its Belgian origin.

Short No. 2 incorporated a great deal of Wright practice, but differed in several important respects. The biplane wings and front elevators were somewhat similar to the Wrights’, but of higher aspect ratio. The chassis comprised a pair of strongly trussed girders shaped like a sleigh to ride across the Leysdown dykes in a forced landing; each girder consisted of upper and lower longerons, parallel below the wings but curved upwards at the front to meet at the elevator pivots, separated by nine vertical struts braced by diagonal steel strips in each bay, the strips being twisted so as to lie flat where they crossed each other. Like Short No. 1, both of No. 2’s propellers turned the same way, being driven by uncrossed chains. The elevators were of wide span and narrow chord and gap, with square tips, and incorporated a new type of camber-changing linkage (patent No. 23,166/09) which avoided infringement of the Wright patent (No. 16,068/09). The mainplanes were rigidly braced throughout their span, warping being replaced by differentially linked ‘balancers’, or mid-gap ailerons, for lateral control; these were of very low aspect ratio, and each comprised a pair of forward and aft ‘sails’ carried on a centre-pivoted boom mounted just above the middle of the outermost wing strut; the fabric of each sail was stretched on its frame by tension springs along the trailing edge so that the surface took up a camber appropriate to its angle of attack. The balancers were controlled by a centre-pivoted foot-bar with stirrups at each end, while the pilot had also two hand-levers, the right for the elevator and the left for the rudder, both moving fore-and-aft. The pilot’s seat was mounted on the lower leading edge to starboard, with the engine on the centre-line farther aft, leaving space for a passenger’s seat on the port side, if required. The single rudder was a tall narrow rectangle carried on short outriggers immediately aft of the elevator assembly, and a large vertical fin was carried by a pair of booms behind the wings. Horace Short was convinced that a large fixed fin surface in the slipstream was necessary to counteract yaw due to warping or aileron drag; he had argued unsuccessfully to this effect with the Wright brothers, who preferred their fixed keel area (‘blinkers’) forward and their rudders aft.

Short No. 2 was completed during September 1909, but the Green engine had not been delivered by then, so the Vivinus was installed for preliminary trials; in spite of being underpowered with this rather heavy engine, Moore-Brabazon succeeded in flying nearly a mile after being launched by derrick and rail on 27 September; he made a second flight of about 400 yards on 30 September, but landed heavily and damaged the port wing-tip. This was repaired, and the Green engine, which had just arrived, was installed, giving a larger reserve of power. Notice was given to the Daily Mail and the Aero Club that all was ready for the attempt on the £1,000 prize, and Lord Northcliffe sent Charles Hands to observe the flight; at once the weather became unsettled and remained so for a fortnight, but at last the day came; Moore-Brabazon rounded a mark-post half a mile away and landed back beside the starting rail, in an undulating flight varying in altitude from 20 ft to a few inches, but without actually touching the ground; he had won the prize, and the date was 30 October, 1909. This was two days before Charles Rolls made his first true flight on the first of the Short-Wright Flyers, and Moore-Brabazon could have claimed the David Salomans Cup also, but very sportingly waived his claim to it provided Rolls could himself qualify for it within one week, which he did. Moore-Brabazon’s prize-winning flight was followed by appropriate celebrations at Mussel Manor, during which he was challenged to take up a piglet to disprove the adage that ‘pigs can’t fly’; this he did in style on 4 November with a 3 1/2 miles cross-country flight outside the Shellbeach ground; on 7 January, 1910, he flew 4 1/2 miles from Shellbeach to the new flying ground at Eastchurch, after first winning the second of the Aero Club’s £25 prizes for an observed flight of 250 yards. Before leaving Shellbeach a larger cruciform tail, carried on four booms, had been fitted to No. 2, to improve stability for an attempt on the British Michelin Cup. Moore-Brabazon began practising in earnest for this competition, which closed on 31 March, 1910, and made four short flights on 12 February, followed by one of eight minutes on the 14th, carrying 20 gallons of petrol. All was ready for a serious attempt on 1 March, and he had covered 19 miles in 31 minutes before his crankshaft broke as a result of running continuously at maximum power. A spare engine was available and was fitted two days later, but then No. 2 was due to be exhibited on the Royal Aero Club’s stand at Olympia. After the show, No. 2 was taken back to Eastchurch, where the empennage was raised 21-in to a position level with the upper wing; Moore-Brabazon flew it once in this condition on 25 March, finding no improvement in control, but knew by then that nobody else with an all-British machine had a chance of beating his earlier performance, and in April he was adjudged the winner of the Cup; much longer distances had been flown by Rolls in his Short-Wright, but this was ineligible because of its French engine. After this Moore-Brabazon ordered one of the newer Farman-type biplanes that Horace had begun building after moving his works to Eastchurch and No. 2 was not flown again; there is an excellent 1/10 scale model of it in the Science Museum at South Kensington.

Span 48 ft 8 in (14-9 m); length 32 ft (9-75 m); area 450 sq ft (41-8 m2); loaded weight 1,485 lb (674 kg); speed 45 mph (72-5 km/h).

Short Biplane No. 3

Like the Wright Type A, the Short No. 2 biplane was handicapped by its dependence on rail and derrick launching, quite apart from its general instability and unorthodox control system. Horace Short was well aware of these disadvantages and discussed them at length with members of the Aero Club at Mussel Manor. Late in 1909 he designed and built to Charles Rolls’ order an improved lightweight biplane, Short No. 3, which was completed in time for the next Olympia show in March 1910. It was much smaller than No. 2, although similar in layout, and had four wheels which could be held down below the skid runners for taxying and take-off, and retracted by springs before landing. The engine, a 35 hp Green, was mounted high up, with a direct-drive propeller, permitting the use of widely spaced booms to carry a fixed cruciform tail. Improved balancers with spring-tensioned fabric, as in No. 2, were operated by a right-hand lever with sideways movement only; the left-hand lever moved fore-and-aft to control the elevator, and there were foot pedals for direct control of the rudder, which was rubber-sprung to return to neutral if released. Thus the control system more nearly conformed to the single lever and rudder-bar system evolved by Esnault-Pelterie and popularised by Bleriot and Farman. The fixed tail comprised a low aspect ratio fin mounted centrally on a high aspect ratio tailplane, whose incidence could be adjusted on the ground through a limited range. The front rudder was larger than No. 2’s and the front elevators had no camber. Horace Short was anxious to find alternative means of lateral control at low speeds and took out several further patents for both leading-edge spoilers and trailing-edge intercostal vents or valves, to act as ‘lift dumpers’ on one side at a time. These are described in patents Nos. 2,613-5 of February 1910, but were not tested in flight, so far as is known. The chassis construction was generally similar to No. 2’s, with the same twisted-strip cross-bracing, and the wheel retraction device allowed the wheels to remain in use for landing if preferred, when they were sprung so as to bring the skids into play if the landing was too hard.

Five replicas of No. 3 were ordered even before the show opened, but in spite of its excellent workmanship, it was obviously out-of-date by comparison with the robust and uncomplicated Farman type, whose latest development by Roger Sommer had just been bought by Charles Rolls and was also on view. After the show ended, Rolls had only a few days to spare before taking part in the International Meeting at Nice, where he flew the French-built Wright on which he was killed at Bournemouth in July. When Short No. 3 failed to fly in its original form it seems that Rolls dismantled it and combined its chassis members with the wings, elevators and tail-booms of Short-Wright No. 6, as a prototype of his own design, called the Rolls Power Glider; this name indicates that he aimed to fly on as little power as possible at a low wing-loading. In the R.P.G. the 35 hp Green engine was installed on the starboard side, as in the Wright, but drove uncrossed Renolds chains, so that both propellers turned the same way; to compensate for the higher offset engine weight, the flat rectangular radiator was placed outboard of the port propeller shaft and was connected to the engine water jacket by long pipes. Apparently Rolls hoped to develop this contraption into a saleable article, but it was unfinished at his death, and the Wright components were retrieved by Short Brothers, who paid Rolls’ executors £200 for the dismantled No. 6, but could find no bidder for the remains of Short No. 3. The other five replicas of No. 3 were never started, and the only other aeroplanes built at Shellbeach were two designed by J. W. Dunne, one of them being Professor Huntington’s and the other the D.5 tailless biplane for the Blair Atholl Syndicate; it is not known whether these received Short constructor’s numbers, but the remaining c/ns up to 25 were not used, and a fresh start was made at Eastchurch with S.26, the first of the Short-Farman-Sommer boxkites.

Span 35 ft 2 in (10-7 m); length 31 ft (9 45 m); area 282 sq ft (261 m2); empty weight 657 lb (296 kg); loaded weight 860 lb (390 kg); estimated speed 45 mph (72-5 km/h).

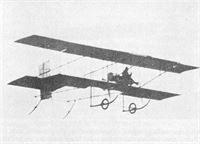

J. T. C. Moore-Brabazon flying Short No. 2 at Leysdown in November 1909 after the Green engine had been installed.

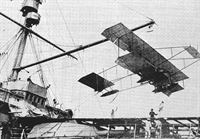

The Rolls Power Glider constructed by combining the wings and control surfaces of Short-Wright No. 6 with the chassis and engine of Short No. 3, at Eastchurch in May 1910.

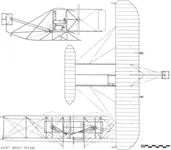

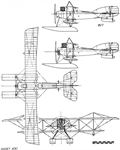

Short-Wright Biplanes

<...>

Horace Short designed and manufactured the Short-Wright glider at Battersea in four weeks during the spring of 1909, taking it to Shellbeach in June for fabric covering and final rigging; Rolls attempted his first launch, unsuccessfully, on 1 August and achieved his first glide the following day. Thereafter he practised regularly and with increasing proficiency till 10 October.

The Short-Wright glider had plain rectangular warping wings, with a forward biplane elevator and twin aft rudders exactly similar to the Wright glider of 1902-3, except that the pilot sat upright with a control lever in each hand; the left-hand lever moved fore-and-aft to control the elevator, and the right-hand lever moved sideways for warping and fore-and-aft to control the rudder. It was hand-launched from a trolley on a rail laid downhill on a slight eminence near Leysdown, and Rolls achieved soaring flights of several hundred yards in suitable weather. Rolls did not dispose of his glider until March 1910, when he offered it for sale in good condition, together with its shed and rail and the lease of the site.

<...>

Glider - Span 32 ft 10 in (10 m); length 18 ft (5-5 m); area 325 sq ft (30 m2).

<...>

Horace Short designed and manufactured the Short-Wright glider at Battersea in four weeks during the spring of 1909, taking it to Shellbeach in June for fabric covering and final rigging; Rolls attempted his first launch, unsuccessfully, on 1 August and achieved his first glide the following day. Thereafter he practised regularly and with increasing proficiency till 10 October.

The Short-Wright glider had plain rectangular warping wings, with a forward biplane elevator and twin aft rudders exactly similar to the Wright glider of 1902-3, except that the pilot sat upright with a control lever in each hand; the left-hand lever moved fore-and-aft to control the elevator, and the right-hand lever moved sideways for warping and fore-and-aft to control the rudder. It was hand-launched from a trolley on a rail laid downhill on a slight eminence near Leysdown, and Rolls achieved soaring flights of several hundred yards in suitable weather. Rolls did not dispose of his glider until March 1910, when he offered it for sale in good condition, together with its shed and rail and the lease of the site.

<...>

Glider - Span 32 ft 10 in (10 m); length 18 ft (5-5 m); area 325 sq ft (30 m2).

Short-Wright Biplanes

Wilbur Wright’s demonstrations of flying the improved Wright Model A biplane at Hunaudieres and Camp d’Auvours, near Le Mans, in August 1908, created unprecedented enthusiasm, with spectators and would-be passengers flocking from all over Europe to see him. After taking up numerous passengers in September and October, including leading members of the Aero Club of the United Kingdom, Wilbur Wright was bombarded with requests for replicas of the Flyer; Charles S. Rolls was among the first to place an unconditional order for one. But the demonstration Flyer was only the fourth powered machine the Wrights had constructed, and their contract with Lazare Weiller, promoter of their European tour, provided for his ultimate retention of it, after completion of an agreed programme of demonstrations, including tuition for not more than three pupils. It was the first of its particular type, and the Wrights had not intended to put it into production, so they had never made any complete working drawings. However, they agreed to allow copies of the Flyer to be built under licence by approved constructors, and in France these were to be Chantiers de France at Dunkerque and the Societe Astra at Billancourt; during his first visit to France in 1907, Wilbur Wright had arranged for a firm of precision engineers, Bariquand & Marre of Paris, to build spare Wright engines, and in 1908 he was so cordially welcomed at Le Mans by Leon Bollee, who put a bay of his well-equipped automobile factory at Wilbur’s disposal, that Bollee also was awarded a licence to make Wright engines. All sales in France were handled by Weiller’s firm, Cie. Generale de Navigation Aerienne, but all the British Empire rights were held by Griffith Brewer, who managed the Wrights’ U.K. patents.

Brewer was a well-known balloonist, and from his experience of the work of the Short brothers had no hesitation in recommending them as competent to manufacture the Flyer in England; by February 1909 Eustace Short had made a contract with Wilbur Wright to construct six aircraft at a total price of £8,400; all were already bespoken by members of the Aero Club, the first being reserved for Charles Rolls in accordance with his original order of the previous September. Rolls was impatient to begin learning to fly, and since Wilbur Wright declined to take on any more pupils in addition to the three (Comte Charles de Lambert, Paul Tissandier and Capt Lucas de Girardville) already nominated in France, he recommended Rolls to start practising with a glider of the type already described in the patent of 1906, and gave Short Brothers permission to construct one apart from the Flyer contract. On completion of his flights at Le Mans in December 1908, Wilbur Wright moved to Pau in the warmer south on 14 January, 1909, accompanied by Orville Wright and their sister Katharine, who had just arrived from the United States. Horace Short spent several days with Eustace at Pau in February measuring and sketching every aspect of the Flyer, and soon after his return to England he and his assistant, P. M. Jones, had produced the first complete set of working drawings ever made of any Wright biplane. Meanwhile, the Aero Club had established its new flying ground at Shellbeach on Sheppey, and half a mile away Short Brothers built a new factory in which to assemble the six Short-Wright Flyers; work on details began at Battersea, but the railway arches were too cramped for final erection of aeroplanes. The first building, a corrugated-iron shed 100 ft long by 45 ft wide, was put up by Harbrow of Bermondsey early in March 1909, and by May Horace was already lamenting its inadequacy and planning extensions; by August a second shed was in use and Short Brothers were employing 80 men. Horace Short designed and manufactured the Short-Wright glider at Battersea in four weeks during the spring of 1909, taking it to Shellbeach in June for fabric covering and final rigging; Rolls attempted his first launch, unsuccessfully, on 1 August and achieved his first glide the following day. Thereafter he practised regularly and with increasing proficiency till 10 October.

The Short-Wright glider had plain rectangular warping wings, with a forward biplane elevator and twin aft rudders exactly similar to the Wright glider of 1902-3, except that the pilot sat upright with a control lever in each hand; the left-hand lever moved fore-and-aft to control the elevator, and the right-hand lever moved sideways for warping and fore-and-aft to control the rudder. It was hand-launched from a trolley on a rail laid downhill on a slight eminence near Leysdown, and Rolls achieved soaring flights of several hundred yards in suitable weather. Rolls did not dispose of his glider until March 1910, when he offered it for sale in good condition, together with its shed and rail and the lease of the site.

The Wrights visited Battersea on 3 May and Shellbeach the next day, and were well pleased with the quality and progress of the six Flyers under construction. As at first built, they were exactly similar to Wilbur Wright’s demonstration Flyer, and only the last two ever incorporated later improvements. The two-spar wings had neither dihedral nor stagger and were wire-braced, with the two outer bays on each side arranged to warp. The main chassis comprised a pair of forward elevator outriggers combined with landing skids. An additional small feature, peculiar to Short-built Flyers, was a projecting wing-tip skid at each end of the lower leading edge, introduced by Horace Short because of frequent damage on the rough ground at Shellbeach. The biplane elevator incorporated an ingenious linkage for reversing the camber to match the angle of attack, so that when incidence was negative the camber was inverted. The parallel rudders were boxed together and pivoted on a central vertical axis carried by a single pair of upper and lower booms braced by wires to the rear spars. The pilot and passenger sat side-by-side on the left-hand half of the lower wing between the chassis frames, with the engine beside them on their right; they had separate seats with back-rests and a common fixed foot-rail. The pilot usually sat on the right, with a fore-and-aft elevator lever in his left hand and a universally pivoted lever in his right hand, which moved fore-and-aft to control the rudder and sideways to control the warp; thus the functions of ‘balancing’ and ‘steering’ were psychologically separated, while the use of rudder to counteract warping drag became instinctive with the right hand, leading naturally to the Wrights’ elegant banked turns, previously thought to be a highly dangerous manoeuvre in spite of its universal and age-old use by birds and bats!

The 27 hp four-cylinder water-cooled vertical engine of the Wrights’ own design drove, through separate chains in guide tubes and sprockets giving a reduction ratio of 9 : 32, a pair of two-bladed propellers mounted outboard just behind the wings with their thrust-line at half-gap; their tips rotated outwards at the top, so creating a resultant upwash in the middle of the slipstream, the longer left-hand chain being crossed to produce counter-rotation. The standard method of take-off was from a trolley on a launching rail laid to face into wind, with assistance from a rope hooked to the trolley and pulled by a falling weight previously raised on a portable derrick located downwind of the rail. This was a nuisance in variable wind conditions and a source of trouble whenever the rope jammed in a pulley, which happened rather often. Occasionally, in a steady light breeze, the Flyer could take off without external assistance, and later in 1909 some of those built in France appeared with wheels attached to the skids.

Although the first four Short-Wright Flyers were completed by July 1909, they were kept waiting for their engines, which had originally been ordered from Leon Bollee for all six; only two Bollee engines were finally delivered, and Bariquand & Marre were substituted in the others, but none was ready for Orville Wright to test personally in August as intended. As a temporary expedient, Frank McClean installed the engine out of his Nordenfelt car in his Short-Wright (No. 3) and was launched from the rail, but failed to sustain flight; two Bollee engines eventually arrived and early in October Charles Rolls made a few brief hops in his Short-Wright (No. 1), but came to grief; after repairs to the minor damage incurred, he began flying steadily on 1 November, and his proficiency was such that before the day was out he had covered 1 1/2 miles, thereby winning the first of four Aero Club prizes of £25 for a flight of 250 yards and the David Salomans Cup and £105 for a flight of half a mile out and half a mile back without landing. Three days later he won the first of three Aero Club prizes of £50 for flying one mile in a closed circuit at Shellbeach, which he accomplished at a height of 60 ft. Alec Ogilvie took delivery of Short-Wright No. 2 at his private flying ground at Camber Sands, near Rye, Sussex, on 3 November, 1909, when he flew for nine minutes. Next day he made two more flights of ten minutes each, but allowed enthusiasm to outrun caution; after attaining 50 mph (as shown by an air-speed indicator of his own design and later improved and patented by him) his Leon Bollee engine seized, but he made a safe forced landing. On 20 November Rolls flew from Shellbeach to the Aero Club’s new flying ground at Eastchurch, over an indirect course of 5 1/2 miles, but two days later he, too, suffered engine failure after covering seven miles. On the same day Frank McClean took delivery of the third Short-Wright, after installation of its Bariquand engine, making initial flights up to 400 yards in length, and continued to make steady if unspectacular progress whenever the weather permitted, attaining four miles by 17 December (the sixth anniversary of Orville Wright’s historic ‘first ever’ powered flight). McClean had not had as much prior experience as Rolls and Ogilvie, for the latter had purchased a Wright glider from T. W. K. Clarke of Willesden in August and had soared it for 350 yards after less than a fortnight’s practice. By 21 December Rolls had achieved a 15-mile cross-country flight over Sheppey and the fourth Short-Wright had been delivered to Maurice Egerton. On New Year’s Day 1910 Frank McClean flew from Eastchurch to Short Brothers’ works and back, and Rolls, after a solo flight of nearly an hour, took up Cecil Grace as his first passenger. During the next few weeks Rolls flew frequently with passengers, including Ogilvie, whose own machine was back at Shellbeach for repairs, and on 12 February Maurice Egerton flew over to Shellbeach to win both the third £25 and the second £50 Aero Club prizes.

The last two Short-Wright Flyers, ordered originally by Percy Grace and Ernest Pitman, incorporated an improved four-boom tail outrigger with a single fixed tailplane behind the rudders. Both were flown for the first time on 14 February, the former by Cecil Grace, who covered 300 yards (after earlier practice on Moore-Brabazon’s Voisin Bird of Passage) and the latter by Charles Rolls, who had bought it from Ernest Pitman before completion; after a spectacular high flight in his new machine on 25 February, Rolls towed his old Flyer behind his Silver Ghost tourer to London for exhibition on the Royal Aero Club’s stand at Olympia, after which he presented it to the Balloon Company, Royal Engineers, at Aldershot; subsequently he gave ground instruction to Army officers on it at Farnborough, and later it was kept at Hounslow Barracks, but there is no record of its ever being flown again. On 24 March Rolls collected his new Flyer from the works at Shellbeach and flew it thence all round Sheppey for 26 miles, attaining 1,000 ft over Queenborough before landing at Eastchurch. On the same day Cecil Grace won the remaining £25 and £50 prizes at Shellbeach; he went on to make regular flights throughout April, culminating in a 46-minute flight over Sheerness at 1,500 ft, in the course of which he dropped a packet of letters, all of which were posted by their finders and reached their destinations. Meanwhile Rolls had bought a new French-built Wright with a wheeled chassis, which he flew at the Nice International Meeting as one of the Royal Aero Club’s representatives; on his return he kept this machine for competition purposes, while his second Short-Wright was dismantled to donate its wings, elevators and empennage to his experimental Rolls Power Glider, or R.P.G., which also employed the wheeled chassis and 35 hp Green engine from the unsuccessful Short No. 3 biplane (q.v.). Consequently, he used his French Wright at the Wolverhampton meeting, having previously flown it on 2 June from Dover to Sangatte and back without landing, a feat which won him the Gold Medal of the Royal Aero Club and other awards. Ogilvie flew his Short-Wright (No. 2) at Wolverhampton, and a fortnight later he and Rolls both entered the same machines in the Bournemouth meeting, where Rolls met his death on 12 July while making a second attempt to win the alighting competition. Horace Short, who examined the wreckage, concluded that the tail-boom was not stiff enough to carry the controllable aft elevator which Rolls had fitted only five days earlier, and had deflected far enough to touch the tip of one propeller, with catastrophic results.

After Rolls’ death Short Brothers bought back Short-Wright No. 6 from his executors, reassembled it and sold it, less engine, to Alec Ogilvie, who had already fitted wheels to his first Flyer with some success. This encouraged him to make a series of modifications to No. 6, with a view to competing in all British events, including the de Forest prize and the British Michelin Cup, for which Bollee and Bariquand & Marre engines were ineligible. He first considered fitting a 50 hp E.N.V., but the British-built model of this engine was not yet available, so he chose a new 50 hp V-4 two-stroke supercharged N.E.C., which he installed in September 1910; then he went to New York as the Royal Aero Club’s entry in the Gordon Bennett Race at Belmont Park in October. His mount was a Wright C-type racer, with wheels but no front elevators, whose performance so impressed him that on his return to England in December he tried hard to persuade Horace Short to accept the Wrights’ offer to extend Shorts’ manufacturing licence to include the later models; Horace refused to do so, and Ogilvie thereupon went off, apparently in rather a huff, to Camber, where he proceeded to convert the sixth Short-Wright to the latest Dayton standard, with the tailplane turned into an aft elevator, the front elevators deleted, the skids shortened and the ‘blinkers’ placed low on them. He also incorporated Orville Wright’s improved steering control, comprising a fore-and-aft lever for the right hand, operating rudder and warp together, with a sideways-hinged handle at the top, whereby a limited amount of differential movement could be interposed between rudder and warp controls. The N.E.C. engine rotated the opposite way to the Wright, and with a rear elevator this was found to be an advantage because it gave pitch-up with engine on and pitch-down with engine off, so improving longitudinal stability and making the machine less tiring to fly.

With these modifications, Ogilvie flew 142 miles in just under four hours on 28 December, 1910, in an attempt to win the British Michelin Cup, terminated prematurely by a radiator leak. In May his lease of the Camber ground expired and he flew back to Eastchurch on 2 May, 1911, and remained there; in later months he modified his machine even more, bringing the engine forward and placing the pilot’s and passenger’s seats behind it, the whole being enclosed in a nacelle. This improved performance as well as comfort, and on 29 June, 1912, he took off at Eastchurch with three passengers in addition to his own not inconsiderable weight; still later he tried it on floats at Leysdown, but found it unseaworthy. Ogilvie’s modified Short-Wright was still being regularly flown right up to the outbreak of war in August 1914, and its N.E.C. engine survives in the Science Museum, South Kensington, London, together with the Wright-Bollee engine and one propeller from Short-Wright No. 2. One of the Bariquand & Marre engines, almost certainly that first installed in Short-Wright No. 6, was stored successively at Eastchurch and Rochester and was later restored and placed on permanent exhibition at Queen’s Island, Belfast; incidentally, Bariquand & Marre’s London agency, Barimar Ltd, became world-famous as exponents of machinery repairs by welding and now, based at Newcastle-upon-Tyne, occupies a leading place in shipbuilding and heavy steel fabrication.

Glider - Span 32 ft 10 in (10 m); length 18 ft (5-5 m); area 325 sq ft (30 m2).

Flyer - Span 41 ft (12-5 m); length 29 ft (8-8 m); area 515 sq ft (47-8 m2); empty weight 885 lb (401 kg); loaded weight 1,200 lb (545 kg); speed 50 mph (80 km/h).

Wilbur Wright’s demonstrations of flying the improved Wright Model A biplane at Hunaudieres and Camp d’Auvours, near Le Mans, in August 1908, created unprecedented enthusiasm, with spectators and would-be passengers flocking from all over Europe to see him. After taking up numerous passengers in September and October, including leading members of the Aero Club of the United Kingdom, Wilbur Wright was bombarded with requests for replicas of the Flyer; Charles S. Rolls was among the first to place an unconditional order for one. But the demonstration Flyer was only the fourth powered machine the Wrights had constructed, and their contract with Lazare Weiller, promoter of their European tour, provided for his ultimate retention of it, after completion of an agreed programme of demonstrations, including tuition for not more than three pupils. It was the first of its particular type, and the Wrights had not intended to put it into production, so they had never made any complete working drawings. However, they agreed to allow copies of the Flyer to be built under licence by approved constructors, and in France these were to be Chantiers de France at Dunkerque and the Societe Astra at Billancourt; during his first visit to France in 1907, Wilbur Wright had arranged for a firm of precision engineers, Bariquand & Marre of Paris, to build spare Wright engines, and in 1908 he was so cordially welcomed at Le Mans by Leon Bollee, who put a bay of his well-equipped automobile factory at Wilbur’s disposal, that Bollee also was awarded a licence to make Wright engines. All sales in France were handled by Weiller’s firm, Cie. Generale de Navigation Aerienne, but all the British Empire rights were held by Griffith Brewer, who managed the Wrights’ U.K. patents.

Brewer was a well-known balloonist, and from his experience of the work of the Short brothers had no hesitation in recommending them as competent to manufacture the Flyer in England; by February 1909 Eustace Short had made a contract with Wilbur Wright to construct six aircraft at a total price of £8,400; all were already bespoken by members of the Aero Club, the first being reserved for Charles Rolls in accordance with his original order of the previous September. Rolls was impatient to begin learning to fly, and since Wilbur Wright declined to take on any more pupils in addition to the three (Comte Charles de Lambert, Paul Tissandier and Capt Lucas de Girardville) already nominated in France, he recommended Rolls to start practising with a glider of the type already described in the patent of 1906, and gave Short Brothers permission to construct one apart from the Flyer contract. On completion of his flights at Le Mans in December 1908, Wilbur Wright moved to Pau in the warmer south on 14 January, 1909, accompanied by Orville Wright and their sister Katharine, who had just arrived from the United States. Horace Short spent several days with Eustace at Pau in February measuring and sketching every aspect of the Flyer, and soon after his return to England he and his assistant, P. M. Jones, had produced the first complete set of working drawings ever made of any Wright biplane. Meanwhile, the Aero Club had established its new flying ground at Shellbeach on Sheppey, and half a mile away Short Brothers built a new factory in which to assemble the six Short-Wright Flyers; work on details began at Battersea, but the railway arches were too cramped for final erection of aeroplanes. The first building, a corrugated-iron shed 100 ft long by 45 ft wide, was put up by Harbrow of Bermondsey early in March 1909, and by May Horace was already lamenting its inadequacy and planning extensions; by August a second shed was in use and Short Brothers were employing 80 men. Horace Short designed and manufactured the Short-Wright glider at Battersea in four weeks during the spring of 1909, taking it to Shellbeach in June for fabric covering and final rigging; Rolls attempted his first launch, unsuccessfully, on 1 August and achieved his first glide the following day. Thereafter he practised regularly and with increasing proficiency till 10 October.

The Short-Wright glider had plain rectangular warping wings, with a forward biplane elevator and twin aft rudders exactly similar to the Wright glider of 1902-3, except that the pilot sat upright with a control lever in each hand; the left-hand lever moved fore-and-aft to control the elevator, and the right-hand lever moved sideways for warping and fore-and-aft to control the rudder. It was hand-launched from a trolley on a rail laid downhill on a slight eminence near Leysdown, and Rolls achieved soaring flights of several hundred yards in suitable weather. Rolls did not dispose of his glider until March 1910, when he offered it for sale in good condition, together with its shed and rail and the lease of the site.

The Wrights visited Battersea on 3 May and Shellbeach the next day, and were well pleased with the quality and progress of the six Flyers under construction. As at first built, they were exactly similar to Wilbur Wright’s demonstration Flyer, and only the last two ever incorporated later improvements. The two-spar wings had neither dihedral nor stagger and were wire-braced, with the two outer bays on each side arranged to warp. The main chassis comprised a pair of forward elevator outriggers combined with landing skids. An additional small feature, peculiar to Short-built Flyers, was a projecting wing-tip skid at each end of the lower leading edge, introduced by Horace Short because of frequent damage on the rough ground at Shellbeach. The biplane elevator incorporated an ingenious linkage for reversing the camber to match the angle of attack, so that when incidence was negative the camber was inverted. The parallel rudders were boxed together and pivoted on a central vertical axis carried by a single pair of upper and lower booms braced by wires to the rear spars. The pilot and passenger sat side-by-side on the left-hand half of the lower wing between the chassis frames, with the engine beside them on their right; they had separate seats with back-rests and a common fixed foot-rail. The pilot usually sat on the right, with a fore-and-aft elevator lever in his left hand and a universally pivoted lever in his right hand, which moved fore-and-aft to control the rudder and sideways to control the warp; thus the functions of ‘balancing’ and ‘steering’ were psychologically separated, while the use of rudder to counteract warping drag became instinctive with the right hand, leading naturally to the Wrights’ elegant banked turns, previously thought to be a highly dangerous manoeuvre in spite of its universal and age-old use by birds and bats!

The 27 hp four-cylinder water-cooled vertical engine of the Wrights’ own design drove, through separate chains in guide tubes and sprockets giving a reduction ratio of 9 : 32, a pair of two-bladed propellers mounted outboard just behind the wings with their thrust-line at half-gap; their tips rotated outwards at the top, so creating a resultant upwash in the middle of the slipstream, the longer left-hand chain being crossed to produce counter-rotation. The standard method of take-off was from a trolley on a launching rail laid to face into wind, with assistance from a rope hooked to the trolley and pulled by a falling weight previously raised on a portable derrick located downwind of the rail. This was a nuisance in variable wind conditions and a source of trouble whenever the rope jammed in a pulley, which happened rather often. Occasionally, in a steady light breeze, the Flyer could take off without external assistance, and later in 1909 some of those built in France appeared with wheels attached to the skids.

Although the first four Short-Wright Flyers were completed by July 1909, they were kept waiting for their engines, which had originally been ordered from Leon Bollee for all six; only two Bollee engines were finally delivered, and Bariquand & Marre were substituted in the others, but none was ready for Orville Wright to test personally in August as intended. As a temporary expedient, Frank McClean installed the engine out of his Nordenfelt car in his Short-Wright (No. 3) and was launched from the rail, but failed to sustain flight; two Bollee engines eventually arrived and early in October Charles Rolls made a few brief hops in his Short-Wright (No. 1), but came to grief; after repairs to the minor damage incurred, he began flying steadily on 1 November, and his proficiency was such that before the day was out he had covered 1 1/2 miles, thereby winning the first of four Aero Club prizes of £25 for a flight of 250 yards and the David Salomans Cup and £105 for a flight of half a mile out and half a mile back without landing. Three days later he won the first of three Aero Club prizes of £50 for flying one mile in a closed circuit at Shellbeach, which he accomplished at a height of 60 ft. Alec Ogilvie took delivery of Short-Wright No. 2 at his private flying ground at Camber Sands, near Rye, Sussex, on 3 November, 1909, when he flew for nine minutes. Next day he made two more flights of ten minutes each, but allowed enthusiasm to outrun caution; after attaining 50 mph (as shown by an air-speed indicator of his own design and later improved and patented by him) his Leon Bollee engine seized, but he made a safe forced landing. On 20 November Rolls flew from Shellbeach to the Aero Club’s new flying ground at Eastchurch, over an indirect course of 5 1/2 miles, but two days later he, too, suffered engine failure after covering seven miles. On the same day Frank McClean took delivery of the third Short-Wright, after installation of its Bariquand engine, making initial flights up to 400 yards in length, and continued to make steady if unspectacular progress whenever the weather permitted, attaining four miles by 17 December (the sixth anniversary of Orville Wright’s historic ‘first ever’ powered flight). McClean had not had as much prior experience as Rolls and Ogilvie, for the latter had purchased a Wright glider from T. W. K. Clarke of Willesden in August and had soared it for 350 yards after less than a fortnight’s practice. By 21 December Rolls had achieved a 15-mile cross-country flight over Sheppey and the fourth Short-Wright had been delivered to Maurice Egerton. On New Year’s Day 1910 Frank McClean flew from Eastchurch to Short Brothers’ works and back, and Rolls, after a solo flight of nearly an hour, took up Cecil Grace as his first passenger. During the next few weeks Rolls flew frequently with passengers, including Ogilvie, whose own machine was back at Shellbeach for repairs, and on 12 February Maurice Egerton flew over to Shellbeach to win both the third £25 and the second £50 Aero Club prizes.

The last two Short-Wright Flyers, ordered originally by Percy Grace and Ernest Pitman, incorporated an improved four-boom tail outrigger with a single fixed tailplane behind the rudders. Both were flown for the first time on 14 February, the former by Cecil Grace, who covered 300 yards (after earlier practice on Moore-Brabazon’s Voisin Bird of Passage) and the latter by Charles Rolls, who had bought it from Ernest Pitman before completion; after a spectacular high flight in his new machine on 25 February, Rolls towed his old Flyer behind his Silver Ghost tourer to London for exhibition on the Royal Aero Club’s stand at Olympia, after which he presented it to the Balloon Company, Royal Engineers, at Aldershot; subsequently he gave ground instruction to Army officers on it at Farnborough, and later it was kept at Hounslow Barracks, but there is no record of its ever being flown again. On 24 March Rolls collected his new Flyer from the works at Shellbeach and flew it thence all round Sheppey for 26 miles, attaining 1,000 ft over Queenborough before landing at Eastchurch. On the same day Cecil Grace won the remaining £25 and £50 prizes at Shellbeach; he went on to make regular flights throughout April, culminating in a 46-minute flight over Sheerness at 1,500 ft, in the course of which he dropped a packet of letters, all of which were posted by their finders and reached their destinations. Meanwhile Rolls had bought a new French-built Wright with a wheeled chassis, which he flew at the Nice International Meeting as one of the Royal Aero Club’s representatives; on his return he kept this machine for competition purposes, while his second Short-Wright was dismantled to donate its wings, elevators and empennage to his experimental Rolls Power Glider, or R.P.G., which also employed the wheeled chassis and 35 hp Green engine from the unsuccessful Short No. 3 biplane (q.v.). Consequently, he used his French Wright at the Wolverhampton meeting, having previously flown it on 2 June from Dover to Sangatte and back without landing, a feat which won him the Gold Medal of the Royal Aero Club and other awards. Ogilvie flew his Short-Wright (No. 2) at Wolverhampton, and a fortnight later he and Rolls both entered the same machines in the Bournemouth meeting, where Rolls met his death on 12 July while making a second attempt to win the alighting competition. Horace Short, who examined the wreckage, concluded that the tail-boom was not stiff enough to carry the controllable aft elevator which Rolls had fitted only five days earlier, and had deflected far enough to touch the tip of one propeller, with catastrophic results.