В.Кондратьев Самолеты первой мировой войны

ХЭНДЛИ-ПЭЙДЖ O/100 / HANDLEY-PAGE O/100

В декабре 1914 года Воздушный департамент британского Адмиралтейства выдал авиафирмам заказ на крупный двухмоторный аэроплан, предназначенный для дальнего противолодочного патрулирования. В начале 1915-го фирма Хэндли-Пэйдж предложила свой проект самолета, пригодного не только для поиска субмарин, но и для использования в качестве тяжелого бомбардировщика. Главным заказчиком по-прежнему выступало Адмиралтейство, которое особенно привлекала возможность атаковать вражеские суда прямо в гаванях, на якорных стоянках.

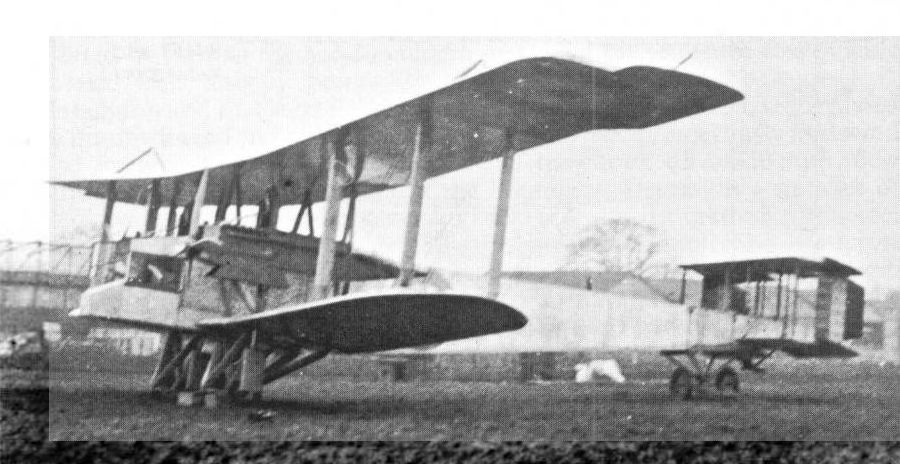

В марте с фирмой заключили контракт на выпуск 40 серийных экземпляров. Постройка прототипа завершилась к декабрю, и 18-го числа он впервые поднялся в воздух. Новую машину назвали "Хэндли-Пэйдж O/100". Это был двухмоторный полутораплан с бипланным хвостовым оперением, деревянным каркасом и полотняной обшивкой. Двигатели и бензобаки в вытянутых обтекаемых гондолах крепились на межкрыльевых стойках. Для того чтобы аэроплан мог помещаться в стандартных ангарах, полукоробки крыльев сделали складывающимися поворотом назад вдоль фюзеляжа.

Конструкторы фирмы уделили большое внимание защите экипажа и силовых установок. Полностью закрытая, остекленная кабина летчиков первоначально имела броневой пол и заднюю стенку. Мотогондолы также были бронированы. Но в ходе испытаний такие меры сочли излишними. Броневое прикрытие кабины убрали, а саму кабину сделали открытой, пожертвовав комфортом и безопасностью ради улучшения обзора и снижения веса. В носовой оконечности фюзеляжа появилась пулеметная турель.

Экипаж составляли 4 человека - двое пилотов, носовой стрелок-бомбардир и задний стрелок. Испытания и доводка машины продолжались более полугода. Их результаты были признаны весьма успешными. Особенно впечатляла боевая нагрузка - восемь 250-фунтовых (113 кг) бомб. Первым новые машины получило в ноябре 1916-го 3-е крыло RNAS, расквартированное на севере Франции.

Вначале "Хэндли-Пэйджи" осуществляли патрулирование над Ла-Маншем и вдоль берегов Фландрии. Затем их стали привлекать к более серьезным операциям. С марта 1917-го английские морские бомбардировщики совершали групповые налеты на германские военные заводы, железнодорожные станции и базы подводных лодок. Несколько машин было отправлено в Грецию и Палестину. На счету одной из них - бомбардировка турецкой столицы - Константинополя.

ДВИГАТЕЛИ

На большинстве "Хэндли-Пэйджей O/100" стояли моторы Роллс-Ройс "Игл II" по 250 л.с. Последние 6 экземпляров оснащались 320-сильными Санбим "Коссак".

ВООРУЖЕНИЕ

Носовая турель со спаркой "Льюисов", задняя верхняя стрелковая точка с "Льюисом" на поперечной рельсовой направляющей (иногда такая же турель, как и спереди, или две шкворневые установки по бортам) и задняя нижняя люковая пулеметная установка. Бомбовая нагрузка - от 800 до 920 кг в зависимости от типа двигателей.

ЛЕТНО-ТЕХНИЧЕСКИЕ ХАРАКТЕРИСТИКИ

Размах, м 30,48

Длина, м 19,15

Высота, м 6,70

Площадь крыла, кв.м 153,0

Сухой вес, кг 3630

Взлетный вес, кг 6350

Двигатель: Роллс-Ройс

"Игл II"

число х мощность, л. с. 2x235

Скорость максимальная, км/ч 122

Дальность полета, км 700

Потолок, м 2100

Экипаж, чел. 4

Вооружение 2 пулемета

454 кг бомб

Показать полностью

А.Шепс Самолеты Первой мировой войны. Страны Антанты

Хендли Пейдж H.P.11 (O/100) 1916 г.

Проектирование этой машины фирма начала в конце 1914 года одновременно с несколькими другими британскими фирмами, после знакомства с результатами использования самолетов РБВЗ "Илья Муромец" и в связи с потребностью фронта в тяжелом бомбардировщике. Летом 1916 года первый самолет совершил испытательный полет, и в октябре первые серийные машины поступили в третье авиакрыло RNAS в Дюнкерне, где машина использовалась в целях морской разведки.

Это был трехстоечный полутораплан с двумя двигателями. Фюзеляж прямоугольного сечения имел цельнодеревянную конструкцию и обшивался в носовой части фанерой, а в хвостовой - полотном. В носовой части устанавливалась шкворневая, а позднее турельная пулеметная установка. За ней располагалась кабина пилота, вторая пулеметная установка располагалась за задней кромкой крыла. За кабиной пилотов располагался бомбоотсек с направляющими для сброса бомб, а над ним устанавливались два топливных бака емкостью по 591 л, топливные насосы работали от двух вертушек, установленных по бортам фюзеляжа. В центроплане устанавливался расходный бак емкостью 55 л для запуска двигателей. Маслобаки устанавливались на моторах. Стрелок задней установки мог вести огонь через люк в полу и в нижней полусфере, однако сектор обстрела был незначителен.

Крыло двухлонжеронное, цельнодеревянной конструкции, с ферменными нервюрами и обтяжкой полотном. Элероны устанавливались только на верхнем крыле. Двигатели устанавливались на стойках между крыльями в мотогондолах. Это были 12-цилиндровые, жидкостного охлаждения, рядные, V-образные двигатели Роллс-Ройс "Игл II" мощностью по 235 л. с.

Оперение бипланного типа с двумя рулями поворота имело конструкцию, подобную конструкции крыла. Управление тросовое, от штурвала и педалей в кабине.

Шасси четырехколесное, на четырех V-образных стойках крепилось осями попарно и имело резиновую шнуровую амортизацию.

Самолет кроме пулеметного вооружения мог нести более 400 кг бомб. Построено 40 машин этого типа.

Показать полностью

C.Barnes Handley Page Aircraft since 1907 (Putnam)

O/100 and O/400 (H.P.11 and 12)

Handley Page Ltd had been in business for five years when hostilities flared up on 4 August, 1914, but its total output - eight aeroplanes of its own design and six more (including three B.E.2as) to customers’ designs - compared unfavourably with nearly 100 turned out by Short Brothers and over 200 by Bristol during the same period, to say nothing of rapidly increasing output from Sopwith and Vickers. The difficulties experienced (and exasperation expressed) over the B.E.2a contract had not endeared Handley Page and the War Office to one another, but nevertheless Handley Page offered the resources of his factory at 110 Cricklewood Lane to both Army and Navy without reservation. An inter-Service struggle for control of all aircraft manufacture having begun, it was to be expected that reluctance by one Service to place contracts would be promptly matched with enthusiasm by the other; so Captain Murray Sueter was quick off the mark in calling Handley Page to a discussion of naval aircraft requirements.

At the Air Department headquarters above the Admiralty Arch, Handley Page and Volkert displayed drawings of the L/200 and sketches of its proposed twin-engined variants, M/200 and MS/200; but Sueter’s technical adviser, Harris Booth, preferred a very large seaplane for coastal patrol and dockyard defence, capable also of bombing the German High Seas Fleet before it ever left the safety of its anchorage at Kiel, and had already ordered prototypes from J. Samuel White & Co of Cowes. In view of Commander Samson’s urgent call from Flanders for a ‘bloody paralyser’ to hold back the German advance on Antwerp, Handley Page offered to build a land-based machine of this size, and very quickly a specification was drafted, discussed and agreed for a large twin-engined patrol bomber designated Type O, with a span of 114 ft and defined by general arrangement drawing No.628A.1; this specification was issued on 28 December, 1914, as the basis for a contract for four prototypes serialled 1372-1375. It called for two 150 hp Sunbeam engines, 200 gallons of petrol, 30 gallons of oil, a bombsight and six 100 lb bombs, a Rouzet W/T transmitter/receiver and a crew of two, with armour plate to protect all these items from small arms fire from below. Wing loading was not to exceed 5 lb/sq ft, but a top speed of 65 mph and ability to climb to 3,000 ft in 10 minutes were required. The aeroplane, with wings folded, had to be housed in a shed not larger than 70 ft square by 18 ft high and the sole defensive weapon was to be a Lee-Enfield Service rifle with 100 rounds of ammunition. The idea for this imaginative and practical ‘battleplane’ was fully approved and largely inspired by the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, whose enthusiasm for flying was a sore trial to his surface-bound colleagues, both naval and parliamentary; its specification was almost completely achieved, only the wing loading and overall height being exceeded in the final result, whose performance and utility in turn greatly exceeded the original requirements.

Geometrical simplicity was one of the keys to low structure weight, and Handley Page’s crescent wing gave way to an unstaggered straight-edged biplane layout for both mainplane and tail unit. Early in the discussions the problem of wing-folding resulted in the span being reduced to 100 ft, the slight increase in wing loading being offset by the prospect of 200 hp engines being available, but the Admiralty forbade any indication of horsepower in the revised type designation, which became O/100 by reference to the span; a surviving manuscript note from Meredith to Volkert dated 25 January, 1915, and headed ‘0/300’ may indicate the cause of the Admiralty’s concern over nomenclature. The rectangular-section fuselage was straight-tapered from wing to tail, with the top longerons horizontal. Forward of the wing the fuselage was short, with a blunt ‘chin’ surmounted by a glazed cockpit enclosure having a large V-shaped Triplex glass windscreen, rectangular Cellon side windows and a Cellon roof panel with an open hatchway; through this the observer could aim his rifle over a wide field of fire from a standing position almost astride the pilot’s seat, which was an ordinary cane garden chair. A 10-gauge manganese-steel armour plate protected the cockpit floor and the sides had 14-gauge armour-plating up to sill level, this assembly being known in the works as ‘The Bath’. The pilot’s controls comprised a large handwheel for the ailerons mounted on a tubular column rocking fore-and-aft for the elevators, and the usual rudder-bar; the narrow vertical instrument panel obscured very little of the excellent forward view. In designing the control surfaces, great care was taken to relieve the pilot of all unnecessary loads, the ailerons and elevators being aerodynamically balanced by full-chord horns taking in most of the bluntly rounded wing and tailplane tips; there were no ailerons on the lower wings, which were 15 ft shorter than the upper at each tip to give ground clearance when folded, the top overhang being braced by a triangular kingpost above each outer pair of interplane struts. The balanced twin rudders were pivoted between the tailplane rear spars and there was no fixed fin. Volkert preferred rigid tubular trailing edges to Harris Booth’s favourite flexible cord or cable, and restored the aileron area lost in reducing the overall span by locally increasing the chord so that the ailerons extended behind the fixed trailing edge, giving a characteristic planform to the upper wing. The lower wing-tips were at first drawn square, but Harris Booth insisted on rounding them to reduce drag. The two engines rotated in opposite directions to cancel out torque effects and were mounted midway in the gap as close to the fuselage as clearance for 11 ft four-blade airscrews would permit; each nacelle comprised a 100-gallon petrol tank made from 14-gauge armour plate, carried on two groups of steel-tube struts, with the engine bearers cantilevered in front of the tank and a long conical fairing attached at the back; this fairing had originally been blunt, but Harris Booth requested a long pointed tail, which was found to complicate the wing-folding and later shortened again. Each engine had armour plate underneath and at the sides and its radiator was mounted vertically above the petrol tank. In the original design, the undercarriage was of the well-established Farman pattern, with pairs of wheels on short axles tied by rubber cord to short fore-and-aft skids supported by struts directly below the nacelles, so that the weight of the engines and fuel was immediately above the wheels and local offset loading was avoided.

At Harris Booth’s request, a model of this layout was tested in the National Physical Laboratory wind-tunnel and found generally satisfactory, but detail structural design was more difficult, as Volkert found when he needed to stiffen the ailerons torsionally to take the reverse loading of the horn-balance tips; the solution he adopted was to reduce the horn area forward of the hinge, the resulting square-cut horn balance being found quite adequate; in fact it avoided the severe overbalance encountered by the Royal Aircraft Factory on the original ailerons of the B.E. 12a and F.E.9. The aerofoil section was RAF 6, and the wing was built round two spruce spars of rectangular section, spindled out to I section between strut attachments; the close-pitched ribs, though of light section, were very stiff when assembled. The hollow spruce compression struts between the front and rear spars were made from two spindled out rectangular pieces glued with their hollow faces together, the joints being reinforced lengthways by thin oak tongues (Patent No. 138006). The interplane struts were similar but had nose and tail fairings built on, the whole assembly being wrapped in glued linen tape before final varnishing. For ease of storage and erection, and to avoid using very long spars when Baltic and Scandinavian timber became scarce, the mainplanes were made in nine sections, the upper mainplane comprising the centreplane, two outer planes and two tip extensions, while the lower comprised two half centre planes and two outer planes. The fuselage was manufactured in four separate portions - front, centre, rear and tail - the latter two being permanently assembled with a scarfed and fish-plated joint in each longeron. All longerons and struts were carefully matched in cross-section to the local loads and, where extra thickness was necessary to provide stiffness, the members were built up, like the wing struts, from spindled halves glued together. Joints and strut fittings were fabricated from mild steel plates, ingeniously folded and brazed together, with fretwork holes between lines of maximum stress to save weight; nevertheless they were simple to produce in quantity with semi-skilled labour. To begin with, all internal bracing, and external bracing outside the slipstream, was by stranded cables, which naval artificers knew how to splice, although streamlined wires were required in the tail and centre bays. A sample of every part was weighed and tested to destruction to confirm weight and stress calculations, and numerous detail improvements were made as construction of the four prototypes proceeded, with sufficient lead-time between them to permit progressive refinement.

On 4 February, 1915, the basic design was substantially agreed by Captain W. L. Elder, including the substitution of new 250 hp Rolls-Royce vee-twelve engines for the original Sunbeams, as their greater power was obtained for less than a proportionate weight increase. On 9 February the contract was amended to cover four prototypes, 1455-1458, and eight production aircraft, 1459-1466. Initially it was intended to carry the bombs horizontally in a rotating cage enclosed in the fuselage, but as soon as the first few bombs had been released the cage became unbalanced and impossible to rotate. So a system of bomb suspension and release was devised which allowed up to sixteen 112-lb bombs to be hung from nose-rings in the same space as eight would have occupied in the cage. Concentration of the bomb load in the fuselage necessitated spanwise distribution of the landing gear, so the original design, with short cross-axles, was replaced by two separate chassis units with the outer wheels under the nacelles and the inner wheels under the longerons, with a clear space between units for the release of bombs. To accommodate the length of shock-absorber cord needed to prevent its extension being limited by the inextensible cotton-braiding, it was wrapped round the spreaders of telescopic struts of the type pioneered by A. V. Roe in the Avro 504, which the revised O/100 chassis resembled in principle; each unit had a vestigial central skid, reduced to a horizontal steel tube, with a braced swing axle on each side of it and a shock absorber strut on the outside of the wheel on each axle; the shock absorbers were faired by sheet metal casings and in production aeroplanes vertical steps were formed in the two innermost fairings to allow a clear path for the bomb tails. The bomb release gears (Handley Page Patent No. 17346 of December 1915) were mounted on four cross-beams in the fuselage above the bomb-cell floor, which was a square grid or ‘honeycomb’ with sixteen spring-loaded flaps separately pushed open by each bomb as it fell; under active service conditions, these flaps soon became worn and were more easily replaced by brown paper glued across the grid openings. Bombs could be dropped singly, in pairs, in salvoes of four, or all together. The revised landing gear, nacelle structure and wing hinges were covered by Patents Nos. 17066, 17067, 132478, 140276 and 144867, all dated December 1915.

The first prototype, 1455, was finished at Cricklewood during November 1915 and its components were taken to the requisitioned Lamson factory at Kingsbury for final erection; the complete fuselage was joined up at Cricklewood and towed along Edgware Road to Kingsbury by Handley Page personally in his Arrol-Johnston drop-head coupe. Late at night on 9 December two teams of naval ratings wheeled the assembled prototype, with wings folded, out on to the tramlines of Edgware Road; almost at once two tyres burst and had to be replaced; they were of the early beaded- edge pattern and were easily twisted off the rim. The procession restarted and all went well as far as the corner into Colindale Avenue, where the other two tyres burst. Overhead tramwires, telephone wires and gas lamp standards had already been removed on Admiralty orders and there was a reasonably clear passage along Colindale Avenue, but near the Hendon aerodrome entrance by the Silk Stream the way was blocked by trees in several front gardens. Calling for a ladder and a handsaw, Handley Page himself climbed up and removed the offending branches, taking no notice of protests from bedroom windows. None of these unfortunate residents ever claimed damages, but in due course the Gas Light & Coke Company sent Handley Page Ltd a substantial bill for the cost of removing and reinstating their street lamps; blandly Handley Page referred them to the Admiralty, stating that it had been a naval operation, not a commercial one, and eventually Their Lordships paid up. The three-quarter-mile journey had taken five hours and a further week had to be spent in final rigging and engine tuning, but by the morning of 17 December, 1915, there stood at Hendon, ready to fly, an aeroplane whose span was not much less than the total distance covered by Orville Wright’s first flight at Kitty Hawk, twelve years earlier to the day.

As the first two engines (Rolls-Royce numbers 2 and 3) had no turning gear, the only means of starting them was by pulling the airscrews round by hand; they could not be reached from ground level and it was unsafe to erect scaffolding or ladders close to moving blades, so a double ramp was contrived, which enabled a naval rating to run up one side within reach of the lowest blade and swing it as he passed down the other side. With a team of men it was thus possible to get the engines primed, after which they were started by turning the hand-magneto, provided the sequence was quickly carried out. Shortly before 2 p.m. on 17 December Lt-Cmdr J. T. Babington and Lt-Cmdr E. W. Stedman (formerly of the NPL staff) taxied to the downwind end of Hendon aerodrome, turned ponderously into wind and opened the throttles; to their relief they took off at 50 mph, flew straight and landed well short of the boundary. Overnight a number of slack bracing wires were tightened and next day another take-off was made, but Babington found that acceleration beyond 55 mph was negligible because of excessive drag. Handley Page blamed the large flat honeycomb radiators and Rolls-Royce recommended changing them to vertical tube units mounted on either side of the nacelle. So 1455 had to be grounded for two weeks while work went on night and day throughout the Christmas holiday, being finished in time for a third flight on New Year’s Eve. This time performance was much better and handling could be assessed at up to 65 mph; the ailerons and elevators were found to be heavy though effective, but the rudders were seriously overbalanced and their chord had to be extended 3 inches by strips added at the trailing edges. Control friction was high, particularly in the aileron circuit, and elasticity in the cables allowed random movements of the ailerons and elevators which the pilot had no means of damping out. The aileron controls were much improved by deleting the original internal cable and pulley system and substituting conventional external cables with longer levers on the ailerons. Impatient at the delay caused by these modifications, Murray Sueter ordered Sqn Cmdr A. M. Longmore to ferry the machine to Eastchurch forthwith and on 10 January, 1916, he and Stedman took off from Hendon without waiting for further trials; all went well apart from loss of power in the port engine, due to partial magneto failure, and some windscreen misting. A few days later Longmore began maximum speed tests, but at 70 mph the tail began to vibrate and twist violently, and he had to throttle back and land promptly. On inspection considerable damage was found in the rear fuselage structure, with badly warped longerons locally crushed by strut-ends, bowed struts and all cables slack. Handley Page and Volkert were quickly on the scene and drew up repair schemes for local reinforcement and reduction of the offsets which caused torsional stresses. The bowed struts were stiffened with kingposts and local crushing was eased by means of hardwood facings at the butt-joints. Unfortunately these modifications did nothing to check the tail vibration and a new weak point was found at the attachment of the wings to the bottom longerons, causing the angle of incidence to vary during taxying, so that take-off became impossible. This was cured by replacing the stranded cables in the fuselage by swaged tie-rods of high-tensile steel, and 1455 could then be flown consistently provided its speed did not exceed 75 mph, beyond which tail oscillation began once more. At the request of the Eastchurch pilots, the cockpit enclosure was removed, having already shown signs of collapse, and in the second prototype, 1456, the whole front fuselage was converted to a long tapered nose, with an open cockpit for the two crew members side by side and provision for a gunner’s cockpit in front of them. Deletion of the Triplex windscreen and armour-plate ‘bath’ saved over 500 lb in weight and the new nose was made long enough to keep the c.g. position unchanged, the new bottom longerons being swept up at the same angle as the upper ones were swept down. The new pilot’s position was 12 ft ahead of the wing leading edge, tending to exaggerate his control responses, and this was a further factor to be reckoned with in improving stability. In 1456 the whole nose back to the rear of the pilot’s cockpit was clad with plywood, but in 1457 and subsequent O/100s the plywood area was restricted to the curved part of the nose cockpit, the flat flanks being fabric- covered. Most of the nacelle armour was also discarded, although the weight of the tanks could not be reduced immediately. With a much strengthened fuselage structure incorporating massive reinforcement across the lower wing roots, 1456 was ready to be flown early in April 1916 by Gilford B. Prodger, an American who had come to Hendon a year earlier as chief instructor at the Beatty School and later formed a syndicate with Sydney Pickles and Bernard Isaacs for free-lance test-flying. Handley Page had attributed the tail oscillation to elevator over-balance and on 1456 the elevator horns were cropped square in the same way as the ailerons, so he was gratified when Prodger reported that the first flight up to 75 mph was quite steady. On 23 April, with ten volunteers aboard, Prodger climbed to 10,000 ft in just under 40 min and Handley Page invited the RNAS to witness acceptance trials on 7 May, when he called for sixteen volunteers to emplane and Prodger flew them to 3,000 ft in 8 1/2 min; a few days later Prodger improved on this by lifting twenty Handley Page employees to 7,180 ft, and on 27 May the RNAS took formal delivery and flew 1456 to a new aerodrome at Manston, which was more spacious than Eastchurch. During this flight it was difficult to maintain a compass course and evident that extra fin area was needed to compensate for the longer nose. This was contrived quickly by covering in the panel between the fore and aft inner tailplane struts above the starboard upper longeron. On 30 May high speed tests were begun again, but the tail oscillation recurred at 80 mph and above. Furthermore, there was an elevator ‘kick’ at take-off with full load which started the oscillation at a much lower speed, although this could be avoided by accelerating immediately after 'unstick’ while still in the ground cushion. The machine was still directionally unstable, but an attempt on 19 June to cure this by rigging the rudders with ‘toe-out’ only made matters worse. By this time, the tail oscillation problem had been referred by the Admiralty to the NPL and F. W. Lanchester agreed that the cause could not be simple structural weakness; he suspected dynamic resonance between engine vibration and the fuselage structure, but static tests on the third prototype, 1457, with the engines running at various speeds on the ground, proved negative. 1457 had a very stiff, completely redesigned, fuselage structure and was first flown on 25 June; it had a third crew position amidships, so Lanchester took the opportunity of flying in it with Babington next day, when the trouble began as soon as the speed reached 80 mph. He observed that the tail oscillation, at a frequency of about 4 cycles/second, caused the whole empennage to twist by as much as 15 degrees from the neutral position; he calculated that such a deflection would need a force of more than a ton to be applied at each tailplane tip if produced by a static test - a couple far greater than the pilot could apply through his controls. He deduced that this could only be caused by anti-symmetric movement of the port and starboard halves of the elevators, whose only interconnection was through long springy control cables, which ran separately to fairleads halfway along the rear fuselage; it was, in fact, one of the earliest reported cases of aero-elastic coupling. In R & M 276 Lanchester recommended positive interconnection of the two halves of each elevator; removal of the horn-balance area forward of the hinge-line (as first suggested by Handley Page himself) but retention of the full elevator span; also means for adjusting tailplane incidence during flight and extra bracing wires between both ends of the outer struts and the upper longerons. These measures were completely successful and the Admiralty, which had temporarily regretted having increased the original order from four to twelve in February 1915, had now vindicated its decision on 11 April to order a follow-on batch of twenty-eight (3115-3142) at a price of ?4,375 each, under contract No.CP 69522/15/X.

The fourth prototype, 1458, the first with a one-piece upper elevator, also had provision for armament, with a Scarff ring at the nose cockpit, two gun-pillars at the mid-upper position and a quadrant mounting to fire under the tail from the rear floor hatch, but was otherwise completed quickly to the same structural standard as 1456 and restricted to training duties. It was also the first to be fitted with 320 hp Rolls-Royce Mark III engines - newly named Eagles - which were installed before delivery from Hendon to Manston on 20 August. In the first twelve O/100s, 1455-1466, initially built with armoured nacelles, the nacelle tail fairings were long and tapered nearly to a point; they were hinged to the rear of the petrol tank and had to be swung inboard when the wings were folded, to clear the outer-plane bracing cables. In the second batch, 3115-3142, these fairings were shortened and blunted to clear the cables and could remain fixed. Wind-tunnel tests at the NPL in July 1916 showed a slight increase of drag with the shortened tail, but also that minimum drag was obtained with the nacelle reversed to point its tail upstream! It had been necessary to add an aerofoil section fuel gravity tank above the engine to avoid air-locks, and from 1461 onwards the total fuel tankage was increased by installing a cylindrical overload tank of 130 gallons in the fuselage above the bomb compartment; this increased range, but the higher take-off weight then necessitated a change in the size of the Palmer tyres from 800 x 150 mm to 900 x200 mm. Early in 1917 a shortage of Rolls-Royce Eagles was threatened and the third O/100 of the second batch, 3117, was built with 320 hp Sunbeam Cossacks, but these were heavier than Eagles for the same nominal power. 3117 was then sent to Farnborough for trials with uprated 260 hp RAF 3a engines after the War Office had staked a cautious claim in February 1916 with contract No. AS. 1198 for twelve O/100s (B8802-B8813) to be built at the Royal Aircraft Factory with these engines.

On completion of their acceptance trials, 1456 and 1457 remained at Manston as the nucleus of a Handley Page Training Flight formed in September 1916, while 1455 was rebuilt to production standard and 1458 was tested with new nacelles of lower drag and lighter weight. These had frontal honeycomb radiators with vertical shutters and deeper fuel tanks, no longer made of armour plate, giving a capacity of 120 gallons per nacelle or a total overload capacity per aircraft of 370 gallons; alternatively sixteen 112-lb bombs could be carried with the nacelle tanks full. Meanwhile the earlier nacelles were retained in production aircraft up to 3120 as these emerged from Kingsbury to be flown from Hendon to Manston, where they were armed and equipped for issue to RNAS units in France. Initially, the only such unit was the ‘Handley Page Squadron’, commanded by Sqn Cmdr John Babington from August 1916 and assigned to the 3rd Wing at Luxeuil-les-Bains, whence it was intended to raid steel foundries and chemical plants in the Saar valley. Babington himself, with Lieutenant Jones and Sub Lieut Paul Bewsher as crew, flew 1460 to Villacoublay at the end of October, having been preceded by 1459, which continued to Luxeuil according to plan; but Babington had to land in a very small field soon after taking off en route for Luxeuil, the resulting damage being repaired on site after some weeks’ delay. Meanwhile Lieutenant Waller in 1461 had force-landed at Abbeville with engine trouble en route for Villacoublay, but returned to service in December 1916. Only 1459 and 1460 were operated from Luxeuil by the 3rd Wing and the first O/100 action recorded was on the night of 16/17 March. 1917, when Babington in 1460 bombed an enemy-held railway junction southwest of Metz. The next two O/100s, 1462 and 1463, were due to leave Manston for Villacoublay on Christmas Eve 1916, but were delayed by minor engine trouble; on New Year’s Day 1917 they took off once more within 15 minutes of each other, but found unbroken cloud over the Channel. Sub Lieut Sands in 1462 reached Villacoublay by dead reckoning, but Lieutenant Vereker in 1463, with Lieutenant Hibbard and three other crew, went astray because of a compass error and on descending to an altimeter reading of 200 ft could find no break in the cloud, so they climbed back to 6,000 ft where they spent some time trying to fix their position. With fuel running low, they had to come down again and were able to land in clear air after sighting a church spire at an altimeter reading of 500 ft. They left their aircraft to enquire their position, but found too late that they were behind the German lines at Chalandry, near Laon; they hurried back to make an immediate take-off, but were met by an infantry patrol; in fact Vereker had already climbed up the entrance ladder, but was hauled down by the seat of his breeches, so he had no chance to set fire to the machine. Thus 1463 was captured intact, but Vereker refused to fly it again, so it was dismantled for transport to Johannisthal, where it was re-erected after detailed examination. Marked with the German Eisenkreuz, it was paraded with other captured Allied aeroplanes and is reputed to have been flown to 10,000 ft by Manfred von Richthofen at Essen in a demonstration before Kaiser Wilhelm II; but, before its performance could be fully assessed, it crashed after its aileron cables had been inadvertently crossed during maintenance work.

When the 3rd Wing at Luxeuil was disbanded to provide urgently needed reinforcements for the Royal Flying Corps on 30 June, 1917,1459 and 1460 were sent to join the 5th Wing at Coudekerque, whence daylight raids were made daily along the Belgian coast against U-boat bases at Bruges, Zeebrugge and Ostende, and later against other targets such as the long- range heavy shore batteries emplaced by the Germans along the dunes from Westende and Middelkerke to the Dutch frontier at Sluys. The first unit to operate at full strength was No.7 Squadron RNAS formed by combining O/100s from Luxeuil and Manston with the Short bombers remaining in ‘B’ Squadron of the 4th Wing after its Sopwith 1 1/2 Strutters had been transferred to the RFC. On 25 April four O/100s bombed and sank a German destroyer and damaged another, but 3115 was shot down into the sea off Nieuport and three of its crew of four were captured. After this, daylight sorties by O/100s were suspended and all efforts were concentrated against the docks at Bruges and the Zeebrugge canal where U-boats were repaired and revictualled. At first only moonlight raids were possible, the first being on 9 May, but by September night-flying training had so improved that only the worst weather prevented operations every night. The submarine pens, like the shore batteries, were strongly protected with concrete and progressively heavier bombs were needed to make any impression; apart from the Short 184 seaplanes of the Dover Patrol, only the O/100 could effectively carry the 520 lb ‘light case’ and 550 lb ‘heavy case’ bombs developed for these targets. On 28 July the 5th Wing was strengthened by the formation of No.7A Squadron at Coudekerque, which later became No. 14 Squadron and was trained exclusively for night bombing. It took over several of No.7’s earlier aircraft, including 1459, 1461 and 1462, as these were replaced from the second production batch, including 3116, 3118, 3123, 3125 and 3127. In September one flight of four O/100s from No. 7 was detached to Redcar to protect shipping entering and leaving the Hartlepools, where U-boats had been active inshore; on 21 September Flt Lieut Lance Sieveking (later well known in broadcasting) in 3123 dropped four bombs on a U-boat lying on the sea-bed, without apparent result; the flight remained at Redcar till 2 October, when it moved to Manston. Several of the O/l00s in use at this time had Scarff rings amidships and in all of them the nose Scarff ring was mounted below the level of the pilot’s cockpit.

In the spring of 1917 the Admiralty decided to conduct operational trials with the six-pounder Davis gun against the growing menace of inshore enemy submarines; this was a single-shot double-ended recoilless weapon, firing an explosive shell from the ‘active’ barrel and a dispersible fragmented charge of equal mass (a mixture of lead shot and vaseline) from the ‘recoil’ barrel; it was breech-loaded in the middle and electrically fired, being normally aimed at 30 to 60 degrees below horizontal to avoid damage to the aircraft from the recoil charge; it was mounted on a strong outrigged bracket on the nose, where it was not easy to reload in the air. On 7 September, 1917, 3127 was sent to Redcar with 50 rounds of ammunition, after earlier firing tests at Manston, using a prototype mounting bracket made by the Admiralty workshops at Battersea; blast damage to the upper wing had resulted at first from the recoil charge and had been overcome in July by raising the mounting and nose cockpit rim by 8 inches. In August, the same modification was applied to 1459, 1461 and 1462 and six-pounder Davis guns were fitted in them for urgent use at Coudekerque, but in December Dunkirk reported that the installation was not a success and in February 1918 the four guns and unspent residue of 500 rounds were withdrawn from service. Meanwhile the raised cockpit rim became a production modification from 3131 onwards (having also been fitted to 3124) and continued as a standard feature until the spring of 1918.

Early in 1917 the Dardanelles campaign had reached stalemate and Commodore Murray Sueter, transferred to the Mediterranean, called for a heavy long-range bomber to attack the enemy cruisers Goeben and Breslau, which had entered the Bosphorus soon after the declaration of war with Turkey in 1914. At first Sueter’s request was for a floatplane conversion of the O/100, because so much of the route from Mudros to Constantinople lay over water, but Handley Page resisted this proposal, and Sueter then ordered Handley Page to design and build folding wings for two Porte F.3 flying-boats, to be allotted serials N62 and N63 under contract No.AS. 17562. The wing design was completed and paid for, but construction was cancelled on 10 December, 1917; the designation Type T given to this project was also cancelled, as was Type S allotted to the O/100 seaplane. In May 1917 Sueter decided to divert 3124 from its intended Davis gun trials for urgent use by the 2nd Wing at Mudros against Goeben and Breslau, which would seriously threaten shipping in the Mediterranean if they could escape from the Dardanelles. On 22 May, 3124, fresh from the Cricklewood production line and specially equipped at Hendon, was flown to Manston and left next day for Mudros in a 2,000-mile dash via Villacoublay, Lyons, Frejus, Pisa, Rome (Centocelle), Naples, Otranto and Salonika in a flying time of 55 hours. Mudros was reached on 8 June and the crew comprised Sqn Cmdr Kenneth Savory DSC, Flt Lieut H. McClelland, Lieutenant P. T. Rawlings, Chief Petty Officer Adams and Leading Mechanic Cromack; in addition to hammocks and other personal gear, they carried a full set of aircraft spares including a stripped-down engine and two airscrews; the latter, being four-bladers, would not go inside the fuselage and had to be lashed on top of it. They made good progress to Otranto, where they found a collection of spares urgently needed at Mudros, so these were taken on board too, but the take-off weight then exceeded tons and Savory was unable to climb high enough to cross the 8,000 ft Albanian mountains. After two attempts to surmount this inhospitable terrain, Savory was compelled to offload the additional spares at Otranto and, after installing the spare airscrews in place of the original ones, succeeded in reaching Salonika at the third attempt, although the radiators froze and the crew were in danger from rifle shots from Albanian marksmen. The final stage to Mudros was uneventful and, but for the abortive starts and returns at Otranto, the flying time would have been only 31 hours. After thorough servicing at Mudros, Savory made two attempts to bomb Constantinople, on 3 and 8 July, both failing because of headwinds which compelled returns to base after reaching the Sea of Marmora, although other targets were bombed en route. On 9 July a third attempt succeeded, Constantinople being reached after a flight of 3 1/4 hours; arriving just after midnight, Savory circled over the city for half an hour at 1,000 ft, dropping eight 112-lb bombs on the Goeben in Stenia Bay, two more on the steamer General (being used as the German headquarters) and the last two on the Turkish War Office. In spite of a broken oil pipe which compelled him to shut down one engine on the homeward flight, Savory brought 3124 safely back to Mudros at 3.40 a.m. and was awarded a Bar to his DSC for the exploit. On 6 August 3124 bombed Panderma and for the rest of the month flew anti-submarine patrols in the Aegean, then on 2 September attacked Adrianople railway station with success; finally on 30 September Flt Lieut Jack Alcock, with Sub Lieuts S. J. Wise and H. Aird as crew, took off to bomb railway yards near Constantinople, but after 1 1/2 hours they were met by anti-aircraft fire and one engine failed from a broken oil-pipe; in the attempt to return to Mudros they were forced to ditch in the Gulf of Xeros near Suvla Bay and, although 3124 floated for over two hours, they were not seen and eventually had to swim ashore, finally reaching Constantinople as prisoners of war.

<...>

O/100 (Two Rolls-Royce Eagle II or IV or two Sunbeam Cossack)

Span 100 ft (30-5 m); length 62 ft 10 in (19-2 m); wing area 1,648 sq ft (153 m2). Empty weight 8,000 lb (3,630 kg); maximum weight 14,000 lb (6,350 kg). Speed 76 mph (122 km/h). Crew four.

Показать полностью

F.Manson British Bomber Since 1914 (Putnam)

Handley Page H.P.11 O/100

The manner in which Britain's air forces acquired their first truly successful heavy bomber was both a masterpiece of individual enterprise and an assembly of technical knowledge and experience of epic proportions, comparable by the standards of the time with those that characterised the Royal Air Force's acquisition of the Avro Lancaster almost a quarter century later. Size alone had not deterred other British manufacturers, such as J Samuel White, from venturing into the realms of very large aeroplanes, but none could compare with the sheer muscle of Handley Page's extraordinary O/100, whose prototype was first flown in under one year from the issue of its original specification.

Origins of the O/100 lay in an urgent message from that familiar naval officer, Charles Rumney Samson in Flanders, who pleaded with the Admiralty to send la bloody paralyser' with which to bomb the Germans to a standstill in their advance on Antwerp in December 1914. Implicit in this call was the need for very large aeroplanes, capable of laying a carpet of heavy bombs in the path of an advancing army, an extension of air power hitherto undreamed-of by the British War Office, but seized on at the Admiralty Air Department by Murray Sueter, the influential and energetic exponent of naval air power. Already, in line with advice by his technical adviser, Harris Booth, Sueter had placed an order for a very large bomber, the Wight Twin, and Harris Booth's own design, the A.D. 1000, was also under construction at East Cowes. Neither of these huge aeroplanes would prove successful.

Sueter, knowing that Frederick Handley Page seemed instinctively to 'think big', having embarked on a prewar design of a proposed transatlantic aircraft, the L/200, summoned him and his designer, George Rudolph Volkert, to the Admiralty to discuss the naval requirement for a heavy bomber. As a sequence to this discussion, Volkert prepared project drawings for a twin-engine land-based bomber, designated the Type O, with a wing span of 114 feet. Further discussion, however, disclosed certain mandatory limitations on the aircraft's overall size, necessitating folding wings, yet on 28 December 1914 the final specification was agreed and issued, and an order for four prototypes was placed.

The aircraft called for was required to be powered by a pair of 150hp Sunbeam engines with 200 gallons of fuel, was to be capable of carrying six 100 lb bombs and a bombsight, of climbing to 3,000 feet in 10 minutes and to have a crew of two. Armour protection from small arms fire was to be provided for crew, engines and fuel tanks, and a single Lee-Enfield rifle would suffice for self-protection. The aircraft was to be capable of storage within a 70-foot-square building, and a top speed of 65 mph at sea level was demanded; a wing loading of 5 lb/sq ft was not to be exceeded at all-up weight.

When one considers the capabilities of the aircraft of the time, this was indeed a demanding specification; after all, the 100 lb bomb was only just entering production, and the call for armour and folding wings imposed the need tor an extremely robust but relatively light airframe.

Design and component manufacture began immediately as Handley Page's Cricklewood factory worked round the clock, seven days a week. In the interests of low structural weight, Volkert favoured parallel-chord, straight-edged wings of unequal span, the upper wing being of 100 feet span, the lower of 70 feet (necessary for ground clearance when folded). The wings were of R.A.F.6 section, being built up on two rectangular-section spruce spars, spindled to I-section between strut attachments. Ailerons were fitted to the upper wings only, being horn-balanced outboard of the wing tips and extending aft of the wing trailing edge. Closely-spaced spruce wing ribs, reinforced longitudinally with oak tongues, imparted considerable torsional stiffness.

The fuselage was of rectangular section, the upper longerons being horizontal and the lower longerons providing taper upwards towards the tail. Built in three sections, the fuselage structure featured joint and strut attachments of mild steel, folded round the components and brazed together. An example of the careful attention paid to detail was provided by the deliberate choice of stranded cabling for internal bracing, being of the type capable of being spliced by any naval artificer.

The engines and fuel tanks were housed in armoured nacelles mounted at the centre of the wing gap, as close to the fuselage as the 11-foot propellers allowed. The radiators were mounted vertically atop the nacelles.

The two-man crew was located in a cabin in the short fuselage nose, enclosed by a deep V-shaped Triplex windscreen with transparent Cellon roof and side panels. The cockpit floor and sides up to the sills were of 10- and 14-gauge manganese-steel armour.

Every structural component was manufactured in duplicate so that a representative item could be tested to destruction in order to confirm stressing calculations, and a model of the complete aircraft underwent tunnel tests at the National Physical Laboratory.

Work had only been underway for a couple of months when Rolls-Royce announced that its new Mark II 250hp twelve-cylinder, water-cooled engine would be ready in time for the prototype's first flight and, on account of its much improved power/weight ratio, this engine was substituted for the Sunbeam.

In place of the a rotary bomb dispenser, originally intended to be incorporated in the centre fuselage with a load of eight bombs, it was decided to suspend the bombs vertically by nose rings, a change that allowed no fewer than sixteen 112 lb HERL (High Explosive, Royal Laboratory) Mark I bombs to be stowed in the space formerly occupied by the rotary dispenser. Such an increase in bomb load was made possible by the 60 per cent greater power available from the new Rolls-Royce II engines.

Manufacture of the first prototype Handley Page O/100 (an arbitrary designation that simply referred to the aircraft's wing span) was completed in November 1915, and final assembly took place in the requisitioned factory at Kingsbury. After being towed along the Edgware Road at night with its wings folded, No 1455 was ready at Hendon on 17 December for its maiden flight. Taken aloft that afternoon by Lt-Cdr John Tremayne Babington (one of the naval Avro 504 pilots who had taken part in the attack on Friedrichshafen on 21 November 1914) accompanied by Lt-Cdr Ernest W Stedman (later Air Vice-Marshal, CB OBE), the big aeroplane successfully rose above the grass for a short distance before landing and coming to a stop within the boundary of the field.

During the course of further testing it was found necessary to relocate the radiators to the sides of the nacelles and remove the cockpit enclosure and armour, modifications that reduced the aircraft's weight by some 500 pounds. Some tail oscillation resulted in extensive strengthening both of the rear fuselage and rear attachments of the wings to the fuselage.

The second prototype, No 1456, was first flown early in April 1916 by an American, Clifford B Prodger, and soon proved itself capable of exceeding all the performance requirements demanded. On 7 May this aircraft was formally accepted by the RNAS. The third aircraft, 1457, featured a much lengthened nose to maintain cg position without ballast for the reduced cockpit weight, and a third crew position for a midships gunner.

The fourth prototype, 1458, was the first to carry gun armament, being equipped with a Lewis gun and Scarff ring in the extreme nose, a pair of pillar mountings for Lewis gun on the midships dorsal position, and a ventral quadrant mounting for a Lewis gun to fire aft beneath the tail. No 1458 was also the first O/100 to be powered by the new 320hp Rolls-Royce Eagle III engines.

In due course, production orders for a total of 42 aircraft were placed, of which 34 were powered by Rolls-Royce Eagle IIs or IVs (Nos 1458-1466, 3115, 3116 and 3118-3141); No 3117 was fitted with a succession of experimental engines which included the R.A.F.3A and Sunbeam Cossack in conventional nacelles, and four 200hp Hispano-Suiza engines mounted in tandem in the two nacelles.

The majority of the initial batch of production aircraft was delivered to RNAS Manston in 1916 for pilot training with the Handley Page Training Flight, prior to delivery to operational units, the first of which was simply referred to as the Handley Page Squadron and assigned to the RNAS' 3rd Wing at Luxeuil-les-Bain under the command of Sqn-Cdr John Babington. The first O/100 to arrive at Luxeuil was No 1459, and the first operational sortie flown by the Squadron was a raid by No 1460, flown by Babington against a railway junction near Metz on the night of 16/17 March 1917. Unfortunately, in the meantime Lt H C Vereker, the pilot of an O/100, No 1463, had become lost during its delivery flight to Luxeuil on 1 January, and had landed his aircraft intact on the German-held aerodrome at Chalandry, near Laon. The Germans subsequently flew the aircraft to Johannisthal where it was, however, to be destroyed in a crash before any detailed evaluation could be completed by the enemy.

The 3rd Wing was to be disbanded on 30 June 1917, and two O/100s, Nos 1459 and 1460, were transferred to the 5th Wing at Coudekerque for daylight bombing attacks on the U-boat bases at Bruges, Ostend and Zeebrugge. The first Squadron to be extensivelv equipped with O/100s was No 7 (Naval) Squadron, RNAS, which took over the remaining aircraft from Luxeuil and Manston. Four of these bombers attacked German destroyers in daylight on 25 April, sinking one and damaging another, but losing one of their number. This led to the suspension of daylight attacks, and a change to night operations which included bombing raids on the heavily protected submarine pens in the Belgian ports. The 520 lb Light Case and 550 lb Heavy Case bombs had been specially developed for use against these targets, and the O/100 carried two such weapons.

In the meantime, Murray Sueter had left the Air Department and been posted to the Mediterranean. The Dardanelles campaign had reached stalemate, and Sueter requested that a Handley Page O/100, converted as a seaplane, should be sent out to Mudros for the purpose of bombing Constantinople (much of the route lay over water). Instead it was decided to despatch the standard O/100 No 3124 (hitherto intended for gun trials with a 6-pounder Davis gun in the nose) to Mudros and, flown by Sqn-Cdr Kenneth Savory DSC, this aircraft arrived on 8 June. After two attempts to reach Constantinople (each thwarted by headwinds), Savory finally succeeded and, on 9 July, dropped eight 112 lb bombs on the German cruiser Goeben, four more on a steamer being used as a German headquarters, and two on the Turkish War Office. No 3124 landed safely back at Mudros after a flight of almost eight hours, an exploit for which Savory was awarded a Bar to his DSC. The O/100 flew a number of other raids, but on 30 September it suffered engine failure and was ditched in the Gulf of Xeros; the pilot, Flt-Lt Jack Alcock (later of Atlantic crossing fame) and his crew were made prisoners of war.

The final production batch of six O/100s, B9446-B9451, was completed with Sunbeam Cossack engines, and was intended as an interim stage in the development of the Handley Page Type 12 O/400 bomber. They did not, however, reach an operational unit. Numerous other experiments were conducted on O/100s, including the installation of Fiat A.12bis engines in No 3142, being the power unit stipulated in a production order from Russia; this aircraft crashed before completion of the trials, and the onset of the Revolution put an end to Russian participation in the War.

The mention above o f the trials with a Davis 6-pounder recoilless gun in the nose of the O/100 requires further explanation. The trials were intiated by the Admiralty, who were becoming alarmed by increasing inshore activity by German submarines during the spring of 1917. A total of four O/100s, Nos 1459, 1461, 1462 and 3127 were fitted with these single-shot weapons in special mountings on the nose gunner's position. As the gun fired its shell the recoil force was dissipated by a rearwards-fired charge of fragmenting lead shot and grease which, it was intended, would pass over the aircraft's cockpit and upper wing. As the gun had to be fired at a considerably depressed angle of sight to avoid damage to the wing, it was extremely difficult to load and fire and, although three of the aircraft were delivered to the RNAS at Coudekerque in the autumn of 1917, the guns were scarcely used and were withdrawn from service early in 1918.

The O/100 bombers based in France with the RNAS continued to give excellent service during the second half of 1917, equipping Nos 7 and 7A Squadrons and dropping an impressive tonnage of bombs on all manner of targets behind the Western Front.

It was the increasing number of day and night raids by German bombers over south-east England during the latter half of 1917 that spurred the War Office to engage in strategic raiding of Germany at the earliest possible opportunity, and although requests for a transfer of naval O/100s to the RFC for this purpose fell on deaf cars, the considerable success achieved by these bombers encouraged the Government to sanction accelerated development and production of the improved Handley Page O/400, and it was to be this type that formed the heavy bombing element of the Royal Air Force's Independent Force, and the veteran O/100s began to be withdrawn from service in the spring of 1918.

Type: Twin-engine, four-crew, three-bay biplane heavy bomber.

Manufacturer: Handley Page Ltd, Cricklewood, London.

Powerplant: Production aircraft. Two 250hp Rolls-Royce Mk II (260hp Eagle II) twelve-cylinder, water-cooled engines driving four-blade propellers; also two 320hp Sunbeam Cossack engines. Experimental aircraft. Two 260hp Fiat A.12bis; and four (two tractor, two pusher) 200hp Hispano-Suiza engines; two Fiat A.12bis engines; two R.A.F.3A engines.

Structure: All-wood, ply- and fabric-covered; two-spar folding wings.

Dimensions: Span, 100ft 0in; length, 62ft 10 1/4 in; height, 22ft 0in; wing area, 1,648 sq ft.

Weights: Tare, 8,000 lb; all-up, 14,000 lb.

Performance: Max speed, 76 mph at sea level; climb to 5,000ft, 19 min 40 sec; service ceiling, 8,700ft; endurance, 8hr.

Armament: Bomb load of up to sixteen 112 lb bombs. Normal gun armament of two Lewis machine guns, one with Scarf! ring on nose gunner's cockpit and one on pillar mounting on midships gunner's cockpit; some aircraft carried a Lewis gun fitted to fire rearwards through hatch under the centre fuselage.

Prototypes: Four, Nos 1455-1458; No 1455 first flown by Lt-Cdr J T Babington at Hendon on 17 December 1915.

Production: Total of 42, excluding prototypes, all built by Handley Page: Nos 1459-1466, 3115-3142 and B9446-B9451 (Cossack engines).

Summary of Service: O/100s served with Nos 7, 7A, 14 and 15 Squadrons, RNAS, in France for bombing operations over Belgium, these units later becoming Nos 207, 214 and 215 Squadrons, RAF. One O/100 served at the RNAS Station, Mudros, in the Aegean for bombing operations against Constantinople. O/100s also flew with the Handley Page Training Squadron at RNAS Manston, Kent.

Показать полностью

P.Lewis British Bomber since 1914 (Putnam)

The Admiralty’s well-founded and wholly admirable policy of taking the offensive and punishing the enemy by bombing was responsible to a great degree for initiating the development of the Handley Page series of large bombing aircraft. Within the first few months of the start of the war the Admiralty had realized that, to implement such a scheme to the fullest extent, an aircraft was needed which could carry a worthwhile bomb load on patrol over water coupled with good endurance. A requirement was drawn up and issued in December, 1914, for a twin-engine two-seater capable of a minimum top speed of 72 m.p.h. and to carry six 112 lb. bombs.

Frederick Handley Page was already firmly convinced of the superiority of the large aircraft for load-carrying and was soon able to submit for the Admiralty’s consideration a design for a sizeable biplane with a pair of 120 h.p. Beardmores. The proposal was received with enthusiasm, with such warmth in fact, as to draw from the worthy and uninhibited Director of the Air Department, Commodore Murray F. Sueter, his classic and uncompromising demand for a ‘bloody paralyser’ of a bomber. The challenge was accepted with alacrity by Handley Page and his fellow-designer George R. Volkert, who redesigned the original layout as the H.P.11 designated O/100. Two 150 h.p. Sunbeam engines and a span of 100 ft. were specified. No time was lost in constructing the machine, which was ready in less than a year from receipt of the order.

Coincident with this activity in the Handley Page factory at Cricklewood was that in the Rolls-Royce works at Derby, where two new engines, eventually to become renowned as the Eagle and the Falcon, were being evolved specifically for aircraft use.

A pair of Eagles, each developing 250 h.p., were chosen for the O/100 and were installed as tractors in armoured nacelles. The cabin for the crew of 1455, the first prototype, was given bullet-proof glass and armour-plate as extra protection. The load of sixteen 112 lb. bombs was carried vertically internally in the centre part of the flat-sided, rectangular-section fuselage, which was constructed in three portions. To enable the O/100 to be housed in a hangar the wings were designed to fold. Of three-bay form, the upper tips overhung considerably and were braced with the usual kingposts and wire. A biplane tail was used, and the main undercarriage consisted of twin pairs of wheels.

The O/100 was most impressive in appearance and looked every inch the deadly bomber which it was intended to be. As soon as 1455 was completed it was taken by road in strict secrecy at night on 17th December, 1915, the short distance to Hendon for its first flight. Assembly was carried out rapidly within a few hours, so that, at 1.51 p.m. on 18th December, the O/100 was able to make a successful take-off piloted by Flt. Cdr. J. T. Babington. The attempt to provide improved crew comfort on long flights by the inclusion of the cockpit enclosure was short-lived, as the structure broke up in flight and was subsequently discarded. The major portion of the armour-plating around the crew was also taken away. No armament was fitted to the first few prototype O/100s, but those ordered to equip the R.N.A.S. were modified to incorporate a Scarff ring in the nose and upper and lower positions for Lewis guns in the fuselage to the rear of the wings.

Training in the use of the fine new bomber began at Manston, Kent, in September, 1916, and two months later, in November, the 5th Wing of the R.N.A.S. took delivery of its first O/100s at Dunkirk. After being employed on daylight coastal patrol and bombing for a few months, the O/100 was transferred to bombing during the hours of darkness, an operation in which it was increasingly successful despite a shortage of the machines.

Показать полностью

J.Bruce British Aeroplanes 1914-1918 (Putnam)

Handley Page O/100 and O/400

IN 1913 the Daily Mail offered a prize of £10,000 to be won by the pilot of the first aeroplane to fly across the Atlantic Ocean. One of the three aircraft which were designed and built for the express purpose of attempting the trans-Atlantic flight was the Handley Page L/200, a large single-motor biplane which had a 200 h.p. Salmson engine. This machine’s capabilities were never put to the test, for the war began before it was completed.

The historical significance of the Handley Page L/200 lies in the fact that it was the first expression of Mr Handley Page’s belief in the advantages inherent in large aeroplanes, particularly when it was essential to carry a heavy load.

This belief found further expression when, in December, 1914, the Admiralty issued a statement of their requirements for an aeroplane capable of making oversea patrols with a load of bombs. The specification required the aircraft to have two engines, to carry a crew of two and six 112-lb bombs, and to have a maximum speed of at least 72 m.p.h. The Handley Page design which was shown to Commodore Murray F. Sueter, then the Director of the Air Department of the Admiralty, was for a large biplane powered by two 120 h.p. Beardmore engines. The design impressed him, as also did Mr Handley Page’s faith in big aeroplanes. Apparently determined to outdo even the ambitious requirements of the original specification, Commodore Sueter asked Mr Handley Page to provide a “bloody paralyser” of an aeroplane. That specification may have been technically vague, but the interpretation of it was magnificent.

Assisted by G. R. Volkert, Mr Handley Page revised the design accordingly, and an order was given for the construction of the machine. The re-designed aircraft had a longer nose than the original project; two 150 h.p. Sunbeam engines were to replace the Beardmores, and the wing span was no less than 100 feet.

Construction began immediately, and the Handley Page factory worked seven days a week to complete the O/100, as the new machine had been designated. It presented many problems, for it was larger than any aeroplane which had been built in this country up to that time. No one had any practical experience of the construction of aircraft of such size, and every spar, strut and fitting was tested to destruction before it was fitted; yet the prototype was flown less than a year after the date of ordering.

While the O/100 was being built, the Rolls-Royce company were developing the two aero-engines which were to win distinction as the Eagle and Falcon. By August, 1915, the engine which was later to be known as the Eagle had shown itself to be capable of developing 300 h.p. at 2,000 r.p.m., but to ensure reliability in running the engine was rated at 250 h.p. at 1,600 r.p.m. Two of these Rolls-Royce engines were installed in the O/100.

The engines were mounted in armoured nacelles, each of which contained an armoured fuel tank. The crew had an enclosed cabin, and were protected by bullet-proof glass and armour plate.

The completed O/100 was transported by road from Cricklewood to Hendon during the night ol December 17th/18th, 1915, and took off for the first time at 1.51 p.m. on the 18th. As the trials of the aircraft progressed, various modifications were made. One of the first was the removal of the cabin enclosure: in the course of a flight from Hendon to Eastchurch the cabin collapsed and was never used again. Most of the armour plate was also removed. The official trials of the O/100 were carried out at Eastchurch, beginning in January, 1916.

For the structure of the O/100, its designers wisely contented themselves with adhering to the type of construction with which they were familiar; but it had to be carried out on a much larger scale than anything that had gone before. The fuselage was a cross-braced box girder which was built in three parts: the central portion embodied the bomb bay, and to it were attached the nose and tail portions. The longerons of the tail portion were of hollow spruce, but elsewhere solid spruce was used.

The wings were also built in sections, the upper in five and the lower in four. The box spars and all interplane struts were built up, and large horn-balanced ailerons were fitted to the upper wings only. The long extensions of the upper wing were braced from king-posts immediately above the outermost interplane struts. The great size of the O/100 presented problems of accommodation, and the wings were made to fold to conserve hangar space.

The tail-unit was a biplane structure, and the vertical surfaces consisted of a single central fin and two outboard rudders: the fin was mounted on top of the fuselage and, on the O/100, had its leading edge in advance of the tailplane. There were four separate horn-balanced elevators. The incidence of the tailplane could be altered on the ground only.

The original elevators were not satisfactory. The trouble lay in their horn balances, which were experimentally stripped of their fabric in an endeavour to find a remedy; but finally all save only a very small portion of balance area was removed completely. No attempt was made to modify the shape of the horizontal tail surfaces, and the O/100 was left with the overhanging elevators which became a well-known characteristic of the type.

The engines were mounted midway between the wings and drove tractor airscrews of opposite hand. The nacelles of the O/100 were, of necessity, long, for each accommodated one of the main fuel tanks, and their tail fairings extended well behind the rear interplane struts. The basic structure of each nacelle was of steel tube. Frontal radiators with vertical shutters later replaced the divided, side-mounted radiators which appeared on some of the early O/100s.

The undercarriage was a substantial but somewhat complicated affair, built almost wholly of faired steel tube. Each wheel had a large shock-absorber, and 800 X 150 mm or 900 X 200 mm tyres were fitted. There were no brakes: reliance was placed upon the massive sprung tail-skid for braking purposes.

The prototypes had no provision for defensive armament; but production O/100s had a cockpit in the extreme nose of the fuselage, surmounted by a Scarff ring-mounting, and positions were provided behind the wings both above and below the fuselage. The bombs were suspended by their noses inside the fuselage; the bomb-cells were closed by spring-loaded doors which opened under the weight of the falling bomb.

Forty O/100s were delivered to the R.N.A.S., beginning in September, 1916, with those which went to Manston to equip the training squadron there. This total included the prototypes, which were modified to production standard before delivery. It was originally intended that the O/100 should be produced by Mann, Egerton & Co., Ltd., of Norwich. For the purpose, that firm had a special large building erected urgently in the space of only six weeks early in 1916. Owing to a change in official plans, however, the planned production did not take place, and Mann, Egerton & Co. built Short Bombers instead of O/100s.

The first operational unit to receive the big Handley Page was the R.N.A.S. 5th Wing at Dunkerque, which received its first O/100 in November, 1916. It was flown to France by Squadron Commander John Babington, with Lieutenant Jones and Sub-Lieutenant Paul Bewsher as crew; and it was followed two weeks later by a second machine flown by Sub-Lieutenant Waller.

After a false start on Christmas Eve, 1916, the third Dunkerque-bound O/100 set course for France just before noon on January 1st, 1917. Its crew were Lieutenant Vereker (pilot), Lieutenant Hibbard (observer), Leading Mechanics Kennedy and Wright, and Air Mechanic First Class W. W. Higby. It was followed about a quarter of an hour later by a fourth machine (Sub-Lieutenant Sands, W. Poile, S. Bassett and D. E. Wade). Third time was unlucky for the O/100, for the third machine was delivered intact to the enemy and had no opportunity to demonstrate the warlike qualities implied in the name of “La Amazon” which had been given her by her crew. After flying for some time over and in unbroken cloud, Vereker landed in the first suitable field he saw after breaking cloud at 500 feet. By bad luck the field was twelve miles inside enemy territory near Laon, and an example of Britain’s latest aerial weapon was delivered undamaged into the enemy’s hands.

German reports indicate that the O/100 was investigated with proverbial Teutonic thoroughness, and it is said that it was once flown by Manfred von Richthofen. For propaganda purposes at the time it was alleged that the design of the German Gotha bombers was copied from or at least inspired by the O/100, and unfortunately that fable survived the war and gained considerable credence. The Gotha went into production in the autumn of 1916, and a German official memorandum issued at that time stated that thirty Gotha G.IVs would be ready by February 1st, 1917. The first production Gothas were in fact delivered to German bombing squadrons in that month. Apart from the date’s incompatibility with any copying of the British design, the Gotha was a totally different aeroplane from the Handley Page, and was not even comparable in size.

The three O/100s which reached France safely were the only Handley Pages to go there until the beginning of April, 1917, when four went to Dunkerque to form the nucleus of No. 7 Squadron, R.N.A.S. At least one machine went to the R.N.A.S. 3rd Wing at Luxeuil. Early Service use of the O/100 recalled the terms of the original Admiralty specification of December, 1914, for No. 7 Naval flew their machines on daylight patrols off the coast. On April 23rd, 1917, three O/100s, each loaded with fourteen 65-lb bombs, attacked five German destroyers off Ostend and left one listing badly after being stopped by several direct hits.

Three days later, however, an O/100 was brought down in a similar exploit and was lost. The type was thereafter withdrawn from daylight operations and confined to night bombing, a duty which had been pioneered some six weeks earlier by a single O/100 of the R.N.A.S. 3rd Wing which attacked the railway station at Moulin-les-Metz on the night of March 16th/17th, 1917.

The O/100s were so few in number that for some weeks the night raids were carried out by single machines. Nevertheless, a single O/100 was a potent weapon in its day. Whereas the Short Bombers of the R.N.A.S. 5th Wing could carry only eight 65-lb bombs, each O/100 could take up to sixteen 112-pounders. To transport an equal load of bombs six D.H.4s were required, and their fuel consumption was 120 gallons per too miles as against the 54 gallons per 100 miles of the O/100. Moreover, the crews of the D.H.4s would total twelve men, whereas the O/100 required only a pilot and two observers.

The Handley Pages of the 5th Wing bestowed their nocturnal attentions upon the enemy destroyer and U-boat bases at Bruges, Ostend and Zeebrugge; while in the south of France the 3rd Wing’s attacks on enemy industrial centres paved the way for the strategic operations of the Independent Force in the following year.

In the preparations for the British offensive of 1917 in Flanders, the Dunkerque O/100s assisted by bombing enemy railway centres, notably in and around the Thourout-Cortemarck-Lichtervelde railway triangle. By the middle of August, 1917, R.N.A.S. Squadrons Nos. 7 and 7A possessed a total of twenty O/100s. No. 7A had been formed from a nucleus provided by No. 7 during the previous month, and was itself to provide the nucleus for the formation of No. 14 (Naval) Squadron, which was formed on December 9th, 1917. Some of these O/100s dropped 9 1/2 tons of bombs on the Thourout-Cortemarck-Lichtervelde triangle during the night of September 25th/26th, 1917. Thereafter they confined their attentions to the aerodromes from which the Gothas flew to bomb England, and made life unpleasant on the enemy aerodromes of Gontrode and St Denis Westrem.

By this time, however, four of their number had been withdrawn to Redcar on September 5th, 1917, in an endeavour to counteract the increasing depredations of enemy submarines off the mouth of the Tees. These O/100s made inshore patrols for four weeks, and bombed seven of the eleven submarines they sighted during that period. None of the U-boats was sunk, but the presence of the Handley Pages made an improvement in the area.

On October 2nd, 1917, the four O/100s were transferred to Manston as the nucleus of a new bomber squadron. This squadron was originally called “A” Squadron, and was formed for the purpose of making strategic raids against industrial centres in southern Germany. Led by Squadron Commander K. S. Savory, Naval “A” Squadron flew to Ochey to join the 41st Wing on October 17th, 1917. The Wing was the beginning of the Independent Force, R.A.F.

Nine Handley Pages of Naval “A” Squadron opened the 41st Wing’s night-bombing offensive on the night of October 24th/25th, 1917, when they accompanied sixteen F.E.2b’s of No. too Squadron, R.F.C., in an attack on the Burbach works near Saarbrucken. In January, 1918, Naval “A” Squadron was redesignated No. 16 (Naval) Squadron, and remained on night-bombing duties until the Armistice.

Only one O/100 was used outside the European theatre of war. In June, 1917, this machine flew from England to Mudros on the island of Lemnos in the Aegean Sea, whence the R.N.A.S. launched a bombing offensive against the Turks in July. The 2,000-mile flight was accomplished in a flying time of 55 hours.

It was a remarkable achievement at that time, and was made by way of Paris, Rome and the Balkans: while crossing the Albanian Alps at 10,000 feet the water in the radiators froze. The crew of the Handley Page were Squadron Commander K. S. Savory, Flight-Lieutenant H. McClelland, Lieutenant P. T. Rawlings, R.N.V.R., Chief Petty Officer 2(E) J. L. Adams, and Leading Mechanic (C) B. Cromack. The O/100 carried a spare engine, two spare airscrews, hammocks, tents, and a full set of spares; the aircraft weighed 6 1/2 tons at take-off.

The chief reason for taking an O/100 to the Aegean was to provide means for bombing Constantinople, a flight of some 200 miles from Mudros. After two abortive attempts, Squadron Commander Savory reached the objective shortly before midnight on July 9th, 1917, and was over the target area for thirty-five minutes, during which time twelve 112-lb bombs were dropped. After nearly three months spent in short-range bombing and anti-submarine patrol, the Handley Page again took off for Constantinople on September 30th, 1917, with Flight-Lieutenant J. Alcock at the controls; but engine failure brought the big machine down in the Gulf of Xeros and all the crew were taken prisoner.

<...>

SPECIFICATION

Manufacturers: Handley Page, Ltd., Cricklewood, London.

Other Contractors: The Birmingham Carriage Co., Birmingham; Clayton & Shuttleworth, Ltd., Lincoln; The Metropolitan Waggon Co., Birmingham; National Aircraft Factory No. 1, Waddon; The Royal Aircraft Factory, Farnborough, Hants.; The Standard Aircraft Corporation, Elizabeth, New Jersey, U.S.A.

Power: O/100: two 250 h.p. Rolls-Royce Mk. II (266 h.p. Eagle II); two 320 h.p. Sunbeam Cossack; four 200 h.p. Hispano-Suiza (experimental installation).

Dimensions: Span: upper 100 ft, lower 70 ft. Length: 62 ft 10 1/4 in. Height: 22 ft. Chord: 10 ft. Gap: 11 ft. Stagger: nil. Dihedral: 4°. Incidence: 3°. Span of tailplanes: 16 ft 7 1/2 in. Track of each undercarriage unit: 4 ft 6 in. Airscrew diameter: 11 ft.

Areas: Wings: 1,648 sq ft. Ailerons: each 86 sq ft, total 172 sq ft. Tailplanes: 111-6 sq ft. Elevators: 63 sq ft. Fin: 14-7 sq ft. Rudders: 46 sq ft.

Tankage: O/100: petrol - 130-gallon tank in fuselage, one 120-gallon tank in each nacelle; total 370 gallons; oil - two 12-gallon tanks.

Armament: The O/100 could carry up to sixteen 112-lb bombs.

Service Use: O/100: R.N.A.S. Squadrons Nos. 7, 7A (later No. 14 Naval and No. 214 R.A.F.) and “A” (later No. 16 Naval and No. 216 R.A.F.). R.N.A.S. 3rd Wing at Luxeuil. Training Squadron at Manston. Aegean: One O/100 flown from R.N.A.S. Station, Mudros.

Production and Allocation: Forty-six O/100s were built.

Notes on Individual Machines: 3116: the first O/100 to land at Coudekerque. 3117: experimental installation of four 200 h.p. Hispano-Suiza engines. 3135: R.N.A.S. 5th Wing, Coudekerque, markings “B 3” on fuselage. 3138: O/100 modified to become O/400 prototype. �

Serial Numbers:

Serial Numbers Contractor Contract No. Specified Engines

Handley Page O/100 :

1455-1466 Handley Page C.P.65799/15 Eagle

3115-3142 Handley Page C.P.69522 Eagle

B.9446-B.9451 Handley Page A.S.20629 Cossack

Costs:

Airframe without engines, instruments or armament £6,000 0s.

Rolls-Royce Eagle Mks. II and IV (each) £1,430 0s.

Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII (each) £1,622 10s.

Sunbeam Maori (each) £1,391 0s.

Fiat A. 12bis (each) £1,617 0s.

Liberty (each) £1,215 0s.

Показать полностью

O.Thetford British Naval Aircraft since 1912 (Putnam)

Handley Page O/100

It is not always appreciated that the Admiralty was the first of the British Service Departments to recognise the potentialities of the large aeroplane for long-range bombing work, and that it made its requirements known to the industry as early as December 1914. The O/100, the forerunner of the much better known O/400, was the outcome of this policy and the answer to Commodore Murray F Sueter's classic request, when Director of the Air Department of the Admiralty, for a 'bloody paralyser' of an aeroplane.

The prototype O/100, with an enclosed cabin for the crew, flew for the first time at Hendon on 18 December 1915. Later the cabin was removed and, also, most of the armour plating. Deliveries of production aircraft to the RNAS began in September 1916, and the first front-line unit to receive the type was the Fifth Naval Wing at Dunkirk in November 1916. The third O/100 for the RNAS was delivered to the enemy intact on 1 January 1917, due to a navigational error.