Книги

Centennial Perspective

C.Owers, J.Herris

Hannover Aircraft of WWI

280

C.Owers, J.Herris - Hannover Aircraft of WWI /Centennial Perspective/ (46)

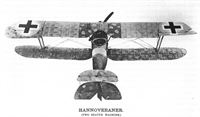

View of 13199/17 at an Air Depot in France after capture. A Sopwith Camel is undergoing repair in the background.

Hannover Aircraft Orders & Production, 1915-1919

Known Serials Quantity Comments

Aviatik C.I(Han)

1951-1974/15 24 1951/15 type test February 1916

600-649/16 50

2100-2123/16 24 2114/16 type test August 1916

2764-2787/16 24

3367-3390/16 24 Total 146 built

This Aviatik C.I was built by Hannover as shown by the tapered cooling louvres by the crewman. The first aircraft Hannover built was the Aviatik C.I(Han); 24 of these were ordered from Hannover in late 1915.

Hermann Dorner was born on 27 May 1882 in the Luther-Haus in Wittenberg. His father, a professor of theology, was transferred to Konigsberg/Ostpreussen (nowadays Kaliningrad) and the young Dorner made his first attempts at gliding as a teenager at Cranz on the Baltic coast. After carrying out his military service by serving for a year in the navy he obtained his Diplom-Ingenieur in shipbuilding at the Technical University of Charlottenburg in 1906. A year later he resumed his flight tests in Deutschwusterhausen near Berlin with a self-made monoplane glider with three wheels. Unlike Lilienthal, who used gravity as the propulsion for his gliding flights down the slope of a hill, he chose horizontal flight and let himself be pulled by a galloping horse with a long rope. Initial failures and crashes did not discourage him and finally he managed flights up to 80 m in length and 7 m in height with subsequent flawless landings, first in a lying position, and then sitting.

He then desired to achieve powered flight. As there was no commercially available engine suitable for his needs, he designed his own, an air-cooled four-cylinder engine with combined intake and exhaust valve, that was built in 1908 by the Schwager Company. His new high wing monoplane made a few successful aerial jumps and this encouraged him to register for the Johannisthal "International Flight Week" in September 1909. He could not achieve much with his untested monoplane, the prizes were taken by the French pilots taking part, but he learned a lot from them.

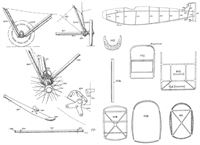

The 1909 monoplane had an 18-hp Dorner engine in the fuselage nose with a chain driven airscrew above. The wing was adjustable in flight and spanned 11.80 m. The tail surfaces were carried on a slender boom.

With an improved monoplane, which was equipped with a redesigned 22-hp water-cooled engine, Dorner won the "3rd Lanz Prize of the Skies" on 11 July 1910, amounting to 3,000 marks and immediately thereafter his pilot's license (No. 18). In September of the same year he founded the Dorner Flugzeug GmbH and moved to the aeroplane shed No. 9 in Johannisthal where he started a flight school. He trained a few student pilots, and employed the Swiss pioneer aviator Robert Gsell. He continued to develop larger and more powerful versions of his monoplane. Accidents and the lack of military orders to abandon aeroplane manufacturing in 1912, and the following spring, Goetze, his chief executive officer took over the facility. The company was liquidated in the summer of 1913.

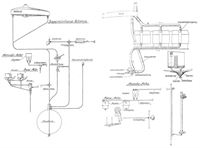

Dorner Aircraft

The T II monoplane had a 22-hp Dorner water-cooled engine and the frontal radiators were mounted on a low tubular steel frame with the spring-loaded wooden chassis axle. The pilot's seat was behind the engine. The wing was supported by struts and used wing warping control. The rear section of the fuselage was open. The drive shaft from the engine passed under the pilot's seat and a long chain transmission drove the pusher propeller mounted high behind the wing. This machine was built in 1910 but it burned after a few flights when a cylinder head tore off in the shed during a test run.

Span 11.6 m; Empty weight 320 kg; AUW 430 kg; Speed 65 km/h.

The T.III monoplane had a 40-hp NAG, 40-hp Korting or 50-hp Dixi engine. It was similar to the T II but a two-seater with dual controls. On 6 June 1911, Georg Schendel (pilot's license No 63) crashed fatally at Aldershof with his mechanic Voss, in a T III. In December 1911, Robert Gsell demonstrated a machine with a 50 hp Daimler in Doberitz for the military administration, which ordered a more powerful prototype.

Span 12.35 m; Speed 85 km/h.

The monoplane that was built to the military order by Dorner was similar to the T III but had a 70-hp Daimler engine and an enclosed fuselage for the engine and seats. Delivered in 1912, there were no further orders because the chain transmission repeatedly led to malfunctions and accidents.

Speed quoted as 110 km/h.

He then desired to achieve powered flight. As there was no commercially available engine suitable for his needs, he designed his own, an air-cooled four-cylinder engine with combined intake and exhaust valve, that was built in 1908 by the Schwager Company. His new high wing monoplane made a few successful aerial jumps and this encouraged him to register for the Johannisthal "International Flight Week" in September 1909. He could not achieve much with his untested monoplane, the prizes were taken by the French pilots taking part, but he learned a lot from them.

The 1909 monoplane had an 18-hp Dorner engine in the fuselage nose with a chain driven airscrew above. The wing was adjustable in flight and spanned 11.80 m. The tail surfaces were carried on a slender boom.

With an improved monoplane, which was equipped with a redesigned 22-hp water-cooled engine, Dorner won the "3rd Lanz Prize of the Skies" on 11 July 1910, amounting to 3,000 marks and immediately thereafter his pilot's license (No. 18). In September of the same year he founded the Dorner Flugzeug GmbH and moved to the aeroplane shed No. 9 in Johannisthal where he started a flight school. He trained a few student pilots, and employed the Swiss pioneer aviator Robert Gsell. He continued to develop larger and more powerful versions of his monoplane. Accidents and the lack of military orders to abandon aeroplane manufacturing in 1912, and the following spring, Goetze, his chief executive officer took over the facility. The company was liquidated in the summer of 1913.

Dorner Aircraft

The T II monoplane had a 22-hp Dorner water-cooled engine and the frontal radiators were mounted on a low tubular steel frame with the spring-loaded wooden chassis axle. The pilot's seat was behind the engine. The wing was supported by struts and used wing warping control. The rear section of the fuselage was open. The drive shaft from the engine passed under the pilot's seat and a long chain transmission drove the pusher propeller mounted high behind the wing. This machine was built in 1910 but it burned after a few flights when a cylinder head tore off in the shed during a test run.

Span 11.6 m; Empty weight 320 kg; AUW 430 kg; Speed 65 km/h.

The T.III monoplane had a 40-hp NAG, 40-hp Korting or 50-hp Dixi engine. It was similar to the T II but a two-seater with dual controls. On 6 June 1911, Georg Schendel (pilot's license No 63) crashed fatally at Aldershof with his mechanic Voss, in a T III. In December 1911, Robert Gsell demonstrated a machine with a 50 hp Daimler in Doberitz for the military administration, which ordered a more powerful prototype.

Span 12.35 m; Speed 85 km/h.

The monoplane that was built to the military order by Dorner was similar to the T III but had a 70-hp Daimler engine and an enclosed fuselage for the engine and seats. Delivered in 1912, there were no further orders because the chain transmission repeatedly led to malfunctions and accidents.

Speed quoted as 110 km/h.

Hannover Aircraft Orders & Production, 1915-1919

Known Serials Quantity Comments

Halberstadt D.II(Han)

800-829/16 30 800/16 type test October 1916

Known Serials Quantity Comments

Halberstadt D.II(Han)

800-829/16 30 800/16 type test October 1916

Hannover CL.II and Halberstadt aircraft of Schlachtstaffelgruppe D. Note the white tail of the machine in flight.

Mystery Biplane

The arrival of the Hannover CL.II at the Front in October 1917 appears to have taken the Allied intelligence agencies by surprise. James McCudden wrote that the Allies first described it in February 1918, some three months after he had first seen one. The British Ministry of Munitions issued monthly Intelligence Reports on "Enemy Aviation for the Month of..." usually published a month or two later. These also contained translations of French reports. That for January 1918 (issued in March) contained translations of a French report on a new artillery ranging and reconnaissance aeroplane - a two-seater of a new type driven down in our lines in December, and caught fire on landing. The following particulars were able to be obtained:

100-hp six-cylinder in-line Opel engine; fuselage ply wood, biplane tail. Armament - two machine guns. This was a Hannover CL.II but its origin could not be determined from the wreckage. The new aircraft created a lot of interest as evidenced by articles in the aviation press.

The 1-15 January 1918 issue of l’Aerophile contained a two-page article entitled "Hammover?" It included sketches of the mysterious biplane tailed German two-seater. This was followed by another two-page spread in the 1-15 March 1918, edition, where "L'Avion Allemand H.W. Hannovranner ou Plutot Halberstadt" was discussed. The 22 May 1918, issue of The Aeroplane’s supplement "Aeronautical Engineering", showed sketches of the "New Halberstadt". The article quoted M. Lagorette of the French magazine L’Aerophile as stating that these curious machines with biplane tail "is most certainly not a Hannover but a Halberstadt." Although several had been shot down, they had been so badly wrecked or burnt that a reconstruction was not possible. Lt Mussat, commanding a battery of AA guns, made a sketch of the machine and "insists that the fuselage is extremely deep." Lagorette suggested that since no trace of cabane struts were found in the wreckage of those shot down, the upper wing must be mounted on the fuselage as in the Roland.

The British journal Flight published sketches of "A German "Mystery" Biplane - The H.W." on P.444 of its 25 August 1918, issue. "From time to time reports have been received of a certain type of German aeroplane having a biplane tail being observed at the front. Reports differed considerably as to the exact shape of the machine generally, but all appeared to tally regarding the biplane tail... Now however, one of these machines has been brought down on the French front, but unfortunately the smash and subsequent fire did not leave much on which to base a reconstruction of the machine. The only clue to its identity appears to be that it was marked H.W." This was identified as being either Halberstadt Werke or Hannover Werke. In its 31 May 1918, edition, Flight published a note from a correspondent that identified the machine as an H.W.F. (Hannoversche Waggon Fabrik) machine and included a sketch of the aircraft. The deep fuselage in side elevation was mentioned and the two-seater "is generally camouflaged with its crosses painted inside white circles."

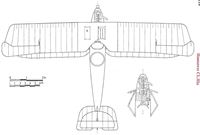

The Confidentiel French booklet for aerial observers, Silhouettes D’Avions - Allies et Ennemis, published in May 1918, showed the mystery biplane as the Hannovraner (sic) D with drawings showing their reconstruction of the machine.

Now properly identified, the Hannover biplanes were to continue to be a thorn in the sides of the Allies until the end of the war.

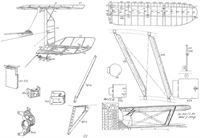

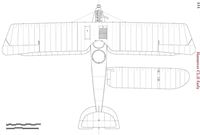

Hannover CL.II

Dorner's first design for Hawa was the Hannover Type 3a biplane. It appears that the Type 3a was built without Idflieg financial support as a private venture. The deep fuselage was to be a feature of Hannover machines. A single fixed synchronised LMG 08/15 machine gun was provided for the pilot and a flexible LMG 14 machine gun mounted on a wooden turntable was provided for the gunner. The biplane tail, that became a Hannover characteristic, gave the gunner a better field of fire aft than a conventional tailplane. Idflieg required that the 180-hp Argus As.III engine be used. Unfortunately, the Argus was chosen before it had been given a proper front-line evaluation. When fitted to the LFG Roland D.II the engine had proved disappointing in combat as the engine fell off in power as the altitude increased, however for the altitudes that the CL types would operate at, the engine was considered adequate.

Arriving at the Front in October 1917 the CL.II proved an immediate success. Issued singly to reconnaissance squadrons as escorts to provide protection to the C-class machines the CL.II soon showed that its mettle. It proved more versatile beyond escort or ground-attack work. The fuselage was able to accommodate a camera and wireless equipment that the observer was able to operate with ease in the roomy fuselage. The CL.II was then operated as an all-round short range, low-altitude reconnaissance machine. The biplane was very manoeuvrable and could bank steeply without losing altitude and German crews found that they could accept or break off combat with enemy fighters with confidence. A maximum of 295 machines were at the front in February 1918, after which the CL.II was gradually phased out.

The CL.II was followed by the CL.Ill that used the Mercedes D.III engine for better altitude performance, however the demand for this engine in single-seat fighters led to Dorner having to redesign the machine as the CL.IIIa reverting to the Argus engine.

Dr Hildebrandt noted that

"Hawa deserved credit for the quick and successful jump into the difficult task of original design. This did not go without failures. These were mainly due to the engines which were directed to the factories by the Fugzeugmeisterei. In spite of all the efforts during the entire war, the engine industry was never able to completely fill the needs of the front. It had a severely hindering influence that we had too few effective factories and, of course, because of the sever lack of the best engines, these always first went to manufacturers which had produced the best aeroplanes and could show the best results. Hawa initially had to show proof of its competence and until then it received engines of secondary quality. Then came the great success: The “Black Hannoveraner.’’"

Hannover built an experimental high-altitude reconnaissance prototype as their C.IV but it was not successful. It was followed by the CL.V, the final Hannover warplane, an improvement over the earlier CL models. The CL.V would have been produced in quantity had the war continued. Under the designation F.F.5 Hauk, the CL.V was to be manufactured post-war in Norway.

Company documents show the aircraft as the Hawa F 3, etc., however it has become standard to refer to them as Hannovers, and this nomenclature is used in this volume.

Idflieg specified the Argus As.III engine as the powerplant of the new aircraft as these were available in reasonable numbers, whereas the 160-hp Mercedes D.III was at times in short supply. The British reports on Captured Hawa aircraft usually refer to the engine as an Opel. This was because the As.III engine was built by Deutz, Guldner and Becker in Switzland, MAN, and Opel under license. The Opel built As.III engines were of higher quality than those of Argus itself and Dorner would have a supply of As.III(O) for his design. Idflieg having ordered large numbers of the As.III before the engine had been thoroughly tested, now needed to use these engines, and although the Argus engine fell off in performance at higher altitudes, this was not considered a liability given the altitudes that the CL class would operate at; also the engine was readily available in some numbers. Apart from the engine the designer had a free hand.

The Hanover C.II was Dorner's first design for Hawa. Idflieg were impressed with the aircraft and ordered three improved C.II machines in April. (The CL designation not becoming into general use until late in 1917.) These prototypes were: - one for flight testing, one for static load testing and one as a spare (CL.4500 to 4502/17). The machine passed its Typenprufung (Type testing) on 21 July 1917, and Hawa was rewarded with an order for 200 machines that same month (CL.9200 to 9399/17). Further orders for an additional 240 aircraft were given later in the year (CL.13080 to 13199/17 and CL.13263 to 13382/17). LFG Roland received an order for 500 CL.II (Rol) advanced trainers in 1918. For a company new to aircraft construction this was significant coup.

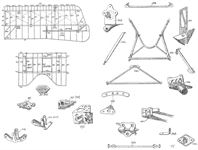

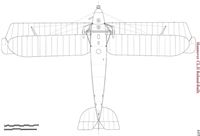

The prototype's tailplane had a rectangular shape in plan view, whilst that on the production machines was given a rounded leading edge. According to the late Dan San Abbott the production machines differed slightly in dimensions from the prototype. The lower wing span was reduced from 12.000 to 11.170 m; the height was increased from 2.750 to 2.860 m. The upper wing and fuselage dimensions remained the same. Empty weight rose from 773 to 775 kg, which gave a useful load of 380 from 360 kg.2

The CL.II underwent modifications during its production run, the most obvious being the replacement of original ailerons with an enlarged version that became standard for all Hannovers. The ailerons were extended past the wingtip profile for better aerodynamic balance. The slim full gap strut that supported the tailplane was dispensed with on later model CL.II machines.

The Hannover CL.II, along with the Halberstadt CL.II, were the types to equip the new Schutzstaffeln (Escort Squadrons). These were to operate with the infantry giving close air support. The ability of the monocoque construction to absorb damage led Allied pilots to believe that the biplanes were armoured. The Hannovers were not armoured and relied on their speed and nimbleness to operate down with the frontline attacking troops. On 27 March 1918, the units were renamed Schlachtstaffeln (Battle Flights) in acknowledgement of their frontline task.

Rather than attacking en-mass, the Germans developed new attack tactics. Shock troops would move forward through the line of least resistance leaving strong points to be attended to later. During the attack the Schlachtstaffeln aircraft would attack enemy strong points, harass the enemy's rear areas to stop reinforcements reaching the battlefield.

The Hannovers also served with the Flieger Abteilungen (Aircraft Sections) where their speed and manoeuvrability enabled them to performed short-range reconnaissance and artillery spotting duties. So successful was the type that a new version was designed around the high altitude 160-hp Mercedes IIIa that emerged as the CL.III.

During May-June 1918, the CL.II was grounded due to a number of wing failures. Idflieg ordered the strengthening of wind fittings of aircraft on the production line. The wing fittings had a factor of safety of 4.5 and this was increased to 10. As a result, the majority of CL.II biplanes were withdrawn from the front and assigned to training units. LFG Roland received an order for 200 CL.II (Rol) (500-699/18) as trainers due to the needs of the Amerikaprogramm of 1918.

Hanns-Gerd Rabe wrote that the

"machines that we flew from the Hawa in 1918 were reinforced and no longer had fluttering or vibrations in the wings; you could do aerobatics well with them, they were very firm in a steep turn, which you could turn very tightly, so that the English fighter pilots; the Sopwith Camel and the SE 5, could not fly these tight turns as they slide into the bend, while the Hawa did not lose height."

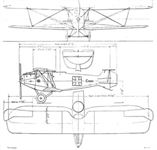

The Hannover CL.II described.

The CL.II had a deep fuselage almost filling the gap between the wings. This led to early reports by Allied pilots who thought that the upper wing was mated to the fuselage in the same fashion as the Roland C.II of previous years. The fuselage was constructed around four longerons with ten light formers. The skin was 1.6 mm birch ply and this was covered with doped fabric to give a waterproof surface. Aluminium cowlings around the engine completed the clean streamlines of the machine. Dorner reduced resistance and weight wherever he could by careful design. Metal fittings were kept to a minimum.

The pilot had a single fixed synchronised Maximum LMG 08/15 machine gun, and the observer/gunner had a Parabellum LMG 14 on a circular wooden turret in the rear cockpit. The pilot sat over the 140-litre fuel tank with his eyes on a level with the top plane. He could either above or below it by a slight movement of his head. His downward view was good due to the narrow chord of the lower planes. The deep fuselage protected the crew from the elements, while the unique double tailplane layout gave the gunner a much better field of fire than conventional two-seaters.

The wings, with milled leading edges and wing tips, were constructed around two hollow built-up spars. The upper wing had a metal strap trailing edge while that of the lower wing was wire. The centre section had a ply covering the same as the fuselage. A gravity tank of 40 litres capacity was located on the port side with the aerofoil type radiator was located on the starboard side of the centre section. The wing panels were swept back 1.5°. Upper and lower panels were easily detachable from the centre section enabling them to be replaced quickly in service. The spars terminated in a steel box structure with a quick-release joint.

With the second batch of CL.II fighters (CL.113075-13374/17) a number of small modifications were introduced. The most visible was the change to the ailerons that had the balance area increased. These ailerons would become standard for the following CL.Ill and CL.IIIa. A single light strut was added to the upper and lower tailplane. These struts were fitted to CL.II machines in service at the Front.

Allied Reports and Comments on the Hannover CL.II Series of Biplanes

The following details of the Hannover biplanes are taken from the contemporary reports. What is most interesting is the different details that caught the attention of the various writers of these reports.

Hannover CL.II 13130/17

The Report on "Enemy Aviation for the Month of August, 1918" contained the following notes on Hannover CL.II 13130/17 that was captured by the French in good condition and was to be tested, however these tests were delayed when the French airscrew had to be replaced as it did not allow the engine to reach its correct power.

The machine was tested and a chart of its performance issued by the French on 23.09.1918. L’Aerophile published a long, illustrated and descriptive article on this machine in its issue of 1-15 October 1918, complete with detailed three-view drawings.

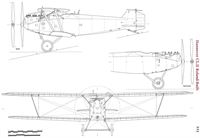

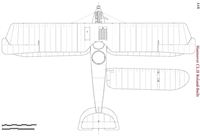

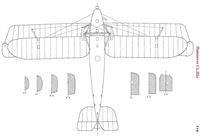

Hannover C.13199/17, British serial G.156

Hannover CL.II 13199/17 was brought down near Lestren by AA fire on 29 March 1918.

Given the British serial G.156 this machine was flown to the UK on 26 April 1918. No details of whether a new engine was fitted to the machine has been found to date.

Three reports on Hannover CL.II serial 13199/17 survive. One "in the field" report, presumably prepared before the machine was flown to England on 26 April 1918. The second was the report prepared by Martlesham Heath after trying the machine in the air. The third was issued by the Ministry of Munitions in July 1918, and contained many detailed drawings of the machine. The compilers of each of these reports found many of the same features worth reporting.

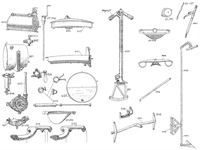

The "in the field" British report on 13199/17 was dated 1 April 19187 No G number was appended to the report. The report states that the engine, Opel Flugmeter 1218, was wrecked. "Hannoversche Waggon Fabraik, A.G. Abtflugzeugbau" was marked on the wings. There was a rigging diagram pasted on the side of the fuselage headed "Han C.L.II." The angle of incidence marked on the diagram and on the fabric of the wings was:

Lower wing 5 1/2° at fuselage,

5° at struts.

Upper wing 5° whole length.

The dimensions stated in the report are shown in the accompanying table. The difference between these and those taken at Martlesham Heath should be noted.

The gunner's cockpit was very roomy. A drop-down flap seat was provided for the gunner. The floor was sufficiently high to enable a camera there. And a hole was provided in the bottom of the fuselage covered by a sliding panel operated by wires and pulleys, and a loose panel in the floor boards covered the camera position. Controls were not duplicated except that the air pump plunger extends upward and backward to enable the observer to reach it. The observer could reach the joy stick if necessary. Leads and push-in sockets were in place, "apparently for electrically heated clothing and gun, for the observer only. The Spandau gun receives sufficient heat by being places to leeward of the exhaust manifold."

The pilot's cockpit was also roomy and easily entered. "All the usual instruments and controls are installed, at the same time leaving very ample dashboard area for maps." The top plane was about 12" above the fuselage and the "machine is good to see from."

The lower wings had a wire trailing edge. The rear edge of the upper wings consisted of a metal strip.

The ailerons were controlled by a cantilever instead of king posts, the operating wire being led from the forward arm of the cantilever and the back edge of the aileron directly down to pulleys in the lower plane behind the front spar, and thence led inside the lane to the control gear in the fuselage.

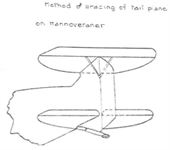

The empennage had double surfaces "apparently designed to mitigate the masking effect on tail controls of the large bulk of the fuselage."

The tail-skid was sprung by elastic cord wrapped around its front end and through a hole in the triangular under fin of the fuselage. The tail-skid was not provided with a swivel mounting but had a solid metal shoe of "good dimensions" allowing the skid to side-slip in answer to the rudder when taxying. The Martlesham Heath report on Hannoveranische (sic) G.1568 contained the following comments:

It was noted that the pilot was seated with his eyes level with top plane, about one foot in front of the trailing edge of the wing. The "passenger" was seated immediately behind the pilot. The pilot had stick and rudder bar controls while the passenger had none. There was a circular hole in the floor of the passenger's cockpit closed by a sliding screen that was opened by a cord. It was thought that this was used for aerial photography.

The tailplane was fixed.

The machine was not intended for night flying.

A two-bladed Resche airscrew, marked 21930, 180 RS. Argus. D.285; St.155, was fitted.

The radiator carried 514 gallons water.

There were three fuel tanks:

Gravity tank in top plane of 714 gallons. Pressure tank under pilot's seat of 30 gallons. Pumped tank at side of engine of 3 gallons.

Starting was by means of a hand starting magneto and was described as "easy" with an average time to get away of 10 to 15 minutes.

The maximum height reached was 14,400 feet in 39 min 10 sec, the rate of climb being 120 feet per minute.

The machine was found to be nose heavy with engine off and slightly tail heavy with the engine on, and also had a tendency to turn to the right with the engine on.

Generally light on the controls except that the elevator seemed "rather insufficient at slow speeds; she is not tiring to fly and pulls up very quickly on landing."

The view for the pilot and observer was considered "particularly good" - the lower planes having a narrower chord than the upper and this added considerably to the downward view.

General Details

The fuselage was of plywood with the fin being built integral with the body of the machine.

A biplane tail of very short span was fitted.

Only the ailerons were balanced.

There being only one pair of interplane strut on each side in spite of the wide span, it was felt that "in consequence, the lift wires are set at a poor angle."

"A detail well worth noting" was the provision of spring hinged flaps over the control wire pulleys. This was considered a much better idea than sliding doors that require locking and would encourage more frequent inspections.

The engine was controlled from the joy stick that has an inverted Vee-shaped grip. The left leg of the Vee was the throttle lever and rotated around the joy stick axis. There was also an emergency throttle lever on the dashboard.

All engine controls were conveniently placed and easily worked.

The rudder bar was fitted with welded steel loops for the heels instead of the usual stirrups for the toes. This was not considered as good as the stirrups.

The engine ran very smoothly and throttled down well. It accelerated up very quickly.

The position of the pilot and observer enabled easy communication between the two.

Under "Armament" the pilot's synchronised gun on the starboard side was mounted on brackets supported by the longerons, and this was criticised as being not very rigid.

The ammunition box was of three-ply wood and held about 700 rounds. The usual leaf backsight and 1 1/2'' diameter ring foresight were fitted.

The observer's gun was apparently not fitted as the report states that it was "Probably Parabellum". The gun was mounted on a rotating ring mount of metal covered with wood. The mounting could be easily worked, but he locking and unlocking involved the use of three levers as against one for the Scarff mount. This gun had a good field of fire.

The report was signed by Capt D.R. Pye for the Aircraft Experimental Officer, Aeroplane Experimental station, Martlesham Heath, 27 May 1918.

The Question of Sweepback

Did the CL.II have sweepback? This question arose because of conflicting data available from reputable contemporary sources.

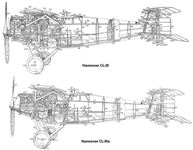

The BB drawing for the CL.II prototype and those of the CL.III show sweepback of 1.5°. (Sketch 02 & 03).

The drawings of the CL.II 13130/17 by Jean Largoragette in the l’Aerophile issue of 1-15 October 1918, show no sweepback.

The drawings of the CL.II that the British included in the Ministry of Munitions report on CL.II 13199/18 (G.156) and reprinted in Flight and The Aeroplane show no sweepback. (Sketch 04).

The German identification chart for the CL.II shows the sweepback. (Sketch 06).

Hawa booklet showing F 3 with sweepback. (Sketch 09)

Idflieg drawing of CL.III 16000/17 shows the sweepback. (Sketch 05).

The drawings in the Hannover CL.III parts manual show wings without sweepback. (See Appendix 1). The later manual for the CL.V had photographs of the parts rather than drawings. The draughtsman may have made a mistake or worked from early drawings.

Bearing in mind that the sweepback was small, and that the French drawings were made from measuring a fully erected and covered machine, this feature could have been overlooked.

The artist who prepared the German recognition manual made a point of emphasizing the aircraft's main characteristics. In the case of the Hannover CL.II he has shown the sweep-back on the plan views. (See recognition sheet).

When researching the CL.II for their plastic kit, Wingnut Wings Ltd came to the conclusion that there was good evidence that both straight and swept-back upper wings were used with swept-back wings being more common. Nothing has come to light since the kit's release to change this view. The authors accept that the recognition chart would not show sweepback unless it was on production aircraft and the drawings have been drafted incorporating sweepback.

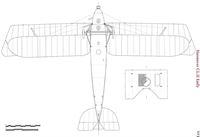

Hannover CL.III & CL.IIIa

At the end of their detailed examination of the CL.II, the 1-15 October 1918, issue of the French journal l’Aerophile noted that the CL.III of more recent manufacture, had retained the general characteristics of the type CL.II as described in l’Aerophile, and differed only by some slight modifications of detail made in its construction. In particular the removal of the struts in the tail. These organs were replaced by small flattened tubes from the fixed fin, at the height of the back of the fuselage, to end of the upper stabilizer plane. In running order, the weight of this aircraft was slightly higher than that of the Hannoveraner (sic) CL.II

The Hannover CL.III (Type 3b) had a lightened but strengthened airframe, the overall size being slightly reduced, but it was virtually indistinguishable from the late model CL.II. The aircraft had demonstrated "very favourable results but owing to the Mercedes engine shortage was not expected to figure in series production." Passing its Typenprufung on 23 February 1918, 200 aircraft were ordered with deliveries commencing in March. Due to the priority of the Mercedes engine being given to single-seat fighters, only 80 CL.III biplanes were constructed during the war. The remaining 120 machines were completed as CL.IIIa types that were identical to the CL.III except that they had the Argus As.III(O) engine. Despite this, official Idflieg documents show CL.IIIa biplanes with Mercedes engines. The CL.IIIa saw the greatest quantity production of all the Hannover types.

The CL.III and CL.IIIa went into squadron service in March-April of 1918. They were easy to fly, possessed a good performance and were capable of putting up a good defence. They were praised for their good landing and take-off capabilities when using the makeshift airfields at the Front.

Differences between the CL.II and the CL.III were the decrease in the length of the fuselage, the CL.III being 0.580 m shorter and the centre-section span was 2.400 m while that of the CL.II was 2.660 m. The CL.II and CL.IIIa could be identified from the CL.III due to the As.III(O) engine. This engine had valve springs and push rods and the cylinders were in pairs. The radiator water pipe had three pipes that turned down from the main pipe to each of the paired cylinders. The CL.III had the Mercedes D.IIIa and the water pipe ran from the front of the front cylinder to the radiator.

The CL.III appears to have the same fuselage as the CL.II with modifications at the front and rear ends to accommodate the Mercedes engine. When the Argus had to be used instead of the Mercedes, the nose of the CL.IIIa appears to have been lengthened and given that the CL.II accommodated the engine, the dimensions were most probably the same. The detailed description given for the CL.II also covers the CL.IIIa.

Hannover CL.IIIa 16196/17, captured at Saponay, (Aisne), by the French and had the following inscription on the fuselage:

Leegewicht mit Wasser und Gehaiiseol 760 kgs

(Weight, empty with water and oil 1,680 lbs)

Nutz.ast ohne Betriebstoff 360 kgs

(Useful weight without fuel 795 lbs)

The report commented that the last figure appeared to be high and the first figure too low. It noted that the type has evidently been altered as regards the struts and bracing wires of the tailplane, which have been replaced by two diagonal steel bracing struts running from the lower surface of the upper tailplane to the stern post of the fin. The observer could fire with less chance of damage to the structure. A rough bomb rack was situated in front of the observer's cockpit for four x 25-klb bombs that could be dropped by hand through the trapdoor in the cockpit. A small figure accompanying the report showed the tail struts supporting the upper horizontal stabiliser. (See sketch).

The Hannover CL.IIIc was an increased span twin-bay version of the CL.Ill built at Idflieg’s request to test the new 190-hp NAG C.III engine. German records show a CL.IIIb was powered by the NAG engine but do not indicate whether it was a two or single bay machine. It was apparently flown in early summer of 1918. No data are available on this version of the Hannover biplane.

The Hannover in Combat

The first Hannover CL.II machines to reach the front were delivered to the Flieger-Abteilungen, the German reconnaissance squadrons. No unit appears to have only operated Hannovers, and the later CL.III and CL.IIIa were also distributed piecemeal throughout the Front.

While serving as an observer with Fl Abt (A) 209, Ltn Gunther Wolff flew missions on Hannover CL.II 9252/17 from 15 December 1917 until 12 January 1918. During this period, he made nine flights, mainly evening reconnaissance flights and directing artillery fire. On 23 December he was attacked by three Spad fighters from out of the sun. "They left when they got machine gun fire from me." The upper right elevator was broken by two hits of the enemy's white tracer ammunition. During this period clouds and hazy weather often led to the missions being abandoned or incomplete. The Hannover flew at 3,800 metres altitude for the reconnaissance missions and at 1,800 - 2,000 metres altitude when directing artillery fire. On occasions they would venture down to 700 or 400 metres when attacking enemy trenches with machine gun fire or dropping 12.5-kg bombs. Most times he recorded that it was quiet at the Front with little air activity except for captive balloons. One additional mission during this period was carried out on 3 January in a Rumpler. Vzfw Borestell was his pilot for all these missions.

From 22 to 29 January 1918, he flew three missions in CL.II 9226/17 with Ltn Hennen as pilot. On his last Hanover mission, he recorded that they had exposed 30 plates while photographing their own rear area: Froidemont - Grandlup - Monceau Le West. None were useable due to severe haze. From 11 February he mainly flew missions in Rumpler C.IV and C.VII biplanes with the odd flight in DFW C.V, LVG C.VI and Halberstadt C.V biplanes. It was a crash on 23 August in Halberstadt C.V 3405/18 that lost a wheel on landing and flipped over onto its back that ended Wolff's flying career.

The formation of the Schutzstaffeln (Shusta - Protection Flights) saw the qualities of the Hannovers well suited to their duties where they operated alongside the Halberstadt CL.II and CL.IV. These flights had the same composition as the Reconnaissance Flights, a nominal strength of six but actual strength of about four aircraft. They were intended in the first place for defence duties and were to protect the divisional Reconnaissance Flights against hostile aircraft and form a constant escort for the artillery aeroplanes. In direct opposition to their original function, the Protection Flights were detailed to carry out offensive action in the air and ground straffing "when not employed on the protection of artillery aeroplanes." However, this latter duty kept the Protection Flights fully occupied and they were hardly ever available for their original duties.

In March 1918 the flights were renamed Schlachtstaffeln (Schlasta - Battle Flights) as their duties had come to embrace low level attack flights against Allied troops and artillery, especially in supporting attacks by the German infantry. They were to attack in waves the enemy trenches, artillery and machine gun emplacements, enemy reserves, musterings of troops and particularly to oppose shock attacks or retreating movement of the enemy. Objectives further behind the front, such as transport, also came within the function of these Battle Flights. The attacks were carried out in principle, by means of heavy machine gun fire, small calibre bombs and hand grenades.

Battle Flights were sometimes sent out in formation to convoy individual reconnaissance machines which were required to break through a strong enemy fighter screen, or even in close formation on special reconnaissance duty.

The rule was to allot complete squadrons or groups (4 to 5 Flights under a commander or leader) to the Army Commands as part of the Army strength. The Army Commands were at liberty to place the Battle Squadrons at the temporary disposal of an Army Corps Command at centres of attack. They formed, in a certain measure, a last flying reserve of extraordinarily high firing power in the hands of the Command.

Hanns-Gerd Rabe of Flieger Abteilung (A) 253 wrote that he had

"received the first airplane that is really my own. It is a two-seat fighter, a Hawa CL.IIIa type. It is a small, well-built, single-bay biplane that is very maneuvrable, climbs rapidly, and has excellent stability in a turn during serial combat; due to the high, narrow fuselage design, it loses hardly any altitude in a tight turn. The Hawa has a peculiar double elevator arrangement that makes possible a very tight turning radius. The airplane is so small that if I lean out of my cockpit, I can easily touch the tail section. The Hawa is especially suited for medium-range reconnaissance penetration of 30 kilometres being enemy lines and to direct artillery fire."

This aircraft was CL.IIIa 2714/18 that Rabe had marked with the emblem of the pre-war German youth club that he was a member of. It is a Wandervogel (a migratory bird). In another letter he noted that

"our infantrymen are happy when I strafe the British trenches from my “Hawa” machine. When one has served for as long as an infantryman in the filth of the trenches, as I have, then when one becomes a flyer he wants to help out the poor comrades on the ground, in spite of the inherent fear."

Rabe gives the following account of an early morning attack on 4 July 1918, on the British trenches. Taking off in the dark he would zoom down over the British hinterland undisturbed. Gliding along he would observe the British positions at low altitude and nearly always fool the British into thinking it was one of their own aircraft.

During the return flight, as it was becoming light, I made a low-level hedge-hopping attack on (the) British trenches, using machine gun fire, hand grenades and small tear gas bombs. With my machine gun I chased the sentries into their dug-outs and even fired into the entrances of these shelters. During this flight this flight I discovered three large shell holes all connected by a subterranean explosion. In these holes were several British soldiers who, during the night, had been placed there as forward observers. Now, in the light of day, they were unable to return to their own lines because they would have to climb over the high rim of the shell crater, in which case they would have drawn fire from our infantry. We went down after them and I chased them from one shell hole to another, firing at them and throwing hand grenades into the craters. A very cruel game that knew no merch and ended when the Englishmen no longer moved... dark dead bodies lying on the dirty, chalky soil."

When discussing the qualities of the Halberstadt and the Hannover CL type, Rabe stated that "each machine had its advantages and disadvantages." Personally, he found the "Halberstadter" was too narrow and was therefore not of use as an observation machine, and "was also, as far as I know, never used as such. I flew it a few times in the early days, in the semi-darkness, as an Ifl-machine, whereby the front was hardly over-flown. It was first and foremost used as a "battle plane" (triple or fivefold) and for artillery aviators when shooting in heavy batteries, but I decided not to do so because I was better off with the Rumpler C.IV or C VII".

"In contrast, the Hawa was a good observer machine, very spacious inside for camera, radio, oxygen, etc., and excellently suited for flying to 30 km into the enemy’s airspace. For long-distance reconnaissance, she did not fly high enough; did not reach more than 5000 m altitude. But she was very agile in air combat (my personal experience!) Good view for the observer on all sides, good job opportunities with all equipment. As a result of the high fuselage she did not easily fall down when performing a steep turn, she kept nearly the same height. My pilot liked to fly her, dearer than the “Ru C IV”, which was hard to keep in the turn. My long-distance reconnaissance I have almost exclusively flown with the “Ru C VII”, best altitude machine of that time, it is not reached by any enemy Jagdeinsitzer. With the Hawa I never had any technical faults or a crash landing, with her I also felt very safe in a dogfight, because the pilot could put her hard in a steep turn."

Rabe wrote that the Hannover was only at risk when it was caught in level flight.

As noted above, the Allies had trouble with the establishing what the identity of the biplane tailed two-seater was, and it was therefore of interest to James McCudden, the pre-eminent destroyer of German two-seaters. He had his first and a close view of the new Hannover two-seater on 6 December 1917.

"I engaged a two-seater over Bourlon Wood and drove it down damaged. This machine had a biplane tail, and is now known as the Hannover. I mention this because the description of this new machine first appeared in February, 1918, about three months after I first encountered it?"

McCudden logged it as a Roland, while No. 56 Squadron reported the type as a new Albatros fighter.

On 4 January 1918,

"I went down to engage him, and found that he was a “Hannover,” a machine which has a biplane tail, and although I fired a lot at him at close range, it had no effect other than to make him dive away, which made me think that perhaps they were armoured.

These machines are very deceptive, and pilots are apt to mistake them for Albatros scouts until they get to close range, when up pops the Hun gunner from inside his office, and makes rude noises at them with a thing that he pokes at them and spits flame and smoke and little bits of metal which hurt like anything if they hit them.

I had seen a lot of these Hannovers lately, usually escorting an Artillery D.F.W. or L. V.G. near the lines, and I very much wanted to bring one down."

On the 9th he again attacked a Hannover that was escorting a two-seater over Bourlon Wood at 12,000 feet. Because his Aldis sight was inoperable due to moisture, McCudden had to aim by tracer and he put a burst into the machine at a distance of about 50 yards. The enemy machine was last seen leaking water or petrol when it disappeared at 500 feet. It was not claimed as a victory.

His luck remained the same on the 25th when he put 100 rounds into another Hannover without apparent effect. On the 28th he flew his S.E.5a B4891, that he had modified with high-compression cylinders and a weight reduction that saw the headrest removed and the exhaust pipes shortened. Again, a Hannover proved resistant to his fire.

On 3 February he was up alone when he

"very soon met one of the Hannovers which have the biplane tail. I engaged this machine for a while, and at last drove him down east of Marquion with steam pouring from his damaged radiator, but he was under control."

Finally, on 26 February he saw a DFW being escorted by a Hannover.

"As soon as I had arrived, the D.F.W. ran over the enemy lines, and the Hannover came to attack me, but then turned away to follow the D.F.W.

As I looked at the machine I saw the enemy gunner fall away from the Hannover fuselage. I had no feeling for him for I knew he was dead, for I had fired three hundred rounds of ammunition at the Hannover at very close range, and I must have got 90per cent, hits."

This Hannover was an aircraft of Fl Abt 7 and flown by Vzfw Otto Kresse and Ltn Rudolph Binting. This was to be McCudden's only recorded confirmed victory over a Hannover.

Eddie Rickenbacker recalled that the 94th Aero Squadron was given a new task at the beginning of October 1918 against the German CL machines that "came over our lines. Usually they were protected by fighting machines. Rarely did they attempt to penetrate to any considerable distance back of No Man's Land. They came over to follow the lines and see what we were doing on our front, leaving to their high-flying photographic machines the inspection of our rear." On 2 October Reed Chambers led the first patrol under these new orders and Rickenbacker went along as a volunteer. Chambers had five machines with him and Rickenbacker followed at a somewhat higher level some 2,000 feet or more above them in order to give the patrol some extra protection.

"We had turned back towards the west at the end of one beat and were near the turning point when I observed a two-seater Hanover machine of the enemy trying to steal across our lines behind us. He was quite low and was already across the front when I first discovered him.

In order to tempt him a little further from his lines I made no sign of noticing him but throttled to my lowest speed and continued straight ahead with some climb. The pilots in Chambers’ formation were below me and had evidently not seen the intruder at all.

Calculating the positions of our two machines, as we drew away from each other, I decided I could now cut off the Hanover before he reached his lines, even if he saw me the moment I turned. Accordingly I turned back, aiming at a point just behind our front, where, I estimated our meeting must take place. To my surprise, however, the enemy machine did not race for home but continued ahead on his mission. Was this brazenness, good tactics mixed with abundant self-confidence, or hadn’t the pilot and observer seen me up up above them. I wondered what manner of aviators I had to deal with, as I turned after them and the distance between us narrowed.

A victory seemed so easy that I feared some deep strategy lay behind it all. Closer and closer I stole up in their rear, yet the observer did not even look about him to see if his rear was safe. At one hundred yards I fixed my sights upon the slothful observer in his rear cockpit and prepared to fire. He had but one gun mounted upon a tournelle and this gun was not even pointing in my direction. After my first burst he would swing it around, I conjectured, and I would be compelled to come in through his stream of bullets. Well I had two guns to his one and he would have to face double the amount of bullets from my Spad. Now I was at fifty yards and could not miss. Taking deliberate aim I pressed both triggers. The observer fell limply over the side of his cockpit without firing a shot. My speed carried me swiftly over the Hanover, which had begun to bank over and turn for home as my first shots entered its fuselage."

Gaining a position again at the rear of the Hannover, Rickenbacker fired but both is guns had jammed. Realising that the enemy pilot would not know this fact, he came up and forced the German to make a turn east to avoid what would have been a fatal position had Rickenbacker's guns been working. Now Chambers and his patrol came in on the fight, Chambers' first burst hit the pilot and the machine

"settled with a gradual glide down among the shell holes that covered the ground just north of Monfaucon - a good two miles within our lines.

It was the first machine I had brought down behind our lines - or assisted to bring down, for Reed Chambers shared this victory with me - in such condition that we were able to fly it again."

Unfortunately this encounter, while it did occur, did not involve a Hannover but a Halberstadt CL.II. According to Rick Duiven's research, 3892/18 was not the aircraft brought down by Rickenbacker and Chambers. They had brought down a two-seater but it was a Halberstadt CL.II of Schlasta 20, and the pilot, Uffz Rudolf Hager, was killed, not the gunner, Uffz Otto Weber, who survived. The Hannover was mistaken for that shot down by the 94th Aero Squadron.

On 5 October Rickenbacker learned that a Hannover was under guard and in good condition. "I might say in passing" wrote Rickenbacker's ghost writer "that it is extremely rare to find an enemy machine within our lines that has not been cut to pieces for souvenirs by the thousand and one passers-by before it has been on the ground a single hour." As soon as they knew that the German machine was in care they immediately set out in an automobile for the machine's site, a mile or so north of Montfaucon. The machine was Hannover CL.IIIa 3892/18 of Schlasta 20 and bore a large white arrow on the fuselage sides. Rickenbacker noted that this was the first Hanover captured by the US forces and the pilots were always anxious to try a German machine to see how it compared with theirs and to see what improvements the Germans had made.

"The German Hanover machine we found just beyond the town. It was indeed in remarkable good condition. It had glided down under the control of the pilot and had made a fairly good landing considering the rough nature of the ground. The nose had gone over at the last moment and the machine had struck its propeller on the ground breaking it. The tail stood erect, resting against the upper half of a German telegraph pole. A few ribs in the wings were broken, but these could, easily be repaired. Our mechanics with their truck and trailer had already arrived at the spot and were ready to take down the wings and load our prize onto their conveyance."

The machine was taken back to the squadron and put back into flying condition. The German markings were left unchanged with the 94th Aero Squadrons "hat in the ring" insignia added to the port side. The surrounding squadrons told not to use the Hannover for target practice if they came across it as the squadron was now going to take it back into the air. Rickenbacker noted that the

"Hanover was a stanch heavy craft and had a speed of about one hundred miles an hour when two men (a pilot and an observer) were carried. She handled well and was able to slow down to a very comfortable speed at landing. Many of us took her up for a short flip and landed again without accident.

Then it became a popular custom to let some pilots get aloft in her and as he began to clear the ground half a dozen of us in Spads would rise after him and practice diving down as if in an attack. The Hanover pilot would twist and turn and endeavour to do his best to outmaneuver the encircling Spads. Of course, the lighter fighting machines always had the better of these mock battles, but the experience was good for all of us, both in estimating the extent of the maneuverability of the enemy two-seaters and in testing of our relative speeds and climbs."

The story of 3892/18 does not end here as it was the subject of a movie. On 21 October Reed Chambers, with Thorn Taylor in the rear cockpit, took the Hannover up while Rickenbacker took his "old Spad No. 1" up to engage the enemy for the Liberty DH-4 camera plane. The two machines fired real ammunition but aimed to miss each other. The action took them close to a French aerodrome and its interest was indicated by bursting anti-aircraft shells. Chambers immediately dived to land on the French aerodrome with Rickenbacker following acting that he "had the affair well in hand and the Hanover was coming down to surrender." The French laughed when the situation was explained to them. Everyone thought it was a great joke except the crew of the Hannover who "from the expression on their faces seemed to feel that the joke was on them."

According to Rickenbacker 3892/18 was sent to Orly Field for shipment back to the USA for display. The Hannover and Fokker D.VII 4635/18 (U.10) were flown in company a few days after the Armistice to Orly Field. Maj Harold Hartney flew the Hannover and Lt E Curtiss the Fokker. As both machines were still in full German markings, they were accompanied by an escort of a Spad and two Sopwith Camels. The machines were crated here and sent to the USA. The Fokker ending up in the Smithsonian NASM collection.

Hannover Postwar

One hundred CL.III, 38 CL.IIIa, 57 CL.V and 5 "CL.V M" aircraft were completed after November 1918. Hawa looked to perusing civil aircraft construction after the end of the war and on 28 May 1919, purchased some of its aircraft back from the German government. The British journal The Aeroplane reported on 13 August 1919, that Hannover were producing aircraft. On 20 August the journal noted that company was to start a regular air service to the Harz. In the "Aeronautical Engineering" supplement to the journal, an article titled "German Commercial After-war Aircraft" showed a sketch of the CL.IIIa with enclosed rear cockpit with the title "Hannover CL V". In comparing the British and German progress it noted that various German manufacturers had "adopted the Airco two-passenger limousine fashion fuselage for their modern light two-seater (C.L. class) biplanes, by raising the rear observer's cockpit."

A CL.III with the 180-hp Argus engine was fitted with an enclosed cabin to hold two passengers in the gunner's position under the designation F3e, received the civil registration D.81 on the first German postwar civil register.

<...>

The company began to manufacture automobiles and trucks in 1919 and by 1920 a major expansion of its factory was underway.

The end of the war did not see the end of the Hannovers flying for the German Army. They were used by the units supporting the Freikorps in the Baltic region along with other modern German aircraft such as the Junkers all metal fighters.

The Lists ser Luftfahrzeiuge und Motor en Nach Typen, listed all aircraft in Germany's possession at 10 April 1920, according to the German authorities. The original was copied in the Musee del’Air by the late P.M. Grosz. The following Hannover biplanes were listed under the following categories: 1. are sometimes installed in the aeroplanes. 2. With engine.

The Polizei-Fliegerstaffeln (Air Police Squadrons) also operated a variety of military aircraft including two Hannover CL.II, ten CL.IIIa and eight CL.V biplanes in January 1920. The Air Police at Stettin had CL.V 9632/18 together with a Fokker D.VII and a Junkers CL.I in its inventory. CL.IIa (Rol) CL.539/18 was reportedly operated by the Polizei-Fliegerstaffeln at Schwerin after the Armistice.

Hanover CL.I (sic) 9693/18 was reportedly destroyed by the RTG on 1 February 1922, along with two Fokker D.VII biplanes, 3587/18 and 2147/18; a Rumpler C.IV and a Siemens-Schuckert D type.

According to the IAACC, Hannover sold a GL.V, two CL.V and three CL.III biplanes between the Armistice and the signing of the Peace Treaty. It is assumed that the GL designation is a clerical error.

Foreign Hannovers

Australia received CL.II 13199/17 (G.156) in 1921. It is assumed to have been destroyed by fire in 1925. Belgium received three CL.III machines that in March 1919 were with the 7° Groupement at Evere. On 5 March 1920, these were reported as in an unassembled state. Another Hannover was delivered in 1920, probably a CL.IIIa.

Canada received CL.IIIa 12678/18

France:

Amongst the German aircraft captured by the French during the war were the following Hannovers:

CL.II 13130/17 was captured in August or September 1918, and restored to flight status with French camouflage applied. Two other Hannovers were taken by the French: - CL.IIIa 2747/18 and 13369/17. The latter machine was captured on 6 September 1918, and carried the white arrow insignia of Schlasta 20 on the fuselage.

United Kingdom The British captured the following Hannover aircraft and gave them "G" serial numbers.

Hannover aircraft dispatched to 2 Salvage Section, RAF, at Fienvillers post-Armistice: -

Han C.I 3168 (probably a misidentification), and Han CL.III/IIIA 1336/17, 13350/17, 13350/17, 13359/17, 2670/18, 2679/18, 2686/18, 2707/18, 2743/18, 3801/18. 3808/18, 3825/18, 3864/18 3869/18, 3874/18.

The RAF wanted to obtain three flyable German machines of selected types, nearly all the front-line types operated by the Germans in 1918. However, on 10 February 1919, the RFA Technical Department was informed three of the following had each been collected and arrangements were being made to ship them to Martlesham Heath: Fokker, LVG, Halberstadt, Gotha, AEG, Pfalz D.XII, Albatros, Friedrichshafen and Aviatik.

They were also told that it was "not possible to supply 3 serviceable" Hannoveraner, DFW, Friedrichshafen, Roland and Junker machines that were requested. Given the short time since the Armistice and the handing over of German aeroplanes, the original request would seem to have been reasonable and one can only wonder why the Hannovers were not obtainable.

Italy

Italy selected three Hannovers, CL.IIIa 3886/18 and 3891/18, as well as a CL.V, amongst some 131 aeroplanes that were delivered as war reparations. They were to be delivered in June and July 1920, however the April 1921 list of aircraft actually delivered shows only one Hannover.

Latvia

Hannover CL.IIIa 7015/18 was obtained by Latvia in 1919. Some aircraft were purchased and some were obtained by the Latvian government from retreating German units in 1919-1920. The Hannover received the Latvian serial 21. This machine was assigned to the Latgale front on reconnaissance duties in April 1920. It suffered a forced landing enroute and was damaged. It was back in the air by at least 21 June when it carried an officer of the British Naval Mission from Riga to Reval and back. On 25 July it took part in the 1st Aviation Festival in Riga, promoting the show by dropping leaflets over the town and by carrying fare paying passengers to raise money for the families of pilots killed in service. Serial 21 suffered another force landing on 10 June 1921 when the engine caught fire. In 1924 it was still in service with the reconnaissance division.

The second Hannover operated by the Latvian air service was serial 7. This machine was built in the Aviation Division workshop and entered service in 1923. In 1924 it was also with the reconnaissance division with serial 21. On the roster of reserve aircraft in 1925, the following year it received a major overhaul and was returned to service. It was last reported in service in 1928.

Netherlands

The Netherlands Luchtvaartafdeling (LVA - Army Air Force) had Dutch neutrality to defend during the war years. Aircraft of all the combatants would intrude into Dutch airspace and sometimes they landed intact enough to be brought into LVA service. During 1918 the LVA’s strength nearly tripled.

75 new aircraft were received and many interned aircraft were repairable. Unfortunately, the technical branch could not handle the influx of aircraft. To this was added a shortage of pilots, fuel was in short supply and pilot training could not keep pace with demand.

Only one Hannover was interned in the Netherlands. CL.II 13180/17, aircraft "7" of Fl Abt 258, force landed in the Netherlands on at 1600 hours on the 15 April 1918. Ltn F.A. Olbrich and Feldwebel M.K. Albusberger were on a flight from Gent to Bapaume when they got lost in the mist and landed, undamaged, at Axel.

The engine was reported as an Opel-Argus No. 1177. It was the 56th interning of a combatant's aircraft in the Netherlands since the start of hostilities.

It received the LVA serial HAN416 0160. (the "0160" referring to the make of engine and the horse power). Repaired and with Netherland's national markings and LVA serial, it was with the 2e Vliegtuigafdeeling on 1 May 1918, when it was reported combat ready. In early December the OLZ (Opperbevelhebber van Land- en Zeemacht - Supreme Commander of Land and Sea forces)

Asked how many combat aircraft were available on 1 November. The result is shown in the table below:

Netherlands LVA Combat Ready Aircraft on 1 November 1918

Type Ready Repair Total

Airco D.H.4 1 - 1

Airco D.H.9 3 5 8

Bristol F2B 1 - 1

DFW C.V 4 3 7

Fokker D.VII 1 - 1

Halberstadt CL.II 2 - 2

Hannover CL.II 1 - 1

LVG C.VI 1 - 1

Sopwith Camel - 1 1

Totals 14 9 23

These aircraft were all interned machines. The Hannover was last recorded as stored in hangar 20 in 1919.

Poland

Almost all Polish Hannover CL.II aircraft were found at Warsaw's Mokotowskie airfield after the end of WWI by the Polish Army. These were remains from the German Fliegerbeobachterschule Warschau and Albatros-Militar-Wekstdtten (REFLA) Warschau. The Poles obtained some 800 ex-German and Austro-Hungarian aircraft from all sources. Included amongst these were at least 30 CL.II, one CL.IIIa and one CL.V biplanes. As there was no indigenous aircraft industry in Poland the Centralne Warsztaty Lotnicze (CWL - Central Aviation Workshops) was formed in Warsaw on 20 December 1918, using as a base the workshops (ex-Albatros REFLA - Warschau) left at the airfield by the Germans. They were to undertake the repair and manufacture of airframes, repair of engines and started to produce airscrews. The Hannover CL.II (Rol) machines were in a poor state but were relatively modern and were amongst the first aircraft refurbished by the CWL. In April 1919, six CL.II biplanes were modified at CWL with new engine mounts to make it possible to install the 150-hp Benz Bz.III and 160-hp Benz Bz.IIIa engine. At least 14 and possibly 17 CL.II machines were repaired and brought into Polish service. Hannovers were well known by CWL personnel, Hannover CL.II biplanes had been used and repaired at Mokotow airfield during WWI. They were given the designation CWL Type 8.

Several were obtained from Germany by semi-legal routes. One CL.IIIa (218/17) was purchased from its German pilot, Ehrpenbeck, near the Upper Silesian town of Czestochowa. CL.V 9671/18 landed in Polish territory at Dobrzyn and was sold by its German pilot. Hannover CL.II and CL.III biplanes were offered to Poland in June 1919, but the Germans wanted hard currency and it was easier to obtain aircraft from France and, from a political point of view, this was a much better arrangement.

The Polish CL.II took part in the fighting on the Ukrainian front, in the war against the Bolsheviks, on the front in Lithuania, on the Pomeranian front and on Upper Silesia. Polish CL.II serial 8.1218 was captured by the Soviet Russians in May 1920. The 8th Reconnaissance squadron operated five Hannover machines at various times while other squadrons had only one or two. The Hannovers were used in Eskadry 6 W 11, a reconnaissance unit. The CL.II was also used by the flying schools.

Polish airmen had different opinions of the Hannovers. They were easy to fly and were stable and controllable at low speeds. They were difficult to bring down, the gunner having a good field of fire. With the new engines they had a high ceiling. However, the CL.II had a low top speed, small range and endurance. The latter was mostly due to the excessive fuel consumption caused by the refurbished engines installed, most being worn to a large extent. Pilots complained that the view from the cockpit was not good as the upper wing was too high. Blankets would be folded and placed on his seat to raise his eye level. The machine tended to fly nose down when the engine was cut. For an inline engine the gyroscopic effect was marked and the aircraft had a tendency to turn to port. A lot depended on the airscrew installed.

In January 1921 the surviving Hannovers were transferred to the flying schools at Grudziadz and Lawica or to the Lawica depot. The type served until 1922-1923, the last being recorded at Graudenz in late 1922.

The CWL also carried out construction of aircraft almost from its inception. It produced copies of the aircraft in its care as it did not have the facilities to undertake design and construction. In March 1919 it was decided to copy the CL.II as there were difficulties in trying to obtain aircraft from abroad. Pilots were consulted as to the feasibility of building the CL.II, the project being under the control of the engineer Lieutenant Karol Slowik. It was predicted that from July 1919 to March 1920, 45 aircraft could be produced. The project soon ran into difficulties. The correct type of plywood was difficult to obtain as well as steel fittings. Some were obtained from scrapped aircraft.

Material for ten machines had been gathered and in May 1919 construction of the first batch of three airframes began. The first machine was completed in July 1919 with an Austro-Daimler Ba 1700 engine, and bore the serial CWL 18.01. It was known as the CWL Slowik or CWL SK-1. There were doubts as to the strength of the machine but the decision was taken to allow it to fly. The first flight of the all-white painted prototype was on 9 August with Lieutenant Boleslaw Skarba as pilot. He refused to fly the aircraft again due to its weak construction; there was a quarrel with the aircraft constructor. As a result, further flights were continued by Second Lieutenant Kazimierz Jesionowski. On 23 August 1919, during an official showing of the aircraft to the head of Polish state, Marshall Jozef Pilsudski and his staff, the aircraft crashed after falling apart in the air when the wings came off. The crew, comprising the project engineer Lieutenant Karol Slowik, and the pilot, Second Lieutenant Kazimierz Jesionowski, were both killed. It was disaster for new-born Polish aviation, Pilsudski losing faith in it.

The second, finished airframe was used for static tests, made in January 1920 and the construction of the third airframe was stopped. The testing was done when a laboratory was opened at the Plage and Laakiewicz Aircraft Factory in Lublin. The bracing cables were found to be only half the strength of those of the original German-built machine. The cause of the accident was the use of materials of inadequate strength in the construction. The ambitious construction plans were now discarded.

The sole CL.V obtained by the Poles was flown to Polish territory by an unknown German pilot and sold for cash. CL.9671/18 had probably been completed after the Armistice and arrived with two machine guns, radio and camera equipment. This modern combat aircraft was tested by the air service in Warsaw until the end of March 1920. The two fixed machine guns and radio equipment were removed and a machine gun for the observer installed and the machine took part in the last operations against Soviet Russia with the 12th reconnaissance squadron. It was scrapped in Polsen at the end of April 1921.

The Polish Hannovers after repairs and engine changes by CWL, were very quickly rushed to the front. In Spring of 1919 they took part in the fighting on the Ukrainian front, in the war against the Bolsheviks, on the front in Lithuania, on the Pomeranian front, and on Upper Silesia. One of the Polish CL.II serial 8.12 from the 8th Polish Reconnaissance squadron was captured by the Soviet Russians in May 1920. The aircraft was captured by infantry. There is no information whether the aircraft was used by the Soviets.

In January 1921 after the Polish-Russian war all the surviving Hannovers were transferred to the flying schools at Grudziadz and Lawica or to the Lawica depot. The type served until 1922-1923, the last being recorded at Grudziadz in late 1922.

Switzerland

Hannover CL.IIIa 9288/17 was interned on 4 December 1917, and given photographed in Swiss markings although it was apparently not taken into service with the Swiss air arm. This was most probably the CL.III that was handed over to the French in December 1919, together with two Albatros C.III biplanes, two Albatros D.Va fighters and two Siemens-Schuckert fighters, a D.III and a D.IV.

USA

In accordance with the Armistice conditions 110 aircraft were handed over to the US at Treves by the Germans to 8 January 1919. Amongst them were six CL.IIIa biplanes.

CL.IIIa 13321/18 and 13339/18 were shipped to the USA. 13339/18 was given the USAS serial 94087, while 3813/18 received the serial 94086. 7005/18 was probably issued to the 12th Aero Squadron in Germany.

On 27 August 1919, one Hawa CL.IIIa was amongst the 177 German aircraft in the USA. There were at least seven Hannover aircraft in the USA in July 1920 and 3892/18 (the one erroneously attributed to Rickenbacker and Chamber's) would have been one of these. Two were at Americus, four at Fairfield and one at Middletown. Americus did not record the serial numbers of their charges and it is thought that this was where 3892/18 was located. The Air Service Report of Survey for 25 October 1921, listed 23 German aeroplanes. They were given a value of $46,000 but were up for survey as it was thought that they could not be disposed of to the civilian market. 3892/18 is included in the 23 aircraft listed. This is the last reference to the machine so far discovered and it may be concluded that it was destroyed along with the other six Hannovers that were brought to the USA.

Identification of Hannover CL.II & CL.III

Aircraft Notes on Visible Features

Prototype Argus III

Unbalanced ailerons. Aileron crank at 1/3 span aileron. Splayed-out two outer ribs on top wing. Four ribs outside of interplane struts on upper wing, five on lower wing. Engine cowl changed on later versions, twin upper tail braces. (See Flugsport 1919, P.417 for side view).

CL.II Argus Three aircraft for Typenprufung CL 4500-4502/17.

Aileron does not project beyond wing. Tail square on prototype. Aileron control wires outside of strut. Aileron crank at 1/2 span aileron. Twin upper tail braces. Balanced elevator. Four ribs outside of interplane struts on upper wing, five on lower wing. Splayed out outer upper wing tip ribs. Dihedral equal top and bottom wings. Modified engine cowl compared with prototype. Cooling louvres below centre section struts.

CL.II early production Argus III CL 9200-9399/17

Balanced aileron does not project past wing. Aileron crank at aileron end. Rectangular fuselage vents on port side. Tail rounded. Aileron control wire inside of strut. Twin upper tail braces.

CL.II 9268/17 & up

Cooling louvre on access port panels. Spreader bar for interplane wires.

CL.II 13075-13374/17

Balanced aileron projected past wing. Braced tail on almost all of this series. Spreader bar for interplane wires. CL 13318-13374 burned in fire. Made up by CL.IIIa with same serials.

CL.III Mercedes 16000-16079/17

Enlarged tail brace. No cooling louvres on port fuselage side.

Hannover Aircraft Orders & Production, 1915-1919

Known Serials Quantity Comments

Hannover CL.II

4500-4502/17 3 Ordered in April 1917

9200-9399/17 200 Ordered in July 1917

13075-13317/17 243 Total of 446 built

Hannover CL.III

16000-16079/17 80 Type test February 1918

Built after Nov. 1918 100 Total of 180 built; 80 built during the war

Hannover CL.IIIa

13318-13374/17 57

16080-16199/17 200

2600-2799/18 200

3800-3899/18 100

6950-7049/18 100

9600-9649/18 50

57 Han. CL.II aircraft were burned in a factory fire that did not get works numbers or military serials. Apparently they were replaced by CL.IIIa aircraft using the missing serials in the C.13xxx/17 batch as shown here.

Total of 707 built

Hannover Aircraft Specifications

Type CL.II CL.III CL.IIIa C.IV

Engine 180 hp Argus As.III 160 hp Mercedes D.III 180 hp Argus As.III 245 hp Maybach Mb.IVa

Span, m 11.95 11.70 11.70 12.56

Length, m 7.80 7.58 7.58 7.84

Height, m 2.75 2.80 2.80 2.95

Wing Area 33.8 m2 32.7 m2 32.7 m2 33.6 m2

Empty Wt., kg 750 741 750 960

Useful Load, kg 360 340 360 435

Gross Wt, kg 1,110 1,081 1,110 1,395

Max Speed, km/h 165 160 165 160

Time to 1,000 m 6.1 minutes 5.3 minutes - 4.5 minutes

Time to 2,000 m 13.8 minutes 11.1 minutes - 8.7 minutes

Time to 3,000 m 23.9 minutes 19 minutes - 13.2 minutes

All the above types carried a fixed, synchronized gun for the pilot and a flexible gun for the observer.

Hannover F 3 Specifications

Source Hawa Booklet Jane's 1919

No. seats 3 2

Dimensions in m

Span 12.000 12

Chord top 1.800 1.8

Chord bottom 1.300 1.3

Gap 1.600 1.6

Stagger 0.800 0.8

Length 7.800 7.8

Area Wings in m2 38.8 33.1

Weight in kg

Empty - 750

Fuel - 110

Loaded 1,110 -

Duration in hours - 3

Range in km 490 -

Speed in kph 165 -

at 2,000 m - 165

Climb in minutes

to 1,000 m - 6.1

to 2,000 m - 13.8

to 3,000 m - 29.9

Engine 185-hp Opel 180-hp Argus

The arrival of the Hannover CL.II at the Front in October 1917 appears to have taken the Allied intelligence agencies by surprise. James McCudden wrote that the Allies first described it in February 1918, some three months after he had first seen one. The British Ministry of Munitions issued monthly Intelligence Reports on "Enemy Aviation for the Month of..." usually published a month or two later. These also contained translations of French reports. That for January 1918 (issued in March) contained translations of a French report on a new artillery ranging and reconnaissance aeroplane - a two-seater of a new type driven down in our lines in December, and caught fire on landing. The following particulars were able to be obtained:

100-hp six-cylinder in-line Opel engine; fuselage ply wood, biplane tail. Armament - two machine guns. This was a Hannover CL.II but its origin could not be determined from the wreckage. The new aircraft created a lot of interest as evidenced by articles in the aviation press.

The 1-15 January 1918 issue of l’Aerophile contained a two-page article entitled "Hammover?" It included sketches of the mysterious biplane tailed German two-seater. This was followed by another two-page spread in the 1-15 March 1918, edition, where "L'Avion Allemand H.W. Hannovranner ou Plutot Halberstadt" was discussed. The 22 May 1918, issue of The Aeroplane’s supplement "Aeronautical Engineering", showed sketches of the "New Halberstadt". The article quoted M. Lagorette of the French magazine L’Aerophile as stating that these curious machines with biplane tail "is most certainly not a Hannover but a Halberstadt." Although several had been shot down, they had been so badly wrecked or burnt that a reconstruction was not possible. Lt Mussat, commanding a battery of AA guns, made a sketch of the machine and "insists that the fuselage is extremely deep." Lagorette suggested that since no trace of cabane struts were found in the wreckage of those shot down, the upper wing must be mounted on the fuselage as in the Roland.