Книги

R.Abate, G.Alegi, G.Apostolo

Aeroplani Caproni: Gianni Caproni and His Aircraft, 1910-1983

135

R.Abate, G.Alegi, G.Apostolo - Aeroplani Caproni: Gianni Caproni and His Aircraft, 1910-1983

In April 1913 Turin hosted the military aircraft and engine competition advertised by the War Ministry in late 1912. In addition to a 10,000 lire cash prize, it was announced that the winning and second placed designs would be ordered in ten and five copies respectively. The Caproni e Faccanoni company entered two Bristol Caproni 80 hp monoplanes, flown by the English pilots Sidney Sippe and Collyns Pizey and identified respectively with contest numbers 11 and 13. The Bristol was a design of Henri Coanda, Caproni’s classmate in Belgium. Since the Army already employed other Bristols, Caproni secured a production license as a fallback in case his Caproni 1913 could not be readied in time. Neither of the Bristols was admitted to the final trials, but a static test was held at Mirafiori on April 17 using a fuselage imported from England in December. Despite the results of the competition, Caproni eventually supplied several Bristols to the Army, the military flying field at Somma Lombardo, near Malpensa, becoming the seat of the Bristol Caproni monoplane school with tenente Renato De Riso as instructor. Maintenance and repairs were entrusted to Caproni, who modified some aircraft with a movable tailplane. Another modification, carried out by the Hendon graduate capitano Ercole Ercole, involved applying brakes to the wheels. Some Bristols were returned to the British company in late March 1913, but others continued in the training role throughout 1914. A British built Bristol, with fuselage number 174, is preserved by the Caproni Museum as the oldest extant Bristol in the world.

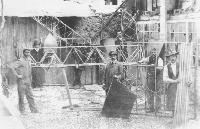

In 1908-9 Caproni met in Paris many students of flight and aviation pioneers, witnessing many flight attempts. He thus began thinking about his first powered aircraft, which he started building in Arco with the limited help of three carpenters equipped with a saw, hammers and a chisel.

The lack of adequate flying areas led Caproni to transfer his base of operations to Lombardy, aided in this by his brother Federico, who had meanwhile graduated from Milan’s Universita Bocconi. The move from Arco to Cascina Malpensa, in the Gallarate prairie, was made in early April 1910. Facilities were again limited, amounting to a single, dilapidated wooden workshop. The two Caproni brothers and their two Arco workers Ernesto Gaias and Ernesto Contrini, known to friends as Emestin (little Ernest) and Emeston (big Ernest), took up residence there.

The biplane was completed in such primitive conditions, with the straightened financial circumstances contributing to the difficulties. Flying activity with the first biplanes was as frequent as possible but, in Gianni Caproni’s own words, “because of the pilots’ inexperience every flight meant breaking the aircraft at the telling moment of landing”.

The lack of adequate flying areas led Caproni to transfer his base of operations to Lombardy, aided in this by his brother Federico, who had meanwhile graduated from Milan’s Universita Bocconi. The move from Arco to Cascina Malpensa, in the Gallarate prairie, was made in early April 1910. Facilities were again limited, amounting to a single, dilapidated wooden workshop. The two Caproni brothers and their two Arco workers Ernesto Gaias and Ernesto Contrini, known to friends as Emestin (little Ernest) and Emeston (big Ernest), took up residence there.

The biplane was completed in such primitive conditions, with the straightened financial circumstances contributing to the difficulties. Flying activity with the first biplanes was as frequent as possible but, in Gianni Caproni’s own words, “because of the pilots’ inexperience every flight meant breaking the aircraft at the telling moment of landing”.

To test the new aircraft Gianni Caproni, portrayed sitting in the pilot's seat, selected Ugo Tabacchi, a native of Verona and one of the few workers of the Malpensa shop. The airplane lifted off on the first attempt, on May 27, 1910, but Tabacchi could not control it upon landing and the biplane was all but destroyed.

The Caproni Museum’s entrance in 1940. A visitor’s log sits on the round table. The Ca.1 and Ca.6, easily recognized by the variable pitch metal propeller, stand alongside the carpet. Directly behind the bronze bust are the Ca.36M’s empennages, partially hiding a Macchi-Nieuport 29 fuselage. By 1943 the decaying military situation forced the Museum to disperse its three main nuclei - Museum, library and archive -, blocking all activity but also preserving much of the material for posterity.

After completing his studies at the Munich Polytechnic and the Institut Montfleur, Gianni Caproni returned to his native land in December 1909. A warehouse in Arco was converted into a simple workshop where, aided by three carpenters, he began building the biplane he had been thinking about since a brief post-graduation spell in Paris. Many good friends lent him a hand, some even financially, but Gianni's closest associate was his brother Federico, who even participated in the physical construction of the aircraft. The photo shows the first biplane in the early stages of manufacture.

The first aircraft was eventually rebuilt, but Caproni had already designed and completed his second design, called Ca.2 and powered by a more reliable 50 hp Rebus engine. Tabacchi was again asked to test it, but this new flight, which took place on August 12, 1910, ended not unlike the first. Another machine was almost completely lost.

A picture of the second Caproni biplane, with the brothers Federico and Gianni Caproni standing and two workers sitting by the machine.

The third biplane, constructed during the 1910-11 winter, was conceived with a lighter structure. A simple bamboo tailboom with three struts replaced the previous trussed fuselage. The wingspan was also greatly reduced, while the engine was carried over from the previous type.

While starting the detailed design of his first monoplane, Caproni built other biplanes. The fifth biplane, which harked back to the third, stood out for its double curvature Coanda airfoil and metal tube tailboom longerons. It was tested by Caproni himself in association with the aviator Baragiola, who had built a hangar for his private Bleriot XI at Vizzola Ticino. The photo show the Ca.6, the sixth Caproni biplane, which also sported the characteristic double curvature airfoil and the lightened tailboom, constructed from hollowed-out wooden tubes. Still powered by the 50 hp Rebus, it was modified following some flights in spring 1911.

The photo show the Ca.6, the sixth Caproni biplane, which also sported the characteristic double curvature airfoil and the lightened tailboom, constructed from hollowed-out wooden tubes. Still powered by the 50 hp Rebus, it was modified following some flights in spring 1911.

The Esposizione dell’Aeronautica Italiana, held in Milan in June-October 1934, was the first major exhibition in Italy devoted to the history of flight. Designed by the best Italian architects and artists, coordinated by Giuseppe Pagano, and actively supported by industry, the show presented a coherent and convincing survey of the development of aviation. Gianni Caproni, who sat on the organizing committee, loaned three of the Caproni Museum’s aircraft, including the Ca.6 shown here.

The Caproni Museum’s entrance in 1940. A visitor’s log sits on the round table. The Ca.1 and Ca.6, easily recognized by the variable pitch metal propeller, stand alongside the carpet. Directly behind the bronze bust are the Ca.36M’s empennages, partially hiding a Macchi-Nieuport 29 fuselage. By 1943 the decaying military situation forced the Museum to disperse its three main nuclei - Museum, library and archive -, blocking all activity but also preserving much of the material for posterity.

In February 1911 Caproni met ingegner Agostino De Agostini, a prominent figure in business and industrial circles. From this stemmed the forming of the Ingg. De Agostini & Caproni Aviazione company, which found a new base at Vizzola Ticino, in part with help from Gherardo Baragiola who already had the use of some land with a small hangar for his Bleriot monoplane. The following months saw the addition of three sheds with the necessary tools, which were used to build the first Caproni monoplane which the Swiss pilot Enrico Cobioni would test in mid June. Flight training activity was developed in parallel with production, with a considerable flow of Italian and foreign student pilots. Despite this the company was short lived and, with De Agostini’s withdrawal, Caproni remained alone.

After a forced hiatus, the Caproni Museum gathered new momentum in the Sixties with the opening of a new display in some of the old Vizzola Ticino hangars. Some of the best preserved aircraft were reassembled here and partially restored, while others remained in storage in Venegono Superiore. The photo shows an outdoor line-up for the 1973 World Aviation Museums Conference.

Louis Bleriot’s successful Channel crossing of July 25, 1909 increased confidence in monoplanes. Like other builders worldwide, impressed by the monoplane’s great structural simplicity and corresponding decrease in drag compared to biplanes, Caproni also turned his attention to these machines: from 1911 to 1913 his design activity was devoted exclusively to training monoplanes, in both single and two seat variants. The first of these, a single seater powered by a 25 hp three cylinder fan-type Anzani, was flown on June 13, 1911 at Vizzola. Originally known simply as “25 hp Caproni monoplane”, shortened to Cm 1 in some internal documents, it became known as Ca.8 in the final Caproni designation system settled in the late Twenties.

A familiar event on every early flying field. The pilot of this Ca.8 appears to have escaped the situation with little more than a few scratches and a big fright. The aircraft’s damage also appears quite limited.

Interest in Gianni Caproni and his aircraft has always remained high, in Italy and abroad. To commemorate the 100th anniversary of Caproni’s birth, in 1986 the Smithsonian’s renowned National Air and Space Museum exhibited in its Early Flight gallery the Caproni Museum’s Ca.9, together with models, drawings, memorabilia, trophies won by Caproni aircraft and several text panels. Returned to Italy in 1988, the Ca.9 is now on display in Trento.

On February 12 and 14, 1912, flying a Ca.11 (originally known as Cm 5) powered by a seven cylinder 50 hp Gnome Omega rotary, pilot Enrico Cobioni established Italian records for speed over a 5 km closed circuit (3min 17sec at 91.370 kph), over a 10 km circuit (66min 30sec at 90.225 kph), and over a straight line (106.242 kph). Between 1911 and 1913 a total of 71 monoplanes of various types were built. This figure, by no means inconsiderable at the time, can be broken down into 16 prototypes and 55 production machines.

March 20, 1912 was a full day for Enrico Cobioni and the Ca.12. In the morning colonnello Vittorio Cordero di Montezemolo, commanding officer of the army’s first aviation unit, was given a half hour flight, climbing to 600 meters in just nine minutes. In the afternoon, pilot and aircraft established world speed records over 250, 300 and 330 km distances. The total distance, itself a record for a three hour flight, was covered with remarkable regularity: the first 100 km were flown in 56min, the next in 57 and the last ones in 56, for an overall average speed of 106.5 kph. The test was interrupted at dusk, despite the fact that the machine had far from exhausted its possibilities: its tanks still held about 48% of the fuel load and 31% of the oil. The flight was monitored by ingegner Vogel of the Societa Italiana Aviazione and, as adjunct commissioners, tenenti Del Giudice and Garino.

On April 16, 1912 Cobioni, flying a Ca.12 with a 60 hp Anzani engine, performed a non stop Vizzola-Adria flight. To overcome a thick fog Cobioni closely followed the course of the Po river, using it as navigational reference. The flight, monitored by officials in places of departure and arrival, covered 449 km in four hours averaging over 112 kph. It was the longest non stop flight carried out in Italy until then. Cobioni could not refill his aircraft in Adria because ... there was no fuel in town, forcing him to dismantle the airplane and send it to Venice by rail. The photo show the Ca.12’s fuselage shortly after being unloaded at the Lido.

Enrico Cobioni made numerous flights in Venice, the first of which on April 22: taking off from the Lido at about 7 pm, Cobioni made a fast low level passage over the Lido beach. On a second flight the pilot climbed to 700 meters before cutting the engine and gliding down to about 50 meters from the campanile of St. Mark in Piazza San Marco before restarting the engine and returning to the Lido amidst the general surprise of the crowd. Several propaganda flights were made in the following days, including one with Caproni, who had by then joined Cobioni in Venice. The final flight was made on April 26, the editor of the daily L’Adriatico and the nephew of commendator Weil being carried as passengers. Young Weil became the first paying passenger in Italian aviation.

Among the many who earned their wings at Vizzola Ticino on Caproni airplanes are several pioneers of Italian aviation who deserve to be singled out, including Clemente Maggiora and count Augusto Palma di Cesnola (graduated in 1911), marquis Pier Carlo Bergonzi who later went on to become an interesting aircraft designer (1912), and the first woman to earn an official licence, Rosina Ferrario, graduated in 1913 and seen here sitting in a Ca.12.

The photo shows the tandem cockpits of the Ca.12 (or Cm 6), powered by a six cylinder, double star, air cooled 60 hp Anzani 6A3 radial. Between March and June 1912 this aircraft established several Italian records for speed and endurance over a closed circuit.

The Ca.13, originally known as Cm 7, was directly descended from the previous Ca.12 which had performed so many memorable flights. A Ca.13 christened “Milano” was donated to the Milan chapter of the Societa Italiana di Aviazione to be presented to the Italian Army. The official handing over ceremony was held at Vizzola Ticino in the afternoon of July 12, 1912 at the presence of civil and military authorities and of a large crowd.

After displaying his personal ability and the Ca.13’s flying qualities to the large crowd of spectators, Enrico Cobioni prepares to land.

One of the moments of the ceremony of July 12, 1912 during which the Ca.13 “Milano” was delivered to the SIA. Among the many other airplanes which took part in the event were a Caproni flown by capitano Carlo Piazza, veteran of the recently concluded Libyan campaign, and a Nieuport flown by tenente Attilio Calderara, the younger brother of the first licensed Italian pilot Mario Calderara.

One of the moments of the ceremony of July 12, 1912 during which the Ca.13 “Milano” was delivered to the SIA. Among the high ranking Army officers in attendance were tenente generate Di Majo, commanding the Milan Army Corps, and maggior generate Pirozzi, commanding the Milan division, respectively second and third from left in the photo.

One of the moments of the ceremony of July 12, 1912 during which the Ca.13 “Milano” was delivered to the SIA. The aircraft's godmother, marchesa Diana Crespi, christened the aircraft by breaking the traditional bottle of champagne and was later taken up for a flight by Cobioni.

The encounter with Carlo Comitti, a wealthy aviation enthusiast, led on November 22, 1911 to the forming of a new company called Caproni & C., with fresh capital and intending to pursue a double line of business in the production of aircraft and pilots. The year 1912 was full of successes and satisfaction for Caproni’s monoplanes, with many well publicised flights, an intense and positive training business and a growing production department.

During the Vienna aviation week in June 1912 Caproni met ingegner Luigi Faccanoni, a well known businessman who had supervised important projects including the Vienna acqueduct. Faccanoni, struck by the qualities of the Caproni monoplanes, considered the possibility of an agreement which came about, after some negotiations, upon his definitive return to Italy. Under the terms of a September 13, 1912 contract the company became Societa Ingegneri Caproni e Faccanoni. But it too did not last long. The school was wound up and liquidated, while the workshops were bought up by the Government, which retained Gianni Caproni’s services as technical director.

During the Vienna aviation week in June 1912 Caproni met ingegner Luigi Faccanoni, a well known businessman who had supervised important projects including the Vienna acqueduct. Faccanoni, struck by the qualities of the Caproni monoplanes, considered the possibility of an agreement which came about, after some negotiations, upon his definitive return to Italy. Under the terms of a September 13, 1912 contract the company became Societa Ingegneri Caproni e Faccanoni. But it too did not last long. The school was wound up and liquidated, while the workshops were bought up by the Government, which retained Gianni Caproni’s services as technical director.

The Ca.14, previously known as Cm 9, was a two seater derived from the Ca.13, with slightly increased dimensions and, for the first time, the seven cylinder 80 hp Gnome Lambda rotary engine. Unlike the Ca.13, where the tandem cockpits had been located very close to each other, the Ca.14 cockpits were somewhat removed. The Ca.14 was designed with an eye to potential military applications but was built to a SIA order requiring, among other things, that the airplane be statically tested by loading the overturned machine with sandbags for a total weight of 2100 kgs, or four times its empty weight.

January 1913 saw a young Russian aviator, Hariton Slavorossov, arrive at Vizzola Ticino from nearby Switzerland. The visit was motivated by Slavorossov's desire to purchase a Caproni propeller for installation in his Bleriot, but Gianni Caproni perceived the Russian’s skill and hired him as test pilot. The perception was proved correct on January 24, 1913 when Slavorossov masterfully tested a 50 hp single seater and two 80 hp two seaters for the Italian Army’s Battaglione Aviatori. The latter were of the new Ca.16 type, or Cm 12, with dual controls: the pilot could disengage the passenger’s set at will. The seats were arranged as on the previous Ca.14. On the same day Slavorossov claimed world speed records for passenger- carrying machines on a 5 km closed circuit, covering 200 km in lh 36min 30sec and 250 km in two hours.

On February 23, 1913 the daily sports newspaper La Gazzetta dello Sport circulated the idea of linking Milan to Rome by air, first proposed by the aristocratic Luigi Origoni, vice president of the Societa Italiana di Aviazione, and cavalier Arturo Mercanti, secretary general of the Touring Club Italiano and correspondent of the Gazzetta. Caproni seized the opportunity and combined it with the delivery flight of the “Milano II” on behalf of SIA. Again flown by Slavorossov, the Ca.16 completed the raid despite a number of incidents arising in part from the adverse meteorological conditions.

The unsuccessful participation in the Italian Army’s 1913 competition for a military airplane, in which Caproni had entered a new monoplane design, ultimately had a positive conclusion: the aircraft rejected in Turin for reasons having little to do with its qualities was later selected specifically for the reconnaissance role by a board comprising the Army’s best pilots and engineers. Thus a small batch of Ca.18 were ordered, while some thought was given to ordering significant numbers in a program involving several other manufacturers. When this opportunity dissolved, the six Ca.18 built were assigned to an observation squadriglia serving in Piacenza with the siege artillery depot and becoming the first aircraft of indigenous design and manufacture in Italian service.

The Ca.17, shown here uncovered, was entered in the Turin trials and represented a Ca.16 updated to achieve greater simplicity and strength.

The Ca.18 was series built and equipped an Army squadriglia. The aircraft was selected for the reconnaissance role by a special panel comprising the main pilots and engineers. Some consideration was also given to the idea of involving other firms in manufacturing it under license, but the project was later dropped.

On June 28, 1914 a Serb extremist shot the Austrian hereditary archduke and his wife in Sarajevo. After a month of frantic diplomatic activity between the European powers, on August 1st Germany declared war on Russia and, two days later, on France. It was the beginning of the First World War, a conflict which saw aviation make a great leap forward. Military orders for larger and more powerful airplanes, to be built in ever increasing series, accelerated the transition from the amateur phase to the industrial one, making large capitals available for research and plant expansion. Italy, which on August 2 had proclaimed its neutrality, declared war on Austria-Hungary on May 24, 1915 after a heated interventionist campaign. Already on August 20 two Capronis, serialled Ca.478 and Ca.480, attacked the airfield at Aisovizza.

The available bombers stemmed from an idea of Gianni Caproni and the generous help of maggiore Giulio Douhet, commander of the Army’s Aviators’ Battalion. Realizing the military potential of the trimotor Caproni was designing when the Vizzola Ticino works were purchased by the Government, Douhet allowed him to build the prototype, which made its first flight in October 1914. To produce the aircraft, a cooperative named Societa per lo Sviluppo dell’Aviazione in Italia was formed in March 1915. It then leased the Vizzola works from the State and launched a production batch of 12 aircraft. Powered by three 100 hp Fiat A.10 engines, these were variously known as Ca.1, Ca.300 hp and Ca.32. A second order of 150 machines, known as Ca.2 or Ca.350 hp, was placed in January 1916. Deliveries were completed in September. A number of these were tested with more powerful engines, heavier weaponry, streamlining.

A noticeable progress was achieved with the third series, strengthened and, more importantly, powered by three 150hp Isotta-Fraschini V.4B engines, which made the Ca.450 designation more common than the official Ca.3. Although the first Ca.300 had already struck targets in Austrian territory, including Lubljana, Trento and Fiume, it took the Ca.450 to fulfill the bombers’ promise. During the summer of 1917 the bombers struck Pola (August 2,3, and 8, with up to 36 aircraft), Assling, Chiapovano. The bombing of Cattaro, carried out by 14 aircraft on 4 October, represented the greatest success before the Caporetto disaster. Despite the losses sustained during the retreat, in November-December the Capronis were used extensively against enemy troop concentrations, dropping hundreds of tons of bombs. From February 19, 1918 a specially formed unit, the 18th gruppo, operated against German targets from French bases. Before returning to Italy it earned Marechal Foch’s compliments.

Also worthy of mention is the plan to train and employ in Italy large numbers of American pilots, under the terms of a September 1917 governmental agreement. In the following February 411 American student pilots, led by Captain Fiorello LaGuardia (already a member of Congress and later Mayor of New York), were under training at Foggia. In March 1918 LaGuardia himself completed the Caproni course and went to the front, flying several operational sorties.

The available bombers stemmed from an idea of Gianni Caproni and the generous help of maggiore Giulio Douhet, commander of the Army’s Aviators’ Battalion. Realizing the military potential of the trimotor Caproni was designing when the Vizzola Ticino works were purchased by the Government, Douhet allowed him to build the prototype, which made its first flight in October 1914. To produce the aircraft, a cooperative named Societa per lo Sviluppo dell’Aviazione in Italia was formed in March 1915. It then leased the Vizzola works from the State and launched a production batch of 12 aircraft. Powered by three 100 hp Fiat A.10 engines, these were variously known as Ca.1, Ca.300 hp and Ca.32. A second order of 150 machines, known as Ca.2 or Ca.350 hp, was placed in January 1916. Deliveries were completed in September. A number of these were tested with more powerful engines, heavier weaponry, streamlining.

A noticeable progress was achieved with the third series, strengthened and, more importantly, powered by three 150hp Isotta-Fraschini V.4B engines, which made the Ca.450 designation more common than the official Ca.3. Although the first Ca.300 had already struck targets in Austrian territory, including Lubljana, Trento and Fiume, it took the Ca.450 to fulfill the bombers’ promise. During the summer of 1917 the bombers struck Pola (August 2,3, and 8, with up to 36 aircraft), Assling, Chiapovano. The bombing of Cattaro, carried out by 14 aircraft on 4 October, represented the greatest success before the Caporetto disaster. Despite the losses sustained during the retreat, in November-December the Capronis were used extensively against enemy troop concentrations, dropping hundreds of tons of bombs. From February 19, 1918 a specially formed unit, the 18th gruppo, operated against German targets from French bases. Before returning to Italy it earned Marechal Foch’s compliments.

Also worthy of mention is the plan to train and employ in Italy large numbers of American pilots, under the terms of a September 1917 governmental agreement. In the following February 411 American student pilots, led by Captain Fiorello LaGuardia (already a member of Congress and later Mayor of New York), were under training at Foggia. In March 1918 LaGuardia himself completed the Caproni course and went to the front, flying several operational sorties.

This Ca.36M, serial 25811, restored to represent LeRoy Kiley’s 11504, is now on display at the United States Air Force Museum in Dayton, Ohio. Preserved by the Caproni Museum since 1928, it was loaned to the USAF in 1988, 14,000 man-hours being expended to return it to its pristine condition. Another Ca.36M, previously owned by bomber ace Casimiro Buttini, is with the Italian Air Force Museum at Vigna di Valle, near Rome.

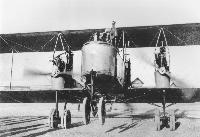

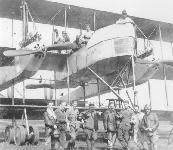

The first Caproni trimotor photographed partially complete at Vizzola Ticino in October 1914. It was designed Ca.1 by the Army and renumbered Ca.31 postwar by its manufacturer. Power came from three Gnome rotaries, with 80 hp units in the tractor outer positions and a single 100 hp pusher in the nacelle. Initially Caproni had envisioned a central position for the engines, two of which, coupled through a differential, would drive the outboard propellers through long shafts. In the interest of simplicity, the prototype was completed with each engine driving its propeller directly.

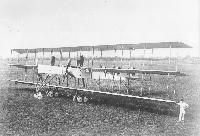

The first Ca.1 batch had 100 hp Fiat A.10 in-line engines and were serialled 478-489. The photo shows Gianni Caproni with sottotenente Giulio Laureati on the second production aircraft. Delivered to the Caproni Biplanes Section (later 1st Caproni squadriglia) at La Comina on August 8, 1915, Ca.479 was still in service on December 3, 1916. Redesignated Ca.32 in the postwar system, these bombers were originally known as Ca.300 because of the total engine output.

Ca.1 serial 1138, bearing pilot Gino Lisa's "Two of diamonds" insignia, shows crew stations to advantage. A track and trolley system, seen in the foreground, was used to ease the task of inserting and extracting the large aircraft sideways from their hangars.

Nine Ca.300 from the second batch, including Ca.1248 shown here, were completed as Ca.2 by replacing the central Fiat A.10 with a 150 hp Isotta Fraschini V4B. Because the rated output now reached 350 hp, the resulting aircraft were also known as Ca.350. Curiously this variant did not receive a new designation in the postwar system. The additional power improved performance and suggested the potential of an entirely Isotta-powered variant.

Besides equipping bomber units, the Ca.3 were also used to fly mail or passengers. In the latter role, in February-April 1922 the Libyan based aircraft were used, together with some SVAs, to resupply the 10th Battaglione Eritreo under siege at Azizia. Over 44 tons of freight, 278 military and 53 civilian passengers were carried in what is believed to have been the world’s first air bridge operation.

Engine runs for a Ca.450. The lack of the forward weapon and the modified gun mounting suggest this machine might have been used for the trial installation of the 25,4 millimeter Fiat gun. At least three aircraft thus equipped - serialled 2314, 2401, 2404 - were on strength with the 16th squadriglia in May 1918.

After some tests carried out by two Ca.5 in the summer of 1917, the Ca.450 serial 2334 was experimentally modified as torpedo bomber. After removing the nose wheel and generally lightening the aircraft, a torpedo harness was fitted to the bottom of the gondola. Despite the fact that with its 700 kg weapon the bomber would exceed its maximum allowable take-off weight, the aircraft was included in the Pola raid of October 2-3 with the stated intention of hitting a battleship. Ca.2334, christened Per la Patria (“For Country”), was crewed by a mixed Army-Navy team and took off with the second wave. As agreed, pilot sottotenente Ridolfi cut the engines above the harbor and glided down. Unfortunately the naval observer tenente di vascello Pecchiarotti, perhaps fearing the Austrian reaction, released the weapon too early. Thus failed the first Italian torpedoing attempt. The photo shows Ca.2334 on the ground.

Caproni crews included several famous pilots. Here, in uniform between Pasquale De Luca and Gianni Caproni is capitano Ercole Ercole.

With the arrival of the new Ca.450, the “Ace of spades” insignia was applied to Ca.2378, flown by Pagliano and Gori over Pola on August 3, 4 and 8, 1917. Gunner-engineer on these flights was sottotenente Pratesi, while the observer’s seat was filled by capitano Gabriele D’Annunzio. The photo shows Gori and Pagliano standing by their aircraft. The nacelle has been decorated with an elaborate list of the missions flown and the vertical motto Repetita luvant (“It is good to repeat”).

When the 1934 exhibition closed, Mussolini ordered the Regia Aeronautica to transfer its historical collections from the Air Force Academy, housed in the Royal Palace in Caserta, to Milan, where they would become part of a proposed National Aeronautical Museum. The idea never bore fruit and the Caproni Museum remained the only aviation museum in Italy. This photograph, dated December 1937, shows that initially the historic aircraft were stored in the workshops.

Caproni crews included several famous pilots. Here, tenente Federico Zapelloni in front of the Ca.2380 he flew during the famous 1917 raids.

Close-up of a Ca.3. Equipped with three 150hp Isotta Fraschini V4B engines - with in-line cylinders despite the designation - this version was widely known as Ca.450. The three engines were individually started by manually throwing the propeller. The poet Gabriele D’Annunzio flew many operational sorties with Capronis, developing a strong tie with their builder. Returning from a raid on Pola, on August 29, 1917 D’Annunzio created for Caproni the motto "Senza cozzar dirocco" (“I batter without clashing”). The battering ram referred to the Caproni name, which means “ram” in Italian, and linked the new weapon to traditional siegecraft.

An agreement between the Italian and US governments led to the training in Italy of 500 American pilots, 406 of which had completed instruction by armistice day. American student pilots, completely without flight experience, started the course on Farmans and later progressed to more complex aircraft. The photo shows Italian personnel hauling a Ca.3 into the Foggia flying line.

The success of the Pola raids convinced D’Annunzio to strike Cattaro. The Distaccamento AR, named after its commander muggiore Armando Armani, was formed for this purpose. It consisted of two flights of seven aircraft, led by D’Annunzio and by capitano Leonardo Nardi. The aircraft were moved to Gioia del Colie on September 24. The raid, which involved crossing 400 km of open sea, was carried out on the night of October 4. Two aircraft were forced back by technical problems, but there were no losses. The photo shows D’Annunzio’s return on board Ca.11503.

For the United States the importance of the Italian training program went beyond the comparatively modest operational deployment, cut short by the armistice. The “Foggiani”, as these pilots were soon nicknamed, represented America’s first experience of strategic bombing, originating a belief in the doctrine which stands unchallenged after almost three quarters of a century. The photo shows Lt. LeRoy Kiley climbing aboard his Ca.3.

The Ca.300’s maiden flight was made at Vizzola Ticino by Emilio Pensuti. Born in Perugia, Pensuti earned his wings at Aviano in 1912 and later became Caproni’s favorite test pilot, making in a single year 385 flights on 41 different types of aircraft. He died in 1918 when a backfiring engine set his plane ablaze. Pensuti managed to glide to the ground, saving Mario Galassini who was on board to conduct some tests.

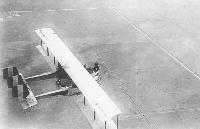

A Caproni flying over the countryside. The lack of camouflage on the upper wing, typical of the early stages of the war, stands out. The Ca.300 had a top speed of 115-127 kilometres per hour, the Ca.350 of 129-133, while the Ca.450 reached 140.

The Technical Direction of Military Aviation ordered 150 Ca.3 in February 1917, followed by a further 100 in June. Deliveries gathered momentum in the late spring, allowing important military actions of great psychological impact to be carried out during the summer. On the photo, a Ca.3 in flight.

A rare glimpse of flying a First World War bomber. Open cockpits and high operating altitudes required crews to wear heavy wool garments and thick leather coats.

A rare glimpse of flying a First World War bomber. Open cockpits and high operating altitudes required crews to wear heavy wool garments and thick leather coats.

A Ca.3 in flight over Venice. The island city was fiercely hit by Austro-Hungarian aircraft and during the Caporetto rout the Italians feared it might be occupied by the enemy.

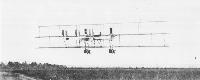

Under normal conditions the Ca.3 lifted off after a ground run of about 150 meters. Upon leaving the ground it was necessary to level off to gather speed before attempting to climb. Different procedures would have caused take-off stalls.

Contrary to what their dimensions would lead to expect, the Capronis possessed excellent maneuverability by the standards of the time. This photo, taken on February 23, 1918 at the Foggia Sud field, shows sergente Federico Semprini pulling his Ca.450 into a low level loop.

Under a February 1915 agreement, the French REP firm, owned by Robert Esnault-Pelterie, built the Caproni trimotors under license and was later joined by SAIB. The aircraft were assigned to the Escadrilles CEP (later CAP) 115 and 130 and made their operational debut on August 5, 1916, seeing effective use even against targets in Germany itself. From November 1917 onwards the French also received some Ca.450s directly from Italy, including the one pictured here. The Italian 18th gruppo was deployed to France in February 1918, dropping 164 tons of bombs in 56 missions before the armistice.

Aircraft of the 8th squadriglia were identified by card suits. Pagliano and Gori’s ace of spades was thus matched by the ace of clubs flown by tenente Mario Martini and sottotenente Gino Lisa (pilots), here seen at La Comina with gunner-engineer Zamengo. Gino Lisa was later awarded the Medaglia d’oro al valor militare.

One of Italy’s most famous bomber crews was formed by tenenti Luigi Gori and Maurizio Pagliano (pilots), capitano Aurelio Barbarisi (observer) and soldato Alessandro Zamengo (motorist-gunner). The crew, assigned to 8th squadriglia, started flying together on the Ca.300 serialled 1151 and christened “Ace of spades”. The view shows the men wearing full flight gear.

In front of a Ca.1 still lacking its military equipment are Gianni Caproni, Emilio Pensuti (at left, in flying suit) and Giovanni Agusta (at right). Hired at Vizzola in October 1913, during the war Agusta served as squadron inspector with Caproni units. He later became technical'administrative director of the Vizzola works, and in May 1921 left the firm to open a SVA and Caproni overhaul depot in Libya.

A Ca.3 from the first production batch preparing for take-off. To avoid damaging the aircraft on the rough airfield surfaces the operating manual advised to taxi with the nose wheel slightly raised from the ground.

A group of soldiers poses for a snapshot by an early Caproni. Between the undercarriage legs the primitive early bomb racks can be made out quite clearly. The lower wing is painted in the Italian flag’s colors, with the outer sectors respectively red and green. The central section’s unpainted fabric replaced the flag’s white band.

The Ca.3 series aircraft were exceptionally long-lived: the type was finally withdrawn from service only in 1927, its long service being part helped by further small production orders placed in 1923-24. Besides equipping bomber units, the Ca.3 were also used to fly mail or passengers.

Aviano airfield, December 1917: a lineup of Ca.3s belonging to 11th gruppo’s 6th squadriglia. Before the Caporetto disaster the field hosted as many as six bomber squadrons. Individual markings were obtained by repeating the squadriglia insignia - in this case, a red circle with a white center - as often as necessary. From left to right we thus have aircraft number two, three and four. The photo also illustrates the practice of supporting the tail booms during periods of inactivity.

Another 1917 picture of Aviano. To achieve a more efficient use of hangar space aircraft were placed inside with alternate right/left facing.

Ten Capronis operated by the 7th stormo bombardamento photographed by an overflying 8th squadriglia Ca.3 during the September 26, 1925 maneuvers. The hangar track and trolley system is clearly seen in front of the buildings.

This photo, taken at Vizzola Ticino in late 1916 or early 1917, summarizes wartime Caproni production. Left to right: the Ca.4 prototype, the unique Ca.37 and Ca.20, and Ca.300 serial 1173.

The proposed conversion of Ca.4 series bombers to obtain the Ca.50 medical aircraft remained on paper but was followed in 1924-25 by the Ca.36S medical transport, a radically modified Ca.36 bomber. In this new version the rugged biplane could carry eight wounded, four of which in the fuselage, replacing fuel tanks and bomb racks, and the remainder behind the cockpit. Access to the enclosed cabin was by means of a retractable airstair.

The Caproni Museum’s entrance in 1940. A visitor’s log sits on the round table. The Ca.1 and Ca.6, easily recognized by the variable pitch metal propeller, stand alongside the carpet. Directly behind the bronze bust are the Ca.36M’s empennages, partially hiding a Macchi-Nieuport 29 fuselage. By 1943 the decaying military situation forced the Museum to disperse its three main nuclei - Museum, library and archive -, blocking all activity but also preserving much of the material for posterity.

After a forced hiatus, the Caproni Museum gathered new momentum in the Sixties with the opening of a new display in some of the old Vizzola Ticino hangars. Some of the best preserved aircraft were reassembled here and partially restored, while others remained in storage in Venegono Superiore. The photo shows the Ca.36M loaned to the USAF Museum in 1988.

Its original Fiat A.10 engines replaced with Colombo D.110s, Ca.3 I-AAMB served with the Scuola Aviazione Caproni in the Twenties. It is seen here in front of the Vizzola Ticino hangars.

As a reprisal for the Austrian bombing of Milan on February 24, 1916 by eleven Lohner B.VIIs, the Italians decided to strike Ljubljana. In the early hours of February 18 ten Ca.300 left La Comina. Three were forced back by engine troubles. Two others were bounced by Austrian fighters, which forced Ca.479 to make an emergency landing in enemy held territory. Despite two dead crew members on board, capitano Oreste Salomone’s Ca.478 was able to return: for this feat he received the first Gold Medal for Military Gallantry awarded to a pilot. The remaining five aircraft reached the target and dropped 26 162 mm bomb-mines from heights ranging between 2500-2800 meters. The photo shows the cover dedicated to the event by the Domenica del Corriere magazine.

Introduced in 1914 and possessing great horizontal and climbing speed, the Ca.20 was the first monoplane fighter built in the world. Had it been fully appreciated, Italy’s dependence on French fighter designs, which continued throughout the First World War, would have probably been very limited. It was derived from the Ca.18 with the addition of the more powerful 110 hp Le Rhone and a special front cowling to minimise drag. The wings had been clipped to obtain greater speed.

This visual comparison between the Ca.4 (redesignated Ca.40 after the war) and the 1914 Ca.20 illustrates the rapid strides in aviation technology brought about by the war. While the structural parts of the both aircraft were quite similar, before the war a project of the Ca.4's size would have been inconceivable.

This photo, taken at Vizzola Ticino in late 1916 or early 1917, summarizes wartime Caproni production. Left to right: the Ca.4 prototype, the unique Ca.37 and Ca.20, and Ca.300 serial 1173.

The Ca.22 had a high wing of the parasol type, intended to improve the pilot’s forward visibility but uniquely provided with a variable incidence mechanism. Powered by the reliable 80 hp Gnome Lambda, the Ca.22 set several world and Italian records.

The importance and quantity of the material gathered by the Capronis soon required the construction of a permanent display structure, designed along a coherent historical perspective. The Caproni Museum thus occupied a large hangar on Taliedo airport, among the firm’s workshops. In this area were placed the Caproni Ca.1, Ca.6, Caproni Bristol, Ca.18, Ca.20, Ca.22, Ca.36M, Ca.42, Ca.53, elements of the Ca.60, Gino Allegri’s Ansaldo SVA serial 11777, the CNA Eta, a Fokker D.VIII fuselage, two Gabardini monoplanes, one of which with floats, a Gabardini G.51, a Macchi-Nieuport 29, a Roland VIb fuselage, a Siemens Schuckert D.IV forward section, tre airship gondolas, a model of Leonardo da Vinci’s unbuilt glider, plus an unspecified number of engines, propellers, and other material. This was certainly among the world’s largest aviation collections, much admired by the many illustrious visitors.

The photo shows the Ca.22 and, behind it, the Ca.53. Between the two the uncovered fuselage and rudder of the Caproni-Bristol can be seen.

The photo shows the Ca.22 and, behind it, the Ca.53. Between the two the uncovered fuselage and rudder of the Caproni-Bristol can be seen.

The Ca.23 was analogous to the Ca.22, except for the fixed incidence wing and the 100 hp Fiat A.10 inline engine. A further variant, the Ca.24, was powered by a 100 hp Gnome Delta rotary and was ordered by the military in thirty copies for distribution to reconnaissance units.

The final prewar Caproni monoplane was the Ca.25, another 1914 parasol design with a structure derived from the early Ca.8/Ca.11 series aircraft. Powered by a six cylinder Anzani fixed radial engine it also sported a variable incidence wing, automatically regulated by the large spring clearly visible in the photo. At least one was used by the Army, as attested by the serial 132 painted on the fuselage side.

In the summer of 1916 Caproni built a small fast bomber and ground attack biplane. Powered by a 250 hp Lancia engine, it never entered production and later acquired the Ca.37 designation.

A Ca. 37 side view. With the aircraft able to reach speeds of about 165 km per hour, the forward gunner’s ample field of fire made a secondary fighter role also possible.

This photo, taken at Vizzola Ticino in late 1916 or early 1917, summarizes wartime Caproni production. Left to right: the Ca.4 prototype, the unique Ca.37 and Ca.20, and Ca.300 serial 1173.

The Ca.38 was derived from the Ca.37. Although the rounded fuselage and tail booms increased its speed somewhat, the aircraft never entered production. It survived the war and was later used as trainer at the Caproni school in Vizzola Ticino.

April 1916 had seen the static testing of the Ca.4, a trimotor triplane which earned the Caproni formula to its extremes. Based on the biplanes’ concept and structure, the Ca.4 stood out because of its much greater size and power. Although it could carry over a ton of bombs, the Ca.4 was penalised by excessive structural complexity and less than fifty were completed in a surprisingly large number of variants.

Further developing the multiengine multiplane theme, in 1916 Caproni conceived the Ca.4. This enormous triplane, powered by tre Fiat A.12bis engines, sacrificed everything to its load carrying possibilities. Tested in July 1916, it was ordered in production the following January.

This visual comparison between the Ca.4 (redesignated Ca.40 after the war) and the 1914 Ca.20 illustrates the rapid strides in aviation technology brought about by the war. While the structural parts of the both aircraft were quite similar, before the war a project of the Ca.4's size would have been inconceivable.

This photo, taken at Vizzola Ticino in late 1916 or early 1917, summarizes wartime Caproni production. Left to right: the Ca.4 prototype, the unique Ca.37 and Ca.20, and Ca.300 serial 1173.

The preseries batch, later called Ca.40, had the prototype’s angular fuselage with a clear frontal section added for the observer.

Gianni Caproni, fourth from left, with pilots and associates in front of a production Ca.4. This version, built from January 1918 onwards and later identified as Ca.41, incorporated several improvements suggested by experience with the first four machines. Together with the possibility of replacing the Fiat A.12 engines with Isotta Fraschini V.5 units, production Ca.4 sported a new, partially enclosed pilots’ nacelle whose rounded lines betrayed a Ca.5 origin.

Six Liberty-engined triplanes, retroactively called Ca.42, were briefly operated from Taranto-Pizzone by the British Royal Naval Air Service with serials N526-N531. The Caproni Flight, as the new unit was called, was led by Squadron Commander R. Whitehead. The increased power cut climbing times in half while adding 500 kg of payload and raising the top speed by 15 km per hour.

The war’s end did not spell the end of the great triplanes: in June 1919 aircraft 14664, used by 181st squadriglia during the war, made a promotional tour of northern Europe. It is seen here on Bruxelles-Haren airport, where on June 14 it carried King Albert of Belgium.

The people in this photo lend scale to the Ca.4’s considerable dimensions. Among other conspicuous details are the bomb harnesses on the lower central gondola, the twin wheels and night landing lights on the wing’s trailing edge.

The war’s end did not spell the end of the great triplanes: in June 1919 aircraft 14664, used by 181st squadriglia during the war, made a promotional tour of northern Europe. It is seen here on Bruxelles-Haren airport, where on June 14 it carried King Albert of Belgium.

Despite the limited production run, the Ca.4 sported a large number of individual differences. British machines, for instance, carried twin Lewis guns in the nose, with the gunners position partially protected by a sort of collapsible screen. The photo also shows a large individual insignia and, less visible, a small eagle on the nose of N526.

Removing the lower gondola allowed heavier weights to be carried, such as the 500 kg bomb shown in the top right photo. This version was later called Ca.52.

An airborne Ca.4. Photos cannot record the impression the Ca.4’s majestic size and power made in its day.

In 1920 Ca.4 5353 was converted into seaplane by adding a pair of floats not unlike those designed by Guidoni for the Ca.47. It was also experimentally equipped with two underwing torpedo harnesses. This version was indicated as Ca.43 in the postwar system.

A final Ca.4 derivative was the Ca.51, easily recognized by its biplane horizontal tail. The rear gunner’s position can be made out amidst the six rudders.

March 1917 saw the first flight of the Ca.600 hp (or Ca.5), which maintained the Ca.3 formula with increased wingspan and chord and somewhat improved streamlining. A new plant was built at Taliedo, on the outskirts of Milan, with increased floor space and the world’s first concrete runway. At the same time, the sudden availability of a thousand 200 hp Fiat A.12 engines and the interest shown abroad, the Direzione Tecnica dell’Aviazione Militare issued a production plan calling for 150 Ca.600 in 1917, followed by a thousand in 1918, eventually' increased to 4015. Orders were placed with a consortium including Breda, Miani & Silvestri, San Giorgio, Piaggio, Reggiane, Savigliano, Bastianelli. In February 1918 other Ca.5, powered with Liberty engines, were ordered by the US government to the Standard Aircraft Corp., Curtiss and the Fisher Body Co. Difficulties in administering this huge contract - for which workers had to be trained and materials found - limited actual deliveries before the war’s end to about 700 aircraft. In operational service, the aircraft’s overall positive behaviour was negatively affected by the Fiat engine’s notorious habit of catching fire in flight.

Having exhausted the original trimotor’s potential with the Ca.450, during the 1916-17 winter Caproni studied a more powerful derivative. The aircraft which emerged, called Ca.5 by the Italian Army, shared its predecessor’s general layout but differed in every detail. Wing span and chord were increased; the radiators were placed in the nose and tail booms; the nose wheel suppressed. The basic type, indicated as Ca.44 in the postwar system, was powered by three 200 hp Fiat A.12 engines, large quantities of which had been made available by the cancelling of orders for obsolete SP and SIA 14B biplanes.

The Ca.5 was also flown with 250 hp Isotta Fraschini V.6 engines, obtaining the version later identified as Ca.45. This group photo, in which Gianni Caproni is the sixth from the left, is taken in front of an aircraft built at Vizzola Ticino. The bomber appears to be painted green overall and has unusual underwing roundels.

Ca.5 SC 42119 is one of three Liberty powered aircraft delivered by Fisher Body to the United States Signal Corps in 1918. The rampant ram and excellent finish are clearly evident.

The Ca.5’s internal radiators were beset with cooling problems. Although the new position cut drag somewhat, cooling was also reduced. One the various modifications attempted to correct the problem is seen on this American aircraft at Mineola: the fuselage lines are noticeably altered.

Another view of the Liberty-equipped Ca.5 with its boxy nacelle, side mounted radiators and clear observation panels on the nose.

The American pilots James Bahl, at left, and DeWitt Coleman, at right, standing by their Ca.5. Shot down during an operational sortie they were awarded respectively a medaglia d'oro and a medaglia d'argento.

LaGuardia at Taliedo, taking delivery of a Ca.5 for the US Army. A strong opponent of the SIA 7, whose dangerous unreliability the Americans had experienced first hand, LaGuardia became instead an ardent supporter of the Caproni bombers.

From the basic Ca.5 design maggiore Alessandro Guidoni derived the Idrovolante Caproni (I.Ca., retroactively known as Ca.47 postwar) by replacing the undercarriage with two Zari floats, connected to the fuselage with elastic mounts. The first machine was sent to Venice for testing August 1917 but was unfortunately destroyed by an incendiary bomb before any tests were carried out. A second machine, readied and proposed to the Navy as torpedo bomber, was also lost during a ferry flight between Sesto Calende and La Spezia.

The second I.Ca taxying at Sesto Calende. After the war Piaggio completed ten by converting a batch of Ca.5 landplanes.

Caproni’s first attempt at producing an aircraft that would carry badly wounded soldiers to properly equipped hospitals dates to the First World War, when a Ca.5 biplane bomber was modified by installing two stretchers on the top of its twin tail booms. To provide a measure of protection from weather and propwash, the stretchers were partially faired. Also known as Ca.45, the aircraft could also carry two lightly wounded men in the main nacelle.

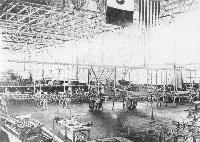

In the early part of the war aircraft had been ordered piecemeal in small batches. The policy changed when the Republican member of Parliament Eugenio Chiesa was appointed commissioner of aeronautics. Among the types selected for mass production was the Ca.5, a dedicated Caproni Aircraft Production Office being established in Milan. The office, run first by capitano Oscar Sinigaglia and later by capitano Odiemo, placed orders for 4,015 aircraft with eight Italian companies. Output was negatively affected by the difficulty of introducing aircraft manufacturing techniques in non-aviation firms. Thus in 1918, while Caproni completed 359 bombers, the performance of other program participants was negligible. The photo show Ca.5 production.

The Americans took an active interest in the Ca.5, ordering 1,050 aircraft from Standard Aircraft, Curtiss and Fisher Body. Equipped with three 450 hp Liberty engines, this version was referred to postwar as Ca.46. A comparison with the Handley-Page O/400, also selected for production in the United States, showed the Caproni to be 15 kilometers per hour faster, to climb almost twice as fast, to have one-third more range, and to cost 29,850 dollars instead of 57,900. The Handley-Page could carry a 900 kg payload - 300 more than the Caproni. On the photo, Standard Aircraft’s assembly hall in Elizabeth, New Jersey.

In 1917 the Technical Direction of Military Aviation asked for a fast bomber with a Fiat A.14 engine, capable of carrying a 400 kg bomb load at speeds around 200 km per hour. The Caproni design, later labelled Ca.53, had a big wooden fuselage and triplane wings. Performance estimates were not met, in part because the A.14 was replaced with a heavier 450 hp Tosi V-12. Committed to Ca.5 production, the company could not support a full development effort and the project was abandoned. The sole prototype is now with the Caproni Museum.

The importance and quantity of the material gathered by the Capronis soon required the construction of a permanent display structure, designed along a coherent historical perspective. The Caproni Museum thus occupied a large hangar on Taliedo airport, among the firm’s workshops. In this area were placed the Caproni Ca.1, Ca.6, Caproni Bristol, Ca.18, Ca.20, Ca.22, Ca.36M, Ca.42, Ca.53, elements of the Ca.60, Gino Allegri’s Ansaldo SVA serial 11777, the CNA Eta, a Fokker D.VIII fuselage, two Gabardini monoplanes, one of which with floats, a Gabardini G.51, a Macchi-Nieuport 29, a Roland VIb fuselage, a Siemens Schuckert D.IV forward section, tre airship gondolas, a model of Leonardo da Vinci’s unbuilt glider, plus an unspecified number of engines, propellers, and other material. This was certainly among the world’s largest aviation collections, much admired by the many illustrious visitors.

The photo shows the Ca.22 and, behind it, the Ca.53. Between the two the uncovered fuselage and rudder of the Caproni-Bristol can be seen.

The photo shows the Ca.22 and, behind it, the Ca.53. Between the two the uncovered fuselage and rudder of the Caproni-Bristol can be seen.

The Ca.4 series triplanes gave life to the Ca.48, 58 and 59, three and five engined giants with up to 2,000 hp installed which could seat 25-30 passengers. The intense promotional use - the Ca.48 flew as far as Holland - was not met by a comparable commercial success. Then disaster struck: on August 2, 1919 a Ca.48 fell near Verona killing the seventeen people on board, the great majority of which were aviation writers. This event sunk all hopes of rapid commercial airline development in Italy: in the wake of the disaster the government even dissolved the General Directorate of Aeronautics which had been formed within the Ministry of Maritime Transports, transferring its duties to the War Ministry’s Civil Aviation Office. The inquiry, carried out by medaglia d’oro holder Ercole Ercole, followed for the first time the method of reconstructing the entire airplane to establish the point and time of impact of every piece. It was thus determined that the disaster had been caused by a camera which, dropped by a passenger, had struck the central engine’s propeller and been projected against the empennage, severing it. The board’s findings were published too late to stave off a wave of diffidence towards bombers converted for airline duty.

By late 1918 the Ca.4 triplane had already spawned a commercial derivative, later called Ca.48, with a 17 passenger cabin and 1200 hp of total engine output. This aircraft was demonstrated as far away as Holland.

An eloquent dimensional comparison of the Ca.48 and Ca.57 transports. To the right is Taliedo’s concrete runway, built for the great bombers and inspired by Roman road building techniques.

A rear view of the cabin of the Ca.48, sporting an immaculate finish. The open upper deck could seat both pilots and up to six passengers, one of whom clearly seen in the photo.

The cabin’s interior is shown. The fine woods and velvet create the impression of a turn of the century luxury railroad car. The top engine’s position can be made out clearly on the ceiling at the back of the cabin.

Gianni Caproni, the famous builder of Italian aircraft, was bom on July 3,1886 in Massone, a small town in the comune of Arco, in the province of Trento. He left his hometown very young to attend the Munich Polytechnic, graduating in civil engineering in 1907: he was only 21 years old. In the following year he attended a special course in electrical technology in Belgium, at Liege's Institut Montfleur, and obtained a further electrical engineering diploma.

During that period he met Henri Coanda, a brilliant engineer of Rumanian origin of his same age, with whom he built a biplane glider which made several successful flights in Blaumal, in the Ardennes.

During that period he met Henri Coanda, a brilliant engineer of Rumanian origin of his same age, with whom he built a biplane glider which made several successful flights in Blaumal, in the Ardennes.

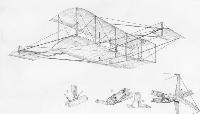

Gianni Caproni’s first aeronautical construction dates to 1908. The biplane glider shown here was built in collaboration with classmate Henri Coanda, an engineer of Rumanian origin. The glider was successfully flown at Blaumal, in the Belgian Ardennes.

A sketch of the second unbuilt Caproni-Coanda glider, which differed from the first in many respects including the addition of canard foreplanes. Together Caproni and Coanda completed three other studies for gliders.

Gianni Caproni began his association with De Agostini in early 1911. That summer saw the two partners devote most of their activity to the flying school. The May-August period saw twelve pilots earn their wings, including many who would later become famous names in Italian aviation, like capitano Riccardo Moizo, Enrico Cobioni, count Costantino Biego and Clemente Maggiora. Among the first foreign student pilots was Konstantin Akakew who in 1921 became the first commander of the Soviet air force. He promptly ordered from Caproni several aircraft, undelivered because of political considerations, and later had Douhet’s book The Command of Air translated in Russian.

The crowd of peasants from neighbouring villages staring at De Agostini's Savary biplane serve as a reminder that novelty, fascination and adventure were integral components of early aviation.