Книги

Centennial Perspective

J.Herris

Rumpler Aircraft of WWI

398

J.Herris - Rumpler Aircraft of WWI /Centennial Perspective/ (11)

An interesting collection of two-seaters, typifying the equipment of 1917-18. In the foreground is a Rumpler C IV, the other aircraft being a Rumpler C VII, a Hannover CL IIIa and a D.F.W. C V.

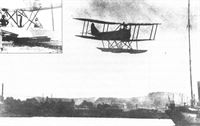

Two Rumplers are lined up in this well-known photograph with a Hannover CL.II and DFW C.V in the background. Unusually, the early Rumpler nearest the camera, C.IV 8267/16, is covered with printed camouflage fabric. The second Rumpler, C.IV 6695/16, was sent back to "Lager West" from AFP 6 in April 1917 for strengthening of the rear fuselage.

Two Rumplers are lined up in this well-known photograph with a Hannover CL.II and DFW C.V in the background. Unusually, the early Rumpler nearest the camera, C.IV 8267/16, is covered with printed camouflage fabric. The second Rumpler, C.IV 6695/16, was sent back to "Lager West" from AFP 6 in April 1917 for strengthening of the rear fuselage.

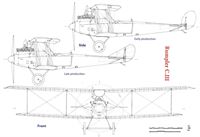

LVG C.II 2135/15 is at left foreground and three late-production Rumpler C.III aircraft rest in the right foreground on 16 April 1917. Interestingly, there are no insignia on the rudders of the C.III aircraft. A Rumpler C.I is in the center background with another LVG C.II at right background.

Rumpler C.IV 8424/16 Dalila of the first production batch undergoes maintenance.This early production C.IV is the subject of Steve Anderson's cover painting. LVG C.V aircraft are on both sides of Dalila.

Rumpler Taubes

On July 21 1910, Edmund Rumpler obtained an exclusive, five-year manufacturing license for Taube aircraft from Austrian inventor Igo Etrich. After a series of flight demonstrations, on Oct. 30, 1910, the Prussian army ordered five Taubes from Rumpler. However, the German patent office invalided Etrich's Taube patent in September 1911 and the Taube design became public domain. Immediately, many German companies started building aircraft to the Taube configuration due to its inherent stability and safety. Understandably, Rumpler then refused to honor the license agreement or pay license fees. Rumpler continued to build Taubes that were essentially the same as the Etrich design, and so Etrich successfully sued Rumpler. However, the amount of the damages awarded was small compared to the amount Rumpler was making from selling aircraft to the Fliegertruppe. The military was keen on the Taube due to its inherent stability and safety, a key advantage in these early days of aviation. As a result, the army purchased a wide variety of Taubes from different manufacturers, with the greatest number being purchased from Rumpler.

The Taube’s limitations gradually became evident, and few were purchased after 1914, when the configuration was clearly obsolete. The Taube had high drag, so speed, climb, and ceiling were limited. And in combat, its inherent stability became a problem,- it was simply too stable and difficult to maneuver to dodge anti-aircraft fire or elude an attacking aircraft. Fortunately, there were few attacking aircraft during the war's early months.

On September 4, 1913, a Rumpler Taube lost a wing during the annual army maneuvers and the two airmen were killed. This caused the German military authorities to perform their first serious structural tests on aircraft, with the result that the Rumpler Taube’s safety factor was found to be 3.42 at best. To express it differently, the Rumpler Taube could withstand a G-loading of 3.42 G's before its structure failed. To put that in perspective, a normal category light aircraft in the USA must sustain a load factor of 3.8 without damage, and 150% of that stress, or a load factor of 5.7 Gs, before structural failure occurs. To be certified as an acrobatic aircraft, the load factors would be 6.0 Gs without damage and 9.0 Gs before structural failure. To return to the Rumpler Taube, one aircraft (A.28/12) tested had a safety factor of 3.42, but another, A.46/13, had a safety factor of only 2.89! This was not strong enough to be safe for routine flight let alone the stress of combat missions.

Recognizing the Taube configuration was obsolete, the army started purchasing biplanes before the war started and disposed of 55 older, worn out Taubes the end of June 1914, just before the war. Although the army had to purchase additional Taubes early in the war to make up losses, the Taube’s days were clearly over. Interestingly, Rumpler Taubes did not last long at the front after hostilities started; the Gotha Taubes were more robust and better able to withstand the rigors of operational service.

Rumpler Taubes Purchased by the Fliegertruppe (Prussian Army)

Year Quantity

1911 10

1912 48

1913 73

1914 3

On July 21 1910, Edmund Rumpler obtained an exclusive, five-year manufacturing license for Taube aircraft from Austrian inventor Igo Etrich. After a series of flight demonstrations, on Oct. 30, 1910, the Prussian army ordered five Taubes from Rumpler. However, the German patent office invalided Etrich's Taube patent in September 1911 and the Taube design became public domain. Immediately, many German companies started building aircraft to the Taube configuration due to its inherent stability and safety. Understandably, Rumpler then refused to honor the license agreement or pay license fees. Rumpler continued to build Taubes that were essentially the same as the Etrich design, and so Etrich successfully sued Rumpler. However, the amount of the damages awarded was small compared to the amount Rumpler was making from selling aircraft to the Fliegertruppe. The military was keen on the Taube due to its inherent stability and safety, a key advantage in these early days of aviation. As a result, the army purchased a wide variety of Taubes from different manufacturers, with the greatest number being purchased from Rumpler.

The Taube’s limitations gradually became evident, and few were purchased after 1914, when the configuration was clearly obsolete. The Taube had high drag, so speed, climb, and ceiling were limited. And in combat, its inherent stability became a problem,- it was simply too stable and difficult to maneuver to dodge anti-aircraft fire or elude an attacking aircraft. Fortunately, there were few attacking aircraft during the war's early months.

On September 4, 1913, a Rumpler Taube lost a wing during the annual army maneuvers and the two airmen were killed. This caused the German military authorities to perform their first serious structural tests on aircraft, with the result that the Rumpler Taube’s safety factor was found to be 3.42 at best. To express it differently, the Rumpler Taube could withstand a G-loading of 3.42 G's before its structure failed. To put that in perspective, a normal category light aircraft in the USA must sustain a load factor of 3.8 without damage, and 150% of that stress, or a load factor of 5.7 Gs, before structural failure occurs. To be certified as an acrobatic aircraft, the load factors would be 6.0 Gs without damage and 9.0 Gs before structural failure. To return to the Rumpler Taube, one aircraft (A.28/12) tested had a safety factor of 3.42, but another, A.46/13, had a safety factor of only 2.89! This was not strong enough to be safe for routine flight let alone the stress of combat missions.

Recognizing the Taube configuration was obsolete, the army started purchasing biplanes before the war started and disposed of 55 older, worn out Taubes the end of June 1914, just before the war. Although the army had to purchase additional Taubes early in the war to make up losses, the Taube’s days were clearly over. Interestingly, Rumpler Taubes did not last long at the front after hostilities started; the Gotha Taubes were more robust and better able to withstand the rigors of operational service.

Rumpler Taubes Purchased by the Fliegertruppe (Prussian Army)

Year Quantity

1911 10

1912 48

1913 73

1914 3

The Navy used land-based Rumpler Taube in addition to Rumpler Taube floatplanes. Rumpler Taube given Naval serials include S8, S9, S20, S21, S22, S42 (formerly A.131/13), and S43 (formerly A.133/13), the last two transferred from the Army.

Rumpler Taube A.10/12 was an early, pre-war aircraft with a four-cylinder Argus engine. The observer was seated in front for best visibility, and the aft-seated pilot had wing cut-outs for enhanced downward field of view.

Early Rumpler Taube displaying the characteristic Taube wing and tail planform.

A series of German aeroplanes at Johannisthal from photographs kindly sent to us by the Hon. Lady Shelley. - Rumpler-Taube in flight.

A series of German aeroplanes at Johannisthal from photographs kindly sent to us by the Hon. Lady Shelley. - Rumpler-Taube in flight.

The Rumpler 3C Taube was more streamlined development of the original Rumpler Taube, itself a copy of the Etrich Taube. Power was a 100 hp Mercedes D.I six-cylinder engine. The large wing cut-outs are to give the pilot and observer good downward visibility for its role as a reconnaissance aircraft. A claw brake is fitted under the axle.

Streamlining became a Rumpler hallmark. The Rumpler 3C Taube was the aircraft type in which Linnekogel climbed out of the cockpit in flight and held on to the support pylon while the aircraft flew itself hands-off. This demonstrated not only his courage but the inherent stability of the Taube design that was so prized before the war when primitive aviation was very hazardous.

Crewmen in front of an early Rumpler Taube with "Rumpler Eindecker" painted on the fuselage and tactical number "16" on the aft fuselage.

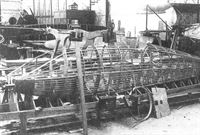

Rumpler Taube in production. Rumpler gained an early reputation based on building and selling copies of the Etrich Taube. Rumpler Taubes won many aviation awards before the war.

Rumpler Taube floatplane. The German navy purchased at least three Rumpler Taube floatplanes, Marine Numbers E1, E4, and E8, all powered by 100 hp Argus engines.

Early Rumpler Seaplanes

Starting in 1914 Rumpler developed a flying boat that remained a single prototype and a small series of floatplanes developed from the Rumpler 4A13, itself a more powerful development of the Rumpler B.I unarmed two-seat trainer and reconnaissance airplane.

As was typical of German naval aircraft, there were a number of variations on the basic design with limited production. As the war progressed Rumpler focused on two-seat reconnaissance airplanes for the Army, which purchased almost 20 times more airplanes than the Navy.

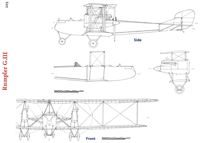

Rumpler 4B11, 4B12, & 4B13

The Rumpler 4B11 and 4B12 were two-seat reconnaissance and training floatplanes based on the Rumpler 4A13 landplane. Both were built in very small numbers for the Navy. The 4B11 was powered by a 100 hp Mercedes D.I. The 4B12 had the more powerful 150 hp Benz Bz.III. The 4B13 was similar except powered by a 160 hp Gnome rotary engine. All three types were conventional wood, wire, and fabric designs typical of their era.

Rumpler 4B Production

Type Qty Marine Numbers

4B11 7 49, 64, 86-90

4B12 31 51, 101-110, 241-253, 436-442

4B13 1 50

Starting in 1914 Rumpler developed a flying boat that remained a single prototype and a small series of floatplanes developed from the Rumpler 4A13, itself a more powerful development of the Rumpler B.I unarmed two-seat trainer and reconnaissance airplane.

As was typical of German naval aircraft, there were a number of variations on the basic design with limited production. As the war progressed Rumpler focused on two-seat reconnaissance airplanes for the Army, which purchased almost 20 times more airplanes than the Navy.

Rumpler 4B11, 4B12, & 4B13

The Rumpler 4B11 and 4B12 were two-seat reconnaissance and training floatplanes based on the Rumpler 4A13 landplane. Both were built in very small numbers for the Navy. The 4B11 was powered by a 100 hp Mercedes D.I. The 4B12 had the more powerful 150 hp Benz Bz.III. The 4B13 was similar except powered by a 160 hp Gnome rotary engine. All three types were conventional wood, wire, and fabric designs typical of their era.

Rumpler 4B Production

Type Qty Marine Numbers

4B11 7 49, 64, 86-90

4B12 31 51, 101-110, 241-253, 436-442

4B13 1 50

The Rumpler 4B12 was powered by a 150 hp Benz Bz.III. The Rumpler 4B series were developments of the 4A13 landplane. This unmarked aircraft may have been the prototype seaplane; it still uses the small rudder of its landplane ancestors while later seaplanes had a larger rudder due to the destabilizing effect of the floats.

Rumpler 4B12; no Marine Number is visible and the rudder is smaller than production machines, indicating this is the 4B12 prototype.

Rumpler Taube in the snow is visited by a woman; details are not known. The national insignia appears to be painted on the elevator in addition to the normal locations.

Rumpler Taube 4C with eye-catching lettering identifying the manufacturer. It worked; Rumpler was one of the most well-known prewar German aircraft manufacturers.

The Rumpler Taube 4C, normally powered by a 100 hp Mercedes D.I, was the last Rumpler Taube design. For improved maneuverability it had conventional ailerons and elevator. (Peter M. Bowers Collection/The Museum of Flight)

Rumpler 1914 Military Mono. The tail of the Rumpler 4C looked like that of the Rumpler B.I biplane that was soon to follow the Taube into production.

In September 1914 aerial reconnaissance by both airplanes and airships was critical to German victories over much larger Russian forces at Tannenburg. In recognition of this historic feat General von Francois is photographed in front of the Rumpler Taube of Lt. Canter, one of the heroic flyers of Tannenburg, and his observer at right.

The Rumpler Taube 4C was usually powered by a 100 hp Mercedes D.I engine, although a 125 hp Benz Bz.II was also used.

Rumpler 4E Flying Boat

The Rumpler 4E was a flying boat built in 1914 powered by a 150 hp Benz Bz.III engine. Records indicate that only one aircraft, Marine Number 47, was built.

The Rumpler 4E was a flying boat built in 1914 powered by a 150 hp Benz Bz.III engine. Records indicate that only one aircraft, Marine Number 47, was built.

Like most Rumpler designs the Rumpler 4E was well thought out and constructed, with clean lines for a biplane flying boat. Regardless of its qualities, the German Navy favored floatplanes over flying boats due to the cold waters around Germany. Floatplanes kept the crew further away from the cold water and kept them dryer and warmer.

The Rumpler 4E flying boat seemed to be much more popular with postcard publishers than with the Navy; there are three postcards of it here and a fourth on the next page.

Rumpler B.I

By 1914 it was increasingly clear that the biplane had an inherently superior performance compared to the Taube, having lower drag and therefore higher speed, climb rate, and ceiling. Rumpler designed their unarmed biplane, factory designation 4A, in 1914, and the aircraft was purchased by the army as the Rumpler B.I. Powered by a 100 hp Mercedes D.I, the Rumpler B.I was a good aircraft for its time, with good performance and flying qualities, and gave satisfactory service. The Rumpler 4A13 derived from the 4A/B.I had a balanced rudder and the same engine. The Rumpler 4A14 was similar but powered by a 150 hp Benz Bz.III.

The Austro-Hungarian Luftfahrtruppen purchased a total of 31 Rumpler B.Is. They were used by Fliks 4, 5, 9, and 13 for bombing and reconnaissance and were used as trainers at least through August 1918.

Rumpler B.I Specifications

Engine: 100 hp Mercedes D.I

Wing: Span 13.0 m

General: Length 8.4 m

Height 3.1 m

Empty Weight 750 kg

Loaded Weight 970 kg

Maximum Speed: 145 kmh

Military aircraft serials for 1914 and 1915 are complicated, as there were impressments and aircraft taken over from the factories as available. This means the serials were often not typical numbers. Sometimes the aircraft type changes with each serial within a series of numbers. (Data courtesy Reinhard Zankl.)

Rumpler B.I

1914

B.362/14 - B.395/14 (34 a/c) Maybe more, but certainly not more than B.360/16 to B.406/16

B.470/14 - B.487/14 (18 a/c)

B.509/14 (1 a/c) Range 506-511/14 so far uncovered by other types*

B.567/14 (1 a/c) Range 562-570/14 so far uncovered by other types*

B.669/14 (1 a/c) Also noted as Av B.I

B.708/14 - B.760/14 (53 a/c) Bordered by Av. B.I 707/14 and Alb B.II B.766/14*

B.959/14 (1 a/c) Bordered by LVG B.I 950/14 and Go B.I 960/14*

B.1018/14 - B.1042/14 (25 a/c) Bordered by Alb B.I 1017/14 and Fok B.I 1043/14*

B.1196/14 (1 a/c)

1915

B.352/15 - B.355/15 (4 a/c) Bordered by Eu B.Ш 350/15 and Av B.I 359/15*

B.367/15 (1 a/c) May be a mis-recorded B.367/14

B.383/15 (1 a/c)

B.955/15 - B.966/15 (12 a/c)

Note: * doesn't mean the uncovered serials have to be Rumpler B.I

Several Rumpler B.I aircraft were used by the Rumpler flying school (Militar Flieger Schule Muncheberg) which were owned by the Rumpler factory and had no military serial.

The Navy received 24 Rumpler B.I aircraft with various engines:

S.37-S.41 (5 a/c)

S.59-S.65 (7 a/c)

S.93-S.95 (3 a/c)

S.128-S.135 (8 a/c)

S.163 (1 a/c)

By 1914 it was increasingly clear that the biplane had an inherently superior performance compared to the Taube, having lower drag and therefore higher speed, climb rate, and ceiling. Rumpler designed their unarmed biplane, factory designation 4A, in 1914, and the aircraft was purchased by the army as the Rumpler B.I. Powered by a 100 hp Mercedes D.I, the Rumpler B.I was a good aircraft for its time, with good performance and flying qualities, and gave satisfactory service. The Rumpler 4A13 derived from the 4A/B.I had a balanced rudder and the same engine. The Rumpler 4A14 was similar but powered by a 150 hp Benz Bz.III.

The Austro-Hungarian Luftfahrtruppen purchased a total of 31 Rumpler B.Is. They were used by Fliks 4, 5, 9, and 13 for bombing and reconnaissance and were used as trainers at least through August 1918.

Rumpler B.I Specifications

Engine: 100 hp Mercedes D.I

Wing: Span 13.0 m

General: Length 8.4 m

Height 3.1 m

Empty Weight 750 kg

Loaded Weight 970 kg

Maximum Speed: 145 kmh

Military aircraft serials for 1914 and 1915 are complicated, as there were impressments and aircraft taken over from the factories as available. This means the serials were often not typical numbers. Sometimes the aircraft type changes with each serial within a series of numbers. (Data courtesy Reinhard Zankl.)

Rumpler B.I

1914

B.362/14 - B.395/14 (34 a/c) Maybe more, but certainly not more than B.360/16 to B.406/16

B.470/14 - B.487/14 (18 a/c)

B.509/14 (1 a/c) Range 506-511/14 so far uncovered by other types*

B.567/14 (1 a/c) Range 562-570/14 so far uncovered by other types*

B.669/14 (1 a/c) Also noted as Av B.I

B.708/14 - B.760/14 (53 a/c) Bordered by Av. B.I 707/14 and Alb B.II B.766/14*

B.959/14 (1 a/c) Bordered by LVG B.I 950/14 and Go B.I 960/14*

B.1018/14 - B.1042/14 (25 a/c) Bordered by Alb B.I 1017/14 and Fok B.I 1043/14*

B.1196/14 (1 a/c)

1915

B.352/15 - B.355/15 (4 a/c) Bordered by Eu B.Ш 350/15 and Av B.I 359/15*

B.367/15 (1 a/c) May be a mis-recorded B.367/14

B.383/15 (1 a/c)

B.955/15 - B.966/15 (12 a/c)

Note: * doesn't mean the uncovered serials have to be Rumpler B.I

Several Rumpler B.I aircraft were used by the Rumpler flying school (Militar Flieger Schule Muncheberg) which were owned by the Rumpler factory and had no military serial.

The Navy received 24 Rumpler B.I aircraft with various engines:

S.37-S.41 (5 a/c)

S.59-S.65 (7 a/c)

S.93-S.95 (3 a/c)

S.128-S.135 (8 a/c)

S.163 (1 a/c)

This aircraft may be the Rumpler B.I prototype. Here is Sanke card 260. The B.I was a reliable replacement for the obsolete Taube and had good flying qualities, making it suitable for training use as well as operational reconnaissance missions.

The Rumpler military flying school at Muncheberg circa 1916/17. Rumpler B.I trainers crowd the hangar.

The Rumpler B.I was of conventional wood, wire, and fabric construction and used a 100 hp Mercedes D.I engine.

Rumpler B.I depicted in Sanke card 271. Aircraft recognition, always a problem for the infantry, was in its infancy and the aircraft is will decorated with German national insignia to identify it for the ground troops.

Rumpler B.I approaching to land. In addition to the Fliegertruppe, the B.I was used by the German Navy and 31 were sold to the Austro-Hungarian Luftfahrtruppen where they served until at least August 1918.

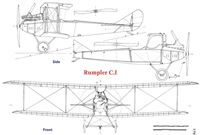

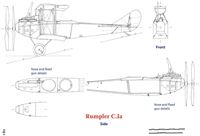

Rumpler C.I & C.Ia

The Rumpler C.I was an armed, two-seat general purpose reconnaissance airplane designed based on the lessons learned from the very first armed two-seaters from Albatros, Aviatik, and LVG, all of which were derivatives of earlier, unarmed two-seaters. Designed to carry guns, bombs, and wireless, the Rumpler C.I had good speed and maneuverability and very good climb. Coupled with its robust construction, its good performance and versatility quickly earned it a good reputation among the aircrew who flew it.

When it first flew in the summer of 1915, the Rumpler C.I was faster than the Fokker and Pfalz Eindecker fighters and had an equivalent climb rate. Idflieg ordered the first batch of aircraft in July 1915 and the C.I passed military acceptance testing in October. The first C.I aircraft arrived at the front in November-December 1915. Armed with both a fixed and a flexible machine gun and with performance exceeding the Eindeckers, the Rumpler C.I was an excellent combat aircraft for its time and lasted a long time at the front.

The Rumpler C.I had a wood and fabric airframe typical of the time and was powered by a 160 hp Mercedes D.III or a 150 hp Benz Bz.III. Hannover built the Rumpler C.Ia powered by the 180 hp Argus As.III; speed at low levels was improved slightly at the expense of reliability and high-altitude performance. The C.Ia was used primarily on the Eastern Front, where they were not generally faced with the latest fighter opposition, and gave good service.

Unlike similar aircraft, the C.I had a steel-tube framework integrated with the wood structure of the forward fuselage, making it stronger and more survivable in case of a crash. The robust, versatile C.I was used for a variety of experimental programs testing new wings and engines. The large, 220 hp Mercedes D.IV straight-eight was tested in the C.I, as was the first BMW.IIIa engine.

Rumpler C.I aircraft built under license for training were powered by a variety of engines. Aircraft built for training service seldom used the 160 hp Mercedes D.III because it was needed for fighters. Re-built 150 hp Benz Bz.III engines were installed along with the 175 hp Rapp Rp.IIIa, 180 hp Argus As.III, and 185 hp Conrad C.III(Nag). Trainers with the Conrad engine were built by Germania and designated C.Ic(Germ). As far as is known, the only license-built Rumpler C.I aircraft used in combat was the Hannover-built C.Ia. Manufacturers who built the C.I for training use were Markische, Germania, Hansa-Brandenburg, the Bayerische Rumpler-Werke (owned by Rumpler), and the Flugzeugwerke Albert Rinne. Details are in the production table.

Finally, it should be noted that the C.I airframe had such good qualities that it was used for the successful Rumpler 6B1 single-seat floatplane fighter. Despite being derived from a two-seat reconnaissance airplane, the 6B1 was as successful as the competing single-seat floatplane fighters derived from land-plane fighters.

Rumpler C.I Specifications

Engine: 160 hp Mercedes D.III

Wing: Span (Upper) 12.15 m

Span (Lower) 10.04 m

Chord (Upper) 1.75 m

Chord (Lower) 1.75 m

Gap 1.86 m

Area 35.7 m2

General: Length 7.85 m

Empty Weight 793 kg

Loaded Weight 1,333 kg

Maximum Speed: 152 kmh

Climb: 3000m 25 min

Rumpler C.I Production Orders

Date Qty Serials Notes

Jul. 1915 50 393-442/15

1915 4 1025-1066/15

1915 20 1588-1599/15 Other serials unk.

Oct. 1915 51 1836-1886/15

Dec. 1915 150 4515-4664/15

Mar. 1916 50 1125-1174/16

Mar. 1916 100 2600-2699/16

Sep.1916 50 Cancelled

Sep. 1916 200 4600-4699/16 Han. C.Ia

Oct. 1916 100 5400-5499/16 Mark.; trainers

Oct. 1916 100 6075-6174/16 Germ.; trainers

Oct. 1916 75 6500-6574/16 HaBra.; trainers

Jan. 1917 75 900-974/17 Han. C.Ia

Mar. 1917 200 2550-2749/17 Mark.; trainers

Apr. 1917 100 4100-4199/17 Ha-Bra.; trainers

May 1917 100 4900-4999/17 Germ.; trainers

May 1917 100 5475-5574/17 Han. C.Ia

Jul. 1917 200 2550-2749/17 Rinne; trainers

Sep. 1917 250 See Note 1 Mark.; trainers

Oct. 1917 100 14100-14199/17 Germ.; C.Ic tmrs.

Apr. 1918 150 3000-3149/18 Mark.; trainers

Jun. 1918 100 7050-7149/18 Bayru.; trainers

Jul. 1918 100 See Note 2 Li-Ho; cancelled

Oct. 1918 50 2550-2749/17 Germ.; trainers

Notes: 1. Known serials are 12820-13069/17. 2. Serial C.13074/18 from this order is known. 3. 2363 Rumpler C.I aircraft built; 463 by Rumpler, 375 by Hannover (Han.), 700 by Markishe (Mark.), 350 by Germania (Germ.), 175 by Hansa-Brandenburg (HaBra.), 100 by Bavarian Rumpler Works (Bayru.), 200 by Flugzeugwerke Rinne.

The Rumpler C.I was an armed, two-seat general purpose reconnaissance airplane designed based on the lessons learned from the very first armed two-seaters from Albatros, Aviatik, and LVG, all of which were derivatives of earlier, unarmed two-seaters. Designed to carry guns, bombs, and wireless, the Rumpler C.I had good speed and maneuverability and very good climb. Coupled with its robust construction, its good performance and versatility quickly earned it a good reputation among the aircrew who flew it.

When it first flew in the summer of 1915, the Rumpler C.I was faster than the Fokker and Pfalz Eindecker fighters and had an equivalent climb rate. Idflieg ordered the first batch of aircraft in July 1915 and the C.I passed military acceptance testing in October. The first C.I aircraft arrived at the front in November-December 1915. Armed with both a fixed and a flexible machine gun and with performance exceeding the Eindeckers, the Rumpler C.I was an excellent combat aircraft for its time and lasted a long time at the front.

The Rumpler C.I had a wood and fabric airframe typical of the time and was powered by a 160 hp Mercedes D.III or a 150 hp Benz Bz.III. Hannover built the Rumpler C.Ia powered by the 180 hp Argus As.III; speed at low levels was improved slightly at the expense of reliability and high-altitude performance. The C.Ia was used primarily on the Eastern Front, where they were not generally faced with the latest fighter opposition, and gave good service.

Unlike similar aircraft, the C.I had a steel-tube framework integrated with the wood structure of the forward fuselage, making it stronger and more survivable in case of a crash. The robust, versatile C.I was used for a variety of experimental programs testing new wings and engines. The large, 220 hp Mercedes D.IV straight-eight was tested in the C.I, as was the first BMW.IIIa engine.

Rumpler C.I aircraft built under license for training were powered by a variety of engines. Aircraft built for training service seldom used the 160 hp Mercedes D.III because it was needed for fighters. Re-built 150 hp Benz Bz.III engines were installed along with the 175 hp Rapp Rp.IIIa, 180 hp Argus As.III, and 185 hp Conrad C.III(Nag). Trainers with the Conrad engine were built by Germania and designated C.Ic(Germ). As far as is known, the only license-built Rumpler C.I aircraft used in combat was the Hannover-built C.Ia. Manufacturers who built the C.I for training use were Markische, Germania, Hansa-Brandenburg, the Bayerische Rumpler-Werke (owned by Rumpler), and the Flugzeugwerke Albert Rinne. Details are in the production table.

Finally, it should be noted that the C.I airframe had such good qualities that it was used for the successful Rumpler 6B1 single-seat floatplane fighter. Despite being derived from a two-seat reconnaissance airplane, the 6B1 was as successful as the competing single-seat floatplane fighters derived from land-plane fighters.

Rumpler C.I Specifications

Engine: 160 hp Mercedes D.III

Wing: Span (Upper) 12.15 m

Span (Lower) 10.04 m

Chord (Upper) 1.75 m

Chord (Lower) 1.75 m

Gap 1.86 m

Area 35.7 m2

General: Length 7.85 m

Empty Weight 793 kg

Loaded Weight 1,333 kg

Maximum Speed: 152 kmh

Climb: 3000m 25 min

Rumpler C.I Production Orders

Date Qty Serials Notes

Jul. 1915 50 393-442/15

1915 4 1025-1066/15

1915 20 1588-1599/15 Other serials unk.

Oct. 1915 51 1836-1886/15

Dec. 1915 150 4515-4664/15

Mar. 1916 50 1125-1174/16

Mar. 1916 100 2600-2699/16

Sep.1916 50 Cancelled

Sep. 1916 200 4600-4699/16 Han. C.Ia

Oct. 1916 100 5400-5499/16 Mark.; trainers

Oct. 1916 100 6075-6174/16 Germ.; trainers

Oct. 1916 75 6500-6574/16 HaBra.; trainers

Jan. 1917 75 900-974/17 Han. C.Ia

Mar. 1917 200 2550-2749/17 Mark.; trainers

Apr. 1917 100 4100-4199/17 Ha-Bra.; trainers

May 1917 100 4900-4999/17 Germ.; trainers

May 1917 100 5475-5574/17 Han. C.Ia

Jul. 1917 200 2550-2749/17 Rinne; trainers

Sep. 1917 250 See Note 1 Mark.; trainers

Oct. 1917 100 14100-14199/17 Germ.; C.Ic tmrs.

Apr. 1918 150 3000-3149/18 Mark.; trainers

Jun. 1918 100 7050-7149/18 Bayru.; trainers

Jul. 1918 100 See Note 2 Li-Ho; cancelled

Oct. 1918 50 2550-2749/17 Germ.; trainers

Notes: 1. Known serials are 12820-13069/17. 2. Serial C.13074/18 from this order is known. 3. 2363 Rumpler C.I aircraft built; 463 by Rumpler, 375 by Hannover (Han.), 700 by Markishe (Mark.), 350 by Germania (Germ.), 175 by Hansa-Brandenburg (HaBra.), 100 by Bavarian Rumpler Works (Bayru.), 200 by Flugzeugwerke Rinne.

The Rumpler 5A1 was the prototype Rumpler C.I. The slightly modified production Rumpler C.I had the factory designation Rumpler model 5A2. The rudder and fin of the production aircraft was enlarged slightly from the 5A1. The aircraft is seen in its initial form without markings at the time of initial test flights in June 1915 in front of the Rumpler factory at Johannisthal.

The Rumpler C.I prototype after national insignia were applied but before the pilot's fixed, synchronized gun was fitted. A spherical gravity tank has been added below the center section.

The Rumpler C.I prototype before the pilot's fixed, synchronized gun was fitted. The spherical gravity tank added below the center section is clearly visible. The claw brake is fitted to the axle.

The Rumpler C.I prototype after national insignia were applied but before the pilot's fixed, synchronized gun was fitted. The gunner is demonstrating his wide field of fire with a dummy wooden gun.

The Rumpler C.I prototype before the pilot's fixed, synchronized gun was fitted. The spherical gravity tank added below the center section is clearly visible. The claw brake is fitted to the axle.

Rumpler C.I 53/15 was a very early production aircraft, powered by a 160hp Mercedes D III. Armed with a fixed, pilot-aimed 7.9mm Spandau, along with the observer's 7.92mm Parabellum, the Rumpler C I was considered by many to be the best and most reliable of all C types produced. Top level speed of the machine was 94mph at sea level, while the service ceiling was around 16,600 feet. Normal range was given as 336 miles.

Rumpler C.I 1851/15 was from the fourth production batch. These were the first Rumpler C.I aircraft built with a rotating turret for the gunner, something that all subsequent aircraft featured.

Rumpler C.I 4601/15 in pristine finish. The finish is not original so it has been recovered, probably after repair.

Early production models of the Rumpler C.I were powered by the 160 hp Mercedes D.III, and immediately established themselves as reliable airplanes with good performance and handling qualities. Some later production C.Is had a 150 hp Benz Bz.III or 180 hp Argus As.III.The C.I was an excellent general purpose C-type that was popular with its crews.

French soldiers inspect this captured Rumpler CI. By 1916 the type was an important general-purpose aircraft and was well liked by its crews. When eventually outclassed on the Western Front it went on to serve in other theatres.

A Rumpler C.I in training service in 1918 (per the national insignia style) is a backdrop for a unit photograph.

A Rumpler C.I in training service in 1918 (per the national insignia style) is a backdrop for a unit photograph.

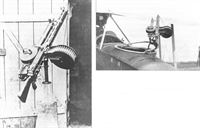

This closeup of a Rumpler C.I with cowling panel removed shows the pilot's fixed machine gun. The "H" with arrow added to the photo points to the 'Hebei', the lever arm of the synchronizing mechanism.

Rumpler C.Ia(Han) showing the distinctive built-up fuselage for the observer's gun ring unique to Hannover.

Rumpler C.Ia(Han) with the raised fuselage around the observer's gun ring unique to Hannover-built aircraft.The only license-built C.I aircraft used in combat were the C.Ia aircraft built by Hannover. All other license-built aircraft were intended as trainers.

Rumpler CI(Mark) 3042/18 was built as a trainer. Here is is undergoing acceptance flight testing at Adlershof in 1918.

The desire to create 'low observable' or 'stealthy' aircraft difficult to detect is not new. Here a Rumpler C.I has been covered by transparent Cellon in an experiment to make it more difficult to see. Other types involved in these trials included the Fokker E.III and Linke-Hofmann R.I. However, Cellon proved to have insurmountable disadvantages. First, it was shiny, making the aircraft more visible in situations where bright sunlight illuminated it. Second, Cellon was brittle and tore easily, and it sagged when it absorbed water, ruining the aircraft's aerodynamic qualities. An interesting series of experiments, Cellon covering was quickly abandoned.

The Rumpler C.I served with the Latvian air service postwar. The finish was German camouflage-printed fabric and the Latvian national markings consisted of a red Swastika over a white background.

LVG C.II 2135/15 is at left foreground and three late-production Rumpler C.III aircraft rest in the right foreground on 16 April 1917. Interestingly, there are no insignia on the rudders of the C.III aircraft. A Rumpler C.I is in the center background with another LVG C.II at right background.

Well-known propaganda photo of a Rumpler C.I (upper right) flying over the Pyramids in Egypt. The photo of the Pyramids was actually taken by a Rumpler C.I but it could not take a photo of itself, so the C.I in the photo was added for propaganda value.

The Rumpler C.I was a popular aircraft and is certainly a candidate for having the most air-to-air photographs taken of it of any WWI German airplane.

This Rumpler C.I was retired from flight duties and converted into a ground-based gunnery trainer. It is mounted on a complex platform allowing it to move for greater realism while the gunner aims at targets pulled past the trainer. A target, the silhouette of a Rumpler, is visible in the background.

Rumpler C.Ia(Han) 4645/16 after a landing incident. It has the distinctive built-up decking for the gun ring and camouflage of Hannover-built aircraft.

Rumpler Bombers

Rumpler produced a comparatively small number of bomber designs that saw modest production in keeping with their performance. In addition to at least three prototypes, 58 Rumpler production bombers of all types were built as detailed in the adjacent table.

With limited engineering resources, Rumpler eventually abandoned bomber design in favor of more critical fighters and reconnaissance airplanes.

Rumpler Bomber Production

Type Quantity Serials

G.I 4 15-18/15

G.II 24 106-117/15 &. 119-130/15

G.III 30 300-329/16. See Note.

Note: Idflieg ordered 50 Rumpler G.III bombers but only 30 were built.

Rumpler 4A15

In July 1914 Rumpler was among several manufacturers asked to develop a Kampfflugzeuge, a battleplane or aerial cruiser. The aircraft was to have a crew of two or three with a flexible gun for the observer/gunner mounted in the front cockpit, and was to have at least 200 hp.

Rumpler's response was the 4A15, a twin-engine biplane of conventional wood, wire, and fabric construction powered by 150 hp Benz Bz.III engines mounted in pusher configuration. Each engine was mounted on the lower wing and enclosed in a nacelle housing a frontal Windhoff radiator and a 310 liter fuel tank. A gravity tank was installed above each engine. The 4A15 had a span of 18.75 m and a length of 11.8 m. The simple landing gear included a pair of wheels under each engine and another pair under the nose to prevent nose-overs on landing.

The 4A15 first flew in March 1915 and achieved a maximum speed of 135 km/h at sea level. During informal flight demonstrations the aircraft carried ten people to 3,200 m on March 15th and then carried 16 people to 1,800 m. On 22 March the aircraft reached 2,300 m in 55 minutes while carrying 12 people. However, while flying to Munich on April 10 the 4A15 was forced to make an emergency landing and was damaged. On April 17, 1915 it was destroyed following a carburetor fire. However, during its brief life the 4A15 set the basic configuration for all Rumpler bombers that followed.

Rumpler G.I

Rumpler continued bomber development with the 5A15. Based on the 4A15, the 5A15 used the same basic structure and engines but had a number of refinements. The wing span was increased slightly, the shape of the vertical tail surfaces was revised, and a single gravity tank under the top wing replaced the two separate gravity tanks over the engines. The gunner in the front cockpit was given a windshield and the rear crew member now had a flexible gun.

The 5A15 first flew on September 4, 1915 and demonstrated acceptable performance, although flight testing revealed a number of improvements were needed. The test pilot, probably Friedrich Budig, then chief test pilot at Rumpler, complained that the fuel system was too complicated and the gravity tank was the sole feed to the carburetors, creating a single point of failure. The aircraft was also too tail heavy and the pusher propellers were subject to damage from debris thrown up by the landing gear. Inadequate clearance (4 cm) between the fuselage and the propeller arc sometimes caused the propellers to hit the screen protecting the rear gunner from the propeller arc.

The 5A15 passed its acceptance flight on September 16, 1915, and Idflieg ordered it into limited production as the Rumpler G.I, only four aircraft being built. Photographs show the production aircraft had an enlarged rudder for better directional control after an engine failure. The very small number ordered indicates that the aircraft were primarily intended for operational evaluation. One aircraft, G.16/15, was delivered to Kampgeschwader der Obersten Heeresleitung 1 (Kagohl 1) for operational evaluation, where it was flown for a time by Leutnant Ray, while two others, G.17/15 and G.18/15, served briefly that year with Brieftauben Abteilung Metz, or BAM.

Rumpler G.l Specifications

Engines: 2 x 150 hp Benz Bz.III

Wing: Span 19.3 m

Area 78.68 m

General: Length 11.8 m

Height 4.0 m

Empty Weight 1,998 kg

Loaded Weight 2,938 kg

Maximum Speed: 145 kmh

Climb: 800m 7 min

2000m 21 min

4000m 120 min

Service Ceiling: 4000 m

Range: 600 km

Armament: 1 flexible MG & 150-200 kg of bombs

Rumpler G.II

In November 1915 Idflieg ordered 24 improved aircraft as the Rumpler G.II. The most important change was the use of more powerful, 220 hp Benz Bz.IV engines for improved speed, climb, and ceiling. The G.I airframe was used with minor modifications, but flight testing soon revealed the need for additional modifications for improved flying qualities. The prototype G.II, Rumpler internal designation 5A16, was tail heavy and insufficiently stable. Testing revealed the need for larger propellers to efficiently absorb the greater engine power, so propellers of 3.1 m diameter were fitted and the fuselage was narrowed slightly to provide sufficient clearance.

Rumpler chief test pilot Friedrich Budig determined that modifications to the lower wing near the propellers were needed, and on May 27, 1916 large cut-outs were made in the lower wing in front of the propellers on the second production aircraft. This modification greatly reduced tail heaviness as determined by Budig during a successful test flight on May 30.

Rumpler G.II 117/15, the last aircraft of the first production series, was fitted with more powerful 260 hp Mercedes D.IVa engines and larger propellers of 3.17 m diameter. Idflieg accepted this modified aircraft and it went on to serve with Kagohl 2 on the Eastern Front in the summer of 1916. No other G.II aircraft used this engine, but it was a harbinger of things to come in the Rumpler G.III.

The Rumpler G.II saw much of its service with Kagohl 2. Originally formed from the Brieftauben Abteilung Metz, or BAM, in December 1915, Kagohl 2 had six Kampfstaffeln, Kastas 7-12. Five of these had single-engine C-type aircraft, but one was equipped with the Rumpler G.II and AEG G.III. Kagohl 2 was transferred to the Eastern Front in July 1916 and was eventually stationed at Lasnaja aerodrome. Kagohl 1, originally formed from the Brieftaubenabteilung Ostend, or BAO,was also transferred to the Eastern Front in June 1916, and had some Rumpler G.II aircraft along with other G-types. In September 1916 Kagohl 1 was transferred to northern Bulgaria where it flew a number of bombing missions against Romanian troops. Kagohl 2 was transferred back to the Western Front in October 1916, followed by Kagohl 1 in May 1917.

The Rumpler G.II bombers were better armed than the C-types and on the Eastern Front were used as long-range reconnaissance aircraft and as escorts for the smaller C-types on bombing raids.

Rumpler G.II Specifications

Engines: 2 x 220 hp Benz Bz.IV

Wing: Span 19.3 m

General: Length 11.8 m

Height 4.0 m

Empty Weight 1,990 kg

Loaded Weight 2,990 kg

Maximum Speed: 164 kmh

Armament: 2 flexible MGs & bombs

Rumpler G.III

The Rumpler G.II had proven itself moderately successful and Idflieg placed an order for the proposed Rumpler G.III in September 1916. Retaining the basic size and configuration of the earlier G.II, the G.III was a new design. Although wingspan was the same as the earlier types, wing area was reduced by a smaller lower wing. The engine nacelles were more streamlined and more powerful 260 hp Mercedes D.IVa engines were fitted in place of the 220 hp Benz engines of the G.II. To reduce the danger of fire the fuel tanks were now mounted in the fuselage instead of in the nacelles. Unfortunately, the weight of the new aircraft increased substantially due to increases in the empty weight and also the designed payload.

Flight testing of the new prototype, factory designation 6G2, began in December 1916 and quickly revealed unsafe flying qualities. Like the earlier designs, the G.III prototype was tail heavy in flight. To solve this problem the horizontal stabilizer was raised and the fuselage near the plane of the propellers was modified to improve airflow, and these changes greatly alleviated the tail-heaviness. Test pilot Friedrich Budig stated the revised G.III was more stable and had better flying qualities than the G.II. However, adding the rear gunner's gun and ammunition again caused tail-heaviness, and the upper wings had to be moved rearward to restore pitch stability and trim.

The G.III that arrived at the front in December 1916 was the aircraft assigned to Kagohl 2, which had used the earlier G.II. Some G.III bombers served into at least March 1918 with Kampfstaffel 9 of Kagohl 2.

The final Rumpler bomber prototype, factory designation 6G4, had increased wing span and tractor-mounted 4-bladed propellers. The first test flight on 18 February 1918 indicated marginal flight characteristics when the aircraft swung to the right on takeoff and the pilot, Budig, was barely able to correct it. With extensive modifications necessary to improve its poor flying qualities and higher priority programs underway, further bomber development was abandoned.

Rumpler G.III Specifications

Engines: 2 x 260 hp Mercedes D.IVa

Wing: Span 19.3 m

Area 78.68 m2

General: Length 12.0 m

Height 4.5 m

Empty Weight 2,365 kg

Loaded Weight 3,620 kg

Maximum Speed: 150 kmh

Climb: 3000m 22 min

Service Ceiling: 5000 m

Range: 660 km

Armament: 2 flexible MGs St 225 kg of bombs

Rumpler produced a comparatively small number of bomber designs that saw modest production in keeping with their performance. In addition to at least three prototypes, 58 Rumpler production bombers of all types were built as detailed in the adjacent table.

With limited engineering resources, Rumpler eventually abandoned bomber design in favor of more critical fighters and reconnaissance airplanes.

Rumpler Bomber Production

Type Quantity Serials

G.I 4 15-18/15

G.II 24 106-117/15 &. 119-130/15

G.III 30 300-329/16. See Note.

Note: Idflieg ordered 50 Rumpler G.III bombers but only 30 were built.

Rumpler 4A15

In July 1914 Rumpler was among several manufacturers asked to develop a Kampfflugzeuge, a battleplane or aerial cruiser. The aircraft was to have a crew of two or three with a flexible gun for the observer/gunner mounted in the front cockpit, and was to have at least 200 hp.

Rumpler's response was the 4A15, a twin-engine biplane of conventional wood, wire, and fabric construction powered by 150 hp Benz Bz.III engines mounted in pusher configuration. Each engine was mounted on the lower wing and enclosed in a nacelle housing a frontal Windhoff radiator and a 310 liter fuel tank. A gravity tank was installed above each engine. The 4A15 had a span of 18.75 m and a length of 11.8 m. The simple landing gear included a pair of wheels under each engine and another pair under the nose to prevent nose-overs on landing.

The 4A15 first flew in March 1915 and achieved a maximum speed of 135 km/h at sea level. During informal flight demonstrations the aircraft carried ten people to 3,200 m on March 15th and then carried 16 people to 1,800 m. On 22 March the aircraft reached 2,300 m in 55 minutes while carrying 12 people. However, while flying to Munich on April 10 the 4A15 was forced to make an emergency landing and was damaged. On April 17, 1915 it was destroyed following a carburetor fire. However, during its brief life the 4A15 set the basic configuration for all Rumpler bombers that followed.

Rumpler G.I

Rumpler continued bomber development with the 5A15. Based on the 4A15, the 5A15 used the same basic structure and engines but had a number of refinements. The wing span was increased slightly, the shape of the vertical tail surfaces was revised, and a single gravity tank under the top wing replaced the two separate gravity tanks over the engines. The gunner in the front cockpit was given a windshield and the rear crew member now had a flexible gun.

The 5A15 first flew on September 4, 1915 and demonstrated acceptable performance, although flight testing revealed a number of improvements were needed. The test pilot, probably Friedrich Budig, then chief test pilot at Rumpler, complained that the fuel system was too complicated and the gravity tank was the sole feed to the carburetors, creating a single point of failure. The aircraft was also too tail heavy and the pusher propellers were subject to damage from debris thrown up by the landing gear. Inadequate clearance (4 cm) between the fuselage and the propeller arc sometimes caused the propellers to hit the screen protecting the rear gunner from the propeller arc.

The 5A15 passed its acceptance flight on September 16, 1915, and Idflieg ordered it into limited production as the Rumpler G.I, only four aircraft being built. Photographs show the production aircraft had an enlarged rudder for better directional control after an engine failure. The very small number ordered indicates that the aircraft were primarily intended for operational evaluation. One aircraft, G.16/15, was delivered to Kampgeschwader der Obersten Heeresleitung 1 (Kagohl 1) for operational evaluation, where it was flown for a time by Leutnant Ray, while two others, G.17/15 and G.18/15, served briefly that year with Brieftauben Abteilung Metz, or BAM.

Rumpler G.l Specifications

Engines: 2 x 150 hp Benz Bz.III

Wing: Span 19.3 m

Area 78.68 m

General: Length 11.8 m

Height 4.0 m

Empty Weight 1,998 kg

Loaded Weight 2,938 kg

Maximum Speed: 145 kmh

Climb: 800m 7 min

2000m 21 min

4000m 120 min

Service Ceiling: 4000 m

Range: 600 km

Armament: 1 flexible MG & 150-200 kg of bombs

Rumpler G.II

In November 1915 Idflieg ordered 24 improved aircraft as the Rumpler G.II. The most important change was the use of more powerful, 220 hp Benz Bz.IV engines for improved speed, climb, and ceiling. The G.I airframe was used with minor modifications, but flight testing soon revealed the need for additional modifications for improved flying qualities. The prototype G.II, Rumpler internal designation 5A16, was tail heavy and insufficiently stable. Testing revealed the need for larger propellers to efficiently absorb the greater engine power, so propellers of 3.1 m diameter were fitted and the fuselage was narrowed slightly to provide sufficient clearance.

Rumpler chief test pilot Friedrich Budig determined that modifications to the lower wing near the propellers were needed, and on May 27, 1916 large cut-outs were made in the lower wing in front of the propellers on the second production aircraft. This modification greatly reduced tail heaviness as determined by Budig during a successful test flight on May 30.

Rumpler G.II 117/15, the last aircraft of the first production series, was fitted with more powerful 260 hp Mercedes D.IVa engines and larger propellers of 3.17 m diameter. Idflieg accepted this modified aircraft and it went on to serve with Kagohl 2 on the Eastern Front in the summer of 1916. No other G.II aircraft used this engine, but it was a harbinger of things to come in the Rumpler G.III.

The Rumpler G.II saw much of its service with Kagohl 2. Originally formed from the Brieftauben Abteilung Metz, or BAM, in December 1915, Kagohl 2 had six Kampfstaffeln, Kastas 7-12. Five of these had single-engine C-type aircraft, but one was equipped with the Rumpler G.II and AEG G.III. Kagohl 2 was transferred to the Eastern Front in July 1916 and was eventually stationed at Lasnaja aerodrome. Kagohl 1, originally formed from the Brieftaubenabteilung Ostend, or BAO,was also transferred to the Eastern Front in June 1916, and had some Rumpler G.II aircraft along with other G-types. In September 1916 Kagohl 1 was transferred to northern Bulgaria where it flew a number of bombing missions against Romanian troops. Kagohl 2 was transferred back to the Western Front in October 1916, followed by Kagohl 1 in May 1917.

The Rumpler G.II bombers were better armed than the C-types and on the Eastern Front were used as long-range reconnaissance aircraft and as escorts for the smaller C-types on bombing raids.

Rumpler G.II Specifications

Engines: 2 x 220 hp Benz Bz.IV

Wing: Span 19.3 m

General: Length 11.8 m

Height 4.0 m

Empty Weight 1,990 kg

Loaded Weight 2,990 kg

Maximum Speed: 164 kmh

Armament: 2 flexible MGs & bombs

Rumpler G.III

The Rumpler G.II had proven itself moderately successful and Idflieg placed an order for the proposed Rumpler G.III in September 1916. Retaining the basic size and configuration of the earlier G.II, the G.III was a new design. Although wingspan was the same as the earlier types, wing area was reduced by a smaller lower wing. The engine nacelles were more streamlined and more powerful 260 hp Mercedes D.IVa engines were fitted in place of the 220 hp Benz engines of the G.II. To reduce the danger of fire the fuel tanks were now mounted in the fuselage instead of in the nacelles. Unfortunately, the weight of the new aircraft increased substantially due to increases in the empty weight and also the designed payload.

Flight testing of the new prototype, factory designation 6G2, began in December 1916 and quickly revealed unsafe flying qualities. Like the earlier designs, the G.III prototype was tail heavy in flight. To solve this problem the horizontal stabilizer was raised and the fuselage near the plane of the propellers was modified to improve airflow, and these changes greatly alleviated the tail-heaviness. Test pilot Friedrich Budig stated the revised G.III was more stable and had better flying qualities than the G.II. However, adding the rear gunner's gun and ammunition again caused tail-heaviness, and the upper wings had to be moved rearward to restore pitch stability and trim.

The G.III that arrived at the front in December 1916 was the aircraft assigned to Kagohl 2, which had used the earlier G.II. Some G.III bombers served into at least March 1918 with Kampfstaffel 9 of Kagohl 2.

The final Rumpler bomber prototype, factory designation 6G4, had increased wing span and tractor-mounted 4-bladed propellers. The first test flight on 18 February 1918 indicated marginal flight characteristics when the aircraft swung to the right on takeoff and the pilot, Budig, was barely able to correct it. With extensive modifications necessary to improve its poor flying qualities and higher priority programs underway, further bomber development was abandoned.

Rumpler G.III Specifications

Engines: 2 x 260 hp Mercedes D.IVa

Wing: Span 19.3 m

Area 78.68 m2

General: Length 12.0 m

Height 4.5 m

Empty Weight 2,365 kg

Loaded Weight 3,620 kg

Maximum Speed: 150 kmh

Climb: 3000m 22 min

Service Ceiling: 5000 m

Range: 660 km

Armament: 2 flexible MGs St 225 kg of bombs

Rumpler G.II G.109/15 assigned to Kagohl 2, summer of 1916. The black circles were identification markings painted at the unit level.

Rumpler G.III G311/16 assigned to Kasta 9, summer of 1917. The black circles with white star and black/ white wheel covers were unit markings.

The Rumpler 4A15 was the first Rumpler bomber design, and all subsequent Rumpler bombers followed its general configuration of pusher engines and simple landing gear with nose wheels to prevent nose-overs on landing. The propellers were mounted on short extension shafts.

The Rumpler 4A15 was in response to an Idflieg request for a Kampfflugzeuge, or battleplane. Powered by two 150 hp Benz Bz.III engines mounted as pushers, it set the basic configuration for all subsequent Rumpler bombers.

The Rumpler 4A15 was the first Rumpler bomber design, and all subsequent Rumpler bombers followed its general configuration of pusher engines and simple landing gear with nose wheels to prevent nose-overs on landing. The fuel tank below the engine is clearly visible. The propellers were mounted on short extension shafts.

This photograph shows the Rumpler G.I with the first design of fin and rudder, the most visible difference between the Rumpler G.I, military designation for 5A15, and 4A15. A gravity tank was also installed just below the upper wing; the main fuel tank for the starboard engine is visible mounted beneath the engine and forward of it. The fuel tank was located near the aircraft center of gravity so burning off fuel would not adversely impact the type's pitch stability.

This photograph shows the Rumpler G.I engine installation in more detail. The under-wing gravity tank and main fuel tank for the starboard engine are clearly visible. The frontal radiator was large and complex.

Rumpler entered the twin-engine bomber business with the Rumpler G.I. Nose wheels protected against nose-overs on soft fields. The G.I used 150 hp Benz Bz.III engines, but only four were built before production was moved to the more powerful G.II using the same airframe.

In this front quarter view the most visible difference between the Rumpler G.I and A415 is the windshield provided for the front gunner in addition to the gravity tank installed just below the upper wing. The front gunner's flexible machine gun is also visible.

In this front quarter view the most visible difference between the Rumpler G.I and A415 is the windshield provided for the front gunner in addition to the gravity tank installed just below the upper wing. The front gunner's flexible machine gun is also visible.

This front quarter view of Rumpler G.I 16/15 shows the overall workman-like design and construction.The tents in the background indicate this is an operational aircraft at its unit.

Rumpler G.I 16/15, the second of four production machines. The most noticeable difference between this aircraft and the first G.I is the enlarged rudder with large aerodynamic balance for improved directional control with one engine out. The larger rudder was retrofitted to G.I 15/15. The engine cowlings were well streamlined. A black and white measurement bar is included in two photographs to enable measurements to be scaled from the photos.

Rumpler G.I 15/15 is shown moments after lifting off during take-off. This view confirms that the enlarged rudder was retrofitted to this aircraft.

The Rumpler G.II was developed from the Rumpler G.I by upgrading the engines.This G.II, 117/15, the last aircraft of the first production batch of G.II bombers, is virtually indistinguishable from the G.I other than the barely visible cutout of the lower wing trailing edge. This is also the one G.II modified to have 260 h.p. Mercedes D.IVa engines, but the photo is not clear enough to show which engine type is fitted.

Rumpler G.II G.122/15 ready for a bombing mission; the bombs are already loaded under the fuselage. Only standard factory markings and insignia are visible.The snowy scene was probably at KG2 on the Eastern Front.

The most visible differences between Rumpler G.II, 117/15 and the earlier Rumpler G.I are the cutouts in the lower wing trailing edge and the white backgrounds for the iron cross insignia.The screens to protect the rear gunner from the propellers are also visible.

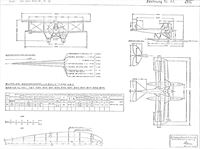

Rumpler G.II (5A16) (1916)

In contrast to earlier Rumpler bombers with overall light finish, Rumpler G.II G.129/15, the next to last production G.II, carries an interesting camouflage scheme, with the camouflage on the engine nacelles painted a different pattern than the fuselage. Despite the distinctive camouflage, only standard factory markings and insignia are visible. Because the factory serial number is clearly visible, the camouflage on wings and fuselage was probably painted at the factory. The straps for securing the bombs under the fuselage are clearly visible, as is the lower wing trailing edge cutout. The summer scene was probably taken at KG2 on the Eastern Front.

The Rumpler G.II was based on the Rumpler G.I airframe, but used more powerful 220 hp Benz Bz.IV engines. Performance and bomb load were improved, and 24 were built. The Rumpler G.II served on both the Western and Macedonian Fronts as a bomber. In Macedonia it was also used to escort C-types during day bombing raids.

In contrast to earlier Rumpler bombers with overall light finish, Rumpler G.II G.129/15, the next to last production G.II, carries an interesting camouflage scheme, with the camouflage on the engine nacelles painted a different pattern than the fuselage. Despite the distinctive camouflage, only standard factory markings and insignia are visible. Because the factory serial number is clearly visible, the camouflage on wings and fuselage was probably painted at the factory. The straps for securing the bombs under the fuselage are clearly visible, as is the lower wing trailing edge cutout. The summer scene was probably taken at KG2 on the Eastern Front.

The Rumpler G.II was based on the Rumpler G.I airframe, but used more powerful 220 hp Benz Bz.IV engines. Performance and bomb load were improved, and 24 were built. The Rumpler G.II served on both the Western and Macedonian Fronts as a bomber. In Macedonia it was also used to escort C-types during day bombing raids.

This close-up view of Rumpler G.II G.129/15 shows its interesting camouflage scheme and engine nacelles in more detail. The camouflage appears to be sprayed on the fuselage and brush-painted on the nacelles, indicating the nacelle camouflage may have been applied at the unit. The screens to protect the gunner from the propellers are clearly shown. Although not clear, there appears to be segmented camouflage on the bottom of the upper wing.

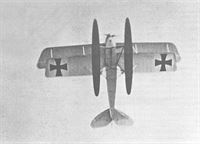

Rumpler G.II G.l 07/15 is shown in flight over the Eastern Front while serving with KG2. The light overall finish still contrasts somewhat with the white backgrounds for the iron cross insignia. Both guns are visible as is the slight sweep-back of the wings.

Because of their heavy defensive armament, the Kagohl's first twin-engined G types of aircraft were used singly for reconnaissance duties, and when accompanying a number of smaller two-seaters on a bombing raid the inclusion of a G type guaranteed that enemy fighters would concentrate on the big machine, leaving the main bomb-carrying force almost unmolested. But a hot reception awaited the attackers. This Rumpler G II (107/15) is seen over the Eastern Front, operating with Kagohl II from Kowel aerodrome in 1916.

Because of their heavy defensive armament, the Kagohl's first twin-engined G types of aircraft were used singly for reconnaissance duties, and when accompanying a number of smaller two-seaters on a bombing raid the inclusion of a G type guaranteed that enemy fighters would concentrate on the big machine, leaving the main bomb-carrying force almost unmolested. But a hot reception awaited the attackers. This Rumpler G II (107/15) is seen over the Eastern Front, operating with Kagohl II from Kowel aerodrome in 1916.

An unknown Rumpler G is shown in the Rumpler factory. In contrast to all available known G.I photographs, this aircraft is in overall dark finish with light engine nacelles typical of the G.II, making one think this was a production G.II. There appears to be a lower wing trailing edge cutout characteristic of the G.II series but the angle and quality of the photo preclude positive verification.

A Rumpler G.II in service with BAM (Brieftauben Abteilung Metz). Standing in the pilot's cockpit is Hptm. Fritz Prestien; the officer manning the gun is an observer named von Hachenburg. At the far right is Lt. Franz Ray, who would go on to score 17 confirmed victories as a fighter pilot. Hptm. Paul Backhaus is 3rd from right.

The Rumpler G.II was developed from the Rumpler G.I by replacing the 150 hp Benz Bz.III engines of the G.I with more powerful 220 hp Benz Bz.IV engines. This early G.II, possibly the first G.II airframe, is virtually indistinguishable from the G.I.

The more powerful Rumpler G.II was much more difficult to fly than the G.I. On 27 May 1916 large cutouts were made in each lower wing beneath the propellers on Rumpler G.II 107/15, the second G.II, as shown here. On 30 May Rumpler test pilot Friedrich Budig successfully flew this aircraft, and all subsequent G.II aircraft featured this cutout.

Then Unteroffizier Gustav Seitz poses in front of Rumpler G.II G.110/15 of Kampfstaffel 9 of KG2 at Kowel after receiving the Iron Cross 2nd Class. Again the radiators are distinctly different than those fitted to most other Rumpler G.II bombers.

Rumpler G.II G.109/15 of KG2 damaged at Lasnaja, one of two fields KG2 is known to have used on the Eastern Front, where KG2 served from mid-July to October 1916. The black circle marking is distinctive. The radiators are very different than those fitted to most other Rumpler G.II bombers, but the reason for this modification is unknown.

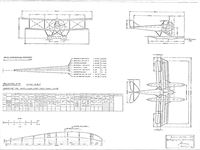

Rumpler G.III (6G2) (1916/17)

This Rumpler G.III shows its camouflage to advantage. The upper surfaces appear to be sprayed in two colors while the rudder is painted a single dark color and undersurfaces, struts, nacelles, and wheel covers appear to be in a single light shade. Propeller spinners are fitted, showing attention to streamlining details.

This Rumpler G.III shows its camouflage to advantage. The upper surfaces appear to be sprayed in two colors while the rudder is painted a single dark color and undersurfaces, struts, nacelles, and wheel covers appear to be in a single light shade. Propeller spinners are fitted, showing attention to streamlining details.

Rumpler G.III G.304/16, the fifth G.III aircraft, is shown here on a rainy day at the Rumpler factory. The two-color factory camouflage with lighter engine nacelles and undersurfaces is clearly shown.

Rumpler G.III, perhaps G.304/16? The photo looks like it could be from the same series as the other two on this page.

This front view of a Rumpler G.III emphasizes its clean lines with great attention to streamlining, a Rumpler hallmark.

This front view of a Rumpler G.III in a hangar shows a diamond insignia on the nose, which was a unit or personal marking.

This G.III is shown under construction at the factory. Although the photo quality is poor, the revised engine nacelles that now were raised above the wing like the Gotha G.V are clearly visible.

This photograph of Rumpler G.III G.311/16 of Bogohl 2 is especially interesting because, unlike most G.III photos, it shows unit markings on the nose and the wheel covers are painted half dark and half light; black and white? The aircraft is loaded for a bombing mission with P.u.W. bombs under the fuselage along with a square Kastenbombe for blast effect.

The Rumpler G.III was a new design. Its 260 hp Mercedes D.IVa engines were mounted in nacelles above the wing. Thirty G.III bombers were built. Rumpler started designing a G.IV but its engineering resources were stretched too thin designing fighters and reconnaissance airplanes, and Rumpler dropped out of bomber construction.

The Rumpler G.III was a new design. Its 260 hp Mercedes D.IVa engines were mounted in nacelles above the wing. Thirty G.III bombers were built. Rumpler started designing a G.IV but its engineering resources were stretched too thin designing fighters and reconnaissance airplanes, and Rumpler dropped out of bomber construction.

This front quarter view of a Rumpler G.III apparently at an operational unit shows its camouflage and clean lines to advantage. Interestingly, the rudder appears to be in two colors like the rest of the upper surfaces. The photo gives the impression of being of the same aircraft as the photo below, except the rudder appears to be in a single dark color. Are these two different aircraft or is this a trick of the light?

This rear quarter view of a Rumpler G.III apparently at an operational unit shows that the propeller spinners were not fitted. The rear gunner's gun is fitted and his cockpit appears very roomy.

This over-exposed view of a Rumpler G.III in flight is still interesting. The rudder and horn balance appear somewhat larger than that of the G.II and the lines are cleaner than the competing Gotha bombers.The nose landing gear used in all Rumpler bombers helped reduce the likelihood of a landing accident.

This photo taken from the front gunner's cockpit shows Rumpler test pilot Friedrich Budig (at right) flying a G.III. Only the pilot had a windscreen.

The front gunner's cockpit of the Rumpler G.III appears much more compact than the rear gunner's position despite housing a lot of equipment.

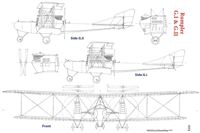

Rumpler 6A2

The single-bay 6A2 was designed as a two-seat fighter. Powered by a 160 hp Mercedes D.III, its first test flight in January 1916 revealed problematic handling qualities, but extensive experimentation and modification finally gave the 6A2 'excellent flight characteristics' according to Friedrich Budig. Unfortunately, climb rate was less than the C.I reconnaissance airplane and the wings were too 'elastic', so the X-struts were replaced with parallel struts. The 220 hp Mercedes D.IV straight-eight engine was also tried and gave very good climb rate but vibration was excessive. Records are ambiguous about whether the 160 hp Mercedes D.III was re-installed. Both flight testing and calculations indicated the 6A2 would not meet its requirements, and it was abandoned in favor of the enlarged, two-bay 6A5 prototype that became the C.III of otherwise similar appearance. The intermediate 6A3 and 6A4 were designed but probably not built.

Rumpler 6A2 Specifications

Engine: 160 hp Mercedes D.III

Wing: Span 10.20 m

Area 36.00 m2

General: Empty Weight 780 kg

Loaded Weight 1260 kg

Climb: 1000m 6.0 min

2000m 16.5 min

3000m 30.7 min

4000m 69.0 min

Ceiling: 4200m

The single-bay 6A2 was designed as a two-seat fighter. Powered by a 160 hp Mercedes D.III, its first test flight in January 1916 revealed problematic handling qualities, but extensive experimentation and modification finally gave the 6A2 'excellent flight characteristics' according to Friedrich Budig. Unfortunately, climb rate was less than the C.I reconnaissance airplane and the wings were too 'elastic', so the X-struts were replaced with parallel struts. The 220 hp Mercedes D.IV straight-eight engine was also tried and gave very good climb rate but vibration was excessive. Records are ambiguous about whether the 160 hp Mercedes D.III was re-installed. Both flight testing and calculations indicated the 6A2 would not meet its requirements, and it was abandoned in favor of the enlarged, two-bay 6A5 prototype that became the C.III of otherwise similar appearance. The intermediate 6A3 and 6A4 were designed but probably not built.

Rumpler 6A2 Specifications

Engine: 160 hp Mercedes D.III

Wing: Span 10.20 m

Area 36.00 m2

General: Empty Weight 780 kg

Loaded Weight 1260 kg

Climb: 1000m 6.0 min

2000m 16.5 min

3000m 30.7 min

4000m 69.0 min

Ceiling: 4200m

The Rumpler 6A2 first flown in January 1916 was a two-seat fighter. The first version used 'X'-struts. (The Peter M. Bowers Collection/The Museum of Flight)

The Rumpler 6A2 was powered by a 160 hp Mercedes D.III. The first version shown here used 'X'-struts.

The second version of the 6A2 used parallel struts for greater torsional strength of the wing cellule giving improved aileron response and better controllability.

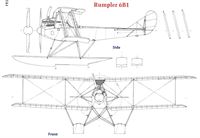

Rumpler 6B1 & 6B2

The Rumpler 6B1 (known to the Navy as the Rumpler ED) was derived from the successful Rumpler C.I two-seat reconnaissance aircraft. The weight of the floats was compensated for by elimination of the observer and his equipment, and the upper wing was moved forward to compensate for the forward shift in center of gravity. Like the Rumpler C.I and Albatros W4, the 6B1 was powered by a 160 hp Mercedes D.III. The 6B1 retained the C.I's single fixed gun for the pilot. The prototype, Marine #751, was delivered to the seaplane testing command on 7 July 1916. After testing it was accepted on 10 August, and the first production batch of ten fighters was ordered on 14 August, followed by a further batch of 25 fighters.

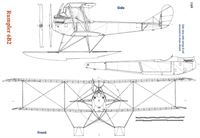

Rumpler 6B2

The Rumpler 6B1 was followed in production by the improved 6B2 that had the ability to mount two machine guns. The 6B2 also had refined aerodynamics derived from later production Rumpler C.IV aircraft that gave it greater speed; specifically the spinner was replaced by a rounded nose. Three production batches totaling 50 aircraft were ordered in early 1917. However, production was slow; the first aircraft were delivered a full ten months after being ordered, and only about half were fitted with two guns, the others mounting a single gun. Production data and other information about use suggest that by the time the 6B2 was ready, the Navy strongly preferred two-seat seaplane fighters, reducing the urgency for the 6B2 and other single-seat fighters. The 6B2 therefore saw limited operational service and was mostly used for training. Four 6B2 aircraft were sold to the Austro-Hungarian Navy, which assigned them serial numbers E1-E4.

Rumpler 6B1 & 6B2 Production

Marine Numbers Qty Notes

751, 787-788 3 Prototypes, C.I tailplane

890-899 10 First 6B1 production, C.IV tailplane

1037-1061 25 Second 6B1 production

1062-1066 5 6B2 pre-production

1188-1207 20 First 6B2 production

1434-1458 25 Second 6B2 production

The Rumpler 6B1 (known to the Navy as the Rumpler ED) was derived from the successful Rumpler C.I two-seat reconnaissance aircraft. The weight of the floats was compensated for by elimination of the observer and his equipment, and the upper wing was moved forward to compensate for the forward shift in center of gravity. Like the Rumpler C.I and Albatros W4, the 6B1 was powered by a 160 hp Mercedes D.III. The 6B1 retained the C.I's single fixed gun for the pilot. The prototype, Marine #751, was delivered to the seaplane testing command on 7 July 1916. After testing it was accepted on 10 August, and the first production batch of ten fighters was ordered on 14 August, followed by a further batch of 25 fighters.

Rumpler 6B2

The Rumpler 6B1 was followed in production by the improved 6B2 that had the ability to mount two machine guns. The 6B2 also had refined aerodynamics derived from later production Rumpler C.IV aircraft that gave it greater speed; specifically the spinner was replaced by a rounded nose. Three production batches totaling 50 aircraft were ordered in early 1917. However, production was slow; the first aircraft were delivered a full ten months after being ordered, and only about half were fitted with two guns, the others mounting a single gun. Production data and other information about use suggest that by the time the 6B2 was ready, the Navy strongly preferred two-seat seaplane fighters, reducing the urgency for the 6B2 and other single-seat fighters. The 6B2 therefore saw limited operational service and was mostly used for training. Four 6B2 aircraft were sold to the Austro-Hungarian Navy, which assigned them serial numbers E1-E4.

Rumpler 6B1 & 6B2 Production

Marine Numbers Qty Notes

751, 787-788 3 Prototypes, C.I tailplane

890-899 10 First 6B1 production, C.IV tailplane

1037-1061 25 Second 6B1 production

1062-1066 5 6B2 pre-production

1188-1207 20 First 6B2 production

1434-1458 25 Second 6B2 production

Rumpler 6B1 Marine #751 after camouflage was roughly applied at Zeebrugge. The aircraft has also gained a national insignia on the fuselage. This is how the aircraft looked when flown on operations.

Rumpler 6B2 Marine #1063 in standard late-war naval camouflage and markings with three white circles added as a tactical marking.

Rumpler 6B2 Marine #1066 of the pre-production batch of 6B2 fighters. By this time the standard late-war naval three-color camouflage fabric was standard on the upper surfaces.

Rumpler 6B2 Marine #1439 in standard late-war naval camouflage with a large white circle added as a tactical marking. The fin also appears to be in three-color naval camouflage fabric, perhaps resulting from a repair.

Из-за своих размеров 6В не мог вести маневренные воздушные бои с истребителями

The first prototype Rumpler 6B1, Marine #751, while at the SVK in Warnemunde.The single, fixed machinegun for the pilot has now been installed.

The first prototype Rumpler 6B1, Marine #751, while at the SVK in Warnemunde.The single, fixed machinegun for the pilot has now been installed.

The first prototype Rumpler 6B1, Marine#751, while at the SVK in Warnemunde.This view shows the clean lines of this large floatplane fighter. Being a large, two-bay design derived from a reconnaissance two-seater, the 6B1 was not as fast as the competing Albatros W4 and Brandenburg KDW. However, it had a reasonably good performance and excellent handling and flying qualities; on operations it was as successful as the Albatros W4 and far more successful than the fast but tricky Brandenburg KDW.

The prototype Rumpler 6B1 photographed at the SVK at Warnemunde, where the aircraft was delivered on July 7, 1916. It was accepted on August 10, 1916, and this was quickly followed by a production order for the first batch of 10 aircraft on August 14, before the next two prototypes, 787 and 788, were completed. Someone has drawn in the outline of the fin and rudder on the original print due to the low contrast between the sky and the aircraft.

The first prototype Rumpler 6B1 while at the SVK in Warnemunde.The light color does not contrast well with the sky background, which was good for air-to-air camouflage and bad for photography. Power was provided by a 160 hp Mercedes D.III engine.The first three prototypes had the C.I horizontal stabilizers with straight leading edges; production aircraft had the C.IV tailplane with curved leading edges.

Rumpler 6B1 Marine #899 was the last aircraft of the first production batch. It is seen here being hoisted by a crane for launching, something every German seaplane was equipped to do.

Rumpler 6B1 Marine #1042 of the second production batch is launched into the water and is seen just leaving the launching dolly. This aircraft was assigned to Konstanza on May 15, 1917, suggesting this photograph was taken there.

The Rumpler 6B1 was one of Germany’s most successful single-seat floatplane fighters. Here an enthusiastic naval pilot puts on an aerobatic show in a Rumpler 6B1 Marine #1045. Nicely shown are the upper surfaces which are covered in the pre-printed fabric pattern. This practice was meant to spare paint and also weight. The Rumpler 6B1 was replaced in its role by the two-seat Hansa-Brandenburg W.12 in service, but was retained in the trainer role.

Rumpler 6B1 Marine #1045 in flight. All 6B1 fighters except the three prototypes had the curved C.IV horizontal tail.

A Rumpler 6B1 performs for the camera. Despite being derived from a two-seat reconnaissance airplane, the 6B1 had good performance and handling and was well-liked by its pilots.