Книги

Centennial Perspective

C.Owers

French Warplanes of WWI. Volume 1: Fighters

244

C.Owers - French Warplanes of WWI. Volume 1: Fighters /Centennial Perspective/ (43)

In this photograph the different tones of the metal around the cowling stand out. Some Nieuport cowlings were manufactured in three parts and this may explain the dark band. It has not been possible to determine whether this was a band or part of the cowling. The Armstrong-Whitworth FK.10 quadraplane is in the background and points that the location is probably the Aeroplane Experimental Station at Martlesham Heath, where it was tested in April 1917.

"Camp d'aviation. Visite du president Poincare. Le president complimenre un aviateur." The president of France M Poincare on a visit to Villacoublay on 25 June 1918, complicates the aviator with the Nieuport monoplane. Behind the Nieuport is a Sopwith Dolphin that was at Villacoublay for evaluation by the French.

Two Polish MoS 30 E 1 trainers, carrying the unit numerals "5" and "6" on their fins, in a hangar at Torun, with a Fokker E.V, D.VII and an unidentified German type. At this time the Morane-Saulniers were still carrying French markings - red, white blue rudder stripes and cockades on their wings. The other aircraft carry the Polish national markings.

Two Polish MoS 30 E 1 trainers, carrying the unit numerals "5" and "6" on their fins, in a hangar at Torun, with a Fokker E.V, D.VII and an unidentified German type. At this time the Morane-Saulniers were still carrying French markings - red, white blue rudder stripes and cockades on their wings. The other aircraft carry the Polish national markings.

The De Marcay scout at Villacoublay for its official trials. The S.A.B 1C.1 is visible to the left background.

The Breguet LE - the Laboratorie Eiffel Monoplane

Alexandre Gustave Boenickhausen-Eiffel (1832-1923) is commonly known, if at all, as the creator of the Eiffel Tower in Paris, that was built as a temporary exhibit for the Paris Exposition of 1889. Although steel was displacing iron, Eiffel always worked in iron and so the tower was constructed in iron. After his retirement due to his being involved in the Panama Canal scandal of 1888 he became interested in meteorology and aerodynamics.

He examined the effect of air resistance on various shapes and began by dropping them of the Eiffel Tower with a measuring apparatus attached. He built his laboratory at the foot of the Tower in 1905 and his first wind tunnel there in 1909. Moving to new premises in 1912 he built a larger wind tunnel. He was awarded the Samuel P Langley Medal for Aerodynamics by the US Smithsonian Institute in 1913. His book Resistance de l’Air is a classic and established his reputation as an important contributor to the science of aerodynamics.

After the outbreak of the war Eiffel closed his Laboratory but the Government asked him to reopen it. French manufacturers submitted models of their aircraft for testing, the results being held in secret until after the war when they were published en block as Resume des principaux travaux executes durant la guerre au laboratoire aerodynamique Eiffel entre 1915 et 1918.

It is thought that the design of the Eiffel aeroplane began in the second half of 1916. Models were constructed to test various forms of the fuselage in the wind tunnel. Wing behaviour at different flight regimes, aileron efficiency and stability were measured.

French patent No.503,363 for an avion de chasse a grande vitesse (high speed fighter) was applied for by M. Gustave Eiffel, a resident of France (Seine) on 16 March 1917, and published on 9 June 1920. According to Devaux there were still problems with the many different novel features of the Eiffel monoplane that still had to be worked out when Eiffel submitted his patent. The patent is worth quoting in full:

The present invention relates to an airplane specially designed for the purpose of fulfilling the role of a fighter aircraft; it is established on the following principle:

The resistance of well streamlined bodies is almost entirely due to the friction of the air, that is to say, which is very feeble. However, all the parts of an aircraft can be streamlined, even the wings, especially for these, if one chooses the weight of the aircraft, the power of the motor and the bearing surface, so as to fly at a very low range.

It is also possible to use with relatively thick wings and to insert spars sufficiently solid to remove any bracing which is such a great cause of resistance.

To this end, instead of a biplane cell, one would adopt a monoplane wing, the use of which eliminates all the bracing and allows a greater lift for the same resistance.

There is reason to believe that an aircraft constructed as stated, would achieve speeds superior to those which the present fighter aircraft have reached.

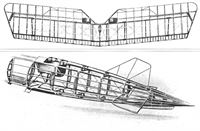

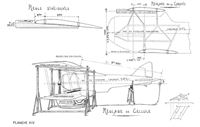

All these arrangements are represented in the accompanying drawing, of which Figs. 1, 2 and 3, are respectively a plan, an elevation and a side view of the aeroplane reduced to a scale of 1/50; in Fig. 4 is a larger scale view of a section of one of the wings.

The aircraft comprises a fuselage a having a rectangular cross-section and a length of about 6 m and a 0.8 m2 torque surface which, according to tests carried out at the Laboratory, have the minimum of resistance. The fuselage a has a 220-hp engine b in front, operating a propeller c rotating at about 2000 rpm, specially adapted according to the tests, in order to achieve at least 76% of the maximum thrust.

The radiator d is composed of several vertical fins through which the water flows. It is placed below the fuselage at the right of the engine and is in contact with the current of air to which it presents only a very low resistance.

The pilot is installed behind the engine and protected by coamings that eliminate almost completely the resistance of his head to the air.

The elevators and rudder g-g are placed at the end of the fuselage. Their control mechanisms are contained inside the fuselage and are not subjected to the resistance of the air.

The machine gun is contained inside the fuselage and fires through the propeller.

The wing, which consists of two symmetrical parts h-h, has together a wingspan of less than 10 m. They are connected directly to the frames that ensure the rigidity of the fuselage. Each of these wings forms a trapezoidal surface of about 10 m with a maximum chord of 2.50 m and a minimum width of 2 m. It is built around two box-shaped spare i, i1, made of duralumin (resistant and extremely light) sheets. The spars have been calculated with a coefficient of safety of 6 calculated on the greatest stresses that the aeroplane can undergo in flight. These two longitudinal members bear the wooden ribs and covered with linen having the profile j, that according to the Laboratory tests, is the most favorable for flight.

The ailerons are carried at the extremities of the wings in order to ensure the transverse stability.

In order to reduce the overhang of the side members, two small struts k of streamlined steel tubes are assembled, which also have the effect of better connecting the wing with the fuselage, and whose air resistance is practically negligible.

The wings are placed at the bottom of the fuselage which makes it possible to give good visibility. This new arrangement for a monoplane is a characteristic of the design.

Thanks to the construction of the wing and the use of duralumin, the weight of the aircraft for flight does not exceed 700 kg, which is a normal weight for aircraft of this type.

The landing gear is formed by an axle carrying two wheels with elastic shock absorption and with the two frames attached to the fuselage.

What constitutes the invention is not such and such a detail, of which analogies would be found in existing aircraft, but in the assembly of the aircraft which presents a new arrangement of attachments with respect to the fuselage and in which air resistance has been reduced to an extent which has not yet been realized, while at the same time employing a relatively large bearing surface, which makes it possible to achieve a high ceiling and low landing speed, while at the same time achieving speeds that are exceptional.

What was remarkable was that the drawings accompanying the patent were for a low-wing monoplane that would have not looked out of place at any 1920 air racing circuit. The patent then described the methods that would be adopted to overcome drag. The motor was stated to be a 220-hp type mounted in the front of the fuselage. Although the type is not stated it is certain that it was meant to be the 220-hp Hispano-Suiza.

Although the patent bears only Eiffel's name, it is considered that Wladimir Margoulis, then head of the Eiffel laboratory, would have contributed to the design, as well as another Russian, Nicolai Zhukovsky.

The wings were semi-cantilevered. Struts ran from the upper longerons to the first compression member of the wing. Conventionally constructed around two parallel spars, the wings had tapered leading and trailing edges. The patent claimed that the design allowed the use of thick spars made up from duralumin. It was natural for Eiffel to consider metal construction for his aircraft. The factory of safety was stated to be 6. While claiming that the design allowed for thick wing sections the aerofoil section illustrated in the patent drawings was a thin high-speed section with sharp leading and trailing edges, convex undersurface and its maximum camber at about 40% of the chord.

The tail surfaces included a balanced rudder but without a fin or fixed tailplane. The new type of radiator, named a lames profondes, was placed under the fuselage between the undercarriage legs.

The wings proved to only have a safety factor of 3. Although the patent had mentioned a factor of 6, the S.T.Ae had adopted 6.5 as the minimum factor for fighters. This led to the wing being redesigned to a factor of 7.5.

The design was presented to Painleve, the Minister of War, on 11 July 1917, and permission to build the machine was granted. Eiffel realised that he did not have the facilities for building an aircraft and asked the Minister to select a manufacturer to build the machine as I do not intend, however, according to the traditions of my laboratory, to derive any personal pecuniary profit from the acceptance of this offer. The construction was given to the Breguet company and was known as the Breguet LE in official files (LE for Laboratorie Eiffel}. The machine that emerged would have been a collaboration between the engineers at the Breguet company under engineer Vullierme, and those from the Laboratorie Eiffel.

The machine was to be delivered by 10 January 1918, with a 220-hp Hispano-Suiza engine for a cost of 20,000 F. Eiffel had chosen, after numerous wind tunnel tests, a wing section that had a biconvex profile with a pointed leading edge.

The airscrew was considered part of the total design in the patent and was designed by the Laboratorie Eiffel. It was manufactured by the Ratmanoff firm. Eiffel ordered three sets of wings from the Societe de Constructions de Levallois which firm manufactured the duralumin spars. Problems were experienced with the large sheets and strips of duralimin that twisted during transportation and storage. The machine's construction was delayed due to the shortage of duralumin and it was not possible to fly the machine in December as proposed.

The monoplane that emerged was very similar to the patent drawings. A direct-drive 180-hp Hispano-Suiza was installed behind a neat spinner, rather than the geared 220-hp version specified in the patent. The undercarriage followed Sopwith design with a half-axle for each wheel that was pivoted at the centre between two spreader bars and rubber shock cord at the simple v-struts. The ailerons were operated by a tube. The hinge of the aileron consisted of a tube extended into the cockpit that was turned in order to move the aileron.

Under the heading "BREGUET" the following report was made by the RFC liaison officer Maj J.P.C. Sewell: -

The interesting EIFFEL machine built by this house was most disappointing in its tests, the wing supports breaking at 3. The output of Breguets owing to the change from Renault to Fiats is also unsatisfactory. One 400 hp Lorraine has been tried in a Breguet AV.

Presumably the "wing supports" refers to the struts connecting the wing to the fuselage. The wings were reinforced and Sewell reported in February that the novel EIFFEL machine which has broken at 3 during its first sand tests has now been reinforced and broken at 7.5 when tested recently. This machine has not yet flown.

The Breguet-Eiffel monoplane was delivered to Villacoublay in March 1918. The machine had a fixed tailplane with plain elevators and rudder. As described in the patent, the operation of these surfaces was concealed inside the machine. Breguet's test pilot Andre de Bailliencourt was tied up with testing the Breguet 14 with the 420-hp Renault engine and a Spad pilot who was convalescing from an illness, Jean Saucliere, agreed to fly the LE monoplane.

Breguet naturally turned to one of his in-house pilots, Andre de Bailliencourt, who initially was involved in setting out the lay-out of the cockpit of the LE with Margoulis and the mechanic Louis Ramondou. When Breguet asked Bailliencourt to make the first flights, Bailliencourt, who was accustomed to heavier planes such as the Breguet XIV, asked to spend some time in a fighter school to familiarize with single-seaters of the Spad or Nieuport type. Bailliencourt was also tied up with testing the Breguet 14 with the 420-hp Renault engine and Breguet turned to other pilots. 27 years old fighter pilot Jean Saucliere, the son of the lyric artist Anne-Marie Saucliere, was recovering from wounds and had been working in the Breguet office as an archivist while recuperating, as was the practice at this period.

Saucliere had been assigned in November 1916 to the Escadrille N79 on Nieuports, where he had won two aerial victories on June 3 and 22 July 1917. The Escadrille reequipped with the Spad VII, then the Spad XIII, becoming Spa 79. Appointed sous-lieutenant on 14 September 14, he was shot down on 11 November and hospitalized with serious injuries. The opportunity to fly was too good to resist and Saucliere accepted the position at a lower salary than the other Breguet in-house pilots. The agreement was simple with a bonus at the end of the first flight.

After fine tuning the engine, the pilot took a seat for a test during the first half of March 1918, which ended quickly. Saucliere had applied full throttle causing the aircraft to take off without achieving flying speed, and it broke the landing gear when it hit the ground.

The plane was repaired and a new test organized in Villacoublay on 27 March. While Ramondou was busy preparing the plane and checking its engine, Saucliere had casually arrived. The young man already announced that on the occasion of his first flight, he intended to visit his Escadrille. Breguet had again asked Bailliencourt to make the first flight, but Bailliencourt repeated his request for additional training. Breguet, probably under time constraints, decided to entrust the prototype again to the young sous-lieutenant.

Sewell's final report on the monoplane stated that the machine, after two or three flights, was crashed and the pilot killed.

On 28 March 1918, the machine had been again ready for testing. After a run past the equipment set up to record its speed, it climbed to about 150 feet and then dived into the ground with the motor full out. It burst into flames killing Saucliere.

What caused the crash was not determined as there was not much left after the fire was extinguished. It may have been the problem with the pilot who could have been in an unfit condition to fly following his illness. What was remarkable was that on this single run the LE showed a higher speed than that estimated for the new Spad with the 300-hp Hispano-Suiza!

An airframe to suit the 300-hp Hispano-Suiza was already in construction in January 1918. A French report for April showed three Eiffel Mono(planes), powered by a 300-hp Hispano, 220-Lorraine and 180M-hp Hispano respectively. The wing area for all three was shown as 20 m2. It appears that the loss of the first machine led to the work being stopped on further examples of the monoplane. According to P Ricco, Breguet had limited confidence in the design and blamed it for the accident. J.M. Bruce notes that Margoulis blamed himself for Saucliere death.

Other proposals were a 220-hp Lorraine-Dietrich powered version of the LE. A report of May 1918 stated that this version was a biplane. This would seem to be against everything that Eiffel had stated in his patent application. A meeting took place towards the end of July between Eiffel, Louis Breguet and Captaine Albert Eteve (the Chef du Service general des avions of the S.T.Ae), at which they were told by Eteve that work was to continue. Breguet agreed on condition that the aircraft was a biplane. This would seem to confirm Breguet's limited confidence in the monoplane design. With all his own development work Breguet did not have the resources available to devote to this project and in the event the biplane never eventuated, a STAe test report of 29 November 1918, noted that the Breguet LE had been abandoned.

Eiffel did not consider his monoplane a failure. In a 1919 publication he stated that the LE had been copied by Junkers, not appreciating the work done by Junkers in determining his aerofoil. In 1920, Eiffel made similar claims that the Junkers-Fokker wing was taken from his LE machine. Eiffel died on 27 December 1923. Although he made a great contribution to aeronautics, he never seemed to accept the loss of the LE monoplane.

Breguet LE Specifications

Source 1 2 3

Dimensions in m

Span 9.78 9.78 9.78

Length 6.35 6.35 6.35

Height - 2.0 2.00

Areas in m2

Wings 20 20 20

Ailerons - - 2.09

Horizontal Tailplane - - 0.84

Rudder - - 1.18

Fin - - 0.15

Rudder - - 0.64

Weights in kg

Empty 495 495 495

Pilot - - 80

Fuel - - 80

Military load - - 40

Accessories - - 5

Total 700 700 700

Performance in km/h

at 2,000 m - - 270

at 4,000 m - 220 269

at ceiling - - 204

Climb to

4,000 m - 10 min -

Endurance in hrs - 8 -

1) J Devaux Data.

2) J. M. Bruce Data.

3) P Ricco. "De l'Avion Eiffel au Leo 9." Avion, France, No. 232, 2019.

Construction of the LE at Breguet

Date Hispano-Suiza 220-hp Lorraine-Dietrich 8 Bd 275-hp Hispano-Suiza 8Fb 300-hp Source

09.11.1917 Being assembled. Expected to be ready 10 December Design only Design study requested by Eiffel. 1

18.12.1917 Assembling, will be ready December. Design only Design study requested by Eiffel. 1

12.1917 200-hp Hispano- Suiza being fitted. In construction. - 2

29.12.1917 In assembly, will be ready by 15 January 1918. - In construction. 1

02 1918 - - In construction. 3

01.05.1918. Crashed. (Engine identified as 180 Hispano). Work suspended. (Identified as biplane with 220 Lorraine) Work suspended. 4

Sources:

1) Monthly Reports on new aircraft.

2) Situation at Breguet Company workshops.

3) Reports on situation with regard to utilisation of new motors.

4) "Department of Aircraft Production, British Ministry of Munitions of War, Paris, Monthly Aeroplane Report. May 1st 1918. French Experimental Aeroplanes, Scouts and Fighters." Chart from TNA AIR1/1071/204/5/1639. RAF Museum, J.M. Bruce Collection Box 15.

Alexandre Gustave Boenickhausen-Eiffel (1832-1923) is commonly known, if at all, as the creator of the Eiffel Tower in Paris, that was built as a temporary exhibit for the Paris Exposition of 1889. Although steel was displacing iron, Eiffel always worked in iron and so the tower was constructed in iron. After his retirement due to his being involved in the Panama Canal scandal of 1888 he became interested in meteorology and aerodynamics.

He examined the effect of air resistance on various shapes and began by dropping them of the Eiffel Tower with a measuring apparatus attached. He built his laboratory at the foot of the Tower in 1905 and his first wind tunnel there in 1909. Moving to new premises in 1912 he built a larger wind tunnel. He was awarded the Samuel P Langley Medal for Aerodynamics by the US Smithsonian Institute in 1913. His book Resistance de l’Air is a classic and established his reputation as an important contributor to the science of aerodynamics.

After the outbreak of the war Eiffel closed his Laboratory but the Government asked him to reopen it. French manufacturers submitted models of their aircraft for testing, the results being held in secret until after the war when they were published en block as Resume des principaux travaux executes durant la guerre au laboratoire aerodynamique Eiffel entre 1915 et 1918.

It is thought that the design of the Eiffel aeroplane began in the second half of 1916. Models were constructed to test various forms of the fuselage in the wind tunnel. Wing behaviour at different flight regimes, aileron efficiency and stability were measured.

French patent No.503,363 for an avion de chasse a grande vitesse (high speed fighter) was applied for by M. Gustave Eiffel, a resident of France (Seine) on 16 March 1917, and published on 9 June 1920. According to Devaux there were still problems with the many different novel features of the Eiffel monoplane that still had to be worked out when Eiffel submitted his patent. The patent is worth quoting in full:

The present invention relates to an airplane specially designed for the purpose of fulfilling the role of a fighter aircraft; it is established on the following principle:

The resistance of well streamlined bodies is almost entirely due to the friction of the air, that is to say, which is very feeble. However, all the parts of an aircraft can be streamlined, even the wings, especially for these, if one chooses the weight of the aircraft, the power of the motor and the bearing surface, so as to fly at a very low range.

It is also possible to use with relatively thick wings and to insert spars sufficiently solid to remove any bracing which is such a great cause of resistance.

To this end, instead of a biplane cell, one would adopt a monoplane wing, the use of which eliminates all the bracing and allows a greater lift for the same resistance.

There is reason to believe that an aircraft constructed as stated, would achieve speeds superior to those which the present fighter aircraft have reached.

All these arrangements are represented in the accompanying drawing, of which Figs. 1, 2 and 3, are respectively a plan, an elevation and a side view of the aeroplane reduced to a scale of 1/50; in Fig. 4 is a larger scale view of a section of one of the wings.

The aircraft comprises a fuselage a having a rectangular cross-section and a length of about 6 m and a 0.8 m2 torque surface which, according to tests carried out at the Laboratory, have the minimum of resistance. The fuselage a has a 220-hp engine b in front, operating a propeller c rotating at about 2000 rpm, specially adapted according to the tests, in order to achieve at least 76% of the maximum thrust.

The radiator d is composed of several vertical fins through which the water flows. It is placed below the fuselage at the right of the engine and is in contact with the current of air to which it presents only a very low resistance.

The pilot is installed behind the engine and protected by coamings that eliminate almost completely the resistance of his head to the air.

The elevators and rudder g-g are placed at the end of the fuselage. Their control mechanisms are contained inside the fuselage and are not subjected to the resistance of the air.

The machine gun is contained inside the fuselage and fires through the propeller.

The wing, which consists of two symmetrical parts h-h, has together a wingspan of less than 10 m. They are connected directly to the frames that ensure the rigidity of the fuselage. Each of these wings forms a trapezoidal surface of about 10 m with a maximum chord of 2.50 m and a minimum width of 2 m. It is built around two box-shaped spare i, i1, made of duralumin (resistant and extremely light) sheets. The spars have been calculated with a coefficient of safety of 6 calculated on the greatest stresses that the aeroplane can undergo in flight. These two longitudinal members bear the wooden ribs and covered with linen having the profile j, that according to the Laboratory tests, is the most favorable for flight.

The ailerons are carried at the extremities of the wings in order to ensure the transverse stability.

In order to reduce the overhang of the side members, two small struts k of streamlined steel tubes are assembled, which also have the effect of better connecting the wing with the fuselage, and whose air resistance is practically negligible.

The wings are placed at the bottom of the fuselage which makes it possible to give good visibility. This new arrangement for a monoplane is a characteristic of the design.

Thanks to the construction of the wing and the use of duralumin, the weight of the aircraft for flight does not exceed 700 kg, which is a normal weight for aircraft of this type.

The landing gear is formed by an axle carrying two wheels with elastic shock absorption and with the two frames attached to the fuselage.

What constitutes the invention is not such and such a detail, of which analogies would be found in existing aircraft, but in the assembly of the aircraft which presents a new arrangement of attachments with respect to the fuselage and in which air resistance has been reduced to an extent which has not yet been realized, while at the same time employing a relatively large bearing surface, which makes it possible to achieve a high ceiling and low landing speed, while at the same time achieving speeds that are exceptional.

What was remarkable was that the drawings accompanying the patent were for a low-wing monoplane that would have not looked out of place at any 1920 air racing circuit. The patent then described the methods that would be adopted to overcome drag. The motor was stated to be a 220-hp type mounted in the front of the fuselage. Although the type is not stated it is certain that it was meant to be the 220-hp Hispano-Suiza.

Although the patent bears only Eiffel's name, it is considered that Wladimir Margoulis, then head of the Eiffel laboratory, would have contributed to the design, as well as another Russian, Nicolai Zhukovsky.

The wings were semi-cantilevered. Struts ran from the upper longerons to the first compression member of the wing. Conventionally constructed around two parallel spars, the wings had tapered leading and trailing edges. The patent claimed that the design allowed the use of thick spars made up from duralumin. It was natural for Eiffel to consider metal construction for his aircraft. The factory of safety was stated to be 6. While claiming that the design allowed for thick wing sections the aerofoil section illustrated in the patent drawings was a thin high-speed section with sharp leading and trailing edges, convex undersurface and its maximum camber at about 40% of the chord.

The tail surfaces included a balanced rudder but without a fin or fixed tailplane. The new type of radiator, named a lames profondes, was placed under the fuselage between the undercarriage legs.

The wings proved to only have a safety factor of 3. Although the patent had mentioned a factor of 6, the S.T.Ae had adopted 6.5 as the minimum factor for fighters. This led to the wing being redesigned to a factor of 7.5.

The design was presented to Painleve, the Minister of War, on 11 July 1917, and permission to build the machine was granted. Eiffel realised that he did not have the facilities for building an aircraft and asked the Minister to select a manufacturer to build the machine as I do not intend, however, according to the traditions of my laboratory, to derive any personal pecuniary profit from the acceptance of this offer. The construction was given to the Breguet company and was known as the Breguet LE in official files (LE for Laboratorie Eiffel}. The machine that emerged would have been a collaboration between the engineers at the Breguet company under engineer Vullierme, and those from the Laboratorie Eiffel.

The machine was to be delivered by 10 January 1918, with a 220-hp Hispano-Suiza engine for a cost of 20,000 F. Eiffel had chosen, after numerous wind tunnel tests, a wing section that had a biconvex profile with a pointed leading edge.

The airscrew was considered part of the total design in the patent and was designed by the Laboratorie Eiffel. It was manufactured by the Ratmanoff firm. Eiffel ordered three sets of wings from the Societe de Constructions de Levallois which firm manufactured the duralumin spars. Problems were experienced with the large sheets and strips of duralimin that twisted during transportation and storage. The machine's construction was delayed due to the shortage of duralumin and it was not possible to fly the machine in December as proposed.

The monoplane that emerged was very similar to the patent drawings. A direct-drive 180-hp Hispano-Suiza was installed behind a neat spinner, rather than the geared 220-hp version specified in the patent. The undercarriage followed Sopwith design with a half-axle for each wheel that was pivoted at the centre between two spreader bars and rubber shock cord at the simple v-struts. The ailerons were operated by a tube. The hinge of the aileron consisted of a tube extended into the cockpit that was turned in order to move the aileron.

Under the heading "BREGUET" the following report was made by the RFC liaison officer Maj J.P.C. Sewell: -

The interesting EIFFEL machine built by this house was most disappointing in its tests, the wing supports breaking at 3. The output of Breguets owing to the change from Renault to Fiats is also unsatisfactory. One 400 hp Lorraine has been tried in a Breguet AV.

Presumably the "wing supports" refers to the struts connecting the wing to the fuselage. The wings were reinforced and Sewell reported in February that the novel EIFFEL machine which has broken at 3 during its first sand tests has now been reinforced and broken at 7.5 when tested recently. This machine has not yet flown.

The Breguet-Eiffel monoplane was delivered to Villacoublay in March 1918. The machine had a fixed tailplane with plain elevators and rudder. As described in the patent, the operation of these surfaces was concealed inside the machine. Breguet's test pilot Andre de Bailliencourt was tied up with testing the Breguet 14 with the 420-hp Renault engine and a Spad pilot who was convalescing from an illness, Jean Saucliere, agreed to fly the LE monoplane.

Breguet naturally turned to one of his in-house pilots, Andre de Bailliencourt, who initially was involved in setting out the lay-out of the cockpit of the LE with Margoulis and the mechanic Louis Ramondou. When Breguet asked Bailliencourt to make the first flights, Bailliencourt, who was accustomed to heavier planes such as the Breguet XIV, asked to spend some time in a fighter school to familiarize with single-seaters of the Spad or Nieuport type. Bailliencourt was also tied up with testing the Breguet 14 with the 420-hp Renault engine and Breguet turned to other pilots. 27 years old fighter pilot Jean Saucliere, the son of the lyric artist Anne-Marie Saucliere, was recovering from wounds and had been working in the Breguet office as an archivist while recuperating, as was the practice at this period.

Saucliere had been assigned in November 1916 to the Escadrille N79 on Nieuports, where he had won two aerial victories on June 3 and 22 July 1917. The Escadrille reequipped with the Spad VII, then the Spad XIII, becoming Spa 79. Appointed sous-lieutenant on 14 September 14, he was shot down on 11 November and hospitalized with serious injuries. The opportunity to fly was too good to resist and Saucliere accepted the position at a lower salary than the other Breguet in-house pilots. The agreement was simple with a bonus at the end of the first flight.

After fine tuning the engine, the pilot took a seat for a test during the first half of March 1918, which ended quickly. Saucliere had applied full throttle causing the aircraft to take off without achieving flying speed, and it broke the landing gear when it hit the ground.

The plane was repaired and a new test organized in Villacoublay on 27 March. While Ramondou was busy preparing the plane and checking its engine, Saucliere had casually arrived. The young man already announced that on the occasion of his first flight, he intended to visit his Escadrille. Breguet had again asked Bailliencourt to make the first flight, but Bailliencourt repeated his request for additional training. Breguet, probably under time constraints, decided to entrust the prototype again to the young sous-lieutenant.

Sewell's final report on the monoplane stated that the machine, after two or three flights, was crashed and the pilot killed.

On 28 March 1918, the machine had been again ready for testing. After a run past the equipment set up to record its speed, it climbed to about 150 feet and then dived into the ground with the motor full out. It burst into flames killing Saucliere.

What caused the crash was not determined as there was not much left after the fire was extinguished. It may have been the problem with the pilot who could have been in an unfit condition to fly following his illness. What was remarkable was that on this single run the LE showed a higher speed than that estimated for the new Spad with the 300-hp Hispano-Suiza!

An airframe to suit the 300-hp Hispano-Suiza was already in construction in January 1918. A French report for April showed three Eiffel Mono(planes), powered by a 300-hp Hispano, 220-Lorraine and 180M-hp Hispano respectively. The wing area for all three was shown as 20 m2. It appears that the loss of the first machine led to the work being stopped on further examples of the monoplane. According to P Ricco, Breguet had limited confidence in the design and blamed it for the accident. J.M. Bruce notes that Margoulis blamed himself for Saucliere death.

Other proposals were a 220-hp Lorraine-Dietrich powered version of the LE. A report of May 1918 stated that this version was a biplane. This would seem to be against everything that Eiffel had stated in his patent application. A meeting took place towards the end of July between Eiffel, Louis Breguet and Captaine Albert Eteve (the Chef du Service general des avions of the S.T.Ae), at which they were told by Eteve that work was to continue. Breguet agreed on condition that the aircraft was a biplane. This would seem to confirm Breguet's limited confidence in the monoplane design. With all his own development work Breguet did not have the resources available to devote to this project and in the event the biplane never eventuated, a STAe test report of 29 November 1918, noted that the Breguet LE had been abandoned.

Eiffel did not consider his monoplane a failure. In a 1919 publication he stated that the LE had been copied by Junkers, not appreciating the work done by Junkers in determining his aerofoil. In 1920, Eiffel made similar claims that the Junkers-Fokker wing was taken from his LE machine. Eiffel died on 27 December 1923. Although he made a great contribution to aeronautics, he never seemed to accept the loss of the LE monoplane.

Breguet LE Specifications

Source 1 2 3

Dimensions in m

Span 9.78 9.78 9.78

Length 6.35 6.35 6.35

Height - 2.0 2.00

Areas in m2

Wings 20 20 20

Ailerons - - 2.09

Horizontal Tailplane - - 0.84

Rudder - - 1.18

Fin - - 0.15

Rudder - - 0.64

Weights in kg

Empty 495 495 495

Pilot - - 80

Fuel - - 80

Military load - - 40

Accessories - - 5

Total 700 700 700

Performance in km/h

at 2,000 m - - 270

at 4,000 m - 220 269

at ceiling - - 204

Climb to

4,000 m - 10 min -

Endurance in hrs - 8 -

1) J Devaux Data.

2) J. M. Bruce Data.

3) P Ricco. "De l'Avion Eiffel au Leo 9." Avion, France, No. 232, 2019.

Construction of the LE at Breguet

Date Hispano-Suiza 220-hp Lorraine-Dietrich 8 Bd 275-hp Hispano-Suiza 8Fb 300-hp Source

09.11.1917 Being assembled. Expected to be ready 10 December Design only Design study requested by Eiffel. 1

18.12.1917 Assembling, will be ready December. Design only Design study requested by Eiffel. 1

12.1917 200-hp Hispano- Suiza being fitted. In construction. - 2

29.12.1917 In assembly, will be ready by 15 January 1918. - In construction. 1

02 1918 - - In construction. 3

01.05.1918. Crashed. (Engine identified as 180 Hispano). Work suspended. (Identified as biplane with 220 Lorraine) Work suspended. 4

Sources:

1) Monthly Reports on new aircraft.

2) Situation at Breguet Company workshops.

3) Reports on situation with regard to utilisation of new motors.

4) "Department of Aircraft Production, British Ministry of Munitions of War, Paris, Monthly Aeroplane Report. May 1st 1918. French Experimental Aeroplanes, Scouts and Fighters." Chart from TNA AIR1/1071/204/5/1639. RAF Museum, J.M. Bruce Collection Box 15.

The proliferation of Breguet biplanes in the background indicates that this photograph was taken at the Breguet field.

Laboratory Eiffel LE fighter. The aircraft was a low wing monoplane and the wing was almost completely of cantilever design except for two bracing struts on either side of the fuselage.

Despite its very advanced aerodynamic concept, apparent here, the sole prototype of the Breguet LE of 1918 was flown only twice.

Despite its very advanced aerodynamic concept, apparent here, the sole prototype of the Breguet LE of 1918 was flown only twice.

The Courtois-Suffit Lescop

The Courtois-Suffit Lescop scout was an experimental aircraft that was designed by Roger Courtois-Suffit and Capitaine Lescop to meet the French C1 specification (Fighter single seat). Construction was undertaken by the S.A.I.B. (Societe Anonyme d’Applications Industrielles du Bois) of 49 Rue St, Blaise, Paris. The most innovative feature of the machine was that the aircraft featured leading edge flaps, this being one of the first, if not the first time these had been fitted to an aeroplane.

The British Aviation Commission sent preliminary details of the experimental machine to RFC HQ on 10 October 1917. The machine had variable incidence for the leading edge of the bottom planes and the leading edge of the tailplane. Ailerons are being fitted to the bottom plane only, and the portion of the leading edge which is variable is the same length as the ailerons, viz:- 1 m. 300.

The French Section Technique are very interested in this experiment, which is intended to give a large range of speed near the ground. They estimate that the lowest speed will be about 87 k.p.h.

The variable leading edges are arranged so that they can be set in any desired position from the pilot’s seat.

The construction of this machine has only just been started ... The engine will be a 200 h.p. Clerget if one is available, otherwise a Monosoupape Gnome will be tried.

Construction began in October 1917, the US Army reporting on 23 October that the GNOME MONOSOUPAPE is also being installed in a Courtais-Suffit-Loscop. The British report on French Experimental Aeroplanes for November 1917, recorded that a 165-hp Monosoupape CSL was under construction and that a 250 Clerget biplane was being studied. Both had "Variable wing incidence for leading edges of bottom and tailplanes." Construction took a long time. A report in January 1918 stated that the machine was almost finished and was expected to be ready by the middle of the month with a Gn 9NC (160) engine. Testing was being undertaken by 1 May 1918, with a 140-hp Clerget 9Bf installed as the proposed Gnome Monosoupape 9Nc was not available. No trial results are known. The machine was not selected for series manufacture.

A conventional constructed biplane of wooden girder with fabric covering, the C.S.L. 1 emerged as a neat single bay biplane featuring "I" style interplane struts. A report by the British Maj J.C.P. Sewell on 24 April 1918, referred to the struts adopted for the COURTOIS-SUFFIT experimental machine (in designing which M. Bechereau is supposed to have helped) have adopted a single interplane strut similar to that of the German Roland 2-seater. This strut is bolted into the planes in the thickness of which socket, wire strainers and so on are completely concealed, greatly diminishing head resistance.

The struts were faired out at the top and bottom to connect with the front and rear spars. Similar struts were mounted at the fuselage. They were similar to those of the Sopwith triplane as they ran inside the fuselage longerons. A small strut ran from the upper longeron to the upper wing front spar. There were no control surfaces on the upper wing. The ailerons on the lower wing were operated Nieuport fashion by torque tubes.

The fuselage was faired out by formers and stringers from the circular cross section at the engine to an oval cross-section towards the tail. The machine resembled the Hollywood Nieuport 28 conversions with I-struts. It was proposed to use the Nieuport 28 fighter's engine, the 160-hp Gnome Monosoupape 9Nc nine-cylinder rotary. Its most revolutionary feature, as mentioned above, was the moveable flaps on the leading edge of the lower wing. These were hinged to the forward main wing spar and were 1.3 m long and 0.18 m wide. The leading edge of the tailplane was also hinged. These flaps were controlled from the cockpit. S.A.I.B had built the Sopwith 1 1/2 Strutter under licence for the French Army and the undercarriage was a typical Sopwith type with each wheel on a half-axle pivoted at the centre of the spreader bars.

The aircraft had been predicted to have speeds of 240 to 87 km/hr with the 200-hp Clerget. With the available engine it would not have achieved anything like these figures. No test details of the machine are known.

It was proposed to improve the design and a new aircraft with equi-span wings with square tips was proposed. This was to have been powered by the 300-hp Clerget then under development. Until this engine became available a 150-hp Clerget would be fitted with a large cone de penetration for flight trials. It is not known if this model was constructed, but the proposed high powered Clerget engines were unsuccessful and not developed.

Courtois-Suffit Lescop Specifications

Source 1 2 3 3

Span, m 7.800 7.80 - -

Length, m 7.600 - - -

Height, m 2.700 2.70 - -

Chord, m 1.300 - - -

Gap, m 1.700 (approx) - - -

Empty Wt, kg 490 490 490 470

Load, kg 290 - - -

Military Load, kg - - 50 50

Total, kg 780 780 750 760

Wing Area, m2 19.000 19 19 19

Speed at 4,000 m - - 210 kph 220 kph

Climb to 4,000 m - - 14 min 16 min

Endurance in hrs - - 2.5 2.5

Engine - 200-hp Clerget 11E 200 Clerget 130 Clerget

1) Details with letter of British Aviation Commission, Paris, to HQ RFC and GHQ, 10.10.1917. TNA AIR 1/2391/228/11/140.

2) J.M. Bruce data.

3) Estimated performance. "Department of Aircraft Production, British Ministry of Munitions of War, Paris, Monthly Aeroplane Report. May 1st 1918. French Experimental Aeroplanes, Scouts and Fighters." Chart from TNA AIR1/1071/204/5/1639. RAF Museum, J.M. Bruce Collection Box 15.

The Courtois-Suffit Lescop scout was an experimental aircraft that was designed by Roger Courtois-Suffit and Capitaine Lescop to meet the French C1 specification (Fighter single seat). Construction was undertaken by the S.A.I.B. (Societe Anonyme d’Applications Industrielles du Bois) of 49 Rue St, Blaise, Paris. The most innovative feature of the machine was that the aircraft featured leading edge flaps, this being one of the first, if not the first time these had been fitted to an aeroplane.

The British Aviation Commission sent preliminary details of the experimental machine to RFC HQ on 10 October 1917. The machine had variable incidence for the leading edge of the bottom planes and the leading edge of the tailplane. Ailerons are being fitted to the bottom plane only, and the portion of the leading edge which is variable is the same length as the ailerons, viz:- 1 m. 300.

The French Section Technique are very interested in this experiment, which is intended to give a large range of speed near the ground. They estimate that the lowest speed will be about 87 k.p.h.

The variable leading edges are arranged so that they can be set in any desired position from the pilot’s seat.

The construction of this machine has only just been started ... The engine will be a 200 h.p. Clerget if one is available, otherwise a Monosoupape Gnome will be tried.

Construction began in October 1917, the US Army reporting on 23 October that the GNOME MONOSOUPAPE is also being installed in a Courtais-Suffit-Loscop. The British report on French Experimental Aeroplanes for November 1917, recorded that a 165-hp Monosoupape CSL was under construction and that a 250 Clerget biplane was being studied. Both had "Variable wing incidence for leading edges of bottom and tailplanes." Construction took a long time. A report in January 1918 stated that the machine was almost finished and was expected to be ready by the middle of the month with a Gn 9NC (160) engine. Testing was being undertaken by 1 May 1918, with a 140-hp Clerget 9Bf installed as the proposed Gnome Monosoupape 9Nc was not available. No trial results are known. The machine was not selected for series manufacture.

A conventional constructed biplane of wooden girder with fabric covering, the C.S.L. 1 emerged as a neat single bay biplane featuring "I" style interplane struts. A report by the British Maj J.C.P. Sewell on 24 April 1918, referred to the struts adopted for the COURTOIS-SUFFIT experimental machine (in designing which M. Bechereau is supposed to have helped) have adopted a single interplane strut similar to that of the German Roland 2-seater. This strut is bolted into the planes in the thickness of which socket, wire strainers and so on are completely concealed, greatly diminishing head resistance.

The struts were faired out at the top and bottom to connect with the front and rear spars. Similar struts were mounted at the fuselage. They were similar to those of the Sopwith triplane as they ran inside the fuselage longerons. A small strut ran from the upper longeron to the upper wing front spar. There were no control surfaces on the upper wing. The ailerons on the lower wing were operated Nieuport fashion by torque tubes.

The fuselage was faired out by formers and stringers from the circular cross section at the engine to an oval cross-section towards the tail. The machine resembled the Hollywood Nieuport 28 conversions with I-struts. It was proposed to use the Nieuport 28 fighter's engine, the 160-hp Gnome Monosoupape 9Nc nine-cylinder rotary. Its most revolutionary feature, as mentioned above, was the moveable flaps on the leading edge of the lower wing. These were hinged to the forward main wing spar and were 1.3 m long and 0.18 m wide. The leading edge of the tailplane was also hinged. These flaps were controlled from the cockpit. S.A.I.B had built the Sopwith 1 1/2 Strutter under licence for the French Army and the undercarriage was a typical Sopwith type with each wheel on a half-axle pivoted at the centre of the spreader bars.

The aircraft had been predicted to have speeds of 240 to 87 km/hr with the 200-hp Clerget. With the available engine it would not have achieved anything like these figures. No test details of the machine are known.

It was proposed to improve the design and a new aircraft with equi-span wings with square tips was proposed. This was to have been powered by the 300-hp Clerget then under development. Until this engine became available a 150-hp Clerget would be fitted with a large cone de penetration for flight trials. It is not known if this model was constructed, but the proposed high powered Clerget engines were unsuccessful and not developed.

Courtois-Suffit Lescop Specifications

Source 1 2 3 3

Span, m 7.800 7.80 - -

Length, m 7.600 - - -

Height, m 2.700 2.70 - -

Chord, m 1.300 - - -

Gap, m 1.700 (approx) - - -

Empty Wt, kg 490 490 490 470

Load, kg 290 - - -

Military Load, kg - - 50 50

Total, kg 780 780 750 760

Wing Area, m2 19.000 19 19 19

Speed at 4,000 m - - 210 kph 220 kph

Climb to 4,000 m - - 14 min 16 min

Endurance in hrs - - 2.5 2.5

Engine - 200-hp Clerget 11E 200 Clerget 130 Clerget

1) Details with letter of British Aviation Commission, Paris, to HQ RFC and GHQ, 10.10.1917. TNA AIR 1/2391/228/11/140.

2) J.M. Bruce data.

3) Estimated performance. "Department of Aircraft Production, British Ministry of Munitions of War, Paris, Monthly Aeroplane Report. May 1st 1918. French Experimental Aeroplanes, Scouts and Fighters." Chart from TNA AIR1/1071/204/5/1639. RAF Museum, J.M. Bruce Collection Box 15.

The C.S.L.1 at the Societe Anonyme d'Applications Industrielles du Bois, 49 Rue St, Blaise, Paris. Note the Sopwith 1 1/2 Strutter in the background. The company's logo on the fuselage leaves no doubt as to its origin.

The CSL C1 is historically significant as one of the first aircraft to feature leading edge flaps.

Leading-edge flaps on the lower mainplane were a feature of the C.S.L.1, only one example of which was built and flown in 1918.

The CSL C1 is historically significant as one of the first aircraft to feature leading edge flaps.

Leading-edge flaps on the lower mainplane were a feature of the C.S.L.1, only one example of which was built and flown in 1918.

In this view the hinged outer portions of the lower wing are visible. Note the Salmson 2A2 fuselages in the background.

The de Marcay C.1

Edmund de Marcay was involved in aviation before the Great War. The de Marcay Moonen monoplane with folding wings was displayed at the January 1912 Paris Aero Show, and later appeared as a "waterplane" at a Monaco meeting. These aircraft were paid for by de Marcay, however, there is no evidence that he had a part in their designs.

The Construction Aeronautique Edmond de Marcay company was founded in 1917 with headquarters at 100 Avenue de Suffren, Paris, by Comte de Marcay and his brother-in-law, Pierre Verrier, formerly a well-known pilot at Hendon. As the firm grew a branch was established at Bordeaux. The firm specialised in fighter machines turning out about 2,000 Spad fighters during the war. M. De Marcay's understanding of mass production saw the Paris works produce 1,400 Spad 7.C.1 fighters in a year. The Bordeaux works were close behind produced 400 Spad fighters although it was later in starting production.

De Marcay wanted to produce a scout of his own and a report of 7 September 1918, noted that the author of this project having been requested to complete and modify his plans, presents a C.1 Type with 8.Pb 300 H.P. Hispano Engine instead of a Liberty. De Marcay was not an aircraft designer and it is thought that the design was undertaken by the engineer Botali. What type of Liberty was proposed for the machine is not known. J. M. Bruce suggested that the eight-cylinder L-8 was most likely the proposed power-plant. The L-8 however, proved unsuccessful and was abandoned after only eight had been completed.

The report continued to give details of the proposed aircraft:

Description: Pursuit bi-plane, single-seater with staggered cellule (520 m/m towards the front for the upper plane). Twin machine guns firing through the propeller.

Fore part of fuselage is steel tube, rear part of wood. Hispano 300 H.P. engine mounted on aluminium cradle. Radiator in the wing.

Landing gear with rubber cords in the fuselage type G.L.

Characteristics: Total surface 28 square meters. Total anticipated weight, 1050 kgs. Load per square meter, 57 kg. 5.

Construction: The calculations presented show that the airplane would be likely to show a coefficient of 15 in the static tests.

The de Karcay (sic) airplane is similar to the Spad 17. Its performances should be of the same order. This machine is accepted by the S.T.A. but under the strict reserve that it will be constructed by the de Marcay firm, with the means at its disposal.

This last sentence meant that the machine was to be built by de Marcay as a private venture. Apparently the first design for the Liberty motor was designated the de Marcay 1 and the revised design de Marcay 2.

M de Marcay "designed and constructed" a scout machine just before the end of the war and the first tests of this were taking place when the Armistice was signed according to an article in La Vie Aerienne. However, a STAe test report of 29 November 1918, states that the de Marcay C1 HS 8Fb 300-hp scout's fuselage was completed but the wings were still under construction. At the end of November the engine had just been delivered and the fuselage assembled with its forward panels applied. The wings were still under construction. J.M. Bruce states that the machine was not completed until 1919.

The machine that emerged post-Armistice was similar in appearance to a Spad in the fuselage. The wings were of unequal span with the lower wing appreciably shorter than the upper wing. The overhang was braced by oblique struts that were fixed to the lower ends of the normal interplane struts that provided a single-bay of normal bracing. Unusually shaped horn balanced ailerons were fitted to the upper wing only. A large cut-out was provided in the trailing edge of the upper wing to improve the pilot's upward view, and the lower wing roots were also provided with cut-outs to improve downward vision. The tailplane was mounted on the top longerons and the elevators were of a semi-elliptical shape. A triangular fin preceded a rounded rudder.

The engine was more closely cowled than on Spad machines, with the camshaft covers fully covered by fairings, and with liberal louvers to assist cooling. The radiator was not an aerofoil type in the upper wing but a conventional car type mounted in a circular cowl in front of the engine behind the airscrew. As with contemporary Spads a jettisonable fuel tank was mounted between the undercarriage struts where it conformed to the fuselage contours. Twin synchronised Vickers guns were the armament.

The fuselage showed some resemblance to a Spad and the myth arose that the machine used Spad components. It may have used some Spad construction techniques but owed no major component to any Spad type.

According to La Vie Aerienne the performance of the machine was such that no previous service machine had attained such speeds carrying armament and instruments. It was tested by Lt Lebeau in the C1 or single-seat fighter category of the 1919 Service Aeronautique competition held at Villacoublay and its speed made it one of the fastest fighters of its time. It was stated to have a factor of safety of 14. Its rate of climb was inferior to that of the Nieuport 29 C.1, and this machine was selected as the post-war standard fighter adopted by the French. What is not known is why nothing was done with this incredible machine, the de Marcay would have been an ideal record breaking or racing aircraft. The aircraft was advertised for sale by SAAECA de Marcay through most of the 1920s, its ultimate fate is unrecorded.

The de Marcay 3 was to have been another single-seat fighter powered by a 300-hp Hispano-Suiza engine but with an all-metal monocoque fuselage. It was never built.

Reporting on the 1919 Paris Aero Show Flight noted that de Marcay, this well-known French constructor is exhibiting a standard Spad, built under licence, a machine which is so well known as to need no reference here beyond the statement of its presence on the stand. The other aircraft displayed was the light sports-plane the passe-partout.

De Marcay went on to build low-powered sporting aircraft for a market that did not arise until too late for the firm.

de Marcay C.1 Fighter Specifications

Source 1 2 3

Span upper, m 9.250 9.250 9.25

Span lower, m 5.750 5.750 -

Length, m 6.620 6.620 6.50

Wing Area, m2 25 25 -

Load in kg - 339 339

Speed in km/h

at ground level 252 252 -

at 3000 m 232 232 237

at 5000 m 218 218 220

at 6000 m 208 208 208

Climb to 5,000 m - 16 min 16 sec -

Engine 300 H.P. 300-hp Hispano-Suiza 8Fb 300-hp Hispano-Suiza

Sources:

1) "The Marcay Machines", translation of article in La Vie Aerienne, No.163, 25.12.1919. TNA AIR1/2114/207/54/6.

2) British translation of French report on "The Marcay Machines." Stamped: 20 Jan 1910. Copy in TNA AIR1/2114/207/54/6. Bruce, J.M. repeats these specifications in Warplanes of the First World War - Fighters, Vol.4. Macdonald &. Co, UK, 1972. P.82.

3) Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft 1919.

Edmund de Marcay was involved in aviation before the Great War. The de Marcay Moonen monoplane with folding wings was displayed at the January 1912 Paris Aero Show, and later appeared as a "waterplane" at a Monaco meeting. These aircraft were paid for by de Marcay, however, there is no evidence that he had a part in their designs.

The Construction Aeronautique Edmond de Marcay company was founded in 1917 with headquarters at 100 Avenue de Suffren, Paris, by Comte de Marcay and his brother-in-law, Pierre Verrier, formerly a well-known pilot at Hendon. As the firm grew a branch was established at Bordeaux. The firm specialised in fighter machines turning out about 2,000 Spad fighters during the war. M. De Marcay's understanding of mass production saw the Paris works produce 1,400 Spad 7.C.1 fighters in a year. The Bordeaux works were close behind produced 400 Spad fighters although it was later in starting production.

De Marcay wanted to produce a scout of his own and a report of 7 September 1918, noted that the author of this project having been requested to complete and modify his plans, presents a C.1 Type with 8.Pb 300 H.P. Hispano Engine instead of a Liberty. De Marcay was not an aircraft designer and it is thought that the design was undertaken by the engineer Botali. What type of Liberty was proposed for the machine is not known. J. M. Bruce suggested that the eight-cylinder L-8 was most likely the proposed power-plant. The L-8 however, proved unsuccessful and was abandoned after only eight had been completed.

The report continued to give details of the proposed aircraft:

Description: Pursuit bi-plane, single-seater with staggered cellule (520 m/m towards the front for the upper plane). Twin machine guns firing through the propeller.

Fore part of fuselage is steel tube, rear part of wood. Hispano 300 H.P. engine mounted on aluminium cradle. Radiator in the wing.

Landing gear with rubber cords in the fuselage type G.L.

Characteristics: Total surface 28 square meters. Total anticipated weight, 1050 kgs. Load per square meter, 57 kg. 5.

Construction: The calculations presented show that the airplane would be likely to show a coefficient of 15 in the static tests.

The de Karcay (sic) airplane is similar to the Spad 17. Its performances should be of the same order. This machine is accepted by the S.T.A. but under the strict reserve that it will be constructed by the de Marcay firm, with the means at its disposal.

This last sentence meant that the machine was to be built by de Marcay as a private venture. Apparently the first design for the Liberty motor was designated the de Marcay 1 and the revised design de Marcay 2.

M de Marcay "designed and constructed" a scout machine just before the end of the war and the first tests of this were taking place when the Armistice was signed according to an article in La Vie Aerienne. However, a STAe test report of 29 November 1918, states that the de Marcay C1 HS 8Fb 300-hp scout's fuselage was completed but the wings were still under construction. At the end of November the engine had just been delivered and the fuselage assembled with its forward panels applied. The wings were still under construction. J.M. Bruce states that the machine was not completed until 1919.

The machine that emerged post-Armistice was similar in appearance to a Spad in the fuselage. The wings were of unequal span with the lower wing appreciably shorter than the upper wing. The overhang was braced by oblique struts that were fixed to the lower ends of the normal interplane struts that provided a single-bay of normal bracing. Unusually shaped horn balanced ailerons were fitted to the upper wing only. A large cut-out was provided in the trailing edge of the upper wing to improve the pilot's upward view, and the lower wing roots were also provided with cut-outs to improve downward vision. The tailplane was mounted on the top longerons and the elevators were of a semi-elliptical shape. A triangular fin preceded a rounded rudder.

The engine was more closely cowled than on Spad machines, with the camshaft covers fully covered by fairings, and with liberal louvers to assist cooling. The radiator was not an aerofoil type in the upper wing but a conventional car type mounted in a circular cowl in front of the engine behind the airscrew. As with contemporary Spads a jettisonable fuel tank was mounted between the undercarriage struts where it conformed to the fuselage contours. Twin synchronised Vickers guns were the armament.

The fuselage showed some resemblance to a Spad and the myth arose that the machine used Spad components. It may have used some Spad construction techniques but owed no major component to any Spad type.

According to La Vie Aerienne the performance of the machine was such that no previous service machine had attained such speeds carrying armament and instruments. It was tested by Lt Lebeau in the C1 or single-seat fighter category of the 1919 Service Aeronautique competition held at Villacoublay and its speed made it one of the fastest fighters of its time. It was stated to have a factor of safety of 14. Its rate of climb was inferior to that of the Nieuport 29 C.1, and this machine was selected as the post-war standard fighter adopted by the French. What is not known is why nothing was done with this incredible machine, the de Marcay would have been an ideal record breaking or racing aircraft. The aircraft was advertised for sale by SAAECA de Marcay through most of the 1920s, its ultimate fate is unrecorded.

The de Marcay 3 was to have been another single-seat fighter powered by a 300-hp Hispano-Suiza engine but with an all-metal monocoque fuselage. It was never built.

Reporting on the 1919 Paris Aero Show Flight noted that de Marcay, this well-known French constructor is exhibiting a standard Spad, built under licence, a machine which is so well known as to need no reference here beyond the statement of its presence on the stand. The other aircraft displayed was the light sports-plane the passe-partout.

De Marcay went on to build low-powered sporting aircraft for a market that did not arise until too late for the firm.

de Marcay C.1 Fighter Specifications

Source 1 2 3

Span upper, m 9.250 9.250 9.25

Span lower, m 5.750 5.750 -

Length, m 6.620 6.620 6.50

Wing Area, m2 25 25 -

Load in kg - 339 339

Speed in km/h

at ground level 252 252 -

at 3000 m 232 232 237

at 5000 m 218 218 220

at 6000 m 208 208 208

Climb to 5,000 m - 16 min 16 sec -

Engine 300 H.P. 300-hp Hispano-Suiza 8Fb 300-hp Hispano-Suiza

Sources:

1) "The Marcay Machines", translation of article in La Vie Aerienne, No.163, 25.12.1919. TNA AIR1/2114/207/54/6.

2) British translation of French report on "The Marcay Machines." Stamped: 20 Jan 1910. Copy in TNA AIR1/2114/207/54/6. Bruce, J.M. repeats these specifications in Warplanes of the First World War - Fighters, Vol.4. Macdonald &. Co, UK, 1972. P.82.

3) Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft 1919.

The Edmond de Marcay single-seater biplane, which, piloted by Lieut. Lebeau, at Villacoublay, attained speeds of 156 m.p.h. level, 147 m.p.h. at 10,000 ft., and 129 m.p.h. at 20,000 ft. It is fitted with a 300 h.p Hispano-Suiza engine, and has a span of 30 ft. 4 ins., overall length of 21 ft. 4 ins., and a useful load of 745 lbs. Its factor of safety is 14.

The De Marcay when first rolled out with a small spinner to the airscrew.

The De Marcay when first rolled out with a small spinner to the airscrew.

The De Marcay C1 was a single-seat fighter with 300-hp Hispano-Suiza 8Fb.

Powered by a 300 hp H-S 8Fb engine, the prototype de Marcay 2 flew in 1919.

The De Marcay scout at Villacoublay for its official trials. The S.A.B 1C.1 is visible to the left background.

Powered by a 300 hp H-S 8Fb engine, the prototype de Marcay 2 flew in 1919.

The De Marcay scout at Villacoublay for its official trials. The S.A.B 1C.1 is visible to the left background.

The De Marcay scout at Villacoublay for its official trials. The S.A.B 1C.1 is visible to the left background.

The De Marcay has its airscrew removed in this photograph that appear to be taken at Villacoublay. There is a Pfalz D.XII in the background with Breguet bombers.

Note the louvered panel under the fuselage of the C1. This view also shows the small pylon whose purpose is unknown. The rudder has the usual information but no tricolor stripes indicating that he machine was not built under a government contract.

Another view of the De Marcay C1 at Villacoublay. Note the small pylon at the starboard side of the centre section.

The De Marcay two-seater at the 1919 Paris Aero Show was a neat little rotary powered biplane with a removable canopy.

This is the pre-war De Marcay-Moonen 1913 racer. Equipped with a 100-hp Anzani, it raced at Monaco carrying No.18. According to Flight, it was one of 26 entries for the hydro-aeroplane competition that included five Deperdussins, three Breguets, three Borels, two Henry Farmans, two Maurice Farmans, two Nieuports, two D'Artois, two Sastras and one each of Bleriot, Morane-Saulnier, Bossi and Fokker. The wings were designed to fold back against the body in order that it might ride more securely when at anchor.

Morane-Saulnier did not abandon the parasol configuration but refined it in a series of trainers. The MS AR in its various versions was used world-wide, Poland, Belgium, Greece, Soviet Russia, in South America and the US. The US Navy purchased six (Bureau Nos. A-5977 to A-5981) in 1921 and allocated them to the Shipplane Squadrons as trainers for deck landing on the proposed aircraft carrier, the Langley. This example bears the McCook Field Number P.170 on its rudder and Army serial 64301 on its fuselage. McCook identified it as a Type XIV with an 80-hp Le Rhone rotary engine.

The Morane-Saulnier Al

<...>

In 1916 Morane-Saulnier converted their Type P two-seat parasol monoplane to a single-seat fighter. The first type conversion left the pilot in his normal position under the wing. The lack of the observer's weight in the rear cockpit made the machine tricky to land. The later conversion shown here had the pilot's cockpit moved aft, the wing lowered and twin synchronised Vickers guns installed with 750 rounds each. The guns were slightly staggered to allow for the feed arrangement and ammunition stowage. The machine's performance was not good enough for production, especially as the Nieuport fighters were in production with the Spad 7 in the immediate future. It was abandoned in December 1916.

<...>

<...>

In 1916 Morane-Saulnier converted their Type P two-seat parasol monoplane to a single-seat fighter. The first type conversion left the pilot in his normal position under the wing. The lack of the observer's weight in the rear cockpit made the machine tricky to land. The later conversion shown here had the pilot's cockpit moved aft, the wing lowered and twin synchronised Vickers guns installed with 750 rounds each. The guns were slightly staggered to allow for the feed arrangement and ammunition stowage. The machine's performance was not good enough for production, especially as the Nieuport fighters were in production with the Spad 7 in the immediate future. It was abandoned in December 1916.

<...>

The Morane-Saulnier exhibit at the Vie Salon Aeronautique held in Paris in December 1919. The Aeroplane issue of 7 January 1920, reported that Aeroplanes Morane-Saulnier, Rue Volta, 3, Puteaux, exhibited four machines - three parasol monoplanes and the fuselage of a Type AN. The Type A.I - a high-speed single-seater fitted with either the 120-h.p. or the 180-h.p. Le Rhone, is also a Parasol... but fitted with a wonderfully complex rigid bracing of steel tube below the wings, cross-braced fore and aft with cable, which must add at least cent, per cent, to the drag loads on the wing structure. The machine is said to be designed for "La Haute Ecole d'Aerobatie" and for rapid transport work, and has made the journey, Paris-Rome - 1,280 km. - in 5 hr. 59 min. non-stop. One is left to wonder how much time would have been saved on the journey had it been fitted with a reasonable bracing system.

The second type of single-seat fighter conversion of the MoS 21 Type P with a Le Rhone 9J nine-cylinder rotary engine. The machine's flying characteristics were probably as tricky as the earlier Morane-Saulnier parasols. The Type P came in three variants. The Type 21 with the casserole type spinner and cowling of the Types N, I, and V with the 110 hp Le Rhone. The Type 24 was a Type P with the 80 hp Le Rhone and smaller spinner. The last was the Type 26 Type P with 110-120 hp Le Rhone and circular cowling similar to the Sopwith Camel and no propeller spinner.

Serial MS 1201; this aircraft does not have the large cone that was used on all Morane-Saulniers. It was riveted on to the airscrew as a permanent attachment and caused problems in storage and transportation.

The Morane-Saulnier Al

In May 1917 the OC of 4th Brigade wrote about a new French Morane, sending silhouettes of the machine to RFC, HQ. The machine had "No bracing wires, but streamline girder tubing. The fuselage tapers to an absolute point at the stern. Estimated speed - 122 mph ground level, and 127 mph at 10,000'." The AI was a remarkable aircraft for its day, not that it was a monoplane in a world of biplanes and triplanes, but for its performance. Morane-Saulnier had built monoplanes before, the first fighter aircraft being a conversion of the Type L monoplane with a machine gun firing through the airscrew that was fitted with deflection wedges. (It was to take Anthony Fokker to merge the interrupter gear with the airframe to build the first true fighter aircraft).

In 1916 Morane-Saulnier converted their Type P two-seat parasol monoplane to a single-seat fighter. The first type conversion left the pilot in his normal position under the wing. The lack of the observer's weight in the rear cockpit made the machine tricky to land. The later conversion shown here had the pilot's cockpit moved aft, the wing lowered and twin synchronised Vickers guns installed with 750 rounds each. The guns were slightly staggered to allow for the feed arrangement and ammunition stowage. The machine's performance was not good enough for production, especially as the Nieuport fighters were in production with the Spad 7 in the immediate future. It was abandoned in December 1916.

The Morane-Saulnier Al was designed around the 150-hp Gnome Monosoupape 9N engine like its contemporary, the Morane-Saulnier AF biplane. The fuselages of the two types resembled each other but they were dimensionally different and the Al was not merely a monoplane version of the AF.

The fuselage, forward of the cockpit, was constructed of perforated metal angle with steel tubing spacer and bracing. A neat cowl with seven ventilation holes, and metal side panels carried the circular cross-section back to the cockpit. Aft the structure was of spruce with piano-wire cross bracing. Wooden formers and stringers gave it a near circular cross-section that tapered to a point. The fuel capacity was the same as that of the AF, three tanks of 66, 47 and 30 litres. Oil was carried in two tanks of 8 and 12 litres. A standard undercarriage was fitted with as central "V" when viewed from the front. The fulcrum of the two half-axles of the undercarriage were braced by struts to the upper ends of the forward legs of the vee undercarriage struts in typical Morane-Saulnier fashion. 650 x 80 tyres were fitted.

The tail unit featured a horn balanced rudder with fin. The tailplane and elevators were similar to those of the AF but of different proportions.

The one-piece wing was swept back to an angle of 5 1/2 deg and had raked tips. The wing was of conventional wooden construction with wood spars, ribs, compression members and doped fabric covering. There was a compression strut on the centreline and four in each half wing. The balanced ailerons were attached to an auxiliary spar a short distance behind the rear spar. The ailerons were controlled by torque tubes, somewhat similar to those used by Nieuport. No cabane was fitted to brace the wing from above. The bracing consisted of steel tubes underneath from a point on the outermost compression member, giving about one third of the wing as overhang, to the bottom of the fuselage. An intermediate Warren truss of struts took the loads. The midpoint of the lift struts was connected by a compression strut that was stayed to the wings. Further struts from the upper longerons terminated at the same point on the wing. There was a large semi-circular cut-out in the trailing edge at the cockpit. The tail presented a very small blind area, the control also being by torque tubes fitted with ball bearings. The pilot had excellent visibility.

A tail skid with a spiral spring was placed inside the rudder post. A single strut each side braced the tailplane. A British report noted that there was an excellent hand grip fitted to the joy stick that might be of interest for adoption for other machines.

The machine gave a factor of safety of 8.5 under sand load testing.

Pilot Eugene Gilbert tested the Al for the S.T.Ae on 7, 8 and 9 August 1917, at Villacoublay, where it recorded an excellent performance. 3,000 metres was reached in 7 min 45 sec and the speed at this altitude was 215 km/hr. On the 9th further trials by Gilbert, this time with a Levasseur airscrew, gave better figures with a speed of 216 km/hr at 3,000 metres, that altitude being reached in 7 min 25 sec.

A US Army report of the trials gave the following results:

Morane Parasol, 170 H.P. Monosoupape (Monoplane).

Total weight of machine... 1,420 lbs

Speed at 6,500 ft... 136 mph

Speed at 10,000 ft... 133 mph

Speed at 15,000 ft... 127.5 mph

Climb to 6.500 ft... 4 min 20 sec

Climb to 10,000 ft... 7 min 40 sec

Climb to 15,000 ft... 13 min 40 sec

Ceiling 23,000 ft

The above tests were carried out with one gun. For these tests the Al had a dummy machine gun fitted with ballast to make up the weight. The machine could be fitted with one synchronised machine gun and 500 rounds of ammunition, or two guns and 800 rounds. The S.F.A. gave the designations MoS.27.C1 to the single-gun version and MoS.29.C1 to the two-gun model.

Pilots found the machine responsive. Lt Rene Labouchere who performed handling testing on 11 September being enthusiastic at its performance. The machine was extremely manoeuvrable and responsive. It had very good stability but the takeoff run was somewhat long. The pilot's position was stated to be good. Visibility was excellent unequalled by any contemporary fighter. There was some play in the lateral controls and some small oil leaks. On the 13th it was tested at 5,000 metres by Labouchere, the aircraft retaining its manoeuvrability well at this altitude.

A two-gun Al was tested by Gilbert on 8 September. In addition to the extra gun this version had slightly enlarged tail surfaces. The load was 260 kg. The machines climbing performance suffered but the aircraft's overall performance and manoeuvrability were preserved. The pilot expressing the same views as for the single-gun machine.

The US Army's "Review of French Airplanes" of 23 October 1917, reported that the Spad Monocoque, Morane Biplane and Morane Monoplane, all of which are equipped with the Gnome 150 H.P. Monosoupape engine, have finished their tests.

The same report then recorded that the Morane Monoplane was tested a long time ago, but another test was made on September 8, 1917. This test was made with both single and double machine guns. The results were perfectly satisfactory. A test at high altitude has been made to verify the running of the engine at high altitudes, and also to experiment with an oxygen apparatus. In this test the airplane was actually flown at an altitude of 26,500 feet. In the test for altitude the Morane machine climbed to 2,000 metres in 5 minutes 5 seconds; 3,000 metres in 8’ 40” and 5,000 metres in 19 minutes. The speed at 2,000 metres was 135 M.P.H.; at 3,000 metres 133 1/2 M.P.H. and at 5,000 metres 124 M.P.H.

Under the heading Morane Monoplane Superior the report concluded that beyond a doubt the Morane Monoplane is the superior airplane with the Gnome Monosoupape 150 H.P. Engine. Furthermore, the factor of safety of this airplane is 8 1/2, which is considerably better than other airplanes of this type. Its stability is superior and its visibility is wonderfully excellent.

The British agreed that the (v)isibility from the pilot’s seat is excellent for both downwards and forwards, as the pilot’s eyes are only two or three inches below the level of the plane.