Журнал Flight

Flight, January 2, 1909

THE WRIGHT AND VOISIN TYPES OF FLYING MACHINE.

A COMPARISON BY F. W. LANCHESTER.

The Wright Machine - Origin and Description.

The Wright machine can, metaphorically speaking, trace its ancestry back to the gliding apparatus of Otto Lilienthal; according to Gustave Lilienthal (brother of the famous aeronaut) two Lilienthal machines were sent to the United States, one to Octave Chanute, the other to Herring; Chanute and Herring are said to have been associated in their experimental work. The gliding machine, originated by Lilienthal, was improved, especially as to its structural features and its method of control, successively by Chanute and the Brothers Wright, until the latter, by the addition of a light weight petrol motor and screw propellers, achieved, for the first time in history, free flight in a man-bearing machine propelled by its own motive power.

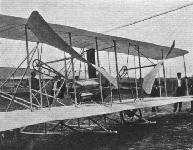

The Wright machine of the present day weighs complete, when mounted by aeronaut, 1,100 lbs. (500 kilogs.), and has a total supporting surface measuring approximately 500 sq. ft., the ordinary maximum velocity of flight is 40 miles per hour or 58 ft. per sec. (= 64 kiloms. per hour). The aerofoil consists of two equal superposed members of 250 sq. ft. each, the aspect ratio (lateral dimension in terms of fore and aft), is 6'2, the plan form is nearly rectangular, the extreme ends only being partially cut away and rounded off. The auxiliary surfaces consist of a double horizontal rudder placed in front, and a double vertical rudder astern, also two small vertical fixed fins of half-moon shape, placed between the members of the horizontal rudder. The total area of these auxiliary surfaces is about 3 of that of the aerofoil, or say 150 sq. ft.

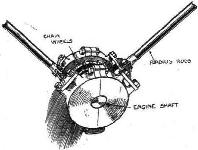

The Wright machine is propelled by two screws of 8 ft. 6 in. diameter (2-6 metres), and so far as the author has been able to estimate the effective pitch is somewhat greater, being about 9 ft. or 9 ft. 6 ins. These propellers are mounted on parallel shafts 11 ft. 6 ins. (3'5 metres) apart, and are driven in opposite directions by chains direct from the motor shaft, one chain being crossed. The number of teeth of the sprocket-wheels, counted by the author, gave the gear ratio 10 : 33.

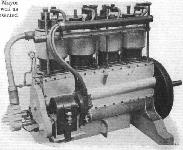

The motor is of the 4-cyl. vertical type, the cylinder dimensions being variously given as from 106 to 108 mm. diameter by 100 to 102 mm. stroke, the probable dimensions being in inches 4 1/4 in. by 4 in. The total weight of the motor is reported to be 200 lbs. (90 kilogs.), and its power is given as 24 b.h.p. at a normal speed of 1,200 revs, per min. According to another source of information it is capable at a speed of 1,400 revs, of developing 34 b.h.p.; the two statements do not altogether agree.

In conversation, the author understood Mr. Wright to say that he could fly with as little as 15 or 16-h.p., and that his reserve of power when unaccompanied amounted to 40 per cent. His gliding angle he said was about 7 degrees.

Flight, January 9, 1909

THE FIRST PARIS AERONAUTICAL SALON.

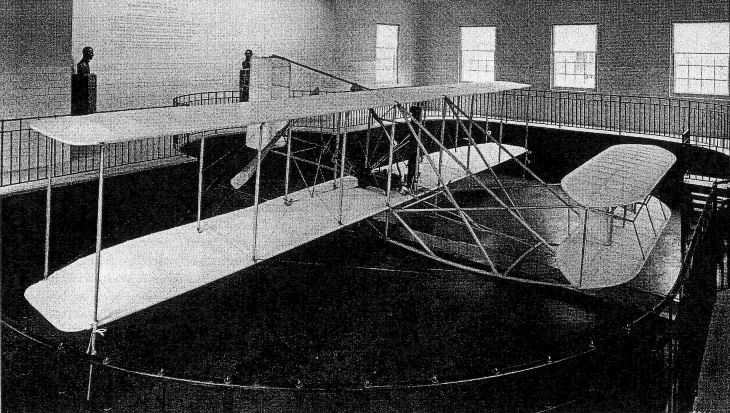

"Wright."

Full-sized model, not intended for trial purposes, constructed by Chantiers de France at Dunkirk for the Comp. Generale de Navigation Aerienne, of which M. Lazare Weiller - who bought the French patents from the Wrights - is a director. The sales are controlled by M. Michel Clemenceau - son of the well-known Minister - who states that he has already disposed of no fewer than thirty two machines. The first models are to be ready in February, and will be tested at Cannes, where M.Clemenceau has selected his trial ground. The machines are to be fitted with 25-h.p. Wright engines, made by Messrs. Bariquand and Marre; the transmission is by chains, one crossed and the other direct, to two wooden propellers, as on Wright's own machine. The control is by two levers. One lever, that on the pilot's right, is moved sideways to steer, by the rudder and by warping the wings, while another lever to the left controls the elevator. The warping is done by diagonal wires attached to the rear corners of both main planes, and the maximum deflection is about 15 cms. Both planes warp the same way at the same extremity of the machine, but opposite extremities move in contrary directions. The front edges of both planes are unaffected except, perhaps, indirectly.

Flight, February 6, 1909

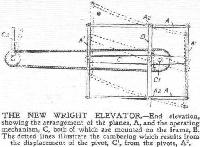

WRIGHT BROTHERS' NEW ELEVATOR.

THE Brothers Wright have had granted to them in America a patent for a new elevator, which was filed as an improvement on their patent of May 22nd, 1906. The idea embodied in the new invention is that of rendering the elevator more effective by causing its surface to automatically camber as it moves from its normal position. The accompanying drawing, reproduced from the specification, shows very clearly a method of putting the principle in practice.

The elevator illustrated is of the biplane type, having two simple flat surfaces, A, coupled together by hinged struts, A', and pivoted at A3 to a rigid vertical frame, B. Fastened to the struts, A1, is a longitudinal beam, C, which is pivoted about a centre, C, so that it can be swung into any position by suitable mechanism operated from the lever, C3. The support for the pivot, C1, is provided by the frame, B, but it will be noticed that its centre is not in the same plane as the pivots, A2, which form the attachment of the elevator surfaces. Consequently, while the surfaces, A, remain perfectly flat in their normal horizontal position, they become cambered so soon as they are either tilted or dipped by the action of the operating mechanism. It will be noticed, moreover, that the surfaces are not pivoted midway between their front and rear edges, and consequently the inclination of the rear part of the frame is greater than that in front.

Flight, February 27, 1909

King Alfonso and the Wrights.

So His Majesty Alfonso XIII of Spain did not make a flight with the Wrights after all, for, like a good many married men of less august degree, he found himself bound, so report has it, by a promise to Queen Eugenie Victoria that he would upon this occasion sink his personal desires in deference to her anxious fears for his safety. There is no doubt, however, that His Majesty managed to impart a great deal of interest into his part of spectator when he motored over to see Wilbur Wright fly, as he did on Saturday of last week, February 20th. Nothing contented him but that he should have the whole mechanism and the operation thereof fully explained to him, and that he might get a better appreciation of the reality of things, he absorbed his lesson seated on the machine with Wright beside him. The visit was paid to the aerodrome quite early in the morning; in fact, the King left his hotel soon after nine o'clock, motoring over in a 150-h.p. Delahaye belonging to M. Jose Quinones de Leon, the exhibition flights being concluded by half-past ten. Wilbur Wright elected to make a flight directly His Majesty arrived, and he remained in the air for 28 mins.; half of this time he was actually out of sight, and some of the spectators began to express fears of a mishap. Before landing, Wilbur Wright executed several figures of eight in front of the King, who was undoubtedly immensely impressed by the spectacle, and wholeheartedly congratulated the American on his wonderful accomplishment. His Majesty expressed a wish to see a passenger flight, and Wilbur Wright thereupon invited the Count de Lambert to accompany him on a flight which lasted twenty minutes. Before leaving the Pont Long ground, His Majesty honoured the Wrights by an invitation to lunch with him at the hotel, and it is said that they are to be created Commanders of the Order of Isabel the Catholic. An officer of the Spanish Army will, in all probability, be entered as a pupil of the Brothers Wright, as the Spanish Government is said to contemplate purchasing one of these machines.

Flight, March 20, 1909

HOW WILBUR WRIGHT RIDES THE WIND.

By H. MASSAC BUIST.

WE had turned the car off the road into the enclosure at Pont Long and were in the act of alighting to thread our way out of the long string of other vehicles, the owners of which had preceded us on to the practice ground, when a whirring noise overhead and the casting of a shadow for an instant caused us to gaze upwards. At that moment the 40-foot broad biplane, the appearance of which has been rendered familiar throughout the world by photographic and other reproductions innumerable, swept over our heads not more than 20 feet above the tops of the cars. There were two men on the machine, and it was the pupil, the Comte de Lambert, who was controlling the machine. It was his eighteenth lesson, and at that time he had been practising for a total of not more than four hours. Yet the master seated beside him was allowing him not to cross the line of vehicles, but to fly deliberately over and along it, so that it would have been absolutely impossible to have alighted quickly without disaster.

That was my first glimpse of the Wright aeroplane in actual flight. By the time we had walked a couple of hundred yards or so to the huge brown shed the lesson had been voluntarily concluded by bringing the machine to earth hard by the starting rail, in readiness to be mounted and launched on another flight with another pupil aboard.

What happens when Wilbur Wright wants to fly? Perhaps the best course will be to endeavour to give a more or less consecutive account of the processes gone through. When the big doors of the reddish-brown shed have been rolled back, the four-year-old aeroplane is revealed, with all the woodwork rendered resplendent with aluminium paint, with which the propellers are also treated. This is not for ornament, but is a precautionary measure, because long use in all sorts of weathers having rendered the woodwork dirty, it has been found that the coating of aluminium paint serves the dual purpose of a preservative and a means of throwing any cracks or fractures into relief. The back of the machine faces the opening of the shed, and as soon as the biplane, which is mounted on two wheels, is drawn into the open, one notices that the canvas is worn and torn, soiled and burnt, patched and stained, and tattooed with tintacks. There are stretches as big as a towel that have been sown and tacked on because the original fabric has been destroyed by one means or another. On the other hand, there are bits in the canvas that have evidently been burnt through by placing a lighted cigar or cigarette on them. Such trifles, however, do not worry the Wrights, for they do not fly by a hair's breadth, as it were, but in virtue of having devised a system that works.

As you follow the little party of half-a-dozen or so who push the weather-stained machine to the starting rail, one or two things strike you as being rather peculiar. In the first place, you notice that it is being bumped about a good bit. So you glance over the Champ d'Aviation. Regarded as an expanse of over four miles in circumference, it certainly answers to the description of flat land; but when any part of it is considered in detail, it is impossible to discover a single square yard of level. It is composed of a series of close-set hummocks or mounds, some almost hemispherical and anything from a foot to 20 ins. in diameter and from 6 ins. to 16 ins. high. Certainly no aeroplane fitted with wheels could be run over or let down on such country. Accordingly, it is not surprising to learn that the Pau authorities have leased another and smoother ground nearer the city for the use of those experimenters whose flying machines are fitted with wheels. Yet the Wright aeroplane has not a single spring, pneumatic cushion or other shock-absorber of any sort, whereas all the wheel machines employ means of deadening the shock of landing even on smooth ground.

When the American aeroplane is placed on the starting-rail, an examination of it proves that the reports that have been put abroad to the effect that it is crudely built are not borne out in fact. The design is extremely simple and bold, and there is not the slightest hint of "finnikiness" anywhere; but the work is all quite well finished. Indeed, the only feature that can have given rise to so utterly misleading a report is the evidences of age and use that the machine bears. Truth to tell, it is a wonderfully handy piece of mechanism, for quite apart from the use that has been made of it, there is no brittle thing that can be hurt by handling, as the French machines evidently are, to judge by the black looks you receive if you lay a finger on them. No one minds in the least if you lend a hand in manoeuvring the Wright machine on to the starting-rail; nor does anybody instruct you to catch hold of it here and not to touch it there.

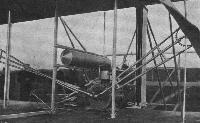

The much discussed starting apparatus, that has been dispensed with on more than one occasion, though never publicly, is a light version of the ancient Roman instrument for hurling missiles. Should need arise, a couple of men can move it from one part of the ground to another. The 75-foot rail is the only part that needs to be changed. It is laid in one or other of three directions, according to the wind, the work of changing it over occupying about twelve minutes, so that it is a common thing to hear Wilbur Wright instruct his mechanic to have the rail changed to another direction immediately he has launched the aeroplane in flight, so that everything may be in readiness by the time he has given one pupil a lesson. The rail itself is a very flat piece of iron, laid on a piece of wood, that is admirably illustrated in the photograph published on page 128 (March 6th). The woodwork raises the rail to approximately nine inches off the ground. Only two ball-bearing wheels, made solid and of about three inches in diameter, are employed. They are set one in front of the other, bicycle fashion, and spaced about a foot apart; very slight flanges are furnished to keep the wheels on the rail. The starting bogie consists of a beam just long enough to reach from one runner of the aeroplane to the other, and affixed midway, in swivel fashion, to the support on which the wheels are mounted, so that when on the rail the aeroplane can be turned round with the utmost ease.

The placing of the machine on the starting bogie occupies scarcely more than a minute, one of the single wheel trolleys on which the machine is drawn about the field, being left under the planes during the preliminary proceedings- that the aeroplane may remain stable. If it chances to be your first visit to Pau, you may doubt if Mr. Wright will ever go up, so long do the preparations usually take him. The brothers and their assistants never seem to be working against time. But if you had been to Pont Long you would be well aware that there is only one signal which Mr. Wright gives, and which invariably means that a flight is about to commence. Until the starting-weights begin to be raised off the ground you never know whether he will order the machine back to the shed without making a flight. But the moment his willing helpers begin pulling at the rope, you may rest assured that within the next ten minutes the machine will be rushing along the starting-rail.

Oil-can in hand, with pockets bulging with "waste" and twine, a screw-driver, a wrench, and other less indispensable tools, Wilbur Wright, clad in a suit the trousers of which have plainly long been strangers to the press, and having a motor cyclist's type of leather coat over his jacket, usually begins proceedings by giving a rapid glance over the whole machine. Then he will climb over the slack tangentially-set wires and stand in front of the machine, brother Orville joining him. "Right," he will say to the mechanics, one of whom stands behind each screw. "One, two, three," is the signal, at which they put pressure on the handiest blade, thereby turning the engine over, two or three attempts being usually needed to start the motor. The men have to be alert to get their hands clear of the propellers the instant they begin to turn, at which moment some onlookers have usually to be warned to move out of the line of the revolving blades, which are so broad at the extremities that being six feet in diameter, and turning at not more than 450 revs, a min., can be just detected if one fixes the gaze on a given spot above the upper plane. To obviate the likelihood of the blades ever striking the ground, they have been raised slightly above their former position, so that they extend above the upper plane and do not reach down to the lower one. When first tried in the new position, it was found there was an inclination to thrust the machine downwards, but by altering the range of curvature of the front flexing planes for controlling the flight path, and by making sundry other minor adjustments, matters were found to work satisfactorily. The relatively enormous size of these propellers by comparison with the French ones, as well in the matter of diameter as of surface, is extraordinary, quite apart from the great pitch that they have and from the fact that two propellers revolving in opposite directions are employed in place of one as generally exploited by the French school, many of the foremost members of which, however, are now inclining to use two propellers, even as in biplanes they are having to space them two metres apart, which the Wrights all along maintained was the closest possible distance without losing efficiency through the compression of the air by the bearing of the upper plane being communicated to the upper surface of the lower plane. The relatively little disturbance of air caused by the revolving Wright propellers cannot but impress anybody who has watched other machines. The Americans seem to disturb only that amount of air which is necessary for the actual propulsion of their machine, there being seemingly no churning to waste.

Anybody accustomed to seeing a petrol motor run in a chassis, or on a bench, receives a shock on beholding the engine start in the Wright aeroplane. "Shiver my timbers!" you exclaim, instinctively, as it appears to bounce and wriggle about on the pliant frame. When it is running slowly at the start, it seems inevitable that its breaking adrift can be a matter of minutes only. Yet if you try to follow the vibrations to any extremity of the machine you will fail to do so. The shocks caused by the power pulses are quite absorbed before they reach the extremities of the main planes, or the flight path control planes forward, or the vertical rudders behind. Then it begins to dawn on you that this non-rigid type of biplane, with its extraordinarily simple and ingenious design for resisting shocks at those points where they are likely to be received, has really no need of coil springs, pneumatic shock-dampers, combinations of levers and other guess contrivances. The scheme allows plenty of play, and you do not see anybody making wires taut, as in the case of the rigid French-built machines.

Having run the motor for a while, during which he has been busy with an oil-can, Wilbur Wright may ask for some hot water. "Don't suppose there's any," says the mechanic, strolling off. "What about that they were making tea with?" shouts Wilbur after him. "Go and ask the chef fellow." Meantime he gets busy with a spanner, hangs his watch up on one of the struts that heads from the runners to the upper main plane, and calls out, "Smoke, somebody, please." Immediately half-a-dozen responsive puffs enable him to see the exact extent to which the wind has veered round during his testing. The hot water being now forthcoming, and thick grease having been stuffed into the guide tubes through which the propeller chains pass, Wilbur strides down the starting-rail in his tremendously energetic manner to the point where the rope tackle runs round the pulley wheel. Now you may come forward and lend a hand at the hauling, even as Mr. A. J. Balfour has delighted to do. As the weight begins to rise, you will hear a murmur from the roadway where the thousands who have not ten francs to spare for the privilege of entering the enclosed ground wait patiently, knowing that once the craft has been launched in the air, they will see its performances as well as any of the privileged ones.

Wilbur walks slowly back along the rail with the releasing catch mechanism in his hand. Presently he climbs under the aeroplane and sets everything himself, nobody else ever being entrusted with this important business. It is not void of risk, though the only awkward incident that has ever occurred in this connection was when something missed, and Orville found himself and the machine rushing down the rail at forty miles an hour with the motor working and nobody aboard. That was in the early days in America. During the scurry, he managed to climb to the motor and stop it, but suffered a wrench to his shoulder that left it weak and stiff for a matter of eighteen months thereafter.

"Who tied this up" asks Wilbur, pointing to something as he climbs out from under the machine. A mechanic having signified that he is responsible, also that he had no proper string. "Never you do that again," says Wilbur, adding, "Always go about with a ball of twine in your pocket."Producing one from his own, he calls over his shoulder, "Mr. Tissandier - you're elected," whereupon the famous little amateur balloonist quickly buttons up his coat, and seats himself in the place immediately beside the motor. Straightening his back as a relief from the bending posture, Wilbur jerks a glance towards the horizon as though actually viewing the wind, then, buttoning up his short leather overcoat, he casts a final rapid glance over the machine, from which Orville has never taken his eyes all this while, for both brothers are extremely careful that everything shall be absolutely right before the launching.

An instant later Wilbur has taken his seat, with "Little Tissandier" between himself and the motor. He tugs the familiar old cap tight and low over his eyes, signals the mechanic to draw a supporting plank away from under the plane, grasps the long lever for controlling the elevation of the front planes with the left hand, feels for the release-catch with his right hand between his legs, nods to the mechanic to let go his hold of the wing by which he has been easily keeping the machine balanced, gives the release-catch a sudden jerk, and, with a whirr, the gigantic half-ton glider has started down the rail at 40 miles an hour. Before it has traversed the entire 75 feet it has passed the spot where the pulley-catch drops free. The instant it reaches the end of the rail. Wilbur changes his crouching attitude by throwing back his body to get the maximum power for pulling back the lever with his left hand to the utmost extent, so that the machine rises slightly as it leaves the rail, the bogie tumbling free on to the ground below at that instant.

But the machine rarely rises into free flight immediately on clearing the rail; instead, it usually scrapes along the ground for 40 ft. or 50 ft., or even more, bumping from hummock to hummock, until you would declare it could not possibly rise, if only on account of the presumable braking effect. But the idea has scarcely come in mind to you than you perceive the machine to take a distinct upward set, whereupon it rises obviously clear of the ground, and there is no longer any doubt that the craft is actually flying. Having given the engine a little relief by allowing the machine to fly level for a few moments thereafter - for the motor only develops 24-h.p. at starting and lifts a half-ton machine and two men, which is assuredly a degree of proficiency out and away beyond the capacity of any other type of aeroplane at present known - it is again made to rise to any height between 16 ft. and 30 ft., for, with pupils aboard, it is usually kept within the bounds of the ground, and there is nothing like an aeroplane in flight for eating up distance, because it can travel straight. So, in a little you will espy the machine developing a cant, and as it leans over just like a bird, it will turn with equal ease and in relatively as small a compass by the warping of the outermost quarters of the two main planes to an extent that cannot be detected by the eye unless the wings chance to be so flexed, in opposite directions in synchronism, when the machine is brought to a standstill. In one of the illustrations in this issue, Mr. Griffith Brewer, who represents the Wright interests in this country, has shown the machine in the act of making a turn, one of the pupils being responsible for actuating the gauchissement, as the French term the wing flexing. That accounts for the comparatively slight tilt, for the pupils do not turn abruptly right away, as the Wrights can do by making the machine heel over to an angle of 450. This is something so startling to state that perhaps one is not completely convinced of the fact until one's own eyes have beheld it. The proceeding, however, is no out of the ordinary one, as a visit to Pont Long would quickly convince you. I have never seen a photograph taken close to the aeroplane, and depicting it tilting over to the full extent, yet I should fancy that, were one procurable, it would be the most picturesque aspect of an aeroplane flight possible to snapshot. But there are many difficulties in the way of getting such a snapshot, for you never know whereabouts Wilbur Wright will make one of his amazingly sudden turns; also, he does not allow photographers to go wandering about the field during flights.

The exigencies of space are imperative, therefore many aspects of the amazing machine in flight cannot be discussed on the present occasion, when I will conclude by indicating how the pupils are taught. In the first place, the Wright machine is unique in that no learner need risk his life by finding out how to fly "all on his own." Instead, you get aboard in an ample seat beside a man who knows how to handle the machine, and learn your business as safely as though you were being taught how to drive a motor car.

Has it ever struck you that MM. de Lambert, Tissandier, and Gerardville are learning how to drive the Wright aeroplane left-handed? That is because only one of the levers is duplicated, namely, that for actuating the front minor planes, which Wilbur Wright holds in his left hand, and the pair of which the pupil grasps with his right hand. Between them is the single lever for controlling the wing flexing and the rudders. It has a movement in all four directions and takes the place of two independent levers which Orville Wright prefers to employ. At first the pupil is only allowed to try to control the flight path by the use of the lever, which he grasps with his right hand. At the sixth lesson - they average about twenty minutes each - a quick learner like "Little Tissandier" will begin to try the gauchissement. This is to say, he places his left hand on top of Wilbur's right, and first feels, then tries to make the movements. In this position the elbows of master and pupil are in touch, so that the instant the teacher nudges to learner the latter desists, giving over all control to his instructor. That way safety lies. The rush of wind past the ears renders speaking impossible.

And you may say that there is nothing more in learning to aeroplane than that and handling it as a glider without power applied. The pupils all tell you the machine is amazingly simple to handle. You may judge that from the fact that when he came to fly at Le Mans, Wilbur Wright had not had as much experience with a power-driven aeroplane as the Comte de Lambert had at his eighteenth lesson, by which time he had handled it for a total of about four hours only. In those circumstances is it any marvel that Wilbur's flight path was somewhat undulating when he began at Le Mans, feeling very nervous, very ill, and with the whole of his reputation at stake? Would you not expect to "wobble" when riding a bicycle for the first time in eighteen months, particularly if you were the first man who had ever balanced on one, so that you had to find out everything for yourself?

But Wilbur Wright's first three pupils will not learn the machine left-handed, for they will sit in Wilbur's seat. And presently MM. de Lambert, Tissandier, and Gerardville will teach each the other how to handle the aeroplane from Wilbur's seat, so that in time they will be ambidextrous at the business.

Of the niceties of manoeuvring in mid-air, the consummate ease with which the machine can become lost to view when scouting, the gracefulness of its circling and tiltings, its rises and its dips, the matter-of-courseness with which it is put to fly a measured kilom. just as you would drive a motor car past a mark; its excursions over woods and crowds of carriages and onlookers, the accuracy of its alighting at the very doors of the aerodock or beside the starting rail, and the astounding smoothness of its landings, are matters that must be discussed anon.

Flight, May 1, 1909.

PRESENT STATUS OF MILITARY AERONAUTICS.

By GEORGE O. SQUIER, Ph.D., Major, Signal Corps, U.S. Army.

REPRESENTATIVE AEROPLANES OF VARIOUS TYPES.

The Wright Brothers' Aeroplane (Figs. 14 to 23).

The general conditions under which the Wright machine was built for the Government were, that it should develop a speed of at least 36 miles per hour, and in its trial flights remain continuously in the air for at least 1 hour. It was designed to carry two persons having a combined weight of 350 lbs. and also sufficient fuel for a flight of 125 miles. The trials at Fort Meyer, Virginia, in September of 1908, indicated that the machine was able to fulfil the requirements of the Government specifications.

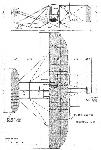

The aeroplane has two superposed main surfaces 6 ft. apart with a spread of 40 ft. and a distance of .6J ft. from front to rear. The area of this double supporting surface is about 500 sq. ft. The surfaces are so constructed that their extremities may be warped at the will of the operator.

A horizontal rudder of two superposed main surfaces, about 15 ft. long and 3 ft. wide, is placed in front of the main surfaces. Behind the main planes is a vertical rudder formed of two surfaces trussed together about 5 1/2 ft. long and I ft. wide. The auxiliary surfaces, and the mechanism controlling the warping of the main surfaces, are operated by three levers.

The motor, which was designed by the Wright Brothers, has four cylinders and is water-cooled. It develops about 25-h.p. at 1,400 r.p.m. There are two wooden propellers 8? ft. in diameter, which are designed to run at about 400 r.p.m. The machine is supported on two runners, and weighs about 800 lbs. A monorail is used in starting.

The Wright machine has attained an estimated maximum speed of about 40 miles per hour. On September 12th, a few days before the accident which wrecked the machine, a record flight of 1h. 14m. 20s. was made at Fort Meyer, Virginia. Since that date Wilbur Wright, at Le Mans, France, has made better records; on one occasion remaining in the air for more than an hour and a half with a passenger.

A reference to the attached illustrations of this machine will show its details, its method of starting, and its appearance in flight.

Flight, September 11, 1909

Orville Wright Flies 55 minutes at Berlin.

LAST Saturday, Orville Wright had his flyer out again on the Tempelhof field and flew for 19 minutes. There was not a very large attendance of the public, probably due to the fact that Orville Wright did not take the air on the two previous days, when expectant crowds had been compelled to retire with their disappointment. On Tuesday afternoon a most successful flight, lasting 55 minutes, was witnessed by a very large concourse of people, while on Wednesday two trials were made, one of 35 mins. 56 secs., and a second of 17 mins., with Capt. Hildebrandt as passenger.

Flight, October 23, 1909

FLYING ROUND THE EIFFEL TOWER.

JUST a glimpse of future possibilities of flight was accorded to Parisians on Monday, when Count Lambert demonstrated his complete confidence in his Wright flyer by leaving the Juvisy aerodrome and flying over Paris, and round, or rather circling above, the Eiffel Tower. He left the Juvisy aerodrome at 4.37, after rising by circling round till a height of well over 150 metres had been reached, and steered straight for the Eiffel Tower, steadily rising meanwhile.

This reached, he turned round at an estimated height of about 100 metres above the Tower, which itself is 300 metres high. Only two persons, it appears, were aware of Count Lambert's intentions. No small wonder, therefore, was evinced when the Count was seen by the Juvisy crowd to dart away beyond the outskirts of the aerodrome and disappear towards Paris. Interested watchers not unnaturally supposed that he was simply indulging in a little cross-country flight of a couple of kiloms. to give a bit of sensation to the day's programme. But as time passed and there were no signs of his return, interest turned to anxiety for his safety. Nothing short of alarm soon arose, until at length, about half past five, he was once more discerned. A huge cheer went up, speedily followed by the calmest and most collected descent by the Count within 5 metres of his shed. His time for the round trip of about 30 miles was 59 mins. 39 secs.,and needless to say, on his return he was accorded a tremendous reception, in which Orville Wright, who happened to be present, joined. At a meeting held immediately afterwards it was decided to award a gold medal to Count Lambert, and M. Deutsch de la Meurthe announced that he would give 50,000 frs. to the Society d' Encouragement d'Aviation as an acknowledgment of what they had done at Juvisy.

Flight, January 8, 1910

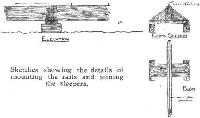

WRIGHT GLIDER LAUNCHING APPARATUS.

IN connection with the description, with scale drawings, of the full-size Wright glider in our issues of September 18th and 25 th last, we have been repeatedly asked for details regarding the starting arrangements suitable for such a glider, and now through the courtesy of Messrs. T. W. K. Clarke and Co., we are able to give them. From the side elevation it will be seen that the starting rail itself is about 90 ft. long, while the derrick is 15 ft. high. The actual arrangement shown was that constructed for Mr. Ogilvie's glider at Camber, and there the derrick was made from such timber as was available on the spot, and the starting weight originally consisted of a bag containing the earth excavated from below the derrick. Later this was changed to a number of metal discs up to a total weight of 250 lbs.

The rail itself, consisting of "T" iron in 15 ft. lengths mounted on long wooden blocks, was laid on a slope of about 1 in 10, and to compensate for the irregularity of the hillside a clearance of 1/4 in. was allowed at the joints. Owing to the long grass present in this particular case, it was found necessary to put additional wood blocks 6 ins. deep under the sleepers. The actual details of construction are clearly shown in the three small sketches, while the precise arrangement of the starting rope can be followed from the side elevation.

In launching, the glider is placed in position close up to the derrick (as shown in the drawing), with its two small grooved trolley wheels resting on the "T" iron rail; the 250 lbs. weight is then raised by hauling on the free end of the rope, which terminates in an iron ring; this is then slipped over a downwards-pointing iron hook, carried on the end of a wooden bar fixed in front between the skids of the machine. At first a Manila rope, about 11 ins. circumference, was employed, but a wire cable has since been substituted.

The glider is balanced laterally on the mono-rail by hand on each side (when in motion this is effected by the action of the wing-warping lever), and is held back by hand against the pull of the rope. As soon as the pilot is ready the machine is released, the weight falls, and the glider is shot forward along the starting rail.

When there is a good wind, the machine usually rises into the air after traversing only about 30 ft. of the rail.

Flight, January 29, 1910

FIRST FLIGHT IN AUSTRALIA.

ON December 9th, at the Victoria Park Racecourse, Sydney, N.S.W., Mr. Colin Defries, as we recorded at the time, accomplished the first flight ever made on an aeroplane in Australia, although a heavy S.W. gale was blowing at the time.

Further particulars and photographs are now to hand from Mr. D. C. Defries, the young aviator's - he is twenty-five years of age - father. The aeroplane - a Wilbur Wright - which was mounted on a superstructure carried on three pneumatic wheels (instead of going off from the starting platform usual with these machines), rose to a height of about 35 ft., and covered about a mile in 1 1/4 mins., when the aviator had to come to earth as the motor was performing badly, due, it was found, to faulty sparking plugs.

The event created a lot of excitement, and there was a large crowd on the ground.

On the following day another short flight was accomplished, when Mr. Defries took up a passenger - Mr. C. S. Magennis, a well-known Australian mining engineer - and although a long flight was again impossible on account of the engine not running perfectly, enough was done to prove his complete mastery of the aeroplane.

Mr. Colin Defries was educated at St. Paul's College, at Darmstadt, and University College, London, and received his practical engineering training at the works of Messrs. Bruce, Peebles, and Co., Edinburgh. Previous to going to Australia, where he is sole agent for several well-known motor cars, he had made a considerable reputation in the motor world, and amongst other races drove in the Grand Prix and Kaiserpreis in 1907, and on each occasion was the only Englishman who finished.

Flight, March 12, 1910

THE WRIGHT BIPLANE.

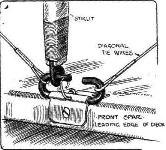

EVERYONE who has followed the history of the development of the Wright biplane is familiar with the fact that it was evolved from a glider of almost identical design although different in actual dimensions. In having very fully described the construction and operation of a Wright glider in FLIGHT, Vol. I, page 568, therefore, we have already covered a great deal of the ground that would otherwise afford subject matter for the present article; in fact, the accompanying remarks and illustrations must largely be regarded as supplementary to the previous description. We publish on the opposite page a plan and elevation of the machine, and there appear herewith three sketches of details that we have not hitherto fully illustrated. One shows the bracing of the rudder, another shows the attachment of the vertical struts to the main spars, and the third illustrates how the radius-rods between the chain-brackets are coupled up to cases containing ball-bearings that ride upon the crank-shaft.

The general construction of the machine is much the same as the glider that we have already described. Each main deck is built up of two transverse spars placed four feet apart and joined at intervals of about twelve inches by specially shaped rib members that project behind the rear spar and form the flexible trailing edge that is such an important feature of these machines. Two points of especial interest about the arrangement of the ribs are that those near the extremities of the spar are curtailed and are also less in camber than those in the centre, and that the two main spars themselves lie at the same level above the ground, so that it is entirely due to the trailing portion of the decks that the chord has any angle of incidence at all.

The flattening and curtailing of the ribs in the vicinity of the extremities of the decks reduces the intensity of the aerodynamic disturbances, and tends thereby to avoid loss of efficiency by reducing the lateral spewing of the air from beneath the decks.

The horizontal position of a chord drawn between the two main spars is of particular interest because it emphasises the practical application of the principle of the dipping front edge. The machine in horizontal flight proceeds through the air with the chord between the two main spars in a horizontal position, consequently the leading edge dips down instead of being tangential to the line of flight.

Lanchester's theory of the dipping front edge - the discovery of which, by the way, is due to Phillips, who describes this peculiarity of a bird's wing in his patent No. 13,768 of 1884 - is that an aeroplane in horizontal flight is virtually always falling through the air and is, therefore, always meeting an up-current. This up-current, when compounded with the horizontal motion of the machine, gives to the relative wind an actual obliquely upward trend, and it is to this slope that the leading edge of the aeroplane should be tangential in order that it may receive the air without shock. Having received the air in this way the cambered surface of the aeroplane proceeds to change the upward motion of the air into downward motion, and this is done gradually by the gentle camber of the decks. By the time that the molecules of air have reached the rear spar their direction of motion has been entirely reversed, and this has taken place, it will be seen, without reference to the trailing portions of the decks or to the question of the amount of the angle of incidence represented by the chord between the leading and trailing edges of the complete deck.

By its action of continuously changing the direction of flow of a stream of air, the aeroplane experiences the upward lift that supports it in flight, and according as the engine power is more or less than the exact amount required for horizontal flight so does the machine ascend or glide obliquely to the earth. The thrust of the two propellers (which are driven in opposite directions by chains, one of the chains being crossed), forces the machine through the air, and causes the aerodynamic condition that has been described above.

In order to maintain the machine in equilibrium, the pilot is provided with three controls that are operated by two levers, one of which he holds in his right hand while the other he holds in his left hand. The lever held by the pilot's right hand controls a miniature biplane that is mounted on a horizontal transverse axis situated about twelve feet in front of the main decks. This elevator, as it is termed, is carried on a light outrigger framework that also extends beneath the body of the machine and forms the ski or runners wherewith the machine alights upon the ground.

The purpose of the elevator is to assist in maintaining longitudinal equilibrium, and its two decks are so constructed that they can be flexed into a camber that is either concave or convex to the earth as required. When the pilot moves the lever so as to make the camber of the elevator concave to the earth, its aeroplane action, which is the same as that of the main planes already described, is such as to tilt up the front end of the machine. Conversely, if the machine is already tilted up too far, a reversal of the camber serves to restore the horizontal position.

The term elevator that has been applied to this device must not be supposed to suggest that it is capable of lifting the machine as a whole. Its elevating power is sufficient only to tilt the machine either for the purpose of .restoring equilibrium or for the purpose of inclining the attitude of flight. Actual ascent can only be effected as the result of developing an excess of power over and above that required for horizontal flight, hence the engine must be considerably larger than considerations of horizontal flight alone demand. Owing to the fact that an aeroplane does not develop the reaction necessary for its support unless it is travelling at a certain speed, it is, unfortunately, impossible to compensate for ascent by travelling more slowly through the air in order to economise power. Ascent automatically results from an increase of velocity through the air, and descent similarly results from a decrease in the velocity through the air, unless provision is made for altering the angle of incidence (i.e., the angle made by the chord to the relative wind), so as in the first place to reduce the lift for a given velocity, or, in the second place, to increase the lift for a given velocity. It would seem that the limits within which any such alteration is possible in machines with rigid planes is very limited in amount.

So far, we have considered only the longitudinal stability of the machine as it is determined by the operation of the elevator; an equally important matter is the transverse equilibrium and steering that are under control through the agency of the lever in the pilot's left hand. This lever is mounted on a universal pivot so that it can move sideways, or to and fro. When moved to and fro it operates the rudder at the rear of the machine and steers in the same way as a boat. If moved sideways it causes the extremities of the decks to warp in such a manner that the trailing edge at one end is depressed while that at the other end is raised.

This at once affects the camber of the decks and consequently the angle of incidence, so that, for a given velocity, one side of the machine exerts a greater lifting effect than the other. Should the machine be accidentally canted by a wind gust, warping thus affords a means of restoring balance. It is important, however, to bear in mind in connection with this system that any alteration in the angle of incidence likewise involves an alteration in the resistance of such a character as to make the machine swerve from its path. This tendency can be neutralised by a suitable use of the rudder, which, as we have explained, is controlled by the same lever, and it is, in fact, the great feature of the Wright control that the warping of the wings and the moving of the rudder can be simultaneously accomplished in this manner.

When steering, the warping and rudder movements are both brought into play. Flying over a curved path causes the outer extremity of the aeroplane to have a higher relative velocity than the inner extremity, and this in turn causes the outer extremity to exert a relatively greater lift so that the machine cants over. A certain amount of canting is obviously advantageous, in the same way that a banked road is advantageous when going round a curve on a motor car, but if the canting becomes excessive the machine might capsize, and in order to check this, the warping of the wings may be brought into action. If thought desirable the warping of the wings may, of course, be employed to give an initial cant to the machine; in fact any combination of rudder and warping movements may be employed as may seem to be best suited to particular requirements.

The Wright biplane is, as has been described, supported upon a pair of skis. It is not provided with any wheels for running along the ground, and, in order to be launched in flight, it has to be mounted on a light detachable trolley that is constructed to run upon a single rail previously laid down for that purpose. The initial acceleration is obtained by the use of a falling weight dropped from a tower and coupled up to the machine by a rope, but if the conditions are suited to the use of a longer rail, the machine may be started by the thrust of its own propellers alone. The trolley is, of course, left behind when the launching has been accomplished. If it is necessary to push the machine about over the ground another pair of light single wheeled trolleys are employed.

It is sometimes urged by those who take a pessimistic view of the future of aviation that this characteristic of the Wright flyer constitutes a permanent disability in machines of this type, and it should therefore be pointed out that there is no reason why the skis should not be fitted with wheels like the machines of Farman and others. The problem of making a re-ascent from any spot upon which the machine might happen to land as the result of a breakdown during an attempted cross-country flight is obviously one that is only capable of limited solution at the present time. The main desideratum has been to accomplish flight first and to work out details associated with such questions as re-ascent afterwards. It would trouble even a helicopter (i.e., direct lifting machine) to rise gracefully after a forced descent in the forest, and just as it is commonly difficult to re-float a stranded boat so is it only reasonable to suppose that flying machines may occasionally find themselves in difficulties, if for any reason they are unintentionally displaced from their element. The proper solution lies rather along the lines of reliability than special invention, for this factor, which has most contributed to the practical utility of the motor car, is also most likely, so it seems to us, to contribute to the practical utility of the flying machine.

From a constructional point of view the Wright biplane is of extreme interest, and it may be remarked that its many details have been the subject of most stringent criticism. For our own part we are inclined to appreciate the design as the embodiment of a remarkable amount of common-sense. One of the leading details of the machine is the method of attachment of the vertical struts, which support the upper deck, to the transverse spars that form the principal members of the decks. This detail forms the subject of an accompanying illustration.

The strut, which, like the rest of the framework, is made of wood, is fitted with a steel eye-piece that is let into a groove and lashed in place as shown in the sketch. The eye-piece fits over a steel hook that is fastened to the spar by a steel plate, and the hook and eye joint thus formed is locked by threading a piece of wire through two holes as shown in the sketch. It is a simple and effective coupling, as it enables the machine to be strained without doing permanent damage, and it also facilitates dismantling the parts.

Flight, March 19, 1910

Capt. Engelhardt at St. Moritz.

ON Tuesday morning Capt. Engelhardt, on his Wright biplane, flew for 32 mins. above St. Moritz, and thus won the Kurverein aviation prize. The altitude of the St. Moritz lake is 6,000 ft.

Flying from Satory to Issy.

CAPT. ETEVE, who, by the way, is the only French officer to possess all three of the Ae.C.F. pilot certificates, for balloons, dirigibles, and aeroplanes, flew on the 15th inst. from Satory to Issy. His machine is a Wright biplane which has been modified by himself, a tail being now fitted as well as wheels to render the starting rail unnecessary. Leaving Satory at 20 minutes past 5 he reached Issy at a quarter to six, having traversed the 19 kiloms. In 25 minutes.

Capt. Eteve has a Tumble.

WHILE practising on his Wright machine at Issy on Friday, Capt. Eteve fell from a height of 20 metres. He had previously had a slight mishap, but the result was not serious, only a wheel being buckled. He flew for 12 minutes on the following day.

Flight, September 3, 1910

WITH THE WRIGHTS IN AMERICA.

By GRIFFITH BREWER.

Apologia.

WHEN I accepted the hospitality of the Wright Bros., I had no idea of publishing the observations of a private visit, nor did I give any hint to them of such a possibility. It was only after waving farewell at Dayton Railway Station that the thought developed of giving to my fellow members of the Royal Aero Club some small idea of what is being done at Dayton, so that when the pioneers of flight have an opportunity to return to England, we in the Royal Aero Club may not have followed the general lead like a flock of sheep, and have shown by our actions and our talk in their absence, that out of sight from England means also out of mind. I therefore crave indulgence if the writing of this account is indiscreet, and I fear it must be so, because it was the only work that could be found for my hands to do on the voyage back on the "Baltic."

We are apt to forget in our desire to see flying general, that we owe everything to these two American scientists. If it had not been for their discarding the then accepted scientific data and starting at the beginning and building up their own tables and diagrams, they might still have been floundering in endless experiments together with others who have since been successful. It is no use deceiving ourselves into the belief that it was the introduction of the petrol engine that gave the Wrights the opportunity that was denied to others, because when they flew they carried sufficient margin of power to have flown with the power available twenty years earlier. In 1892 Maxim built a machine with sufficient power to fly, but all the modern petrol engines in the world would not be able to coax that machine to go up in the air to-day. I am as confident that we should not be flying to-day were it not for the Wrights as I am that the pneumatic tyre would still be unknown to the world were it not for Dunlop. I am also confident that if we can get these pioneers of aviation to spare us some of their attention, that the cause of flight in England will be considerably enhanced. It is therefore with a feeling of pleasant anticipation that we may look forward to a visit from our American friends towards the end of the present year.

The First Mechanical Flights.

I never thoroughly realised the absurdity of the so-called mystery of the early flights made by the brothers Wilbur and Orville Wright, until this August, when I visited the first flying field. I knew before that the field was surrounded by a fence, and this fence, with its suggestion of secrecy, naturally implied a high palisade such as we call fences in England. Instead, however, of the 6 ft. split-oak palisading to obstruct the view, I found nothing but a row of low posts, supporting four rows of wires, to keep the farmer and other wayfarers from looking their fill as they travelled down the main road between Springfield and Dayton, both towns of over 100,000 inhabitants. Moreover, if one main road bounding one side of the ground were not sufficient, then a cross-road bounding another side of the land afforded equal facilities; whilst three electric railway cars per hour also passed along the track adjoining the main road, and allowed their fifty occupants to view the whole ground, and if sufficiently interested to alight at "Simms" station, which abuts directly on one corner of the land rented by the brothers for their early experiments in 1904, and now used by them to-day as a school for their pupils.

Newspapers have always been accustomed to receive voluminous copy from those experimenting with so-called flying machines, the necessity of giving a full report seeming to most experimenters to be of greater importance than the accomplishment of something to report on; so when the two quiet young men squabbled amongst themselves over the theories of flight during their leisure at home, and put their differences of opinion to the test outdoors in their vacation, it was natural for the newspapers to regard these holiday pranks of no serious importance. As it was in 1903 to 1906, so it is to-day. The work of building machines and testing alterations is proceeding in the same methodical manner as the development of a motor launch, and those genial brothers are getting as much fun out of it as Tom Thornycroft gets in making himself hot and dirty down on the "Enchantress."

Manufacturing Facilities.

I had expected to find the Wright Co. installed in an up-to-date factory adjoining the flying ground, and Wilbur and Orville Wright sleeping on beds up amongst the rafters of the shed, and cooking tasty meals between whiles. Instead I found them living with their father and sister in the wooden house they had grown up in from the time when they were all children. The workshop where they make their engines is within a quarter of a mile, and is the same where six years ago they were turning out the Wright bicycles which hold their own to-day. Even closer to the house is the little printing works, where before making bicycles, they expended their unlimited energy and ingenuity not only in printing a newspaper, but in making the printing machine, which they constructed out of pieces of wood and bits of string. This Robinson Crusoe printing press was only designed for home use, for it invariably refused to go unless one of the brothers were looking on.

The factory where the flying machines are built is three miles away on the other side of the city, and there in a large airy ground floor building some six machines were in various stages of construction. One machine just on completion attracted my attention, as it enabled me to compare the tail used by the Wright Brothers in America with the tail fitted by Mr. Rolls to his French-built Wright machine just before his fatal accident. The differences in construction were very considerable, the American pattern being considerably stronger than the French pattern, whilst a clearance of 11 ins. between the propellers and the tail frame showed a considerable increase in the margin of safety compared, with a 3 in. clearance on the French designed tail. The maximum working strain that can be brought on to the tail is less than 70 lbs., and this tail took the strain of Wilbur Wright's weight and my own, or over 250 lbs. dead weight on its outer end without bending more than an inch out of line. The breaking of the tail-frame under wind pressure would, therefore, be impossible in the American-built machine, and although the French construction was weaker, it is extremely improbable that the tail on Mr, Rolls' machine collapsed under wind pressure.

Mr. Rolls' Accident.

The propellers probably fouled the frame of the tail and cut through the lower members, but how the frame approached sufficiently to take up the three inches clearance, whether by bending or disconnecting, will never be known. Although it is certain that the tail frame broke in the air, it is by no means certain that this was the cause of the main accident. The wind was blowing towards the grand stand, and would be rising in a wave over it, and in commencing the dive towards the target the machine would be running down at an angle in a rising current. Most of the weight of the machine is between the main planes, and when the machine entered the lower strata of air this would be travelling horizontally, and would catch the elevating front planes on their upper side, thus tending to still further increase the downward angle of travel, irrespective of the angle at which they might then be set. The inertia of the weight would, however, maintain the forward direction of the heaviest part, and assist the completion of the vertical movement. Rolls attempted a daring manoeuvre, just as a hundred times previously he had dared some feat in motoring or ballooning, but on this occasion the risk he took prevailed. The fact that the Wright Brothers neither designed nor authorised the tail fitted to Mr. Rolls' machine does not therefore appear to be of much importance, because, no matter what machine had been flown and brought into that diving position in the wind wave before that grand stand, the result must have been the same.

Pupils Learning to Fly.

The flying ground used by the Wright Brothers is situated about eight miles west of the city of Dayton, at a small station called "Simms" on an electric car line between Dayton and Springfield. The cars, which are as large as Pullmans, leave the main street in Dayton on the ordinary city tram rails every half-hour, and in twenty minutes drop their crowd of aviators and spectators on the main road which runs alongside the rough weed-grown field. Every morning at breakfast the telephone used to ring, and the same answer suited all enquirers, "Well, you are as likely to see a flight to-day as any other day. The Wright Brothers don't know themselves whether there will be any flying," and this explanation was literally true. They never knew, any more than other inventors, what stage of the designing, testing, or experimenting they would reach that day. After the first day's visits to the factory and the workshop I generally remained at home, until Wilbur or Orville came running in to say they were going out to Simms on the next car. If the weather was fine, then we had to fight our way on to the car, Orville generally riding on the step because of the crowd going out to see the "airship proposition." Why will the man in the street muddle the airship with the aeroplane? He does not muddle a life-belt which enables him to float in the water with a pair of skates for gliding on the surface; but perhaps he did make this mistake when skates were first invented.

On arriving at Simms we cross a plank bridge over a ditch, pass through a little wicket gate and enter the back of the shed where two machines are standing. One is on skids and the other has auxiliary pairs of wheels attached to the skids. Mr. Coffyn is in charge of the school, and two other pupils, Messrs. Brookins and Johnstone, are tinkering with the machines preparatory to making trial flights. Both machines have adjustable tail planes attached, and one has had the two front planes removed and the "blinkers" have been nailed temporarily to the front framing. This frontless machine is the first to be taken out, and we pull it out on to the smoothest part of that rough ground, where weeds as stiff and high as young willows cover most of the land. Then the engine is started up, and before I know what is about to happen there is Orville riding up in the air on the machine without its bridle. "They'll be going up soon on the engine alone with half a propeller," remarks the man who hands back my cap across the fence where it has been blown by the wind from the propellers. After a short three minutes' flight Orville is down again to make some adjustments, and then in another seven minutes is up for a second trial. They have a simple homemade range-finder at Simms composed of a wooden yard stick and a little metal slide on it having two pairs of prongs projecting from it at 1 in. and 1/2 in. apart respectively. You point the stick and sight it at the machine as it flies overhead, and run the slide out until the prongs enclose the wings exactly. Knowing the wings to be about 40 ft. wide, and assuming the 1 in. prongs fit at 10 ins. distance down the stick, the height of the machine is approximately 400 ft. One of the first flights that I saw measured by Wilbur in this way gave Orville a height of 1,200 ft.

More Flights and "Stunts."

My second visit to Simms was a pupils' day, commencing with Brookins going up and doing "stunts" for my benefit. He turned many circles in less than ten seconds each, and the banking angle to which the machine was brought in these quick turns was 45 at the least. On expressing surprise at these quick evolutions, I am told that he has turned a complete circle in less than seven seconds, but has been instructed not to do so quick a turn again before the strains brought on to the machine, and which exceed twice the ordinary flying strain, have been accurately figured out. This Brookins is a promising kind of pupil, and holds the world's record for height, having flown under official observation 6,175 ft.* *(Drexel at Lanark has since then bettered this.) This was done early in July at Atlantic City when he won the L1,000 prize for beating all officially certified high flights. Brookins seemed too daring, and I told him that I for one would nor care to experience the exhilaration of a flying trip with him. A new pupil is to be taken up for the first time, and Orville decides to take him instead of leaving him to Brookins. "I guess he was afraid I'd scare him too much for a first trip," says Brookins as they fly overhead, the novice squeezing the sap out of the upright, to use the parlance of the expert flyers of two months standing. It is well to notice here that Brookins, who had never seen a flying machine three or four months ago, has found no difficulty in mastering the "complicated Wright flyer" and capturing a world's record on it. Before I left ten days later, the novice, Parmalee, was using both levers, and told his instructor that he thought he had nearly got the hang of that "double-jointed lever." After this lesson Johnstone was sent up for a practice flight of an hour, sufficient petrol being put into the tank to cover the hour, but insufficient to tempt him to make a record for endurance. At the end of an hour and thirty-four minutes he came down with the petrol finished. The day terminated by Coffyn making two 20 minute flights, the second being terminated by signal, so that we might all catch the next tram home. This time I stood on the step and Wilbur and Orville got jammed somewhere in the vestibule. Brookins and Johnstone hung on to the buffer and cowcatcher outside, whilst the spectators sat it out comfortably on the seats.

And so the days flew by. Crammed full of interest from the time of eating the cantaloupes in the morning, to the sitting out on the verandah after dinner at night, when the brothers talked horse-power and wind surfaces, while I watched the fire-flies and got in the way of the arguments as little as I could. And I don't think the pleasure was all on my side. All the Wright family seemed out for fun, and each member worked hard to get it. Even Bishop Wright at the age of 82 wants his share, and when Orville took his venerable father for a ride aloft, he had to mount to many hundred feet in compliance with his passenger's requests to go up higher. This enthusiasm also struck others, for the lighthouse keeper at Kitty Hawk said he had never seen men work so hard for fun before.

A Ride on the Wright Flyer.

Those who have been favoured with a ride with Wilbur or Orville have never had previous warning. The simple question, "Are you ready for a ride?" has now been put to several, and I have never yet heard of its being refused. At Le Mans, when Wilbur rewarded the "English bunch" for their enthusiastic patience, he took all four of us up one after the other, these Aero Club members all having instantly answered "Yes" to this welcome invitation. So when Orville put the same gratifying question to me at Simms I stifled my determination to keep out of the way so as to let them get on with their work, and took my place on the central seat next to the engine. This time we were to fly with one elevator plane detached, and with the right-hand blinker only. We also tried the experiment of running through the long weeds before the wind; but, although we succeeded in decorating the machine with green, and taking on board a cargo of grasshoppers, we made the first and only false start. My weight has gone up since my last trip, but it is still below that of one of my rival butterflies at Le Mans. A second attempt in the opposite direction was more successful, and we began to climb up stepless stairs as we went round the field. Out of consideration for my novice feelings Orville refrained from anything in the way of "stunts," although he took the machine round some beautiful curves, and up to about 400 ft., where the air was delightfully warm as distinct from the damper air near the ground. Then we slowed the engine down to walking pace, and slid down an elastic slope to the level of the tree-tops, when we quickened up and ran through the weeds, collecting their tops on the skid-stays without the wheels or skids touching the ground. Perhaps they'll add a scissors attachment below the machine, and use it as a reaper later on.

A "Hole in the Air."

Up into the air again, waving a greeting in return from those at the shed, and later at the other end of the field we ran into the "hole in the air" that has been referred to by many aviators. M. Paulhan told me that in his flight to Manchester he encountered such a hole, and the machine fell some 30 ft. before recovering its airy support. My experience was mild compared to this. We were running quite smoothly when the seat seemed to give way, and it was quite an appreciable moment before I felt I could sit on anything solid. Looking to Orville on my left, I met his reassuring smile, and we went smoothly on to inspect neighbouring cornfields and cut a few eights as a fitting termination to a 23 minute flight. They say the particular spot where we had the "little drop" is in a corner of the field where it is quite usual to encounter similar whirls or disturbances. The machine did not pitch or oscillate, but simply went down bodily about 2 ft.

More Pupils and Workshop Observations.

After my own flight, other flights seemed to me of less consequence, but they went on just the same. Each pupil did his "stunt," and each instructor reflected how green he must have been a month before when then only a pupil. The days when we did not go out to Simms brought in a report from Coffyn giving a list of flights by the various pupils, and the brothers went on in their leisurely, get-there way, designing, thinking, making and testing - not testing to find out, but testing to prove conclusions, already arrived at. At the works one morning I noticed an engine running by itself and turning an arm giving similar resistance to a pair of propellers. This engine, which seemed to have been forgotten, was still running later in the afternoon when I went there again, so I enquired, and found that it had been started at 8 a.m., and with the exception of the lunch hour, it had been running all day without attention and would run like that till 5.30. Why do we have such engine troubles in Europe, and why can't we get our engines to run like they invariably do in America? Is it because the Americans have to work so much harder across the Atlantic, and that their engines out of sheer force of example do the same?

And so they go on day after day, gaining the love and respect of their pupils and all with whom they come in contact. Just as it was at Le Mans and Pau, where their influence was more far-reaching than in the cause of flight alone.

The Wright Patent Litigation.

Before closing, let me say a few words to explain the present situation of the Wright Patents. Both in America and England the Courts have power to issue an interim injunction restraining infringement of a patent, in which it is shown to the satisfaction of the Court that infringement is taking place and that damage will be incurred if the continued infringement is not restrained. It is, however, extremely rare that such a power is exercised before the hearing of the trial, when the witnesses are examined. The validity of the patent was not disputed, and the judge, after consideration of the documents in the case, decided that the infringement was so obvious that he granted the interim injunction. The defendant appealed, and filed additional documents, and the Wright Co. considering the new documents to be unimportant, did not apply to refer the new documents to the first Court, but, in order to save time, went direct to the Court of Appeal. The latter held that they could only consider the judgment of the Court below, and they could not go into the merits of the case as affected by new documents. In view, therefore, of the fact that the new documents were now on the record, but had not been before the first Court, the Appeal Court could not support the injunction on the unconsidered documents, and, therefore, the interim injunction must be quashed. There can be no doubt that the Wright Co. will win their action, seeing that their case was strong enough to enable them to obtain an injunction in the same Court before. The parties are now in the same position as if the injunction had never been obtained, and the trial in the first Court will come on for hearing at the end of the year in the ordinary way.

Flight, September 10, 1910

Capt. Engelhardt at Johannisthal.

FLYING on a Wright biplane Capt. Engelhardt on Monday last made a cross country journey, passing over Rudow, Lichtenrade and Glienicke at a height of 400 metres. The trip lasted 20 mins., the distance being about 18 kiloms.

Flight, October 29, 1910

BOYS' MODELS.

Enclosed you will find two photos of a model biplane of my own design and construction. The main planes are 2 ft. 11 ins. in span, and the elevator and rudder are worked by two levers on the Wright principle. This is my third model, the two previous ones being monoplanes.

Hounslow. R. E. M. FERRY.

Flight, March 9, 1912.

AEROPLANE UNDERCARRIAGES.

By G. DE HAVILLAND.

Types of Undercarriage.

The Wright aeroplane is chiefly interesting from the fact that it was the first practical machine in which a rigid framework was provided beneath the planes in place of the flexibly mounted undercarriages adopted by the French constructors at about the same period, the outcome of these two systems being the combination of skids and wheels in later types of machines.

The chief advantage of this system is, that it provides a rigid structure to which the main lifting-wires may be fixed, these wires also being effective in taking any side-strains imposed on the undercarriage itself.

Показать полностью