А.Шепс Самолеты Первой мировой войны. Страны Антанты

"Блерио-XI", прославивший своего создателя перелетом через Ла-Манш, стал первым в мире самолетом, примененным в военных действиях. Машины этого типа принимали участие в Итало-Турецкой (1911-12 гг.) и в Балканских (1912-13 гг.) войнах. К началу первой мировой "Блерио" состояли на вооружении во Франции, Италии, Великобритании, Бельгии, Италии и Болгарии. В России насчитывалось около 50 аппаратов (из них до 30 - местной постройки), которые использовались в качестве учебных.

Для французской армии самолет выпускался в одноместном варианте (Militaire - военный), двухместном (Artillerie - артиллерийский) и трехместном (B-XI-3) вариантах. На западном фронте "Блерио" применялись в первые месяцы войны как разведчик и самолет связи, а в некоторых случаях - и для бомбометания. Ими было оснащено 6 французских и 6 итальянских эскадрилий, отдельные машины входили в 4 английских авиадивизиона. Однако появление у немцев самолетов-истребителей положило конец боевой карьере этих тихоходных невооруженных аэропланов. Весной 1915 года все уцелевшие к тому времени "Блерио" перевели в учебные подразделения.

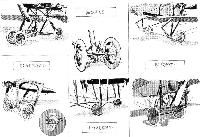

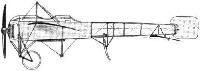

Это был расчалочный моноплан деревянной конструкции. Фюзеляж прямоугольного сечения обтягивался полотном только в носовой части. Крыло трехлонжеронное, деревянной конструкции, обтянутое полотном. Крепление осуществлялось тремя парами растяжек из стального троса. Поперечное управление осуществлялось перекашиванием крыла. Хвостовая часть фюзеляжа не обшивалась. Руль поворота и руль высоты деревянной конструкции, обтянутые полотном. Руль поворота устанавливался на конце фюзеляжа. Руль высоты - под фюзеляжем, в хвостовой части. На самолет устанавливались различные двигатели воздушного охлаждения мощностью от 35 до 80 л. с. Самолет имел оригинальное шасси, рычажно-пружинная амортизация которого была довольно громоздкой. Вместо костыля - хвостовое колесо или две металлические дуги. Металлическими были также стойки кабины.

Выпускались также варианты на поплавковом шасси и с крылом типа "парасоль". На эти машины устанавливались двигатели Гном или Рон.

Модификации

"Блерио-ХI-2" - двухместный вариант "Блерио-XI" с двигателем "Анзани" (35л. с.). Крыло имело небольшое поперечное V. Применялся хвостовой костыль.

"Блерио-ХI-2-бис" - двухместный учебный, разведывательный и связной самолет несколько увеличенных размеров. Стабилизатор треугольный, вытянутый до задней кромки крыла. Самолет был неустойчив и труден в управлении. Двигатель "Гном" мощностью 70л. с.

"Блерио-ХI-3-бис" - трехместный вариант с двигателем "Гном" (100л. с.). Большого распространения не получил.

"Блерио-ХII" - развитие серии "Блерио-XI", но крыло сделано по схеме высокоплана вместо "среднеплана"-предшественника. Двигатели "Гном" (60 или 80 л. с.). В 1910 году несколько самолетов поступило в Россию.

"Блерио-XXI" - двухместный вариант, созданный на базе "Блерио-ХI-2-бис" с двигателем "Гном" (70л. с.).

В преддверии войны почти все машины получили дополнительное название "Милитэр" (военный). Конструкторы пытались предложить машины военным, доказывая пригодность своих машин для целей разведки.

ОСНОВНЫЕ ВОЕННЫЕ МОДИФИКАЦИИ

"Блерио-XI Милитэр" ("военный") - экипаж 1 человек, двигатель "Гном", 50 л.с.

"Блерио-XI Артиллери" ("артиллерийский") - экипаж 2 человека, двигатель "Гном" 70 л.с.

"Блерио-XI Жени" ("инженерный") - то же, что и "артиллерийский", но с усиленным шасси и видоизмененным хвостовым оперением.

ВООРУЖЕНИЕ

Не предусмотрено. В отдельных случаях на борт брали несколько мелких бомб, сбрасывавшихся вручную или с помощью самодельных приспособлений.

ЛЕТНО-ТЕХНИЧЕСКИЕ ХАРАКТЕРИСТИКИ ("Блерио-XI Артиллери")

Размах, м 10,20

Длина, м 8,25

Площадь крыла, кв.м 20,9

Сухой вес, кг 350

Взлетный вес, кг 570

Скорость максимальная, км/ч 95

Время набора высоты, м/мин 1000/14

Потолок, м 4300

Показатель Блерио-XI-2-бис Блерио-XI-3-бис Блерио-XXI Блерио-XI-2"

1910г 1911г 1911г

Размеры, м:

длина 8,25 8,50 8,24 8,50

размах крыльев 11,0 11,4 11,0 10,35

высота 2,60 2,50 2,60 2,60

Площадь крыла, м2 25,0 25,0 25 25,50

Вес, кг:

максимальный взлетный 570 610 330 585

пустого 350 380 330 350

Двигатель: "Гном" "Гном" "Гном" "Гном"

мощность, л. с. 70 100 70 80

Скорость, км/ч 85 100 90 106

Дальность полета, км 300

Потолок практический, м 1300

Экипаж, чел. 2 3 2

Вооружение 60 кг бомб

Машины, строившиеся в России по схеме "Блерио-XI"

Блерио-XI "Дукс" Гризодубов-IV Россия-Б "Люсик" Стаселя

1912г 1912г 1910г 1910г

Размеры, м:

длина 7,20 7,5 7,5 7,5

размах крыльев 8,90 7,5 7,5 7,5

высота 2,30

Площадь крыла, м2 20,9 14,0 14,0 14,0

Вес, кг:

максимальный взлетный 440 340 330 340

пустого 295 240 230 240

Двигатель: "Гном" "Анзани" "Анзани"

мощность, л. с. 70 25 25

Скорость, км/ч 90 70 70 70

Экипаж, чел. 1 1 1 1

Вооружение - - - -

В.Шавров История конструкций самолетов в СССР до 1938 г.

Из большого числа самолетов "Блерио" в России было несколько типов, один из которых строился серийно. Автор их французский конструктор и летчик Луи Блерио получил мировую известность, впервые перелетев из Франции в Англию через Ла-Манш 25 июля 1909 г. на своем самолете "Блерио-XI". За 1907-1913 гг. Блерио построил до трех десятков различных самолетов своей конструкции. Некоторые из них применялись как учебные и спортивные и до войны пользовались широкой известностью. Для военного применения самолеты Блерио были мало пригодны. Стрелкового вооружения они не имели и их применяли на фронтах недолго. К 1917 г. эти самолеты прекратили свое существование, и сам Блерио уже участвовал в создании других конструкции самолетов, в том числе самолетов "Спад".

"Блерио-XI" ("Блерио" учебный). На этом самолете многие. учились летать в 1909-1910 гг. Самолет был приобретен в двух десятках экземпляров русским военным ведомством и частными лицами. В 1910-1915 гг. он применялся в русских летных школах, под конец преимущественно как учебно-рулежный. Первоначально на "Блерио-XI" был установлен двигатель "Анзани" в 25 л. с., с которым этот самолет летал неуверенно. Потом ставились двигатели в 40 л. с. (ENV и "Лабор"), но и их мощности было недостаточно для устойчивого и надежного полета, и в том же 1910 г. на самолете был установлен двигатель "Гном" в 50 л. с. при сохранении той же конструкции. Были небольшие колебания в размерах различных экземпляров "Блерио-XI". С двигателем "Гном" в 50 л. с. эти самолеты стали называться "Блерио-XI бис".

<...>

L.Opdyke French Aeroplanes Before the Great War (Schiffer)

Deleted by request of (c)Schiffer Publishing

XI-2 Tandem: In February 1911 the XI-2 itself came in several versions. One had a lengthened nose and odd curved tailskid, another was a 3-float hydro with a tall rudder. Some had oyster-shell elevators, others had the 2-piece design. Some had half-covered fuselages like the XI, others were fully covered. Perreyon's 160 hp model had a single seat and V-leg undercarriage. But most of them were longer than the XI, with a raised cowling ahead of the first cockpit, and the tall mid-fuselage skid.

(1912: Span: 9.7 m; length: 8.3 m; wing area: 20 sqm; empty/gross weight: 300/550 kg; 70 hp Gnome)

(1913: Span: 10.35 m; length: 8.4 m; wing area: 19 sqm; empty/gross weight: 335/585 kg; top speed: 115/120 kmh; 80 hp Gnome)

XI-2 Type Genie (engineer): Similar to the XI-2, the April 1912 70 hp Gnome Genie had an odd horizontal tail unit set on struts below the aft fuselage, with a one-piece elevator with an S-curved trailing edge. The rudder did not hang below the tailpost, and the bottom rear corner was clipped to allow for the elevator below it. The 2 cockpits were separated; the cabane was now a 4-strut pyramid, and the tailskid was the single high design aft of the rear cockpit. The fuselage of the machine used for the Circuit d'Anjou race was fully covered.

(Span: 9.7 m; length: 8.3 m; wing area: 18 sqm; empty eight: 320 kg; loaded weight: 550 kg; speed: 110-115 kmh; 70 hp Gnome)

XI-2 Type Hauteur: Powered with the 80 hp Gnome, this one was used by Roland Garros in his altitude flights in August 1912 and March 1913. With a 4-strut pyramidal cabane, it stood on a V-leg undercarriage. The machine used in the later attempts had a fully covered fuselage; in June a similar machine with 2 seats beat Garros' records.

The famous stunt-flier Pegoud used at least 3 different XIs. His most famous achievement, the first loop, was in 1913 inahalf-Bleriot, half-Borel machine with a 2-piece elevator and a single inverted-V pylon. His experiment with a parachute attached to the top of the fuselage in 1913 was in another XI with a V-leg undercarriage and the tip elevators of a much earlier period. A third one appeared with the high tailskid set shortly behind the cockpit.

The Type XI in its various forms, and some of the later models as well, served until 1915 when the monoplane design fell into disfavor. Bleriot joined the Spad firm (la Societe Provisoire des Aeroplanes Deperdussin), and became its president. When Armand Deperdussin was disgraced for his financial misdealings, Bleriot absorbed the firm, becoming president and changing its name to la Societe pour l'Aviation et ses Derives, with Bechereau as chief engineer. After the war, Deperdussin committed suicide.

Bleriot now concentrated on building Spads, and with the designer Herbemont, racing aircraft; he also built a 26-passenger 4-engined transport in 1919. The firm diversified as well, into motorbicycles, boats, and knock-down furniture. Back into aircraft, he produced pursuit and heavy transport designs. Bleriot died on 1 August 1936, and on 20 March 1937 his factories were nationalized.

O.Thetford British Naval Aircraft since 1912 (Putnam)

BLERIOT TYPE XI

Fundamentally similar to the aircraft used by Louis Bleriot for his historic crossing of the English Channel in 1909, this type was used by both the Naval and Military Wings of the RFC and subsequently by the RNAS from 1912 to early 1915. One 80 hp Gnome engine and a loaded weight of 1.388 lb. Maximum speed, 66mph at sea level. Climb, 230 ft/min. Span, 34 ft 3 in. Length, 27 ft 6 in.

M.Goodall, A.Tagg British Aircraft before the Great War (Schiffer)

Deleted by request of (c)Schiffer Publishing

BLERIOT AERONAUTICS (Louis Bleriot, Belfast Chambers, 156 Regent St., London, W. Flying School & Works at Hendon and Brooklands)

After Bleriot's Channel crossing in July 1909 in his Type XI monoplane, a number of similar machines were made by various firms and individuals, mostly without approval by Bleriot. A Bleriot School was established at Hendon on 1 October 1910, and in 1914 sheds were taken at Brooklands and enlarged to provide offices and manufacturing facilities, all under the control of M. Norbert Chereau, Bleriot's manager for Great Britain.

The RFC used various types of Bleriot monoplanes operationally prior to and in the early months of the war, but these were soon relegated to training duties. The majority of Service aircraft were probably French made, but the British company received contracts for the Type XI single-seater, the Type XI-2 two-seater and the single-seat parasol version of 1914. Deliveries of these continued well into 1916, by which date the works were in the process of being transferred to new premises at Addlestone, Surrey.

The quantities of Type XI and XI-2 aircraft made in Britain is uncertain, but it is recorded that at least fourteen parasols Serial Nos.575-586 and 2861-2862 were made at Brooklands.

Bleriot Type XI-2 monoplane

Power: 70 or 80hp Gnome seven-cylinder air-cooled rotary.

Data

Span 34ft

Length 27ft 6in

Area 205 sq ft

Height 8ft 2in

Weight 738 lb

Weight allup 1,290lb

Max speed 75 mph (80hp)

Endurance 3 1/2 hr

Jane's All The World Aircraft 1913

BLERIOT Monoplanes. L. Bleriot, "Bleriot-Aeronautique," 39, Route de la Revolte, Paris-Levallois. Flying grounds: Buc Etampes and Pau.

L. Bleriot began to experiment in 1906, along Langley lines. By 1909 he was one of the leading French firms; and the first cross Channel flight was made by him.

Details of standard types:--

XI bis. XXI. XXVII. XXVIII. XXVIII. Monocoque

2-seater Military Single Single 2-Seater 2-Seater

mono side by seat seater

(1911 side mono. 1913. 1913. 1913.

onward) 2-seater 1912.

mono. 1912

Length....feet(m) 27(8.40) 27? (8.24) 28 (8.5) 25 (7.60) 27 (8.20) ...

Span......feet(m) 36 (11) 36 (11) 29? (9) 29 (8.80) 32 (9.75) 40(12.25)

Area..sq.ft.(m?.) 349 (33) 268 (25) 129 (18) 162 (15) 215 (20) 270 (25)

Weight, unladen...

........lbs.(kgs) ... 727 (330) 529 (240) 530 (240) 660 (300) 830 (375)

Weight, useful...

.......lbs.(kgs.) ... ... ... 286 (129) 550 (250) ...

Motor.......h.p. 50 Gnome 70 Gnome 70 Gnome 50 Gnome 70 Gnome 80 Gnome

Speed,max...

.......m.p.h.(km) 56 (90) 56 (90) 78 (125) 62 (100) 71 (115) 75 (150)

Endurance...hrs. ... ... ... ... ... ...

Number built

during 1912 ... ... ... ... ... ...

Note.--The monos., as usual, are of wood construction; wheels only for landing. Rectangular section bodies. Warping wings, elevator in rear. Chauviere propeller. The monocoque has wood, steel and cork construction. Coque body. Skids to landing chassis. Levasseur propeller. Otherwise as the other monos.

Principal Bleriot flyers are or have been:--Aubrun, Balsan, Bleriot, Busson, Chavez, Cordonnier, Delagrange, Drexel, Efimoff, Gibbs, Hubert, Hamel, Moissant, Paulhan, Prevetau, Prevot, Prier, Radley, Thorup, Tyck, Wienzciers, and many others.

J.Forsgren Swedish Military Aircraft 1911-1926 (A Centennial Perspective on Great War Airplanes 68)

Bleriot XI

Almost inevitably, a small number of Bleriot XIs entered service with the AFK. The first two were bought in December 1913 from Skandinaviska Aviatik AB (a company controlled by Carl Cederstrom), both being taken on charge January 7, 1914. Powered by 24 and 35 h.p. Anzani engines respectively, these Bleriot XIs were used at Malmen as non-flying taxiing trainers. Neither of them received a serial number, with both being struck off charge in December 1916.

Following outbreak of war, three Bleriot XIs were purchased on August 8, 1914 from civilian owners. All were powered by 50 h.p. Gnome Omega rotary engines. The first of these was an AVIS-built Bleriot XI, being serialled 7. After being struck off charge in November 1916, this Bleriot XI was sold to AETA, eventually emerging as Thulin A s/n A8. In this context, mention must be made of Enoch Thulin’s company AETA, which during the fall of 1914 had begun building the Bleriot XI under licence as the Thulin A. Thulin appear to have expected the AFK placing a substantial order for Bleriot XI/Thulin As, something which, in the event, never materialized.

The second Bleriot XI had been built in 1912 for Skandinaviska Aviatik AB. Following arrival in Stockholm, the airplane was assembled by Wiklunds Maskinfabrik, being air tested on September 3,1912. Already in October 1912, the Bleriot XI was sold to the magazine publishers E. Akerlund and J.P. Ahlen. Initially named Ugglan (The Owl), the airplane was renamed in July 1914 as Vecko-Journalen (the name being one of the magazines published by Ahlen & Akerlund). In May 1914, AVIS had refurbished the airplane, which was then air tested by Enoch Thulin on June 6, 1914. After being taken on charge by the AFK as serial number 11, it was used at Malmen as a primary trainer. It was struck off charge in November 1916.

The third Bleriot XI had originally been bought in France in 1911 by Carl Cederstrom. Apparently, the airplane was ’’strengthened for loopings”. Arriving in Stockholm on May 11, 1911, the airplane was assembled by Wiklunds Maskinfabrik. Following an air test on May 20, the Bleriot XI was named Nordstjernan (Northern Star) by Cederstrom. Used extensively by Cederstrom for exhibition flying tours around Norway and Sweden, the airplane was sold to Enoch Thulin and Tord Angstrom on June 5, 1913, with Thulin becoming the sole owner two-and-a-half months later, on August 15. Following purchase by Thulin and Angstrom, the airplane underwent and extensive refurbishment, involving the replacement of the fuselage and wings.

After being taken on charge by Flygkompaniet in August 1914, the serial number 13 was assigned to the airplane. Following a crash in September 1915, the Bleriot XI was rebuilt, and issued with a new serial number; 17. On November 21, 1916, it was written off in a crash at Silows kulle (Silow’s hill, the place of Carl Silow’s fatal crash on May 1, 1915). Seemingly a case of having nine lives, the remains of the Bleriot XI was sold to AETA, subsequently reemerging as Thulin A s/n A9.

Additionally, one Bleriot Big Bat (possibly built in Great Britain), was offered to AFK in August 1914 by its owner, Filip Bjorklund, but rejected. In February 1915, Bjorklund sold his Bleriot to Denmark.

Bleriot XI Technical Data and Performance Characteristics

Engine: 1 x 50 h.p Gnome rotary engine

Length: 7,5 m

Wingspan: 8,85 m

Height: 2,7 m

Wing area: 14,00 m2

Empty weight: 320 kg

Maximum weight: 400 kg

Maximum speed: 80 km/h

Armament: -

J.Davilla Italian Aviation in the First World War. Vol.2: Aircraft A-H (A Centennial Perspective on Great War Airplanes 74)

Bleriot 11

The Italian Aviazione Militaire (Air Service) purchased five Bleriot 11s in 1910. These were:

1. 50-hp Gnome - one two-seater and one single-seater.

2. 35-hp Gnome - one single-seater.

3. 25-hp Gnome - two single-seat trainers.

Italian Variants

The Italians used five main types of Bleriot 11s, all built under license by Oneto di Pisa and S.I.T. (the Societa Italiana Transaerea = Italian Transaerial Society). S.I.T was part of the Bleriot company created by them at Turin. The sixtieth and last model was tested on November 20, 1915.

1. Bleriot 11 “Monoposto” - a single-seater with a 50-hp Gnome engine. It was soon discovered to be of little use in wartime.

2. Bleriot 11 with low power (30 to 45-hp) Anzani engines. These were also too underpowered for combat service, but proved to be excellent trainers.

3. Bleriot 11 “Parasol” - 70-hp Gnome; this saw widespread use with the squadriglias. Eight were built in France, but were soon found to be of limited use. Approximately 47 were built by S.I.T.

4. Bleriot 11 “Idro” - seaplane version of the 11 with a 90-hp Le Rhone engine, twin floats and a tail float. Only one example was produced.

5. Bleriot 11-2 - a two-seater with an 80-hp Gnome engine. It was used for reconnaissance and bombing, as well as training.

There were also underpowered versions (likely created from the Anzani powered versions) used as “penguins” to familiarize students with aircraft handling without actually being able to take off.

6. Bleriot “Biposto” - Unlike the Bleriot 11 designs, the “biposto”was a conventional biplane with tail booms and cockpit with a pusher engine. It was two-seater equipped with an 80 hp Gnome rotary engine. The aircraft was built in 1913 by Louis Bleriot, breaking a tradition that was the standard bearer of the monoplane, built the aforementioned biplane which appeared at the Paris International Air Show that same year.

The aircraft closely resembled a Henri Farman H.F.20 apart from the simplified landing gear (no skid) and more rounded wing tips. The biplane remained a prototype state presumably the French were satisfied with the Farman design.

S.I.T. was owner of the Bleriot patents in Italy and in 1914 acquired the aircraft which they designated “Biposto” to evaluate in Italy.

No further examples were purchased.

7. SIA-Bleriot - These were eliminated by the military prior to the start of the 1912 competition. They were an all-metal biplane version of the Bleriot 11. It was designed by Ing. Alberto Triaca with an 80-hp Gnome engine. A total of 77 examples were built by S.I.T., alone. Italian production brought the number of Bleriot 11’s acquired up to 221.

Operational Service

Bleriot Ils of various types were sent to the aviation scuole (school) at Centocelle in Rome), which ceased operations on March 11, 1911. The Bleriots were then sent to the schools at Malpensa and Aviano.

The aircraft found a more warlike role when they served as reconnaissance aircraft during the Monferrato maneuvers the week of 22 August, 1910. At least 12 aircraft were used during the maneuvers; they were a mix of 50-hp single-seaters and 70-hp two-seaters.

Two were assigned to the Flottiglia Aeroplani (Airplane Fleet) as part of the expedition to Libya. They reached Tripoli on 15 October, and on the 24th capitano d’artiglieria (artillery captain) Carlo Piazza made what is widely regarded as the world’s first combat sortie by an airplane, a one-hour reconnaissance flight; he later damaged his Bleriot on landing.

A two-seater and two 80-hp single-seaters also equipped the Tobruk squadron from March 1913, which was repatriated on 12 August.

In the following days, the Italians experimented with a variety of ways to use these aircraft, including missions at night (March 4,1912). They served alongside Nieuport 4s as part of the 1st Flottiglia di Aeroplani de Tripolia, which consisted of nine machines that undertook reconnaissance, bombing, and even leaflet-dropping operations during the Turko-Italian War.

A lists of firsts during the war in Libya include;

- first combat sortie on 22 October 1911

- first adjustment of naval fire on 28 October 1911

- first photographic reconnaissance on 23 February 1912

- first night combat sortie on 4 March 1912

In 1912 the Bleriot 11 was included among the types chosen for incorporation into the newly re-structured the air forces.

The next year SIT of Turin delivered 33 30-hp two-seaters followed by other variants in 1914 and 1915. Also, the first Bleriot 11-2 two-seaters were at last obtained from France in March 1912. Two-seaters were needed due to the observation, during the type’s deployment to Libya, that the pilot’s workload during reconnaissance missions was high enough to warrant carrying a second crew member.

In 1913 the following Squadriglias used Bleriot 11s:

1a Squadriglia (based in Turin-Mirafiori) 2a Squadriglia (Turin-Venaria Reale)

3a Squadriglia (Cuneo)

4a Squadriglia (Rome-Centocelle)

13a Squadriglia (Piacenza),

14a Squadriglia (Brescia)

Tobruk Squadriglia - one Bleriot 11-2 and two single seaters (possibly Bleriot 11 “Parasol”).

Ideally each Squadriglia would have five operational aircraft and two more in reserve.

When a Bleriot 11 crashed at Mirafori on 24 April 1914 after its wings detached, the military issued a flight ban while the airframes were examined.

First World War

When Italy entered the war there were 30 Bleriot 11s (plus seven in reserve) available. This does not include aircraft serving in the Aviano and Miraflori Schools.

The Bleriot 11s were with 1a, 2a, 3a, 4a, 13a, and 14a Squadriglias. They were assigned as follows:� 1st Gruppo: 1a, 2a, 3a, 13a, and 14a Squadriglias.

3rd Gruppo: 4a Squadriglia.

In 1915 the 1st Gruppo was assigned to the 3a Armata while the 4a Squadriglia was attached to the Venice Fortif Harbor Headquarters.

Thirty Bleriot Ils were assigned to the front but had be withdrawn as being unuseable by 1 December 1915, 2a, 5a, and 13a Squadrilias being the first to disband.

After their retirement form operational units, the surviving Bleriot Ils were relegated to training roles.

S.l.T.-built Bleriot 11 Parasol with 70-hp Gnome engine

Wingspan 9.20 m; length 7.80 m; height 2.95 m; wing area 18 sq. m

Empty weight 310 kg; loaded weight 480 kg Maximum speed: 110 km/h

S.l.T.-built Bleriot 11 Idro Floatplane with 90-hp Le Rhone

Wingspan 11.05 m; length 9.00 m; height 3.0 m; wing area 24 sq. m

Empty weight 500 kg; loaded weight 740 kg

Maximum speed: 95 km/h

One built

S.l.T.-built Bleriot 11-2 (Italian) Two-Seat Reconnaissance Plane with 70/80-hp Gnome

Wingspan 10.30 m. length 8.40 m, height 2.45 m (Alegis states 2.60 m), wing area 20.3 sq. m

Empty weight 345 kg; loaded weight 585 kg; payload 240 kg

Maximum speed: 95 km/h; endurance 3 hr 30 min; climb to 1,000 m in 18 minutes; climb to 2,000 m in 50 minutes

Armament Winchester carbines for the crew, flechettes, and bombs

47 built

Bleriot Biplane

Wingspan, 12.70 m; length, 9.15 m; height, 3.10 m; wing area, 38 sq m

Empty weight 400 kg; loaded weight 650 kg; payload, 250 kg

P.Grosz, G.Haddow, P.Shiemer Austro-Hungarian Army Aircraft of World War One

Bleriot Monoplanes

During the war, two or three Bleriot monoplanes were operated as primary trainers. One unnumbered machine, Bleriot IX w/n 931, was still flying as late as October 1918 at Flugpark 1.

Журнал Flight

Flight, April 22, 1911.

LONDON TO PARIS NON-STOP BY AEROPLANE.

TRULY can it be said that aviation history is being made at a marvellous rate, and it would seem that record cross-Channel flights are to mark the periods of that history. The year 1909 saw the famous flight of M. Bleriot from Calais to Dover. In 1910 the late Hon. C. S. Rolls made the double journey from Dover to Sangatte and back without a stop, while 1911 is likely to be remembered as the year in which Pierre Prier improved on the records by flying from London to Paris without breaking his journey. It is true the late Mr. J. B. Moisant succeeded in covering the space between the French and English capitals last year by way of the air, but it will be remembered that he made numberless stops - albeit they were unwilling ones - on the way, while his journey occupied a good many days owing to difficulties encountered on this side of the Channel. Not only is M. Prier's trip a record for cross-Channel work but it is also a world's record for a cross-country flight from point to point. That it should be possible for an aviator to set off at practically a moment's notice on a journey of 250 miles without making any very elaborate preparations is an extraordinary commentary upon the progress in aviation which has been accomplished during the past year. It is, in fact, what happened, for although the aviator had been thinking over the possibility of making such a trip for six weeks, the recent spell of bad weather had necessitated the temporary abandonment of the project. On Wednesday of last week, however, M. Prier was giving M. Norbert Chereau a trial run on one of the new Bleriot monoplanes at Hendon, when it was suggested that the conditions were favourable for a flight to Paris. The suggestion was acted on forthwith. M. Prier had his cross-Channel flyer brought out, got into readiness, and by a quarter-past twelve was in the air. When he had travelled only a little way, however, he found it was practically impossible to keep up the pressure in his petrol tank, and so returned to the aerodrome for this to be remedied, after having been in the air for about half an hour. At 1.30 p.m. the adjustments were completed, and at 1.37, to be exact, M. Chereau timed the aviator away for his journey to Paris.

Following a route which had been carefully prepared beforehand on a roller map, which was arranged in front of the pilot, the aeroplane winged its way round the suburbs on the north side of London, and then working eastward of the Metropolis, followed the Thames to Chatham, turning southward when past Canterbury, to Dover. From here, M. Prier steered across the Channel to Cape Grisnez, on reaching which point he turned and followed the coast to Boulogne, arriving there at 3.15, as he was more familiar with the landmarks on the route between there and Paris. Continuing his journey onwards to Abbeville and Beauvais without incident, he crossed the French capital, which was so enshrouded in mist that even the Eiffel Tower was not distinguishable, and sighting Issy, came down in front of the Bleriot sheds there at 5.33 p.m., being warmly welcomed by M. Louis Bleriot himself. Throughout the journey the Gnome-engined Bleriot behaved splendidly, and M. Prier had no difficulty in finding his way by the aid of the special map and a compass. When Hendon was left the wind was blowing slightly from the north-east, but at Dover it had veered to north-west. The only difficulties experienced were due to the mists passed through in England and a bank of fog encountered near Beauvais. The actual time taken for the trip of 250 miles was 3 hrs. 56 mins., so that the average speed maintained was in the neighbourhood of 64 miles an hour. During most of the journey M. Prier was at a height of about between 2,000 and 3,000 feet.

Flight, June 10, 1911.

PARIS-ROME-TURIN.

IN our last issue were just able to briefly announce that "Beaumont" was the first to actually arrive at Rome on Wednesday of last week. He made a magnificent flight from Nice, after having had a new motor fitted to his machine, A quarter of an hour's trial flight was indulged in as soon as the mechanics had finished their work, and then he set off at 3.57 a.m. He landed at Genoa at 6.47, and an hour later started off once more for Pisa, where he arrived at 9.40, landing on the horse racecourse in error. Realising his mistake, he afterwards restarted the machine and flew over to the proper aerodrome, where he landed an hour later. At ten minutes past twelve he left for Rome, and landed in the precincts of the Eternal City at eight minutes past three, his passage over the city being witnessed by His Holiness the Pope and Cardinal Merry del Val from a balcony of the Vatican.

Garros made a move from Pisa at 4.35 a.m., but had only progressed 60 kiloms. on his journey when he was forced to make a landing at Castagneto-Carducci. In coming down very suddenly from a height of 200 metres the machine was very badly smashed. Frey continued his journey from Genoa to Pisa, but in alighting at the latter place smashed his propeller and also damaged the chassis of his machine. Of the other competitors, Vidart advanced from Avignon to Nice, while Bathiat was brought down by motor troubles at Macon, after covering the 110 kiloms. from Dijon in 54 mins. Lieut. Lucca succeeded m getting from Lyon to Avignon

Flight, September 2, 1911.

AIR EDDIES.

Hendon habitues will be glad to hear that Frank L. Champion, who will be remembered by Hendonites as that delightfully droll "Candy Kid" who came across from Southern California to graduate at the Bleriot School, is doing really well out West at Los Angeles. He is now flying a Gnome-Bleriot, the machine purchased from Radley by Earle V. Remington at the Los Angeles aerodrome. In order to demonstrate to a Long Beach committee his ability to give exhibitions at the forthcoming midsummer carnival, Champion flew there from Los Angeles, a distance of roughly 20 miles, and circled over the town at a height of 1,500 feet. It is hardly surprising to hear that as a result of his flight, which, by the way, was his first since his return to the States, he has been engaged to fly at the Long Beach Carnival festivities. Since then he has succeeded in falling into the sea - accidentally, or for advertisement's sake, we wonder! That aviators are drawn from all sources is pretty well known. Champion formerly carried on a photographer's business at Long Beach.

Flight, September 9, 1911.

NEW WORLD'S RECORDS.

Garros Creates New Altitude Record - 13,943 ft.!

STILL the competition for the altitude record goes merrily on Lincoln Beachy's height of 11,578 ft. made at Chicago has now been put in the shade by the extraordinary performance of Garros, who on Monday, in the neighbourhood of St. Malo, went up on a Bleriot monoplane to a height recorded by his barograph as 4,250 metres, or 13,943 ft., subject to official recognition. The previous French record, and a world's record previous to Beachy's flight, was the 2,350 metres reached on August 5th by Capt. Felix.

Flight, October 7, 1911.

FROM THE BRITISH FLYING GROUNDS.

Portholme Aerodrome, Huntingdon.

ON Friday of last week some flying was seen at these grounds, when Mr. W. B. R. Moorhouse took the pilot's seat of his Gnome-Bleriot for the first time. He got off in 20 yards, and flew four times round the drome at an average altitude of 200 feet, his aneroid in one instance registering 300 feet. He finished up with a very neat landing, not bumping in the least. His success speaks well for Mr. Moorhouse's future, as it was his first attempt with a Gnome-Bleriot, and he had had but a very little previous practice with an old Anzani-Bleriot, which was available last year. On Saturday it was raining and blowing a couple of gales lashed together, and flying was out of the question,

Flight, October 14, 1911.

FROM THE BRITISH FLYING GROUNDS.

Portholme Aerodrome, Huntingdon.

MR. W. B. R. MOORHOUSE, after his essays the previous week, was last week making a series of remarkably successful flying trips. On the Monday, he, on his Gnome-Bleriot with Chauviere propeller, made four good flights in the morning, travelling well outside the aerodrome, in the afternoon putting up a further five flights, again outside the aerodrome, keeping well up at above 2,000 ft. or so. The next day he flew from Huntingdon to Northampton, accomplishing the distance (45 miles) in the half-hour, most of the time being at an altitude of fully 3,000 ft. Mr. Moorhouse is a fearless flyer, and merely took in Northampton, having steered there via Bedford, Turney and Yardley Hastings on route, during a visit to his parents' house, Spratton Grange, a few miles northward of Northampton. This was Mr. Moorhouse's first cross-country flight, and the machine he was using was the identical Bleriot on which Mr. Morison not so very long ago took a dip into the Channel near Folkestone. On his return journey to Huntingdon Mr. Moorhouse again passed over Huntingdon, and continued on by Wellingborough and Kettering, reaching Portholme at 3.5 p.m., having started a little after 2 p.m. from Spratton. On Wednesday and Thursday work was in progress on the new Radley-Moorhouse monoplane, but on Friday Mr. Moorhouse resumed his cross-country work by flying from Huntingdon to Northampton, where, after partaking of lunch, he struck out again for Brooklands, encountering en route some extremely gusty winds and fogs, although he rose to a height of 4,000 ft. to get away from this trouble. Saturday afternoon, testing was again the chief work on the R. and M. monoplane, which appears to be working very successfully, as he, during the day, was up on the machine and actually passed for his certificate on it. Mr. Morison subsequently had a flight round in the new machine and appeared to be well satisfied with its behaviour.

On Tuesday evening last Mr. Moorhouse left Brooklands in his Bleriot for Huntingdon, but running short of petrol near Cambridge, he came down at Parkers Piece, having made a magnificent gliding descent commencing at about Trumpington, two miles south of Cambridge. He flew on to Huntingdon on Wednesday morning at 6.30 a.m.

Flight, November 11, 1911.

AEROPLANES AT TRIPOLI.

MR. QUINTO POGGIOLI, who will be remembered by our readers as having taken his pilot's certificate in England under the Royal Aero Club's regulations, sends us some interesting details of the practical work being carried out in Tripoli in connection with the Italian-Turkish War. Mr. Poggioli writes :-

"On the 25th Oct. Capt. Piazza with his Bleriot, and Capt. Moizo on his Nieuport, observed three advancing columns of Turks and Arabs of about 6,000 men. The Italians, after receiving this information, could successfully calculate distances and arrange for their defence.

"On the day following, the 26th Oct., the battle of Sciara-Sciat took place, resulting in the loss to the Turkish Army of 3,000 men. During the battle two aeroplanes, Lieut. Gavotti with his Etrich and Capt. Piazza, were circling the air. The flights took place above the line of fire, so as to be able to direct the firing of the big guns from the battleship 'Carlo Alberto,' and also of the mountain artillery. The aeroplanes were often shot at by the guns of the enemy, but with no result. The only difficulty they had was caused by the currents of air caused by the firing of the big guns.

"Previously, on the 22nd Oct., Capt. Moizo when reconnoitering passed over an oasis, and, in order to observe better the movements of the enemy, descended to an altitude of about 200 metres, and in consequence the wings of his machine were pierced by bullets in six or seven places, and also a rib was broken.

"On November 1st Lieut. Gavotti (Etrich) flew over the enemy, carrying four bombs, carried in a leather bag; the detonator he had in his pocket.

"When above the Turkish camp, he took a bomb on his knees, prepared it and let it drop. He could observe the disastrous results. He returned and circled over the camp, until he had thrown the remaining three bombs. The length of his flight was altogether about 100 kiloms.

"The bombs used contained picrato of potassa, type Cipelli."

THE first official communication by one of the belligerents, in regard to the use of aeroplanes in actual warfare, has been issued by the Italian authorities, dated November 5th, from Tripoli. As a matter of historical record we reproduce the text in extenso as follows :-

"Yesterday Captains Moizo, Piazza, and De Rada carried out an aeroplane reconnaissance, De Rada successfully trying a new Farman military biplane. Moizo, after having located the position of the enemy's battery, flew over Ain Zara, and dropped two bombs into the Arab encampment. He found that the enemy were much diminished in numbers since he saw them last time. Piazza dropped two bombs on the enemy with effect. The object of the reconnaissance was to discover the headquarters of the Arabs and Turkish troops, which is at Sok-el-Djama."

Flight, November 18, 1911.

Aeroplanes in War.

THE Italian Army in Tripoli are now using three Bleriot monoplanes which have been in use in Italy for some time, one of them being flown by Captain Piazza, who is the Commander of the Aviation Section, and who will be recaused, membered as being the winner of the Italian Circuit during last summer (Bologne-Venise-Rimini and Bologne). The Italian Government has placed a further order for three more Bleriot monoplanes, and Captain Anostini is now at Etampes to see the trials of the machines, which are to be delivered this week.

Flight, December 30, 1911.

PARIS AERO SHOW.

L. Bleriot.

FOUR monoplanes are on view on this stand, the 70-h.p. two-seater, which Hamel has popularised in England, the familiar 50-h.p. cross-country model, a new 50-h.p. racing monoplane, and a new low horse-power monoplane, type XXVIII, designated the "Popular" type. Of these machines we are already familiar with the former two, and no description of them is necessary.

<...>

Principal dimensions, &c. :-

Cross-country type-

Length 25 ft.

Span 29 "

Area 165 sq. ft.

Weight 528 lbs.

Speed 60 m.p.h.

Motor 50-h.p. Gnome.

Price L860.

Flight, March 2, 1912.

Mr. Hewitt has a Rough Landing.

ON Saturday last Mr. Vivian Hewitt started on a flight with his Gnome-Bleriot from the Foryd Aerodrome, Abergele but when only about 100 feet up the petrol pipe broke and the engine stopped. He was just leaving the aerodrome at the time and had no chance to turn into it. The machine did a tail slide, then pancaked and afterwards started gliding. By that time he was only about 30 feet up and after hitting a ditch and bouncing along frightfully uneven ground the machine pulled up at the edge of another ditch. Fortunately nothing was broken, but it was necessary to dismantle the machine to get it back to the aerodrome.

Flight, March 16, 1912.

MY PARIS FLIGHT.

By HENRI SALMET, Chief Instructor of the Bleriot School, Hendon.

FOR some time past I have wanted to fly to Paris and back in one day, and also, as I should like to see M. Bleriot in Paris about business matters. I think, it being fine, on Thursday the 7th, I will go. The night before I paint on the wings of my Bleriot some varnish that keep the fabric tight and make it waterproof, and later I telegraph to the coastguard at Eastbourne to telephone me in the morning if the weather is good. Next morning early the message arrive. The coastguard say the Channel is clear of fog, so I get ready. The fuselage of my Bleriot had already been covered in with fabric and waterproofed so as to make a float and keep me up if my engine fail and I go in the water. Round me I put an inner tyre from one of the school machines which I blow up. I run my engine and it go very well, so I wave my hand and I am away.

When I left here it was exactly 7.45, with little wind behind me. The wind increased, and after about a quarter of an hour the wind was much more stronger, and my speed was about half as much again. At Eastbourne I was 1,200 metres high and about 2 miles over the sea, but the wind was too gusty. I came back, and I took 3,000 ft. more high, and that took me 13 mins. After that, I started again on my way to Paris, and I flew for 1 hr. 40 mins. without seeing anything other than the clouds. The sight at that height was most marvelous - I think absolutely the best something I have seen in my life. At that height the clouds were more like big snowy mountains, and flying through them was the most curious experience that could happen to anyone. A glance behind showed my wake in a swirl of fog disturbed by the propeller and the passage of the machine. So cold was it in the clouds, that I had constantly to increase my high so that I could get above them. This brought me to a height of between 6,000 and 7,000 ft., and as I could not see the sea, steering had to be entirely done by compass. This was hard to do, for the wind, although fairly steady, set the monoplane rolling slowly, and the compass needle kept swinging continually about ten degrees each side of the true line. This had to be accounted for. From points that I had recognised over English soil, I calculated that my speed was something over 130 kiloms. an hour, and from the time I got my last glimpse of the earth, I flew for 1 hr. 40 mins., and then from my speed calculated just about where I ought to find myself. Here I thought I ought to descend, as I wanted to make sure that my compass was guiding me correctly, and that I was on my right way.

For a long time I see nothing but the wings of my machine. I came down to 200 metres in order to distinguish points that I wanted to find. Then I flew round in big circles for 17 minutes, at last recognising a castle that I had marked on my map. Picking up the adjacent railway line, I reached Gisors. Here it was clearer, and I gradually elevated to 2,000 metres. Although it was possible to distinguish land marks, I did not look down once as I was so occupied in fighting the gusty wind that I did not trouble to do so, knowing full well my compass was steering me correctly. I saw the Eiffel Tower after a long struggle, and the sight gave me very big pleasure because it is the first cross-country flight I have make. I see Issy from 1,500 metres, and commenced my vol plane.

To battle against the remous caused by the big houses, I have to descend very steep to keep up my speed. Gusts rapidly struck me from below, and had I not gripped the cabane with all my might deserted because I arrived before my telegram. On landing I took from my machine the little can of paraffin I always carry, and washed over the engine - my good engine, which had brought me all the way from London without any trouble. All the more pleasure because I myself look after the engine, no one else touch it. Then I go to find someone, and I find a guardian of the aerodrome with a mechanic from the Astra Company, and I asked him "Where are the Bleriot hangars?" and he say "Opposite there." As I turned to go to the sheds he say to me "Can you tell me any news of the English aviator who should fly from London to Paris?" and I say "The English aviator is me." Then we shake hands. Then he say "If you are the English aviator you speak French very well indeed. What is your name?" and I said "Henri Salmet of the Bleriot School in England." Then I go to the Bleriot sheds and get the mechanics to fetch my machine and put it safe in the hangar. I ask for M. Bleriot's telephone number to ring him up and tell him I arrived. I telephone and he speak himself, and he say "Why do you not send a telegram?" At that moment the telegraph boy must have come into his office, for he say "the telegram has just arrived now." I say "When can I see you M. Bleriot?" and he say "I see you about three or four " but I reply "I shall be far off by then." He say "Why?" I say "Because I want to get back to London to-day." Then he came down to Issy in a car with M. Leblanc, and some reporters.

M. Bleriot seem very please. He say "Bon jour, Salmet. Toutes mes relicitations! Par on avez vous passe." I say that I had come by the way I had chosen, and that I had tell him some time before. He is very happy that I do cross the channel at the wide part, from Eastbourne to Dieppe - thing that had not been done since aviation existed. In his great joy he grasp my both hands, and squeeze so hard that he hurt much. And M. Leblanc also. Then we have lunch at the Cafe Syndicat des Aviateurs. They say to me, there is too much wind, and you cannot return. But I did not pay attention to that, as no matter what the struggle I had big confidence in my Bleriot, my Gnome, and my wonderful Levasseur propeller, which give so much pull and runs so smoothly. It is the best I have try. With my three faithful friends, my machine, my motor, my propeller, the wind have no fear for me. So at 2.15 with the anemometre at 34 kilometres to the hour, I start once more. The start is not alone, because the ground is used by the soldiers, but I go to ask at the Commandant to let me start. He say "Yes, with pleasure," and he took his soldiers in a good place to give me plenty of room, and I go. I start straight on my line, but the ground is not much large and when I am over the houses I am very low, and the wind put me sometime in very bad situation. I am very long to take my high, because sometime I am 200 metres up, and then I come down again with the wind.

After I have crossed the Seine I have less remous, and I go more high. Since this time the wind is much more regular, but so strong that I take nearly four hours to make 220 kiloms. I am very cross against the weather, because I am obliged to land at Berck Plage with my petrol tank nearly empty.

As soon after my landing I start to find petrol. That take me too long time, and after that it is too late to start. I had wanted very much to sleep on English ground that night. A friend help me find petrol and oil, and after filling the tanks, I go to take something to eat with him. As he knew I wanted to start early next morning, he locked me in my bedroom that night, so that I should not go without him seeing me. At five o'clock he come in my room and give me a good cup coffee. I took it, and soon after I go with him to where the machine is tied up. I give a little exhibition fly, and land on the shore. Then before they let me go I have to sign many postcards, and many people take photographs of the machine.

Starting again just before ten, the wind was blowing about 32 kiloms., and was a little foggy. I fly for two miles, and my engine start missing. My magneto is wrong. I put it right, and I start again at 10.12. Then I go across the Channel from Cap Grisnez to Folkestone very fast indeed. I am across the other side in fifteen minutes, and there the wind come more badly. Having no map, and as the compass rock very badly, I keep over the main road. The wind and rain beat very hard in my face. I don't like to land because I like to put my machine in my shed at Hendon before landing anywhere. But the wind and rain coming always more strong, I think it more wise to land than to continue. It take me a quarter of an hour to go four miles. Then, seeing a good landing ground on my left, I come down, and find I am at Chatham. If I am very cross against the weather I meet there the best people I have ever met. All people is ready to help me for anything. They all want to give me something to eat. I go with Mr. Sills, who has a room where I can be quiet, for I am very tired after the struggle. The schoolmaster there makes a meeting in my honour, and I go there in the evening, and they give me a big tri-colour bouquet, and after much shouting I have to sign many postcards.

The next morning I start at 6.15 in a very bad wind towards London. My cloche is always moving; but all is well until I fly into some fog. I remember the Regent's Park happening, and I think it better to descend than to continue and land in some place where the Aero Club would not like it. Near Maidstone I have to land in a champ labore, and I break a piece off my propeller. My good friends from Hendon soon bring me another one, and we put it on. The weather is not favourable to start, but I am so hurry to come to Hendon that I look with a bad eye at those who say the weather is too bad. I go on again; but soon after my motor stopped, and I have to descend in a football field near Beckton gasworks. I land very deep from 800 metres, because ground is small. I see I am going to hit a goal-post, so I pull lack my cloche to clear it. My speed slackens as I rise, and a gust comes and blows me right over. I am sad, for it is the first smash I have ever had since I started to learn to fly. To me the smash itself was nothing, but to think that it should happen after those days of struggling grieved me much. However, the smash was done properly; and so disgusted was I at not being able to get to Hendon, that I walked away without looking to see my machine. There I found friends who were very amiable to me, principally William Marsh, whom I shall not forget. The smash did not hurt me, for here I am, with only a little cut on my knuckle. Then - Mais c'est tout! Voila la fin de mon pauvre et triste voyage!'

LONDON-PARIS RECORD FLIGHT.

SALMET'S magnificent flight on Thursday of last week from the Hendon aerodrome to Paris, in a wind averaging the whole way a velocity of 30 miles an hour, brands him as one of the foremost airmen of the day - a second Vedrines. His aim was to effect the return journey between the two capitals in one day, and to shorten his course he elected to cross the channel at its widest part, from Eastbourne to Dieppe - a feat which has hitherto never been accomplished. For nearly two hours he was obliged to steer by his compass alone, being above the clouds. That he succeeded in maintaining his true course under such difficult conditions is indeed eloquent testimony of his ability as a pilot. From the time he left Hendon to the time he landed at the parade ground of Issy-les-Moulineaux near Paris, 3 hours 16 mins. elapsed. Of this time 13 minutes was occupied at Eastbourne in gaining altitude, and for 17 minutes he had to circle near Gisors in order to determine his whereabouts. Subtracting these 30 minutes from his total time, his true time for the direct flight was 2 hours 46 mins. His real average speed between the two capitals, a distance of 220 miles, in direct flight was therefore 79 miles an hour - a truly wonderful speed when one takes into consideration the fact that it was Salmet's first cross-country journey.

Starting on his return journey from Issy-les-Moulineaux at 2.15, he fought his way against wind and rain to the coast, but, through lack of petrol, had to descend at Berck Plage at 5.55. Here he thought it advisable to remain the night, in spite of his determination to reach English soil if possible that day. The following morning he set off once more, and following the French coast line to Cap Grisnez, which he reached at eleven o'clock, he steered towards the English coast, effecting the crossing of the Channel in 15 mins. Continuing on, he was obliged to descend at Chatham, owing to the violent wind and rain. Early on the following morning he started again, but at Maidstone was forced to descend through encountering a bank of fog. In landing, the tip of his propeller, a Levasseur, was damaged, and another one had to be obtained from Hendon. Once more he started, but before he had got far his motor suddenly stopped, and he was obliged to plane down into a football field not more than a few hundred yards from the Royal Albert Docks. To land in such a small ground necessitated a steep vol plane. To avoid a goal post he had to elevate sharply, and in consequence lose speed to such an extent that the wind got the better of him, and his monoplane came heavily to earth. It was considerably damaged, but happily, barring the shock, Salmet was little the worse.

Elsewhere in this issue will be found an account of this trip to Paris from the pen of the aviator, M. Henri Salmet, himself.

Flight, April 20, 1912.

MISS QUIMBY FLIES THE CHANNEL.

ALTHOUGH Miss Harriet Quimby has made an enviable reputation for herself as a capable pilot in America, her native country, she has not been very well-known on this side of the Atlantic, and no doubt few of our readers who read the announcement in FLIGHT a week or so back that she was coming to Europe, looked for her so soon to make her mark by crossing the Channel. Contrary to what one would expect, the feat was carried through without any fuss or elaborate preparations, and only a few friends, including Mr. Norbet Chereau and his wife and Mrs. Griffith, an American friend, knew that the attempt was being made and were present at the start. Miss Quimby had ordered a 50-h.p. Gnome-Bleriot, which arrived from France on Saturday, and was tested on Sunday by Mr. Hamel. On Tuesday morning, as previously arranged, after Mr. Hamel had taken the machine for a preliminary trial flight, Miss Quimby, who had been staying at Dover under the name of Miss Craig, took her place in the pilot's seat, and at 5.38 left Deal, rising by a wide circle and steering a course, by the aid of the compass, for Cape Grisnez. Dover Castle was passed at a height of 1,500 feet, and by the time the machine was over the sea, it was at an altitude of about 2,000 feet. Guided solely by compass, Miss Quimby arrived above the Grisnez Lighthouse a little under an hour later, and making her way towards Boulogne she came down at Equihen by a spiral vol plane not far from the Bleriot sheds.

To Miss Quimby, therefore, belongs the honour of being the first of the fair sex to make the journey, unaccompanied, across the Channel on an aeroplane; and, appropriately enough, as the first crossing of an aeroplane by a "mere man" was on a Bleriot machine, her mount was of that type. Miss Trehawke Davies, it will be remembered, was the first lady to cross the Channel in an aeroplane, but she was a passenger with Mr. Hamel on his Bleriot monoplane.

Flight, April 27, 1912.

FLYING THE IRISH CHANNEL.

Now that well over a week has passed since Mr. D. Leslie Allen set out from Holyhead at about seven o'clock in the morning of Thursday of last week, to cross the Irish Channel, and no news of his whereabouts have come to hand, it certainly seems that it is our sad lot to mourn another British life, sacrificed - we think again quite unnecessarily - in the practising of the sport. It was on the previous day, the Wednesday, that he with Mr. Corbett Wilson, set out from Hendon to fly in company to Dublin. There was no wager between them as to who should get there first, as has been generally seated. They simply had a feeling that they would like to visit their native island by the new method of locomotion, and they both started off in friendly rivalry to fly there together. At that time it was thought by those at the aerodrome that the flight was an unusually risky one for such comparatively inexperienced pilots to attempt. Further, so hastily had the trip been arranged that no precautions were made against the possibility of having to descend in the sea. They both left Hendon soon after half-past three p.m. on Wednesday, and Allen, following the London and Northwestern Railway line, arrived at Chester about half-past six in the evening, after landing some ten miles the other side of Crewe to ascertain his whereabouts, Corbett Wilson landed the same evening at Almeley, about fifteen miles northwards of Hereford.

Just after six on the following morning Allen started from Chester and passing over Holyhead an hour afterwards, flew out to sea. He has not been seen or heard of since. His friend, Corbett Wilson, left Almeley at half-past four that afternoon and was forced to land some few miles further on at Colva in Radnorshire. On Sunday morning early he set off again and this time reached Fishguard, leaving again at six o'clock on the following morning, Monday, and flying across St. George's Channel in the direction of Wexford.

One hour and forty minutes was occupied in crossing the Channel and a landing was made at Crane, two miles from Enniscorthy, the trip being the first occasion that the strip of water separating Ireland from the main land has been entirely crossed by aeroplane. It will be remembered that Mr. Loraine's attempt in 1910 failed by some 300 yards.

Mr. Vivian Hewitt also has the intention of attempting the crossing to Ireland, but his route is to be from Holyhead to Dublin across the Irish Sea. At the time of writing he is waiting at Holyhead for favourable weather. He left Rhyl at 5 a.m. on Sunday morning and after remaining up for an hour and twenty minutes was forced to land at Plas in Anglesey. His flight was made at an average of quite 5,000 ft., for he says he could distinctly see over Snowdon. The wind was boisterous in the extreme and he testifies to the fact that had he remained up much longer he would undoubtedly have been ill, so much was he tossed about. The section from Plas to Holyhead was flown on Monday morning, starting from the former place at about 9.30. Mr. Vivian Hewitt has his machine in Lord Sheffield's grounds and will continue his flight as soon as conditions prove favourable.

Flight, June 1, 1912.

HOW TO OPERATE A BLERIOT MONOPLANE.

By EARLE L. OVINGTON, BLERIOT PILOT.

THE following article, published in the columns of our American contemporary, Aero, is from the pen of one who has probably flown a greater distance over American soil in a Bleriot monoplane than any other pilot. He graduated at the Bleriot school at Pau, in the south of Prance, and amongst his successes was the winning of the L2,000 prize offered by the Boston Globe for the fastest crosscountry flight over a course embracing three States :-

"The systems of control of almost all practical aeroplanes are essentially the same. In other words actual flying machines of the present day employ a vertical rudder to steer in the horizontal plane, one or more elevators to steer in the vertical plane and some form of manually operated lateral control device. To be sure one machine may steer by means of a cross-bar operated by the feet, while another will operate through a wheel, as in an automobile. For lateral stability one manufacturer prefers to use one contrivance, while another employs a different one. The fundamental principle, however, of all machines is practically the same.

"The principal thing in operating an aeroplane of any description, is to become so acquainted with the control that the manipulation of the machine in actual flight is absolutely intuitive or instinctive on the part of the aviator.

"Psychologists tell us that we have two minds, our objective and our subjective mind. The objective part of our mental make-up is that which is used in ordinary everyday life; we might term it our reasoning mind. It takes time for this part of our mentality to work.

"Our subjective mind is that part of our mind which is ordinarily beyond the control of the individual. Some designate the operation of the subjective mind as intuition, while others say that it is instinctive. At any event, operations controlled by the subjective mind are usually performed without any conscious thinking on the part of the individual.

"Unquestionably the best aviators of the present day are subjective flyers; that is, they do not stop to think every time they re the control levers of their aeroplane. And the whole object of training is to so educate the student that the movement of his control levers is absolutely instinctive, requiring no conscious effort.

"I shall describe the operation of a Bleriot monoplane, because it is the machine with which I have had the most experience, although at many of the meets during the past season, I have flown the Curtiss biplane. In justice to the Curtiss machine, I will say that it is the most instinctive form of control with which I am acquainted, for none of the movements of the control are at a variance with what one would naturally do under the circumstances. However, if a man can fly a ticklish monoplane, he can fly about anything with a little additional practice.

"One of our photographs shows a detail view of the cock-pit of my Bleriot monoplane. This machine is driven by a 70-h.p. seven cylinder Gnome rotating motor, and is of the latest racing type. Its speed in still air is more than 70 miles per hour.

"Seated comfortably upon a little chair-like seat, fitted with a four-inch hair cushion, my feet rest upon a cross-bar to which are attached the steel wires running to the vertical rudder at the tail of the machine. If I wish to go to the left, a pressure on the left foot is all that is required, on the other hand, if I wish to turn to the right, it is only necessary for me to press the right foot. Certainly this is not very difficult.

"The lever which you see in the picture, surmounted by a small wheel, is the lever to which the wires are attached that run to the elevator immediately in front of the rudder at the tail of the machine. Wires also run from this lever to the wings so that wing-warping may be introduced to obtain lateral stability. Although there is a wheel at the top of this lever, it does not turn, but simply forms a convenient method of grasping this lever with either one hand or the other or both.

"Racing across the ground it is only necessary for me to pull the lever towards me, after the speed has increased sufficiently, for the machine to rise rapidly. Placing the lever in a vertical position the machine flies horizontally. If I wish to descend I push the lever forward, which process elevates the tail, and down I come. Neither operation is very difficult.

"The most dangerous part of controlling an aeroplane of the present day is in maintaining what is called lateral stability, that is, keeping the aeroplane on an even keel. In the Bleriot this is accomplished by wing-warping. If my machine tips to the left, I push the control over to the right, which process increases the angle of incidence on the low wing and decreases the angle of incidence on the high wing, with the result that the lift on the low wing is greater than on the high wing, and there is a force introduced which tends to bring the machine back to its horizontal position. To operate the lateral control mechanism is what takes practice.

"Often, in emergency cases, all three controls must be actuated at once. For instance, assume I am flying horizontally and strike a so-called 'air-hole,' which tilts me towards the left at a dangerous angle. I do three things. First, I rush the rudder over with my right foot to increase the speed, and hence the lift of my left or lower wing. Incidentally, the speed of the right wing is lessened and its lift consequently decreased. Second, I put my lateral control lever hard over to the right. Third, I push my elevator control forward to make the machine drop. The resulting increase of speed gives my controls greater effect. In active practice, the vertical lever actuating the lateral stability and elevator devices is moved diagonally forward and to the right, thus incorporating the two movements into one.

"It is necessary for those who wish to learn to operate any aeroplane to do considerable 'grass-cutting' at first, in order that they may be thoroughly acquainted with the control of their machine and also become accustomed to rushing through space at a high velocity. It may seem easy to steer a machine on the ground, from one point to another, but until you have tried it in a monoplane, you do not realize how difficult it is. Even to an experienced operator, it is more difficult to steer a straight course on the aerodrome, when the machine is rolled along the ground than when flying. This is due to the fact that the rudder is designed for operation at a mile a minute, and not for slower speed on the ground; hence the surface is not very great. Incidentally a machine flying in the air offers very much less resistance to turning than one wheeling along the ground.

"After one has become thoroughly acquainted with the machine, he may venture to take hops into the air.

"The principal thing about which I wish to warn embryo aviators is not to make sudden movements of their control. In order to rise, for instance, it is not necessary to pull the control towards you six or eight inches, as usually one or two inches is all that is necessary. I have seen so many students get into a machine, give the control-lever a pull towards them, and then practically stand the machine on end in mid-air. This results in a bad tail-slide, and the machine is often reduced to toothpicks and the aviator seriously injured. Be particularly careful, therefore, to try out the various controls carefully, moving them only a short distance at a time until the desired result is accomplished.

"After the student is able to make hops and keep his machine level, he is then ready to make a more extended flight. And now I wish to give another word of warning.

"Before I ever went off the ground in any of my flights, however rushed I was, or however impatient was the audience, I always took plenty of time to tune up and examine my machine. First, I looked at my big Gnome motor. I turned it over slowly, and felt of the play of each exhaust-valve. I examined carefully the bolts which held the main supporting steel strips to the landing-chassis and the wings, in order to see that these fastenings were perfectly secure. The tension of these strips is also important, and should be practically uniform. Very often a distortion of the wings makes one of these strips tight and the other loose. There is only one thing to do, and that is to make the tension uniform before venturing into the air. Don't forget to glance at the upper supporting wires, as often a turnbuckle may become loosened; and although these wires do not support the weight when the machine is in the air, still they are of great importance.

"The leading edge of the wings should be absolutely parallel with the trailing edge. Squat down behind each wing and glance along these edges, and if they are not parallel adjust the upper or lower wires until they are. This is of the utmost importance for the machine will not be on an even keel when the control is at a central position unless the two wings are adjusted perfectly equal. Don't forget to take a look at the tail and see that the supports holding it in position are firm, and the nuts on the bolts secure.

"After you have learned actually to fly, get up in the air a good height and stay there. Remember it is not falling that injures an aviator, but the sudden stop and his contact with Mother Earth. That saved my life a good many times and I've had some side slips where I fell 500 ft. or more. I would not be here, talking to the readers of this journal if I had not been flying pretty high. Personally, I have always been of the opinion that high flying is the safest, although many aviators do not agree with me. It always made me nervous to see a man taking the sparrows off the trees or brushing the cobwebs from the chimneys of surrounding houses. I never felt right until I was up from 2,000 to 5,000 ft., and the higher I got the better I felt. Don't forget the higher you are the better chance you will have of making a safe landing, if your motor stops accidentally. When you're flying low, the chances are there is going to be a smash if your motor ceases to operate in the air.

"Speaking of the motor stopping, just remember that as soon as it ceases to operate, you must bring in the force of gravity to keep up your flying speed. In other words, point the nose of your machine down instantly; never mind how high you are or what you will bump into." [In view of the disclosure M. Bleriot made recently, it is clear that the action of pointing the nose of the machine downwards too violently, should the engine stop, is not advisable on account of the reversal of pressure set up in the wing surfaces. We would rather it read, "point the nose of your machine down surely but not too suddenly."]

"You don't gain anything by keeping the machine in a horizontal plane, for it will fall anyhow, and it is much better to have it fall on the glide than to have it fall vertically. In the latter case, the use of the control is lost, and a serious accident will result.

"Be very careful in rising that you do not stall the machine. Remember that it is the rapid speed forward which supports your aeroplane, and enables your control to operate properly, just as soon as you try to climb at too steep an angle the resistance becomes so great that your speed drops off quickly, and soon a point is reached when your controls go out of commission almost entirely. If you are near the ground you make a pancake landing, in which case, your machine must go into the hangar for a long job of repairs. I always had an inclinometer, which is simply a spirit lever, to tell at what angle I was climbing. I found by experience the angle which I could employ in order to climb the fastest, and however excited I was, or however important it was for me to climb rapidly, I never exceeded this angle. Several times I have been sorely tempted to do so, but in each case have resisted the temptation.

"Remember that in banking a monoplane on a turn, it always tends to hank too much unless an extremely short turn is made. In other words in turning to the left, for instance, a slight pressure on the left foot serves to throw you around in that direction. Immediately the speed of your left wing decreases, while the speed of your right wing increases, and the machine banks. In order to correct this and not to bank too much, you must move your vertical control to the right, or as the French term it - cloche, meaning bell in French, owing the bell-shaped portion at the bottom of the lever. Banking is absolutely necessary to take a turn properly, but be careful that you do not bank too much for the inward component of the lift of your plane will be greater than the centrifugal force and a side-slip to the inside of the circle will result.

"Speaking of side-slips, you've got to look out for them in a monoplane. A biplane does not have a tendency to side-slip anywhere near as badly as a monoplane. Let a high-speed monoplane get side-slipping badly and you're going to have your hands full in bringing it up to an even keel. The trick is - do not let it get too far over, but apply your corrective the instant the machine tilts to an undesirable angle.

"There are exceptions when an experienced aviator can disobey this rule. For instance, in taking one of the turns at Chicago, these turns were very short indeed, we had to throw the machines up to 60 or 70 bank in order to get around them in good shape. Ordinarily this would be a dangerous process, but if the aviator remembers to let his machine fall - that is point the elevator downward, while taking the turn - it is comparatively safe.

"Never bank on a rise and never bank deeply unless you let the machine glide down. The latter rule is not absolutely necessary, but always safe.

"A monoplane is far more sensitive than a biplane, and hence extreme care is necessary in its control, but after it is thoroughly mastered I believe that a monoplane is no more dangerous than a biplane, and is much more fun to operate. Incidentally if you're going into it from an exhibition standpoint, it is faster than a biplane and hence your chances for winning first place are greater. If I had had a biplane only to depend upon, during the past season, I probably should have lost money, rather than made it. As it was, I have no complaint to make, for in five months I made enough to keep me going for a while without serious worry as to where my next slice of bread is coming from.

"I have often been asked during the past season to what I owe my success. In the first place, I had what I consider the best machine made for my purpose of exhibition flying. In the second place, I hired two of the best mechanics that money could buy, and I gave them all the tools that they could work with, never hurrying them on an important job, however impatient my manager might be or the waiting public. I never went out on a flight until I had carefully inspected the machine, and I did not let curious people bother me with questions so as to distract my attention when I performed this important operation.

"I will not say that I did not take fool chances, for every aviator that does exhibit flying has got to fly when the time comes. I believe in 'playing the game' and when you don't want to play it give it up. I have never yet disappointed an audience. A man that goes into exhibition flying must go in with his eyes open and realize what he is up against. However, I always had my machine perfect before it left the ground, and I could, therefore, rely on it ninety-nine cases out of a hundred. And my reasoning must have been correct, for I made more than one hundred flights and have never broken one stick in the machine.

"To sum up therefore, my advice to young aviators is to - first, get the best machine you can; second, give it the very best care and attention. If you are not in a position to do so yourself hire someone who can. Thirdly, carefully inspect the machine before every flight. Fourth, don't let the machine get very far from its normal position, but correct any tendency to tilt or side-slip instantly. Fifth, never come anywhere near stalling the machine in mid-air. Sixth, if the motor stops come down to your natural gliding speed instantly, and then think about where you're going to land. Don't look around for a landing place first and then try to operate your aeroplane, for by that time it may be beyond your control."

Flight, June 13, 1912.

FOREIGN AVIATION NEWS.

Resistance Tests with Bleriot Machines.

IN our last issue we briefly referred to some tests made by the French Military authorities with a view to ascertaining the strength required for various aeroplane parts, and in this issue we are able to give a couple of photographs illustrating the method of carrying out the tests. A special train was fitted up by the Compagnie du Nord, and on this a Bleriot monoplane was mounted in such a manner that while the train was in motion the machine could take all possible positions which are taken in ordinary flight.

By this method no risk of accident to the pilot was entailed. With Capt. Charet and Lieut. Maillot alternately taking the pilot's seat, the monoplane was made to assume the different positions of ascent, descent, and warping as quickly and roughly as it could possibly be done in an endeavour to realise the very worst conditions under which the machine might have to fight its way through a gale. During these tests, which were carried out during the early morning of three days, the train was driven at a speed of 72 miles (115 kiloms.) an hour over a five kilom. stretch of railway in the vicinity of Survilliers, near Chantilly. It will be observed that the speed of 72 miles (115 kiloms.) is 12 miles in excess of the calculated speed of the aeroplane, and of course the pressure increases very considerably under such conditions. The tests were carried out under the supervision of Lieut. Col. Estienne, of the Technical Department of the Vincennes Military Aviation Establishment, and they were witnessed by Col. Hirschauer, Permanent Inspector of Military Aeronautics, Col. Bouttieaux, Director of Military Aeronautics at Chalais Meudon and many other military officers and aviators. All parts of the Bleriot machine stood the test perfectly, as was afterwards testified by the military officers present.

THE KING AND AVIATION.