Книги

Журнал

Flight за 1912 г.

748

Журнал - Flight за 1912 г.

Flight, April 6, 1912.

AVIATION IN AUSTRALIA AND PIONEERS.

By J. R. DUIGAN.

I WAS very interested to see in FLIGHT of March 16th an article on "Aviation in Australia and Pioneers," and as the subject is evidently of interest I am sending you a brief account with photos of my own early efforts.

1st attempt, 1909. A pair of wings only. Result, not a success.

2nd effort, early 1910. 1/2-size Wright glider (Photo enclosed). Flown in strong winds, anchored to 120 yards of fencing wire. Left ground successfully and rose 4 or 5 ft.

<...>

AVIATION IN AUSTRALIA AND PIONEERS.

By J. R. DUIGAN.

I WAS very interested to see in FLIGHT of March 16th an article on "Aviation in Australia and Pioneers," and as the subject is evidently of interest I am sending you a brief account with photos of my own early efforts.

1st attempt, 1909. A pair of wings only. Result, not a success.

2nd effort, early 1910. 1/2-size Wright glider (Photo enclosed). Flown in strong winds, anchored to 120 yards of fencing wire. Left ground successfully and rose 4 or 5 ft.

<...>

Flight, April 6, 1912.

AVIATION IN AUSTRALIA AND PIONEERS.

By J. R. DUIGAN.

I WAS very interested to see in FLIGHT of March 16th an article on "Aviation in Australia and Pioneers," and as the subject is evidently of interest I am sending you a brief account with photos of my own early efforts.

1st attempt, 1909. A pair of wings only. Result, not a success.

2nd effort, early 1910. 1/2-size Wright glider (Photo enclosed). Flown in strong winds, anchored to 120 yards of fencing wire. Left ground successfully and rose 4 or 5 ft.

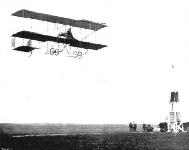

3rd effort. This machine was commenced beginning of 1910, and was on Farman lines, built entirely by myself and fitted with a 4-cyl. vertical air-cooled engine, 20 h.p., built in Melbourne by J. E. Tilly. After sundry experiments on July 16th, 1910, I did, amongst others, a hop of 24 ft. Various improvements, such as chain drive in place of belt, water-cooled heads, higher compression, and finally larger cylinders gradually increased the length of flights till at the end of September, 1910, I managed flights of about 100 yards (see Melbourne Leader, October 1st). On October 7th, 1910, before half-adozen spectators, I successfully covered a distance of 196 yards, rising about 12 it. high (Melbourne Argus, October 8th, 1910). These flights, as far as I know, were the first to be made in Australia by an Australian-built machine. They were published in various papers practically all over Australia as such and were never contradicted. Public opinion may be judged from the fact that I received an offer of L100 to make a flight from the Melbourne Cricket Ground in December on the day of a big cycle meeting. This I was forced to refuse, the ground being totally unsuitable. M. Cugnet, as mentioned in your article, agreed to make the attempt, but owing to the ground and want of power, it ended disastrously.

On January 25th, 1911, I gave a short exhibition flight for the benefit of the Sporting Editor and the Photographer of the Melbourne Argtis. This flight was evidently appreciated, as they gave five columns and photos in the next Saturday's issue, January 28th, 1911. In April, at the Bendigo Easter Fair, I exhibited the machine, and on the last day showed it running in the arena, a ground 160 yards long, in a hollow, and surrounded by tents and buildings. Although there was a 12-14 m.p.h. wind side on, I just managed to get off the ground, land, and pull up without damaging anything. Shortly afterwards May 3rd, at the Bendigo Race-course where there was more room. I did several flights, straights and semicircles of about three-quarters of a mile before about 1,000 spectators. These were the first flights ever seen in Bendigo and it was also the first time I ever had more than 400 or 500 yards of descent ground. These flights paid me very well, and covered the cost of a good bit of experimenting.

Last exhibition flight was on May 31st, when before Mayor Hedges, representing the Defence Department, Mr. W. F. Marshall, Hon. Sec, Aerial League of Australia (Victorian Section), and others at Mia Mia, I did several flights of about half a mile. My brother also flew the machine about 600 yards at 10 or 12 ft., this being only the tecond time he was ever on it. Wind 12-15 miles per hour by anemometer.

All these flights, judged by present-day performances, seem of course very puny, but considering the many difficulties, that all the work was done single-handed, and that total breakages were only a buckled wheel, a wing tip leading edge, and an upright broken, the results were I think encouraging. Anyway, it was, in the words of the great poet, "A small thing but mine own."

AVIATION IN AUSTRALIA AND PIONEERS.

By J. R. DUIGAN.

I WAS very interested to see in FLIGHT of March 16th an article on "Aviation in Australia and Pioneers," and as the subject is evidently of interest I am sending you a brief account with photos of my own early efforts.

1st attempt, 1909. A pair of wings only. Result, not a success.

2nd effort, early 1910. 1/2-size Wright glider (Photo enclosed). Flown in strong winds, anchored to 120 yards of fencing wire. Left ground successfully and rose 4 or 5 ft.

3rd effort. This machine was commenced beginning of 1910, and was on Farman lines, built entirely by myself and fitted with a 4-cyl. vertical air-cooled engine, 20 h.p., built in Melbourne by J. E. Tilly. After sundry experiments on July 16th, 1910, I did, amongst others, a hop of 24 ft. Various improvements, such as chain drive in place of belt, water-cooled heads, higher compression, and finally larger cylinders gradually increased the length of flights till at the end of September, 1910, I managed flights of about 100 yards (see Melbourne Leader, October 1st). On October 7th, 1910, before half-adozen spectators, I successfully covered a distance of 196 yards, rising about 12 it. high (Melbourne Argus, October 8th, 1910). These flights, as far as I know, were the first to be made in Australia by an Australian-built machine. They were published in various papers practically all over Australia as such and were never contradicted. Public opinion may be judged from the fact that I received an offer of L100 to make a flight from the Melbourne Cricket Ground in December on the day of a big cycle meeting. This I was forced to refuse, the ground being totally unsuitable. M. Cugnet, as mentioned in your article, agreed to make the attempt, but owing to the ground and want of power, it ended disastrously.

On January 25th, 1911, I gave a short exhibition flight for the benefit of the Sporting Editor and the Photographer of the Melbourne Argtis. This flight was evidently appreciated, as they gave five columns and photos in the next Saturday's issue, January 28th, 1911. In April, at the Bendigo Easter Fair, I exhibited the machine, and on the last day showed it running in the arena, a ground 160 yards long, in a hollow, and surrounded by tents and buildings. Although there was a 12-14 m.p.h. wind side on, I just managed to get off the ground, land, and pull up without damaging anything. Shortly afterwards May 3rd, at the Bendigo Race-course where there was more room. I did several flights, straights and semicircles of about three-quarters of a mile before about 1,000 spectators. These were the first flights ever seen in Bendigo and it was also the first time I ever had more than 400 or 500 yards of descent ground. These flights paid me very well, and covered the cost of a good bit of experimenting.

Last exhibition flight was on May 31st, when before Mayor Hedges, representing the Defence Department, Mr. W. F. Marshall, Hon. Sec, Aerial League of Australia (Victorian Section), and others at Mia Mia, I did several flights of about half a mile. My brother also flew the machine about 600 yards at 10 or 12 ft., this being only the tecond time he was ever on it. Wind 12-15 miles per hour by anemometer.

All these flights, judged by present-day performances, seem of course very puny, but considering the many difficulties, that all the work was done single-handed, and that total breakages were only a buckled wheel, a wing tip leading edge, and an upright broken, the results were I think encouraging. Anyway, it was, in the words of the great poet, "A small thing but mine own."

AVIATION IN AUSTRALIA. - Mr. Duigan pancaking at Bendigo Race Course on May 3rd, 1911, after doing about three-quarters of a mile. He had to steer between two trees, hence his proximity to the one seen.

AVIATION IN AUSTRALIA. - On the left, Mr. J. R. Duigan flying over Bendigo Race Course on May 3rd, 1911. The machine had been in the air for about 200 yards when photograph was taken, and the crowd are facing the machine, out of the picture. On the right, Mr. Duigan is seen flying at second attempt in 12 m.p.h. wind on May 31st, when he landed safely.

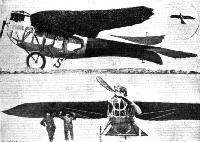

Lieut. Gregory, R.N., testing the new Etrich monoplane at the Royal Aero Club's Eastchurch flying grounds.

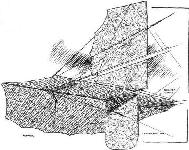

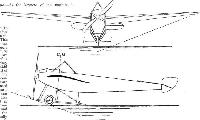

The Etrich 1912 military monoplane, from the side and front. Inset the machine is seen in flight. One of the Etrich machines has just been acquired by the British Government.

Flight, July 13, 1912.

AIR EDDIES.

Messrs. Jacob Lohner and Co. is an Austrian firm with works at Vienna, where they produce Etrich monoplanes and machines of their own design. They are entering a tractor biplane, known over there as the Arrow-Plane Dreadnought, equipped with a 120-h.p. Austro-Daimler motor. It was on an identical machine that Lieut. Von Blaschke broke the world's altitude record with passengers at the Vienna flying meeting last month by taking two besides himself up to 3,500 metres, and by taking one single passenger to a height of 4,260 metres.

Lieut. Von Blaschke himself is probably going to fly the machine at the competitions at Salisbury.

Flight, July 20, 1912.

THE MILITARY COMPETITION - THE MACHINES.

THE LOHNER ARROWPLANE DREADNOUGHT (ARMY TYPE).

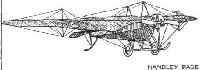

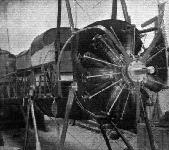

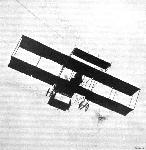

THIS interesting entrant from Germany is termed "Arrow-plane" from the fact that, when flying overhead, its silhouette resembles closely the form of an arrow. Its wings, set back Dunne fashion, might be the arrow's head, its fuselage the shaft.

Of the machine, two main types are made at the Vienna works of Messrs. Jacob Lohner and Co. - an "Army type " and a "Navy type." They may readily be distinguished from one another, in that the Army type has a direct coupled tractor; the tractor of the Navy type is centred some distance above the motor, and withal, geared down.

It is a biplane of the former type that will be flown in the Military Competition at Salisbury. To Lieut, von Blaschke will be entrusted the piloting. Besides the photographs we print, we have been able to glean from Mr. Cecil E. Kny, who represents the manufacturers here in England, a few details.

The upper plane spans nearly 53 ft., and by virtue of its shape is designed to give the machine an excellent modicum of stability - both in a lateral and longitudinal sense. Its large span, however, does not make it too unwieldly for military service, for the extensions of the top plane, each 10 ft. in length, may be folded down, allowing the biplane to be conveniently housed in a shed just over 33 ft. wide. An entirely covered-in streamline fuselage forms the backbone of the machine. In it are located the three that the machine is designed to carry - the mechanic directly behind the motor (a 120-h.p. Austro-Daimler), and the pilot and observer-passenger some distance behind the planes, where their view is clearest. The fuel tanks are arranged between. Terminating the fuselage is the tail, the shape and general arrangement of which can be gathered from our photographs. Like the greater part of German machines, it is provided with a land brake at the tail to decelerate it quickly on landing.

In addition to its abilities for climbing - the machine holds world's records in passenger altitude, as we recalled last week - it has a very excellent gliding angle. For a biplane its speed is unusually high. It is estimated to average 70 m.p.h.

Main characteristics:-

Motor 120-h.p. Austro-Daimler

Span 53 ft. nearly

Overall length 31 ft.

Weight, empty 1,540 lbs.

Useful load 600 lbs.

Speed 70 m.p.h.

AIR EDDIES.

Messrs. Jacob Lohner and Co. is an Austrian firm with works at Vienna, where they produce Etrich monoplanes and machines of their own design. They are entering a tractor biplane, known over there as the Arrow-Plane Dreadnought, equipped with a 120-h.p. Austro-Daimler motor. It was on an identical machine that Lieut. Von Blaschke broke the world's altitude record with passengers at the Vienna flying meeting last month by taking two besides himself up to 3,500 metres, and by taking one single passenger to a height of 4,260 metres.

Lieut. Von Blaschke himself is probably going to fly the machine at the competitions at Salisbury.

Flight, July 20, 1912.

THE MILITARY COMPETITION - THE MACHINES.

THE LOHNER ARROWPLANE DREADNOUGHT (ARMY TYPE).

THIS interesting entrant from Germany is termed "Arrow-plane" from the fact that, when flying overhead, its silhouette resembles closely the form of an arrow. Its wings, set back Dunne fashion, might be the arrow's head, its fuselage the shaft.

Of the machine, two main types are made at the Vienna works of Messrs. Jacob Lohner and Co. - an "Army type " and a "Navy type." They may readily be distinguished from one another, in that the Army type has a direct coupled tractor; the tractor of the Navy type is centred some distance above the motor, and withal, geared down.

It is a biplane of the former type that will be flown in the Military Competition at Salisbury. To Lieut, von Blaschke will be entrusted the piloting. Besides the photographs we print, we have been able to glean from Mr. Cecil E. Kny, who represents the manufacturers here in England, a few details.

The upper plane spans nearly 53 ft., and by virtue of its shape is designed to give the machine an excellent modicum of stability - both in a lateral and longitudinal sense. Its large span, however, does not make it too unwieldly for military service, for the extensions of the top plane, each 10 ft. in length, may be folded down, allowing the biplane to be conveniently housed in a shed just over 33 ft. wide. An entirely covered-in streamline fuselage forms the backbone of the machine. In it are located the three that the machine is designed to carry - the mechanic directly behind the motor (a 120-h.p. Austro-Daimler), and the pilot and observer-passenger some distance behind the planes, where their view is clearest. The fuel tanks are arranged between. Terminating the fuselage is the tail, the shape and general arrangement of which can be gathered from our photographs. Like the greater part of German machines, it is provided with a land brake at the tail to decelerate it quickly on landing.

In addition to its abilities for climbing - the machine holds world's records in passenger altitude, as we recalled last week - it has a very excellent gliding angle. For a biplane its speed is unusually high. It is estimated to average 70 m.p.h.

Main characteristics:-

Motor 120-h.p. Austro-Daimler

Span 53 ft. nearly

Overall length 31 ft.

Weight, empty 1,540 lbs.

Useful load 600 lbs.

Speed 70 m.p.h.

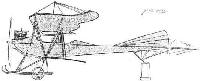

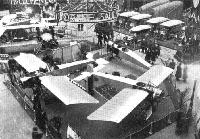

THE MILITARY COMPETITION MACHINES. - Three-quarter front view of the Arrow-plane Dreadnought, the biplane entered by Messrs. Jacob Lohner and Co., of Vienna. It is rumoured that great things may be expected of this machine.

THE MILITARY COMPETITION MACHINES. - Rear view of the Arrow-plane Dreadnought, the biplane entered by Messrs. Jacob Lohner and Co., of Vienna.

Flight, January 20, 1912.

"VIKING I."

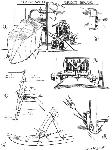

"VIKING I" is a biplane, the first of that type to materialise from the ever-active brain of Mr. H. Barber. Although he has been so long connected with the single-deck type, the germ of this conception was sown long since in the days before he left Salisbury Plain to continue his experimental work in the north of London.

That he should have seen fit to produce such a machine at the present time is yet more evidence of the clearness with which he grasps the ever-changing aspect of the development of aviation in this country, for it is evident to all students that the leading constructors of the world are now concentrating their attention on the development of two types of aeroplanes rather than identifying themselves with a single speciality.

"Viking I" differs from his previous productions in that it flies head first, also it is characterised as a biplane, by the possession of a definite fuselage or covered-in body, which has the engine in front and the pilot's seat just between the main planes. In its detail construction there is that same careful attention to minor matters and sound principle that has given the workmanship of the Aeronautical Syndicate, Ltd., who carry out all Mr. Barber's constructive work in addition to that of their numerous other clients, a leading place in the industry of aeroplane construction. Nor can two opinions exist as to the soundness of the design, whether viewed from the purely aerodynamical standpoint, whether examined in the light of ability to comply with the exacting requirements, or whether considered from the point of view of the pilot's safety.

Consequent with the adoption of the fuselage is the distinctly sound practice of disposing the engine in front of the pilot, a system which was originated in this country and the advantages of which are just becoming apparent to our foreign confreres.

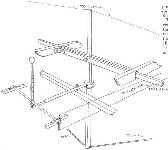

The main body is constructed throughout of silver spruce excepting in the region of the engine, where, in view of the extra strains that are placed upon it, ash is employed. Mounted at its forward extremity, with its inlet pipe extending towards the direction of advance, is the motor, a 50-h.p. Gnome. By means of a short propeller shaft and twin chains arranged Wright-fashion the power is transmitted to the two A.S.L. tractors, that transform into effective thrust the rotary motion of the engine.

A well formed torpedo front of sheet aluminium is arranged over the engine and this together with a slanting screen of the same material at the rear, protects the pilot and passenger from any oil or exhaust fumes thrown off by the motor. Apart from being used for these screens and for the construction of the novel balancers with which the machine is equipped, aluminium has been absolutely discarded as a medium of construction, its place being taken by sheet steel. Throughout its whole length the fuselage is covered in, at the forward end by the metal torpedo front and at the rear by fabric, so that its passage through the air may give rise to a minimum of disturbance.

Directly underneath the top surface is the cock-pit, about four feet in length by three feet in width, where are accommodated side by side, the pilot and passenger. The former, who sits on the right-hand side, has before him a vertical wheel, mounted on a vertical column which latter is pivoted at its base so that it can be moved away from or towards the operator. Rotation of the wheel laterally controls the inter-connected balancers on either side, and a to-and-fro movement of the column as a whole controls the attitude of the aeroplane in flight. Placed forward and on either side of the control column is a pair of pedals operating the vertical rudder. In full view of both pilot and passenger is a dashboard where are arranged an altimeter, a compass, a revolution indicator, a watch, and oil and petrol gauges to aid in cross-country work, while, convenient to the right-hand of the pilot are the engine controls. On the control wheel itself is a subsidiary switch by which the engine may be cut off or started again.

Not the least feature of note regarding this section of the machine is the comfort that is afforded the human complement. Constructors, in the midst of abstruse calculations and constructional problems, are apt to overlook such secondary points as this. Not so the Viking engineer, he provides the most comfortable of bucket seats, and completes the snug appearance of the cock-pit by upholstering it in leather, and covering the floor with a square of Turkey carpet.

Tanks for the storage of enough fuel to keep the Gnome motor in operation for six hours are arranged on either side of the body, and glass gauges proceeding from them into the interior keep the pilot well informed as to the actual state of his supply. Feed is by gravity.

At the rear end of the body is disposed the tail-unit whereby control over the machine in the two dimensions of direction and altitude is maintained. Hinged to the rear of a horizontal surface of streamline section, 9 ft. in span by 2 ft. 9 in. in width, is a flap, that serves the function of elevator.

A noticeable feature regarding the design of the tail is that the elevator may be removed by the mere unscrewing of a nut and locknut, and the withdrawal of a single thin steel rod that serves as a common core to the several hinges from which this organ depends. Each side of the flat tail surface is applied to the body much in the same fashion as a monoplane wing, its two booms fitting into sockets, while it is held in correct position by four steel wires. This system commends itself in that the whole of the tail unit can, when necessary, be dismantled in a minimum of time with a minimum of trouble.

Mounted at right angles to the horizontal tail surface is the directional rudder, half above and half below the fuselage. This is pivoted at its average centre of pressure and is operated by means of a crank arranged in the interior of a covered-in body. A small wooden skid, swivelling about the base of the rudder mast and connected to the body at its upper end by means of a shock absorber affords protection for the tail unit against contact with the ground.

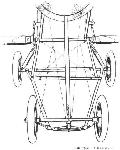

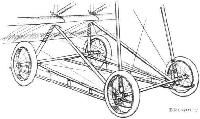

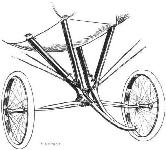

The cellule, 31 ft. in span is composed of two super-imposed single-surfaced planes, separated by a gap of 5 ft. 3 ins. Viewed from the front, its centre section, of 6 ft. span, is horizontal, while the two end sections, each of 12 ft. 6 ins. in span are given a characteristic arched dihedral angle, the horizontal end projection of which is approximately nine inches. Two triangular skeletons of steel tubing, securely mounted between the planes and braced thereto by steel tension wire, support the two tractors, their centres being separated by a distance of 14 ft.

Both planes are perfectly rigid except for a small degree of flexibility that is allowed the trailing edge by virtue of its overhang. Probably the most novel and interesting feature of the machine is the system of balancing employed. The balancers, being arranged at ever-changing angles of incidence, according to the will of the pilot and the conditions of the machine in flight, automatically and simultaneously assume a camber best suited to the angle of incidence at which they are at the moment working. The surfaces of these organs are formed of an aluminium alloy reinforced with spring steel ribs, a clever but simple sliding arrangment allowing for the alteration in the length of the top surface according to whether it is concave or convex. Its conception is so extremely simple that until one remembers that it is usually the most simple things that are the most difficult to discover, one is surprised that it has not been thought of before. The advantages that this system possesses on the score of its efficiency are undoubted. As regards the undercarriage, not only is it of novel design but possesses the attributes of simplicity, adaptability and strength, combined with a low factor of head resistance. Each wheel, as can be seen from one of the photographs, is mounted between a pair of cantilevers, constructed from heavy gauge sheet and channel steel. These latter are universally jointed at their centres to an enormously strong forged steel fitting, to which are assembled the ash chassis struts proceeding from the lower plane. The upper end of each cantilever is anchored to the body of the machine by a pair of rubber shock absorbers. Uniting the two wheels is a tie rod, and diagonal wires carrying miniature shock absorbers are intoduced to keep them parallel to the geometrical axis of the machine. To prevent any damage resulting from too steep a landing a skid is fitted to the extreme nose of the body and two similar skids, but of smaller dimensions, are arranged at each end of the cellule to protect the wing tips. These are allowed universal motion and are governed by shock-absorbers.

Weighing 800 lbs., the machine has been designed for a speed of 55 miles per hour, and to carry its double human load for a non-stop flight of six hours. In the matter of speed, the intentions of the designer have been more than realised, for in practical tests that have recently taken place, this 55 miles has been handsomely exceeded. The Viking biplane undoubtedly represents a considerable advance en the admittedly sound work of the A.S.L. establishment, and if sheer merit goes for anything these days, it should pave the way for an exceedingly prosperous business year.

"VIKING I."

"VIKING I" is a biplane, the first of that type to materialise from the ever-active brain of Mr. H. Barber. Although he has been so long connected with the single-deck type, the germ of this conception was sown long since in the days before he left Salisbury Plain to continue his experimental work in the north of London.

That he should have seen fit to produce such a machine at the present time is yet more evidence of the clearness with which he grasps the ever-changing aspect of the development of aviation in this country, for it is evident to all students that the leading constructors of the world are now concentrating their attention on the development of two types of aeroplanes rather than identifying themselves with a single speciality.

"Viking I" differs from his previous productions in that it flies head first, also it is characterised as a biplane, by the possession of a definite fuselage or covered-in body, which has the engine in front and the pilot's seat just between the main planes. In its detail construction there is that same careful attention to minor matters and sound principle that has given the workmanship of the Aeronautical Syndicate, Ltd., who carry out all Mr. Barber's constructive work in addition to that of their numerous other clients, a leading place in the industry of aeroplane construction. Nor can two opinions exist as to the soundness of the design, whether viewed from the purely aerodynamical standpoint, whether examined in the light of ability to comply with the exacting requirements, or whether considered from the point of view of the pilot's safety.

Consequent with the adoption of the fuselage is the distinctly sound practice of disposing the engine in front of the pilot, a system which was originated in this country and the advantages of which are just becoming apparent to our foreign confreres.

The main body is constructed throughout of silver spruce excepting in the region of the engine, where, in view of the extra strains that are placed upon it, ash is employed. Mounted at its forward extremity, with its inlet pipe extending towards the direction of advance, is the motor, a 50-h.p. Gnome. By means of a short propeller shaft and twin chains arranged Wright-fashion the power is transmitted to the two A.S.L. tractors, that transform into effective thrust the rotary motion of the engine.

A well formed torpedo front of sheet aluminium is arranged over the engine and this together with a slanting screen of the same material at the rear, protects the pilot and passenger from any oil or exhaust fumes thrown off by the motor. Apart from being used for these screens and for the construction of the novel balancers with which the machine is equipped, aluminium has been absolutely discarded as a medium of construction, its place being taken by sheet steel. Throughout its whole length the fuselage is covered in, at the forward end by the metal torpedo front and at the rear by fabric, so that its passage through the air may give rise to a minimum of disturbance.

Directly underneath the top surface is the cock-pit, about four feet in length by three feet in width, where are accommodated side by side, the pilot and passenger. The former, who sits on the right-hand side, has before him a vertical wheel, mounted on a vertical column which latter is pivoted at its base so that it can be moved away from or towards the operator. Rotation of the wheel laterally controls the inter-connected balancers on either side, and a to-and-fro movement of the column as a whole controls the attitude of the aeroplane in flight. Placed forward and on either side of the control column is a pair of pedals operating the vertical rudder. In full view of both pilot and passenger is a dashboard where are arranged an altimeter, a compass, a revolution indicator, a watch, and oil and petrol gauges to aid in cross-country work, while, convenient to the right-hand of the pilot are the engine controls. On the control wheel itself is a subsidiary switch by which the engine may be cut off or started again.

Not the least feature of note regarding this section of the machine is the comfort that is afforded the human complement. Constructors, in the midst of abstruse calculations and constructional problems, are apt to overlook such secondary points as this. Not so the Viking engineer, he provides the most comfortable of bucket seats, and completes the snug appearance of the cock-pit by upholstering it in leather, and covering the floor with a square of Turkey carpet.

Tanks for the storage of enough fuel to keep the Gnome motor in operation for six hours are arranged on either side of the body, and glass gauges proceeding from them into the interior keep the pilot well informed as to the actual state of his supply. Feed is by gravity.

At the rear end of the body is disposed the tail-unit whereby control over the machine in the two dimensions of direction and altitude is maintained. Hinged to the rear of a horizontal surface of streamline section, 9 ft. in span by 2 ft. 9 in. in width, is a flap, that serves the function of elevator.

A noticeable feature regarding the design of the tail is that the elevator may be removed by the mere unscrewing of a nut and locknut, and the withdrawal of a single thin steel rod that serves as a common core to the several hinges from which this organ depends. Each side of the flat tail surface is applied to the body much in the same fashion as a monoplane wing, its two booms fitting into sockets, while it is held in correct position by four steel wires. This system commends itself in that the whole of the tail unit can, when necessary, be dismantled in a minimum of time with a minimum of trouble.

Mounted at right angles to the horizontal tail surface is the directional rudder, half above and half below the fuselage. This is pivoted at its average centre of pressure and is operated by means of a crank arranged in the interior of a covered-in body. A small wooden skid, swivelling about the base of the rudder mast and connected to the body at its upper end by means of a shock absorber affords protection for the tail unit against contact with the ground.

The cellule, 31 ft. in span is composed of two super-imposed single-surfaced planes, separated by a gap of 5 ft. 3 ins. Viewed from the front, its centre section, of 6 ft. span, is horizontal, while the two end sections, each of 12 ft. 6 ins. in span are given a characteristic arched dihedral angle, the horizontal end projection of which is approximately nine inches. Two triangular skeletons of steel tubing, securely mounted between the planes and braced thereto by steel tension wire, support the two tractors, their centres being separated by a distance of 14 ft.

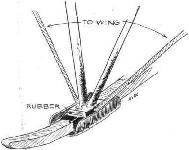

Both planes are perfectly rigid except for a small degree of flexibility that is allowed the trailing edge by virtue of its overhang. Probably the most novel and interesting feature of the machine is the system of balancing employed. The balancers, being arranged at ever-changing angles of incidence, according to the will of the pilot and the conditions of the machine in flight, automatically and simultaneously assume a camber best suited to the angle of incidence at which they are at the moment working. The surfaces of these organs are formed of an aluminium alloy reinforced with spring steel ribs, a clever but simple sliding arrangment allowing for the alteration in the length of the top surface according to whether it is concave or convex. Its conception is so extremely simple that until one remembers that it is usually the most simple things that are the most difficult to discover, one is surprised that it has not been thought of before. The advantages that this system possesses on the score of its efficiency are undoubted. As regards the undercarriage, not only is it of novel design but possesses the attributes of simplicity, adaptability and strength, combined with a low factor of head resistance. Each wheel, as can be seen from one of the photographs, is mounted between a pair of cantilevers, constructed from heavy gauge sheet and channel steel. These latter are universally jointed at their centres to an enormously strong forged steel fitting, to which are assembled the ash chassis struts proceeding from the lower plane. The upper end of each cantilever is anchored to the body of the machine by a pair of rubber shock absorbers. Uniting the two wheels is a tie rod, and diagonal wires carrying miniature shock absorbers are intoduced to keep them parallel to the geometrical axis of the machine. To prevent any damage resulting from too steep a landing a skid is fitted to the extreme nose of the body and two similar skids, but of smaller dimensions, are arranged at each end of the cellule to protect the wing tips. These are allowed universal motion and are governed by shock-absorbers.

Weighing 800 lbs., the machine has been designed for a speed of 55 miles per hour, and to carry its double human load for a non-stop flight of six hours. In the matter of speed, the intentions of the designer have been more than realised, for in practical tests that have recently taken place, this 55 miles has been handsomely exceeded. The Viking biplane undoubtedly represents a considerable advance en the admittedly sound work of the A.S.L. establishment, and if sheer merit goes for anything these days, it should pave the way for an exceedingly prosperous business year.

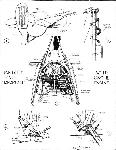

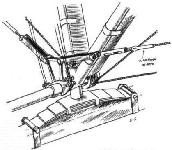

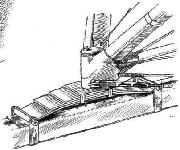

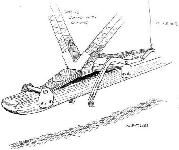

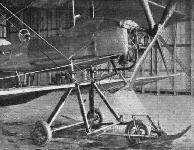

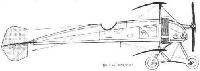

THE VIKING BIPLANE. - Half-side view, giving an idea of its general arrangement. Horatio Barber's last design before the company closed in 1912.

THE VIKING BIPLANE. - The illustration on the left is that of the tail unit; on the right that of the novel metal warping balancers with which the machine is furnished.

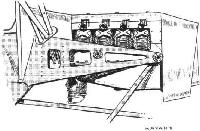

Detailed view of the front of the new Viking biplane. - The mounting of the Gnome motor, the details of the landing gear, of the forward skid, and of one of the twin tractors are clearly shown.

DETAILS OF THE VIKING BIPLANE. - On the left the arrangement of the controls in the pilot's cockpit. Note the petrol gauge in the interior of the body. The photograph on the right illustrates the details of the landing gear.

Flight, April 13, 1912.

AIR EDDIES.

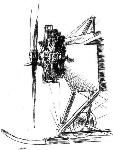

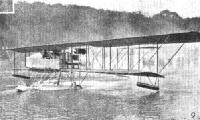

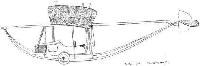

Sippe is getting on very nicely with the experiments with Commander Schwann's AVRO hydro-biplane, tests of which he is superintending at Barrow. On Tuesday of last week he had the machine out and made several short flights. The machine has now been fitted with floats of Duralumin at Messrs. Vickers works. Sippe's chief trouble seems to be to know how to avoid the propeller becoming chipped through contact with the spray thrown up. The ends of the propeller have been bound, but this precaution is not apparently quite satisfactory.

Flight, April 20, 1912.

AIR EDDIES.

When one comes to weigh up matters, one cannot but agree that the results obtained by Sippe on the Avro hydro-biplane constitute something of a record, of which we Britishers should be proud. The machine is the result of British brainwork, it, including the engine, all-British throughout, and is being flown by a British pilot under the direction of a British officer, who is, out of patriotism, financing the tests himself. It compares very favourably with foreign aquaplanes when a British biplane that has already seen much service, of 310 square feet of supporting surface, and fitted with an engine nominally rated at 35-h.p., but giving more by virtue of drilling auxiliary ports, can get off the water after a run of under a hundred yards. Sippe was up 200 feet on Friday of last week, in spite of his engine temporarily missing fire somewhat badly.

AIR EDDIES.

Sippe is getting on very nicely with the experiments with Commander Schwann's AVRO hydro-biplane, tests of which he is superintending at Barrow. On Tuesday of last week he had the machine out and made several short flights. The machine has now been fitted with floats of Duralumin at Messrs. Vickers works. Sippe's chief trouble seems to be to know how to avoid the propeller becoming chipped through contact with the spray thrown up. The ends of the propeller have been bound, but this precaution is not apparently quite satisfactory.

Flight, April 20, 1912.

AIR EDDIES.

When one comes to weigh up matters, one cannot but agree that the results obtained by Sippe on the Avro hydro-biplane constitute something of a record, of which we Britishers should be proud. The machine is the result of British brainwork, it, including the engine, all-British throughout, and is being flown by a British pilot under the direction of a British officer, who is, out of patriotism, financing the tests himself. It compares very favourably with foreign aquaplanes when a British biplane that has already seen much service, of 310 square feet of supporting surface, and fitted with an engine nominally rated at 35-h.p., but giving more by virtue of drilling auxiliary ports, can get off the water after a run of under a hundred yards. Sippe was up 200 feet on Friday of last week, in spite of his engine temporarily missing fire somewhat badly.

HYDRO-AEROPLANE EXPERIMENTS AT BARROW. - On the left Commander Schwann's machine, an Avro hydrobiplane, leaving its dock, with Sidney V. Sippe at the lever. On the right the machine is seen skimming the water just prior to taking the air, with its tail well up and the elevators just moved in the position for ascent.

Flight, November 23, 1912.

AIR EDDIES.

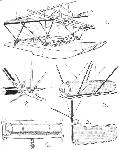

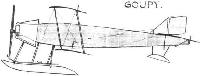

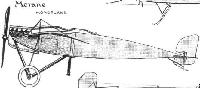

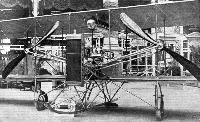

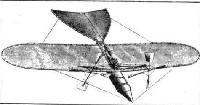

Quite an interesting machine has made its appearance at the Shoreham aerodrome. It is a monoplane which has been built to the designs of Lieut. R. Burga of the Peruvian Navy by Messrs. A. V. Roe and Co., whose flying school, it will be remembered, took up its quarters there some time since. From the photograph of the machine we are able to reproduce this week, it will be noticed that it is novel in having two vertical rudders, one above and the other below the fuselage, just forward of the pilot's cockpit. It is to these rudders that the maintenance of the craft's lateral stability has been entrusted, for no provisions have been made so that the pilot can control this by wing warping. The wings themselves are constructed on a principle that enables them to vary their camber according to the speed at which it is desired the machine should fly. With Lieut. Burga's permission we hope to be able to review this machine in a future issue.

It is of unusual interest to hear that Mr. H. Barber, whose opinions on matters relating to aviation are so highly valued, left suddenly for Constantinople a week ago yesterday.

Flight, November 30, 1912.

AIR EDDIES.

Since last week the new Burga monoplane at Shoreham has been undergoing its preliminary tests. It has proved very fast, and from the extremely short run that it takes before leaving the ground, it seems that the specially shaped wings are, in practical test, giving the efficiency that they exhibited when tested in miniature in the laboratory. The peculiar rudders above and below the fuselage that our last week's photograph showed are only a temporary measure for obtaining stability, for a device will be embodied in the design whereby stability will be controlled automatically

AIR EDDIES.

Quite an interesting machine has made its appearance at the Shoreham aerodrome. It is a monoplane which has been built to the designs of Lieut. R. Burga of the Peruvian Navy by Messrs. A. V. Roe and Co., whose flying school, it will be remembered, took up its quarters there some time since. From the photograph of the machine we are able to reproduce this week, it will be noticed that it is novel in having two vertical rudders, one above and the other below the fuselage, just forward of the pilot's cockpit. It is to these rudders that the maintenance of the craft's lateral stability has been entrusted, for no provisions have been made so that the pilot can control this by wing warping. The wings themselves are constructed on a principle that enables them to vary their camber according to the speed at which it is desired the machine should fly. With Lieut. Burga's permission we hope to be able to review this machine in a future issue.

It is of unusual interest to hear that Mr. H. Barber, whose opinions on matters relating to aviation are so highly valued, left suddenly for Constantinople a week ago yesterday.

Flight, November 30, 1912.

AIR EDDIES.

Since last week the new Burga monoplane at Shoreham has been undergoing its preliminary tests. It has proved very fast, and from the extremely short run that it takes before leaving the ground, it seems that the specially shaped wings are, in practical test, giving the efficiency that they exhibited when tested in miniature in the laboratory. The peculiar rudders above and below the fuselage that our last week's photograph showed are only a temporary measure for obtaining stability, for a device will be embodied in the design whereby stability will be controlled automatically

A NEW MONOPLANE AT SHOREHAM. - This machine, which incorporates a new idea in obtaining stability, has been built to the designs of Lieut. R. Burga by Messrs. A. V.Roe and Co. Further reference to it will be found in the "Eddies."

The Burga Monoplane at Shoreham in November 1912 with H. R. Simms in the rear cockpit and Lt Burga in the front.

The Burga Monoplane at Shoreham in November 1912 with H. R. Simms in the rear cockpit and Lt Burga in the front.

Flight, March 30, 1912.

THE NEW AVRO BIPLANE.

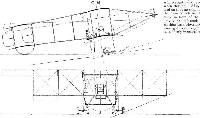

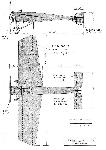

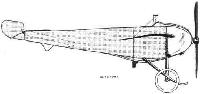

EXCEPTING that the general disposition of its respective parts is the same, the new Avro biplane can hardly be recognised as a modification of the little machine on which Pixton attained his early successes and demonstrated the practicability of carrying a passenger cross-country with an engine of as low horse-power as 35.

Although it is in effect an original model to most of those who keenly follow the trend of design in this country, it is, in reality, several months old, for it was an almost identical machine that the Avro firm supplied to Mr. J. Duigan in September last. The only points of difference in the two machines are that, this present machine being a two-seater, a more powerful motor is installed, and dimensions are slightly increased throughout.

The triangular section body of the early machine has been superseded by one of rectangular section, built to an approximate streamline form, and so deep in the region of the cockpit that much head resistance and much personal discomfort of the pilot and passenger are avoided by virtue of the fact that only their heads emerge from its depths through the well-padded openings on top. Other advantages does this deep form of fuselage possess. The lower plane may be attached to it in a manner very similar to the attachment of monoplane wings; the chassis struts may be considerably shortened, thus making for more robustness in the landing gear. To facilitate transport the body may be dismantled into two sections. The crossbracing of the fuselage - it is of the ordinary girder type - is the same standard Avro system that has already been explained and illustrated in these columns.

A point worth mentioning in connection with the body is that its top surface is flat, and when the machine is in level flight is, theoretically, horizontal. To preserve its lines it is covered in by metal sheeting in the front, and by fabric to the rear.

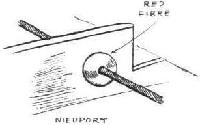

The undercarriage needs little description, for it must be admitted that except for the central skid, and the front pair of struts fashioned from wood, and the steel disc wheels employed, it is identical with the Nieuport chassis. Rubber cushions are introduced between the struts and the central skid to further assist in deadening landing shocks.

When the machine first appeared at Brooklands there were some doubts as to whether this type of chassis would "stand up to its work" fitted to a passenger-carrying biplane. However, as far as the tests have gone it has proved eminently satisfactory. So doubts may, for the time being, be dispelled.

The main planes are rectangular, and have an aspect ratio of over 7 1/2, a feature which, coupled with the modified form of Phillips' cross-section employed, must have a most beneficial effect on their efficiency. In their bracing only eight struts are employed, these being fitted and riveted into welded steel sockets. Warping is employed for the maintenance of lateral balance.

In cross-section the planes have little curvature on the under surface, and have the peculiarity that the underside of the trailing-edge is horizontal in flight. Provisions have been made so that in quite a short space of time the machine may be turned into a monoplane. Virtually a double-purpose machine, it will be able to serve either as a weight carrier or a speedy scout. And speed it does exhibit - it must average at least 60 m.p.h.

Steel tubing is solely employed in the construction of the skeleton of the tail. This organ is purely directional, while elevation and depression is regulated by a pair of hinged flaps, operated through levers made from sheet steel.

Control is maintained by universal levers by either pilot or his passenger, the latter of whom is seated well forward in the body at the centre of gravity, so that his extra weight need not interfere with the balance of the machine.

Two little celluloid windows have been let into the floor boards in order that both will be able to see what is directly beneath them.

A 60-80 h.p. E.N.V. motor direct coupled to a 10-ft. Avro propeller provides the forward thrust.

Altogether the new Avro biplane is a decided advance on anything their works have hitherto produced. As for its efficiency it is only necessary to mention that on test on Saturday last it attained an altitude of 1,000 feet, in a little over live minutes. 2,000 feet was reached, with a heavy passenger aboard, in 13 minutes.

Flight, August 10, 1912.

THE MILITARY AEROPLANE COMPETITION - THE MACHINES.

THE AVRO BIPLANE.

THIS machine is one of the most remarkable of those flying at Salisbury, for the fact that it is the only one of the competition machines that allows the pilot and passenger to be totally enclosed and so completely protected from the rush of air. It is an interesting fact with this new Avro biplane that, with the side windows open the only wind felt is one which comes from the side when turning and banking. As will be seen by the photographs we publish this week, the fuselage completely fills the gap between the main planes. It is approximately streamline in side elevation, and its section may be represented by a tall vertical panel. The body is surprisingly narrow. Where the pilot and passenger sit it is only sufficiently wide to give them free movement. At the extreme front it is only 15 inches wide, a dimension which is obtainable by the use of a 60-h.p. vertical Green engine. The planes are identical with those fitted to the machine already supplied to the War Office. On the "all enclosed" biplane one deck is fitted to the extreme top of the fuselage, and the other to a point near the bottom. The warping wires pass from the top plane through slots in the lower, round a phosphor bronze four-grooved pulley attached to the end of the skid. It has been so arranged that a warp of eighteen inches at the wing tip is possible.

The landing gear is admittedly of Nieuport pattern, but it has the refinements that rubber blocks are interposed between the skid and the chassis struts, and that the transverse leaf springs are fitted to the wheels in an improved manner. The military authorities, recognising this latter improvement, are, by the way, now fitting this type of spring attachment to their Nieuport monoplanes.

Access to the interior of the body is obtained through triangular doors. A dashboard, on which are fitted all the instruments necessary for cross-country flying, is arranged to fill the whole space between the planes in front of the occupants. The latter are provided with safety belts.

The rudder serves a double purpose. By being shod with iron and by being arranged to slide vertically up and down the rudder post against the action of a spring, it is made to serve as a rear skid, as well as to perform its usual function of directing the course of the machine.

Main characteristics:-

Overall length 30 ft.

Weight without complement or fuel 1,250 lbs.

Span 35 ft. 8 ins.

Speed 65 m.p.h.

Flight, November 2, 1912.

AVIATION IN PORTUGAL.

FROM some particulars which have been sent us by Mr. H. V. Roe, it is evident that Portugal is now taking aviation very seriously. Several of the prominent newspapers are collecting for the national subscription, and the shops prominently display aviation books and postcards. Out of the National Fund the Avro biplane and Maurice Farman biplane, and a Voisin hydro-aeroplane have already been bought, while some Brazilian officers have presented a Deperdussin to the Government. The Avro was officially handed over to the Minister of War on October 16th, when a crowd of about 20,000 people assembled to witness Mr. Copland Perry make some exhibition flights before the President. The flying ground is at Pedroucos, some 4 miles or so from Lisbon, between Belem and Algers, but it makes a very difficult aerodrome, as it is only about 300 yards long by 200 yards wide and is bounded on two sides by trees, on the third by some gas-holders, while the fourth is more or less open, as it adjoins one of the military rifle ranges. It is in that direction that Mr. Perry nearly always steered, and his favourite trip was up the river to Lisbon, over the town and the Avenida returning over the River Tagus, the round taking between 10 and 15 mins. The day after the machine had been handed over to the Portuguese Government Mr. Perry started off with a passenger intending to survey the country with a view to finding a permanent aerodrome. They disappeared in the direction of the town and were away for about an hour after which they continued flying in the opposite direction. Unfortunately when coming back the engine showed signs of giving up and the pilot decided, as it would be impossible to get back to the aerodrome, to bring the machine down into shallow water, about 50 yards from the shore, that being the only suitable place. Row boats were quickly to the rescue and the machine was hauled ashore little the worse for its bath. It is now called "Republica" the name being painted in red on both sides of the body and al;o in green underneath the wings, while a couple of little Republican flags are mounted on the outside struts. A good many flights have also been made by M. Trescarte on the Maurice Farman biplane. The Voisin machine is rapidly being erected, but the Deperduisin monoplane has not yet arrived, although it is expected shortly.

THE NEW AVRO BIPLANE.

EXCEPTING that the general disposition of its respective parts is the same, the new Avro biplane can hardly be recognised as a modification of the little machine on which Pixton attained his early successes and demonstrated the practicability of carrying a passenger cross-country with an engine of as low horse-power as 35.

Although it is in effect an original model to most of those who keenly follow the trend of design in this country, it is, in reality, several months old, for it was an almost identical machine that the Avro firm supplied to Mr. J. Duigan in September last. The only points of difference in the two machines are that, this present machine being a two-seater, a more powerful motor is installed, and dimensions are slightly increased throughout.

The triangular section body of the early machine has been superseded by one of rectangular section, built to an approximate streamline form, and so deep in the region of the cockpit that much head resistance and much personal discomfort of the pilot and passenger are avoided by virtue of the fact that only their heads emerge from its depths through the well-padded openings on top. Other advantages does this deep form of fuselage possess. The lower plane may be attached to it in a manner very similar to the attachment of monoplane wings; the chassis struts may be considerably shortened, thus making for more robustness in the landing gear. To facilitate transport the body may be dismantled into two sections. The crossbracing of the fuselage - it is of the ordinary girder type - is the same standard Avro system that has already been explained and illustrated in these columns.

A point worth mentioning in connection with the body is that its top surface is flat, and when the machine is in level flight is, theoretically, horizontal. To preserve its lines it is covered in by metal sheeting in the front, and by fabric to the rear.

The undercarriage needs little description, for it must be admitted that except for the central skid, and the front pair of struts fashioned from wood, and the steel disc wheels employed, it is identical with the Nieuport chassis. Rubber cushions are introduced between the struts and the central skid to further assist in deadening landing shocks.

When the machine first appeared at Brooklands there were some doubts as to whether this type of chassis would "stand up to its work" fitted to a passenger-carrying biplane. However, as far as the tests have gone it has proved eminently satisfactory. So doubts may, for the time being, be dispelled.

The main planes are rectangular, and have an aspect ratio of over 7 1/2, a feature which, coupled with the modified form of Phillips' cross-section employed, must have a most beneficial effect on their efficiency. In their bracing only eight struts are employed, these being fitted and riveted into welded steel sockets. Warping is employed for the maintenance of lateral balance.

In cross-section the planes have little curvature on the under surface, and have the peculiarity that the underside of the trailing-edge is horizontal in flight. Provisions have been made so that in quite a short space of time the machine may be turned into a monoplane. Virtually a double-purpose machine, it will be able to serve either as a weight carrier or a speedy scout. And speed it does exhibit - it must average at least 60 m.p.h.

Steel tubing is solely employed in the construction of the skeleton of the tail. This organ is purely directional, while elevation and depression is regulated by a pair of hinged flaps, operated through levers made from sheet steel.

Control is maintained by universal levers by either pilot or his passenger, the latter of whom is seated well forward in the body at the centre of gravity, so that his extra weight need not interfere with the balance of the machine.

Two little celluloid windows have been let into the floor boards in order that both will be able to see what is directly beneath them.

A 60-80 h.p. E.N.V. motor direct coupled to a 10-ft. Avro propeller provides the forward thrust.

Altogether the new Avro biplane is a decided advance on anything their works have hitherto produced. As for its efficiency it is only necessary to mention that on test on Saturday last it attained an altitude of 1,000 feet, in a little over live minutes. 2,000 feet was reached, with a heavy passenger aboard, in 13 minutes.

Flight, August 10, 1912.

THE MILITARY AEROPLANE COMPETITION - THE MACHINES.

THE AVRO BIPLANE.

THIS machine is one of the most remarkable of those flying at Salisbury, for the fact that it is the only one of the competition machines that allows the pilot and passenger to be totally enclosed and so completely protected from the rush of air. It is an interesting fact with this new Avro biplane that, with the side windows open the only wind felt is one which comes from the side when turning and banking. As will be seen by the photographs we publish this week, the fuselage completely fills the gap between the main planes. It is approximately streamline in side elevation, and its section may be represented by a tall vertical panel. The body is surprisingly narrow. Where the pilot and passenger sit it is only sufficiently wide to give them free movement. At the extreme front it is only 15 inches wide, a dimension which is obtainable by the use of a 60-h.p. vertical Green engine. The planes are identical with those fitted to the machine already supplied to the War Office. On the "all enclosed" biplane one deck is fitted to the extreme top of the fuselage, and the other to a point near the bottom. The warping wires pass from the top plane through slots in the lower, round a phosphor bronze four-grooved pulley attached to the end of the skid. It has been so arranged that a warp of eighteen inches at the wing tip is possible.

The landing gear is admittedly of Nieuport pattern, but it has the refinements that rubber blocks are interposed between the skid and the chassis struts, and that the transverse leaf springs are fitted to the wheels in an improved manner. The military authorities, recognising this latter improvement, are, by the way, now fitting this type of spring attachment to their Nieuport monoplanes.

Access to the interior of the body is obtained through triangular doors. A dashboard, on which are fitted all the instruments necessary for cross-country flying, is arranged to fill the whole space between the planes in front of the occupants. The latter are provided with safety belts.

The rudder serves a double purpose. By being shod with iron and by being arranged to slide vertically up and down the rudder post against the action of a spring, it is made to serve as a rear skid, as well as to perform its usual function of directing the course of the machine.

Main characteristics:-

Overall length 30 ft.

Weight without complement or fuel 1,250 lbs.

Span 35 ft. 8 ins.

Speed 65 m.p.h.

Flight, November 2, 1912.

AVIATION IN PORTUGAL.

FROM some particulars which have been sent us by Mr. H. V. Roe, it is evident that Portugal is now taking aviation very seriously. Several of the prominent newspapers are collecting for the national subscription, and the shops prominently display aviation books and postcards. Out of the National Fund the Avro biplane and Maurice Farman biplane, and a Voisin hydro-aeroplane have already been bought, while some Brazilian officers have presented a Deperdussin to the Government. The Avro was officially handed over to the Minister of War on October 16th, when a crowd of about 20,000 people assembled to witness Mr. Copland Perry make some exhibition flights before the President. The flying ground is at Pedroucos, some 4 miles or so from Lisbon, between Belem and Algers, but it makes a very difficult aerodrome, as it is only about 300 yards long by 200 yards wide and is bounded on two sides by trees, on the third by some gas-holders, while the fourth is more or less open, as it adjoins one of the military rifle ranges. It is in that direction that Mr. Perry nearly always steered, and his favourite trip was up the river to Lisbon, over the town and the Avenida returning over the River Tagus, the round taking between 10 and 15 mins. The day after the machine had been handed over to the Portuguese Government Mr. Perry started off with a passenger intending to survey the country with a view to finding a permanent aerodrome. They disappeared in the direction of the town and were away for about an hour after which they continued flying in the opposite direction. Unfortunately when coming back the engine showed signs of giving up and the pilot decided, as it would be impossible to get back to the aerodrome, to bring the machine down into shallow water, about 50 yards from the shore, that being the only suitable place. Row boats were quickly to the rescue and the machine was hauled ashore little the worse for its bath. It is now called "Republica" the name being painted in red on both sides of the body and al;o in green underneath the wings, while a couple of little Republican flags are mounted on the outside struts. A good many flights have also been made by M. Trescarte on the Maurice Farman biplane. The Voisin machine is rapidly being erected, but the Deperduisin monoplane has not yet arrived, although it is expected shortly.

Mr. Copland Perry's mishap on the Tagus, when the engine petered out on the Avro biplane, and he came gently to rest on the water. Making the towing hawser fast; and, on the right, towing in the machine.

Flight, April 13, 1912.

FROM THE BRITISH FLYING GROUNDS.

Brooklands Aerodrome.

<...>

A new comer during the week was the Avro monoplane, which is now in course of erection. This is a highly original machine, about which there is bound to be great divergence of opinion. The rectangular fuselage is very deep, the pilot being completely enclosed, and obtaining his view of the outside world through a number of windows covered with non-inflammable celluloid. The motor, a 50-h.p. Viale, is supported in front outside the covering. The pilot climbs in through a trap-door in the roof, and in the case of an upside down landing makes an emergency exit through the side with a pair of wire cutters.

Flight, October 2, 1912.

THE AVRO MONOPLANE.

NOT SO very many months ago we all, more or less, looked on the all-enclosed aeroplane as a dream of the future. But things move quickly in the aviation world these days, and already Messrs. A. V. Roe and Co. and Lieut. Wilfred Parke, R.N., the clever pilot who flies their machines, have shown us the practicability of this type of craft. This monoplane is entered through an aluminium trapdoor in the top of the body, for all the world as if it were a submarine that was being boarded instead of a flying machine. Inside, the pilot is comfortably seated with his elevation and warping lever between his knees, and his rudder lever at his feet. His switch, throttle, and spark advance levers are to his right hand, and his various other instruments - his altitude recorder, his compass, his revolution indicator, his watch, his map holder, and his level indicator - a very important instrument to use with this type of machine, we should think - are arranged conveniently around him. He takes his bearings, and sees what is going on around him through non-inflammable celluloid windows let into the front of the fuselage. A window sunk into the floor shows him the ground directly beneath him. Those to right and to left reveal the surroundings on either side.

When the machine first arrived at Brooklands it was generally thought - the habitats of that aerodrome invariably sit in solemn conclave on any new arrival - that, with the respiration of the pilot inside, and the fine spray of oil thrown out with the exhaust of the Viale motor, the windows would soon become clouded over, and render clear vision impossible after a few minutes' running. After his longest trip, the underneath window was the only one that showed much mistiness, and the fitting of exhaust pipes leaving the exhaust clear of the windows would undoubtedly cure the trouble, for in the Viale engine there are no auxiliary ports drilled in the cylinder walls to scatter the oil far and wide. Flying through heavy rain might make things rather difficult for the pilot, but then, as a safeguard, there is an open round hole in the body casing on each side through which he can thrust his head if necessary.

We believe there is only one other all enclosed aeroplane in existence as yet, and that is the Rumpler monoplane shown at the last Berlin Aero Exhibition. In this machine the covering for the pilot and passenger is merely a superstructure applied to an apparently standard machine. The fuselage was not especially designed for that purpose as is that of the Avro monoplane.

Two other enclosed body machines have been built, but they can scarcely come under the same category - the 100-h.p. Bleriot berline, for the pilot was accommodated outside the four-seated carriage-built body, and the Piggott monoplane, a British machine, for the fact that it has since the Aero Show of 1911 been modified, so that the pilot's head is outside the body of the machine. Thus, distinction attaches to those responsible for the monoplane under review, to the Avro firm for being the first to produce a machine of this type to prove itself successful in appreciably long flights, and to Lieut. Parke for having done the demonstration work.

The body is, as far as construction is concerned, identical with the later ones manufactured by this firm. The only difference it presents is that the ash longerons are reinforced by the application of triangular lengths of three-ply wood. This point is shown by one of our sketches. Its shape, viewed from one side, is approximately streamline, and exactly symmetrical about its longitudinal axis. In section it is rectangular. At the pilot's seat a section of the body may be represented by a vertical panel, so high that there is about 8 ins. of clearance between the top of the pilot's head and the roof of the fuselage. This measurement concerns the machine's present pilot, and would naturally vary with the overall height, in a sitting posture, of whoever may pilot a similar machine in the future. It is quite conceivable, following up this line of thought, that we shall one of these days be having our aeroplanes "made to measure."

A steel cap embraces the four longitudinal body members in front, and to this the motor - a 35-h.p. 5-cyl. radial air-cooled Viale - is bolted. Further support is provided by two stout ash bearers, which extend horizontally, one on each side, from the front of the body. At the rear end is the tail, but for this organ no description is necessary, for in construction and arrangement it is similar to those we have described in the past in connection with other Avro productions. One point, though, is noticeable - that the tail-skid is sprung in a manner that saves space and reduces the overall height of that section of the machine.

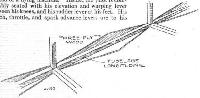

The landing gear, as in the case of the later Avro biplanes is a version of the Nieuport idea. The central skid supports the body through steel struts arranged V fashion - the front ones oval and the rear ones round in section. In both cases they slant forward to take the "drift" of landing. The laminated axle of spring steel is clipped to the skid. For the wings, except that the front spar of I section is built up instead of being hollowed out from the solid, the only point of more than usual originality is the manner in which the rear spars, in warping rock together with the single strut forming the upper and lower cabane, as one unit. This, perhaps, can better be conveyed by the accompanying sketch. The way of operating the warping that this same sketch shows is also highly interesting. Quite a sound point in connection with the engine controls - the main wing and tail controls are, as can be seen, standard Avro - is that they are mounted, the switch, the throttle, and the spark advance lever in a line together. Further, the levers operate in the same direction - that is, both spark and throttle levers are pushed forward to increase engine speed. The advantages of this system as against fitting the levers unsystematically, is too apparent to need dwelling on here.

FROM THE BRITISH FLYING GROUNDS.

Brooklands Aerodrome.

<...>

A new comer during the week was the Avro monoplane, which is now in course of erection. This is a highly original machine, about which there is bound to be great divergence of opinion. The rectangular fuselage is very deep, the pilot being completely enclosed, and obtaining his view of the outside world through a number of windows covered with non-inflammable celluloid. The motor, a 50-h.p. Viale, is supported in front outside the covering. The pilot climbs in through a trap-door in the roof, and in the case of an upside down landing makes an emergency exit through the side with a pair of wire cutters.

Flight, October 2, 1912.

THE AVRO MONOPLANE.

NOT SO very many months ago we all, more or less, looked on the all-enclosed aeroplane as a dream of the future. But things move quickly in the aviation world these days, and already Messrs. A. V. Roe and Co. and Lieut. Wilfred Parke, R.N., the clever pilot who flies their machines, have shown us the practicability of this type of craft. This monoplane is entered through an aluminium trapdoor in the top of the body, for all the world as if it were a submarine that was being boarded instead of a flying machine. Inside, the pilot is comfortably seated with his elevation and warping lever between his knees, and his rudder lever at his feet. His switch, throttle, and spark advance levers are to his right hand, and his various other instruments - his altitude recorder, his compass, his revolution indicator, his watch, his map holder, and his level indicator - a very important instrument to use with this type of machine, we should think - are arranged conveniently around him. He takes his bearings, and sees what is going on around him through non-inflammable celluloid windows let into the front of the fuselage. A window sunk into the floor shows him the ground directly beneath him. Those to right and to left reveal the surroundings on either side.

When the machine first arrived at Brooklands it was generally thought - the habitats of that aerodrome invariably sit in solemn conclave on any new arrival - that, with the respiration of the pilot inside, and the fine spray of oil thrown out with the exhaust of the Viale motor, the windows would soon become clouded over, and render clear vision impossible after a few minutes' running. After his longest trip, the underneath window was the only one that showed much mistiness, and the fitting of exhaust pipes leaving the exhaust clear of the windows would undoubtedly cure the trouble, for in the Viale engine there are no auxiliary ports drilled in the cylinder walls to scatter the oil far and wide. Flying through heavy rain might make things rather difficult for the pilot, but then, as a safeguard, there is an open round hole in the body casing on each side through which he can thrust his head if necessary.

We believe there is only one other all enclosed aeroplane in existence as yet, and that is the Rumpler monoplane shown at the last Berlin Aero Exhibition. In this machine the covering for the pilot and passenger is merely a superstructure applied to an apparently standard machine. The fuselage was not especially designed for that purpose as is that of the Avro monoplane.

Two other enclosed body machines have been built, but they can scarcely come under the same category - the 100-h.p. Bleriot berline, for the pilot was accommodated outside the four-seated carriage-built body, and the Piggott monoplane, a British machine, for the fact that it has since the Aero Show of 1911 been modified, so that the pilot's head is outside the body of the machine. Thus, distinction attaches to those responsible for the monoplane under review, to the Avro firm for being the first to produce a machine of this type to prove itself successful in appreciably long flights, and to Lieut. Parke for having done the demonstration work.

The body is, as far as construction is concerned, identical with the later ones manufactured by this firm. The only difference it presents is that the ash longerons are reinforced by the application of triangular lengths of three-ply wood. This point is shown by one of our sketches. Its shape, viewed from one side, is approximately streamline, and exactly symmetrical about its longitudinal axis. In section it is rectangular. At the pilot's seat a section of the body may be represented by a vertical panel, so high that there is about 8 ins. of clearance between the top of the pilot's head and the roof of the fuselage. This measurement concerns the machine's present pilot, and would naturally vary with the overall height, in a sitting posture, of whoever may pilot a similar machine in the future. It is quite conceivable, following up this line of thought, that we shall one of these days be having our aeroplanes "made to measure."

A steel cap embraces the four longitudinal body members in front, and to this the motor - a 35-h.p. 5-cyl. radial air-cooled Viale - is bolted. Further support is provided by two stout ash bearers, which extend horizontally, one on each side, from the front of the body. At the rear end is the tail, but for this organ no description is necessary, for in construction and arrangement it is similar to those we have described in the past in connection with other Avro productions. One point, though, is noticeable - that the tail-skid is sprung in a manner that saves space and reduces the overall height of that section of the machine.

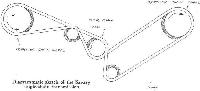

The landing gear, as in the case of the later Avro biplanes is a version of the Nieuport idea. The central skid supports the body through steel struts arranged V fashion - the front ones oval and the rear ones round in section. In both cases they slant forward to take the "drift" of landing. The laminated axle of spring steel is clipped to the skid. For the wings, except that the front spar of I section is built up instead of being hollowed out from the solid, the only point of more than usual originality is the manner in which the rear spars, in warping rock together with the single strut forming the upper and lower cabane, as one unit. This, perhaps, can better be conveyed by the accompanying sketch. The way of operating the warping that this same sketch shows is also highly interesting. Quite a sound point in connection with the engine controls - the main wing and tail controls are, as can be seen, standard Avro - is that they are mounted, the switch, the throttle, and the spark advance lever in a line together. Further, the levers operate in the same direction - that is, both spark and throttle levers are pushed forward to increase engine speed. The advantages of this system as against fitting the levers unsystematically, is too apparent to need dwelling on here.

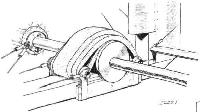

THE AVRO MONOPLANE. - Detailed view of the landing gear, engine mounting, and the non-inflammable celluloid windows through which the pilot sees what is going on around him.

THE NEW AVRO MILITARY PATTERN ENCLOSED-TYPE MACHINE. - View of the chassis and front part of the fuselage.

AN IMPRESSION OF SPEED. - A genuine photograph of the new enclosed Avro monoplane, which was recently flying at Brooklands, secured by FLIGHT photographer in one-thousandth part of a second.

Showing how the fuselage longerons are strengthened by the application of three-ply wood on the Avro monoplane.

Details of the Avro Skid Attachment. - A rubber insert is arranged between the skid and the tubular steel struts supporting it.

DETAILS OF THE CONTROL OF THE AVRO MONOPLANE. - The whole of the rear wing spars, together with the upper and lower cabane strut, rocks in a single unit.

Flight, August 10, 1912.

THE MILITARY AEROPLANE COMPETITION - THE MACHINES.

THE AVRO BIPLANE.

THIS machine is one of the most remarkable of those flying at Salisbury, for the fact that it is the only one of the competition machines that allows the pilot and passenger to be totally enclosed and so completely protected from the rush of air. It is an interesting fact with this new Avro biplane that, with the side windows open the only wind felt is one which comes from the side when turning and banking. As will be seen by the photographs we publish this week, the fuselage completely fills the gap between the main planes. It is approximately streamline in side elevation, and its section may be represented by a tall vertical panel. The body is surprisingly narrow. Where the pilot and passenger sit it is only sufficiently wide to give them free movement. At the extreme front it is only 15 inches wide, a dimension which is obtainable by the use of a 60-h.p. vertical Green engine. The planes are identical with those fitted to the machine already supplied to the War Office. On the "all enclosed" biplane one deck is fitted to the extreme top of the fuselage, and the other to a point near the bottom. The warping wires pass from the top plane through slots in the lower, round a phosphor bronze four-grooved pulley attached to the end of the skid. It has been so arranged that a warp of eighteen inches at the wing tip is possible.

The landing gear is admittedly of Nieuport pattern, but it has the refinements that rubber blocks are interposed between the skid and the chassis struts, and that the transverse leaf springs are fitted to the wheels in an improved manner. The military authorities, recognising this latter improvement, are, by the way, now fitting this type of spring attachment to their Nieuport monoplanes.

Access to the interior of the body is obtained through triangular doors. A dashboard, on which are fitted all the instruments necessary for cross-country flying, is arranged to fill the whole space between the planes in front of the occupants. The latter are provided with safety belts.

The rudder serves a double purpose. By being shod with iron and by being arranged to slide vertically up and down the rudder post against the action of a spring, it is made to serve as a rear skid, as well as to perform its usual function of directing the course of the machine.

Main characteristics:-

Overall length 30 ft.

Weight without complement or fuel 1,250 lbs.

Span 35 ft. 8 ins.

Speed 65 m.p.h.

Flight, August 31, 1912.

PARKE'S DIVE.