Книги

Putnam

P.Hare

Royal Aircraft Factory

193

P.Hare - Royal Aircraft Factory /Putnam/

The Balloon Factory's work continued as best it could during the upheaval of moving and, in June 1904, extensive tests were conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of a new system of man-lifting kites which had been developed by an expatriate American showman named Samuel Franklin Cody. This system used a number of biplane box kites, flown on a common cable with a smaller pilot kite to steady the line, and a huge carrier kite, equipped with a balloon basket or bosun's chair, which could ascend the cable under the control of its occupant.

Cody's kite system proved far superior to anything previously tried, and observers were lifted to altitudes greater than 1,000ft on several occasions during the trials, without the dangerous instability in gusty conditions which had marred previous systems. Because the kites became effective at similar wind velocities to those at which balloons became unstable, the system was recommended for adoption by the British Army. Cody, who was a Texan by birth, and who had variously been a cowboy, a prospector, a horse-dealer, a showman, an actor and a playwright, was engaged to instruct Balloon School personnel in their operation. He was initially engaged for three months only, but his contract was repeatedly renewed until, finally, in April 1906, he was appointed 'Chief Kite Instructor' at a salary and status approximately equivalent to that of a British Army colonel.

In the autumn of 1904 Col Capper, accompanied by his wife, Edith, visited the St Louis World's Fair, which was held to celebrate the centenary of the 'Louisiana Purchase' which had brought the region within the United States of America. He went as the representative of the War Office, intending to study the many aeronautical exhibits on display, but found these to be something of a disappointment, as did the organisers. His long journey was far from wasted, however, as he made calls upon a number of individuals who had made significant contributions to aviation. These included Octave Chanute, the author of Progress in Flying Machines; Professor Samuel Pierpont Langley of the Smithsonian Institution; and the Wright brothers, who had already made the first powered aeroplane flights. As a result of the last of these visits, which was made entirely upon his own initiative, Capper included in his report to the War Office a recommendation that Britain should seek to purchase an aeroplane from the Wrights. This recommendation was accepted, and negotiations were duly opened by a sporadic exchange of correspondence, but initially the Wrights did not regard their aeroplane as being sufficiently developed to be sold. Later negotiations were to become bogged down in bureaucracy and hampered by misunderstanding and un-seized opportunities on both sides. Finally, Capper, for reasons which will become apparent, came to believe that British interests would be better served by the development of an indigenous aeroplane, specifically designed to fulfil the requirements of military scouting.

During the summer of 1905, while Col Templer's attention was still largely focussed upon the move to Farnborough and the construction of the airship hangar, S F Cody, whose restless mind was always seeking a new challenge and who was already working towards manned flight, designed a biplane 'glider-kite' which had a wingspan of over fifty feet and an empty weight of only 116lb. This was built at the new Farnborough factory and was tested, with the assistance of personnel from the Balloon Sections, by flying it up to the desired altitude - usually around 100ft - in the normal kite manner, and then releasing it to return to earth as a glider, its pilot occupying a prone position on the lower wing. This craft, which had numerous triangular fin surfaces above the upper wing and below the lower wing, was equipped with small winglet ailerons for lateral control, one of the earliest recorded uses of this form of control. The inclusion of these ailerons, together with the adoption of the prone pilot position introduced by the Wrights, demonstrated Cody's awareness of general aeronautical development and his willingness to learn from others.

Numerous glides were made across the clear expanse of Farnborough Common, including several in which the craft travelled in excess of 700ft. The trials ended when a sudden gust of wind caused a sideslip and the pilot, Cody's younger son, Vivian, was badly injured in the resulting crash, although he eventually made a complete recovery and continued to work at Farnborough until his retirement in the 1950s. The glider was not repaired, most probably because it was felt that the experiment had by then served its purpose. Cody was already planning another experiment.

Cody's kite system proved far superior to anything previously tried, and observers were lifted to altitudes greater than 1,000ft on several occasions during the trials, without the dangerous instability in gusty conditions which had marred previous systems. Because the kites became effective at similar wind velocities to those at which balloons became unstable, the system was recommended for adoption by the British Army. Cody, who was a Texan by birth, and who had variously been a cowboy, a prospector, a horse-dealer, a showman, an actor and a playwright, was engaged to instruct Balloon School personnel in their operation. He was initially engaged for three months only, but his contract was repeatedly renewed until, finally, in April 1906, he was appointed 'Chief Kite Instructor' at a salary and status approximately equivalent to that of a British Army colonel.

In the autumn of 1904 Col Capper, accompanied by his wife, Edith, visited the St Louis World's Fair, which was held to celebrate the centenary of the 'Louisiana Purchase' which had brought the region within the United States of America. He went as the representative of the War Office, intending to study the many aeronautical exhibits on display, but found these to be something of a disappointment, as did the organisers. His long journey was far from wasted, however, as he made calls upon a number of individuals who had made significant contributions to aviation. These included Octave Chanute, the author of Progress in Flying Machines; Professor Samuel Pierpont Langley of the Smithsonian Institution; and the Wright brothers, who had already made the first powered aeroplane flights. As a result of the last of these visits, which was made entirely upon his own initiative, Capper included in his report to the War Office a recommendation that Britain should seek to purchase an aeroplane from the Wrights. This recommendation was accepted, and negotiations were duly opened by a sporadic exchange of correspondence, but initially the Wrights did not regard their aeroplane as being sufficiently developed to be sold. Later negotiations were to become bogged down in bureaucracy and hampered by misunderstanding and un-seized opportunities on both sides. Finally, Capper, for reasons which will become apparent, came to believe that British interests would be better served by the development of an indigenous aeroplane, specifically designed to fulfil the requirements of military scouting.

During the summer of 1905, while Col Templer's attention was still largely focussed upon the move to Farnborough and the construction of the airship hangar, S F Cody, whose restless mind was always seeking a new challenge and who was already working towards manned flight, designed a biplane 'glider-kite' which had a wingspan of over fifty feet and an empty weight of only 116lb. This was built at the new Farnborough factory and was tested, with the assistance of personnel from the Balloon Sections, by flying it up to the desired altitude - usually around 100ft - in the normal kite manner, and then releasing it to return to earth as a glider, its pilot occupying a prone position on the lower wing. This craft, which had numerous triangular fin surfaces above the upper wing and below the lower wing, was equipped with small winglet ailerons for lateral control, one of the earliest recorded uses of this form of control. The inclusion of these ailerons, together with the adoption of the prone pilot position introduced by the Wrights, demonstrated Cody's awareness of general aeronautical development and his willingness to learn from others.

Numerous glides were made across the clear expanse of Farnborough Common, including several in which the craft travelled in excess of 700ft. The trials ended when a sudden gust of wind caused a sideslip and the pilot, Cody's younger son, Vivian, was badly injured in the resulting crash, although he eventually made a complete recovery and continued to work at Farnborough until his retirement in the 1950s. The glider was not repaired, most probably because it was felt that the experiment had by then served its purpose. Cody was already planning another experiment.

S F Cody, assisted by his sons (also wearing sombreros), launches a string of man-lifting kites some time before their adoption by the Army.

S F Cody, meanwhile, following his period of involvement with the airship Nulli Secundus, had been away demonstrating his man-lifting kites to the Royal Navy, in the unfulfilled hope that they, too, would decide to purchase his system. He returned to Farnborough on 6 September 1908 to supervise completion of the machine which had been officially titled British Army Aeroplane No 1, but which showed the unmistakable hand of Cody in its design. The construction of this aeroplane had been proceeding sporadically since the previous November, in whatever time Cody had been able to spare from his numerous other duties. Now, perhaps spurred on by the purchase of a replacement 50hp Antoinette engine, and by a desire to beat Dunne, work on the aeroplane progressed rapidly, and by the 19 September it was sufficiently complete to be taken out for engine tests. Taxying trials, made two days later in a clearing near the Factory, revealed that the machine was nose heavy, but ended suddenly when a wingtip struck a post and was slightly damaged. This was soon repaired, and ground trials recommenced on the 24th, this time on Laffan's Plain where there was far more space, although the surface was poorer.

At one point, during further taxying trials on 30 September, Cody became aware of a brief pause in the vibration, and a subsequent examination of the machine's wheel tracks revealed that it had left the ground for a short distance. Although Cody dismissed this as 'only a jump', it was a genuine take-off and a positive step towards powered flight. Unfortunately further tests had to be postponed, as Cody was required to return to Portsmouth to conclude his kiting demonstrations for the Royal Navy. He returned to Farnborough in time to resume trials with the aeroplane on 14 October, some modifications intended to reduce drag and improve the pilots' view having been carried out during his absence. On this occasion two more short hops were made, each of about fifty yards, at a height of eight to ten feet.

On 16 October British Army Aeroplane No 1 was taken out again, and, while taxying at speed in order to climb a slope, Cody made yet another 'jump' of some seventy-five yards. Then, starting near to the south-eastern corner of Farnborough Common, close to the Swan Inn plateau, Cody set off towards the north-west and, after a ground run of some sixty yards, took off and flew at a height of approximately thirty feet until he was forced to turn to avoid a clump of trees. During this manoeuvre the tip of the port wing made contact with the ground and the flight ended in a crash, with considerable damage to the port wings. Fortunately, Cody was completely unhurt.

This flight, now officially recognised as the first sustained and controlled powered aeroplane flight in Great Britain, covered more than a quarter of a mile and lasted twenty-seven seconds (an airspeed of 35mph).

The next day's edition of The Times carried a full account of the flight under the headline 'The Army Aeroplane - Accident at Farnborough', and totally ignored the real significance of the event. Thus were Cody and the Balloon Factory deprived of the public recognition their joint achievement deserved.

Capper's report to Whitehall, written on the day of the flight, was equally unenthusiastic, concentrating upon the accident and the resultant damage rather than upon the significance of the flight itself. It ended with the words, 'I do not propose to abandon trials of this machine'. Perhaps Capper was a little disappointed that his protege, Lt Dunne, had not been the first to fly. Whatever his reasons for this unnecessarily negative attitude, Capper's report, coupled with his suggestion that more space was required for aeroplane experiments than existed at Farnborough, was the first step towards a conclusion which must have been the last thing he wanted.

British Army Aeroplane No 1 was repaired, a number of small modifications being incorporated at the same time, and flight trials resumed in January 1909, this time on the slightly less restricted ground of nearby Laffan's Plain. These trials included the attachment of numerous streamers to various points on the machine's surfaces to show the airflow.

Cody, an accomplished horseman, quickly developed his piloting skills, making numerous flights, often close to the ground, to explore the machine's control responses. Dunne, meanwhile, continued his experiments, still confident that his was the superior design and that he, too, would achieve true powered flight and eventually overtake his rival.

Then came a setback.

<...>

At one point, during further taxying trials on 30 September, Cody became aware of a brief pause in the vibration, and a subsequent examination of the machine's wheel tracks revealed that it had left the ground for a short distance. Although Cody dismissed this as 'only a jump', it was a genuine take-off and a positive step towards powered flight. Unfortunately further tests had to be postponed, as Cody was required to return to Portsmouth to conclude his kiting demonstrations for the Royal Navy. He returned to Farnborough in time to resume trials with the aeroplane on 14 October, some modifications intended to reduce drag and improve the pilots' view having been carried out during his absence. On this occasion two more short hops were made, each of about fifty yards, at a height of eight to ten feet.

On 16 October British Army Aeroplane No 1 was taken out again, and, while taxying at speed in order to climb a slope, Cody made yet another 'jump' of some seventy-five yards. Then, starting near to the south-eastern corner of Farnborough Common, close to the Swan Inn plateau, Cody set off towards the north-west and, after a ground run of some sixty yards, took off and flew at a height of approximately thirty feet until he was forced to turn to avoid a clump of trees. During this manoeuvre the tip of the port wing made contact with the ground and the flight ended in a crash, with considerable damage to the port wings. Fortunately, Cody was completely unhurt.

This flight, now officially recognised as the first sustained and controlled powered aeroplane flight in Great Britain, covered more than a quarter of a mile and lasted twenty-seven seconds (an airspeed of 35mph).

The next day's edition of The Times carried a full account of the flight under the headline 'The Army Aeroplane - Accident at Farnborough', and totally ignored the real significance of the event. Thus were Cody and the Balloon Factory deprived of the public recognition their joint achievement deserved.

Capper's report to Whitehall, written on the day of the flight, was equally unenthusiastic, concentrating upon the accident and the resultant damage rather than upon the significance of the flight itself. It ended with the words, 'I do not propose to abandon trials of this machine'. Perhaps Capper was a little disappointed that his protege, Lt Dunne, had not been the first to fly. Whatever his reasons for this unnecessarily negative attitude, Capper's report, coupled with his suggestion that more space was required for aeroplane experiments than existed at Farnborough, was the first step towards a conclusion which must have been the last thing he wanted.

British Army Aeroplane No 1 was repaired, a number of small modifications being incorporated at the same time, and flight trials resumed in January 1909, this time on the slightly less restricted ground of nearby Laffan's Plain. These trials included the attachment of numerous streamers to various points on the machine's surfaces to show the airflow.

Cody, an accomplished horseman, quickly developed his piloting skills, making numerous flights, often close to the ground, to explore the machine's control responses. Dunne, meanwhile, continued his experiments, still confident that his was the superior design and that he, too, would achieve true powered flight and eventually overtake his rival.

Then came a setback.

<...>

Samuel Cody makes the first powered, sustained and controlled flight in Great Britain, in British Army Aeroplane No I, on October 1908.

British Army Aeroplane No 1 emerges from the Airship Shed on 20 January 1909, after rebuilding. The streamers are to show the path of the airflow over the machine. Note the folding tailbooms, designed to facilitate storage.

Sewing the fabric covering on to the mainplanes of British Army Aeroplane No 1 inside the original airship shed, with S F Cody keeping a watchful eye on the workmanship.

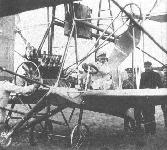

S F Cody at the controls of British Army Aeroplane No 1. The photograph was taken in September or early October 1908, and was almost certainly posed for the benefit of the press, as one wheel is still without a tyre. Note the crossed chain drive to the propeller on the port side.

S F Cody's victorious Military Trials machine outside his shed on Laffan's Plain. The greater modernity of contemporary Farnborough designs such as the B.E.2 is all too obvious.

F.E.1

With ?1,000 financial backing obtained from his grandfather in anticipation of a legacy, Geoffrey de Havilland gave up regular employment and built two successive aeroplanes of his own design. The first broke up on take-off, fortunately without injury to its creator, but the second was a success, and first flew on 10 September 1910, piloted by de Havilland. This was also his first flight.

A conventional Farman-type pusher biplane with a forward elevator, it was powered by a 45hp horizontally-opposed four-cylinder engine which had also been designed by de Havilland and was built for him by the Iris Motor Company of Willesden, north-west London.

De Havilland used the machine to teach himself to fly and then, having almost exhausted the ?1,000, he was appointed designer/test pilot at the Balloon Factory. At the same time he sold his aeroplane to the War Office for ?400, subject to its passing acceptance trials which principally consisted of demonstrating its ability to fly for one hour without adjustment or repair. This de Havilland achieved on 14 January 1911, although, owing to the freezing weather, he was allowed to land twice during the test to thaw out.

As Government property the aeroplane became known as the Farman Experimental or F.E.I. It was the first aeroplane to be classified in accordance with the Factory's system, and was the subject of continual development. First it was cleaned up aerodynamically, which included being fitted with new struts of improved streamline form. By the end of March its tailplane and rear elevator had been replaced by units of increased area, and by 11 April wing extensions had been fitted, enabling de Havilland to take up a number of passengers over the next few days. The extensions were removed early the following month because they were found to have an adverse effect on lateral control, but they were refitted by the end of the month, together with larger rudders, the Factory having realised that the existing rudders were not sufficiently powerful to overcome the drag of the ailerons when the extensions were fitted. By June 12 the tailplane incidence had been increased so that it would produce additional lift, thereby taking all load off the forward elevator. The subsequent tests obviously proved satisfactory, as the F.E.I was flown on 3 July with the front elevator removed. As usual the pilot was Geoffrey de Havilland, who reported that the fore-and-aft trim was not satisfactory. This problem was remedied overnight by re-rigging the wings to alter the position of the centre of pressure relative to the centre of gravity, and the machine was flown on numerous occasions throughout the month without further modifications. On 27 July de Havilland reached an altitude of 920ft, and the following day he gave short passenger flights to eighteen officers and men of the London Balloon Company Territorials, covering about eighty miles in the process.

Lt Theodore Ridge, the Factory's Assistant Superintendent, began to learn to fly on this machine in late July and early August, but on Tuesday 15 August he crashed while landing, damaging the engine, its mountings, the undercarriage and one lower wing.

There is no record of the aeroplane flying again, and officially it was 'reconstructed' as the F.E.2. However, as the latter was actually a totally new aeroplane and was already completed at the time of Ridge's crash, it is most probable that the F.E.I was broken up for spares.

Powerplant: 45hp four-cylinder Iris-built de Havilland engine

Dimensions:

span 33ft 0in

wing area 340sq ft;

length 40ft 0in;

Weight: 1,100lb (loaded).

Performance:

max speed 37mph at sea level;

endurance 1hr 20min.

With ?1,000 financial backing obtained from his grandfather in anticipation of a legacy, Geoffrey de Havilland gave up regular employment and built two successive aeroplanes of his own design. The first broke up on take-off, fortunately without injury to its creator, but the second was a success, and first flew on 10 September 1910, piloted by de Havilland. This was also his first flight.

A conventional Farman-type pusher biplane with a forward elevator, it was powered by a 45hp horizontally-opposed four-cylinder engine which had also been designed by de Havilland and was built for him by the Iris Motor Company of Willesden, north-west London.

De Havilland used the machine to teach himself to fly and then, having almost exhausted the ?1,000, he was appointed designer/test pilot at the Balloon Factory. At the same time he sold his aeroplane to the War Office for ?400, subject to its passing acceptance trials which principally consisted of demonstrating its ability to fly for one hour without adjustment or repair. This de Havilland achieved on 14 January 1911, although, owing to the freezing weather, he was allowed to land twice during the test to thaw out.

As Government property the aeroplane became known as the Farman Experimental or F.E.I. It was the first aeroplane to be classified in accordance with the Factory's system, and was the subject of continual development. First it was cleaned up aerodynamically, which included being fitted with new struts of improved streamline form. By the end of March its tailplane and rear elevator had been replaced by units of increased area, and by 11 April wing extensions had been fitted, enabling de Havilland to take up a number of passengers over the next few days. The extensions were removed early the following month because they were found to have an adverse effect on lateral control, but they were refitted by the end of the month, together with larger rudders, the Factory having realised that the existing rudders were not sufficiently powerful to overcome the drag of the ailerons when the extensions were fitted. By June 12 the tailplane incidence had been increased so that it would produce additional lift, thereby taking all load off the forward elevator. The subsequent tests obviously proved satisfactory, as the F.E.I was flown on 3 July with the front elevator removed. As usual the pilot was Geoffrey de Havilland, who reported that the fore-and-aft trim was not satisfactory. This problem was remedied overnight by re-rigging the wings to alter the position of the centre of pressure relative to the centre of gravity, and the machine was flown on numerous occasions throughout the month without further modifications. On 27 July de Havilland reached an altitude of 920ft, and the following day he gave short passenger flights to eighteen officers and men of the London Balloon Company Territorials, covering about eighty miles in the process.

Lt Theodore Ridge, the Factory's Assistant Superintendent, began to learn to fly on this machine in late July and early August, but on Tuesday 15 August he crashed while landing, damaging the engine, its mountings, the undercarriage and one lower wing.

There is no record of the aeroplane flying again, and officially it was 'reconstructed' as the F.E.2. However, as the latter was actually a totally new aeroplane and was already completed at the time of Ridge's crash, it is most probable that the F.E.I was broken up for spares.

Powerplant: 45hp four-cylinder Iris-built de Havilland engine

Dimensions:

span 33ft 0in

wing area 340sq ft;

length 40ft 0in;

Weight: 1,100lb (loaded).

Performance:

max speed 37mph at sea level;

endurance 1hr 20min.

De Havilland No.2 was flown in 1910 and was purchased by the War Office and used for development work at Farnborough identified as FE 1.

Another project carried out early in 1907, in parallel with Cody's work, was the construction of a full-sized aeroplane in accordance with the ideas developed by Lt Dunne as a result of his extensive experiments. This craft, designated simply D l , was initially to be tested as a glider before fitting the propulsion system which had been designed for it by Capt Carden.

By arrangement with the Marquis of Tullibardine, eldest son of the Duke of Atholl, the flight tests took place, in secret, at a remote location near Blair Atholl, on his family estate in the Grampian highlands, during the summer of 1907. This desire for secrecy, especially when compared with the Factory's normal habit of operating from a public common, clearly illustrates the significance attached to Dunne's 'discovery'. Since Cody's work was an extension of his already well-known kite experiments, any attempt at secrecy would have been futile, and none was made. It was also entirely possible that Capper hoped to focus all attention on Cody, thereby allowing Dunne to work without distraction.

A number of successful glides were made, the craft being piloted by various officers from the Balloon School, as Dunne's frail health was not considered up to the task. A minor crash occurred while Capper was at the controls, during a brief visit to judge what progress was being made. The glider made contact with a wall, and flight trials were stopped pending repairs. During the course of this work the glider was converted into a powered aeroplane, the D1-B (the glider thus becoming, retrospectively, the D1-A). The propulsion system comprised twin propellers mounted on outriggers and driven, via belts or chains, by two 12hp Buchet engines, one of which had previously powered Cody's power kite. The two engines were coupled to a single shaft, and some initial difficulties were resolved when it was discovered that they had been installed so as to run in opposite directions.

It was intended that the powered aeroplane would be launched from a wheeled trolley running along a raised pathway of planks, laid to provide a reasonably level surface. Unfortunately the trolley ran off the planks during the first take-off attempt, and the machine was damaged to an extent which almost certainly would have required its return to Farnborough. It was felt that this would make it impossible to resume flight trials before the onset of winter, so the experiments were abandoned until the following year. The team's enthusiasm does not appear to have been diminished by this setback, and Capper seems to have had little trouble in convincing the War Office that they should be allowed to continue with the project.

<...>

By early September Lt Dunne had returned to Blair Atholl. He was accompanied by a team of helpers which included Lt Westlake, who had been a member of the previous year's party, and a young militia lieutenant, Lancelot Gibbs, who was to act as pilot. They took with them a new glider, the D3, trials of which were intended to provide information required to complete the powered machine, D4, which was under construction at Farnborough.

The glider proved quite promising at first, with a good number of short flights being made by Lt Gibbs on the very first day of the trials. However, later efforts were less successful, being hampered by the roughness of the terrain and the turbulence of the wind. As a consequence, the party appears to have spent a considerable amount of time roaming over a wide area, seeking a location which offered more favourable operating conditions, but without success.

At the end of the month Dunne left Gibbs in charge of the group testing the glider in the hills while he, together with a few assistants, returned to Blair Atholl itself to begin erecting the powered D4, which had by then arrived from Farnborough. This operation appears to have been extremely difficult, especially at a distance of some 500 miles from the Balloon Factory's workshops. Problems with warped timber and inadequate tools delayed completion of the aeroplane until the middle of November 1908, by which time Capt Carden had come up to supervise the installation of the engine and to take charge of the testing.

Flight trials started on 15 November, with Gibbs at the controls, but difficulties with the undercarriage caused an immediate halt. Ground runs, interspersed with engine malfunctions, occupied the remainder of the month, and the first take-off, covering a distance of about thirty feet, did not occur until 4 December. Two days later Carden had to return to Farnborough, and the tests continued in his absence, more short hops being achieved despite the lack of his skills with the engine. On 10 December Gibbs managed a flight of 120 feet, and on this note of minor triumph the trials were ended.

In common with many of its contemporaries, the Dunne D4 appears to have been rather underpowered, especially in view of its very heavy undercarriage, and the final acceptance of this shortcoming may well have been the reason for the seemingly premature ending of the tests. Alternatively, it is equally possible that the Dunne party was defeated by the weather, for winters in the Scottish highlands can be very severe. In any event, the test flights of the D3 and D4 seemed to uphold Dunne's theories regarding stability, even if his designs of aeroplanes and their control systems needed further development.

By arrangement with the Marquis of Tullibardine, eldest son of the Duke of Atholl, the flight tests took place, in secret, at a remote location near Blair Atholl, on his family estate in the Grampian highlands, during the summer of 1907. This desire for secrecy, especially when compared with the Factory's normal habit of operating from a public common, clearly illustrates the significance attached to Dunne's 'discovery'. Since Cody's work was an extension of his already well-known kite experiments, any attempt at secrecy would have been futile, and none was made. It was also entirely possible that Capper hoped to focus all attention on Cody, thereby allowing Dunne to work without distraction.

A number of successful glides were made, the craft being piloted by various officers from the Balloon School, as Dunne's frail health was not considered up to the task. A minor crash occurred while Capper was at the controls, during a brief visit to judge what progress was being made. The glider made contact with a wall, and flight trials were stopped pending repairs. During the course of this work the glider was converted into a powered aeroplane, the D1-B (the glider thus becoming, retrospectively, the D1-A). The propulsion system comprised twin propellers mounted on outriggers and driven, via belts or chains, by two 12hp Buchet engines, one of which had previously powered Cody's power kite. The two engines were coupled to a single shaft, and some initial difficulties were resolved when it was discovered that they had been installed so as to run in opposite directions.

It was intended that the powered aeroplane would be launched from a wheeled trolley running along a raised pathway of planks, laid to provide a reasonably level surface. Unfortunately the trolley ran off the planks during the first take-off attempt, and the machine was damaged to an extent which almost certainly would have required its return to Farnborough. It was felt that this would make it impossible to resume flight trials before the onset of winter, so the experiments were abandoned until the following year. The team's enthusiasm does not appear to have been diminished by this setback, and Capper seems to have had little trouble in convincing the War Office that they should be allowed to continue with the project.

<...>

By early September Lt Dunne had returned to Blair Atholl. He was accompanied by a team of helpers which included Lt Westlake, who had been a member of the previous year's party, and a young militia lieutenant, Lancelot Gibbs, who was to act as pilot. They took with them a new glider, the D3, trials of which were intended to provide information required to complete the powered machine, D4, which was under construction at Farnborough.

The glider proved quite promising at first, with a good number of short flights being made by Lt Gibbs on the very first day of the trials. However, later efforts were less successful, being hampered by the roughness of the terrain and the turbulence of the wind. As a consequence, the party appears to have spent a considerable amount of time roaming over a wide area, seeking a location which offered more favourable operating conditions, but without success.

At the end of the month Dunne left Gibbs in charge of the group testing the glider in the hills while he, together with a few assistants, returned to Blair Atholl itself to begin erecting the powered D4, which had by then arrived from Farnborough. This operation appears to have been extremely difficult, especially at a distance of some 500 miles from the Balloon Factory's workshops. Problems with warped timber and inadequate tools delayed completion of the aeroplane until the middle of November 1908, by which time Capt Carden had come up to supervise the installation of the engine and to take charge of the testing.

Flight trials started on 15 November, with Gibbs at the controls, but difficulties with the undercarriage caused an immediate halt. Ground runs, interspersed with engine malfunctions, occupied the remainder of the month, and the first take-off, covering a distance of about thirty feet, did not occur until 4 December. Two days later Carden had to return to Farnborough, and the tests continued in his absence, more short hops being achieved despite the lack of his skills with the engine. On 10 December Gibbs managed a flight of 120 feet, and on this note of minor triumph the trials were ended.

In common with many of its contemporaries, the Dunne D4 appears to have been rather underpowered, especially in view of its very heavy undercarriage, and the final acceptance of this shortcoming may well have been the reason for the seemingly premature ending of the tests. Alternatively, it is equally possible that the Dunne party was defeated by the weather, for winters in the Scottish highlands can be very severe. In any event, the test flights of the D3 and D4 seemed to uphold Dunne's theories regarding stability, even if his designs of aeroplanes and their control systems needed further development.

The colossal Handley Page V/1500 bomber. Royal Aircraft Factory research established that the rear propellers in such tandem engine arrangements could never achieve more than ninety per cent of their usual efficiency owing to interference from the slipstream of the tractor propellers.

B.E.1

The third machine in the Factory's initial research series, each of which was of a distinct and separate type, was a tractor biplane. It was named the Bleriot Experimental Number 1, or B.E.1. As with other contemporary Farnborough designs, it was ostensibly a reconstruction of another aeroplane, in this case a Voisin which had originally been presented to the War Office by the Duke of Westminster and which, following a crash, had been delivered to the Factory for repair in June 1911. The War Office granted permission for the alterations and additions which O'Gorman had suggested on 12 August 1911, but it is probable that design work, most of which was carried out by Geoffrey de Havilland, was already well advanced by that date.

Only the Voisin's engine, a water-cooled Wolseley V-8 developing a nominal 60hp, its radiator, and possibly a few metal fittings were actually used in the construction of the new machine, which was a two-bay biplane. Its upper wing was of slightly greater span than the lower, the wings originally being rigged with neither stagger nor dihedral. The large, low-aspect-ratio tailplane was of true aerofoil section, contributing to the overall lift, but was set at a smaller angle of incidence than the mainplanes to provide longitudinal stability. It was fastened directly to the upper longerons. The ear-shaped rudder hung from an unbraced sternpost, and there was no fin. Lateral control was by wing warping, the control column being of generous height to give the pilot good leverage and thereby reduce control forces to a level designed to eliminate fatigue.

The fuselage had decking behind the rear seat only, none being provided behind the engine or between the tandem cockpits. The passenger was placed in the forward seat, very close to the centre of gravity, so that no trim changes would occur when the machine was flown with two aboard. The radiator was mounted on the forward centre-section struts, where it benefited from the full force of the slipstream to achieve the necessary cooling with the minimum possible weight of water. The comparative quietness of the water-cooled engine, which was enhanced by the inclusion of silencers in its long exhaust pipes, led to the B.E.1 being dubbed the 'Silent Army Aeroplane'. The undercarriage incorporated long ash skids, intended to prevent the propeller tips touching the ground when the tail was raised, and the tailskid was fully swivelling, allowing a remarkably small turning circle on the ground.

Although photographs taken inside the workshop (known today as the Q27 building) in October 1911 show the aeroplane apparently complete, it did not make its first flight until 3.30pm on 4 December, when de Havilland took it up for a brief circuit, for which he was rewarded with two shillings and sixpence (12 1/2p) in flying pay. He reported that he was satisfied with the aeroplane, but less than happy with throttle control provided by the Wolseley's carburettor, and recommended the substitution of a Claudel unit. This may have been a more complex modification than de Havilland had imagined, because the machine did not fly again until 27 December, when, with the new carburettor installed, he made six short flights, several of them with a passenger. The maximum speed was found to be 55mph, although the engine was not achieving the 1,200rpm stated to be its maximum output (it never did so, despite continual attention).

De Havilland considered that the elevator operating mechanism was too coarsely geared for ease of control, tending to over-correct, and asked for it to be geared down, but otherwise he thought the aeroplane's stability to be good. He also expressed the opinion that too much weight was carried by the tailskid, lengthening the take-off run and, as a consequence, the wheels were repositioned twelve inches to the rear before the aircraft made its next flights, on the first day of the new year, when Mervyn O'Gorman occupied the front seat for two short flights.

By 7 January 1912 the top wing had been re-rigged with three inches of backstagger, presumably to move the centre of pressure slightly to the rear, and a scoop had been fitted in the front of the carburettor's air intake, a measure which increased engine speed by approximately 100rpm to about 1,100rpm.

On 10 January one degree of dihedral was given to each wing panel (an included angle of 178°), and two days later the aeroplane was tested with a Zenith carburettor, which was found to be much less flexible than its predecessor. De Havilland ran out of petrol during the tests, but accomplished the forced landing without mishap. Next day the Claudel was refitted and the B.E.1 was timed at 59mph over a measured three-quartermile course, with both seats occupied.

On 20 January, in a final attempt to improve engine performance, the propeller tips were cut down, producing an engine speed of 1,150rpm. This was the best ever achieved, although it was still just short of the maker's stated figure.

Throughout the remainder of January de Havilland flew the B.E.1 on numerous occasions, carrying many passengers, and he appears to have been completely satisfied with it. He did not suggest any further changes, and flew it in winds of up to 25mph before turning his attention to its twin sister, the B.E.2, which was completed by 1 February 1912.

On 11 March the B.E.1 was formally handed over to Capt C J Burke of the Air Battalion, Royal Engineers. Burke flew it for the first time three days later - the day on which the document which has come to be regarded as the first Certificate of Airworthiness was issued, certifying that the B.E.1 had been fully tested by the Factory.

The machine was given the serial B7, and the following month it became the property of No 2 (Aeroplane) Squadron of the newly formed Royal Flying Corps. In August its serial was changed to 201, an identity it retained throughout the remainder of its long career.

A heavy landing on 31 March 1912 resulted in the B.E.1 being returned to the Factory to be fitted with a new undercarriage. It was also fitted with a compass and an aneroid altimeter. On Thursday 11 April it suffered engine failure while being test flown by Mr Perry, and a wingtip was damaged in the ensuing forced landing. This was soon repaired, and the aeroplane was test flown by de Havilland at 6.00pm the following day. Following some alterations to the elevator cables, it was again test flown on 15 April before being returned to the RFC.

A further engine failure, on 28 May, led to its again being returned to the Factory. As its Wolseley engine was considered to be beyond economic repair, it was replaced by a Renault similar to that in the B.E.2. This engine, being air-cooled, allowed the removal of the radiator from the centre-section struts, with consequent improvements in performance and in the crew's forward view.

Following a test flight by de Havilland on 22 June, 201 was handed back to the Flying Corps, seeing service with No 4 and, later, No 5 Squadron. By the end of 1913 it had amassed a total of 172 flying hours. It had made several visits to the Factory for minor repairs, and had acquired fuselage decking ahead of, and between, the cockpits, making it virtually identical to contemporary B.E.2s. This similarity was further enhanced when its tailplane was replaced by one of slightly reduced area which had become the standard B.E.2 fitting at that time.

At the outbreak of war the B.E.1 was not sent to France, as were most of the RFC's effective aircraft, but remained with a training unit in England. Following a crash in January 1915 it was returned to Farnborough once more for repair, and was reported as still being there the following May. It is recorded as having been at the Central Flying School as late as July 1916, although by that date it had again been rebuilt and had acquired a B.E.2b-type fuselage.

The eventual fate of the B.E.1 is unknown. It merely fades from official records into an obscurity wholly undeserved by the 'revered grandfather of a whole brood of Factory aeroplanes'.

Powerplant: 60hp Wolseley V-8 (later 60hp Renault)

Dimensions:

span 38ft 7 1/2in (upper); 34ft 11 1/2in (lower);

chord 5ft 6in;

gap 6ft 0in

wing area: 374 sq ft

length 29ft 6 1/2in

height 10ft 2in

Performance: (Wolseley)

max speed 59mph (at sea level)

min speed 42mph

climb 155ft/min (to 600ft).

The third machine in the Factory's initial research series, each of which was of a distinct and separate type, was a tractor biplane. It was named the Bleriot Experimental Number 1, or B.E.1. As with other contemporary Farnborough designs, it was ostensibly a reconstruction of another aeroplane, in this case a Voisin which had originally been presented to the War Office by the Duke of Westminster and which, following a crash, had been delivered to the Factory for repair in June 1911. The War Office granted permission for the alterations and additions which O'Gorman had suggested on 12 August 1911, but it is probable that design work, most of which was carried out by Geoffrey de Havilland, was already well advanced by that date.

Only the Voisin's engine, a water-cooled Wolseley V-8 developing a nominal 60hp, its radiator, and possibly a few metal fittings were actually used in the construction of the new machine, which was a two-bay biplane. Its upper wing was of slightly greater span than the lower, the wings originally being rigged with neither stagger nor dihedral. The large, low-aspect-ratio tailplane was of true aerofoil section, contributing to the overall lift, but was set at a smaller angle of incidence than the mainplanes to provide longitudinal stability. It was fastened directly to the upper longerons. The ear-shaped rudder hung from an unbraced sternpost, and there was no fin. Lateral control was by wing warping, the control column being of generous height to give the pilot good leverage and thereby reduce control forces to a level designed to eliminate fatigue.

The fuselage had decking behind the rear seat only, none being provided behind the engine or between the tandem cockpits. The passenger was placed in the forward seat, very close to the centre of gravity, so that no trim changes would occur when the machine was flown with two aboard. The radiator was mounted on the forward centre-section struts, where it benefited from the full force of the slipstream to achieve the necessary cooling with the minimum possible weight of water. The comparative quietness of the water-cooled engine, which was enhanced by the inclusion of silencers in its long exhaust pipes, led to the B.E.1 being dubbed the 'Silent Army Aeroplane'. The undercarriage incorporated long ash skids, intended to prevent the propeller tips touching the ground when the tail was raised, and the tailskid was fully swivelling, allowing a remarkably small turning circle on the ground.

Although photographs taken inside the workshop (known today as the Q27 building) in October 1911 show the aeroplane apparently complete, it did not make its first flight until 3.30pm on 4 December, when de Havilland took it up for a brief circuit, for which he was rewarded with two shillings and sixpence (12 1/2p) in flying pay. He reported that he was satisfied with the aeroplane, but less than happy with throttle control provided by the Wolseley's carburettor, and recommended the substitution of a Claudel unit. This may have been a more complex modification than de Havilland had imagined, because the machine did not fly again until 27 December, when, with the new carburettor installed, he made six short flights, several of them with a passenger. The maximum speed was found to be 55mph, although the engine was not achieving the 1,200rpm stated to be its maximum output (it never did so, despite continual attention).

De Havilland considered that the elevator operating mechanism was too coarsely geared for ease of control, tending to over-correct, and asked for it to be geared down, but otherwise he thought the aeroplane's stability to be good. He also expressed the opinion that too much weight was carried by the tailskid, lengthening the take-off run and, as a consequence, the wheels were repositioned twelve inches to the rear before the aircraft made its next flights, on the first day of the new year, when Mervyn O'Gorman occupied the front seat for two short flights.

By 7 January 1912 the top wing had been re-rigged with three inches of backstagger, presumably to move the centre of pressure slightly to the rear, and a scoop had been fitted in the front of the carburettor's air intake, a measure which increased engine speed by approximately 100rpm to about 1,100rpm.

On 10 January one degree of dihedral was given to each wing panel (an included angle of 178°), and two days later the aeroplane was tested with a Zenith carburettor, which was found to be much less flexible than its predecessor. De Havilland ran out of petrol during the tests, but accomplished the forced landing without mishap. Next day the Claudel was refitted and the B.E.1 was timed at 59mph over a measured three-quartermile course, with both seats occupied.

On 20 January, in a final attempt to improve engine performance, the propeller tips were cut down, producing an engine speed of 1,150rpm. This was the best ever achieved, although it was still just short of the maker's stated figure.

Throughout the remainder of January de Havilland flew the B.E.1 on numerous occasions, carrying many passengers, and he appears to have been completely satisfied with it. He did not suggest any further changes, and flew it in winds of up to 25mph before turning his attention to its twin sister, the B.E.2, which was completed by 1 February 1912.

On 11 March the B.E.1 was formally handed over to Capt C J Burke of the Air Battalion, Royal Engineers. Burke flew it for the first time three days later - the day on which the document which has come to be regarded as the first Certificate of Airworthiness was issued, certifying that the B.E.1 had been fully tested by the Factory.

The machine was given the serial B7, and the following month it became the property of No 2 (Aeroplane) Squadron of the newly formed Royal Flying Corps. In August its serial was changed to 201, an identity it retained throughout the remainder of its long career.

A heavy landing on 31 March 1912 resulted in the B.E.1 being returned to the Factory to be fitted with a new undercarriage. It was also fitted with a compass and an aneroid altimeter. On Thursday 11 April it suffered engine failure while being test flown by Mr Perry, and a wingtip was damaged in the ensuing forced landing. This was soon repaired, and the aeroplane was test flown by de Havilland at 6.00pm the following day. Following some alterations to the elevator cables, it was again test flown on 15 April before being returned to the RFC.

A further engine failure, on 28 May, led to its again being returned to the Factory. As its Wolseley engine was considered to be beyond economic repair, it was replaced by a Renault similar to that in the B.E.2. This engine, being air-cooled, allowed the removal of the radiator from the centre-section struts, with consequent improvements in performance and in the crew's forward view.

Following a test flight by de Havilland on 22 June, 201 was handed back to the Flying Corps, seeing service with No 4 and, later, No 5 Squadron. By the end of 1913 it had amassed a total of 172 flying hours. It had made several visits to the Factory for minor repairs, and had acquired fuselage decking ahead of, and between, the cockpits, making it virtually identical to contemporary B.E.2s. This similarity was further enhanced when its tailplane was replaced by one of slightly reduced area which had become the standard B.E.2 fitting at that time.

At the outbreak of war the B.E.1 was not sent to France, as were most of the RFC's effective aircraft, but remained with a training unit in England. Following a crash in January 1915 it was returned to Farnborough once more for repair, and was reported as still being there the following May. It is recorded as having been at the Central Flying School as late as July 1916, although by that date it had again been rebuilt and had acquired a B.E.2b-type fuselage.

The eventual fate of the B.E.1 is unknown. It merely fades from official records into an obscurity wholly undeserved by the 'revered grandfather of a whole brood of Factory aeroplanes'.

Powerplant: 60hp Wolseley V-8 (later 60hp Renault)

Dimensions:

span 38ft 7 1/2in (upper); 34ft 11 1/2in (lower);

chord 5ft 6in;

gap 6ft 0in

wing area: 374 sq ft

length 29ft 6 1/2in

height 10ft 2in

Performance: (Wolseley)

max speed 59mph (at sea level)

min speed 42mph

climb 155ft/min (to 600ft).

The B.E.I, apparently complete, inside the Factory workshops on 1 October 1911. Its first flight was not made until 4 December.

The aeroplane nearest to the camera is almost certainly 201, the B.E.I , seen here late in its life, by which time it had acquired a B.E.2b-type fuselage.

S.E.1

The first aeroplane built at Farnborough after the hiatus which followed the dismissal of Cody and Dunne came about as a result of a subterfuge, for the War Office denied the Factory the right to design and build aeroplanes. In the late summer of 1910 a Bleriot XII of uncertain history was being operated on Salisbury Plain by a group of Army officers led by Lt Cammell (to whom ownership of the machine has sometimes been attributed), and towards the end of the year suffered considerable damage in a crash, eventually finding its way to Farnborough for repair. One of Bleriot's less-successful designs, the machine was reputed to be very tricky to fly, and although officially known as B1 it was popularly known as the Man-Killer. Mervyn O'Gorman therefore sought War Office permission to redesign the Bleriot and to include controls of the Farman type, so that it might be flown by anyone familiar with the Farman. Such permission was granted, and the Farnborough design team, led by de Havilland and F M Green, set to work on the 'S' class machine which previous study had led O'Gorman to believe would prove most successful.

The result of their endeavours, the S.E.1, bore little resemblance to the tractor monoplane from which it was allegedly 'reconstructed', being a canard pusher biplane and, although the shape of its wings was at least reminiscent of those of the Bleriot, the only actual link between the two machines was the 60hp ENV 'F' engine.

The new machine made its first outing at dawn on 7 June 1911, when de Havilland made some taxying trials and broke two wheel spokes in the process. Therefore the wheels were moved forward to improve the balance. At the same time the twin rudder outriggers were shortened by three feet, bringing the rudders closer to the fuselage, because they were found to be vibrating and causing the mainplanes to flex. At 5.30am the following morning de Havilland made the first flight, even though the undercarriage problem was not yet entirely resolved. The machine flew about a mile, but its propeller shaft was found to have twisted. Following another outing on the 10th, de Havilland decided to restore the wheels to their original positions and to fit a skid under the forward elevators.

The fore and aft stability was reported as good, but de Havilland thought the elevators to be too powerful. After the S.E.1's next flight, made on 28 June, their area was reduced by cutting four inches from their trailing edges. However, on 3 July de Havilland recorded that they were still too powerful, and arranged construction of a new canard surface. He also recorded that he was experiencing difficulty in turning, and had the body stripped of fabric to reduce forward keel area, but this made little improvement and the fabric was therefore reinstated. The earlier shortening of the rudder outriggers had clearly been a contributory factor to this problem, and by the 14th an additional rudder had been installed on the nose of the machine, operating in conjunction with those at the rear. At the same time the new elevators were fitted and the dihedral reduced. While turning was now improved, the S.E.1's designer/test pilot was still not satisfied, recording his opinion that the rear rudders appeared to be too sensitive. In addition, the radiators, which were on the fuselage sides, were found to boil over whenever the machine was at rest.

In the next two weeks the front skids were moved back, the wheels were again repositioned, and stronger rubber cords were fitted to the undercarriage. Several half-turns were made on 1 August, and on the 16th de Havilland successfully flew it to Laffan's Plain and back twice. The day's flying was brought to a premature end by a choked carburettor.

Two days later Lt Theodore Ridge, the Factory's Assistant Superintendent, took the S.E.1 up for the first time, despite de Havilland's advice that he should not do so because it was still a tricky machine. Ridge, who is reputed to have been something of a martinet, ignored him, sideslipped while attempting a sharp turn and crashed, receiving injuries from which he died later the same day. Thus the Factory's first design had resulted in tragedy, and the Man-Killer had finally lived up to its name.

The type was presumably acknowledged to have been a failure, and the canard concept was not continued with, subsequent 'S.E.' types being of the 'scouting' rather than 'Santos' class.

Powerplant: 60hp ENV type 'F' water-cooled V-8

Dimensions:

span 38ft 0in;

dihedral 2 1/2;

wing area 382 sq ft;

length 29ft 0in;

height 11ft 6in.

Weights:

1,200lb (empty);

1,640lb (loaded).

The first aeroplane built at Farnborough after the hiatus which followed the dismissal of Cody and Dunne came about as a result of a subterfuge, for the War Office denied the Factory the right to design and build aeroplanes. In the late summer of 1910 a Bleriot XII of uncertain history was being operated on Salisbury Plain by a group of Army officers led by Lt Cammell (to whom ownership of the machine has sometimes been attributed), and towards the end of the year suffered considerable damage in a crash, eventually finding its way to Farnborough for repair. One of Bleriot's less-successful designs, the machine was reputed to be very tricky to fly, and although officially known as B1 it was popularly known as the Man-Killer. Mervyn O'Gorman therefore sought War Office permission to redesign the Bleriot and to include controls of the Farman type, so that it might be flown by anyone familiar with the Farman. Such permission was granted, and the Farnborough design team, led by de Havilland and F M Green, set to work on the 'S' class machine which previous study had led O'Gorman to believe would prove most successful.

The result of their endeavours, the S.E.1, bore little resemblance to the tractor monoplane from which it was allegedly 'reconstructed', being a canard pusher biplane and, although the shape of its wings was at least reminiscent of those of the Bleriot, the only actual link between the two machines was the 60hp ENV 'F' engine.

The new machine made its first outing at dawn on 7 June 1911, when de Havilland made some taxying trials and broke two wheel spokes in the process. Therefore the wheels were moved forward to improve the balance. At the same time the twin rudder outriggers were shortened by three feet, bringing the rudders closer to the fuselage, because they were found to be vibrating and causing the mainplanes to flex. At 5.30am the following morning de Havilland made the first flight, even though the undercarriage problem was not yet entirely resolved. The machine flew about a mile, but its propeller shaft was found to have twisted. Following another outing on the 10th, de Havilland decided to restore the wheels to their original positions and to fit a skid under the forward elevators.

The fore and aft stability was reported as good, but de Havilland thought the elevators to be too powerful. After the S.E.1's next flight, made on 28 June, their area was reduced by cutting four inches from their trailing edges. However, on 3 July de Havilland recorded that they were still too powerful, and arranged construction of a new canard surface. He also recorded that he was experiencing difficulty in turning, and had the body stripped of fabric to reduce forward keel area, but this made little improvement and the fabric was therefore reinstated. The earlier shortening of the rudder outriggers had clearly been a contributory factor to this problem, and by the 14th an additional rudder had been installed on the nose of the machine, operating in conjunction with those at the rear. At the same time the new elevators were fitted and the dihedral reduced. While turning was now improved, the S.E.1's designer/test pilot was still not satisfied, recording his opinion that the rear rudders appeared to be too sensitive. In addition, the radiators, which were on the fuselage sides, were found to boil over whenever the machine was at rest.

In the next two weeks the front skids were moved back, the wheels were again repositioned, and stronger rubber cords were fitted to the undercarriage. Several half-turns were made on 1 August, and on the 16th de Havilland successfully flew it to Laffan's Plain and back twice. The day's flying was brought to a premature end by a choked carburettor.

Two days later Lt Theodore Ridge, the Factory's Assistant Superintendent, took the S.E.1 up for the first time, despite de Havilland's advice that he should not do so because it was still a tricky machine. Ridge, who is reputed to have been something of a martinet, ignored him, sideslipped while attempting a sharp turn and crashed, receiving injuries from which he died later the same day. Thus the Factory's first design had resulted in tragedy, and the Man-Killer had finally lived up to its name.

The type was presumably acknowledged to have been a failure, and the canard concept was not continued with, subsequent 'S.E.' types being of the 'scouting' rather than 'Santos' class.

Powerplant: 60hp ENV type 'F' water-cooled V-8

Dimensions:

span 38ft 0in;

dihedral 2 1/2;

wing area 382 sq ft;

length 29ft 0in;

height 11ft 6in.

Weights:

1,200lb (empty);

1,640lb (loaded).

B.E.2

The B.E.2 was virtually a copy of the B.E.1, except that it was powered, from the start, by a 60hp Renault V-8 air-cooled engine. Its designation was not intended to identify it as a separate design, but merely to denote that it was the second machine built in the general-purpose tractor, or Bleriot Experimental, class. Construction of the B.E.2 was well advanced before the B.E.1 flew, the 'reconstruction' subterfuge again being used to explain its origins. Both the ill-fated S.E.1 and a damaged Breguet were named, on different occasions, as the parent aeroplane, although the latter seems more likely as it did, at least, have a Renault engine.

Among the few differences between the two B.E.s was the routeing of the newer machine's exhaust pipes down through the fuselage rather than outside it, achieving a minor reduction in drag, albeit at the expense of a consequent increase in fire risk. The B.E.2's undercarriage incorporated radius rods to locate the axle positively, particularly against longitudinal movement, and the wheel spokes were fabric covered, an innovation which not only reduced their resistance but was considered by de Havilland to 'damp out lateral oscillations'. The undercarriage skids were shorter than those of the B.E.1, lacking the long projection ahead of the propeller.

The B.E.2 made its maiden flight on 1 February 1912, with de Havilland at the controls. He appears to have judged it entirely satisfactory as built, for no modifications are recorded to have been required. This is not altogether surprising when it is remembered that all the necessary development work had effectively been carried out during the testing of the B.E.1.

De Havilland lost little time in taking up passengers, among whom were F M Green and S Hiscocks. He found its performance to be superior to that of the Wolseley-powered B.E.1 in speed and in climb.

On 21 February, after it had been fitted with a Claudel carburettor, it was flown by de Havilland to a height of 2,600ft. Two days later it made a return flight to Brooklands, covering about fifty miles.

Towards the end of March a wireless set which had been constructed at the Factory was installed in the B.E.2. Experimental transmissions were started on the 26th, but were curtailed when the equipment broke down. The result of further tests on 28 March and 1 and 2 April were described as good, and for the next week or so numerous passengers were taken up so that they could sample the novelty of airborne wireless for themselves. By 1 May a new amphibian undercarriage having both floats and wheels had been fitted, but it was found to be unsuitable for 'rolling' (taxying) and was removed. Two days later power had been increased by the fitting of a 70hp Renault, and the B.E.2's speed was measured at 68mph.

On 11 May the machine was flown to Fleet Pond, where the floats were refitted, but the trials were inconclusive because their draught proved too great for the pond and the tail float was found to be set at too small an angle. Modifications were completed by the evening, and a short flight from the water was made, but the floats were damaged on landing. It seems probable that they were not repaired, as no record has been found of any further trials with this undercarriage.

On Friday 17 May de Havilland flew the B.E.2 before the King and Queen in company with some other machines, as part of His Majesty's official review of the armed forces, and on the 31st he climbed it to 6,050ft in fifteen minutes.

By early the following month the B.E.2 had flown more than 500 miles since being fitted with the larger engine, and it continued to be used almost every day for tests of one kind or another.

During the second week of August de Havilland flew the aeroplane to Larkhill, on Salisbury Plain, where the Military Aeroplane Trials were taking place. Because Mervyn O'Gorman, in his capacity as Factory Superintendent, was one of the competition judges, the B.E.2 was clearly ineligible for the competition, but it still undertook many of the tests hors concours and achieved overall results at least equal to those of the eventual winner, the massive Cody 'Cathedral' (itself a development of the Balloon Factory's British Army Aeroplane No 1, built at Farnborough four years previously). Its use as a general 'hack', taking officials and pressmen to and fro throughout the trials, did a great deal to convince observers that aviation had reached a level of practicality which had been previously unappreciated.

On 12 August de Havilland, accompanied by Maj F H Sykes, took off at about 5.00am and, in the still, cool air of early morning, decided to test the B.E.2's climbing powers to the full. They eventually reached an altitude of 10,560ft, capturing the British record not only for flights with a passenger, but for solo flights as well.

Although the purpose of the Military Trials was to decide with which machine the RFC should be equipped, the B.E.2 was clearly more suitable than the actual winner, and the War Office decided to adopt the Factory's creation. Although a few further examples were built at Farnborough, much to the chagrin of C G Grey, orders were placed with private constructors such as the British and Colonial Aeroplane Company and Vickers. All such production machines appear to have been designated B.E.2a.

Powerplant: 60hp Renault V-8; 70hp Renault V-8

Dimensions:

span 38ft 7 1/8in (upper); 34ft 11 5/8in (lower);

chord 5ft 6in;

gap 6ft 0in;

wing area 374 sq ft;

length 28ft 4in;

height 10ft 2in;

propeller diameter 8ft 10in;

wheel track 6ft 2in;

tailplane span 11ft 0in;

tailplane area 52 sq ft;

elevator area 25 sq ft;

rudder area 12 sq ft.

Weight: 1,700lb (loaded).

Performance: (70hp)

max speed 70mph at sea level;

min speed 40mph;

climb 244ft/min to 1,000ft (60hp);

305ft/min to 1,000ft (70hp);

glide angle 1 in 6 1/4.

B.E.2a

It now seems certain that the designation B.E.2a was applied to all production B.E.2s, or to those built by contractors, rather than to any specific variant, for the earliest examples were almost identical to the prototype, certain modifications being made later without any change in designation. The 'a' suffix was not consistently applied in service use, but this did not cause any confusion at the time because virtually all the B.E.2s were 2as. Drawings bearing the title B.E.2a are dated as early as February 1912, the type is described in R & M 66, dated 12 June 1912, and the first production order was placed in August 1912, apparently before the final result of the Military Trials was known.

These early machines had unequal-span wings of NPL3a section and large lifting tailplanes exactly similar to that of the original B.E.2, the only discernible difference being the addition of a fuselage decking between the seats. Later examples, which formed the majority, had equal-span wings of a new aerofoil section which allowed a deeper rear spar and required an angle of incidence of only 3 1/2, compared with the 4 1/2 of the earlier wing, resulting in a reduction in drag without any loss of lift. Their tailplane area was reduced, the spar remaining the same to allow the original elevators to be used, and the chord being reduced to give a surface which was roughly semicircular in planform. The upper fuselage decking remained at its original length, resulting in a small flat area immediately in front of the tailplane. The new tailplane was designated T.P.2, the original surface retrospectively becoming T.P.1

Total production of the B.E.2a cannot now be quantified exactly, but appears to have been just short of 100 machines. Nevertheless, it was still the most numerous single type on the strength of the diminutive prewar RFC. Several B.E.2as served with the Royal Naval Air Service and, in addition, the type saw service in India and with the Australian Air Service. It also provided the Royal Aircraft Factory with a reliable test vehicle of reasonable performance and predictable handling with which to conduct its wide-ranging aeronautical research.

As part of E T Busk's investigations into aeroplane stability one B.E.2a, No 601, was fitted with two small fins on its upper wing, immediately over the centre-section struts. A high-aspect-ratio tailplane of rectangular planform was also fitted, braced to an inverted vee-shaped kingpost on the fuselage centreline. Known as T.P.3, it had a similar area to its semicircular predecessor, T.P.2, but was of a symmetrical aerofoil section and provided no lift in the normal flying position.

In another experiment, possibly connected with that above, No 206 (which had started its life as the B.E.6) was fitted with interplane struts which had greatly increased chord at their upper end, and were known as 'fin struts'. This aircraft was also fitted with an experimental oleo undercarriage, but appears to have reverted to its original unit.

The type also continued the wireless development tests started with the original B.E.2, aircraft 240 and 336 being among the machines chosen to carry the primitive equipment aloft.

A number of spectacular flights were made by B.E.2as piloted by regular service personnel. Number 218, a Bristol-built example, was fitted with an additional petrol tank in its faired-over front cockpit, increasing its total capacity to about fifty-four gallons. On 22 November 1913 it was flown by Capt Longcroft of No 2 Squadron from their base at Montrose directly to Portsmouth, and then, without stopping, back to Farnborough, covering a total of 560 miles in 7hr 20min. This prodigious achievement won Longcroft the 1913 Britannia Trophy for the longest flight of that year. On 13 December 1913 Capt J M Salmond, flying a B.E.2a from Upavon on Salisbury Plain, reached an altitude of 13,140ft, thereby setting a new solo British record.

A number of B.E.2as went to France with the RFC at the outbreak of the war. One of them, a No 4 Squadron machine piloted by Lt G W Mapplebeck, shared with Joubert de la Ferte's Bleriot the distinction of carrying out Britain's first active-service reconnaissance.

Despite this, and many other invaluable contributions to the conduct of the war, the B.E.2as were rapidly replaced by more recent designs and returned to England, where they gave equally useful service with training establishments.

Powerplant: 70hp Renault V-8

Dimensions:

span 36ft 11 1/8in;

chord 5ft 6in;

gap 6ft 0in;

wing area 376sqft;

stagger minus 2in;

dihedral 2°;

length; 28ft 4in;

height 10ft 2in;

tailplane area 34 sqft;

Weights: 1,100lb (empty);

1,600lb (loaded).

Performance:

max speed 74mph at sea level;

endurance 3hrs;

climb 9min to 3,000ft;

30min to 6,000ft.

B.E.2b

The B.E.2b was developed early in 1914 to afford its crew better protection from the elements, and had a modified fuselage top-decking with shallower cockpit cutouts. The rudder and elevator control runs were also revised, but in all other respects the B.E.2b was similar to the earlier model. It was built by a number of contractors. After the outbreak of war comparatively large orders were placed, several with companies not then experienced in large-scale production and, although some machines were eventually completed as B.E.2cs, the last B.E.2bs were finally delivered to the RFC in February 1917. By that time they had long been superseded by later variants which were themselves already approaching obsolescence.

Although it was usually unarmed, except perhaps for a revolver or service rifle carried by the observer, the B.E.2b was occasionally equipped to carry a few small bombs. The first Victoria Cross to be awarded to an airman was won by the pilot of B.E.2b 687, Lt W B Rhodes Moorhouse of No 2 Squadron, who, on 26 April 1915, carried out a bombing attack on the railway station at Courtrai. Although he received numerous wounds from retaliatory ground fire, he managed to bring his machine back. His injuries later proved fatal.

The B.E.2b remained in use with training squadrons, albeit in ever-diminishing numbers, right up to the Armistice. Several machines were fitted with components such as fins, sump cowlings and even undercarriages from later variants, either as 'improvements' or because the correct spares were no longer available.

Dimensions as B.E.2a.

B.E.5

The fifth of the Royal Aircraft Factory's series of two-seat general-purpose tractor biplanes returned to the B.E. 1/2 layout, but used a 60hp ENV 'F' engine recovered from the damaged Howard Wright biplane of which it was ostensibly a 'reconstruction'. Being a water-cooled engine, the ENV obviously needed a radiator, and this was mounted on the forward centre-section struts in a manner similar to that on the B.E.1.

The B.E.5's first flight was made on 27 June 1912, only three days after that of the B.E.4, and it was handed over to the RFC on 18 July. It served with No 2 (Aeroplane) Squadron for a few weeks before returning to the Factory to be re-engined with a V-8 Renault. It thus became, in effect, a standard B.E.2, and was thereafter regarded as such in service. After being returned to the RFC it served briefly with No 3 Squadron before returning to No 2, and was allotted the serial 205.

On 27 May 1913 the starboard upper wing collapsed while the aircraft was making a gliding turn at a height of about 2,500ft, and the pilot, Lt Desmond Arthur, was thrown out and killed. An investigation conducted by the Royal Aero Club's Accident Investigation Committee concluded that the cause of the disaster was a badly spliced repair near the tip of the rear spar, although there was no record of the repair being made either by the Royal Aircraft Factory or while the machine was in service. In addition to prompting the suggestion that all such repairs should be properly inspected and the name of those carrying out the work recorded, the incident triggered another attack on the Royal Aircraft Factory by C G Grey in the pages of The Aeroplane. The machine was officially struck off charge on 25 September 1915.

Data as B . E . 2.

B.E.6

Officially a 'reconstruction' of the ill-fated S.E.1, and powered by its 60hp ENV engine, the B.E.6 was identical to the B.E.5 and was built at the same time, its designation being intended not to distinguish it as a separate type, but merely to identify it as the sixth in the B.E. series of tractor machines.

The ENV engine may have sustained more damage in the crash of the S.E.1 than had been realised, for the B.E.6 did not make its first flight until 5 September 1912, some months after its sister. While it is not recorded how it was powered on that occasion, it was fitted with a 60hp Renault when it was handed over to the RFC a few days later, and it is probable that the ENV was never actually used.

The B.E.6 was given the serial 206, and seems never to have been regarded as anything other than a standard B.E.2, which, with its Renault engine, is effectively what it was. By September 1914 it had flown a total of 111 hours and, following a period with No 2 Squadron, it had been transferred first to No 4 Squadron and then to No 6, with whom it saw active service in France before being relegated to training duties back in England.

Some time during 1914 it underwent an engine change, the replacement being the 70hp Renault that was, at that time, the standard power unit for the B.E.2. Its further career and eventual fate have not been discovered.

Data as B.E.2.