Книги

Putnam

P.Lewis

The British Fighter since 1912

73

P.Lewis - The British Fighter since 1912 /Putnam/

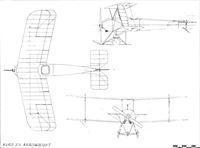

Among the single-seat fighters designed during 1915, as weapons to deal with the marauding Zeppelins, was the A.D. Scout, known also as the Sparrow, Harris Booth of the Air Department of the Admiralty being the man responsible for the design. The machine was intended to bear aloft the Davis recoilless gun and this was to be housed in the lower part of the pusher biplane’s nacelle.

A comparatively large gap separated the two pairs of wings, and the nacelle was attached to the underside of the upper pairs of planes. Parallel struts were incorporated in the undercarriage, their length resulting in the cockpit being at an inordinate height above ground level. Extremely large tailplane and elevator surfaces, short-coupled, were carried by the four tail-booms, in between which revolved the pusher propeller and its 80 h.p. Gnome engine. The very narrow track of the wheels combined with the high centre of gravity of the machine, could have resulted only in gross unwieldiness and instability while taxiing and during take-off and landing. Strut-connected ailerons were incorporated on all four of the single-bay wings and twin fins and rudders filled the gap at the rear of the tail booms.

The whole concept was an unfortunate and unsatisfactory one, about the only point in its favour being the fine view enjoyed by the otherwise hapless pilot. Test flights, soon proved the fallacy of the design, to which two airframes were constructed by Blackburn. An order for a further pair of A.D. Scouts was placed with Hewlett and Blondeau but confirmation of their actual building is lacking.

A comparatively large gap separated the two pairs of wings, and the nacelle was attached to the underside of the upper pairs of planes. Parallel struts were incorporated in the undercarriage, their length resulting in the cockpit being at an inordinate height above ground level. Extremely large tailplane and elevator surfaces, short-coupled, were carried by the four tail-booms, in between which revolved the pusher propeller and its 80 h.p. Gnome engine. The very narrow track of the wheels combined with the high centre of gravity of the machine, could have resulted only in gross unwieldiness and instability while taxiing and during take-off and landing. Strut-connected ailerons were incorporated on all four of the single-bay wings and twin fins and rudders filled the gap at the rear of the tail booms.

The whole concept was an unfortunate and unsatisfactory one, about the only point in its favour being the fine view enjoyed by the otherwise hapless pilot. Test flights, soon proved the fallacy of the design, to which two airframes were constructed by Blackburn. An order for a further pair of A.D. Scouts was placed with Hewlett and Blondeau but confirmation of their actual building is lacking.

The pair of A.D. Sparrow Scouts, 1536 and 1537, built by Blackburn seen under construction at Olympia Works, Leeds.

A rather curious event took place during 1917 at Mudros in the Aegean which, although it contributed nothing to fighter development, deserves to be recorded as an example of initiative and ingenuity. During his service on the station with No. 2 Wing, R.N.A.S., Flt.Lt. J. W. Alcock, well known in flying circles before the 1914-18 War and to become famous after the Armistice for his trans-Atlantic flight with Lt. A. W. Brown, designed a single-seat fighter biplane which was put together from Sopwith Triplane and Pup parts. Two engines were tried in the Alcock A.I Scout, or Sopwith Mouse as Alcock called it; the first was a 100 h.p. Monosoupape Gnome, followed by a 110 h.p. Clerget. Unluckily, Alcock was taken prisoner before his brainchild was ready but the machine was test-flown at Mudros and Stavros after completion by his colleagues. The A.I’s armament consisted of a pair of Vickers guns.

Yet another tractor scout had appeared within a month of the outbreak of war. This was the F.K.1, built by Sir W. G. Armstrong Whitworth and Co., and designed for them by a Dutch designer, Frederick Koolhoven, whose name was to be perpetuated by a prolific series of aircraft to appear under his signature for many years ahead. Before drafting the F.K.1, his first design for Armstrong Whitworth, Koolhoven had accumulated considerable experience through the successful Deperdussin monoplanes.

In the new scout the monoplane formula was disregarded, despite its inherent quality of speed, and the F.K.1 made its debut in September, 1914. A relatively simple biplane in every way, it showed evidence of French practice in the horizontal knife-edge termination of the rear fuselage and in the omission of a fixed tailplane. The upper wings were taken over the fuselage at a considerable gap on inverted-V centre-section struts and this feature, combined with undercarriage legs spread wide apart fore and aft, gave the whole machine a rather gawky appearance. The 80 h.p. Gnome, around which the F.K.1 had been designed, was not obtainable so it flew instead with a 50 h.p. Gnome.

The machine was modified after early tests and was given a normal fixed tailplane and larger, inversely-tapered ailerons. The F.K.1’s top speed of 75 m.p.h. on its low power reduced any chances that it might have had of competing with its counterparts from Bristol, Martin-Handasyde and Sopwith for orders and the design was abandoned.

In the new scout the monoplane formula was disregarded, despite its inherent quality of speed, and the F.K.1 made its debut in September, 1914. A relatively simple biplane in every way, it showed evidence of French practice in the horizontal knife-edge termination of the rear fuselage and in the omission of a fixed tailplane. The upper wings were taken over the fuselage at a considerable gap on inverted-V centre-section struts and this feature, combined with undercarriage legs spread wide apart fore and aft, gave the whole machine a rather gawky appearance. The 80 h.p. Gnome, around which the F.K.1 had been designed, was not obtainable so it flew instead with a 50 h.p. Gnome.

The machine was modified after early tests and was given a normal fixed tailplane and larger, inversely-tapered ailerons. The F.K.1’s top speed of 75 m.p.h. on its low power reduced any chances that it might have had of competing with its counterparts from Bristol, Martin-Handasyde and Sopwith for orders and the design was abandoned.

The F.K.11 was not proceeded with but another design from Armstrong Whitworth, the three-seat F.K.5, also exhibited some equally remarkable features. It was built as the result of a War Office requirement for a multi-seat, long-range escort and anti-Zeppelin fighter, a specification to which Vickers and Sopwith also constructed prototypes.

Armstrong Whitworth proceeded to build the F.K.5 as a large triplane with its central planes of much greater span than those above and below. The 250 h.p. Rolls-Royce engine turned its propeller immediately in front of the leading edge and between the pair of gunners’ nacelles fitted to the centre wings. A revised version as the F.K.6 was built with a different fuselage, undercarriage and nacelles but, as with so many extremely unconventional designs, the machine was not a success.

Armstrong Whitworth proceeded to build the F.K.5 as a large triplane with its central planes of much greater span than those above and below. The 250 h.p. Rolls-Royce engine turned its propeller immediately in front of the leading edge and between the pair of gunners’ nacelles fitted to the centre wings. A revised version as the F.K.6 was built with a different fuselage, undercarriage and nacelles but, as with so many extremely unconventional designs, the machine was not a success.

In the unending quest for fighter supremacy designers in Britain explored most layouts and, in 1916, the Armstrong Whitworth designer F. Koolhoven was responsible for a two-seat fighter reconnaissance quadruplane which, despite the complexity of its four wings, struts and pair of cockpits was, none the less, a clean and pleasing machine, especially in its final form. The prototype used the 110 h.p. Clerget engine while the modified later version, of which a few were built, had the 130 h.p. Clerget. Tests showed that the F.K.10 was not a particularly successful machine and it remained simply one of the more unusual designs of the 1914-18 War.

<...>

Following the F.K.10 quadruplane design Armstrong Whitworth investigated an extraordinary development by Koolhoven to be known as the F.K.11 which was intended to be borne on a set of wings reminiscent of those tested by Horatio Phillips a decade before. The F.K.11’s small-chord mainplanes would have numbered fifteen, set with pronounced stagger on the same style of fuselage as that used on the F.K.10.

The F.K.11 was not proceeded.

<...>

Following the F.K.10 quadruplane design Armstrong Whitworth investigated an extraordinary development by Koolhoven to be known as the F.K.11 which was intended to be borne on a set of wings reminiscent of those tested by Horatio Phillips a decade before. The F.K.11’s small-chord mainplanes would have numbered fifteen, set with pronounced stagger on the same style of fuselage as that used on the F.K.10.

The F.K.11 was not proceeded.

The 230 h.p. Bentley B.R.2 rotary was also selected by F. Murphy as the engine for the F.M.4 single-seat biplane fighter which he evolved for Armstrong Whitworth when, in 1917, he succeeded F. Koolhoven as designer. Named Armadillo, the machine was far from elegant in appearance and embodied a boxlike fuselage which filled the relatively narrow gap between the two-bay wings. The two Vickers guns were housed in a peculiar fairing which curved from the front face of the engine cowling to the top of the upper wings. Being tested in September, 1918, the Armadillo prototype X19 was a late-comer among the War’s fighters and, with its comparatively poor view from the cockpit, stood little chance of a production order.

Two further single-seat fighters were planned under the R.A.F. Type 1 conditions. These were the Armstrong Whitworth Ara and the Nieuport Nighthawk but neither machine was ready before the beginning of 1919.

Designed by F. Murphy, the Ara shared the same unhappy type of engine as the Nighthawk - the 320 h.p. A.B.C. Dragonfly 1 - and retained the same two-bay wing layout as Murphy’s earlier Armadillo. The fuselage was unusually deep-sided towards the rear where it would normally have been expected to have tapered steadily in elevation. In F4971, the first prototype, the fuselage rested on the lower wings but F4972 introduced greater gap between the mainplanes, resulting in the lower wings passing beneath the fuselage. The fore-part of the fuselage housed two Vickers guns and the Ara turned in the useful top speed at ground level of 150 m.p.h. The Ara was typical of the trend of the final generation of fighters which made their debut at the end of the War and this styling was shared by the Nieuport Company’s Nighthawk.

Designed by F. Murphy, the Ara shared the same unhappy type of engine as the Nighthawk - the 320 h.p. A.B.C. Dragonfly 1 - and retained the same two-bay wing layout as Murphy’s earlier Armadillo. The fuselage was unusually deep-sided towards the rear where it would normally have been expected to have tapered steadily in elevation. In F4971, the first prototype, the fuselage rested on the lower wings but F4972 introduced greater gap between the mainplanes, resulting in the lower wings passing beneath the fuselage. The fore-part of the fuselage housed two Vickers guns and the Ara turned in the useful top speed at ground level of 150 m.p.h. The Ara was typical of the trend of the final generation of fighters which made their debut at the end of the War and this styling was shared by the Nieuport Company’s Nighthawk.

During this time, one of the most important of the new British singleseat fighters of the early post-War era was being developed at its prototype stage. Prior to Maj. F. M. Green’s departure in 1917 from the Royal Aircraft Factory to design for the aviation section of the Siddeley-Deasy Motor Car Co. at Coventry, he prepared the preliminary layout for another fighter in the Factory’s Scouting Experimental series, based on the installation of a two-row fourteen-cylinder radial engine - the 300 h.p. R.A.F.8. Once Maj. Green, J. Lloyd and S. D. Heron had settled down to work at the Siddeley-Deasy offices, the design was developed in earnest to emerge as a sprightly-looking biplane, the Siddeley S.R.2 Siskin, in mid-1919. At the same time, at Maj. Green’s instigation the Company had gone ahead with the development of the R.A.F.8 engine and completed it as the Jaguar.

The Siskin flew first in July, 1919, with the unfortunate choice of the 320 h.p. A.B.C. Dragonfly 1 as its power plant, but this was eventually replaced by the Jaguar which had been turned into a reliable and successful unit by the Summer of 1922. The prototype Siskin followed the usual all-wood construction and fabric covering of the war period and carried the standard pair of Vickers guns on its nose-decking as armament. The Siskin was not ordered at the time but much was to be heard of it later in its revised and developed version.

The Siskin flew first in July, 1919, with the unfortunate choice of the 320 h.p. A.B.C. Dragonfly 1 as its power plant, but this was eventually replaced by the Jaguar which had been turned into a reliable and successful unit by the Summer of 1922. The prototype Siskin followed the usual all-wood construction and fabric covering of the war period and carried the standard pair of Vickers guns on its nose-decking as armament. The Siskin was not ordered at the time but much was to be heard of it later in its revised and developed version.

Often alternative combinations of armament were experimented with on the squadrons but only comparatively rarely did a pilot fighting at the Front have a direct say in the design of a fighter aircraft itself. One such case was in the Austin-Ball A.F.B.1 single-seat biplane which was finished in July, 1917. Until the time of his death in action on 7th May, 1917, Ball had kept in direct touch with the evolution of the A.F.B.1. Although an ugly machine, its saving grace was a maximum speed of 138 m.p.h. at ground level on the 200 h.p. of its Hispano-Suiza engine and a good performance in rate of climb and ceiling. The installation of the A.F.B.1’s pair of Lewis guns was of note; that in the fuselage fired through the centre of the propeller shaft, while the other occupied a Foster mounting on the upper centre-section. Despite its abilities the machine was not selected finally for production.

During 1917 the Austin Motor Co. decided to design a single-seat fighter to Specification A.1A but, rather surprisingly in view of the generally-conceded superiority by then of the well-developed biplane, their tender appeared at the beginning of 1918 as a triplane - the A.F.T.3 Osprey. The machine was fairly small and, as was to be expected with the power of the 230 h.p. Bentley B.R.2, the overall performance was quite creditable. The standard armament scheduled for the Osprey was a pair of fuselage-mounted Vickers but X15, the sole prototype, carried temporarily a Lewis gun in addition. However, against the new biplanes then appearing the Osprey stood relatively little chance of adoption and went the way of so many hopefully-created prototypes.

The sole example of the A.F.T.3 Osprey to be completed and flown.

The A.F.T.3 Osprey was intended to compete with the Snipe, but proved inferior.

The A.F.T.3 Osprey was intended to compete with the Snipe, but proved inferior.

The same fate befell another aeroplane built by Austin before the War’s end. This was a proposed replacement for the Bristol F.2B, named the Greyhound, and was a two-seat, two-bay biplane armed with two Vickers guns for the pilot and a single Lewis for the gunner. The machine was a promising design, constituting a serious effort to embody in every way recommendations resulting from active operation of previous types. To enable the Greyhound to fulfil its purpose of fighter reconnaissance to the best advantage, very comprehensive equipment was installed. One less happy aspect of the design was in the choice of engine, the 320 h.p. A.B.C. Dragonfly 1, a unit which was to prove unreliable and the undoing, regrettably, of a number of prototypes designed around it in the hope of making good use of its expected high output of power.

Tempted also by the idea of the small scout, A. V. Roe showed their conception in the Type 511 Arrowscout, in reality a scaled-down 504 with single-bay sweptback wings and an 80 h.p. Gnome. The machine was tested by F. P. Raynham and turned in a top speed of 100 m.p.h. but made no further progress. One of its advanced features was the incorporation of airbrakes in the lower wing roots, an early example of their use.

The unqualified success of the Avro 504 prompted the parent company to construct during early 1916 a two-seat fighter variant under the type number 521. The wing structure was cleaned up by conversion to single-bay cellules and the same streamlining process applied to the undercarriage resulted in a simple V-strut structure. The rear cockpit was set some distance behind that of the pilot, above whom was a generous cut-out in the trailing edge of the centre-section.

The 110 h.p. Clerget powered the Avro 521, which was test-flown by F. P. Raynham and found to have disagreeable flying characteristics. Nevertheless, despite the crash of the prototype in the hands of an R.F.C. pilot, twenty-five production 521s were built but did not apparently reach operational service in their intended role.

The 110 h.p. Clerget powered the Avro 521, which was test-flown by F. P. Raynham and found to have disagreeable flying characteristics. Nevertheless, despite the crash of the prototype in the hands of an R.F.C. pilot, twenty-five production 521s were built but did not apparently reach operational service in their intended role.

Another auspicious two-seat design which was unable to make the grade once the Bristol machine had gained a firm foothold was Avro’s 530, completed in July, 1917. Careful attention had been paid to producing an airframe for the two-bay biplane which was designed to use the 300 h.p. Hispano-Suiza engine. The current shortage of this engine dictated the installation of the 200 h.p. version of the same make and the 530 was tested also with the 200 h.p. Sunbeam. Unusual features of the design were the deep fuselage filling the entire wing gap, the fairings applied to fill the openings between the undercarriage V struts, and the flaps which formed the trailing edges of the wings. Two guns were carried - a Vickers for the pilot and a Scarff-mounted Lewis in the rear cockpit.

A. V. Roe followed up their 530 two-seat fighter with another fighter design - the single-seat 531 Spider. The new prototype was completed by April, 1918, and turned out to be a 110 h.p. le Rhone-engined biplane of striking appearance. In the interest of quick production particular attention was paid to using readily-available 504K parts in the airframe but, despite this admirable object, the Spider was a distinctive machine. The main feature which caught the eye immediately was the system of three pairs of V struts on each side which braced the unequal-span wings without the assistance of bracing wires, the upper wings being set close to the top of the fuselage so that the pilot’s head projected through the open centre-section. A peculiar point about the Spider’s armament was the fitting of only one Vickers gun at a time when two machine-guns had become more or less standard. Tests proved the machine to be excellent for its purpose with admirable manoeuvrability, its top speed at ground level with the 130 h.p. Clerget fitted being 120 m.p.h.

Another version of the Spider was planned as the 531A, based on the 130 h.p. Clerget with different biplane wing cellules and orthodox struts and wire bracing.

Another version of the Spider was planned as the 531A, based on the 130 h.p. Clerget with different biplane wing cellules and orthodox struts and wire bracing.

While the Camel, S.E.5 and other production types continued to bear the brunt of the fighting in the air, prototypes of new fighters continued to appear in Britain. Among the companies which made bids to establish themselves as fighter constructors was the paradoxically-named British Aerial Transport Co., the chief designer of which was F. Koolhoven, late of Armstrong Whitworth. Koolhoven’s initial design for his new firm was the F.K.22 Bat, a single-seat fighter biplane drawn up around the 120 h.p. A.B.C. Mosquito radial engine, the airframe consisting of two-bay, equal-span wings fitted to a shapely monocoque fuselage. A particularly unusual feature of the F.K.22 was the location of the cockpit immediately underneath the upper wings so that the pilot’s head projected above the centre-section. Failure of the proposed engine brought about redesign to make use of a later A.B.C. radial unit, the 170 h.p. Wasp, with which the Bat was renamed Bantam. Cancellation of development of the Wasp resulted in flights being made early in 1918 with rotaries - the 100 h.p. Monosoupape Gnome and the 110 h.p. le Rhone.

To distinguish it the Gnome version was referred to as the Bantam Mk.II, while the F.K.23, a smaller version, became the Bantam Mk.I. The Mk.I was bedevilled by dangerous spinning characteristics but the design’s speed and manoeuvrability resulted in an initial batch being ordered, with several alterations which went most of the way to eliminating the early faults. After nine Bantams had been constructed production was stopped when the A.B.C. Wasp was withdrawn as a production unit owing to persistent trouble with it. Armament of the Bantam was scheduled to be a pair of fuselage-mounted Vickers guns.

To distinguish it the Gnome version was referred to as the Bantam Mk.II, while the F.K.23, a smaller version, became the Bantam Mk.I. The Mk.I was bedevilled by dangerous spinning characteristics but the design’s speed and manoeuvrability resulted in an initial batch being ordered, with several alterations which went most of the way to eliminating the early faults. After nine Bantams had been constructed production was stopped when the A.B.C. Wasp was withdrawn as a production unit owing to persistent trouble with it. Armament of the Bantam was scheduled to be a pair of fuselage-mounted Vickers guns.

Frederick Koolhoven designed a further fighter for the B.A.T. Company to meet the R.A.F. Type 1 Specification, the F.K.25 Basilisk completed during 1918. The machine was another of those developed to use the power of the 320 h.p. A.B.C. Dragonfly radial engine and was on the general lines of the earlier Bantam but with the pilot given more conventional accommodation in a cockpit set further aft in the monocoque fuselage. Two-bay wings were again used and the undercarriage followed Koolhoven’s favourite style of separate units with a broad track. The Basilisk’s armament consisted of a pair of fuselage-mounted Vickers guns. The second prototype embodied minor modifications but the Basilisk failed to make any headway towards production.

Among the various types of aircraft produced by William Beardmore and Co. was a version of the Sopwith Pup redesigned for Beardmore by G. Tilghman Richards specifically for shipboard use. Saving of space has, from the beginning, always been a primary consideration for naval aircraft and, in the W.B.III, the wings were made to fold by eliminating the stagger and fitting a revised system of struts. To reduce height the main landing-gear folded up into the belly of the fuselage, the length of which had been increased. The S.B.3D designation was applied to the version with jettisonable undercarriage; S.B.3F denoted folding landing-gear. Production W.B.IIIs served with the Fleet and were armed with one Lewis gun on the upper centre-section.

Two other single-seat fighter designs, intended for the R.N.A.S., appeared from Beardmore in the course of 1917. The W.B.IV was a two-bay biplane designed around the 200 h.p. Hispano-Suiza, the engine being installed in the fuselage above the lower wings and driving its propeller by an extension shaft, which was straddled by the pilot in his high-set cockpit in the nose ahead of the leading edge of the wings. N38, the sole W.B.IV built, was notable also in having a streamlined flotation tank faired into the fore-fuselage and at first had floats under each wingtip. The machine carried two guns - a forwards-firing Vickers installed to port in the nose and a Lewis fitted at an upward angle in front of the pilot.

The Beardmore W.B.V single-seat fighter biplane also used the 200 h.p. Hispano-Suiza but was built specifically to make use of the 37 mm. Puteaux shell-gun which fired its rounds through the centre of the propeller shaft. In other respects the machine was of normal two-bay tractor layout but misapprehension concerning the safety of the pilot with the Puteaux in action led to the heavy gun’s replacement by one forwards-firing Vickers and upwards-firing Lewis gun. Interest in the W.B.V finally petered out and development stopped.

Contemporary with the A.D. Scout was the Blackburn Triplane, N502, which was designed late in 1915 and which exhibited several features in common with the A.D. machine. In particular, the Triplane possessed the same exaggerated gap between the tail booms which carried also the similar style of broad-span horizontal tail surfaces. The nacelle was mounted ahead of the centre wings of the single-bay cellules, and an undercarriage of normal height and track was provided. Additional ground stability was ensured by tip skids under the interplane struts.

The single forwards-firing gun was installed in the lower half of the nose of the nacelle, at the rear of which was fitted the 100 h.p. Monosoupape Gnome; the 110 h.p. Clerget was an alternative engine tested in the Triplane. Compared with the size of the fins, the rudders were large, and a fair measure of lateral control area was provided by fitting strut-connected ailerons on each of the six wingtips.

The single forwards-firing gun was installed in the lower half of the nose of the nacelle, at the rear of which was fitted the 100 h.p. Monosoupape Gnome; the 110 h.p. Clerget was an alternative engine tested in the Triplane. Compared with the size of the fins, the rudders were large, and a fair measure of lateral control area was provided by fitting strut-connected ailerons on each of the six wingtips.

In the North, the Blackburn Company started in 1917 to construct their N.1B single-seat, flying-boat fighter - also a pusher using the 200 h.p. Hispano-Suiza and of refined aerodynamic form. Progress was slow so that, when the end of the War came, only the hull was ready. Intended armament was a single Lewis gun in front of the pilot.

Yet another unsuccessful contender against the Snipe was the Boulton and Paul P.3 Bobolink, a single-seat biplane fighter which was completed in 1918. Designed by J. D. North, responsible for the design of several well-known pre-War Grahame-White machines, the Bobolink - originally named the Hawk by Boulton and Paul - was a competent product, based on the 230 h.p. Bentley B.R.2 engine and fitted with staggered two-bay wings employing the increasingly popular N-type interplane struts. The Bobolink was armed with the usual pair of fuselage-mounted Vickers guns and reached a top speed at 10,000 ft. of 125 m.p.h.

C8655, the Boulton and Paul P.3 Bobolink erected at Mousehold, in its original form, without ailerons on the lower wings (236 h.p. B.R.2 engine).

Meanwhile, also at Bristol, another single-seat scout had taken shape. During the previous year, Frank Barnwell, one of Coanda’s prominent fellow designers, started on a new design under works number 206 using parts of Coanda’s defunct monoplane S.B.5. Harry Busteed contributed to the design which evolved as a trim single-bay biplane with staggered wings and powered by a semi-cowled 80 h.p. Gnome. After its initial flight by Busteed at Larkhill on 23rd February, 1914, the Scout A was put on display at that year’s Olympia Aero Show. Immediately afterwards larger wings of 24 ft. 7 in. span were substituted for the original ones of 22 ft. During its A.I.D. tests with Busteed, on 14th May, the machine showed a top speed of 97 m.p.h. and a climb rate of 800 ft./min. but the prototype was lost in the English Channel on 11th July, 1914, while Lord Carbery was competing in the London-Paris-London race.

The Scout A had shown such promise that two modified versions were produced as Scouts B for the R.F.C. and were numbered 633 and 634. The Bristol Scouts A and B had been constructed on completely conventional lines with wire-braced box-girder fuselage, wooden structure throughout and fabric covering.

<...>

While the Sopwith company were developing the Tabloid for war, at Bristol a pair of new prototype scouts were being completed under Frank Barnwell’s direction, designated Scout B. Both were improved versions of the original Scout A which had been lost in the English Channel on 11th July, 1914. The new machines used the 80 h.p. Gnome engine and had double flying wires installed. Other differences included an undercarriage of broader track, a rudder of increased area, large skids added under the wings, and a full engine cowling with external ribs around its periphery, which had a similar appearance to the cowling fitted to Lord Carbery’s le Rhone engine in the Scout A.

The two Scouts B were sent to Farnborough on 21st and 23rd August respectively for their official tests, following which both were posted to France for use with the R.F.C. during the first week of September. On arrival one was added to the strength of No. 3 Squadron, where it was armed with a rifle mounted on each side of the fuselage at an angle of 45° to fire forward outside the propeller disc; the other Scout B went to No. 5 Squadron. Two months after the pair of Bristols made their appearance on the Western Front, a further twelve were ordered for the R.F.C. on 5th November, 1914.

Just over a month later, on 7th December, the Admiralty followed with an order for twenty-four to equip R.N.A.S. units. These production machines received the designation Scout C but were basically indistinguishable from the Scout B, apart from the new version’s revised engine cowling with its smooth outer surface and rather small frontal opening. The machines ordered for the R.F.C. were delivered in the following March, to be added singly or in pairs to reconnaissance units where their duty was to protect the two-seaters as they went about their dangerous observation duties over the opposing armies enmeshed in the struggle along the front line. The Bristol Scout C came on the scene before the idea had taken root of forming complete squadrons of scouts alone and so, for this reason, the type found itself spread in this way over the reconnaissance squadrons. Such a successful and reliable flying machine could well have been employed as the equipment of fighter squadrons if the concept of such formations had been realized earlier and had the machine been able, so early in the conflict, to take advantage of an interrupter or synchronous gun-firing gear.

The Scout A had shown such promise that two modified versions were produced as Scouts B for the R.F.C. and were numbered 633 and 634. The Bristol Scouts A and B had been constructed on completely conventional lines with wire-braced box-girder fuselage, wooden structure throughout and fabric covering.

<...>

While the Sopwith company were developing the Tabloid for war, at Bristol a pair of new prototype scouts were being completed under Frank Barnwell’s direction, designated Scout B. Both were improved versions of the original Scout A which had been lost in the English Channel on 11th July, 1914. The new machines used the 80 h.p. Gnome engine and had double flying wires installed. Other differences included an undercarriage of broader track, a rudder of increased area, large skids added under the wings, and a full engine cowling with external ribs around its periphery, which had a similar appearance to the cowling fitted to Lord Carbery’s le Rhone engine in the Scout A.

The two Scouts B were sent to Farnborough on 21st and 23rd August respectively for their official tests, following which both were posted to France for use with the R.F.C. during the first week of September. On arrival one was added to the strength of No. 3 Squadron, where it was armed with a rifle mounted on each side of the fuselage at an angle of 45° to fire forward outside the propeller disc; the other Scout B went to No. 5 Squadron. Two months after the pair of Bristols made their appearance on the Western Front, a further twelve were ordered for the R.F.C. on 5th November, 1914.

Just over a month later, on 7th December, the Admiralty followed with an order for twenty-four to equip R.N.A.S. units. These production machines received the designation Scout C but were basically indistinguishable from the Scout B, apart from the new version’s revised engine cowling with its smooth outer surface and rather small frontal opening. The machines ordered for the R.F.C. were delivered in the following March, to be added singly or in pairs to reconnaissance units where their duty was to protect the two-seaters as they went about their dangerous observation duties over the opposing armies enmeshed in the struggle along the front line. The Bristol Scout C came on the scene before the idea had taken root of forming complete squadrons of scouts alone and so, for this reason, the type found itself spread in this way over the reconnaissance squadrons. Such a successful and reliable flying machine could well have been employed as the equipment of fighter squadrons if the concept of such formations had been realized earlier and had the machine been able, so early in the conflict, to take advantage of an interrupter or synchronous gun-firing gear.

Although his S.B.5 had become a victim of the ban, Coanda still retained his enthusiasm for a military design and transferred his ideas to a two-seat gun-carrying pusher biplane layout which was constructed during 1913 as the Bristol P.B.8, works number 199. A compact machine of 27 ft. 6 in. span and length, it was powered by an 80 h.p. Gnome with the propeller revolving between the closely-set pairs of tail booms. The usual Coanda-style four-wheel landing-gear supported the P.B.8 but, although it was completed at Brooklands, it was not flown and had never been a popular project with the drawing office from the start. Coanda indulged in several other unusual designs for all-steel pushers in the midst of the general enthusiasm aroused for fitting a gun to an aeroplane but none of them progressed to the construction stage. In his search for a satisfactory layout to incorporate a gun, Coanda was forced to adhere to the pusher type of machine by the lack of any gear to ensure safe firing through a tractor propeller’s path.

In the West Country, at Bristol, Henri Coanda turned his hand to a design for the Breguet firm for a small biplane single-seat scout, the S.S.A. No. 219 which Harry Busteed flew and crashed at Filton early in 1914. The entire front portion of the machine’s fuselage was armoured by constructing it as a riveted sheet steel monocoque, automatically bringing forth the nickname of the Bath. A large spinner with an annular cooling slot faired the propeller into the engine cowling and skids extending to the rear of the wheels took the place of the usual single tailskid. Another advanced feature was the castoring of the wheels as an aid to crosswind landings. When the almost complete lack of ground clearance for the large propeller, then rather an obsession with Coanda, was pointed out to him by the drawing office staff, back came his usual answer “I don’t care, I make so!”.

Although neither the T.T.A. nor the S.2.A passed into production, Frank Barnwell’s next two-seat fighter design for the British and Colonial Aeroplane Company was destined to be an outstanding success and to have many years of excellent service ahead of it.

By the beginning of 1916, it had become quite obvious that a replacement was imperative for the primitive and obsolete two-seaters plodding their way warily across the increasingly dangerous skies over the Front. By March of that year, Barnwell was able to settle down to transferring to paper his idea of an advanced and powerful new two-seater. With a considerably enhanced fund of experience to draw upon, his versatile mind devised a layout for a biplane of eminently purposeful aspect.

At first the new project was known as the R.2A with the intended engine to be the 120 h.p. Beardmore. To obtain the desired performance it became obvious that more than 120 h.p. would be needed and thought was given to using the more powerful Hispano-Suiza as an alternative. Barnwell’s mind was finally made up for him by the advent at a most propitious time in April, 1916, of a newcomer to the range of Rolls-Royce aero engines - the twelve-cylinder water-cooled V Falcon of 205 h.p. Never satisfied that significantly increased output could not be gained by intensive development, Henry Royce was able steadily to improve the rating to 228 h.p. in May, 247 h.p. in February, 1917, and 262 h.p. by April, 1917.

The Falcon was a gift to Barnwell of a fine, reliable, powerful engine around which he proceeded to completely redesign the R.2A as the Bristol F.2A Fighter. The power unit was well blended into a fuselage of rectangular section which tapered in side elevation to a knife-edge at the tail, and which was suspended by struts between the two-bay, equal-span wings. In deference to the essential requirement in a two-seat fighter that the pilot and gunner should be able to communicate immediately with each other, the cockpits were adjacent and in every other way the needs of the crew for their utmost efficiency were borne in mind in the layout. The pilot’s view was enhanced by adequate stagger of the wings and by cut-outs in the centre-section trailing edge and roots, while the gunner was given as broad a field of fire as could be arranged.

Two prototypes were soon ordered but incorporating different engines - one with the Falcon Mk.l and the other with the 150 h.p. Hispano-Suiza. Work on the airframes was started during July, 1916, and 9th September saw the Falcon-powered A3303, the first machine, ready. Modification to the engine’s radiators soon took place when the pair originally fitted, one on each side of the fore-fuselage, were removed to improve the view for the pilot and replaced by a neat installation around the nose ahead of the engine. A3304, the Hispano-Suiza-powered F.2A, was complete some six weeks later on 25th October. The F.2A’s pilot was provided with a single Vickers gun installed in the centre of the nose and covered by the cowling so that it fired through an orifice in the radiator face. The observer’s Lewis was carried on a Scarff ring.

The F.2A was an instant success and went through its trials with flying colours to achieve performance figures which exceeded those expected. An initial order for fifty was placed, to be powered with the Falcon to circumvent the shortage of Hispano-Suizas, and with revised wingtips.

The first operational squadron to use the F.2A was No. 48, which went into action with the machine on 5th April, 1917, but suffered unexpectedly high losses immediately owing to the lack of appreciation by the crews of the vastly superior capabilities of their mounts compared with previous two-seaters. Once the speed and great manoeuvrability inherent in the Fighter were recognized, the machine came into its own in combat with the pilot able to use his gun really effectively and the observer simultaneously making the most of his armament. The technique which had to be learned and exploited was one of flying and fighting with the machine in a manner hitherto reserved for a single-seater.

Even after the deletion of the side radiators, the forward view from the pilot’s cockpit was still not all that it could be and was improved by incorporating downward slope in the upper longerons from the rear cockpit forward to the bearers for the engine. The modified machine went into production as the F.2B and proceeded to enhance the reputation already earned by the F.2A.

The Biff, as it soon became affectionately known, proved itself to be a brilliant design and an outstanding success among the British warplanes of 1914-18.

Although the Sopwith 1 1/2-Strutter had pioneered the two-seat armed tractor layout successfully, Frank Barnwell’s Bristol Fighter marks the start of the classic concept and employment in battle of the single-engine, two-seat, high-performance fighter, born in the heat of war and continued into the years of peace as a type of aircraft in the development of which British designers excelled. Provided that sufficient power were available from the engine, around which the machine was designed, the two-seat fighter could prove itself to be a very welcome and useful addition to air strength. The twin-engine multi-seat concept for a fighter was a far less happy combination owing to the attendant drastic sacrifice of manoeuvrability, which its size and layout involved, and which was not a pronounced feature of the single-engine formula. Some loss of performance was inevitable in the two-seat fighter, owing to increased size and the extra weight of airframe and gunner, but the Bristol Fighter was able to offset these disadvantages handsomely by virtue of its excellent, powerful Rolls-Royce engine.

By the beginning of 1916, it had become quite obvious that a replacement was imperative for the primitive and obsolete two-seaters plodding their way warily across the increasingly dangerous skies over the Front. By March of that year, Barnwell was able to settle down to transferring to paper his idea of an advanced and powerful new two-seater. With a considerably enhanced fund of experience to draw upon, his versatile mind devised a layout for a biplane of eminently purposeful aspect.

At first the new project was known as the R.2A with the intended engine to be the 120 h.p. Beardmore. To obtain the desired performance it became obvious that more than 120 h.p. would be needed and thought was given to using the more powerful Hispano-Suiza as an alternative. Barnwell’s mind was finally made up for him by the advent at a most propitious time in April, 1916, of a newcomer to the range of Rolls-Royce aero engines - the twelve-cylinder water-cooled V Falcon of 205 h.p. Never satisfied that significantly increased output could not be gained by intensive development, Henry Royce was able steadily to improve the rating to 228 h.p. in May, 247 h.p. in February, 1917, and 262 h.p. by April, 1917.

The Falcon was a gift to Barnwell of a fine, reliable, powerful engine around which he proceeded to completely redesign the R.2A as the Bristol F.2A Fighter. The power unit was well blended into a fuselage of rectangular section which tapered in side elevation to a knife-edge at the tail, and which was suspended by struts between the two-bay, equal-span wings. In deference to the essential requirement in a two-seat fighter that the pilot and gunner should be able to communicate immediately with each other, the cockpits were adjacent and in every other way the needs of the crew for their utmost efficiency were borne in mind in the layout. The pilot’s view was enhanced by adequate stagger of the wings and by cut-outs in the centre-section trailing edge and roots, while the gunner was given as broad a field of fire as could be arranged.

Two prototypes were soon ordered but incorporating different engines - one with the Falcon Mk.l and the other with the 150 h.p. Hispano-Suiza. Work on the airframes was started during July, 1916, and 9th September saw the Falcon-powered A3303, the first machine, ready. Modification to the engine’s radiators soon took place when the pair originally fitted, one on each side of the fore-fuselage, were removed to improve the view for the pilot and replaced by a neat installation around the nose ahead of the engine. A3304, the Hispano-Suiza-powered F.2A, was complete some six weeks later on 25th October. The F.2A’s pilot was provided with a single Vickers gun installed in the centre of the nose and covered by the cowling so that it fired through an orifice in the radiator face. The observer’s Lewis was carried on a Scarff ring.

The F.2A was an instant success and went through its trials with flying colours to achieve performance figures which exceeded those expected. An initial order for fifty was placed, to be powered with the Falcon to circumvent the shortage of Hispano-Suizas, and with revised wingtips.

The first operational squadron to use the F.2A was No. 48, which went into action with the machine on 5th April, 1917, but suffered unexpectedly high losses immediately owing to the lack of appreciation by the crews of the vastly superior capabilities of their mounts compared with previous two-seaters. Once the speed and great manoeuvrability inherent in the Fighter were recognized, the machine came into its own in combat with the pilot able to use his gun really effectively and the observer simultaneously making the most of his armament. The technique which had to be learned and exploited was one of flying and fighting with the machine in a manner hitherto reserved for a single-seater.

Even after the deletion of the side radiators, the forward view from the pilot’s cockpit was still not all that it could be and was improved by incorporating downward slope in the upper longerons from the rear cockpit forward to the bearers for the engine. The modified machine went into production as the F.2B and proceeded to enhance the reputation already earned by the F.2A.

The Biff, as it soon became affectionately known, proved itself to be a brilliant design and an outstanding success among the British warplanes of 1914-18.

Although the Sopwith 1 1/2-Strutter had pioneered the two-seat armed tractor layout successfully, Frank Barnwell’s Bristol Fighter marks the start of the classic concept and employment in battle of the single-engine, two-seat, high-performance fighter, born in the heat of war and continued into the years of peace as a type of aircraft in the development of which British designers excelled. Provided that sufficient power were available from the engine, around which the machine was designed, the two-seat fighter could prove itself to be a very welcome and useful addition to air strength. The twin-engine multi-seat concept for a fighter was a far less happy combination owing to the attendant drastic sacrifice of manoeuvrability, which its size and layout involved, and which was not a pronounced feature of the single-engine formula. Some loss of performance was inevitable in the two-seat fighter, owing to increased size and the extra weight of airframe and gunner, but the Bristol Fighter was able to offset these disadvantages handsomely by virtue of its excellent, powerful Rolls-Royce engine.

In contrast with the situation prevailing in Britain, the monoplane had thrived on the Continent as a military machine in both France and Germany. The type had consequently received its full share of attention to development and both countries possessed a fairly useful range of monoplanes in service. By comparison, progressive experience in the design and construction of monoplanes in Great Britain had suffered severely as a direct result of the ban of 1912 and the consequent concentration, to its virtual exclusion, on biplanes, triplanes and even quadruplanes.

The advent of the Bristol M.1A single-seat monoplane fighter in September, 1916, was therefore an event of some considerable significance as Frank Barnwell had been given sanction by the British and Colonial Aeroplane Company to design it during July, 1916, despite continued official disapproval of the form for Service equipment. Such short-sighted behaviour in official circles, exhibited in various forms on many occasions, militates directly against accumulation of invaluable experience in design, construction and operation which those striving in all good faith on behalf of their country are entitled to acquire for its protection and continued well-being. Anything less than whole-hearted encouragement and assistance to those whose direct responsibility is the strength of the armed forces for the shielding of the population, is playing straight into the hands of the country’s enemies and is a scandalous denial to its brave sons of the quality of equipment which they have every right to expect to be provided for them.

The monoplane ban of 1912 meant the loss of several years of steady development which Great Britain could ill afford, particularly since her traditional protection of the water surrounding her had been shown three years earlier as being no longer her complete safeguard. She could now be attacked by air from the Continent and consequently needed to exploit every conceivable means for her protection. The banning of a particular class of fast aeroplane was certainly no way of furthering this object and even the Bristol Monoplane in Barnwell’s advanced style was unable to make much headway against the opposition, a resistance which was to face the monoplane until the mid-1930s.

The 110 h.p. Clerget powered the M.1A and the designer aimed at achieving as streamlined an installation as possible by employing a spinner with a large diameter, leaving a cooling slot between itself and the cowling. A simple rectangular-section wooden basic fuselage was faired to circular form with the usual arrangement of formers and stringers. The wings were mounted in the shoulder position and braced by wires from a central cabane over the cockpit.

Construction of the prototype A5138 was so quick that it was ready in September, 1916, for testing by Freddy Raynham. The machine’s top speed was a rewarding 132 m.p.h. and a further four examples were constructed as M.1Bs with slight modifications and armed with a single synchronized Vickers gun on the port decking.

News of the new fast and handy monoplane fighter, which soon circulated among squadron pilots, raised high hopes and anticipation of its appearance in France. Such was not to be, however, and the landing speed of 49 m.p.h. was stated to be too high in justification of the rejection for use on the Western Front. One hundred and twenty-five were, nevertheless, ordered into production as the M.1C using the 110 h.p. le Rhone and having the gun mounted centrally and synchronized by the Constantinesco gear. The M.1C did manage to see operational service in the Middle East but its denial to the pilots of the Western Front stands out as one of the worst examples of official incompetence and ineptitude extant. The issue in quantity of the M.1C to the R.F.C. in France could have wrought a great change in the Allies’ favour in the fighting in the skies.

The advent of the Bristol M.1A single-seat monoplane fighter in September, 1916, was therefore an event of some considerable significance as Frank Barnwell had been given sanction by the British and Colonial Aeroplane Company to design it during July, 1916, despite continued official disapproval of the form for Service equipment. Such short-sighted behaviour in official circles, exhibited in various forms on many occasions, militates directly against accumulation of invaluable experience in design, construction and operation which those striving in all good faith on behalf of their country are entitled to acquire for its protection and continued well-being. Anything less than whole-hearted encouragement and assistance to those whose direct responsibility is the strength of the armed forces for the shielding of the population, is playing straight into the hands of the country’s enemies and is a scandalous denial to its brave sons of the quality of equipment which they have every right to expect to be provided for them.

The monoplane ban of 1912 meant the loss of several years of steady development which Great Britain could ill afford, particularly since her traditional protection of the water surrounding her had been shown three years earlier as being no longer her complete safeguard. She could now be attacked by air from the Continent and consequently needed to exploit every conceivable means for her protection. The banning of a particular class of fast aeroplane was certainly no way of furthering this object and even the Bristol Monoplane in Barnwell’s advanced style was unable to make much headway against the opposition, a resistance which was to face the monoplane until the mid-1930s.

The 110 h.p. Clerget powered the M.1A and the designer aimed at achieving as streamlined an installation as possible by employing a spinner with a large diameter, leaving a cooling slot between itself and the cowling. A simple rectangular-section wooden basic fuselage was faired to circular form with the usual arrangement of formers and stringers. The wings were mounted in the shoulder position and braced by wires from a central cabane over the cockpit.

Construction of the prototype A5138 was so quick that it was ready in September, 1916, for testing by Freddy Raynham. The machine’s top speed was a rewarding 132 m.p.h. and a further four examples were constructed as M.1Bs with slight modifications and armed with a single synchronized Vickers gun on the port decking.

News of the new fast and handy monoplane fighter, which soon circulated among squadron pilots, raised high hopes and anticipation of its appearance in France. Such was not to be, however, and the landing speed of 49 m.p.h. was stated to be too high in justification of the rejection for use on the Western Front. One hundred and twenty-five were, nevertheless, ordered into production as the M.1C using the 110 h.p. le Rhone and having the gun mounted centrally and synchronized by the Constantinesco gear. The M.1C did manage to see operational service in the Middle East but its denial to the pilots of the Western Front stands out as one of the worst examples of official incompetence and ineptitude extant. The issue in quantity of the M.1C to the R.F.C. in France could have wrought a great change in the Allies’ favour in the fighting in the skies.

While the T.T.A. was undergoing its trials, a completely different concept of a two-seat scout made its debut - the Bristol S.2A. A single-engine biplane with pilot and gunner seated side-by-side, it was inspired by the Scout D but, as a reliable synchronizer for a forward-firing gun was still awaited, the expedient of carrying a gunner alongside the pilot was adopted in the interest of keeping down the overall size of the aeroplane. The 110 h.p. Clerget provided the power initially in 7836 and 7837, the pair of prototypes. By the time that they were ready, one during May and the other during June of 1916, fairly adequate synchronizing gears were ready and the temporary solution provided by the S.2A was not required. Its performance was commendable and one of the two S.2As was modified for further trials with the lower power of the 100 h.p. Monosoupape Gnome.

In the course of September, 1915, design work had been initiated on an ambitious two-seat fighter biplane to be powered by twin engines and designated Bristol T.T. - Twin Tractor. Responsible for the project’s layout were F. S. Barnwell and L. G. Frise and in its general concept, together with the gunner in the nose and the pilot located behind the wings, the T.T. resembled the Vickers F.B.7 and F.B.8. The machine was of 53 ft. 6 in. span and was scheduled to employ a pair of 150 h.p. R.A.F.4a engines. Non-availability of these units forced the installation of two 120 h.p. Beardmores, the revision resulting in a new designation T.T.A. Two Lewis guns armed the front gunner and a third Lewis was installed for the pilot to fire to the rear. The T.T.A. was ready for its initial trials in May, 1916, and these were carried out by Capt. Hooper of the R.F.C.

Like the two Vickers products, the Bristol T.T.A. lacked the primary requisites of a fighter and was too ponderous and low-powered to possess sufficient manoeuvrability, besides denying the pilot and gunner the quick communication between them which was so essential in a fighter. There was also negligible prospect of being able to fire the guns to the rear, which left the machine defenceless from that quarter; consequently, the pair of prototypes - 7750 and 7751 - were abandoned.

<...>

The F.K.11 was not proceeded with but another design from Armstrong Whitworth, the three-seat F.K.5, also exhibited some equally remarkable features. It was built as the result of a War Office requirement for a multi-seat, long-range escort and anti-Zeppelin fighter, a specification to which Vickers and Sopwith also constructed prototypes.

The Bristol F.3A, a development of the T.T.A., using its aft fuselage, biplane wings and tailplane and the 250 h.p. Rolls-Royce Mk.I for power, was proposed to the same requirement but was abandoned. To give the F.3A’s gunners unrestricted field of fire, they were going to be installed in a pair of cockpits incorporated in the upper wings.

Like the two Vickers products, the Bristol T.T.A. lacked the primary requisites of a fighter and was too ponderous and low-powered to possess sufficient manoeuvrability, besides denying the pilot and gunner the quick communication between them which was so essential in a fighter. There was also negligible prospect of being able to fire the guns to the rear, which left the machine defenceless from that quarter; consequently, the pair of prototypes - 7750 and 7751 - were abandoned.

<...>

The F.K.11 was not proceeded with but another design from Armstrong Whitworth, the three-seat F.K.5, also exhibited some equally remarkable features. It was built as the result of a War Office requirement for a multi-seat, long-range escort and anti-Zeppelin fighter, a specification to which Vickers and Sopwith also constructed prototypes.

The Bristol F.3A, a development of the T.T.A., using its aft fuselage, biplane wings and tailplane and the 250 h.p. Rolls-Royce Mk.I for power, was proposed to the same requirement but was abandoned. To give the F.3A’s gunners unrestricted field of fire, they were going to be installed in a pair of cockpits incorporated in the upper wings.

Two prototypes of an all-metal, two-seat fighter, designated M.R.1 and intended to eliminate the disadvantages attendant upon the usual wooden airframes under tropical conditions, were constructed following Barnwell’s basic layout for the project during July, 1916, with the detail design work undertaken by W. T. Reid. The engine chosen was the 150 h.p. Hispano- Suiza, the airframe that it powered being a two-bay biplane which was slightly larger overall than the F.2A and F.2B. The fuselage was mounted mid-way in the gap between the wings and was a stressed-skin monocoque covered with sheet aluminium. The pilot was provided with a single Vickers gun in the cowling while the gunner had a Lewis gun on a Scarff ring. Although tested comprehensively, the M.R.1 was not selected finally for production but is of note for its use of metal for the framework and the fuselage covering.

During the Summer of 1917 Bristol’s designer Frank Barnwell set to work on the design of a new single-seat fighter, the Scout F, to use the water-cooled 200 h.p. Sunbeam Arab II engine. The Scout F materialized as a single-bay biplane with N-type interplane struts and a very clean engine installation which was assisted materially by the location of the radiator between the undercarriage legs. Tests revealed excellent overall performance and flying characteristics bqt the Arab power plant persisted in giving trouble.

Of the three Scout Fs constructed the third, B3991, was fitted with one of the new radial engines then beginning to appear. This was the 347 h.p. Cosmos Mercury with which B3991, redesignated Scout F.1, made its initial flight during April, 1918. The engine was installed to blend neatly into the F.1’s nose and, with it, the machine turned in a first-class performance, carrying armament of two Vickers guns on the front decking but development of the Scout F.1 was eventually halted.

Of the three Scout Fs constructed the third, B3991, was fitted with one of the new radial engines then beginning to appear. This was the 347 h.p. Cosmos Mercury with which B3991, redesignated Scout F.1, made its initial flight during April, 1918. The engine was installed to blend neatly into the F.1’s nose and, with it, the machine turned in a first-class performance, carrying armament of two Vickers guns on the front decking but development of the Scout F.1 was eventually halted.

As the War’s last days drew nearer Bristol’s F. S. Barnwell proceeded with his design for a two-seat fighter to take over from the F.2B. His first approach to a successor was started in November, 1917, as the F.2C with three alternative engines - the 230 h.p. Bentley B.R.2 rotary, the 260 h.p. Salmson radial and, finally, the 320 h.p. A.B.C. Dragonfly 1 - considered as the power unit. The Dragonfly was selected for the Badger Mk.I, as the F.2C was eventually named, and the prototype, F3495, was taken into the air for the first time on 4th February, 1919, by Capt. C. F. Uwins but crashed when the engine stopped suddenly owing to the failure of the petrol supply. The second Badger constructed, designated Mk.II, used the 450 h.p. Cosmos Jupiter radial with its greater power and reliability. The Badger was characterized by its single-bay, staggered, sweptback wings with their N-style interplane struts, and was armed with twin Vickers guns for the pilot and a Lewis for the observer. Three prototypes were built but no production ensued.

During 1910 there occurred one of those chance meetings which may sometimes have such far-reaching effects. F. M. Green engaged in conversation with Geoffrey de Havilland who, after having crashed his first aeroplane early in its tests, had constructed another and taught himself to fly on it. De Havilland told Green that, as the financial resources which he had had for pursuing his flying experiments were all but exhausted, it looked as though he might have to terminate such work. At Green’s suggestion, de Havilland applied to the Balloon Factory for a post as designer and test pilot. The outcome was that in December, 1910, he and his friend and assistant, F. T. Hearle, joined the staff of the Factory, taking with them to Farnborough the biplane for which the War Office paid £400. Although at the time it was evident neither to the authorities nor to de Havilland, in this way was the pioneer constructor enabled to carry on his work to such outstanding advantage in later years to the country, and to give immediate impetus to heavier-than-air development at the Factory by delivering to it a reasonably practical aeroplane. The Factory was so enamoured of its new acquisition that it bestowed on it the honour of the first official designation F.E.1.

In design and execution de Havilland’s machine was, without exception, typical of the aeroplanes of the period. The layout was that of the successful Farman-style two-bay biplane with stabilizing and control surfaces carried on four booms fore and aft of the wings. The pilot’s position was the logical one on the leading edge of the lower wings, with the engine and its pusher propeller mounted behind him. Two main wheels and a tailskid formed the landing-gear and ailerons gave the machine its lateral control. The engine was the 45 h.p. unit which had been made to de Havilland’s design by the Iris Motor Company at Willesden. The entire framework of the biplane was of wood, the material resorted to by most of the constructors at the time. Its great virtue was that it was easily worked, without the necessity on the part of the impecunious flyers for any outlay on expensive tools or machines. Besides, wood was strong and cheap and easily repaired after the all-too-frequent mishaps which attended the attempts to stagger off the ground. The structure was braced with tensioned wire and covered with fabric.

In design and execution de Havilland’s machine was, without exception, typical of the aeroplanes of the period. The layout was that of the successful Farman-style two-bay biplane with stabilizing and control surfaces carried on four booms fore and aft of the wings. The pilot’s position was the logical one on the leading edge of the lower wings, with the engine and its pusher propeller mounted behind him. Two main wheels and a tailskid formed the landing-gear and ailerons gave the machine its lateral control. The engine was the 45 h.p. unit which had been made to de Havilland’s design by the Iris Motor Company at Willesden. The entire framework of the biplane was of wood, the material resorted to by most of the constructors at the time. Its great virtue was that it was easily worked, without the necessity on the part of the impecunious flyers for any outlay on expensive tools or machines. Besides, wood was strong and cheap and easily repaired after the all-too-frequent mishaps which attended the attempts to stagger off the ground. The structure was braced with tensioned wire and covered with fabric.

Two months before the start of the War, the Royal Aircraft Factory parted with one of its most experienced and talented designers when Geoffrey de Havilland left in June, 1914, to work in the civilian industry by joining the design staff of the Aircraft Manufacturing Company at Hendon. Since being founded in 1912, Airco had been making aircraft which were not of its own design but its head, George Holt Thomas, was keen on setting up a design office so that the firm could establish itself as a company manufacturing its own designs.

De Havilland’s first type for his new employers was to be a reconnaissance and fighting machine, perforce a biplane, and his success with the tractor B.E. series and the B.S.1 at Farnborough encouraged him to adhere to the same layout. The general form was evolving on the drawing board when it was realized by the War Office that there was still no practical means of firing a gun ahead through the propeller. Proposals for solving this problem had been submitted to the War Office by the Edwards brothers but had come to naught. The request was made that the tractor project should be abandoned and that a pusher layout be substituted.

The revised machine was to be designed around the air-cooled 70 h.p. Renault V-8 engine and was to carry a front gunner in addition to the pilot. Although the new machine was by no means de Havilland’s first essay in design, it was designated D.H.1 and this and his succeeding types for the same company continued to be known by their designer’s initials, the name Airco being rarely applied as well.

The D.H.1 exhibited a marked overall resemblance to the F.E.2 but was slightly smaller and heavier. One or two features of note were incorporated in an otherwise conventional two-bay pusher layout. These included a landing-gear embodying coil springs and oleo tubes for shock-absorbing, and a pair of aerofoil surfaces - some 3 ft. in span each - mounted on each side of the nacelle between the centre-section struts to act as airbrakes.

On completion in January, 1915, de Havilland carried out the tests of the D.H.1 at Hendon. Its performance was reasonably good, although the Renault’s 70 h.p. was considerably lower than the 120 h.p. of the Beardmore which Airco had hoped would become available for it. Negligible effect was produced by turning the airbrakes through their 90° angle across the slipstream and drag was lessened when they were subsequently removed. The D.H.1 was forced to wait some time for its Beardmore engine as the few available went to the Royal Aircraft Factory. A number were built powered by the Renault and were fitted with cut-down sides to the gunner’s cockpit and undercarriages which reverted to rubber-cord springing. The production version built at King’s Lynn by Savages was designated D.H.1A, and benefited from the power of the Beardmore, the radiator of which was installed prominently immediately behind the pilot’s head. The gunner’s armament was a single Lewis gun on a pillar mounting in the nose, from which he had an excellent field of fire, and on some examples a Lewis gun was fitted for the pilot to fire over the gunner. In spite of its useful attributes, the D.H.1 never really got into its stride as a weapon of war as the F.E.2 was already well developed and the seventy-three D.H.1s and D.H.1As constructed were distributed mainly among Home Defence and training units, six of them finding their way out to the Middle East in 1916.

De Havilland’s first type for his new employers was to be a reconnaissance and fighting machine, perforce a biplane, and his success with the tractor B.E. series and the B.S.1 at Farnborough encouraged him to adhere to the same layout. The general form was evolving on the drawing board when it was realized by the War Office that there was still no practical means of firing a gun ahead through the propeller. Proposals for solving this problem had been submitted to the War Office by the Edwards brothers but had come to naught. The request was made that the tractor project should be abandoned and that a pusher layout be substituted.

The revised machine was to be designed around the air-cooled 70 h.p. Renault V-8 engine and was to carry a front gunner in addition to the pilot. Although the new machine was by no means de Havilland’s first essay in design, it was designated D.H.1 and this and his succeeding types for the same company continued to be known by their designer’s initials, the name Airco being rarely applied as well.

The D.H.1 exhibited a marked overall resemblance to the F.E.2 but was slightly smaller and heavier. One or two features of note were incorporated in an otherwise conventional two-bay pusher layout. These included a landing-gear embodying coil springs and oleo tubes for shock-absorbing, and a pair of aerofoil surfaces - some 3 ft. in span each - mounted on each side of the nacelle between the centre-section struts to act as airbrakes.

On completion in January, 1915, de Havilland carried out the tests of the D.H.1 at Hendon. Its performance was reasonably good, although the Renault’s 70 h.p. was considerably lower than the 120 h.p. of the Beardmore which Airco had hoped would become available for it. Negligible effect was produced by turning the airbrakes through their 90° angle across the slipstream and drag was lessened when they were subsequently removed. The D.H.1 was forced to wait some time for its Beardmore engine as the few available went to the Royal Aircraft Factory. A number were built powered by the Renault and were fitted with cut-down sides to the gunner’s cockpit and undercarriages which reverted to rubber-cord springing. The production version built at King’s Lynn by Savages was designated D.H.1A, and benefited from the power of the Beardmore, the radiator of which was installed prominently immediately behind the pilot’s head. The gunner’s armament was a single Lewis gun on a pillar mounting in the nose, from which he had an excellent field of fire, and on some examples a Lewis gun was fitted for the pilot to fire over the gunner. In spite of its useful attributes, the D.H.1 never really got into its stride as a weapon of war as the F.E.2 was already well developed and the seventy-three D.H.1s and D.H.1As constructed were distributed mainly among Home Defence and training units, six of them finding their way out to the Middle East in 1916.

While aerial activity over the Western Front steadily increased during the first half of 1915, in the Airco design office Geoffrey de Havilland was committing to the drawing-boards his concept of a single-seat armed scout of pusher layout, destined to be basically a smaller version of the D.H.1. Designated D.H.2 the machine was one of the cleanest and among the best-looking of pusher designs. The two-bay wing formula was adhered to, with the pilot seated well forward in the nacelle to command an excellent view in every direction. The 100 h.p. Monosoupape Gnome was chosen to power the D.H.2 which made its first flight in July, 1915.

The sole object of designing the new pusher was to produce an effective fighting scout, the armament of which was a single Lewis gun pivoting on a mounting at the side of the cockpit. The intention was that the pilot should aim the gun by hand as needed, but production D.H.2s had the gun fixed in a central trough in the upper coaming of the nacelle, a location which assisted the clearance of possible stoppages. Construction was of wood throughout with the exception of the steel-tubing booms carrying the tail unit.

In keeping with the machine’s intended role as a fighter, the performance was brisk and the generous control surfaces gave the D.H.2 great sensitivity, a quality which was extremely useful but which required careful handling and constant attention by the pilot. Among the hazards to be guarded against were unexpected spins and the catastrophic possibility of the rotary’s cylinders parting company with the crankcase and cutting through the tailbooms.

The D.H.2’s great distinction is that it formed the equipment of the R.F.C.’s first single-seat fighter squadron, No. 24, a unit which arrived in France on 7th February, 1916, to be followed shortly by Nos. 29 and 32. The new fighter proved to be exceedingly useful and successful, doing great work in action for the two years following its introduction. Of four hundred D.H.2s produced, most used the standard engine but the 110 h.p. le Rhone also was employed as an alternative power plant.

The sole object of designing the new pusher was to produce an effective fighting scout, the armament of which was a single Lewis gun pivoting on a mounting at the side of the cockpit. The intention was that the pilot should aim the gun by hand as needed, but production D.H.2s had the gun fixed in a central trough in the upper coaming of the nacelle, a location which assisted the clearance of possible stoppages. Construction was of wood throughout with the exception of the steel-tubing booms carrying the tail unit.

In keeping with the machine’s intended role as a fighter, the performance was brisk and the generous control surfaces gave the D.H.2 great sensitivity, a quality which was extremely useful but which required careful handling and constant attention by the pilot. Among the hazards to be guarded against were unexpected spins and the catastrophic possibility of the rotary’s cylinders parting company with the crankcase and cutting through the tailbooms.

The D.H.2’s great distinction is that it formed the equipment of the R.F.C.’s first single-seat fighter squadron, No. 24, a unit which arrived in France on 7th February, 1916, to be followed shortly by Nos. 29 and 32. The new fighter proved to be exceedingly useful and successful, doing great work in action for the two years following its introduction. Of four hundred D.H.2s produced, most used the standard engine but the 110 h.p. le Rhone also was employed as an alternative power plant.

An out-of-the-ordinary concept which did achieve fair success was Geoffrey de Havilland’s little D.H.5 single-seat biplane of 1916, unusual in that it incorporated back-stagger in pursuit of that much-sought-after feature of a fighter - a first class view for the pilot.

Designed around the 110 h.p. le Rhone, the D.H.5 was in every other respect quite conventional in layout and construction. Unfortunately, performance at height was not a strong point with the type so, because of this fault, employment was found for it mainly in ground attack in which role the excellent forward view was a great asset.

Designed around the 110 h.p. le Rhone, the D.H.5 was in every other respect quite conventional in layout and construction. Unfortunately, performance at height was not a strong point with the type so, because of this fault, employment was found for it mainly in ground attack in which role the excellent forward view was a great asset.

In the Autumn of 1916 there appeared the first aeroplane to be both designed and constructed by the Fairey Aviation Company. Hitherto, the firm had built some Short-designed seaplanes but, with the F.2 three-seat, long-range fighter, it started the extensive line of aircraft which were to carry the name of Fairey for the ensuing forty years. The F.2 was intended for the R.N.A.S. and was a three-bay tractor biplane with a span of 77 ft. and a pair of 190 h.p. Rolls-Royce Falcon engines. Both gunners had Lewis guns on Scarff rings, one being in the nose cockpit and the other just aft of the wings.

Although, when it flew in May, 1917, the single prototype 3704 showed the F.2 to be a competent enough design, it proved to be another of the early examples of that class of the large, multi-seat, multi-engine fighter which, owing to its inherent disadvantages, was to prove time and time again unsuitable for adoption and production.

Although, when it flew in May, 1917, the single prototype 3704 showed the F.2 to be a competent enough design, it proved to be another of the early examples of that class of the large, multi-seat, multi-engine fighter which, owing to its inherent disadvantages, was to prove time and time again unsuitable for adoption and production.

J. D. North, designer to Claude Grahame-White’s concern at Hendon, tried his hand at a gun-carrier with the Type 6 Military Biplane which was ready in time for display at the 1913 Aero Show at Olympia. Designed on comparatively unorthodox lines, the machine was fitted with an Austro-Daimler engine mounted in the nose of the deep nacelle. The crankshaft was extended rearwards the length of the nacelle, where it was connected to the two-blade propeller by a chain drive. The propeller itself revolved around the upper tubular tail-boom which acted also as its bearing. This feature was reminiscent of the arrangement adopted in the Royal Aircraft Factory’s F.E.3 but the Type 6’s tail had the benefit of additional support from a pair of lower booms making in all a rigidly-braced triangular framework. The bore of the uppermost boom was used to carry the control wires to the rudder and elevators. Centre-section struts were omitted, the upper wings being carried across the nacelle by the inner interplane struts. Twin pairs of main wheels were suspended in slots in ski-shaped skids, and the nacelle carried two passengers on the sprung tops of the tool boxes on each side of the engine, the pilot being accommodated behind them. The Type 6’s single machine-gun was a Colt installed in the nose with 50 vertical and 180 horizontal field of fire.