Книги

Osprey

H.Cowin

Aviation Pioneers

185

H.Cowin - Aviation Pioneers /Osprey/

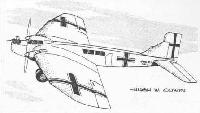

Авиатик (Берг) серии 238, пилот Линке Кроуфорд, 1918г / Design of the Austrian Aviatik, or Berg D I commenced very early in 1917, slightly ahead of Austria's other indigenous fighter, the Phonix D I. During the early stage of its flying career, the Berg D I suffered catastrophic structural wing failure, but once generally 'beefed-up', the machine proved to be both fast, agile and have a good climb, cited as reaching 13,000 feet in 11 minutes 15 seconds. Initially powered by a 185hp Austro-Daimler, these Bergs had top level speed of 113mph at sea level. The speed of later 200hp or 225hp powered aircraft rose to 115mph. Similarly, initial production Bergs carried a single 8mm Schwarzlose, while a second was added to later fighters. Delivered primarily to serve on the Italian Front from the late spring of 1917 onwards, the Berg D I was built in some quantities, involving 4 sub-contractors probably producing more than 300 machines. The fighter shown here was the mount of Austrian air ace, Oblt Frank Linke-Crawford, leader of Flik 60.

Front aspect of the intriguing sole Austrian Aviatik G II completed in July 1917. The brainchild of Prof von Mises, the 3-man bomber had its twin 300hp Austro-Daimlers buried in the fuselage to drive tandem-arranged tractor and pusher propellers mounted inboard between the wings.

The Etrich Taube two seater of Austrian origin first flew in November 1909 and was adopted by the German military in 1911 as their standard reconaissance and training type. Most were built under licence in Germany by Rumpler. They were withdrawn from front line service by mid-1915. This is a 1912 Taube fitted with a 100hp Daimler D.I, giving a top level speed of 7l mph.

A Lloyd C II of the Austro-Hungarian forces operating at the southern end of the Eastern Front in 1916. Seen here being re-assembled after being rail freighted to the front, little more information concerning the aircraft's, crew's or unit identity survives. However, photographs reveal that shortly after this image was taken, the machine nosed-over during the subsequent attempted take-off.

The Lohner Type L two seater reconnaissance/bomber flying boat was used to real effect by the Austro-Hungarian Navy during the 1915-1916 period. Based on Jakob Lohner's 1913 Type E, the Type L was powered by various engines rated between 140hp and 180hp, giving the machine a top level speed of around 65mph. Thanks to its wing design, the Type L showed an impressive high altitude capability, having a ceiling of about 16,400 feet. Around 160 Type Ls were built, but such was their operational success that the machine was copied by Macchi in Italy, leading to the Macchi M.3 through M.9 series.

Lohner of Austria, besides producing their admirable line of small, agile flying boats, also built a series of land-based, reconnaissance two-seaters for the Austro-Hungarian Air Service. In stark contrast to their flying boats, these B and C class designs, spanning the years 1913 to 1917, proved mediocre performers and, in consequence, each variant was only built in small numbers. The 1915 Lohner B.VII, 17.00, seen here, despite its 160hp Austro-Daimler, could only achieve a top level speed of 85 mph at sea level. As in this case, despite their B class designations, many two seaters were retrospectively fitted with a gun in the rear seat, thus converting them, effectively, into C types.

The Armstrong Whitworth FK 8 was a contemporary of the Royal Aircraft Factory's RE 8, being generally considered as the better of the pair. First flown in May 1916, the two-seat FK 8 reconnaissance bomber was initially powered by a 120hp Beardmore, soon replaced by its larger 160hp brother. Top level speed of the FK 8 was 98.4mph at sea level, decreasing to 88mph at 10,000 feet. Besides the standard .303-inch Vickers and Lewis gun combination, the FK 8 could haul a bomb load of up to 160lb. The type made its operational debut with No 35 Squadron, RFC, on 24 January 1917, with deliveries flowing to another four French-based RFC squadrons, two in the Balkans, one in Palestine and to home defence units. Two pilots were to win the Victoria Cross flying the FK 8, while an FK 8 of Kent-based No 50 Squadron, RFC, is credited with downing a Gotha off the North Foreland on 7 July 1917. Some 1.000 or so FK 8s had been built when production ended in July 1918.

Edwin Alliot Verdon Roe, seen here standing beside his Roe III two-seat triplane of 1910, was born near Manchester on 26 April 1877. 'AV' Showed an early aptitude for the more technical subjects, cemented by serving a five year apprenticeship at a railway works between 1893 and 1898. Next, 'A.V.' turned to things maritime, hoping to join the Royal Navy, but ending up by spending four years in the merchant marine. It was while at sea that 'A.V.' started to study bird flight, which by 1902 had led him into aeromodelling. 'A.V.'s success in this field got him the post of Secretary to the Aero Club in the spring of 1906, but the lure of joining an American project to build a steam-powered vertical take-off and landing aircraft proved too much and in a matter of weeks 'A.V.' had set off for Denver, Colorado. 'A.V.' Returned to Britain in the autumn of 1906, following the collapse of the project and by January 1907 had embarked on the design of his own first full-size, man-carrying aircraft, the 6hp JAP-powered Roe I canard biplane. Once re-engined with the more manful 25hp Antoinette, this machine, piloted by 'A.V.', made what was arguably the first flight by a British Aircraft on 8 June 1908. Just over a year later 'A.V.' Gained Aero Club Aviator's Certificate No 18, flying his Roe III triplane. During the whole of this period, from 1906 to 1910, 'A.V.' was living in near poverty. In 1910, with help from his family, 'A.V.' Founded 'A.V.' Roe and Company and in July 1911 gave up flying to concentrate on the design work that was to establish him as one of the country's leading aircraft designers, with such machines as his Avro 504. 'A.V.' sold his interest in Avro in 1928 and received his knighthood the following year, during which he bought a controlling interest in what was, thereafter, to be Saunders Roe, of which he remained President until his death on 4 January 1958.

Despite the Admiralty's early initiative to employ their Avro 504s in the bombing role, albeit only carrying four 20lb Hale bombs apiece, the general adoption of the Royal Aircraft Factory BE 2c reconnaissance bomber by both the British services nearly ended the Avro 504 story in its infancy. Happily, someone in high places decided to give the old warhorse a further lease of life as the standard British military trainer. Fitted with a 110hp Le Rhone, the Avro 504K could reach a top level speed of 95mph at sea level and climb to 8.000 feet in 6.5 minutes. Including early 504 production, many of which were converted to 504Ks, around 5,440 examples were built under World War I contracts. After a pause in the immediate post-war years, more were to follow. Avro 504K, serial no E3404, seen here, was the first of a batch of 500 built by the parent company. Many more of the 504Ks built were produced by numerous sub-contractors.

Although not pursued beyond the prototype phase, the 1918 BAT FK 24 Baboon two seat trainer, built to an Air Board requirement, is of interest in terms of its choice of engine, along with aspects of its structure. Its power came from the specified 170hp ABC Wasp I radial, an indication, albeit later shown to be ill-judged, of the faith officialdom placed in the ABC radials. The Baboon's structure was not just robust, it was deliberately designed to use as many interchangeable components as possible, including the ability to switch upper with lower wings, plus being able to swap port and starboard elevators with the rudder. The machine's extra wide wheel track is also notable. Top level speed of the Baboon was 90mph at sea level, while climb to 10.000 feet could be achieved in 12 minutes. Seen here is serial no D 9731, the first of six ordered and the only one believed to have been completed.

During the last weeks of 1913, Frank Barnwell of Bristol's X' Department, drew up his first aircraft design. This machine, initially known as the Baby Biplane, became the Scout when demonstrated to the British Army in February 1914. With relatively minor modifications, this prototype was developed into the Scout B, of which the War Office bought two, followed by the Scout C, the first of the series to entered full scale production in late 1914 for both the RFC and the RNAS. The 110hp Clerget or Le Rhone powered Bristol Scout D, seen here, made its debut in November 1915. Armed with an overwing mounted single .303-inch Lewis gun, the Scout D had a top level speed of 110mph at sea level and entered operational service in February 1916. The RFC and the RNAS each took delivery of 80 Scout Ds.

The image of the F 2B chosen here is of serial no A 7231, captured by FI Abt 210 near Cambrai, during the summer of 1917.

Developed from the company's sole M IA and the four M IBs, the first of which made its maiden flight on 14 July 1916, the Bristol M IC was the only British front-line combat type to use a monoplane configuration during World War I and clearly represented an opportunity lost. Considered by officialdom as having too high a landing speed, at 49mph, for use on the Western Front, the M IC's deployment was confined to partially equipping five Middle East-based RFC squadrons, thus only 125 M ICs were built between September 1917 and February 1918. Armed with a single .303-inch Vickers gun, the M IC, powered by a 110hp Le Rhone, was capable of a top level speed of 130mph at sea level and of operating at up to 20,000 feet. Reputed to have good overall handling characteristics, this appears to be borne out from the fact that M ICs were highly sought after as senior flight officers' hacks.

The two seat Bristol S 2A fighter, a derivative of the Bristol Scout D was unusual in that it had the pilot and gunner placed side-by-side. Built originally to an Admiralty requirement, the first of the two built, serial no 7836 seen here, first flew in May 1916. Using a 110 Clerget, or 100 Gnome Monosoupape, the S 2A had a top level speed of 95mph at sea level. While not pursued as a fighter, both S 2As went on to serve as advanced trainers with the Central Flying School.

The prototype Airco DH I two seater, serial no 4220, seen here at Hendon and still without any form of markings was first flown in late January 1915. While this machine used a 70hp Renault, the subsequent 49 DH Is, used as trainers, were fitted with an 80hp Renault. When later hard pressed to counter the Fokker Eindekker threat, the RFC asked Airco to look at converting their DH I into a reconnaissance fighter by using a 120hp Beardmore and adding a flexibly mounted .303-inch Lewis gun for the observer in the nose. Known as the Airco DH Ia, the uprated type was flight tested by Martlesham Heath against the Royal Aircraft Factory FE 2b, which it simply outflew. Regrettably, for the DH Ia, the FE 2b was already in large-scale production and, thus, only 50 machines were to be built, most of which went to training units.

The gun-equipped DH Ia shown here carried the serial no 4607 and was the second of six to see service from June 1916 with No 14 Squadron, RFC, based in Palestine.

The two seater Airco DH 4, first flown in mid-August 1916, was to prove one of the finest fast light bombers of World War I. Using a variety of engines, whose outputs ranged from 190hp to 375hp, the typical late production DH 4, of which A 7995 seen here is an example, used a 250hp Rolls-Royce Eagle III, giving it a top level speed of 119mph at 6,500 feet, along with a ceiling of 16.000 feet. The first unit to deploy the DH 4 operationally was No 55 Squadron, RFC, on 6 March 1917. Typically, the DH 4's warload was four 112lb bombs, but two 230lb weapons could be carried. Used by both the RFC and the RNAS, armaments varied, with RFC machines carrying the standard two-seater fit of a single Vickers and a single Lewis gun, while in the RNAS DH 4s the armament was doubled at some cost in performance. One major shortfall with the DH 4 was the lack of communications between pilot and observer, solved in the near identical DH 9 airframe by bringing them closer. In all, Airco and five sub-contractors were to build 1.538 DH 4s, a figure dwarfed by US production.

The men and machines of the 11th Aero Squadron, operational from 5 September 1918. The DH 4s carry the unit emblem on their noses. This consisted of a comic strip character called 'Jigs', who is toting a bomb under his right arm.

One of the beneficiaries of the American decision to build existing types, while 'home grown' products were being developed was the Airco DH 4, of which 4.846 were built in the US, primarily by Dayton-Wright. In October 1918 one of these machines became the DH 4B after its conversion to mimic the closer crew positions of the Airco DH 9. Using a 416hp Liberty 12A, the DH 4B had a top level speed of 124mph at sea level. By the time the conversion programme came to an end in 1923, another 1.537 DH 4s had become DH 4Bs.

The de Havilland designed single-seater Airco DH 5, characterised by its novel back-staggered wing arrangement chosen to improve pilot visibility, was to prove a disappointment. Completed during the autumn of 1916, the DH 5 was found to lack performance above 10.000 feet, as well as being tricky to land. These problems, coupled to severe delivery delays with the DH 5's 110hp Le Rhone 9J, saw the type's role being relegated from fighter to ground attack and production being limited to 550 aircraft. Initially delivered to No 24 Squadron, RFC, in May 1917, the DH 5's top level speed was 102mph at 10.000 feet, decreasing to 89mph at 15.000 feet. Armament was a single .303-inch Vickers - somewhat puny for trench strafing - while the machine's overall performance compared poorly to that of the Sopwith Pup already in service. The DH 5 seen here belonged to No 68 Squadron, RFC, based at Baizieux.

Designed from the outset as a primary trainer, the Airco DH 6 emerged early in 1917. Designed to be both easy to fly and repair, the early DH 6s were powered by a 90hp RAF IA, but shortages of this engine led to the adoption of either the 80hp Renault or 90hp Curtiss OX-5. Top level speed of the DH 6 fitted with an RAF IA, as seen here fitted to Serial no B2612, was 70mph, while the initial climb was a meagre 225 feet per minute. By late 1917, the DH 6 had been dropped in favour of the Avro 504K as the RFC's standard trainer, enabling more than 300 of the total 2.303 DH 6 and DH 6a production to be switched to the RNAS for anti-submarine coastal patrol work, carrying a 100lb bombload.

Resplendent in his RFC Captain's uniform Geoffrey de Havilland is seen here beside the Airco DH 9 that he had designed. Born the son of a clergyman in 1882, Sir Geoffrey, as he was to become, entered the automotive industry for a few short years before contracting the 'aviation bug' in 1908. Armed with ?1,000 advanced by his father and with the help of his friend, Frank Herle, de Havilland built a canard biplane with a 45hp Iris engine built to his design. With this machine, de Havilland managed to make one short hop before it was 'written-off' in December 1908. In 1910, de Havilland produced his second design, which while offering little novelty, had the great attribute of actually flying, its first flight taking place on 10 September 1910. It was with this machine that the young designer/pilot taught himself to fly. Already married, Geoffrey de Havilland was no doubt pleased when his work came to the attention of the War Office, who bought his second biplane for ?400 and took him on as an aeroplane designer and test pilot at Farnborough's Royal Balloon Factory. Here, working in harness with the Factory's design engineer, Frederick Green, De Havilland transformed a number of dubious flying machines into useful aircraft, starting with the FE 2 and culminating in the spectacularly advanced BS I, later rebuilt as the SE 2A. Growing unhappy at the now renamed Royal Aircraft Factory, de Havilland resigned in June 1914 to join Thomas Holt's Airco as their Chief Designer, where, with the exception of a short break to join the RFC later that year, he was to stay until 1920 and the dissolution of the company. During this time, he not only designed the DH 1 through DH 18, he also took them up for their first flights. On 25 September 1920, he and colleagues were to found the de Havilland Aircraft Company. Producers of many famous aircraft, including the ubiquitous Mosquito of World War II and the post-war Comet jetliner, this company was to emblazon the skies with the de Havilland name. Sir Geoffrey, who had lost two of his three sons in flying accidents, died in 1965.

Officialdom's interference has often been cited as one of the main obstacles to aircraft development and certainly this was the case with Britain's Airco DH 9. This successor to the very successful day bomber DH 4, first deployed in March 1917, should have been a simple re-design of the fuselage centre section to place the pilot further back and far closer to the observer. Instead of this straightforward improvement, the War Office, in its wisdom, also chose to fit a totally new and untried engine to the DH 9. The ongoing troubles with this engine ensured that the later machine was generally inferior to its predecessor in virtually all operational aspects except crew communications.

A Standard Type De H.9 (240 h.p. B.H.P. engine) / In what appears to have been a classic example of snatching defeat from the jaws of victory the prototype Airco DH 9 had been converted from a production DH4. This aircraft, first flown in August 1917, embodied a revised nose to take the new and still largely untested Siddeley Puma, along with the pilot's cockpit moved aft, far closer to the observer so as to improve crew communications, albeit at the expense of the pilot's forward visibility. Even with these changes, quite a lot of commonality existed between the DH 9 and its precursor, which should have led to a minimum of production problems in switching between the two machines. This was not to be the case, with deliveries of the DH 9 only getting underway in January 1918, thanks in large part to the Puma engine that required de-rating from an originally envisaged 300hp to 230hp. To make matters worse, the loss of engine power affected performance to a serious degree, ensuring that the DH 9's capability was actually inferior to that of the DH 4. Despite this state of affairs, no less than 3.890 DH 9s were produced out of the 5.584 originally ordered, before production switched to the re-engined DH 9a. To some degree, the decision to press ahead with production of such a disappointing machine could be explained by the pressure to expand the number of British bomber squadrons. The DH 9's full bomb load was 460lb and its top level speed was 109.5mph at 10.000 feet. The machines ceiling was 15.500 feet, while its armament was the single Vickers gun for the pilot, plus the one or two flexibly-mounted Lewis guns for the observer.

Another example of an opportunity frittered away, the Airco DH 10 Amiens could well have played a useful role on the Allies' behalf, had not nearly eighteen months been lost to policy vacillation. A simple development of the Airco DH 3 of early 1916, the first of four prototype Airco DH 10 Amiens made its maiden flight on 4 March 1918 and proved underpowered on the output of its two 230hp Siddeley Pumas mounted as pushers. The second prototype, serial no C 8659 seen here, used twin, tractor-mounted 375hp Rolls-Royce Eagle VIIIs, while the third prototype had two 400hp Liberty 12s, again tractor-mounted. It was this machine that served as the standard for subsequent production Amiens. Essentially too late to play any real part in the air war, this three man bomber, with its top level speed of 117.5mph at 6,500 feet and maximum 1,380lb bomb load was just entering large-scale production at the time of the Armistice. Of the 1,295 DH 10 and DH 10a Amiens ordered, only eight were in the RAF's hands, of which two examples had been delivered to No 104 Squadron, RAF, at Azelot at war end. However, some of the 268 DH 10s built did enter post-war service with Nos 60. 97, 120 and 216 Squadrons, RAF.

While the designers and engineers at Handley Page must be given credit for building the finished product, the true creator of Britain's first long range, heavy bomber, the Handley Page 0/100 was Murray F. Sueter, who, as Director of the Admiralty's Air Department in late 1914, went to their Lordships with a request to develop a 'bloody paralyser' of an aeroplane initially envisaged as being capable of long range, over-water patrolling. This demand formally emerged from the Admiralty Air Department on 28 December 1914 and was taken up by Handley Page, who first flew their prototype 0/100 just under a year later, on 17 December 1915. Incidentally, this flight was made by Lt Cmdr J.T. Babington, RNAS, the Navy's on-site man responsible for nursing the 0/100 from its birth to its initial operational deployment in October 1916, with Babington then commanding the 'Handley Page' Squadron, attached to the RNAS's 3rd Wing, based near Nancy in eastern France. Unfortunately for the RNAS, initial deliveries were slow, coupled to which early 0/100 operations, commencing in November 1916, were off-shore patrols, usually carried out by single aircraft in daylight. However, all 0/100 missions were switched to night flights after one had been lost to enemy action over the North Sea, on the 25 April 1917. Indeed, the continuing use of 0/100s in ones and twos to raid German submarine and Gotha bases along the Belgium coast characterised operations during the first half of 1916 and its was not until mid-August 1917 that 0/100s began to be dispatched in two-digit strength. Capable of lifting a bomb load of up to 1.792lb, 40 of the 46 four man 0/100s built were powered by twin 250hp Rolls-Royce Eagle IIs, giving a top level speed of 76mph at sea level, while the last six machines used the 320hp Sunbeam Cossack that pushed the top level speed up to 84.5mph at sea level. The image shows 0/100, serial no 3116, of the RNAS's 5th Wing based at Coudekerque, taken on 4 March 1917 and accompanied here by a Sopwith Triplane and a Nieuport 24bis.

Any American career the Handley Page 0/400 may have made for itself was to be overtaken by the Armistice, with only a handful of the 1,500 US machines ordered having been completed. Modified to take twin 400hp Liberty 12 Ns, these American 0/400s were built by the Standard Aircraft Corporation of Elizabeth, New Jersey. The Standard-built, Liberty-powered 0/400 seen here at Kelly Field, Texas, is flanked by a Thomas-Morse S-4 on the left and a Curtiss JN on the right.

The Handley Page 0/400 was a direct development of the 0/100 employing twin 360hp Rolls Royce Eagle VIIIs or 400hp Liberty 12s for the planned US aircraft, the former engines giving the four-man bomber a top level speed of 97mph. The converted 0/100 that served as the prototype for the 0/400 was first flown in September 1917, but initial deliveries of the planned 400 aircraft did not start until March 1918, the first going to No 16 Squadron, RNAS, just prior to their becoming No 216 Squadron, RAF, on 1 April 1918. The image of a 'folded' 0/400 seen here has been chosen specifically to emphasise some of the problems imposed on aircraft designers by the occasional need to hangar such large machines in something not much better than a king-sized tent.

The giant Handley Page V/1500, successor to the the company's 0/100 and 0/400 bomber series, was another of those machines that arrived too late to effect the course of the air war. Initially, the V/1500 had been designed around two 600hp Rolls-Royce Condors, but development delays with this engine saw its substitution by four 375hp Eagle VIIIs. First flown on 22 May 1918, by Capt V.E.G. Busby from RAF Martlesham Heath, the original tail unit seen here in the ground view of prototype, serial no B 9463, proved unsatisfactory, being replaced by one with a much higher gap that raised the upper tailplane considerably. Capable of carrying a maximum bomb load of 7.500lb over short ranges, or 1,200lb to Berlin from its Norfolk base, the four man V/1500 had a top level speed of 97mph at 8.750 feet, along with an economic cruising speed of 90.5mph at 6,000 feet. At the time of the Armistice only three of the 255 V/1500s on order had been delivered to No 166 Squadron, RAF, at their Bircham Newton airfield, the rest being cancelled.

First flown in May 1918, the giant Handley Page V/1500, along with the Bristol Braemar and Tarrant Tabor, had all been designed to carry a 1,000lb or more bomb load to Berlin from their No 27 Group, RAF, bomber bases in eastern England. Over a much shorter range, the V/1500 could carry a maximum bomb load of 7,500lb. The two machines seen here belong to No 166 Squadron, RAF, based at Bircham Newton, Norfolk. Deliveries of these aircraft had commenced in September 1918, only three having arrived at the time of the Armistice.

Clearly influenced by the success of the Sopwith Tabloid and Bristol Scout, the Martinsyde S I prototype unarmed single-seat scout emerged during the late summer of 1914. Initially, the S I had a clumsy-looking four wheel landing gear, happily replaced by the time this machine, serial no 4241, was photographed. With an 80hp Gnome rotary, the S I's top level speed was 87mph at sea level and its performance was generally considered inferior to both of its illustrious forebears. Only 61 S Is were built, with deliveries to the RFC lasting for about a year between late 1914 and October 1915. Never to equip a complete squadron, S Is were used by five French-based RFC squadrons, plus another RFC squadron in Mesopotamia.

First flown in September 1915, the prototype Martinsyde G 100, serial no 4735, was a single-seat, long range fighter using a 120hp Beardmore with fuselage flanking radiators. This machine was followed by 100 production G 100s, whose engines had a much cleaner nose-mounted radiator. The G 100's effective armament was a single, overwing .303-inch Lewis gun, although a second, rearward-firing Lewis gun was fitted, presumably more in hope than expectation. Deliveries of these G 100s started early in 1916, with many going in twos and threes to serve as the escort sections of four RFC bomber squadrons in France and six in the Middle East. Indeed, only one unit, No 27 Squadron, RFC, was to be exclusively equipped with the type. With a top level speed of 97mph at sea level and lacking agility and pilot visibility, the G 100 was soon switched to bombing duties, thanks to its 5.5 hour endurance and ability to carry a 230lb bomb load. Around another 200 of the 160hp Beardmore powered single seat G 102 reconnaissance bombers were subsequently produced.

Another story of an extremely useful fighter denied the Allies was that of the Martinsyde F 4 Buzzard, itself the last and by far most successful of a line of fighter designs that started with the two seat F I of early 1917. Counted among the fastest aircraft extant, the F 4 was powered by a 300hp Hispano-Suiza 8 Fb that endowed it with a top level speed of 140mph at sea level, decreasing to 132mph at 15.000 feet. Furthermore, the F 4's ability to reach 10,000 feet in 7 minutes 55 seconds represented a marked improvement over that of the Sopwith Snipe. The F 4's armament fit consisted of two synchronised .303-inch Vickers guns. First flown in early 1918, the F 4 was ordered into quantity production, but hold-ups with engine deliveries meant that only 48 F 4s had been handed over out of the 1,450 British orders at the time of the Armistice. Interestingly, in a reversal of the historic practice, this British fighter had been chosen for use by the French, as it was by the Americans, but orders from these nations were cancelled at war end. Seen here is F 4, serial no D4263.

The armament installation on the Martinsyde F.4 Buzzard was perhaps the most advanced of any 1914-18 fighter. This view shows brackets for an Aldis sight and should be studied jointly with others under the heading 'Aircraft Disposal Company'. A panel covers the ejection chute.

The armament installation on the Martinsyde F.4 Buzzard was perhaps the most advanced of any 1914-18 fighter. This view shows brackets for an Aldis sight and should be studied jointly with others under the heading 'Aircraft Disposal Company'. A panel covers the ejection chute.

Designed as a side-by-side, two seat flying boat trainer, 179 examples of the Norman Thompson NT 2B are known to have been built of the 284 ordered. Derived from the sole NT 2A tandem seat flying boat fighter, the NT 2Bs used either the 150hp or 200hp Hispano-Suiza, or the derivative Sunbeam Arab. Deliveries of the NT 2B commenced in December 1917, the type being flown in large numbers from Calshot and Lee-on-Sea on the south coast, while more were based at Felixstow on the east coast. Top level speed of the NT 2B was typically 85mph at 2.000 feet, while its ceiling was 11.400 feet. Serial no N2560 seen here was from the last production batch of 25 aircraft to be completed. Note the enclosed cockpit.

Lt Harvey-Kelley, seen puffing his cigarette as he studies the map beside his Royal Aircraft Factory BE 2a, serial no 347. Harvey-Kelley and his machine were the first of Britain's aviation expeditionary forces to land in France during the second week of the war. The BE 2a's 70hp Renault gave the two-seater reconnaissance type a top level speed of 70mph at sea level. The ceiling of the early BE 2s was around 10,000 feet, along with an endurance of about 3 hours.

This Royal Aircraft Factory BE 2c, serial no 9951, is one of a known 111-aircraft batch built by Blackburn. This variant made its operational debut in April 1915 and was a marked improvement over the earlier BE 2s, using ailerons, rather than wing warping. Fitted with a 90hp Royal Aircraft Factory-developed RAF Ia engine, the two-seat BE 2c had a top level speed of 72mph at 6,500 feet, dropping to 69mph at 10.000 feet. Besides its primary reconnaissance role, the BE 2 served as a bomber, an anti-submarine patroller and a trainer. Deliveries of the BE 2c to the RFC accounted for 1,117 machines, plus a further 307 operated by the RNAS, of which the aircraft seen here was one.

Added protection for this Royal Aircraft Factory FE 2d came in the form of a second, pedestal-mounted .303-inch Lewis gun just ahead of the pilot. Operated by the front-seated observer, this flexibly trained weapon provided him with an upwards and rearwards arc of fire. Also noteworthy in this image is the long focal depth reconnaissance camera that the observer is pretending to sight.

First flown on 8 November 1915, the Royal Aircraft Factory FE 8 was a pusher-engined, single seat fighter that was already obsolescent when the first deliveries were made to No 29 Squadron, RFC, in mid-June 1916. Powered by a 110hp Le Rhone or Clerget rotary, giving the machine a top level speed of 97mph at sea level, its armament comprised a single .303-inch Lewis gun. 297 FE 8s are known to have been built. The FE 8, serial no 7624, seen here being inspected by its German captors, was photographed near Provin on 9 November 1916.

The Royal Aircraft Factory RE 8 was selected for mass production before the prototype's first flight in the spring of 1916. Powered by a 150hp RAF 4a, this two-seat reconnaissance bomber was not a very impressive performer with a top level speed of 103mph at 5.000 feet, falling off to 96.5mph at 10,000 feet. Its bomb load was 260lb. To compound the problems, the early RE 8s were prone to 'spin-in' if mishandled and even when this problem was remedied by adding ventral fin area, the 'Harry Tate', as it was nicknamed, proved sadly lacking in agility, making it relatively easy prey for its German opponents. Its first operational deployment was with No 52 Squadron, RFC, in November 1916. The RE 8's armament consisted of a fixed 303-inch Vickers for the pilot, plus one or two flexibly mounted .303-inch Lewis guns for the observer. Some later machines used the 150 hp Hispano-Suiza, being referred to as the RE 8a. A total of 4,077 RE 8s were to be built, all but 22 Belgian-operated aircraft going to the RFC. This is a standard production RE 8.

The Royal Aircraft Factory SE 5, powered by a 150hp direct drive Hispano-Suiza, initially took to the skies on 22 November 1916. Carrying a two-gun armament of one fixed, nose mounted, synchronised .303-inch Vickers, plus a .303-inch Lewis mounted above the wing that could be locked to fire ahead of the aircraft, or freed to swing through a limited arc of elevation, enabling the pilot to rake an enemy's underside. Virtually viceless in terms of pilot handling problems and capable of 122mph at 3.000 feet, decreasing to 116mph at 10,000 feet. The operational ceiling of the SE 5 was 17.000 feet, while the single seater could reach 10,000 feet in 13 minutes 40 seconds. Most of the 59 SE 5s built went to No 56 Squadron, RFC, commencing in March 1917, prior to their appearance on the Western Front the following month. These interim SE 5s were soon to be replaced by the more powerful SE 5a, arguably the finest of Britain's World War I fighters. This rearward aspect on SE 5, A8913 helps emphasise the use of broad chord ailerons on both upper and lower wings - a feature that improved the aircraft's 'rollability'

Without question the SE 5a was the finest design to come from the Royal Aircraft Factory during its entire existence. The creation of Henry Folland's fertile mind, the SE 5 series of single seat fighters were both heavier and faster than the Sopwith Camel, which they also preceded into operational service. Despite the long standing claim that the Camel downed more enemy aircraft than its rival, which machine was the best will remain a matter of controversy similar to the Hurricane, versus Spitfire question of the next World War. Certainly, while advocates of the SE 5 have to bow to the Camel's quantative 'kill' superiority, they can point to the generally more pilot friendly handling of the SE 5 and speculate about the Camel's 'kill rate' and on which side of the balance sheet to include all of its own pilots that the unforgiving Camel killed.

James Thomas Byford McCudden is seen here seated in the cockpit of his Royal Aircraft Factory SE 5a, McCudden, born on 25 March 1895 in Gillingham, Kent, came up through the enlisted ranks to became Britain's most highly decorated airman of World War I. Entering the British Army's Royal Engineers as a boy bugler in 1910, McCudden was to die a major six years later. As with a number of other fighter aces from both sides of the line, McCudden's flying career started as an observer and graduated into piloting two seat Royal Aircraft Factory FE 2d reconnaissance machines with No 20 Squadron, RFC in July 1916 for a few days, prior to joining the single seat Airco DH 2-equipped No 29 Squadron, RFC, on 1 August 1916. Before the month was through, McCudden, a cool, analytical pilot, had opened his tally of downed enemy aircraft by dispatching a two-seat Hannover CL III. Indeed, McCudden, like Manfred von Richthofen and many other aces, tended to specialise in stalking two seaters, 'killing' no less than 45 of these machines out of his confirmed overall score of 57. Commissioned on 1 January 1917, McCudden was invited to join the hand-picked Royal Aircraft Factory SE 5a-equipped No 56 Squadron, RFC, joining the unit as a Captain and Flight Commander on 15 August 1917. By the end of 1917, McCudden had taken his victory score to 37, adding a further 20 between 1 January 1918 and 16 February 1918, when he was posted home. On 6 April 1918, McCudden, already the proud holder of the Distinguished Service Order and bar, the Military Cross and bar, along with the Military Medal, was awarded Britain's highest military recognition for valour, the Victoria Cross. On 9 July 1918, the newly promoted Major James McCudden, Commanding Officer designate of No 60 Squadron, RFC, suffered an engine failure on take off for France, spinning in to his death while attempting to return to the airfield.

A future fighter ace in the making. This image of the nineteen-year-old Second Lieutenant Albert Ball shows him standing in front of a Caudron G III of the Ruffy-Baumann School of Flying at Hendon during the summer of 1915. As was the British Army practice of the day, any officer wishing to transfer to the RFC had to pay for his own initial flying training, only being reimbursed once he had gained his Aero Club Aviator's Certificate. Born in August 1896, Albert Ball was barely eighteen when commissioned into the Sherwood Forresters during October 1914. Determined to fly, Ball gained his Aviator's Certificate on 15 October 1915. Further flying training with the RFC brought Ball his military wings in January 1916. Ball joined his first operational unit, No 13 Squadron, RFC, at Vert Galand, France, flying the BE 2c, in February 1916. Three months later, in May 1916, Ball joined No 11 Squadron, RFC, a single-seater unit at Savy, flying Nieuport 16s and Bristol Scouts. Between then and October 1916, when Ball was sent home to instruct he had been promoted to Lieutenant and credited with a confirmed 31 'kills' in April 1917, Ball, now a Captain and 'A' Flight Commander of the newly formed, crack No 56 Squadron, RFC, flying SE 5s, returned to the Western Front. In the less than two week period between 23 April 1917 and 6 May 1917, Ball was to down a further 13 of the enemy, to bring his total confirmed score to 44. On the following evening of 7 May 1917, Ball's SE 5a was seen to break out of cloud base in an inverted spin and crash. Although Ball had been in combat with machines of Jasta II, his death has been attributed to vertigo, or being knocked unconscious by a loose Lewis gun ammunition drum - the former being less likely than the latter which was a known hazard to Nieuport and SE 5 pilots. Ball, already the holder of a Military Cross, Distinguished Service Order and Bar, was posthumously awarded Britain's highest military award for gallantry, the Victoria Cross.

Though sometimes called a 'Sopwith Gordon Bennett' this particular Tabloid variant was acquired by the Admiralty and was distinguished not only by a 'racing' landing gear and liberally ventilated cowling, but by a Lewis gun fixed on the starboard side and firing ahead by virtue of a deflector propeller / A revealing aspect on an experimental Lewis gun mounting on this late production Sopwith Tabloid scout. Note the armoured propeller cuffs approximately half way out along each blade, used to deflect any impacting round of ammunition.

The Sopwith Three Seater of 1913 was an impressive performer, with the power of its 80hp Gnome setting a number of British altitude records in June and July 1913, in the hands of the by then Sopwith Chief Test Pilot, 'Harry' Hawker. Of these the highest reached was 12,900 feet with one passenger. The Three Seater could carry a 450lb payload at 70mph. At least seven of these machines were known to have been operated by the naval wing of the RFC.

An early Sopwith Baby, or Schneider, fitted with a 100hp Gnome Monosoupape. The RNAS bought their first Babys shortly after the start of hostilities, using them as unarmed scouts. However, from early 1915 onwards these little seaplanes were fitted with a swivellable-in-elevation-only, over-wing-mounted .303-inch Lewis gun and employed as armed shipboard scouts or for the local defence of seaplane bases. A little too fragile to operate in much of the weather experienced around Britain and the North Sea during winter, the Baby came into its own when operated in the Balkans and Middle East. Production of the type commenced in November 1914, with 296 being built.

The French, who until now had been a prime supplier of aircraft to both the RFC and RNAS, saw the RFC using the Sopwith 1 1/2 Strutter as two-seat fighters to good effect during the July 1916 Battle of the Somme and were impressed enough to promptly negotiate a licence to build the aircraft and put it into large scale production. Indeed, of the total 5.720 examples built. 4,200 were French-produced. As it was, the French chose to produce the 1 1/2 Strutter in both single-seat bomber and two-seat reconnaissance form, but ran into delivery problems, as a result of which the mass of French aircraft were not delivered until the summer of 1918, by which time they were obsolescent, if not obsolete. As a two seater, the machine was usually powered by a 110hp Clerget that gave a top level speed of 106mph at sea level, along with a ceiling of 15,000 feet. In comparision, the single-seat bombers, with their various 110hp or 130hp rotaries could carry a bomb load of up to 224lb and had a top level speed of 102mph at 6.560 feet. Of the French machines, 514 were purchased by the American Expeditionary Force, while the type also served in small numbers with the air arms of Belgium, Latvia, Romania and Russia. Note the distinctive camouflage scheme applied to this French-built and operated example.

The image seen here is of serial no N5504, one of the single-seat bomber version of the 1 1/2 Strutter, with bomb doors closed and showing clear-view top-wing panels. The Vickers gun is present, and was indeed standard.

This is 4th of a 50 aircraft Sopwith-built batch for the RNAS. This aeroplane survived the War and was converted for private sporting use as G-EAVB.

This is 4th of a 50 aircraft Sopwith-built batch for the RNAS. This aeroplane survived the War and was converted for private sporting use as G-EAVB.

Essentially an Admiralty sponsored design, carrying their Type 9700 designation, the Sopwith 1 1/2 Strutter. Suffice to say here that the type was also operated by by the RFC. Serial no A 6901, seen here, was the first of a 100 aircraft batch produced by Hooper & Co Ltd of Chelsea for the RFC and is particularly interesting in being one of the only four single-seat home defence fighter variants built.

This image of a Sopwith 1 1/2 Strutter being flown from a makeshift turret-top platform epitomises the initiative and invention so often displayed by the Royal Navy and its Air Service during World War I. The Royal Naval Air Service's innate sense of 'daring do' is exemplified in many ways, ranging from tackling Zeppelins in their lairs to developing Britain's first heavy bombers, and provides quite a contrast with the much more restricted thinking of those charged with shaping the development of the Royal Flying Corps.

Today there are few that remember that the Sopwith 1 1/2 Strutter started its life as the Sopwith Type 9700 designed to meet an RNAS need for a two-seat reconnaissance fighter. With an Admiralty order for 150 aircraft in hand, Sopwiths completed the first example in mid-December 1915 and wasted little time in delivering initial production machines to operational RNAS units early in the new year of 1916. Powered by various 110hp to 130hp rotaries, the 1 1/2 Strutter had a top level speed of 106mph at sea level, decreasing to 102mph at 6,500 feet. For armament, the machine used a fixed, forward-firing Vickers, plus a flexibly-mounted Lewis for the observer. Of the S50 aircraft delivered to the RNAS, around 130 were of the single-seat bomber variety, which could carry up to 300lb of weapons in the shape of twelve 25lb bombs, while the two seaters lifted 224lb, or four 56lb bombs. The type's performance was such as to lead to orders not just from the RFC, but from several other nations and the machine's broader programme history is dealt with earlier in the chapter on French aircraft. The image is of an RNAS 1 1/2 Strutter departing from atop one of a capital warship's main turrets. This kind of operation was to become relatively routine from April 1918 onwards.

First flown in March 1917, the Sopwith IF Camel, like that of its precursor, the Pup, was the joint brainchild of Sopwith's pilot Harry Hawker and engineer Fred Sigrist. Unlike the Pup, however, the Camel never basked in its pilot's unmitigated delight at its handling, indeed, the Camel's capricious in-flight behaviour left not just much to be desired, but many young, inexperienced Camel pilots dead. The Camel's problems, which could also be used to effect by experienced fliers, stemmed from the fact that much of its mass, comprising engine, twin .303-inch Vickers guns, pilot and fuel, all lay within the first 7 feet of its overall 18.75 feet fuselage length, This, combined with the high torque reaction involved with its 130hp Clerget 9B rotary and, in particular, the short rudder moment arm, ensured that the machine turned to starboard, or the right, with breathtaking rapidity, while causing the nose to drop. If this tight turn was not rapidly corrected with rudder, the aircraft would readily enter a spin from which it was difficult to escape at low altitude. In the case of a turn to port, or to the left, the rate of turn was far less ferocious, while this time the nose rose. So long as he survived the initial familiarisation phase of Camel flying, the pilot could then use these characteristics to effect, by using its 'instant' starboard turning capability to out-turn his enemy and, thus, rapidly position himself behind his foe. Operational deployment of the Camel came in July 1917, with deliveries of the machine going to both RFC and RNAS squadrons. The IF Camel's top level speed of 115mph at 6,500 feet fell off to 106.5mph at 15,000 feet, while the single seater reached 10.000 feet in 10 minutes, 35 seconds while on its way to its 17.300 feet ceiling. Besides the standard Clerget, other rotaries were fitted to various IF batches, ranging from 110hp Le Rhones to the 150hp Bentley BR I. The image is the Sopwith IF Camel of No 139 Squadron, RFC's leader, the then Capt W.G. Barker, whose mount carried seven, rather than the unit's normal four fuselage white stripes aft of the roundel.

Elliott White Springs, son of a reasonably wealthy mill owner, was born in South Carolina on 31 July 1896. It was while White Springs was at Princeton University that America entered the war in April 1917. Filled with the patriotic zeal of youth, along with an initial introduction to aviation provided by Princeton, White Springs gained a commission in the US Army and set sail for Britain and six months of flying training in September 1917. During his training, White Springs was fortunate enough to benefit from the tutelage of Canadian fighter ace 'Billy' Bishop. Clearly, White Springs, himself must have been an excellent pupil, for, later, when Bishop, as leader of the RAF's crack No 85 Squadron, was busy readying the unit for operations with their Royal Aircraft Factory SE 5a, he invited White Springs to join him. On 22 May 1918, No 85 Squadron crossed the English Channel and ten days later White Springs got his first confirmed 'kill' in the shape of a Pfalz D III. By 27 June 1918, the youthful American's score had risen to 4, at which time he was shot down and slightly wounded himself.. In July he was transferred, as a flight commander, to the all-American, Sopwith Camel-equipped 148th Aero Squadron attached to the British 65 Wing. Here, with the 148th Aero, between 3 August 1918 and 5 September 1918, White Springs was to add a further eight victories to his tally, bringing his final wartime total to 12. In October 1918 White Springs was promoted to Captain and given command of the 148th, now re-assigned to the US 4th Pursuit Group. Not happy with life back in the US after the war, White Springs returned to Paris, where he wrote a best seller 'War Birds', based on his experiences. Later and now more settled, White Springs returned to the US, taking the family business to new heights. Elliott White Springs, seen here standing beside his British marked Sopwith Camel, died on 15 October 1959.

A revealing view depicting the intricacies of stowing and unstowing a Sopwith Pup aboard the Royal Navy seaplane carrier, HMS Manxmen. Remembering that the Pup was among the smallest of naval aircraft, it is understandable that larger machines, such as the Short and Fairey floatplanes that followed, necessarily required wing folding. Incidentally, the Pup seen here, N6454, was one of a 30-aircraft batch built by the Scottish-based William Beardmore.

The story of one of Britain's finest fighters is one of nothing less than a glorious opportunity carelessly thrown away. The first of the Admiralty-funded Sopwith Triplane single-seat fighters, serial no N500, was completed on 28 May 1916, with Harry Hawker giving it its first air test that day. Such was the Australian's confidence in the machine that he is reported to have looped the aircraft within three minutes of its first lift-off. By mid-June 1916 the machine was in northern France, being put through its operational evaluation by RNAS pilots, who all were particularly impressed by its phenomenal rate of climb. The tone of the ensuing report was extremely complimentary to the point that, as in the case of the preceding Pup, the Triplane was ordered into large scale production for both the RNAS and RFC. All of these events, it should be noted occurred before the end of summer 1916. Then, on 30 September 1916, in a letter to the War Office, Sir Douglas Haig warned that British air superiority over the Somme was in serious jeopardy thanks to the emergence of the new German fighters. Haig followed this first letter within a matter of weeks by asking for an extra twenty fighter squadrons. This should have given even more impetus to the gathering Triplane programme, but for reasons far more to do with the convoluted political machinations of Whitehall than the rational allocation of resources, the earlier large RFC order for the demonstrably useful Triplane appears to evaporate, while even the RNAS allocation becomes limited to 150 aircraft. Further, all this prevarication held Sopwiths back in terms of delivering production machines, these failing to appear much before year-end 1916. Certainly, it would seem that during this period, the Germans gained considerable help from Whitehall! The vast majority of Triplanes were powered by the 130hp Clerget, giving the machine a top level speed of 117mph at 5,000 feet, decreasing to 105mph at 15,000 feet. The Triplane's ceiling was 20,000 feet, while it took 6 minutes 20 seconds to reach 6,500 feet and 10 minutes 35 seconds to achieve 15,000 feet. The standard Triplane armament consisted of a single, synchronised .303-inch Vickers gun.

A development of the earlier IF Camel, the Sopwith 2F Camel was evolved specifically for naval use, being characterised by its shorter wingspan and detachable rear fuselage to facilitate shipboard storage. Powered by either a 150hp Bentley BR I, the standard engine, or a 130hp Clerget 9B, the first 2F Camel was completed and flying by March 1917, however, it then took around six months before production deliveries began to flow to the service users. Developed specifically as a Zeppelin killer, the 2F Camel had a top level speed of 122mph at 10.000 feet, decreasing to 117mph at 15.000 feet. Its time to climb to 10.000 feet was 11 minutes 30 seconds, increasing to 25 minutes to reach 15.000 feet, while its ceiling was 17.300 feet. The machine's armament consisted of a nose-mounted Vickers, along with an overwing Lewis gun, while two 50lb bombs could be slung below the centre section. The 2F Camel was deployed in depth around the North Sea and on both sides of the English Channel; they were carried about and launched from atop battleship and battle cruiser main turrets, they were put aboard the Royal Navy's first aircraft carriers, while more venturesome minds, such as that of Charles Rumney Samson, conceived the idea of launching them from lighters, towed at high speed by destroyers. That they achieved the task set them is attested to by the fact that they accounted for three Zeppelins, L 54 and L 60 being destroyed at their Trondern base by seven 2F Camel bombers, launched from HMS Furious on 17 July 1918, while less than a month later, L 53 was brought down by Lt S.D. Culley, RN, from a towed lighter launch on 11 August 1918. Perhaps the most surprising thing about the 2F Camel saga was the fact that there were relatively so few of them produced, with Sopwith building 50, backed by Beardmore, who assembled a further 100 machines. The image shows a frontal aspect on the prototype 2F Camel, serial no N5.

The picture is of serial no N6797 on its launching platform atop 'X' turret of the battle cruiser, HMS Tiger.

Built at their Barrow-in-Furness facility, the Vickers R 23 was the first quasi-operational British airship and the lead machine of four, then two improved class of dirigibles. Powered by four 250hp Rolls-Royce Eagles, the 17 man crew R 23 had a top level speed of 52mph and cruised at 40mph. Short on bouyancy, the R 23's ceiling was an alarmingly low 3,000 feet, whilst its maximum bomb load of 400lb was around a ninth that of its near contemporary, the Imperial German Navy's 'u' class, L 48. First flown in September 1917, the R23 was delivered to the RNAS Airship Station at Pulham in Norfolk on the 15th of that month. Subsequently mainly employed on training duties, the R 23 was adopted as a mother ship for two Sopwith Camels during the summer of 1918. The other airships in this class consisted of the Beardmore-built R 24, Armstrong Whitworth's R 25 and the Vickers-built R 26. The two R23X or Improved R 23 Class airships were Beardmore's R 27 and Armstrong Whitworth's R 29. The image shows R 23 being 'walked' at Pulham.

The sole example of the single seat Sopwith Type B I Bomber, serial no B 1496, photographed in January 1918, while still at the manufacturers. Similar to the company's Cuckoo, but with two, rather than three bay interstrutted wings and a lighter looking landing gear, the B I was evaluated by the RNAS early in 1918. Subsequently being put into service with the Airco DH 4-equipped No S Wing, RNAS, based just outside Dunkirk, the B I was powered by a 200hp Hispano-Suiza, giving it a top speed of 118.5mph at 10,000 feet. The time to reach this altitude with a 560lb bomb load was cited as being 15 minutes 30 seconds.

The sole Sopwith Bee of 1917 was a diminutive single seater, largely attributed to Harry Hawker. Powered by a 50hp Gnome, the small overall 16 feet 3 inch wingspan, coupled to its 14 feet 3 inch length could indicate that it was Sopwith's submission for a compact, shipboard fighter, but this cannot be confirmed.

If the above mentioned Fairey Campania was the world's first dedicated carrier-going aircraft design, the Sopwith T1 Cuckoo set the mould for all subsequent carrier-borne machines by adopting wheels in place of floats. First flown in June 1917, the Cuckoo used a 200hp Sunbeam Arab and production deliveries of this single-seat torpedo bomber did not get underway for over a year, thanks in large part to the fact that the Admiralty were still experimenting with the flight deck layout of HMS Furious, while awaiting the September 1918 completion of HMS Argus. Because time concerns were not as pressing as normal, the Admiralty also elected to have the aircraft built by sub-contractors, rather than by Sopwith themselves. As it was, the first production deliveries were made to the Torpedo Aeroplane School at East Fortune in Scotland during early August 1918, with the first carrier-going deliveries being made to No 210 Squadron, RAF, aboard HMS Argus in late October 1918. Of the 260 Cuckoos ordered, just over 90 had been delivered at the time of the Armistice. Top level speed of the Cuckoo was 103.5mph at sea level, its ceiling being 12.100 feet. The image seen here shows serial no N6950, the first of 50 Blackburn-built aircraft dropping an 18 inch Mk IX torpedo.

The picture is of three Cuckoos aboard the aircraft carrier HMS Furious, with serial no N6980, a Blackburn-built aircraft nearest the camera.

First flown at the end of May 1917, the Sopwith 5F Dolphin started life as a high altitude single-seat fighter design, but saw service as a close air support machine, with trench and ground strafing as its primary role. Built around its 200hp geared Hispano-Suiza, that was to prove so troublesome, the Dolphin incorporated a set of backward, or negatively staggered wings. Highly thought of by officialdom, the machine was ordered into quantity production shortly after its operational evaluation in mid-June 1917. By 31 December 1917, 121 Dolphins had been delivered to the RFC, whose No 19 Squadron was the first unit to re-equip with the type in January 1918. In operational service, the type was not best loved by its pilots, their criticisms centring on the lack of head and neck protection in the event of the machine 'nosing-over', coupled to the flexible crossbar' mounting of two upward-firing Lewis guns. This rather cumbersome device had the major drawback of allowing the guns to swing and strike the pilot in the face, not the ideal situation in any circumstances and particularly not when flying at low level. As these guns supplemented twin, synchronised fixed Vickers guns, they were removed from most operational aircraft, with the exception of No 87 Squadron, who repositioned theirs atop the lower wings and outside the propeller arc. Top level speed of the Dolphin was 131mph at sea level. In October 1918, five Dolphins had been ordered for evaluation by the American Expeditionary Forces, but the cessation of hostilities soon afterwards ended this interest. At the time of the Armistice, while the engine-related problems had been overcome, only 600 or so of the 1,500 Dolphins airframes built by then had actually been delivered, the large part of the remainder awaiting the supply of engines. The image seen here is of the fourth prototype Dolphin and the first to incorporate the Dolphin's definitive shape.

Созданный на основе "Снайпа", внешне TF2 "Саламандер" отличался плоскими бортами фюзеляжа / The Sopwith TF 2 Salamander was an armour-clad version of the Sopwith Snipe used for close air support, or trench strafing duties. The first of three prototypes, serial no E5429 seen here, initially flew on 27 April 1918. Using the same engine and armament as the Snipe, the major difference between the two aircraft was the Salamander's additional 492lb of armour to protect the pilot. The Salamander's top level speed was 125mph at 3,000 feet, but the extra weight depressed the climb rate to a mediocre 6 minutes 30 seconds to reach 5,000 feet.

The Supermarine N IB Baby may not have been the world's first single seat flying boat fighter, but it can lay claim to being the first of British design. First flown in February 1918, two N IBs were to be built to meet an Admiralty requirement, the first, serial no N59, being powered by a 200hp Hispano-Suiza, while N60 used the 200hp Sunbeam Arab. Top level speed attained by N IB, N59, was 117mph at sea level. The Admiralty decision to operate Sopwith Pup and Camel fighters from aboard ship eliminated the need for such as the N IB, but Supermarine managed to incorporate much of this basic design into their Sea Lion I and II, the latter winning the 1922 Schneider Trophy after the previous year's event had been aborted.

The sole Vickers FB 14, serial no A3505, served as the prototype for a desultory series of two-seat, general-purpose machines, ending in the FB 14F. Designed as successors to the Royal Aircraft Factory BE 2 series in Middle East service, these 1916 FB 14s employed a variety of engines, ranging from the 160hp Beardmore to the 250hp Rolls-Royce Eagle. An FB 14's top level speed was a reasonable 99.5mph at sea level, but its climb performance was truly frightening, taking nearly 41 minutes to reach 10,000 feet, which itself was only 600 feet below the machine's ceiling. Typical armament comprised the standard pilot's fixed Vickers gun, plus a flexible-mounted Lewis gun for the observer. While the performance of subsequent variants could only improve, even that of the 250hp-powered FB 14D appears unremarkable. Figures on just how many of the series were built vary from between 41 to 100, with reports that some actually reached Middle East-based RFC units. About the only real figure available involved seven FB 14Ds delivered to home defence squadrons.

Although essentially too late to take part in wartime combat, the light and small design approach adopted by Rex Pierson in producing the Vickers Vimy makes an interesting comparision with the larger, earlier Handley Page 0/100 and 0/400 series of bombers and also goes to illustrate just how long a gestation time is required between drawing board and production even in times of war. Seen here is the fourth and last of the Vimy prototypes, serial no F 9569 and the first of the machines to use the 360hp Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII, the engine selected to power subsequent production aircraft. Originating in design terms from around July 1917, the first of the Vimys made its maiden flight on 30 November 1917. Once the Eagle VIII had been adopted, the three man Vimy bomber was seen to have a top level speed of 106.5mph at 3.000 feet, an endurance of 11 hours and be capable of lifting a maximum bomb load of 2,476lb. While no less than 1,130 Vimys had been ordered at the time of the Armistice, only 13 had been completed, of which only one had been dispatched to Nancy in France for operational evaluation by the RAF's Independent Force. In the wake of the war's end, Vimy orders were cut back to 112 aircraft.

During 1916, Westlands, who were already a subcontract aircraft builder for the Admiralty, was one of three firms that responded to an Admiralty requirement for a single seat, shipboard, floatplane fighter whose performance should exceed a top level speed of 110mph and have a ceiling in excess of 20.000 feet. The company built two Westland N IBs, serial nos N 16 and N 17, both machines powered by a 150hp Bentley rotary. First flown during August 1917, the folding wing N IB with its top level speed of 108mph at sea level was only marginally below the target figure. As it transpired the Admiralty floatplane fighter need was overtaken by the advent of the Sopwith 2F Camel.

With only a handful built, the AEG D I was one of the rarer types to find its way into front-line service with the single seater units during the latter half of 1917. Armed with twin 7.92 Spandaus and powered by a 160hp Mercedes, this diminutive fighter had a useful top level speed of 124mph, but this could well have been counter-balanced by poor climb, tricky handling and longish take-off requirement, if the machine's wing loading was as high as the photograph would suggest. The AEG D I, 4400/17, shown here belonged to Lt Walter Hohndorf, leader of Jasta 14. It was in this fighter that Hohndorf crashed to his death on 5 September 1917, after a combat in which he had scored his 12th 'kill'.

Oops! The Albatros C I of Lt Maass, Fl Abt 14, after nosing over in the snow at Subat on the Eastern Front during January 1916. The standard practice appears to have been that any new type found its way, initially, to the Western Front, then the Eastern Front, where the opposition was likely to be less fierce. Finally, when considered operationally obsolete, the machine would frequently pass into the training role.

Albatros C III has clearly landed on the wrong side of the lines and provides the focus of interest for a number of French civilians, while the soldier in the foreground and close to the photographer appears more concerned with grooming his moustache.

Lt Hans Adam of Bavarian Jasta 35, seen in the cockpit of his Albatros D III, 2101/16. Adam, with 21 confirmed 'kills', met his own end in the skies over Mortvilde on 15 November 1917, while flying with Bavarian Jasta 6.

The Albatros D III, although having an entirely new wing, elsewhere embodied as much of the D II componentry as it could, revealing that Albatros's Chief Engineer, Robert Thelen's design philosophy lent towards doing things in an evolutionary, rather than a revolutionary manner. The D III can with hindsight be seen as the best of the Albatros single seaters, its successor, the D V incorporating too few real improvements over the D III at a time when the opposition was advancing apace. The D III, great aeroplane as it turned out, had one major inherent design flaw that led to wing flutter at high speed and consequent occasional structural failure and mid-air break up. The root of the problem lay in Thelen's decision to follow the Nieuport practice by adopting a sesquiplane, literally a one and a half wing layout. In doing this.Thelen fell into the same trap that the Nieuports had already experienced and had never really solved. In essence, the trouble lay with the combination of a torsionally weak, small lower wing being made to twist and oscillate through then little understood aerodynamic loads transmitted to it via the 'V' type interplane struts. This led to D III pilots being prohibited from diving the machine above a certain speed; quite a constraint for pilots who at some time or another were going to rely on the aircraft's ability to break away quickly from combat with a superior opponent. Shown here is an initial production model Albatros D III, delivered to Jasta 29 in early 1917. Although very kind in terms of pilot handling, these early D IIIs, besides being dive limited had another hazard in the form of the radiator that can just be seen positioned immediately ahead of the cockpit and filling the space between fuselage and upper wing centre section. If hit during combat, the radiator fluid could readily scald the pilot and frequently did. The solution was to move it to the underside of the upper starboard wing. In all, more than 1,300 D IIIs were built, the first being delivered to the front in January 1917. While the sea level top speed of the D III was the same as that for the D I and D II, its speed at height was improved through the use of a high compression Daimler D III. Armament comprised the by-now standard twin 7.92mm Spandaus. The D III's heyday in the spring of 1917 began to fade by the summer when encountering the new Allied fighters in the shape of Sopwith Camels, Royal Aircraft Factory SE 5s and Spads.

This early production Albatros D III of Lt Dornheim, Jasta 29, having its radiator put under scrutiny. This image is also useful in showing the standard starboard side-only position of the Mercedes D III's exhaust manifold.

Werner Voss, born 13 April 1897, was not yet eighteen when he enlisted in a Hussars Regiment just prior to the outbreak of World War I. In August 1915, he transferred into flying, initially as an observer, where he survived the Battle of the Somme, launched on 1 July 1916 and a period when the Allies held superiority in the air. Voss left the front in August 1916 to be trained as a pilot, joining Jasta 2 on 21 November 1916, flying Albatros D IIIs. Six days later Voss scored his first 'kill'. By the end of February 1917, Voss's score was 22 and on 8 April 1917 he was awarded the Pour Le Merite. Voss went on to join Jasta 5, where he added a further 12 "kills' flying against the French, before taking command of Jasta 10 on 31 July 1917. Here, facing the British, Voss added another 14 victories, taking his total tally to 48 before he elected to fly just one more sortie prior to going on leave with his two brothers. Voss had the misfortune to encounter the hand-picked SE 5a pilots of No 56 Squadron, RAF and succumbed to their guns. Voss was the 4th ranking German air ace of the war. He is seen standing beside his Albatros D III of Jasta 2, decorated with his personal emblem.

Germany's leading World War I fighter ace, Baron Manfred von Richthofen, went to war in August 1914 as a young lieutenant in a lancer regiment, aged twenty two. Only at the close of 1914 did he succeed in transferring to the Army Air Service, where, as with many other fighter aces to be, he cut his aviation teeth first training and then operating as an observer. Indeed, it is generally held that although officially unconfirmed, his first 'kill' was made against a Farman from the rear of a two seater. Even after gaining his wings on Christmas Day 1915, the young flier was to remain piloting two seaters for much of 1916. It was during this period that he was to meet the father of German fighter tactics, Oswald Boelcke. Clearly something about Richthofen impressed Boelcke, who subsequently invited him to join his newly formed fighter squadron, or Jagdstaffel 2. Here, Richthofen was one of four to fly the unit's first mission on 17 September 1916, setting him on a course that was to see him credited with 80 victories, before he and his scarlet Fokker Dr I were to meet their end on 21 April 1918. The Baron scored official victory number 16 on January 4 1917 and received the Pour Le Merite twelve days later as the new leader of Jasta 2 (at that time the medal was awarded for 16 kills). The picture captures the young Baron about to climb into his personal transport, which, ironically, was the sole prototype Albatros C IX, presented to him after its failure to gain full operational acceptance.

Early in 1917, while the Albatros D IV saga was still unravelling, as dealt with above, the firm produced its first D.V. As it transpired, while adequate and built in massive numbers, this design served to prove the law of diminishing returns. In essence, the Albatros DV employed exactly the same wings as the D III, along with the tailplane and elevator, all of which were interchangeable between the two fighters. Initially, even the fin and rudder were identical, but later fin area was increased, leading the to the D V's characteristically rounded rudder trailing edge. Married to these components, Albatros took the new, semi-monocoque fuselage developed for their D IV and, for good measure, further lowered the upper wing in relation to the fuselage in order to yet further improve the pilot's forward visibility. The engine in early D Vs remained the 160hp Mercedes D III, replaced in the structurally strengthened D Va with the 185hp D IIIa. Both the German Air Ministry and Albatros appeared happy with the resulting machine, despite the fact that its top level speed of 116mph at 3,280 feet, or for that matter the fighter's agility, were little improved compared with the D III. Further, the high speed lower wing flutter of the D III was still present, restricting high speed flight and, therefore, limiting the combat pilot's primary option of diving away from trouble. The armament comprised the standard twin 7.92mm Spandaus. Initial deliveries of D Vs were made to the front in July 1917 and rapidly built up from that point on, with Albatros output being joined by that of their Austrian subsidiary OAW During the autumn of 1917, DV production was switched to the strengthened and more powerful D Va. No precise production totals have survived for the DV and Va, but the knowledge that at their respective peaks of November 1917 and May 1918, no less than 526 D Vs along with 986 examples of the DVa were in service, would, allowing for attrition and spares, indicate a minimum overall build exceeding 2,200 machines. There is reason to believe that all 80 Jastas operating in the spring of 1918 had, at least, some D V or Va on their strength. The early DV depicted carries the Bavarian Lion motif of Hpt Eduard flitter von Schleich, leader of Jasta 21, who survived the war with a Pour Le Merite ('Blue Max') and a confirmed 35 'kills'. The pilot's headrest, seen in this image, was not particularly favoured by operational pilots and was soon removed from most machines.

An interesting frontal aspect on the Albatros D Va, believed to have belonged to a Bavarian Jasta and which from the presence of wheel chocks and the mechanic holding the tail down is seen undergoing engine running tests.

Oberleutnant Freidrich Ritter von Roth, seen here standing beside his Albatros D Va, was born of aristocratic parents on 29 September 1893. Having volunteered at the outbreak of war, 'Fritz', as he was popularly known, joined a Bavarian artillery regiment and was almost immediately promoted to sergeant. Wounded in action soon after, Roth was commissioned on 29 May 1915 while still recuperating. Transferring to the flying service and pilot training towards the close of 1915, Roth was severely injured in a flying accident that delayed his gaining his wings until early 1917. Roth's first operational experience was gained with Fl Abt 296, a two seater unit, then based at Annelles, as part of the 1st Army, which he joined on 1 April 1917. Roth moved to fighters in the autumn of 1917 and after a busy closing quarter of 1917 and early 1918, during which he had served with Jastas 34 and 23, he was given command of Jasta 16 on 24 April 1918. Meanwhile, Roth's first confirmed 'kill' was made on 25 January 1918 and involved the dangerous business of downing a heavily defended balloon. As balloons were considered a vital tactical reconnaissance tool by both sides and were always heavily defended, it is a measure of the man that Roth appears to have subsequently specialized in attacking balloons, being credited with no less than 20 of them out of his total 28 confirmed vicories. Dispirited by the impact of the Armistice and the dissolution of his beloved Air Service, Freidrich Ritter von Roth took his own life on New Year' Eve, 31 December 1918.

Destined to head the Luftwaffe in World War II, Hermann Goring is pictured here, second from left, with his newly delivered Albatros D V. At this time Goring was serving with Jasta 27 and had just scored his fifth 'kill'. He was to finish the war as a Hauptmannn, commanding JG I, the post he took over following the death of Baron Manfred von Richthofen. Goring was a holder of the Pour Le Merite and had 22 confirmed victories.

Lt Schlomer poses nonchalantly beside his Albatros DVa in the late summer of 1917. Schlomer had became leader of Jasta 5, following the death of Oblt Berr at Noyelles on 8 April 1917. Schlomer, himself was to be killed just over a year and a month later, on 31 May 1918.

Bruno Loerzer, an Oberleutnant at the time this picture was taken, when commanding Jasta 26 of JG 2. Born on 22 January 1891, Loerzer is seen standing besides his Albatros D V. Awarded the Order Pour Le Merite, Germany's highest military honour on 12 February 1918, Loerzer went on to become a Hauptmann, the equivalent to a US Captain or RAF Squadron Leader, when promoted to lead JG 3. Loerzer ended his war with an accredited 44 'kills', placing him 8th in the ranking of German leading air aces.

The other side of the coin. To counterbalance the romantic view of air combat is this image of the debris of what had been Oblt Hans Berr's Albatros D V, in which he was killed south of Noyelles on 6 April 1917. Berr had been the first commanding Officer of Jasta 5 and died with a confirmed score of 10 victories.

Probably one of the best of the C types, DFW's CV embodied all of the neatness and efficiency of the C IV that had made its service debut early in 1916, but benefitted from the greater power of a 200hp Benz Bz IV. This gave the machine a top level speed of 97mph at 3,280 feet, while the C V's operational ceiling was 16,400 feet. Built not just by DFW, but by four other sub-contractors, the C V was probably the best all-rounder of the German two seaters with just under 1,000 being in operation on every front at the end of September 1917. Armament comprised the standard fixed, forward-firing and flexibly-mounted 7.92mm guns, plus light bombs. Shown here is a DFW C V of Fl Abt (A) 224 at Chateau Bellingcamps photogaphed on 22 May 1917.

Lieutenants Leppin and Basedow, of Fl Abt 234, pose beside Aviatik-built DFW C V just prior to the launch of the great German offensive of late march 1918. Aimed at thrusting through to the French coast to sever contact between the British and French armies, the role of the Field Flight Sections in providing tactical information was crucial in the run-up to the 21 March zero hour. To this end, 49 Field Flight Sections, or approximately one third of Germany's total two seater assets were directly deployed in support of the offensive. The DFW C V was the mainstay of the field Flight Sections until into the summer of 1918 and the operational arrival of the DFW C VI.

An excellent air-to-air aspect on a two seat DFW C V of the German Imperial Air Service's 1st Field Service Section. Taken near to the front lines in the autunm of 1917, this view shows the irregular application of dull green and brown with which the majority of German combat types were camouflaged prior to the January 1918 adoption of the multi-colour hexagonal scheme. Both the 1st and 2nd naval Field Service Sections appear to have used a mixture of DFW C Vs and LVG C Vs with which to carry out their reconnaissance work.

Very few records survive concerning the other Nieuport copy, the Euler D.I, other than the knowledge that it was powered by a 100hp rotary and, as this picture shows, that at least one made it to the Western Front. This image was taken in July 1916 or immediately thereafter with KEK Nord, prior to it becoming Jasta I on 23 August 1916. The Euler's pilot, seen here, Lt Leffers, credited with one 'kill', was to meet his own end near Cherisy on 27 December 1916.

Three other triplane fighter essays of 1917 were the rotary-powered Euler Dr 3, (photo) the 185hp Austro-Daimler powered Hansa-Brandenburg L 16 and the Korting engined DFW Dr I.

Anthony Fokker, pilot and aircraft manufacturer, had the entrepreneur's innate gift for getting it right in his business decisions. An early example of this was his setting up of the Fokker Flying School at Doberitz, close to Berlin in late 1912. When the German Army announced their plan to sub-contract flying training to civilian organisations in 1912, Fokker grasped the opportunity of establishing close personal contact with the future leaders of German military aviation. Although Fokker left the day-to-day training chores to his flying instructors, he was the school's Chief Flying Instructor and Examiner. Fokker is seen here sitting on the axle of one of his Fokker Spin two seaters, amid one of his early military intakes.

A factory documentation view near to pilot's-eye view of an experimental triple 7.92mm Spandau gun installation synchronized to fire through the propeller arc of this Fokker E IV. This fit was the culmination of Fokker's efforts to arm his early monoplanes, or eindeckers and although Max Immelmann tested this three-weapon fit, he preferred the Eindecker's standard single gun installation. The bar visible inside the cockpit was the firing control for the three guns.